1. Background

Oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) represents a profound and escalating global health challenge [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]. As the most prevalent malignancy of the head and neck, it accounts for more than 90% of all oral cancers [

1,

6,

8] and is responsible for an estimated 389,000 new cases and 188,000 deaths annually worldwide [

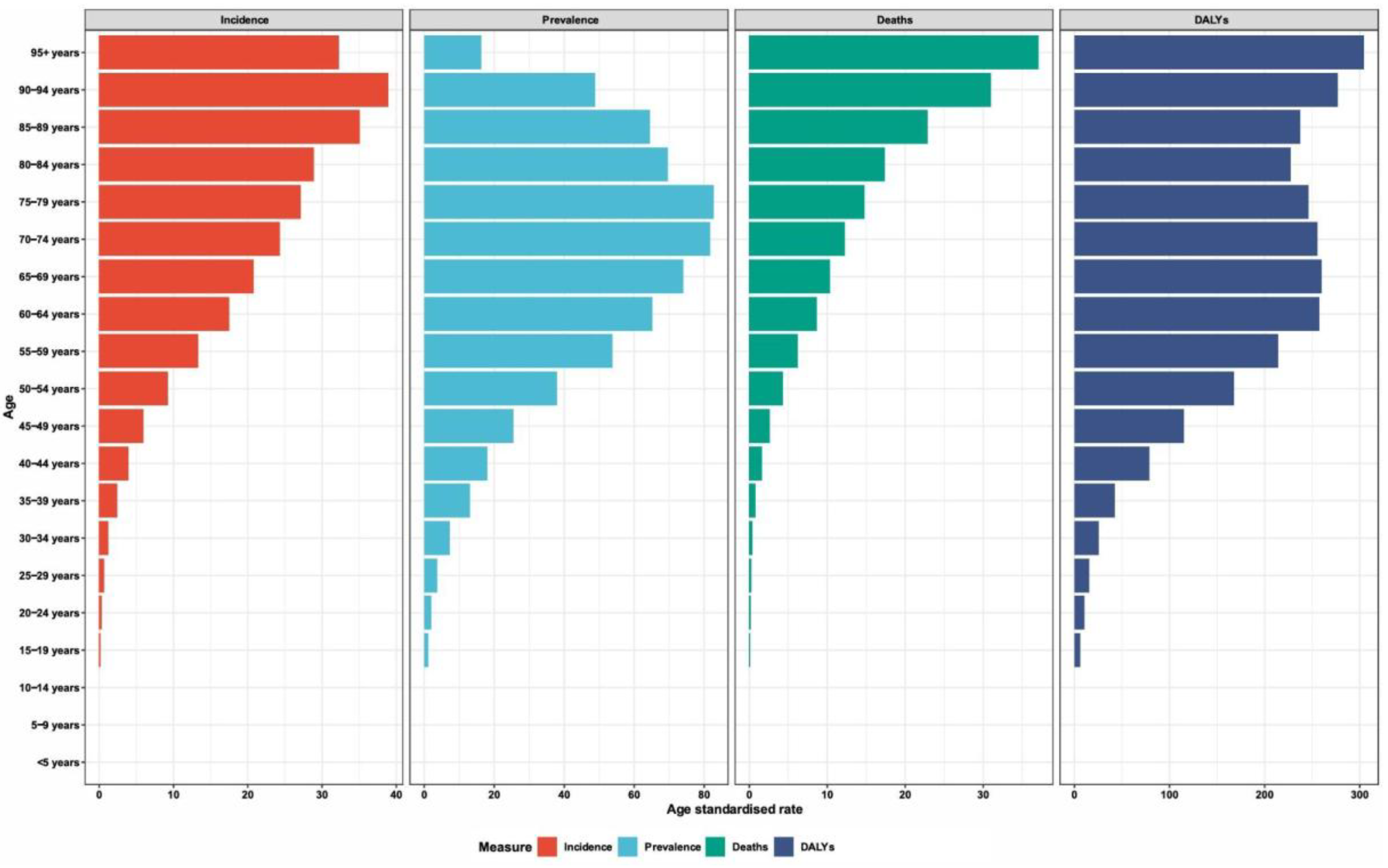

6]. This burden is not evenly distributed; from 1990--2021, the absolute number of deaths and disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) from lip and oral cavity cancer increased by 92.92% and 113.94%, respectively (

Figure 1) [

5]. This growing crisis is marked by stark sociodemographic disparities, with mortality and DALY rates consistently highest in low- and middle-sociodemographic index (SDI) regions, even when incidence rates are higher in more developed countries [

16]. These statistics paint a sobering picture of a disease where geography and economic status are potent determinants of survival [

4,

16].

The lethality of OSCC is tragically linked to a marked drop in survival when the disease is not caught in infancy [

3,

8]. The difference between early- and late-stage diagnosis is a matter of life and death: the five-year survival rate can reach 70–90% for localized, early-stage tumors but decreases to less than 50% once the cancer has progressed [

6,

8]. In some populations, the five-year survival for advanced disease is a staggering 20%, compared with 80% for stage I cancers [

10]. The core of the problem lies in delayed detection. The vast majority of patients, over 85% in some studies, are diagnosed at an advanced stage (III or IV) [

10]. This delay is particularly pronounced in low- and middle-income countries, where 60–70% of patients present with late-stage disease, compared with 30–40% in high-resource settings [

6]. This diagnostic delay not only decreases survival rates but also has devastating consequences for quality of life, with extensive surgeries leading to permanent functional impairments in speech and swallowing [

6].

This diagnostic latency stems from a critical screening void, especially within community and low-resource dental settings, which should serve as the first line of defense [

2,

4]. Dental professionals conduct more than 75% of all oral cancer screenings, making routine dental visits an unparalleled opportunity for early detection [

4]. However, this opportunity is frequently missed. Access to dental care is a significant barrier, particularly for low-income adults, who bear the greatest burden of the disease [

4]. A landmark study demonstrated that the elimination of Medicaid dental benefits in California was associated with a 6.5%-point decline in early-stage diagnoses of oral cavity cancers, powerfully illustrating the link between dental access and survival [

4]. Even when patients do see a dentist, challenges persist. Many practitioners in developing countries feel that they lack the time, training, and confidence to conduct screenings effectively, with fewer than half feeling adequately knowledgeable [

2,

11]. This gap creates a perfect storm where the disease goes unnoticed until it is far too late, resulting in not only loss of life but also a substantial economic burden. The cost of treating advanced-stage OSCC can be 22% to 373% higher than that of treating early-stage disease, representing a catastrophic economic burden on healthcare systems and individuals alike [

14].

1.1. Saliva as a Precision Liquid Biopsy

In the quest to bridge this deadly diagnostic gap, the concept of "liquid biopsy", the analysis of tumor-derived materials in bodily fluids, has emerged as a transformative alternative to invasive tissue biopsies [

7,

8]. While blood has been the traditional focus, saliva offers a uniquely powerful, noninvasive window into the molecular landscape of OSCC [

7,

8,

15]. The anatomical proximity of the oral cavity to the salivary glands allows for direct shedding of tumor components, including circulating tumor nucleic acids (ctNAs), extracellular vesicles (EVs), and exfoliated tumor cells [

7,

8]. This localized shedding may lead to a higher concentration and more sensitive detection of biomarkers compared with those in blood [

9,

15]. The collection process itself is a patient-centered approach: it is painless, inexpensive, can be performed without specialized personnel, and allows for the painless repeated sampling necessary for real-time monitoring of disease progression and treatment response [

7,

8]. The overall workflow for salivary liquid biopsy involves the collection of saliva, followed by the detection and analysis of various tumor-derived biomarkers, including ctDNA, ctRNA, and extracellular vesicles, which then inform a range of clinical applications from early diagnosis to therapeutic monitoring (

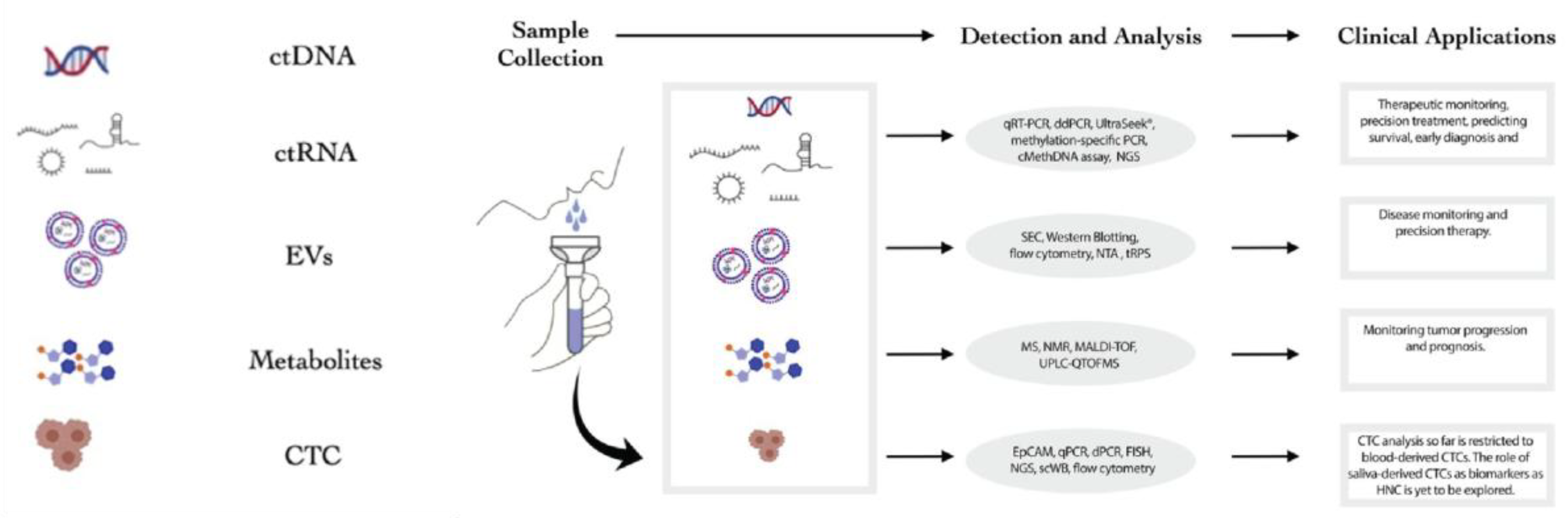

Figure 2) [

7].

The true power of salivary liquid biopsy lies in its ability to provide a multilayered, synergistic view of the tumor by analyzing both cell-free DNA (cfDNA) and cell-free RNA (cfRNA). While cfDNA reveals the stable genetic and epigenetic blueprint of the tumor, including cancer-specific mutations and DNA methylation patterns, cfRNA offers a dynamic, real-time snapshot of the tumor's functional state through its gene expression profile [

7,

8,

9,

15]. One study demonstrated that for cfRNA analysis, saliva is a more effective medium for OSCC detection than blood plasma is [

15]. This synergy is crucial; combining the stable, cancer-specific "what" from cfDNA with the dynamic "how" from cfRNAs provides a far more robust and comprehensive signature of malignancy than either molecule alone could alone.

The evolution of salivary biomarkers reflects a continuous journey toward greater precision and clinical utility. Initial research focused on proteins, enzymes, and metabolites, which, while valuable, often lacked the specificity needed for definitive diagnosis owing to their presence in various physiological and noncancerous pathological states [

1,

3,

7]. The field then advanced into the "-omics" era, first exploring the transcriptomes of dysregulated microRNAs (miRNAs) and messenger RNAs (mRNAs) [

7,

8]. More recently, the focus has shifted to the epigenome, particularly the analysis of DNA methylation patterns [

3,

9]. These epigenetic marks are highly stable and often tumor specific, offering a robust signal that can be detected even in the earliest stages of carcinogenesis [

9]. It is at this cutting edge that a technology such as SalivaSense 2.0 is positioned. It represents the logical next step in this evolution, moving beyond single-analyte discovery to a multiplexed approach that integrates the most stable and specific signals from both the cfDNA epigenome and the cfRNA transcriptome. This integrated strategy aims to create a highly sensitive and specific signature capable of detecting OSCC at its inception, transforming early diagnosis from a challenge into a clinical reality.

The grim reality of OSCC is that it remains a devastatingly lethal disease, not because it is untreatable but because it is often found too late [

6,

8,

10]. A vast and inequitable screening void persists precisely in low-resource and community settings, where early detection could have the greatest impact [

4,

11,

12,

16]. While salivary diagnostics have shown immense promise, the translation from laboratory discovery to clinical application has been fraught with challenges related to sensitivity, specificity, and standardization [

3,

7,

8]. The next frontier in this field must therefore focus on creating a robust, validated, and accessible diagnostic framework that can overcome these historical barriers.

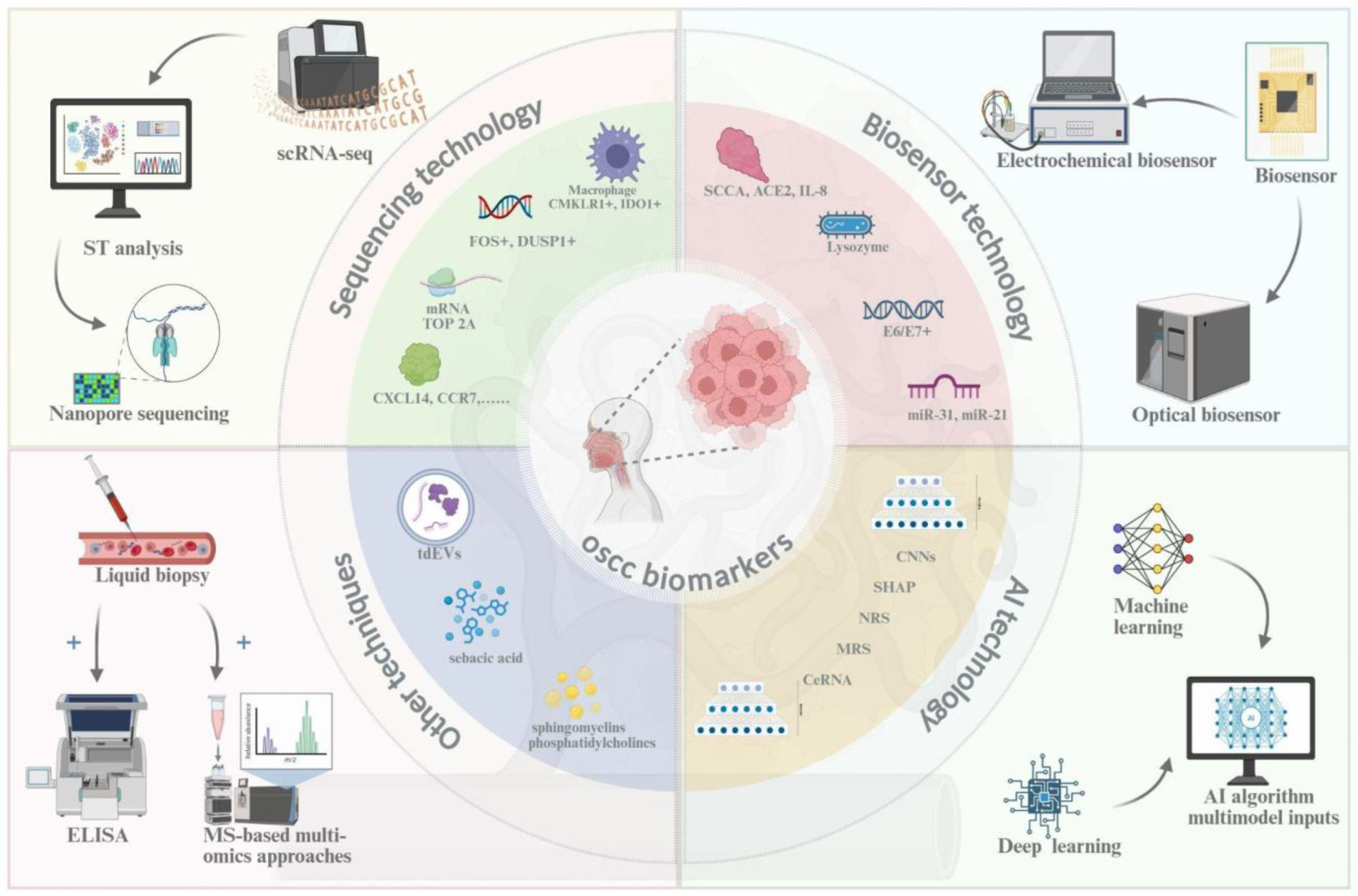

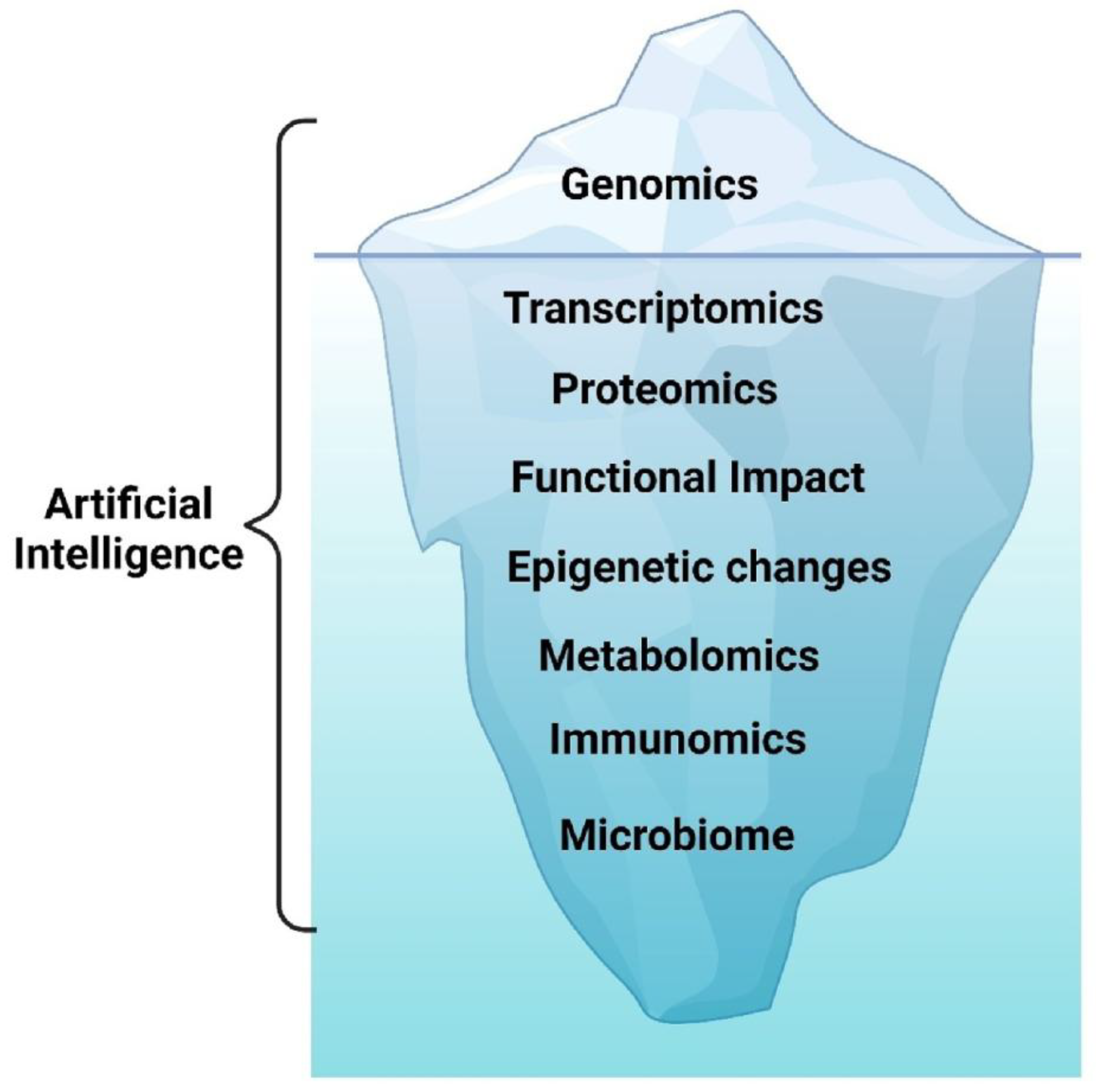

This review synthesizes the current evidence to build the case for SalivaSense 2.0, a hypothetical next-generation diagnostic framework predicated on multiplexed salivary cfDNA and cfRNA epigenome signatures. We aim to delineate a comprehensive roadmap for its development, validation, and implementation for the pico-stage detection of OSCC, catching the disease at its molecular dawn. To achieve this goal, this paper will be guided by three central questions. First, what is the multifaceted global burden of OSCC, and why does the chasm between early- and late-stage survival mandate a paradigm shift toward pico-stage detection? Second, how has saliva evolved into a precision liquid biopsy medium, and what is the synergistic potential of combining cfDNA and cfRNA epigenomic signatures to overcome the limitations of previous single-analyte biomarkers? Finally, what are the critical components of a translational pipeline, from robust validation frameworks to equitable implementation strategies, required to move a technology such as SalivaSense 2.0 from the research bench to the front lines of community health and global oncology? Answering these questions requires an integrative understanding of OSCC biomarkers and the convergent technologies used for their detection and analysis. The subsequent sections of this review delve into key technological domains, including advanced sequencing, biosensors, and artificial intelligence, that form the foundation of next-generation salivary diagnostics (

Figure 3) [

7].

2. Molecular and Biophysical Findings

The advent of salivary liquid biopsy has led to a deep understanding of the molecular processes that governs the life of cell-free nucleic acids (cfNAs) [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30]. These fleeting molecular fragments, which are ejected from cells throughout the body, embark on a remarkable journey, carrying with them a dense repository of biological information that mirrors the genomic and epigenomic state of their parent tissues [

19,

22]. To harness their diagnostic power, particularly for detecting nascent oral squamous cell carcinomas (OSCCs), we must first unravel the fundamental principles of their creation, their transport into the oral cavity, and the stabilizing associations that shields them from degradation. This exploration reveals a world where the mechanisms of cell death, the architecture of our own chromatin, and the enzymatic landscape of saliva converge to shape the very nature of these powerful biomarkers.

2.1. Biogenesis, Release Kinetics and Salivary Trafficking

The story of a cfDNA or cfRNA molecule begins at its moment of release, a process governed by the life and death of a cell [

22]. In the context of oral carcinogenesis, the dysplastic epithelium becomes a primary source, shedding these nucleic acid fragments into the surrounding biofluid through a combination of passive leakage and active, vesicular export [

18,

20]. The dominant release pathways are processes of cell death, including apoptosis and necrosis [

19,

30]. Apoptosis, a form of programmed cell death, involves the orderly cleavage of DNA by endonucleases into fragments that reflect the fundamental packaging of our genome [

19,

22]. This process generates the characteristic mononucleosomal cfDNA peak at approximately 167 base pairs (bp), a length corresponding to the DNA wrapped around a core of histone proteins plus a small linker segment [

20,

22,

25]. In contrast, necrosis, a more chaotic form of cell death often observed in tumors, results in a more haphazard release of DNA, yielding longer and more variably sized fragments that can extend up to 10 kilobases (kb) or more [

20,

22].

In addition to being passively released, cells also actively secrete cfNAs, which often package them within extracellular vesicles (EVs), such as exosomes and microvesicles [

18,

28]. These lipid-bound nanocarriers are produced during normal cell metabolism and are crucial for intercellular communication, ferrying their cargo of DNA, RNA, and proteins between cells [

18,

28]. In cancer, this process is coopted, with tumor cells releasing EVs that carry tumor-specific genetic and epigenetic alterations [

20,

30]. This dual-origin narrative, which involves passive shedding from dying cells and active export from living cells, creates a complex and information-rich pool of cfNAs.

Once released, these nucleic acids must traverse the oral cavity to become salivary biomarkers. Saliva is a unique biofluid in that it captures cfNAs from two distinct sources: local and systemic [

17,

20]. Locally, cfDNA and cfRNA are shed directly from the tissues of the oral cavity, including the tumor itself and surrounding epithelial cells [

20,

30]. Systemically, cfDNA from distant sites, such as hematopoietic cells, which are the primary source in healthy individuals, travels through the bloodstream and enters the saliva via passive diffusion and is transported through capillary-rich salivary glands [

17,

23,

30]. This dual trafficking mechanism makes saliva a powerful diagnostic medium, offering a direct sample of the tumor microenvironment while also providing a window into systemic disease processes [

20].

The journey from the cell to the saliva imprints a distinct signature onto the cfDNA fragments themselves. The resulting population of salivary cfDNA (scfDNA) exhibits a characteristic fragmentation profile that differs from that found in blood plasma [

17]. Analysis of scfDNA revealed a peculiar, "jagged" size distribution with multiple peaks between 35 and 300 bp, in stark contrast to the more defined mononucleosomal peak observed in plasma [

17]. This jagged pattern is a direct reflection of how DNA is packaged within the cell nucleus. The surviving fragments are essentially "nucleosome footprints," which are remnants of DNA that are protected from enzymatic degradation by being tightly wound around histone proteins or bound by transcription factors [

19,

25]. The locations and sizes of these fragments thus provide a map of the chromatin landscape of the cell of origin, revealing which genes were active or silent at the time of release [

19,

25].

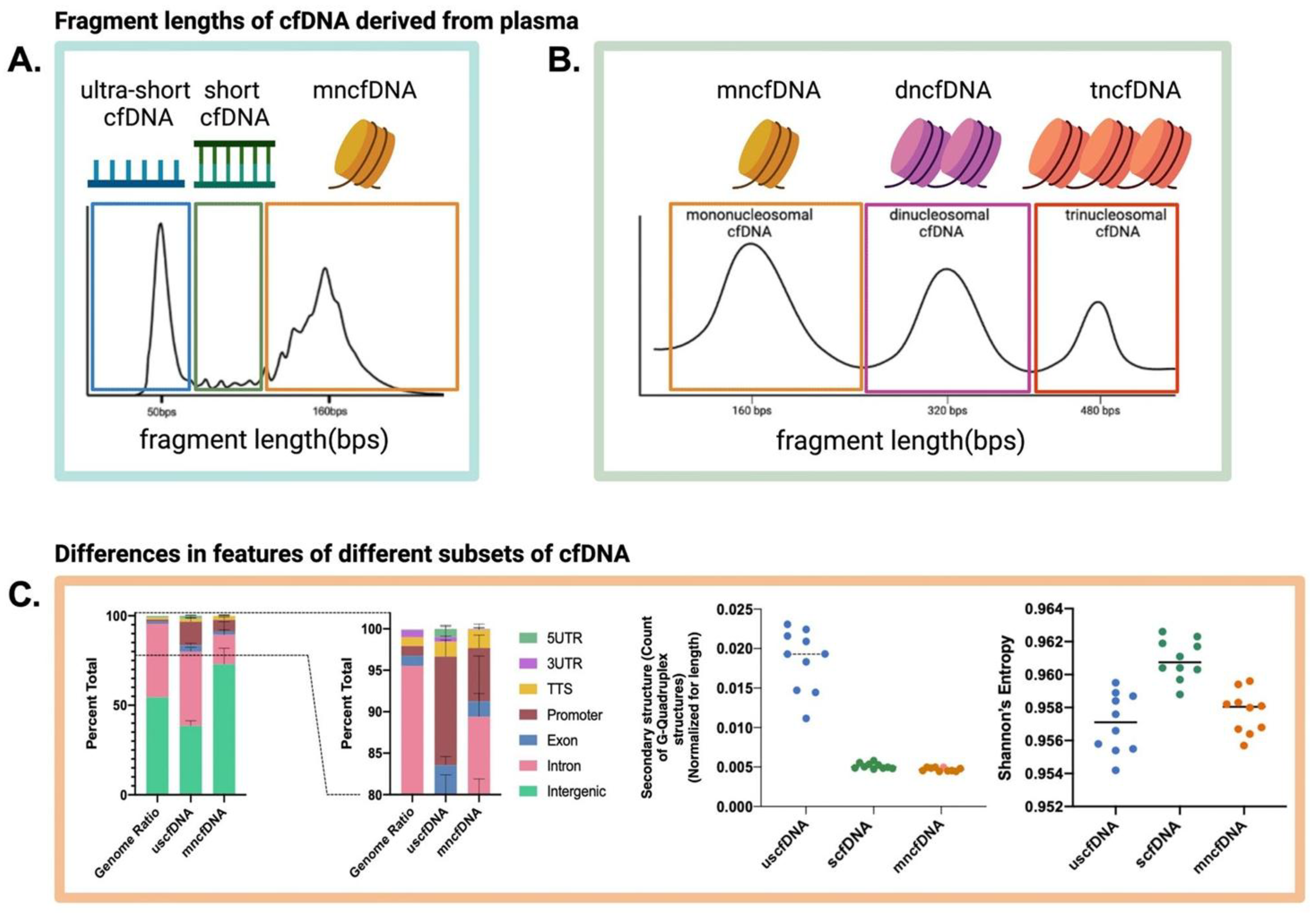

This principle is clearly visualized in the characteristic fragmentation profiles observed in the cfDNA analysis, which show distinct peaks corresponding to the fundamental packaging units of the genome (

Figure 4) [

19].

2.2. Epigenomic Aberrations and Stability Determinants

In addition to their physical structure, cfDNA and cfRNA fragments carry a deeper layer of information encoded in their epigenome [

19,

20]. These modifications, which regulate gene expression without altering the DNA sequence itself, are critical hallmarks of cancer and are faithfully preserved on the cfDNA released from tumor cells [

20,

26]. DNA methylation, the addition of a methyl group to cytosine bases (5mC), is a well-documented event in OSCC, where the hypermethylation of tumor suppressor genes is a key step in carcinogenesis [

20,

26,

27]. These aberrant methylation patterns can be detected in cfDNA from both saliva and plasma, offering a powerful, noninvasive tool for diagnosis and prognosis [

20,

26].

More recently, 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC), an oxidized derivative of 5mC generated by TET enzymes, has emerged as another vital epigenetic marker [

27]. In healthy tissues, 5hmC is enriched in transcriptionally active regions such as gene bodies and enhancers, playing a key role in gene regulation [

27]. A global loss of 5hmC is a recognized feature of many cancers and is often associated with more aggressive tumors and a poorer prognosis [

27]. Because 5hmC patterns are tissue- and cancer specific, their analysis in cfDNA provides a detailed signature that can help identify a tumor's tissue of origin and its malignant state [

25,

27]. The physical packaging of DNA also contributes to this epigenetic story; nucleosome positioning dictates which regions of the genome are accessible, influencing both fragmentation patterns and gene expression [

19,

22]. Thus, cfDNA fragment patterns, nucleosome footprints, and methylation/hydroxymethylation signatures are intrinsically linked, creating a multilayered biomarker that reflects both the genetic and epigenetic state of a tumor [

19,

27].

The ultimate utility of these biomarkers, however, depends entirely on their ability to survive the hostile environment of the oral cavity. Saliva is rich in various enzymes, including nucleases such as DNase I, that can rapidly degrade nucleic acids [

17,

21,

23]. Indeed, studies have shown that unprotected, exogenous DNA or RNA added to saliva is degraded within minutes [

21]. However, endogenous salivary cfDNA and cfRNAs are remarkably stable [

21,

23]. Salivary cfDNA shows a calculated ex vivo half-life of approximately 13–14 hours at room temperature, whereas in vivo cfDNA in blood is commonly estimated to have a half-life of 16 minutes to 2.5 hours [

22,

23]. This surprising stability is attributed to protective mechanisms that shield cfNAs from enzymatic attack [

21,

30].

A primary protective strategy is encapsulation within carrier vesicles [

18]. Extracellular vesicles, such as exosomes, are shed from cells and act as natural nanocarriers, and their lipid bilayer membranes form a robust shield around their nucleic acid cargo, protecting it from degradation [

18,

22]. Similarly, cfNAs can associate with macromolecular complexes, such as proteins and lipoproteins, which also provide protection [

21,

28]. A significant fraction of salivary RNA is associated with such complexes, as it cannot pass through fine-pore filters and is rapidly degraded upon exposure to detergents that disrupt these structures [

21]. The majority of extracellular DNA (exDNA; a subset of cfDNA) in saliva appears to be associated with larger structures such as cell debris and apoptotic bodies, as its concentration is dramatically reduced by high-speed centrifugation [

24]. This intricate interplay between nuclease activity and protective carrier mechanisms ultimately determines the half-life and integrity of cfNAs in saliva, shaping the quality of the biomarkers we seek to detect [

21,

24]. The resulting cfDNA molecules that survive this journey represent a rich substrate for diagnostics, carrying a dense, multilayered repository of information that spans their cellular origin, epigenetic state, and physical associations (

Figure 5) [

19].

2.3. Interactions with the Oral Microbiome and External Factors

The oral cavity is a dynamic ecosystem, a dynamic ecosystem where the subtle signals of early-stage disease must be distinguished from a torrent of physiological and environmental noise [

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51]. A primary source of this biological variability is the oral microbiome, a complex community of microorganisms whose composition is in constant flux, profoundly shaped by a host of external factors that act as significant confounders in diagnostic analyses [

39,

41]. Lifestyle choices, for example, are powerful modulators of this microbial landscape. Dietary patterns, ranging from high-sugar and carbohydrate intake to the consumption of nitrate-rich vegetables, actively select for different bacterial populations; high-sugar diets, for example, encourage the proliferation of acidogenic taxa such as

Streptococcus, which can lower salivary pH, whereas nitrate consumption can foster a healthier microbiome rich in

Rothia and

Neisseria [

37,

48,

50]. Tobacco use represents another potent disruptor, creating an anaerobic environment that depletes health-associated genera such as

Neisseria while promoting the growth of pathogenic communities, including

Fusobacterium, thereby inducing a state of dysbiosis that can obscure or mimic disease signatures [

35,

38,

39,

41]. Even the simple act of eating can introduce immediate confounding effects, with postmeal increases in plasma lipids potentially creating technical biases that reduce the measured concentration of circulating cell-free DNA (ccfDNA) [

47].

In addition to lifestyle, the very biology of the human body introduces a temporal layer of complexity through diurnal and circadian rhythms. The oral environment is not static over a 24-hour period; it ebbs and flows with the body’s internal clock [

40,

46,

49]. Compelling evidence has demonstrated that the oral microbiota itself possesses an endogenous circadian rhythm, with the relative abundance of key phyla such as

Proteobacteria and genera such as

Neisseria,

Fusobacterium, and

Streptococcus oscillating independently of eating or sleeping cycles [

40]. This intrinsic rhythmicity is mirrored in the host's inflammatory state and hormonal milieu; proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β and hormones such as cortisol exhibit clear diurnal patterns, typically peaking in the morning before gradually declining throughout the day [

36,

46,

49]. While some studies have not revealed a significant circadian influence on the total concentration of ccfDNA [

47], it is clear that the underlying biological landscape, from microbial composition to inflammatory activity, has constant, predictable fluctuations. This rhythmic biological noise poses a formidable challenge, as a sample taken in the morning may present a fundamentally different molecular signature than one taken in the evening from the same individual, complicating the establishment of stable diagnostic baselines.

To distinguish subtle pico-stage OSCC signatures from background biological variability, it is imperative to develop computational tools that can account for and mitigate these multifaceted confounders. Traditional batch effect correction algorithms, such as ComBat, which was designed for genomic data, often prove inadequate for the unique statistical properties of microbiome data, namely, its zero-inflated and overdispersed nature [

43,

45]. This has spurred the development of adaptive baseline algorithms specifically engineered to address this complexity. Approaches such as Conditional Quantile Regression (ConQuR) represent a significant advancement, employing a nonparametric, two-part model to remove batch effects directly from microbial read counts without making restrictive assumptions about the data's distribution [

45]. Similarly, other machine-learning tools, such as Procrustes and pyComBat, have been designed to correct for technical and cross-platform variations in RNA-seq and other high-throughput data [

32,

43]. These sophisticated frameworks move beyond simple normalization; they learn to disentangle true biological signals of interest from the predictable noise introduced by diet, smoking, and circadian rhythms, creating an adaptive baseline that is crucial for the high sensitivity and specificity required in early cancer detection [

42,

45,

51].

3. Assay Design and Analytical Engineering

3.1. Multiplex Capture Chemistry and Microfluidics

The development of a clinically viable liquid biopsy such as SalivaSense 2.0 hinges on solving a profound engineering challenge: the specific and efficient capture of infinitesimally small quantities of cell-free DNA (cfDNA) and cfRNA from saliva [

52,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57,

58,

59,

60,

61]. Saliva is a notoriously complex biofluid containing a mixture of genomic DNA from shed epithelial cells, a diverse oral microbiome, and various enzymes, including nucleases that actively degrade the very nucleic acids targeted for analysis [

53,

55]. the low concentration and fractional abundance of tumor-derived nucleic acids. For example, in blood plasma, the average concentration of cfDNA is approximately 30 ng/mL in healthy individuals, and the tumor-derived fraction (ctDNA) in cancer patients can be as low as 0.01% of this total [

54,

58,

61]. To overcome these obstacles, SalivaSense 2.0 is architected around an automated microfluidic platform. The design of such a platform draws from a diverse toolkit of biochemical techniques, each optimized for the challenging task of isolating rare nucleic acid targets from a complex medium. This approach is fundamental to achieving the precision required for clinical diagnostics, as it minimizes sample volumes, drastically reduces processing times, lowers the risk of cross-contamination, and ensures a standardized, reproducible workflow that is less dependent on operator skill [

52,

54].

At the heart of the assay’s capture technology are superparamagnetic beads, which serve as mobile solid-phase extraction (SPE) media [

52]. This strategy offers key advantages over static column-based methods, including a vast surface area for nucleic acid binding and compatibility with high-throughput automation, enabling the simultaneous processing of dozens of samples with minimal hands-on time [

56,

59]. The surface chemistry of these beads is tailored for maximum recovery. In addition to traditional silica-coated beads that bind nucleic acids under specific chaotropic salt conditions [

52,

54], SalivaSense 2.0 employs more advanced chemistry using amine-conjugated magnetic beads. These beads are activated by homobifunctional crosslinkers that covalently couple to primary amines on ligands or adapters; native DNA is captured predominantly via electrostatic/chaotrope-mediated interactions unless amine-modified DNA is used [

61]. This powerful dual-binding mechanism can complete the capture process in under 10 minutes and has been demonstrated to increase extraction efficiency by more than 50% compared with the QIAamp manual kit [

61].

To analyze a comprehensive panel of cancer-specific signatures simultaneously, the assay integrates a highly specific hybrid capture methodology. This is achieved by using pools of thousands of custom-synthesized, 5'-biotinylated single-stranded oligonucleotide baits designed to selectively capture all exons of target genes, specific introns involved in cancer-related fusions, and critical promoter regions [

57]. To analyze the epigenome, which provides powerful biomarkers for cancer detection and tissue-of-origin mapping [

53,

60], the platform is designed to be compatible with enrichment techniques such as immunoprecipitation or target capture with probes following bisulfite treatment [

60]. For stable capture of cfRNA, a notoriously fragile molecule, the system can employ established methods such as magnetic beads coated with oligo-dTs to bind eukaryotic mRNA [

52].

Rigorous analytical validation confirms the performance of this integrated system. The recovery efficiency, a critical metric for any liquid biopsy, is determined via spike-in experiments where known quantities of synthetic DNA are added to cfDNA-negative plasma [

54,

56,

59]. These validation studies show varied performance across platforms. For example, a manual platform (QIAamp) has demonstrated recovery efficiencies between approximately 52% and 80% depending on the study and input amount [

54,

56,

61]. While some automated platforms perform similarly or even below this range [

56], the implementation of optimized chemistries with homobifunctional crosslinkers has been shown to achieve recovery rates exceeding 93%, significantly outperforming the manual kit in a direct comparison [

61]. Crucially, the assay demonstrates excellent linearity across a wide dynamic range of inputs, from picogram to nanogram levels, with strong coefficients of determination (R² > 0.95) [

59]. This validated performance ensures that the assay can accurately and reliably quantify the faint molecular signals of cancer across the full spectrum of clinical presentations, from the earliest pico-stages to advanced disease.

3.2. Ultralow-Input Quantification and Nanopore Barcoding

The journey to detect oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) at its nascent, pico-stage begins with a formidable challenge: the profound scarcity of target molecules in a vast biological background. Cell-free DNA (cfDNA) and RNA extracted from saliva or plasma often yield mere nanograms of material, with the tumor-derived fraction representing a minuscule portion of the total [

62,

63,

64,

65,

66,

67,

68,

69,

70,

71,

72,

73,

74,

75,

76,

77,

78,

79]. This ultralow-input reality demands a paradigm shift in assay design, moving beyond conventional methods to embrace technologies that can amplify and quantify the faintest of molecular whispers. The narrative of modern diagnostics is thus one of amplification, where single molecules are given a powerful voice, enabling their detection against the noise of a complex sample matrix.

At the forefront are nucleic-acid amplification strategies for ultra-low input detection that bypass the need for cumbersome thermal cycling, making them ideal for point-of-care applications. Droplet digital PCR (ddPCR), which uses thermal cycling, has proven its mettle by partitioning a single sample into thousands of individual microreactors. This partitioning allows for the absolute quantification of rare genetic variants with exceptional sensitivity, successfully detecting TP53 mutations in head and neck cancer patients at fractional abundances as low as 0.01% [

71,

79]. In addition to PCR, rolling-circle amplification (RCA) offers a versatile isothermal engine that uses a circular DNA template and a highly processive polymerase to generate exceptionally long, repetitive DNA concatemers from a single binding event. This immense amplification factor transforms single-target recognition into a multitude of detectable reporter molecules, pushing detection limits into the picomolar range and providing a robust platform for nanopore-based immunoassays [

64,

74].

To further refine this ability, CRISPR–Cas systems have been ingeniously repurposed as triggers for amplification. In one such strategy, the Cas9 nickase, guided by specific sgRNAs, creates precise nicks in a DNA target to initiate a strand displacement amplification (SDA) cascade [

72,

73]. This method, known as CRISDA, leverages the exquisite specificity of Cas9 to launch a true isothermal reaction, achieving attomolar sensitivity and the ability to discriminate single-nucleotide differences without an initial heat denaturation step [

73]. These amplification technologies provide the critical first step: turning a handful of molecules into a detectable population. The next challenge is to read this information with single-molecule precision.

This is where the story turns to nanopore sequencing, a technology that provides direct, real-time, electrical readouts of individual nucleic acid molecules [

66,

67,

75]. As a single strand of DNA or RNA is driven through a protein nanopore, it produces a characteristic disruption in an ionic current, a molecular "squiggle" that can be decoded into its base sequence [

65,

66]. However, the inherently high error rate of this process has historically been a barrier to detecting rare variants. The solution lies in a powerful concept: reading the same original molecule multiple times. The CyclomicsSeq technique masterfully achieves this goal by circularizing and concatenating short cfDNA fragments before sequencing. The resulting long molecule contains many tandem copies of the original template, and by generating a consensus sequence from these copies, the base-calling accuracy is increased by an approximately ~60-fold, enabling the confident detection of mutations at frequencies as low as 0.02% [

75]. This principle of error correction, also known as the use of unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) in next-generation sequencing [

62], is complemented by the development of optimized nanopore barcoding protocols that allow for high-throughput, multiplexed analysis of numerous ultralow-input samples in a single run [

67]. Together, these innovations in amplification and single-molecule consensus sequencing construct a formidable toolkit, transforming the challenge of ultralow-input samples from an insurmountable barrier into a solvable engineering problem.

3.3. Sequencing and Signal-Integration Pipelines

Once the scarce molecular targets from a saliva sample have been amplified into a detectable signal, the subsequent challenge is to accurately sequence this material and integrate the complex data streams into a coherent, clinically actionable result. This requires a sophisticated fusion of sequencing platforms and analytical pipelines, each contributing a unique strength to the diagnostic narrative. The established workflows of Illumina short-read sequencing, particularly when coupled with targeted bisulfite or oxidative bisulfite sequencing, have long served as the bedrock for methylation analysis [

66,

68,

69]. These methods, while powerful, often rely on harsh chemical treatments such as bisulfite conversion, which can degrade the already limited cfDNA and cannot, on their own, distinguish between the crucial epigenetic marks of 5-methylcytosine (5mC) and 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC) [

66,

69,

70]. While modified protocols such as oxidative BS (oxBS-seq) and TET-assisted BS-seq (TAB-seq) were developed to resolve this ambiguity, they introduce additional complexity and potential for DNA damage, underscoring the need for a more direct approach [

66,

68].

Nanopore sequencing represents a direct approach, offering a revolutionary alternative that reads epigenetic modifications in their native state. As a DNA or RNA molecule traverses a nanopore, modified bases generate unique electrical disturbances, or "squiggles," that differ from their canonical counterparts [

66,

67]. The translation of this raw signal into a high-resolution epigenome map is a significant computational feat addressed by a growing ecosystem of specialized analytical tools. Pipelines built around software such as Megalodon, Nanopolish, DeepSignal, and Guppy employ advanced algorithms, from hidden Markov models to deep neural networks, to call the methylation status directly from electrical data [

65,

66]. Systematic benchmarking of these tools has been crucial, revealing top performers such as Megalodon and Nanopolish and paving the way for consensus strategies such as METEORE, which integrates outputs from multiple callers to increase accuracy and reliability [

65,

66]. This direct, conversion-free analysis not only preserves valuable sample material but also provides long-read information capable of phasing epigenetic marks across entire molecules.

Parallel to the evolution of sequencing, a new frontier is emerging in the form of electrochemical nanobiosensors, which push the limits of sensitivity and bring diagnostics to the point of care [

63,

64,

77]. These devices translate the molecular recognition of a methylated site into a direct, measurable electrical signal. The true power of this technology is unlocked through analytical engineering at the nanoscale. By modifying electrode surfaces with advanced nanomaterials, such as gold nanoparticles (AuNPs), reduced graphene oxide (rGO), or self-assembled DNA tetrahedra, the sensor performance can be dramatically improved [

76,

77,

78]. These nanostructures create a vastly increased surface area for capturing target molecules and enhance electronic signal transduction, enabling synergistic amplification schemes that can achieve attomolar detection limits [

78]. A key advantage of this platform is its capacity for a real-time, locus-aggregate methylation readout. Unlike sequencing, which requires extensive postacquisition data processing, an electrochemical biosensor provides a direct quantitative readout as a binding event occurs. For example, a sensor can be functionalized with methylation-specific antibodies conjugated to a nanocomposite; the binding of methylated cfDNA directly triggers a change in current, providing a real-time measure of the target's concentration [

76]. This integration of signal generation and detection into a single step is consistent with point-of-care use. The ultimate vision for SalivaSense 2.0 lies in the intelligent integration of these pipelines: leveraging the broad discovery power of Illumina and nanopore sequencing for comprehensive profiling while deploying electrochemical nanobiosensors for rapid, ultrasensitive, and cost-effective quantification of key validated biomarkers. This multimodal approach, where diverse data streams converge, is the cornerstone of building the robust translational pipelines necessary to achieve pico-stage oral cancer detection from the laboratory to the clinic.

4. AI-Enhanced Bioinformatics and Machine-Learning Pipelines

4.1. Preprocessing, Error Suppression and Methylation Calling

The journey from a raw saliva sample to a clinically actionable biomarker is paved with computational challenges that demand a sophisticated bioinformatic pipeline. The initial cfDNA and cfRNA sequences obtained from high-throughput technologies are not pristine signals but are instead fraught with noise, missing data, and systematic errors that can obscure the subtle epigenetic signatures of early-stage cancer [

80,

81,

82,

83,

84,

85,

86,

87,

88,

89,

90,

91,

92]. Therefore, the initial preprocessing and error suppression phase is not merely a procedural step; it is the foundational bedrock upon which the entire diagnostic framework is built. Traditional, simplistic methods for handling missing data, such as filling gaps with the mean or median value of a feature, risk distorting the underlying biological distributions and introducing noise that can mislead downstream analyses [

88]. To navigate this, advanced frameworks employ generative models such as generative adversarial imputation networks (GAINs), which transcend simple substitution by learning the complex, multidimensional relationships within the omic data. By training a generator to produce realistic data points and a discriminator to distinguish them from real data, these networks can impute missing values that are consistent with the learned feature distributions, thereby preserving the integrity of the dataset [

88].

In addition to missing data, the most formidable challenge in cfDNA analysis is the overwhelming background noise from sequencing artifacts, which can easily eliminate the subtle signals of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) [

91]. A groundbreaking strategy to overcome this problem is integrated digital error suppression (iDES), a dual-pronged approach that combines molecular and computational techniques to achieve unprecedented sensitivity [

91]. The first prong is molecular barcoding, where unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) are attached to each original DNA fragment before amplification. This allows every resulting sequence read to be traced back to its parent molecule, enabling the computational distinction between true biological variants and errors introduced during PCR or sequencing [

91]. The second prong is

in silico "background polishing." This involves creating a detailed error profile from a cohort of healthy individuals to model the highly recurrent, stereotypical background noise, often caused by oxidative damage during sample preparation, that plagues sequencing data. This background model is then used to computationally "polish" new samples by statistically removing artifacts that are indistinguishable from this established noise profile [

91].

Crucially, these two methods are synergistic. Molecular barcoding effectively eliminates random, stochastic errors while background polishing targets and eliminates the most common, position-specific artifacts. When combined, they achieve a remarkable ~15-fold reduction in error rates, increasing the fraction of error-free genomic positions from ~90% to ~98% [

91]. This dramatic increase in the signal–to–noise ratio pushes the limits of detection, enabling the identification of ctDNA at allelic fractions as low as 4 in 100,000 cfDNA molecules [

91]. Once these high-fidelity data are generated, methylation calling is performed by calculating per-read calls for each CpG site, which quantify the level of methylation and serve as the core input for subsequent machine learning models [

81,

90]. This meticulous pipeline of imputation, error suppression, and methylation calling transforms the raw, chaotic output of the sequencer into a clean, quantitatively precise dataset ready for the discovery of robust epigenetic signatures.

4.2. Multi-Omic Feature Selection and Integration

With a foundation of high-quality, denoised data, the next critical stage involves navigating the vast, high-dimensional landscape of the multiomic epigenome. The challenge shifts from cleaning the data to extracting meaning from it: selecting the most informative features and integrating them in a way that captures the intricate, synergistic interplay between different molecular layers. A brute-force approach, in which tens of thousands of features are fed into a model, is computationally intractable and risks "the curse of dimensionality," where models learn noise instead of true biological signals [

88,

92]. To counter this, a robust feature selection process is essential. While simple variance filters are common, they can be unstable and biased by outliers [

88]. A more rigorous method is robust feature selection (RFS), which employs bootstrap sampling, repeatedly creating subsets of the data, to identify features that are consistently ranked as important across these different perturbations. This ensures that the selected feature set is not an artifact of a specific data split but is truly stable and biologically relevant [

88]. Another powerful technique is the chi-square test, which can identify features that are statistically significantly associated with clinical outcomes, such as survival status [

85].

Once a stable feature set is identified, the challenge becomes one of integration. The simplest strategy, known as

early fusion, involves concatenating features from different omics (e.g., cfDNA methylation, cfRNA expression) into a single, long vector. However, this approach treats all features equally and often fails to capture the unique characteristics and hierarchical relationships between different data types [

88,

89]. At the other end of the spectrum is

late fusion, where separate models are built for each omic type and their final predictions are combined [

80,

89]. This preserves modality-specific patterns but may miss crucial cross–omic interactions. The frontier of innovation lies in intermediate fusion strategies that model the data's inherent structure, with

graph neural networks (GNNs) emerging as a particularly powerful paradigm [

80]. GNNs represent multiomic data as a biological network, where genes and other molecules are nodes and their interactions are edges. This approach explicitly models both intraomic (e.g., gene–gene) and interomic (e.g., miRNA–gene) connections, allowing models such as graph convolutional networks (GCNs) and graph attention networks (GATs) to learn from the biological context of the data [

85,

87]. GATs, in particular, can dynamically weigh the importance of different molecular interactions, offering a more nuanced feature extraction that has proven superior for complex classification tasks such as determining cancer molecular subtypes [

87].

Pushing this frontier even further are

transformer-based architectures, inspired by their revolutionary success in natural language processing [

89,

92]. Models such as DeePathNet leverage the transformer's self-attention mechanism, which allows the model to dynamically assess the importance of each feature in the context of all others, capturing complex, nonlinear dependencies [

92]. A key innovation of DeePathNet is its integration of domain-specific biological knowledge. Instead of learning from individual genes, it first encodes multiomic features into 241 literature-curated cancer pathways. The transformer then learns the interactions

between these pathways [

92]. This hierarchical approach is not only highly accurate but also inherently explainable. By analyzing the model's internal workings, it is possible to create

transformer-based explainable dashboards that highlight which specific pathways drive a prediction for an individual patient. This provides unprecedented interpretability, aligning model predictions with known biological processes and TCGA profiles, thereby moving beyond a "black box" prediction to deliver actionable, pathway-level biomarker insights [

92]. To navigate the vast landscape of potential model architectures and hyperparameters, automated machine learning (

AutoML) platforms can be employed. Tools such as H2O AutoML systematically train and evaluate a diverse array of models, from gradient boosting machines to deep neural networks and stacked ensembles, and rank them on a "leaderboard," streamlining the process of identifying the optimal algorithm for a given dataset and task [

82].

4.3. Cross-Cohort Harmonization and Federated Transfer Learning

The journey to develop a universally effective diagnostic tool from complex omics data begins by confronting two fundamental hurdles: data are fragmented across numerous institutions, and they are overwhelmingly derived from individuals of European ancestry [

93,

94,

95,

96,

97,

98,

99,

100,

101,

102,

103]. This reality creates significant "cohort bias", nonbiological variations arising from different scanners, lab preparations, and acquisition protocols, which can dramatically skew results and lead to models that fail when applied to new populations [

94,

95]. The poor transferability of predictive scores developed in one ancestral group to another, particularly from European to African ancestries, represents a critical barrier to equitable precision medicine, which threatens to exacerbate existing health disparities [

100,

103]. To dismantle these barriers, a sophisticated pipeline combining data harmonization with privacy-preserving federated learning is not only advantageous but also essential for building robust, globally deployable models.

The first crucial step is data harmonization, a computational process that retrospectively aligns datasets from diverse sources to create a cohesive and analyzable whole [

94]. This involves computationally adjusting for technical variability, ensuring that biological signals are not obscured by noise from different equipment or protocols [

94,

95]. With data made comparable, federated learning (FL) offers a transformative solution to the challenge of data silos. This decentralized paradigm allows multiple institutions to collaboratively train a single, powerful AI model without ever sharing raw, sensitive patient data [

93,

96,

99]. Instead of pooling data, each institution trains the model locally and shares only the resulting model parameters, which are then aggregated to create an improved global model [

93,

99]. This approach has proven remarkably effective, with studies on large-scale genomic data demonstrating that federated models can achieve predictive performance nearly identical to that of centralized models trained on pooled data, all while preserving patient privacy [

99].

To address ancestral disparities specifically and ensure global utility, the pipeline is elevated with federated transfer learning (FTL) [

96]. This advanced technique intelligently leverages the wealth of data from well-represented populations to increase predictive accuracy in underrepresented groups [

100]. By identifying and utilizing the genetic similarity shared between, for instance, European and African populations, FTL can adapt genetic effect sizes from the data-rich cohort to the target cohort, significantly improving the model's predictive power for non-European individuals [

100,

101]. For true global deployment where trust is paramount, the entire process is fortified with state-of-the-art privacy-preserving analytics. While standard FL prevents direct data sharing, sensitive information can still potentially be inferred from model updates [

93,

95]. Therefore, advanced cryptographic methods such as multiparty homomorphic encryption, which enables direct computation on encrypted data, and perturbation techniques such as differential privacy, which adds statistical noise to mask individual contributions, are integrated to provide end-to-end security without compromising model accuracy [

93,

98]. Finally, the powerful, harmonized insights generated from these secure federated systems can fuel the creation of open-data commons and large-scale, integrative biomedical knowledge graphs, creating a virtuous cycle where securely shared knowledge accelerates new discoveries for all populations [

96].

5. Validation Frameworks

5.1. Analytical benchmarks

Before SalivaSense 2.0 can be deployed in a clinical setting, its fundamental performance characteristics must be meticulously defined. This foundational stage of validation is guided by established principles, such as those outlined in the Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative Digital PCR Experiments (dMIQE) guidelines, which provide a crucial roadmap for ensuring accuracy, reproducibility, and transparency [

104,

105,

106,

107,

108,

109,

110,

111,

112,

113]. The initial challenge is to determine the absolute boundaries of the assay's capabilities, including its limit of detection (LOD), linearity, and reproducibility, which are essential for guaranteeing that the technology can reliably quantify the minute amounts of cfDNA and cfRNA characteristic of early-stage disease.

These benchmarks are established in a controlled environment, and well-characterized reference standards are used to create a pristine baseline. A validation workflow, for example, can employ commercially available cfDNA reference standards spiked into a clean matrix such as DNA-free plasma to systematically evaluate performance across a range of concentrations and sample input volumes [

113]. This process allows for the precise determination of linearity, where a strong linear correlation (e.g., R² ≥ 0.99) between the known input amount and the measured output confirms that the assay performs consistently and quantitatively across its dynamic range [

113]. The use of certified reference materials (CRMs), such as the NIST Standard Reference Material® 2372a, represents the gold standard in this process. These materials provide genomic DNA with certified values for both mass concentration (e.g., ng/µL) and copy number concentration, which are metrologically traceable to the International System of Units (SI) [

111]. By calibrating assays against these CRMs, it becomes possible to ensure not only precision but also trueness, allowing for the harmonization of results across different laboratories and platforms, a critical step for any diagnostic test intended for widespread use [

111,

112].

However, achieving linearity and a low LOD in a single laboratory is insufficient. True analytical robustness is demonstrated through reproducibility, a measure of how consistent the results are when variables are introduced. Interlaboratory and interoperator variability are significant hurdles in biomarker validation, often stemming from subtle differences in protocol execution [

110]. To combat this, validation frameworks must incorporate strategies to minimize human error and standardize procedures. The implementation of standardized operating procedures (SOPs) and the use of automated systems, such as robotic liquid handlers for RNA isolation and PCR setup, have been shown to dramatically reduce operator-induced variance and improve the correlation of results between different facilities, with correlation coefficients as high as 0.96 for some mRNA markers [

110]. Furthermore, conducting reproducibility studies where multiple independent operators perform the same extraction and analysis protocols on identical reference materials is a key validation step. Consistent yields, fragment size profiles, and cfDNA percentages between operators confirm the method's robustness and readiness for broader application [

113].

Once these core benchmarks are established, the assay must be challenged with interferent stress tests designed to mimic the complex, real-world conditions of the oral cavity. The mouth is not a sterile test tube; it is a dynamic environment teeming with substances that can inhibit PCRs, degrade nucleic acids, or contaminate the sample with nontumorous genetic material. One of the most significant challenges is exposure to tobacco tar. Cigarette smoke is a complex aerosol containing more than 9,500 chemical compounds, including a host of reactive oxygen species (ROS), carcinogenic organic compounds, and heavy metals such as cadmium [

106,

107]. These components can inflict direct oxidative damage on DNA and RNA while also potentially inhibiting the enzymatic reactions central to PCR-based assays, thereby compromising the integrity of the results [

106]. This intricate web of molecular damage, illustrated in (

Figure 6) [

106], underscores the necessity of stress-testing the SalivaSense 2.0 assay against tobacco exposure. The figure details how free radicals from smoke not only inflict direct DNA damage but also trigger inflammatory pathways and lipid peroxidation, all of which could introduce confounding signals that must be distinguished from the signature of OSCC.

Similarly, exposure to mouthwash and alcohol introduces another layer of complexity. Ethanol itself can disrupt cellular homeostasis, but its primary metabolite, acetaldehyde, is classified as a Group 1 carcinogen that readily forms DNA adducts [

105,

106]. Critically, rinsing the mouth with an alcoholic beverage can cause a rapid, dramatic spike in salivary acetaldehyde to levels exceeding 1,000 µM, far above the ~100 µM threshold considered mutagenic, even without swallowing [

105]. This short-term, high-concentration exposure from the beverage itself, independent of systemic metabolism, represents a potent interferent that can directly compromise the cfDNA and cfRNA targets that SalivaSense 2.0 is designed to detect. The mechanisms through which alcohol exerts this damaging effect are multifaceted and involve the generation of free radicals that drive protein oxidation, lipid peroxidation, and direct DNA damage, as depicted in (

Figure 7) [

106]. These pathways represent a significant source of biological noise that the assay must be robust enough to overcome.

Finally, the validation framework must account for biological interferents inherent to the oral cavity, most notably gingival crevicular fluid (GCF). GCF is a serum transudate that continuously flows from gingival tissues into the oral cavity, and its volume increases significantly with periodontal inflammation [

104]. This fluid is a rich source of host-derived cfDNA released from apoptotic and necrotic periodontal cells. Studies have shown that cfDNA concentrations in GCF are orders of magnitude higher than those in saliva or plasma and are positively correlated with the severity of periodontal disease [

104]. This influx of noncancer, inflammation-associated cfDNA presents a formidable challenge, as it can dilute the tumor-specific signal or, worse, generate background noise that could lead to false-positive results. Indeed, common comorbidities such as periodontitis are a primary source of this biological noise, resulting in a distinct and measurable profile of molecular biomarkers that can confound cancer-specific signals (

Figure 8) [

18].

Therefore, a pivotal part of the validation for SalivaSense 2.0 involves demonstrating that its multiplex signatures are specific enough to distinguish the epigenetic and transcriptomic fingerprints of OSCC from the considerable background of host cfDNA introduced by common comorbidities such as periodontitis. Successfully navigating these stress tests is what will ultimately prove the technology's clinical utility, transforming it from a promising concept into a life-saving diagnostic tool.

5.2. Clinical Validation Study Designs

Before a new diagnostic can be entrusted with patient lives, it must prove its mettle against the established "gold standard", in the case of oral cancer, the definitive histopathological examination of a tissue biopsy [

114,

115,

116,

117,

118,

119,

120,

121,

122,

123]. The validation framework for SalivaSense 2.0 is envisioned as a multiact drama, beginning with controlled, retrospective inquiries and culminating in real-world prospective trials that simulate its ultimate clinical application.

The initial act of this validation story often unfolds through

retrospective case–control studies, which provide a powerful and efficient means of initial assessment. In this design, archived saliva samples from individuals with confirmed oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) are compared against those from noncancerous groups, including healthy individuals and patients with oral potentially malignant disorders (OPMDs) [

114,

122]. A crucial element here is the establishment of orthogonal concordance, where the novel biomarker's performance is cross-validated against an established technology, such as comparing a rapid, point-of-care test to a laboratory-based ELISA on the same cohort of samples [

114]. This dual-assay approach ensures that the biomarker signal is robust and not an artifact of a single detection method. To build unwavering confidence, these studies must incorporate blinding, where laboratory analysts are unaware of the clinical diagnosis of the samples they are processing. This safeguard is essential to prevent operator bias from influencing the results [

115]. The narrative is further strengthened by expanding the investigation to include

blinded external cohorts, where samples are collected and analyzed by different clinicians and technicians at multiple, independent institutions. Successfully replicating a test's high sensitivity and specificity across different sites and operators demonstrates that its performance is not confined to a single specialized center but is generalizable and reproducible in diverse clinical settings [

115].

The final act of clinical validation transitions from looking back at past cases to looking forward to

prospective screening trials. These studies represent the ultimate test of a biomarker's utility, moving it into the real-world setting where it is intended to be used [

116]. Such trials are strategically designed to enroll high-risk populations, individuals with a history of tobacco and/or alcohol use, or betel quid chewing, who stand to benefit most from early detection [

119,

121]. In this framework, participants are screened with SalivaSense 2.0 at regular intervals, and every suspicious finding is referred to as the definitive histopathology gold standard [

115,

119]. This design not only confirms the biomarker's ability to identify early-stage cancers and precancerous lesions in a real-world screening context but also allows for the assessment of crucial performance metrics such as the positive predictive value (PPV), the probability that a positive test result correctly identifies the presence of disease [

114]. While these prospective trials are resource intensive and require long-term follow-up, they are the indispensable final step to prove that a biomarker can truly change clinical outcomes, reduce mortality, and earn its place in the standard of care [

119,

121].

5.3. Health-Economic Modeling and Decision-Curve Analysis

A clinically validated test is only truly translational if it offers clear value to patients, clinicians, and the healthcare system. Demonstrating this value requires moving beyond traditional metrics of sensitivity and specificity to the sophisticated realms of health-economic modeling and decision curve analysis (DCA). This stage of the validation journey answers the critical questions: "Is SalivaSense 2.0 a wise investment for our health resources?" and "Will it actually lead to better clinical decisions?"

To address the first question, cost–utility analyses are performed via powerful simulation tools such as Markov models [

119,

120]. From a societal or healthcare system perspective, these models project the long-term consequences of implementing a new screening program over a patient's lifetime [

121]. By integrating data on disease progression, treatment costs, and quality of life, they estimate outcomes in terms of quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) gained and calculate the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER), the additional cost for every QALY gained [

120,

121]. This allows for a direct comparison of value for money. These models are not monolithic; they are used to conduct detailed scenario analyses, exploring different implementation strategies to find the optimal path forward. For example, models can compare mass screening of the general population versus targeted screening of high-risk groups or evaluate the cost-effectiveness of different screening intervals (e.g., every 3, 5, or 10 years) [

121]. Furthermore, these frameworks can generate crucial equity impact projections and budget impact analyses, estimate the financial consequences of a nationwide rollout and ensure that the proposed strategy is not only cost-effective but also affordable and accessible, particularly in resource-constrained settings [

119,

121].

Complementing economic evaluations, decision curve analysis (DCA) offers a revolutionary way to assess a biomarker's clinical usefulness from the decision maker's perspective [

117]. DCA quantifies the "net benefit" of using a test by weighing the benefit of detecting a true cancer against the harm of an unnecessary biopsy for a false positive [

118]. This calculation is performed across a range of "threshold probabilities," which represent how a clinician or patient might weigh those risks and benefits [

117]. The result is a simple curve that visually demonstrates whether using the test to guide decisions is superior to default strategies such as "biopsy all suspicious lesions" or "biopsy none" [

117,

118]. A test that shows a greater net benefit across a wide range of reasonable clinical preferences is one that can be confidently integrated into practice. To accelerate the collection of evidence needed for both robust clinical validation and these complex economic models, the field is embracing innovative clinical trial designs. Adaptive designs for diagnostics, for example, represent a paradigm shift. These patient-centric designs can evaluate multiple therapies or diagnostics across various biomarker-defined subgroups simultaneously, allowing for modifications as the trial progresses [

116]. This flexibility enables researchers to stop futile arms early and focus resources on promising avenues, thus facilitating the rapid evidence generation required to bring transformative technologies such as SalivaSense 2.0 to the patients who need them most quickly than ever before [

116].

6. Translational Pipeline and Implementation Science

6.1. Point-of-Care Device Architectures and Sample Logistics

The journey of diagnostic technology from a centralized laboratory to a point-of-care (POC) setting is a tale of miniaturization, simplification, and ingenuity [

124,

125,

126,

127,

128,

129,

130,

131,

132,

133,

134,

135,

136,

137,

138,

139]. For a platform such as SalivaSense 2.0 to achieve its potential in early cancer detection, it must escape the confines of the traditional lab, shedding its reliance on bulky equipment and highly trained personnel [

131]. The key to this transformation lies in sophisticated yet accessible device architectures that place powerful analytical capabilities directly into the hands of clinicians and patients [

137]. At the heart of this revolution is the microfluidic "lab-on-a-chip," a device that manipulates minute volumes of fluid within microchannels to perform complex tasks such as sample preparation, amplification, and detection [

124,

131]. These platforms, often fabricated from low-cost materials such as paper or polymers via techniques such as 3D printing, offer a cascade of advantages: they require minimal samples, shorten processing times, increase maneuverability, and reduce costs, making them ideal for onsite diagnostics [

124,

130,

139].

A significant hurdle for any nucleic acid-based POC test is the need for precise temperature control, as amplification methods such as LAMP or RPA require stable, elevated temperatures [

131]. The traditional solution, an external electrical heater, compromises the instrument-free ideal of POC diagnostics [

131]. A truly innovative pathway forward borrows a concept from an unexpected source: smart food packaging [

131]. Commercially available self-heating methods can use controlled exothermic reactions, such as the hydration of calcium oxide, to generate heat without any external power [

131]. By integrating these chemical heaters with phase change materials (PCMs) that absorb and store thermal energy, it is possible to create a disposable, electricity-free heating module capable of approximating the target temperatures needed for isothermal amplification; feedback control or calibration may be required for precise operation [

131]. This self-contained thermal management system represents a critical step toward a fully autonomous diagnostic cartridge [

131].

The final piece of the POC architecture is the reader, and the modern smartphone has emerged as a surprisingly powerful and ubiquitous tool for this purpose [

137]. Equipped with high-resolution cameras, substantial processing power, and wireless connectivity, smartphones can be transformed into sophisticated diagnostic readers with the help of simple, low-cost attachments [

137]. For optical biosensors, the phone camera can capture colorimetric or fluorescent signals, which are then quantified by a custom app to determine biomarker concentrations [

130,

137]. Similarly, in electrochemical systems, a portable detector can interface with a smartphone via Bluetooth to process signals and display results in real time [

137]. This integration not only makes the system portable but also connects it to the cloud, enabling data sharing, remote analysis, and the application of machine learning algorithms to increase diagnostic accuracy [

127,

137].

Beyond the device itself, the logistics of sample handling must be reimagined for remote and resource-limited settings. Saliva is notoriously complex, and its enzymatic components can quickly degrade target biomarkers such as cfDNA and cfRNA [

129,

130]. While preservatives are an option, an elegant solution for remote shipping is the use of dried saliva spots (DSSs) [

129]. In this method, a saliva sample is applied to filter paper and allowed to dry, a process that stabilizes nucleic acids and proteins by suppressing enzymatic degradation [

125,

129]. These dried spots can remain stable for up to a month at various temperatures, eliminating the need for cold-chain transport and allowing samples to be safely mailed from a patient's home to a central laboratory for analysis [

129]. This simple yet robust technique democratizes access, ensuring that a patient's geographical location is no longer a barrier to receiving advanced molecular diagnostics [

129,

131].

6.2. Training, Adoption, and Equity Roadmap

The successful translation of SalivaSense 2.0 from a technological marvel to a clinical standard hinges on a carefully orchestrated implementation strategy that prioritizes user training, equitable adoption, and community trust [

133,

136]. A novel diagnostic, regardless of its precision, will fail if clinicians are not confident in its use, if patients do not trust its purpose, or if systemic barriers prevent its reach into underserved communities [

138]. Therefore, a robust roadmap must address the human elements of adoption with the same rigor applied to the device’s technical design. A critical first step is ensuring standardized and high-quality sample collection, which can be achieved through innovative training modalities such as augmented reality (AR) [

128,

132]. AR-guided tutorials can overlay digital instructions onto a user’s view of the real world, providing an immersive, step-by-step guide to the saliva collection process [

128]. By enabling an expert to offer spatially aligned visual guidance from the learner’s point-of-view, AR can simplify complex procedures and ensure that both clinicians and patients can collect samples correctly, a foundational requirement for accurate results [

132].

Beyond initial sampling, widespread adoption requires a concerted effort to upskill the broader clinical workforce [

133]. Many health practitioners report limited training and confidence in specialized fields, a gap that can be effectively addressed through large-scale, accessible e-learning programs [

133]. A national training initiative that provides government-funded, evidence-based modules on the principles of salivary liquid biopsy and the clinical utility of SalivaSense 2.0 would be essential for improving clinician knowledge, building confidence, and attracting new providers to the field [

133]. This educational outreach must extend into the community through creative and culturally resonant engagement strategies that build trust where it has been historically eroded [

135,

136]. Programs that embed health education within welcoming, nonclinical community activities can lower emotional barriers, foster open dialog, and humanize public health messaging around sensitive topics such as cancer [

135]. By meeting communities where they are, both geographically and culturally, such initiatives transform outreach from a transactional moment into a trust-building experience [

135].

Finally, this entire pipeline must be built on a foundation of equity [

138]. This requires moving beyond a one-size-fits-all approach to consent and result delivery and instead developing pathways that are culturally tailored and codesigned with the communities they are meant to serve [

134,

136]. For genomic testing, informed consent is a complex process, and materials must be accessible to individuals with varying levels of health and digital literacy [

134]. Dynamic consent platforms (DCPs) offer a promising digital solution, providing layered information through multiple modalities, but concerns remain about their accessibility for vulnerable populations who may lack internet access or digital literacy [

134]. To ensure equity, both digital and nondigital consent options must be available, supported by patient navigators, who can help address language, financial, and cultural barriers [

134,

136]. Ultimately, a successful translational pipeline ensures not only that the technology works but also that it works for everyone, fulfilling the promise of precision medicine by making advanced diagnostics accessible to all populations [

138].

6.3. Regulatory and Data-Governance Pathways

The journey of a novel diagnostic such as SalivaSense 2.0 from a validated concept to a clinical tool is a trek through a complex and evolving international regulatory landscape [

140,

141,

142,

143,

144,

145,

146,

147,

148,

149,

150,

151,

152,

153,

154,

155]. Successfully navigating this requires a multifaceted strategy that addresses distinct approval pathways, stringent data security mandates, and profound ethical considerations regarding patient data.

In the United States, a promising route is the Food and Drug Administration's (FDA) Breakthrough Devices Program, a voluntary pathway designed to expedite the development, assessment, and review of medical devices that offer more effective diagnosis or treatment of life-threatening or irreversible debilitating conditions [

154]. This program provides manufacturers with more frequent interactions with FDA experts and prioritized review, accelerating patient access to innovative technologies [

154]. Across the Atlantic, the European Union (EU) presents a dual challenge with the In Vitro Diagnostic Medical Devices Regulation (IVDR) and the new AI Act [

149,

150]. The IVDR establishes a stringent, risk-based framework for devices used to examine human samples, such as genetic screening tools [

150]. Layered on top, the AI Act classifies AI-enabled medical devices as "high risk," imposing demanding obligations for risk management, data governance, transparency, and human oversight [

149,

150]. This creates a dual conformity assessment that can be particularly burdensome for SMEs [

150]. For global health applications, especially in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) with less developed domestic regulatory frameworks, the World Health Organization's (WHO) Prequalification of In Vitro Diagnostics (PQDx) program serves as a critical gateway, ensuring access to safe, appropriate, and affordable diagnostics [

140]. Underpinning all these pathways is the nonnegotiable requirement for robust cybersecurity. Both the FDA and the EU AI Act mandate that cybersecurity is integral to device safety, requiring a "Secure Product Development Framework" (SPDF) and resilience against threats that could compromise device function and lead to patient harm [

149,

151].

Beyond the device itself, the governance of patient data presents an equally complex frontier. Traditional "broad consent" models are being challenged by more patient-centric approaches such as "dynamic consent" [

142]. Implemented via digital platforms, dynamic consent aims to create an ongoing partnership, allowing participants to make granular, study-specific decisions about how their data are used over time [

141,

142]. While this model enhances participant control and transparency, its implementation faces challenges, including low uptake rates in some studies and the risk of "consent fatigue" [

141,

142]. A further challenge arises from the powerful capabilities of next-generation sequencing: the potential for incidental discovery of pathogenic germline variants (PGVs) unrelated to the primary diagnostic goal [

144]. The management of these secondary findings, which may reveal predispositions to hereditary cancers or other serious conditions, requires a carefully structured pipeline [

143,

144]. Although some assays filter out most germline alterations, they may still report clinically significant variants in genes such as

BRCA1 and

BRCA2 [

152]. This underscores the critical need for clear protocols that emphasize that such tests are not a replacement for dedicated germline testing and mandate that suspected PGVs trigger a referral for confirmatory testing and professional genetic counseling [

144,

152].

7. Ethical, Social and Policy Considerations

The revolutionary potential of SalivaSense 2.0, a promising technology for detecting oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) at its nascent, pico-stage, extends far beyond the laboratory bench. As we stand on the cusp of integrating such powerful diagnostic tools into clinical practice, we must navigate a complex terrain of analytical hurdles, data governance challenges, and profound social responsibility to ensure equitable access and benefit. The journey from a promising multiplex signature to a globally trusted diagnostic requires deliberate and thoughtful engagement with the ethical, social, and policy dimensions of genomic medicine, especially as the potential applications for salivary biomarkers extend far beyond a single disease to encompass a wide array of systemic conditions (

Figure 9) [

18].

7.1. Analytical Pitfalls and Biological Noise Mitigation

The promise of detecting OSCC at the pico-stage via noninvasive saliva samples is a monumental leap forward, yet its realization hinges on overcoming a formidable analytical challenge: discerning the ultra-low-abundance signal of early cancer from a cacophony of biological and technical noise [

156,

157,

158,

159,

160,

161,

162,

163,

164,

165,

166,

167,

168,

169,

170,

171,

172]. Liquid biopsy analytes, particularly cell-free DNA (cfDNA) and cell-free RNA (cfRNA), are present in vanishingly small quantities in early-stage disease, allowing their detection akin to finding a needle in a haystack [

158,

169,