1. Introduction

Epilepsy is a chronic neurological disorder characterized by recurrent seizures associated with pathological electroencephalogram (EEG). According to ILAE (International Leaque Against Epilepsy), epilepsy can be diagnosed if at least two unprovoked (or reflex) seizures have occurred more than 24 h apart, if an unprovoked (or reflex) seizure occurs with a condition that increases the likelihood of further seizures within the next 10 years to more than 60%, or if an epilepsy syndrome is diagnosed [

1]. Affecting 0.5 to 1% of children [

2], epilepsy is one of the most common neurological disorders in childhood and one of the common reasons for attending the pediatric emergency department. A seizure is the main clinical symptom of epilepsy, but seizures may also occur due to other reasons unrelated to epilepsy, like metabolic disturbances, traumatic brain injury or infections of central nervous system.

A few diagnostic methods are involved in detailed diagnostic approach to a child with a seizure. The most common diagnostic methods are EEG, magnetic resonance of the brain as well as some other neuroimaging methods. Biochemical tests have an important role in a diagnostic approach to a patient with a seizure, mostly in excluding a range of conditions that could imitate epilepsy like some metabolic disturbances or infection of central nervous system, including meningoencephalitis. In case of seizure occurrence in febrile child, it would be more likely due to febrile convulsions or infection of central nervous system. In afebrile seizure, still there are other conditions that have to be considered.

Complete blood count (CBC) is often part of a routine diagnostic assessment in order to rule out central nervous system infection or sepsis. CBC disturbances could mislead the assessment of afebrile convulsions into a broad diagnostic evaluation. Peripheral leukocytosis after the afebrile seizure have been shown in adult population [

3,

4]. Considering that especially young children are more susceptible to infections and having less effective immune system [

5], investigation of post-convulsive leukocytosis in children is valuable in future diagnostic approach to a child with afebrile seizure.

There are few pathophysiological theories about the origin of seizure, and the leading one is neuronal theory. According to neuronal theory, seizure is the result of excessive hypersynchronous electrical activity in group of neurons, transforming normal neuronal network into a hyperexcitable one. A hyperexcitable neuronal state can result from increased excitatory or decreased inhibitory synaptic neurotransmission, an alteration in voltage-gated ion channels or an alteration of intra- or extra-cellular ion concentrations leading to membrane depolarization. The transformation of neuronal network is the basis for the epileptogenesis [

6].

Considering the importance and role of leukocytes in seizure induction, there are two possible mechanisms. A seizure can be precipitated by stress but also seizures are stress inducers, leading to increased cortisol and adrenaline blood level. Due to increased cortisol level, peripheral leukocytosis can occur. Leukocytosis is a sign of an inflammatory response as well as a sign of physical stress. High level of catecholamines can cause demargination of leukocytes, leading to redistributive and transient peripheral leukocytosis[

7,

8].

Beside the neuronal theory, there is alternative theory suggesting that inflammation in central nervous system has an important role in seizure initiation [

9]. Some studies relate leukocyte trafficking to seizure induction. Experimental studies on animal models, showed that inflammation is included in induction and development of epileptic seizures [

10]. Certain cytokines and chemokines have been found crossing blood-brain barrier or be producing inside the central nervous system. Cytokine receptors expression was increased in hippocampal neurons after seizures. Also, white blood cells have been found accumulated in the brain parenchyma of patients with epilepsy [

9,

11]. Leukocytes may contribute to seizure pathogenesis through effects on the blood brain barrier conducted by leukocyte trafficking, leukocyte adhesion and consequently vascular leakage. Therefore, circulating blood leukocytes may give the insight into overall leukocyte role in epileptogenesis.

These facts support theory that inflammation is one of possible etiological factor for seizure induction. Conclusively, post-convulsive leukocytosis can be caused by stress reaction during the seizure, following elevated cortisol and catecholamine serum level, but also regarding the role of inflammation in the development of epilepsy.

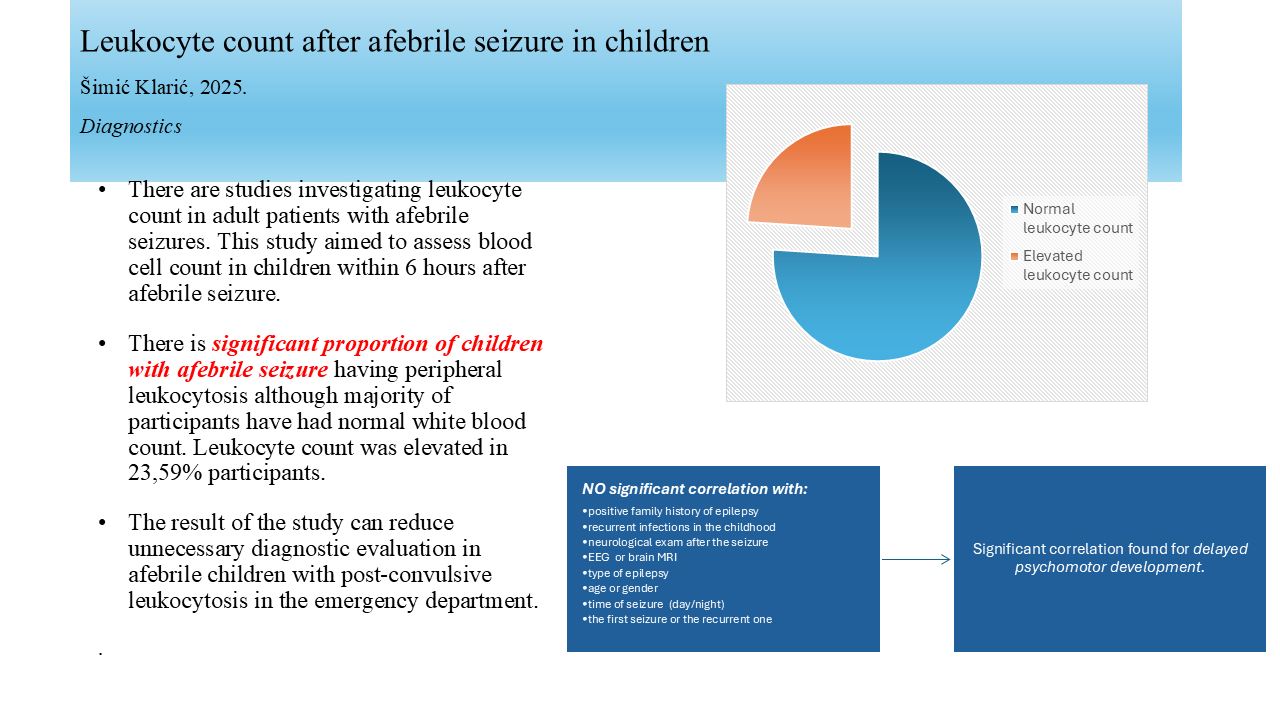

There are studies investigating leukocyte count in adult patients with afebrile seizures, but there are very few studies about CBC disturbances in children after seizure. In this study, the aim was the assessment of white blood count in children with afebrile seizures, as well as finding the relationship of elevated leukocytes to a few demographic and clinical characteristics in patients with afebrile seizure.

2. Materials and Methods

Participants in this study were 96 children admitted to the emergency department after afebrile seizure. CBC was obtained from venous blood samples within the first 6 hours after the seizure to all participants. None of them had any symptom or clinical sign of infectious disease. All children with elevated leukocyte or neutrophil count had normal C-reactive protein and sterile bacterial cultures to discard possible bacterial infection. Immuno-modulating therapy (corticosteroids, monoclonal antibodies, immunosupressants, immunostimulants) was an exclusion factor due to its effect on either suppression or stimulation of white blood cells production. Demographic, clinical and diagnostic data were collected from the medical history: age, gender, psychomotor development, family history of epilepsy, recurrent infections in the childhood, type of seizure (generalized/partial), neurological exam after the seizure, EEG (normal, focal, focal and paroxysmal, paroxysmal, slow), magnetic resonance of the brain, type of epilepsy (idiopathic/symptomatic), seizure duration, time of seizure (day/night), and the seizure appearance (the first one/recurrent). (

Table 3)

Laboratory tests were performed with hematology analyser Sysmex XN-1000 (Sysmex Corporation, Kobe, Japan) in Department of Hematology and Biochemistry in General County Hospital Požega. Age-adjusted reference values were used for distinguish normal, elevated or diminished leukocyte level [

12]. The Ethics Committee of the Hospital has the policy to waive the need for ethics approval for the collection, analysis and publication of the retrospectively obtained and anonymised data for this non-interventional study. Written informed parental consent was obtained for all participants at the emergency department.

For the statistical analysis, descriptive and inferential statistical methods were used. The median was calculated as a measure of central tendency and standard deviation as a measure of variability. Bivariate analyses were conducted to determine whether a statistical association exists between two variables. A chi-squared test with Yates continuity correction in 2x2 contingency tables was performed for categorical variables, and the independent samples t-test and Welch test were used for comparison on continuous variables. The analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS 26 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Illinois) with the level of statistical significance adjusted on p < 0.05.

3. Results

There were 96 participants with afebrile seizure, 47 girls (49%) and 49 boys (51%) with a median age of 123 months (range 10 to 216 months). Mean leukocyte value was 8,8455 (range 17,30). (

Table 1) For the benefit of statistical analysis, leukocyte levels were divided into categories: normal, elevated and diminished. (

Table 2) One participant (0,01%) had leukocyte count below normal age-specific reference range and that participant was excluded from the study. Leukocyte count was elevated in 23 (23,59%) participants. The rest of 72 (75%) participants had leukocyte count within normal age-specific reference range. The assessment of the relationship between blood leukocyte and patient’s demographic and clinical variables was performed. Statistical analysis revealed significant correlation only with psychomotor development. Children with delayed psychomotor development had more often post-convulsive leukocytosis (p 0,042). There wasn’t statistically significant correlation between elevated leukocyte count and: positive family history of epilepsy, recurrent infections in the childhood, type of seizure (generalized/partial), neurological exam after the seizure, EEG (normal, focal, focal and paroxysmal, paroxysmal, slow), magnetic resonance of the brain, type of epilepsy (idiopathic/symptomatic), age, gender, seizure duration, time of seizure (day/night), and the seizure appearance (the first one/recurrent). (

Table 4)

Table 1.

Distribution of leukocyte count.

Table 1.

Distribution of leukocyte count.

| N = 96 |

|

| Mean |

8,8455 |

| Median |

8,6800 |

| SD |

3,046331 |

| Range |

17,30 |

| Minimum |

3,60 |

| Maximum |

20,90 |

Table 2.

Distribution of leukocyte count compared to the reference range, age-adjusted.

Table 2.

Distribution of leukocyte count compared to the reference range, age-adjusted.

| Leukocyte count |

N |

% |

| |

|

|

| Normal |

73 |

75,0 |

| Elevated |

23 |

24,0 |

| Diminished |

1 |

1,0 |

| Total |

96 |

100,0 |

Table 3.

Frequency distribution of variables.

Table 3.

Frequency distribution of variables.

| |

Participants (N=96) |

| |

N (%) |

| Family history |

|

| 1 - negative |

72 (75.0) |

| 2- positive |

24 (25.0) |

| Psychomotor development |

|

| 1 – normal |

72(75.0) |

| 2 - delayed |

24 (25.0) |

| Reccurent infections |

|

| 1 – no |

82 (85.4) |

| 2 – yes |

14 (14.6) |

| Seizure type |

|

| 1 - generalized |

64 (68.8) |

| 2 - focal |

30 (31.3) |

| Neurological exam |

|

| 1 - normal |

81 (84.4) |

| 2 - abnormal |

15 (15.6) |

| EEG |

|

| 1 - normal |

16 (16.7) |

| 2 - focal |

53 (55.2) |

| 3 – focal and paroxysmal |

24 (25.0) |

| 4 - paroxysmal |

3 (3.1) |

| 5 - slow |

0 (0) |

| MR |

|

| 1 - normal |

81(84.4) |

| 2 - abnormal |

15 (15.6) |

| Idiopathic/symptomatic epilepsy |

|

| 1 – idiopathic |

82 (85.4) |

| 2 - symptomatic |

14 (14.6) |

| Time of seizure |

|

| 1 - day |

70 (72.9) |

| 2 - night |

26 (27.1) |

| Gender |

|

| 1 - female |

47 (49) |

| 2 - male |

49 (51) |

| First/recurrent seizure |

|

| 1 – first |

88 (91.7) |

| 2 – recurrent |

8 (8.3) |

Table 4.

Correlation of leukocyte level with demographic and clinical variables.

Table 4.

Correlation of leukocyte level with demographic and clinical variables.

| |

Leukocyte count (N=95) |

|

|

| |

Normal |

Elevated |

|

| |

N (%) |

N (%) |

Test, df, p |

| Family history |

|

|

|

| 1 - negative |

53 (74.6) |

18 (24.4) |

0.029, 1, 0.864a

|

| 2- positive |

19 (79.2) |

5 (20.8) |

|

| Psychomotor development |

|

|

|

| 1 – normal |

58 (81.7) |

13 (81.3) |

4.136, 1, 0.042*a

|

| 2 - delayed |

14 (58.3) |

10 (41.7) |

|

| Reccurent infections |

|

|

|

| 1 – no |

63 (76.8) |

19 (23.2) |

0.060, 1, 0.806a

|

| 2 - yes |

9 (69.2) |

4 (30.8) |

|

| Seizure |

|

|

|

| 1 - generalized |

49 (75.4) |

16 (24.6) |

0.000, 1, 1.000a

|

| 2 - focal |

23 (76.7) |

7 (23.3) |

|

| Neurological exam |

|

|

|

| 1 - normal |

64 (80.0) |

16 (20) |

3.550, 1, 0.060a

|

| 2 - abnormal |

8 (53.3) |

7 (46.7) |

|

| EEG |

|

|

|

| 1 - normal |

15 (93.8) |

1 (6.3) |

3.566, 3, 0.312b

|

| 2 - focal |

37 (71.2) |

15 (28.8) |

|

| 3 – focal and paroxysmal |

18 (75.0) |

6 (25.0) |

|

| 4 - paroxysmal |

2 (66.7) |

1 (33.3) |

|

| 5 - slow |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

|

| MR |

|

|

|

| 1 - normal |

63 (78.8) |

17 (21.3) |

1.506, 1, 0.220a

|

| 2 - abnormal |

9 (60.0) |

6 (40.0) |

|

| Idiopathic/symptomatic epilepsy |

|

|

|

| 1 – idiopathic |

63 (77.8) |

18 (22.2) |

0.563, 1, 0.453a

|

| 2 - symptomatic |

9 (64.3) |

5 (35.7) |

|

| Seizure duration |

|

|

|

| N |

72 |

23 |

-1.082, 93, .282c

|

| Arithmetic mean |

11.44 |

14.52 |

|

| SD |

11.177 |

13.892 |

|

| Time of seizure |

|

|

|

| 1 - day |

50 (72.5) |

19 (27.5) |

0.930, 1, 0.218a

|

| 2 - night |

2 (84.6) |

4 (15.4) |

|

| Age |

|

|

|

| N |

72 |

23 |

1.058, 93, 0.293c

|

| Arithmetic mean |

10.56 |

9.42 |

|

| SD |

4.6224 |

4.136 |

|

| Gender |

|

|

|

| 1 - female |

34 (73.9) |

12 (26.1) |

0.030, 1, 0.862a

|

| 2 - male |

38 (77.6) |

11 (22.4) |

|

| First/recurrent seizure |

|

|

|

| 1 – first |

66 (75.9) |

21 (24.1) |

0.000, 1, 1.000a

|

| 2 – recurrent |

6 (75.0) |

2 (25.0) |

|

4. Discussion

The aim of this study was to determine the proportion of children with afebrile seizures who had post-convulsive leukocytosis and to investigate the relationship between elevated leukocyte count with demographic and clinical characteristics - positive family history of epilepsy, recurrent infections in the childhood, type of seizure (generalized/partial), neurological exam after the seizure, EEG (normal, focal, focal and paroxysmal, paroxysmal, slow), magnetic resonance of the brain, type of epilepsy (idiopathic/symptomatic), age, gender, seizure duration, time of seizure (day/night), and the seizure appearance (the first one/recurrent).

96 children were included in the study, 47 girls (49%) and 49 boys (51%) with a median age of 123 months. We found 23,9% children aged 10 to 203 months having elevated leukocyte count within 6 hours after afebrile seizure. Other 76,1% of children after afebrile seizure have had normal white blood cell count.

In the Aydogan et al study of children with afebrile seizures, there were 41.6% patients with leukocytosis in children with status epilepticus and 8% children with afebrile seizure without status epilepticus, without significant difference according to seizure characteristics (focal or generalized seizure) [

13]. Dunn has also been noticed leukocytosis in 60% children with status epilepticus, but that study also included children with febrile status epilepticus and with meningitis as the reason for status epilepticus [

14]. Considering that our study covered only afebrile children without clinical, laboratory and microbiological signs of bacterial infection, their results are only partially comparable to ours. According to the result of Aydogan and Dunn’s studies, elevated white blood count in status epilepticus suggests that duration and intensity of the seizure play a role in immunological response. Some studies have been showed similar results in adults and adolescents with status epilepticus. Aminoff and al have been reviewed motor status epilepticus in 98 patients over the age of 14 years which partly overlaps with our population of children younger than 18 years. They have been found statistically significant amount of brisk peripheral leukocytosis in those patients [

3].

In our group of 96 participants, there were only 12 (12,5%) children that have had CBC obtained after afebrile status epilepticus. There wasn’t statistically significant correlation between seizure duration and leukocytosis but the relevance of that conclusion is limited by small number of participants in status epilepticus group.

Some former studies have found elevated white blood cells in patients with generalized and partial seizures [

15,

16]. In the study on adult patients, Sarkis and al have found significantly higher white blood cell count in patients with generalised epilepsy then in those with focal epilepsy [

4]. Potential reason for that result is higher level of circulating stress hormones – cortisol and catecholamines raising peripheral leukocyte count in patients with generalized seizure. Most of other studies investigating whether partial or generalized seizure raises peripheral leukocyte count, were performed on adults. In our study, there wasn’t statistically significant correlation according to seizure type. One of limitations of our study was relatively small number of participants. To make a relevant conclusion about the impact of seizure type on circulating post-convulsive leukocytes in children, requires more patients involved.

There wasn’t statistically significant correlation between peripheral leukocytosis after afebrile seizure and child’s age, gender, positive family history of epilepsy, recurrent infections in the childhood, neurological exam after the seizure, EEG, magnetic resonance of the brain, type of epilepsy, time of seizure or the fact if the seizure is the first one or recurrent.

Positive family history of epilepsy could be predictive for the possibility that the first seizure will continue to diagnosis of epilepsy. We can speculate that according to lack of relationship to post-convulsive leukocytosis, the main event increasing leukocytes after the seizure is the seizure itself, regardless if child’s having chronic disease like epilepsy. Also, one of the results of this study that statistical significance haven’t been found between leukocytosis and reccurent seizures is compatible with this finding.

Recurrent childhood infections were pointed as possible predictive factor for post-convulsive leukocytosis because of hyperreactivity of immune system but that connection wasn’t proved by this study. No statistical significance was found in post-convulsive leukocyte level between children with very common infections in childhood and those without. The limitation for recurrent infections was more than 12 infections per year.

Impaired neurological exam after the seizure, pathological EEG recording of structural changes on magnetic resonance of the brain could all be predictors for more complicated course of the disease, but their capability for raising leukocyte level wasn’t proved by this study.

The only variable positively correlated with leukocytosis was psychomotor development. Children with delayed psychomotor development have had more often post-convulsive leukocytosis. Some of our participants with psychomotor delay were diagnosed with cerebral palsy. Studies showed that cerebral palsy is associated with persistent inflammation, so it can be a part of the explanation for that finding [

17]. In those children, cytokines are one of the reasons for perinatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy if it was triggered by chorioamnionitis. Also, children with cerebral palsy are more susceptible to every other infection due to the respiratory and gastrointestinal disorders related to their common mobility limitations. But in this study, we had only 24 participants with psychomotor delay which is probably the small sample. It would be beneficial to repeat the study with more children with delayed psychomotor development involved.

Possible limitation of this study is that statistically, conducting the series of bivariate tests increases the chance for false positive results.

Conclusively, there is significant proportion of children with afebrile seizure having peripheral leukocytosis although majority of participants have had normal white blood count. Thus, elevated leukocyte count in children after afebrile seizure without clinical signs of bacterial infection could be due to pathophysiological background of the isolated seizure or epilepsy and doesn’t require further diagnostic evaluation. This study hasn’t found demographic or clinical variable which would clearly correlate with elevated post-convulsive leukocyte, except psychomotor delay. The possible predictivity of demographic and clinical characteristics was not clearly confirmed but the result of this study can reduce unnecessary diagnostic evaluation in afebrile children with leukocytosis after seizure in emergency department.

Author Contributions

All authors have made substantial contributions to the conception of the research, analysis, as well as the design of the article and also to the interpretation of new specific date in this research. All authors were cooperating while drafting the article and revising it critically. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The Ethics Committee of the Hospital has the policy to waive the need for ethics approval for the collection, analysis and publication of the retrospectively obtained and anonymised data for this non-interventional study.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Fisher RS, Acevedo C, Arzimanoglou A, Bogacz A, Cross JH, Elger CE, et al. ILAE official report: a practical clinical definition of epilepsy. Epilepsia 2014; 55:475–82. [CrossRef]

- Aaberg Modalsli K, Gunnes N, Bakken IJ. et al. Incidence and Prevalence of Childhood Epilepsy: Nationwide Cohort Study. Pediatrics 2017: 139(5);e20163908. [CrossRef]

- Aminoff MJ, Simon RP. Status epilepticus: causes, clinical features and consequences in 98 patients. Am J Med 1980; 69:657-666. [CrossRef]

- Sarkis RA, Jehi L, Silvier D, Janigro D, Najm I. Patients with generalised epilepsy have a higher white blood cell count than patients with focal epilepsy. Epileptic Disord 2012; 14 (1): 57-63. [CrossRef]

- Jain N. The early life education of the immune system: Moms, microbes and (missed) opportunities. Gut Microbes 2020; 12(1): 1824564. [CrossRef]

- Sumadewi KT, Harkitasari S, Tjandra DC. Biomolecular mechanisms of epileptic seizures and epilepsy: a review. Acta Epileptol 2023;15(5):28. [CrossRef]

- Simon BP. Physiologic consequences of status epilepticus. Epilepsia 1985; 26(1):558-66. [CrossRef]

- Vega JL, Komisaruk BR, Stewart M. Hiding in plain sight? A review of post-convulsive leukocyte elevations. Front Neurol 2022; 2(13): 1021042. [CrossRef]

- Fabene PF, Laudanna C, Constantin G. Leukocyte trafficking mechanisms in epilepsy. Mol Immunol 2013; 55(1):100-4. [CrossRef]

- Benini R, Roth R, Khoja Z, Avoli M, Wintermark P. Does angiogenesis play a role in the establishment of mesial temporal lobe epilepsy? Int Jour Dev Neurosc 2016; 49:31-6. [CrossRef]

- Leal B, Chaves J, Carvalho C.et al. Brain expression of inflammatory mediators in mesial temporal lobe epilepsy patients. Jour Neuroimmunol 2017; 313:82-8. [CrossRef]

- Nelson, W.E. (2024) Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 22st Edition, Elsevier, Amsterdam.

- Aydogan M, Aydogan A, Kara B, Erdogan S, Basim B, Sarper N Transient Peripheral Leukocytosis in Children With Afebrile Seizures. J Child Neurol 2007; 22:77-79. [CrossRef]

- Dunn DW. Status epilepticus in children: etiology, clinical features and outcome. J Child Neurol 1988; 3: 167-173. [CrossRef]

- Biliau AD, Wouters CH, Lagae LG. Epilepsy and the immune system: Is there a link? Eur J Pediatr Neurol 2005; 9:29-42. [CrossRef]

- Shah AK, Shien N, Fuerst D, Yangala R, Shah J, Watson C. Peripheral WBC count and serum prolactin level in various seizure types and nonepileptic events. Epilepsia 2001; 42: 1472-5. [CrossRef]

- Paton MCB, Finch- Edmonson M, Dale RC. et al. Peristent Inflammation in Cerebral Palsy: Patoghenic Mediator or Comorbidity? A Scoping Review. J Clin Med 2022; 11(24): 7368. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).