1. Introduction

Botulism is a rare yet potentially fatal neuroparalytic syndrome caused by botulinum neurotoxins (BoNTs), most commonly produced by the bacterium Clostridium botulinum, and, less frequently, by Clostridium butyricum and Clostridium baratii [

1]. Human botulism manifest in several distinct clinical forms: infant botulism, wound botulism, and iatrogenic botulism. Among these, foodborne botulism is the most recognized and frequently reported in outbreak settings. Foodborne botulism represents a public health emergency due to its rapid onset and capacity to cause severe, life-threatening illness [

1,

2]. It occurs following ingestion of preformed neurotoxin in contaminated food which inhibit acetylcholine release at neuromuscular junctions, resulting in progressive flaccid paralytic illness [

3]. Symptoms typically begin with cranial nerve involvement, such as blurred vision, ptosis, and dysphagia, and may progress to respiratory muscle involvement, leading to respiratory failure and death if untreated [

4,

5].

The cornerstone of foodborne botulism treatment is the prompt administration of botulinum antitoxin, which neutralizes unbound toxin and can halt disease progression if administered early [

4,

5]. While it does not reverse established paralysis, early use has been associated with improved clinical outcomes [

4]. In recent years, additional therapeutic options such as 3,4-diaminopyridine (3,4-DAP) and other supportive measures such as mechanical ventilation and intensive care respiratory support, have been explored, particularly for severe or refractory cases [

6]. However, current evidence supporting these treatments remains limited and heterogeneous, both in design and outcome reporting [

4].

With the emergence of these alternative treatments and the recent international outbreaks in 2024, including a fatal cluster in Saudi Arabia and a large-scale incident in Russia, there is a growing need to re-evaluate available therapeutic strategies [

7,

8]. Thus, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to synthesize the most current evidence on the effectiveness of available treatments for foodborne botulism. This study aimed to evaluate the clinical success of botulinum antitoxin, while also examining the effectiveness of supportive care and adjunctive therapies. In addition to estimating pooled success rates for individual treatments, we aimed to compare effectiveness across treatment groups, accounting for heterogeneity and potential publication bias. Consolidating the available clinical evidence, this review seeks to inform both current practice and future research efforts in the management of foodborne botulism.

2. Results

2.1. Characteristics of Included Studies

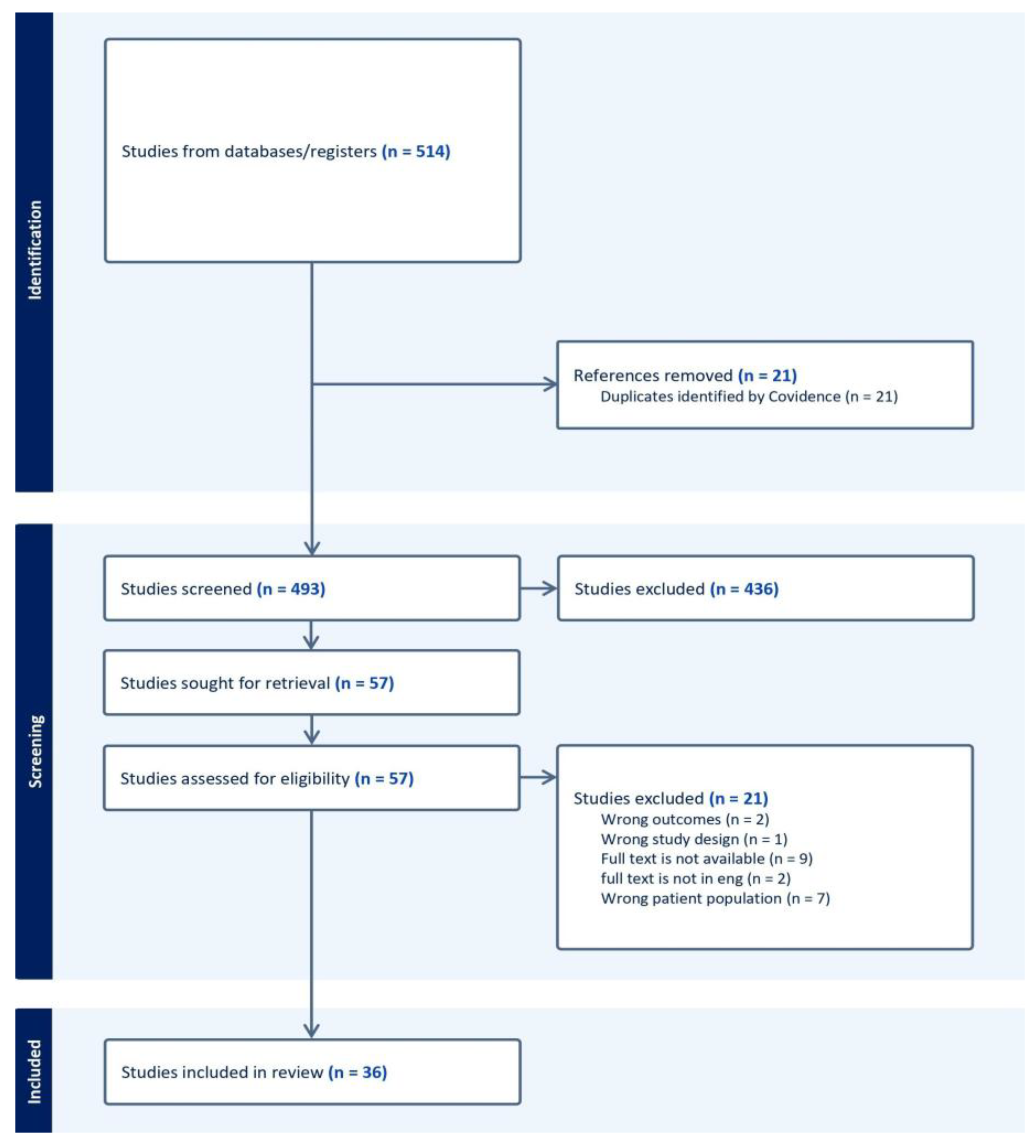

A total of 1,182 papers were generated from our search and were subsequently screened. Of which PubMed yielded 752 articles, 84 studies met our inclusion criteria and Web of Science yielded 430 studies, of which 310 met inclusion criteria for full text review. 36 studies were included in this meta-analysis, including 17 case reports, 17 case series, and 2 observational cohort studies. Collectively, these studies represented 417 patients diagnosed with botulism who received one or more of the following treatments: anti-toxin (n = 334), supportive care (n = 21), guanidine (n = 3), or combination therapy (n = 4). Two comparative studies assessed anti-toxin in relation to either combination therapy or supportive care. The primary outcome across all studies was treatment success, most commonly defined as improvement (including partial or full recovery). Details of the antitoxin formulations used in the included studies are summarized in

Supplementary Table S1.

2.2. Single-Group Pooled Success Rates

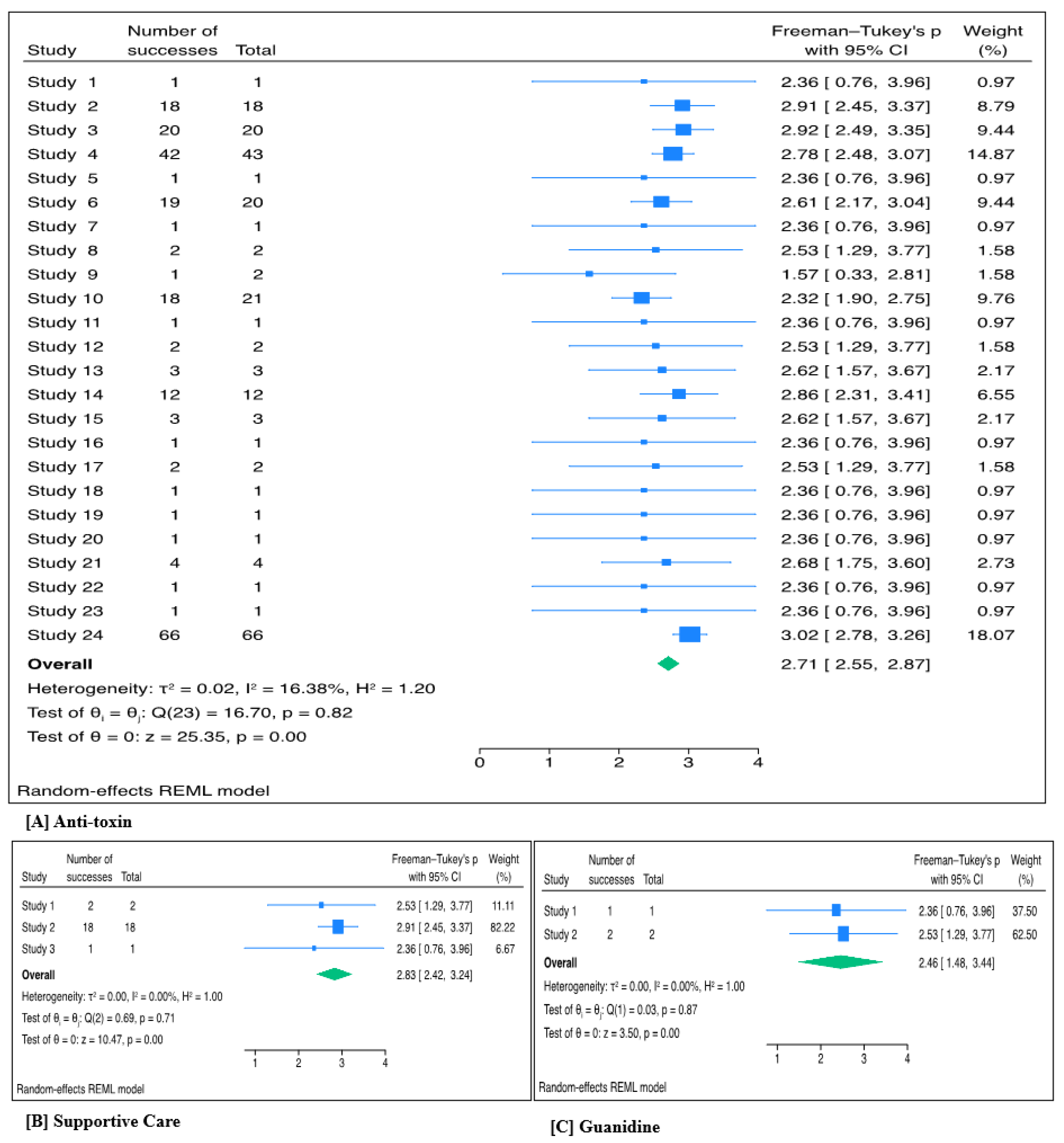

2.2.1. Anti-Toxin

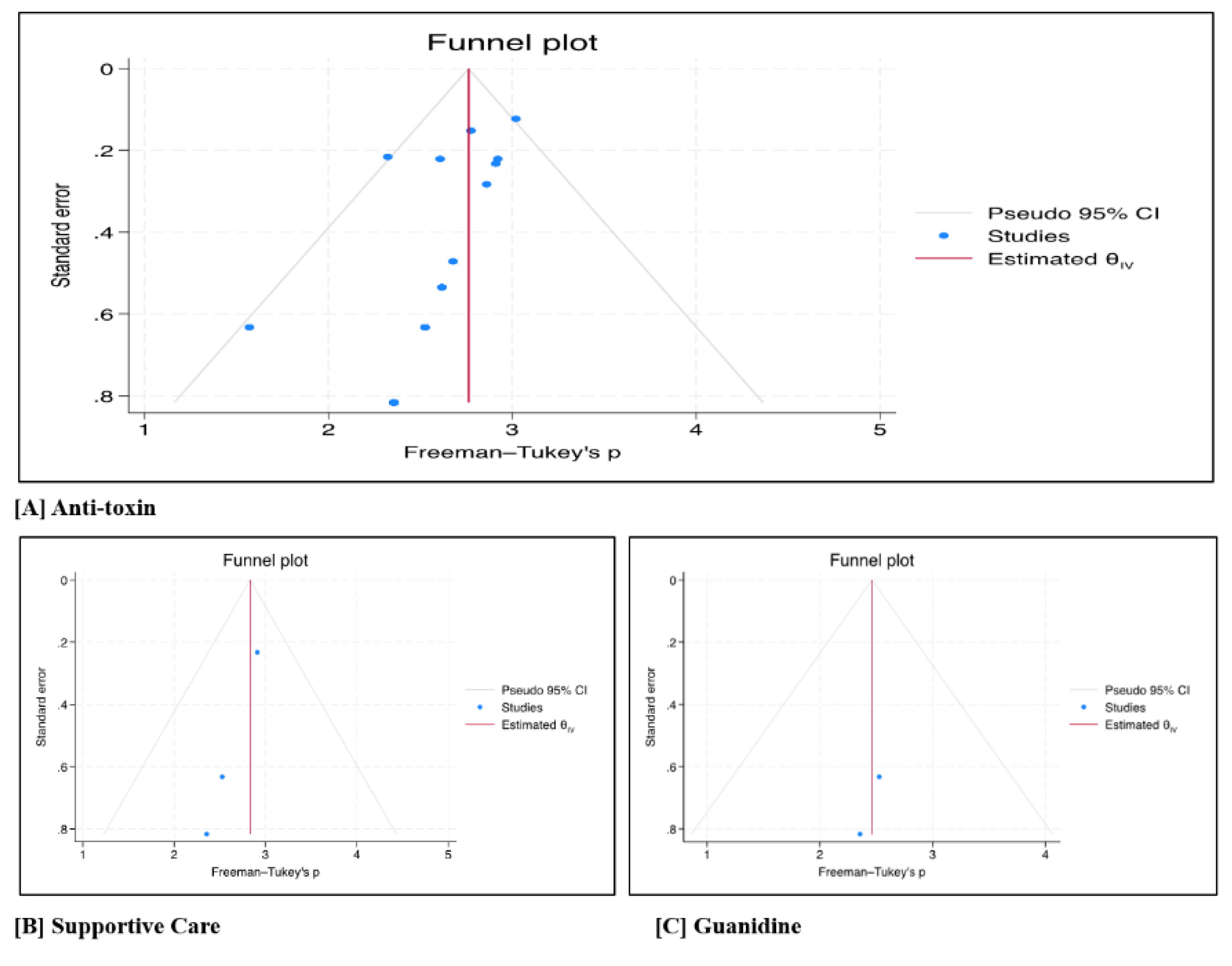

Across 24 studies, 319 patients received anti-toxin. The pooled treatment success with anti-toxin based on individual case reports was highly significant (Freeman-Turkey proportion 2.71, 95% CI 2.55 – 2.87; p <0.001). The back-transformed proportion was 95.3% (95% CI: 91.3% – 97.8%; p<0.001). Between-study heterogeneity was low (τ² = 0.02; I² = 16.38%; p = 0.82). (

Figure 1A). The forest plot and Egger’s test (p = 0.016) indicated potential publication bias, likely due to results with positive results being published (

Figure 2A).

2.2.2. Supportive Care

A total of 21 patients received supportive care across three studies. The pooled treatment success rate for supportive care was also significant, (Freeman–Tukey transformed proportion 2.83, 95% CI 2.42–3.24; p <0.001). After back-transformation, the estimated success proportion was 97.6% (95% CI 91.9–99.3%; p<0.001). No significant heterogeneity was detected among the included studies (τ² = 0.00; I² = 0%; p = 0.71) (

Figure 1B). The forest plot revealed no evidence of publication bias (

Figure 2B).

2.2.3. Guanidine (± Anti-toxin)

Across two studies, three patients received guanidine. The pooled Freeman–Tukey transformed proportion indicating success was also significant 2.46 (95% CI: 1.48–3.44; p <0.001). This corresponds to a back-transformed success rate of 88.9% (95% CI: 46.3–97.1%; p <0.001). The analysis showed no evidence of heterogeneity among studies (τ² = 0.00; I² = 0%; p = 0.87) (

Figure 1C). Additionally, the forest plot revealed minimal publication bias (

Figure 2C).

2.3. Group Comparisons

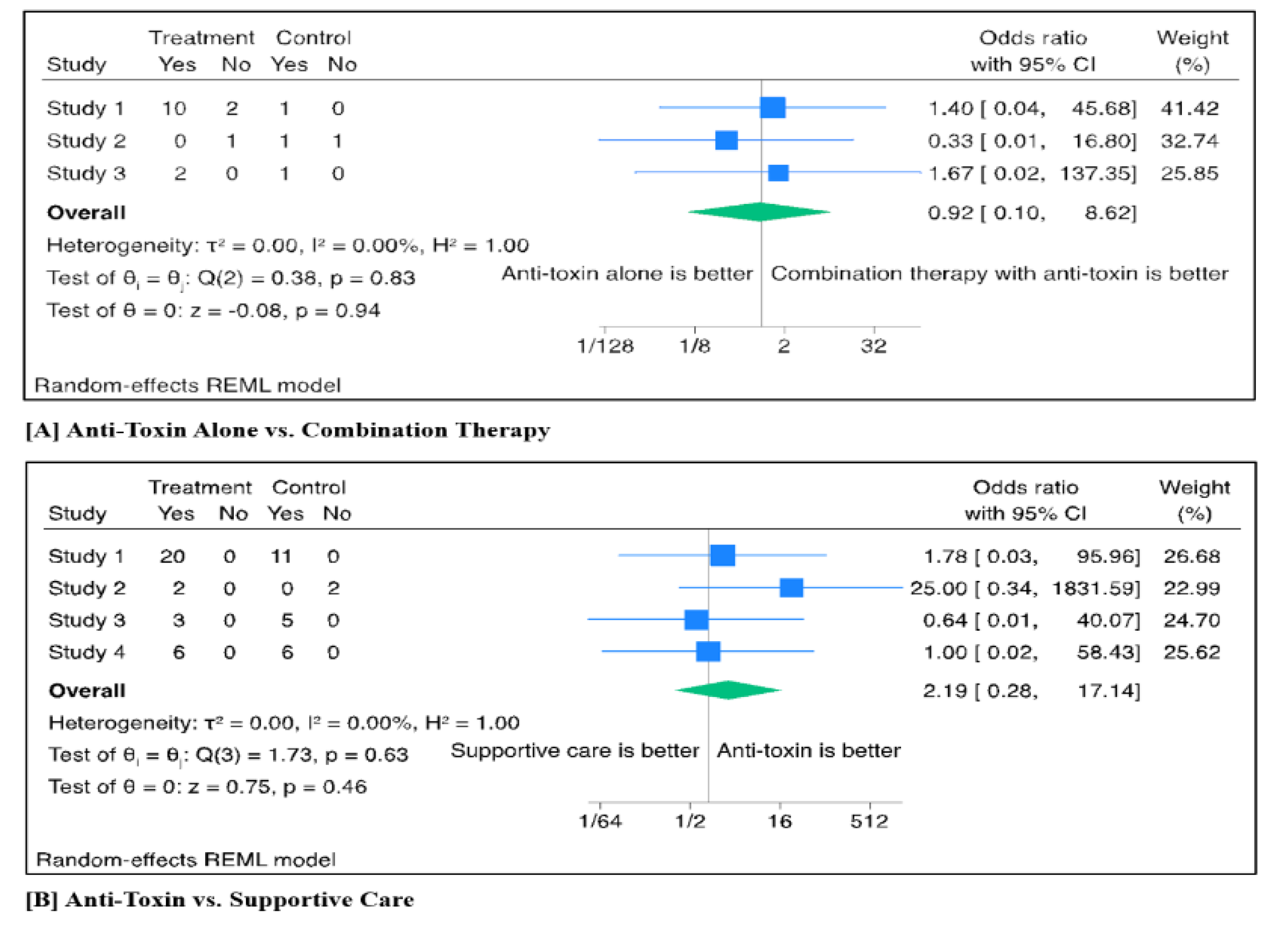

2.3.1. Anti-Toxin Alone vs. Combination Therapy

Three studies directly compared anti-toxin alone vs. combination therapy. A total of 15 patients received anti-toxin alone, while 4 patients received combination therapy (antitoxin and 3,4-DAP). The pooled odds ratio (OR) for treatment success comparing anti-toxin monotherapy to combination therapy was 0.92 (95% CI: 0.10–8.62; p = 0.94). Between-study heterogeneity was not detected (τ² = 0.00; I² = 0%; p = 0.83) (

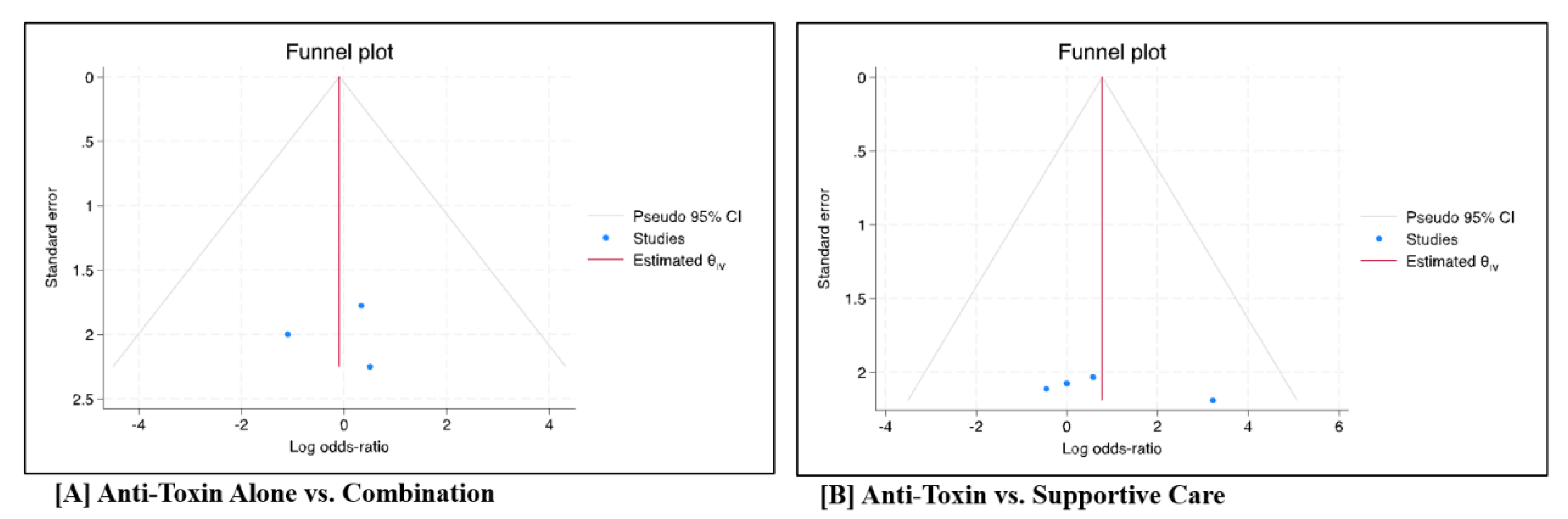

Figure 3A). The forest plot did not suggest the presence of publication bias (p = 0.99) (

Figure 4A).

2.3.2. Anti-Toxin vs. Supportive Care

Four studies compared anti-toxin treatment to supportive care alone. A total of 31 patients received anti-toxin and 24 patients supportive care. The pooled odds ratio (OR) for treatment success was 2.19 (95% CI: 0.28–17.14; p = 0.46), indicating no statistically significant difference between the two interventions. No heterogeneity was detected across the included studies (τ² = 0.00; I² = 0%; p = 0.63) (

Figure 3B). The forest plot did not show evidence of publication bias (

Figure 4B).

3. Discussion

This systematic review and meta-analysis examined the effectiveness of anti-toxin, supportive care, and guanidine in the treatment of foodborne botulism, using pooled data from 38 studies. The results demonstrated significantly high estimated success rates across all three treatment strategies. Anti-toxin, which remains the primary therapeutic option for botulism, showed a pooled treatment success rate of 95.3% (95% CI: 91.3–97.8; p <0.001). This is consistent with prior clinical and epidemiologic reviews demonstrating improved survival with antitoxin therapy [

14,

15]. More recent analyses, such as O’Horo et al., also reported a significant mortality reduction (OR 0.16; 95% CI: 0.09–0.30; p < 0.001), particularly when given early [

13]. Together, these findings affirm antitoxin as the cornerstone of botulism management.

Supportive care alone demonstrated a slightly higher success rate of 97.6% (95% CI: 91.9–99.3; p <0.001), which is consistent with long-standing evidence that modern intensive care has substantially improved outcomes in botulism. Earlier reports described mortality rates exceeding 60%, whereas contemporary data show rates below 10% with access to mechanical ventilation and advanced critical care [

13,

14,

15]. These results confirm that supportive care remains central to survival in botulism, particularly in cases with delayed or limited access to antitoxin.

In our meta-analysis, guanidine was assessed in only two studies, with a pooled success rate of 88.9% (95% CI: 46.3–97.1; p <0.001). The wide confidence interval highlights considerable uncertainty, reflecting the very limited sample size. Previous studies have similarly described only short-lived neuromuscular improvements without sustained recovery [

13,

16,

17,

18]. Guanidine therefore remains an investigational therapy with no proven role in the management of foodborne botulism. All three treatments showed low between-study heterogeneity, though publication bias was detected in anti-toxin case reports, indicating a potential overrepresentation of positive outcomes.

When comparing treatment strategies, no statistically significant differences were observed. Anti-toxin monotherapy and combination therapy showed similar effectiveness, with a pooled odds ratio of 0.92 (95% CI: 0.10–8.62; p = 0.94), and no evidence of heterogeneity or publication bias. These findings are consistent with prior literature, which has generally reported similar outcomes regardless of whether antitoxin was given alone or alongside adjunctive agents [

13,

14,

15]. The consistency of these results suggests that the primary determinant of outcome is timely administration of antitoxin and appropriate supportive care, rather than the addition of adjunctive therapies.

Additionally, anti-toxin demonstrated 2.19 higher odds for treatment success, however this result was not statistically significant (OR 2.19, 95% CI: 0.28–17.14; p = 0.46). While these results suggest comparable outcomes, the wide confidence intervals and limited number of comparative studies restrict the strength of this conclusion. Previous reviews have made similar observations, noting that favorable outcomes in supportive care groups were often linked to timely ICU admission and meticulous respiratory management rather than the absence of therapeutic benefit from antitoxin [

13,

14,

15]. These findings emphasize the potential synergistic effects of antitoxin and supportive care [

4]. The consistency of effect estimates across studies was high, but small sample sizes and methodological differences remain important considerations.

These findings align with previously reported case-based data supporting the role of anti-toxin in clinical recovery from botulism [

1,

4]. However, the high success rate observed with supportive care alone reflects the potential for favorable outcomes when timely and appropriate non-specific management is implemented, even without antitoxin in many cases, as evidenced by studies showing near 100% survival under intensive supportive care [

14]. The limited evidence base and ongoing uncertainty regarding guanidine’s effectiveness suggest that its clinical utility remains unclear, warranting further investigation, particularly in cases with prolonged neuromuscular involvement.

Several limitations should be acknowledged. Most studies included were small retrospective studies with limited information on long-term follow-up. Additionally, there was inconsistent reporting of outcomes, and absence of standardized treatment definitions across studies. The detection of publication bias in the anti-toxin data further suggests that pooled success rates may overestimate actual effectiveness, given that studies with positive results are more likely to be published. Comparative studies were few in number and underpowered, making it difficult to detect potentially meaningful differences between interventions. Finally, our review only included adult patients which limit generalizability to the pediatrics population.

Future research should focus on generating higher-quality evidence through prospective multicenter studies or national registries, particularly in regions where botulism is more frequently reported. Standardized outcome definitions, consistent reporting of patient characteristics, and stratification by disease severity and treatment timing would improve the interpretability and generalizability of findings. While anti-toxin remains the mainstay of treatment, better comparative evidence is needed to define its role relative to supportive care and potential adjunctive therapies. Identifying patient subgroups most likely to benefit from specific interventions could help tailor management strategies and optimize resource use in clinical practice.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Search Strategy

A systematic search was conducted using PubMed and Web of Science from January 2000 to December 2024. Additionally, the reference lists of relevant systematic reviews and meta-analyses were screened to identify further eligible studies through citation tracking. We adopted the PICO (Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcome) process to define our inclusion and exclusion criteria for study selection. We included studies of patients with suspected or confirmed foodborne botulism who received therapy for botulism. The full search strategy, including specific keywords and Boolean operators used in each database, is provided in

Table 1.

We utilized the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) to identify studies of interest. The details of this process and the systematic exclusion of papers are outlined in our PRISMA flow diagram (

Figure 5). All inclusion and exclusion criteria were set a priori. This review was conducted in accordance with the PRISMA 2020 guidelines [

9].

Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) studies on human adults (≥18 years), (2) study types including case reports, case series, retrospective/prospective cohort studies, and RCTs, (3) studies that reported treatment success, prevention of disease progression, or mortality.

Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) animal studies, (2) systematic reviews and meta-analyses, (3) conference abstracts, (4) guidelines, (5) cases of iatrogenic, or wound botulism.

Covidence Systematic Review software (covidence.org) was used to manage the screening and review process. Each title and abstract was reviewed by two independent authors and included for full-text review based on consensus. Similarly, each full text was reviewed independently by two authors, with discrepancies resolved by a third. Data extraction was performed by two authors and reviewed by a third for accuracy.

4.2. Outcomes and Data Extraction

The primary composite of interest was treatment success, defined by the original studies as clinical improvement (including partial or full recovery) in patients diagnosed with foodborne botulism. Raw outcome data such as the number of responders and non-responders were extracted to calculate effect sizes. Studies that lacked sufficient data for this outcome were excluded from pooled analysis. Descriptive characteristics such as sample size, treatment type, age, and sex were extracted using a standardized data collection form.

4.3. Statistical Analysis

To assess our composite outcome, two comparisons were performed. For pooled analyses, treatments were categorized into patients who received antitoxin monotherapy, supportive care, and guanidine (with or without antitoxin) was evaluated. Secondly, group comparisons were made between antitoxin alone versus combination therapy, and antitoxin versus supportive care. These comparisons were based on pooled odds ratios for treatment success and were limited by the small number of studies with comparative designs.

Pooled treatment success rates were calculated using random-effects meta-analysis. For each treatment category (antitoxin, supportive care, guanidine), pooled treatment success proportions with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated using the Freeman–Tukey double arcsine transformation to stabilize variance across studies. For comparisons between treatment categories, pooled odds ratios (ORs) with 95% CIs were also calculated. Back-transformed proportions and ORs were reported for interpretability. Statistical heterogeneity was assessed using τ², the I² statistic, and Cochran’s Q test, with I² values above 50% interpreted as indicating substantial heterogeneity. Publication bias was assessed visually using funnel plots or Egger’s test when ≥ 10 studies were available.

4.4. Risk of Bias of Studies and Quality Assessments of Studies

Risk of bias and study quality were evaluated using validated tools: the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI), checklist for case reports and case series [

10,

11], and the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale for observational studies [

12]. Only studies meeting pre-established quality thresholds were included in the meta-analysis. All data extractions and quality assessments were performed independently by two reviewers, with discrepancies resolved by a third.

5. Conclusions

In this systematic review and meta-analysis, antitoxin, supportive care, and guanidine were all associated with a significant high treatment success rate in foodborne botulism. While antitoxin remains the standard of care, the available evidence does not demonstrate a clear superiority over supportive care or adjunctive therapy. Given the limited existing studies, future collaborative, multicenter research with standardized treatment protocols and outcome measures is essential to define the optimal therapeutic approach and to identify patients most likely to benefit from specific interventions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, MA, RA, RH, RM; methodology, MA, RA, RH, RM; software, MA; validation, RA, RH; formal analysis, MA; investigation, MA; resources, MA; data curation, MA; writing—original draft preparation, RA, RH, RM, AZ; writing—review and editing, RA, RH, RM, AZ; visualization, RA, RH, RM, AZ; supervision, MA, AA, AG, LB, NS; project administration, MA, AA, AG, LB, NS; funding acquisition, MA, AG, LB, NS. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R336), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/

supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the support provided by Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University for administrative. This research was funded by Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R336), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BoNTs |

Botulinum Neurotoxins |

| 3,4-DAP |

3,4-Diaminopyridine |

| CI |

Confidence Interval |

| OR |

Odds Ratio |

| PICO |

Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcome |

| PRISMA |

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| RCTs |

Randomized Controlled Trials |

| JBI |

Joanna Briggs Institute |

| NOS |

Newcastle-Ottawa Scale |

References

- Lonati, D.; Rossetti, E.; Petrolini, V.M.; Giampreti, A.; Vecchio, S.; Duiella, M.; et al. Foodborne botulism: Clinical diagnosis and medical treatment. Toxins (Basel) 2020, 12, 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peck, M.W.; van Vliet, A.H.M.; Stringer, S.C. The epidemiology of foodborne botulism outbreaks: A systematic review. J. Food Prot. 2018, 81, 1114–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health (KSA). Guidelines for Foodborne Botulism (Clostridium botulinum), Version 2.1; Ministry of Health: Riyadh, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, A.K.; Sobel, J.; Chatham-Stephens, K.; Luquez, C.; et al. Clinical guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of botulism, 2021. MMWR Recomm. Rep. 2021, 70, RR-2, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeffery, I.A.; Nguyen, A.D.; Karim, S. Botulism. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025; updated 25 November 2024. Bookshelf ID: NBK459273. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vazquez-Cintron, M.C.; Bradford, A.B.; Beske, P.H.; Hoffman, K.M.; Machamer, J.B.; Eisen, M.R.; et al. Symptomatic treatment of botulism with a clinically approved small molecule reverses respiratory depression in murine models. J. Clin. Investif. 2022, 132, e157909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Zuayr, S.N.; Abdelrahman, A.K.; Almutairi, A.S.; et al. Comprehensive field investigation of a large botulism outbreak, Saudi Arabia, 2024. J. Infect. Public Health 2025, 18, 102702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Honeyman, D.; Notaras, A.; Heslop, D.J.; MacIntyre, C.R. Botulism outbreak in Russia connected to ready-made salads. Glob. Biosecurity 2024. [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Joanna Briggs Institute. Checklist for Case Reports; The Joanna Briggs Institute: Adelaide, Australia, 2017; Available online: https://jbi.global/critical-appraisal-tools.

- Joanna Briggs Institute. Checklist for Case Series; The Joanna Briggs Institute: Adelaide, Australia, 2017; Available online: https://jbi.global/critical-appraisal-tools.

- Wells, G.A.; Shea, B.; O’Connell, D.; Peterson, J.; Welch, V.; Losos, M.; Tugwell, P. The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) for Assessing the Quality of Nonrandomised Studies in Meta-Analyses; Ottawa Hospital Research Institute: Ottawa, Canada, 2014; Available online: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp.

- O’Horo, J.C.; Harper, E.P.; El Rafei, A.; Ali, R.; Desimone, D.C.; Sakusic, A.; Abu Saleh, O.M.; Marcelin, J.R.; Tan, E.M.; Rao, A.K.; et al. Efficacy of antitoxin therapy in treating patients with foodborne botulism: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cases, 1923–2016. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2017, 66 (Suppl. 1), S43–S56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sobel, J. Botulism. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2005, 41, 1167–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shapiro, R.L.; Hatheway, C.; Swerdlow, D.L. Botulism in the United States: A clinical and epidemiologic review. Ann. Intern. Med. 1998, 129, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cherington, M.; Ryan, D.W. Treatment of botulism with guanidine: Early neurophysiologic studies. N. Engl. J. Med. 1970, 282, 195–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puggiari, M.; Cherington, M. Botulism and guanidine: Ten years later. JAMA 1978, 240, 2276–2277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaplan, J.E.; Davis, L.E.; Narayan, V.; et al. Botulism, type A, and treatment with guanidine. Ann. Neurol. 1979, 6, 69–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).