1. Introduction

Quality of life (QoL) is a multidimensional and highly subjective construct that reflects how individuals perceive their position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live, as well as their personal goals, expectations, and concerns [

1,

2]. In pediatric oncology, QoL is of particular significance, as it is shaped not only by the somatic dimensions of the disease, but also by its psychological and social repercussions on children’s or adolescents’ development [

3]. Specialized literature proposes an integrative model of QoL encompassing five essential dimensions: physical, material, emotional, social, and functional well-being [

4,

5]. Maintaining a functional state close to normal poses a major challenge for pediatric cancer patients. Aggressive treatments, frequent hospitalizations, and disruption of daily routines significantly impact emotional balance and the overall quality of life [

6,

7].

Adolescents navigating a complex phase of identity formation and emotional growth employ a variety of psychological coping mechanisms in response to serious illnesses, such as cancer. The coping strategies they adopt, whether adaptive or maladaptive, play a vital role in how effectively they manage stress and preserve their positive self-perception [

8]. Moreover, factors such as social support, disease awareness, and family context substantially influence adolescents’ psychological adjustment to their traumatic experience of cancer [

9,

10]. In this context, the present study aimed to investigate the relationship between coping strategies and perceived quality of life among adolescents diagnosed with cancer, and to examine the influence of psychosocial factors. Through this pilot approach, this study seeks to contribute to a deeper understanding of the emotional needs of this population and to provide a foundation for more effective and personalized psychological interventions to inform future research in this area.

2. Method

2.1. Objectives and Hypotheses

The objective was to explore how adolescents diagnosed with cancer adapt psychologically and emotionally to their illness within the broader framework of biopsychosocial influences. The following hypothesis was formulated:

1. Adolescents with oncological conditions predominantly would predominantly use emotion-focused and avoidance-based coping strategies.

2. Coping strategies would significantly account for perceived quality of life.

3. Adaptive coping strategies would be significantly positively correlated with higher QoL.

2.2. Participants

The study sample consisted of 20 adolescents (12 males [60%] and 8 females [40%]) aged between 12 and 18 years (mean age = 15.3 years, SD = 2), all participants had oncological diagnoses and were enrolled in the hospital school program (Bucharest, Romania) The inclusion criteria were as follows: confirmed oncological diagnosis, cognitive capacity to understand and complete self-report instruments, absence of severe neurocognitive impairment, and provision of informed consent by legal guardians.

2.3. Measures

Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory (PedsQL-Cancer Module): An internationally validated instrument comprising 27 items organized across multiple dimensions, including pain, nausea, procedural anxiety, treatment-related anxiety, cognitive difficulties, perceived physical appearance, and communication [

11]. Scores were converted to a scale from 0 to 100, with higher values indicating a better perceived quality of life. KidCOPE (10 items): A self-report questionnaire assessing coping strategies used by children and adolescents in stressful situations. The tool categorizes strategies into four main groups: active, emotional, avoidant, and maladaptive coping [

12]. The participants rated the frequency and perceived effectiveness of each strategy.

2.4. Procedure

This cross-sectional survey, with a descriptive-observational design, was conducted in February 2025. All participants completed the anonymous questionnaires in a supportive environment that ensured comfort, privacy, and clarity of instructions. The average completion time was 20–25 minutes. Ethical standards concerning confidentiality, informed consent, and the right to withdraw were strictly followed.

3. Results

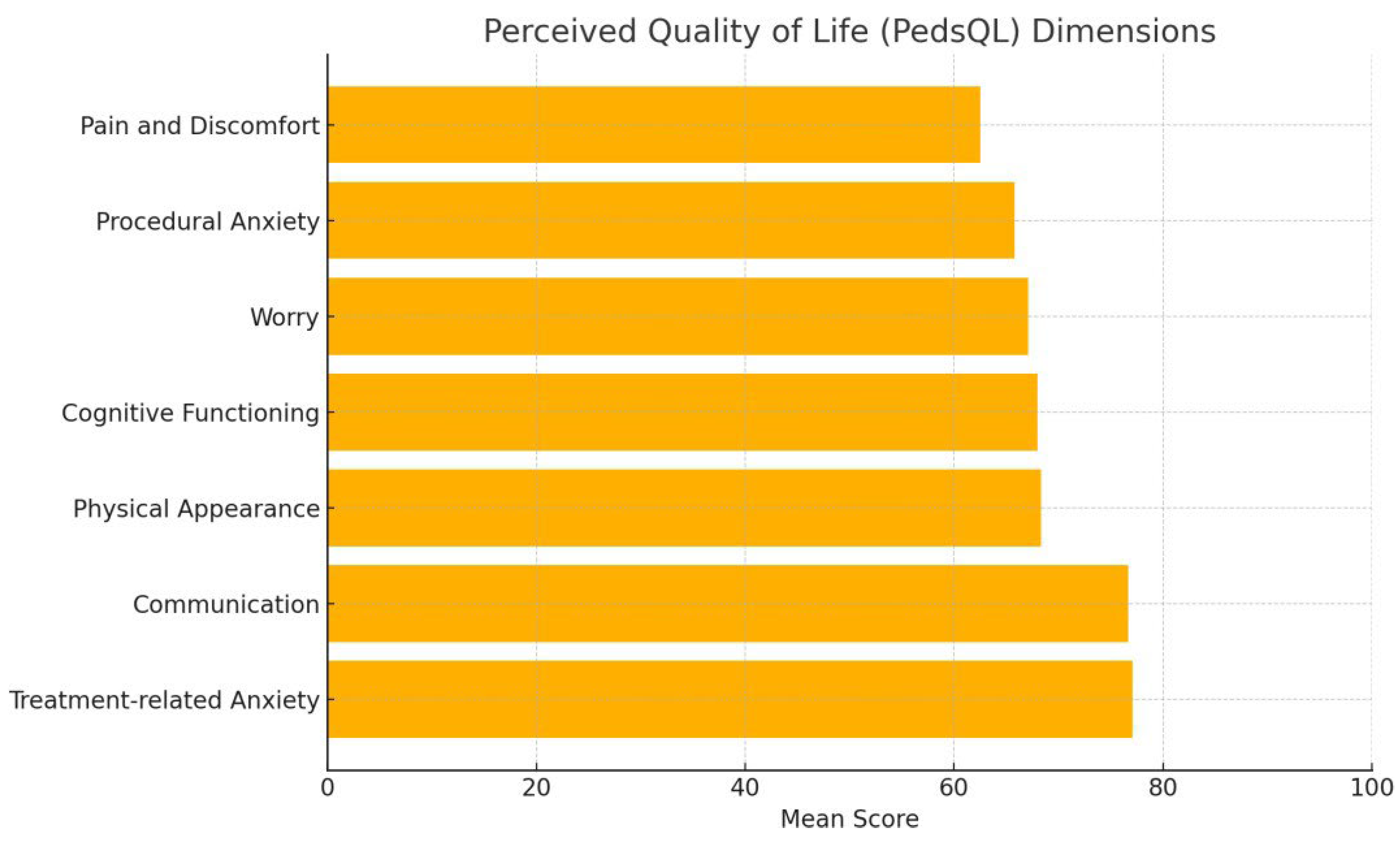

The overall mean score on the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory (PedsQL) was 70, indicating a good quality of life among the adolescents.

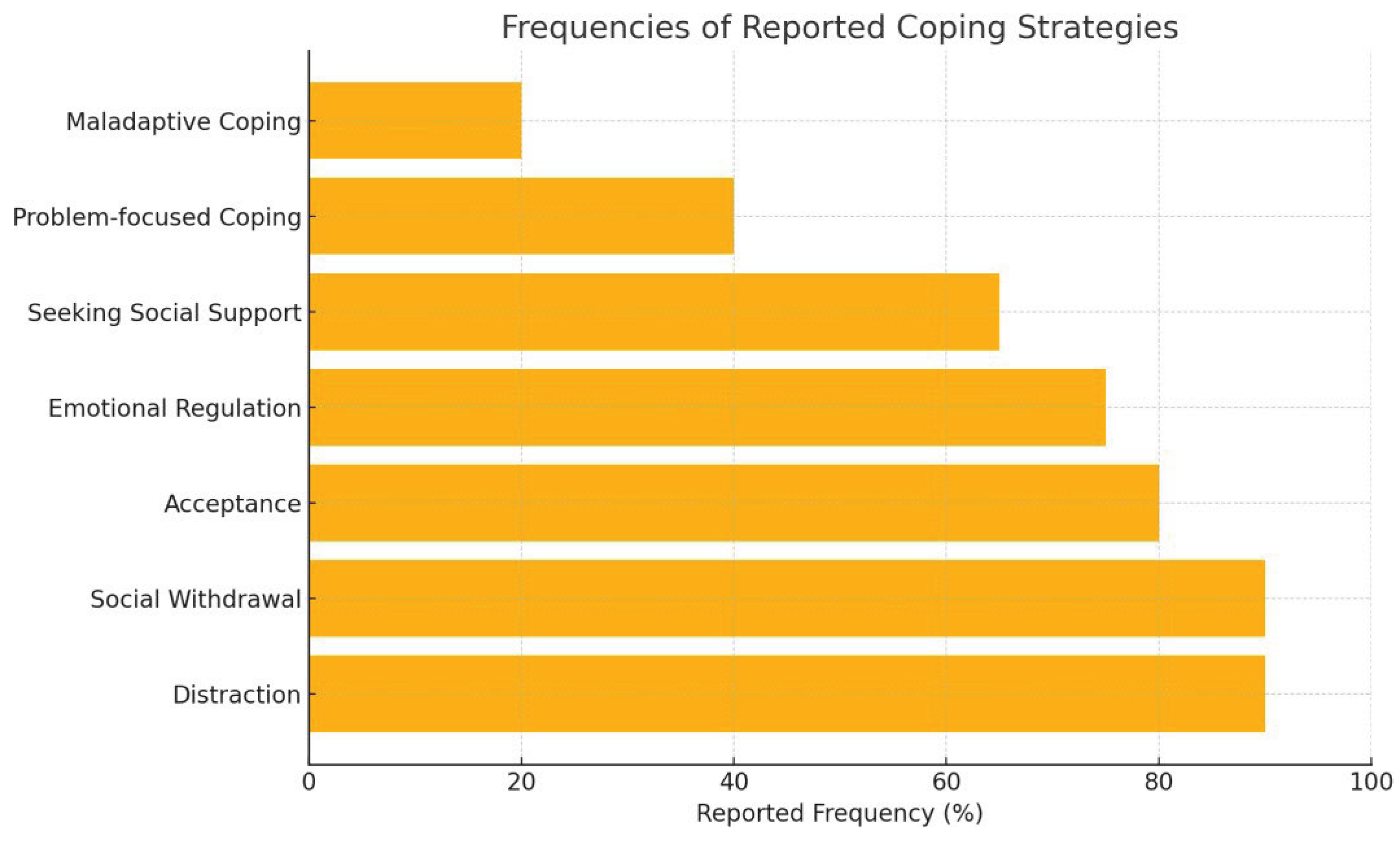

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 illustrate the distribution of coping strategies, showing that acceptance, distraction, and social withdrawal were most frequently reported, which reflects a predominant use of emotion-focused and avoidance-based strategies, thereby supporting Hypothesis 1

In the multiple regression model, the dependent variable was the total quality of life score (PedsQL), while the independent variables were the coping dimensions (adaptive, avoidant, emotional). The model accounted for approximately 26% of the variance, but this effect did not reach statistical significance (R² = .26, F(3,16) = 1.83, p = .183), thereby hypothesis 2 was not supported. Among predictors, avoidant coping was a significant negative predictor of quality of life (β = -31.49, p = .037), while adaptive coping showed a positive trend (β = 19.62, p = .081) thus not supporting hypothesis 3. Emotional coping was not significantly associated with quality of life (β = 10.98, p = .352) (see table 3).

Table 3.

Multiple linear regression results for predicting the total PedsQL score based on coping dimensions.

Table 3.

Multiple linear regression results for predicting the total PedsQL score based on coping dimensions.

| Predictor |

β |

p |

95% CI Low |

95% CI High |

| Adaptive coping |

19.62 |

.081 |

-2.71 |

41.96 |

| Avoidant coping |

-31.49 |

< .05 |

-60.82 |

-2.15 |

| Emotional coping |

10.98 |

.352 |

-13.31 |

35.28 |

4. Discussion

The analysis of data on adolescent cancer patients maintaining functional balance despite the difficulties related to the disease, treatments, and the emotional impact of hospitalization is supported by international specialized literature. The moderate-to-good quality of life score (approximately 70) was somewhat unexpected, but aligns with evidence that many AYAs can maintain functional balance despite the challenges of cancer. Studies have shown that adolescents and young adults (AYAs) diagnosed with cancer can maintain a satisfactory functional level owing to adapted psychosocial interventions and effective social support [

13]. Interventions that promote autonomy and decision-making, provide intimacy, and facilitate social/peer interactions are more effective in improving psychosocial outcomes [

14,

15]. Adolescent patients with cancer use a variety of coping strategies, including cognitive avoidance and emotional regulation. These strategies reflect both age-specific characteristics and the need for psychological protection in the face of major stressors. Studies have shown that positive cognitive coping strategies are associated with more favorable attitudes toward the disease, while defensive strategies may have the opposite effect [

16,

17]. Social support is essential for adolescents and young adults undergoing cancer treatment. This contributes to maintaining a form of normality and developing independence, strong peer relationships, and identity exploration [

18]. All sources of social support should be informed about these developmental needs in order to participate in useful and appropriate behaviors that help AYA patients cope with cancer [

19]. The low frequency of problem-focused strategies indicates the need for educational and psychological interventions to increase the sense of control and autonomy in the face of the disease. Interventions that promote autonomy and decision-making, provide intimacy, and facilitate social/peer interactions are more effective in improving psychosocial outcomes [

20]. These findings highlight the importance of an effective support in maintaining functional balance and improving their quality of life.

The results underline that adolescents’ coping strategies cannot be interpreted solely based on their frequency of use, but also by considering the perceived effectiveness of those strategies. In the case of positive reappraisal, the discrepancy between the effect of frequency and perceived effectiveness suggests that simply applying this strategy, without the belief that it works, may be associated with a negative impact on quality of life. Conversely, when adolescents perceive positive reappraisal as useful, it is linked to an increase in quality of life, highlighting the cognitive role of internal validation in the adaptive process.

Strategies focused on active problem-solving and self-soothing appear to be consistently beneficial, supporting the literature that identifies them as protective mechanisms against stress and psychosocial risk factors [

21,

22]. These behaviors involve both cognitive components (planning, analysis) and emotional components (self-regulation, tension reduction), making them effective in supporting well-being.

Interestingly, rumination—often considered a risk factor for mental health appears here with a positive association with quality of life. This result may reflect cultural or contextual differences, or the fact that a certain level of reflection on a problem can facilitate adaptation, especially when combined with other effective strategies.

5. Clinical Implications

The results of this study highlight the importance of integrating psychosocial interventions that focus not only on emotional support but also on enhancing adolescents’ sense of control and competence. Interventions should foster problem-solving skills, improve illness-related knowledge, and promote constructive emotional regulation strategies. The inclusion of peer-support models may also facilitate emotional expression and normalization of the illness experience. Given that avoidant coping was negatively associated with quality of life, interventions may benefit from targeting the reduction of maladaptive avoidance and the strengthening of adaptive strategies

6. Limitations and Directions for Future Research

This study has several limitations. The small sample size and the cross-sectional design limit the generalizability of the findings and preclude causal inferences. Furthermore, the self-report nature of the instruments may introduce bias due to social desirability or differing levels of self-awareness. Future research should consider longitudinal designs, larger and more diverse samples, and include qualitative components to capture the nuanced emotional experiences of adolescents living with cancer. As this was a pilot study, the small sample size should be interpreted as exploratory, providing preliminary evidence rather than definitive conclusions.

7. Conclusions

The oncological adolescents in the sample perceived quality of life at a moderate to good level, highlighting the positive relationships with medical staff and acceptance of treatment, while physical pain and procedural anxiety remain important challenges.

Coping mechanisms are predominantly oriented towards emotional avoidance and affective support, and it is necessary to promote problem-solving strategies and psychosocial interventions adapted to support resilience, self-efficacy, and emotional development. Although preliminary, these findings provide tentative guidance for designing psychosocial programs that foster resilience, self-efficacy, and healthy emotional development in adolescent oncology patients.

Author Contributions

Authors contributed equally to the design of the study, data collection, interpretation of the results and drafting of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of Carol Davila University of Medicine and Pharmacy in carrying out this research.

Ethical Compliance

Parental consent was obtained as part of enrollment in the hospital school program, which included approval for participation in research activities. Adolescents provided informed assent by voluntarily completing the anonymous questionnaire. No identifying data were collected, and the study involved no risk. Ethical approval for the study was granted by the Ethics Council of the Clinical Institute Fundeni, Bucharest, Romania (Approval No. 2876/27.01.2025), in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no financial or institutional conflicts of interest related to the content of this article.

References

- Teoli D, Bhardwaj A. Quality of life. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK553165/.

- Licu M, Ionescu CG, Păun S. Quality of life in cancer patients: The modern psycho-oncologic approach for Romania—A review. Curr Oncol. 2023;30(7):6964–6975. [CrossRef]

- Anthony SJ, Selkirk E, Sung L, Klaassen RJ, Dix D, Scheinemann K, Klassen AF. Considering quality of life for children with cancer: A systematic review of patient-reported outcome measures and the development of a conceptual model. Qual Life Res. 2017;23(3):771–789. [CrossRef]

- Rosan C. Quality of life in pediatric oncology: An integrative review. J Pediatr Nurs. 2016;31(3):291–300. [CrossRef]

- Licu M, Popescu DM, Ionescu CG, Voinea O, Stoica L, Cotel A. Navigating cancer: Mental adjustment as predictor of somatic symptoms in Romanian patients—A cross-sectional study. Rom J Mil Med. 2025;128(1):27–35. [CrossRef]

- Nathan PC, Patel SK, Dilley K, Goldsby R, Harvey J, Jacobsen C, et al. Guidelines for identification and management of late effects in survivors of childhood cancer. Pediatrics. 2008;121(3):e705–e713. [CrossRef]

- Vetsch J, Wakefield CE, McGill BC, Cohn RJ, Ellis SJ, Stefanic N, Sansom-Daly UM. Educational and vocational goal disruption in adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 2018;27(3):532–538. [CrossRef]

- Sung L, Klaassen RJ, Dix D, Pritchard S, Yanofsky R, Dzolganovski B, Klassen AF. Identification of paediatric cancer patients with poor quality of life. Br J Cancer. 2009;100(1):82–88. [CrossRef]

- Zebrack B, Kent EE, Keegan TH, Kato I, Smith AW; AYA HOPE Study Team. “Cancer sucks,” and other ponderings by adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2014;32(1):1–15. [CrossRef]

- Niță E, Jianu MM, Constantin C, Popa MC. The distress of adolescents with cancer in Romania: Pilot study. Anthropol Res Stud. 2025;15:393–401. [CrossRef]

- Varni JW, Burwinkle TM, Katz ER, Meeske K, Dickinson P. The PedsQL in pediatric cancer: reliability and validity of the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory Generic Core Scales, Multidimensional Fatigue Scale, and Cancer Module. Cancer. 2002;94(7):2090–2106. [CrossRef]

- Spirito A, Stark LJ, Williams C. Development of a brief coping checklist for use with pediatric populations. J Pediatr Psychol. 1988;13(4):555–574. [CrossRef]

- Breuer N, Sender A, Daneck L, Mentschke L, Leuteritz K, Friedrich M, et al. How do young adults with cancer perceive social support? A qualitative study. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2017;35(3):292–308. [CrossRef]

- Thornton CP, Ruble K, Kozachik S. Psychosocial interventions for adolescents and young adults with cancer: An integrative review. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2020;37(6):408–422. [CrossRef]

- Harrison A, Mtukushe B, Kuo C, Wilson-Barthes M, Davidson B, Sher R, et al. Better together: Acceptability, feasibility and preliminary impact of chronic illness peer support groups for South African adolescents and young adults. J Int AIDS Soc. 2023;26(Suppl 4):e26148. [CrossRef]

- Semerci R, Savaş EH, Uysal G, Alki K. The predictive power of coping strategies of pediatric oncology patients on their quality of life and their attitudes toward diseases. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2024;71(10):e31196. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad Z, Venkataraman V, Markwart M, Abrams AN, Temel JS, Perez GK. Closing the gap: Proposing a socio-ecological framework to make cancer clinical trials more accessible, equitable, and acceptable to adolescents and young adults. Oncologist. 2024;29(11):918–921. [CrossRef]

- Hotchkiss ME, Ahmad ZN, Ford JS. Cancer peer connection in the context of adolescent and young adult cancer: A qualitative exploration. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2023;12(1):83–92. [CrossRef]

- Pennant SC, Lee S, Holm S, Triplett KN, Howe-Martin L, Campbell R, et al. The role of social support in adolescent/young adults coping with cancer treatment. Children (Basel). 2020;7(1):2. [CrossRef]

- Thornton CP, Perrin N, Kozachik S, Lukkahatai N, Ruble K. Biobehavioral influences of stress and inflammation on mucositis in adolescents and young adults with cancer: Results from a pilot study. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2023;12(3):340–348. [CrossRef]

- Jurek K, Niewiadomska I, Chwaszcz J. The effect of received social support on preferred coping strategies and perceived quality of life in adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sci Rep. 2024;14:21686. [CrossRef]

- Hilt LM, Pollak SD. Characterizing the ruminative process in young adolescents. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2013;42(4):519–530. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).