1. Introduction

Aquaculture has emerged as one of the fastest-growing food production sectors worldwide, providing both nutritional and socio-economic benefits. According to the FAO (2022), aquaculture supplies more than half of all fish consumed globally. Fish and other aquatic foods are not only an important source of protein but supply vital micronutrients such as omega-3 fatty acids, iron, and zinc. For Sub-Saharan Africa, aquaculture contributes to food and nutrition security, employment, and income generation for millions of smallholder farmers and their families. However, conventional aquaculture practices have been increasingly scrutinized for their environmental and social impacts, including water overuse, nutrient discharge into surrounding ecosystems, food safety concerns and unsustainable dependence on imported fishmeal and fish oil for feed (Greenfeld et al. 2022; Ogunji and Wuertz, 2023). Nigeria is the second biggest aquaculture producer in Africa and African Catfish (Clarias gariepinus) represents approximately 60% of national aquaculture production and plays a critical role in domestic protein supply and livelihoods (Ogunji & Wuertz, 2023). Yet Nigerian aquaculture remains dominated by smallholder pond and cage systems that often rely on water-intensive and environmentally unsustainable methods. Olagunju (2024) argues small-scale producers using conventional stagnant-water systems dominate Nigerian aquaculture. Challenges include effluent discharge into water bodies, unreliable access to high-quality feed, weak regulatory enforcement, and low consumer trust in food safety (Ogunji & Wuertz, 2023, Benjamin et al., 2020, 2025). A similar trend is observed among actors along the value chain, especially processor of smoked African Catfish, which largely supply the main markets that are often informal in nature. Very little is known about the food safety measures put in place by processors, as most do not have the National Agency for Food and Drug Administration and Control (NAFDAC) certification. These processors operate with hardly any oversight that may put a large portion of the population at risk in the event of contamination outbreak. Given some of these limitations, there is an urgent need for production systems that are more climate-smart, water-efficient, safe and socially sustainable. Against this backdrop, aquaponics and Recirculating Aquaculture Systems (RAS) have gained international recognition as transformative technologies for sustainable aquaculture. RAS are land-based, closed-loop systems that reuse up to 90–99% of water by filtration, oxygenation, and recirculation (Nie & Hallerman, 2021). Effluents are treated rather than discharged into the environment, greatly reducing water withdrawal and nutrient pollution. Aquaponics further integrates RAS with hydroponics, enabling fish waste to serve as fertilizer for plant growth, thereby producing both fish and vegetables in a single system. This dual production has been described as a prime example of circular economy innovation in agriculture (Debroy et al. 2025).

Global studies demonstrate the environmental advantages of these systems. Ravani et al. (2024) found that vertical decoupled aquaponics reduced environmental footprints by more than 40% compared to open-field horticulture, especially when combined with renewable energy sources. Chen et al. (2020) and van der Doorn et al. (2022) claim that aquaponics substantially increased water-use efficiency while maintaining profitability relative to hydroponics. Greenfeld et al. (2022) argue that aquaponics generally exhibits lower land and water footprints and reduced eutrophication potential compared to separate fish and vegetable systems, although high energy inputs remain a persistent challenge. These findings are particularly relevant for Nigeria, where water resources are contested and food safety concerns are pressing. Recent studies provide encouraging evidence that aquaponics and RAS can be locally adapted in Nigeria. The SANFU project in Lagos tested a small-scale aquaponics and RAS prototype for African Catfish production and found it technically feasible for peri-urban farming, although high electricity costs and equipment imports constrained economic viability (Benjamin et al., 2020, 2022). Engle et al. (2021) found that profitability in RAS depends on stocking density, feed conversion, and market premiums, highlighting the importance of cost-benefit analysis. Adeyemi et al. (2024) demonstrated that the use of local materials (e.g., rice husk, palm kernel shells) in aquaponics design can reduce reliance on expensive imports and enhance sustainability. Similarly, Kasim et al. (2023) highlighted the potential of aquaponics for sustainable food security in northern Nigeria but noted limited adoption due to low awareness and inadequate training. It is worth noting that the adoption of aquaponics and RAS remains limited (<1%) in Nigeria due to technical, financial, and market constraints (Akinwole & Faturoti, 2007; Benjamin et al., 2020). This is while aquaponics and RAS in the rest of the world are increasingly integrated into urban farming and circular economy strategies. The European Union’s Green Deal and Farm-to-Fork Strategy explicitly recognize aquaponics as a pathway to sustainable food production. However, scaling aquaponics in urban areas comes with significant challenges ranging from high start-up costs for infrastructure, higher energy demands for pumping, regulatory ambiguity regarding food safety to specialized technical skills (van der Doorn et al., 2022). Furthermore, there is a lack of region-specific data on profitability, financial sustainability, gender participation, employment generation, and contributions to food and nutrition security under local market conditions. These developments justify a comprehensive value chain analysis of conventional aquaculture, aquaponics, and RAS in Nigeria. Value chain studies (Fabre et al., 2021; TCI, 2022) emphasize functional, social, environmental, and profitability dimensions, which guide the present analysis. Thus, this report addresses these gaps by applying the Value Chain Analysis for Development (VCA4D) framework to aquaponics and RAS in Nigeria. Specifically, it seeks to:

- A.

Map the functional organization of conventional, aquaponics, and RAS value chains, identifying actors, linkages, and governance structures.

- B.

Assess profitability through cost–benefit and operating account analyses, comparing aquaponics and RAS with conventional systems.

- C.

Evaluate social impacts in terms of livelihoods, gender equity, food and nutrition security, and working conditions.

- D.

Analyze environmental impacts using True Cost Accounting (TCA) to quantify water use and ecosystem externalities.

Given the broader importance of aquaponics and RAS for Africa, this report contributes to the literature on sustainable aquaculture and food system resilience. It demonstrates how agri-innovations such as aquaponics and RAS, compared to conventional systems, can enhance resource efficiency, improve food safety, and contribute to socio-economic development. Moreover, it provides actionable insights for policymakers, investors, and practitioners seeking to foster climate-smart, sustainable, and inclusive aquaculture value chains across Africa.

2. Methodology

This study employs a multi-dimensional methodological framework to examine the value chain of conventional aquaculture, aquaponics, and RAS in Nigeria. The framework is adapted from the VCA4D tool developed by the European Commission (Fabre et al. 2021). VCA4D is a robust methodology designed to assess agri-food value chains across four pillars: functional, profitability (economic), social, and environmental dimensions. By integrating these perspectives, the framework allows for a holistic evaluation of aquaculture (innovations) in terms of efficiency, sustainability, and inclusivity. The selection of this framework is justified on three grounds. First, aquaponics and RAS represent agri-innovation with complex interactions across resource use, market structures, and social systems. Second, Nigeria presents a dual-market structure, informal (dominant) and formal markets, with differentiated value chain dynamics, requiring nuanced tools for analysis (Ogunji & Wuertz, 2023). Finally, combining profitability, environmental sustainability, and social inclusion resonates with the European and African Union strategies such as Farm to Fork, Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), and Food Safety, CAADP (Comprehensive Africa Agriculture Development Program) Strategy and Action Plan 2026-2035, Food Safety Strategy for Africa 2022-2036.

A survey was administered to three conventional aquaculture producers, two aquaponics and RAS facilities in Lagos State, as well as three processors from Ogun State, Nigeria. Respondents were selected through purposive sampling to capture actors directly engaged in aquaponics, RAS, or conventional African Catfish farming. There was a stakeholder engagement event organized with cooperatives to validate profitability and social impact perceptions. Furthermore, secondary data, data from the aquaponics prototypes at Aglobe Development Center and artisanal processors enabled data triangulation.

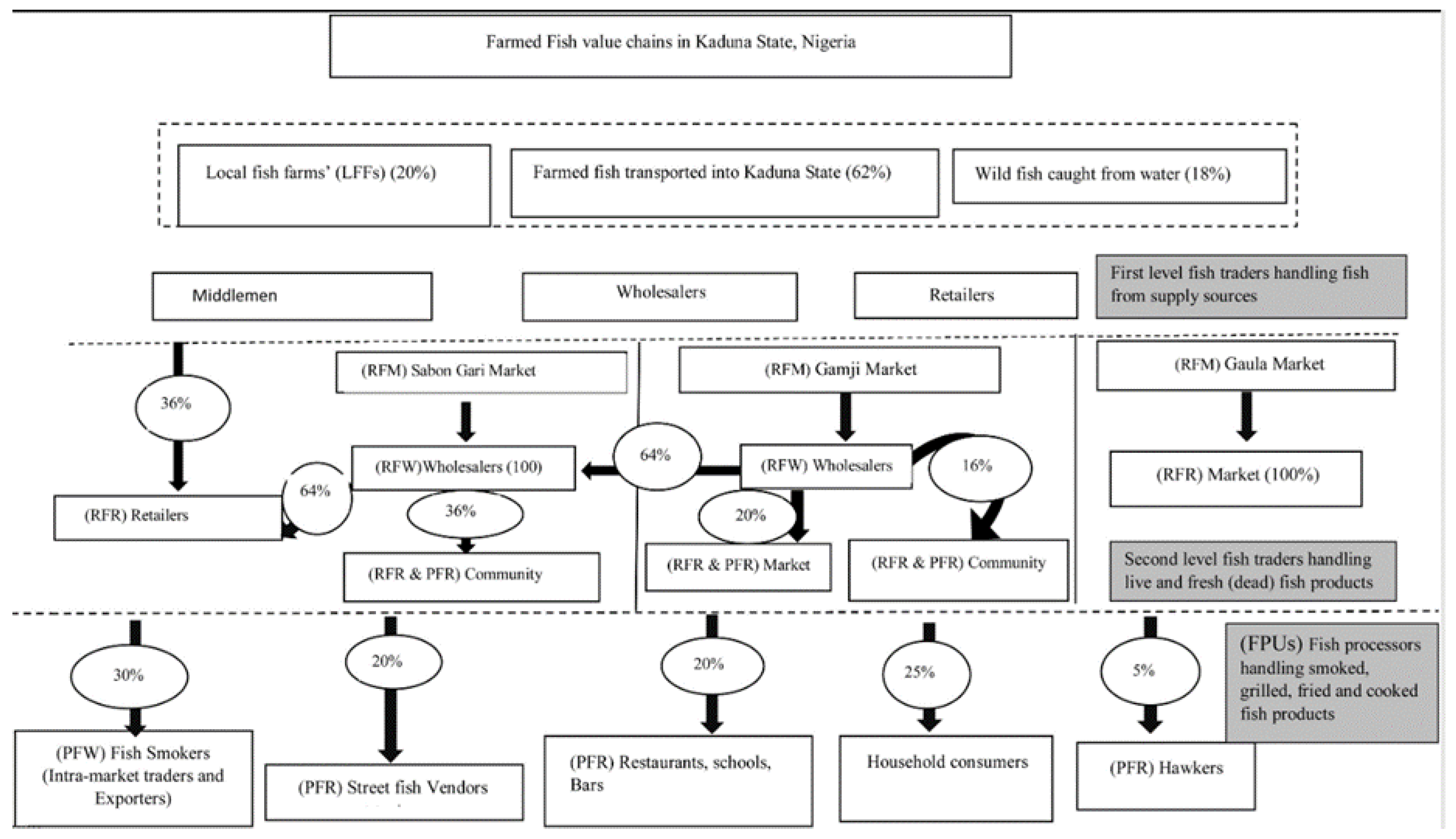

The functional analysis focuses on mapping actors, flows, and governance similar to Grema et al., (2020) for the farmed fish value chain in (northern) Nigeria (see

Figure 1). Given its strong regional focus and omission of governance structure, this may misrepresents aquaculture value chain for the entire country. Taylor (2005) argue for identifying areas of improvement in value stream mapping (VSM) that this study seeks to achieve.

Thus, this study develops value stream maps for conventional aquaculture, aquaponics, and RAS in Nigeria. For mapping, core actors that are involved in value and supply chain are depicted except retailers and consumers. These include input suppliers (e.g., hatcheries, feed suppliers, and equipment vendors), producers (e.g., micro, small-scale farms), processors (e.g., artisanal), business and food safety enabling institutions (i.e., the NAFDAC). This mapping also show the flow of activities from inputs to information flows through the governance structure - traceability, safety certification (Coote et al., 2019; Desclée et al., 2019). Thus, the analysis enables identification of structural bottlenecks and opportunities.

Given that profitability (economic pillar) analysis is central to assessing financial sustainability. The study also adopts a simple benefit-cost analysis (see

Table 1) consistent with VCA4D and agricultural economics standards (Fabre et al., 2021). This includes computing the operating account, i.e., costs and revenues for producers and processors. The components of these accounts are intermediate consumption (notably for feed, fingerlings, water, electricity), labor (i.e., paid/unpaid, valued at shadow wage rates), depreciation, taxes, subsidies, and revenues included sales and own consumption. This method accounts for opportunity costs of unpaid family labor, ensuring more accurate profitability estimates.

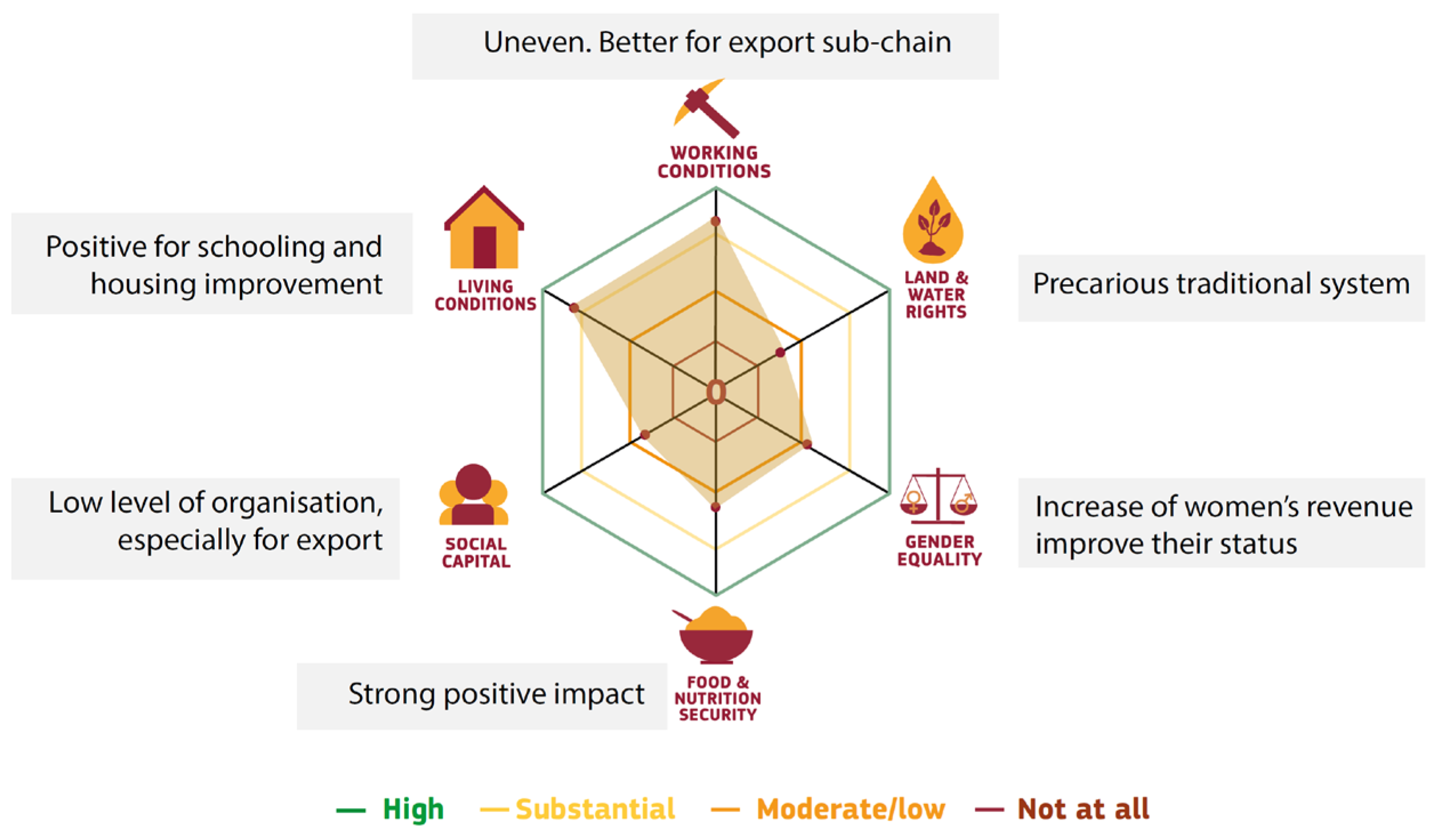

Social analysis (see

Figure 2) applies the social sustainability framework. The six indicators are as follows: (i) working conditions, (ii) land and water rights, (iii) gender equality, (iv) food and nutrition security (FNS), (v) social capital, and (vi) living conditions. This study included food safety (NAFDAC activities) as a distinct measure under social capital. Data collected will enabling impact assessment and highlights heterogeneity across aquaponics, RAS, and conventional producers and processors. Fabre et al. (2021) and Dhehibi et al. (2023) applied similar frameworks and mapping exercise that integrates social and gender indicators.

The environmental analysis focuses on resource efficiency, ecosystem impacts, and health risks, using True Cost Accounting (TCA), which monetization of externalities e.g., EUR/m3 for water stress (TCI, 2022). This approach allows comparison of externalized costs across conventional aquaculture, RAS, and aquaponics. Chen et al. (2020) Ravani et al. (2024) and Henriksson et al. (2015) provide benchmarks for environmental trade-offs in aquaculture systems.

Figure 3.

Environmental impact indicators using TCA. Source: TCI (2022: 23).

Figure 3.

Environmental impact indicators using TCA. Source: TCI (2022: 23).

3. Results

Functional Analysis

This comprehensive functional analysis provides overview for African Catfish value and supply chain in Nigeria. African Catfish is recognized for its resilience to harsh water conditions, strong disease resistance, and fast growth rates, making it a dominant species in Nigeria’s aquaculture sector, accounting for 60% of total production (Ohamesi et al. 2024). With Nigeria’s aquaculture production reaching approximately 316,727 metric tons in 2021, this suggests that African Catfish contributed around 190,036 metric tons to total production (Enwelu, 2023). The report presents a case for highlighting key actors from conventional and agri-innovative African Catfish production for the formal and informal markets. It outlines the core stages of the value chain, from input supply to value added, while emphasizing governance structures (see

Figure 7).

(i) Input supplier: Input suppliers play a crucial role in the growth and sustainability of Nigeria’s aquaculture industry. They provide a wide range of essential resources, including fingerlings and juveniles, fish feed, pond construction materials (e.g., concrete and tarpauline), aquaculture equipment, water quality management solutions, veterinary and health products, as well as extension services. Ensuring access to high-quality fingerlings, feed, and other critical inputs is key to enhancing fish farmers’ productivity and profitability.

(ii) Aquaculture producers: In Nigeria, most producers use conventional stagnant aquaculture methods, which entails the release of effluent into the environment every 2 days. Small-scale conventional aquaculture producers are those actors that produce less than 10 tons and account for 82% of total African Catfish producers (Olagunju 2024). These small–scale conventional producers are typically family-run fish farms of less than 3 plots (a plot is 60 m x 120m) in size, primarily serving informal markets and own consumption (see

Figure 4). Conversely, large-scale producers are commercial enterprises with extensive operations often much greater than 10 tons catering to both domestic and international markets (Howwe made it in Africa 2023). Small-scale producers are driven by market demands and profitability, adapting their practices to maximize profits. Aquaponics and RAS production (see

Figure 5) of African Catfish is relatively modest, with a contribution of less than 1% in Nigeria (Akinwole and Faturoti 2007, Benjamin et al. 2020, 2022). Akinwole and Faturoti (2007) reported 11 RAS facilities for African Catfish while Benjamin et al. (2020, 2022, 2025) published data on 2 aquaponics and 1 RAS facility for Lagos State between 2019 and 2025.

(iii) Processing: The processing of African Catfish, i.e., smoking, is carried out by mostly artisanal processors. Artisanal processors, mainly serving informal markets, use smoking kilns, manual labor and small batch production capacity (see

Figure 6). Women in Nigeria often dominate such artisanal processing with above 90% of the processors (Obasohan et al. 2012). Large-scale industrial processors that utilize automated systems and advanced machinery to smoke large quantities of African Catfish are low accounting for less than 5% of total production (Adeyeye 2016, HowwemadeitinAfrica 2023, Liverpool-Tasie et al. 2024).

(iv) Business and safety enabling environment (governance structure): The governance structure of the smoked African Catfish value chain is expensive and complex, as such individual negotiations determining factors such as quantity, quality, safety, and price. Government mechanisms i.e., regulating quantity and ensuring traceability through the National Agency for Food and Drug Administration and Control (NAFDAC) are in place but out of the reach of small-scale producers. Thus, African Catfish sold in informal markets often lack the NAFDAC certification with only a small number of export- and formal market oriented African Catfish producers registered with NAFDAC.

Figure 7.

Functional supply and value chain for conventional aquaculture, aquaponics, and RAS processed/dried African Catfish. Source: Own design.

Figure 7.

Functional supply and value chain for conventional aquaculture, aquaponics, and RAS processed/dried African Catfish. Source: Own design.

Profitability Analysis

In the value chain of African Catfish in Nigeria, profitability is a crucial metric to assess the financial sustainability of operations. This analysis applies a benefit-cost framework by setting operating expenses against revenue streams from production. The operating profit and net income of actors within the value chain are computed based on actual expense and revenue flows from a conventional aquaculture, RAS and aquaponics systems, as shown in

Table 2 and

Table 3.

Conventional aquaculture production incurs a number of expenses, ranging from intermediate consumption to labor costs.

Table 2 outlines the expenses typical incurred by African Catfish conventional farming operation on 150 m

2 area of land in 4 months i.e., one cycle in Lagos, Nigeria in 2025. The Intermediate consumption includes:

Fingerlings: The initial investment in fish fries EU

1 is 113 (₦180,000).

Fish feed: Fish feed amounts to EUR 1,125 (₦1,800,000).

Labour cost: Cost of labour was EUR 75 (₦120,000 i.e., ₦30,000 per month).

Fuel cost: Cost of running a generator is estimated at EUR 100 (N160,000).

This analysis considers worker wages as contribution to the overall value-added component. Overall, the total costs for the conventional aquaculture system in one cycle is EUR 1,413 (₦ 2,260,800). The revenue streams are based on African Catfish in production, with mean prices and production quantities. With an output of 2,400 kg of African Catfish at a mean price of EUR 2.2 (₦3,500) per kilogram, fish production generates EUR 5,250 (₦8,400,000) in revenue. Thus, the profit of operating the conventional aquaculture system in one cycle is EUR 3,837 (₦6,139,200), see

Table 2.

Aquaponics and RAS production area is typically < 50 m

2 but has similar expenses categorize expanded by spending on horticultural inputs.

Table 3 outlines the various expenses incurred by a typical home gardening operation in a cycle i.e., 4 months in Lagos, Nigeria. These cost includes:

Fingerlings: The initial investment in fish fries is EUR 17 (₦27,000).

Seedlings: Cost of seedlings of leafy green Amaranthus is EUR 1.4 (₦2,300).

Fish feed: Fish feed amounts to EUR 208 (₦332,800).

Nutrient additions and micronutrients: The cost of chaleted iron is EUR 3 (₦4,500) for 0.3kg.

Electricity: The electricity cost of EUR 17.5 (₦28,000).

Labour cost (part-time): A budget of EUR 125 (₦200,000 i.e., ₦50,000 per month).

Overall, the total costs for the aquaponics and RAS system in one cycle is EUR 371.9 (₦595,040). The revenue streams are based on African Catfish and leafy green (Amaranthus) production, with mean prices and production quantities are as follows:

Fish production: Output of 280 kg of African Catfish at a mean price of EUR 2.2 (₦3,500) per kg. Fish production generates EUR 616 (₦985,600) in revenue. Leafy green production: Amaranthus cultivated produced 5 kg of leafs which sells at EUR 2.2 (₦3,500) per kg resulting in EUR 11 (N17,600) revenue. Thus, the total revenues from both fish and plant production in one cycle is EUR 627 (₦1,003,200) while the profit of operating the aquaponics and RAS system is EUR 248 (₦396,640), see

Table 3.

Processors are capable of smoking up to 350 kilograms of African Catfish each day in their kiln. This processing capacity represents the upper limit of daily throughput for small-scale fish processors. This level of output can generate significant income, with potential revenue reaching approximately EUR 2,188, which is equivalent to ₦3,500,000. This estimate assumes optimal market conditions and consistent demand, however, this is currently not the case in Nigeria. Given high cost of energy - coal/gas/electricity, the price volatility as well as economic downturn, the real earning potential of processors needs to be further assessed. The data indicate that processors often cut costs by paying minimum wage, avoiding NAFDAC registration as well as non-use of packaging and storage facility.

Social Impact Analysis

A social impact assessment was conducted for conventional aquaculture, aquaponics and RAS as well as processors. This baseline social impact analysis is the first to be conducted for conventional aquaculture, aquaponics and RAS in Nigeria (see

Appendix A for results).

(i) Conventional aquaculture producers perceive their contribution to social impact as being most substantial in domains directly related to the working and living conditions of their employees and surrounding communities. They often emphasize their role in providing stable employment, improving livelihoods, and ensuring acceptable labor standards within their operations. However, they tend to view their influence as limited when it comes to broader structural issues such as land and water rights and gender equality, which they may perceive as outside the immediate scope of their operational responsibilities. This indicates a relatively narrow understanding of social responsibility, primarily focused on immediate and tangible aspects of their business practices.

(ii) Aquaponics and RAS producers perceive their contributions to social impact as both broad and substantial, spanning several key domains of sustainability. In particular, they frequently emphasize their role in fostering stable and sustainable livelihoods by generating employment opportunities, promoting local economic development, and implementing environmentally responsible practices. Aquaponics producers were observed to have a high monitoring and safety standards as well as NAFDAC registration. Moreover, they view themselves as active agents in the sustainable management of natural resources, especially with regard to conservation of land and water through closed-loop systems inherent to aquaponics and RAS technologies. Despite this generally high level of perceived social engagement, these producers report a more constrained sense of influence over wider societal challenges, most notably, gender equality. This issue is often perceived as external to the immediate operational environment of aquaponics and RAS enterprises and viewed as the responsibility of broader institutional frameworks or community-level initiatives. The relative deprioritization of gender-related concerns may also reflect a lack of targeted strategies or awareness within these production systems to address structural inequalities. Thus, their engagement remains uneven across the spectrum of social impact domains.

(iii) Processors perceive their contributions to social impact extending across economic development, employment generation, and environmental stewardship. They often emphasize their role in job creation and value addition along the supply chain. These activities are viewed as central to their operational mandate and as contributing directly to economic well-being. However, despite this strong engagement in multiple areas of sustainability, processors, much like aquaponics and recirculating aquaculture systems (RAS) producers, acknowledge a comparatively limited influence in advancing gender equality. Furthermore, processor have not placed enough emphasis on product quality and safety as well as maintaining traceability. This relates to low prioritization of registration with NAFDAC stemming from structural barriers, lack of regulatory enforcement or market-driven incentives.

Environmental Impact Analysis

Using the True Cost approach (TCI, 2022), the study compares the environmental performance of conventional aquaculture, aquaponics and RAS including the cultivation of leafy greens (Amaranthus) from the aquaponics system. The TCA focuses on two main categories: water stress and ecosystem health i.e., eutrophication with other indicators are excluded in this analysis. The functional unit (FU) is defined as 1 kg of marketable-quality Amaranthus and African Catfish fish, measured at the farm gate in 2024. The environmental impact analysis of conventional aquaculture system, aquaponics and RAS relies on data from the Aglobe Development Center FS4A prototype (

https://aglobedc.org/fs4africa/) as well as secondary literature. The results (see

Table 4) reveal that aquaponics has the lowest environmental impact in most categories compared to RAS while conventional aquaculture system has the highest water stress estimators. However, the water stress values in aquaponics can be higher in dry climate with substantial water scarcity. The true costs of each environmental impact indicator for this analysis are shown in

Table 4. The true cost for aquaponics, RAS as well as conventional aquaculture in terms of water stress and ecosystems were EUR 0.01, EUR 0.39 and EUR 2.25, respectively, for 1kg of African Catfish - and vegetable were applicable.

4. Discussion

This study explored the comparative performance of conventional aquaculture, aquaponics, and RAS in Nigeria, focusing on profitability, social impacts, and environmental sustainability using the VCA4D framework. The findings highlight a fundamental trade-off between conventional aquaculture, which generates higher short-term profits and aquaponics as well as RAS that display resource efficiency, high food safety potential, and long-term sustainability. This mirrors global debates on agri-food transitions, where established production models deliver immediate economic returns but impose hidden costs on ecosystems and public health (Henriksson et al., 2015; Greenfeld et al., 2022). The Nigerian context is unique because aquaculture is both a livelihood and a food security and safety strategy. African Catfish accounts for over 60% of aquaculture output (Ogunji & Wuertz, 2023), making any innovation in this sector critical to national nutrition and employment plan. Yet, conventional stagnant-water systems remain dominant, with weak food safety oversight and limited environmental safeguards. In contrast, aquaponics and RAS, although adopted by less than 1% of farmers (Akinwole & Faturoti, 2007; Benjamin et al., 2022), present climate-smart alternatives that are aligned with Nigeria’s need for water conservation, safe food, and urban resilience. However, aquaponics and RAS are not yet competitive on profitability terms, even though they offer important co-benefits. The economic analysis shows that conventional aquaculture generates higher net profits than aquaponics and RAS in Nigeria. For example, a single African Catfish production cycle of 2,400 kg in a conventional system yielded a profit of €3,837, compared with just €248 in aquaponics in the same period. This disparity is explained by the differences in scale, start-up capital, and input structures. Conventional producers operate larger ponds at relatively low capital intensity, while aquaponics and RAS rely on smaller installations with significant upfront costs in infrastructure, monitoring, and electricity, among others. Engle et al. (2021) found that profitability in RAS is highly sensitive to stocking densities, feed conversion ratios, and market premiums. In Nigeria, where electricity costs are high and reliable infrastructure is lacking, these constraints weigh heavily on the business case for aquaponics and RAS. Moreover, aquaponics’ dual production of African Catfish and vegetables only adds modest revenue under current Nigerian market conditions, where vegetables such as Amaranth have relatively low prices. Nonetheless, the long-term financial outlook may shift when externalities are considered. Conventional systems discharge effluents into water bodies and aquifers, generating environmental costs not borne by producers. The TCA results from this study show that conventional aquaculture imposes €2.25 per 1kg of costs of African Catfish produced, compared with €0.39 for RAS and €0.01 for aquaponics. The implication is that conventional systems may appear more profitable in the short run but undermine water resources and environmental conservation. Greenfeld et al. (2022) and Huijbregts et al. (2017) found that aquaponics and RAS have better lifecycle environmental metrics when energy use is decarbonized. These findings align with broader literature, emphasizing the importance of transitioning towards more circular, resource-efficient, and socially inclusive aquaculture (Ravani et al. 2024; Debroy et al. 2025, Benjamin et al. 2025). The social analysis reveals distinct differences in how these systems contribute to employment, gender dynamics, and food safety. Conventional aquaculture producers view their role as providing jobs and livelihoods but demonstrate limited concern for broader structural issues such as land and water rights or gender equality. A reason for this may be due to the fact that smallholder aquaculture in Nigeria is primarily survival-driven and rarely integrates social equity considerations (Grema et al., 2020). By contrast, aquaponics and RAS producers see themselves as pioneers of sustainability, emphasizing efficient use of land and water, stable employment, safety, and local economic development. However, aquaponics and RAS producers exhibit limited engagement with gender equity, reflecting structural barriers and the lack of targeted gender mainstreaming in aquaculture policies. While women dominate artisanal fish processing (up to 90% of the processors, see Obasohan et al., 2012), they are underrepresented in aquaponics and RAS production. Food safety also emerges as a critical challenge. The African Catfish producers and processors surveyed in this study lack NAFDAC registration. This is in Nigeria where smoked African Catfish is frequently sold without traceability. This exposes consumers to health risks and undermines market confidence. In contrast, aquaponics and RAS offer greater potential for traceability and certification (van der Doorn et al., 2022). This solidifies the broader social contribution of aquaponics and RAS to supply safe, nutritious food in Nigeria where demand for high-quality fresh produce is growing. The environmental analysis underscores aquaponics and RAS potential in conserving water and controlling pollution. Conventional aquaculture has the highest water stress and pollution values, while aquaponics demonstrates near-zero eutrophication and acidification. This aligns with Ravani et al. (2024) that vertical aquaponics reduced environmental footprints by 40% compared to open-field horticulture. Water resources are increasingly contested, especially in (peri-)urban areas in Nigeria where aquaculture competes with agriculture, domestic supply, and industrial uses. With climate change exacerbating droughts and variability, technologies that reduce water withdrawals are critical for long-term resilience. Aside from technical complexity, market uncertainty and institutional gaps, high up-front cost-related energy consumption remains a challenge for aquaponics and RAS in Nigeria, where fossil fuel generators still play a vital role. Jacal et al. (2022) highlight the economic and environmental burden of fossil fuel dependency in Nigeria’s agriculture sector. Aquaponics and RAS depend on pumps, aerators, and a filtration system. Thus, transitioning aquaponics and RAS to renewable energy sources, such as solar, and alternative aquaponics (see Benjamin et al. 2025) could significantly reduce operating costs. Outscaling aquaponics and RAS in Nigeria will require a more enabling institutional environment and supportive policies. Interventions such as subsidies for renewable energy, capacity-building programs for women entrepreneurs, credit and insurance mechanisms, simplified certification procedure, and reward for safe and sustainable production should be introduced. Such measures would not only strengthen aquaponics and RAS adoption among youths but also improve the overall supply of African Catfish and vegetables as well as proximity and traceability for consumers. Limitations of this study include the use of a rather small sample size, reliance on prototype data, and exclusion of some environmental indicators (e.g., greenhouse gas emissions). Future research should focus on longitudinal profitability studies across multiple production cycles as well as gender-disaggregated analysis of labor and decision-making in aquaponics and RAS. Furthermore, life cycle assessments incorporating renewable energy scenarios will be of high relevance as well as consumer willingness to pay for safe, certified aquaponics and RAS products.

5. Limitations of the Study

While this analysis breaks new ground in comparing conventional aquaculture, aquaponics, and RAS systems within the Nigerian context, it is important to acknowledge several limitations that may constrain the generalizability, precision, and interpretation of our findings. Reflection on these limitations also points the way to more robust future research.

(i) Temporal and spatial constraints: First, our empirical component is based on data from a limited number of production cycles and geographic locations. Because aquaponics and RAS systems are subject to seasonal variation (e.g., in temperature, rainfall, and electricity supply), our results may not fully capture year-round performance or extreme-weather responses. Studies of RAS in Africa frequently caution that viability is context-sensitive to local climate, energy reliability, and water availability. Moreover, scaling from pilot plot to commercial scale may introduce nonlinear shifts in cost structure and system dynamics that are not reflected in small-scale trials.

(ii) Scale and representativeness: Second, the production units examined (particularly for aquaponics and RAS) remain at pilot or micro-scale levels. These systems do not yet approximate full commercial scale, so the unit costs, input efficiencies, and risk exposures we observe may diverge from what would obtain under larger operations. In particular, economies of scale (or diseconomies) might significantly alter the performance margins when scaling. Because aquaponics and RAS are highly scale-sensitive in energy, water management, and monitoring demands, extrapolation to large-scale adoption should be done cautiously.

(iii) Input price and energy assumptions: Third, our cost and revenue analyses rely on prevailing input and energy prices, exchange rates, and local market conditions at the time of the study. These may change, indeed, energy costs and currency fluctuations in Nigeria are notoriously volatile. Our assumptions about electricity availability, fuel substitution (e.g., solar), and capital amortization may underestimate the risks associated with system downtime, maintenance failures, and grid unreliability. Prior analyses of RAS adoption in Africa emphasize that energy cost and reliability remain among the greatest hurdles to financial viability.

(iv) Technical complexity and monitoring limitations: Fourth, aquaponics and RAS systems demand high levels of technical expertise, precise monitoring, and rapid response to water quality fluctuations. In practice, unobserved events (e.g., disease outbreaks, sensor failure, biofilter breakdowns) may affect performance in ways not captured in our dataset. Although we monitored major parameters, the resolution of sensors or frequency of sampling may miss short-term shocks or cumulative stressors. Without continuous or automated monitoring (e.g., advanced control systems or AI-based models), even well-managed systems may suffer unobserved losses. Recent work points to opportunities in automated feeding and water quality control to reduce risk, but these remain immature in many settings.

(v) Limited scope of social, institutional, and behavioral variables: Fifth, our analysis of social and institutional dimensions, such as certification, market acceptance, governance, and gender dynamics, is necessarily constrained by the scope of available data. Qualitative surveys and key informant interviews revealed broad differences across systems, yet deeper ethnographic, participatory, or longitudinal methods would better uncover path dependencies, behavioral constraints, and institutional inertia. Additionally, we may understate the extent to which farmer risk aversion, credit constraints, or policy uncertainty influence adoption decisions in real-world settings.

(vi) Externalities and environmental boundary conditions: Sixth, although we integrate environmental externalities using the TCA approach, our estimation necessarily simplifies many complex ecological interactions. For example, nutrient runoff, local biodiversity effects, greenhouse gas emissions, and impacts on groundwater are difficult to quantify precisely, and our metrics may under- or overestimate real-world external costs in some cases. Moreover, our models assume stable background ecological conditions and may not capture feedback loops, threshold effects, or cumulative degradation in stressed ecosystems.

(vii) Generalizability beyond the local context: Lastly, while Nigeria provides a compelling country case to explore aquaponics and RAS in a lower-middle-income African setting, our findings may not translate directly to other countries with different regulatory regimes, energy regimes, climatic conditions, or market structures. For instance, in regions with cheaper renewable energy, more stable electricity grids, or more developed input markets, the cost-benefit calculus may shift. Cross-country comparative work is needed before broader policy recommendations can be confidently generalized.

6. Conclusion

This technical report has examined the structural and sustainability implications of conventional aquaculture, aquaponics, and RAS in Nigeria’s aquaculture sector through the value chain analysis for development (VCA4D). Applying an integrated framework that spans functional, economic, social, and environmental dimensions, the analyiy offers one of the first comprehensive evaluations of aquaponics and RAS as agri-innovations within the context of African Catfish production.

While conventional aquaculture continues to dominate both output and market presence due to its higher short-term profitability, the findings suggest that aquaponics and RAS may represent viable alternatives for fostering water-efficient, socially responsible, and food-safe aquaculture systems. Nevertheless, their broader adoption remains constrained by technical, financial, and institutional factors that demand targeted policy interventions.

The functional mapping highlights critical bottlenecks across all systems, particularly in governance, certification, and tracebility mechanisms. Smallholder conventional producers and processors, who constitute the bulk of the sector, typically operate outside formal regulatory oversight, which compromises product traceability and food safety. In contrast, aquaponics and RAS actors demonstrate greater potential for integration into formal markets due to their higher levels of monitoring, traceability, and environmental compliance. However, their limited scale and higher capital intensity inhibit their competitiveness. Addressing these structural asymmetries will require inclusive upgrading strategies that enhance coordination, enable certification, and bridge the gap between informal and formal markets.

From a profitability perspective, conventional systems clearly outperform aquaponics and RAS under prevailing market conditions. The study’s operating account analysis shows that conventional producers earn higher profits per cycle, driven by larger volumes and lower capital costs. Conversely, aquaponics and RAS incur higher unit costs due to (so far) smaller production scales and intensive infrastructure needs, particularly for (renewable) electricity and monitoring equipment. These findings echo earlier studies emphasizing the scale sensitivity and energy dependence of RAS systems. While aquaponics allows for diversified outputs (i.e., fish, fruits and vegetables), the marginal returns from horticultural production are currently insufficient to offset the higher overall input costs. Profitability may improve over time, but this will depend on reducing input costs, especially energy, and improving access to credit, markets, and premium pricing for certified, safe food, as well as the public support system.

The social analysis suggests a more complex dynamic. While all production systems generate employment and contribute to local livelihoods, aquaponics and RAS exhibit comparatively stronger commitments to working conditions, food and nutrition security, and environmental stewardship. Notably, aquaponics and RAS actors report higher levels of NAFDAC registration and greater awareness of food safety standards. However, engagement with structural social issues, particularly gender equity, remains uneven across all systems. Although women dominate artisanal fish processing, they are underrepresented in aquaponics and RAS production, reflecting both institutional neglect and the gendered nature of capital and knowledge access, which is generally in favor of men. Promoting gender-responsive aquaculture innovations will require deliberate strategies to mainstream gender within extension services, training programs, and policy frameworks.

Environmentally, aquaponics and RAS systems demonstrate clear advantages. The TCA results show that aquaponics, in particular, incurs negligible water stress and nutrient pollution externalities, making it an environmentally superior option. In contrast, conventional aquaculture systems impose significant environmental costs due to frequent effluent discharge and inefficient water use. Although RAS also performs better than conventional systems, its higher energy footprint somewhat diminishes its environmental advantage, especially when powered by fossil fuels. This underscores the importance of coupling RAS and aquaponics systems with renewable energy solutions, which may not only improve environmental outcomes but also enhance profitability by reducing recurrent energy expenditures.

In sum, the findings point to a strategic dilemma. While conventional aquaculture remains economically dominant, it does so at the expense of environmental integrity and food safety. Aquaponics and RAS offer a more sustainable and socially inclusive model, but are currently hindered by structural and economic constraints. Scaling these innovations will likely require a suite of coordinated interventions. These may include subsidies for renewable energy integration, investment in locally adapted technologies, gender-sensitive capacity building, and streamlined regulatory procedures to lower certification barriers. The broader policy environment must also evolve to support circular food systems that balance profitability with ecological and social imperatives.

Ultimately, this analysis affirms that aquaponics and RAS should not be viewed as replacements for conventional systems, but as complementary innovations within a diversified aquaculture landscape. Their potential lies in supplying high-quality, traceable, and resource-efficient food, particularly in peri-urban settings where land and water pressures are acute. However, realizing this potential will depend on multisectoral action involving policymakers, researchers, private investors, and producer organizations. Future research should extend this baseline analysis by incorporating lifecycle assessments, renewable energy scenarios, and consumer demand studies to provide a fuller picture of the pathways toward sustainable aquaculture in Nigeria and beyond.

Funding

This research was funded by the European Union under Horizon Europe, grant agreement No. 101136916, project name “Food Safety for Africa” (FS4A). The views and opinions expressed are, however, those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union. Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the management and staff of Aglobe Development Center (ADC) -

www.aglobedc.org Lagos, Nigeria.

Appendix A

Survey Response for Social Impact

Conventional Aquaculture Survey Response

| Question |

Response |

| Working conditions |

| Are working conditions throughout the African Catfish (Clarias gariepinus) socially acceptable and sustainable? |

1. not at all ☒

2. not at all ☒

3. not at all ☒ |

1. moderately/low ☒

2. moderately/low ☒

3. moderately/low ☒ |

1. Substantial/ high ☒

2. Substantial/ high ☒

3. Substantial/ high ☒ |

| Do value chain (VC) operations in African Catfish (Clarias gariepinus) contribute to improving working conditions? |

1. not at all ☒

2. not at all ☒

3. not at all ☐ |

1. moderately/low ☒

2. moderately/low ☐

3. moderately/low ☐ |

1. Substantial/ high ☒

2. Substantial/ high ☒

3. Substantial/ high ☒ |

| Land and water rights |

| Are the land rights implemented throughout the African Catfish (Clarias gariepinus) socially acceptable and sustainable? |

1. not at all ☒

2. not at all ☒

3. not at all ☒ |

1. moderately/low ☐

2. moderately/low ☐

3. moderately/low ☐ |

1. Substantial/ high ☐

2. Substantial/ high ☐

3. Substantial/ high ☐ |

| Are the water rights implemented throughout the African Catfish (Clarias gariepinus) socially acceptable and sustainable? |

1. not at all ☒

2. not at all ☐

3. not at all ☒ |

1. moderately/low ☐

2. moderately/low ☒

3. moderately/low ☐ |

1. Substantial/ high ☐

2. Substantial/ high ☐

3. Substantial/ high ☐ |

| Gender equality |

| Based on your perception, what percentage of the farm labor of African Catfish (Clarias gariepinus) is constituted by women? |

1. 10%

2. 40%

3. 50%

|

| Based on your perception, what percentage of labor in processing of African Catfish (Clarias gariepinus) is constituted by women? |

1. 30%

2. 30%

3. 30%

|

| Based on your perception, what percentage of labor in marketing (retailing) of African Catfish (Clarias gariepinus) is constituted by women? |

1. 70%

2. 80%

3. 70%

|

| Throughout the African Catfish (Clarias gariepinus) do actors foster and put into practice gender equality? |

1. not at all ☒

2. not at all ☒

3. not at all ☒ |

1. moderately/low ☐

2. moderately/low ☐

3. moderately/low ☐ |

1. Substantial/ high ☐

2. Substantial/ high ☐

3. Substantial/ high ☐ |

| Food and nutrition security |

| Do VC activities of African Catfish (Clarias gariepinus), contribute to upgrading and securing the food and nutrition conditions? |

1. not at all ☐

2. not at all ☒

3. not at all ☒ |

1. moderately/low ☒

2. moderately/low ☐

3. moderately/low ☐ |

1. Substantial/ high ☐

2. Substantial/ high ☐

3. Substantial/ high ☐ |

| Social capital |

| Is social capital enhanced by VC operations and equitably distributed throughout the VC of African Catfish (Clarias gariepinus)? |

1. not at all ☒

2. not at all ☐

3. not at all ☐ |

1. moderately/low ☐

2. moderately/low ☒

3. moderately/low ☐ |

1. Substantial/ high ☐

2. Substantial/ high ☐

3. Substantial/ high ☒ |

| Living conditions |

| Are the general living conditions (i.e., better access to health services, education, improved housing) of the laborers in the production of African Catfish (Clarias gariepinus) and along the value chain improving? |

1. not at all ☐

2. not at all ☐

3. not at all ☐ |

1. moderately/low ☒

2. moderately/low ☒

3. moderately/low ☐ |

1. Substantial/ high ☐

2. Substantial/ high ☐

3. Substantial/ high ☒ |

| Do the VC activities of African Catfish (Clarias gariepinus) contribute to improving the living conditions of the actors through acceptable facilities and services? |

1. not at all ☐

2. not at all ☒

3. not at all ☐ |

1. moderately/low ☒

2. moderately/low ☐

3. moderately/low ☐ |

1. Substantial/ high ☐

2. Substantial/ high ☐

3. Substantial/ high ☒ |

Aquaponics and RAS production

| Question |

Response |

| Working conditions |

| Are working conditions throughout the African Catfish (Clarias gariepinus) socially acceptable and sustainable? |

1. not at all ☐

2. not at all ☐

|

1. moderately/low ☐

2. moderately/low ☐

|

1. Substantial/ high ☒

2. Substantial/ high ☒

|

| Do value chain (VC) operations in African Catfish (Clarias gariepinus) contribute to improving working conditions? |

1. not at all ☐

2. not at all ☐

|

1. moderately/low ☐

2. moderately/low ☐

|

1. Substantial/ high ☒

2. Substantial/ high ☒

|

| Land and water rights |

| Are the land rights implemented throughout the African Catfish (Clarias gariepinus) socially acceptable and sustainable? |

1. not at all ☐

2. not at all ☐

|

1. moderately/low ☐

2. moderately/low ☐

|

1. Substantial/ high ☒

2. Substantial/ high ☒

|

| Are the water rights implemented throughout the African Catfish (Clarias gariepinus) socially acceptable and sustainable? |

1. not at all ☐

2. not at all ☐

|

1. moderately/low ☐

2. moderately/low ☐

|

1. Substantial/ high ☒

2. Substantial/ high ☒ |

| Gender equality |

| Based on your perception, what percentage of the farm labor of African Catfish (Clarias gariepinus) is constituted by women? |

1. 40%

2. 60%

|

| Based on your perception, what percentage of labor in processing of African Catfish (Clarias gariepinus) is constituted by women? |

1. 50%

3. 60%

|

| Based on your perception, what percentage of labor in marketing (retailing) of African Catfish (Clarias gariepinus) is constituted by women? |

1. 80%

2. 60%

|

| Throughout the African Catfish (Clarias gariepinus) do actors foster and put into practice gender equality? |

1. not at all ☐

2. not at all ☐

|

1. moderately/low ☐

2. moderately/low ☐

|

1. Substantial/ high ☒

2. Substantial/ high ☒ |

| Food and nutrition security |

| Do VC activities of African Catfish (Clarias gariepinus), contribute to upgrading and securing the food and nutrition conditions? |

1. not at all ☐

2. not at all ☐

|

1. moderately/low ☐

2. moderately/low ☐

|

1. Substantial/ high ☒

2. Substantial/ high ☒

|

| Social capital |

| Is social capital enhanced by VC operations and equitably distributed throughout the VC of African Catfish (Clarias gariepinus)? |

1. not at all ☐

2. not at all ☐

|

1. moderately/low ☐

2. moderately/low ☐

|

1. Substantial/ high ☒

2. Substantial/ high ☒

|

| Living conditions |

| Are the general living conditions (i.e., better access to health services, education, improved housing) of the laborers in the production of African Catfish (Clarias gariepinus) and along the value chain improving? |

1. not at all ☐

2. not at all ☐

|

1. moderately/low ☐

2. moderately/low ☐

|

1. Substantial/ high ☒

2. Substantial/ high ☒

|

| Do the VC activities of African Catfish (Clarias gariepinus) contribute to improving the living conditions of the actors through acceptable facilities and services? |

1. not at all ☐

2. not at all ☐

|

1. moderately/low ☐

2. moderately/low ☐

|

1. Substantial/ high ☒

2. Substantial/ high ☒

|

Processors

| Question |

Response |

| Working conditions |

| Are working conditions throughout the African Catfish (Clarias gariepinus) socially acceptable and sustainable? |

1. not at all ☐

2. not at all ☐

3. not at all ☐

|

1. moderately/low ☐

2. moderately/low ☐

3. moderately/low ☐

|

1. Substantial/ high ☒

2. Substantial/ high ☒

3. Substantial/ high ☒

|

| Do value chain (VC) operations in African Catfish (Clarias gariepinus) contribute to improving working conditions? |

1. not at all ☐

2. not at all ☐

3. not at all ☐ |

1. moderately/low ☐

2. moderately/low ☐

3. moderately/low ☐ |

1. Substantial/ high ☒

2. Substantial/ high ☒

3. Substantial/ high ☒ |

| Land and water rights |

| Are the land rights implemented throughout the African Catfish (Clarias gariepinus) socially acceptable and sustainable? |

1. not at all ☐

2. not at all ☐

3. not at all ☐ |

1. moderately/low ☐

2. moderately/low ☐

3. moderately/low ☒ |

1. Substantial/ high ☒

2. Substantial/ high ☒

3. Substantial/ high ☐ |

| Are the water rights implemented throughout the African Catfish (Clarias gariepinus) socially acceptable and sustainable? |

1. not at all ☐

2. not at all ☐

3. not at all ☐ |

1. moderately/low ☐

2. moderately/low ☐

3. moderately/low ☒ |

1. Substantial/ high ☒

2. Substantial/ high ☒

3. Substantial/ high ☐ |

| Gender equality |

| Based on your perception, what percentage of the farm labor of African Catfish (Clarias gariepinus) is constituted by women? |

1. 40%

2. 40%

3. 50%

|

| Based on your perception, what percentage of labor in processing of African Catfish (Clarias gariepinus) is constituted by women? |

1. 80%

2. 90%

3. 30%

|

| Based on your perception, what percentage of labor in marketing (retailing) of African Catfish (Clarias gariepinus) is constituted by women? |

1. 85%

2. 60%

3. 70%

|

| Throughout the African Catfish (Clarias gariepinus) do actors foster and put into practice gender equality? |

1. not at all ☐

2. not at all ☐

3. not at all ☐ |

1. moderately/low ☐

2. moderately/low ☒

3. moderately/low ☒ |

1. Substantial/ high ☒

2. Substantial/ high ☐

3. Substantial/ high ☐ |

| Food and nutrition security |

| Do VC activities of African Catfish (Clarias gariepinus), contribute to upgrading and securing the food and nutrition conditions? |

1. not at all ☐

2. not at all ☐

3. not at all ☐ |

1. moderately/low ☐

2. moderately/low ☐

3. moderately/low ☒ |

1. Substantial/ high ☒

2. Substantial/ high ☒

3. Substantial/ high ☐ |

| Social capital |

| Is social capital enhanced by VC operations and equitably distributed throughout the VC of African Catfish (Clarias gariepinus)? |

1. not at all ☐

2. not at all ☐

3. not at all ☐ |

1. moderately/low ☒

2. moderately/low ☐

3. moderately/low ☐ |

1. Substantial/ high ☐

2. Substantial/ high ☒

3. Substantial/ high ☒ |

| Do VC actors have a National Agency for Food and Drug Administration and Control Identification number?. |

1. Not applicable ☐

2. Not applicable ☐

3. Not applicable ☐ |

1. Yes ☐

2. Yes ☐

3. Yes ☐ |

1. No ☒

2. No ☒

3. No ☒ |

| Living conditions |

| Are the general living conditions (i.e., better access to health services, education, improved housing) of the laborers in the production of African Catfish (Clarias gariepinus) and along the value chain improving? |

1. not at all ☐

2. not at all ☐

3. not at all ☐ |

1. moderately/low ☐

2. moderately/low ☒

3. moderately/low ☐ |

1. Substantial/ high ☒

2. Substantial/ high ☐

3. Substantial/ high ☒ |

| Do the VC activities of African Catfish (Clarias gariepinus) contribute to improving the living conditions of the actors through acceptable facilities and services? |

1. not at all ☐

2. not at all ☐

3. not at all ☐ |

1. moderately/low ☐

2. moderately/low ☒

3. moderately/low ☐ |

1. Substantial/ high ☒

2. Substantial/ high ☐

3. Substantial/ high ☒ |

References

- Adeyemi, O., Amototo, I., & Salaudeen, F. (2024). Design and construction of an aquaponics system: A sustainable approach. ABUAD Journal of Engineering Research and Development. Retrieved from https://mail.journals.abuad.edu.ng/index.php/ajerd/article/view/929. [CrossRef]

- Adeyeye, S. A. O. (2016). Traditional fish processing in Nigeria: a critical review. Nutrition & Food Science, 46(3), 321-335. [CrossRef]

- Akinwole, A. O., & Faturoti, E. O. (2007). Biological performance of African Catfish (Clarias gariepinus) cultured in recirculating system in Ibadan, Nigeria. Aquaculture Engineering, 36(1), 18-23. [CrossRef]

- Astuti, R. S. D., & Hadiyanto, H. (2018). Estimating environmental impact potential of small-scale fish processing using life cycle assessment. Journal of Ecological Engineering, 19(6). [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, E. O., Buchenrieder, G. R., & Sauer, J. (2020). Economics of small-scale aquaponics system in West Africa: A SANFU case study. Aquaculture economics & management, 25(1), 53-69. [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, E. O., Ola, O., & Buchenrieder, G. R. (2022). Feasibility Study of a Small-Scale Recirculating Aquaculture System for Sustainable (Peri-)Urban Farming in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Nigerian Perspective. Land, 11(11), 2063. [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, E. O., Reuter, M., & Buchenrieder, G. (2025). Simplified Agri-Innovation for Sustainable Food Systems in Africa. Preprints. [CrossRef]

- Chen, P., Zhu, G., Kim, H.-J., Brown, P. B., & Huang, J.-Y. (2020). Comparative life cycle assessment of aquaponics and hydroponics in the Midwestern United States. Journal of Cleaner Production, 275, 122888. [CrossRef]

- Debroy, P., Majumder, P., Majumdar, P., Das, A., & Seban, L. (2025). Analysis of opportunities and challenges of smart aquaponic system: A summary of research trends and future research avenues. Sustainable Environment Research, 35(18). [CrossRef]

- Desclée, D., Kinha, C., Payen, S., Sohinto, D., & Govindin, J. C. (2019). Analyse de la chaîne de l’ananas au Bénin. Value Chain Analysis for Development Project Report. European Commission.

- Dhehibi, B., Souissi, A., Frija, A., Ouerghemmi, H., Alary, V., Idoudi, Z., Rüdiger, U., Rekik, M., Dhraief, M. Z., Zlaoui, M. O., Mejri, R., & Ouji, M. (2023). Value chain analysis and actor mapping: Case of Tunisia. CGIAR Agroecology Initiative Report.

- Engle, C. R., Kumar, G., & van Senten, J. (2021). Resource-use efficiency in US aquaculture: Farm-level comparisons across species and systems. Aquaculture Environment Interactions, 13, 259–275. [CrossRef]

- FAO. (2022). The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2022: Towards Blue Transformation. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization.

- Fabre, P., Dabat, M. H., & Orlandoni, O. (2021). Methodological brief for agri-based value chain analysis: Frame and tools. European Commission.

- Greenfeld, A., Becker, N., Bornman, J. F., Spatari, S., & Angel, D. L. (2022). Is aquaponics good for the environment? Evaluation of environmental impact through life cycle assessment studies on aquaponics systems. Aquaculture International, 30(1), 305–322. [CrossRef]

- Grema, H. A., Kwaga, J. K. P., Bello, M., & Umaru, O. H. (2020). Understanding fish production and marketing systems in North-western Nigeria and identification of potential food safety risks using value chain framework. Preventive Veterinary Medicine, 181, 105038. [CrossRef]

- Henriksson, P. J. G., Belton, B., Murshed-E-Jahan, K., Rico, A., & Little, D. C. (2015). Uncovering the true environmental performance of aquaculture systems. Journal of Cleaner Production, 102, 144–152. [CrossRef]

- HowwemadeitinAfrica 2023. Available online at https://www.howwemadeitinafrica.com/nigeria-four-businesses-seizing-opportunities-in-the-fish-industry/156456/.

- Huijbregts, M. A. J., Steinmann, Z. J. N., Elshout, P. M. F., Stam, G., Verones, F., Vieira, M., Zijp, M., Hollander, A., & van Zelm, R. (2017). ReCiPe2016: A harmonized life cycle impact assessment method at midpoint and endpoint level. International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment, 22, 138–147. [CrossRef]

- Jacal, S., Straubinger, F. B., Benjamin, E. O., & Buchenrieder, G. (2022). Economic costs and environmental impacts of fossil fuel dependency in sub-Saharan Africa: A Nigerian dilemma. Energy for Sustainable Development, 70, 45-53. [CrossRef]

- Kasim, L. I., Yusuf, B. A., Maradun, H. F., & Abubakar, M. B. (2023). Potential of aquaponics as a fish culture system in Nigeria for sustainable food security and national development. Bichi Journal of Vocational Education, 3(1), 72–79.

- Liverpool-Tasie, L. S. O., Wineman, A., Amadi, M. U., Gona, A., Emenekwe, C. C., Fang, M., ... & Belton, B. (2024). Rapid transformation in aquatic food value chains in three Nigerian states. Frontiers in Aquaculture, 3, 1302100. [CrossRef]

- Mekonnen, M. M., & Hoekstra, A. Y. (2012). A global assessment of the water footprint of farm animal products. Ecosystems, 15(3), 401-415. [CrossRef]

- Nie, Y., & Hallerman, E. (2021). Optimization of design and operation of recirculating aquaculture systems (RAS): Water reuse rates of 90–99%. Journal of Cleaner Production. [CrossRef]

- Obasohan, E., Obasohan, E., Edward, E., & Oronsaye, J. A. O. (2012). A survey on the processing and distribution of smoked catfishes (Heterobranchus and Clarias Spp.) In Ekpoma, Edo State, Nigeria. Research Journal of Recent Sciences.

- Ogunji, J., & Wuertz, S. (2023). Aquaculture development in Nigeria: The second biggest aquaculture producer in Africa. Water, 15(24), 4224. [CrossRef]

- Our World in Data. (2025) (n.d.). Eutrophying emissions per kg PO4 eq [Data set]. Retrieved [Access 04.04.2025], from Our World in Data website: https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/eutrophying-emissions-per-kg-poore.

- Ravani, M., Chatzigeorgiou, I., Monokrousos, N., Giantsis, I. A., & Ntinas, G. K. (2024). Life cycle assessment of a high-tech vertical decoupled aquaponic system for sustainable greenhouse production. Frontiers in Sustainability, 5, 1422200. [CrossRef]

- True Cost Initiative. (2022). TCA Handbook – Practical True Cost Accounting guidelines for the food and farming sector. Hamburg: True Cost Initiative.

- Umar, M. A., Abubakar, A. B., Babayo, A. J., & Aliyu, J. (2025). Aquaponics aquaculture system as the most efficient, sustainable and green aquaculture system: A review. Bima Journal of Science and Technology.

- van der Doorn, L., Heer, M., Huertas Garcia, M., & Soriano, P. (2022). Urban aquaponics in the European Union: Sustainable development policy brief. Wageningen University2.

- Waller, U. (2024). A Critical Assessment of the Process and Logic Behind Fish Production in Marine Recirculating Aquaculture Systems. Fishes, 9(11), 431. [CrossRef]

- Wilfart, A., Prudhomme, J., Blancheton, J. P., & Aubin, J. (2013). LCA and emergy accounting of aquaculture systems: Towards ecological intensification. Journal of environmental management, 121, 96-109. [CrossRef]

- WorldFish Center. (2016). Sustainable aquaculture guidelines for Africa. Penang, Malaysia: WorldFish.

| 1 |

The EUR to Naira exchange rate is EUR 1 = ₦1,600. |

| 2 |

This study estimates that the average water footprint of farmed fish is about 1.5–4.0 m3/kg (green + blue water). While it doesn't directly express water stress, it provides the volumetric use, which can be multiplied by a water stress index (typically 0.3–0.5 globally) for an estimated 0.45–2.0 m3-equivalent per kg of fish produced. |

| 3 |

The acidification impact of Recirculating Aquaculture Systems (RAS) in terms of SO2 equivalent (SO2eq) emissions per kilogram of fish can vary between 0.1 and 0.2 kg SO2eq per kg of fish produced based on several factors. In this analysis, we took the average value of 0.15 (Waller, 2024). |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).