Submitted:

16 September 2025

Posted:

17 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

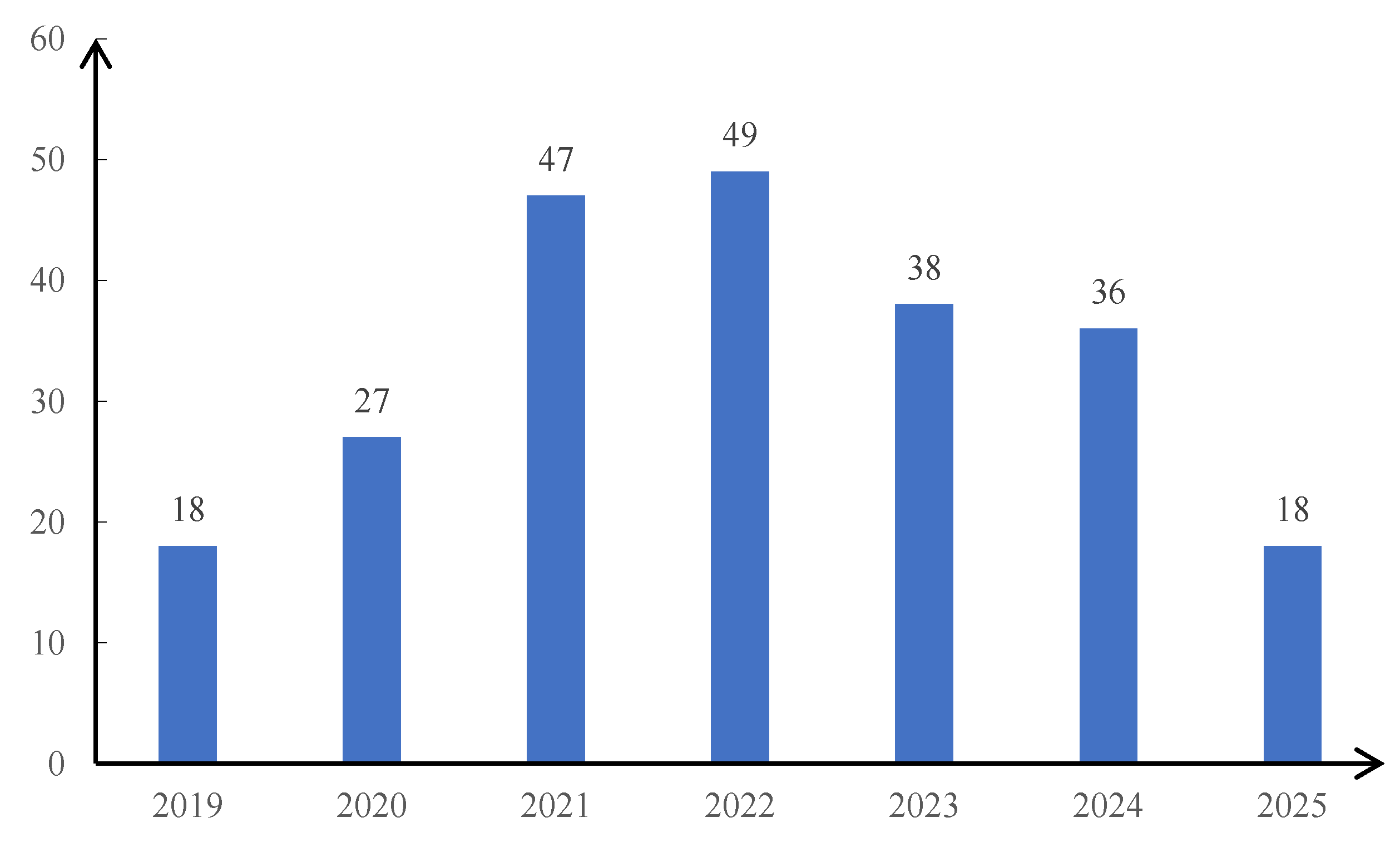

2. Methodology

3. Consumer Panic Stockpiling Behavior under Supply Disruption Risk

3.1. Consumers’ Behavioral Responses to the Risk of Supply Disruption

3.1.1. Behavioral Classification and Trigger Mechanisms

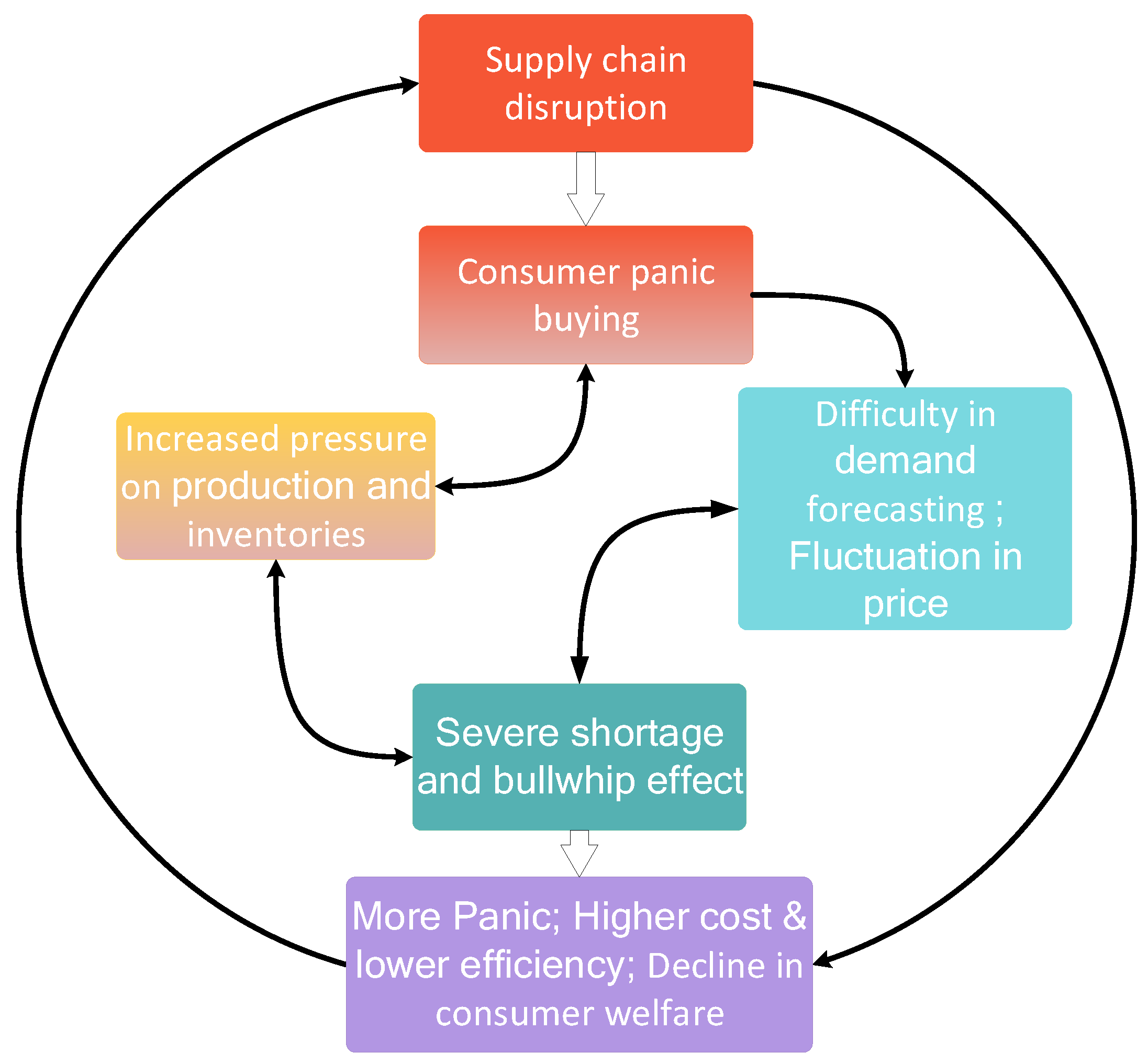

3.1.2. Chain Reactions on the Supply Chain

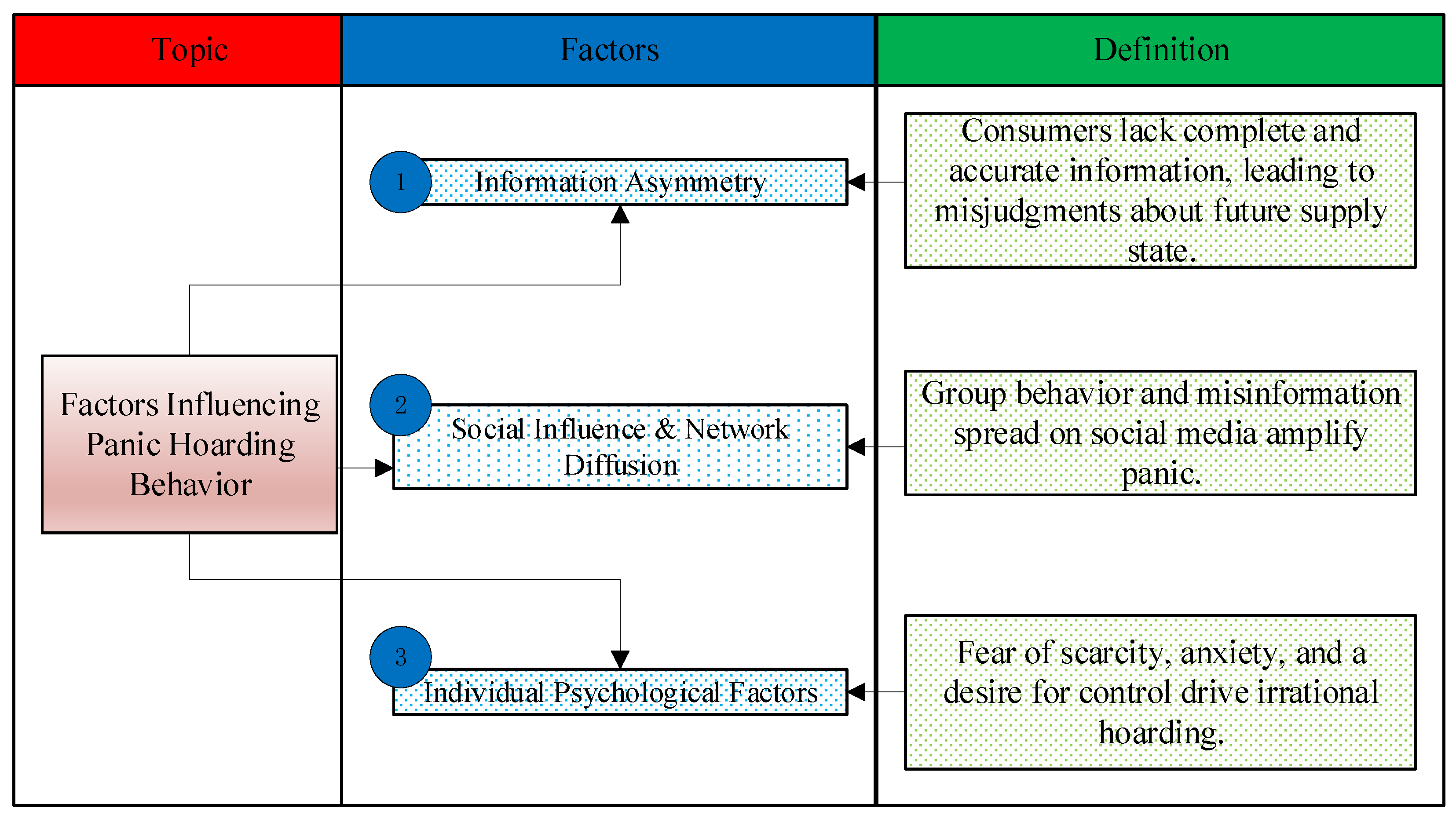

3.2. Factors Affecting Consumers’ Panic Stockpiling Behavior

4. Supply Chain Management under Consumer Panic Buying Behavior

4.1. How does supply chain strategy affect consumer behavior?

4.2. How does consumer behavior affect supply chain management?

4.3. An example of interaction between supply chain management and consumer behavior during COVID-19 epidemics

4.4. Supply Chain Management Strategies for Responding to Consumer Panic Buying Behavior

4.4.1. Strategies to Alleviate Consumers’ Panic Psychology

4.4.2. Supply Chain Elasticity and Inventory Management

4.4.3. Government intervention and retailer intervention

5. Impact of Panic Buying on Supply Chain Performance and Social Welfare

5.1. Impact of Panic Buying on Supply Chain Performance

5.2. Impact of Panic Buying on Consumer Welfare

5.3. Interaction between supply chain performance and consumer welfare

6. Discussion

6.1. Enhanced Examination of Supply Chain Disruptions, Consumer Panic Buying, and Their Impact

6.2. Dynamic Adjustment of Supply Chain Management Strategies During Panic Buying

6.3. Complex Impact of Panic Buying on Consumer Welfare and Supply Chain Performance

Funding

References

- Sim, K.; Chua, H.C.; Vieta, E.; Fernandez, G. The anatomy of panic buying related to the current COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry research 2020, 288, 113015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ennews.com. Demand Surged 1400the Shelves! https://www.ennews.com/article-14484-1.html, 2020. Accessed: 2025-04-04.

- News, S. Fearing a further escalation of the epidemic, citizens in Hong Kong are hoarding, and supermarkets issue purchase restrictions. https://www.sohu.com/a/407848066_120051716, 2020. Accessed: 2025-04-05.

- Kogan, K.; Herbon, A. Retailing under panic buying and consumer stockpiling: Can governmental intervention make a difference? International Journal of Production Economics 2022, 254, 108631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhenjie, S. Information Disclosure and Irrational Panic Buying Behavior: Based on COVID-19 Epidemic Analysis. Research Management 2020, 41, 149–156. [Google Scholar]

- Arafat, S.Y.; Hakeem, S.; Kar, S.K.; Singh, R.; Shrestha, A.; Kabir, R. Communication during disasters: role in contributing to and prevention of panic buying. In Panic Buying and Environmental Disasters: Management and Mitigation Approaches; Springer, 2022; pp. 161–175. [CrossRef]

- Panic buying: How grocery stores restock shelves in the age of coronavirus | CNN Business. https://edition.cnn.com/2020/03/20/business/panic-buying-how-stores-restock-coronavirus/index.html, 2020. Accessed: 2025-04-05.

- Commerce. The Ministry of commerce deploys the work of ensuring supply and stabilizing prices of vegetable and other essential goods in the market. http://www.mofcom.gov.cn/article/syxwfb/202111/20211103213485.shtml, 2021. Accessed: 2025-04-05.

- Tranfield, D.; Denyer, D.; Smart, P. Towards a methodology for developing evidence-informed management knowledge by means of systematic review. British journal of management 2003, 14, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, C.; Booth, A.; Varley-Campbell, J.; Britten, N.; Garside, R. Defining the process to literature searching in systematic reviews: a literature review of guidance and supporting studies. BMC medical research methodology 2018, 18, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; He, Y.; Jin, S.; Yan, X. Strategic buyer stockpiling in supply chains under uncertain product availability and price fluctuation. Omega 2025, 133, 103283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; He, Y.; Shao, Z. Retailer’s ordering decisions with consumer panic buying under unexpected events. International Journal of Production Economics 2023, 266, 109032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, T.; Pitafi, A.; Arya, V.e.a. Panic buying in the COVID-19 pandemic: A multi-country examination. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 2021, 59, 102387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangwar, M.; Kumar, N.; Rao, R. Consumer stockpiling and competitive promotional strategies. Marketing Science 2014, 33, 94–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billore, S.; Anisimova, T. Panic buying research: A systematic literature review and future research agenda. International Journal of Consumer Studies 2021, 45, 777–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huan, C.; Park, S.; Kang, J. Panic buying: Modeling what drives it and how it deteriorates emotional well-being. Family and Consumer Sciences Research Journal 2021, 50, 150–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, L.; Yuen, K.F.; Fang, M.; Wang, X. A literature review on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on consumer behaviour: implications for consumer-centric logistics. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics 2023, 35, 2682–2703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jazemi, R.; Farahani, S.; Otieno, W.; Jang, J. Review on panic buying behavior during pandemics: influencing factors, stockpiling, and intervention strategies. Behavioral Sciences 2024, 14, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuen, K.; Wang, X.; Ma, F.e.a. The psychological causes of panic buying following a health crisis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2020, 17, 3513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuen, K.F.; Wang, X.; Ma, F.; Li, K.X. The psychological causes of panic buying following a health crisis. International journal of environmental research and public health 2020, 17, 3513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Rajabifard, A.; Sabri, S.; Potts, K.E.; Laylavi, F.; Xie, Y.; Zhang, Y. A discussion of irrational stockpiling behaviour during crisis. Journal of Safety Science and Resilience 2020, 1, 57–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noda, S.; Teramoto, K. A dynamic model of rational “panic buying”. Quantitative Economics 2024, 15, 489–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, R.; Shou, B.; Yang, J. Supply disruption management under consumer panic buying and social learning effects. Omega 2021, 101, 102238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulam, R.; Furuta, K.; Kanno, T. Consumer panic buying: Realizing its consequences and repercussions on the supply chain. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, D. Supply chain resilience: Conceptual and formal models drawing from hormone system analogy. Omega 2023, 127, 103081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, G.; Yuen, K.F.; Wang, X.; Wong, Y.D. The determinants of panic buying during COVID-19. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2021, 18, 3247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prentice, C.; Quach, S.; Thaichon, P. Antecedents and consequences of panic buying: The case of COVID-19. International Journal of Consumer Studies 2022, 46, 132–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavuri, R.; Jaiswal, D.; Thaichon, P. Extrinsic and intrinsic motives: panic buying and impulsive buying during a pandemic. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management 2023, 51, 190–204. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Zhou, Y.; Wong, Y.D.; Wang, X.; Yuen, K.F. What influences panic buying behaviour? A model based on dual-system theory and stimulus-organism-response framework. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 2021, 64, 102484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avi Herbon, K.K. Apportioning limited supplies to competing retailers under panic buying and associated consumer traveling costs 2021. [CrossRef]

- Shima Soltanzadeh, Majid Raffee, G.W.W. Disruption, panic buying, and pricing: A comprehensive game-theoretic exploration 2024. [CrossRef]

- Yoon, J.; Narasimhan, R.; Kim, M.K. Retailer’s sourcing strategy under consumer stockpiling in anticipation of supply disruptions. International Journal of Production Research 2018, 56, 3615–3635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilk, V.; Mat Roni, S.; Jie, F. Supply chain insights from social media users’ responses to panic buying during COVID-19: The herd mentality. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics 2023, 35, 290–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeque Hamdan, Youssef Boulaksil, K.G.Y.H. Simplicity or flexibility? Dual sourcing in multi-echelon systems under disruption 2025. [CrossRef]

- Ana Alina Tudoran, Charlotte Hjerrild Thomsen, S.T. Understanding consumer behavior during and after a Pandemic: Implications for customer lifetime value prediction models 2024. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, R.; Shou, B.; Yang, J. Supply disruption management under consumer panic buying and social learning effects. Omega 2021, 101, 102238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.A.; Chowdhury, M.M.H.; Pappas, I.O.; Metri, B.; Hughes, L.; Dwivedi, Y.K. Fake news on Facebook and their impact on supply chain disruption during COVID-19. Annals of Operations Research 2023, 327, 683–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarraf, S.; Kushwaha, A.K.; Kar, A.K.; Dwivedi, Y.K.; Giannakis, M. How did online misinformation impact stockouts in the e-commerce supply chain during COVID-19–A mixed methods study. International Journal of Production Economics 2024, 267, 109064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arafat, S.; Kar, S.; Kabir, R. Panic Buying: Perspectives and Prevention; SpringerBriefs in Psychology, Springer International Publishing, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Paul, S.K.; Chowdhury, P. A production recovery plan in manufacturing supply chains for a high-demand item during COVID-19. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management 2021, 51, 104–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, C.; Chu, C.; Yang, J. " If you don’t buy it, it’s gone!": The effect of perceived scarcity on panic buying. Electronic Research Archive 2023, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jothilingam, P.; Kalaivani, Y. How Pandemic Has Influenced the Purchasing Behaviour of Consumers. International Journal of Health Sciences 2022, 1986–1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, T.; Paul, S.K.; Shukla, N.; Agarwal, R.; Taghikhah, F. Managing panic buying-related instabilities in supply chains: A covid-19 pandemic perspective. Ifac-papersonline 2022, 55, 305–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aflaki, A.; Swinney, R. Inventory integration with rational consumers. Operations Research 2021, 69, 1025–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, M.; Wang, Q. Developing supply chain resilience through integration: An empirical study on an e-commerce platform. Journal of Operations Management 2023, 69, 477–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Ying, S.; Xu, X. Dual-Channel Supply Chain Coordination with Loss-Averse Consumers. Discrete Dynamics in Nature and Society 2023, 2023, 3172590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeleke, A. Understanding consumer behaviour and its impact on supply chain planning. https://businessday.ng/columnist/article/understanding-consumer-behaviour-and-its-impact-on-supply-chain-planning/, 2024. Accessed: 2025-04-05.

- Su, X. Intertemporal pricing and consumer stockpiling. Operations research 2010, 58, 1133–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltanzadeh, S.; Rafiee, M.; Weber, G.W. Analyzing the impact of panic purchasing and customer behavior on customer purchasing decisions and retailer strategies during disruption. Annals of Operations Research 2024, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Nair, K.; Radhakrishnan, L. Impact of COVID-19 crisis on stocking and impulse buying behaviour of consumers. International Journal of Social Economics 2021, 48, 1794–1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Ma, Y.; He, Z.; Che, A.; Huang, Y.; Xu, J. The impact of consumer price forecasting behaviour on the bullwhip effect. International Journal of Production Research 2014, 52, 6642–6663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Profeta, A.; Smetana, S.; Siddiqui, S.; Hossaini, S.; Heinz, V.; Kircher, C. The impact of Corona pandemic on consumer’s food con-sumption. Int. J. Environ. Res. Pub-lic Health 2021, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, B.J.; Liu, S.S.; Huang, G.Q.; Ng, C.T. How does consumer quality preference impact blockchain adoption in supply chains? Electronic Markets 2025, 35, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dohale, V.; Verma, P.; Gunasekaran, A.; Ambilkar, P. COVID-19 and supply chain risk mitigation: a case study from India. The International Journal of Logistics Management 2023, 34, 417–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, S.K.; Chowdhury, P. Strategies for managing the impacts of disruptions during COVID-19: an example of toilet paper. Global Journal of Flexible Systems Management 2020, 21, 283–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicola, M.; Alsafi, Z.; Sohrabi, C.; Kerwan, A.; Al-Jabir, A.; Iosifidis, C.; Agha, M.; Agha, R. The socio-economic implications of the coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19): A review. International journal of surgery 2020, 78, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taghikhah, F.; Voinov, A.; Shukla, N.; Filatova, T. Exploring consumer behavior and policy options in organic food adoption: Insights from the Australian wine sector. Environmental science & policy 2020, 109, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, T.; Paul, S.K.; Shukla, N.; Agarwal, R.; Taghikhah, F. Supply chain resilience initiatives and strategies: A systematic review. Computers & Industrial Engineering 2022, 170, 108317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Yao, J. Intertwined supply network design under facility and transportation disruption from the viability perspective. International Journal of Production Research 2023, 61, 2513–2543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belhadi, A.; Kamble, S.; Jabbour, C.J.C.; Gunasekaran, A.; Ndubisi, N.O.; Venkatesh, M. Manufacturing and service supply chain resilience to the COVID-19 outbreak: Lessons learned from the automobile and airline industries. Technological forecasting and social change 2021, 163, 120447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okeagu, C.N.; Reed, D.S.; Sun, L.; Colontonio, M.M.; Rezayev, A.; Ghaffar, Y.A.; Kaye, R.J.; Liu, H.; Cornett, E.M.; Fox, C.J.; et al. Principles of supply chain management in the time of crisis. Best Practice & Research Clinical Anaesthesiology 2021, 35, 369–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, S.J.; Diaz, M.; Arnaboldi, M. Understanding panic buying during COVID-19: A text analytics approach. Expert Systems with Applications 2021, 169, 114360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liren, X.; Junmei, C.; Mingqin, Z. Research on panic purchase’s behavior mechanism. Innovation and Management 2012, 1332–1337. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, A.; Pellerin, R.; Lamouri, S.; Lekens, B. Managing demand volatility of pharmaceutical products in times of disruption through news sentiment analysis. International Journal of Production Research 2023, 61, 2829–2840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurihara, S.; Maruyama, A.; Luloff, A. Analysis of consumer behavior in the Tokyo metropolitan area after the Great East Japan Earthquake. Journal of Food System Research 2012, 18, 415–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keane, M.; Neal, T. Consumer panic in the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of econometrics 2021, 220, 86–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, T.; Paul, S.K.; Agarwal, R.; Shukla, N.; Taghikhah, F. A viable supply chain model for managing panic-buying related challenges: lessons learned from the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Production Research 2024, 62, 3415–3434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindan, K.; Sethi, S.P.; Cheng, T.; Lu, S.F. Designing supply chain strategies against epidemic outbreaks such as COVID-19: Review and future research directions. Decision Sciences 2023, 54, 365–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, B.d.F.O.; Fontainha, T.C.; Leiras, A. Looking back and forward to disaster readiness of supply chains: a systematic literature review. International Journal of Logistics Research and Applications 2024, 27, 1569–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montoya-Torres, J.R.; Muñoz-Villamizar, A.; Mejia-Argueta, C. Mapping research in logistics and supply chain management during COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Logistics Research and Applications 2023, 26, 421–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durugbo, C.M.; Al-Balushi, Z. Supply chain management in times of crisis: a systematic review. Management Review Quarterly 2023, 73, 1179–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Li, J.; Sun, Y.; De Souza, R. Supply chain resilience enhancement strategies in the context of supply disruptions, demand surges, and time sensitivity. Fundamental Research 2025, 5, 496–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsao, Y.C.; Raj, P.V.R.P. Product substitution with customer segmentation under panic buying behavior. Scientia Iranica 2020, 27, 2514–2528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurnani, H.; Mehrotra, A.; Ray, S. Supply chain disruptions: Theory and practice of managing risk; Springer, 2012. [CrossRef]

- Jain, N.; Girotra, K.; Netessine, S. Recovering Global Supply Chains from Sourcing Interruptions: The Role of Sourcing Strategy. Manufacturing & Service Operations Management 2022, 24, 846–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsao, Y.C.; Raj, P.V.R.P.; Yu, V. Product substitution in different weights and brands considering customer segmentation and panic buying behavior. Industrial Marketing Management 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haraguchi, M.; Neise, T.; She, W.; Taniguchi, M. Conversion strategy builds supply chain resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic: A typology and research directions. Progress in Disaster Science 2023, 17, 100276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wu, Y.; Li, Q. Production Change Optimization Model of Nonlinear Supply Chain System under Emergencies. Sensors 2023, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega, D.; Arvidsson, A.; Saiah, F. Resilient Supply Management Systems in Times of Crisis. International Journal of Operations & Production Management 2023, 43, 70–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Dong, C. Government regulations to mitigate the shortage of life-saving goods in the face of a pandemic. European Journal of Operational Research 2022, 301, 942–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, T.; Shou, B.; Guo, P. Managing Panic Buying with Bayesian Persuasion. Working paper 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Soltanzadeh, S.; Rafiee, M.; Weber, G.W. Disruption, panic buying, and pricing: a comprehensive game-theoretic exploration. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 2024, 78, 103733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, R.; Wang, Y.; Bao, L. Managing consumers’ panic stockpiling behavior under supply disruption risk: Price increase vs. quota policy. Journal of Industrial Engineering and Engineering Management 2025, 39. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Salido, J.D.; Gagnon, E.; et al. Small Price Responses to Large Demand Shocks. In Proceedings of the 2015 Meeting Papers. Society for Economic Dynamics, 2015, number 1480.

- Muzamil, A.Z.A.; Pyeman, J.; Mutalib, S.b.; Azma binti Kamaruddin, K.; Abdul Rahman, N.b. Enabling retail food supply chain, viability and resilience in pandemic disruptions by digitalization–a conceptual perspective. International Journal of Industrial Engineering and Operations Management 2025, 7, 175–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hoek, R. Research opportunities for a more resilient post-COVID-19 supply chain–closing the gap between research findings and industry practice. International journal of operations & production management 2020, 40, 341–355. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Q.; He, Y.; Shao, Z. Retailer’s ordering decisions with consumer panic buying under unexpected events. International Journal of Production Economics 2023, 266, 109032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrino, R.; Gaudenzi, B. Impacts and supply chain resilience strategies to cope with COVID-19 pandemic: a literature review. Supply Chain Resilience 2023, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Wu, G.; Wang, Y. Retailer’s emergency ordering policy when facing an impending supply disruption. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ovezmyradov, B. Product availability and stockpiling in times of pandemic: causes of supply chain disruptions and preventive measures in retailing. Annals of Operations Research 2022, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sterman, J.D.; Dogan, G. “I’m not hoarding, I’m just stocking up before the hoarders get here.”: Behavioral causes of phantom ordering in supply chains. Journal of Operations Management 2015, 39, 6–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, T.; Pitafi, A.H.; Arya, V.; Wang, Y.; Akhtar, N.; Mubarik, S.; Xiaobei, L. Panic buying in the COVID-19 pandemic: A multi-country examination. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 2021, 59, 102357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheu, J.B.; Choi, T.M. Proactive hoarding, precautionary buying, and postdisaster retail market recovery. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management 2021, 70, 4263–4277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Academic platform | Keywords | Number records |

|---|---|---|

| Web of Science (WoS) | Supply disruption and panic buying | 77 |

| Web of Science | Panic buying and supply chain management | 137 |

| Web of Science | Managing consumer panic buying behavior | 87 |

| Distinct records from WoS | 251 | |

| Google Scholar (GS) | Supply disruption and panic buying and supply chain management | 2260 |

| Refined records from GS | 236 |

| Author (Year) | Research Focus | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Islam et al. [13] | Panic buying across countries during COVID-19 |

|

| Gangwar et al. [14] | Promotional strategies and rational stockpiling |

|

| Li et al. [11] | Strategic stockpiling under price fluctuations |

|

| Xu et al. [12] | Retailer ordering under panic buying |

|

| Zheng et al. [23] | Social learning effects and inventory management |

|

| Ivanov [25] | Supply chain resilience modeling |

|

| Yuen et al. [19] | Psychological mechanisms of panic buying |

|

| Factors | Key Examples & Findings | Sample reference |

|---|---|---|

| Information Asymmetry |

|

[20,30] |

| Social Influence |

|

[31,36] |

| Network Diffusion |

|

[19,37,38] |

| Individual Psychology |

|

[20,39,40,41] |

| Strategies | Interventions | Concrete Measures | Sample References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alleviating Consumer Panic Psychology | Psychological Intervention and Control Restoration | Encourage community engagement to enhance self-efficacy. | [62] |

| Transparency and Rational Guidance | Use "Purchase As Needed" labels to nudge behavior. | [63] | |

| Avoid media sensationalism of shortages. | [65] | ||

| Technology and Sentiment Analysis | Leverage AI for consumer sentiment analysis and demand forecasting. | [64] | |

| Flexible Supply and Adjustments | Dynamic production capacity adjustment. | [43,86,87] | |

| Enhancing Supply Chain Elasticity and Inventory Management | Quotas and Priority Management | Enforce purchase limits on essentials. | [24,88] |

| Customer segmentation for priority access. | [73] | ||

| Logistics and Supplier Networks | Build emergency procurement channels. | [74,89] | |

| Diversify supplier networks to reduce dependency risks. | [27] | ||

| Production conversion and expansion; Digitization | [77,78,79] | ||

| Government-Retailer Collaboration | Government Actions | Implement price controls during crises. | [74] |

| Establish joint emergency reserves. | [39] | ||

| Issue authoritative supply chain statements. | [62] | ||

| Retailer Measures | Adopt dynamic pricing and real-time inventory platforms. | [27] | |

| Pre-stock key goods to curb early panic. | [36,66] | ||

| Implement purchase limit and adjust price | [83] |

| Dimensions | Specific Impacts | Concrete Expression | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Supply Chain Performance |

Insufficient flexibility | Demand response lags Obstructed global circulation |

[33] |

| Cost increase | Rising shortage costs, inventory costs, transportation costs Increased bullwhip effect |

[43];[90];[91] | |

| Resource mismatch | Overstocking leads to waste of resources; Irrational demand leads to waste of energy and raw materials |

[26] | |

| Consumer Welfare |

Economic burden | Price increases Additional cost increases Wasteful spending |

[67];[43];[24] |

| Psychological pressure |

Social anxiety spreads to fuel panic Consumers’ long-term trust in markets collapses |

[33];[43] | |

| Social inequality | Difficulty in accessing necessities for disadvantaged groups Policies (limiting purchases/high prices) disproportionately affect low-income populations |

[90];[26] | |

| Two-way Interaction Mechanism |

The "Shortage→ Rush→Shortage" cycle |

Supply chain disruptions trigger consumer panic buying, further exacerbating inventory pressures |

[26] |

| Retailer behavioral conditioning | Active stockpiling may temporarily ease supply pressures, but excessive stockpiling prolongs recovery times |

Rahman et al. [43], Zheng et al. [83] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).