Submitted:

16 September 2025

Posted:

16 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Adipose Tissue and Metabolic Diseases

2.1. The Adipose Tissue as an Endocrine Organ

2.2. Sick Fat and Metabolic Impairment

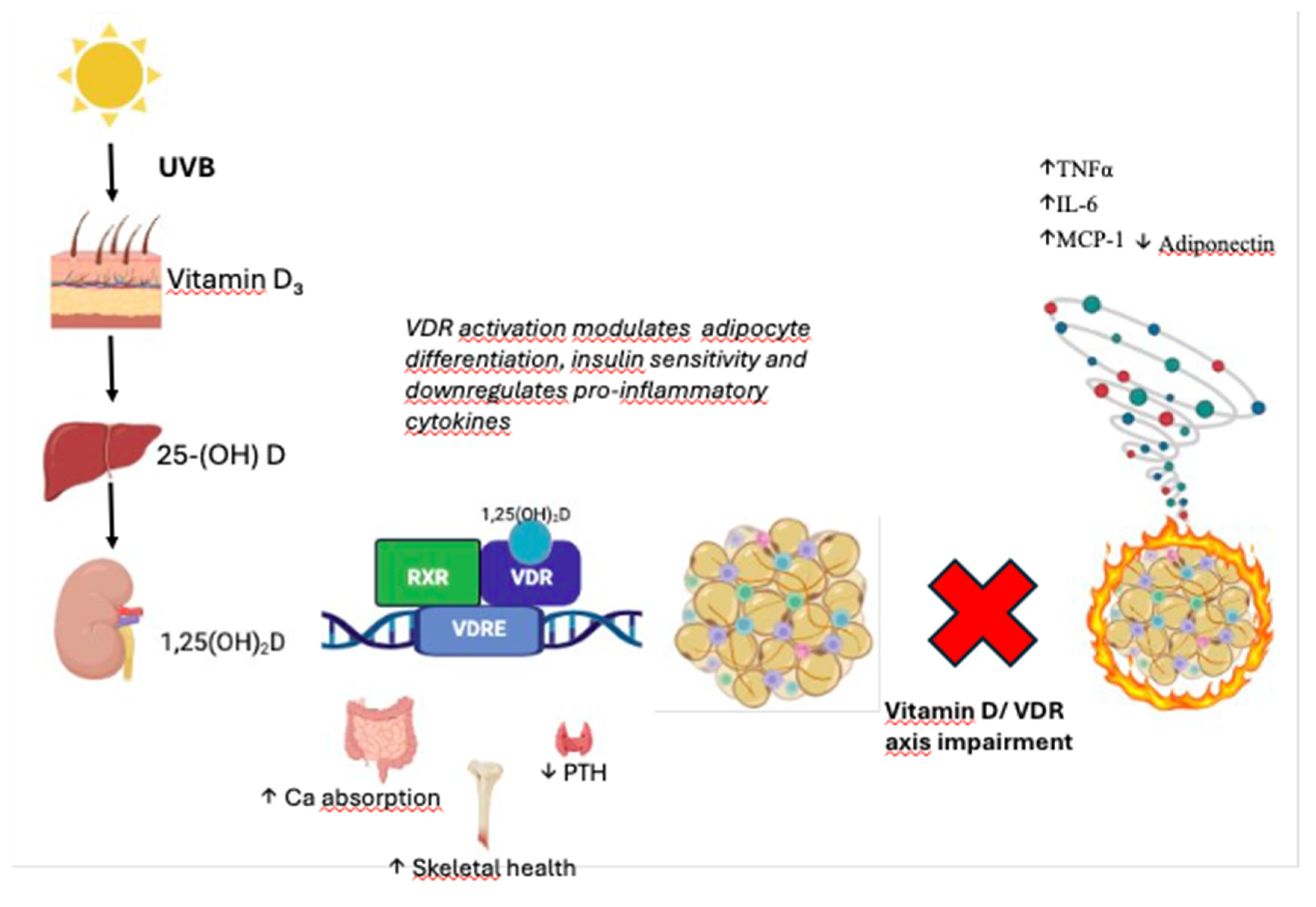

3. The Vitamin D/Vitamin D Receptor Axis in Metabolic Regulation

3.1. Vitamin D and VDR: General Overview

3.2. VD/VDR in Metabolic Diseases: Experimental Evidence

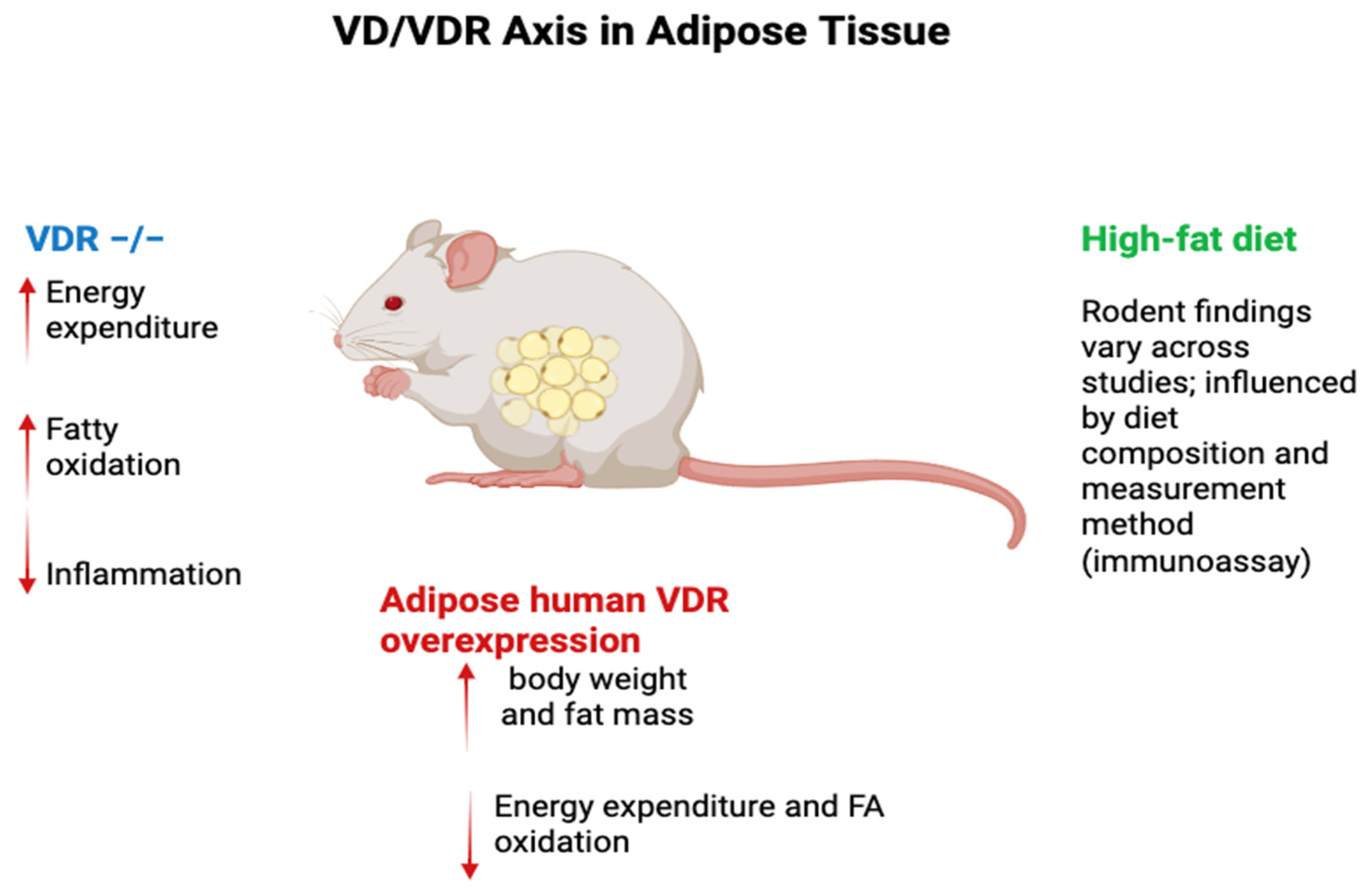

4. VD/VDR Axis and the Adipose Tissue

4.1. Pathways Involved in Adipose Tissue Homeostasis

4.2. From Physiology to Metabolic Impairment

5. Conclusions and Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AT | Adipose Tissue |

| ATEs | Adipose Tissue Eosinophils |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| CoAs | Co-activators |

| CoRs | Co-repressors |

| CYP | Cytochrome |

| DBD | DNA-Binding Domain |

| ECM | Extracellular Matrix |

| FA | Fatty Acid |

| FABP4 | Fatty Acid Binding Protein 4 |

| HF/HFD | High-Fat Diet |

| IL | Interleukin |

| ILC2s | Group 2 Innate Lymphoid Cells |

| LBD | Ligand-Binding Domain |

| MCP-1 | Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein-1 |

| MSC | Mesenchymal Stem Cells |

| nVDRE | Negative Vitamin D Response Element |

| PPAR | Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor |

| RCT | Randomized Clinical Trial |

| RXR | Retinoid X Receptor |

| SAT | Subcutaneous Adipose Tissue |

| SVF | Stromal Vascular Fraction |

| T2D | Type 2 Diabetes |

| TNFα | Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha |

| Treg | Regulatory T Cells |

| UCP | Uncoupling Proteins (UCP1, UCP2, UCP3) |

| VAT | Visceral Adipose Tissue |

| VD | Vitamin D |

| VDR | Vitamin D Receptor |

| VDRE | Vitamin D Response Element |

| 25(OH)D | 25-hydroxyvitamin D |

| 1,25(OH)₂D / 1α,25(OH)₂D₃ | Calcitriol |

References

- Lyall DM, Celis-Morales C, Ward J, Iliodromiti S, Anderson JJ, Gill JMR, et al. Association of Body Mass Index With Cardiometabolic Disease in the UK Biobank: A Mendelian Randomization Study. JAMA Cardiol. 2017 Aug 1;2(8):882-889. PMID: 28678979; PMCID: PMC5710596. [CrossRef]

- Trayhurn P. Endocrine and signalling role of adipose tissue: new perspectives on fat. Acta Physiol Scand. 2005 Aug;184(4):285-93. PMID: 16026420. [CrossRef]

- Vendrell J, Broch M, Vilarrasa N, Molina A, Gómez JM, Gutiérrez C, et al. Resistin, adiponectin, ghrelin, leptin, and proinflammatory cytokines: relationships in obesity. Obes Res. 2004 Jun;12(6):962-71. PMID: 15229336. [CrossRef]

- Than A, He HL, Chua SH, Xu D, Sun L, Leow MK, Chen P. Apelin Enhances Brown Adipogenesis and Browning of White Adipocytes. J Biol Chem. 2015 Jun 5;290(23):14679-91. Epub 2015 Apr 30. PMID: 25931124; PMCID: PMC4505534. [CrossRef]

- Fantuzzi G. Adipose tissue, adipokines, and inflammation. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005 May;115(5):911-9; quiz 920. PMID: 15867843. [CrossRef]

- Steppan CM, Bailey ST, Bhat S, Brown EJ, Banerjee RR, Wright CM, Patel HR, Ahima RS, Lazar MA. The hormone resistin links obesity to diabetes. Nature. 2001 Jan 18;409(6818):307-12. PMID: 11201732. [CrossRef]

- Hildreth AD, Ma F, Wong YY, Sun R, Pellegrini M, O'Sullivan TE. Single-cell sequencing of human white adipose tissue identifies new cell states in health and obesity. Nat Immunol. 2021 May;22(5):639-653. Epub 2021 Apr 27. PMID: 33907320; PMCID: PMC8102391. [CrossRef]

- Meng X, Qian X, Ding X, Wang W, Yin X, Zhuang G, Zeng W. Eosinophils regulate intra-adipose axonal plasticity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2022 Jan 18;119(3):e2112281119. PMID: 35042776; PMCID: PMC8784130. [CrossRef]

- Lumeng CN, Bodzin JL, Saltiel AR. Obesity induces a phenotypic switch in adipose tissue macrophage polarization. J Clin Invest. 2007 Jan;117(1):175-84. PMID: 17200717; PMCID: PMC1716210. [CrossRef]

- Brestoff JR, Kim BS, Saenz SA, Stine RR, Monticelli LA, Sonnenberg GF, et al. Group 2 innate lymphoid cells promote beiging of white adipose tissue and limit obesity. Nature. 2015 Mar 12;519(7542):242-6. Epub 2014 Dec 22. PMID: 25533952; PMCID: PMC4447235. [CrossRef]

- Mahlakõiv T, Flamar AL, Johnston LK, Moriyama S, Putzel GG, Bryce PJ, Artis D. Stromal cells maintain immune cell homeostasis in adipose tissue via production of interleukin-33. Sci Immunol. 2019 May 3;4(35):eaax0416. PMID: 31053655; PMCID: PMC6766755. [CrossRef]

- Kunz HE, Hart CR, Gries KJ, Parvizi M, Laurenti M, Dalla Man C, et al. Adipose tissue macrophage populations and inflammation are associated with systemic inflammation and insulin resistance in obesity. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2021 Jul 1;321(1):E105-E121. Epub 2021 May 17. PMID: 33998291; PMCID: PMC8321823. [CrossRef]

- Weisberg SP, McCann D, Desai M, Rosenbaum M, Leibel RL, Ferrante AW Jr. Obesity is associated with macrophage accumulation in adipose tissue. J Clin Invest. 2003 Dec;112(12):1796-808. PMID: 14679176; PMCID: PMC296995. [CrossRef]

- Considine RV, Sinha MK, Heiman ML, Kriauciunas A, Stephens TW, Nyce MR, Ohannesian JP, Marco CC, McKee LJ, Bauer TL, et al. Serum immunoreactive-leptin concentrations in normal-weight and obese humans. N Engl J Med. 1996 Feb 1;334(5):292-5. PMID: 8532024. [CrossRef]

- Barchetta I, Cimini FA, Ciccarelli G, Baroni MG, Cavallo MG. Sick fat: the good and the bad of old and new circulating markers of adipose tissue inflammation. J Endocrinol Invest. 2019 Nov;42(11):1257-1272. Epub 2019 May 9. PMID: 31073969. [CrossRef]

- Hotamisligil GS, Arner P, Caro JF, Atkinson RL, Spiegelman BM. Increased adipose tissue expression of tumor necrosis factor-alpha in human obesity and insulin resistance. J Clin Invest. 1995 May;95(5):2409-15. PMID: 7738205; PMCID: PMC295872. [CrossRef]

- Divoux A, Tordjman J, Lacasa D, Veyrie N, Hugol D, Aissat A, Basdevant A, Guerre-Millo M, Poitou C, Zucker JD, Bedossa P, Clément K. Fibrosis in human adipose tissue: composition, distribution, and link with lipid metabolism and fat mass loss. Diabetes. 2010 Nov;59(11):2817-25. Epub 2010 Aug 16. PMID: 20713683; PMCID: PMC2963540. [CrossRef]

- Arner P, Bernard S, Salehpour M, Possnert G, Liebl J, Steier P, Buchholz BA, Eriksson M, Arner E, Hauner H, Skurk T, Rydén M, Frayn KN, Spalding KL. Dynamics of human adipose lipid turnover in health and metabolic disease. Nature. 2011 Sep 25;478(7367):110-3. PMID: 21947005; PMCID: PMC3773935. [CrossRef]

- Arkan MC, Hevener AL, Greten FR, Maeda S, Li ZW, Long JM, Wynshaw-Boris A, Poli G, Olefsky J, Karin M. IKK-beta links inflammation to obesity-induced insulin resistance. Nat Med. 2005 Feb;11(2):191-8. Epub 2005 Jan 30. PMID: 15685170. [CrossRef]

- Vandanmagsar B, Youm YH, Ravussin A, Galgani JE, Stadler K, Mynatt RL, Ravussin E, Stephens JM, Dixit VD. The NLRP3 inflammasome instigates obesity-induced inflammation and insulin resistance. Nat Med. 2011 Feb;17(2):179-88. Epub 2011 Jan 9. PMID: 21217695; PMCID: PMC3076025. [CrossRef]

- Mohamed-Ali V, Goodrick S, Rawesh A, Katz DR, Miles JM, Yudkin JS, Klein S, Coppack SW. Subcutaneous adipose tissue releases interleukin-6, but not tumor necrosis factor-alpha, in vivo. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997 Dec;82(12):4196-200. PMID: 9398739. [CrossRef]

- Kanda H, Tateya S, Tamori Y, Kotani K, Hiasa K, Kitazawa R, et al. MCP-1 contributes to macrophage infiltration into adipose tissue, insulin resistance, and hepatic steatosis in obesity. J Clin Invest. 2006 Jun;116(6):1494-505. Epub 2006 May 11. PMID: 16691291; PMCID: PMC1459069. [CrossRef]

- Feuerer M, Herrero L, Cipolletta D, Naaz A, Wong J, Nayer A, et al. Lean, but not obese, fat is enriched for a unique population of regulatory T cells that affect metabolic parameters. Nat Med. 2009 Aug;15(8):930-9. Epub 2009 Jul 26. PMID: 19633656; PMCID: PMC3115752. [CrossRef]

- Spalding KL, Arner E, Westermark PO, Bernard S, Buchholz BA, Bergmann O, Blomqvist L, Hoffstedt J, Näslund E, Britton T, Concha H, Hassan M, Rydén M, Frisén J, Arner P. Dynamics of fat cell turnover in humans. Nature. 2008 Jun 5;453(7196):783-7. Epub 2008 May 4. PMID: 18454136. [CrossRef]

- Jo J, Gavrilova O, Pack S, Jou W, Mullen S, Sumner AE, Cushman SW, Periwal V. Hypertrophy and/or Hyperplasia: Dynamics of Adipose Tissue Growth. PLoS Comput Biol. 2009 Mar;5(3):e1000324. Epub 2009 Mar 27. PMID: 19325873; PMCID: PMC2653640. [CrossRef]

- Donnelly KL, Smith CI, Schwarzenberg SJ, Jessurun J, Boldt MD, Parks EJ. Sources of fatty acids stored in liver and secreted via lipoproteins in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J Clin Invest. 2005 May;115(5):1343-51. PMID: 15864352; PMCID: PMC1087172. [CrossRef]

- Tushuizen ME, Bunck MC, Pouwels PJ, Bontemps S, van Waesberghe JH, Schindhelm RK, Mari A, Heine RJ, Diamant M. Pancreatic fat content and beta-cell function in men with and without type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2007 Nov;30(11):2916-21. Epub 2007 Jul 31. Erratum in: Diabetes Care. 2008 Apr;31(4):835. PMID: 17666465. [CrossRef]

- Hosogai N, Fukuhara A, Oshima K, Miyata Y, Tanaka S, Segawa K, et al. Adipose tissue hypoxia in obesity and its impact on adipocytokine dysregulation. Diabetes. 2007 Apr;56(4):901-11. PMID: 17395738. [CrossRef]

- Sun K, Tordjman J, Clément K, Scherer PE. Fibrosis and adipose tissue dysfunction. Cell Metab. 2013 Oct 1;18(4):470-7. Epub 2013 Aug 15. PMID: 23954640; PMCID: PMC3795900. [CrossRef]

- Festa A, D'Agostino R Jr, Howard G, Mykkänen L, Tracy RP, Haffner SM. Chronic subclinical inflammation as part of the insulin resistance syndrome: the Insulin Resistance Atherosclerosis Study (IRAS). Circulation. 2000 Jul 4;102(1):42-7. PMID: 10880413. [CrossRef]

- Hirosumi J, Tuncman G, Chang L, Görgün CZ, Uysal KT, Maeda K, Karin M, Hotamisligil GS. A central role for JNK in obesity and insulin resistance. Nature. 2002 Nov 21;420(6913):333-6. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature01137. Erratum in: Nature. 2023 Jul;619(7968):E25. PMID: 12447443. [CrossRef]

- Verboven K, Wouters K, Gaens K, Hansen D, Bijnen M, Wetzels S, Stehouwer CD, Goossens GH, Schalkwijk CG, Blaak EE, Jocken JW. Abdominal subcutaneous and visceral adipocyte size, lipolysis and inflammation relate to insulin resistance in male obese humans. Sci Rep. 2018 Mar 16;8(1):4677. PMID: 29549282; PMCID: PMC5856747. [CrossRef]

- Rakotoarivelo V, Lacraz G, Mayhue M, Brown C, Rottembourg D, Fradette J, Ilangumaran S, Menendez A, Langlois MF, Ramanathan S. Inflammatory Cytokine Profiles in Visceral and Subcutaneous Adipose Tissues of Obese Patients Undergoing Bariatric Surgery Reveal Lack of Correlation With Obesity or Diabetes. EBioMedicine. 2018 Apr;30:237-247. Epub 2018 Mar 8. Erratum in: EBioMedicine. 2018 Nov;37:564-568. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2018.10.025. PMID: 29548899; PMCID: PMC5952229. [CrossRef]

- Zhu K, Walsh JP, Hunter M, Murray K, Hui J, Hung J. Longitudinal associations of DXA-measured visceral adipose tissue and cardiometabolic risk in middle-to-older aged adults. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2024 Nov;34(11):2519-2527. Epub 2024 Jun 27. PMID: 39098379. [CrossRef]

- Haussler MR, Haussler CA, Jurutka PW, Thompson PD, Hsieh JC, Remus LS, et al. The vitamin D hormone and its nuclear receptor: molecular actions and disease states. J Endocrinol. 1997;154(Suppl):S57-73. PMID: 9474306.

- Baker AR, McDonnell DP, Hughes M, Crisp TM, Mangelsdorf DJ, Haussler MR, et al. Cloning and expression of full-length cDNA encoding human vitamin D receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85:3294-8. PMID: 2832401.

- Clemens TL, Garrett KP, Zhou XY, Pike JW, Haussler MR, Dempster DW. Immunocytochemical localization of the 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin-D3 receptor in target cells. Endocrinology. 1988;122:1224-30. PMID: 2964912.

- Haussler MR, Whitfield GK, Haussler CA, Hsieh JC, Thompson PD, Selznick SH, et al. The nuclear vitamin D receptor: Biological and molecular regulatory properties revealed. J Bone Miner Res. 1998;13:325-49. PMID: 9517465.

- Stumpf WE, Sar M, Clark SA, DeLuca HF. Brain target sites for 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. Science. 1982;215:1403-5. PMID: 7077371.

- Verstuyf A, Carmeliet G, Bouillon R, Mathieu C. Vitamin D: a pleiotropic hormone. Kidney Int. 2010;78:140-5. PMID: 20410948.

- Saccone D, Asani F, Bornman L. Regulation of the vitamin D receptor gene by environment, genetics and epigenetics. Gene. 2015;561:171-80. PMID: 25725197. [CrossRef]

- Eyles DW, Smith S, Kinobe R, Hewison M, McGrath JJ. Distribution of the vitamin D receptor and 1α-hydroxylase in human brain. J Chem Neuroanat. 2005;29:21-30. PMID: 15961477.

- Zella LA, Kim S, Shevde NK, Pike JW. Enhancers located within two introns of the vitamin D receptor gene mediate transcriptional autoregulation by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. Mol Endocrinol. 2006 Jun;20(6):1231-47. PMID: 16533847.

- Zella LA, Meyer MB, Nerenz RD, Lee SM, Martowicz ML, Pike JW. Multifunctional enhancers regulate mouse vitamin D receptor gene transcription in response to parathyroid hormone, 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3, and retinoid X receptor signaling. Mol Endocrinol. 2010 Jul;24(7):1287-302. PMID: 20494922.

- Zella LA, Meyer MB, Nerenz RD, Martowicz ML, Pike JW. The human vitamin D receptor gene is under promoter control of multiple distal enhancers that integrate the actions of pro-inflammatory and immunoregulatory signaling pathways. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2010 Sep;121(1-2):88-100. PMID: 20673964.

- Lamberg-Allardt C. Vitamin D in foods and as supplements. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2006;92:33-38.

- Adams JS, Clemens TL, Parrish JA, Holick MF. Vitamin-D synthesis and metabolism after ultraviolet irradiation of normal and vitamin-D-deficient subjects. N Engl J Med. 1982;306:722-725.

- Matsuoka LY, Ide L, Wortsman J, MacLaughlin J, Holick MF. Sunscreens suppress cutaneous vitamin D3 synthesis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1987;64:1165-1168. [CrossRef]

- Jorde R, Sneve M, Emaus N, et al. Cross-sectional and longitudinal relation between serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D and body mass index: the Tromso study. Eur J Nutr. 2010;49:401-407.

- Holick MF. The vitamin D deficiency pandemic: Approaches for diagnosis, treatment and prevention. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2017 Jun;18(2):153-165.

- Arai H, Miyamoto K, Taketani Y, Yamamoto H, Iemori Y, Morita K, Tonai T, Nishisho T, Mori S, Takeda E. A vitamin D receptor gene polymorphism in the translation initiation codon: effect on protein activity and relation to bone mineral density in Japanese women. J Bone Miner Res. 1997;12:915-921.

- Bertoccini L, Sentinelli F, Leonetti F, Bailetti D, Capoccia D, Cimini FA, Barchetta I, Incani M, Lenzi A, Cossu E, Cavallo MG, Baroni MG. The vitamin D receptor functional variant rs2228570 (C>T) does not associate with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Endocr Res. 2017 Nov;42(4):331-335. [CrossRef]

- Arai H, Miyamoto KI, Yoshida M, Yamamoto H, Taketani Y, Morita K, et al. The polymorphism in the caudal-related homeodomain protein Cdx-2 binding element in the human vitamin D receptor gene. J Bone Miner Res. 2001;16:1256-1264.

- Sentinelli F, Bertoccini L, Barchetta I, Capoccia D, Incani M, Pani MG, Loche S, Angelico F, Arca M, Morini S, Manconi E, Lenzi A, Cossu E, Leonetti F, Baroni MG, Cavallo MG. The vitamin D receptor (VDR) gene rs11568820 variant is associated with type 2 diabetes and impaired insulin secretion in Italian adult subjects, and associates with increased cardio-metabolic risk in children. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2016 May;26(5):407-413. [CrossRef]

- Fang Y, van Meurs JBJ, d'Alesio A, Jhamai M, Zhao H, Rivadeneira F, Hofman A, van Leeuwen JPT, Jehan F, Pols HAP, Uitterlinden AG. Promoter and 3′-untranslated-region haplotypes in the vitamin D receptor gene predispose to osteoporotic fracture: the Rotterdam study. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;77:807-823.

- Mayr C. Regulation by 3'-Untranslated Regions. Annu Rev Genet. 2017 Nov 27;51:171-194. [CrossRef]

- Mocharla H, Butch AW, Pappas AA, Flick JT, Weinstein RS, De Togni P, Jilka RL, Roberson PK, Parfitt AM, Manolagas SC. Quantification of vitamin D receptor mRNA by competing polymerase chain reaction in PBMC: lack of correspondence with common allelic variants. J Bone Miner Res. 1997;12:726-733.

- Verbeek W, Gombart AF, Shiohara M, Campbell M, Koeffler HP. Vitamin D receptor: no evidence for allele-specific mRNA stability in cells which are heterozygous for the Taq I restriction enzyme polymorphism. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;238:77-80.

- Carling T, Rastad J, Akerstrom G, Westin G. Vitamin D receptor (VDR) and parathyroid hormone messenger ribonucleic acid levels correspond to polymorphic VDR alleles in human parathyroid tumors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83:2255-2259.

- Mangelsdorf DJ, Thummel C, Beato M, Herrlich P, Schütz G, Umesono K, et al. The nuclear receptor superfamily: the second decade. Cell. 1995;83:835-839.

- Carlberg C, Bendik I, Wyss A, Meier E, Sturzenbecker LJ, Grippo JF, Hunziker W. Two nuclear signalling pathways for vitamin D. Nature. 1993 Feb 18;361(6413):657-660. [CrossRef]

- Aranda A, Pascual A. Nuclear hormone receptors and gene expression. Physiol Rev. 2001;81:1269-1304.

- Burke LJ, Baniahmad A. Co-repressors. FASEB J. 2000;14:1876-1888.

- Polly P, Herdick M, Moehren U, Baniahmad A, Heinzel T, Carlberg C. VDR-Alien: a novel, DNA-selective vitamin D(3) receptor-corepressor partnership. FASEB J. 2000 Jul;14(10):1455-63. [CrossRef]

- Tagami T, Lutz WH, Kumar R, Jameson JL. The interaction of the vitamin D receptor with nuclear receptor corepressors and coactivators. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;253:358-363.

- Kim MS, Fujiki R, Murayama A, Kitagawa H, Yamaoka K, Yamamoto Y, Mihara M, Takeyama K, Kato S. 1α,25(OH)2D3-induced transrepression by vitamin D receptor through E-box-type elements in the human parathyroid hormone gene promoter. Mol Endocrinol. 2007;21:334-342.

- Russell J, Ashok S, Koszewski NJ. Vitamin D receptor interactions with the rat parathyroid hormone gene: synergistic effects between two negative vitamin D response elements. J Bone Miner Res. 1999;14:1828-1837.

- Kamei Y, Kawada T, Kazuki R, Ono T, Kato S, Sugimoto E. Vitamin D receptor gene expression is up-regulated by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 in 3T3-L1 preadipocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1993;193(3):948-955. [CrossRef]

- Ding C, Gao D, Wilding J, Trayhurn P, Bing C. Vitamin D signalling in adipose tissue. Br J Nutr. 2012;108:1915-1923. [CrossRef]

- Trayhurn P, O’Hara A, Bing C. Interrogation of microarray datasets indicates that macrophage-secreted factors stimulate the expression of genes associated with vitamin D metabolism (VDR and CYP27B1) in human adipocytes. Adipobiology. 2011;3:29-34.

- Ching S, Kashinkunti S, Niehaus MD, Zinser GM. Mammary adipocytes bioactivate 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 and signal via vitamin D3 receptor, modulating mammary epithelial cell growth. J Cell Biochem. 2011 Nov;112(11):3393-3405. [CrossRef]

- Wamberg L, Christiansen T, Paulsen SK, Fisker S, Rask P, Rejnmark L, Richelsen B, Pedersen SB. Expression of vitamin D-metabolizing enzymes in human adipose tissue—the effect of obesity and diet-induced weight loss. Int J Obes. 2013;37:651-657. [CrossRef]

- Narvaez CJ, Matthews D, Broun E, Chan M, Welsh J. Lean phenotype and resistance to diet-induced obesity in vitamin D receptor knockout mice correlates with induction of uncoupling protein-1 in white adipose tissue. Endocrinology. 2009 Feb;150(2):651-661.

- Manna P, Jain SK. Vitamin D up-regulates glucose transporter 4 (GLUT4) translocation and glucose utilization mediated by cystathionine-γ-lyase (CSE) activation and H2S formation in 3T3L1 adipocytes. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:42324-42332.

- Bidulescu A, Morris AA, Stoyanova N, Meng YX, et al. Association between vitamin D and adiponectin and its relationship with body mass index: the META-Health Study. Front Public Health. 2014;2:193-199.

- Walker GE, Ricotti R, Roccio M, Moia S, Bellone S, Prodam F, Bona G. Pediatric Obesity and Vitamin D Deficiency: A Proteomic Approach Identifies Multimeric Adiponectin as a Key Link between These Conditions. PLoS One. 2014;9:e83685.

- Nimitphong H, Holick MF, Fried SK, Lee MJ. 25-hydroxyvitamin D₃ and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D₃ promote the differentiation of human subcutaneous preadipocytes. PLoS One. 2012;7(12):e52171. Epub 2012 Dec 18. PMID: 23272223; PMCID: PMC3525569. [CrossRef]

- Kong J, Chen Y, Zhu G, Zhao Q, Li YC. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 upregulates leptin expression in mouse adipose tissue. J Endocrinol. 2013;216(2):265-271.

- Vaidya A, Williams JS, Forman JP. The independent association between 25-hydroxyvitamin D and adiponectin and its relation with BMI in two large cohorts: the NHS and the HPFS. Obesity. 2012;20:186-191.

- Neyestani TR, Nikooyeh B, Majd HA, et al. Improvement of Vitamin D Status via Daily Intake of Fortified Yogurt Drink Either with or without Extra Calcium Ameliorates Systemic Inflammatory Biomarkers, including Adipokines, in Subjects with Type 2 Diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:2005-2011.

- Dinca M, Serban MC, Sahebkar A, et al. Does vitamin D supplementation alter plasma adipokines concentrations? A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Pharmacol Res. 2016;107:360-371.

- Lorente-Cebrian S, Eriksson A, Dunlop T, et al. Differential effects of 1α,25-dihydroxycholecalciferol on MCP-1 and adiponectin production in human white adipocytes. Eur J Nutr. 2012;51(3):335-342. [CrossRef]

- Sun X, Morris KL, Zemel MB. Role of calcitriol and cortisol on human adipocyte proliferation and oxidative and inflammatory stress: a microarray study. J Nutrigenet Nutrigenomics. 2008;1:30-48.

- Sergeev IN, Song Q. High vitamin D and calcium intakes reduce diet-induced obesity in mice by increasing adipose tissue apoptosis. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2014;58:1342-1348.

- Li J, Byrne ME, Chang E, Jiang Y, Donkin SS, Buhman KK, Burgess JR, Teegarden D. 1α,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D hydroxylase in adipocytes. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2008 Nov;112(1-3):122-126. [CrossRef]

- Bonnet L, Hachemi MA, Karkeni E, Couturier C, Astier J, Defoort C, Svilar L, Martin JC, Tourniaire F, Landrier JF. Diet induced obesity modifies vitamin D metabolism and adipose tissue storage in mice. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2019 Jan;185:39-46. Epub 2018 Jul 7. PMID: 29990544. [CrossRef]

- Jung YS, Wu D, Smith D, Meydani SN, Han SN. Dysregulated 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D levels in high-fat diet-induced obesity can be restored by changing to a lower-fat diet in mice. Nutr Res. 2018 May;53:51-60. Epub 2018 Mar 20. PMID: 29685623. [CrossRef]

- Wang PQ, Pan DX, Hu CQ, Zhu YL, Liu XJ. Vitamin D-vitamin D receptor system down-regulates expression of uncoupling proteins in brown adipocyte through interaction with Hairless protein. Biosci Rep. 2020 Jun 26;40(6):BSR20194294. PMID: 32452516; PMCID: PMC7286880. [CrossRef]

- Wong KE, Kong J, Zhang W, Szeto FL, Ye H, Deb DK, Brady MJ, Li YC. Targeted expression of human vitamin D receptor in adipocytes decreases energy expenditure and induces obesity in mice. J Biol Chem. 2011 Sep 30;286(39):33804-10. Epub 2011 Aug 12. PMID: 21840998; PMCID: PMC3190828. [CrossRef]

- Matthews DG, D'Angelo J, Drelich J, Welsh J. Adipose-specific Vdr deletion alters body fat and enhances mammary epithelial density. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2016 Nov;164:299-308. Epub 2015 Sep 30. PMID: 26429395; PMCID: PMC4814372. [CrossRef]

- Chang E. Effects of Vitamin D Supplementation on Adipose Tissue Inflammation and NF-κB/AMPK Activation in Obese Mice Fed a High-Fat Diet. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(18):10915. [CrossRef]

- Marziou A, Philouze C, Couturier C, Astier J, Obert P, Landrier JF, Riva C. Vitamin D Supplementation Improves Adipose Tissue Inflammation and Reduces Hepatic Steatosis in Obese C57BL/6J Mice. Nutrients. 2020 Jan 28;12(2):342. PMID: 32012987; PMCID: PMC7071313. [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimzadeh F, Farhangi MA, Tausi AZ, Mahmoudinezhad M, Mesgari-Abbasi M, Jafarzadeh F. Vitamin D supplementation and cardiac tissue inflammation in obese rats. BMC Nutr. 2022 Dec 27;8(1):152. PMID: 36575556; PMCID: PMC9793630. [CrossRef]

- Mallard SR, Howe AS, Houghton LA. Vitamin D status and weight loss: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized and nonrandomized controlled weight-loss trials. Am J Clin Nutr. 2016 Oct;104(4):1151-1159. Epub 2016 Sep 7. PMID: 27604772. [CrossRef]

- Marcotorchino J, Tourniaire F, Astier J, Karkeni E, Canault M, Amiot MJ, Bendahan D, Bernard M, Martin JC, Giannesini B, Landrier JF. Vitamin D protects against diet-induced obesity by enhancing fatty acid oxidation. J Nutr Biochem. 2014 Oct;25(10):1077-1083. Epub 2014 Jun 21. PMID: 25052163. [CrossRef]

- Benetti E, Mastrocola R, Chiazza F, Nigro D, D'Antona G, Bordano V, Fantozzi R, Aragno M, Collino M, Minetto MA. Effects of vitamin D on insulin resistance and myosteatosis in diet-induced obese mice. PLoS One. 2018 Jan 17;13(1):e0189707. PMID: 29342166; PMCID: PMC5771572. [CrossRef]

- Haghighat N, Sohrabi Z, Bagheri R, Akbarzadeh M, Esmaeilnezhad Z, Ashtary-Larky D, Barati-Boldaji R, Zare M, Amini M, Hosseini SV, Wong A, Foroutan H. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Vitamin D Status of Patients with Severe Obesity in Various Regions Worldwide. Obes Facts. 2023;16(6):519-539. Epub 2023 Aug 28. PMID: 37640022; PMCID: PMC10697766. [CrossRef]

- Peng X, Shang G, Wang W, Chen X, Lou Q, Zhai G, Li D, Du Z, Ye Y, Jin X, He J, Zhang Y, Yin Z. Fatty Acid Oxidation in Zebrafish Adipose Tissue Is Promoted by 1α,25(OH)2D3. Cell Rep. 2017 May 16;19(7):1444-1455. PMID: 28514663. [CrossRef]

- Chang E, Kim Y. Vitamin D Insufficiency Exacerbates Adipose Tissue Macrophage Infiltration and Decreases AMPK/SIRT1 Activity in Obese Rats. Nutrients. 2017 Mar 29;9(4):338. PMID: 28353634; PMCID: PMC5409677. [CrossRef]

- Moore CE, Liu Y. Low serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations are associated with total adiposity of children in the United States: National Health and Examination Survey 2005 to 2006. Nutr Res. 2016 Jan;36(1):72-9. Epub 2015 Nov 6. PMID: 26773783. [CrossRef]

- Li YF, Zheng X, Gao WL, Tao F, Chen Y. Association between serum vitamin D levels and visceral adipose tissue among adolescents: a cross-sectional observational study in NHANES 2011-2015. BMC Pediatr. 2022 Nov 4;22(1):634. PMID: 36333688; PMCID: PMC9635166. [CrossRef]

- Nejabat A, Emamat H, Afrashteh S, Jamshidi A, Jamali Z, Farhadi A, Talkhabi Z, Nabipour I, Larijani B, Spitz J. Association of serum 25-hydroxy vitamin D status with cardiometabolic risk factors and total and regional obesity in southern Iran: evidence from the PoCOsteo study. Sci Rep. 2024 Aug 3;14(1):17983. PMID: 39097599; PMCID: PMC11297962. [CrossRef]

- Pott-Junior H, Nascimento CMC, Costa-Guarisco LP, Gomes GAO, Gramani-Say K, Orlandi FS, Gratão ACM, Orlandi AADS, Pavarini SCI, Vasilceac FA, Zazzetta MS, Cominetti MR. Vitamin D Deficient Older Adults Are More Prone to Have Metabolic Syndrome, but Not to a Greater Number of Metabolic Syndrome Parameters. Nutrients. 2020 Mar 12;12(3):748. PMID: 32178228; PMCID: PMC7146307. [CrossRef]

- Konradsen S, Ag H, Lindberg F, Hexeberg S, Jorde R. Serum 1,25-dihydroxy vitamin D is inversely associated with body mass index. Eur J Nutr. 2008 Mar;47(2):87-91. Epub 2008 Mar 4. PMID: 18320256. [CrossRef]

- Pramono A, Jocken JWE, Goossens GH, Blaak EE. Vitamin D release across abdominal adipose tissue in lean and obese men: The effect of β-adrenergic stimulation. Physiol Rep. 2019 Dec;7(24):e14308. PMID: 31872972; PMCID: PMC6928243. [CrossRef]

- Drincic AT, Armas LA, Van Diest EE, Heaney RP. Volumetric dilution, rather than sequestration best explains the low vitamin D status of obesity. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2012 Jul;20(7):1444-8. Epub 2012 Jan 19. PMID: 22262154. [CrossRef]

- Van den Heuvel EG, Lips P, Schoonmade LJ, Lanham-New SA, van Schoor NM. Comparison of the Effect of Daily Vitamin D2 and Vitamin D3 Supplementation on Serum 25-Hydroxyvitamin D Concentration (Total 25(OH)D, 25(OH)D2, and 25(OH)D3) and Importance of Body Mass Index: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Adv Nutr. 2024 Jan;15(1):100133. Epub 2023 Oct 20. PMID: 37865222; PMCID: PMC10831883. [CrossRef]

- Tobias DK, Luttmann-Gibson H, Mora S, Danik J, Bubes V, Copeland T, LeBoff MS, Cook NR, Lee IM, Buring JE, Manson JE. Association of Body Weight With Response to Vitamin D Supplementation and Metabolism. JAMA Netw Open. 2023 Jan 3;6(1):e2250681. PMID: 36648947; PMCID: PMC9856931. [CrossRef]

- Drincic A, Fuller E, Heaney RP, Armas LA. 25-Hydroxyvitamin D response to graded vitamin D₃ supplementation among obese adults. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013 Dec;98(12):4845-4851. Epub 2013 Sep 13. PMID: 24037880. [CrossRef]

- Bacha DS, Rahme M, Al-Shaar L, Baddoura R, Halaby G, Singh RJ, Mahfoud ZR, Habib R, Arabi A, El-Hajj Fuleihan G. Vitamin D3 Dose Requirement That Raises 25-Hydroxyvitamin D to Desirable Level in Overweight and Obese Elderly. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021 Aug 18;106(9):e3644-e3654. PMID: 33954783; PMCID: PMC8372651. [CrossRef]

- Ochs-Balcom HM, Chennamaneni R, Millen AE, Shields PG, Marian C, Trevisan M, Freudenheim JL. Vitamin D receptor gene polymorphisms are associated with adiposity phenotypes. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011 Jan;93(1):5-10. Epub 2010 Nov 3. PMID: 21048058; PMCID: PMC3001595. [CrossRef]

- Khan RJ, Riestra P, Gebreab SY, Wilson JG, Gaye A, Xu R, Davis SK. Vitamin D Receptor Gene Polymorphisms Are Associated with Abdominal Visceral Adipose Tissue Volume and Serum Adipokine Concentrations but Not with Body Mass Index or Waist Circumference in African Americans: The Jackson Heart Study. J Nutr. 2016 Aug;146(8):1476-1482. Epub 2016 Jun 29. PMID: 27358421; PMCID: PMC4958289. [CrossRef]

- Correa-Rodríguez M, Carrillo-Ávila JA, Schmidt-RioValle J, González-Jiménez E, Vargas S, Martín J, Rueda-Medina B. Genetic association analysis of vitamin D receptor gene polymorphisms and obesity-related phenotypes. Gene. 2018 Jan 15;640:51-56. Epub 2017 Oct 13. PMID: 29032145. [CrossRef]

- Rock CL, Emond JA, Flatt SW, Heath DD, Karanja N, Pakiz B, Sherwood NE, Thomson CA. Weight loss is associated with increased serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D in overweight or obese women. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2012 Nov;20(11):2296-2301. Epub 2012 Mar 8. PMID: 22402737; PMCID: PMC3849029. [CrossRef]

- Holt R, Holt J, Jorsal MJ, Sandsdal RM, Jensen SBK, Byberg S, Juhl CR, Lundgren JR, Janus C, Stallknecht BM, Holst JJ, Juul A, Madsbad S, Jensen MB, Torekov SS. Weight Loss Induces Changes in Vitamin D Status in Women With Obesity But Not in Men: A Randomized Clinical Trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2025 Jul 15;110(8):2215-2224. PMID: 39530599; PMCID: PMC12261087. [CrossRef]

| Function | Description | Key Molecules / Cells |

| Energy Storage and Release | Storage of triglycerides and regulated lipolysis to provide energy when needed | Triglycerides, Lipolysis pathways |

| Endocrine Function | Secretion of adipokines that influence systemic metabolism, appetite, and insulin sensitivity | Leptin, Adiponectin, Resistin, Apelin, Visfatin, Adipsin |

| Metabolic Regulation | Modulation of insulin sensitivity, energy expenditure, and glucose homeostasis | Adiponectin (↑ sensitivity), Leptin, Resistin (↓ sensitivity) |

|

Neuro-immune Interaction |

Sympathetic innervation influences lipolysis and immune activity; immune cells secrete neurotrophic factors influencing sympathetic tone |

Sympathetic nerves, Neurotrophic factors, Macrophages, Eosinophils |

| Immune Cell Niche | Stromal vascular fraction (SVF) supports mesenchymal, endothelial, and immune cells forming a regulatory microenvironment | SVF, MSCs, Endothelial cells |

| Function | Description | Key Molecules / Cells |

| Inflammatory Signaling | Release of cytokines and regulation of local and systemic inflammation Balance of M1 (pro-inflammatory) and M2 (anti-inflammatory) macrophages determines inflammatory status and insulin sensitivity |

IL-6, TNFα, IL-10, IL-1β, IL-12, IL-23, M1: TNFα, IL-1β, M2: IL-10 |

| Immune modulation | Interaction with resident immune cells (macrophages, eosinophils, ILC2s, T cells) that modulate inflammation and tissue homeostasis. Maintenance of metabolic homeostasis via ILC2-induced eosinophil activation, which promotes M2 macrophage polarization |

M1/M2 macrophages, ILC2s, ATEs, T cells M1: TNFα, IL-1β, M2: IL-10 |

| Pathophysiology in obesity | Dysfunctional adipokine secretion and immune infiltration lead to chronic low-grade inflammation ("metaflammation") and metabolic disease progression | ↓ Adiponectin, ↑ Leptin/Resistin, ↑ M1 macrophages |

| Aspect | Details | References |

| VDR Expression | Expression nearly ubiquitous across ~250 human tissues/cell types. highest Protein levelsin adipose tissue, bone, kidneys, intestine low/absent in erythrocytes, striated muscle, Purkinje cells. |

Baker AR, 1988; Clemens TL, 1988; Eyles DW, 2005; Verstuyf A, 2010 |

| Genome Control | >3% of human genome under direct or indirect VDR control. |

Saccone 2015 |

| Autoregulation (VDREs) | Highly conserved VDRE regions in two large introns and 6 kb upstream of TSS. Allow VDR to autoregulate its own expression. |

Zella et al., 2006, 2010 |

| Promoters | Four promoters control VDR transcription, some tissue-specific, contributing to functional diversity. |

Saccone D 2015 |

| Environmental Regulators | UVB exposure increases VDR expression; sunscreens decrease it. Dietary vitamin D intake influences VDR levels. Obesity, air pollution, aging also modulate expression. |

Adams JS, 1982; Matsuoka LY, 1987; Jorde R, 2010; Holick MF, 2017 |

| Adipose Tissue Expression |

VDR expressed in 3T3-L1 adipocytes, human pre-adipocytes, differentiated adipocytes, subcutaneous/visceral AT, and mammary adipocytes. Highlights role of vitamin D/VDR in adipose inflammation and metabolism. |

Kamei Y, 1993; Ding 2012 |

| Structural Domains |

VDR belongs to nuclear receptor superfamily with conserved DNA-binding domain (DBD) and ligand-binding domain (LBD). | Mangelsdorf DJ, 1995 |

| Polymorphism rs11568820 (Cdx2) | G>A in promoter; A-allele enhances Cdx-2 transcription factor binding, increasing intestine-specific VDR transcription. AA genotype linked to higher T2DM risk and impaired insulin secretion, and early-life cardiometabolic alterations. |

Arai H, 2001; Sentinelli F 2016 |

| Polymorphisms BsmI/ApaI/TaqI | Located in 3′-UTR; studies show conflicting effects on mRNA stability and transcript levels; potential linkage with other regulatory sequences. | Mocharla et al., 1997; Verbeek W, 1997; Carling et al., 1998 |

| Polymorphism rs2228570 (FokI) | C>T at start codon; C-allele uses downstream ATG yielding shorter VDR (424 aa) with higher transactivation compared to long form (427 aa). |

Arai et al., 1997; Bertoccini L 2017 |

| Co-regulators & nVDREs | Co-activators (CoAs) remodel chromatin and promote transcription; co-repressors (CoRs) condense chromatin to repress genes. Negative VDREs in some targets mediate transcriptional repression. |

Aranda A, 2001; Burke LJ, 2000; Kim MS, 2007 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).