Submitted:

09 September 2025

Posted:

10 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

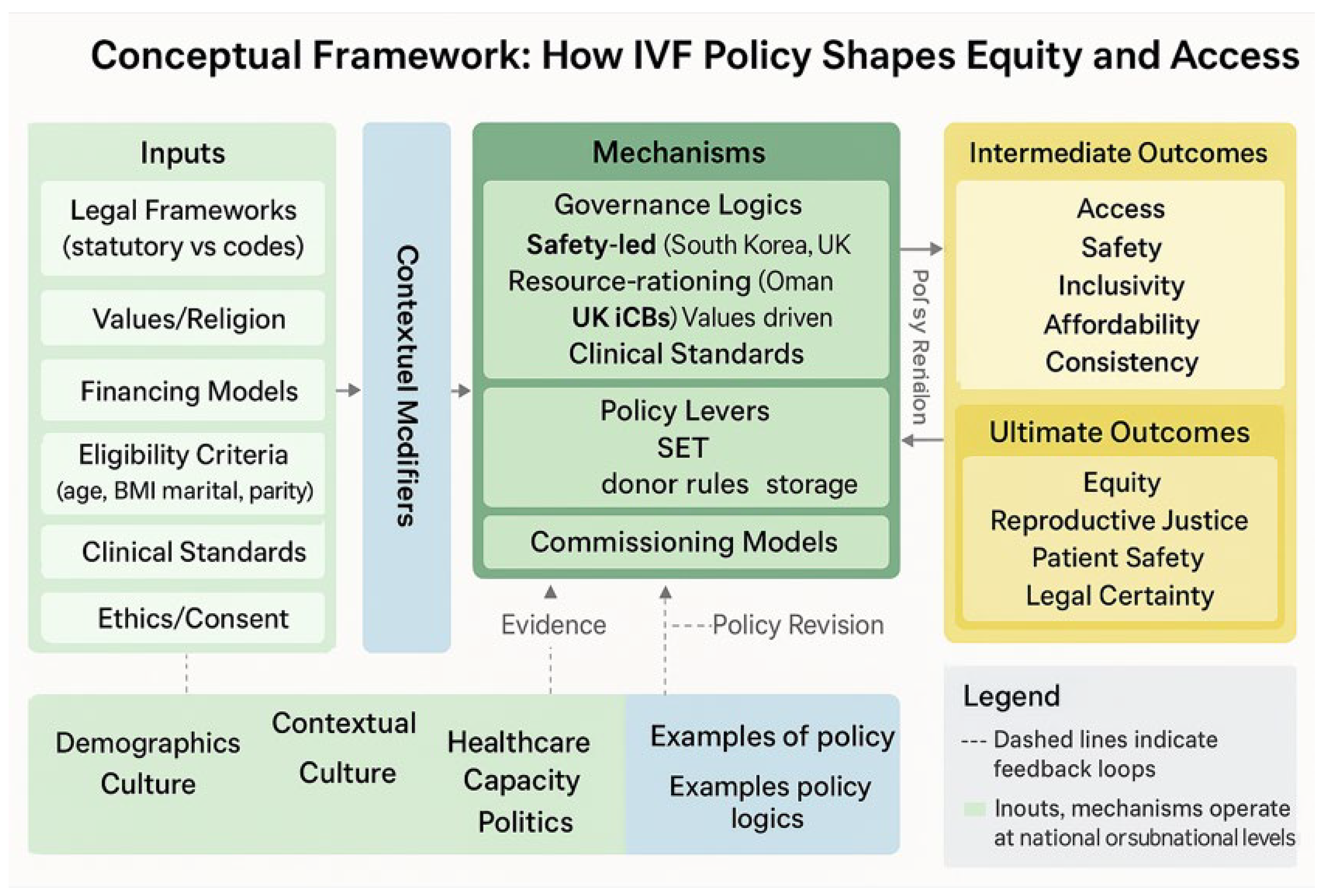

Introduction: In vitro fertilisation (IVF) has become an integral component of reproductive health, enabling millions of individuals, couples, and others to achieve intended, non-adoptive parenthood. However, governance of IVF remains highly variable, shaped by statutory law, religion, culture, and resource allocation. While some countries have developed robust statutory frameworks, others rely on interim codes or fragmented commissioning policies, creating inequities in access, safety, and inclusivity. Methods: A systematic methodology was developed in accordance with the PRISMA guidelines to examine IVF policies published across the United Kingdom (UK) and the continents of Asia, Africa, Europe, Oceania and South America. All policy documents available in a digital format from 20th of August 1990, to 2025 were included. National policies, laws, and regional commissioning frameworks explicitly addressing IVF policies were also included. Data extraction captured the statutory basis, eligibility criteria, financing models, clinical standards, and ethical provisions. A thematic, contextual and comparative analysis was conducted, complemented by descriptive statistics summarising age limits, body mass index (BMI) thresholds, inclusivity, and financing arrangements. Results: Analysis revealed wide heterogeneity in IVF policies. Marital restrictions in Iran, the Maldives, China, and Texas excluded single and LGBTQIA+ individuals, whereas South Africa, Wales, Montana, and Oregon guaranteed inclusivity. Public funding was comprehensive in South Korea and Wales but limited in Oman, Jersey, and several U.S. states. Clinical standards such as single embryo transfer were common, yet policies on gamete donation, storage, and consent varied substantially, undermining equity. Conclusion: IVF policy globally remains fragmented, reflecting divergent intersections of law, religion, and resource allocation. Statutory anchors and inclusive financing models support safety and access, yet restrictive eligibility criteria and fragmented commissioning perpetuate inequity. Regulation informed by equity and inclusivity factors, as well as integration into reproductive health strategies, is needed to ensure equitable and universal access to IVF.

Keywords:

Research in Context

| Evidence before this study Systematic comparative studies across multiple regions remain scarce, and most reviews have either limited scope to high-income countries or examined ethical and clinical concerns in isolation from financing and legal frameworks. Evidence on the intersection of eligibility criteria (age, BMI, marital status) with equity outcomes is fragmented, and few studies have quantified heterogeneity in governance models across international and subnational levels. Added value of this study This study provides the first integrated comparative analysis of IVF policy across international, subnational (UK), and U.S. state contexts, synthesising statutory frameworks, payer policies, and draft legislation. By mapping three dominant policy logics and safety-led regulation, resource-rationing frameworks, and values-driven restrictions as it demonstrates how divergent legal, religious, and fiscal priorities shape access more than clinical capacity. The inclusion of U.S. state-level evidence (e.g., Montana’s broad mandate, New Mexico’s restrictive implantation rule, and South Carolina’s explicit IVF protections) alongside international cases provides a novel cross-jurisdictional lens, showing that heterogeneity persists even within high-resource settings. Our descriptive statistics and thematic tables quantify and contextualise structural drivers of inequity, while our geographical comparison highlights how IVF policy functions as a proxy for broader reproductive politics. Implications of all the available evidence The findings show that IVF remains a technology of global inequity: enabling reproductive choice where statutory clarity, inclusive eligibility, and public financing converge, yet entrenching exclusion where rationing, religious doctrine, or fragmented governance prevail. Policymakers should prioritise harmonisation of statutory frameworks, removal of discriminatory eligibility rules, and expansion of equitable financing to align IVF with reproductive rights and demographic health strategies. International bodies such as WHO and UNFPA could play a coordinating role in setting minimum standards for safety, inclusivity, and financing, thereby reducing reliance on cross-border reproductive tourism. Embedding IVF within rights-based reproductive health policy is essential to ensure that access is determined by medical need rather than geography, income, or marital status. |

Background

Rationale

Methods

Eligibility Criteria

Information Sources

Search Strategy

Selection Process

Data Collection Process

Data Items

Risk of Bias in Individual Policies

Synthesis Methods

Results

Descriptive Analysis

Thematic and Contextual Analysis

Governance and Regulation

Eligibility and Access Criteria

Equity and Inclusivity

Clinical Standards and Safety

Financing and Coverage

Ethics, Consent, and Counselling

Comparative Analysis

Legal Comparison

Geographical Comparison of IVF Policy Frameworks

East Asia

Middle East

Europe (Including the UK)

Africa

United States

South America

Discussion

Population Implications

Clinical Implications

Geographical Implications

Recommendations

Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Availability of Data and Material

Code Availability

Ethics Approval

Consent to Participate

Consent for Publication

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Henriksson, P. Cardiovascular problems associated with IVF therapy. J. Intern. Med. 2020, 289, 2–11. [CrossRef]

- Koumparou, M.; Bakas, P.; Pantos, K.; Economou, M.; Chrousos, G. Stress management and In Vitro Fertilization (IVF): A pilot randomized controlled trial. Psychiatriki 2021, 32, 290–299. [CrossRef]

- Patrizio, P.; Albertini, D.F.; Gleicher, N.; Caplan, A. The changing world of IVF: the pros and cons of new business models offering assisted reproductive technologies. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2022, 39, 305–313. [CrossRef]

- Londra, L.; Wallach, E.; Zhao, Y. Assisted reproduction: Ethical and legal issues. Semin. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2014, 19, 264–271. [CrossRef]

- Participation E. Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act 2008 [Internet]. Statute Law Database; [cited 2025 Sept 3]. Available from: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2008/22/contents.

- Statutes of the Republic of Korea [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sept 3]. Available from: https://elaw.klri.re.kr/eng_mobile/viewer.do?hseq=33442&type=part&key=36.

- Gostin, L.; Monahan, J.T.; Kaldor, J.; DeBartolo, M.; A Friedman, E.; Gottschalk, K.; Kim, S.C.; Alwan, A.; Binagwaho, A.; Burci, G.L.; et al. The legal determinants of health: harnessing the power of law for global health and sustainable development. Lancet 2019, 393, 1857–1910. [CrossRef]

- Gama E Colombo D. Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Final report of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Rev Direito Sanit [Internet]. 2010 Feb 1 [cited 2025 Sept 3];10(3):253. Available from: http://www.revistas.usp.br/rdisan/article/view/13190.

- The Status of the Implementation of the UNGPs on Business and Human Rights in Europe and Central Asia | United Nations Development Programme [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sept 4]. Available from: https://www.undp.org/eurasia/publications/implementation-un-guiding-principles-business-and-human-rights-ecis.

- Code of Practice and Guidelines for-Medically Assisted Reproductive Techniques Family Planning Unit [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sept 3]. Available from: https://slcog.lk/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Code-of-Practice-and-Guidelines-for-Medically-Assisted-Reproductive-Techniques-Family-Planning-Unit.pdf.

- Esa G. National Standard for Assisted Reproductive technology in the Maldives.

- Croydon, S. Reluctant Rulers: Policy, Politics, and Assisted Reproduction Technology in Japan. Camb. Q. Heal. Ethic- 2022, 32, 289–299. [CrossRef]

- Issanov, A.; Aimagambetova, G.; Terzic, S.; Bapayeva, G.; Ukybassova, T.; Baikoshkarova, S.; Utepova, G.; Daribay, Z.; Bekbossinova, G.; Balykov, A.; et al. Impact of governmental support to the IVF clinical pregnancy rates: differences between public and private clinical settings in Kazakhstan—a prospective cohort study. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e049388. [CrossRef]

- Assal, A.; Chauhan, N.; Shin, E.-J.; Bowman, K.; Jones, C. Patients’ perspectives on allocation of publicly funded in vitro fertilization in Ontario: a qualitative study. CMAJ Open 2019, 7, E385–E390. [CrossRef]

- Muir, R.; Hawking, M.K.D. How do BMI-restrictive policies impact women seeking NHS-funded IVF in the United Kingdom? A qualitative analysis of online forum discussions. Reprod. Heal. 2024, 21, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Cha, W.; Yun, I.; Nam, C.-M.; Nam, J.Y.; Park, E.-C. Evaluation of Assisted Reproductive Technology Health Insurance Coverage for Multiple Pregnancies and Births in Korea. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2316696–e2316696. [CrossRef]

- Borrett A, Hughes L. More women in England opt for private IVF treatments. Financial Times [Internet]. 2024 July 30 [cited 2025 Sept 3]; Available from: https://www.ft.com/content/cffe2345-a991-46ce-a1f1-a61d4e2c8333.

- Guideline for Patient’s Eligibility Criteria for In-vitro Fertilization Treatment in Fertility Center [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sept 4]. Available from: https://moh.gov.om/en/approved-documents/khawla-hospital/guideline-for-patients-eligibility-criteria-for-in-vitro-fertilization-treatment-in-fertility-center/.

- Chan, W.; Cheang, C. Navigating the demographic shift: an examination of China's new fertility policy and its implications. Front. Politi- Sci. 2023, 5, 1278072. [CrossRef]

- Disparities in access to effective treatment for infertility in the United States: an Ethics Committee opinion (2021) [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sept 3]. Available from: https://www.asrm.org/practice-guidance/ethics-opinions/disparities-in-access-to-effective-treatment-for-infertility-in-the-united-states-an-ethics-committee-opinion-2021/.

- Hibbert, P.D.; Stewart, S.; Wiles, L.K.; Braithwaite, J.; Runciman, W.B.; Thomas, M.J.W. Improving patient safety governance and systems through learning from successes and failures: qualitative surveys and interviews with international experts. Int. J. Qual. Heal. Care 2023, 35. [CrossRef]

- Salama, M.; Isachenko, V.; Isachenko, E.; Rahimi, G.; Mallmann, P.; Westphal, L.M.; Inhorn, M.C.; Patrizio, P. Cross border reproductive care (CBRC): a growing global phenomenon with multidimensional implications (a systematic and critical review). J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2018, 35, 1277–1288. [CrossRef]

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ [Internet]. 2021 Mar 29 [cited 2025 Sept 3];372:n71. Available from: https://www.bmj.com/content/372/bmj.n71.

- Kim, M. National policies for infertility support and nursing strategies for patients affected by infertility in South Korea. Korean J. Women Heal. Nurs. 2021, 27, 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Bill tracking in South Carolina - S 40 (2025-2026 legislative session) - FastDemocracy [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sept 3]. Available from: https://fastdemocracy.com/bill-search/sc/2025-2026/bills/SCB00021994/?report-bill-view=1.

- SRP 101 Tertiary Fertility Services [Internet]. Mid and South Essex Integrated Care System. 2024 [cited 2025 Sept 3]. Available from: https://www.midandsouthessex.ics.nhs.uk/publications/101-tertiary-fertility-services/.

- Quadmani N. Updated on assisted conception in Sussex [Internet]. Sussex Health & Care. 2025 [cited 2025 Sept 3]. Available from: https://www.sussex.ics.nhs.uk/updated-on-assisted-conception-in-sussex/.

- Blue Cross Blue Shield of Rhode Island [Internet]. 2023. Medical Coverage Policy | Infertility Services. Available from: https://www.bcbsri.com/providers/sites/providers/files/policies/2024/01/2023%20Infertility%20Services.pdf.

- OSU Infertility Health Plan. Ohio State University; 2023.

- Bill Text: NH SB198 | 2023 | Regular Session | Introduced | LegiScan [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sept 3]. Available from: https://legiscan.com/NH/text/SB198/id/2660211.

- Understanding Insurance for Fertility Treatment Costs [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sept 3]. Available from: https://fertility.womenandinfants.org/patients/insurance-fertility-treatment-costs.

- Department of Financial Services [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sept 3]. Health Insurers FAQs: IVF and Fertility Preservation Law Q&A Guidance. Available from: https://www.dfs.ny.gov/apps_and_licensing/health_insurers/ivf_fertility_preservation_law_qa_guidance.

- Abbasi, M.J.; Mehryar, A.; Jones, G.; McDonald, P. Revolution, war and modernization: Population policy and fertility change in Iran. J. Popul. Res. 2002, 19, 25–46. [CrossRef]

- Reilly C. Constitutional Limits on New Mexico’s In Vitro Fertilization Law. New Mexico Law Review [Internet]. 1994 Jan 1;24(1):125. Available from: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmlr/vol24/iss1/8.

- LegiScan [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sept 3]. Texas HB618 | 2025-2026 | 89th Legislature. Available from: https://legiscan.com/TX/text/HB618/id/3028055.

- Gorkom F van. Infertility in South Africa: A Neglected Issue in Need of a Public Health Response. An exploration of Causes, Consequences, and Interventions. 2021 [cited 2025 Sept 4]; Available from: https://www.bibalex.org/baifa/en/resources/document/476726.

- whssc.nhs.wales/commissioning/nwjcc-policies/fertility/specialist-fertility-services-commissioning-policy-cp38-april-2025/ [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sept 3]. Available from: https://whssc.nhs.wales/commissioning/nwjcc-policies/fertility/specialist-fertility-services-commissioning-policy-cp38-april-2025/.

- LegiScan [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sept 3]. Montana HB565 | 2025 | Regular Session. Available from: https://legiscan.com/MT/bill/HB565/2025.

- Copy of Fairness for All: 7 Tips for Creating a Parenting Plan That Benefits You, Your Ex, and Your Children [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sept 3]. Available from: https://www.pacificcascadelegal.com/documents/Expanding-Your-Family-A-Guide-to-Surrogacy-and-IVF-Options.pdf.

- States Assembly [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sept 4]. States Assembly - P.20/2024. Available from: https://statesassembly.je/publications/propositions/2024/p-20-2024.

- Lacewell LA. Report on In-Vitro Fertilization and Fertilization Preservation Coverage.

- Informed Consent for Medications F-24277 Series: Psychotropic Medications | Wisconsin Department of Health Services [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sept 3]. Available from: https://www.dhs.wisconsin.gov/forms/medbrandname.htm.

- LegiScan [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sept 3]. South Carolina S0040 | 2025-2026 | 126th General Assembly. Available from: https://legiscan.com/SC/research/S0040/2025.

- Justia Law [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sept 3]. Davis v. Davis. Available from: https://law.justia.com/cases/wisconsin/supreme-court/1951/259-wis-1-3.html.

- nhs.uk [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2025 Sept 3]. IVF. Available from: https://www.nhs.uk/tests-and-treatments/ivf/.

- Mandated benefit review of infertility treatment [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sept 3]. Available from: https://doh.wa.gov/sites/default/files/2025-02/120-055-MandatedBenefitReviewInfertilityTreatment.pdf.

- Human Fertilisation & Embryology Authority (HFEA) [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sept 3]. HFEA: UK fertility regulator. Available from: https://www.hfea.gov.uk/.

- Guidelines, Standards & Policies Portal [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sept 3]. Available from: http://guidelines.health.go.ke/#/category/18/347/meta.

- Machin, R.; Mendosa, D.; Augusto, M.H.O.; Monteleone, P.A.A. Assisted Reproductive Technologies in Brazil: characterization of centers and profiles from patients treated. Jbra Assist. Reprod. 2020, 24, 235–240. [CrossRef]

- Haddadi, M.; Hedayati, F.; Hantoushzadeh, S. Parallel paths: abortion access restrictions in the USA and Iran. Contracept. Reprod. Med. 2025, 10, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Haddadi, M.; Hantoushzadeh, S.; Hajari, P.; Pouraie, R.R.; Hadiani, M.Y.; Habibi, G.R.; Eshraghi, N.; Ghaemi, M. Challenges and Prospects for Surrogacy in Iran as a Pioneer Islamic Country in this Field. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2025, 28, 252–254. [CrossRef]

- Haddadi, M.; Sahebi, L.; Hedayati, F.; Shah, I.H.; Parsaei, M.; Shariat, M.; Dashtkoohi, M.; Hantoushzadeh, S.; Cheraghi, Z. Induced abortion in Iran, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, the law and the diverging attitude of medical and health science students. PLOS ONE 2025, 20, e0320302. [CrossRef]

| Domain | Metric | Number/Result |

| Scope of analysis | Total jurisdictions/policies analysed | 20 (13 international + 7 US |

| Legal frameworks | With statutory IVF/ART law | 13 (8 international, 5 US) |

| With code/interim only | 3 (Sri Lanka, Kenya, Wisconsin) | |

| Eligibility (Age) | Median maximum age for IVF access | 42 years |

| Range of maximum age limits | 25–45 years (RI 25–42; OSU <43; Iran 45) | |

| Eligibility (BMI) | Jurisdictions/payers with explicit BMI restrictions | 11 (8 international + 3 USA) |

| Access rules | Jurisdictions requiring marriage for access | 3 (Maldives, Iran, Texas HB618) |

| Explicitly inclusive jurisdictions (single and LGBTQIA+ ) | 5 (South Africa, Wales, Montana HB565, Oregon, Washington draft mandate) | |

| Financing | Jurisdictions with public funding/insurance mandates | 9 (6 international + 3 US) |

| Caps/limits | Jurisdictions with cycle/dollar caps | 7 (UK ICBs, NY DFS, WA draft, BCBSRI, OSU, Montana, NH) |

| Theme | Sub-theme | Example Indicator | Exposure | Determinants | Intersections | Relevant Law/Instrument | Policy Strength | Policy Weakness |

| Governance & Licensing | Oversight & reporting | Sri Lanka registration; WA cost study review; SC SB-40 IVF protections | Clinics, patients | Regulatory maturity | Medico-legal risk, personhood debates | Sri Lanka PHSRC; SC SB-40; NY DFS Actuarial Review | Safety clarity; legal protection | Fragmentation; patchwork coverage |

| Facility & Standards | Infrastructure, counselling | Jersey off-island IVF; US payer PA requirements | IVF patients | Accreditation; actuarial cost | Geography; affordability | Jersey P.20/2024; OSU policy | Strong clinical oversight | Travel burdens; admin delays |

| Eligibility | Age/BMI thresholds | Oman ≤42 yrs., BMI <35; OSU <43; RI 25–42 | Women seeking IVF | Ageing, obesity, actuarial limits | SES, delayed childbearing | Oman guideline; OSU/BCBSRI policies | Transparent, safety-aligned | Exclusionary; autonomy limits |

| Eligibility | Marital/lineage rules | Maldives married only; TX HB618 spouse’s sperm; Iran marital mandate | Unmarried, LGBTQIA+ | Religion; heteronormative law | Equality; reproductive justice | Maldives ART Std; TX HB618 | Cultural alignment | Excludes singles/LGBTQIA+ |

| Equity | Inclusion of singles/LGBTQIA+ | Wales CP38; Montana HB565; WA draft | LGBTQIA+, single, trans | Equality law, insurance parity | Cross-border care; affordability | WA draft mandate; Montana HB565 | Inclusive access; anti-discrimination | Premium/fiscal constraints |

| Financing | Public funding/insurance | Korea insurance; Jersey NICE alignment; NY 0.5–1.1% premium; MT $40k floor | Couples needing ART | National financing; actuarial limits | Income, geography | Korea Act; Jersey P.20/2024; NY DFS; MT HB565 | Financial protection; coverage floor | OOP co-pays; fiscal pressure |

| Clinical Standards | Embryo transfer & SET | UK ICBs; WA draft SET | IVF patients | Safety; multiples risk | Maternal health | HFEA; WA draft | Safer births | Perceived restriction |

| Donor Gametes | Coverage/screening | OSU covers donors for male factor; RI six inseminations before IVF | Donors, LGBTQIA+ couples | Clinical criteria; cost limits | Sexual orientation equity | OSU policy; RI §27-20-20 | Some donor coverage | Restrictive, inequitable |

| Embryo Storage | Duration & disposal | Sri Lanka 10 yrs.; OSU 90 days; BCBSRI excludes storage | Patients with gametes | Law, payer policy | Bereavement; autonomy | HFEA; OSU; BCBSRI | Clarity in disposal | Inflexibility, inequity |

| Consent & Ethics | Embryo disposition rules | NM implant-all; WI contracts; Maldives spousal consent | Couples, clinics | Religion; contract law | Privacy vs jurisprudence | NM IVF statute; WI case law | Legal certainty (SC SB-40) | Chilling effects; inequity |

| Region | Policy Logic Dominant | Eligibility Rules | Financing Model | Equity & Inclusion | Governance Strength |

| Asia (South Korea, Japan, China, Oman, Iran, Maldives) | Safety-led (Korea, Japan), rationing (Oman, values-driven (Iran, Maldives, China) | Age cut-offs (≤42–45), BMI thresholds (Oman), marital restrictions (Iran, Maldives, China) | Korea: universal insurance; Japan: partial subsidies; Oman: rationed public; Iran/Maldives: limited, private reliance | Exclusion of singles/LGBTQ+ (Iran, Maldives, China); Korea reduces inequity | Korea/Japan strong statutory; Iran/Maldives religious statutes; Oman ministerial |

| Europe (UK, Jersey) | Rationing (UK ICBs); rights-based shift (Wales, Jersey proposal) | UK: age 38–43; BMI 19–30; childlessness rules; Jersey: NICE-alignment pending | NHS-funded cycles (0–2); Jersey: meds-only → proposed 3 NICE cycles | Wales inclusive of singles/LGBTQIA+; England fragmented | UK strong statutory safety; commissioning fragmented |

| Africa (South Africa, Kenya) | Rights-based (SA); interim/discretionary (Kenya) | SA: broad inclusivity; Kenya: case-by-case | Public hospitals with inequitable reach; private markets | SA explicit rights protections; Kenya inequity | SA statutory guideline; Kenya draft only |

| North America (USA) | Mixed: inclusive mandates (Montana, Oregon, Washington); restrictive (Texas, NM); actuarial balance (NY, NH); patchwork payers (RI, OSU, WI) | Montana broad; WA inclusive; RI/OSU age & BMI caps; TX spouse sperm; NM implant-all | Montana $40k floor; NY/NH premium-limited; RI/OSU benefit caps; federal VA/TRICARE exclusions | Inclusivity (MT, OR, WA); Exclusion (TX, NM, payer caps); affordability gaps persist | Statutory protections (SC SB-40, MT HB565); gaps (WI contract reliance) |

| South America (Brazil etc.) | Partial safety-led, uneven | Age-based, variable | Limited public funding, private reliance | Socio-economic inequities pronounced | Emerging statutory frameworks |

| Domain | Recommendation | Evidence/Justification |

| Legal frameworks | Introduce or strengthen statutory regulation of IVF, including licensing, safety standards, donor regulation, and parentage rules. | Jurisdictions with statutory anchors (UK HFE Acts, South Korea’s Bioethics Act, SC SB-40) demonstrate greater clinical safety and legal certainty compared with code- or contract-based systems (Sri Lanka, Kenya, Wisconsin). |

| Equity of access | Remove exclusionary criteria based on marital status, sexual orientation, or parity, and harmonise eligibility thresholds such as age and BMI. | Maldives, Iran, China, and Texas restrict IVF to married heterosexual couples; UK ICBs and U.S. payers impose variable age/BMI cut-offs. Wales, South Africa, Montana, and Oregon show inclusive models are feasible. |

| Financing | Expand public funding or insurance mandates to reduce reliance on private markets and self-funding prerequisites. | South Korea’s insurance model improved access; Wales funds two cycles; Montana sets a $40k floor. By contrast, Jersey’s means test, Oman’s rationing, and New York’s actuarial caps highlight inequities. |

| Clinical standards | Mandate evidence-based practices such as single embryo transfer, clear embryo storage rules, and donor gamete registries with transparency on identity rights. | UK and Sri Lanka reduce multiple births via SET; Washington embeds SET; Maldives applies rigid cessation triggers; Japan and U.S. payers leave donor identity unresolved. |

| Integration | Align IVF policy with broader reproductive health and demographic strategies, and promote international cooperation on minimum standards. | Pronatalist aims in China conflict with IVF exclusion; U.S. patchwork fosters cross-border care; WHO/UNFPA call for harmonisation to mitigate reproductive tourism. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).