1. Introduction

The carotid body (CB) is a principal peripheral chemoreceptor [

1,

2] located bilaterally at the bifurcation of the common carotid artery. It consists of clusters of neuron-like chemoreceptive cells called type I or glomus cells in intimate association with glial-like cells called type II or supporting cells; clusters of type I cells and type II cells are arranged around the many sinusoidal capillaries and arterioles within CB [

3]. CB is innervated by glossopharyngeal petrosal afferents, as well as by sympathetic efferents that originates in the superior cervical ganglion [

4,

5]. Variations in blood levels of oxygen, carbon dioxide, pH, and some metabolites detected by type I cells are conducted to the central nervous system where they play a key role in cardiorespiratory regulation (see [

2]).

The communication between cells and nerves within CB are complex. There is evidence for reciprocal chemical synapses and electrical coupling between type I cells and afferent nerve fibres as well as between neighbouring type I cells [

6,

7,

8]. In addition, functional relationships exist between nerves and type II cells, and between type I and type II cells (see [

9]). This complex network gave rise to the concept of "tripartite synapse" to refer to the relationships between type I cells, type II cells, and afferent nerve terminals [

10]. Tripartite synapse allows to process of sensory stimuli within CB involving both autocrine and paracrine pathways [

11].

Type I cells are the sensors and transducers of chemical stimuli, and when depolarize in response to hypoxia, hypercapnia or changes in pH [

1] they respond releasing a variety of neurotransmitters and neuromodulators [

12,

13,

14] both excitatory and inhibitory, that act through the corresponding receptors mainly present in nerve afferent terminals but also in type I cells. Among these neurotransmitters is adenosine 5'-triphosphate (ATP).

The extra-mitochondrial ATP released by type I cells of CB can act as an excitatory [

14,

15] or inhibitory [

16,

17] neurotransmitter. ATP binds on P2X2 and P2X3 purinergic receptors located in afferent terminals [

18,

19,

20,

21] and in the majority (>65%) of neurons in the sensory ganglia [

22] including the petrosal ganglion [

18,

23,

24]. But ATP can also act on the purinergic receptors P2Y1 and P2Y2 localized in type II cells [

15,

25,

26,

27] leading to the further release of ATP opening of large-pore ATP-permeable pannexin-1 channels [

15,

27,

28]. Both P2Y channels and pannexin-1 are expressed in type II cells [

29,

30,

31]. Altogether these data suggest that type II cells may participate in the neurochemical networks of CB via ‘gliotransmission’ especially throughout pathways involving ATP [

31,

32,

33].

As far as we know, only the P2X2 and P2X3 receptors have been detected in the mammalian CB, although the sensory ganglia of the glossopharyngeal expressed at least four different subtypes of P2X receptors: P2X2, P2X3, P2X4, and P2X7 [

34]. Interestingly, P2X7R is expressed in the satellite glial cells [

22,

35,

36,

37] together with pannexin-1 [

38]. P2X7 receptor and pannexin-1 form a dynamic channel pore responsible for calcium influx in these cells [

39,

40].

Type II cells of CB and satellite glial cells in sensory ganglia are closely related expressing different common antigens such as glial fibrillary acidic protein, S100 protein, vimentin or nestin [

41,

42,

43]. Here we considered the possibility that like satellite glial cells in sensory ganglia the glia-like type II cells in CB express P2X7 receptor and pannexin 1 providing new data on the putative role of type II cells in the purinergic neurotransmission of CB, and in ATP-mediated paracrine communication within CB. In the present study, immunofluorescence techniques associated with confocal laser microscopy were used to analyze the presence of P2X7 receptor (P2X7r) and pannexin 1 in the human CB.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Human Tissue Samples

Tissue samples containing the common carotid bifurcation, carotid sinus, and CB were obtained during organ procurement for transplantation from eight donors (5 males, 3 females; 38–68 years) who died in traffic accidents at the Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias (Oviedo, Spain). Petrosal ganglia (n = 4) and superior cervical sympathetic ganglia (n = 4) were also dissected and included in the study. Samples were rinsed in saline at 4° C, fixed in 10% formaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) for 24h at 4° C, dehydrated, and paraffin-embedded using standard protocols.

All procedures complied with Spanish legislation and the principles of the Helsinki Declaration II. Samples were stored at the Department of Morphology and Cell Biology, University of Oviedo Biobank (National Registry of Biobanks, Ref. C-0001627), authorized by the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness (30 November 2012) and ca be used exclusively for research purposes.

2.2. Fluorescence and Double Immunofluorescence

For individual or simultaneous detection of P2X7r and Pannexin 1 with synaptophysin (SYN) and S100 proteins (S100P) paraffin-embedded sections (10 μm) were mounted on gelatine-coated slides. Following rehydration in Tris-HCl buffer (0.05 M, pH 7.5) containing 0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and 0.1% Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich), the nonspecific binding was blocked with 25% calf bovine serum in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) for 30 min. nonspecific binding was blocked with 10% fetal calf serum (F2442, Sigma-Aldrich). Thereafter sections were incubated overnight at 4° C in a humid chamber with a 1:1 (v/v) mixture of polyclonal antibodies anti-P2X7r or anti-pannexin 1 and monoclonal antibodies against NFP, SYN, or S100P diluted in Tris-HCl buffer (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) supplemented with 0.1% BSA, 0.2% fetal calf serum, and 0.1% Triton X-100 (

Table 1).

After rinsing in TBS, sections were incubated sequentially with CFL488-conjugated bovine anti-rabbit IgG (1:200; sc-362260, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Heidelberg, Germany) for 1 h, followed by Cy™3-conjugated donkey anti-mouse IgG (1:100; Jackson ImmunoResearch, Baltimore, MD, USA) for 1 h. Both steps were performed in a dark, humid chamber at room temperature, with phosphate-buffered saline containing Tween 20 washes between incubations. Nuclear counterstaining was performed using 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; 10 ng/mL) in Fluoromount-G mounting medium (Southern Biotech, Birmingham, AL, USA).

Negative controls were processed in parallel by omitting the primary antibodies, substituting them with non-immune rabbit or mouse sera. Under these conditions, no specific immunoreactivity was detected.

Confocal imaging was carried out using a Leica TCS SP8 X confocal microscope coupled to a Leica DMI8 fluorescence microscope. Images were acquired with Leica Application Suite X software (version 1.8.1; Leica Microsystems CMS GmbH, Wetzlar, Germany) at the Optical Microscopy and Image Processing Unit, University of Oviedo, and analysed with ImageJ software (version 1.43g; McMaster Biophotonics Facility, Ontario, Canada).

2.3. Quantitative Analysis

Quantitative image analysis was performed on the CB processed for all the antigens investigated using an automated system (Quantimet 550, Leica Microsystems; QWIN software). Whole sections were scanned at 50x magnification using a SCN400F scanner (Leica Biosystems™); the images were processed with the SlidePath Gateway LAN program (Leica Biosystems™) at the Histopathology Laboratory, University Institute of Oncology of the Principality of Asturias. Ten randomly selected fields (5 mm² each) were analysed per section in five sections spaced 100 μm apart, totalling 400 fields. The immunoreactive area for S100P was defined as 100% of type II cell area. Areas of merge of S100P+SYN, S100P+P2X7r and S100P+pannexin 1 were quantified to estimate the percentage of type II cells that express P2X7r or pannexin 1. Areas of merge of SYN+P2X7r and SYN+pannexin 1 were also quantified. Results correspond to immunofluorescent area per mm² and presented as mean ± SEM.

In parallel, nerve density was quantified from NFP-immunofluorescence in the same sampling scheme (10 fields/section, 5 sections, 400 fields). The area of NFP immunoreactivity was considered 100% of nerve profiles, and the overlap of NFP with P2X7r or pannexin 1 was taken as the proportion of nerves co-expressing the respective markers. Results correspond to immunofluorescent area per mm².

Quantitation was performed in duplicate by two independent observers, and results were homogeneous between replicates.

3. Results

3.1. Immunolocalization of P2X7r and Pannexin-1 in the Human Carotid Body

Immunofluorescence for P2X7r (

Figure 1a) and pannexin 1 (

Figure 1b) within the glomeruli of the CB forms a broad cellular network whose pattern corresponds to that of type II cells. The immunolabeling pattern is granular. In the petrosal ganglion, the distribution of P2X7r is consistent with the labelling of satellite glial cells, whereas neuronal somas were not immunolabeled (

Figure 1c). In the cervical sympathetic ganglion, P2X7r glial cells were detected in satellite glial cells, but also in a subpopulation of neurons (

Figure 1d).

To exclude that P2X7r and pannexin 1 are present in type I cells of the CB, a double immunolabeling of these proteins was performed with others specific to type I cells (synaptophysin), type II cells (S100 protein) and nerves (neurofilament proteins).

The simultaneous detection of P2X7r with synaptophysin showed that both are located in cell populations secreted within the CB, so it can be assured that this purinergic receptor is not localized in type I cells. P2X7r-positive cells (type II cells) are arranged around the synaptophysin-positive cells (type I). However, at the interface of type I and type II cells and in some isolated drops, there seems to be co-localization of both proteins (

Figure 2a-d). The results for the co-detection of pannexin 1 and synaptophysin were identical (

Figure 2e-h).

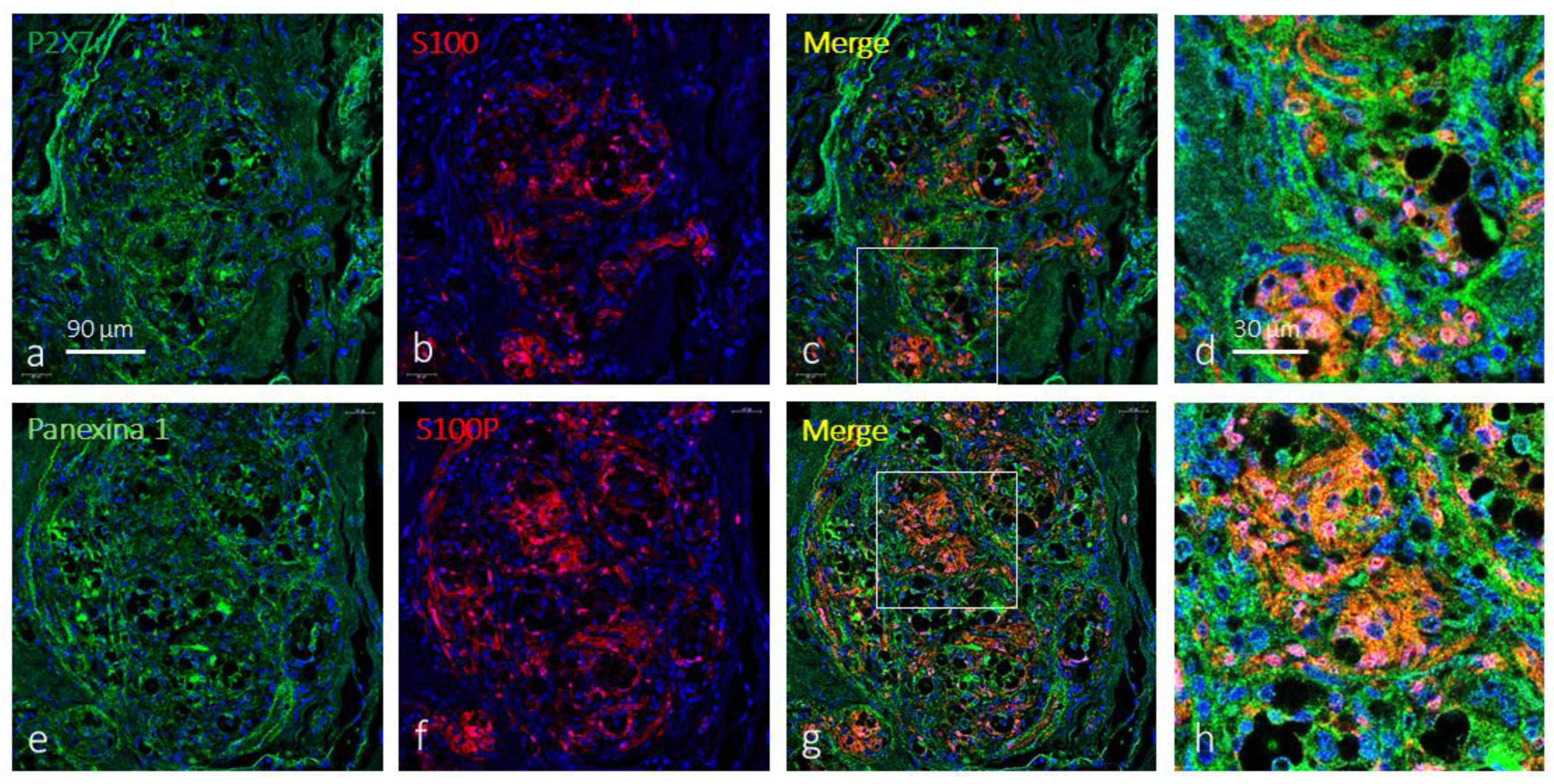

Then, to confirm that P2X7r and pannexin 1 are located in type II cells, a simultaneous incubation was performed for the detection of both proteins with the S100 protein. This protein within the CB marks a nerve network, more or less dense, whose morphology is consistent with the labelling of type II cells. The results show that both P2X7r (

Figure 3a-d) and pannexin 1 (

Figure 3e-h) are in type II cells. In addition, there are also cells within the glomeruli of the CB that are positive for P2X7r and pannexin 1 that do not express the S100 protein; that is, based only on immunofluorescence, P2X7r and pannexin 1 are present in other cells of the CB that are not type II cells.

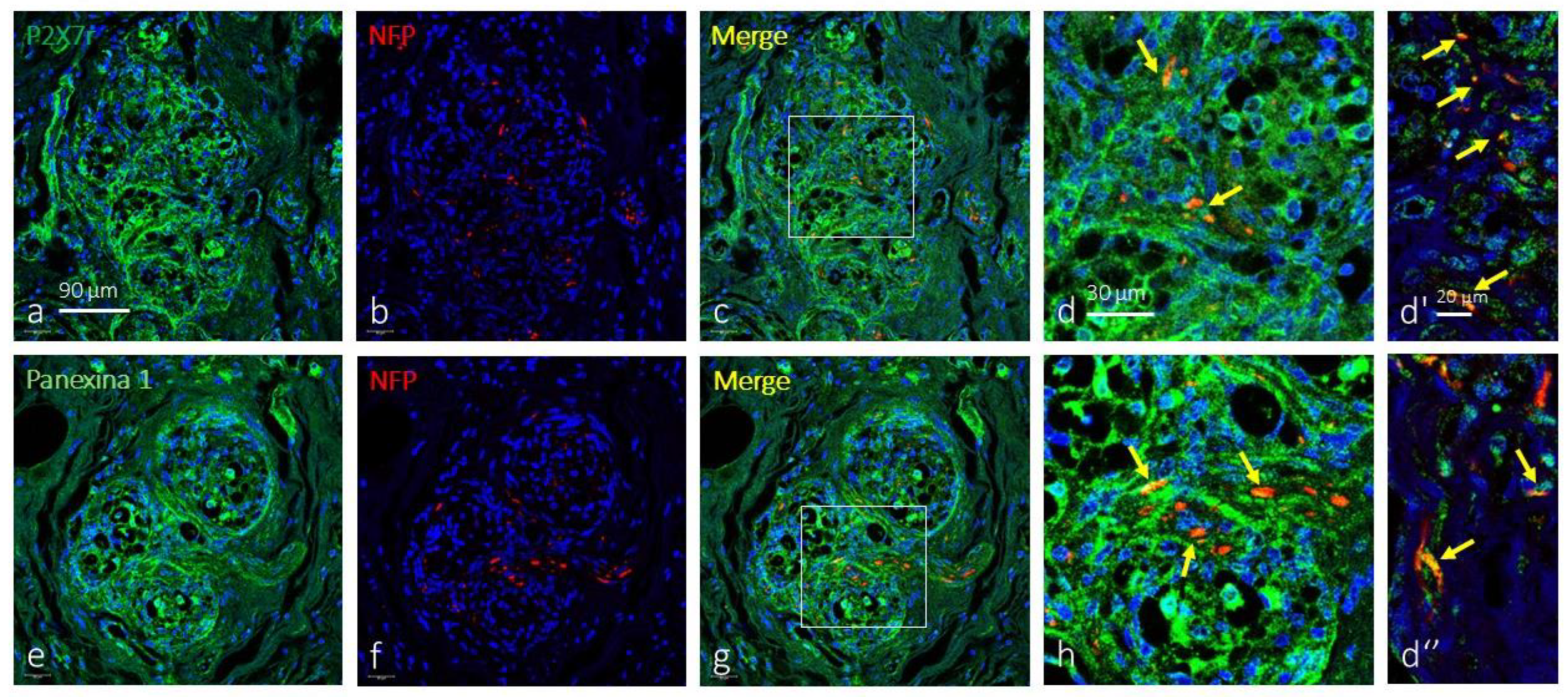

We also investigated whether P2X7r and pannexin 1 are found in the nerves that innervate the CB. The co-localization of P2X7r and pannexin 1 with neurofilament proteins shows that all neurofilament-positive nerve fibres express both proteins, especially in nerves located in the most peripheral part of the CB (

Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Immunofluorescence-based detection of P2X7r and pannexin 1 in the human carotid body. Cells containing P2X7r (green fluorescence in a) and pannexin 1 (green fluorescence in e) as well as S100 protein (S100P) form a dense meshwork throughout glomic glomeruli consistent with their presence in type II cells. Merge (yellow fluorescence) P2X7r (c,d) or pannexin 1 (g,h) with S100P show cell colocalization of P2X7r and pannexin 1 with S100P thus confirming both are localized in type II cells. Objective: 60x/1.25 oil; pinhole: 1; XY resolution: 156 nm.; and Z resolution: 334 nm.

Figure 3.

Immunofluorescence-based detection of P2X7r and pannexin 1 in the human carotid body. Cells containing P2X7r (green fluorescence in a) and pannexin 1 (green fluorescence in e) as well as S100 protein (S100P) form a dense meshwork throughout glomic glomeruli consistent with their presence in type II cells. Merge (yellow fluorescence) P2X7r (c,d) or pannexin 1 (g,h) with S100P show cell colocalization of P2X7r and pannexin 1 with S100P thus confirming both are localized in type II cells. Objective: 60x/1.25 oil; pinhole: 1; XY resolution: 156 nm.; and Z resolution: 334 nm.

Figure 4.

Immunofluorescence-based detection of P2X7r and pannexin 1 in the human carotid body. P2X7r (green fluorescence in a) and pannexin 1 (green fluorescence in e) within the CB are present in a cell meshwork consistent with its presence in type II cells. However, merge (yellow fluorescence) of P2X7r (c and d-d’-d’’) and pannexin 1 (g and h) with neurofilament proteins (red fluorescence in b and f) show the presence of both proteins in some nerve profiles (yellow arrows). Objective: 60x/1.25 oil; pinhole: 1; XY resolution: 156 nm.; and Z resolution: 334 nm.

Figure 4.

Immunofluorescence-based detection of P2X7r and pannexin 1 in the human carotid body. P2X7r (green fluorescence in a) and pannexin 1 (green fluorescence in e) within the CB are present in a cell meshwork consistent with its presence in type II cells. However, merge (yellow fluorescence) of P2X7r (c and d-d’-d’’) and pannexin 1 (g and h) with neurofilament proteins (red fluorescence in b and f) show the presence of both proteins in some nerve profiles (yellow arrows). Objective: 60x/1.25 oil; pinhole: 1; XY resolution: 156 nm.; and Z resolution: 334 nm.

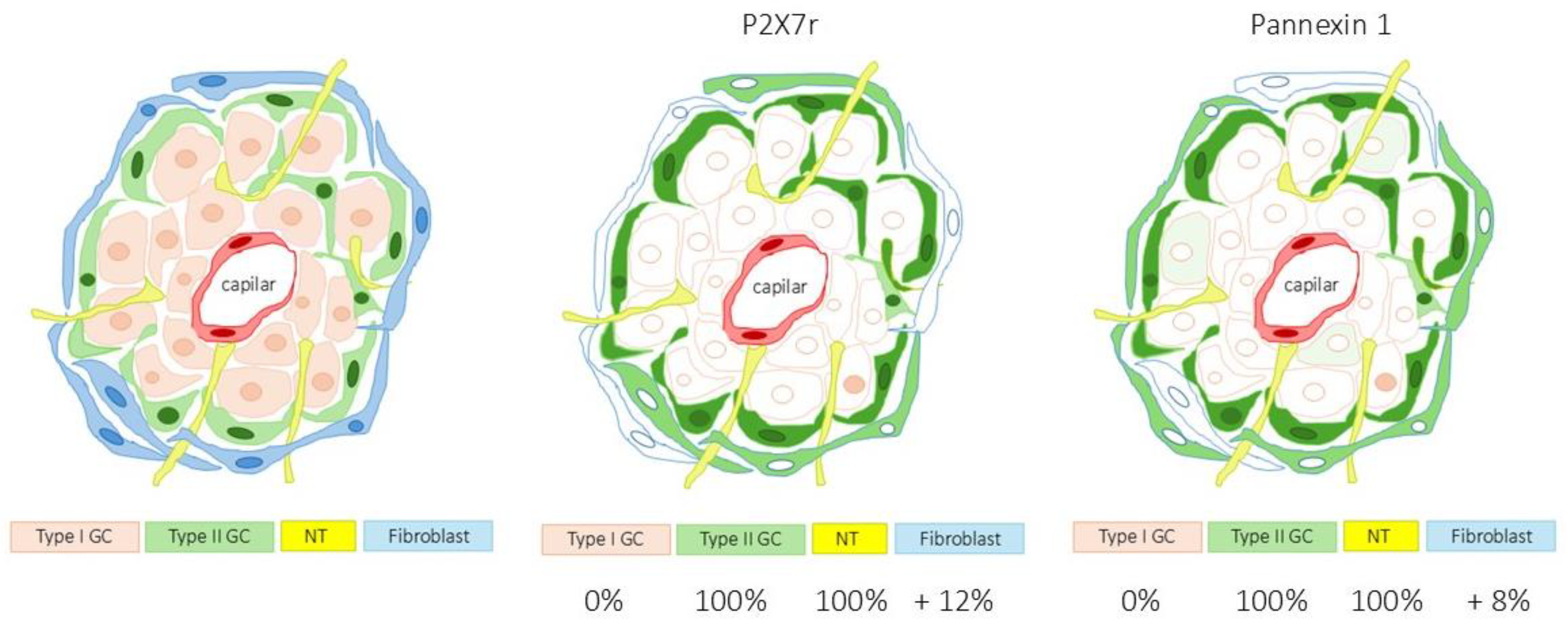

The area occupied by the specific immunoreaction of P2X7r was 48.6 ± 1.3% of the total section, and the area occupied by the merge of SYN + P2X7r was 0.0% although residual merge was observed; the merge of NFP + P2X7r was 100%, and 12.3 ± 1.8% of the total section was P2X7r positive and SYN, NFP and S100 negative this indicating that P2X7r is present in a cells other than type I, type II or nerves (

Table 2 and

Diagram 1). The quantitative results for pannexin 1 in the CB paralleled those of P2x7r (

Table II and

Diagram 1).

Therefore, P2X7r and pannexin 1 are absent from type I glomus cells of the human CB while they are present in type II cells and nerves. Values were similar in all the samples analysed, without gender- or age-dependent variations.

Diagram 1.

Percentage of area occupied by P2X7r and pannexin 1 in the carotid body in type II glomus cells (green) and nerves (yellow). Immunofluorescence was also detected in non-glomus cells presumably fibroblasts. Type I glomus cells lacked both P2X7r and pannexin 1. This diagram completes

Table 2 and shows the distribution of immunofluorescence for P2X7r and pannexin 1 in a relatively manner.

Diagram 1.

Percentage of area occupied by P2X7r and pannexin 1 in the carotid body in type II glomus cells (green) and nerves (yellow). Immunofluorescence was also detected in non-glomus cells presumably fibroblasts. Type I glomus cells lacked both P2X7r and pannexin 1. This diagram completes

Table 2 and shows the distribution of immunofluorescence for P2X7r and pannexin 1 in a relatively manner.

3.2. Immunolocalization of P2X7r and Pannexi-1 in Petrosal and Cervical Sympathetic Ganglia

In the petrosal ganglion of the glossopharyngeal nerve, the soma of the afferents to the CB were devoid of immunofluorescence for P2X7r although in some neurons a weak immunofluorescence of granular pattern is observed. In contrast, P2X7r was detected in most glial satellite cells (

Figure 5a.c). However, in the cervical sympathetic ganglion, both neurons and glial cells were P2Xr positive (

Figure 5d-f).

Therefore, based on the present results of immunofluorescence in the human CB P2X7r and pannexin 1 are absent from type I glomus cells and restricted to type II glomus cells,

4. Discussion

The CB is organized into glomeruli, which are clusters of chemoreceptor cells (type I cells) and supporting glia-like cells (type II cells) in close contact with afferent nerve endings and a profuse network of capillaries [

3]. Type I cells release several classical neurotransmitters but also ATP [

12,

13,

14,

21,

44]. There is generally accepted that ATP, released from type I cells during chemotransduction, is the principle excitatory neurotransmitter that initiates the chemoreflex by acting on purinergic receptors on the afferent nerve terminals [

2,

10,

11,

12,

44]. It is now known that ATP released by type I cells acts on purinergic receptors [

45] located in afferent nerve endings [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24] and in type II cells [

25,

26,

27,

28]. This system appears to be a potential paracrine mechanism ATP signaling at the chemosensory synapse and fits within the concepts of tripartite synapses and gliotransmission [

10,

11,

33] (

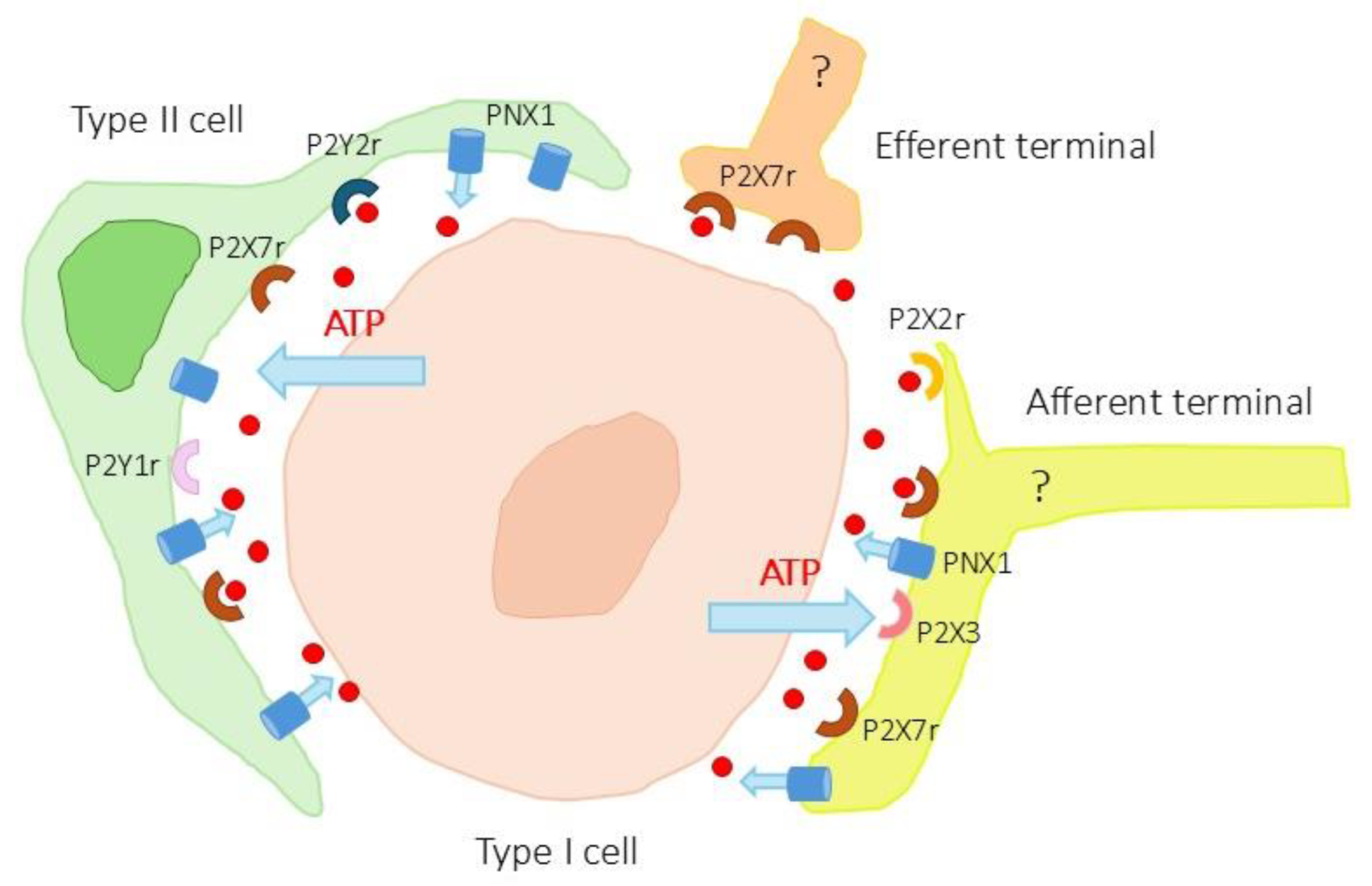

Figure 6). In addition, type II cells express pannexin 1 membrane channels related to ATP release [

11,

29,

30,

31] and which are a part of the ATP-induced ATP release hypothesis [

11].

The present research work was designed to analyze whether the human CB expresses ATP channels of type pannexin 1 and ATP receptors of type P2X7. The study was carried out on human material using immunofluorescence techniques associated with confocal laser microscopy. For the identification of type I and type II cells of the CB, as well as afferent and efferent nerve terminals, antibodies that had already demonstrated their specificity in this organ and that function in human material fixed and included in paraffin were used. In all the samples analysed, with no apparent differences in relation to age or sex, specific immunofluorescence was detected with a fine granular cytoplasmic pattern and not membrane as would be expected due to the location of both proteins in the cell membrane. Probably the thickness of the sections on which the study was carried out is responsible for this pattern. To demonstrate the presence of P2X76 and pannexin 1 in membranes, immunocytochemistry work with electron microscopy is necessary.

Figure 6.

Schematic representation of ATP-mediated neurotransmission-gliotransmission. Type I cells release ATP that acts on P2X2 and P2X3 receptors on afferent terminals and on P2Y1, P2Y2 and P2X7 receptors on type II cells. In turn, the pannexin 1 (PNX1) channels present in type II cells would release more ATP from these cells. The presence of P2X7 and pannexin 1 in the afferent and efferent terminals should be taken with caution pending physiological and pharmacological studies.

Figure 6.

Schematic representation of ATP-mediated neurotransmission-gliotransmission. Type I cells release ATP that acts on P2X2 and P2X3 receptors on afferent terminals and on P2Y1, P2Y2 and P2X7 receptors on type II cells. In turn, the pannexin 1 (PNX1) channels present in type II cells would release more ATP from these cells. The presence of P2X7 and pannexin 1 in the afferent and efferent terminals should be taken with caution pending physiological and pharmacological studies.

In our work we have detected P2X7R and pannexin 1, two molecules linked to ATP neurotransmission, in type II glomic cells, but not in type I chemosensory cells. The presence of ATP-permeable pannexin 1 channels in type II cells in the CB of mammals had already been demonstrated previously [

11,

29,

30,

31]. Our findings confirm that pannexin 1 is also expressed in type II cells of the human CB. In contrast, here we demonstrate for the first time the presence of P2X7 receptors in type II cells of the human CB. As far as we know, this receptor has not been described in this location, although its presence in the glial satellite cells of the sensory and sympathetic ganglia. It is important to note that this purinergic receptor is expressed in the glial satellite cells of the sensory ganglia and not in neurons [

32,

35,

36,

37].

Type II cells have historically been considered supporting cells; however, many now accept that they act to modulate CB chemotransmission through paracrine mechanisms [

11,

31,

46] especially those involving ATP. Moreover, type II cells, in absence of type I cells, can trigger afferent firing via ATP release [

47]. Activation of purinergic channels in type II cells lead to opening of large-pore pannexin 1 channel and furthers release of ATP [

27,

28,

31]. Therefore Zang et al. [

28] proposed that type II cells of the CB function as ATP amplifiers during chemotransduction via paracrine activation of P2Y receptors and pannexin 1 channels leading to ATP-induced ATP release. Whether P2X7r functions similarly to P2Y channels in type II cells will need to be clarified in future studies. The function of P2X7r in type II cells of the human CB, if any, is still unknown. In the spinal ganglia, modulates different intracellular pathways, including pro-inflammatory and tumour-promoting cascades (see [

48]). Importantly, pannexin 1 channels, in addition to mediating actions linked to ATP, mediate other actions of other neurotransmitters with 5-HT [

29].

Apart from type II cells in the CB, we have observed immunofluorescence for P2X7r in nerve terminals and therefore we investigate whether they are also detected in the neurons of the petrosal and cervical sympathetic ganglia, which is where the somas of the neurons that innervate the CB are located. P2X7r was located in the satellite glial cells of the sensory ganglia as earlier reported [

22,

34,

35,

36,

37] but not in sensory neurons. Conversely in the cervical sympathetic ganglia P2X7r was predominantly neuronal as previously observed [

49,

50]. Therefore, only the efferent innervation of CB would contain P2X7r. Further studies are needed to definitively establish this issue. On the other hand, although in our work we have not analysed the localization of pannexin 1 in sensory ganglia (the antibody used bound forming a non-specific background), previous studies have located it in satellite glial cells [

38,

51,

52].

An interesting fact that should be highlighted is that pannexin 1 can also be activated by mechanical stretch [

53]. Recently, we have observed that type II cells in the human CB express PIEZO1 and PIEZO2, two proteins that are part of mechanosensitive and mechanotransducer channels [

54]. The connection between pannexin 1 and Piezo channels should be studied.

Altogether The present results add new information to the reality of that within the CB chemosensory complex, the glia-like type II cell might participate in a tripartite synapse, where purinergic neurotransmission is modulated. In turn ATP helps to coordinate activity within this network and thereby modulate afferent firing frequency during chemotransduction [

33].

5. Conclusions

Type II cells of human BC express P2X7r and pannexin 1 that are probably paracrine involved in the tripartite synapse, where neurotransmission is modulated. The functional implications of these findings need to be resolved in future studies.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, J.A.V and Y.G-M.; methodology, M.A., R.M. and P.C.; validation, J.A.V., T.C., Y.G-M. and J.M-C.; formal analysis, J.A.V.; investigation, G.M-B., E.A.; resources, X.X.; data curation, M.A., R.M. and P.C.; writing—original draft preparation, T.C., O.G-S. and J.A.V.; writing—review and editing, J.A.V., J.M-C. and Y.G-M.; visualization, G.M-B., E.A. J.A.V. and J.M-C.; supervision, J.A.V., Y.G-M. and J.M-C.; project administration, J.A.V and O.G-S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

P.C. was supported by a grant, “Severo Ochoa Program,” from the Government of the Principality of Asturias (PA-21-PF-BP20-122).

Institutional Review Board Statement

“The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethical Committee for Biomedical Research of the Principality of Asturias, Spain (Cod. CElm, PAst: Proyecto 266/18, 19 November 2018).

Informed Consent Statement

The collection of the material used in this research, although it is of human origin, did not require informed consent since it is part of it was deposited in the Department of Morphology and Cell Biology of the University of Oviedo, as part of the National Registry of Biobanks (Collections Section, Ref. C-0001627), created and authorized by the Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness of the Government of Spain on 30 November 2012.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

P.C. was supported by a grant, “Severo Ochoa Program,” from the Government of the Principality of Asturias (PA-21-PF-BP20-122). The authors thank Marta Alonso Guervós for her technical assistance with confocal microscopy.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kumar, P.; Prabhakar, N.R. Peripheral chemoreceptors: function and plasticity of the carotid body. Compr. Physiol. 2012, 2, 141–219. [CrossRef]

- Iturriaga, R.; Alcayaga, J.; Chapleau, M.W.; Somers, V.K. Carotid body chemoreceptors: physiology, pathology, and implications for health and disease. Physiol. Rev. 2021, 101, 1177–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, C.; Almaraz, L.; Obeso, A.; Rigual, R. Carotid body chemoreceptors: from natural stimuli to sensory discharges. Physiol. Rev. 1994, 74, 829–898. [CrossRef]

- McDonald, D.M.; Mitchell, R.A. The innervation of glomus cells, ganglion cells and blood vessels in the rat carotid body: a quantitative ultrastructural analysis. J. Neurocytol. 1975, 4, 177–230. [CrossRef]

- Schulz, S.-A.; Wöhler, A.; Beutner, D.; Angelov, D.N. Microsurgical anatomy of the human carotid body (glomus caroticum): features of its detailed topography, syntopy and morphology. Ann. Anat. 2016, 204, 106–113. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonald, D.M. Peripheral chemoreceptors: Structure–function relationships of the carotid body. In Regulation of Breathing; Hornbein, T.F., Ed.; Lung Biology in Health and Disease, Volume 17; Marcel Dekker: New York, NY, USA, 1981; pp. 105–320. [Google Scholar]

- Kondo, H. Are there gap junctions between chief (glomus, type I) cells in the carotid body chemoreceptor? A review. Microsc. Res. Tech. 2002, 59, 227–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eyzaguirre, C. Electrical synapses in the carotid body nerve complex. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 2007, 157, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argent, L.P.; Bose, A.; Paton, J.F.R. Intracarotid body intercellular communication. J. R. Soc. N. Z. 2022, 53, 332–361. [CrossRef]

- Nurse, C.A. Synaptic and paracrine mechanisms at carotid body arterial chemoreceptors. J. Physiol. 2014, 592, 3419–3426. [CrossRef]

- Nurse, C.A.; Piskuric, N.A. Signal processing at mammalian carotid body chemoreceptors. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2013, 24, 22–30. [CrossRef]

- Iturriaga, R.; Alcayaga, J. Neurotransmission in the carotid body: transmitters and modulators between glomus cells and petrosal ganglion nerve terminals. Brain Res. Rev. 2004, 47, 46–53. [CrossRef]

- Nurse, C.A. Neurotransmission and neuromodulation in the chemosensory carotid body. Auton. Neurosci. 2005, 120, 1–9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nurse, C.A. Neurotransmitter and neuromodulatory mechanisms at peripheral arterial chemoreceptors. Exp. Physiol. 2010, 95, 657–667. [CrossRef]

- Piskuric, N.A.; Nurse, C.A. Expanding role of ATP as a versatile messenger at carotid and aortic body chemoreceptors. J. Physiol. 2013, 591, 415–422. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Xu, F.; Tse, F.W.; Tse, A. ATP inhibits the hypoxia response in type I cells of rat carotid bodies. J. Neurochem. 2005, 92, 1419–1430. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carroll, J.L.; Boyle, K.M.; Wasicko, M.J.; Sterni, L.M. Dopamine D2 receptor modulation of carotid body type I cell intracellular calcium in developing rats. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 2005, 288, L910–L916. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Zhong, H.; Vollmer, C.; Nurse, C.A. Corelease of ATP and ACh mediates hypoxic signalling at rat carotid body chemoreceptors. J. Physiol. 2000, 525, 143–158. [CrossRef]

- Pijacka, W.; Moraes, D.J.; Ratcliffe, L.E.; Nightingale, A.K.; Hart, E.C.; da Silva, M.P.; Machado, B.H.; McBryde, F.D.; Abdala, A.P.; Ford, A.P.; Paton, J.F. Purinergic receptors in the carotid body as a new drug target for controlling hypertension. Nat. Med. 2016, 22, 1151–1159. [CrossRef]

- Yokoyama, T.; Saino, T.; Nakamuta, N.; Kusakabe, T.; Yamamoto, Y. Threedimensional architectures of P2X2/P2X3immunoreactive afferent nerve terminals in the rat carotid body as revealed by confocal laser scanning microscopy. Histochem. Cell Biol. 2016, 146, 479–488. [CrossRef]

- Buttigieg, J.; Nurse, C.A. Detection of hypoxiaevoked ATP release from chemoreceptor cells of the rat carotid body. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004, 322, 82–87. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.C.; Akopian, A.N.; Sivilotti, L.; Colquhoun, D.; Burnstock, G.; Wood, J.N. A P2X purinoceptor expressed by a subset of sensory neurons. Nature 1995, 377, 428–431. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prasad, M.; Fearon, I.M.; Zhang, M.; Laing, M.; Vollmer, C.; Nurse, C.A. Expression of P2X2 and P2X3 receptor subunits in rat carotid body afferent neurons: role in chemosensory signalling. J. Physiol. 2001, 537, 667–677. [CrossRef]

- Lowe, M.; Park, S.J.; Nurse, C.A.; Campanucci, V.A. Purinergic stimulation of carotid body efferent glossopharyngeal neurons increases intracellular Ca2+ and nitric oxide production. Exp. Physiol. 2013, 98, 1199–1212. [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Tse, F.W.; Tse, A. ATP triggers intracellular Ca2+ release in type II cells of the rat carotid body. J. Physiol. 2003, 549, 739–747. [CrossRef]

- Tse, A.; Yan, L.; Lee, A.K.; Tse, F.W. Autocrine and paracrine actions of ATP in rat carotid body. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2012, 90, 705–711. [CrossRef]

- Piskuric, N.A.; Nurse, C.A. Effects of chemostimuli on [Ca2+]i responses of rat aortic body type I cells and endogenous local neurons: comparison with carotid body cells. J. Physiol. 2012, 590, 2121–2135. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Piskuric, N.A.; Vollmer, C.; Nurse, C.A. P2Y2 receptor activation opens pannexin1 channels in rat carotid body type II cells: potential role in amplifying the neurotransmitter ATP. J. Physiol. 2012, 590, 4335–4350. [CrossRef]

- Murali, S.; Zhang, M.; Nurse, C.A. Evidence that 5HT stimulates intracellular Ca2+ signalling and activates pannexin1 currents in type II cells of the rat carotid body. J. Physiol. 2017, 595, 4261–4277. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taruno, A. ATP release channels. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 808. [CrossRef]

- Nurse, C.A.; Leonard, E.M.; Salman, S. Role of gliallike type II cells as paracrine modulators of carotid body chemoreception. Physiol. Genomics 2018, 50, 255–262. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murali, S.; Nurse, C.A. Purinergic signalling mediates bidirectional crosstalk between chemoreceptor type I and gliallike type II cells of the rat carotid body. J. Physiol. 2016, 594, 391–406. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leonard, E.M.; Nurse, C.A. The Carotid Body “Tripartite Synapse”: role of gliotransmission. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2023, 1427, 185–194. [CrossRef]

- Campanucci, V.A.; Zhang, M.; Vollmer, C.; Nurse, C.A. Expression of multiple P2X receptors by glossopharyngeal neurons projecting to rat carotid body O2chemoreceptors: role in nitric oxidemediated efferent inhibition. J. Neurosci. 2006, 26, 9482–9493. [CrossRef]

- Serrano, A.; Mo, G.; Grant, R.; Pare, M.; O’Donnell, D.; Yu, X.H.; Tomaszewski, M.J.; Perkins, M.N.; Seguela, P.; Cao, C.Q. Differential expression and pharmacology of native P2X receptors in rat and primate sensory neurons. J. Neurosci. 2012, 32, 11890–11896. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, C.; Li, G.; Gu, Y.; Huang, L.Y. Activation of P2X7 receptors in glial satellite cells reduces pain through downregulation of P2X3 receptors in nociceptive neurons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 16773–16778. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Huang, Q.; Song, X.; Ford, N.C.; Zhang, C.; Xu, Q.; Lay, M.; He, S.Q.; Dong, X.; Hanani, M.; Guan, Y. Purinergic signaling between neurons and satellite glial cells of mouse dorsal root ganglia modulates neuronal excitability in vivo. Pain 2022, 163, 1636–1647. [CrossRef]

- Dahl, G. The Pannexin1 membrane channel: distinct conformations and functions. FEBS Lett. 2018, 592, 3201–3209. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Virgilio, F. Liaisons dangereuses: P2X(7) and the inflammasome. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2007, 28, 465–472. [CrossRef]

- Crocetti, L.; Guerrini, G.; Giovannoni, M.P.; Melani, F.; Lamanna, S.; Di Cesare Mannelli, L.; Lucarini, E.; Ghelardini, C.; Wang, J.; Dahl, G. New Panx1 blockers: synthesis, biological evaluation and molecular dynamic studies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 4827. [CrossRef]

- Kameda, Y. Immunoelectron microscopic localization of vimentin in sustentacular cells of the carotid body and the adrenal medulla of guinea pigs. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 1996, 44, 1439–1449. [CrossRef]

- IzalAzcárate, A.; Belzunegui, S.; San Sebastián, W.; GarridoGil, P.; VázquezClaverie, M.; López, B.; Marcilla, I.; Luquin, M.A. Immunohistochemical characterization of the rat carotid body. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 2008, 161, 95–99. [CrossRef]

- MartínezBarbero, G.; GarcíaMesa, Y.; Cobo, R.; Cuendias, P.; MartínBiedma, B.; GarcíaSuárez, O.; Feito, J.; Cobo, T.; Vega, J.A. Acidsensing ion channels’ immunoreactivity in nerve profiles and glomus cells of the human carotid body. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 17161. [CrossRef]

- Zapata, P. (2007). Is ATP a suitable co-transmitter in carotid body arterial chemoreceptors? Respiratory Physiology & Neurobiology, 157(1), 106-115. [CrossRef]

- Burnstock, G., & Knight, G. E. (2004). Cellular distribution and functions of P2 receptor subtypes in different systems. International Review of Cytology, 240, 31-304. [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Sáenz, P., & López-Barneo, J. (2020). Physiology of the carotid body: From molecules to disease. Annual Review of Physiology, 82, 127-149. [CrossRef]

- Leonard, E. M., Salman, S., & Nurse, C. A. (2018). Sensory processing and integration at the carotid body tripartite synapse: Neurotransmitter functions and effects of chronic hypoxia. Frontiers in Physiology, 9, 225. [CrossRef]

- Pegoraro, A., Grignolo, M., Ruo, L., Ricci, L., & Adinolfi, E. (2024). P2X7 variants in pathophysiology. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 25, 6673. [CrossRef]

- Li, G. H., Lee, E. M., Blair, D., Holding, C., Poronnik, P., Cook, D. I., Barden, J. A., & Bennett, M. R. (2000). The distribution of P2X receptor clusters on individual neurons in sympathetic ganglia and their redistribution on agonist activation. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 275(37), 29107-29112. [CrossRef]

- Tu, G., Zou, L., Liu, S., Wu, B., Lv, Q., Wang, S., Xue, Y., Zhang, C., Yi, Z., Zhang, X., Li, G., & Liang, S. (2016). Long noncoding NONRATT021972 siRNA normalized abnormal sympathetic activity mediated by the upregulation of P2X7 receptor in superior cervical ganglia after myocardial ischemia. Purinergic Signalling, 12(3), 521-535. [CrossRef]

- Penuela, S., Gehi, R., & Laird, D. W. (2013). The biochemistry and function of pannexin channels. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes, 1828(1), 15-22. [CrossRef]

- Spray, D. C., & Hanani, M. (2019). Gap junctions, pannexins and pain. Neuroscience Letters, 695, 46-52. [CrossRef]

- Bao, L., Locovei, S., & Dahl, G. (2004). Pannexin membrane channels are mechanosensitive conduits for ATP. FEBS Letters, 572(1-3), 65-68. [CrossRef]

- Alba, E., García-Mesa, Y., Cobo, R., Cuendias, P., Martín-Cruces, J., Suazo, I., Martínez-Barbero, G., Vega, J. A., García-Suárez, O., & Cobo, T. (2025). Immunohistochemical detection of PIEZO ion channels in the human carotid sinus and carotid body. Biomolecules, 15(3), 386. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).