Introduction

Infertility is defined as a condition in which a couple is unable to achieve a clinical pregnancy after 12 months of regularly performing unprotected sexual intercourse [

1]. This problem concerns women as well as men [

2]. As scale continues to grow and has reached a global dimension, there is still a pressing need for new, well-designed scientific studies in this field. According to estimates, infertility affects as many as 48 million couples worldwide [

3], with the highest prevalence of infertility observed in East and South Asia, as well as in Eastern Europe [

4]. Certain forecasts predict a further increase in the number of people struggling with infertility, as well as a growing need to improve the effectiveness of treatment [

5], which indicates the importance of conducting further research in this area.

Many methods of infertility treatment exist, which are individually catered to the patient’s—or couple’s—needs, based on the diagnosed underlying cause [

6]. The treatment protocol should include those methods that offer the greatest chances of achieving pregnancy and giving birth to a healthy child. Infertility treatment mainly relies on pharmacotherapy, surgical treatment, and assisted reproductive technologies (ART) [

7]. In situations where causal treatment is not recommended or proves ineffective, the use of ART can increase the chances of a positive outcome, i.e., achieving pregnancy and giving birth to a child [

7]. The last few decades have seen dynamic development in ART, which has enabled effective treatment of cases previously considered incurable [

8].

Despite the aforementioned advancements, it is agreed that the effectiveness of ART could be higher. An important step in improving treatment effectiveness is the accurate prediction of reproductive outcomes. In this respect, determining the developmental potential of embryos would allow for a more precise selection of the embryo for transfer, thus increasing the chances of success. Additionally, a faster transfer—on days 2 or 3, instead of waiting until days 5 or 6 to assess blastocyst quality—would shorten the in vitro culture period and thus reduce treatment costs. Several models have been developed specifically for assessing the developmental potential of embryos in the IVF process. Some of them were morphokinetic models [

9,

10,

11], which yielded predictors with an AUC of around 0.7 [

12,

13] for predicting biochemical pregnancy, clinical pregnancy, or live birth. A higher AUC of around 0.8 [

14] was achieved by models that predicted development to the blastocyst stage.

Aspects involving the endometrium—its receptivity, readiness to accept the developing embryo, and ability to provide an optimal environment for its development—are significantly less studied. Despite this fact, it should be emphasized that researchers focusing on predicting treatment effectiveness based on embryo quality assessment, for example through morphokinetic evaluation, often indicate that endometrial receptivity is a complementary area of research that needs to be studied in order increase the accuracy of prediction of reproductive success with greater accuracy. One of such directions proposed in the literature is the assessment of endometrial compaction (EC) [

15,

16]. The approach consists of evaluating changes in endometrial thickness between the ovulation peak and the day of embryo transfer as an indicator that the endometrium has compacted, i.e., it has become receptive and conducive to implantation—with the authors concluding that endometrial compaction significantly increases the chances of implantation [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20]. Other findings, however, do not support this conclusion [

21,

22,

23,

24,

25]. One possible explanation for the discrepancies is that a single measurement of endometrial thickness appears to lack sufficient precision—both due to the different techniques and the choice of measurement site, as well as the nature of processes occurring in the endometrium, which affect its shape, between the two time points mentioned above [

26].

A key aspect of the published research that may be crucial in the context of using changes in endometrial thickness for predictive purposes is the fact that authors of previous studies do not in fact specify how endometrial thickness was measured. This omission makes it likely that differing methods, measurement sites, or other additional factors could have been used—potentially leading to varying results. This lack of both methodological clarity and, most probably, homogeneity may explain why certain studies showed significant findings while others did not. This particular inconsistency has led the authors of the present study towards the idea of proposing a more detailed assessment of endometrial shape—based on a greater number of parameters compared to a single, vaguely defined, “endometrial thickness” measurement—as well as an evaluation of changes occurring between the ovulation peak and the day of embryo transfer. In this context, it is worth mentioning that some studies indicate that 3D measurement of the endometrium may provide more precise results [

27], owing to its ability to reflect more complex processes undergone by the endometrium. Based on the approach outlined above, the authors planned to develop a completely novel predictor of embryo implantation (IMP), based on the dynamics of endometrial changes. The term ‘dynamics’ as used in this article denotes changes in endometrial thickness occurring between the two aforementioned time points, assessed by measuring several parameters, which

de facto describe the shape of the endometrium. The term ‘biochemical pregnancy’ in this article is used to refer to the fact of embryo implantation in the endometrium.

Hence, the aim of the present study is to assess the extent to which information related solely to endometrial receptivity—specifically, the dynamics of compaction—can predict reproductive success.

If high predictive accuracy of the approach is confirmed, further research will be conducted, based on the results of this study, aimed at integrating the developed model with morphokinetic data, describing embryo developmental potential, as well as the woman’s age, and other clinically significant variables. The aim would be to create a highly functional model with predictive power exceeding that of all currently available models used to predict the success of infertility treatment via IVF.

Materials and Methods

The study was conducted in 2025 using data obtained from couples treated for infertility at the Kriobank Clinic (Białystok, Poland) between December 2021 and February 2025. Data from 61 couples were analyzed, including 27 couples who achieved biochemical pregnancy and 34 who did not. Each woman underwent two ultrasound examinations of the uterine endometrium: one at the time of the ovulation peak and the other on the day of embryo transfer into the uterine cavity. The following parameters were measured on each of the two ultrasound images:

- l1 – uterine length, measured between the highest point of the uterine fundus and the cervical opening,

- w1 – width at the widest point of the endometrial outline,

- l2 – distance measured along the junction defined during the l1 measurement, limited to the segment between the highest point of the uterine fundus and the intersection with the w1 measurement,

- w2, w3, w4 – subsequent widths of the endometrial outline, measured along segments parallel to the w1 measurement and equidistant from each other by l2, continuing towards the cervical opening.

Of course, due to the diverse possible shapes of the endometrium, it would sometimes be possible to measure additional widths (w5, ...). However, in the process of building the predictive model, the aforementioned set of parameters was used, as it could be determined for all the analyzed cases.

To determine the parameters describing endometrial compaction, the above measurements were taken at two time points:

- at the time of the ovulation peak (parameters l1_1, l2_1, w1_1, w2_1, w3_1, and w4_1),

- at the time of embryo transfer into the uterine cavity (parameters l1_2, l2_2, w1_2, w2_2, w3_2, and w4_2).

When determining the extent of variation in the four consecutive measurements of endometrial width (w1-w4), a larger spread in the values of these parameters may indicate that endometrial compaction occurred only in a portion of the endometrial area, e.g., only around the cervical region. The differences and ratios between the smallest and largest widths were calculated. It should be noted that the difference and the ratio do not convey the same information: the difference provides information only the absolute change in the parameter value, while the ratio, on the other hand, refers to the relative change relative to the baseline value:

- max-min=max(w1, w2, w3, w4)–min(w1, w2, w3, w4)

- min_to_max=min(w1, w2, w3, w4)/max(w1, w2, w3, w4)

Thus, the following parameters for the measurements at the time of the ovulation peak were created:

- max-min_1 and min_to_max_1,

while for the measurements at the time of embryo transfer into the uterine cavity, the following parameters were created:

- max-min_2 and min_to_max_2.

To normalize the obtained measurements according to different uterine lengths (parameter l1), the ratios of the remaining parameters were calculated in relation to the l1 value, resulting in the following ratios:

- l2n_1=l2_1/l1_1; w1n_1=w1_1/l1_1; w2n_1=w2_1/l1_1; w3n_1=w3_1/l1_1; w4n_1=w4_1/l1_1 (for the measurements at the time of the ovulation peak),

and:

- l2n_2=l2_2/l1_2; w1n_2=w1_2/l1_2; w2n_2=w2_2/l1_2; w3n_2=w3_2/l1_2; w4n_2=w4_2/l1_2 (for the measurements at the time of embryo transfer into the uterine cavity).

The above parameters refer to the static assessment of the endometrial shape at the specified times. The following ratios of analogous parameters at both time points were also calculated:

- prop_l1=l1_1/l1_2; prop_l2=l2_1/l2_2; prop_w1=w1_1/w1_2; prop_w2=w2_1/w2_2; prop_w3=w3_1/w3_2; prop_w4=w4_1/w4_2,

- prop_l2n=l2n_1/l2n_2; prop_w1n=w1n_1/w1n_2; prop_w2n=w2n_1/w2n_2; prop_w3n=w3n_1/w3n_2; prop_w4n=w4n_1/w4n_2,

-prop_max-min=max-min_1/max-min_2; prop_min_to_max=min_to_max_1/min_to_max_2.

Figure 1 shows an example ultrasound image of the endometrium with the measurement sites described above.

The presence of biochemical pregnancy, indicating embryo implantation in the endometrium, was adopted as the modeled dependent variable. For this variable, a univariate logistic regression analysis was performed, with all the measured endometrial dimensions at both time points, as well as the differences and ratios of the corresponding parameters, used as independent variables. A multivariable logistic regression model was then created. The goodness of fit of the model was assessed using the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test after logistic modeling. Based on this model, a predictor of the occurrence of biochemical pregnancy was proposed (IMP). An ROC analysis was performed for the created IMP predictor, with the area under the curve (AUC) being determined. Finally, the Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare the values of the IMP predictor between the pregnancy and no pregnancy groups. The IMP predictor values were also divided into four quartile ranges based on the median and quartiles, and the strength of the relationship between these intervals and the percentage of recorded pregnancies in each of them was assessed using Pearson’s Chi-square test of independence.

The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to assess the normality of the distribution of variables. Normality was not observed for the analyzed numerical parameters. Statistically significant results were considered at the level of p<0.05. The Statistica 13.3 package (TIBCO Software Inc., San Ramon, CA 94583, USA) was used for data analysis, while modeling was performed using Stata 18.5 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX 77845, USA).

Results

The basic descriptive statistics for the analyzed parameters, divided into the pregnancy and no pregnancy groups, are presented in

Table 1.

None of the listed parameters showed statistically significant differences when compared between the pregnancy and no pregnancy groups.

Table 2 presents the results of the univariate logistic regression analysis conducted for all parameters describing endometrial dimensions at both time points, as well as for the calculated ratios, in relation to the dependent variable indicating the occurrence of implantation.

Table 3 presents the created multivariable logistic regression model, based on which the following predictor was proposed:

IMP = 85.34801∙l2n_1 + 42.5543∙w1n_1 + 21.13383∙w2n_1 + 31.95039∙w3n_1

- 89.38451∙w4n_1 – 6.920371∙max-min_1 + 10.13391∙min_to_max_1

- 126.2781∙l2n_2 – 7.97039∙w2n_2 – 4.659379∙prop_w1 – 20.73344∙prop_l2n

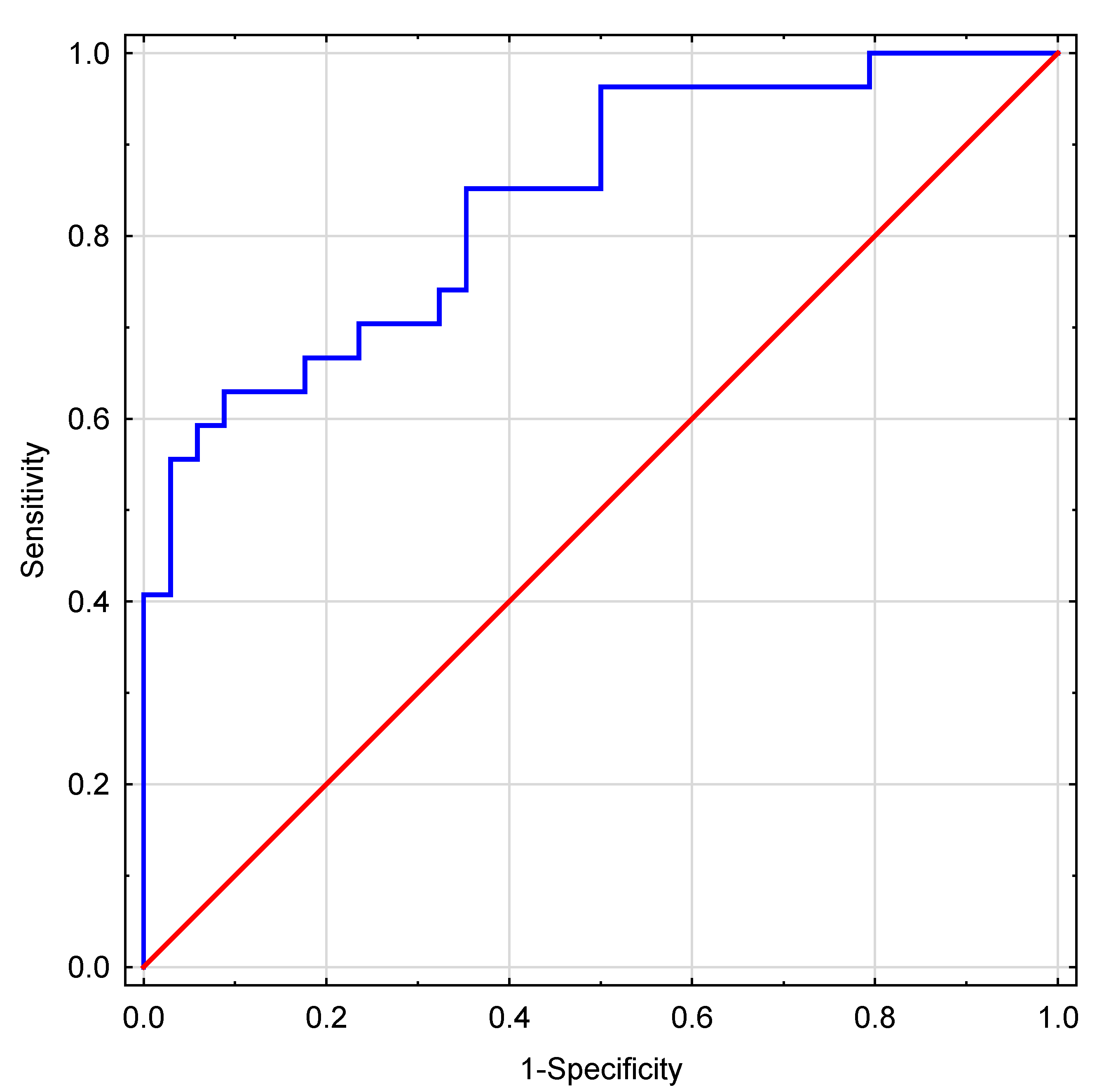

A high goodness of fit was confirmed for the model using the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test after logistic model at p=0.41. The ROC analysis conducted for the proposed IMP predictor yielded an area under the ROC curve (AUC) value of 0.839 (95% CI: 0.739; 0.938). The ROC curve is shown in

Figure 2.

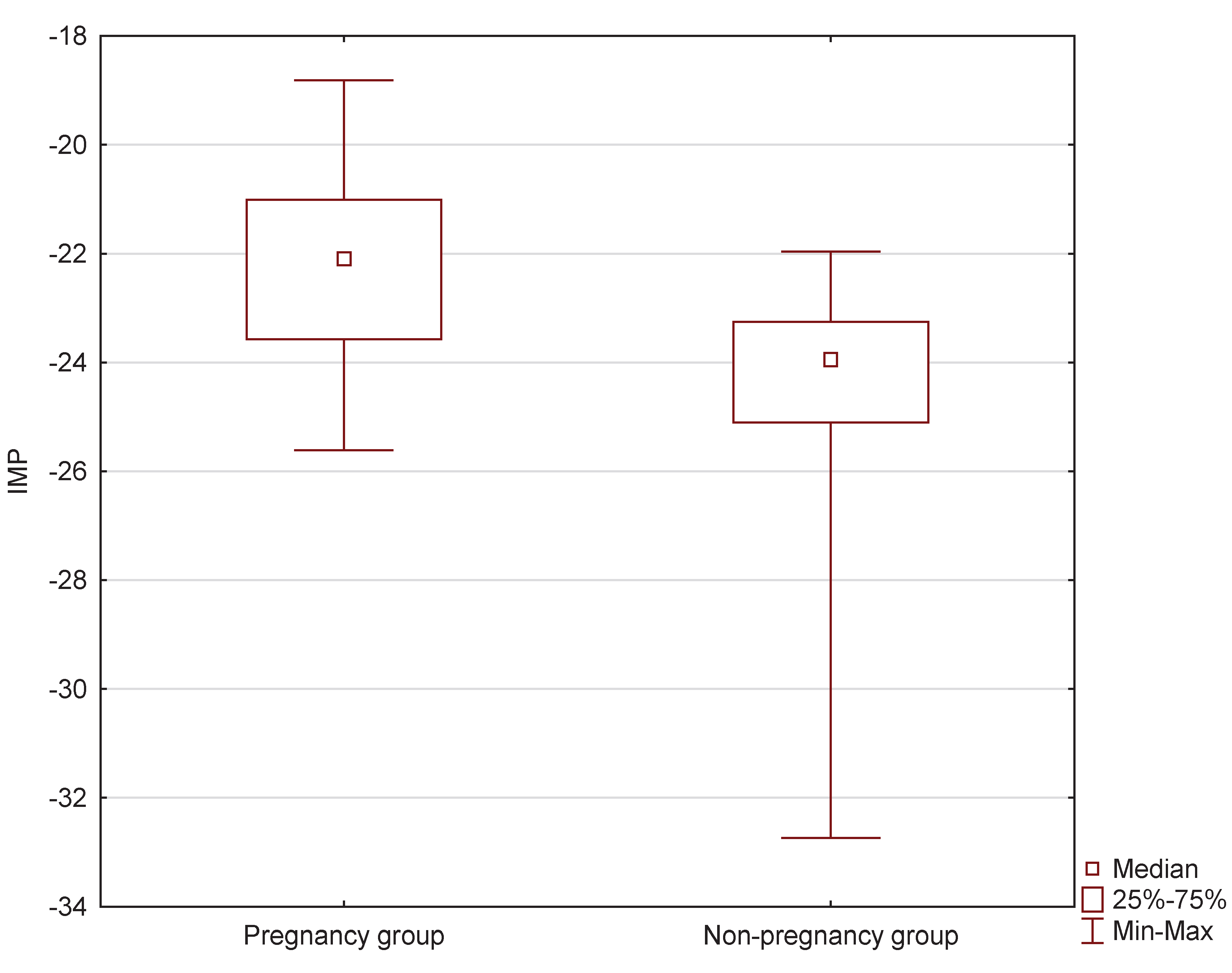

Statistically significant differences in the sizes of the created IMP predictor were observed between the pregnancy and no pregnancy groups at the level of p<0.0001 (

Figure 3). The median value of the IMP predictor in the pregnancy group was Me=-22.0972 (Q

1=-23.5695; Q

3=-21.0082), while in the no pregnancy group, it was significantly lower, with Me=-23.9482 (Q

1=-25.1003; Q

3=-23.2514).

Finally, the values of the IMP predictor were divided into four quartile ranges based on the values of the median and quartiles (Me=-23.3589; Q

1=-24.5274; Q

3=-22.1521). Statistically significant relationship (p<0.0001) between the individual ranges and the percentage of recorded implantations was found. The obtained percentages of biochemical pregnancies in the different ranges are presented in

Table 4. Special attention should be paid to the extreme ranges: in the first range, 15 out of 16 cases did not result in pregnancy, while in the last range, 14 out of 15 cases resulted in pregnancy.

Discussion

The topic of assessing EC in the context of the endometrium’s ability to accept the ovum—or endometrial receptiveness—was proposed fairly recently by Casper et al., in their studies published in 2019 [15] and 2020 [16], where they assess endometrial thickness at the following two time points: around the ovulatory peak—defined as the end of the estrogen phase—and the day of transfer. The principle is that the shrinkage/compaction of the endometrium between these time points is supposed to suggest better preparation of the endometrium for embryo implantation. In the follicular phase, i.e., before ovulation, estrogen causes the endometrium to grow rapidly as glands and vessels proliferate, and the lining becomes thick. After ovulation, progesterone levels increase, which stops further thickening, but the glands and vessels continue to mature and compact the tissue. In addition, implantation is promoted by the accumulation of glycogen in the endometrium and the appearance of immune cells. Hence, the endometrium becomes more homogeneous and dense on ultrasound, even though its thickness does not in fact increase, and may even slightly decrease. Endometrial compaction thus means that the lining has responded well to progesterone stimulation and is ready to accept the embryo. For this reason, the degree of compaction may be used as an indicator of whether the endometrium is receptive and favorable for pregnancy [

20,

28,

29].

Despite the crucial conceptual developments presented above, initiated by Casper et al. [

15,

16], their studies unfortunately do not present the technical details necessary for understanding and replicating the methodology and thus performing objective and consistent measurements of the thickness of endometrium, e.g., the precise site(s) of measurement, the instruments to be used, or standardized measures. Subsequent studies performed by numerous centers worldwide aimed to confirm or refute the findings reported by Casper et al. [

15,

16] and they can be quite evenly divided into those that partly confirm the results [

17,

18,

19,

20,

30,

31], [30]and those that disprove the findings or are unable to provide a conclusive answer [

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36]. However, in light of the aforementioned methodological omissions, it must be emphasized that the problem persists, as none of these studies describe in sufficient detail key aspects such as what exactly is meant by ‘endometrial thickness’, how it is measured, or the exact site of measurement, among other crucial specifics. Consequently, the fact that varied and incompatible approaches to endometrial thickness measurement were used by different teams of researchers can explain the aforementioned discrepancies in the findings of studies attempting to verify the results obtained by Casper et al. [

15,

16]. In order to obtain consistent results, however, uniform and compatible measurement criteria must be used across different studies, which is the necessary condition for obtaining comparable results that would form the conceptual background of further research.

Furthermore, depending on the site and method of measurement of the value of a parameter, the result may be vastly different and thus may or may not yield meaningful insights into the process. In addition to the methodological inconsistencies outlined above, this strongly implies that performing a single measurement is an insufficient approach, as depending on the exact spot, the endometrium may be characterized by different thickness and undergo various rates of changes [26]. This is why the authors of this study have proposed an approach based on measuring several parameters that describe the endometrium at a given moment, reflecting the studied phenomena much more precisely than a single measurement would. The authors are aware that an approach that requires introducing a larger number of parameters may prove confusing and considerably more difficult to understand as, ideally, only a few variables that explain the whole phenomenon would be preferable. However, as mentioned above, previous studies indicate that as far as endometrial dimensions are concerned, such an approach is clearly insufficient, which is why a slightly more complex methodology is necessary in order to obtain reliable and unambiguous results. Indeed, measuring several parameters at two time points makes it possible to determine the shape of the endometrium and the dynamics of endometrial compaction. Specifically, knowledge about several dimensions of the endometrium allows for estimating the ‘shape’ of the entire organ (e.g., ‘thicker near the uterine body and compacted closer to the cervix’), whereas obtaining the same set of measurements at two time points provides information about the changes the endometrial shape undergoes, which can be described as the ‘dynamics’ of endometrial changes.

The approach described above formed the conceptual for the model created in this study. The model contains three groups of parameters:

- referring to the dimensions and shape of the endometrium at the ovulatory peak,

- referring to the dimensions and shape of the endometrium at the time of transfer,

- referring to changes between the two time points (parameters calculated as the ratio of measurements at both time points).

It must be noted that the proposed model is characterized by a very high predictive value (AUC=0.839), However, in order to responsibly use it for prediction in clinical practice, it must be emphasized that further studies are required to validate it on independent datasets and to test its ‘transferability’ to various clinics, treatment and laboratory procedures and protocols, and other factors specific for a given facility, such as, for instance, varying forms of medications such as progesterone [

37,

38,

39].

The model is based on as many as 11 of the parameters mentioned above, some of which are statistically significant, while others did not reach the established threshold of statistical significance (the highest p-value among the parameters included in the multivariable model is p=0.334, while the lowest p=0.012). Obviously, the levels of statistical significance of the individual parameters included in the model do not matter as the focus is only on the predictive value of the constructed IMP predictor. However, feeling that the p-values of individual parameters provide additional useful insight, the authors of this study have also attempted to interpret the proposed model with respect to which parameters, and in what direction of change, are the most optimal for implantation. It also needs to be emphasized that, within the study group, the model can reliably identify about one-quarter of cases where implantation is highly likely to occur and another quarter where implantation is highly unlikely. This strong discriminatory power highlights the practical value of the IMP predictor.

In this context, it should also be noted that when simple comparisons—or univariate analyses—were performed, no parameter reached the level of statistical significance, which means that on its own, none of the tested parameters is able to explain the tested phenomena. Hence, if only the aforementioned simple analyses had been taken into consideration, then it would have led to the conclusion that the assessment of endometrial compaction is a useless approach. Indeed, this might have been the case with regard to the studies mentioned earlier, aimed at verifying the findings obtained by Casper at al. [

15,

16] are concerned [

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36]. However, the model designed in this study is based on as many as 11 parameters and aims to reflect the dynamics of changes in the shape of endometrium. Although taken individually the parameters do not provide much insight into the tested processes, interestingly, the multivariate approach combines them into a useful model, in which some of them reach the level of statistical significance, while the model itself achieves a high predictive power for implantation.

Finally, the model must be interpreted in the context of those values of its parameters that are conducive to achieving pregnancy, i.e., those that make it possible to achieve endometrial receptiveness. It should be noted that the parameters included in the model reflect only the shape and dimensions of the endometrium and thus cannot be interpreted as pertaining to other aspects such as, for instance, ovum quality.

When explaining certain technical aspects that were taken into account in constructing the IMP predictor, it is worth noting that it is based on the coefficients of individual variables rather than on the odds ratios (OR = e^coefficient) commonly used in the literature. This is because it was created from the formula describing the multivariable logistic regression model, in which the values of individual parameters are multiplied directly by the coefficients. The reason why OR values are not presented in this study is because their interpretation refers to unit changes and thus depends on the units used. In this study, endometrial thickness was expressed in centimeters, whereas the observed changes often concerned differences in millimeters or even fractions of a millimeter. Hence, interpreting the odds ratio for a unit change of 1 cm would yield non-intuitively large values, thus distorting the understanding and interpretation of the obtained results.

The model includes as many as seven parameters referring to the image of the endometrium on the day of the ovulatory peak. These are as follows: the normalized distance from the highest point of the uterine fundus to the first endometrial width (l2n_1); all four normalized widths (w1n_1 to w4n_1), and two parameters referring to the minimum and maximum endometrial widths (max_to_min_1 and min_to_max_1). Positive coefficients of the parameters l2n_1 and the first three widths (w1n_1 to w3n_1) suggest that higher values of these dimensions in the first measurement increase the chances of implantation, whereas the negative coefficient of the fourth width (w4n_1) suggests, on the contrary, that smaller values of this parameter on the day of the ovulatory peak favor implantation. All the above parameters are normalized to the length of the uterus, making them resistant to individual differences in the dimensions of this organ between patients. This leads to the conclusion that an endometrium optimal for embryo implantation should have the largest possible dimensions on the day of the ovulatory peak, but with a distinct narrowing toward the cervix. The significance of this narrowing is confirmed in the literature data [40] as well as through observation of the infrequent cases of patients in whom it is absent or less pronounced, as in these particular cases embryo implantation fails to occur.

The remaining two of the aforementioned parameters (max_to_min_1 and min_to_max_1), which refer to the first measurement on the day of the ovulatory peak, concern the relationship between the minimum and maximum values of the four endometrial width measurements, and indicate that the absolute difference between the largest and smallest width should not be too large. This is also supported by the fact that the relative ratio of minimum to maximum width should optimally have higher values. However, both the relatively small values of the coefficients that correspond to these parameters (-6.9 and 10.1, respectively) and the relatively high p-values (0.187 and 0.334, respectively)—indicating no statistically significant association—suggest that their impact on the effectiveness of the proposed model should not be overestimated.

As far as the second time point of endometrium measurement is concerned, i.e., on the day of transfer, the model includes only the following two parameters: the normalized distance from the highest point of the uterine fundus to the first endometrial width (l2n_2) and the second normalized width (w2n_2). It is worth noting that both parameters have negative coefficients and that the former is characterized by the lowest p-value (p=0.012)—and thus the highest level of statistical significance—among all the coefficients included in the model. This means that the model identifies benefits of smaller normalized endometrial dimensions on the day of transfer, which confirms the importance of endometrial compaction in the context of subsequent embryo implantation. It may be assumed that Casper et al. [

15,

16], as well as other researchers who confirmed these results in their studies [

17,

18,

19,

20,

30,

31], managed to observe this very fact. However, as mentioned earlier, it is difficult to verify this insight precisely due to the lack of detailed descriptions of measurement methodology in their studies.

The remaining two parameters measured at the second time point of endometrium assessment concern the ratios of analogous parameters from the first and second measurements, i.e., the first width (prop_w1) and the normalized distance from the highest point of the uterine fundus to the first endometrial width (prop_l2n). Both ratios confirm the aforementioned necessity for these dimensions to decrease between the ovulatory peak and the day of transfer—indicating that the occurrence of endometrial compaction is necessary in order to increase the chances of embryo implantation. It is noteworthy that both parameters have p-values in the model below the set threshold of statistical significance (0.04 and 0.029, respectively).

Conclusions

The obtained results demonstrate the potential to predict pregnancy outcomes based solely on information regarding endometrial receptivity, without taking into account oocyte quality, maternal age, and other factors whose influence on reproductive success has already been established. The created model shows that while an endometrium with optimal receptivity for accepting a developing embryo should be thicker during the ovulatory peak, it should also exhibit narrowing toward the cervix. By the time of transfer, endometrial compaction should occur, resulting in a decrease in endometrial thickness, particularly in the area of the uterine body and in the region where the endometrial width was originally the greatest. Considering this outcome, it is important to emphasize that combining information, in the next step, on endometrial receptivity with data obtained from other sources that describe phenomena known to affect pregnancy outcomes—such as ovum quality of woman’s age—may yield a predictor of even greater power. After validation and confirmation of its quality and reliability, it could make it possible to predict infertility treatment outcomes with unprecedented accuracy. This, in turn, would enable clinicians to tailor treatment based on the predicted results, which should lead to a significant improvement in the success of ART-based infertility treatments. This approach and direction will constitute the next planned stage of studies, building on the findings presented in this study.

Limitations of the Study

The study was performed on a relatively small sample of patients (61). Although it was a sufficient group for the purpose of this research, i.e., testing a novel hypothesis, in order to confirm the results, studies performed in larger groups are necessary. In addition, the study was performed in a single fertility center, which may have resulted in a study group that does not reflect the characteristics of the general population. Although the retrospective character of the study fitted its intended aim, prospective research could potentially more accurate results.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.M., and W.K.; methodology, R.M. and W.K.; software, R.M., M.S., A.K., A.L. and W.K.; validation, R.M., M.S., A.K., A.L. and W.K.; formal analysis, R.M.; investigation, R.M., M.S., A.K., A.L. and W.K.; resources, A.K., W.K.; data curation, A.K., A.L. and W.K.; writing—original draft preparation, R.M. and M.S.; writing—review and editing, R.M. and M.S.; visualization, R.M. and M.S.; supervision, R.M. and W.K.; funding acquisition, R.M. and W.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. According to applicable Polish law, Bioethics Committee approval was not required, as the study involved research for which such approval is not necessary.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from subjects for the use of their biological material in scientific studies.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Specialist, Infertility Workup for the Women’s Health. ACOG Committee Opinion, Number 781. Obstetrics and gynecology 2019, 133, e377–e384. [CrossRef]

- Starc, A.; Trampuš, M.; Jukić, D.P.; Rotim, C.; Jukić, T.; Mivšek, A.P. INFERTILITY AND SEXUAL DYSFUNCTIONS: A SYSTEMATIC LITERATURE REVIEW. Acta Clin Croat 2019, 58, 508–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mascarenhas, M.N.; Flaxman, S.R.; Boerma, T.; Vanderpoel, S.; Stevens, G.A. National, regional, and global trends in infertility prevalence since 1990: a systematic analysis of 277 health surveys. PLoS Med 2012, 9, e1001356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, J.; Wu, Q.; Liang, Y.; Bin, Q. Epidemiological characteristics of infertility, 1990-2021, and 15-year forecasts: an analysis based on the global burden of disease study 2021. Reprod Health 2025, 22, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Huang, J.; Zhao, Q.; Mo, H.; Su, Z.; Feng, S.; Li, S.; Ruan, X. Global, regional, and national prevalence and trends of infertility among individuals of reproductive age (15-49 years) from 1990 to 2021, with projections to 2040. Human reproduction (Oxford, England) 2025, 40, 529–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carson, S.A.; Kallen, A.N. Diagnosis and Management of Infertility: A Review. JAMA 2021, 326, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, H.; Aghebati-Maleki, L.; Rashidiani, S.; Csabai, T.; Nnaemeka, O.B.; Szekeres-Bartho, J. Long-Term Effects of ART on the Health of the Offspring. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 13564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamel, R.M. Assisted reproductive technology after the birth of louise brown. J. Reprod. Infertil 2013, 14, 96–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milewski, R.; Czerniecki, J.; Kuczyńska, A.; Stankiewicz, B.; Kuczyński, W. Morphokinetic parameters as a source of information concerning embryo developmental and implantation potential. Ginekol Pol 2016, 87, 677–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meseguer, M.; Herrero, J.; Tejera, A.; Hilligsøe, K.M.; Ramsing, N.B.; Remohí, J. The use of morphokinetics as a predictor of embryo implantation. Hum Reprod 2011, 26, 2658–2671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejera, A.; Aparicio-Ruiz, B.; Meseguer, M. The use of morphokinetic as a predictor of implantation. Minerva Ginecol 2017, 69, 555–567. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Milewski, R.; Milewska, A.J.; Kuczyńska, A.; Stankiewicz, B.; Kuczyński, W. Do morphokinetic data sets inform pregnancy potential? Journal of assisted reproduction and genetics 2016, 33, 357–365. [Google Scholar]

- Milewski, R.; Kuczyńska, A.; Stankiewicz, B.; Kuczyński, W. How much information about embryo implantation potential is included in morphokinetic data? A prediction model based on artificial neural networks and principal component analysis. Advances in medical sciences 2017, 62, 202–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milewski, R.; Kuć, P.; Kuczyńska, A.; Stankiewicz, B.; Łukaszuk, K.; Kuczyński, W. A predictive model for blastocyst formation based on morphokinetic parameters in time-lapse monitoring of embryo development. Journal of assisted reproduction and genetics 2015, 32, 571–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, J.; Smith, R.; Zilberberg, E.; Nayot, D.; Meriano, J.; Barzilay, E.; Casper, R.F. Endometrial compaction (decreased thickness) in response to progesterone results in optimal pregnancy outcome in frozen-thawed embryo transfers. Fertility and sterility 2019, 112, 503–509.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zilberberg, E.; Smith, R.; Nayot, D.; Haas, J.; Meriano, J.; Barzilay, E.; Casper, R.F. Endometrial compaction before frozen euploid embryo transfer improves ongoing pregnancy rates. Fertility and sterility 2020, 113, 990–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yaprak, E.; Şükür, Y.E.; Özmen, B.; Sönmezer, M.; Berker, B.; Atabekoğlu, C.; Aytaç, R. Endometrial compaction is associated with the increased live birth rate in artificial frozen-thawed embryo transfer cycles. Human fertility (Cambridge, England) 2023, 26, 550–556. [Google Scholar]

- Ju, W.; Wei, C.; Lu, X.; Zhao, S.; Song, J.; Wang, H.; Yu, Y.; Xiang, S.; Lian, F. Endometrial compaction is associated with the outcome of artificial frozen-thawed embryo transfer cycles: a retrospective cohort study. Journal of assisted reproduction and genetics 2023, 40, 1649–1660. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Lamee, H.; Stone, K.; Powell, S.G.; Wyatt, J.; Drakeley, A.J.; Hapangama, D.K.; Tempest, N. Endometrial compaction to predict pregnancy outcomes in patients undergoing assisted reproductive technologies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Human reproduction open 2024, 2024, hoae040. [Google Scholar]

- Youngster, M.; Mor, M.; Kedem, A.; Gat, I.; Yerushalmi, G.; Gidoni, Y.; Barkat, J.; Baruchin, O.; Revel, A.; Hourvitz, A.; Avraham, S. Endometrial compaction is associated with increased clinical and ongoing pregnancy rates in unstimulated natural cycle frozen embryo transfers: a prospective cohort study. Journal of assisted reproduction and genetics 2022, 39, 1909–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turkgeldi, E.; Yildiz, S.; Kalafat, E.; Keles, I.; Ata, B.; Bozdag, G. Can endometrial compaction predict live birth rates in assisted reproductive technology cycles? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of assisted reproduction and genetics 2023, 40, 2513–2522. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Feng, S.; Wang, B.; Chen, S.; Xie, Q.; Yu, L.; Xiong, C.; Wang, S.; Huang, Z.; Xing, G.; Li, K.; Lu, C.; Zhao, Y.; Li, Z.; Wu, Q.; Huang, J. Association between proliferative-to-secretory endometrial compaction and pregnancy outcomes after embryo transfer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Human reproduction (Oxford, England) 2024, 39, 749–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olgan, S.; Dirican, E.K.; Sakinci, M.; Caglar, M.; Ozsipahi, A.C.; Gul, S.M.; Humaidan, P. Endometrial compaction does not predict the reproductive outcome after vitrified-warmed embryo transfer: a prospective cohort study. Reproductive biomedicine online 2022, 45, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shah, J.S.; Vaughan, D.A.; Dodge, L.E.; Leung, A.; Korkidakis, A.; Sakkas, D.; Ryley, D.A.; Penzias, A.S.; Toth, T.L. Endometrial compaction does not predict live birth in single euploid frozen embryo transfers: a prospective study. Human reproduction (Oxford, England) 2022, 37, 980–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslih, N.; Atzmon, Y.; Bilgory, A.; Raya, Y.S.A.; Sharqawi, M.; Shalom-Paz, E. Does Endometrial Thickness or Compaction Impact the Success of Frozen Embryo Transfer? A Cohort Study Analysis. Journal of clinical medicine 2024, 13, 7254. [Google Scholar]

- Kuijsters, N.P.; Methorst, W.G.; Kortenhorst, M.S.; Rabotti, C.; Mischi, M.; Schoot, B.C. Uterine peristalsis and fertility: current knowledge and future perspectives: a review and meta-analysis. Reprod Biomed Online 2017, 35, 50–71. [Google Scholar]

- Alcázar, J.L. Three-dimensional ultrasound assessment of endometrial receptivity: a review. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 2006, 4, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleischer, A.C.; Pittaway, D.E.; Beard, L.A.; Thieme, G.A.; Bundy, A.L.; James, A.E.J.; Wentz, A.C. Sonographic depiction of endometrial changes occurring with ovulation induction. J Ultrasound Med. 1984, 3, 341–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonen, Y.; Casper, R.F. Prediction of implantation by the sonographic appearance of the endometrium during controlled ovarian stimulation for in vitro fertilization (IVF). J In Vitro Fert Embryo Transf. 1990, 7, 146–152. [Google Scholar]

- Moeinaddini, S.; Dashti, S.; Majomerd, Z.A.; Hatamizadeh, N. Endometrial compaction can improve assisted reproductive technology outcomes in frozen-thawed embryo transfer cycles using hormone replacement therapy: A cross-sectional study. Int J Reprod Biomed 2025, 23, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etezadi, A.; Aghahosseini, M.; Aleyassin, A.; Hosseinimousa, S.; Najafian, A.; Sarvi, F.; Nashtaee, M.S. Investigating the Effect of Endometrial Thickness Changes and Compaction on the Fertility Rate of Patients Undergoing ART: A Prospective Study. J Obstet Gynaecol India 2025, 75, 198–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.T.; Sun, Z.G.; Song, J.Y. Does endometrial compaction before embryo transfer affect pregnancy outcomes? a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2023, 14, 1264608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, M.T.; Li, H.W.R.; Ng, E.H.Y. Impact of Endometrial Thickness and Volume Compaction on the Live Birth Rate Following Fresh Embryo Transfer of In Vitro Fertilization. J Ultrasound Med 2022, 41, 1455–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riestenberg, C.; Quinn, M.; Akopians, A.; Danzer, H.; Surrey, M.; Ghadir, S.; Kroener, L. Endometrial compaction does not predict live birth rate in single euploid frozen embryo transfer cycles. J Assist Reprod Genet 2021, 38, 407–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.; Li, J.; Yang, E.; Shi, H.; Bu, Z.; Niu, W.; Wang, F.; Huo, M.; Song, H.; Zhang, Y. Effect of endometrial thickness changes on clinical pregnancy rates after progesterone administration in a single frozen-thawed euploid blastocyst transfer cycle using natural cycles with luteal support for PGT-SR- and PGT-M-assisted reproduction: a retro. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 2021, 19, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaye, L.; Rasouli, M.A.; Liu, A.; Raman, A.; Bedient, C.; Garner, F.C.; Shapiro, B.S. The change in endometrial thickness following progesterone exposure correlates with in vitro fertilization outcome after transfer of vitrified-warmed blastocysts. J Assist Reprod Genet 2021, 38, 2947–2953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Zhou, P.; Lin, X.; Wang, S.; Zhang, S. Endometria preparation for frozen-thawed embryo transfer cycles: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. J Assist Reprod Genet 2021, 38, 1913–1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roque, M.; Valle, M.; Guimarães, F.; Sampaio, M.; Geber, S. Freeze-all policy: fresh vs. frozen-thawed embryo transfer. Fertil Steril 2015, 103, 1190–1193. [Google Scholar]

- Duijkers, I.J.M.; Klingmann, I.; Prinz, R.; Wargenau, M.; Hrafnsdottir, S.; Magnusdottir, T.B.; Klipping, C. Effect on endometrial histology and pharmacokinetics of different dose regimens of progesterone vaginal pessaries, in comparison with progesterone vaginal gel and placebo. Hum Reprod 2018, 33, 2131–2140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ameer, M.A.; Peterson, D.C. Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis: Uterus, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, 2025.

- Sciorio, R.; Thong, K.J.; Pickering, S.J. Increased pregnancy outcome after day 5 versus day 6 transfers of human vitrified-warmed blastocysts. Zygote 2019, 27, 279–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mengels, A.; Van Muylder, A.; Peeraer, K.; Luyten, J.; Laenen, A.; Spiessens, C.; Debrock, S. Cumulative pregnancy rates of two strategies: Day 3 fresh embryo transfer followed by Day 3 or Day 5/6 vitrification and embryo transfer: a randomized controlled trial. Human reproduction 2024, 39, 62–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbhini, P.G.; Suardika, A.; Anantasika, A.; Adnyana, I.B.P.; Darmayasa, I.M.; Tondohusodo, N.; Sudiman, J. Day-3 vs. Day-5 fresh embryo transfer. JBRA assisted reproduction 2023, 27, 163–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Cai, S.; Zhang, S.; Kong, X.; Gu, Y.; Lu, C.; Dai, J.; Gong, F.; Lu, G.; Lin, G. Single embryo transfer by Day 3 time-lapse selection versus Day 5 conventional morphological selection: a randomized, open-label, non-inferiority trial. Human reproduction 2018, 33, 869–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glujovsky, D.; Retamar, A.M.Q.; Sedo, C.R.A.; Ciapponi, A.; Cornelisse, S.; Blake, D. Cleavage-stage versus blastocyst-stage embryo transfer in assisted reproductive technology. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews 2022, 5, CD002118. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Annan, J.J.K.; Gudi, A.; Bhide, P.; Shah, A.; Homburg, R. Biochemical Pregnancy During Assisted Conception: A Little Bit Pregnant. J Clin Med Res 2013, 5, 269–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).