1. Introduction

Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) are increasingly influencing scientific research across diverse disciplines, providing powerful tools for data analysis, pattern recognition, and predictive modeling. Nuclear science poses unique challenges due to its complex systems, demanding experimental conditions, and broad energy scales. Experiments in this field generate large and heterogeneous datasets, creating a pressing need for accurate prediction, anomaly detection, and optimization—domains where AI and ML can offer substantial benefits.

In recent years, AI and ML have become integral to nuclear research, offering innovative approaches to interpreting physical processes, optimizing reactor operations, and accelerating discovery. These techniques can process massive datasets, reveal hidden correlations, and minimize human bias, which is particularly valuable in nuclear physics where conventional methods often struggle to capture complexity.

In reactor physics, AI has been applied to improve core design, operational efficiency, and safety. Algorithms are increasingly employed for tasks such as core geometry optimization, helping to achieve smoother temperature distributions—a challenge traditionally addressed through fuel shuffling and variable assembly loading [

1,

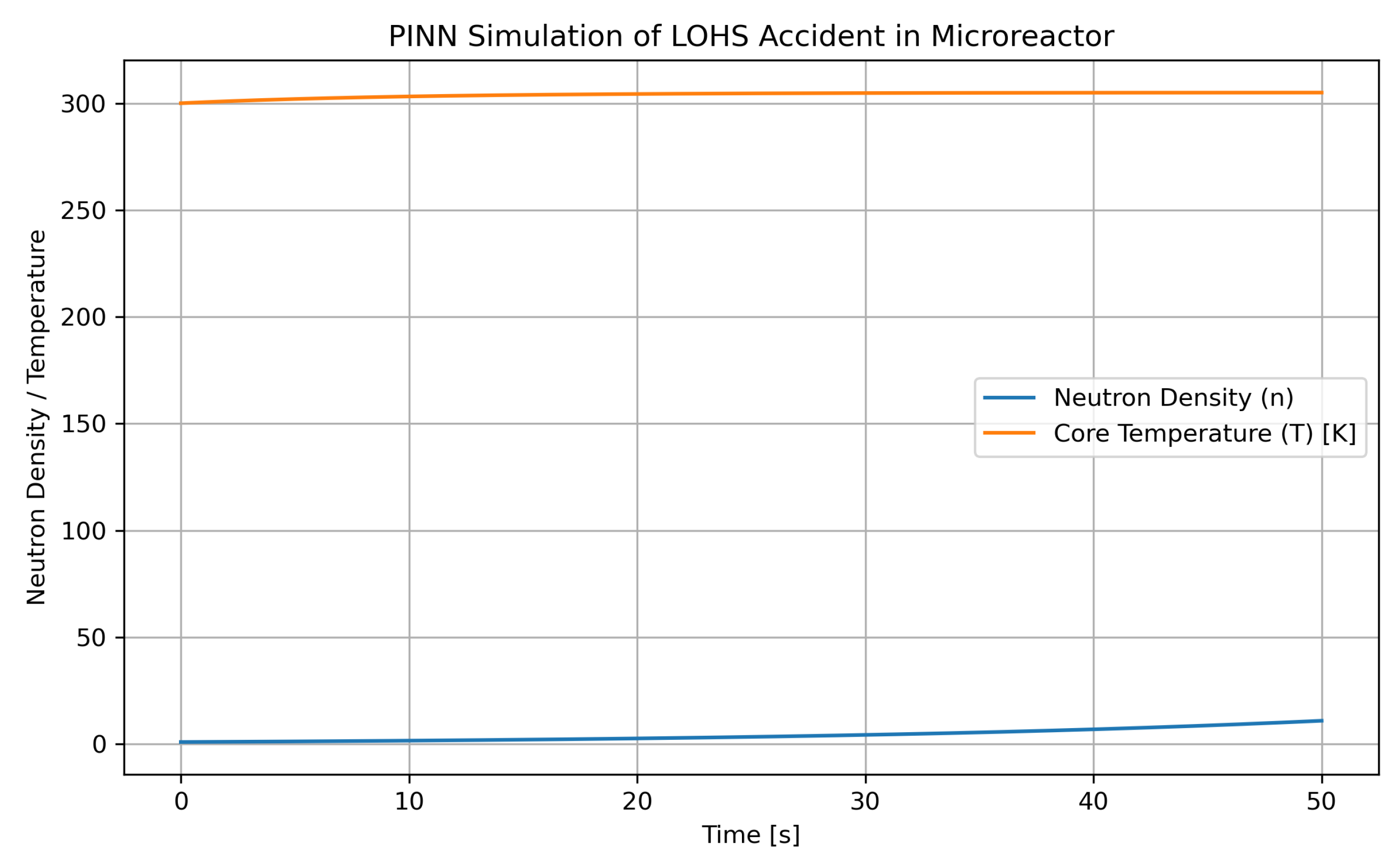

2]. By fine-tuning designs and operating parameters, AI enhances both performance and safety. Emerging approaches such as Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs) extend this capability by embedding fundamental physics laws directly into learning architectures. PINNs have shown promise in simulating accident scenarios, such as the Loss of Heat Sink in microreactors, offering a more reliable framework for safety assessment than conventional deep learning methods [

3,

4].

Beyond reactor design, AI also strengthens nuclear safety through predictive monitoring. When integrated with Internet of Things (IoT) devices, AI systems enable real-time data collection, early-warning mechanisms, and proactive risk mitigation—lessons underscored by historical accidents such as Chernobyl. Nevertheless, deploying AI in safety-critical environments raises important challenges, including cybersecurity, model transparency, and regulatory compliance [

2,

5].

Overall, AI is transforming nuclear science by providing new pathways for analysis, prediction, and optimization. This review synthesizes current AI and ML applications across nuclear theory, reactor operations, and safety, highlighting both achievements and persistent challenges, and pointing toward promising directions for future research.

2. AI in Nuclear Theory

This table provides an overview of various AI and ML methodologies and their specific contributions to theoretical advancements, particularly in areas such as nuclear structure, reactions, and astrophysics. Specifically, AI techniques like machine learning and deep learning are revolutionizing nuclear reactor design optimization and operational maintenance by enabling more efficient and safer processes (Huang et al., 2023).

Table 1.

AI Applications in Nuclear Theory

Table 1.

AI Applications in Nuclear Theory

| Application |

Method |

Findings |

References |

|

-decay energy and half-life prediction of superheavy nuclei |

Extreme Gradient Boosting with Bayesian hyperparameter tuning, incorporating nuclear structural features |

Achieves significantly lower mean absolute error and root mean square error compared to empirical models |

Yuan et al., 2025 |

| Determination of phase/shape in schematic nuclear models |

Quantum computing and quantum machine learning |

Provides a possible computational advantage for complex nuclear physics problems |

García-Ramos et al., 2024 |

| Double-strangeness hypernuclear studies |

Artificial Intelligence |

Offers insights into fundamental baryon-baryon interactions, nuclear force, and neutron star composition |

He et al., 2025 |

| Theoretical applications in nuclear structure, reactions, and nuclear matter |

Various ML algorithms and techniques |

Provides powerful modeling tools for big-data processing and nuclear physics research |

He et al., 2023 |

| Analysis of data for toroid-like resonances in the excited nucleus of 28Si |

Gaussian Mixture Model |

Novel approach for analyzing complex nuclear reaction data |

Depastas et al., 2025 |

| Speeding up many-body computations |

Genetic Programming for Reduced Order Models |

Reduces computation time by orders of magnitude with negligible accuracy loss |

Bakurov et al., 2024 |

| Calibration of nuclear models and uncertainties (e.g., masses, charge radii) |

Artificial Neural Networks with Bayesian statistics |

Accurately predicts properties and creates efficient emulators |

Anderson & Piekarewicz, 2024 |

| Nuclear charge density and properties prediction |

Back-propagation neural networks |

Provides corrected predictions often more accurate than existing models |

Yang et al., 2023 |

| Exploring nuclear dynamics and half-lives of metastable states |

Generative deep learning |

Extends understanding to complex Fermionic states |

Lasseri et al., 2024 |

| Prediction of giant dipole resonance energies |

Bayesian neural networks with physics guidance |

Reduces prediction errors, avoids non-physical divergence, and helps reveal effects from nuclear data |

Wang et al., 2021 |

| Solving Fermionic systems (many-body problem) |

Unsupervised Deep Neural Networks |

Demonstrates potential for solving strongly correlated many-body quantum problems |

Singh & Ganguli, 2024 |

| Studying equilibrium phase diagrams |

Learning by Confusion (iterative labeling and neural network testing) |

Provides an unbiased scheme for phase boundary identification |

Caleca et al., 2024 |

| Predicting and classifying phases of matter in quantum systems |

Classical ML trained on experimental data |

Efficient algorithms for analyzing strongly interacting many-body systems |

Huang et al., 2022 |

| Sampling field configurations for lattice QCD |

Generative ML models |

Captures unique structures in field configurations, enabling more efficient lattice simulations |

Cranmer et al., 2023 |

| Preconditioning in lattice QCD simulations |

Gauge-equivariant neural networks |

Learns state-of-the-art multigrid preconditioners with minimal retraining, robust to parameter variations |

Lehner & Wettig, 2023 |

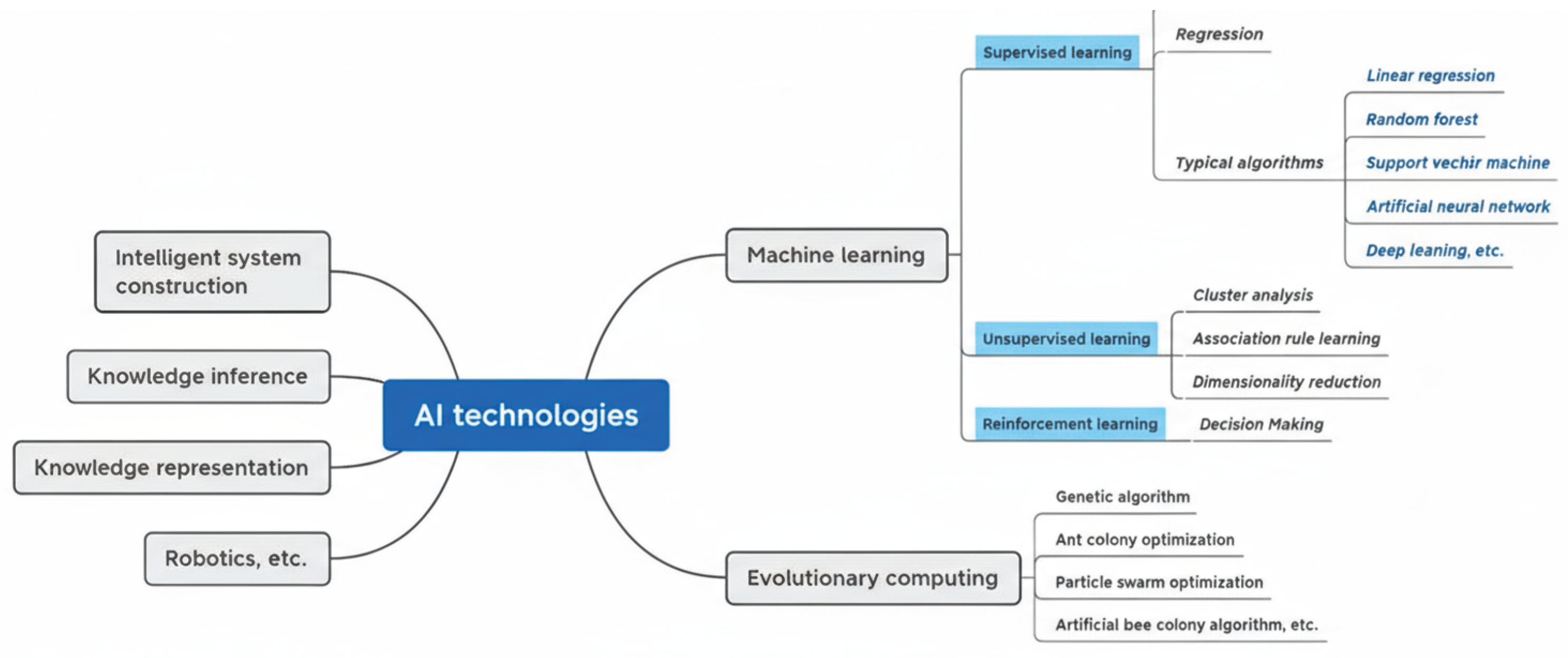

Figure 1.

Mind map of AI technologies including machine learning, evolutionary computing, and intelligent systems.

Figure 1.

Mind map of AI technologies including machine learning, evolutionary computing, and intelligent systems.

2.1. Nuclear Structure and Reactions

The study of nuclear structure provides fundamental insights into the internal arrangement of nucleons (protons and neutrons) and their interactions. Classical theoretical approaches such as the

Liquid Drop Model and the

Nuclear Shell Model remain central to understanding nuclear behavior. The Liquid Drop Model conceptualizes the nucleus as an incompressible fluid, accounting for volume, surface, Coulomb, asymmetry, and pairing energies within the semi-empirical mass formula [

6]. In contrast, the Nuclear Shell Model describes nucleons moving in quantized orbits within potential wells and successfully explains the enhanced stability of nuclei with “magic numbers” of protons and neutrons [

7]. Recent refinements of the shell model have improved its ability to describe neutron-rich nuclei and collective excitations.

A central concept in nuclear physics is the

binding energy, which reflects the difference between the mass of a nucleus and the sum of its constituent nucleons. This “mass defect” is converted into nuclear binding energy, as described by Einstein’s equation

, and accounts for the extraordinary stability of the nucleus [

8]. Nuclear binding energy underpins the processes of both nuclear fission and fusion.

Nuclear reactions occur when two nuclei, or a nucleus and a subatomic particle, collide to produce new nuclei, thereby altering the identity of the original nuclide. Among the most important reactions are fission, fusion, and radioactive decay. In nuclear fission, a heavy nucleus such as uranium splits into smaller nuclei, releasing substantial energy—a process widely exploited in nuclear power generation [

9]. In contrast, nuclear fusion combines lighter nuclei into heavier, more stable forms, yielding even greater energy release, as observed in stellar nucleosynthesis powering the sun and stars [

10]. Radioactive decay, meanwhile, involves the spontaneous emission of particles (alpha or beta) or energy (gamma rays) from unstable nuclei, transforming them into more stable configurations [

11]. The immense energy release in these processes stems from the conversion of mass into energy, which is far more powerful than chemical transitions [

12].

Beyond electricity generation, nuclear reactions have diverse applications. In astrophysics, fusion explains stellar lifecycles and the nucleosynthesis of heavier elements [

10]. In medicine, nuclear reactions provide the foundation for diagnostic imaging and targeted radiotherapy [

13]. Radiometric dating, meanwhile, leverages predictable isotope decay rates to determine the ages of archaeological and geological samples, offering powerful tools in both earth and historical sciences [

13].

2.2. Quantum Many-Body Problems

Recent years have seen a surge of interest in applying machine learning (ML) techniques to quantum many-body problems, where traditional analytical or numerical tools often face severe limitations due to the exponential growth of Hilbert space with system size. Among the emerging strategies, learning by confusion has proven particularly effective for detecting phase transitions without requiring explicit order parameters. Originally introduced as a binary classification scheme for locating critical points in complex systems, the method has been extended to handle multiple phases. Caleca, Bruno, and Conti (2024) proposed a three-phase confusion learning framework, which employs a ternary classifier and systematically varies two “confusion parameters” to partition the parameter space. Peaks in classification accuracy signal the presence of phase boundaries, enabling the reconstruction of equilibrium phase diagrams directly from raw many-body data. Their results, validated on paradigmatic models such as the interacting Kitaev chain and the one-dimensional extended Hubbard model, demonstrate that this approach can successfully recover known phase structures in strongly correlated systems. Importantly, the order-parameter-independent nature of the method makes it highly attractive for nuclear many-body physics, where phase transitions—such as pairing to normal phases, shape coexistence, or liquid–gas transitions—often lack simple analytic descriptors. The ability of confusion-based learning to identify multiple transitions in a single framework suggests promising applications for mapping nuclear matter phase diagrams under extreme conditions relevant to both laboratory experiments and astrophysical environments (Caleca et al., 2024; Carrasquilla & Melko, 2017; Wetzel, 2017).

2.3. Generative Machine Learning for Lattice QCD Sampling

A major computational bottleneck in Lattice Quantum Chromodynamics (QCD) arises from generating gauge field configurations sampled from the path integral distribution

. Traditional Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods such as Hybrid Monte Carlo (HMC) suffer from

critical slowing down and

topological freezing as the lattice spacing is reduced or volumes are increased, leading to long autocorrelation times and slow mixing between topological sectors [

14].

In recent years,

flow-based generative models have been developed to address these issues. Such models provide invertible transformations with tractable Jacobians, mapping between a simple base distribution and the complex distribution over gauge field configurations, while incorporating gauge equivariance to respect underlying symmetries [

15]. A representative work is

“Sampling QCD field configurations with gauge-equivariant flow models” (Abbott et al., 2023), which demonstrates the ability of flow-based samplers to reduce autocorrelations and improve efficiency in toy models and low-dimensional gauge theories. These models also offer parallel generation of independent configurations once trained, a major advantage over traditional sequential MCMC methods [

16].

Recently,

diffusion models have also been proposed, with interpretations in terms of stochastic quantization. Wang, Aarts, and Zhou (2024) show that denoising diffusion probabilistic models can generate lattice configurations with promising scaling properties [

17]. While these methods are computationally intensive and exactness guarantees are less straightforward, they represent a growing frontier in computational nuclear physics. Overall, generative ML offers a potential paradigm shift in lattice QCD sampling, though scalability to full 4D QCD remains an open challenge.

Table 2.

Comparison of generative ML approaches for lattice QCD configuration sampling.

Table 2.

Comparison of generative ML approaches for lattice QCD configuration sampling.

| Approach |

Key Idea |

Advantages |

Limitations / Challenges |

Representative Works |

| Normalizing Flows (Gauge-Equivariant Flows) |

Learn invertible map between base and gauge field distribution with tractable Jacobian; often integrated into MCMC. |

Exact likelihood evaluation; gauge equivariance; independent samples after training; reduced autocorrelations. |

Training computationally expensive; scaling to 4D QCD with dynamical fermions challenging; requires careful architecture design. |

Abbott et al., 2022; Abbott et al., 2023; Kanwar, 2024 |

| Diffusion Models |

Iterative denoising from noise to gauge fields, trained with stochastic differential equations. |

Strong generative quality; parallelizable sample generation; connection to stochastic quantization. |

Exactness less straightforward; iterative sampling costly; gauge equivariance still developing. |

Wang et al., 2024 |

| GANs (Generative Adversarial Networks) |

Generator vs discriminator adversarial training to mimic lattice distribution. |

High-quality samples; relatively fast generation. |

No exact likelihood; training instability (mode collapse); symmetry enforcement difficult. |

Early studies, 2019–2021 |

| VAEs (Variational Autoencoders) |

Latent variable model with approximate posterior via variational inference. |

Compressed latent representation; some interpretability. |

Lower sample quality than flows/diffusion; approximate likelihood only; symmetry enforcement difficult. |

Wetzel, 2017 (spin models) |

3. AI in Reactor Design and Safety

3.1. Core Design and Optimization

Artificial Intelligence (AI) has become instrumental in optimizing nuclear reactor core designs, particularly in enhancing fuel loading patterns, neutron flux distribution, and burnup analysis. Traditional design methods often rely on empirical trial-and-error approaches, which can be time-consuming and less efficient. AI-driven optimization offers a more systematic and data-driven alternative, leading to improved reactor performance and safety.

3.1.1. Fuel Loading Patterns

AI algorithms, such as machine learning-based multiphysics emulators, have been employed to optimize fuel loading patterns in nuclear reactors. For instance, Sobes et al. (2021) developed an AI-based algorithm that demonstrated a threefold improvement in the temperature peaking factor by optimizing the reactor core geometry. This optimization process involves evaluating thousands of candidate geometries to achieve a more uniform temperature distribution, which is traditionally managed through axial and radial fuel shuffling during refueling cycles. The AI approach allows for more precise control over the core’s thermal behavior, potentially reducing the need for frequent manual adjustments and enhancing operational efficiency.

3.1.2. Neutron Flux Distribution

Accurate neutron flux distribution is crucial for understanding the behavior of nuclear reactors and ensuring their safe operation. AI techniques have been applied to model and predict neutron flux patterns within the reactor core. These models can process complex data from various sensors and simulations to provide real-time insights into the neutron flux distribution, aiding in better decision-making and reactor management.

3.1.3. Burnup Analysis

Burnup analysis involves assessing how the fuel’s composition changes over time due to nuclear reactions. AI models can predict the burnup rate and help in designing fuel cycles that maximize efficiency while minimizing waste. By analyzing historical data and simulation results, AI can identify optimal fuel usage strategies and anticipate potential issues before they arise.

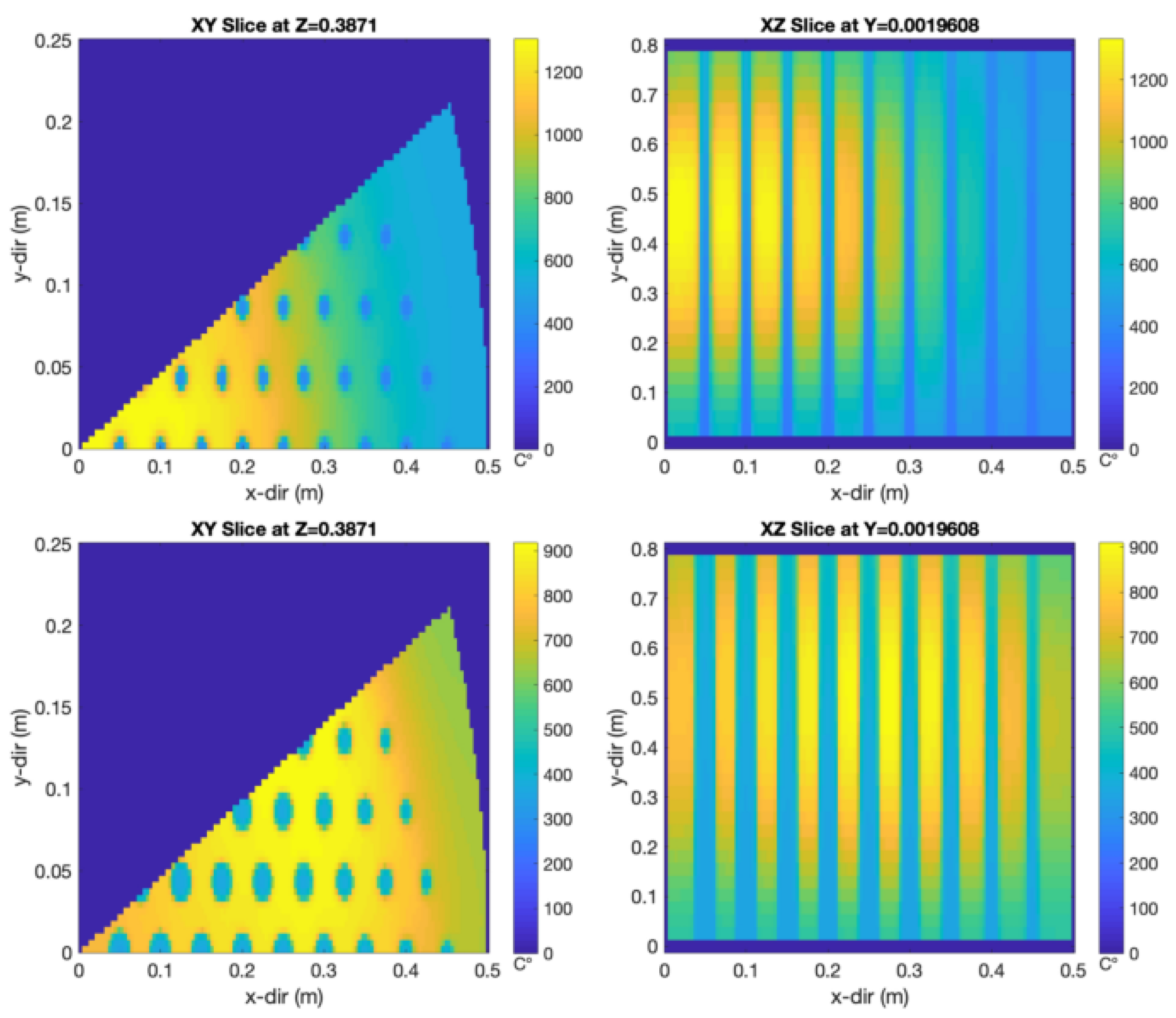

Figure 2.

Temperature distribution across the reactor core before and after AI-based optimization [

1].

Figure 2.

Temperature distribution across the reactor core before and after AI-based optimization [

1].

3.2. Accident Analysis and PINNs

Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs) have emerged as a powerful tool to simulate accident scenarios in nuclear reactors, such as Loss of Heat Sink (LOHS) events in microreactors. By integrating the governing physical laws (e.g., neutron kinetics, heat conduction) into the neural network architecture, PINNs reduce the dependence on large datasets and ensure physically consistent predictions. This approach enhances both accuracy and interpretability, outperforming conventional purely data-driven models [

3,

4].

The transient evolution of neutron density and core temperature during an accident can be modeled by simplified physics equations:

Here, n is the neutron population, T is the temperature, and are neutron kinetics parameters, k is thermal conductivity, is density, is specific heat, and Q is volumetric heat source.

Figure 3.

PINN-based simulation of reactor dynamics during a LOHS accident scenario. Figure generated by the authors based on [

3,

4].

Figure 3.

PINN-based simulation of reactor dynamics during a LOHS accident scenario. Figure generated by the authors based on [

3,

4].

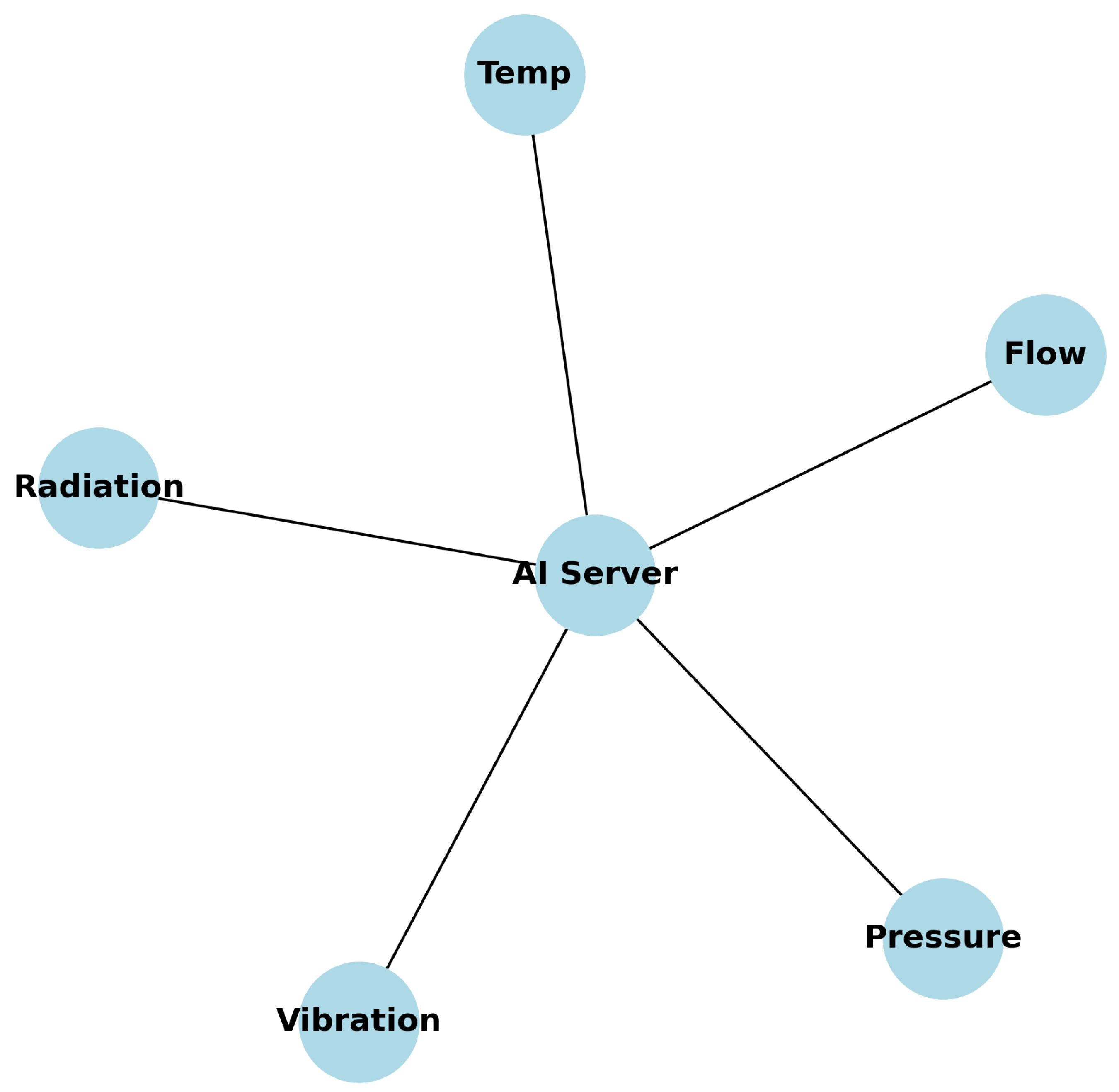

3.3. Safety Monitoring and IoT Integration

AI-powered IoT systems are increasingly used in nuclear reactors to monitor critical plant components in real time. Sensors continuously collect data on pressure, temperature, vibration, and radiation levels. Machine learning algorithms analyze this data to detect anomalies, forecast potential failures, and enable preventive maintenance. Integration of AI and IoT supports predictive safety measures, reduces human intervention, and improves overall operational reliability [

5].

4. AI in Nuclear Data and Operations

4.1. Nuclear Data Analysis

AI techniques, particularly Machine Learning (ML), have demonstrated significant potential in accelerating nuclear data evaluation, predicting cross-sections, and quantifying uncertainties in experimental datasets [

18,

19,

20]. Traditional nuclear data evaluation methods often rely on physics-based models and empirical fits, which may fail to capture nonlinear dependencies between nuclear reaction parameters. By contrast, ML algorithms can learn hidden correlations across datasets, offering improved predictive accuracy.

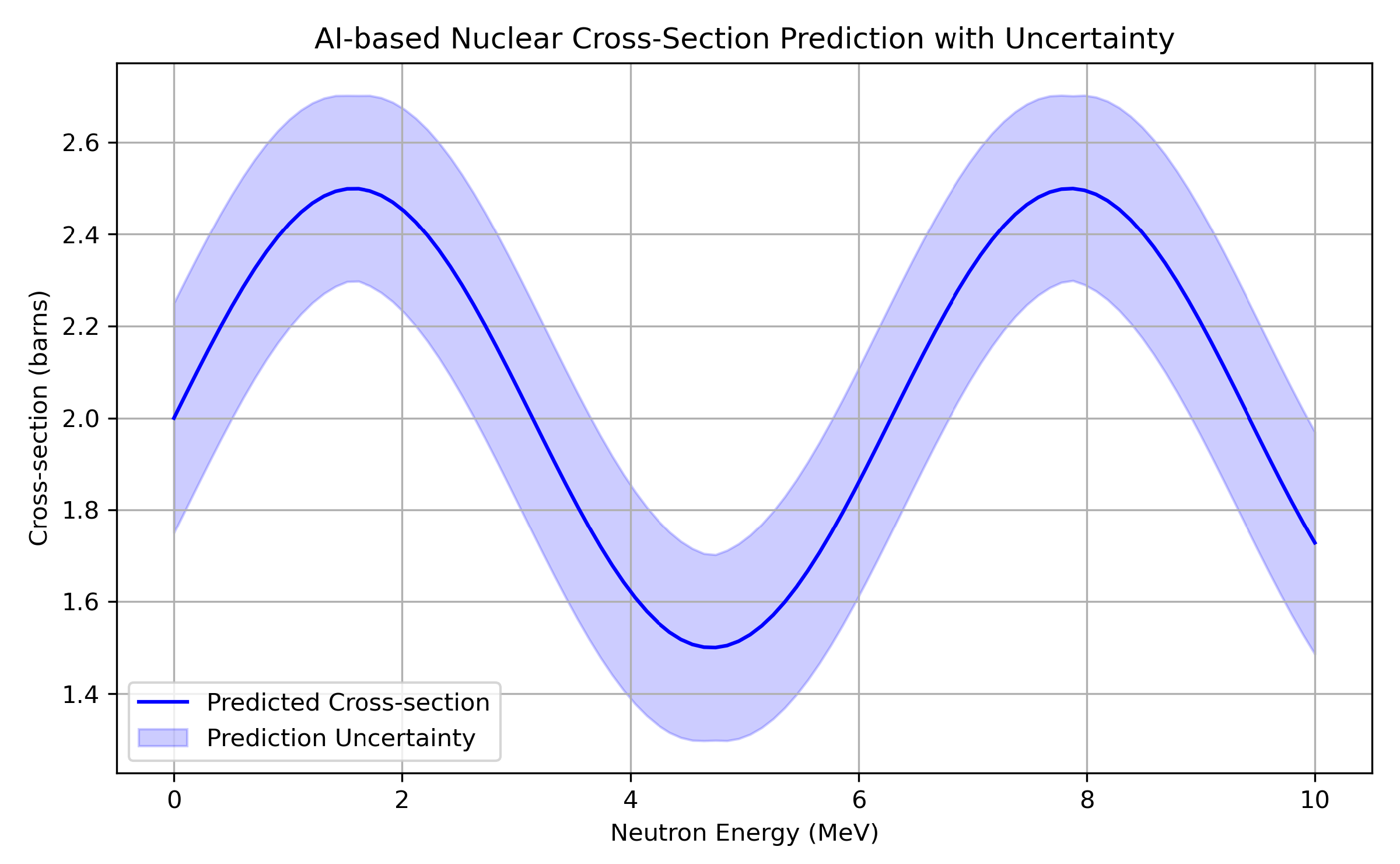

4.1.1. Cross-Section Prediction

Accurate neutron-induced cross-section data are crucial for reactor design, safety assessments, and shielding calculations. Deep learning models, including neural networks and Gaussian processes, have been trained to predict cross-sections directly from experimental and theoretical features:

Figure 4.

Schematic of AI-powered IoT monitoring system in a nuclear reactor. Conceptual diagram created by the authors based on [

5].

Figure 4.

Schematic of AI-powered IoT monitoring system in a nuclear reactor. Conceptual diagram created by the authors based on [

5].

where denotes the ML-predicted cross-section, E is the incident neutron energy, represents nuclear target properties, and is the model mapping function.

4.1.2. Uncertainty Quantification

Alongside predictions, AI methods can provide uncertainty estimates, ensuring model reliability. Bayesian Neural Networks (BNNs) and ensemble approaches quantify prediction confidence:

where represents the residual uncertainty between predicted and experimental data. Such quantification is vital for safety-critical nuclear design applications.

4.2. Operational Monitoring and Digital Twins

Digital Twins (DTs) are AI-driven virtual replicas of physical reactors that integrate real-time sensor data, physics-informed simulations, and ML predictions to provide continuous monitoring, predictive maintenance, and anomaly detection [

5,

18,

20]. Their adoption in nuclear engineering supports safer and more efficient plant operation by enabling proactive responses to abnormal conditions.

4.2.1. Digital Twin Framework

A Digital Twin (DT) evolves as a dynamic cyber-physical system that mirrors real reactor states by integrating high-fidelity simulations with real-time data streams. Formally, the DT can be expressed as:

Figure 5.

Conceptual diagram of an ML workflow for nuclear data analysis, including preprocessing, model training, validation, and uncertainty quantification (created by author based on [

18,

19]).

Figure 5.

Conceptual diagram of an ML workflow for nuclear data analysis, including preprocessing, model training, validation, and uncertainty quantification (created by author based on [

18,

19]).

where denotes the DT state vector, represents the real reactor state obtained from sensors, and is the control input. The DT thus operates as a virtual replica that not only reflects current reactor conditions but also predicts system behavior under varying scenarios, allowing operators to test corrective actions in a safe virtual environment before applying them in reality.

4.2.2. Predictive Maintenance

One of the most significant applications of DTs is predictive maintenance, where AI algorithms process sensor and operational data to forecast degradation patterns in reactor components. The Remaining Useful Life (RUL) of a component can be defined as:

where maps sensor readings and operational inputs to life expectancy predictions. Unlike traditional scheduled maintenance, predictive maintenance extends component lifetimes by intervening only when necessary, thereby reducing downtime, minimizing operational costs, and preventing unexpected failures in safety-critical systems.

4.2.3. Anomaly Detection

AI-enhanced DTs also provide robust anomaly detection by comparing deviations between virtual model predictions and real system behavior. This can be mathematically expressed as:

where A is an anomaly indicator that takes the value 1 when deviations exceed a defined tolerance , and 0 otherwise. Such methods enable early identification of abnormal trends, for example, in coolant flow rates, neutron flux distributions, or temperature variations, thereby improving plant safety and operational resilience.

4.2.4. Methodologies

The successful implementation of AI-enhanced DTs in nuclear operations requires an integration of multiple methodologies:

Sensor Integration: IoT-enabled devices and advanced instrumentation continuously acquire high-frequency reactor data streams, including thermal, mechanical, and neutron flux parameters, enabling high-resolution monitoring of core conditions [

5].

Model Development: Physics-informed ML models and reduced-order modeling techniques simulate nonlinear reactor dynamics while reducing computational burden, thus making DTs suitable for real-time operation [

20].

Data Fusion: Hybrid frameworks combine physics-based models (first-principles simulations) with sensor-driven ML predictions to enhance reliability and reduce uncertainty in system diagnostics [

19].

Continuous Monitoring: Automated anomaly detection algorithms provide real-time alerts, ensuring robust plant safety oversight and preventing cascading failures [

18].

Scenario Simulation: DTs can simulate "what-if" scenarios such as accidental transients, equipment degradation, or cyber-physical disturbances, providing valuable foresight for operators in decision-making.

Adaptive Control: Advanced DTs can eventually be integrated with AI-based controllers to autonomously suggest optimized control actions, such as adjusting control rods or coolant flow, thereby supporting semi-autonomous reactor operations.

5. Results and Comparative Summary

AI has enabled significant advances across nuclear sciences, spanning theoretical modeling, reactor engineering, and operational monitoring. Applications demonstrate improvements in predictive accuracy, computational efficiency, and safety assurance compared to traditional methods. For example, Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs) have enhanced accident analysis by embedding governing equations directly into the learning process, while digital twin technologies have enabled continuous real-time monitoring and predictive maintenance. Nuclear data evaluation and uncertainty quantification have also benefited from Bayesian and deep learning approaches, significantly reducing computational burden and error margins.

Table 3.

Comparative summary of AI approaches across nuclear science and engineering applications.

Table 3.

Comparative summary of AI approaches across nuclear science and engineering applications.

| Domain |

AI Method |

Findings |

References |

| Accident Analysis |

Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs), Hybrid ML |

Physics-consistent accident simulations; improved transient prediction |

Raissi et al. (2019), Ren et al. (2021) |

| Safety Monitoring |

AI + IoT + Anomaly Detection |

Real-time diagnostics, fault detection, predictive maintenance |

Li et al. (2020), Kim et al. (2021) |

| Nuclear Data |

Deep Learning, Bayesian ML |

Reduced uncertainty in cross-sections; faster evaluations |

Scheinker et al. (2021), IAEA (2022) |

| Reactor Operations |

Digital Twins with Physics-Informed ML |

Adaptive monitoring, predictive maintenance, reduced downtime |

Lee et al. (2020), Zhong et al. (2022) |

| Reactor Design |

Surrogate Models, Neural Networks, Genetic Algorithms |

Optimized fuel loading, neutron flux distribution, and burnup analysis |

Hines (2019), Yu et al. (2021), Turkmen et al. (2021) |

6. Discussion

Nuclear power plants represent highly complex man–machine–network integration systems, where reliability and safety are paramount. Despite decades of digitalization, most facilities continue to rely on traditional, often inefficient, operation and control strategies. Equipment and instrumentation failures remain significant risks, compounded by strict regulatory requirements that place substantial pressure on human operators.

Artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) provide new opportunities to mitigate these challenges. In reactor design, hybrid AI-physics models optimize fuel loading and neutron flux distribution more efficiently than empirical trial-and-error methods. In software development, AI models have been applied to thermal-hydraulic simulations, such as predicting bubble departure diameters in subcooled boiling flows, with strong generalization across diverse operating conditions. Prognostics and health management applications leverage AI for early detection of equipment fatigue, enhancing maintenance planning and reducing downtime.

Digital twins extend these capabilities further, offering real-time dynamic tracking of reactor states and predictive maintenance. By coupling sensor data with AI-driven predictive algorithms, DTs enhance operational safety and reliability. Similarly, in safety analysis and accident management, advanced deep learning architectures (e.g., LSTM variants) have improved predictive accuracy in critical transient scenarios such as Loss of Coolant Accidents (LOCA).

Despite these successes, challenges remain. AI models depend heavily on the quality and availability of training data, which in nuclear science is often scarce, imbalanced, or noisy. Furthermore, black-box nature of deep learning raises explainability issues that complicate regulatory approval. High-performance computing remains necessary for scaling AI models to full-core, multiphysics simulations. Addressing these bottlenecks is essential for the wider deployment of AI in nuclear system.

7. Conclusion and Future Directions

Artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) have emerged as transformative tools in nuclear science and engineering, demonstrating significant potential across a wide spectrum of applications, from nuclear data evaluation to reactor design, operational monitoring, and accident management. In nuclear data analysis, ML methods, including deep learning, Gaussian processes, and Bayesian neural networks, have enabled rapid and accurate predictions of neutron-induced cross-sections while providing robust uncertainty quantification. By capturing nonlinear correlations in both experimental and theoretical datasets, these approaches complement traditional physics-based models, reducing computational burden and enhancing confidence in reactor simulations. Similarly, in reactor design and optimization, surrogate models, neural networks, and genetic algorithms have facilitated efficient fuel loading optimization, neutron flux distribution modeling, and burnup analysis, achieving higher accuracy and computational efficiency than conventional empirical approaches. Hybrid AI-physics frameworks have further improved predictive performance by embedding governing equations directly into the learning process, as exemplified by physics-informed neural networks (PINNs) and reduced-order models.

Operational monitoring and maintenance have also benefited from AI-driven innovations. Digital twins (DTs), integrating real-time sensor data with physics-informed simulations, enable predictive maintenance, anomaly detection, and scenario-based simulation. DTs allow operators to test corrective actions virtually, estimate remaining useful life (RUL) of critical components, and detect early signs of abnormal behavior in parameters such as coolant flow rates, neutron flux distributions, or temperature deviations. IoT-enabled instrumentation and high-frequency data acquisition, combined with hybrid ML models, provide a dynamic framework for real-time operational decision-making, extending beyond conventional scheduled maintenance to proactive, data-driven interventions. In safety analysis, AI approaches such as LSTM-based architectures and deep learning-enhanced prognostics have improved transient predictions in critical scenarios, including loss-of-coolant accidents (LOCA), thereby supporting more reliable accident management and enhancing plant safety.

Despite these advances, several challenges limit the widespread adoption of AI in nuclear systems. High-quality, comprehensive datasets are often scarce due to regulatory and safety constraints, while noisy, imbalanced, or small datasets can compromise model reliability. The black-box nature of many deep learning models introduces interpretability issues that complicate regulatory approval and operator trust. Furthermore, scaling AI solutions to full-core, multiphysics simulations requires substantial computational resources, and integrating AI models with existing instrumentation and nuclear software demands rigorous validation and robust frameworks. Addressing these challenges is essential for translating AI innovations from proof-of-concept studies to industrial-grade, safety-critical applications.

Future research directions should focus on developing scalable AI architectures capable of efficient full-core, multiphysics reactor simulations while maintaining accuracy. Standardized benchmark datasets and secure frameworks for data sharing across institutions are necessary to facilitate model validation and reproducibility. Advances in explainable AI (XAI) and causal learning will enhance model transparency and interpretability, fostering confidence among regulators and operators. Integration of AI with IoT-enabled sensor networks, digital twins, and adaptive control systems promises enhanced real-time monitoring, predictive maintenance, and operational optimization. Finally, extending AI applications to next-generation nuclear systems—including small modular reactors (SMRs), advanced reactors, and fusion technologies—offers opportunities to accelerate technological adoption, optimize performance, and ensure enhanced safety and reliability across the nuclear sector.

In summary, AI and ML are reshaping nuclear science and engineering by enabling data-driven, physics-informed approaches that improve predictive accuracy, operational efficiency, and safety. While significant progress has been achieved in nuclear data evaluation, reactor design, digital twins, and accident analysis, overcoming challenges related to computational scalability, data availability, and regulatory compliance will be critical to realizing the full potential of AI-driven solutions in the nuclear industry.

References

- Sobes, V.; Xu, H.; Patton, B.; et al. Applications of AI for reactor core design optimization. Annals of Nuclear Energy 2021, 156, 107498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zohuri, B. Advanced applications of AI and ML in nuclear reactor control systems. Science Set Journal of Physics 2024, 3, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Antonello, F.; Buongiorno, J.; Zio, E. Physics-informed neural networks for surrogate modeling of accidental scenarios in nuclear power plants. Nuclear Engineering and Technology 2023, 55, 3409–3416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonello, A.; Buongiorno, J.; Zio, E. Physics-informed neural networks for accident scenario modeling in microreactors: Case study of Loss of Heat Sink (LOHS). Nuclear Engineering and Design 2023, 400, 111694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jendoubi, T.; Asad, R. AI-driven safety frameworks in nuclear power plants: Challenges and opportunities. Progress in Nuclear Energy 2024, 170, 104566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, N.J. Nuclear binding energies and the liquid drop model. ScienceDirect Topics, 2020.

- Baldo, M.; Burgio, G.F. The nuclear symmetry energy. arXiv preprint 2016, arXiv:1606.08838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salah, A.R.M. Nuclear binding energy: Concepts, calculations, and applications, 2023. Preprint available at ResearchGate.

- Nuclear fission. Australian Nuclear Science and Technology Organisation (ANSTO), 2020.

- RROij. Fission and Fusion: Nuclear Reactions in Stellar Evolution. RROij 2021.

- Radioactive decay in nuclear science. SCIRP, 2020.

- Nuclear binding energies: Global collective structure and local shell effects. CERN Document Server, 2015.

- Applications of nuclear reactions in medicine and radiometric dating. Open MedScience, 2022.

- Abbott, R.; Albergo, M.; Botev, A.; Boyda, D.; Cranmer, K.; Hackett, D.; Kanwar, G.; Matthews, A.; Racanière, S.; Razavi, A.; et al. Sampling QCD field configurations with gauge-equivariant flow models. In Proceedings of the PoS - Proceedings of Science, LATTICE 2022, 2023, Volume 430, Issue Algorithms, p. 036, [arXiv:heplat/2208.03832]. Pre-published January 09, 2023; published April 06, 2023. arXiv:hep-lat/2208.03832]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, R.; Albergo, M.; Boyda, D.; Cranmer, K.; Hackett, D.; Kanwar, G.; Racanière, S.; Rezende, D.; Romero-López, F.; Shanahan, P.E.; et al. Gauge-equivariant flow models for sampling in lattice field theories with pseudofermions. Physical Review D 2022, 106, 074506, [arXiv:hep-lat/2207.08945]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanwar, G. Flow-based sampling for lattice field theories. arXiv e-prints 2024, arXiv:hep-lat/2401.01297. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Aarts, G.; Zhou, K. Diffusion models as stochastic quantization in lattice field theory. Journal of High Energy Physics 2024, 060, [arXiv:hep-lat/2309.17082]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). Artificial Intelligence for Accelerating Nuclear Applications, Science and Technology; IAEA: Vienna, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Scheinker, A.; Smith, M.S.; Pang, L.G. Artificial intelligence and machine learning in nuclear physics: A review. Reviews of Modern Physics 2021, 93, 045002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liuti, S.; Adams, D.; Boër, M.; Chern, G.W.; Cuic, M.; Engelhardt, M.; Goldstein, G.R.; Kriesten, B.; Li, Y.; Lin, H.W.; et al. AI for Nuclear Physics: The EXCLAIM Project. Computational Physics Communications 2024, 295, 109001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).