1. Introduction

A large number of developing countries share a particular characteristic associated with the continued lack of decentralization, both political and fiscal, due to a series of inefficiencies that are naturally linked to a lack of public policies with characteristics that could effectively establish themselves as the main driver of development in these countries. Thus, the lack of a set of public policies that are above all inclusive has a major influence on the capacity that countries should have from the outset in terms of their own prosperity in particular. These characteristics have been very different from those of developed countries, but there are strong reasons that explain the marked poverty in countries where there is no decentralization, especially fiscal decentralization as the main driver of economic transformation. Countries that still have non-decentralized regimes, for example, tend to increase inefficiency in terms of their capacity to distribute wealth to most regions, which should promote greater sustainability in terms of plausible and inclusive growth, yet are of great relevance to the affirmation of the levels that end up being related to the capacity of these regions to actually grow significantly.

However, the reasons for both economic and political failure in most developing countries, or precisely in poor countries, are in fact taken into account precisely when considering how regions are in fact continuously impoverished. Evidence shows that causal poverty is mainly associated with levels of decentralization. Countries with a high degree of political, administrative, and economic centralization tend to have an accumulation of power, but centralized policies tend to further promote the inability of these regions to address structural imbalances. The centralization of policies in a single region, however, leads to some inefficiencies that naturally contribute to the breakdown of political capacity, especially the political capacity to effectively introduce greater efficiency and adjustment of highly relevant public policies that contribute more to the affirmation of the regions themselves. Countries with significantly centralized power lead to an increase in causal poverty due to the inefficiencies of their institutions. However, these institutions end up being exclusive in nature and without the actual capacity to introduce the best efficiencies of the adjusted capacity for wealth distribution. Inefficiencies arising from the mismatch between institutions and public policies tend to contribute to continued underdevelopment, strongly in line with the need for non-integration of economic and political structures as a greater measure to ensure that, in the short term, there can be inclusion of public policies aimed particularly at increasing the growth capacities of the respective institutions and a set of actions that should, however, promote a more inclusive policy and, above all, one that is in line with the institutions.

Thus, there is in fact a significant and causal increase in extractive institutions, which contribute to an affirmation of the non-existence of needs related to the economic and regional structure that each particular region presents. With significantly centralized policies, regions become de facto inefficient in their ability to ensure plausible growth in regional capacities. The context of a centralized regime actually increases the capacity to guarantee, on the one hand, extractive public policies, but these are strongly supported by a significant increase in the functional wear and tear of authorities and political institutions. Evidence shows that there is no capacity to respond in line with the objectives that most authorities tend to present for improving the distribution of wealth. The functional erosion of authorities and political institutions has been the main reason for the failure to perceive public policy integration as a major driver of prosperity. However, ensuring that this prosperity actually exists will still depend on the fact that these public policies as a whole cannot actually interfere with the capacity for inclusion. The functional erosion of both authorities and political institutions arises from certain criteria that naturally contribute to the failure to affirm the need for inclusion. However, both political inclusion and fiscal inclusion, or rather the lack of fiscal inclusion, are likely to result in certain inefficiencies, for example.

The functional erosion of authorities occurs from a perspective that promotes greater imbalances between public policies and political institutions. Thus, decisions in the context of political centralization are nevertheless characterized by the existence of some ineffective public policies that lack sufficient justification and should naturally reflect a set of specificities of economic and regional growth necessary for a better affirmation of the respective regions. Regions with political centralization, such as capitals, end up defining a greater capacity for centralization of public policies. On the other hand, these regions represent the power of exclusion from political and economic institutions, which naturally tend to diverge from other regions, where they promote an inability to align central and decentralized regions. Naturally, centralized regions tend to centralize fiscal policy, where the distribution of tax revenues to other regions is characterized by continuous inefficiency associated with the failures of these regions in particular. Centralized regions concentrate the economy and public finances, and a large part of economic activity is in fact centralized with the aim of translating unstructured imbalances into the implementation of inclusive and efficient public policies, especially from a structural point of view. These are regions where the capacity for inclusion is in fact much lower than in other regions where decentralization is non-existent.

Significantly poor countries differ greatly in certain situations, especially those related to the lack of political decentralization, which leads to the inefficiency of inclusive democracies and democratic plurality that are significantly relevant to the affirmation of societies and their respective regions, particularly in the presence of some regions whose economic and political activities are significantly dependent on regions where there is greater capacity for political centralization. The lack of decentralization inhibits democracy and erodes political institutions, plausibly leading to political institutions failing to contribute to the development and sustainable balance of public policies adopted with the capacity to translate, for example, that there is in fact plausible growth between institutions and public policies. These are inefficient and unable to respond in the short, medium, and long term, as is seen in most institutions and regions where political institutions lack inclusive democracy. On the other hand, the lack of political and administrative decentralization significantly affects the regions in terms of governance. For example, the governance of most regions is still exclusive and lacks the capacity to promote greater political and democratic inclusion, which should contribute to the affirmation of other particularities associated with the governance needs of the regions. The lack of governability is, however, likely to be associated with a set of public policies that have the potential to bring about substantial improvements that highlight the growth capacity that the regions in particular should be able to achieve.

The lack of local governance as a result of ungovernability is strongly associated with the fact that there is, for example, interaction between public policies and a decisive set of highly effective policies to suggest better sustainable growth in the regions. However, regions tend not to contribute to improving public policies, which should nevertheless converge towards the inclusion of efficient public policies with greater capacity for residence. Thus, the existence of centralized regions ultimately translates into weak governance capacity associated with the continuous failures of the policies adopted as characteristics that include other policy measures that are significantly full in terms of inclusion capacity and the capacity of these regions to add greater dynamism, which has to do, for example, with the fact that there are, however, better inclusive public policies and greater dynamism in the functioning of regional institutions regional policies.

Democracy in particular is largely characterized by the existence of a significant set of capacities for inclusion in different public policies, especially policies that are more relevant to the acceptance of different capabilities and particularities associated largely with growth dynamics, which may be provided by most institutions and regions in response to different regional units, with an emphasis on regional political inclusion.

In the context of political decentralization, political and democratic institutions converge to improve their ability to ensure the better functioning of political institutions. Democracy is significantly inclusive when there is greater participation by its main actors. For example, institutions with a highly relevant inclusive democracy are in fact associated with a greater capacity for existence, for example, at different levels of political and democratic participation. Democratic participation as the best viable capacity to understand how political institutions contribute, however, to a better affirmation of the capacity of these regions in particular.

Decentralization should contribute to economic dynamism and the dynamism of political institutions, as suggested by most countries where there is in fact a set of decentralized subunits, as is the case with subnational units, naturally considering decentralization through a federalist model. however, some particularities do contribute to a better affirmation of regional public policies, as suggested by regions where decentralization is nevertheless adopted through a federalist model. This is naturally different from decentralization through a model of local authorities where, from the outset, there is a relative inefficiency of decentralized units. decentralization through local authorities is not sufficiently capable of translating significant improvements in the capacity that these regions in particular actually have. However, there are some limitations in a decentralization model with local authorities, so much of the decentralization actually suggests that there is still better decentralization in the presence of a decentralization model with federalism. Some effects on federalism are analyzed in detail in (Eaton, K. 2013). According to the authors, Latin America has undergone a significant set of transformations in recent years, particularly in relation to levels of decentralization. The federalism adopted by India was naturally susceptible, on the one hand, to guaranteeing a significant set of changes that could in fact suggest a better distribution of power and greater channeling of resources and wealth, in particular by the authorities, as a better response to different inclusive policies, analyzed in (Biela, J., & Hennl, A. 2010). In (Stepan, A. C. 1999), they reinforce the idea of the existence of better political and democratic participation in the context of a significantly federated state. Thus, in the presence of effective decentralization, a large part of the subnational units do in fact receive a set of transfers from the union, however, the different transfers to these regions promote and drive economic transformation through a set of companies that are located in these particular regions, naturally because they are in fact regions with a greater capacity to attract investment and because there is a greater existence of a plausible set of economic institutions converging to strengthen their respective regions, in (Feld, L. P., Zimmermann, H., & Döring, T. 2004), significantly reinforce this idea and with greater capacity for regions to actually contribute to greater sustainable growth in their respective regions in particular. However, this particularity ultimately converges on the perception of the regions' own growth, where regions that tend to show a greater capacity to contribute may, for example, remain strongly cohesive, in being able to guarantee economic stability through the capacity of the regional structure. Thus, fiscal decentralization, as suggested by a federalist model, may in fact contribute to the channeling of different tax revenues by the authorities. However, fiscal federalism can in fact lead to substantial improvements in regional growth and the functioning of economic institutions in response to a possible economic and fiscal capacity in regions where this great particularity of effective contribution actually exists, especially since it is naturally in line with the objectives of sustainable regional growth, yet plausible in terms of ensuring plausible and lasting growth. This evidence can in fact be found in (Hamlin, A. P. 1991), reinforcing the idea of fiscal decentralization associated particularly with stability and better economic performance.

Unitary countries, which are naturally non-federal countries, translate territorial inefficiencies through territorial discrimination. However, the discriminated territories tend, for the most part, not to have the main inclusive policies channeled and the development of their respective territories in particular. Discrimination, on the other hand, promotes structural inefficiency in the regions, thus regions with high poverty rates and less capacity to actually channel sustainable growth and achieve an optimal level of resilience. However, discriminated territories tend to have discriminatory public policies, mainly associated with the continuous failure of different policies and institutions. However, these institutional inefficiencies and the very existence of poor regions themselves contribute to this situation. Regions with the highest levels of territorial discrimination naturally converge towards regional asymmetries, which can be plausibly quantified through the various differences between metropolitan regions and other discriminated regions. However, metropolitan regions still have control over decisions, considering, on the other hand, the existence of a set of institutions with characteristics of political centralization and centralization of other institutions. In (Congleton, R. 2006), they particularly show the existence of these levels of regional asymmetries, considering them, on the other hand, as a regional failure. The transformations in the different regions of Latin America have led to greater transformations associated particularly with the perception of the different other inclusive policies. However, this evidence is plausibly supported in (Escobar-Lemmon, M. 2001).

Some evidence shows precisely that there is a set of improvements and efficiencies in the different new federalist models. However, the approach to federalism soon received special attention from the authorities, especially as a mechanism whereby these different models could, for example, contribute to greater capacity for inclusion. However, many regions paid special attention to the perception of the optimal models to be implemented, especially considering decentralization through a federalist model as the best possible route to democratic inclusion at various levels of political and democratic action. Decentralization does indeed give decentralized states better implementation of public policies, mainly through fiscal autonomy and political and administrative autonomy granted to the regions, as is best measured by a very inclusive characteristic in the practical determination of different regional public policies, in (Brown, G. K. 2009), explore with some relevance the effects of enhanced autonomy through inclusive public policies and with a greater capacity to bring about significant changes promoted by different transformations.

A large part of decentralized regions naturally gain a degree of autonomy that enables them to effectively converge with local growth and development, as suggested by the approaches of (Bardhan, P. 2006). However, territorial units with greater territorial decentralization nevertheless converge towards the inclusion and prosperity of their respective regions. The dynamics suggested by decentralization are naturally capable of altering and translating the necessary transformations, naturally leading to balanced and sustainable development in developing regions. Sustainable development in these regions is likely to occur when the regions tend to channel the degree of development and economic growth in the best possible way, driven by regions whose institutions have greater governance efficiency and greater efficiency in the use of productive resources used by most regional institutions. Thus, intergovernmental competitiveness between states can in fact be evidenced through the application of a set of inclusive public policies, which are nevertheless relevant to a better understanding of how regional authorities should conduct different public policies. Intergovernmental competitiveness and regional competitiveness between different states provide another particularity regarding the different capacities conferred by the regions. However, states may in fact take relatively greater advantage of this, in comparison with other regions. Thus, intergovernmental competitiveness may, for example, arise through the different levels that have to do with the different levels of fiscal decentralization. Naturally, in this way, decentralized regions are still able to channel and introduce greater efficiency in the equitable distribution of wealth. On the other hand, the capacity to generate wealth may initially be directed towards the levels of wealth produced by the different states. The federalist model largely gives subnational regions greater autonomy in terms of territorial and regional competitiveness. Regions affected by the effective distribution of different regional public policies tend, for example, to channel more sustained and stable growth.

Some examples show that fiscal decentralization does indeed accelerate economic transformation. The example of India can contribute to a better understanding of the balance between public policies and the respective policy, naturally considering infrastructure levels as the best driver for channeling regional public policies. However, the fiscal decentralization promoted by India shows precisely that there is greater acceleration of political capacity and capacity for improvement with the strengthening of the regions, as analyzed with some relevance in (Rao, M. G. 2002). There is a significant increase in improvements with regard, for example, to the great capacity of regions with attractiveness and regions that tend to channel some distinct particularities, especially related to fiscal federalism, especially considering fiscal decentralization as the main factor responsible for the capacity of regions to translate some plausible effects that, from the outset, can in fact channel a greater part of resources, especially to drive the necessary transformations, However, these transformations are inclusive in nature.

2. Federalism Around the World

The federalist model adopted by most countries has its own distinct characteristics, which are very relevant in terms of their ability to guarantee economic and fiscal decentralization on the one hand, and on the other hand, political and administrative decentralization influenced by the implementation of a federalist model shows how different national sub-levels should influence the attraction of a set of investments and be capable of including different decentralized models, particularly considering the existence of models with inclusive characteristics that determine, for example, the ability of institutions to define a set of actions that should be introduced, both political participation and economic participation, especially economic participation through fiscal decentralization, reflect some practical efficiencies that could complement other regions. However, regions tend to guarantee the causal existence of regional development, which is in fact a higher priority at the local level and should channel a set of actions capable of transforming a large part of the regions.

The United States of America was in fact the first to implement a federalist model in 1789, with decentralization originally inherited from the former administrative division of the English colonial regime, with the 13 colonies determining the interaction between decentralization and public policies. Thus, the implementation of federalism in the United States of America brought about a certain dynamic, particularly in relation to the territorial cohesion of the regions. The country had a division that took into account the different federated units, considering the territorial dimension, with 50 states and significant decentralization of judicial and fiscal power. American federalism, being in fact a pure federalism, ensures that there is greater interaction between the different significantly decentralized subnational units. Thus, there is still a separation of powers between the different subnational units, such as states and other intraregional entities, but there is in fact a separation between the different levels of judicial and local power, with the separation of powers being the best way to channel the different public policies capable of transforming the regions. American federalism is naturally an example of how fiscal decentralization is strong enough to ensure greater prosperity, associated with aspects related to the respective economic transformations. Most of the states in the United States have benefited from plausible and sustainable growth, which is particularly promising, biased towards inclusive public policies that have been significantly adopted as prosperity for the economy and prosperity for the respective regions. However, economic and industrial development has undergone profound transformations, which have naturally always been in line with the degree of regional growth and, above all, institutional growth, which have nevertheless made it possible to channel better economic performance. However, there is a particular feature that relates regions as perspectives that tend to converge with regions that show better levels of sustainable and inclusive development.

The federalist model adopted by the United States of America was, however, a driving force for other models that followed and led to the expansion of federalist nations around the world. Several countries followed suit in adopting the federalist model as a form of government with significant powers of decentralization in different areas.

Other countries traditionally had a confederation during their formation, such as Switzerland, which later, in 1848, transformed its confederation into a federal state. Thus, the constitution established decentralization based on federalism with 26 subnational units designated as cantons, with the cantons being equivalent to the different subnational units and the states naturally conforming to American federalism. A very particular feature of Swiss federalism is, however, associated with the preservation of cultural identity, especially the distinct ethnolinguistic diversities and preservation of regional interior culture. The preservation of power is in fact a major driving force for the regions. On the other hand, Canada adopted a federal system in 1867, maintaining the different provinces as subnational units, established by the constitution, which sets out the different particularities such as the form of decentralization for the subnational units designated as provinces and a central government. However, the constitution establishes the existence of an organization and decentralization by province. The combination of the parliamentary system and federalism was in fact significantly adopted by Canada, considering, on the other hand, the separation between the executive and legislative powers in various subnational units. However, this is a feature that has had a major impact, especially considering the existence of a combination of two distinct languages, for example, French and English, thus preserving the cultural characteristics of the subnational units. In contrast, Australia adopted a federal system in 1901. Currently, the federation has six subnational units, naturally the states that give greater importance to autonomy and separation of powers to each territory. The adoption of Australian federalism differs from Canadian federalism, where there is still a relatively higher degree of concentration of powers. However, Australian federalism has been combined with the American federalist model, which grants greater autonomy to subnational units. On the other hand, the federalist model adopted by the United States has greater decentralization and ensures greater political and economic competitiveness between regions. The federal parliamentary system introduced by Australia was much more relevant than any other federal parliamentary system adopted in another federation. For fiscal harmonization, there were naturally significant increases in new taxes, such as VAT, replacing other existing taxes. On the one hand, this served as the basis for the tax system in particular, as a large part of the taxes on goods and services collected by most territories are in fact distributed throughout the territory, which particularly provides better fiscal harmony with regard to tax revenues.

In 1920, Austria formally adopted a federalist model, with some modifications in 1929 and 1945. Austria's cultural base allows it to enjoy a particular homogeneity characterized by the existence of a cultural base founded above all on the cultural capacity of its respective regions. Unlike other federalist countries, Austria has greater legislative centralization, with a parliamentary federal government model, but with a chancellor in charge. The federal legislature naturally adopts a bicameral system. Germany introduced federalism in 1949, initially with 11 subnational units. After reunification, the German federation came to have 16 subnational units. German federalism adopts the bicameral system, with the government led by a chancellor and the president elected through an electoral college. After independence in 1947, India adopted federalism in 1950. With diversity between regions and, above all, multiculturalism and multi-ethnicity, Indian federalism is much more complex than other federal systems already in place, differing from the federal models adopted in the United States of America, Canada, Switzerland, and Austria. The constitution confers three complex legislative powers, such as exclusive legislative power, exclusive provincial legislative power, and intergovernmental legislative power, where there is greater competition between the different powers. On the other hand, the United Mexican States adopted the federalist model in 1917, naturally with 31 states as subnational units plus an autonomous federal district. However, the federalism followed by Mexico effectively presents a decentralization structure identical to that found, for example, in countries such as the United States of America, particularly emphasizing the autonomy of the regions. In Mexican federalism, the president of the republic is granted a set of powers through the constitution of the federal republic, which are characterized by being discretionary from the outset. Thus, much of the de facto power is exercised in the states, where it is characterized by greater autonomy and, on the other hand, greater exercise of power by the authorities. However, as in most federalist countries, Congress is bicameral, and deputies and senators converge on certain points, particularly those related to the prevention of corruption. In 1963, Malaysia introduced a federalist model with 13 states, which largely grant de facto autonomy to the regions, despite presenting a complex federalist system. However, the federation experienced rapid growth, driven particularly by economic transformation through fiscal decentralization.

Inspired by the North American federalist model, Brazilian federalism was based on this model to establish a federal republic composed of 26 states and 5,500 municipalities. With a de facto greater predominance of subnational governments, the transfer of powers is effected through the states, which, however, have decision-making powers that naturally promote greater interaction with other regions. Some changes made may in fact have led to greater intergovernmental and interstate relations. Belgium, for example, adopted the federalist model in 1993, with three distinct levels of federalism, with a federal government, 6 regions, community and local governments. Belgium has significant ethnolinguistic diversity, which is why the councils are responsible for cultural diversity and education. The levels affected by decentralization, at the regional and community council levels, are in fact relevant and contribute particularly to the sharing and exercise of local power.

However, in most federalist countries, these have the major characteristic of being able to present a particularly significant degree of decentralization, associated in particular with greater political participation, naturally considering the greater political inclusion and democratic plurality provided by the constitution. This is the case in most federal republics, such as the North American federations and the Brazilian federation, which in fact have greater democratic plurality, strongly driven by their political institutions. Thus, the federalism adopted by the Russian Federation is significantly different from other federations. Russia adopted it in 1993, with 89 constituent units. in practice, Russian federalism has distinct characteristics that have to do above all with its failure to implement the federalist model in particular, as is in fact the case in reality. For the most part, the actions of the Russian government show a significantly centralized government, naturally contradicting the principles of decentralization, with a bicameral parliamentary system and an elected president with powers that guarantee him greater authority over the other regions. Many nations have for years implemented the federalist system as the best form of government and, above all, the one that best guarantees political and administrative decentralization in most regions. Argentina, for example, implemented the federalist system in 1994, with 23 provinces and one autonomous district. Most provinces, however, have greater decentralization and autonomy with their respective constitutions and governments, while also adopting a bicameral system. Ethiopia implemented the federal system in 1995. The Ethiopian Federation, for example, has a wide ethnic and linguistic diversity, which is most evident in the 12 established regions. Each of these regions has its own government elected by the local population, with significantly autonomous institutions and greater cohesion between regional public policies. Another successful example of the implementation of the federal system is Nigeria, established in 1999, with 36 states plus a federal district, which is also the capital of the Federation. The federalism adopted by Nigeria has significantly galvanized the economy and allowed for greater acceleration in economic transformation. The states in particular represent the third level of decentralization, with the National Assembly adopting a bicameral model with 360 seats, with the Senate having one representative from each state. Despite the greater complexity that exists in each state, the constitution of the Republic naturally confers significant powers that allow each state greater autonomy over its regions. Most federations, however, Nigeria is in fact more dependent on the oil sector than other federal states, so naturally the producing states receive a larger per capita share of local production.

As with the Russian Federation, the Republic of Venezuela adopted a federalist system in 1999, but in practice this is not particularly plausible, Venezuela has a federalism with extreme centralization of power, which on the one hand significantly increases governance inefficiencies and institutional inefficiency. Naturally, most institutions in federalist countries such as Venezuela and Russia do not function as they should, being significantly different from American federations and the Brazilian Federation from the outset. Thus, corruption rates in the Russian Federation and the Venezuelan Federation are significantly higher. In (Watts, R. L. 1999), they explore in greater detail the federalism adopted by most countries in the federalist world. A large number of countries that have had to adopt the federalist model naturally had some relevant considerations, which have to do, for example, with some characteristics that initially determine the different levels of political capacity for implementing federalism. However, these characteristics can be broadly quantified in terms of the population's acceptance of a new federalist model. Resistance to change can be a particularly crucial and relevant factor in the application of the model, so the authorities must analyze the details that could influence its implementation. For example, characteristics such as the units necessary for implementation or conversion of existing units may nevertheless drive the formation of different federalist models. The transformation to a federalist model requires particular attention to be paid to the merger of some regions, which presupposes a loss of cultural and geographical identity for those regions. On the other hand, regions may in fact lose their geographical hegemony when merged. If policymakers consider reducing the number of subnational units, they should, for example, take into account the capacity of these regions to actually transform the regions. Most federated countries have a considerable number of subnational units, which are very relevant and important for a better understanding of the regions and how they can ensure, for example, greater capacity for growth. In most cases, there are more than 20 subnational units, and in some cases, some federations have decided to increase the number of subnational units. For example, in

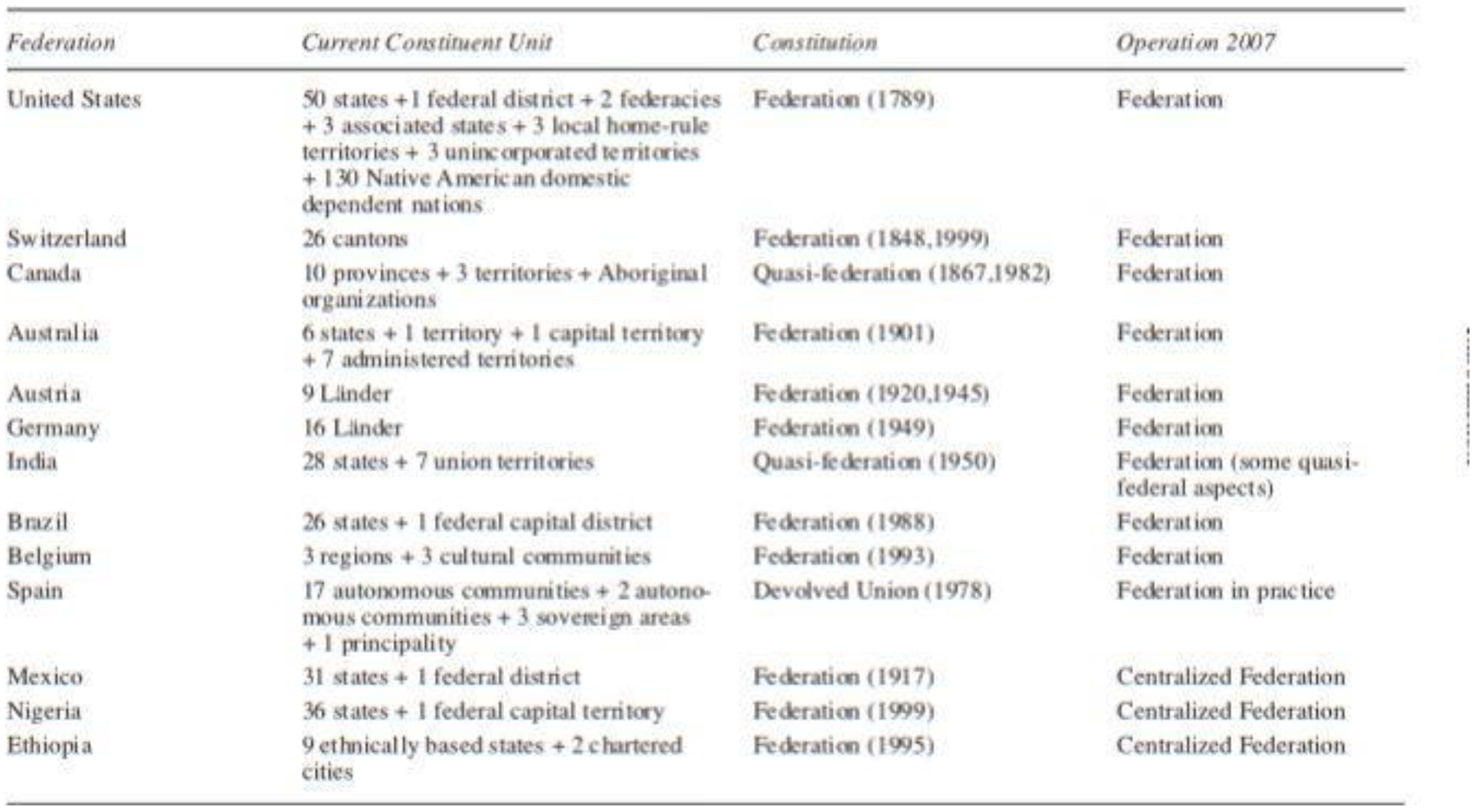

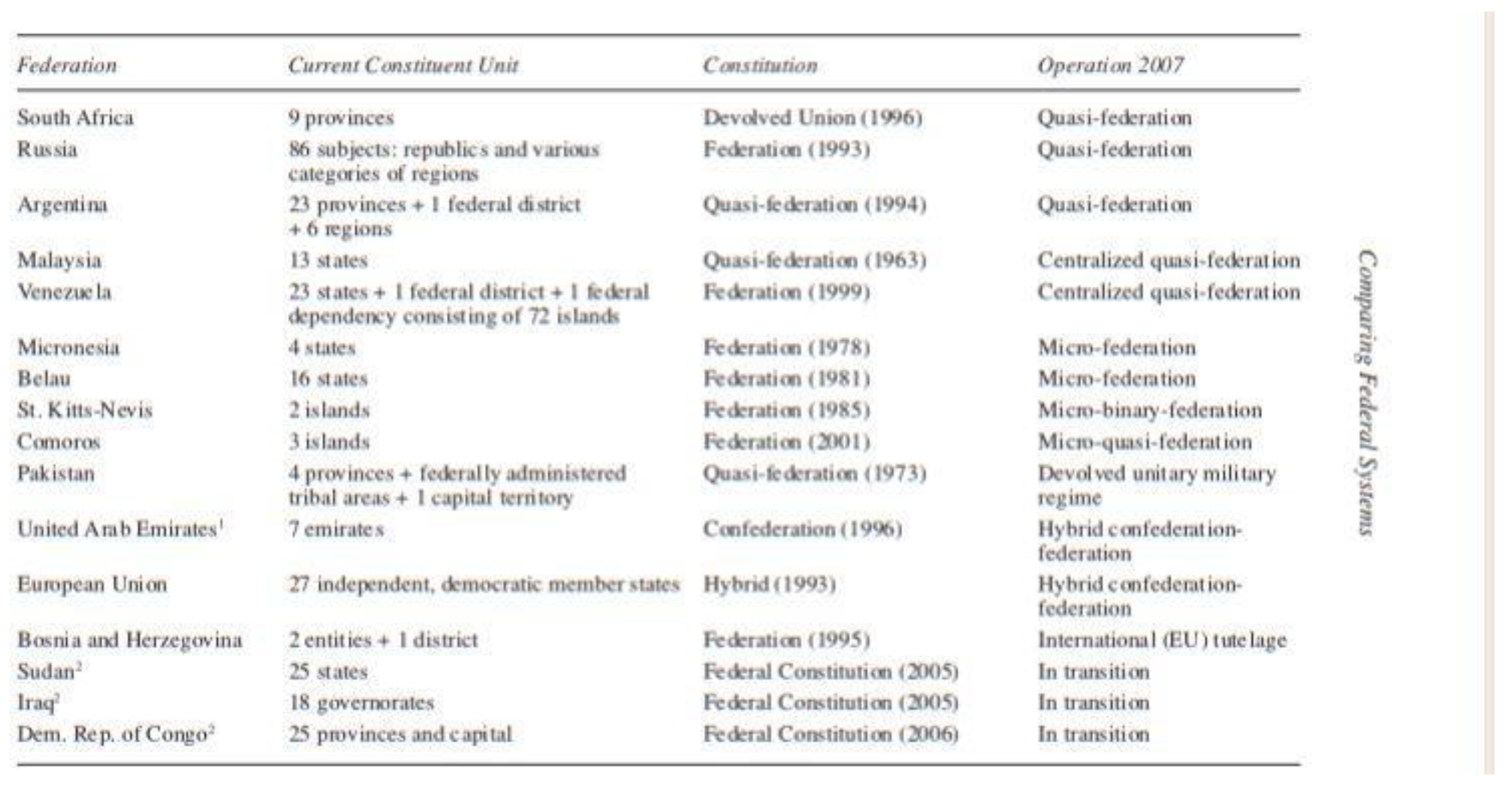

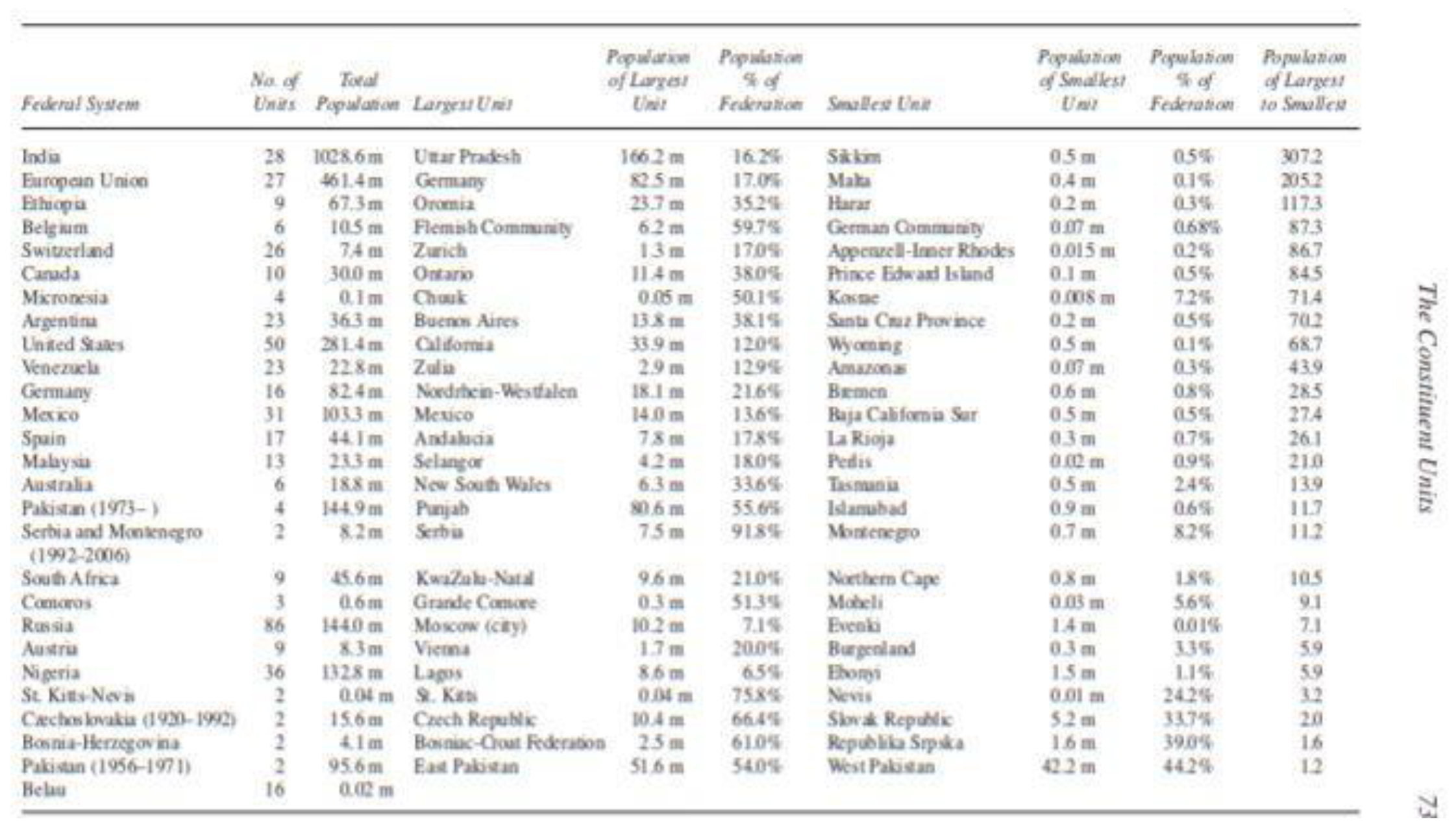

Figure 1, this distribution of subnational units is effectively distributed.

Figure 2, for example, highlights some particularly relevant aspects characterized by the implementation of federal constitutions over the years. Thus, for most federalist countries, their particular trajectory is illustrated by their respective subnational units and the way these regions function, although to a large extent with their own particular characteristics.

Figure 2.

Constituent Characteristics of Federalist Nations. Notes: The figure highlights in particular the constitution of most federal states and some quasi-federal states. Source: Watts, R. L. (1999).

Figure 2.

Constituent Characteristics of Federalist Nations. Notes: The figure highlights in particular the constitution of most federal states and some quasi-federal states. Source: Watts, R. L. (1999).

Figure 3.

Constituent Characteristics of Federalist Nations. Notes: The figure highlights in particular the constitution of most federal states and some quasi-federal states. Source: Watts, R. L. (1999).

Figure 3.

Constituent Characteristics of Federalist Nations. Notes: The figure highlights in particular the constitution of most federal states and some quasi-federal states. Source: Watts, R. L. (1999).

3. Implications of the Federalist Model

The transformation from unitary states to federalist states has strong implications that determine the authorities' capacity for acceptance, considering, of course, that the transformations have in fact been unlikely to be implemented due to the great inefficiency of the regions and the inefficiency of a set of institutions that are not characterized by plausible inclusion, but which are nevertheless possible to implement naturally. There may be some relevant reasons behind these implications, such as the lack of a set of institutions and the lack of a majority of public policies capable of guaranteeing greater sustainable growth that is in line with the objectives that are naturally sought. The particularities presented by each region guarantee some differences in the application of the different capacities for implementing public policies, both short-term and long-term, associated with biased institutional growth aligned with the objectives that guarantee, for example, the capacity of these regions to effectively translate a relevance that is naturally very efficient from a structural point of view. Thus, the transformation to a federalist country has some implications, such as those largely related to geographical and political structure. Naturally, many countries have these particularities aligned with their political structure, with a large concentration of excessive powers in just a small group of authorities with excessive powers and no capacity for inclusion. Naturally, most of these countries have and present unbiased policies, that is, exclusive public policies. Regions with larger territories, on the other hand, have the particularity of being able to guarantee that there is a greater need for a public policy capable of ensuring better coordination of the actions to be implemented, especially considering that there are higher levels of plausible actions that can guarantee the needs of the respective territories. Thus, considering the size of the territories, there are some regions that require, for example, the implementation of new regions, while in other cases there is a need to merge other territorial units, naturally losing some potential and, above all, a large part of the cultural identity, which is the greatest challenge to be taken into account when territories are transformed into distinct units.

Cultural identity is the most important characteristic to take into account when adopting a federalist model, especially considering the great cultural diversity that most regions tend to present. In larger regions, this characteristic is plausibly accepted as a reason to introduce greater differentiation. However, these differentiations are characterized by the existence of regions that can integrate other subcultures identified in different geographical areas. Thus, the existence of a differentiated ethnolinguistic basis should promote greater evidence of guarantees that can, for example, support regional integration and the growth of different regional cultures. Naturally, these distinctions can in fact affect the ability of regions to provide sustainability in most subcultures. As an example of federalism adopted by the Republic of Ethiopia, Ethiopian federalism is distinguished by the recognition of ethnolinguistic bases capable of translating into marked integration of the regions. For example, in Ethiopia there are 85 languages spoken in different regions of the country. Another plausible example is Nigeria, with more than 300 ethnic groups and 500 languages. On the other hand, South Africa, for example, has more than 12 official languages, which are naturally the most widely spoken languages and have the greatest power of cultural inclusion. However, the cultural base is highly diverse in all regions. In Angola, there are more than 20 official languages, with the most predominant being Umbundo, Kimbundo, Tchokwé, Kicongo, Kuanhama, Nyaneca, Ngagela, and Fiote. These languages in particular dominate Angolan culture, with Fiote and Kicongo being spoken in the north, and Umbundo, Kimbundo, Kuanhama, Nyaneca, and Ngagela predominating in the center, south, and coast of Angola. On the other hand, the east is dominated by the Tchokwé language, which has some significant relevance. Ethnic groups, on the other hand, are in fact a factor of great relevance in the implementation of a federalist model, considering the authorities' great capacity for inclusion from the outset. However, there are still 100 ethnic groups in Angola, and naturally the transformation to a federalist country the preservation of culture and distinct ethnic groups must in fact have geographical continuity, particularly for Angola, which has a significantly larger territory and whose territorial cohesion can be achieved in a context of geographical continuity, particularly considering regions characterized by extreme poverty, such as the southern regions of Angola. Thus, in these regions in particular, I propose the existence of geographical areas characterized by regions A and B, which have the greatest economic potential and are naturally the most developed geographical areas. On the other hand, areas C and D represent the areas with the least capacity for development and are also the poorest economically. Thus, the southern regions easily fall into region D, Some coastal areas may in fact be aligned with region C, where there are, for example, greater characteristics of underdevelopment and inefficiencies in the respective regions, mainly associated with the fact that they cannot naturally achieve growth that is plausible with the desired objectives of regional sustainable development. Thus, the RSDCM (Regional Structural Development and Correction Mechanism) will be particularly relevant in affirming the regions, however, some regions will naturally be subject to the RSDCM, with the aim of naturally correcting all regions that currently suffer from extreme poverty in the unitary context, for example the regions of southern Angola, which nevertheless naturally have these associated characteristics, such as regions C and D, which in fact tend to show marked inefficiency, naturally tending to influence the regions where they should in fact be applied.

Thus, decentralization will naturally take into account certain highly relevant factors that will nevertheless ensure that there is greater correction, particularly in regions where inefficiencies are prevalent in most regions, with greater relevance for regions C and D. Thus, the regions are described in detail in

Table 1, which highlights the particularities of each region, in order to understand how Regional Structural Development Correction Mechanisms can contribute to greater affirmation of the regions in the context of effective decentralization, which should naturally translate into a better understanding of regional development to be implemented in these regions in particular.

Regions C and D, however, do in fact have lower mineral resource potential and, on the other hand, naturally have lower integration capacities, considering the existence of a set of relevant elements that particularly contribute to significantly inhibiting this potential. On the other hand, the existence of lower potential in minerals such as diamonds actually promotes the inefficiency of these regions, which translates into a lower acceleration of sustainable development levels in regions C and D. Agriculture in southern Angola is indeed of great importance in the affirmation of these regions in particular, but due to the lack of a significant value chain network, it does not guarantee sustainable growth in agricultural production, which is largely unsustainable. Region D, however, has lower levels of structural development in all areas, both in terms of urbanization and in aspects related to the structure of the region itself. Thus, it is naturally a region where, from the outset, the RSDCM (Regional Structural Development Correction Mechanisms) should focus on ensuring structural alignment and cohesion of the different structures associated with the promotion of efficient sustainable development, with the aim of ensuring greater regional resilience, which could, on the one hand, provide greater capacity for growth in line with the particular levels of great capacity that regions should naturally translate and present in response to the different particularities that could, however, ensure that there is in fact better alignment between policies and the respective institutions.

So, how should RSDCM actually work? To a large extent, their operation should be aligned with the particularities of regional restructuring. However, in order to ensure greater balance between regions and, on the other hand, promote higher levels of competitiveness between different regions, these mechanisms could play a more significant role in affirming these regions. For example, by applying the Structural and Regional Development Correction Mechanisms (RSDCM), poor regions should be elevated to a category that allows, for example, the inclusion of these regions and in a more competitive way with the other regions, such as tax incentives for a large part of the industry with tax headquarters in the state and targeted subsidies as a way to ensure better harmony between states and, on the other hand, ensure fiscal harmony in each municipality at the state level.

Table 2 shows how RSDCM work and, above all, how they will affect key public policies. Thus, ensuring greater representation of the regions is the main reason and, on the other hand, a plausible reason for boosting these regions in particular.

However,

Table 2 clearly shows how correction mechanisms can correct the various particularities that mainly relate to how these mechanisms can actually transform most actions into inclusive public policies capable of contributing to the necessary transformations. The plausible transformation through fiscal decentralization is likely to promote the integration of regions C & D and, moreover, channel greater efficiency with regard to the implementation of public policies capable of ensuring greater resilience and sustainability in the regions, which is particularly the main factor for stability and guarantees of integrated sustainable growth.

The subnational units to be taken into account will also be characterized by their geographical size. Angola, in particular, has a vast territory, and in the current context, most of Angola's provinces do not meet the criteria for decentralization. there are, for example, some geographical regions without any sustainable development. This particularity has to do, for example, with the unitary state, where the regions that concentrate most of the economic activity tend to present greater territorial discrimination promoted by the greater economic and political administrative concentration in regions whose conditions are in fact different from the others.

The current political and administrative division does not actually promote prosperity in the regions, much less guarantee that these regions will indeed experience marked prosperity. However, allowing for prosperity is in fact related to guarantees, particularly those provided by the authorities, which can still drive sustainable regional growth.

The lack of strong territorial cohesion stems from the lack of effective decentralization, with levels of centralization tending to promote policies of geographical discontinuity and political and administrative discontinuity. On the other hand, there is discontinuity in institutions, which are largely discontinuous due to the initial lack of convergence criteria with the capacity to drive institutions towards greater prosperity.

The geographical continuity of the current political and administrative division is nevertheless plausible for better affirmation of the territories and the affirmation of the regions in particular, naturally considering the regions of low capacity but nevertheless promoted by them. The transformation to a federalist system will, on the one hand, take these aspects into account, so it is naturally plausible that geographical continuity is in fact a relevant factor in proposing, on the one hand, the continuity of the regions defined by the territories that make up the current unitary state of Angola, considering, on the other hand, the fact that there is, for example, greater cultural continuity. On the other hand, the consideration of increasing new subnational units may suggest significant decentralization, in terms of the dynamics proposed by a set of territories that will be covered by the federation. Most federalist countries follow a model of territorial decentralization based on a model in which there are subnational units plus a federal state with an autonomous district, the autonomous district being relevant and important for the better affirmation of the other units. The autonomous federal districts follow a federalist model characteristic of the United States of America and Brazil, However, some other countries follow the same model, such as Nigeria, for example. The autonomy and greater decentralization of other regions can, in fact, contribute plausibly to a better perception of these regions as decentralized units. On the other hand, it is a model with greater freedom for public policies to be implemented, especially when considering the inclusion of these public policies. The big difference persists particularly in the fact that in countries with significantly unitary systems and greater political and administrative centralization power, the capitals are linked to other cities and, on the other hand, have greater power to centralize economic and political activities, especially with a focus on centralized industrialization. On the other hand, greatly influenced by the inefficiencies of political and economic institutions, particularly political institutions, which have not in fact been able to demonstrate marked resilience. Thus, in federalist countries that adopt a model with an autonomous federal state, the decentralization of economic activities is in fact greater and has some plausible relevance in economic and political affirmation. However, in countries with this model, there is no discrimination against other territories. In Angola, for example, this characteristic is particularly evident, with Luanda presenting an economic concentration due to a set of industrialization significantly based on geographical advantages and highly relevant infrastructure. On the other hand, however, political and administrative centralization follows the same line, with economic and social structures that are plausible in terms of greater territorial coherence and cohesion. Services in Angola follow the same line; for example, a large part of the services in Angola follow a line of centralization promoted largely by its institutions. However, on the other hand, there is discrimination against services in other regions with characteristics that could in fact allow for greater interaction between institutions and regions.

Thus, on the one hand, Luanda currently concentrates fiscal policy, which is in fact another plausible reason that nevertheless promotes the inefficiency of other regions in terms of taxation capacity. On the other hand, it has to do particularly with the existence of marked fiscal concentration, The predefined fiscal zones have not been able to demonstrate the fiscal sustainability necessary to promote, for example, greater efficiency in tax zones and the capacity itself related to more plausible and sustainable growth levels of great relevance. Fiscal centralization, promoted largely by tax authorities, has in fact focused on not including a more efficient and resilient fiscal policy in determining the various actions needed to boost fiscal dynamics in particular. However, on the other hand, in the presence of fiscal centralization, institutions with the power to, for example, execute fiscal policy tend to show higher levels of institutional corruption. thus, to a large extent, institutional corruption in this way tends to weaken fiscal policy on the one hand and weaken the actions necessary to ensure greater prosperity on the part of the authorities with the aim of being able to implement a set of inclusive public policies capable of changing and transforming most institutions in the context of inclusion.

In the presence of a set of centralized institutions, fiscal policy does not follow a line capable of ensuring that there is in fact greater rigor in the application of the respective public policies. However, considering above all the great particularity that exists with regard to the reformulation of the institutions themselves, with the aim of continuing to contribute to the improvement of the institutions and their respective policies, as an example for Luanda, it represents the core of fiscal policy in line, for example, with the inability of institutions to actually transform their public policies, with the particular feature that they can actually have an impact on other regions. Regions with some associated inefficiency should, on the other hand, be likely to present some factors of great relevance with the capacity for transformation.

A large part of the regions in Angola, for example, do not have fiscal decentralization, which promotes inefficiencies in their respective regions, especially given that these regions are not in fact capable of achieving greater balance in public finances. Thus, in particular, these regions are in fact unable to associate a set of institutions with a set of public policies in particular that are that are significantly efficient and capable of bringing about the best possible transformation of the regions. Thus, for example, the provinces of Angola are largely unable to naturally bring about some plausible effects that should in fact introduce some efficiencies with regard to their ability to convert the regions into areas with greater attractiveness among the regions. On the other hand, the lack of attractive regions does not guarantee that these regions will be able to introduce plausible changes to their institutions. At the provincial level, in the current context, it is not possible for regions to define a provincial budget with transfers to intra-regional areas, such as municipalities. However, provinces are prevented from adopting greater autonomy for their institutions, and a large part of tax revenues are in fact channeled largely to the central region, such as Luanda, which is still the largest fiscal center. In the context of fiscal decentralization, public finances converge towards regions with less potential and fewer fiscal responsibilities. Thus, fiscal responsibilities in most regions should nevertheless converge towards the promotion of a distinct basis for public finances and taxation in particular.

The current unitary republic of Angola, for example, Luanda significantly concentrates judicial power, focusing on the centralization of judicial institutions and the judicial system itself. On the other hand, in the presence of judicial decentralization, states should initially have greater freedom of action and greater freedom in these regions, for example, being able to become - autonomous in judicial decisions and in their ability to actually translate some substantial improvements related to the full functioning of these judicial institutions as institutions capable of translating improvements with regard to the supervision of some actions of great institutional relevance, in particular. However, the reformulation of these institutions should follow a line of interaction with other regions that have a particularly effective and differentiated institutional dynamic, as can be seen in institutions that are plausible in presenting the greatest possible impartiality. Thus, fiscal decentralization, geographical decentralization, political-administrative decentralization, and judicial decentralization can in fact suggest the promotion of substantial improvements in different regions, with the capacity of these regions to translate into marked regional efficiency.

4. Proposal for a Federal Model for Angola

Angola is characterized by being a country with both absolute advantages and efficient comparative advantages to promote, on the one hand, different areas that are relevant to growth and sustainable development. Thus, the large and extensive territory is in fact a fundamental reason for the perception of the country's natural capabilities, from the point of view of its economic and political-administrative structure. However, Angola currently has a unitary state, which is largely inefficient from a fiscal, judicial, political, administrative, democratic, and political point of view. Most of these institutions are inefficient and ineffective in their ability to implement key policies. They do not function due to the lack of inclusive policies and, on the other hand, due to the great capacity aligned with the objectives that the regions in particular should convey. The excessive concentration of institutions and the economy in a single region plausibly represents the fundamental reason for the perception of continuous failures, which are nevertheless associated with the lack of a significant set of policies capable of asserting themselves in a context of effective and efficient decentralization.

The excessive concentration of the economy in a single region currently represents a plausible reason for Angola's inability to significantly boost its economy. The lack of fiscal decentralization promotes inefficiency in fiscal policy and particularly in economic institutions, which aim to bring about economic transformation through a decentralized tax system. Economic transformation is non-existent, This is particularly due to the excessive concentration of the economy in a single city, as is the case in Luanda. Democracy is non-existent due to the excessive concentration of political power in a single party. However, democratic plurality is not evident because, in fact, political institutions do not allow for this plurality to exist. On the other hand, these same institutions do not allow for greater political inclusion, which naturally justifies the same party's 50-year hold on power. The centralized republic with excessive powers in just one city and a single executive effectively proposes the continuation of governance failures and the implementation of public policies with relevance to the capacities that these policies tend to produce insignificant effects of associated sustainable growth. Naturally, some factors, such as vicious circles, tend to justify Angola's continued adherence to the current model of a unitary republic characterized by ongoing extreme poverty. so significantly, the existence of a unitary state actually means that there is a particularly greater failure associated with the levels of governance incapacities of the authorities. On the other hand, these incapacities are nevertheless accentuated, especially judging by the lack of continuity of institutions that should nevertheless be in line with the short-term objectives that are decisive for a better affirmation of the respective institutions in particular.

On the other hand, there are some aspects characterized by structural political inefficiency, particularly considering the fact that these inconsistencies may in fact affect the various public policies adopted as mechanisms that could nevertheless guarantee economic and political transformations, largely political transformations. These occur through a set of actions that do not particularly converge towards a perception, for example, of how economic and social institutions should nevertheless suggest significant substantial improvements.

Much of the evidence shows that there is a significant correlation between political centralization and an increase in poverty, particularly multidimensional poverty, as is the case in most regions. Multidimensional poverty in Angola is characterized by the existence of political and economic institutions with greater capacity for political centralization. Thus, the evidence clearly shows that the effects of political centralization have not been sufficient to ensure, for example, a set of public policies that should be largely related to strengthening these institutions. Thus, in particular, Angola is following a path characterized by the failure of public policies and institutional continuity, due in particular to the lack of effective and significant decentralization, especially in relation to aspects that naturally translate into institutionalized failure.

Economic centralization in Angola impoverishes regions with greater potential to ensure sustainable growth and development. Thus, for example, there is greater failure associated with the distribution of wealth in regions where there is no starting point for the particularities that should above all drive sustainable growth of great regional relevance, strongly supported by the lack of inclusive autonomy of regions and subnational governments in the interior. for example, current municipal and provincial governments do not yet have effective autonomy to implement a set of inclusive public policies that are, on the other hand, capable of bringing about some improvement in regional public policies.

Although the current constitution of the republic effectively establishes a presidential system, there are too many functions assigned to the president of the republic and the executive branch. For example, in the current version of the unitary republic, a provincial government does not have plausible powers to implement local public policies, such as those that may affect the implementation of large-scale public projects with relevant characteristics. For example, in order to build a public school in a rural region, approval from the Ministry of Education is required. However, the central government has 99.9% of the powers to implement public policies that should affect rural regions. Thus, the central government has all the powers to transform the regions, but the lack of effective autonomy among the regions ensures that the central government is the main playmaker in the actions to be taken. Thus, on the one hand, the regions become poor and unable to demonstrate any possible resilience or any plausible degree of growth that might suggest some transformation through the criterion of inclusion.

The authorities' failure to distribute wealth effectively suggests continuously higher levels of corruption and state bankruptcy, associated with the ongoing failure of public policies. There is no stable consolidation of institutions that are, for example, capable of aligning themselves with long-term objectives. Institutions, because they do not present any plausible possibility of inclusion, they tend to move towards continuous increases in levels of marked corruption.

Legislative centralization prevents most political parties from contributing to the strengthening of democracy and greater democratic plurality. Under the current system, a significant minority has effective control over democratic and political institutions, thus democratic participation is relatively low, judging by the political actors who can actually participate in the political arena. For example, currently only five parties have seats in parliament, of which two parties hold 90% of the parliamentary seats, thus clearly demonstrating how legislative power is shared only among a small group of political parties. Thus, in the current scenario, political parties are unable to translate any political inclusion, much less suggest any effective and naturally efficient democratic plurality. Thus, political and democratic discontinuity is accentuated by the permanence of only a small group with the capacity to govern and elect their own to be naturally elected.

Fiscal decentralization does indeed give states greater autonomy, as it suggests that regions have greater freedom to transform themselves. However, in the Angolan scenario, fiscal decentralization could be implemented through a set of Structural and Regional Development Correction Mechanisms, with the aim of introducing greater actions in decentralized regions that could translate into greater regional structural balance.

4.1. Fundamental Pillars of the Federalist Model Proposal in Angola

The main premise of the federalist model consists precisely of fiscal, political-administrative, judicial, territorial, and political decentralization. These capacities for decentralization give most regions greater autonomy in public finances, greater democratic plurality, and greater political inclusion of their stakeholders.

Administrative Policy Decentralization

Angola currently has 21 provinces and 326 municipalities, 378 communes, representing different levels of public administration. However, most of these administrative units are 99.9% dependent on the central government, with the country's capital coordinating most public policies. On the other hand, fiscal policy is focused on the capital, Luanda. Thus, both the provinces and the municipalities and communes are dependent, and their leaders depend on appointments. For example, the President of the Republic appoints governors and ministers, governors and ministers appoint municipal administrators and delegates who represent ministerial entities in the province, respectively, and governors tend to appoint commune administrators, which is the lowest level of political/administrative administration. With this model, provinces, municipalities, and communes do not have the freedom to create their own public policies, as they are in fact more inefficient and dependent on centralized political and administrative power. Most institutions are centralizing in nature, with greater political and administrative decision-making power in the capital. Therefore, on the other hand, this model creates functional wear and tear on the authorities, that is, considering an accumulation of excessive powers that do not guarantee any participation by the majority in the political arena.

Therefore, I propose autonomy for the other subnational units, with only minimal dependence on the federal constitution in a few details that are indeed relevant from the federal and union perspective. The current 21 provinces can in fact guarantee geographical continuity for 21 federal states with one new federal capital, namely the state of New Angola, with the federal capital being the autonomous federal district of "City 3 F.D.", which represents the capital of a new federal state. The 21 proposed states plus the federal capital will have 99.9% autonomy over their political institutions and legislative institutions in particular. The regional autonomy of the states will follow a model of non-dependence on the central government, meaning that each state must adopt its own state constitution, which may be the main instrument for political and administrative functioning. On the other hand, the 22 states must have public finances that converge with the fiscal policy significantly developed by state authorities. A large part of the services that currently tend to be more centralized by Luanda, the 22 states will naturally be able to promote these services with greater decentralization and greater balance with regard to the capacity of state institutions to effectively suggest greater autonomy for these institutions in particular.

The federal states will naturally be the subnational unit following the Union, with their own powers, but each state will be governed by a governor elected by the state's population. On the one hand, this allows the states to be in line with the other territories, particularly in states with larger populations, which will in fact tend to promote greater governmental inclusion. For greater democratic plurality, a diverse set of political parties can naturally compete, meaning that political parties must nominate candidates to head the list for each political party running.

Thus, the intermediate level of the Federation will be precisely the federal municipalities, where I propose 400 federal municipalities for the 22 states. Naturally, the municipalities should have their respective autonomy, particularly considering their own executive that could initially govern the municipality. For example, each municipality should have its own government elected in intra-regional elections, where initially several parties could nominate the leaders of their respective political parties. However, this decentralization suggests greater democratic plurality in the intermediate regions. On the other hand, a large part of the local regional parties will be able to form and present their political parties, which translates into greater efficiency of political institutions and greater decision-making capacity on the part of political authorities. Thus, the population will tend to have greater freedom of choice, in line with the objectives that each regional unit should present.

Communes are currently not very efficient in communities, so I propose Federal Parishes to replace communes, where they will have greater autonomy and closer ties to localities, especially with the majority of the population. Thus, Federal Parishes should, on the one hand, be in line with the objectives that each municipality intends for its respective regions, but with greater rigor in the execution of services. On the other hand, they should be in line with political and administrative decentralization. Thus, each Federal Parish will have an executive elected by the parish population, who should ensure maximum efficiency in local decentralization. In intra-regional elections, political parties and some prominent figures in each parish should, for example, run for election and be naturally elected by the local parish population. Therefore, I propose for the future Angolan federalist model, 1,200 Federal Parishes. Naturally, their distribution across each municipality will depend on certain factors, such as the population of each municipality. Significantly, municipalities with larger populations should initially have a greater number of parishes. Federal parishes can indeed be of great importance and relevance to most regions, especially considering the fact that these parishes serve as the main basis for more effective and, above all, decentralized community governance in most of their sectors of activity. Parishes should serve as a bridge between municipalities and federal community councils, in order to ensure more robust local governance and more efficient community governance that is sufficiently capable of suggesting improvements.

Federal Community Councils represent, however, the lowest level of public administration, and are in fact the level at which there is the greatest balance between local populations. The aim of federal community councils is to achieve greater balance and greater participation in local governance. On the other hand, the aim is to ensure that each of the federal community councils is capable of translating greater resilience and efficiency in public administrations. so in most of these councils, the regions' policies will in fact tend to converge with local objectives. Current communities do in fact have problems that the current administration does not guarantee will be resolved, on the one hand due to the incapacities of local administrations and on the other hand due in particular to the levels of centralization, which nevertheless channels the distance between the rulers and the ruled. I therefore propose greater proximity between the rulers and the ruled, whereby the efficiency of public services can in fact be raised to a higher level and a distinct category in a plausible manner. For Angola in particular, I naturally propose 7,200 Federal Community Councils. Naturally, regions that have a greater number of municipalities will tend to have a larger share of community councils. On the other hand, neighborhoods should still form community councils. Thus, I propose 60,000 federal neighborhoods, which are naturally relevant to the organization of community councils. Federal neighborhoods should particularly follow a line of community organization, thus taking into account some particularities such as those associated with proximity and access. On the other hand, the health system should nevertheless converge with the intended regional objectives and, above all, with significantly close communities. However, the relationship between community councils and neighborhoods may allow for greater proximity to some basic services of greater community relevance, such as community social services, community public health, and community public schools, which are in fact the sole responsibility of federal municipalities and federal parishes.

Thus, in a context of political and administrative decentralization, there is plausibly greater freedom of choice on the part of the authorities, on the one hand, and better distribution and management of public resources, on the other. In most of these regions, the resources distributed will tend to be used more efficiently. Furthermore, there is a closer relationship between subnational units and the needs for local public policy-making. Each decentralized unit may be able to channel the correct and effective use of different public resources more effectively and, in particular, the main financial resources for most institutions. Thus, on the other hand, with decentralized units, the levels of corruption arising from different public projects will nevertheless be reduced in most of these decentralized units, for example, overbilling in most public projects, where the departure translates into greater inefficiency in public finances and considerable increases in public budget levels. most of these projects have high costs, especially considering that most of them double the costs per public project. The levels of overbilling in public projects are in fact strongly associated with causal impoverishment on the part of the authorities and different governments, especially considering the significantly excessive rates of increase in public expenditure by governments, which is one of the main characteristics of developing governments with high levels of poverty. Thus, political and administrative decentralization can be clearly seen in

Table 3.

The autonomy between states is nevertheless evident through the relationship of non-interdependence between states and the federation, between municipalities and municipal parishes, and between community councils and municipal parishes. Thus, it is natural to ensure that there is greater transfer of responsibilities and better interdependence between units, with a focus on effective decentralization.

Fiscal Decentralization

On the other hand, I propose greater fiscal decentralization through decentralized units, particularly from the federal union to the other units. Thus, in the current reality in Angola, fiscal policy is inefficient due to the high degree of centralization of institutions. For example, a large part of tax revenues are initially collected in all provinces to form a single budget, therefore, the results of the current fiscal policy centralization suggest that there are more frequent failures in the distribution of wealth to other regions. Thus, regions with greater population and economic concentration tend to retain the largest percentage of tax revenues. On the other hand, this model suggests fiscal discrimination against other regions that actually have greater contributory capacity in their respective regions.

Therefore, I propose fiscal decentralization that is particularly in line with the objectives of sustainable public finances, adapted to local realities. In particular, decentralization will in fact be a driving force capable of correcting the inefficiencies of public finances and promoting significant improvements in the different levels of sustainable budgetary policy, converging towards greater structural balance between the significantly administered regions. Thus, in order to accelerate fiscal decentralization more significantly, states should particularly have their own tax institutions, with each of these institutions being responsible for tax revenues in each of the states and, on the other hand, with greater responsibility for defining the taxes to be levied in each state. All operations related to fiscal policy will be the particular responsibility of the states, where each state must and can define the optimal limits to be implemented for tax collection. On the other hand, correction mechanisms may affect states that have a particular structural deficit and greater poverty. For example, each state should naturally collect Value Added Taxes and other indirect taxes that are necessary for taxation, and some direct taxes should naturally be collected by the states. From the outset, each state should contribute a fixed percentage to a Federal Territorial Cohesion Fund. At the federal level, some taxes may in fact be levied, such as customs duties and corporate income taxes, for example. On the other hand, in order to achieve greater efficiency and decentralization, I propose that municipalities be autonomous in terms of tax revenues, with the aim of achieving greater balance in public finances, in particular, and in general, in fiscal policy with greater relevance. Thus, federal parishes will naturally be able to tax small-scale local activities, such as markets, waste management, local licenses, transportation, and other local taxes whose institutional relevance may be exclusively related to the parishes. A large part of the taxes from sectors whose relevance extends to the federal level should be taxed by the federation. On the other hand, through the Territorial Cohesion Fund, states, for example, should channel a percentage to this fund, with the aim of translating efficiency into correction mechanisms that should be driven by the Regional Structural Correction and Development Mechanisms, focusing on regions where the poverty rate is significantly high.