1. Introduction

The development of vision in children is a fascinating process that occurs in several stages during the first years of life. The visual system is not fully developed at birth and gradually matures until the age of 7–8 years. This development includes improvements in visual acuity as well as the ability to perceive space and colors. In early infancy, approximately up to six months of age, children begin to recognize faces and objects, but their vision remains very blurry and underdeveloped. During the first three years of life, there is a rapid improvement in the ability to focus on objects and coordinate eye movements. It is during this period that fundamental visual functions are established, such as the ability to track moving objects or recognize distances. Between the ages of three and five, as children explore the world around them more actively, their visual acuity continues to improve, although spatial vision and the perception of fine details are still developing. By the age of 7 to 8, most visual development processes are complete. At this stage, children have fully developed the basic vision necessary for daily activities such as reading, writing, and recognizing objects at a distance. Some studies suggest that minor changes in more refined visual functions may still occur beyond this age, but most visual abilities stabilize and are ready for further refinement [

1].

It is interesting that this entire process can be influenced by several factors, including genetic predispositions, environment, and lifestyle. For proper visual development, environmental stimulation is crucial, including adequate exposure to natural light and maintaining a balanced distance between the child and the objects they focus on [

2]. Studies suggest that long periods of sitting at desks and focusing on nearby objects, such as textbooks or writing, can contribute to the development of myopia (nearsightedness). This problem is more common among children who spend most of their time concentrating on objects up close, which can lead to the elongation of the eyeball and subsequent vision deterioration [

3,

4] In today's world, where children spend more time with digital devices, it is important to recognize that excessive screen time can negatively affect the development of vision, particularly in children who have not yet completed the full development phase [

5]. It is essential to pay attention to regular eye check-ups to ensure that no issues go unnoticed. Early diagnosis and correction of visual impairments can significantly impact the quality of life of children and their ability to learn and grow throughout their development [

6]. Frequent breaks during lessons support students' overall mental health and concentration [

7].

Myopia (nearsightedness) is becoming a global problem, with the greatest challenges observed in East Asia, where the prevalence of myopia among children and adolescents is significantly higher than in other countries [

8]. China, along with South Korea and Singapore, is one of the countries with very high and increasing rates of myopia in recent decades [

9]. In China, the prevalence of myopia in the school-age population ranges from 60-70%, with some urban areas approaching 90%. The high prevalence is linked to the intense school system, long study hours, and limited time for outdoor activities [

10,

11]. Another factor is the high level of academic pressure: In countries like China, South Korea, and Singapore, the school system is very intense, which results in long hours spent with books and electronic devices.

Based on the above information, we decided to analyze the review studies from the most affected countries and to provide a summary of myopia prevention for other countries that currently struggle with myopia less but since COVID-19, the risk of myopia has been a global problem due to homeschooling [

12].

3. Results

After reading the full texts, only 22 studies were selected, focusing on the ergonomic risks of environments in which Asian children operate, and their potential negative impact on the development of children's vision. Based on these studies, preventive measures will be recommended for mitigating the negative effects of the environment on the development of children's vision for the purposes of this narrative study.

Study 1:

Study investigated posture in Chinese children with myopia (ages 6–13) during near tasks like video games, reading, and writing. Using motion tracking, the study measured working distances and head tilt. Children with myopia consistently used shorter working distances across tasks—especially when gaming (21.3 cm), followed by writing (24.9 cm) and reading (27.2 cm). Head tilt was greatest during gaming (63.5°). A negative correlation was found between working distance and head tilt (r = −0.53). No significant posture differences were found between refractive error groups. The findings suggest short working distances, especially during handheld gaming, may contribute to myopia progression [

13].

Study 2:

Study studied myopia prevalence and risk factors among 5,216 primary school students (avg. age 9.25) in Fushun, China. Myopia was found in 29.5% of students, with significant differences by gender and grade. Protective factors included proper reading distance, good lighting, study breaks, eye exercises, and daily outdoor activity. Risk factors were female gender, higher grade, >4 hours of homework daily, reading while lying down, and parental myopia. The study emphasizes the importance of targeted, evidence-based prevention strategies for schoolchildren [

14].

Study 3:

Study reviewed risk factors for juvenile myopia in children aged 6–18, with a focus on genetics and environment—especially during the COVID-19 pandemic. Key risk factors included family history, near work, low outdoor time, and higher education levels. The review highlighted the strong environmental influence and a lack of clarity around screen use and genetic mechanisms. It called for further research into how these factors contribute to myopia development and early intervention strategies [

15].

Study 4:

Study conducted a post-COVID cross-sectional study on myopia among 1,722 children (ages 7–9) in Shanghai. Myopia prevalence was 25.6%. Risk factors included older age, family history, close reading distance, head-down posture while writing, and poor sleep habits. Surprisingly, higher household income and reading while lying down were linked to lower risk. The study emphasizes the importance of addressing visual habits and sleep to prevent myopia, with attention to gender-specific strategies [

16].

Study 5:

This study evaluated the impact of a school-based intervention on myopia development in elementary students. Part of the Wenzhou Epidemiology of Refraction Error Study, it followed 1,524 students (average age 7.3 years) over 2.5 years with two annual exams. The intervention group received regular reminders, while the control group did not. The intervention group experienced slower myopia progression (-0.49 D) compared to the control group (-0.65 D). For children without myopia at the start, the intervention reduced progression by 27.5%. The intervention group also showed smaller axial length elongation (0.56 mm vs. 0.61 mm) and more children engaged in daily eye exercises. In conclusion, the school intervention significantly slowed myopia progression, especially in children without myopia at the start [

17].

Study 6:

This study aimed to determine the prevalence of myopia among schoolchildren in Ningbo and examine the link between reading/writing postures and myopia development. It was a cross-sectional study involving 3,256 students aged 8 to 19. Participants underwent uncorrected visual acuity tests and non-cycloplegic autorefraction, while their reading and writing postures and other behaviors were also assessed. The prevalence of myopia was 61.49% in primary, 81.43% in secondary, and 89.72% in high school students. The study found that a reading distance greater than 33 cm reduced myopia risk in girls, particularly in primary (OR = 0.55) and secondary school (OR = 0.37). Maintaining proper reading distance and posture may help prevent myopia and offer significant public health benefits [

18].

Study 7:

This study aimed to explore the quality of life, neck dysfunction, and posture in individuals with mild myopia and analyze the relationship between myopia and posture. It included 11 individuals with mild myopia (MG) and 11 without myopia (CG). Quality of life was assessed using the SF-36 questionnaire, neck pain with the Visual Analog Scale (VAS), and discomfort with the Neck Bournemouth Questionnaire (NBQ). Vision-related health was measured with the NEI-VFQ25 questionnaire, and posture was evaluated using the New York Posture Rating Chart. While no significant differences were found in overall quality of life or posture between the groups, significant differences were observed in the NBQ (p < 0.05), NEI-VFQ25 (p < 0.05), and VAS (p < 0.01). A significant correlation (r = -0.691) was found between myopia severity and head posture [

19].

Study 8:

This study explored myopia prevalence and risk factors in Chinese primary school students in Hong Kong, comparing two educational systems. It involved 159 students from a state-funded school and 223 from an international school, aged 8 to 10 years. Measurements included non-cycloplegic refraction, axial length, and questionnaires on screen time, outdoor activities, and demographics. The state-funded school had a higher myopia prevalence (37.5%) compared to the international school (12.8%). Risk factors differed by school: in the state-funded school, myopia was linked to parental myopia and near work, while at the international school, it was associated with the father’s education level. The study suggests parental education may help protect against myopia [

20].

Study 9:

The study aimed to explore the relationship between myopia progression and the age at which children in China start school. It followed 1,463 children aged 6 to 9 years in Wenzhou for 2.5 years

; measuring refraction

; axial length (AL)

; and corneal curvature radius (CRC). Myopia was defined as a spherical equivalent of less than −1.0D. The study found significant myopia progression in older children

; with 7-year-olds in higher grades showing greater changes in spherical equivalent (SE) and AL. The prevalence of myopia was higher in children in higher grades

; even for the same age. Children who started school younger were more prone to developing myopia. The study suggests that children should start school after the age of 7 [

21]

Study 10:

The aim of the study was to assess the prevalence of myopia among primary school students and evaluate the risk factors associated with myopia. This school-based, cross-sectional study was conducted on students from two primary schools in Jiaojiang, Taizhou, China. A total of 556 students aged 9 to 12 years were included. Tests for uncorrected visual acuity and non-cycloplegic refractive error were conducted to determine myopia. Each student filled out a questionnaire about potential factors related to myopia. A multiple logistic regression analysis of risk factors was performed. The overall prevalence of myopia among these students was 63.7%, ranging from 53.4% in 4th grade to 72.5% in 6th grade. The multiple logistic regression analysis showed that the adjustment of desk and chair heights according to the students' growing height and the presence of myopia in parents were significantly associated with myopia in these students. The results indicated that myopia among primary school students was associated with both environmental and hereditary factors [

22].

Study 11:

Myopia is a major public health issue in East and Southeast Asia, with around 80% of students in mainland China becoming myopic by the end of 12 years of schooling. High myopia (> -6D) affects 10-20% of these students. While interventions like outdoor time have had some success in Taiwan and Singapore, myopia prevalence remains high. Traditional methods in China, such as eye exercises, have failed. In contrast, atropine eye drops and orthokeratology are widely used in Singapore and Taiwan to slow progression. New lenses that induce myopic defocus are also available. Recently, China has focused more on myopia prevention, with President Xi Jinping supporting educational reforms, reducing school pressures, and promoting outdoor play, which could be key to addressing myopia [

9].

Study 12:

This study evaluated myopia prevalence in rural Chinese schoolchildren with low educational pressure. It included 2,432 first-grade and 2,346 seventh-grade students in 2016. Results showed significantly higher myopia in seventh-grade students (29.4% vs. 2.4%) and longer axial lengths. Adjusting for reading and outdoor time reduced myopia prevalence by 15.1% and 33.4%, respectively. The study suggests environmental factors, rather than genetics, may explain the lower myopia prevalence in rural China [

23].

Study 13:

This three-year study investigated the impact of reading posture, distance, and angle on myopia progression in 240 myopic children (average age 10.9). The results showed that myopia progressed the most in children who read while seated at the start (−3.58 D) and the least in those who read lying on their back (−2.35 D). Shorter reading distance was linked to greater myopia in girls. A downward reading angle was mildly associated with faster progression. The study concluded that seated reading posture at the onset of myopia led to greater progression [

24].

Study 14:

This study in Urumqi, China, found a 47.5% myopia prevalence among 6,883 schoolchildren. Parental myopia was highly heritable (66.57% in boys). The study showed that poor reading and writing habits combined with parental myopia significantly increased the risk of myopia—by 10.99 times for bad habits and 5.92 times for poor posture. The findings emphasize the importance of targeting children with myopic parents for prevention [

25].

Study 15:

This study explored the effect of school-based measures on myopia prevention in 8,319 children across 26 elementary schools. It found that the myopia incidence was 36.49%. Children with well-implemented class breaks had a 20% lower risk of developing myopia. Outdoor activities during physical education also reduced myopia risk in 10-11-year-olds. Properly adjusted desks and chairs helped slow myopia progression. The study highlights that effective school measures, such as outdoor time and appropriate furniture, can prevent myopia and its progression [

26].

Study 16:

This study assessed reading distances in children with and without myopia, including those with inadequate and full correction. It involved 2,363 children aged 6-8 from the Hong Kong Children Eye Study. The results showed that myopic children with inadequate correction had the shortest reading distances (23.37 cm) compared to children without myopia (24.20 cm) and those with full correction (24.81 cm). Shorter reading distances were linked to myopia (OR 1.67), but this connection was not significant for fully corrected myopic children. The study concludes that inadequate correction of myopia is not recommended as a strategy to slow myopia progression [

27].

Study 17:

This study assessed myopia prevalence and its associations with the educational environment among 3,596 primary school students in Hefei, China. The study found an overall myopia prevalence of 27.1%. Key factors associated with myopia included gender, grade level, parents' education, academic level, weekend homework hours, tutoring, and extracurricular reading. After adjusting for confounders, no significant link was found between school-day homework and myopia. The study concluded that high educational demands, particularly outside of school (e.g., weekend homework and tutoring), were linked to higher myopia prevalence. Reducing academic workload outside of school could help prevent myopia [

28].

Study 18:

This study analyzed myopia prevalence and its relationship with ocular parameters and behavior among primary school students in China, comparing data from 2012 and 2019. The study found that the myopia prevalence slightly increased from 37.7% in 2012 to 39.9% in 2019, but there were no statistically significant differences in spherical equivalent refraction (SER) between the two years. In 2019, girls had a slight increase in myopia prevalence, while boys showed a decrease in axial length and AL/CR ratio. The study also found that children reduced screen time and near work, but the time spent outdoors decreased, which remains a concern. The findings suggest that while myopia prevalence was under control by 2019, insufficient outdoor time is still a problem, especially for boys [

29].

Study 19:

Study examined myopia prevalence and risk factors among 34,644 students (avg. age 11.9) in Shenyang, China. Visual acuity was tested using standard methods. Myopia was found in 60% of students—45% mild, 13% moderate, and 1.9% high. Risk factors included female gender, higher grade level, family history, and prolonged near work. Protective factors were regular eye exercises, outdoor time, working distances over 30 cm, and >8 hours of sleep. Environmental influences—such as near work habits and sleep—play a key role in myopia development and should be targeted for prevention [

30].

Study 20:

This study analyzed myopia prevalence and contributing factors among children and adolescents in Hangzhou, involving 31,880 students from 113 schools. It found an overall myopia prevalence of 55.3%, with rates increasing as students advanced in school: 5.8% in kindergarten, 34.9% in elementary school, 74.2% in middle school, and 85.0% in high school. Girls had a higher prevalence than boys, and urban students had higher rates than those from suburban areas. Key risk factors for myopia included older age, parental myopia, excessive homework time, poor reading/writing posture, prolonged screen exposure, and inadequate lighting. The study recommends a comprehensive approach to myopia prevention, involving collaboration between schools, hospitals, families, and students, focusing on reducing these risk factors and promoting early prevention [

31].

Study 21:

This study evaluated refractive changes and myopia incidence in 3,070 schoolchildren in the Yongchuan district of Chongqing, Western China. It included both a cross-sectional study (2006) and a longitudinal follow-up (2011-2012) with 1,858 participants. The results showed an average refractive progression of −2.21 diopters over the study period, with annual progression of −0.43 D. Myopia progression was linked to younger age, female sex, and higher initial refractive errors. The cumulative incidence of myopia was 54.9%, with an annual incidence of 10.6%. Myopia was more common in girls and older children. The study concluded that myopia progression and incidence in Western China were higher than in many other regions, contributing to the increasing trend in myopia prevalence in China [

32].

Study 22:

This study analyzed myopia and high myopia prevalence among 35,614 elementary and junior high school students in Shandong, with an average age of 12.38 years. The overall prevalence of myopia was 68.02%, with 5.90% having high myopia. Among 9th graders, myopia prevalence was 85.54%, and high myopia was 13.13%. Risk factors for myopia included gender (more common in girls), family history of myopia, excessive homework time, and insufficient sleep. Eye exercises were linked to a lower risk of developing myopia, while the use of mobile devices and reading while lying down were associated with myopia, but not high myopia. The study concluded that myopia and high myopia are influenced by genetic and environmental factors like prolonged near work and lack of sleep. Prevention efforts should focus on improving sleep habits and reducing screen time [

33].

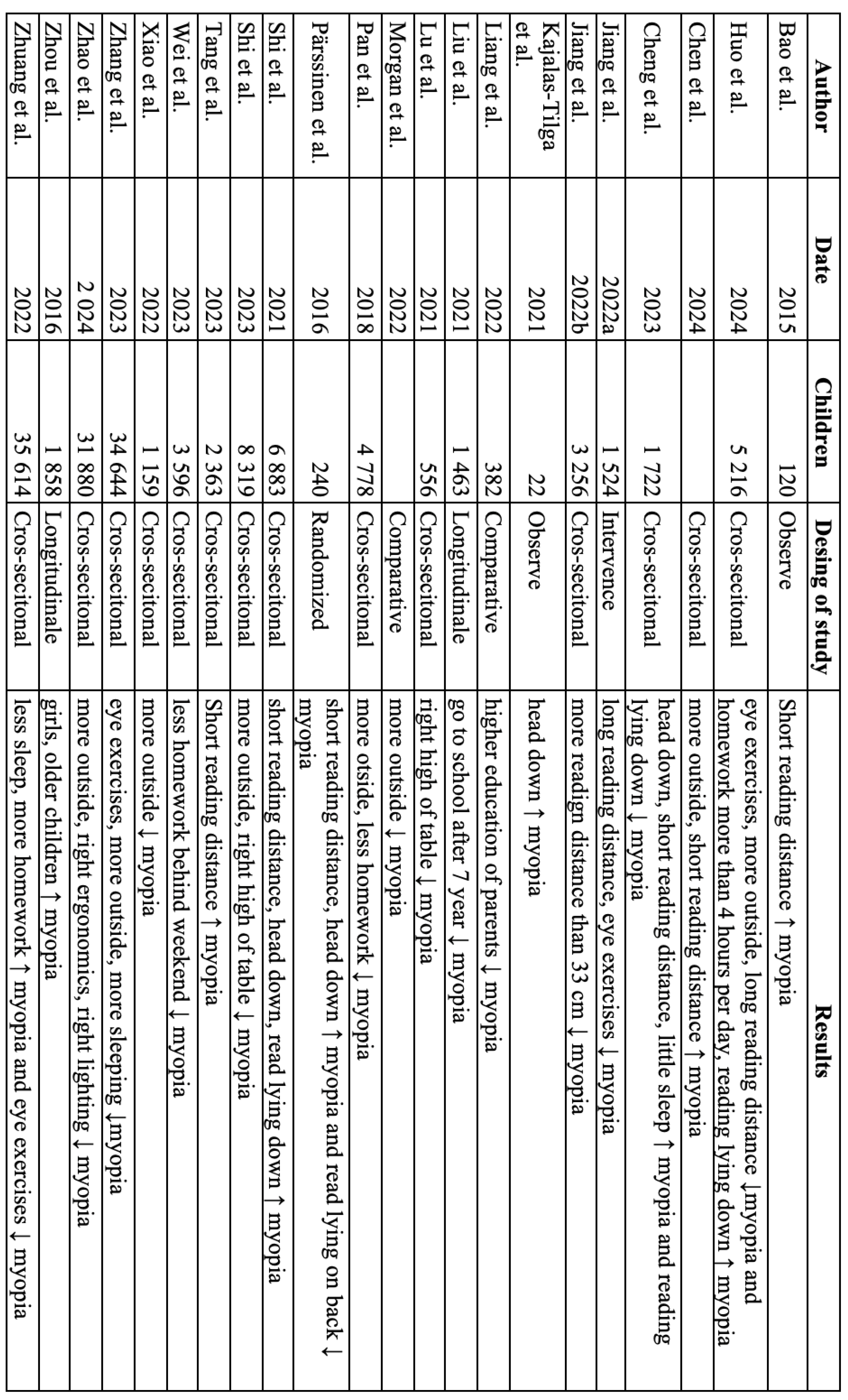

Figure 1.

There is a table studies and their results.

Figure 1.

There is a table studies and their results.

4. Discussion

From the above studies, general recommendations can be made that may help delay the onset and progression of myopia in children. It is clear that before starting school, vision is rarely affected by eye conditions, and as children move through higher grades, the number of vision issues increases. The studies indicate that children who start school after the age of 7 have a lower risk of developing myopia.

In general, older children, girls, and children with a family history of myopia are at higher risk. Some studies also highlight the importance of parental education as a significant factor in predisposition to myopia.

Regarding the management of the school environment and organization of studies, it is recommended not to exceed two hours of reading or writing per day, not to assign more than 4 hours of homework per day during the week, and not to give homework or tutoring on weekends. In terms of school ergonomics, it is important to maintain a reading or writing distance of at least 30 cm from the object, with correct posture and cervical spine alignment, and a smaller viewing angle. The height of desks and chairs should be adjusted for each student individually to allow for proper posture. Studies show that regularly spending time outdoors in daylight during breaks and generally increasing outdoor learning hours is highly effective. Studies that included eye exercises as an intervention also showed positive results.

As a very important environmental factor, some studies mention the need for more than 8 hours of sleep per day.

The debate arises in studies dealing with the issue of reading while lying down; only one study specifies the exact position being discussed – lying on the back. Therefore, reliable conclusions cannot be made from these recommendations. Studies observing the effect of reading while lying on the back as a way to reduce the prevalence of myopia are contradicted by other studies, which, on the contrary, consider reading while lying down a risk factor. However, we must again add that these studies do not specify which position is being referred to – whether on the side, stomach, or back.

Another interesting factor is the finger holding the writing instrument, which blocks the student’s line of sight, as a possible factor for the development of myopia. However, the author of the study did not explain further how this could be prevented.