Submitted:

31 October 2025

Posted:

03 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. E-Nose Devices

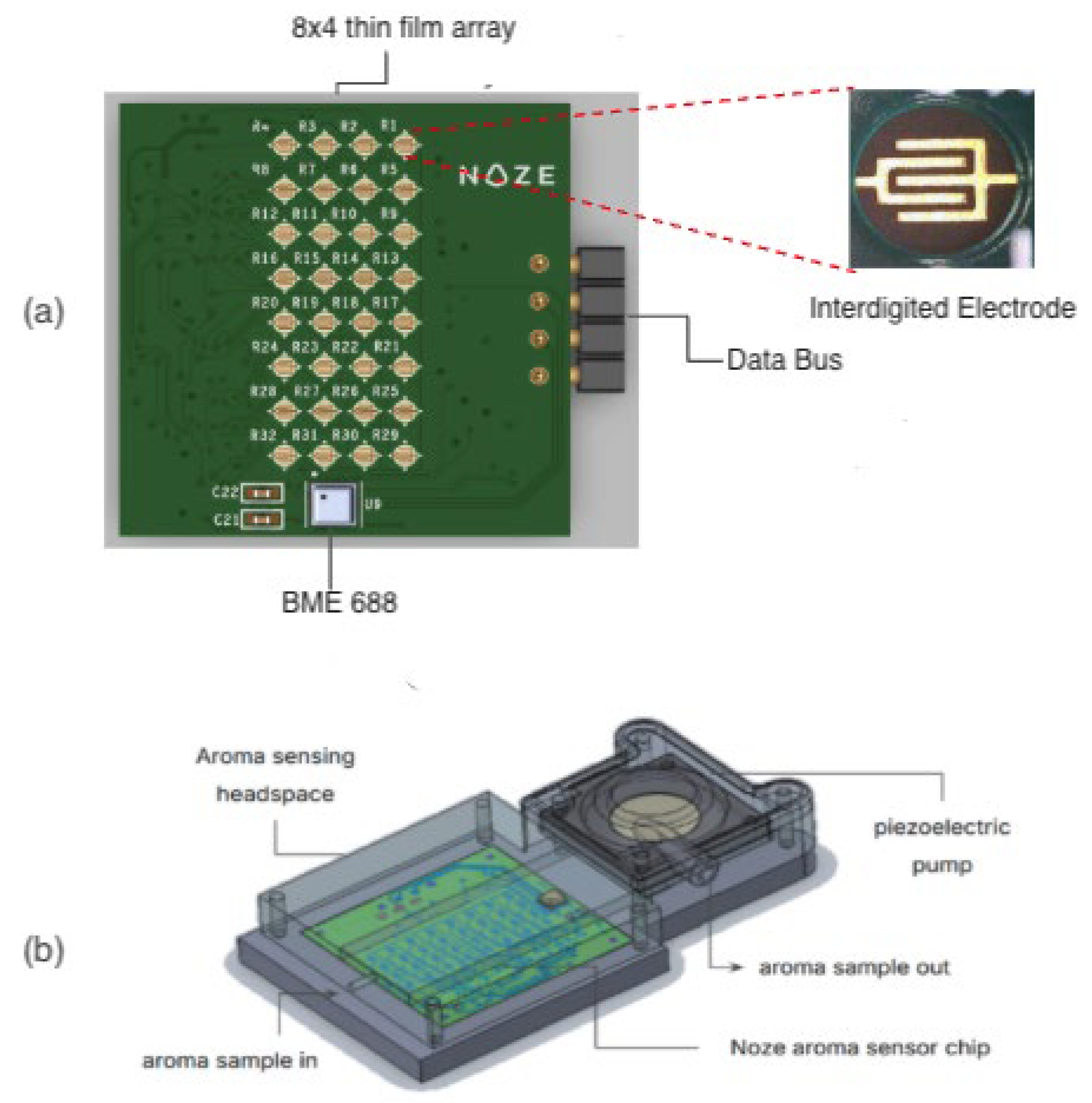

2.1.1. Chemiresistive Sensing Array Chip

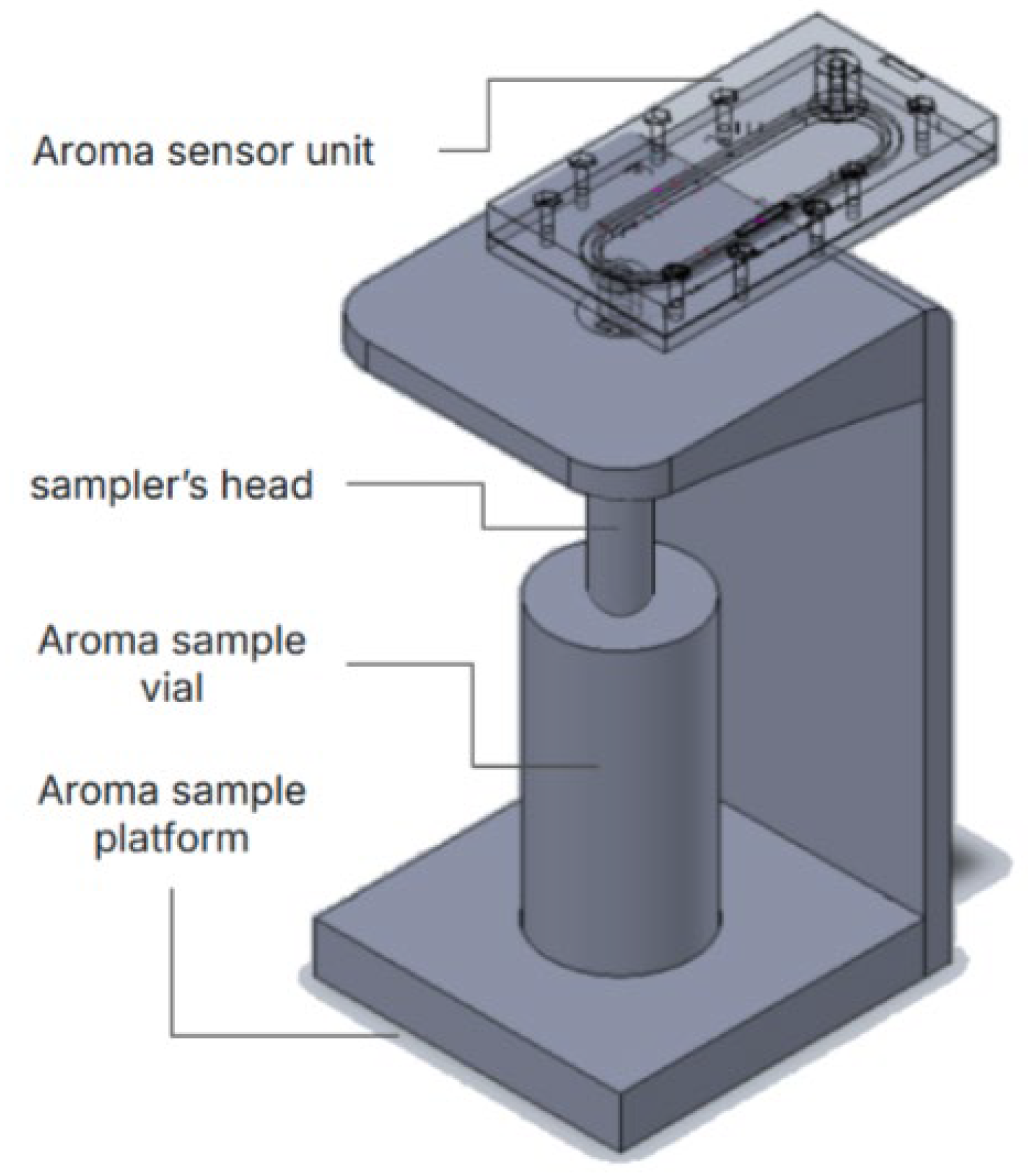

2.1.2. Vial-Based Aroma Sampler Setup

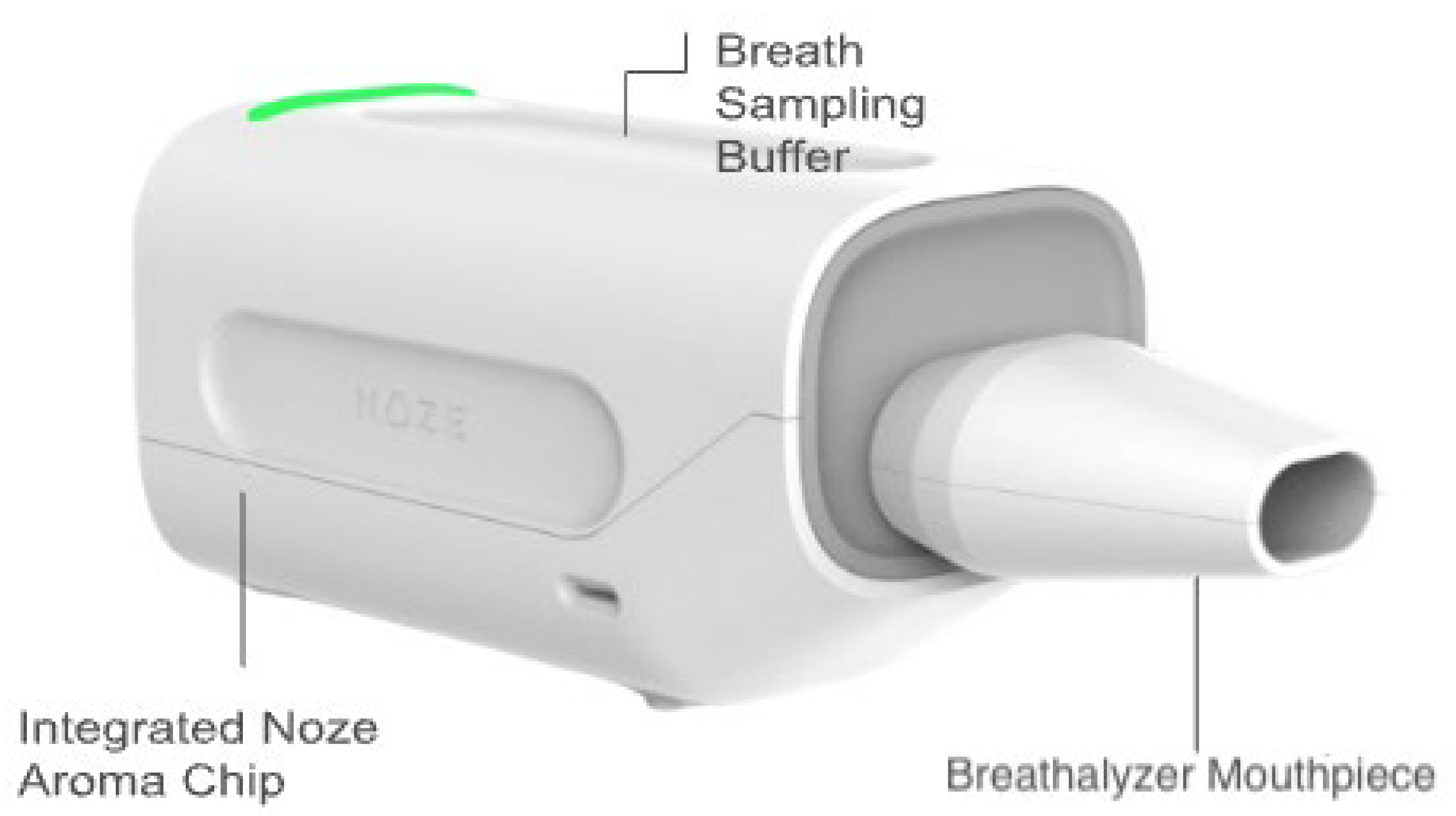

2.1.3. Breathalyzer Device Setup

2.2. Description of the Experiments

2.2.1. Acetone Headspace

2.2.2. Ketogenic Breath

2.2.3. Peppermint Breath

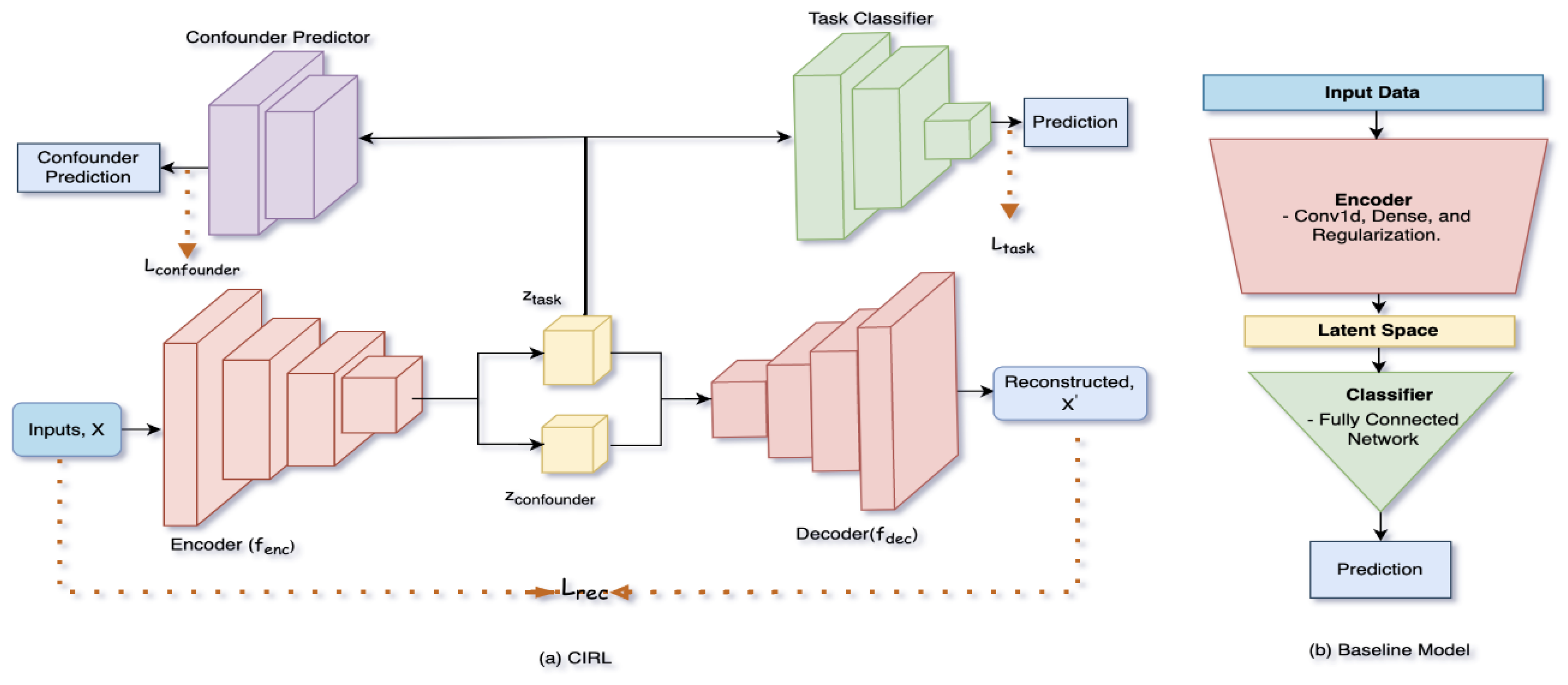

2.3. Confounder-Invariant Representation Learning (CIRL) Method

2.3.1. Conceptual Framework

2.3.2. Model Architecture

- Encoder (): A series of temporal convolutional layers that maps the input sensor data X into two separate latent spaces: a task-relevant space and a confounder space

- Decoder (): A series of transsposed convolutional layers that reconstructs the original input signal from both latent spaces, forcing the model to learn a complete representation.

- Classifier and Confounder Predictor: The task classifier uses only the purified to predict the task label. The confounder predictor attempts to predict the humidity signal from

2.4. Training and Optimization

- Reconstruction Loss (): Ensures the decoded signal accurately reconstructs the original input.

- Task Loss (): Ensures the task-relevant latent space is predictive of the target label.

- Confounder Loss (): Used adversarially. While the confounder predictor minimizes this losss to find humidity information, the encoder is trained to maximize it, forcing the encoder to make invariant to humidity.

- The parameter emphasizes reconstruction fidelity, where a higher weight (e.g., 1.0–2.0) ensures accurate reconstruction of sensor signals. However overemphasis risks retaining humidity information in , reducing humidity-invariance representation.

- The parameter controls the importance of learning task-relevant attributes, and hence underweighting it can lead to poor task performance.

-

The parameter encourages learning humidity-invariant attributes alongside retaining task-relevant information, however, setting it to an excessive weight (e.g. >0.5) may disrupt task-relevant attribute encoding.

- The training and optimization pseudocode as follows:

- Input: Data , confounders , labels , initial , , and

- Initialize , , and with random weights

- Initialize an optimization method with a suitable learning rate for , and

- Initialize a different optimization method with an appropriate learning rate for

-

For each epoch:

- (, )

- ,

- Compute as a chosen distance metric between and

- Compute as a selected error measure between and

- Compute as a chosen error measure between and

- Update , , to minimize with their optimization method

- Update to maximize with its optimization method and gradient reversal

- Optionally adjust using

- End For

2.5. Data Preprocessing

- Ambient Normalization: Each sensor's response was normalized using the formula: . This normalization strategy preserves the relative magnitude of sensor responses while compensating for inter-sensor variability and baseline drift.

- Temporal Sequence Truncation: Input sequences are truncated at the recovery phase terminus plus 60 seconds, capturing the complete VOC desorption dynamics while eliminating uninformative tail regions. This fixed-window approach ensures consistent temporal context across samples, encompassing baseline (30s), exposure (30s), and recovery phases (50s + 60s buffer), totaling approximately 170 timesteps at 1Hz sampling.

- Zero-Padding: To maintain uniform tensor dimensions required for batch processing in convolutional architectures, sequences shorter than the maximum length are right-padded with zeros post-recovery phase. This post-sequence padding strategy preserves temporal causality and prevents the introduction of artificial signal artifacts during convolution operations, as the padded regions are effectively masked by the learned kernels' receptive fields.

2.6. Experimental Setup and Evaluation

3. Results

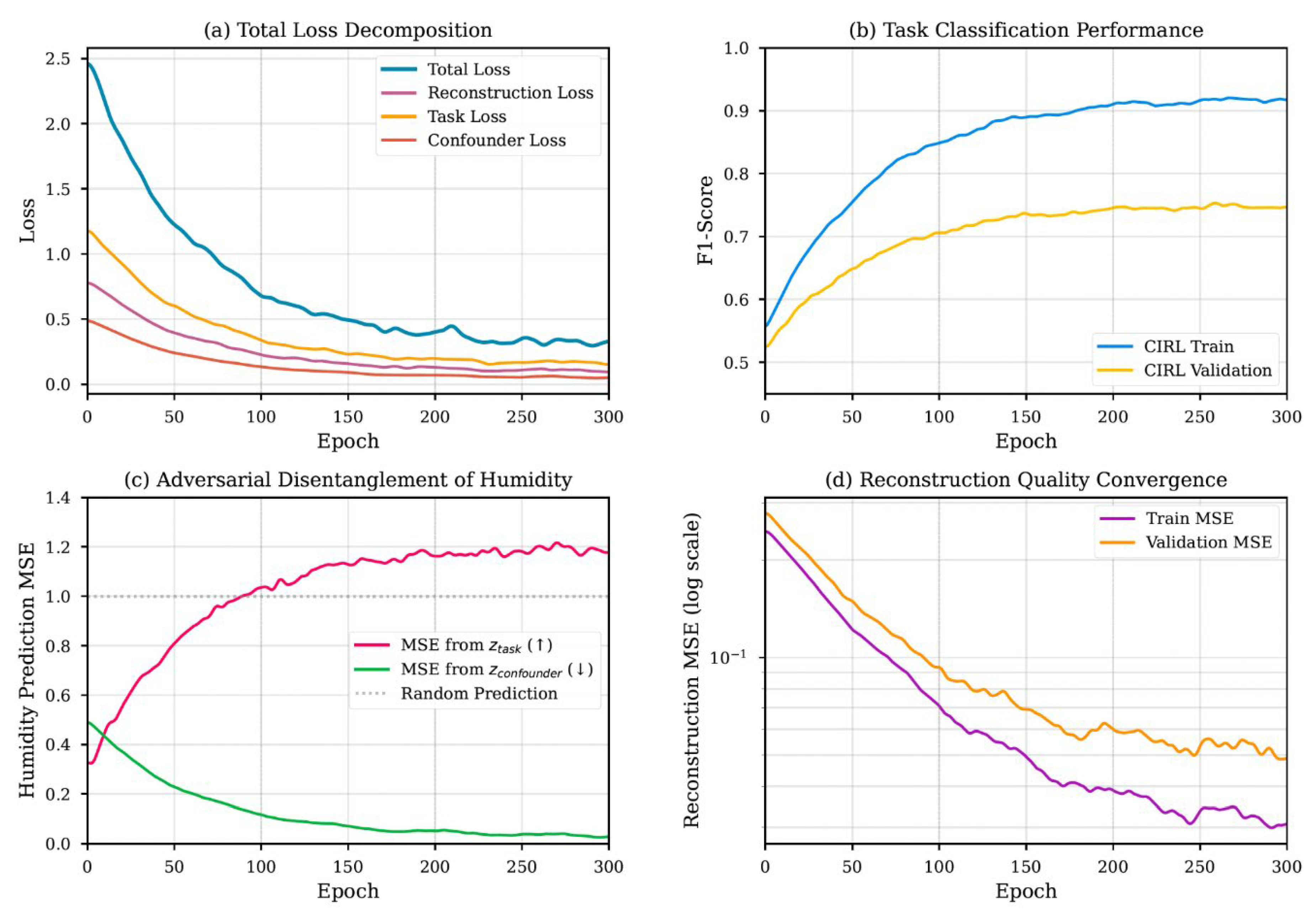

3.1. Training Dynamics and Model Convergence

3.2. Quantitative Evaluation of Disentanglement

3.3. Classification Performance

3.4. Ablation Study

4. Discussion

- Improve Reproducibility and Standardization: It reduces a major source of inter-sample and inter-device variability, a critical barrier that has stalled the clinical adoption of e-nose technology.

- Enhance Feasibility of Point-of-Care Screening: By making the device more robust to the uncontrolled ambient humidity of a clinical setting, it lowers the need for complex and costly environmental controls, making widespread deployment more practical.

- Increase Reliability in Longitudinal Studies: By correcting for short-term humidity-induced drift, CIRL can improve the reliability of monitoring disease progression or treatment response over time, where distinguishing true biological change from instrumental variation is paramount. Furthermore, the CIRL framework is sensor-agnostic. While we used a nanocomposite array, the principle can be applied to any e-nose technology (e.g., MOS, CP, QCM) that is susceptible to humidity that can be measured with a dedicated humidity sensor, and/or other measurable confounding factors.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A: Theoretical Framework for CIRL

Appendix A.1. Problem Formulation and Information-Theoretic Definitions

Appendix A.2. Disentanglement, Identifiability, and Theoretical Guarantees

Appendix A.3. Optimization as an Information Trade-Off

Appendix A.4. Generalization Bound

References

- Arshak, K.; Moore, E.; Lyons, G.M.; Harris, J.; Clifford, S. A Review of Gas Sensors Employed in Electronic Nose Applications. Sens. Rev. 2004, 24, 181–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rath, R.J.; Farajikhah, S.; Oveissi, F.; Dehghani, F.; Naficy, S. Chemiresistive Sensor Arrays for Gas/volatile Organic Compounds Monitoring: A Review. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2022, 2200830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuchmenko, T.; Lvova, L. A Perspective on Recent Advances in Piezoelectric Chemical Sensors for Environmental Monitoring and Foodstuffs Analysis. Chemosensors (Basel) 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askim, J.R.; Mahmoudi, M.; Suslick, K.S. Optical Sensor Arrays for Chemical Sensing: The Optoelectronic Nose. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebicki, J. Application of Electrochemical Sensors and Sensor Matrixes for Measurement of Odorous Chemical Compounds. Trends Analyt. Chem. 2016, 77, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dung, T.T.; Oh, Y.; Choi, S.-J.; Kim, I.-D.; Oh, M.-K.; Kim, M. Applications and Advances in Bioelectronic Noses for Odour Sensing. Sensors (Basel) 2018, 18, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, A.; Han, Y.; Li, T. Sensors Based on Conductive Polymers and Their Composites: A Review. Polym. Int. 2020, 69, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, B.C.; Steinthal, G.; Sunshine, S. Conductive Polymer-carbon Black Composites-based Sensor Arrays for Use in an Electronic Nose. Sens. Rev. 1999, 19, 300–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, N.S. Comparisons between Mammalian and Artificial Olfaction Based on Arrays of Carbon Black-Polymer Composite Vapor Detectors. Acc. Chem. Res. 2004, 37, 663–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalini Devi, K.S.; Anantharamakrishnan, A.; Maheswari Krishnan, U. Expanding Horizons of Metal Oxide-based Chemical and Electrochemical Sensors. Electroanalysis 2021, 33, 1979–1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freddi, S.; Sangaletti, L. Trends in the Development of Electronic Noses Based on Carbon Nanotubes Chemiresistors for Breathomics. Nanomaterials (Basel) 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moura, P.C.; Ribeiro, P.A.; Raposo, M.; Vassilenko, V. The State of the Art on Graphene-Based Sensors for Human Health Monitoring through Breath Biomarkers. Sensors (Basel) 2023, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldini, C.; Billeci, L.; Sansone, F.; Conte, R.; Domenici, C.; Tonacci, A. Electronic Nose as a Novel Method for Diagnosing Cancer: A Systematic Review. Biosensors 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yockell-Lelièvre, H.; Philip, R.; Kaushik, P.; Masilamani, A.P.; Meterissian, S.H. Breathomics: A Non-Invasive Approach for the Diagnosis of Breast Cancer. 2025, 12, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, A. Advances in Electronic-Nose Technologies for the Detection of Volatile Biomarker Metabolites in the Human Breath. Metabolites 2015, 5, 140–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, A.D. Application of Electronic-Nose Technologies and VOC-Biomarkers for the Noninvasive Early Diagnosis of Gastrointestinal Diseases. Sensors (Basel) 2018, 18, 2613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbiani, S.; Lotesoriere, B.J.; Dellacà, R.L.; Capelli, L. Physical Confounding Factors Affecting Gas Sensors Response: A Review on Effects and Compensation Strategies for Electronic Nose Applications. Chemosensors (Basel) 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, M.; Xu, S.; Zhou, X.; Lü, H. Electronic Nose Humidity Compensation System Based on Rapid Detection. Sensors (Basel) 2024, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, Z.; Tian, F.; Yang, S.X.; Zhang, C.; Sun, H.; Liu, T. Study on Interference Suppression Algorithms for Electronic Noses: A Review. Sensors (Basel) 2018, 18, 1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wei, X.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, J.; You, R. Research Progress of Electronic Nose Technology in Exhaled Breath Disease Analysis. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 2023, 9, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bax, C.; Robbiani, S.; Zannin, E.; Capelli, L.; Ratti, C.; Bonetti, S.; Novelli, L.; Raimondi, F.; Di Marco, F.; Dellacà, R.L. An Experimental Apparatus for E-Nose Breath Analysis in Respiratory Failure Patients. Diagnostics (Basel) 2022, 12, 776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhanush Gowda, A.M.; Dessai, A.D.; Nayak, U.Y. Electronic-Nose Technology for Lung Cancer Detection: A Non-Invasive Diagnostic Revolution. Lung 2025, 203, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanislav, T.; Mois, G.D.; Zeadally, S.; Folea, S.; Radoni, T.C.; Al-Suhaimi, E.A. A Comprehensive Review on Sensor-Based Electronic Nose for Food Quality and Safety. Sensors (Basel) 2025, 25, 4437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Z.; Liu, Y.; Li, C.; Wang, D.; Wu, H. Electronic Noses: From Gas-Sensitive Components and Practical Applications to Data Processing. Sensors (Basel) 2024, 24, 4806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuba, A.; Kuchmenko, T.; Menzhulina, D. Drift Compensation of the Electronic Nose in the Development of Instruments for out-of-Laboratory Analysis. Chemistry Proceedings 2022, 5, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, D.; Xie, Y.; Xu, Z.; Li, J.; Liu, L.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Feng, Z. Disentangled Latent Representation Learning for Tackling the Confounding M-Bias Problem in Causal Inference. arXiv [cs.LG], 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ganin, Y.; Ustinova, E.; Ajakan, H.; Germain, P.; Larochelle, H.; Laviolette, F.; Marchand, M.; Lempitsky, V. Domain-Adversarial Training of Neural Networks. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2015, 17, 189–209. [Google Scholar]

- Bousmalis, K.; Trigeorgis, G.; Silberman, N.; Krishnan, D.; Erhan, D. Domain Separation Networks. Neural Inf Process Syst 2016, 29, 343–351. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, I.; Matthey, L.; Pal, A.; Burgess, C.P.; Glorot, X.; Botvinick, M.; Mohamed, S.; Lerchner, A. Beta-VAE: Learning Basic Visual Concepts with a Constrained Variational Framework. Int Conf Learn Represent 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Louizos, C.; Swersky, K.; Li, Y.; Welling, M.; Zemel, R. The Variational Fair Autoencoder. arXiv [stat.ML], 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Arjovsky, M.; Bottou, L.; Gulrajani, I.; Lopez-Paz, D. Invariant Risk Minimization. arXiv [stat.ML], 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Locatello, F.; Bauer, S.; Lucic, M.; Gelly, S.; Scholkopf, B.; Bachem, O. Challenging Common Assumptions in the Unsupervised Learning of Disentangled Representations. ICML 2018, 97, 4114–4124. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Chen, H.; Tang, S. ’ao; Wu, Z.; Zhu, W. Disentangled Representation Learning. arXiv [cs.LG], 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Hamaguchi, R.; Sakurada, K.; Nakamura, R. Rare Event Detection Using Disentangled Representation Learning. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); IEEE, June 2019; pp. 9327–9335. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Gonzalez, A.; Godwin, J.; Pfaff, T.; Ying, R.; Leskovec, J.; Battaglia, P. Learning to Simulate Complex Physics with Graph Networks. ICML 2020, abs/2002.09405, 8459–8468. [Google Scholar]

- Hjelm, R.D.; Fedorov, A.; Lavoie-Marchildon, S.; Grewal, K.; Bachman, P.; Trischler, A.; Bengio, Y. Learning Deep Representations by Mutual Information Estimation and Maximization. arXiv [stat.ML], 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, B.H.; Lemoine, B.; Mitchell, M. Mitigating Unwanted Biases with Adversarial Learning. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2018 AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and Society; ACM: New York, NY, USA, December 27, 2018; pp. 335–340. [Google Scholar]

- Denton, E.L.; Birodkar, V. Unsupervised Learning of Disentangled Representations from Video. Neural Inf Process Syst 2017, 30, 4414–4423. [Google Scholar]

- Villegas, R.; Yang, J.; Hong, S.; Lin, X.; Lee, H. Decomposing Motion and Content for Natural Video Sequence Prediction. arXiv [cs.CV], 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, A.; Liu, R.; Han, Y.; Zhu, L.; Yang, Y. Vector-Decomposed Disentanglement for Domain-Invariant Object Detection. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); IEEE, October 2021; pp. 9342–9351. [Google Scholar]

- Do, K.; Tran, T. Theory and Evaluation Metrics for Learning Disentangled Representations. arXiv [cs.LG], 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, H.; Wang, Y.; Li, H.; Kot, A.C.; Wen, B. Disentangled Feature Representation for Few-Shot Image Classification. arXiv [cs.CV], 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ziyatdinov, A.; Marco, S.; Chaudry, A.; Persaud, K.; Caminal, P.; Perera, A. Drift Compensation of Gas Sensor Array Data by Common Principal Component Analysis. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2010, 146, 460–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, M.; Ozdenizci, Ö.; Wang, Y.; Koike-Akino, T.; Erdoğmuş, D. Disentangled Adversarial Autoencoder for Subject-Invariant Physiological Feature Extraction. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 2020, 27, 1565–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, D.; Li, C.; Dai, W.; Liang, P.P. SMELLNET: A Large-Scale Dataset for Real-World Smell Recognition. arXiv [cs.AI], 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Ganin, Y.; Lempitsky, V. Unsupervised Domain Adaptation by Backpropagation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 32nd International Conference on Machine Learning; Vol. 37; Bach, F., Blei, D., Eds.; PMLR: Lille, France, 07--09 Jul, 2015; pp. 1180–1189. [Google Scholar]

- Levaray, N.; Ozhikandathil, J.; Masilamani, A.P.; Panarello, T. U.S. Patent No. 11,788,985. Patent 2023.

- Ryan, M.A.; Zhou, H.; Buehler, M.G.; Manatt, K.S.; Mowrey, V.S.; Jackson, S.P.; Kisor, A.K.; Shevade, A.V.; Homer, M.L. Monitoring Space Shuttle Air Quality Using the Jet Propulsion Laboratory Electronic Nose. IEEE Sens. J. 2004, 4, 337–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shevade, A.V.; Ryan, M.A.; Homer, M.L.; Manfreda, A.M.; Zhou, H.; Manatt, K.S. Molecular Modeling of Polymer Composite-Analyte Interactions in Electronic Nose Sensors. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2003, 93, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henderson, B.; Ruszkiewicz, D.M.; Wilkinson, M.; Beauchamp, J.D.; Cristescu, S.M.; Fowler, S.J.; Salman, D.; Francesco, F.D.; Koppen, G.; Langejürgen, J.; et al. A Benchmarking Protocol for Breath Analysis: The Peppermint Experiment. J. Breath Res. 2020, 14, 046008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, B.; Slingers, G.; Pedrotti, M.; Pugliese, G.; Malásková, M.; Bryant, L.; Lomonaco, T.; Ghimenti, S.; Moreno, S.; Cordell, R.; et al. The Peppermint Breath Test Benchmark for PTR-MS and SIFT-MS. J. Breath Res. 2021, 15, 046005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frazier, P.I. A Tutorial on Bayesian Optimization. arXiv [stat.ML], 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, J.C. Measuring Breath Acetone for Monitoring Fat Loss: Review. Obesity 2015, 23, 2327–2334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khemakhem, I.; Kingma, D.P.; Hyvärinen, A. Variational Autoencoders and Nonlinear ICA: A Unifying Framework. AISTATS 2019, 108, 2207–2217. [Google Scholar]

- Achille, A.; Soatto, S. Emergence of Invariance and Disentanglement in Deep Representations. Journal of Machine Learning Research 2018, 19, 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Cover, T.M.; Thomas, J.A. Elements of Information Theory: Cover/elements of Information Theory, Second Edition, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Nashville, TN, 2006; ISBN 9780471241959. [Google Scholar]

- Kingma, D.P.; Welling, M. Auto-Encoding Variational Bayes. arXiv [stat.ML], 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Tishby, N.; Pereira, F.C.; Bialek, W. The Information Bottleneck Method. arXiv [physics.data-an], 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Vapnik, V. An Overview of Statistical Learning Theory. IEEE transactions on neural networks 1999, 10, 988–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Dataset | Total Samples | Classes | Key Challenge | Source Device |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acetone Headspace | 385 | 6 levels (0-100 uL acetone) | humidity confounds acetone signal | vial-based headspace sampler |

| Ketogenic Breath | 168 | low-ketones (112); high-ketones (56) | humidity confounds acetone signals; imbalance | DiagNoze breathalyzer |

| Peppermint Breath | 361 | pre-injestion (191); post-injestion (170) | trace VOC detection amid high humidity; variability | DiagNoze breathalyzer |

| Parameter | Search Range | Baseline | CIRL |

|---|---|---|---|

| Learning Rate | [1e-4, 1e-2] | 1 x 10-3 | 3 x 10-4 |

| Batch Size | 32 | 32 | |

| λrec | [0.5, 2.0] | – | 1.0 |

| λtask | [0.5, 2.0] | – | 1.5 |

| λconf | [0.1, 0.5] | – | 0.3 |

| Component | Baseline Model | CIRL Model |

|---|---|---|

| Encoder | 3 Conv1D layers, Filters:[256, 128, 64] Kernel Size:3, Stride:2 BatchNorm+LeakyReLU(0.2) |

3 Conv1D layers, Filters:[256, 128, 64] Kernel Size:3, Stride:2 BatchNorm + LeakyReLU(0.2) |

| Latent Space | 52-dim (unified) | 32-dim ztask + 20-dim zconfounder |

| Decoder | Mirror of the encoder | |

| Task Classifier | 2 FC [256, 128] Dropout: 0.3 Input: Full Latent |

2 FC [256, 128] Dropout: 0.3 Input: ztask |

| Humidity Predictor | 2 FC [128, 256] + 1D TransposedConv Input: ztask Output: Humidity Signal |

| Dataset | MSE from ztask | MSE from zconf |

|---|---|---|

| Acetone Headspace | 0.89 ± 0.12 | 0.03 ± 0.01 |

| Ketogenic Breath | 1.23 ± 0.15 | 0.05 ± 0.02 |

| Peppermint Breath | 1.15 ± 0.18 | 0.04 ± 0.01 |

| Concentration | Baseline | CIRL | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1-Score | Precision | Recall | F1-Score | Precision | Recall | |

| C0: 0 μL (water) | 0.62 ± 0.04 | 0.65 ± 0.03 | 0.60 ± 0.05 | 0.86 ± 0.02 | 0.88 ± 0.02 | 0.84 ± 0.03 |

| C1: 5 μL | 0.55 ± 0.05 | 0.58 ± 0.04 | 0.52 ± 0.06 | 0.67 ± 0.03 | 0.69 ± 0.03 | 0.65 ± 0.04 |

| C2: 10 μL | 0.47 ± 0.06 | 0.50 ± 0.05 | 0.45 ± 0.07 | 0.63 ± 0.03 | 0.65 ± 0.03 | 0.61 ± 0.05 |

| C3: 20 μL | 0.68 ± 0.03 | 0.70 ± 0.03 | 0.66 ± 0.04 | 0.73 ± 0.02 | 0.75 ± 0.02 | 0.71 ± 0.03 |

| C4: 50 μL | 0.64 ± 0.04 | 0.66 ± 0.03 | 0.62 ± 0.05 | 0.80 ± 0.02 | 0.82 ± 0.02 | 0.78 ± 0.03 |

| C5: 100 μL | 0.58 ± 0.05 | 0.61 ± 0.04 | 0.55 ± 0.06 | 0.82 ± 0.03 | 0.84 ± 0.02 | 0.80 ± 0.03 |

| Macro Average | 0.59 ± 0.04 | 0.62 ± 0.03 | 0.57 ± 0.05 | 0.75 ± 0.03 | 0.77 ± 0.02 | 0.73 ± 0.03 |

| Dataset | Model | F1-Score | Precision | Recall | AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peppermint Pre-injestion | Baseline | 0.51 ± 0.05 | 0.54 ± 0.04 | 0.48 ± 0.06 | 0.52 ± 0.04 |

| CIRL | 0.74 ± 0.03 | 0.76 ± 0.03 | 0.72 ± 0.04 | 0.81 ± 0.02 | |

| Peppermint Post-injestion | Baseline | 0.38 ± 0.06 | 0.42 ± 0.05 | 0.35 ± 0.07 | 0.46 ± 0.05 |

| CIRL | 0.74 ± 0.03 | 0.73 ± 0.03 | 0.73 ± 0.04 | 0.82 ± 0.02 | |

| High Ketosis | Baseline | 0.42 ± 0.07 | 0.45 ± 0.06 | 0.39 ± 0.08 | 0.48 ± 0.06 |

| CIRL | 0.88 ± 0.03 | 0.89 ± 0.02 | 0.87 ± 0.03 | 0.93 ± 0.02 |

| Configuration | Acetone Headspace F1 | Ketogenic Breath F1 | Peppermint Breath F1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (single latent) | 0.59 ± 0.04 | 0.60 ± 0.06 | 0.45 ± 0.05 |

| + Reconstruction loss | 0.68 ± 0.03 | 0.75 ± 0.04 | 0.61 ± 0.04 |

| + Adversarial training (full CIRL) | 0.75 ± 0.03 | 0.91 ± 0.02 | 0.74 ± 0.03 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).