Submitted:

30 September 2025

Posted:

30 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Study Population and Data Sources

Definitions

Statistical Analysis

3. Results

Patient Characteristics

AEDs Prescription Patterns

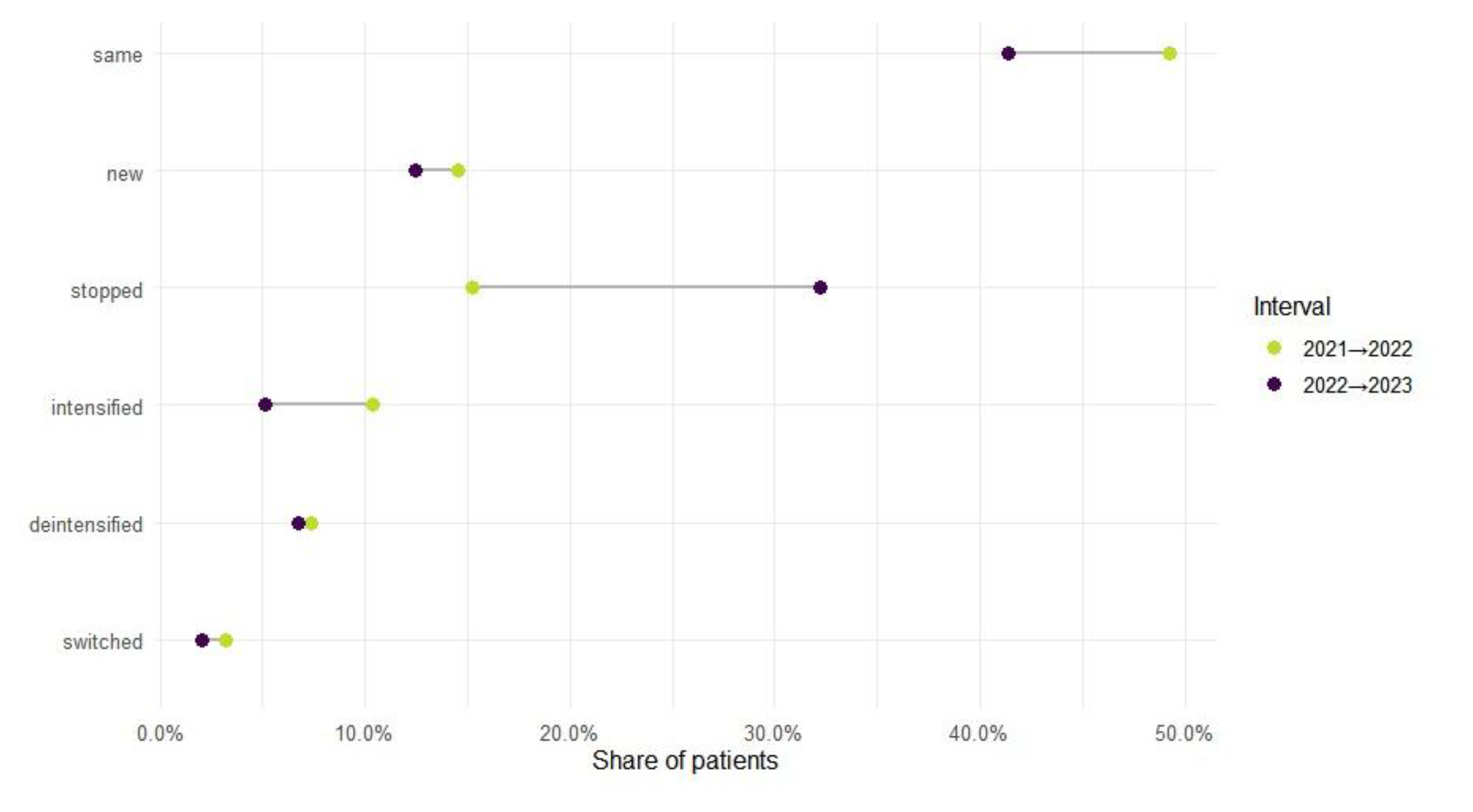

Mono-to-Polytherapy Transitions Among AED-Treated Patients

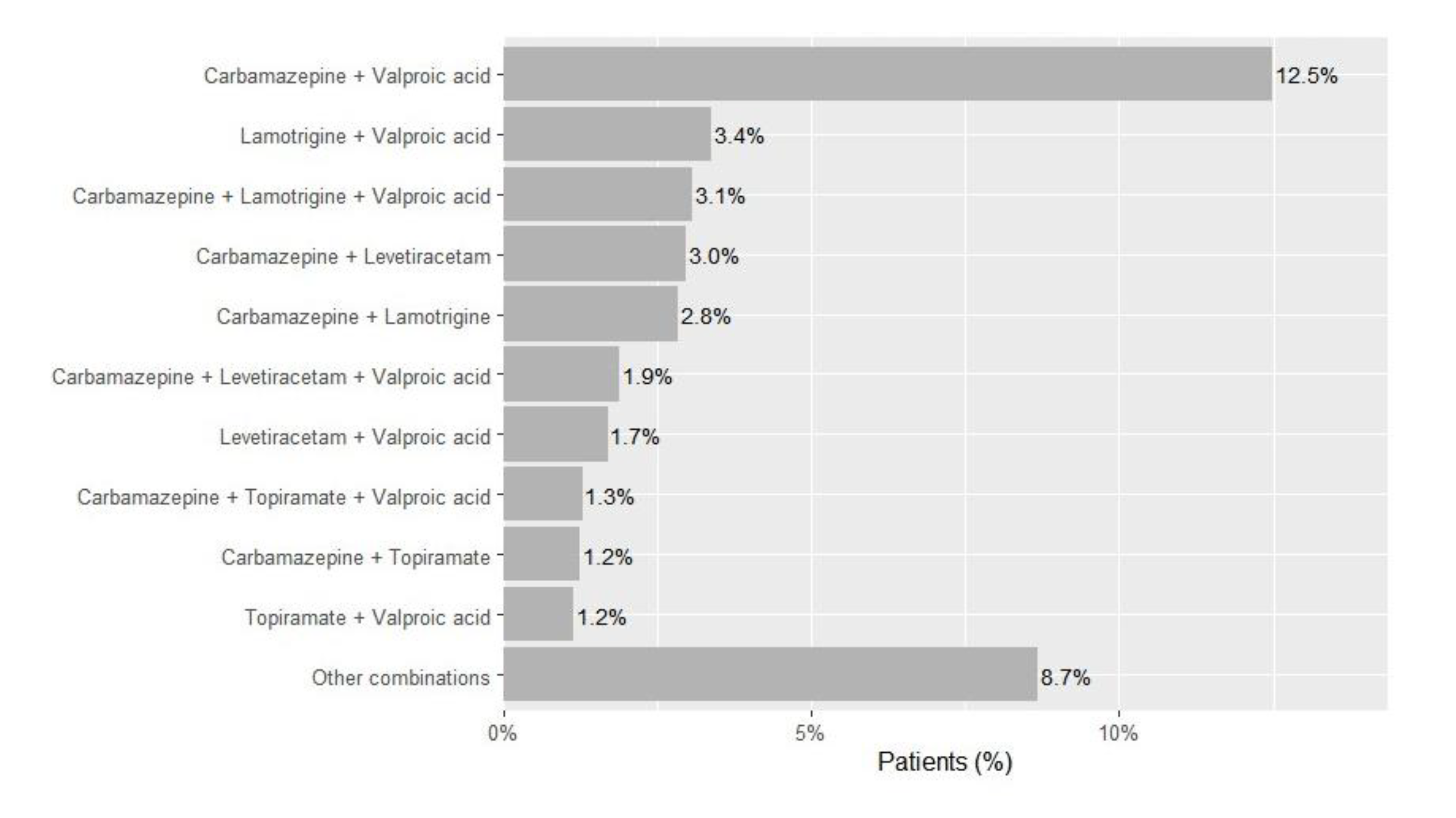

Chronic Polytherapy Patterns

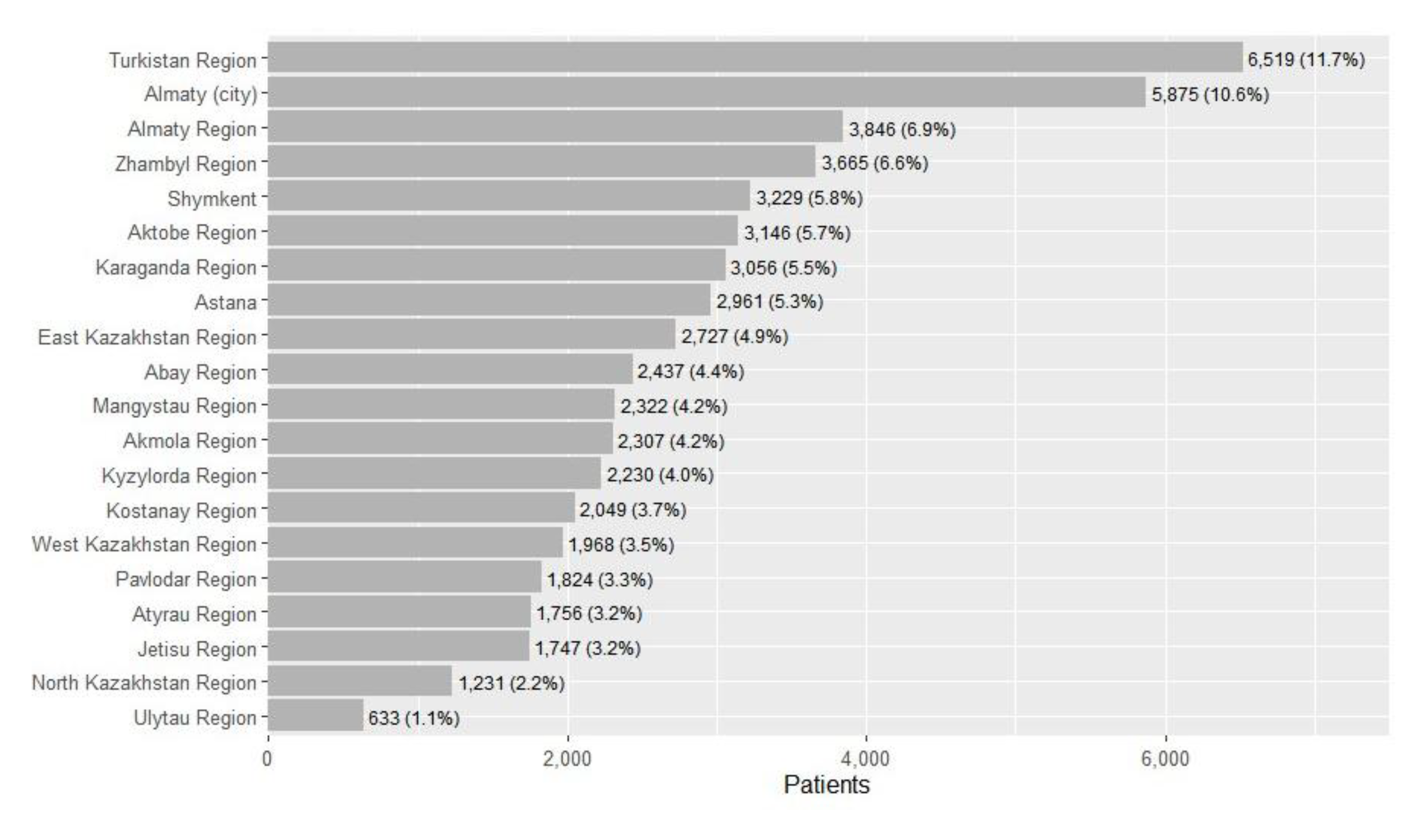

Regional Patterns in Treatment and Comorbidity

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AED(s) | Antiepileptic drug(s) |

| ICD-10 | International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision |

| WHO ATC | World Health Organization Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical classification |

| LMICs | Low- and middle-income countries |

| LDL | Low-density lipoprotein |

References

- Feigin, V.L.; Vos, T.; Nair, B.S.; Hay, S.I.; Abate, Y.H.; Magied, A.H.A.A.A.; ElHafeez, S.A.; Abdelkader, A.; Abdollahifar, M.-A.; Abdullahi, A.; et al. Global, Regional, and National Burden of Epilepsy, 1990–2021: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. The Lancet Public Health 2025, 10, e203–e227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalinina, D.; Akhmedullin, R.; Muxunov, A.; Sarsenov, R.; Sarria-Santamera, A. Epidemiological Trends of Idiopathic Epilepsy in Central Asia: Insights from the Global Burden of Disease Study (1990–2021). Seizure - European Journal of Epilepsy 2025, 131, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhmedullin, R.; Kozhobekova, B.; Gusmanov, A.; Aimyshev, T.; Utebekov, Z.; Kyrgyzbay, G.; Shpekov, A.; Gaipov, A. Epilepsy Trends in Kazakhstan: A Retrospective Longitudinal Study Using Data from Unified National Electronic Health System 2014–2020. Seizure: European Journal of Epilepsy 2024, 122, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, A.-C.; Dua, T.; Ma, J.; Saxena, S.; Birbeck, G. Global Disparities in the Epilepsy Treatment Gap: A Systematic Review. Bull. World Health Organ. 2010, 88, 260–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mbuba, C.K.; Newton, C.R. Packages of Care for Epilepsy in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. PLoS Med 2009, 6, e1000162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO Epilepsy: A Public Health Imperative Available online:. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/epilepsy-a-public-health-imperative (accessed on 16 August 2025).

- Nevitt, S.J.; Sudell, M.; Cividini, S.; Marson, A.G.; Smith, C.T. Antiepileptic Drug Monotherapy for Epilepsy: A Network Meta-analysis of Individual Participant Data - Nevitt, SJ - 2022 | Cochrane Library. 2022.

- Cockerell, O.C.; Sander, J.W. a. S.; Hart, Y.M.; Shorvon, S.D.; Johnson, A.L. Remission of Epilepsy: Results from the National General Practice Study of Epilepsy. The Lancet 1995, 346, 140–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauser, W.A.; Annegers, J.F.; Kurland, L.T. Incidence of Epilepsy and Unprovoked Seizures in Rochester, Minnesota: 1935–1984. Epilepsia 1993, 34, 453–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sander, J.W. The Use of Antiepileptic Drugs--Principles and Practice. Epilepsia 2004, 45 Suppl 6, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, D.Y. Epilepsy and Seizures Treatment & Management: Approach Considerations, Anticonvulsant Therapy, Anticonvulsants for Specific Seizure Types. 2022.

- Krumholz, A.; Wiebe, S.; Gronseth, G.S.; Gloss, D.S.; Sanchez, A.M.; Kabir, A.A.; Liferidge, A.T.; Martello, J.P.; Kanner, A.M.; Shinnar, S.; et al. Evidence-Based Guideline: Management of an Unprovoked First Seizure in Adults. Neurology 2015, 84, 1705–1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St. Louis, E. Minimizing AED Adverse Effects: Improving Quality of Life in the Interictal State in Epilepsy Care. Curr Neuropharmacol 2009, 7, 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St. Louis, E.K. Truly “Rational” Polytherapy: Maximizing Efficacy and Minimizing Drug Interactions, Drug Load, and Adverse Effects. Current Neuropharmacology 2009, 7, 96–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Wang, X.; Deng, M.; Luo, Q.; Yang, C.; Gu, Z.; Lin, S.; Luo, Y.; Chen, L.; Li, Y.; et al. Antiepileptic Drug Combinations for Epilepsy: Mechanisms, Clinical Strategies, and Future Prospects. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2025, 26, 4035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacob, L.; Kerimbaeva, Z.; Kalyapin, A.; Kostev, K. Prescription Patterns of Antiepileptic Drugs in Kazakhstan in 2018: A Retrospective Study of 57,959 Patients. Epilepsy & Behavior 2019, 99, 106445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, K.W.; Lee, H.; Shin, J.-Y.; Moon, H.-J.; Lee, S.-Y. Trends in Prescribing of Antiseizure Medications in South Korea: Real-World Evidence for Treated Patients With Epilepsy. Journal of Clinical Neurology 2022, 18, 179–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, C.-Y.; Chiang, K.-L.; Hsieh, L.-P.; Chien, L.-N. Prescription Patterns and Dosages of Antiepileptic Drugs in Prevalent Patients with Epilepsy in Taiwan: A Nationwide Retrospective Cross-Sectional Study. Epilepsy & Behavior 2022, 126, 108450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, G.; Goraya, J. The Medical Management of Epilepsy in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. In Epilepsy: A Global Approach; Krishnamoorthy, E.S., Shorvon, S.D., Schachter, S.C., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2017; ISBN 978-1-107-03537-9. [Google Scholar]

- Chappell, B.; Crawford, P. An Audit of Lamotrigine, Levetiracetam and Topiramate Usage for Epilepsy in a District General Hospital. Seizure 2005, 14, 422–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, J.A.; Gazzola, D.M. New Generation Antiepileptic Drugs: What Do They Offer in Terms of Improved Tolerability and Safety? Ther Adv Drug Saf 2011, 2, 141–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marson, A.; Burnside, G.; Appleton, R.; Smith, D.; Leach, J.P.; Sills, G.; Tudur-Smith, C.; Plumpton, C.; Hughes, D.A.; Williamson, P.; et al. The SANAD II Study of the Effectiveness and Cost-Effectiveness of Levetiracetam, Zonisamide, or Lamotrigine for Newly Diagnosed Focal Epilepsy: An Open-Label, Non-Inferiority, Multicentre, Phase 4, Randomised Controlled Trial. Lancet 2021, 397, 1363–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoeltzenbein, M.; Slimi, S.; Fietz, A.-K.; Dathe, K.; Schaefer, C. Trends in Use of Antiseizure Medication and Treatment Pattern during the First Trimester in the German Embryotox Cohort. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 30585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Faught, E.; Thurman, D.J.; Fishman, J.; Kalilani, L. Antiepileptic Drug Treatment Patterns in Women of Childbearing Age With Epilepsy. JAMA Neurology 2019, 76, 783–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomson, T.; Battino, D. Teratogenic Effects of Antiepileptic Drugs. Lancet Neurol 2012, 11, 803–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heger, K.; Skipsfjord, J.; Kiselev, Y.; Burns, M.L.; Aaberg, K.M.; Johannessen, S.I.; Skurtveit, S.; Johannessen Landmark, C. Changes in the Use of Antiseizure Medications in Children and Adolescents in Norway, 2009–2018. Epilepsy Research 2022, 181, 106872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanner, A.M.; Shankar, R.; Margraf, N.G.; Schmitz, B.; Ben-Menachem, E.; Sander, J.W. Mood Disorders in Adults with Epilepsy: A Review of Unrecognized Facts and Common Misconceptions. Annals of General Psychiatry 2024, 23, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, O.-Y.; Park, S.-P. Depression and Anxiety in People with Epilepsy. Journal of Clinical Neurology 2014, 10, 175–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, D.; Kerr, M.P.; McManus, S.; Jordanova, V.; Lewis, G.; Brugha, T.S. Epilepsy and Psychiatric Comorbidity: A Nationally Representative Population-Based Study. Epilepsia 2012, 53, 1095–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruun, E.; Virta, L.J.; Kälviäinen, R.; Keränen, T. Co-Morbidity and Clinically Significant Interactions between Antiepileptic Drugs and Other Drugs in Elderly Patients with Newly Diagnosed Epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav 2017, 73, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaertner, M.L.; Mintzer, S.; DeGiorgio, C.M. Increased Cardiovascular Risk in Epilepsy. Front Neurol 2024, 15, 1339276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loureiro Fialho, G.; Miotto, R.; Tatsch Cavagnollo, M.; Murilo Melo, H.; Wolf, P.; Walz, R.; Lin, K. The Epileptic Heart: Cardiac Comorbidities and Complications of Epilepsy. Atrial and Ventricular Structure and Function by Echocardiography in Individuals with Epilepsy – From Clinical Implications to Individualized Assessment. Epilepsy & Behavior Reports 2024, 26, 100668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Huang, P.; Yu, Q.; Lu, J.; Liu, P.; Yang, Y.; Feng, Z.; Cai, J.; Yang, G.; Yuan, H.; et al. Epilepsy and Long-Term Risk of Arrhythmias. Eur Heart J 2023, 44, 3374–3382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosak, M.; Słowik, A.; Iwańska, A.; Lipińska, M.; Turaj, W. Co-Medication and Potential Drug Interactions among Patients with Epilepsy. Seizure 2019, 66, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, J.-G.; Cho, Y.W.; Kim, K.T.; Kim, D.W.; Yang, K.I.; Lee, S.-T.; Byun, J.-I.; No, Y.J.; Kang, K.W.; Kim, D.; et al. Pharmacological Treatment of Epilepsy in Elderly Patients. Journal of Clinical Neurology 2020, 16, 556–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadesse, T.A.; Belayneh, A.; Aynalem, M.W.; Yifru, Y.M.; Amare, F.; Beyene, D.A. Potentially Inappropriate Prescribing in Elderly Patients with Epilepsy at Two Referral Hospitals in Ethiopia. Front. Med. 2024, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NICE Overview | Epilepsies in Children, Young People and Adults | Guidance | NICE Available online:. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng217?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 18 August 2025).

- Mehndiratta, M.M.; Kukkuta Sarma, G.R.; Tripathi, M.; Ravat, S.; Gopinath, S.; Babu, S.; Mishra, U.K. A Multicenter, Cross-Sectional, Observational Study on Epilepsy and Its Management Practices in India. Neurology India 2022, 70, 2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johannessen Landmark, C.; Larsson, P.G.; Rytter, E.; Johannessen, S.I. Antiepileptic Drugs in Epilepsy and Other Disorders--a Population-Based Study of Prescriptions. Epilepsy Res 2009, 87, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrew, T.; Milinis, K.; Baker, G.; Wieshmann, U. Self Reported Adverse Effects of Mono and Polytherapy for Epilepsy. Seizure - European Journal of Epilepsy 2012, 21, 610–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abokrysha, N.T.; Taha, N.; Shamloul, R.; Elsayed, S.; Osama, W.; Hatem, G. Clinical, Radiological and Electrophysiological Predictors for Drug-Resistant Epilepsy. Egypt J Neurol Psychiatr Neurosurg 2023, 59, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perucca, E.; Perucca, P.; White, H.S.; Wirrell, E.C. Drug Resistance in Epilepsy. The Lancet Neurology 2023, 22, 723–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue-Ping, W.; Hai-Jiao, W.; Li-Na, Z.; Xu, D.; Ling, L. Risk Factors for Drug-Resistant Epilepsy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Medicine 2019, 98, e16402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clancy, M.J.; Clarke, M.C.; Connor, D.J.; Cannon, M.; Cotter, D.R. The Prevalence of Psychosis in Epilepsy; a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Psychiatry 2014, 14, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiest, K.M.; Dykeman, J.; Patten, S.B.; Wiebe, S.; Kaplan, G.G.; Maxwell, C.J.; Bulloch, A.G.M.; Jette, N. Depression in Epilepsy. Neurology 2013, 80, 590–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, A.J.; Sharpe, L.; Hunt, C.; Gandy, M. Anxiety and Depressive Disorders in People with Epilepsy: A Meta-Analysis. Epilepsia 2017, 58, 973–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mann, S.K.; Marwaha, R. Chlorpromazine. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island (FL), 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Sateia, M.J.; Buysse, D.J.; Krystal, A.D.; Neubauer, D.N.; Heald, J.L. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Pharmacologic Treatment of Chronic Insomnia in Adults: An American Academy of Sleep Medicine Clinical Practice Guideline. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine 2017, 13, 307–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzo, N.; Blyzniuk, B.; Chumakov, E.; Seifritz, E.; de Leon, J.; Schoretsanitis, G. Clozapine Research Standards in Former USSR States: A Systematic Review of Quality Issues with Recommendations for Future Harmonization with Modern Research Standards. Schizophrenia Research 2024, 268, 48–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zajicek, B. The Psychopharmacological Revolution in the USSR: Schizophrenia Treatment and the Thaw in Soviet Psychiatry, 1954–1964. Med Hist 2019, 63, 249–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeGeorge, K.C.; Grover, M.; Streeter, G.S. Generalized Anxiety Disorder and Panic Disorder in Adults. afp 2022, 106, 157–164. [Google Scholar]

- Devinsky, O.; Honigfeld, G.; Patin, J. Clozapine-related Seizures. Neurology 1991, 41, 369–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatano, M.; Yamada, K.; Matsuzaki, H.; Yokoi, R.; Saito, T.; Yamada, S. Analysis of Clozapine-Induced Seizures Using the Japanese Adverse Drug Event Report Database. PLOS ONE 2023, 18, e0287122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varma, S.; Bishara, D.; Besag, F.M.C.; Taylor, D. Clozapine-Related EEG Changes and Seizures: Dose and Plasma-Level Relationships. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol 2011, 1, 47–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, J.; Delva, N. Clozapine-Induced Seizures: Recognition and Treatment. Can J Psychiatry 2007, 52, 457–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jilani, T.N.; Sabir, S.; Patel, P.; Sharma, S. Trihexyphenidyl. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island (FL), 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Vanegas-Arroyave, N.; Caroff, S.N.; Citrome, L.; Crasta, J.; McIntyre, R.S.; Meyer, J.M.; Patel, A.; Smith, J.M.; Farahmand, K.; Manahan, R.; et al. An Evidence-Based Update on Anticholinergic Use for Drug-Induced Movement Disorders. CNS Drugs 2024, 38, 239–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galiyeva, D.; Gusmanov, A.; Sakko, Y.; Issanov, A.; Atageldiyeva, K.; Kadyrzhanuly, K.; Nurpeissova, A.; Rakhimzhanova, M.; Durmanova, A.; Sarria-Santamera, A.; et al. Epidemiology of Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus in Kazakhstan: Data from Unified National Electronic Health System 2014–2019. BMC Endocrine Disorders 2022, 22, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vivanco-Hidalgo, R.M.; Gomez, A.; Moreira, A.; Díez, L.; Elosua, R.; Roquer, J. Prevalence of Cardiovascular Risk Factors in People with Epilepsy. Brain Behav 2016, 7, e00618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yerdessov, S.; Kadyrzhanuly, K.; Sakko, Y.; Gusmanov, A.; Zhakhina, G.; Galiyeva, D.; Bekbossynova, M.; Salustri, A.; Gaipov, A. Epidemiology of Arterial Hypertension in Kazakhstan: Data from Unified Nationwide Electronic Healthcare System 2014–2019. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis 2022, 9, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, N.P.; Hoang, K.; Delate, T.; Horn, J.R.; Witt, D.M. Warfarin Interaction With Hepatic Cytochrome P-450 Enzyme-Inducing Anticonvulsants. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost 2018, 24, 172–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galgani, A.; Palleria, C.; Iannone, L.F.; De Sarro, G.; Giorgi, F.S.; Maschio, M.; Russo, E. Pharmacokinetic Interactions of Clinical Interest Between Direct Oral Anticoagulants and Antiepileptic Drugs. Front. Neurol. 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mar, P.L.; Gopinathannair, R.; Gengler, B.E.; Chung, M.K.; Perez, A.; Dukes, J.; Ezekowitz, M.D.; Lakkireddy, D.; Lip, G.Y.H.; Miletello, M.; et al. Drug Interactions Affecting Oral Anticoagulant Use. Circulation: Arrhythmia and Electrophysiology 2022, 15, e007956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mintzer, S.; Maio, V.; Foley, K. Use of Antiepileptic Drugs and Lipid-Lowering Agents in The United States. Epilepsy Behav 2014, 34, 105–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mintzer, S.; Yi, M.; Hegarty, S.; Maio, V.; Keith, S. Hyperlipidemia in Patients Newly Treated with Anticonvulsants: A Population Study. Epilepsia 2020, 61, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarangi, S.C.; Pattnaik, S.S.; Dash, Y.; Tripathi, M.; Velpandian, T. Is There Any Concern of Insulin Resistance and Metabolic Dysfunctions with Antiseizure Medications? A Prospective Comparative Study of Valproate vs. Levetiracetam. Seizure: European Journal of Epilepsy 2024, 121, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidhu, H.S.; Srinivas, R.; Sadhotra, A. Evaluate the Effects of Long-Term Valproic Acid Treatment on Metabolic Profiles in Newly Diagnosed or Untreated Female Epileptic Patients: A Prospective Study. Seizure 2017, 48, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verrotti, A.; D’Egidio, C.; Mohn, A.; Coppola, G.; Chiarelli, F. Weight Gain Following Treatment with Valproic Acid: Pathogenetic Mechanisms and Clinical Implications. Obes Rev 2011, 12, e32–e43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto, Y.; Terada, K.; Takahashi, Y.; Imai, K.; Kagawa, Y.; Inoue, Y. Influence of Antiepileptic Drugs on Serum Lipid Levels in Adult Epilepsy Patients. Epilepsy Res 2016, 127, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galovic, M.; Ferreira-Atuesta, C.; Abraira, L.; Döhler, N.; Sinka, L.; Brigo, F.; Bentes, C.; Zelano, J.; Koepp, M.J. Seizures and Epilepsy After Stroke: Epidemiology, Biomarkers and Management. Drugs Aging 2021, 38, 285–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Yu, W.; Lü, Y. The Causes of New-Onset Epilepsy and Seizures in the Elderly. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2016, 12, 1425–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pellinen, J. Treatment Gaps in Epilepsy. Front. Epidemiol. 2022, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.; Mahajan, N.; Singh, G.; Sander, J.W. Temporal Trends in the Epilepsy Treatment Gap in Low- and Low-Middle-Income Countries: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of the Neurological Sciences 2022, 434, 120174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guekht, A.; Zharkinbekova, N.; Shpak, A.; Hauser, W.A. Epilepsy and Treatment Gap in Urban and Rural Areas of the Southern Kazakhstan in Adults. Epilepsy Behav 2017, 67, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, L.; Wettermark, B.; Steinke, D.; Pottegård, A. Core Concepts in Pharmacoepidemiology: Measures of Drug Utilization Based on Individual-level Drug Dispensing Data. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2022, 31, 1015–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochbaum, M.; Kienitz, R.; Rosenow, F.; Schulz, J.; Habermehl, L.; Langenbruch, L.; Kovac, S.; Knake, S.; von Podewils, F.; von Brauchitsch, S.; et al. Trends in Antiseizure Medication Prescription Patterns among All Adults, Women, and Older Adults with Epilepsy: A German Longitudinal Analysis from 2008 to 2020. Epilepsy Behav 2022, 130, 108666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, G.; Logan, J.; Kiri, V.; Borghs, S. Trends in Antiepileptic Drug Treatment and Effectiveness in Clinical Practice in England from 2003 to 2016: A Retrospective Cohort Study Using Electronic Medical Records. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e032551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, A.; Bansal, A.; Dua, T.; Hill, S.R.; Moshe, S.L.; Mantel-Teeuwisse, A.K.; Saxena, S. Mapping the Availability, Price, and Affordability of Antiepileptic Drugs in 46 Countries. Epilepsia 2012, 53, 962–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meador, K.J.; Baker, G.A.; Browning, N.; Cohen, M.J.; Bromley, R.L.; Clayton-Smith, J.; Kalayjian, L.A.; Kanner, A.; Liporace, J.D.; Pennell, P.B.; et al. Fetal Antiepileptic Drug Exposure and Cognitive Outcomes at Age 6 Years (NEAD Study): A Prospective Observational Study. Lancet Neurol 2013, 12, 244–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomson, T.; Battino, D.; Bonizzoni, E.; Craig, J.; Lindhout, D.; Perucca, E.; Sabers, A.; Thomas, S.V.; Vajda, F. ; For the EURAP Study Group Dose-Dependent Teratogenicity of Valproate in Mono- and Polytherapy. Neurology 2015, 85, 866–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwan, P.; Arzimanoglou, A.; Berg, A.T.; Brodie, M.J.; Allen Hauser, W.; Mathern, G.; Moshé, S.L.; Perucca, E.; Wiebe, S.; French, J. Definition of Drug Resistant Epilepsy: Consensus Proposal by the Ad Hoc Task Force of the ILAE Commission on Therapeutic Strategies. Epilepsia 2010, 51, 1069–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Value | |

| Age, median (IQR) | 42 (31-57) |

| ICD, number of patients (%) | |

| G40 | 11608 (21.4%) |

| G40.1 | 5509 (10.2%) |

| G40.2 | 11170 (20.6%) |

| G40.3 | 10632 (19.6%) |

| G40.4 | 3392 (6.3%) |

| G40.5 | 421 (0.8%) |

| G40.6 | 62 (0.1%) |

| G40.7 | 40 (0.07%) |

| G40.8 | 13544 (24.9%) |

| G40.9 | 4408 (8.1%) |

| Level of therapy, number of patients (%) | |

| Monotherapy | 33471 (61.7%) |

| Polytherapy | 10052 (18.5%) |

| Switched from monotherapy to polytherapy | 6664 (12.3%) |

| Switched from polytherapy to monotherapy | 6135 (11.3%) |

| Prescribed AEDs, number of patients (%) | |

| Carbamazepine | 34894 (64.3%) |

| Valproic acid | 24766 (45.6%) |

| Lamotrigine | 11070 (20.4%) |

| Levetiracetam | 8263 (15.2%) |

| Topiramate | 4794 (8.8%) |

| Oxcarbazepine | 1327 (2.4%) |

| OR (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|

|

Age Comorbid drugs ICD G40.2 |

0.98 (0.98 - 0.99) | <0.01* |

| 1.00 (0.97 – 1.01) | 0.82 | |

| 0.85 (0.78 – 0.92) | <0.01* | |

| G40.3 G40.0 |

1.15 (1.06 – 1.24) | <0.01* |

| 0.99 (0.91 – 1.08) | 0.84 | |

| G40.1 G40.9 G40.4 G40 |

0.89 (0.8 – 0.99) | 0.03* |

| 0.97 (0.87 – 1.08) | 0.6 | |

| 1.00 (0.88 – 1.12) | 0.94 | |

| 1.01 (0.87 – 1.16) | 0.91 | |

| G40.5 G40.6 |

0.71 (0.48 – 1.00) | 0.06 |

| 0.82 (0.31 – 1.75) | 0.64 | |

| G40.7 | 0.85 (0.25 – 2.13) | 0.75 |

| Chronic Polytherapy Level | AEDs | Somatic Drugs | Psychiatric Drugs | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 drugs | 4,192 (26.6%) | 2,087 (13.2%) | 1,846 (11.7%) | 3,529 (22.4%) |

| 3 drugs | 1,612 (10.2%) | 1,227 (7.8%) | 974 (6.2%) | 2,095 (13.3%) |

| 4 drugs | 448 (2.8%) | 796 (5.1%) | 479 (3.0%) | 1,320 (8.4%) |

| 5 drugs | 73 (0.5%) | 512 (3.3%) | 309 (2.0%) | 904 (5.7%) |

| 6 drugs | 2 (0.01%) | 329 (2.1%) | 140 (0.9%) | 613 (3.9%) |

| 7 drugs | 0 | 222 (1.4%) | 72 (0.5%) | 389 (2.5%) |

| 8 drugs | 0 | 151 (1.0%) | 25 (0.2%) | 219 (1.4%) |

| 9 drugs | 0 | 106 (0.7%) | 1 (0.006%) | 146 (0.9%) |

| 10 drugs | 0 | 82 (0.5%) | 0 | 97 (0.6%) |

| 10+ drugs | 0 | 129 (0.8%) | 0 | 155 (1.0%) |

| Medications classified according to ATC | N (%) of patients |

|---|---|

| Alimentary tract and metabolism (A) | 2373 (15.1%) |

| Drugs used in diabetes (A10) | 1911 (12.1%) |

| Drugs for acid related disorders (A02) | 345 (2.2%) |

| Antidiarrheals, intestinal anti-inflammatories/anti-infectives (A07) | 53 (0.3%) |

| Laxatives (A06) | 36 (0.2%) |

| Drugs for functional gastrointestinal disorders (A03) | 22 (0.1%) |

| Digestives, incl. enzymes (A09) | 5 (0.03%) |

| Other alimentary tract and metabolism products (A16) | 1 (0.006%) |

| Blood and blood forming organs (B) | 4371 (27.8%) |

| Antithrombotic agents (B01) | 4332 (27.5%) |

| Antianemic preparations (B03) | 24 (0.15%) |

| Antihemorrhagics (B02) | 15 (0.1%) |

| Cardiovascular system (C) | 5859 (37.2%) |

| Lipid modifying agents (C10) | 2235 (14.2%) |

| Beta blocking agents (C07) | 1247 (7.9%) |

| Diuretics (C03) | 892 (5.7%) |

| Cardiac therapy (C01) | 780 (4.9%) |

| Calcium channel blockers (C08) | 390 (2.5%) |

| Agents acting on the renin-angiotensin system (C09) | 315 (1.9%) |

| Genito-urinary system and sex hormones (G) | 87 (0.5%) |

| Other gynecologicals (G02) | 87 (0.5%) |

| Systemic hormonal preparations, excl. sex hormones and insulins (H) | 1303 (8.3%) |

| Thyroid therapy (H03) | 1032 (6.6%) |

| Corticosteroids for systemic use (H02) | 260 (1.7%) |

| Pituitary and hypothalamic hormones and analogues (H01) | 11 (0.07%) |

| Antiinfectives for systemic use (J) | 648 (4.1%) |

| Antibacterials for systemic use (J01) | 601 (3.8%) |

| Antivirals for systemic use (J05) | 47 (0.3%) |

| Antineoplastic and immunomodulating agents (L) | 633 (4.02%) |

| Antineoplastic agents (L01) | 482 (3.1%) |

| Endocrine therapy (L02) | 64 (0.4%) |

| Immunosuppressants (L04) | 48 (0.3%) |

| Immunostimulants (L03) | 39 (0.25%) |

| Musculo-skeletal system (M) | 342 (2.2%) |

| Anti-inflammatory and antirheumatic products (M01) | 303 (1.9%) |

| Drugs for treatment of bone diseases (M05) | 34 (0.2%) |

| Muscle relaxants (M03) | 5 (0.03%) |

| Nervous system (N) | 11044 (70.1%) |

| Psycholeptics (N05) | 7831 (49.7%) |

| Anti-parkinson drugs (N04) | 1713 (10.9%) |

| Psychoanaleptics (N06) | 1259 (7.9%) |

| Analgesics (N02) | 236 (1.5%) |

| Other nervous system drugs (N07) | 5 (0.03%) |

| Antiparasitic products, insecticides and repellents (P) | 29 (0.18%) |

| Antiprotozoals (P01) | 29 (0.18%) |

| Respiratory system (R) | 780 (4.9%) |

| Drugs for obstructive airway diseases (R03) | 780 (4.9%) |

| Various (V) | 2 (0.01%) |

| All other therapeutic products (V03) | 2 (0.01%) |

| Almaty, Astana, Shymkent | Regions | p-value1 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients (n; % of cohort) | 11952 (21.8%) | 42875 (78.2%) | NA |

| Polytherapy share | 36.9% (4410/11952) | 41.5% (17792/42875) | <0.01 |

| Age, median [IQR] (years) | 41 [29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56] | 40 [29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54] | <0.01 |

| Comorbid drugs per patient, median [IQR] | 2 [1,2,3,4] | 2 [1,2,3] | <0.01 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).