Submitted:

24 September 2025

Posted:

25 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

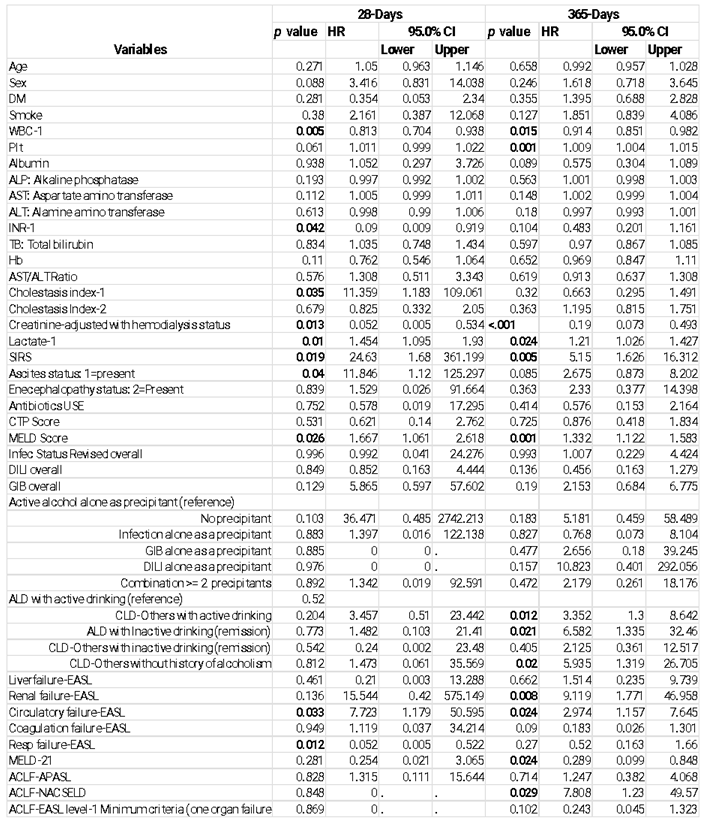

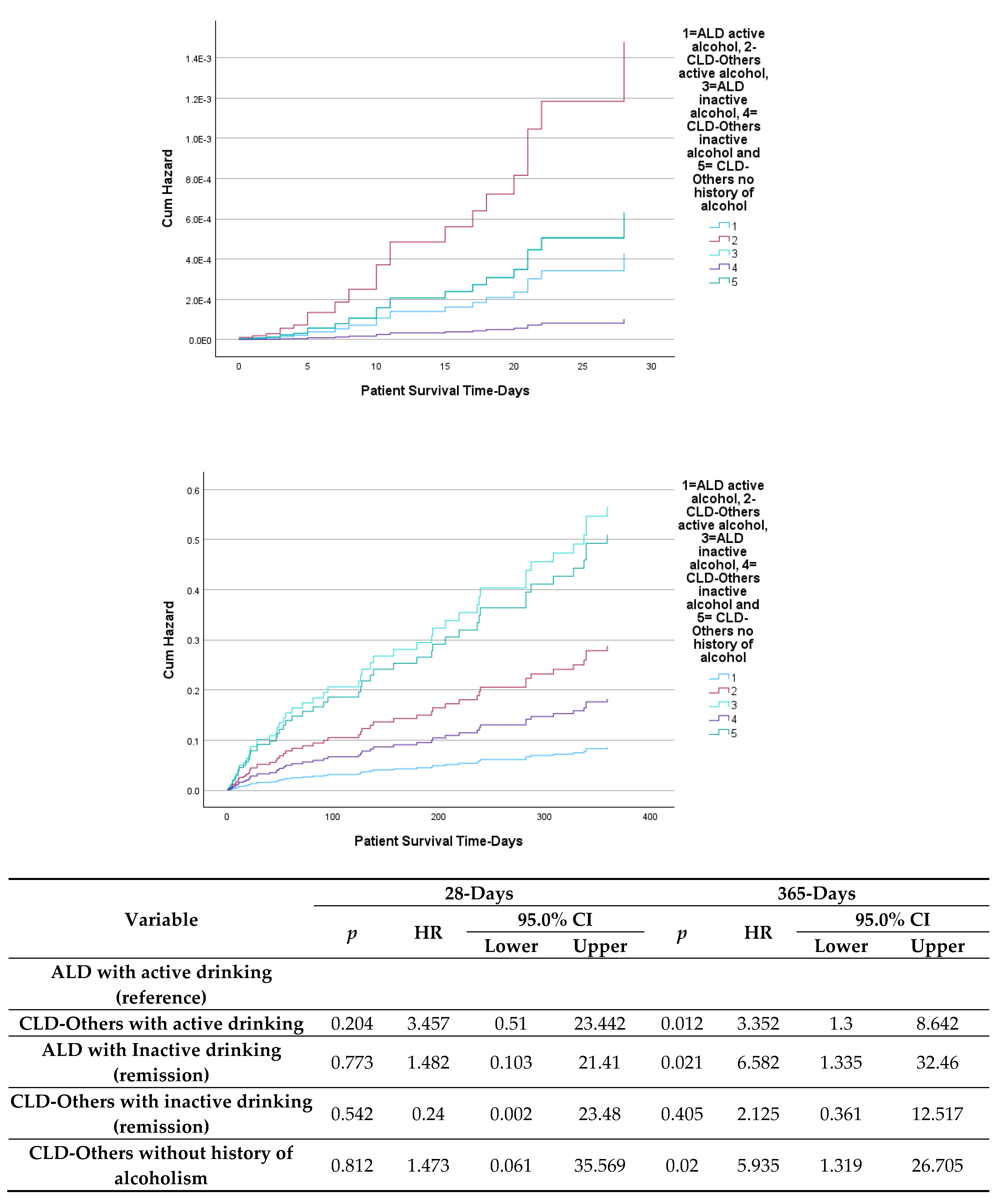

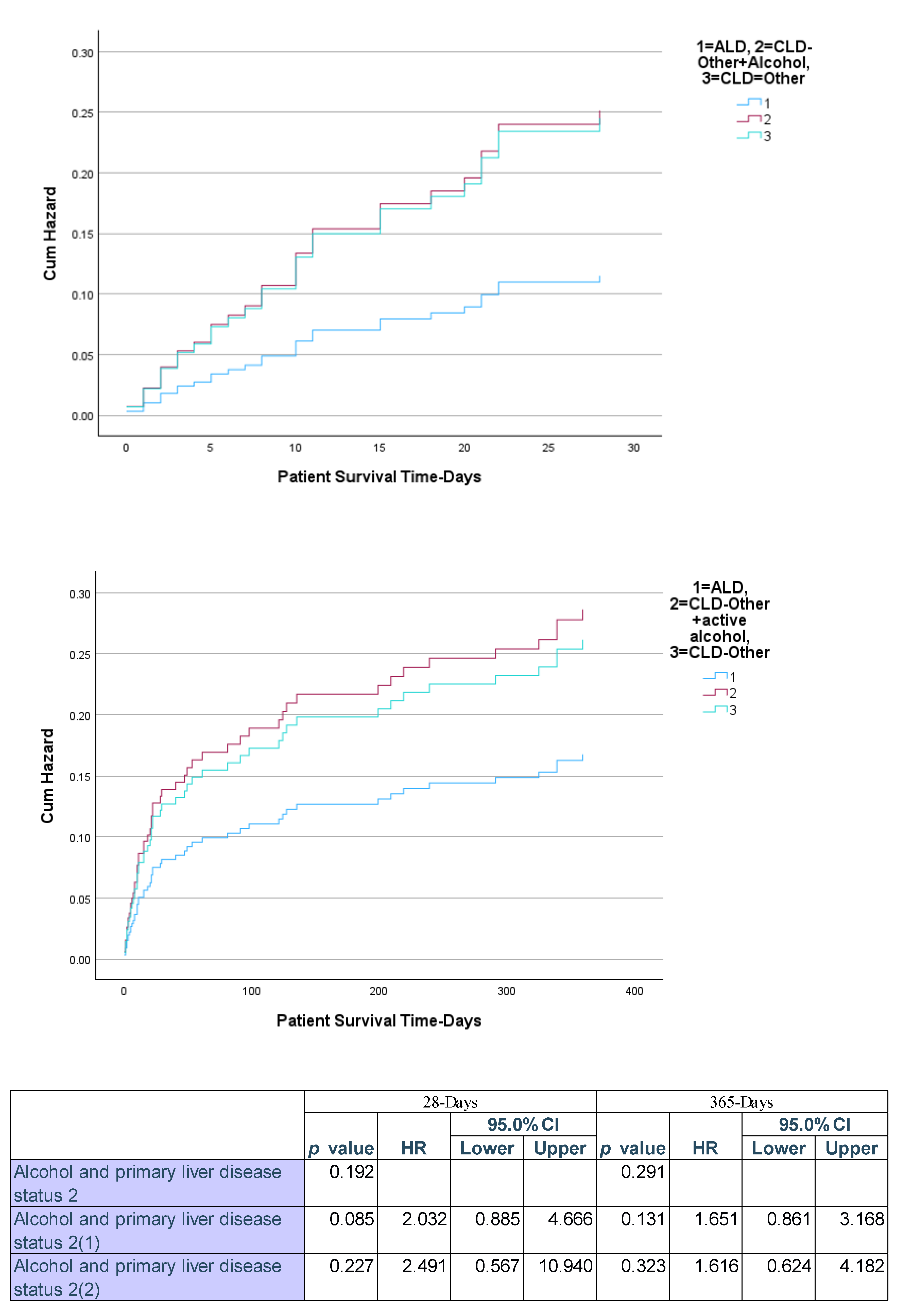

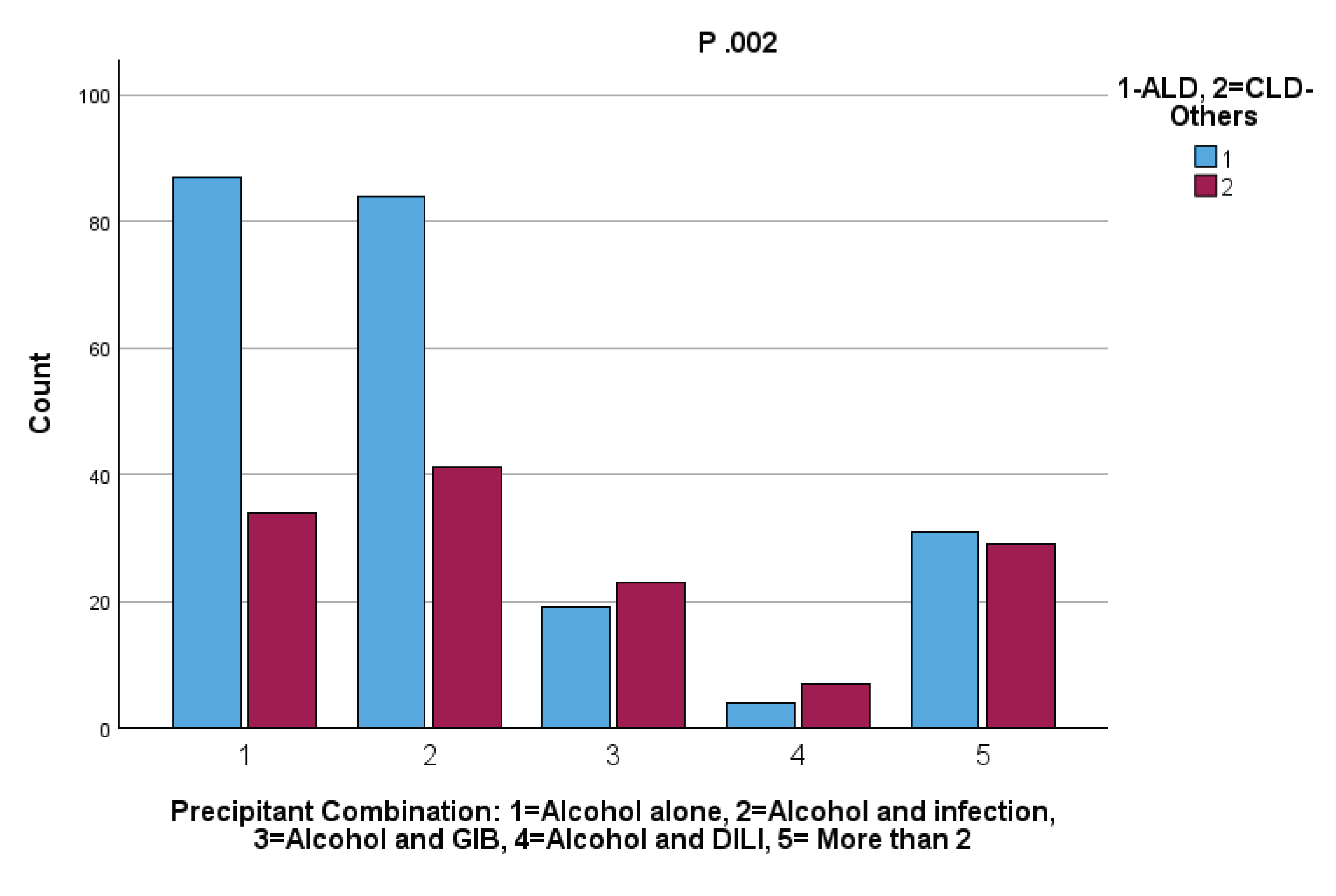

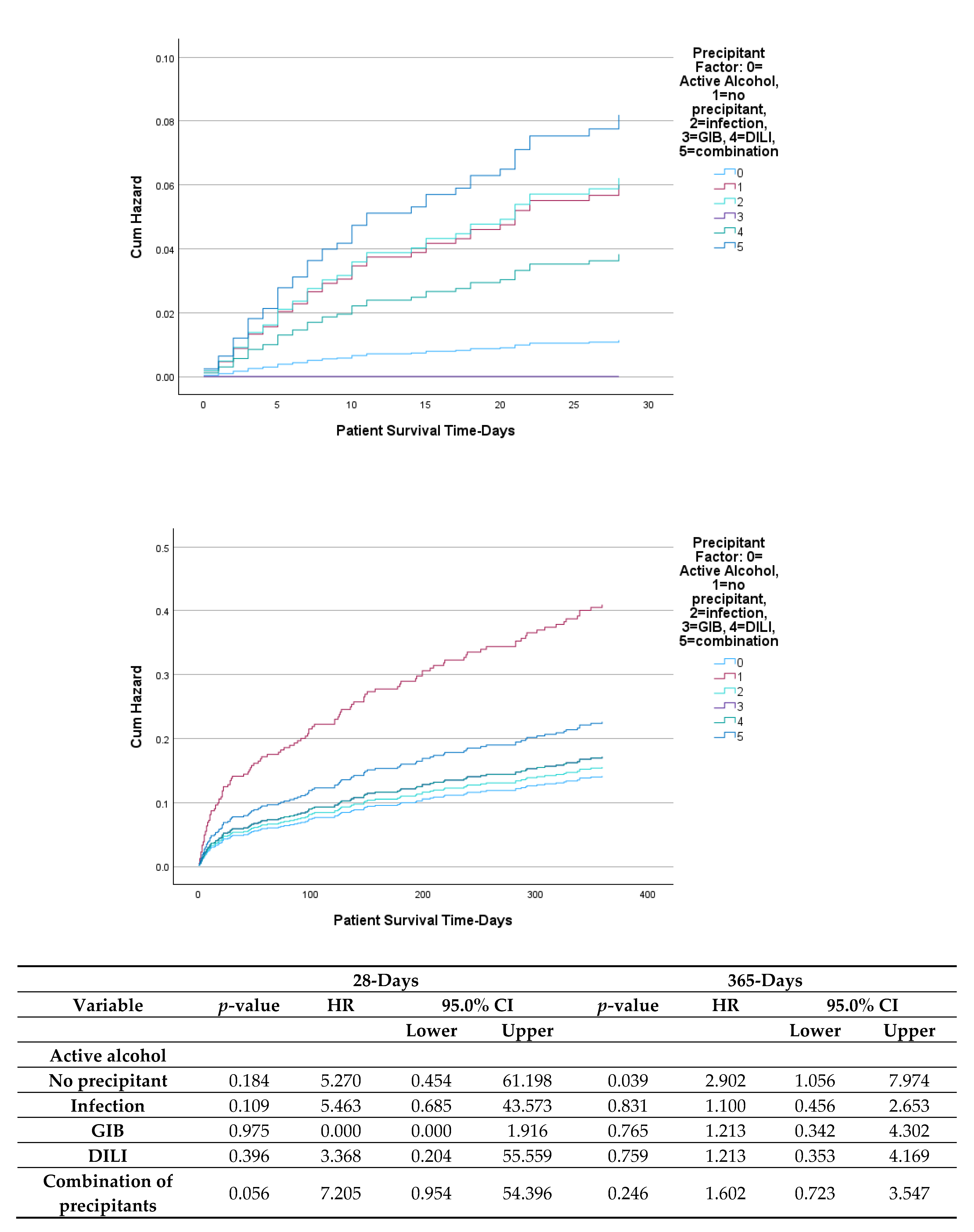

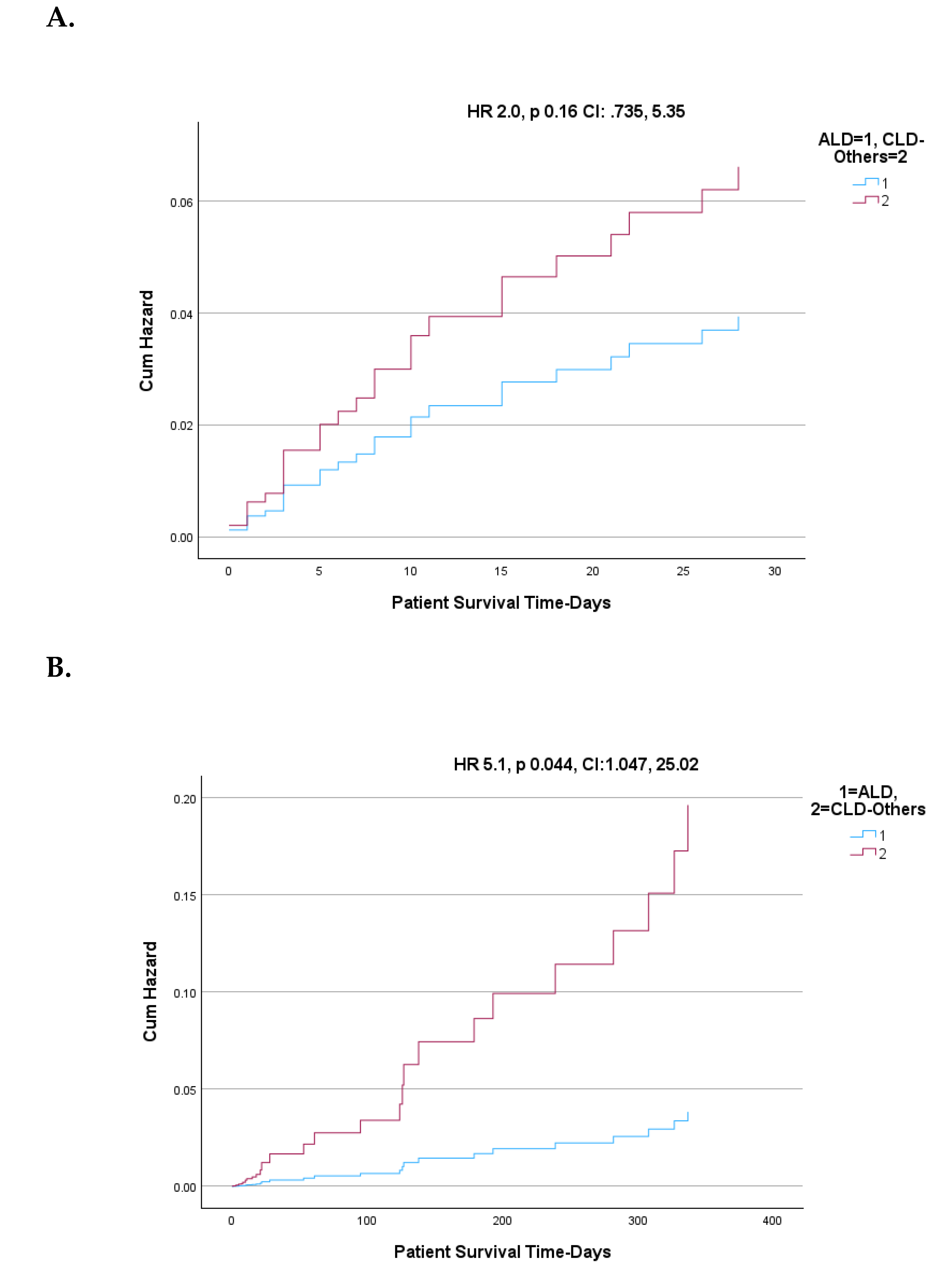

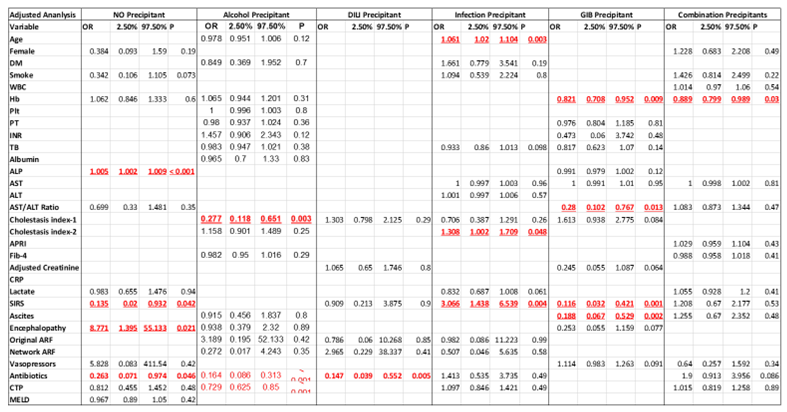

Background: Acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF) is characterized by acute deterioration in chronic liver disease (CLD), leading to organ failures. Alcohol is a major cause and trigger of ACLF, particularly in alcoholic liver disease (ALD). However, the impact of acute alcohol consumption in patients with non-alcoholic CLD (CLD-Others) is less well understood. Results: We retrospectively analyzed 623 ACLF patients, evaluating alcohol use as a sole in 19% or contributing precipitant in 39% among patients with primary CLD attributed to chronic alcohol use and those with CLD-other etiologies. Among drinkers, 225 had ALD and 134 had CLD-Others. Alcohol alone was identified as a precipitant in patients with CLD stemming from both alcoholic (ALD) and non-alcoholic etiologies (CLD-Others), and was associated with lower mortality rates at both 28 and 365 days compared to other precipitants. However, when stratified by underlying liver disease, the mortality risk associated with alcohol alone as a precipitant was significantly higher in patients with CLD-Others than in those with ALD and active alcohol use. Furthermore, when alcohol was present in conjunction with other precipitants, particularly gastrointestinal bleeding (GIB) and infections, the mortality risk was substantially elevated compared to alcohol alone, irrespective of the underlying etiology. Notably, the combination of alcohol and GIB was more frequently observed in patients with CLD-Others. Conclusions: Active alcohol use, alone or with other precipitants, increases short and long-term mortality in ACLF, with worse outcomes in CLD-Others than ALD. Distinguishing underlying liver disease etiology and precipitant patterns is vital for treatment and prognosis.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Significant increases in serum bilirubin and INR, indicative of severe liver dysfunction.

- Greater vulnerability to bacterial infections due to immune dysregulation.

- High incidence of renal failure, often requiring renal replacement therapy.

- Elevated need for intensive care and consideration for early liver transplantation.

2. Methodogy

2.1. Study Design and Patient Selection

2.2. Acute Precipitants

2.3. Ethical Considerations

2.4. Clinical and Laboratory Variables

2.5. Data Extraction Process:

2.6. Statistical Analysis:

|

3. Discussion

3.1. Alcohol as an Etiology and Precipitant of ACLF.

3.2. Precipitant Factors and Organ Failure Patterns

3.3. Mortality and Risk Stratification

4. Conclusions

| ACLF | Acute on Chronic Liver Failure |

| AD | Acute Decompensation |

| APASL | Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver |

| APRI | AST (Aspartate-amino Transferase) to Platelet Ratio Index |

| CRP | C-Reactive Protein |

| CT | Computed Tomography |

| CTP | Child-Turcott-Pugh |

| DILI | Drug-Induced Liver Disease |

| DM | Diabetes Mellitus |

| DDLT | Deceased Donor Liver Transplantation |

| EASL-CLIF | European Association for the Study of the Liver-Chronic Liver Failure Consortium |

| GI | Gastro-Intestinal |

| Hb | Hemoglobin |

| ICD | International Classification of Diseases |

| INR | International Normalized Ratio |

| IRB | Institutional Review Board |

| IT | Information Technology |

| LFT | Liver Function Tests |

| LT | Liver Transplantation |

| LDLT | Living Donor Liver Transplantation |

| MAFLD | Metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty Liver Disease |

| MASH | Metabolic dysfunction Associated Steatohepatitis |

| MCV | Mean Corpuscular Volume |

| MELD | Model for End Stage Liver Disease |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| NACSELD | North American Consortium for the Study of End-Stage Liver Disease |

| NASH | Non-Alcoholic Steatohepatitis |

| OF | Organ Failure |

| PLD | Primary Liver Disease |

| PT | Prothrombin Time |

| ROC | Receiver Operating Characteristic |

| SIRS | Systemic Immune Response Syndrome |

| SOFA | Sequential Organ Failure Assessment |

| TIPS | Transjugular Intrahepatic Portosystemic Shunt |

| UNOS | United Network of Organ Sharing |

| WBC | White Blood Cell |

Author’s Contributions

Financial support and sponsorship

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Arroyo V, Moreau R, Jalan R. Acute-on-chronic liver failure. N Engl J Med 2020; 382:2137–2145.

- Moreau R, Jalan R, Ginès P, Pavesi M, Angeli P, Cordoba J, et al. Acute-on chronic liver failure is a distinct syndrome that develops in patients with acute decompensation of cirrhosis. Gastroenterology 2013; 144:1426 1437.

- Bajaj JS, O’Leary JG, Reddy KR, Wong F, Biggins SW, Patton H, et al. Extrahepatic organ failures define survival in infection-related acute-on-chronic liver failure. Hepatology 2014; 60:250–256.

- Wu T, Li J, Shao L, Xin J, Jiang L, Zhou Q, et al., on behalf of the Chinese Group on the Study of Severe Hepatitis B (COSSH). Development of diagnostic criteria and a prognostic score for hepatitis B virus-related acute-on-chronic liver failure. Gut 2018; 67:2181–2191.

- Sarin SK, Choudhury A, Sharma MK, Maiwall R, Al Mahtab M, Rahman S, et al. Acute- on-chronic liver failure: consensus recommendations of the Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver (APASL): an update. Hepatol Int 2019; 13:353–390.

- Moreau R, Jalan R, Ginès P, Pavesi M, Angeli P, Cordoba J, et al. Acute-on chronic liver failure is a distinct syndrome that develops in patients with acute decompensation of cirrhosis. Gastroenterology 2013; 144:1426 1437.

- Avolio AW, Gaspari R, Teofili L, Bianco G, Spinazzola G, Soave PM, Paiano G, Francesconi AG, Arcangeli A, Nicolotti N, Antonelli M. Postoperative respiratory failure in liver transplantation: Risk factors and effect on prognosis. PLoS One. 2019;14(2): e0211678.

- Mattos ÂZ, Mattos AA. Letter to the Editor: Acute-on-Chronic Liver Failure: Conceptual Divergences. Hepatology. 2019 Sep;70(3):1076.

- Jalan R, Gines P, Olson JC, Mookerjee RP, Moreau R, Garcia-Tsao G, Arroyo V, Kamath PS. Acute-on chronic liver failure. J Hepatol. 2012; 57:1336–1348.

- Sarin SK, Kumar A, Almeida JA, Chawla YK, Fan ST, Garg H, de Silva HJ, Hamid SS, Jalan R, Komolmit P, et al. Acute-on-chronic liver failure: consensus recommendations of the Asian Pacific Association for studying the liver (APASL) Hepatol Int. 2009;3:269–282.

- Kim TY, Kim DJ. Acute-on-chronic liver failure. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2013; 19:349–359.

- Moreau R, Jalan R, Gines P, Pavesi M, Angeli P, Cordoba J, Durand F, Gustot T, Saliba F, Domenicali M, Gerbes A, Wendon J, Alessandria C, Laleman W, Zeuzem S, Trebicka J, Bernardi M, Arroyo V; CANONIC Study Investigators of the EASL-CLIF Consortium. Acute-on-chronic liver failure is a distinct syndrome that develops in patients with acute decompensation of cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 2013; 144: 1426–1437, 1437. [Google Scholar]

- Bajaj JS, Reddy KR, Tandon P, et al. Prediction of fungal infection development and their impact on survival using the NACSELD cohort. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113(4):556– 563.

- Mahmud N, Fricker Z, Hubbard RA, et al. Novel risk prediction models for post-operative mortality in patients with cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2020;73(1):204–218.

- Berres ML, Lehmann J, Jansen C, et al. Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 11 levels predict survival in cirrhotic patients with transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt. Liver Int. 2016; 36:386–392.

- Berres ML, Asmacher S, Lehmann J, et al. CXCL9 is a prognostic marker in patients with liver cirrhosis receiving transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt. J Hepatol. 2015; 62:332–339.

- Canbay A, et al. Overweight patients are more susceptible for acute liver failure. Hepatogastroenterology. 2005; 52:1516–1520.

- Choudhury A, Jindal A, Maiwall R, et al. Liver failure determines the outcome in patients of acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF): Comparison of APASL ACLF research consortium (AARC) and CLIF SOFA models. Hepatol Int. 2017; 11:461–471.

- Gustot T, Jalan R. Acute-on-chronic liver failure in patients with alcohol-related liver disease. J Hepatol. 2019; 70:319–327.

- Singal AK, Bataller R, Ahn J, et al. ACG clinical guideline: Alcoholic liver disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018; 113:175–194.

- Crabb DW, Im GY, Szabo G, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of alcohol-associated liver diseases: 2019 practice guidance from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology. 2020; 71:306–333.

- Idalsoaga F, Díaz LA, Fuentes-López E, et al. Active alcohol consumption is associated with acute-on-chronic liver failure in Hispanic patients. Gastroenterol Hepatol (Engl Ed). 2024;47(6):562–573.

- Garad, N. To elucidate precipitating factors, clinical profile and outcome of acute-on- chronic liver failure in cirrhotic patients. Br J Med Health Res. 2020;7(12):1–8.

- Narayanasamy, K. Prevalence of acute on chronic liver failure, underlying etiology and precipitating factors. Int Arch Integr Med. 2019;6(4).

- Katoonizadeh A, Laleman W, Verslype C, et al. Early features of acute-on-chronic alcoholic liver failure: a prospective cohort study. Gut. 2010;59(11):1561–1569.

- Wang T, Tan W, Wang X, et al. Role of precipitants in transition of acute decompensation to acute-on-chronic liver failure in patients with HBV-related cirrhosis. JHEP Rep. 1: 2022;4(10), 2022.

| Primary diagnosis | |

| EtOH | 284 (45.58%) |

| Hep C | 209 (33.54%) |

| Hep B | 12 (1.92%) |

| SH | 51 (8.18%) |

| AIH | 10 (1.58%) |

| Other | 1 (0.01%) |

| Unknown | 56 (8.89%) |

| Age (mean +/-SD) | 53.35±11.681 |

| Female | 215 (34.51%) |

| Current/former alcohol use | 452 (74.34%) |

| Hepato-toxins intake before admission | 116 (18.61%) |

| Use of supplements and herbs | 59 (9.47%) |

| Use of antimicrobials | 50 (8.02%) |

| Use of other toxins | 7 (1.12%) |

| Current/former smoker | 236 (37.88%) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 170 (27.28%) |

| WBC (mean +/-SD) | 9.43±6.39 |

| Hb | 11.49±2.87 |

| Platelet (mean +/-SD) | 132.72±94.57 |

| Prothrombin time (mean +/-SD) | 24.15±31.93 |

| Creatinine (mean +/-SD) | 1.49±1.57 |

| Creatinine status | |

| <1.5 | 461 (74.12%) |

| 1.5-2.0 | 53 (8.52%) |

| >2.0 | 108 (17.36%) |

| INR (mean +/-SD) | 1.91±2.37 |

| INR >1.7 | 143 (22.29%) |

| Total bilirubin | 7.41±18.42 |

| Albumin | 3.37±10.23 |

| Albumin <3.5 | 475 (76.24%) |

| ALP | 162.11±125.91 |

| AST | 166.40±511.64 |

| ALT | 84.05±209.88 |

| AST/ALT ratio | 2.28±1.91 |

| Cholestasis index-1 (AST*UNL/AP*UNL) (mean +/-SD) | 0.90±0.83 |

| Cholestasis index-2 (ALT*UNL/AP*UNL) (mean +/-SD) | 1.76±1.76 |

| APRI | 5.94±23.61 |

| Fib-4 | 11.75±26.07 |

| Lactate | 3.39±2.94 |

| SIRS criteria met (n=455) | 189 (41.53%) |

| Ascites | 255 (40.93%) |

| Encephalopathy | 143 (22.95%) |

| TIPS | 54 (8.70%) |

| CTP score (mean +/-SD) | 10.71±2.22 |

| MELD (mean +/-SD) | 16.94±11.41 |

| MELD >21 | 175 (28.14%) |

| Infection identified | 343 (55.32%) |

| Infection type | |

| Unknown status | 85 |

| No | 197 (36.62%) |

| UTI | 71 (13.20%) |

| Pneumonia | 51 (9.48%) |

| Sepsis | 25 (4.65%) |

| SBP | 15 (2.79%) |

| Other | 179 (33.27%) |

| GIB | 155 (26.05%) |

| Precipitant Factor -defined | |

| None | 48 (7.70%) |

| Active alcohol | 120 (19.26%) |

| Infection | 96 (15.41%) |

| GIB | 34 (5.46%) |

| DILI | 15 (2.41%) |

| Combination | 310 (49.76%) |

| Hemodialysis | 30 (5.03%) |

| ACLF definition by criteria | |

| ACLF-APASL | 97 (15.56%) |

| ACLF-NACSLED | 135 (21.66%) |

| ACLF-EASL (>=2 organ failures) | 135 (21.66%) |

| ACLF-EASL (one organ failure and Cr 1.5-1.9) | 184 (29.53%) |

| MELD >21 | 175 (28.09%) |

| Organ failures-(missing info n=80; excluded) | |

| Liver failure-APASL | 139 (22.35%) |

| Kidney failure-APASL | 161 (25.88%) |

| Liver failure-EASL | 76 (12.22%) |

| Kidney failure-EASL | 106 (17.04%) |

| Brain failure-EASL | 143 (23.25%) |

| Circulatory failure-EASL | 67 (11.22%) |

| Coagulation failure-EASL | 62 (9.95%) |

| Respiratory failure-EASL | 94 (15.09%) |

| Total # of organ failures-EASL | |

| 0 | 246 (45.30%) |

| 1 | 162 (29.83%) |

| 2 | 83 (15.29%) |

| 3 | 37 (6.81%) |

| 4 | 8 (1.47%) |

| 5 | 5 (0.92%) |

| 6 | 2 (0.37%) |

| >= 3 | 52 (9.58%) |

| Length of hospital stay | 7.77±8.77 |

| Discharge condition | |

| Alive | 555 (89.37%) |

| Dead | 63 (10.14%) |

| Transplanted | 3 (0.48%) |

| Variable | None (N = 48) |

Active alcohol (N = 120) | Infection (N = 96) | GIB (N = 34) |

DILI (N = 15) |

Combination (N = 310) | p-value1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MELD>=21 | 11 (22.92%) | 30 (25.00%) | 32 (33.33%) | 1 (2.94%) | 5 (33.33%) | 96 (31.07%) |

0.012 |

| APASL | 4 (8.51%) | 18 (15.25%) | 13 (13.83%) | 0 (0.00%) | 2 (13.33%) | 60 (19.87%) |

0.031 |

| EASL-CLIF | 0 (0.00%) | 0 (0.00%) | 2 (2.08%) |

0 (0.00%) | 0 (0.00%) | 182 (79.13%) |

<0.001 |

| NACSELD | 4 (9.09%) | 20 (21.98%) | 27 (32.93%) | 0 (0.00%) | 1 (7.69%) | 83 (29.75%) |

<0.001 |

| EASL 2 organ failures | 0 (0.00%) | 0 (0.00%) | 0 (0.00%) |

0 (0.00%) | 0 (0.00%) | 135 (58.70%) |

<0.001 |

|

| Variable |

None (N = 48) |

Active alcohol (N = 120) | Infection (N = 96) |

GIB (N = 34) |

DILI (N = 15) |

Combination (N = 310) | p-value1 |

| Primary liver disease | <0.001 | ||||||

| Alcohol | 13 (27.08%) | 87 (72.50%) | 19 (20.21%) | 5 (16.13%) | 2 (13.33%) | 155 (50.49%) |

|

| Viral | 20 (41.67%) | 27 (22.50%) | 43 (45.74%) | 17 (54.84%) | 7 (46.67%) | 107 (34.85%) |

|

| SH | 6 (12.50%) | 3 (2.50%) |

13 (13.83%) | 4 (12.90%) | 1 (6.67%) | 24 (7.82%) |

|

| Other | 9 (18.75%) | 3 (2.50%) |

19 (20.21%) | 5 (16.13%) | 5 (33.33%) | 21 (6.84%) |

| Variables | Active Alcohol Users | ||||

| ALD | CLD-Others | ||||

| N | % or mean | N | % or mean | P value | |

| Female | 83 | 36.9% | 40 | 29.9% | NS |

| DM | 31 | 13.8% | 34 | 25.4% | 0.007 |

| Smokers | 55 | 51.9% | 68 | 68.0% | 0.02 |

| SIRS | 51 | 47.2% | 39 | 38.6% | NS |

| INR >=1.7 | 49 | 45.4% | 29 | 28.7% | 0.015 |

| Ascites | 92 | 40.9% | 53 | 40.2% | NS |

| HE None | 23 | 10.3% | 0 | 0.0% | NS |

| HE Grade 1-2 | 162 | 72.3% | 100 | 76.3% | NS |

| HE Grade 3-4 | 39 | 17.4% | 31 | 23.7% | NS |

| MELD >=15 | 111 | 49.3% | 62 | 46.3% | NS |

| Infection | 113 | 50.2% | 68 | 51.5% | NS |

| DILI | 17 | 15.7% | 21 | 20.8% | NS |

| GIB | 45 | 22.4% | 46 | 34.6% | 0.017 |

| MELD >=21 | 72 | 32.0% | 30 | 22.6% | 0.05 |

| NACSELD ACLF | 51 | 27.6% | 29 | 23.6% | NS |

| EASL-CLIF ACLF | 70 | 31.1% | 38 | 28.6% | NS |

| Age | 225 | 48.97 | 133 | 52.5 | 0.004 |

| WBC-1 | 225 | 10.3633 | 133 | 9.113 | NS |

| Hb | 224 | 11.587 | 134 | 11.61 | NS |

| Plt | 225 | 151.768 | 134 | 123.146 | 0.012 |

| PT | 206 | 26.455 | 126 | 26.087 | NS |

| INR-1 | 225 | 2.265 | 134 | 1.947 | NS |

| TB: Total bilirubin | 225 | 11.671 | 133 | 7.838 | NS |

| Albumin | 210 | 3.62 | 127 | 4.272 | NS |

| ALP: Alkaline phosphatase | 216 | 161.51 | 129 | 150.84 | NS |

| AST: Aspartate amino transferase | 225 | 231.04 | 134 | 221.1 | NS |

| ALT: Alamine amino transferase | 225 | 101.96 | 134 | 120.64 | NS |

| AST/ALT Ratio | 225 | 2.728819 | 134 | 2.191896 | 0.028 |

| Cholestasis index-1 | 225 | 0.601507 | 134 | 0.718054 | NS |

| Cholestasis Index-2 | 225 | 1.511861 | 134 | 1.439278 | NS |

| New Index | 225 | 4.94506 | 134 | 3.248123 | NS |

| APRI: AST/Platelet ratio index | 225 | 8.004345 | 134 | 6.202302 | NS |

| Fib-4 | 225 | 13.80806 | 134 | 11.13231 | NS |

| Creatinine-adjusted with hemodialysis status | 225 | 1.437 | 133 | 1.331 | NS |

| Creatinine unadjusted | 225 | 1.39 | 133 | 1.286 | NS |

| CRP level | 20 | 8.25 | 7 | 20.2714 | NS |

| Lactate-1 | 91 | 4.3675 | 72 | 3.7194 | NS |

| MELD Score | 225 | 18.35869 | 133 | 15.99158 | NS |

| LOS: length of stay in hospital | 224 | 7.66 | 133 | 7.86 | NS |

| Univariable | Multivariable | |||||||

| Variable | p value | HR | 95% C.I | p value | HR | 95% CI | ||

| Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | |||||

| Age | 0.004 | 1.030 | 1.009 | 1.051 | ||||

| DM | 0.006 | 2.128 | 1.236 | 3.663 | 0.042 | 2.055 | 1.025 | 4.121 |

| WBC | 0.081 | 0.969 | 0.935 | 1.004 | ||||

| Platelet | 0.013 | 0.997 | 0.995 | 0.999 | ||||

| AST/ALT Ratio | 0.027 | 0.845 | 0.729 | 0.981 | 0.008 | 0.733 | 0.583 | 0.922 |

| Cholestasis index | 0.063 | 1.427 | 0.980 | 2.076 | ||||

| MELD Score | 0.091 | 0.985 | 0.967 | 1.002 | ||||

| CTP Score | 0.003 | 1.151 | 1.049 | 1.264 | ||||

| Smoking | 0.019 | 1.970 | 1.117 | 3.475 | 0.011 | 2.159 | 1.189 | 3.922 |

| INR >= 1.7 | 0.013 | 0.485 | 0.273 | 0.861 | ||||

| GIB | 0.015 | 1.833 | 1.126 | 2.984 | ||||

| Bilirubin status Total bilirubin ≥5 mg/dL | 0.087 | 0.677 | 0.432 | 1.059 | ||||

| MELD-21 | 0.057 | 0.619 | 0.378 | 1.014 | ||||

| EASL Liver Failure | 0.028 | 0.504 | 0.273 | 0.930 | ||||

| Variables | 28-Days | 365-Days | ||||||

| p value | HR | 95.0% CI | p value | HR | 95.0% CI for Exp(B) | |||

| Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | |||||

| Age | 0.000 | 1.113 | 1.058 | 1.170 | 0.000 | 1.069 | 1.033 | 1.107 |

| CTP Score | 0.000 | 2.186 | 1.517 | 3.149 | 0.000 | 1.553 | 1.231 | 1.960 |

| MELD score | 0.001 | 1.088 | 1.037 | 1.142 | ||||

| GIB | 0.000 | 5.595 | 2.305 | 13.578 | 0.000 | 2.989 | 1.695 | 5.272 |

| Infections | 0.026 | 2.972 | 1.140 | 7.749 | ||||

| Albumin | 0.005 | 0.461 | 0.268 | 0.795 | ||||

| Cholestasis index | 0.001 | 3.511 | 1.719 | 7.172 | ||||

| INR >= 1.7 | 0.032 | 3.591 | 1.116 | 11.556 | 0.026 | 2.005 | 1.089 | 3.692 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).