Submitted:

06 September 2025

Posted:

08 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

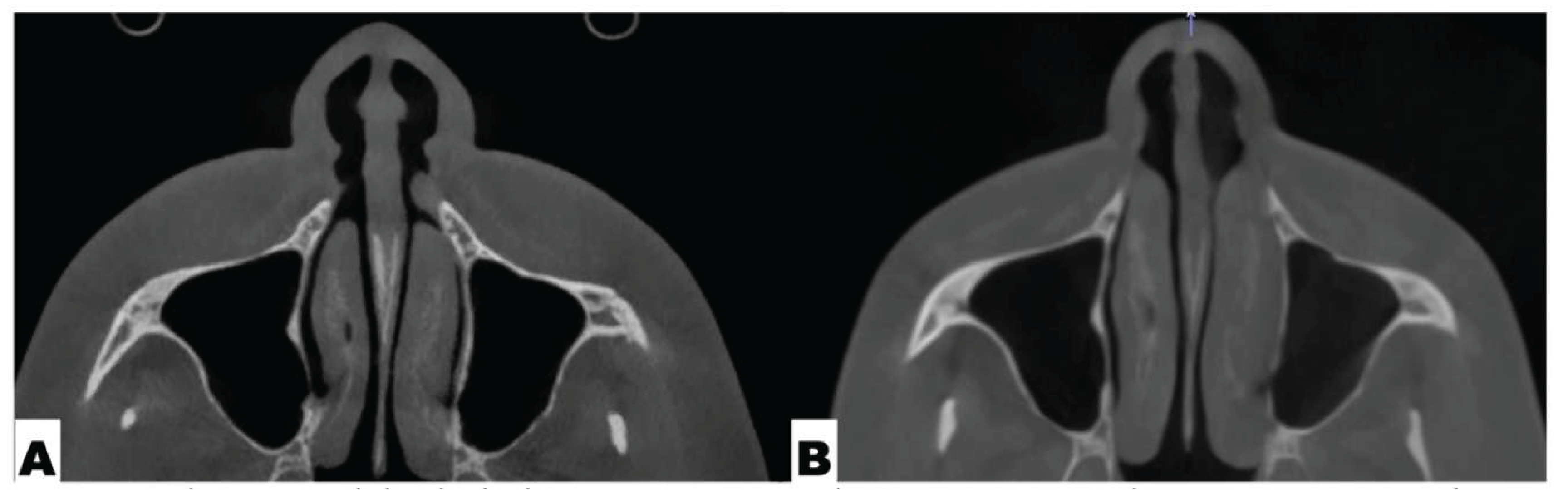

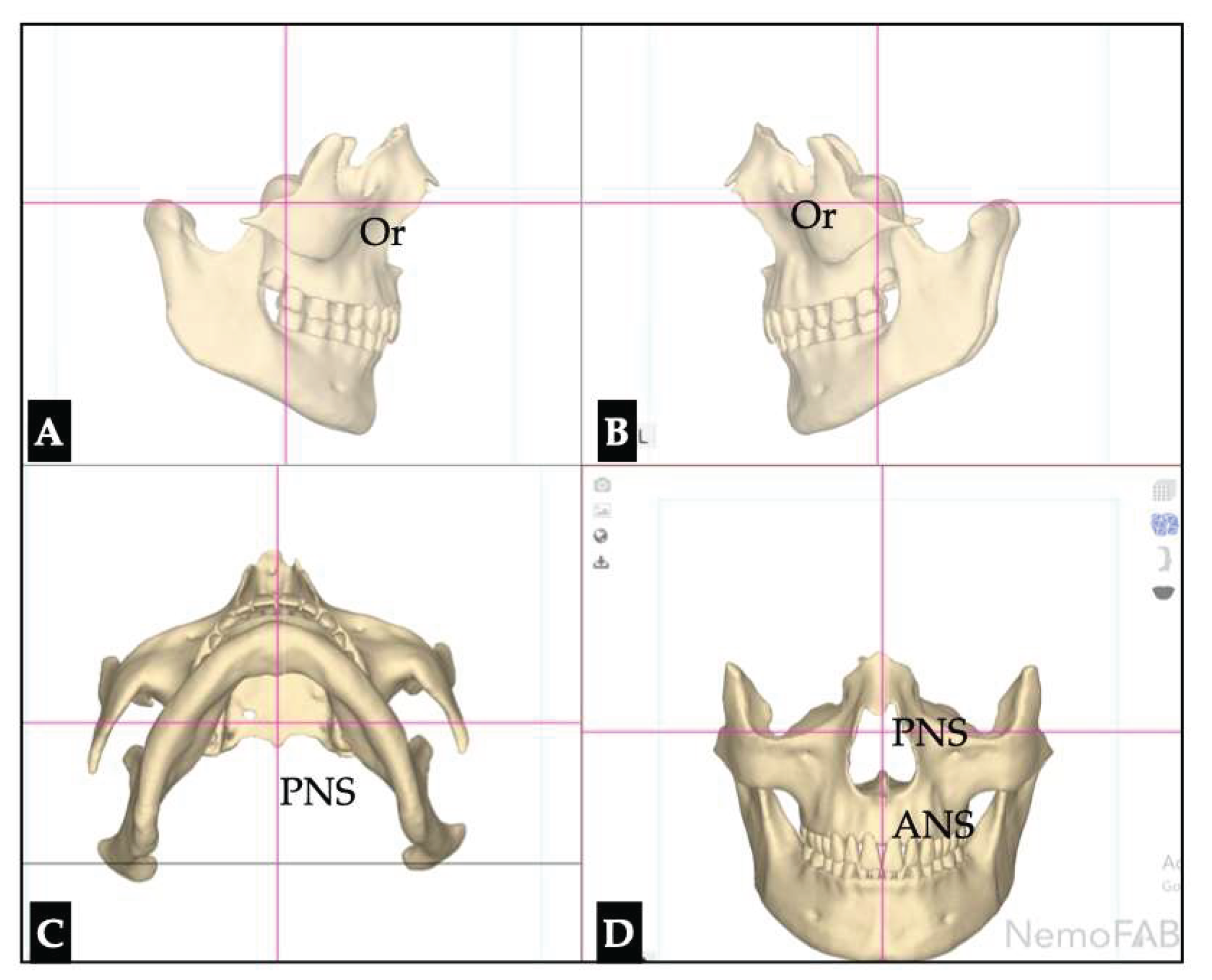

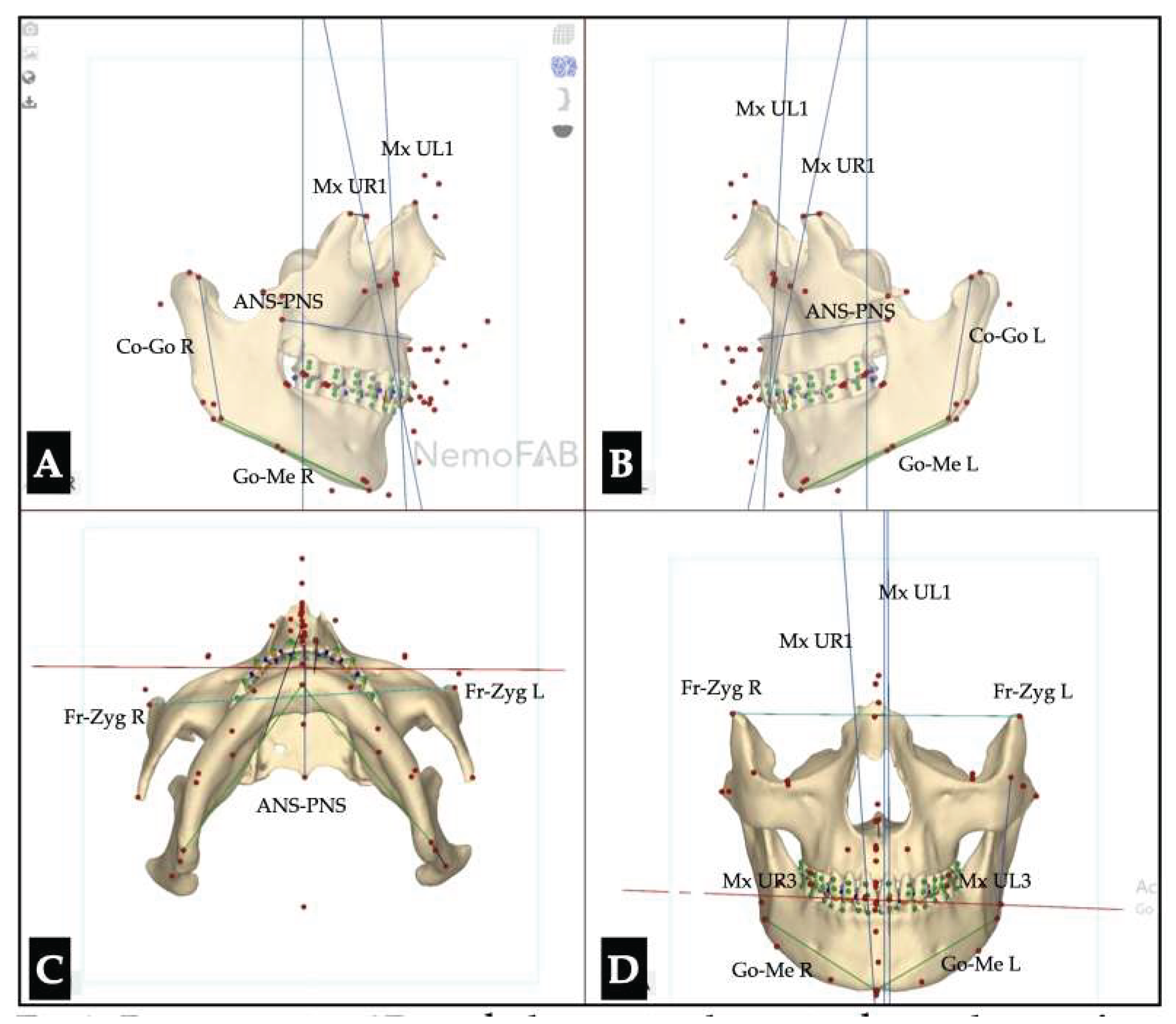

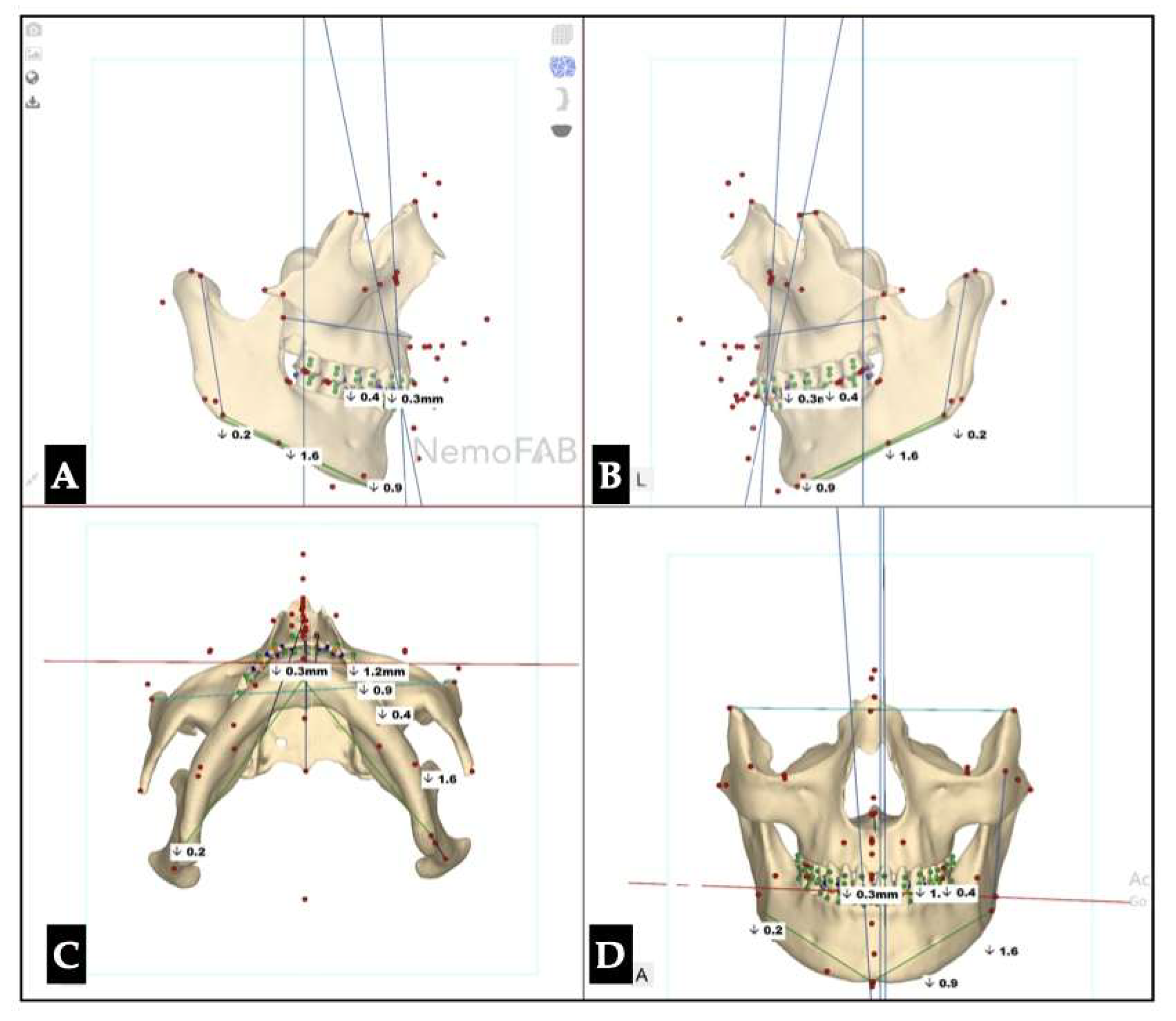

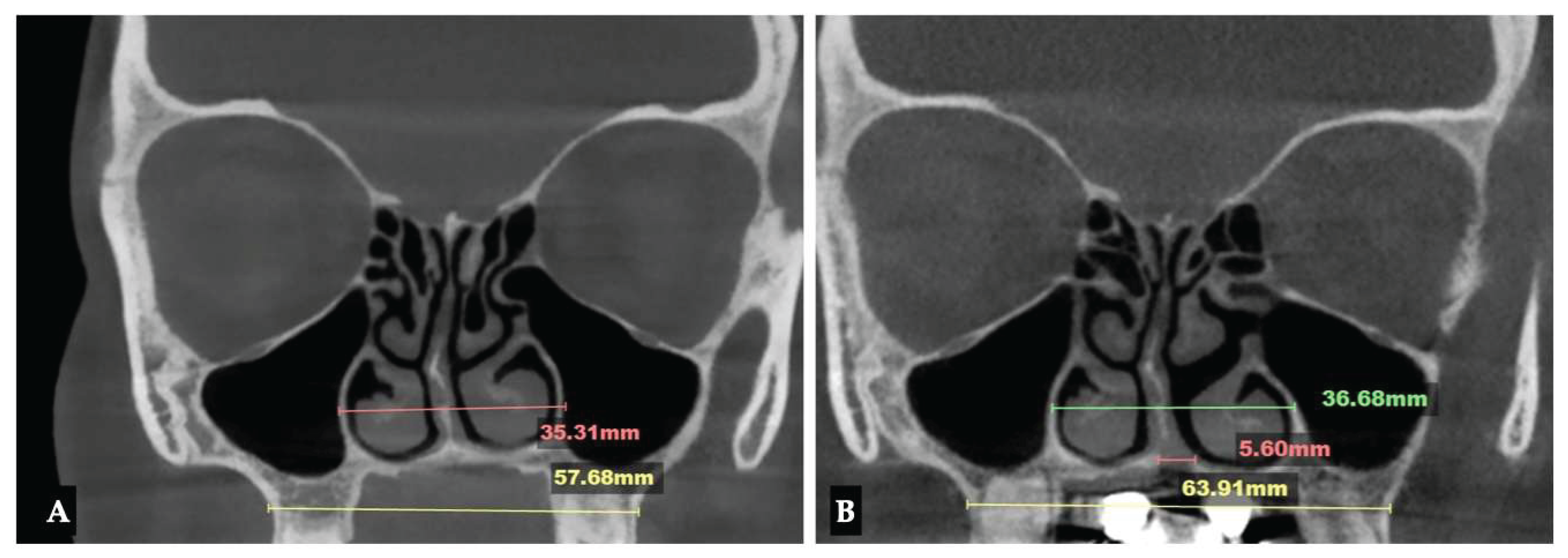

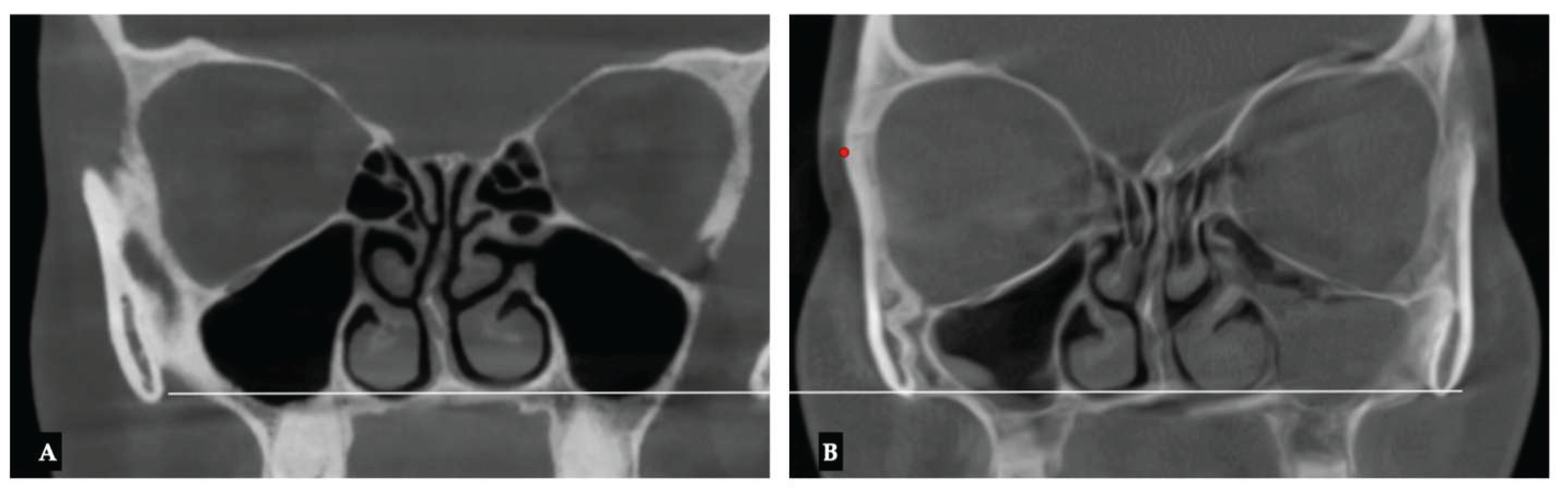

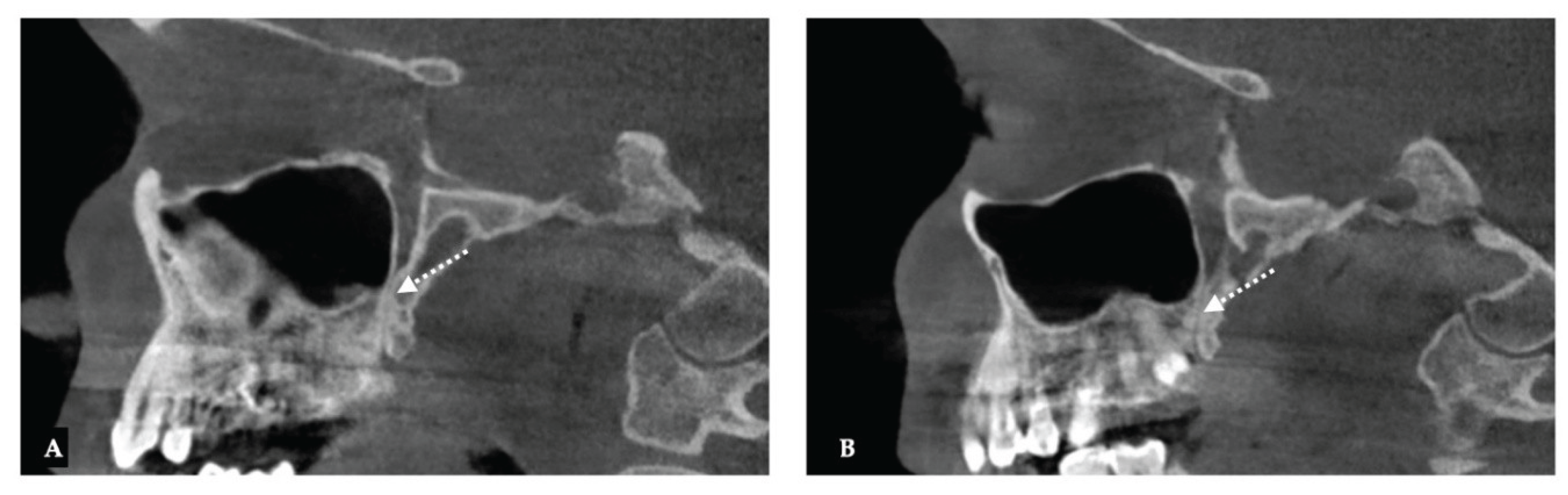

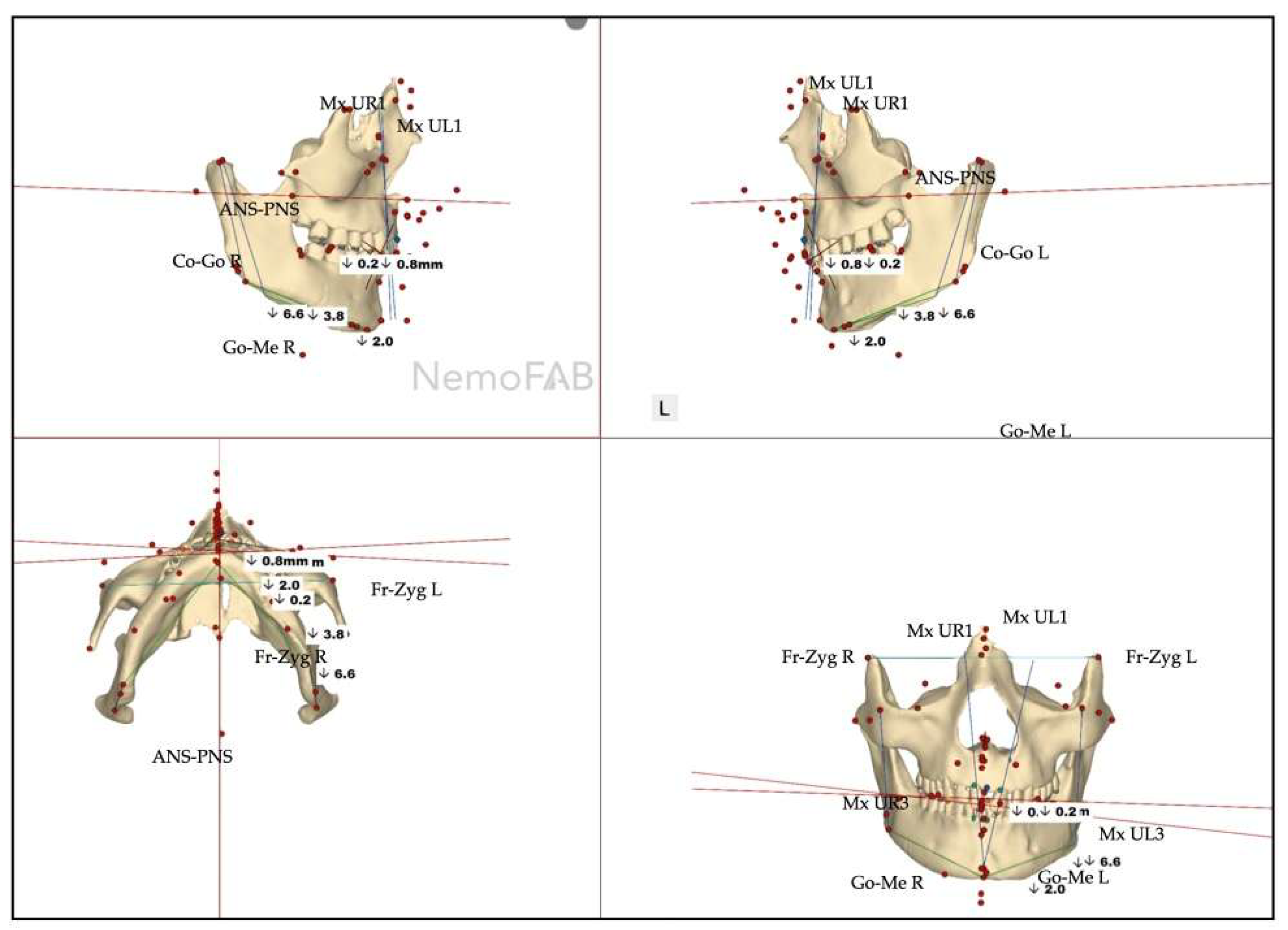

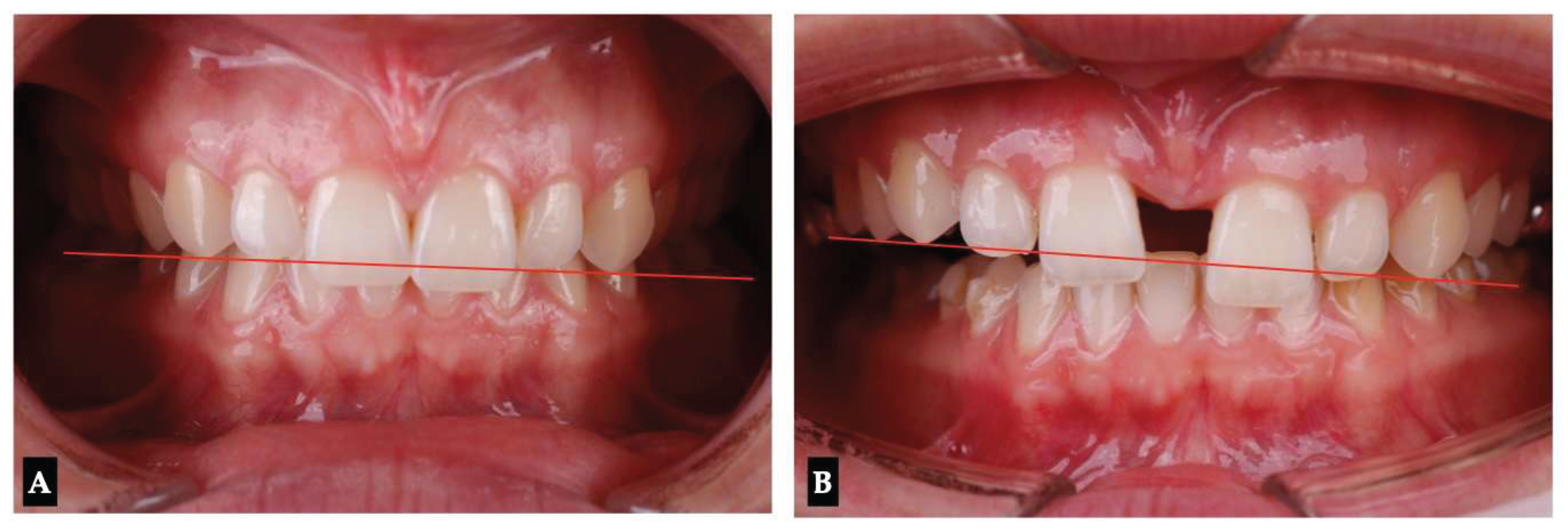

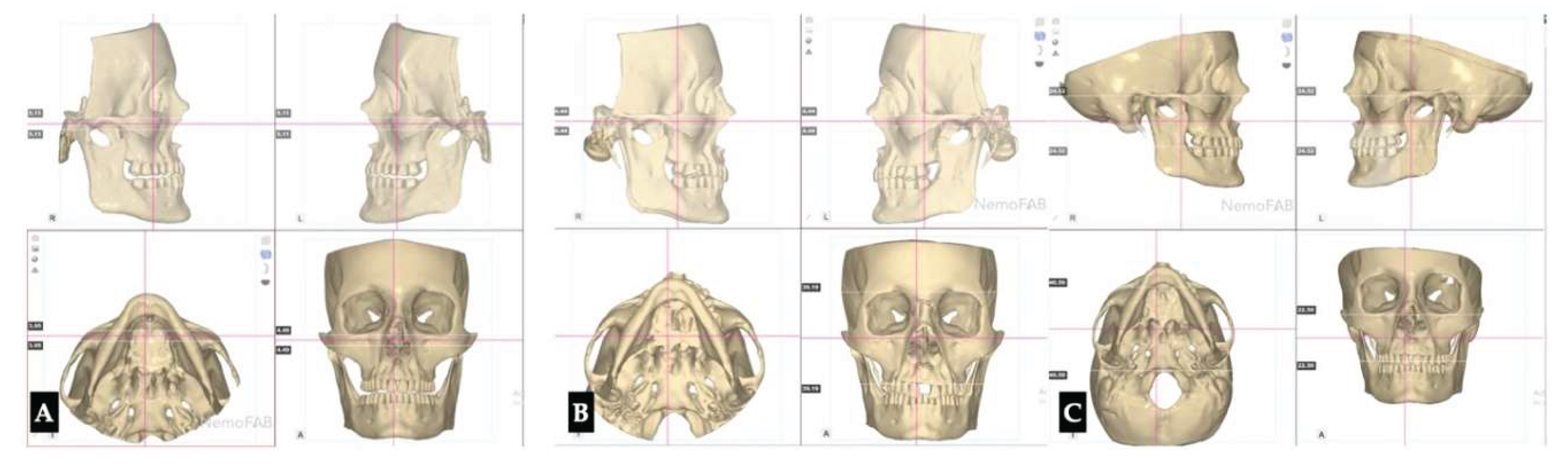

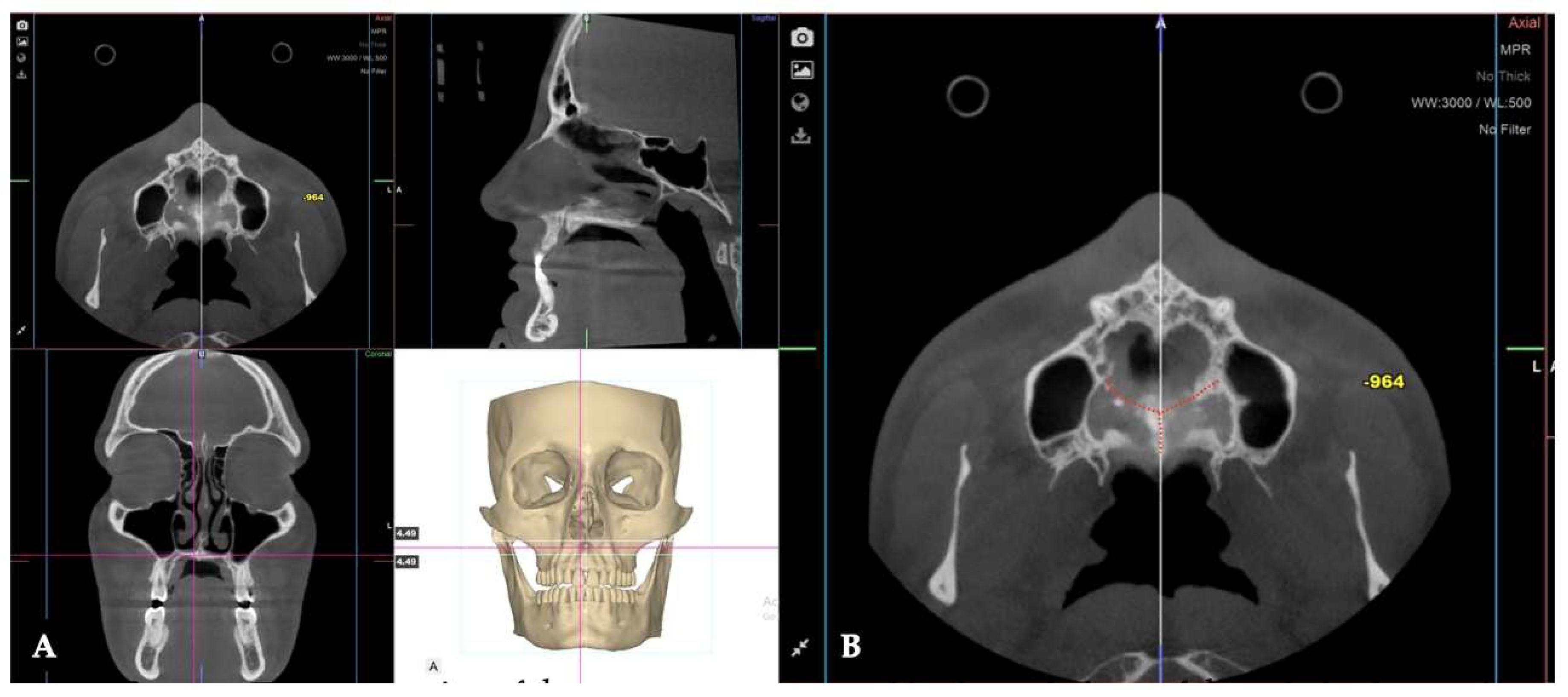

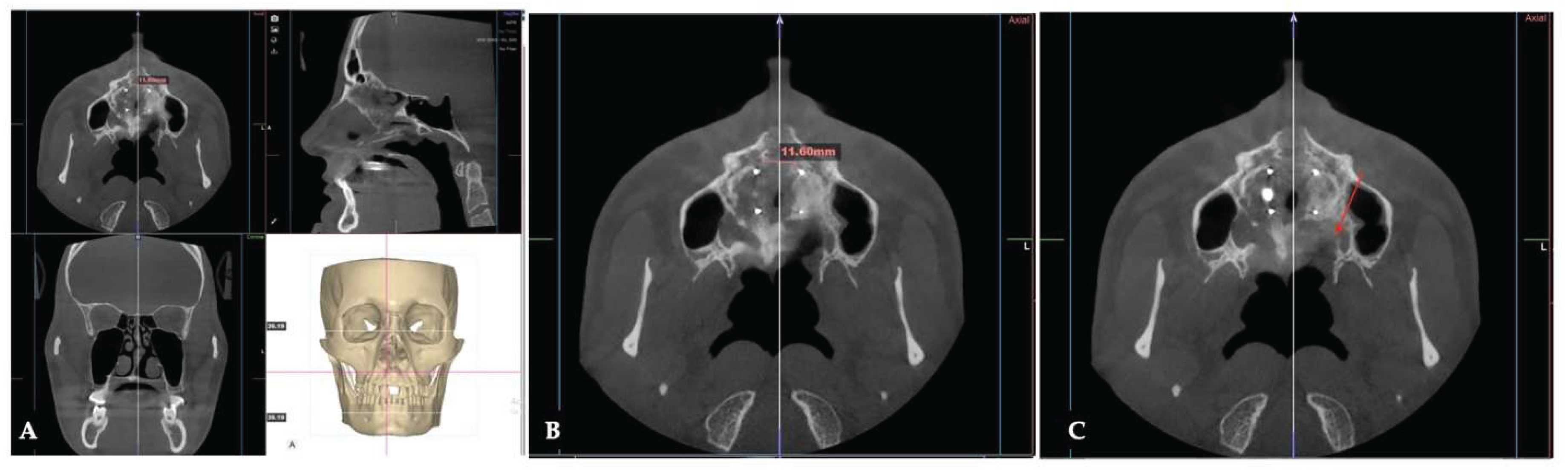

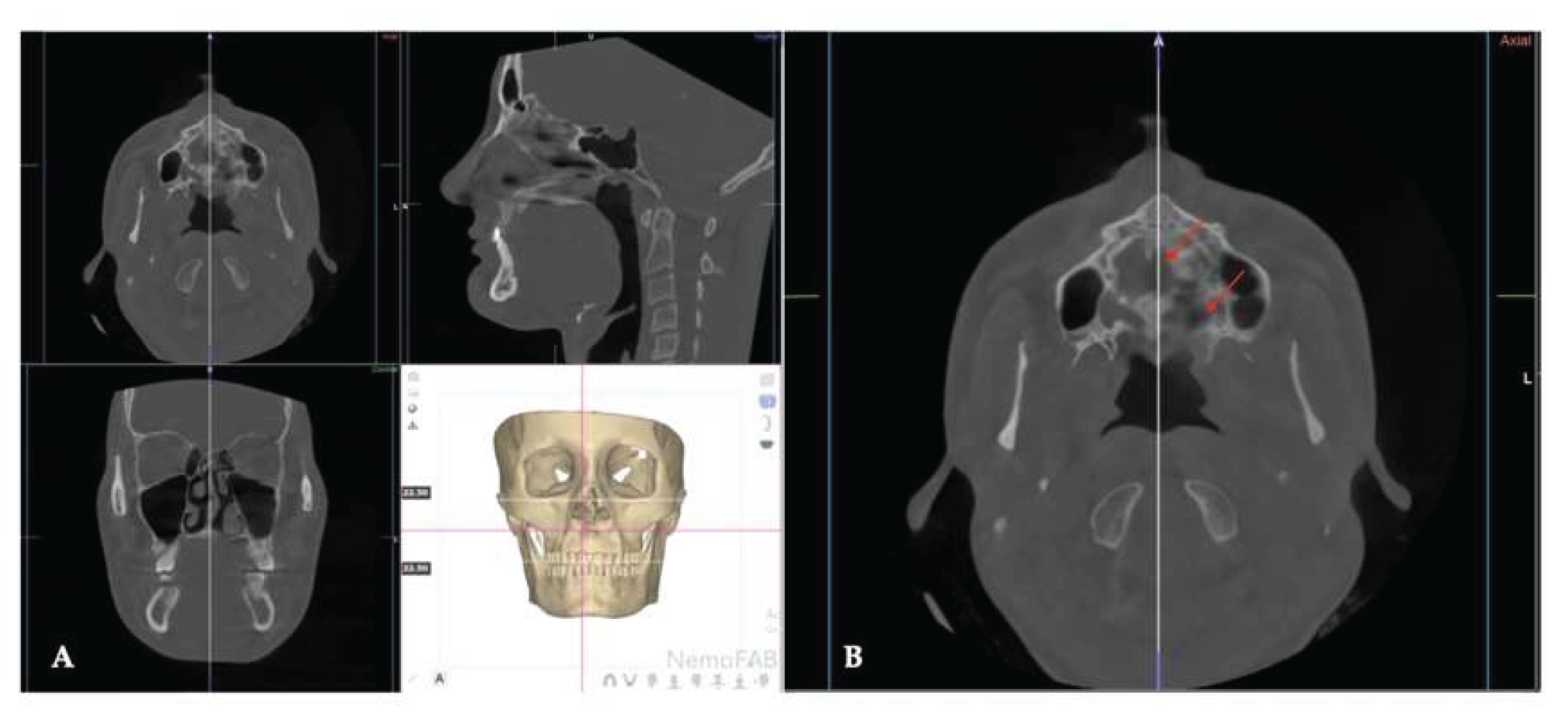

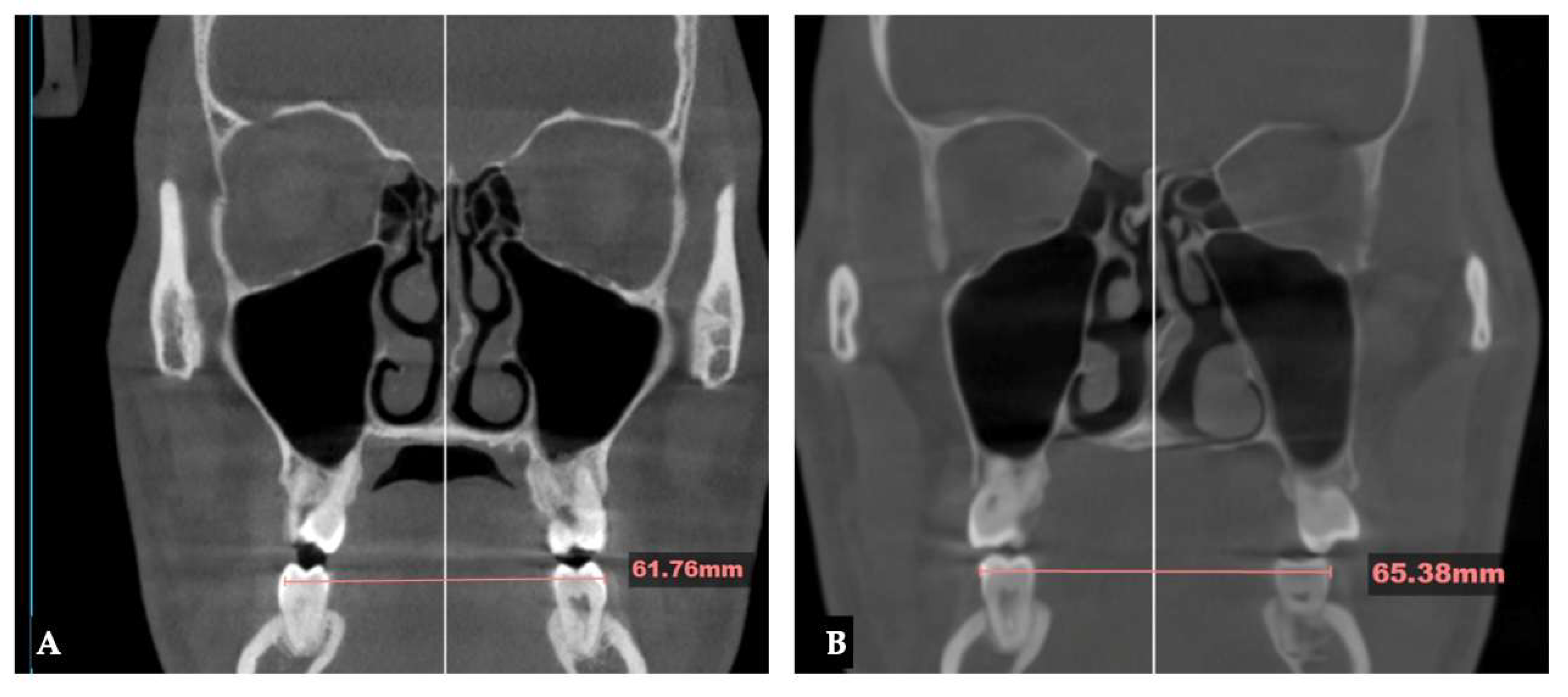

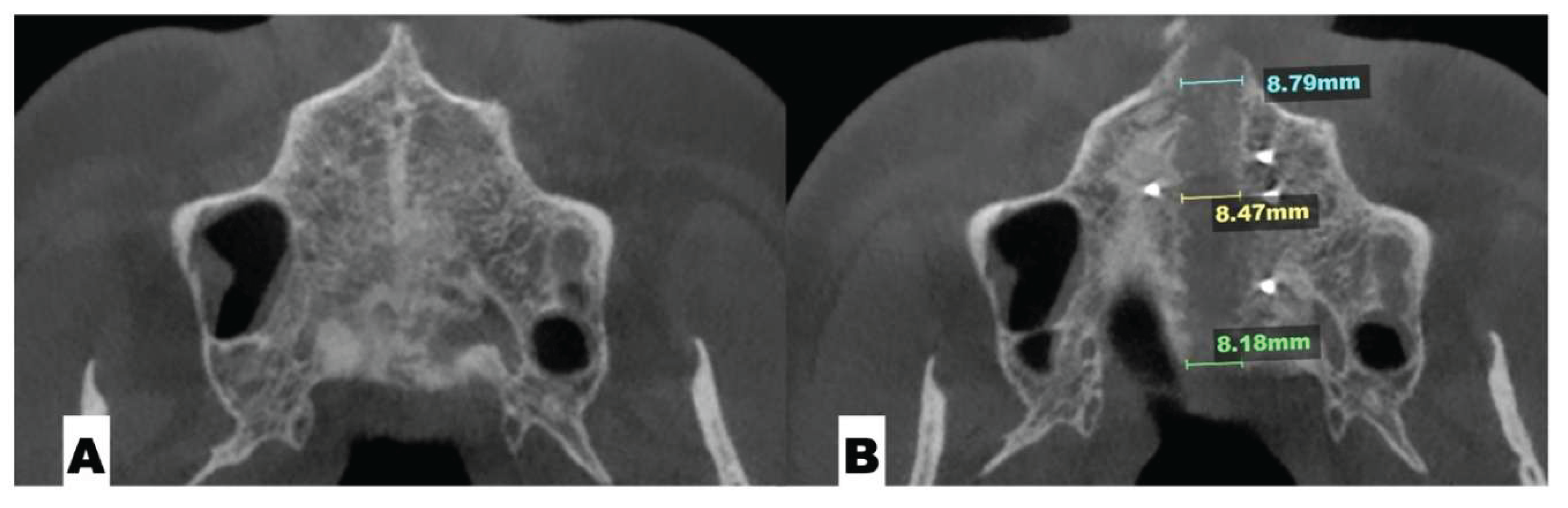

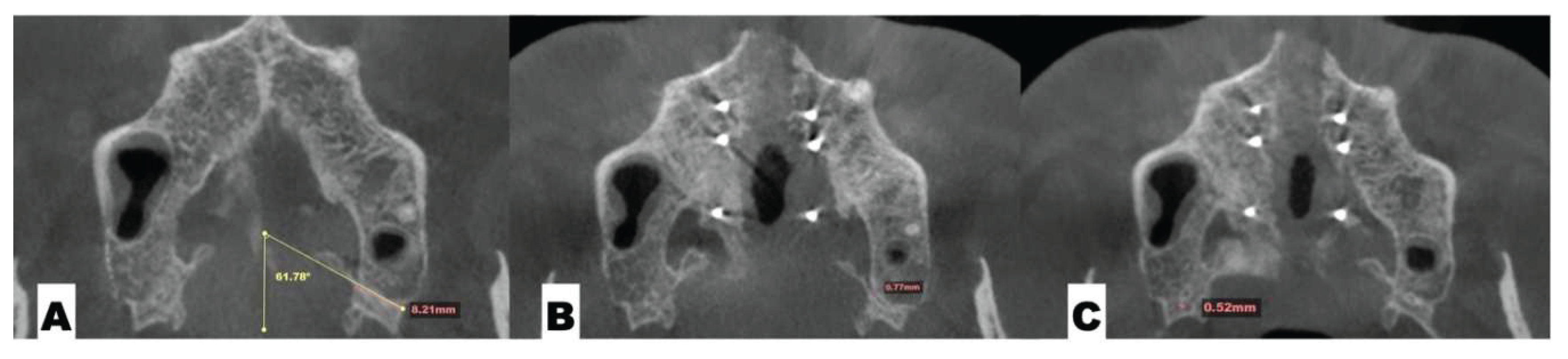

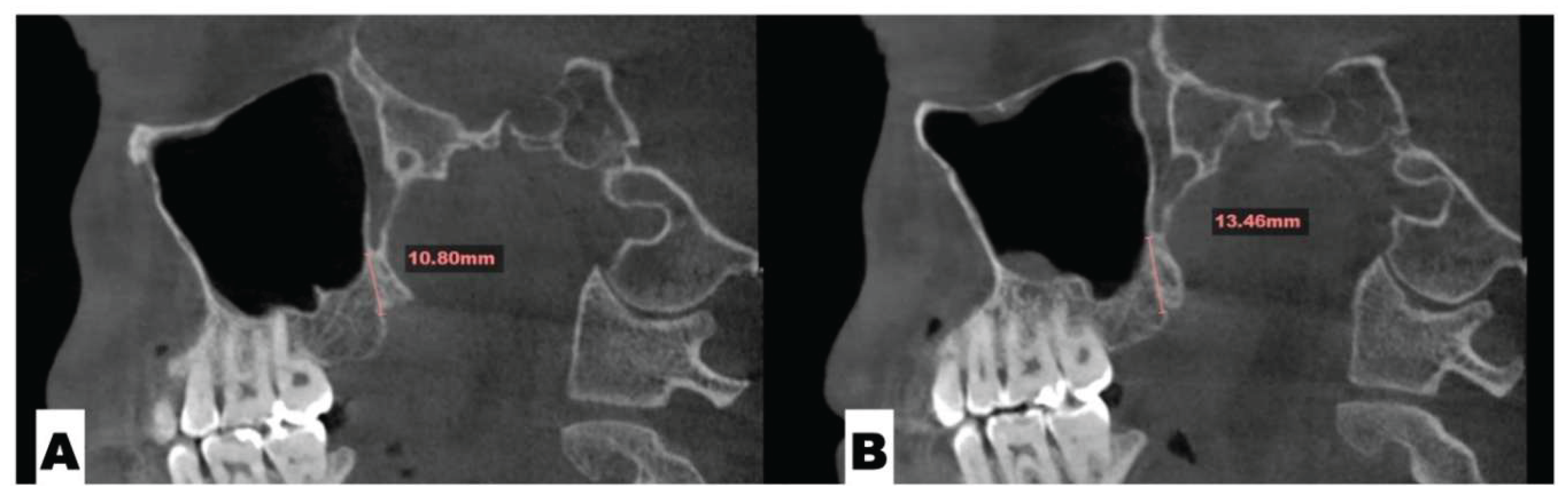

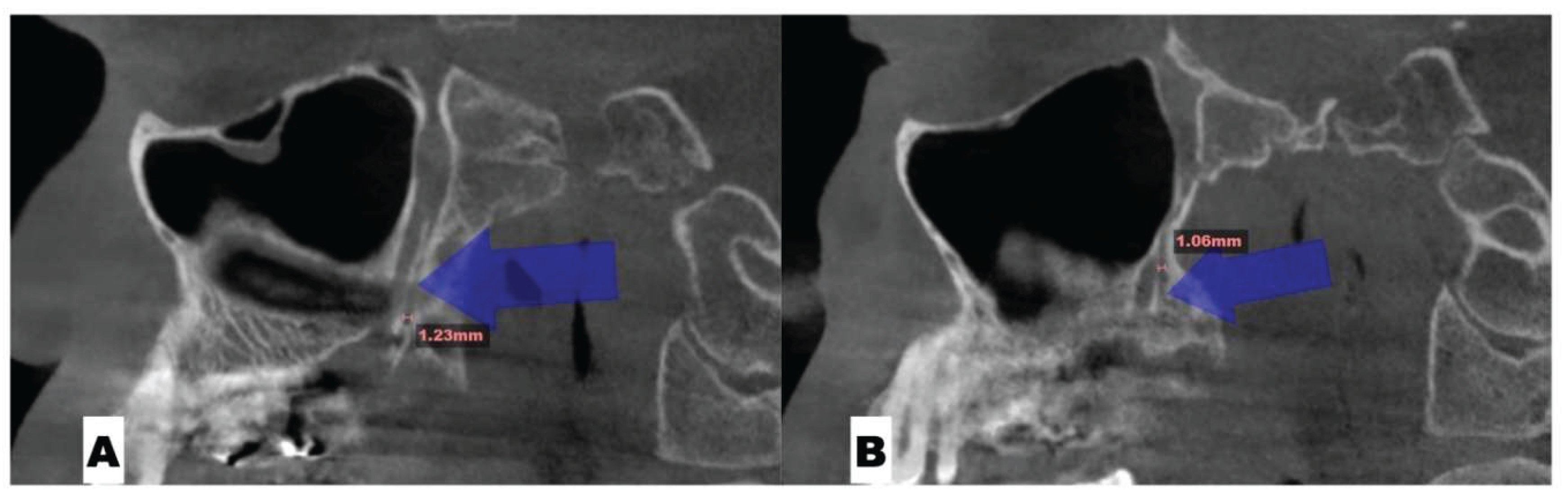

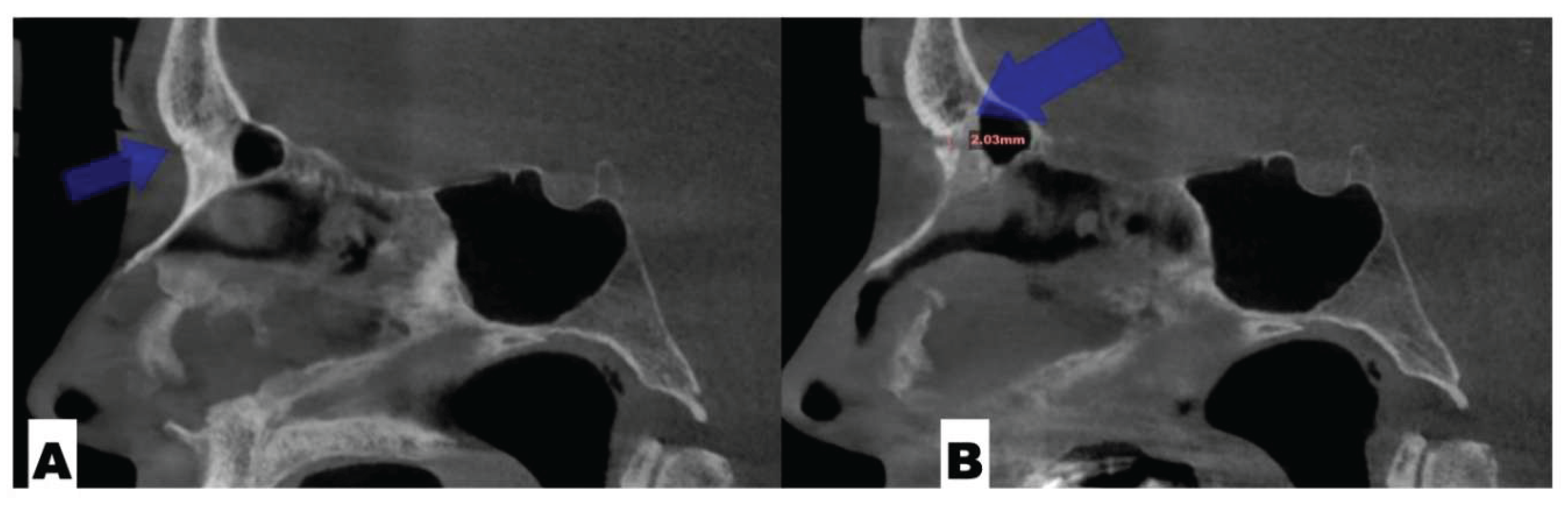

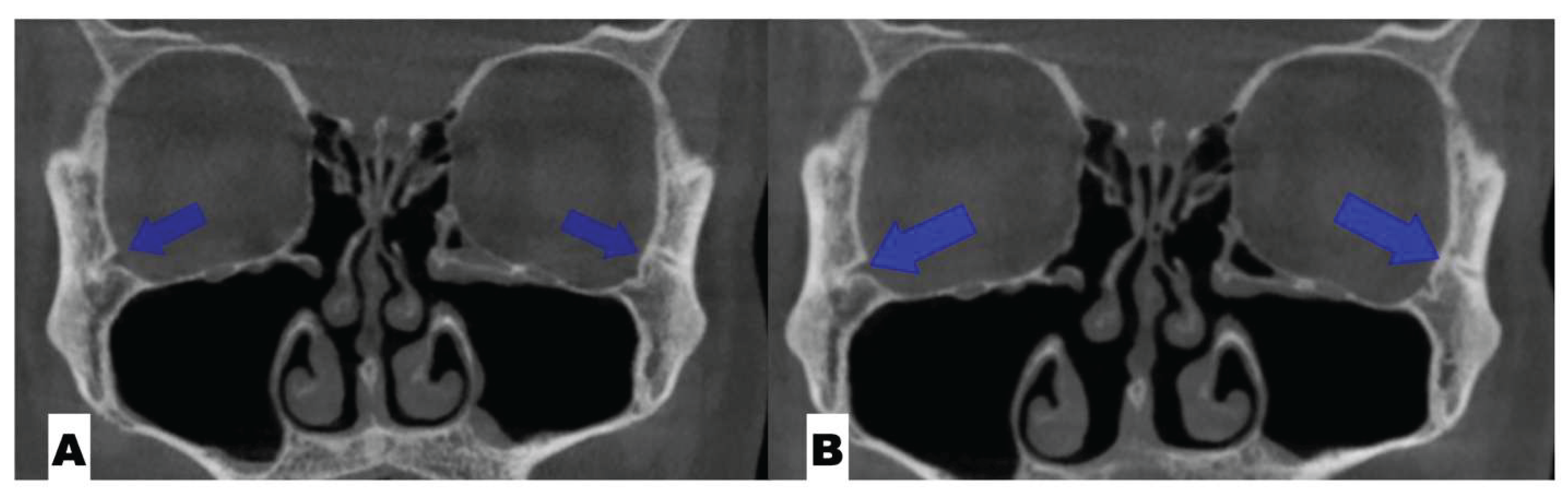

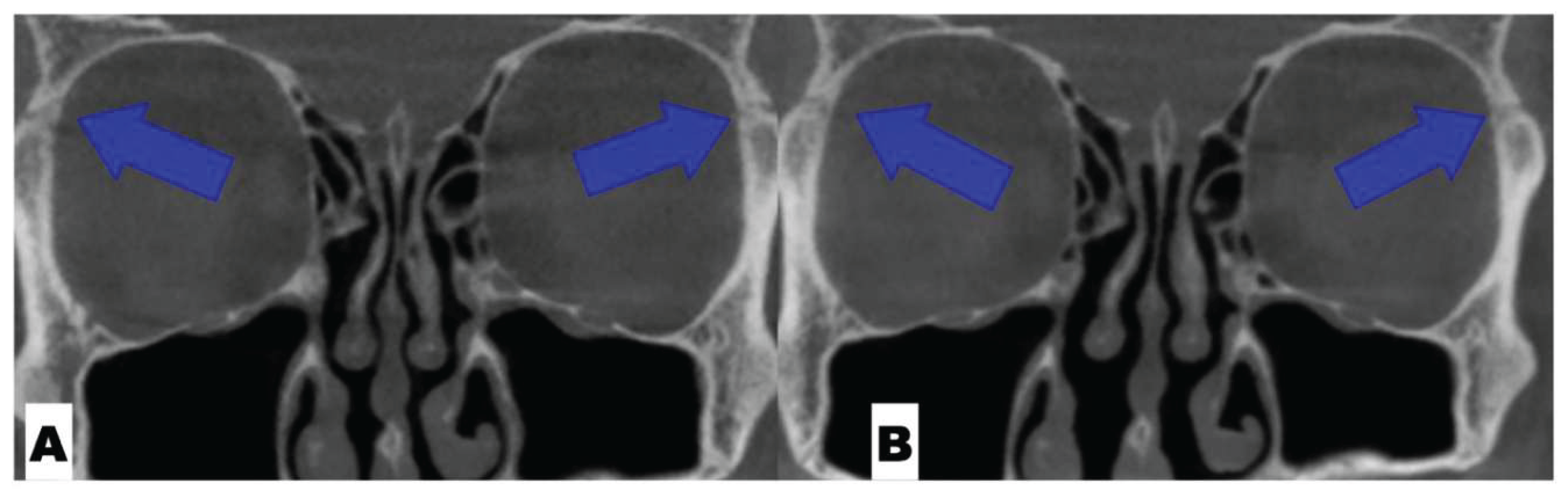

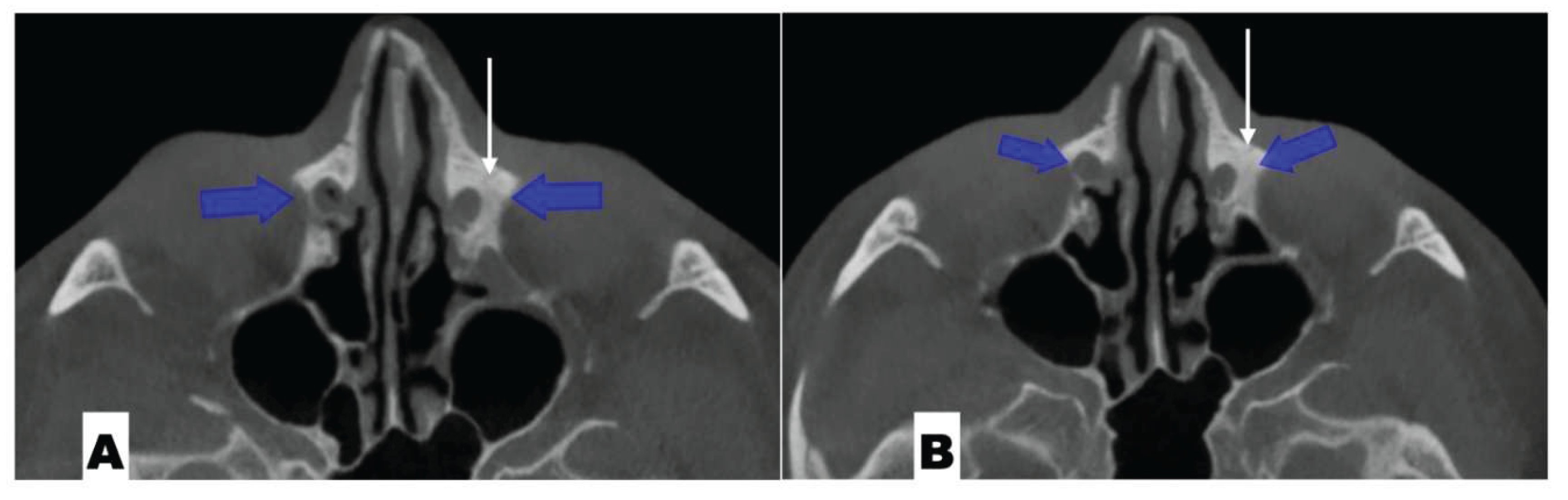

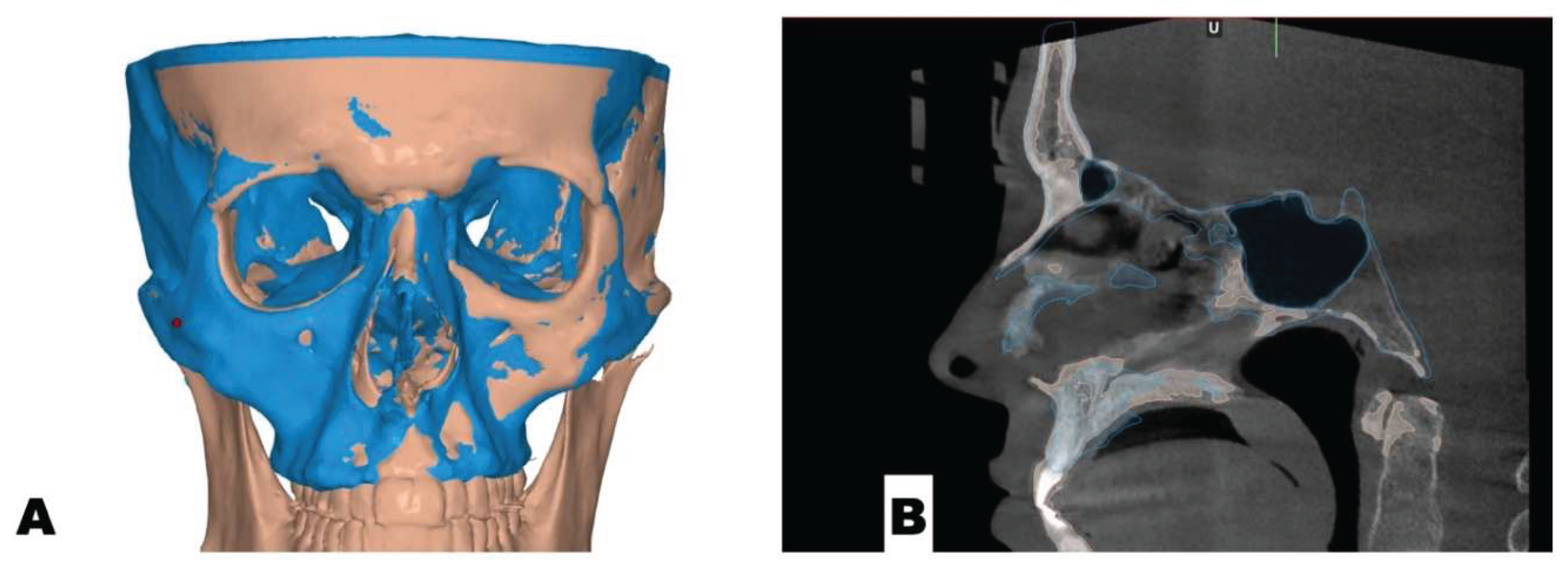

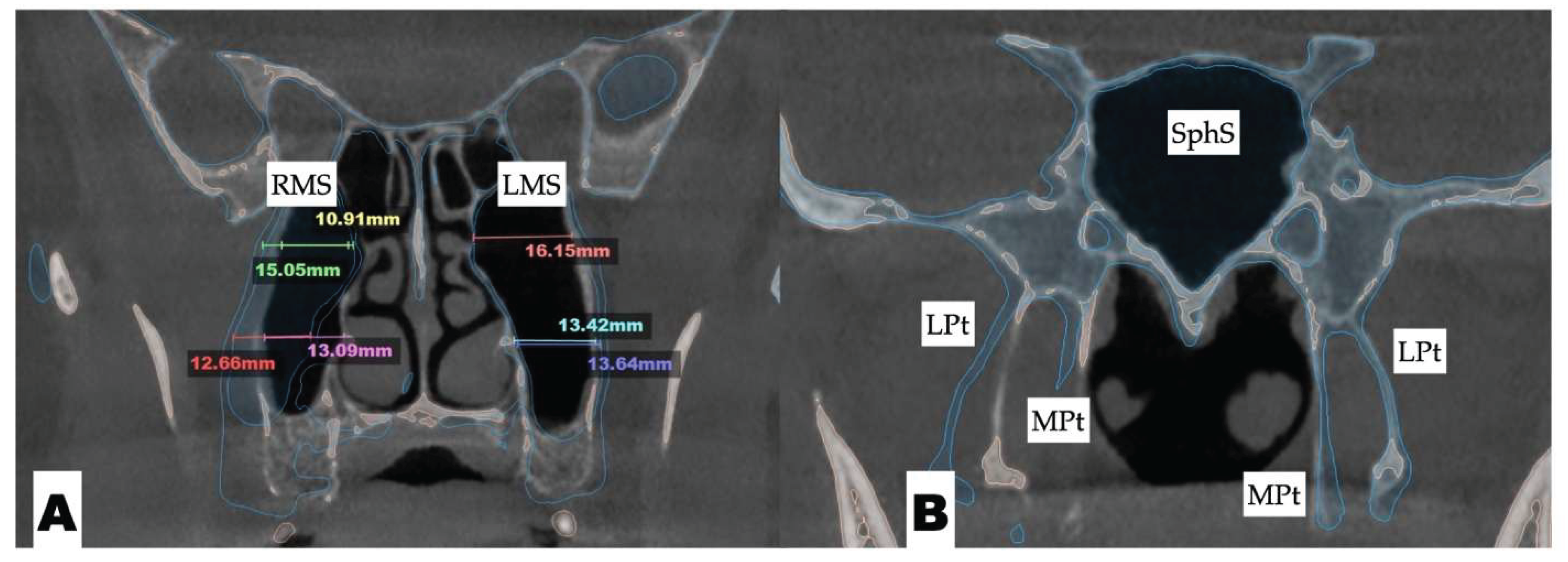

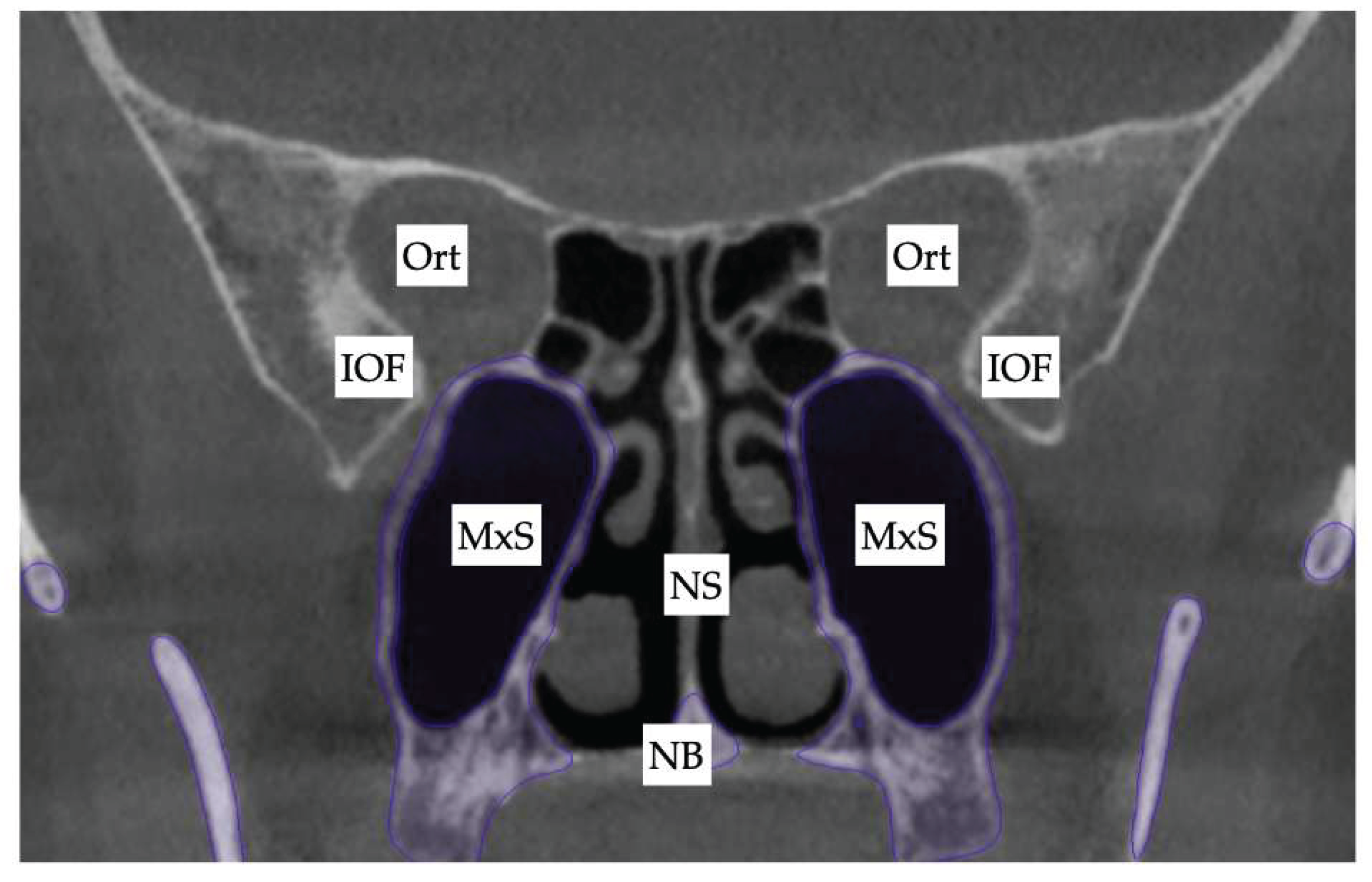

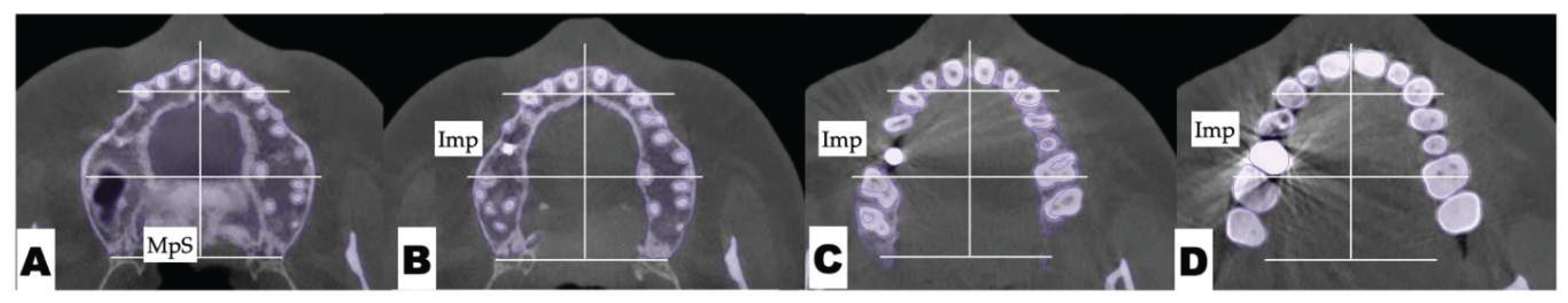

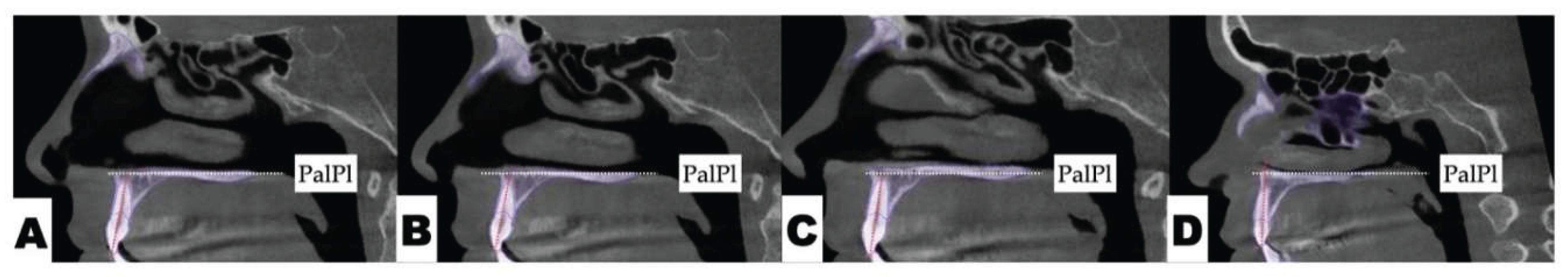

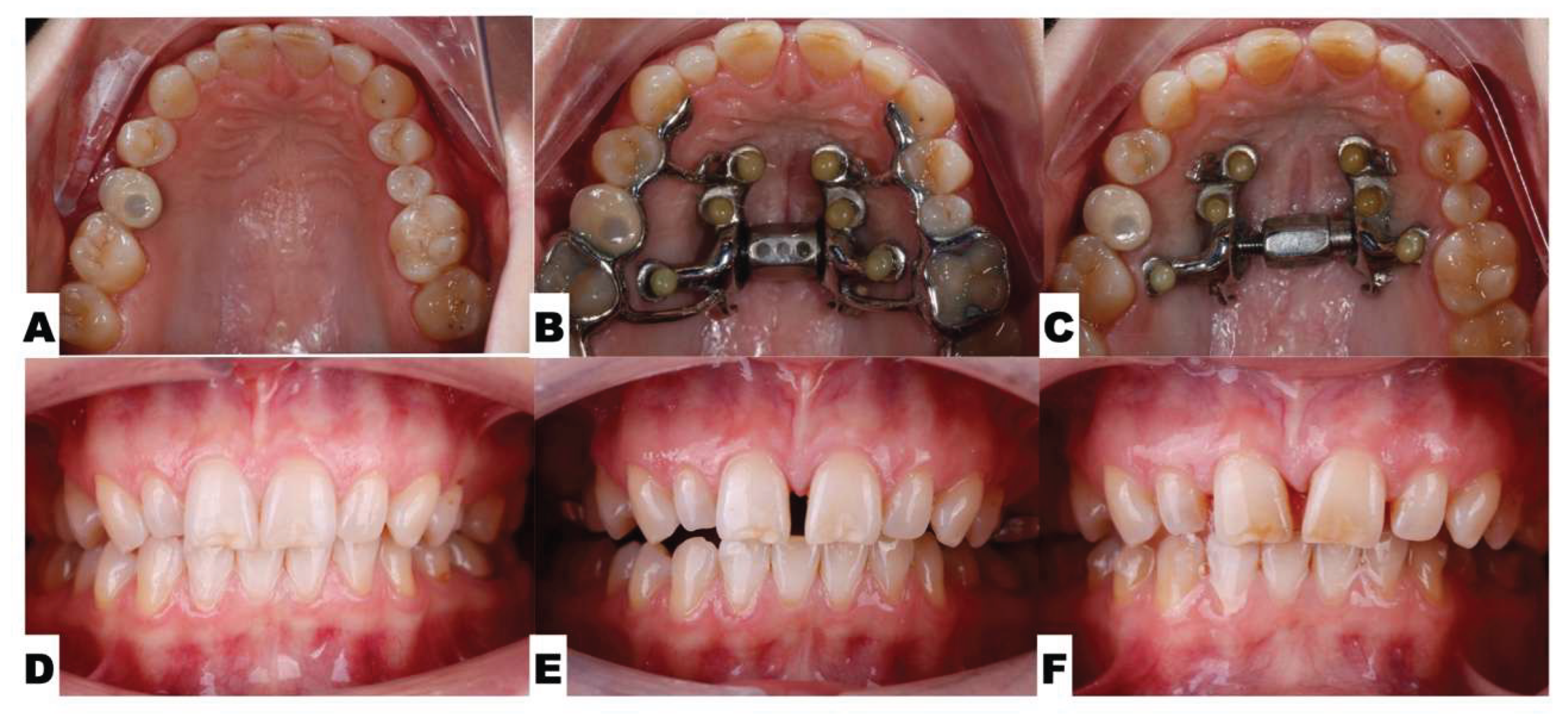

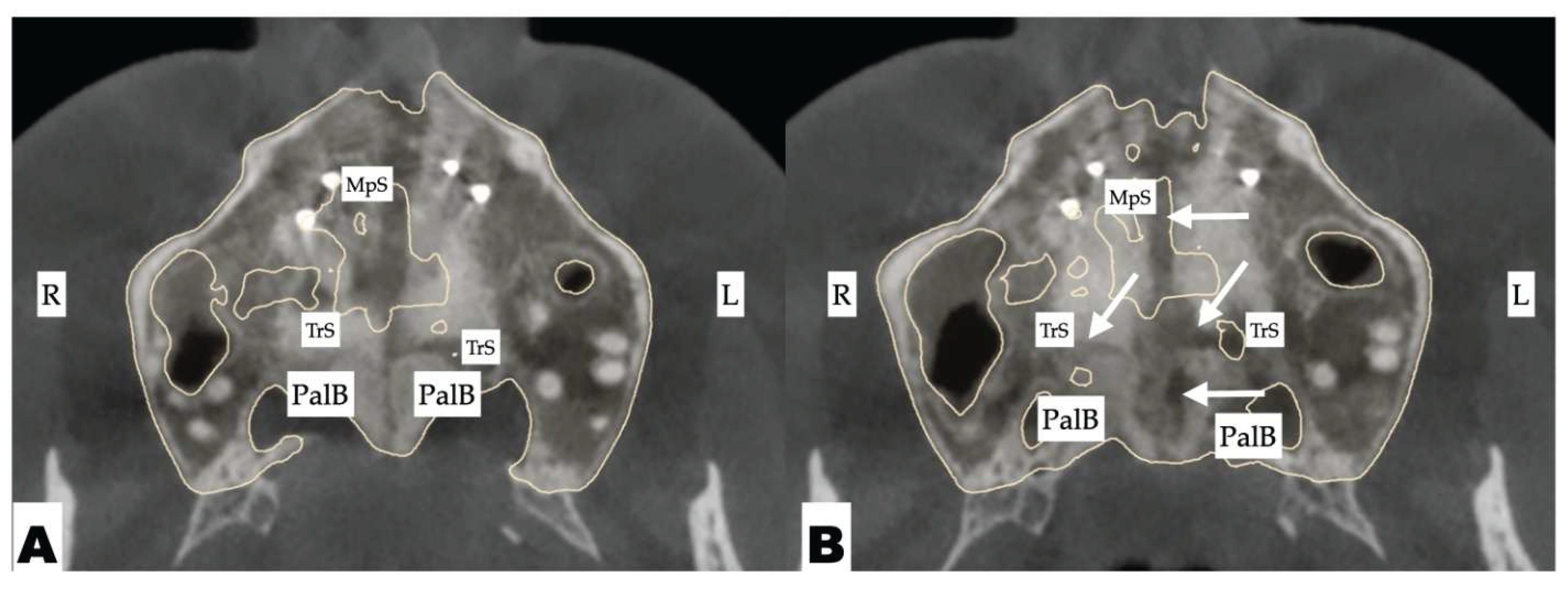

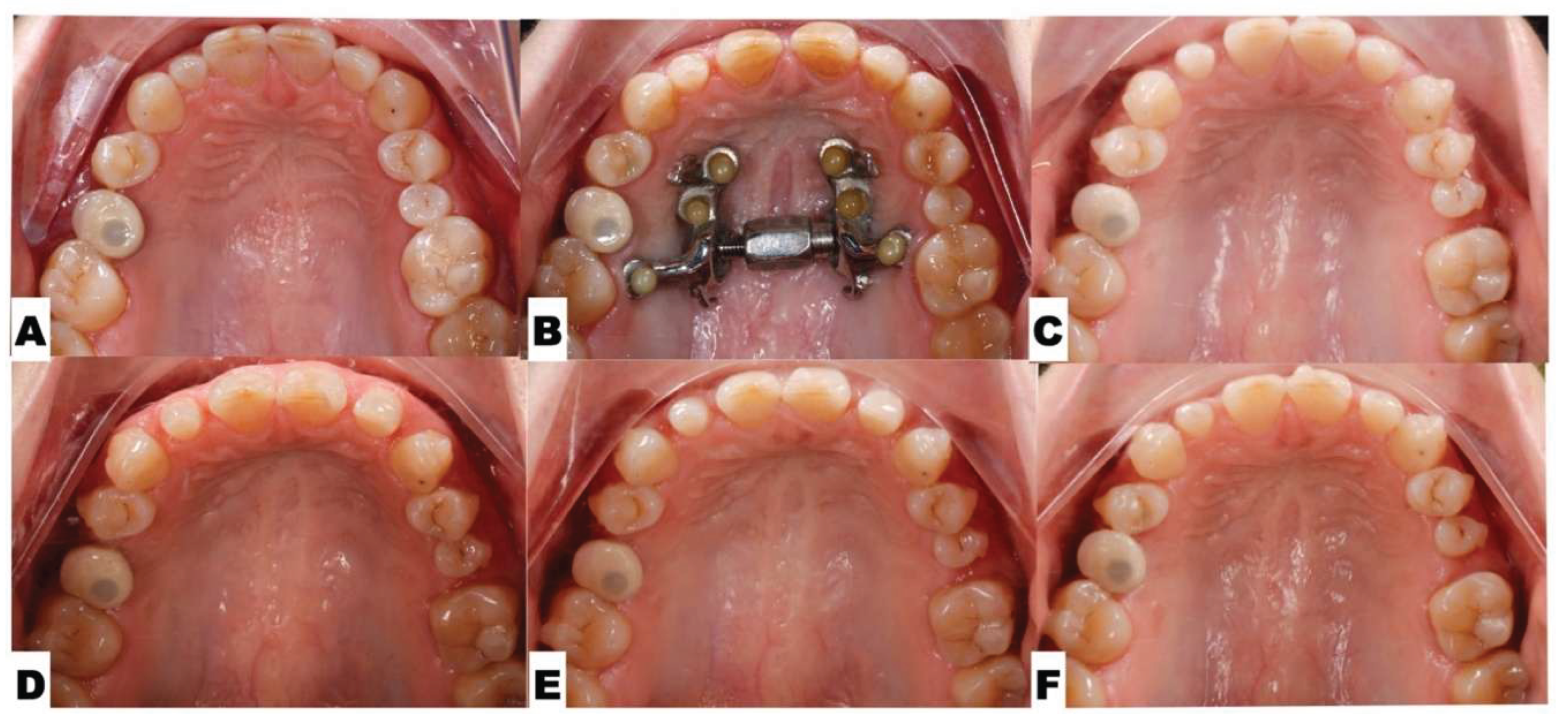

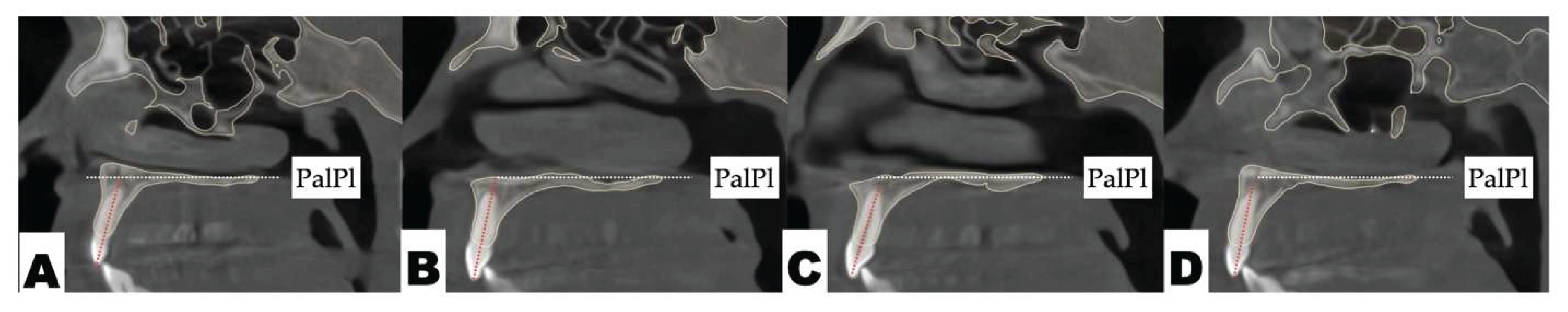

Background: While mini-screw-assisted rapid palatal expansion (MARPE) is effective for correcting maxillary transverse deficiency in adults, perimaxillary suture disarticulation—particularly at the pterygomaxillary junction—can be inconsistent. This study evaluates skeletal and dentoalveolar outcomes of a novel 3D-guided midpalatal piezocorticotomy-assisted MARPE protocol, focusing on expansion symmetry and pre-existing asymmetries. Methods: Three adult patients were retrospectively analyzed after treatment with 3D-guided midpalatal piezocorticotomy-assisted MARPE expansion and one with non-guided midpapalatal piezocorticotomy and MARPE expansion. Surgical guides were digitally designed using CBCT data to align with the nasal septum orientation in multiple planes. Perimaxillary suture disarticulation was measured pre- and post-expansion, and dentoalveolar changes were evaluated. Post-expansion asymmetries were addressed using directly printed aligners. Results: Complete midpalatal suture separation (mean 8.48 mm), involving both anterior and posterior nasal spine regions, was achieved in one patient. Bilateral pterygomaxillary disarticulation averaged 1.06–1.23 mm, resulting in forward–outward rotation of the nasomaxillary complex. Additional separation occurred at the frontonasal (2.03 mm) and vomeromaxillary (1–2 mm) sutures, with no significant changes in orbital or peri-orbital sutures. One patient presented with pre-existing dentoalveolar asymmetry, which intensified the perceived post-expansion imbalance but was successfully corrected with directly printed aligners. In the second case, 5.6 mm of suture separation resulted in a limited lateral nasal width increase (<1.5 mm), while maxillary base expansion exceeded 6 mm. A significant canine plane cant (1.2 mm) and divergent axial inclinations of the maxillary central incisors relative to the palatal plane were also observed. In the second case, a non-impactful palatal bone fracture with asymmetric displacement of the left palatine fragment was documented. After 16 months of aligner therapy, all cases exhibited favorable remodeling of the palatal structures, midpalatal suture, and alveolar processes, accompanied by improved dental alignment, occlusal plane symmetry, and mandibular dentoalveolar adaptation. The dento-alveolar expansion achieved in the third case over the course of 16 months of treatment was approximated at 4 mm. The fourth case showed consistent improvement with direct printed aligners after MARPE midpalatal diasrticulation of 11 mm after experiencing minor bone fracture. Conclusions: Human skulls exhibit considerable variability between the left and right sides, which can influence spatial balance. Pre-existing cranial asymmetries appear to be the primary contributors to asymmetry following MARPE treatment. Careful evaluation of dentoalveolar discrepancies and axial tooth inclinations is essential for preventing and managing potential asymmetric dental arch outcomes during the post-expansion phase. Although peri-maxillary bone fractures are relatively uncommon, their occurrence is influenced by multiple factors. Adjunctive techniques, such as 3D-guided midpalatal piezocorticotomy, show promise in significantly lowering the risk of intra-expansion peri-maxillary fractures.

Keywords:

Introduction

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Sample

Surgical Protocol

D Surgical Guide Design

Osteotomy Planning

Patent Protection

Postoperative Assessment

| Maxillary canine plane | -1.2 L |

| Mandibular canine plane | 0.3 R |

| Chin cant | -0.9 L |

| Body cant | -1.6 L |

| Gonion cant | 0.2 R |

| 2nd molar cant | -0.4 L |

| Parameter | Before Expansion | After Expansion |

|---|---|---|

| Maxillary canine plane | -1.2 L | -4.1 L |

| Mandibular canine plane | 0.3 R | -1.1 L |

| Chin cant | -0.9 L | -2.0 L |

| Body cant | -1.6 L | -3.8 L |

| Gonion cant | 0.2 R | -5.3 L |

| 2nd molar cant | -0.4 L | -0.4 L |

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

5. Patents

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MARPE | Mini-Screw-Assisted Rapid Palatal Expansion |

| ANS | Anterior Nasal Spine |

| PNS | Posterior Nasal Spine |

| DPA | Directly Printed Aligners |

| CBCT | Cone-Beam Computer Tomography |

| MSE | Maxillary Skeletal Expander |

References

- D. P. Brunetto, C. E. Moschik, R. Dominguez-Mompell, E. Jaria, E. F. Sant’Anna, and W. Moon, “Mini-implant assisted rapid palatal expansion (MARPE) effects on adult obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) and quality of life: a multi-center prospective controlled trial,” Prog. Orthod., vol. 23, no. 1, p. 3, Feb. 2022. [CrossRef]

- D. Cantarella et al., “Zygomaticomaxillary modifications in the horizontal plane induced by micro-implant-supported skeletal expander, analyzed with CBCT images,” Prog. Orthod., vol. 19, no. 1, p. 41, Oct. 2018. [CrossRef]

- D. Cantarella et al., “Digital Planning and Manufacturing of Maxillary Skeletal Expander for Patients with Thin Palatal Bone,” Med. Devices Auckl. NZ, vol. 14, pp. 299–311, 2021. [CrossRef]

- D. C. Zárate-Guerra and G. Gutiérrez-Tapia, “[Structural changes in the craniofacial complex induced by microimplant-supported skeletal expander - MSE. a review],” Rev. Cient. Odontol. Univ. Cient. Sur, vol. 13, no. 2, p. e243, 2025. [CrossRef]

- A. Alan, Y. Kaya, and K. Sancak, “Mid-facial skeletal and soft tissue changes after maxillary skeletal expander application: a retrospective CBCT study,” BMC Oral Health, vol. 25, no. 1, p. 1168, July 2025. [CrossRef]

- S. Mehta et al., “Long-term effects of mini-screw-assisted rapid palatal expansion on airway,” Angle Orthod., vol. 91, no. 2, pp. 195–205, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Mehta, V. Gandhi, M. L. Vich, V. Allareddy, A. Tadinada, and S. Yadav, “Long-term assessment of conventional and mini-screw-assisted rapid palatal expansion on the nasal cavity,” Angle Orthod., vol. 92, no. 3, pp. 315–323, May 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Camacho, V. Certal, and R. Capasso, “Comprehensive review of surgeries for obstructive sleep apnea syndrome,” Braz. J. Otorhinolaryngol., vol. 79, no. 6, pp. 780–788, 2013. [CrossRef]

- S. Zaghi et al., “Maxillomandibular Advancement for Treatment of Obstructive Sleep Apnea: A Meta-analysis,” JAMA Otolaryngol.-- Head Neck Surg., vol. 142, no. 1, pp. 58–66, Jan. 2016. [CrossRef]

- R. N. Aurora et al., “Practice parameters for the surgical modifications of the upper airway for obstructive sleep apnea in adults,” Sleep, vol. 33, no. 10, pp. 1408–1413, Oct. 2010. [CrossRef]

- S. Koval, V. Kolesnyk, and D. Chepanova, “Applications of the Novel Midpalatal Piezocorticotomy Guide for MARPE Midfacial Skeletal Expansion,” J. Clin. Med., vol. 14, no. 13, p. 4728, July 2025. [CrossRef]

- O. A. Raslan, A. Ozturk, N. Pham, J. Chang, E. B. Strong, and M. Bobinski, “A Comprehensive Review of Cross-Sectional Imaging of the Nasolacrimal Drainage Apparatus: What Radiologists Need to Know,” Am. J. Roentgenol., vol. 213, no. 6, pp. 1331–1340, Dec. 2019. [CrossRef]

- G. W. Arnett and R. T. Bergman, “Facial keys to orthodontic diagnosis and treatment planning. Part I,” Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. Off. Publ. Am. Assoc. Orthod. Its Const. Soc. Am. Board Orthod., vol. 103, no. 4, pp. 299–312, Apr. 1993. [CrossRef]

- G. W. Arnett et al., “Soft tissue cephalometric analysis: diagnosis and treatment planning of dentofacial deformity,” Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. Off. Publ. Am. Assoc. Orthod. Its Const. Soc. Am. Board Orthod., vol. 116, no. 3, pp. 239–253, Sept. 1999. [CrossRef]

- C. Calvo-Henriquez et al., “Pediatric maxillary expansion to treat nasal obstruction,” Acta Otorrinolaringol. Esp., vol. 76, no. 3, p. 512220, 2025. [CrossRef]

- F. Yi et al., “Changes of the upper airway and bone in microimplant-assisted rapid palatal expansion: A cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) study,” J. X-Ray Sci. Technol., vol. 28, no. 2, pp. 271–283, 2020. [CrossRef]

- C. Liu et al., “The short- and long-term changes of upper airway and alar in nongrowing patients treated with Mini-Implant Assisted Rapid Palatal Expansion (MARPE): a systematic review and meta-analysis,” BMC Oral Health, vol. 23, no. 1, p. 820, Oct. 2023. [CrossRef]

- C.-M. Marín et al., “Correlation of age and skeletal effects after miniscrew assisted rapid palatal expansion,” J. Clin. Exp. Dent., vol. 15, no. 4, pp. e269–e276, Apr. 2023. [CrossRef]

- C. McMullen et al., “Three-dimensional evaluation of skeletal and dental effects of treatment with maxillary skeletal expansion,” Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. Off. Publ. Am. Assoc. Orthod. Its Const. Soc. Am. Board Orthod., vol. 161, no. 5, pp. 666–678, May 2022. [CrossRef]

- D. C. Zárate-Guerra and G. Gutiérrez-Tapia, “[Structural changes in the craniofacial complex induced by microimplant-supported skeletal expander - MSE. a review],” Rev. Cient. Odontol. Univ. Cient. Sur, vol. 13, no. 2, p. e243, 2025. [CrossRef]

- O. Colak et al., “Tomographic assessment of palatal suture opening pattern and pterygopalatine suture disarticulation in the axial plane after midfacial skeletal expansion,” Prog. Orthod., vol. 21, no. 1, p. 21, July 2020. [CrossRef]

- D. Cantarella et al., “Changes in the midpalatal and pterygopalatine sutures induced by micro-implant-supported skeletal expander, analyzed with a novel 3D method based on CBCT imaging,” Prog. Orthod., vol. 18, no. 1, p. 34, Nov. 2017. [CrossRef]

- R. Cannavale, P. Chiodini, L. Perillo, and M. G. Piancino, “Rapid palatal expansion (RPE): Meta-analysis of long-term effects,” Orthod. Craniofac. Res., vol. 21, no. 4, pp. 225–235, Nov. 2018. [CrossRef]

- T. Baccetti, L. Franchi, C. G. Cameron, and J. A. McNamara, “Treatment timing for rapid maxillary expansion,” Angle Orthod., vol. 71, no. 5, pp. 343–350, Oct. 2001. [CrossRef]

- N. Paredes et al., “Differential assessment of skeletal, alveolar, and dental components induced by microimplant-supported midfacial skeletal expander (MSE), utilizing novel angular measurements from the fulcrum,” Prog. Orthod., vol. 21, no. 1, p. 18, July 2020. [CrossRef]

- T. S. Tunis, S. Dratler, L. Kats, and D. M. Allon, “Characterization of Pterygomaxillary Suture Morphology: A CBCT Study,” Appl. Sci., vol. 13, no. 6, Art. no. 6, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- T. K, M. S, and S. M, “Location of the centre of resistance for the nasomaxillary complex studied in a three-dimensional finite element model,” Br. J. Orthod., vol. 22, no. 3, Aug. 1995. [CrossRef]

- S. Jm, G. Rc, V. Cs, and D. Vg, “Morphometric Analysis of Pterygomaxillary Fissure in Dry Skulls and its Clinical Significance During Head and Neck Injury,” Indian J. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. Off. Publ. Assoc. Otolaryngol. India, vol. 77, no. 2, Feb. 2025. [CrossRef]

- X. Shi, X. Lin, C. Ma, M. Chen, and D. Liu, “Evaluation of changes in orbital volume in adult female patients with maxillary transverse deficiency treated with a maxillary skeletal expander,” Hua Xi Kou Qiang Yi Xue Za Zhi Huaxi Kouqiang Yixue Zazhi West China J. Stomatol., vol. 40, no. 3, pp. 314–319, May 2022. [CrossRef]

- B. Baser, M. Bolukbasi, D. Uzlu, and A. D. Ozbay, “Does MARPE therapy have effects on intracranial pressure? a clinical study,” BMC Oral Health, vol. 22, no. 1, p. 450, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- A.-R. Cho, J. H. Park, W. Moon, J.-M. Chae, and K.-H. Kang, “Short-term effects of microimplant-assisted rapid palatal expansion on the circummaxillary sutures in skeletally mature patients: A cone-beam computed tomography study,” Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. Off. Publ. Am. Assoc. Orthod. Its Const. Soc. Am. Board Orthod., vol. 161, no. 2, pp. e187–e197, Feb. 2022. [CrossRef]

- S.-R. Lee, J.-W. Lee, D.-H. Chung, and S.-M. Lee, “Short-term impact of microimplant-assisted rapid palatal expansion on the nasal soft tissues in adults: A three-dimensional stereophotogrammetry study,” Korean J. Orthod., vol. 50, no. 2, pp. 75–85, Mar. 2020. [CrossRef]

- A. Mohebbi, S. Rajaeih, M. Safdarian, and P. Omidian, “The sphenoid sinus, foramen rotundum and vidian canal: a radiological study of anatomical relationships,” Braz. J. Otorhinolaryngol., vol. 83, no. 4, pp. 381–387, July 2017. [CrossRef]

- N. Paredes et al., “Differential assessment of skeletal, alveolar, and dental components induced by microimplant-supported midfacial skeletal expander (MSE), utilizing novel angular measurements from the fulcrum,” Prog. Orthod., vol. 21, no. 1, p. 18, July 2020. [CrossRef]

- E. S. Bud et al., “Observational Study Regarding Possible Side Effects of Miniscrew-Assisted Rapid Palatal Expander (MARPE) with or without the Use of Corticopuncture Therapy,” Biology, vol. 10, no. 3, p. 187, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- T. Torkomian, F. de la Iglesia, and A. Puigdollers, “3D-printed clear aligners: An emerging alternative to the conventional thermoformed aligners? - A systematic review,” J. Dent., vol. 155, p. 105616, Apr. 2025. [CrossRef]

- B. Ludwig, K. Ojima, J. Q. Schmid, V. Knode, and R. Nanda, “Direct-printed aligners: A clinical status report,” J. Clin. Orthod. JCO, vol. 58, no. 11, pp. 658–668, Nov. 2024.

- S. Y. Lee et al., “Thermo-mechanical properties of 3D printed photocurable shape memory resin for clear aligners,” Sci. Rep., vol. 12, no. 1, p. 6246, Apr. 2022. [CrossRef]

- B. Barton et al., “Long-term assessment of skeletal and dental asymmetry after conventional and mini-implant-assisted rapid palatal expansion,” Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. Off. Publ. Am. Assoc. Orthod. Its Const. Soc. Am. Board Orthod., vol. 167, no. 4, pp. 399-408.e1, Apr. 2025. [CrossRef]

- E. Kormi, E. Peltola, N. Lusila, A. Heliövaara, J. Leikola, and J. Suojanen, “Unilateral Cleft Lip and Palate Has Asymmetry of Bony Orbits: A Retrospective Study,” J. Pers. Med., vol. 13, no. 7, p. 1067, June 2023. [CrossRef]

- R. Tandon, L. Aljadeff, S. Ji, and R. A. Finn, “Anatomic Variability of the Human Orbit,” J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. Off. J. Am. Assoc. Oral Maxillofac. Surg., vol. 78, no. 5, pp. 782–796, May 2020. [CrossRef]

- A. L. Barbera, W. J. Sampson, and G. C. Townsend, “Variation in natural head position and establishing corrected head position,” Homo Int. Z. Vgl. Forsch. Am Menschen, vol. 65, no. 3, pp. 187–200, June 2014. [CrossRef]

- U. Hanai, H. Muramatsu, and T. Akamatsu, “Maxillary Bone Fracture Due to a Miniscrew-Assisted Rapid Maxillary Expansion: A Case Report,” J. Clin. Med., vol. 14, no. 6, p. 1928, Mar. 2025. [CrossRef]

| Suture nomenclature | Associated anatomical structure | Paired/Single |

|---|---|---|

| Midpalatal | Hard palate | Single |

| Palatinomaxillary | Hard palate | Paired |

| Nasomaxillary | Bridge of the nose | Paired |

| Zygomaticomaxillary | Zygomatic arch | Paired |

| Lacrimomaxillary | Floor of the Orbit | Paired |

| Ethmoidomaxillary | Floor of the Orbit | Paired |

| Sphenomaxillary | Floor of the Orbit | Paired |

| Vomeromaxillary | Nasal septum | Paired |

| Frontomaxillary | Bridge of the nose | Paired |

| Pterygomaxillary | Maxillary sinus wall | Paired |

| Suture nomenclature | Amount of disarticulation |

|---|---|

| Midpalatal | 8.48 mm |

| Palatinomaxillary (transverse) | none |

| Nasomaxillary | 1-2 mm |

| Zygomaticomaxillary | none |

| Lacrimomaxillary | none |

| Ethmoidomaxillary | none |

| Sphenomaxillary | none |

| Vomeromaxillary | 1-2 mm |

| Frontomaxillary | 2.5 mm |

| Pterygomaxillary | 1.06-1.23 mm |

| Frontonasal | 2.03 mm |

| Frontozygomatic | None |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).