1. Introduction

Since prostate adenocarcinoma is the most common cancer in men and the second leading cause of cancer-related mortality in developed nations, early detection is essential for effective treatment. Despite the progress that has been made in uro-oncology, the insufficient precision of available diagnostic tools remains an obstacle to the treatment of prostate cancer. Prostate adenocarcinoma is mainly diagnosed based on the serum PSA biomarker, but an increase in this antigen level can also be caused by benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) or inflammatory processes, which weakens its specificity. In addition, PSA is not a good predictor of disease outcome, as its levels do not correlate with the aggressiveness of prostate cancer. It should also be taken into account that in the case of multifocal prostate cancer, biopsy results are often misinterpreted due to improper sampling [

1]. The greatest challenge in clinical practice is accurately differentiating prostate adenocarcinoma from BPH, due to the differences in treatment approaches and management strategies. Studies comparing adenocarcinoma to BPH have significant translational value because they enable the translation of

fundamental research results into practical diagnostic and therapeutic methods that can be directly applied in medicine. Furthermore, the use of patients with BPH as controls in prostate cancer studies is valuable, as it reflects the everyday challenges faced by urologists.

A promising direction of development in cancer diagnostics are short single-stranded RNA segments called miRNAs. According to the literature, some miRNAs are involved in the development of prostate cancer. Due to their ability to silence selected genes, miRNAs can contribute to tumour growth, angiogenesis, and metastases. As the expression of miRNAs is observed already in the early phase of the disease, their examination, especially in blood, has promising diagnostic potential in detecting cancer. MiRNAs can have oncogenic or tumor suppressor effects, or both, depending on the type of cancer and the method of expression [

2].

Studies have shown that the Wnt signaling pathway is involved in the development of prostate cancer. Autocrine signaling in cancer cells and paracrine signaling from the tumor microenvironment have been shown to be involved in tumor development and metastasis. The canonical Wnt pathway regulates the survival of prostate adenocarcinoma stem cells, while the non-canonical Wnt pathway is involved in imparting invasive characteristics to cancer cells, which may be important in the early stages of carcinogenesis. Blocking individual elements of the Wnt pathway, particularly those that inhibit β-catenin interactions with key transcription factors, may prove to be an important therapeutic strategy for patients with prostate cancer [

3].

Binding of a specific Wnt protein to the FZD receptor activates a canonical β-catenin-dependent or β-catenin-independent (non-canonical) signaling pathway. The classical pathway regulates the function of T-cell transcription factor (TCF) affecting processes such as embryogenesis, differentiation, survival and proliferation of cells. Dysfunction of the Wnt pathway has been observed in various types of cancers [

3]. Previous studies have demonstrated that Fzd8 plays a promotive role in tumor cell proliferation and metastasis in renal and thyroid cancers, as well as contributes to bone metastasis in prostate cancer [

4]. Recently, miR-375-3p has been shown to inhibit colorectal cancer metastasis by regulating Fzd8 levels. Fzd8 expression was inversely correlated with overall survival in colorectal cancer patients, and Fzd8 was found to be an independent prognostic factor in this type of cancer. This information suggests that miR-375-3p and its molecular target Fzd8 may be potential therapeutic options in aggressive cancers [

5].

Cyclin D1 is a key regulator of cell cycle progression and has been implicated in the initiation and progression of various cancers. Its increased expression is commonly associated with poor prognosis and therapeutic resistance, including in prostate adenocarcinoma. Beyond its canonical role in cell cycle control, cyclin D1 has been shown to influence the biogenesis and function of specific microRNAs, thereby modulating oncogenic signaling pathways at the post-transcriptional level. Given that miR-375-3p targets Fzd8, a receptor involved in Wnt signaling and cancer progression, the interaction between cyclin D1 and miRNA suggests a possible regulatory axis. This axis may contribute to tumor aggressiveness and therapy resistance. Therefore, further studies focusing on selected miRNAs and their interaction with components of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling are essential to better understand their role in prostate adenocarcinoma progression [

6].

The discovery of small, non-coding RNA molecules called microRNAs has significantly expanded our knowledge of cancer pathogenesis. It turned out that this group of approximately 22 nucleotide molecules has a significant impact on many fundamental cellular and physiological processes. Their action involves post-translational silencing of genes, including those responsible for cell differentiation, proliferation and apoptosis. Depending on the function performed by specific mRNAs, microRNA molecules can act as oncogenes controlling the course of the cell cycle, e.g. by regulating CDK inhibitors or tumor suppressors, causing the cycle to stop. Abnormalities in the expression of microRNA genes cause disruption of cell homeostasis and can lead to the development of cancer. Recent studies have shown a common change in the expression of these molecules in cancer cells, which has become the basis for searching for methods to modulate activity and use them in therapy. The use of microRNAs as non-invasive biomarkers in predicting the development of cancer is also important [

2,

7,

8].

Mir-106a-5p turned out to be the main regulator of potential biomarkers of aggressiveness and prognosis of some cancers, e.g. breast cancer or osteosarcoma [

7,

9]. Literature data indicate that miR-106a-5p expression is significantly associated with the progression of prostate adenocarcinoma and correlates with an increased risk of malignancy [

8]. MiR-106a-5p may act as an oncomiRNA, modulating the expression Wnt pathway- related proteins, such as β-catenin, Fzd8 and Wnt5a, as well as influencing cell cycle regulation, including cyclin D1. This activity may promote the development of prostate adenocarcinoma, mainly by stimulating cell proliferation and disrupting the cell cycle.

While miR-106a-5p appears to promote prostate adenocarcinoma progression through increased cell proliferation, recent studies highlight the contrasting role of miR-375, which acts as a suppressor and inhibitor of proliferation. MiR-375 has been shown to inhibit metastasis and proliferation in bladder cancer cells, as demonstrated in the T24 xenograft mouse model. MiR- 375-3p blocked the Wnt signaling cascade and downstream molecules such as c-Myc and cyclin D1 by inhibiting the expression of Fzd8. This resulted in increased caspase expression and cell apoptosis in the T24 cell line. Considering that miR-375-3p acts as a suppressor in bladder cancer, we aimed to assess whether this microRNA plays a similar role in prostate adenocarcinoma [

4].

Recent scientific studies have demonstrated that specific miRNAs regulate cancer cell proliferation and migration by modulating the Wnt/β-catenin pathway. A significant relationship was established between the expression of proteins involved in the Wnt/β-catenin pathway and tumor differentiation, the presence of metastasis and patient survival.

To date, there have been no comprehensive studies published on the comparative evaluation of miR-106a-5p and miR-375-3p expression and their correlation with Wnt/β-catenin pathway proteins in prostate adenocarcinoma and benign prostatic hyperplasia. Therefore, the aim of this study was to initially evaluate the differences in the expression of miR-106a-5p and miR-375-3p and the proteins β-catenin, Fzd8, Wnt5a, and cyclin D1 in prostate adenocarcinoma compared with benign prostatic hyperplasia. We were also interested in how changes in the expression of miRNAs and proteins related to the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway and cell adhesion contribute to the pathogenesis of these two pathological conditions and their potential use in clinical diagnostics.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Sample Collection

The research was carried out using postoperative specimens obtained from 30 individuals diagnosed with prostatic adenocarcinoma and 30 patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia, all treated at the Urology Department of the Medical University of Bialystok. Ethical clearance for the study was granted by the Bioethics Committee of the Medical University of Bialystok (APK.002.22.2024; approval date: January 18, 2024), written informed consent was obtained from each person to participate in the study. Patients were assigned to the appropriate experimental groups based on variables such as age, serum PSA level and histopathological result with Gleason score. The research material consisted of fragments of prostatic adenocarcinoma and benign prostatic hyperplasia collected during adenomectomy or transurethral resection of the prostate. Tissue samples were promptly preserved either in 10% buffered formalin followed by routine paraffin embedding, or in RNA-later solution (AM7024, Thermo Fisher) and subsequently stored at –80 °C. Paraffin-embedded blocks were sectioned at a thickness of 4 μm, stained with hematoxylin and eosin for general histopathological assessment, and further processed for immunohistochemical detection of β-catenin, Fzd8, Wnt5a, and cyclin D1. Material stored in RNA-later were analyzed by real-time PCR to determine the transcriptional levels of the genes encoding β-catenin, Fzd8, Wnt5a, and cyclin D1.

2.2. Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemical analysis was carried out using the EnVision technique, following the procedure previously outlined by Kasacka et al. [

10]. The immunohistochemistry assays were performed with the REAL™ EnVision™ Detection System, Peroxidase/DAB, Rabbit/Mouse (K5007; Dako Cytomation, Glostrup, Denmark). Immunostaining was conducted according to the following protocol: paraffin-embedded sections were deparaffinized and hydrated in pure alcohols.

For antigen retrieval, the sections were subjected to pretreatment in a pressure chamber heated for 1min at 21 psi (one pound force per square inch (1 psi) equates to 6.895 kPa, the conversion factor has been provided by the NPL (United Kingdom National Physical Laboratory) at 125 °C with the use of Target Retrieval Solution Citrate, pH 6.0 (S2369; Dako Cytomation, Glostrup, Denmark) for β-catenin, Fzd8, Wnt5a, and cyclin D1. Following cooling to ambient temperature, the tissue sections were treated with a Peroxidase Blocking Reagent (S 2023 Agilent Technologies Denmark ApS Produktionsvej 42, 2600 Glostrup, Denmark) for 10 min to block endogenous peroxidase activity. Subsequently sections were incubated with primary antibody for β-catenin (Mouse monoclonal to β-catenin, ab32572, ABCAM Discovery Drive, Cambridge, Biomedical Campus, Cambridge, CB2 0AX UK), Fzd8 (Rabbit monoclonal to Fzd8, ab155093, ABCAM Discovery Drive, Cambridge, Biomedical Campus, Cambridge, CB2 0AX UK), Wnt5a (Rabbit polyclonal to Wnt5a, ab235966, ABCAM Discovery Drive, Cambridge, Biomedical Campus, Cambridge, CB2 0AX UK) and cyclin D1 (Mouse monoclonal to cyclin D1, ab273608, ABCAM Discovery Drive, Cambridge, Biomedical Campus, Cambridge, CB2 0AX UK). All antibodies were previously diluted in EnVision FLEX Antibody Diluent (K8006 Agilent Technologies Denmark ApS Produktionsvej 42, 2600 Glostrup, Denmark) at a ratio of 1:2000 for β-catenin, 1:400 for Fzd8 antibody, 1:100 for Wnt5a and 1:100 for cyclin D1. Tissue sections were incubated overnight at 4 °C in a humidified chamber, followed by exposure to a secondary antibody conjugated with a horseradish peroxidase–labeled polymer. Antibody binding was visualized using a 1-minute reaction with liquid 3,3′-diaminobenzidine substrate chromogen. Subsequently, the sections were counterstained with hematoxylin QS (H-3404, Vector Laboratories; Burlingame, CA), mounted, and examined under a light microscope. Between each step, appropriate rinsing with Wash Buffer (S3006; Dako Cytomation, Glostrup, Denmark) was carried out. To verify specificity and exclude non-specific antibody interactions with the examined tissue, negative controls were included. Negative control reactions were performed in which the specific antibody of the detected antigens (β-catenin, Fzd8, Wnt5a and cyclin D1) was replaced with normal rabbit serum (Vector Laboratories; Burlingame, California) with the proper dilution. No positive immunoreactivity was observed. Staining outcomes were evaluated with an Olympus BX43 light microscope (Olympus Corp., Tokyo, Japan) equipped with an Olympus DP12 digital camera, and subsequently documented.

2.3. Quantitative Analysis

For each patient, twelve sections of benign prostatic hyperplasia and carcinoma tissue were analyzed, with three sections allocated to the immunostaining of β-catenin, Fzd8, Wnt5a, and cyclin D1, respectively. From every section, five randomly selected microscopic fields (0.785 mm2 each, captured at 200× magnification using a 20× objective and 10× eyepiece) were documented with an Olympus DP12 camera. Digital images were subsequently subjected to morphometric assessment with NIS Elements AR 3.10 (Nikon) image analysis software. In each field, the intensity of immunohistochemical labeling for all antibodies was quantified on a grayscale ranging from 0 to 256, where 0 corresponded to completely white/light pixels and 256 represented completely black pixels.

2.4. Real-Time PCR

Samples of benign prostatic hyperplasia and cancer were obtained from every individual and inserted in an RNA-later solution.

Total RNA was isolated with the NucleoSpin® RNA Isolation Kit (Machery-Nagel). The concentration and purity of the RNA were assessed using a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific). Subsequently, 1 μg of total RNA was reverse-transcribed into cDNA with the iScript™ Advanced cDNA Synthesis Kit for RT-qPCR (BIO-RAD). The cDNA synthesis was carried out in a final reaction volume of 20 μl employing a SureCycler 8800 thermal cycler (Agilent Technologies). For reverse transcription, the mixtures were incubated at 46 °C for 20 min, then heated to 95 °C for 1min and finally cooled quickly at 4 °C. Quantitative real-time PCR reactions were performed using Stratagene Mx3005P (Aligent Technologies) with the SsoAdvanced™ Universal SYBER® Green Supermix (BIORAD). Specific primers for β-catenin (CTNNB1), Fzd8 (FZD8), Wnt5a (WNT5A), cyclin D1 (CCND1) and GAPDH (GAPDH) were created by BIORAD Company.

The housekeeping gene GAPDH served as a reference for normalization of expression levels. To quantify transcript abundance, standard curves were generated individually for each gene using serial dilutions of PCR products. These PCR products were obtained by amplifying cDNA with the following gene-specific primers: CTNNB1 (qHsaCED0046518, BIO-RAD), FZD8 (qHsaCED0019650, BIO-RAD), WNT5A (qHsaCID0012240, BIO-RAD), CCND1 (qHsaCID0013833, BIO-RAD) and GAPDH (qHsaCED0038674, BIO-RAD). Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed in duplicate in a final reaction volume of 10 μl under the following cycling conditions: initial polymerase activation for 2 minutes at 95 °C, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation for 5 seconds at 95 °C and annealing/extension for 30 seconds at 60 °C. Control reactions included no-RT controls, template-free reactions, and melting curve analysis to verify amplification specificity and confirm the production of a single PCR product.

2.5. miRNA selection

To identify potential candidates, an in silico analysis was conducted to predict miRNAs that may target genes associated with benign prostatic hyperplasia and prostate adenocarcinoma. The focus was placed on miRNAs involved in the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway due to its critical role in urological cancer development. Candidate miRNAs were screened using the NCBI mRNA database (NCBI mRNA DB:

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). Based on this analysis, two miRNAs—106a-5p and 375-3p were selected for further investigation.

2.6. Extraction of miRNA from tissues

MiRNA was extracted from benign prostatic hyperplasia and prostate adenocarcinoma tissue samples using the miRNeasy Tissue/Cells Advanced Micro Kit (Qiagen, Copenhagen, Denmark, cat. no. 217684) according to the protocol prepared by the manufacturer. A section of 4 mm3 was removed from each tissue specimen and put into a 1.5 ml reaction tube along with 60 μl of lysis solution that contained 1% β-mercaptoethanol. Tissue samples were homogenized using a disposable polypropylene pestle and subsequently suspended in 700 μl of QIAzol Lysis Reagent (Qiagen, Copenhagen, Denmark; cat. no. 79306). All subsequent steps were performed following the manufacturer’s protocol. The RNA was eluted in 40 μl of RNase-free water (Qiagen, Copenhagen, Denmark; cat. no. 129112).

2.7. Quantification of RNA

The purity, concentration, and potential contaminants of the extracted miRNA were assessed using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

2.8. cDNA synthesis

Reverse transcription of RNA was performed using the miRCURY LNA RT Kit (Qiagen, Copenhagen, Denmark; cat. no. 339340). For fresh-frozen benign prostatic hyperplasia and prostate adenocarcinoma tissues, RNA concentrations were standardized to 5 ng/μl, and 2 μl of each sample was incorporated into a total reaction volume of 10 μl, which also contained 0.5 μl of UniSp6 RNA spike-in.

2.9. Digital PCR (dPCR) procedure

Digital PCR reactions were conducted using the miRCURY LNA miRNA PCR Assays kit (Qiagen, Copenhagen, Denmark; cat. no. 39306) in a 96-well plate format (Qiagen, Copenhagen, Denmark; cat. no. 250021) and the QIAcuity One nucleic acid detection qiagen instrument (Copenhagen, Denmark) using the QIAcuity Software Suite (Qiagen, Copenhagen, Denmark). The reaction mixture was prepared following the manufacturer’s instructions, comprising 4 μl of 3× EvaGreen PCR Master Mix (Qiagen, Copenhagen, Denmark; cat. no. 250111) and 1.2 μl of 10× miRCURY LNA PCR Assay (Qiagen, Copenhagen, Denmark, cat. no. 339306), 3 ul cDNA template (Qiagen, Copenhagen, Denmark) and 3.8 ul of RNase-free water (Qiagen, Copenhagen, Denmark, cat. no.129112). Total reaction volume was 12 ul. 96-well nanoplates with 8.500 partitions were used for the studies. The miRNAs analyzed in this study were 106a-5p (Qiagen, Copenhagen, Denmark; cat. no. YP00204563) and 375-3p (Qiagen, Copenhagen, Denmark; cat. no. YP00204362). The prepared reaction mix was initially dispensed into a standard PCR plate, from which the contents of each well were transferred to a QIAcuity Nanoplate (Qiagen, Copenhagen, Denmark; cat. no. 250021). Digital PCR was carried out under cycling conditions recommended by the manufacturer: an initial heat activation at 95 °C for 2 minutes, followed by 40 cycles of 15 seconds denaturation at 95 °C and 1 minute annealing/extension at 60 °C, and a final cooling step at 40 °C for 5 minutes. Upon completion, raw data were exported to the QIAcuity Software Suite (Qiagen, Copenhagen, Denmark) for analysis.

2.10. Statistical Analysis

All collected data were subjected to statistical analysis using the Statistica software package, Version 14.1. Statistical analysis revealed a lack of normality of the distribution of the obtained results. Results regarding immunoreactivity and expression of the analyzed parameters are expressed as medians accompanied by their respective minimum and maximum values. As distribution of the obtained data deviated from normality, the non-parametric Mann–Whitney U test was used to assess statistical significance. of differences between benign prostatic hyperplasia and prostate adenocarcinoma. Differences were considered statistically significant when the p-value was less than 0.05 (p < 0.05). Regarding the type of correlation used, linear regression analysis was applied to compare the relationships between the β-catenin, Fzd8, Wnt5a and cyclin D1 in BPH and cancer tissue. The main goal of the analysis was to assess the strength and direction of protein correlations.

This allowed for detailed insight into how the expression of one protein influence expression of another in benign prostatic hyperplasia and prostate adenocarcinoma. In order to analyze the correlation between the tested proteins, statistically calculated r2, the regression equation and the correlation coefficient. The outcomes of this analysis are presented as the β coefficient, indicating the percentage change in the dependent variable per unit change in the independent variable; r2, representing the proportion of variability in one variable explained by the other; and the associated p-value for statistical significance. A relationship between two variables was considered statistically significant when the p-value corresponding to the β coefficient was less than 0.05.

In the qRT-PCR, relative gene expression levels were determined using the ∆∆Ct method by comparing cycle threshold (Ct) values. All gene expression data were normalized to the housekeeping gene GAPDH. For miRNA analysis, expression levels in prostate adenocarcinoma samples were normalized relative to those in benign prostatic hyperplasia tissues.

3. Results

A total of 60 archival tissue blocks, fixed in formalin and embedded in paraffin, were included in the present study. The sample comprised 30 prostate cancers and 30 cases of BPH. Patients with prostate adenocarcinoma had a mean of 67.3 ± 8.0 years, which did not differ significantly from BPH (69.0 ± 7.5 years).

Histological examination using H&E staining showed that in BPH, glandular architecture was normal and with no signs of stromal overgrowth or invasion (

Figure 1A). In contrast, prostate cancer samples exhibited stromal infiltration along with notable cellular atypia (

Figure 1B).

Immunohistochemical evaluation

The antibodies used in the immunohistochemical reaction (β-catenin, Fzd8, Wnt5a and cyclin D1) gave a positive result in all sections examined (

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Table 1).

In BPH, a strong reaction was demonstrated showing β-catenin and Fzd8, especially in the membrane of glandular epithelial cells of the prostate (

Figure 2A and

Figure 3A), while in the tumor sections a positive reaction was found in the nuclei, some cells (

Figure 2B and

Figure 3B).

Immunodetection of Wnt5a protein showed strong staining in the cytoplasm of epithelial cells and a much weaker positive reaction in the stroma in BPH sections (

Figure 4A). Immunodetection of the Wnt5a receptor showed a positive reaction, with a high intensity in the tumor cells, while in the tumor stroma the result was negative or very weak (

Figure 4B).

The weakest immunohistochemical reaction was observed with the anti-cyclin D1 antibody. In BPH glandular cells, a relatively strong positive reaction was observed (

Figure 5A), whereas in neoplastic cells the reaction intensity was much weaker (

Figure 5B).

Assessment of immunohistochemical staining intensity through digital image analysis, corroborated by statistical testing, confirmed lower immunoreactivity of β-catenin, Fzd8, Wnt5a and cyclin D1 in prostate adenocarcinoma compared to benign prostatic hyperplasia. Data are shown as a medians with minimum and maximum values (

Table 1).

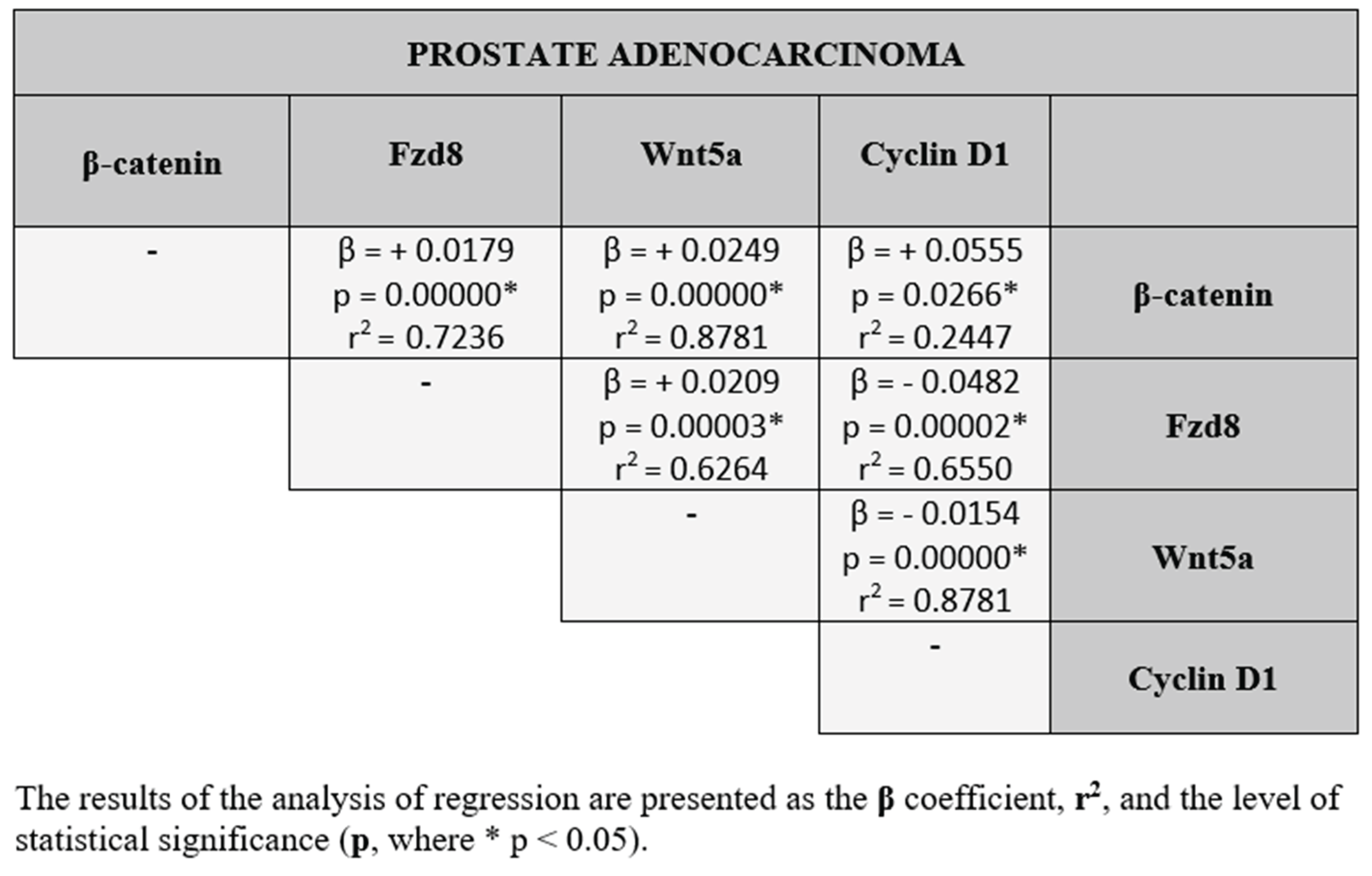

Statistical analysis showed co-expression between all parameters we examined. Statistically significant results are marked with an asterisk *(p ˂ 0.05). As for the relationships between the tested proteins, in the benign prostatic hyperplasia and prostate adenocarcinoma, both positive and negative correlations were found between the each protein studied.The results of the correlation analysis between the β-catenin, Fzd8, Wnt5a and cyclin D1, divided into benign prostatic hyperplasia and prostate adenocarcinoma are presented in the

Table 2 and

Table 3.

Real-time PCR

QRT-PCR analysis revealed lower expression of the β-catenin, Fzd8, Wnt5a and cyclin D1 genes in prostate cancer compared to benign prostatic hyperplasia tissues. Differences in the expression of the studied genes between BPH and prostate adenocarcinoma were not statistically significant (

Figure 6).

Digital PCR

A reaction mixture lacking a template—referred to as the no-template control (NTC) -was included as a negative control in the studies. For both analyzed miRNAs, the NTC yielded a fluorescence value of zero. Among the various parameters assessed in miRNA quantification, the most critical is the concentration, expressed as copies/μl. The evaluated miRNAs exhibited differential fluorescence intensities between BPH and prostate adenocarcinomas samples. Specifically, fluorescence signals of both miR-106a-5p and miR-375-3p were significantly higher in prostate adenocarcinoma tissues compared to BPH (

Figure 7). The expression levels of these miRNAs in prostate adenocarcinoma were normalized against the values obtained for BPH.

4. Discussion

Prostate adenocarcinoma is one of the most common malignant neoplastic diseases in men, which significantly affects the increase in mortality among this group worldwide. A major clinical challenge lies in precisely distinguishing prostate adenocarcinoma from BPH, given the distinct treatment protocols and management strategies for each condition. Consequently, further gaining insight into the molecular mechanisms responsible for prostate adenocarcinoma and BPH development is of critical importance [

11].

Literature reports indicate that certain miRNAs play a key role in the development of prostate adenocarcinoma. So far, no miRNAs with sufficient sensitivity have been implemented in clinical and diagnostic practice that could serve as noninvasive markers for the diagnosis of prostate adenocarcinoma and replace the currently used but imperfect PSA marker [

1,

8].

Recent studies have shown that certain miRNAs influence cancer cell growth by regulating the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway [

12,

13]. Therefore, the evaluation of molecular connections between selected miRNAs and components of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway may contribute to a better understanding of the pathomechanisms involved in the development of prostate adenocarcinoma, as well as BPH.

It has been demonstrated that miR-106a-5p can act as both an oncogene and a tumor suppressor in prostate cancer [

14,

15,

16]. Our study results demonstrated statistically significantly higher miRNA expression in prostate adenocarcinoma compared to BPH.

Similarly, Lu et al. [

14] also showed higher expression of miR-106a-5p in prostate cancer compared to non-cancerous tissue, suggesting its oncogenic role in prostate cancer.

While a research team led by Shen et al. [

16] demonstrated that overexpression of miR-106a in prostate cancer induces apoptosis, inhibits cell proliferation and migration, by targeting the 3′-UTR of interleukin-8 mRNA. According to these authors proliferation and invasive processes in prostate cancer cells are inhibited despite elevated miR-106a levels, suggesting a complex and dual function of miR-106a-5p in the pathogenesis of prostate adenocarcinoma.

Another study of plasma from patients with prostate adenocarcinoma demonstrated reduced expression of miR-106a-5p compared with men with benign prostatic hyperplasia [

8]. These differences may be due to the different regulation of miR-106a-5p between the tissue environment and body fluids such as plasma, which has important implications for the potential use of this miRNA as a marker and emphasizes the cautious interpretation of study results.

Our study also showed significantly higher expression of miR-375 in prostate adenocarcinoma compared to non-cancerous tissues.

MiR-375 has been identified as an important tumor suppressor that has been shown to be dysregulated in various types of cancer [

17,

18].

Studies have shown reduced expression of miR-375 and a suppressor role in many different types of cancers, while higher levels of miR-375-3p were found in prostate cancer compared to healthy tissues [

19].

Also, the studies of Abramovic et al. [

20] showed higher expression of miR-375-3p in plasma of prostate cancer patients compared to patients with benign hyperplasia. According to the authors of these studies, miR-375-3p measured in blood is a better biomarker for differentiating prostate cancer from benign hyperplasia than PSA.

Activation of the canonical Wnt/β-catenin pathway in prostate cancer is observed primarily in the late phase of this disease and causes resistance to therapy [

21].

Our results showed lower expression of Wnt pathway-related proteins: β-catenin, Fzd8, Wnt5a and cyclin D1 in prostate cancer compared to BPH tissues, but the differences were not statistically significant.

Accumulation and nuclear translocation of β-catenin leads to activation of the Wnt pathway and changes in the expression of genes responsible for cell proliferation [

22].

Our results showed lower β-catenin expression in prostate adenocarcinoma compared with benign prostatic hyperplasia. In contrast, Jung et al. [

23] demonstrated higher β-catenin expression in patients with prostate cancer. Discrepancies in results may be due to differences in the stage of cancer advancement or molecular differentiation of prostate cancer.

Importantly, in the cancer tissues we studied, β-catenin was located exclusively in the cell nucleus, which may suggest the activation of the canonical Wnt pathway, despite the lower level of β-catenin expression. This may indicate that the subcellular localization of this protein, and not only its level, is an important factor responsible for the functional activity of the Wnt pathway. It is likely that in the studied cases there is transcriptional activation of β-catenin, accompanied by a simultaneous reduction of its level in the cytoplasm, which could have contributed to the weakening of the immunohistochemical reaction resalt.

Fzd8 receptors by binding Wnt ligands induce cell signal transduction. In a recent study on long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), LINC00115 was shown to induce prostate cancer cell proliferation via the miR-212-5p/FZD5/Wnt/β-catenin axis, in which Fzd8 leads to the activation of the canonical Wnt pathway [

24]. This study and our own results support the hypothesis that the Wnt pathway and its components are crucial in the development of prostate adenocarcinoma.

The Wnt5a protein is a ligand for the Fzd8 receptor, activating the classical Wnt signaling pathway. It turns out that this protein plays a dual role in prostate cancer. It can promote cancer progression, through epithelial-mesenchymal transition or interactions with the androgen receptor pathway, or act as a suppressor under certain conditions by inhibiting the Wnt/β-catenin pathway [

25].

Studies conducted by a team led by Xie [

25] have shown that the function of the Wnt5a protein in prostate cancer depends on the stage of the disease and the tissue context. Due to the growing number of reports indicating the significant role of individual Wnt pathway components in cancer pathogenesis, the assessment of Wnt5a expression in prostate adenocarcinoma and BPH may be of great importance in guiding new therapies directly targeting the regulation of Wnt pathway activity.

In our study, we showed reduced expression of Wnt5a in prostate adenocarcinoma, which may indicate a suppressor role of the protein in this tumor. Thiele et al. [

26] confirmed that in prostate cancer, Wnt5a acting through FZD5 receptors, leads to reduced tumor cell proliferation and even induces cancer cell apoptosis.

Cyclin D1 is a proto-oncogene protein that is currently the subject of intensive research due to its key role in the cell cycle and the fact that its disruption can lead to cancer development. Our study demonstrated slightly lower cyclin D1 expression in prostate cancer compared to BPH.

The few studies on cyclin D1 expression in prostate adenocarcinomas have presented conflicting results [

27,

28]. Wang et al. [

27] observed overexpression of cyclin D1 in prostate adenocarcinoma, while the research team led by Yin [

28] reported reduced expression of this protein in prostate cancer, highlighting the heterogeneous nature of cyclin D1 regulation in prostate cancer progression.

In benign prostatic hyperplasia, we found a predominance of negative correlations between the expression levels of the studied proteins. This means that when the level of one protein increased, the level of another tended to decrease. Such correlations may suggest the presence of regulatory mechanisms, in which some proteins inhibit or neutralize the activity or expression of others. This pattern may reflect a biological balance typical of non-malignant tissue, in which various signaling pathways may function to maintain tissue homeostasis and prevent excessive cellular proliferation.

In prostate adenocarcinoma, correlation analysis revealed a predominance of positive associations between the studied proteins. This indicates that increased expression of one protein is accompanied by a similar increase in the expression of another. Such coordinated expression patterns may reflect the activation of interconnected biological pathways, in which proteins act synergistically to promote tumor-related processes. Differences in the correlations between studied proteins in BPH and prostate adenocarcinoma may suggest different pathological mechanisms underlying these conditions. Furthermore, they may indicate different protein interaction profiles in benign hyperplasia and prostate cancer.

MiRNAs can influence the activity of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway by altering the expression of Wnt ligands, β-catenin protein, receptors, or β-catenin-interacting complexes [

29]. The research team led by Shen [

30] did not prove that miR-106a-5p directly affects the Wnt/β-catenin pathway in prostate cancer, but they did demonstrated a role for this miRNA in association with interleukin-8, which may affect the activity of the canonical Wnt pathway. In addition, miR-106a-5p levels are regulated by c-Src/PI3K/Akt 30, which may interact with the Wnt pathway.

A more direct effect on the Wnt/β-catenin pathway has been demonstrated for miR-375-3p. In a study of gastric cancer, Guo et al. [

31] showed that miR-375-3p inhibits the Wnt pathway by reducing the expression of the YWHAZ protein, which regulates proliferation and apoptosis. This is valuable information on how miR-375-3p affects the activity of the Wnt pathway, influencing the mechanisms occurring in cancer cells. The canonical pathway is involved in cell adhesion processes, which are crucial in the context of metastasis and tumor invasion. It is possible that the loss of the adhesion protein E-cadherin promotes β-catenin release and leads to the activation of the Wnt pathway [

29,

32]. The present information confirms the influence of miR-375 on the activity of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway, however this is a complex regulation full of interactions between the involved components, which requires further analysis.

Our study results, indicating lower expression of β-catenin, Fzd8, Wnt5a and cyclin D1, may suggest attenuated activity of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway in prostate adenocarcinoma compared to benign prostatic hyperplasia. This is important in light of literature reports indicating a key role for activation of the canonical pathway in the progression of prostate adenocarcinoma and its bone metastases [

33,

34].

Interactions between the studied miRNAs and components of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway form a complex regulatory pathway that may be involved in the pathogenesis of prostate adenocarcinoma. Our findings highlight the potential of miR-106a-5p and miR-375-3p as future diagnostic biomarkers for prostate adenocarcinoma. However, further studies are needed to investigate the interactions between the studied miRNAs and the Wnt pathway proteins. In this context, particular attention should be paid to the study of β-catenin, which exhibits dual function, and context-dependent protein Wnt5a in various tumor microenvironments.

We are aware of the limitations of our study that should be taken into account. Due to the relatively small sample size, these data should be considered preliminary and worth validating on larger data sets. Our finding that adenocarcinoma tissues exhibit significantly higher expression of miR-106a-5p and miR-375-3p and lower expression of canonical Wnt signaling pathway components is potentially interesting but requires cautious interpretation. In further studies, we intend to validate it in larger cohorts of patients with prostate cancer and BPH.