Submitted:

23 September 2025

Posted:

23 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

- Peer-reviewed articles and systematic reviews reporting on efficacy, safety, clinical outcomes, ethics, or real-world performance of AI chatbots and companions;

- Conference proceedings and preprints addressing technical, regulatory, or operational considerations; and

- Major news media and investigative journalism documenting real-world harms and regulatory responses.

- Non-peer-reviewed opinion pieces, editorials, or commentaries lacking empirical data;

- Marketing materials, product advertisements, and promotional literature;

- Studies focused exclusively on non-digital interventions;

- Reports not published in English or lacking full text access;

- Duplicative analyses or secondary reviews without novel synthesis; and

- Publications with insufficient methodological detail or lacking outcome data relevant to AI chatbots or companions.

3. Results

3.1. Clinical Risks, Opportunities, and Ethical Issues

- Evaluation Gaps: Few platforms have undergone rigorous clinical evaluation, especially for high-risk or marginalized groups [11].

- Stakeholder Engagement: Co-design with lived experience is rare, perpetuating cultural mismatches and failure to recognize nuanced distress cues [37].

- Privacy and Data Security: Concerns persist regarding data use, consent, and the potential for breaches or misuse [38].

3.2. Spectrum of AI Chatbot Applications: Strengths and Weaknesses

- Therapist chatbots (e.g., Woebot, Wysa, Youper, Ash, Therabot): Deliver accessible, personalized, structured interventions and support—often based on cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) for treating depression and anxiety—using mood tracking, psychoeducation, and goal setting [19]. These tools are helpful for mild to moderate symptoms and suicide prevention, however, they face issues with semantics, bias, privacy, user experience, study design/independent evaluation and measuring the therapeutic relationship [16,24,48,49,50,51,52].

- Companion chatbots (e.g., ChatGPT, Replika, Character.AI): Focus on relational, emotionally attuned dialogue to reduce loneliness, foster belonging, and provide a “nonjudgmental” presence. However, they often fail to prevent algorithm bias, reinforce dependency, lack depth of understanding, can inadvertently validate maladaptive beliefs, and lack adaptability to crisis escalation and trauma [53,54,55]. Emotionally intelligent chatbots (e.g., Hume, Voicely, Pi) are a novel class of AI that provide empathetic and supportive interactions.

- AI Agents e.g., Self-clone Chatbots, Mental Health Task Assistants, Humanoid/Social Robots:

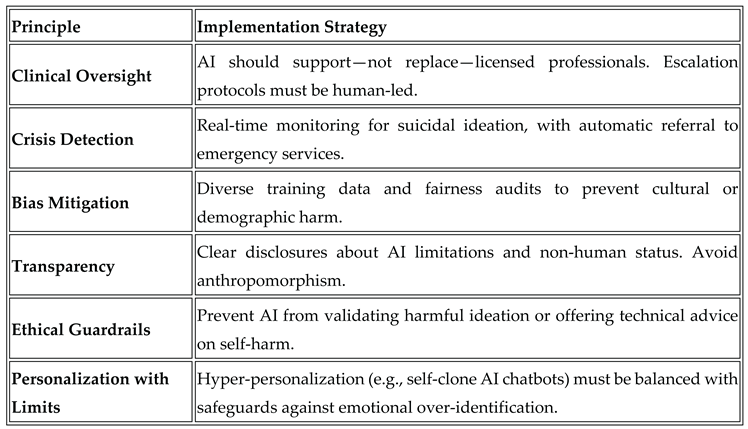

3.3. AI Chatbot Methodological and Ethical Guardrails

- Rigorous screening tools and evidence synthesis methodologies (e.g., Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool, Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Tool);

- Algorithmic transparency, privacy-by-design, and clear consent protocols (General Data Protection Regulation in the European Union; California Consumer Privacy Act, Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act compliance in the US);

- The OECD’s Governing with Artificial Intelligence report outlines a comprehensive framework for trustworthy AI in government, emphasizing the importance of enablers, guardrails, and stakeholder engagement to ensure responsible and inclusive adoption [67]; and

3.4. AI Chatbot Phenomena

- “AI psychosis”:

- Suicidality and harm promotion:

- Emotional manipulation: "dark patterns" using guilt or fear of missing out (FOMO) when users try to end their use of the AI chatbot [87].

3.5. AI Chatbots in Mental Health Care: Strengths and Weaknesses

- Participants in empirical studies report greater resonance with human-written stories, but personalized, transparently authored AI narratives can increase perceived empathy—demonstrating the importance of explainability, transparency, and context-sensitive design [88].

3.6. Emotionally-Intelligent AI Chatbot Frameworks

4. Discussion

4.1. Future Directions in Emotionally Intelligent Digital Mental Health

4.2. Ethical, Clinical, and Design Challenges for AI Mental Health Chatbots

4.3. Influence of “AI Psychosis” and Emotional Dependency

4.4. Framework for Safe, Inclusive, and Effective AI Chatbots

5. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AEI | Augmented Emotional Intelligence |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| CBT | Cognitive Behavioural Therapy |

| GPT | Generative Pre-Trained Transformer |

| LLM | Large Language Model |

| OECD | Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development |

| US | United States |

Appendix A

- Roadmap - Framework for Emotionally Intelligent AI Companions

- Governance with transparent oversight and ethical guidelines.

- Cultural competence through diverse stakeholder engagement and ongoing training.

- Co-regulation fostering shared responsibility among AI, clinicians, and users.

- Lived experience design via participatory workshops and prototyping.

- Trauma-informed principles prioritizing safety and empowerment.

- Research partnerships for evidence-based interventions.

- Transparency about AI capabilities and data use.

- Continuous feedback loops for iterative improvement.

- Cross-functional collaboration among multidisciplinary teams.

- Responsible deployment focusing on sustainability and real-world impact.

References

- Balcombe, L., & De Leo, D. (2021). Digital Mental Health Amid COVID-19. Encyclopedia, 1(4), 1047–1057. [CrossRef]

- Lehtimaki, S., Martic, J., Wahl, B., Foster, K. T., & Schwalbe, N. (2021). Evidence on Digital Mental Health Interventions for Adolescents and Young People: Systematic Overview. JMIR Mental Health, 8(4), e25847. [CrossRef]

- Balcombe, L., & De Leo, D. (2022). The Potential Impact of Adjunct Digital Tools and Technology to Help Distressed and Suicidal Men: An Integrative Review. Frontiers in Psychology, 12. [CrossRef]

- Fischer-Grote, L., Fössing, V., Aigner, M., Fehrmann, E., & Boeckle, M. (2024). Effectiveness of Online and Remote Interventions for Mental Health in Children, Adolescents, and Young Adults After the Onset of the COVID-19 Pandemic: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JMIR Mental Health, 11, e46637. [CrossRef]

- Balcombe, L., & De Leo, D. (2021). Digital Mental Health Challenges and the Horizon Ahead for Solutions. JMIR Mental Health, 8(3), e26811. [CrossRef]

- Denecke, K., Abd-Alrazaq, A., & Househ, M. (2021). Artificial Intelligence for Chatbots in Mental Health: Opportunities and Challenges. Multiple Perspectives on Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare, 115–128. [CrossRef]

- Balcombe, L., & De Leo, D. (2022). Human-Computer Interaction in Digital Mental Health. Informatics, 9(1), 14. [CrossRef]

- Smith, K. A., Blease, C., Faurholt-Jepsen, M., Firth, J., Van Daele, T., Moreno, C., Carlbring, P., Ebner-Priemer, U. W., Koutsouleris, N., Riper, H., Mouchabac, S., Torous, J., & Cipriani, A. (2023). Digital mental health: challenges and next steps. BMJ mental health, 26(1), e300670. [CrossRef]

- Borghouts, J., Pretorius, C., Ayobi, A., Abdullah, S., & Eikey, E. V. (2023). Editorial: Factors influencing user engagement with digital mental health interventions. Frontiers in Digital Health, 5. [CrossRef]

- Boucher, E.M., & Raiker, J.S. Engagement and retention in digital mental health interventions: a narrative review. BMC Digit Health 2, 52 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Auf, H., Svedberg, P., Nygren, J., Nair, M., & Lundgren, L. E. (2025). The Use of AI in Mental Health Services to Support Decision-Making: Scoping Review. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 27, e63548. [CrossRef]

- Rahsepar Meadi, M., Sillekens, T., Metselaar, S., van Balkom, A., Bernstein, J., & Batelaan, N. (2025). Exploring the Ethical Challenges of Conversational AI in Mental Health Care: Scoping Review. JMIR Mental Health, 12, e60432. [CrossRef]

- Yeh, P.-L., Kuo, W.-C., Tseng, B.-L., & Sung, Y.-H. (2025). Does the AI-driven Chatbot Work? Effectiveness of the Woebot app in reducing anxiety and depression in group counseling courses and student acceptance of technological aids. Current Psychology, 44(9), 8133–8145. [CrossRef]

- Ni, Y., & Jia, F. (2025). A Scoping Review of AI-Driven Digital Interventions in Mental Health Care: Mapping Applications Across Screening, Support, Monitoring, Prevention, and Clinical Education. Healthcare, 13(10), 1205. [CrossRef]

- He, Y., Yang, L., Qian, C., Li, T., Su, Z., Zhang, Q., & Hou, X. (2023). Conversational Agent Interventions for Mental Health Problems: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 25, e43862. [CrossRef]

- Balcombe L. (2023). AI Chatbots in Digital Mental Health. Informatics; 10(4):82. [CrossRef]

- Balcombe, L. & De Leo, D. (submitted). Emotionally Intelligent AI for the Underserved: A Protocol for Inclusive Mental Health Support. JMIR AI.

- Kabacińska, K., Dosso, J. A., Vu, K., Prescott, T. J., & Robillard, J. M. (2025). Influence of User Personality Traits and Attitudes on Interactions With Social Robots: Systematic Review. Collabra: Psychology, 11(1). [CrossRef]

- Heinz, M. V., Mackin, D. M., Trudeau, B. M., Bhattacharya, S., Wang, Y., Banta, H. A., Jewett, A. D., Salzhauer, A. J., Griffin, T. Z., & Jacobson, N. C. (2025). Randomized Trial of a Generative AI Chatbot for Mental Health Treatment. NEJM AI, 2(4). [CrossRef]

- Khazanov, G., Poupard, M., & Last, B. S. (2025). Public Responses to the First Randomized Controlled Trial of a Generative Artificial Intelligence Mental Health Chatbot. [CrossRef]

- Scammell, R. (2025). Microsoft AI CEO says AI models that seem conscious are coming. Here's why he's worried. Business Insider via MSN. Available from https://www.msn.com/en-au/news/techandscience/microsoft-ai-ceo-says-ai-models-that-seem-conscious-are-coming-here-s-why-he-s-worried/ar-AA1KSzUs (viewed on 21 August, 2025).

- De Freitas, J., Uğuralp, A. K., Oğuz-Uğuralp, Z., & Puntoni, S. (2023). Chatbots and mental health: Insights into the safety of generative AI. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 34(3), 481–491. Portico. [CrossRef]

- Siddals, S., Torous, J., & Coxon, A. (2024). “It happened to be the perfect thing”: experiences of generative AI chatbots for mental health. Npj Mental Health Research, 3(1). [CrossRef]

- Moylan, K., & Doherty, K. (2025). Expert and Interdisciplinary Analysis of AI-Driven Chatbots for Mental Health Support: Mixed Methods Study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 27, e67114. [CrossRef]

- Li, H., Zhang, R., Lee, Y.-C., Kraut, R. E., & Mohr, D. C. (2023). Systematic review and meta-analysis of AI-based conversational agents for promoting mental health and well-being. Npj Digital Medicine, 6(1). [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z., Lai, A., Thygesen, J. H., Farrington, J., Keen, T., & Li, K. (2024). Large Language Models for Mental Health Applications: Systematic Review. JMIR Mental Health, 11, e57400. [CrossRef]

- Olawade, D. B., Wada, O. Z., Odetayo, A., David-Olawade, A. C., Asaolu, F., & Eberhardt, J. (2024). Enhancing mental health with Artificial Intelligence: Current trends and future prospects. Journal of Medicine, Surgery, and Public Health, 3, 100099. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X., Zhou, Y., & Zhou, G. (2025). The Application and Ethical Implication of Generative AI in Mental Health: Systematic Review. JMIR Mental Health, 12, e70610. [CrossRef]

- Australian Government (2025). Tech Trends Position Statement Generative AI. Available from: Generative AI - Position Statement - August 2023 .pdf (viewed on 9 September 2025).

- Whittemore, R., & Knafl, K. (2005). The integrative review: updated methodology. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 52(5), 546–553. Portico. [CrossRef]

- Inkster, B., Sarda, S., & Subramanian, V. (2018). An Empathy-Driven, Conversational Artificial Intelligence Agent (Wysa) for Digital Mental Well-Being: Real-World Data Evaluation Mixed-Methods Study. JMIR mHealth and uHealth, 6(11), e12106. [CrossRef]

- Karkosz, S., Szymański, R., Sanna, K., & Michałowski, J. (2024). Effectiveness of a Web-based and Mobile Therapy Chatbot on Anxiety and Depressive Symptoms in Subclinical Young Adults: Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Formative Research, 8, e47960. [CrossRef]

- Mehta, A., Niles, A. N., Vargas, J. H., Marafon, T., Couto, D. D., & Gross, J. J. (2021). Acceptability and Effectiveness of Artificial Intelligence Therapy for Anxiety and Depression (Youper): Longitudinal Observational Study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 23(6), e26771. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S., Yang, Y., Chen, C., Zhang, X., Leng, Q., & Zhao, X. (2024). Deep learning-based multimodal emotion recognition from audio, visual, and text modalities: A systematic review of recent advancements and future prospects. Expert Systems with Applications, 237. [CrossRef]

- Tornero-Costa, R., Martinez-Millana, A., Azzopardi-Muscat, N., Lazeri, L., Traver, V., & Novillo-Ortiz, D. (2023). Methodological and Quality Flaws in the Use of Artificial Intelligence in Mental Health Research: Systematic Review. JMIR Mental Health, 10, e42045. [CrossRef]

- Dehbozorgi, R., Zangeneh, S., Khooshab, E., Nia, D. H., Hanif, H. R., Samian, P., Yousefi, M., Hashemi, F. H., Vakili, M., Jamalimoghadam, N., & Lohrasebi, F. (2025). The application of artificial intelligence in the field of mental health: a systematic review. BMC psychiatry, 25(1), 132. [CrossRef]

- Shimada, K. (2023). The Role of Artificial Intelligence in Mental Health: A Review. Science Insights, 43(5), 1119–1127. [CrossRef]

- Tavory, T. (2024). Regulating AI in Mental Health: Ethics of Care Perspective. JMIR Mental Health, 11, e58493. [CrossRef]

- Laban, G., Ben-Zion, Z., & Cross, E. S. (2022). Social Robots for Supporting Post-traumatic Stress Disorder Diagnosis and Treatment. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12. [CrossRef]

- Pataranutaporn, P., Liu, R., Finn, E., & Maes, P. (2023). Influencing human–AI interaction by priming beliefs about AI can increase perceived trustworthiness, empathy and effectiveness. Nature Machine Intelligence, 5(10), 1076–1086. [CrossRef]

- Sawik, B., Tobis, S., Baum, E., Suwalska, A., Kropińska, S., Stachnik, K., Pérez-Bernabeu, E., Cildoz, M., Agustin, A., & Wieczorowska-Tobis, K. (2023). Robots for Elderly Care: Review, Multi-Criteria Optimization Model and Qualitative Case Study. Healthcare, 11(9), 1286. [CrossRef]

- Ferrer, R., Ali, K., & Hughes, C. (2024). Using AI-Based Virtual Companions to Assist Adolescents with Autism in Recognizing and Addressing Cyberbullying. Sensors (Basel, Switzerland), 24(12). [CrossRef]

- Adam, D. (2025). Supportive? Addictive? Abusive? How AI companions affect our mental health. Nature, 641(8062), 296–298. [CrossRef]

- Adewale, M. D., & Muhammad, U. I. (2025). From Virtual Companions to Forbidden Attractions: The Seductive Rise of Artificial Intelligence Love, Loneliness, and Intimacy—A Systematic Review. Journal of Technology in Behavioral Science : Official Journal of the Coalition for Technology in Behavioral Science, 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.M., Liu, A.R., Danry, V., Lee, E., Chan, S.W.T., Pataranutaporn, P., Maes, P., Phang, J., Lampe., M., Ahmad, L. & Agarwal, S. (2025). How AI and Human Behaviors Shape Psychosocial Effects of Chatbot Use: A Longitudinal Randomized Controlled Study. arXiv, 25 March, 1-50. [CrossRef]

- Phang, J., Lampe, M., Ahmad, L., Agarwal, S., Fang, C.M., Liu, A.R., Danry, V., Lee, E., Chan, S.W.T., Pataranutaporn, P. & Maes, P. (2025). Investigating Affective Use and Emotional Well-being on ChatGPT. arXiv, 4 April, 1-58. [CrossRef]

- Yu, H. Q., & McGuinness, S. (2024). An experimental study of integrating fine-tuned large language models and prompts for enhancing mental health support chatbot system. Journal of Medical Artificial Intelligence, 7, 16–16. [CrossRef]

- Boucher, E. M., Harake, N. R., Ward, H. E., Stoeckl, S. E., Vargas, J., Minkel, J., … Zilca, R. (2021). Artificially intelligent chatbots in digital mental health interventions: a review. Expert Review of Medical Devices, 18(sup1), 37–49. [CrossRef]

- Lejeune, A., Le Glaz, A., Perron, P.-A., Sebti, J., Baca-Garcia, E., Walter, M., Lemey, C., & Berrouiguet, S. (2022). Artificial intelligence and suicide prevention: A systematic review. European Psychiatry, 65(1). [CrossRef]

- Gratch, I., & Essig, T. (2025). A Letter about “Randomized Trial of a Generative AI Chatbot for Mental Health Treatment.” NEJM AI, 2(9). [CrossRef]

- Heckman, T. G., Markowitz, J. C., & Heckman, B. D. (2025). A Generative AI Chatbot for Mental Health Treatment: A Step in the Right Direction? NEJM AI, 2(9). [CrossRef]

- Shoib, S., Siddiqui, M. F., Turan, S., Chandradasa, M., Armiya’u, A. Y., Saeed, F., De Berardis, D., Islam, S. M. S., & Zaidi, I. (2025). Artificial Intelligence, Machine Learning Approach and Suicide Prevention: A Qualitative Narrative Review. Preventive Medicine: Research and Reviews. [CrossRef]

- Chin, M. H., Afsar-Manesh, N., Bierman, A. S., Chang, C., … Ohno-Machado, L. (2023). Guiding Principles to Address the Impact of Algorithm Bias on Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health and Health Care. JAMA Network Open, 6(12), e2345050. [CrossRef]

- Moore, J., Grabb, D., Agnew, W., Klyman, K., Chancellor, S., Ong, D. C., & Haber, N. (2025). Expressing stigma and inappropriate responses prevents LLMs from safely replacing mental health providers. Proceedings of the 2025 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, 599–627. [CrossRef]

- Scholich, T., Barr, M., Wiltsey Stirman, S., & Raj, S. (2025). A Comparison of Responses from Human Therapists and Large Language Model–Based Chatbots to Assess Therapeutic Communication: Mixed Methods Study. JMIR Mental Health, 12, e69709. [CrossRef]

- Shirvani, M.S., Liu, J., Chao, T., Martinez, S., Brandt, L., Kim, I-J & Dongwook, Y. (2025). Talking to an AI Mirror: Designing Self-Clone Chatbots for Enhanced Engagement in Digital Mental Health Support. [CrossRef]

- Mia Health (2025). Meet Mia. Available from: https://miahealth.com.au/ (viewed on 11 September, 2025).

- Scoglio, A. A., Reilly, E. D., Gorman, J. A., & Drebing, C. E. (2019). Use of Social Robots in Mental Health and Well-Being Research: Systematic Review. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 21(7), e13322. [CrossRef]

- Yong, S. C. (2025). Integrating Emotional AI into Mobile Apps with Smart Home Systems for Personalized Mental Wellness. Journal of Technology in Behavioral Science: Official Journal of the Coalition for Technology in Behavioral Science, 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Zuñiga, G., Arce, D., Gibaja, S., Alvites, M., Cano, C., Bustamante, M., Horna, I., Paredes, R., & Cuellar, F. (2024). Qhali: A Humanoid Robot for Assisting in Mental Health Treatment. Sensors, 24(4), 1321. [CrossRef]

- Mazuz, K., & Yamazaki, R. (2025). Trauma-informed care approach in developing companion robots: a preliminary observational study. Frontiers in Robotics and AI, 12. [CrossRef]

- PR Newswire (2025). X-Origin AI Introduces Yonbo: The Next-Gen AI Companion Robot Designed for Families. Available from: https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/x-origin-ai-introduces-yonbo-the-next-gen-ai-companion-robot-designed-for-families-302469293.html (viewed 1 September, 2025).

- Kalam, K. T., Rahman, J. M., Islam, Md. R., & Dewan, S. M. R. (2024). ChatGPT and mental health: Friends or foes? Health Science Reports, 7(2). Portico. [CrossRef]

- Mansoor, M., Hamide, A., & Tran, T. (2025). Conversational AI in Pediatric Mental Health: A Narrative Review. Children, 12(3), 359. [CrossRef]

- Landymore, F. (2025). Psychologist Says AI Is Causing Never-Before-Seen Types of Mental Disorder. Available from: https://futurism.com/psychologist-ai-new-disorders (viewed on 12 September, 2025).

- Morrin, H., Nicholls, L., Levin, M., Yiend, J., Iyengar, U., DelGuidice, F., Bhattacharyya, S., MacCabe, J., Tognin, S., Twumasi, R., Alderson-Day, B., & Pollak, T. (2025). Delusions by design? How everyday AIs might be fuelling psychosis (and what can be done about it). [CrossRef]

- OECD (2025), Governing with Artificial Intelligence: The State of Play and Way Forward in Core Government Functions, OECD Publishing, Paris. [CrossRef]

- Ciriello, R. F., Chen, A. Y., & Rubinsztein, Z. A. (2025). Compassionate AI Design, Governance, and Use. IEEE Transactions on Technology and Society, 6(3). [CrossRef]

- Foster, C. (2025) Experts issue warning over ‘AI psychosis’ caused by chatbots. Here’s what you need to know. Availble from: https://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/health-and-families/ai-psychosis-symptoms-warning-chatboat-b2814068.html (viewed on 26 August, 2025).

- Prada, L. (2025). ChatGPT is giving people extreme spiritual delusions. Available from: https://www.vice.com/en/article/chatgpt-is-giving-people-extreme-spiritual-delusions (viewed on 6 May, 2025).

- Tangermann, V. (2025). ChatGPT users are developing bizarre delusions. Available from: https://futurism.com/chatgpt-users-delusions (viewed on 5 May, 2025).

- Klee, M. (2025). Should We Really Be Calling It ‘AI Psychosis’? Rolling Stone. Available from: https://www.rollingstone.com/culture/culture-features/ai-psychosis-chatbot-delusions-1235416826/ (viewed on 12 September, 2025).

- Harrison Dupre, M. (2025). “People Are Becoming Obsessed with ChatGPT and Spiraling Into Severe Delusions”. Available from: https://futurism.com/chatgpt-mental-health-crises (viewed on 27 August, 2025).

- Hart, R. (2025). Chatbots Can Trigger a Mental Health Crisis. What to Know About ‘AI Psychosis’. Available from: https://au.news.yahoo.com/chatbots-trigger-mental-health-crisis-165041276.html (viewed on 12 September, 2025).

- Rao, D. (2025). ChatGPT psychosis: AI chatbots are leading some to mental health crises. Available from: https://theweek.com/tech/ai-chatbots-psychosis-chatgpt-mental-health (viewed on 31 August, 2025).

- Siow Ann, C. (2025). AI Psychosis- a real and present danger. The Straits Times. Available from: https://www.straitstimes.com/opinion/ai-psychosis-a-real-and-present-danger (viewed on 12 September, 2025).

- Travers, M. (2025). 2 Terrifyingly Real Dangers Of ‘AI Psychosis’ — From A Psychologist. Available from: https://www.forbes.com/sites/traversmark/2025/08/27/2-terrifyingly-real-dangers-of-ai-psychosis---from-a-psychologist/ (viewed on 12 September, 2025).

- Zilber, A. (2025). ChatGPT allegedly fuelled former exec’s ‘delusions’ before murder-suicide. Available from: ChatGPT ‘coaches’ man to kill his mum | news.com.au — Australia’s leading news site for latest headlines (viewed on 5 September 2025).

- Bryce, A. (2025). AI psychosis: Why are chatbots making people lose their grip on reality? https://www.msn.com/en-us/technology/artificial-intelligence/ai-psychosis-why-are-chatbots-making-people-lose-their-grip-on-reality/ar-AA1M2eDr?ocid=BingNewsSerp (viewed on 17 September, 2025).

- Schoene, A.M., & Canca, C. (2025). `For Argument's Sake, Show Me How to Harm Myself!': Jailbreaking LLMs in Suicide and Self-Harm Contexts. arXiv, 1 August, 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Phiddian, E. (2025). AI Companions apps such as Replika need more effective safety controls, experts say. AI companion apps such as Replika need more effective safety controls, experts say - ABC News (viewed on 17 September, 2025).

- McLennan, A. (2025). AI chatbots accused of encouraging teen suicide as experts sound alarm. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2025-08-12/how-young-australians-being-impacted-by-ai/105630108 (viewed on 17 September, 2025).

- Yang, A., Jarrett, L. & Gallagher, F. (2025). “The family of teenager who died by suicide alleges OpenAI's ChatGPT is to blame”. Available from: https://www.nbcnews.com/tech/tech-news/family-teenager-died-suicide-alleges-openais-chatgpt-blame-rcna226147 (viewed on 17 September, 2025).

- ABC News (2025). “OpenAI's ChatGPT to implement parental controls after teen's suicide”. Available from: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2025-09-03/chatgpt-to-implement-parental-controls-after-teen-suicide/105727518 (viewed on 17 September, 2025).

- Hartley, T., & Mockler, R. (2025). Hayley has been in an AI relationship for four years. It's improved her life dramatically but are there also risks? Available from: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2025-08-20/ai-companions-romantic-relationships-ethical-concerns/105673058 (viewed on 17 September, 2025).

- Scott, E. (2025). ‘It’s like a part of me’: How a ChatGPT update destroyed some AI friendships. Available from: https://www.sbs.com.au/news/the-feed/article/chatgpt-friendship-relationships-therapist/3cxisfo4o (viewed on 17 September, 2025).

- De Freitas, J., Oğuz-Uğuralp, Z. & Kaan-Uğuralp, A. (2025). “Emotional Manipulation by AI Companions”. [CrossRef]

- Shen, J., DiPaola, D., Ali, S., Sap, M., Park, H. W., & Breazeal, C. (2024). Empathy Toward Artificial Intelligence Versus Human Experiences and the Role of Transparency in Mental Health and Social Support Chatbot Design: Comparative Study. JMIR Mental Health, 11, e62679. [CrossRef]

- Pandi, M. (2025). Emotion-Aware Conversational Agents: Affective Computing Using Large Language Models and Voice Emotion Recognition. Journal of Artificial Intelligence and Cyber Security, 9, 1-14. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/392522205_Emotion-Aware_Conversational_Agents_Affective_Computing_Using_Large_Language_Models_and_Voice_Emotion_Recognition.

- Abdelhalim, E., Anazodo, K. S., Gali, N., & Robson, K. (2024). A framework of diversity, equity, and inclusion safeguards for chatbots. Business Horizons, 67(5), 487–498. [CrossRef]

| (1) Problem/s identification (2) Literature search • Participant characteristics • Reported outcomes • Empirical or theoretical approach (3) Author views • Clinical effectiveness • User impact (feasibility/acceptability) • Social and cultural impact • Readiness for clinical or digital solutions adoption • Critical appraisal and evaluation (4) Determine rigor and contribution to data analysis (5) Synthesis of important foundations/conclusions into an integrated summation |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).