1. Introduction

“

We have an urgent global brain health crisis… No country has a handle on this escalating challenge” [

1]. With those stark words, the June 2025 G7 Summit of the world’s leading economies presented the sobering reality that even the most technologically advanced nations, equipped with cutting-edge science, medical technology, advanced pharmaceuticals, and artificial intelligence, remain powerless in the face of an accelerating neurological epidemic. No country, regardless of wealth or scientific expertise, has succeeded in containing this brain health crisis [

1]. The alarming G7 declaration echoed the World Health Organization (WHO) warning in 2024 that neurological disorders now affect more than one in three people, over three billion individuals, and have become the leading cause of disability worldwide [

2], reflecting the lack of treatments capable of restoring lost neurological function.

If left unaddressed, the trajectory is unmistakable. In the absence of therapies capable of reversing disease, neurological diseases will not only disable but ultimately kill, reducing human potential on an unprecedented scale. This staggering loss of human life is no longer theoretical as the WHO has issued a grave warning that neurological disorders are projected to become the second leading cause of death worldwide [

3], confirming that today’s crisis of neurological disability is rapidly escalating into a global mass mortality event with catastrophic humanitarian and socioeconomic consequences.

Among the most feared and devastating manifestations of neurological diseases stands Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS), a progressive fatal neurodegenerative disorder characterized by paralysis [

4,

5], and often dementia [

6,

7], that strikes without warning and strips away the most basic human abilities such as moving, speaking, swallowing and breathing. ALS gained widespread recognition following the death of New York Yankees Hall of Fame baseball star Lou Gehrig at age 37, demonstrating that neither youth, peak physical fitness, nor elite athletic performance confers protection against the disease’s indiscriminate nature [

8,

9].

Long considered untreatable, ALS follows a brutal course toward paralysis, respiratory failure, and death, devastating lives and revealing the failure of global scientific research to develop a disease reversal treatment for brain disorders. Confronting this challenge demands not only new treatments, but an entirely new way of thinking. And yet, the most transformative idea may not be new at all, but one discovered a century ago in the form of malarial fever therapy effectively restoring neurological function in dementia paralytica, which was honored with the Nobel Prize in Medicine [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18], suggesting that the path to solving the global brain health crisis was not only foreseen through Nobel wisdom but scientifically validated; awaiting not invention, but rediscovery, and rising again 100 years later not as memory, but as method.

The convergence of a Nobel Prize–recognized treatment and advanced digital engineering has unlocked a novel approach, reviving a long-overlooked path that may change the course of the global brain health crisis with a scientifically grounded method that herein has achieved neurological, molecular, and electrophysiological reversal of ALS, opening the path to treating a wide range of neurodegenerative diseases previously deemed irreversible. This path for effectively treating neurological disorders was made possible by the approval of a computerized platform by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), publicly announced by ASUS Computer Company [

19], which enabled the development of Computerized Brain-guided Intelligent Thermofebrile Therapy (CBIT²) that digitally reengineers the 1927 Nobel Prize–winning malarial fever therapy that once achieved the unthinkable by reversing paralysis and dementia in patients neurologically condemned to death [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18].

To counteract ongoing neuronal loss and progressive incapacitation in a 56-year-old patient with rapidly advancing ALS, we use CBIT², a digitally controlled, fully noninvasive, intelligent, noninfectious, fever-based therapy with no adverse effects designed to regulate the brain thermoregulatory response and cerebral molecular heat shock repair systems. Using digital precision and real-time thermoregulatory feedback, CBIT² was employed to induce heat shock protein (HSP) in the brain, specifically targeting motor neurons, aiming to counteract a biomarker-confirmed trajectory of rapid disease progression and impending demise in this ALS patient while reversing neurodegeneration and overcoming the well-documented limitations of existing ALS therapies. Current ALS treatments offer only marginal delays in functional decline and brief extensions of life by about two to three months, while failing to arrest or reverse neuronal loss, progressive incapacitation, and death [

20,

21,

22,

23].

This report emerges in the context of this mounting global neurological crisis [

1,

2]. Paradoxically, it is ALS, long considered an intractable and fatal neurodegenerative disorder, that may offer a path towards a solution to the global neurological emergency. Given ALS’s uniquely high threshold for inducing HSPs in motor neurons [

24], the remarkable combination of neurological, molecular, and electrophysiological reversal observed in this ALS patient suggests broader therapeutic potential that extends well beyond a single neurological disease as neurodegeneration share common features of progressive neuronal loss driven by pathological protein aggregation [

25,

26]. Among these disorders, ALS may serve as the ultimate proving ground; if reversal is achievable in this most treatment-resistant condition [

27], then applying similar therapeutic approach to less refractory neurological diseases as Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, ataxia and related pathologies may not only be plausible, but imminently within reach. Thus, ALS shifts from a symbol of irreversible decline and death to a therapeutic gateway, offering a path forward in the broader fight against neurological disorders that increasingly disrupt global health and economic stability.

Although this case moves from infection to invention, it is not merely a testament to technological progress, but in fact it reclaims a therapeutic truth first revealed through Nobel-winning malarial fever, which is the only treatment in history to cure dementia paralytica and empty the asylums once filled with the terminally afflicted with this fatal neuropsychiatric disorder [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. This report opens the door ethically, scientifically, and humanely to a complementary path that includes infection as intervention, fever as medicine, especially if it offers a means to restore proteostasis and prevent the collapse of neurological health for billions around the world.

In this context, effective HSP induction shown herein after computerized fever-based therapy, led to the neurological, molecular, and electrophysiological reversal of ALS, providing direct evidence that correcting misfolded protein dysfunction can reverse disease. This therapeutic rational becomes even more compelling when considering that the molecular basis of neurodegeneration is impaired HSP function, leading to misfolded protein accumulation and neuronal damage, which leads to disease progression [

28,

29,

30]. Furthermore, increased HSP70 reduces protein aggregation and supports motor neuron survival [

31,

32], while HSP27 and HSP90 influence neuroprotection or disease progression based on their expression levels [

33,

34]. Moreover, HSP-based pharmacological interventions have been considered for Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, Huntington’s, and ALS [

35,

36,

37,

38,

39], aiming to correct chaperone dysfunction and restore proteostasis, and potentially slow ALS progression [

40]. Recent attempts to upregulate HSPs using agents like arimoclomol showed increased HSP expression in animal models but failed to improve clinical outcomes and raised safety concerns at higher doses [

20]. Nonetheless, HSP activation may hold therapeutic and neuroprotective potential, as detailed in a recent review by Smadja and Abreu [

26] and emerging evidence suggests that heat acclimation and passive heat therapy may induce HSP expression and reduce the risk of Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease [

41]. However, although the relationship between hyperthermia and HSP activation is established [

26], thermal treatment has never been applied to ALS, and its use to counter, much less reverse, the associated paralysis and cognitive decline, has not yet been explored.

We herein demonstrate the therapeutic effects of CBIT² in ALS, with evidence of disease reversal and restoration of motor neuron function, validated by objective neuromuscular assessments, normalization of molecular biomarkers, and upregulation of heat shock protein expression. Strikingly, electrophysiological studies revealed the complete disappearance of denervation, the defining hallmark of motor neuron death in ALS, along with the resolution of fasciculations, both clearly present before our treatment but absent following CBIT². This electrophysiological reversal of ALS following CBIT² was independently validated at two of the foremost university-based neurology centers in the United States (for electromyography report see

Appendix A), providing rigorous, objective confirmation of motor neuron restoration, offering objective evidence for the reversal of neurodegeneration in a condition long considered irreversible. What was once deemed impossible in ALS occurred following CBIT², as electromyography demonstrated the complete disappearance of denervation, providing objective electrophysiological evidence for the absence of motor neuron degeneration.

As alluded to above, the protocol used by CBIT² is derived from a landmark moment in medical history, when Austrian psychiatrist Dr. Julius Wagner-Jauregg was awarded the Nobel Prize in Medicine for his pioneering use of high fever induced by malarial infection to treat dementia paralytica, a disorder marked by fatal paralysis and profound cognitive decline representing the terminal stage of neurosyphilis [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. As highlighted in a review, the impact of malarial fever therapy was dramatic: “

Death, in most cases, was welcomed as the final respite from the horrifying symptoms of neurosyphilis... malarial treatment played a role in the emptying of the asylums and provided a viable alternative for a previously hopeless disease” [

11].

Dr. Wagner-Jauregg initially used erysipelas and tuberculin to induce therapeutic fever with limited success and severe side effects. His breakthrough came with the use of malarial fever, which produced remarkable neurological recovery in patients with dementia paralytica, ultimately establishing the treatment as a curative therapy for otherwise intractable neuropsychiatric symptoms Prize [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. At the time, the therapeutic benefit was largely attributed to fever’s presumed ability to eliminate

Treponema pallidum, the pathogen causing syphilis, rather than to any reversal of brain disease, which is the innovative therapeutic paradigm newly proposed here. As further evidence supporting bacterial eradication as the therapeutic rationale a century ago, some physicians advocated initiating malarial fever therapy immediately following a positive Wassermann test, even before the onset of dementia paralytica, as a preventive intervention against neurosyphilis [

11]. Despite its remarkable success in Europe and across the world, malarial fever therapy faded into obscurity with the advent of antibiotics (to prevent progression of syphilis to its tertiary stage) and ethical concerns about potential serious risks due to malarial infection including migration of the parasite to the brain causing cerebral malaria, which is commonly fatal [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18].

Nearly a century later, M. Marc Abreu, M.D. (primary author) critically reexamined Wagner-Jauregg’s original data and uncovered a striking and long-overlooked possibility that malarial fever therapy may have reversed not only the underlying syphilitic infection but also the structural brain injury that persisted even after microbial eradication. Abreu observed that the progressive paralysis seen in dementia paralytica closely resembles the motor deterioration characteristic of ALS. Remarkably, these two seemingly unrelated diseases are united by a shared molecular signature in which both are driven by the pathological accumulation of misfolded TDP-43, the defining biomarker of ALS [

42], which astonishingly also aggregates in neurosyphilis [

43]. This unexpected molecular signature spanning a century offers compelling scientific support that the curative principles behind the 1927 Nobel Prize therapy may hold similarly curative promise for ALS today.

Molecular evidence implicating misfolded TDP-43 as a central driver of neurodegeneration, together with clinical reports showing that malarial fever therapy from tertian malaria, with fevers reaching up to 41.5 °C, reversed neuronal damage and enabled full neurological recovery with reintegration into daily life [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18], demonstrated that neurodegeneration can, in fact, be reversed. Multiple reports from around the world describe patients once bound by paralysis and seemingly condemned to death, who, after undergoing malarial fever therapy, regained speech, recovered movement, returned to work, and experienced what can only be described as a neurological rebirth [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. Building on these extraordinary outcomes achieved by Nobel laureate Dr. Wagner-Jauregg, and recognizing the need for a safe, effective, and noninfectious alternative, Abreu developed a computerized, digitally controlled, intelligent, hypothalamic-guided platform designed to replicate the high fever patterns of malarial infection to target the core molecular dysfunction of misfolded protein, offering a novel pathway to restore what has long been considered irreversible neurodegeneration.

The safe titration of brain temperature and the generation of computerized cyclical thermal patterns under hypothalamic control were made possible by Abreu’s discovery at Yale University School of Medicine of a biological thermal waveguide between the brain and eyelid, known as the Brain-Eyelid Thermoregulatory Tunnel (BTT), initially described as the brain temperature tunnel [

44,

45,

46]. The discovery of the BTT led to the development of a computerized platform and sensor system approved by the U.S. FDA which laid the technological foundation for CBIT² which includes noninvasive measurement of brain temperature and real-time, brain-guided, intelligent induction of the heat shock response (Abreu BTT 700 Computer System, Heat Shock Induction 700 Module, Brain Tunnelgenix Technologies Corp., Aventura, Florida).

Agreement with body core temperature, except for specificity to the brain during brain–core discordance, was demonstrated in Yale-led studies by Abreu and Silverman (co-author) in collaboration with other institutions [

46] as well as in a multi-institutional study led by Nova Southeastern University, in Florida, which cited the Yale findings in an article assessing the impact of carotid temperature modifications on brain temperature and yawning [

47].

Misfolded protein pathology common to both neurosyphilis [

43] and ALS [

42], together with global clinical evidence of fever-induced neurological recovery [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18], provided the foundation for transforming a century-old, Nobel-recognized therapy into CBIT² as a computerized, noninvasive, hypothalamic-targeted, AI-enhanced platform that titrates brain temperature to reverse neurodegeneration. Consistent with the rhythmic nature of malarial fever therapy, Abreu hypothesized that such patterned thermal input triggers repeated activation of the heat shock response, upregulating HSPs that support neuronal protection and recovery [

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

40], and further proposed that cerebral HSP induction may respond more effectively to dynamic thermal profiles across distinct brain regions [

48].

Noninvasive brain temperature and thermodynamics monitoring were critical to both the safety and efficacy of CBIT², allowing real-time assessment of cerebral thermodynamics, precise titration of the thermofebrile response based on hypothalamic signals, prevention of hyperthermic brain injury, and direct delivery of therapeutic heat to the brain. These advantages are especially critical in ALS, where motor neurons require higher thermal threshold to induce heat shock response, including robust expression of HSP70 [

24]. Guided by the BTT, CBIT² delivers precise, cyclical high-heat exposure to activate HSPs within thermally resistant motor neurons [

24], replicating the therapeutic mechanism of malarial fever in a computerized, infection-free platform.

Guided by continuous, minute-by-minute thermal measurements to guide real-time adjustments, the protocol ensures precise brain modulation and patient safety, bringing to life Lord Kelvin’s timeless words

“You cannot manage what you cannot measure” [

49]. We further apply Kelvin’s tenet to this case through quantitative documentation of clinical improvement, including enhanced motor function, reductions in pathological serum biomarkers, measurable increases in HSP expression, and numerical evidence of electrophysiological restoration, in addition to written reports from the patient and her physical therapist. Complementing this approach, a defining and unique strength of this case report is the integration of pre- and post-treatment video documentation, which provided direct visual validation of neurological recovery, corroborating findings from electromyography (EMG) and blood biomarker normalization. This convergence of objective clinical, molecular, and electrophysiological data with real-time video documentation not only confirmed individual patient outcomes but also reinforced the broader scientific rationale underlying CBIT², based on the long-overlooked therapeutic principles of malarial fever therapy.

The forgotten, more aptly both unrecognized and unappreciated, link between the 1927 Nobel Prize discovery and the treatment of neurodegenerative disease laid the foundation for a safe, infection-free, computer-controlled hub of therapeutic intelligence, capable of dynamically modulating and personalizing therapy in real time. By digitally reengineering the century-old, Nobel-recognized fever rhythms that once reversed disease and restored function in patients with paralysis and dementia, CBIT² delivers precise, brain-guided replication of the cyclical thermal dynamics of malarial infection to treat neurodegeneration. CBIT² seeks to reverse what has long been considered irreversible, now demonstrated by EMG, where denervation once signaled motor neuron death and renewed electrical activity now indicates restored neuronal function following brain-guided programmed fever therapy.

Thus, against this escalating global brain health crisis highlighted by the G7 Summit and WHO [

1,

2], reawakened Nobel wisdom, without which the computerized fever therapy shown here could never have been conceived, now opens a therapeutic path where none was thought to exist, offering what may represent a novel intervention to defend the human brain in the age of intelligent machines.

From the 1927 Nobel Prize–recognized malarial fever therapy, once used to reverse paralysis and dementia in neurosyphilis, emerges a modern reengineering grounded in the understanding of misfolded protein pathology and the molecular biology of the heat shock response. Through AI-enhanced brain thermodynamics, the rhythmic thermal patterns once generated unpredictably by infection can now be delivered with precision, safety, and hypothalamic targeting, transforming an abandoned historical intervention into a controllable, noninvasive neurotherapeutic platform.

On this basis, the present case report, which documents neurological, molecular, and electrophysiological reversal of ALS following CBIT², provides clinical evidence that the core therapeutic mechanism behind malarial fever therapy is plausibly the induction of the heat shock response, a process that can now be noninvasively reengineered, precisely targeted, and dynamically controlled through AI-enhanced brain thermodynamics. Enabled by U.S. FDA approval of our computerized platform, CBIT² builds on this technological foundation to transform the century-old, Nobel-recognized fever therapy into a modern, infection-free, brain-guided intervention capable of precise thermoregulatory targeting. Through the convergence of Nobel-recognized therapy and advanced digital engineering, a therapeutic approach now emerges to confront what was once considered untreatable, offering a potential pathway to alter the course of neurological decline and change the trajectory of brain disability and death on a global scale.

Case Report

A 56-year-old female patient with a confirmed diagnosis of ALS was referred to the BTT Medical Institute in Florida following a progressive and marked decline in motor function. On October 25, 2024, she had been diagnosed with ALS at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, which is recognized as the leading neurology hospital in the United States [

50].

Her past medical history was otherwise unremarkable, aside from a cervical fusion at the C3–C5 vertebrae without residual sequelae. Family history was negative for dementia, neurological disorders, or muscle disease. She denied smoking or recreational drug use and reported consuming socially approximately one alcoholic drink per week. In May 2019, she developed mild stiffness and spasticity in both legs following a fall, which led to recurrent falls. Initially suspected of having Stiff Person Syndrome, she was treated with intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg) and diazepam, but her symptoms failed to improve and progressively worsened. In September 2023, she developed dysphagia and dysarthria worsening in the evenings despite a reduction in her diazepam dosage.

The cornerstone for the diagnosis of ALS is electromyography (EMG) showing denervation. EMG was performed at the Mayo Clinic on October 25th, 2024 and demonstrated active denervation and reinnervation in the lumbosacral segment with chronic denervation in the right hand in addition to fasciculations demonstrating lower motor neuron changes. The Mayo Clinic report further documented progressive weakness of hand grip, more pronounced on the right side, along with progressive spasticity of the lower extremities and worsening gait, now requiring a walker after previously using a cane. The patient also presented with dysarthria, episodes of coughing when drinking liquids, and nasal regurgitation. On examination, gait was markedly spastic; she was unable to walk on heels or toes and could not rise from a chair. Additional findings included a positive Hoffmann sign, weakness of the right arm and hand, and weakness involving the knee, ankle, and toes. Taken together, these findings confirmed combined upper and lower motor neuron involvement, characteristic of ALS. The Mayo Clinic neurologist stressed that “progressive lower motor neuron denervation is unfortunately inevitable” and that “The median patient survival is 3–5 years from symptom onset considering all ALS patients, but some patients have a more rapid or slowly progressive curve.” The patient was enrolled in the ALS Clinic and prescribed FDA–approved drugs for ALS, namely riluzole and edaravone.

MRI demonstrated susceptibility-weighted imaging (SWI) changes in the motor band together with corticospinal tract (CST) hyperintensity on FLAIR (fluid-attenuated inversion recovery) in the pons and cerebellar peduncles. The combined presence of the motor band sign on SWI and corticospinal tract hyperintensity on FLAIR has been reported to carry high specificity for ALS, thereby providing additional radiologic corroboration of the diagnosis of ALS. A series of tests and evaluations were performed to rule out alternative diagnoses, including Lyme serology and a long-chain fatty acid panel, which returned normal, and testing for myasthenia gravis, M protein, creatine kinase (CK), hemoglobin A1c, and thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), all of which were negative.

The patient’s diagnostic and therapeutic journey spanned two of the most prestigious neurology institutions in the United States. She was initially diagnosed and treated at the Mayo Clinic and later at Northwestern University, a nationally ranked neurology center in Illinois, where she resides. Together, these centers represent the pinnacle of neurological expertise, yet her rapidly declining course underscores the reality that even care delivered at the most elite institutions, by some of the foremost neurologists in the field, remains constrained by the limited efficacy of current ALS therapies. Her neurological function continued to deteriorate despite treatment with two FDA-approved therapies for ALS, which are known to provide only modest clinical benefit. This trajectory highlights not only the limitations of standard pharmacologic options but also the urgent need for alternative therapeutic strategies capable of reversing disease and restoring lost neurological function.

A neurological examination performed at Northwestern on December 4, 2024 documented mixed dysarthria and a spastic gait. Cranial nerve examination revealed a weak cheek puff and slow tongue movement. Motor examination revealed reduced motor strength and spasticity, predominantly in the right leg as well as positive Romberg, Hoffman and Tromner’s signs (more pronounced on the right). The patient had limited range of motion, but no bony abnormalities, contractures, malalignment, or tenderness.

The patient learned about brain-guided programmed fever therapy from an acquaintance who had previously been successfully treated at the BTT Medical Institute. A pre-treatment examination performed at the BTT Medical Institute in Florida on January 28, 2025, confirmed findings consistent with prior evaluations at the Mayo Clinic and Northwestern University, detailed here. However, by this time her gait had become irregular, wide-based, and waddling, with severely limited ambulation requiring the use of a walker. Coordination and cerebellar testing revealed an intact finger-to-nose performance without tremors. Her current medications included diazepam 5 mg once daily by mouth, Sertraline 50 mg once daily by mouth, dextromethorphan/quinidine 10 mg twice daily by mouth, riluzole 50 mg twice daily by mouth, and edaravone 5 mL once daily by mouth. Ongoing and supportive management consisted of physical therapy, speech therapy, and symptomatic treatment aimed at managing spasticity, dysarthria, and dysphagia.

We sought to determine whether Computerized Brain-Guided Intelligent Thermofebrile Therapy (CBIT²), delivered through an FDA-approved computerized platform that includes a Thermofebrile Rhythm Engineering Protocol, could acutely halt, or even reverse, the ongoing neurodegeneration and motor neuron loss due to ALS present in this patient. This application of CBIT² in a patient with a neurodegenerative disorder was guided by the hypothesis that it could reproduce the curative effects once achieved with malarial fever therapy, grounded in the shared pathological hallmark of TDP-43 proteinopathy present in both ALS and dementia paralytica (neurosyphilis), which is the disease effectively treated by Wagner-Jauregg’s Nobel Prize–winning discovery.

To rigorously evaluate this potential, a comprehensive battery of assessments was conducted, including quantitative neuromuscular testing tailored to the patient’s symptom profile, high-resolution gait and balance analysis, respiratory function testing, oral motor strength evaluation, and upper and lower limb strength measurement. Serial blood biomarkers were monitored to assess disease burden and therapeutic response, including neurofilament light chain (NfL), homocysteine, interleukin-10 (IL-10), and heat shock protein (HSP) expression. Complementing these molecular assessments, electrophysiological studies including pre- and post-treatment EMGs spaced five months apart were conducted by independent university-based services to evaluate changes in motor unit integrity and neuromuscular signaling. The EMG protocol was designed to detect both the silence that accompanies motor neuron death and the reemergence of electrical activity that could signify reinnervation. In this way, the electrophysiological data provided a real-time window into the absence of denervation following CBIT² and neuronal restoration, engraved into the muscles themselves. Together, this multidimensional evaluation including neuromuscular assessment, serial biomarkers, and electrophysiological studies enabled a robust appraisal of both functional and structural recovery as well as molecular response to this novel, noninvasive, computerized intelligent thermofebrile neurotherapeutic intervention.

4. Discussion

This case report presents the first documented reversal of ALS, a disease long regarded as irreversible and uniformly fatal, achieved through the first application of therapeutic fever to ALS, resulting in neurological, molecular, and electrophysiological reversal of ALS that directly challenges the entrenched view of inexorable progression in ALS. These findings provide historic proof-of-principle that ALS pathology is, in fact, reversible. While this outcome marks an unprecedented turning point in our understanding of ALS, its broader significance must now be tested through rigorous, large-scale clinical trials to confirm reproducibility, durability, and therapeutic potential across the spectrum of misfolding protein disorders including other neurodegenerative diseases.

In 1917, Wagner-Jauregg’s case report showed that deliberate fever induction could reverse dementia paralytica, the first proof that fever held curative power for neuropsychiatric disease [

15], becoming a breakthrough which was later confirmed by trials and honored with the 1927 Nobel Prize. More than a century later, in that same lineage, the present case report demonstrates that fever, now digitally reengineered and brain-guided through CBIT², can safely restore brain function in ALS, a disease long considered irreversible and fatal.

The BTT-based intelligent programmed fever treatment (formally termed CBIT²) resulted in complete reversal of ALS and restoration of lost brain function. This unprecedented outcome stands in sharp contrast to prevailing expectations for ALS. The Mayo Clinic report, for example, had emphasized the inexorable course of the disease, stressing that “progressive lower motor neuron denervation is unfortunately inevitable” and communicated to the patient a life expectancy of only three to five years. This statement underscored the long-established scientific consensus, grounded in decades of rigorous research, that once degeneration begins in ALS there is progressive motor neuron loss, an irreversible decline, and life expectancy limited to only few years. For generations, this has defined ALS as a death sentence, with no path back once denervation sets in. Yet in this case, that inevitability was not only averted but replaced by documented electrophysiological evidence of reversal of denervation, with elimination of fibrillation and fasciculation, demonstrated by irrefutable objective testing with EMG, the gold standard for ALS diagnosis. What science long judged as inexorable decline is here replaced by recovery, proving that the presumed irreversibility of ALS can, in fact, be undone, echoing the Nobel Prize–validated precedent of fever therapy, which a century ago restored brain function in dementia paralytica.

After her initial diagnosis at the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota, the patient was followed in her hometown at Northwestern University, ranked among the leading neurology centers in the United States, where the ALS diagnosis was independently confirmed and she was thus maintained on the FDA-approved drugs for treating ALS riluzole and edaravone. Despite expert care at both of these prestigious centers, Mayo Clinic and Northwestern University, her neurological function declined relentlessly, in keeping with the scientifically established expectation of inevitable progression and death in ALS.

A turning point came when an acquaintance, who had himself been successfully treated at the BTT Medical Institute, urged the patient to seek care in Florida. Following treatment with CBIT² by Dr. M. Marc Abreu at the BTT Medical Institute, she returned to Northwestern for follow-up, where the neurologist who performed the EMG was confronted with the extraordinary reality that the study demonstrated elimination of denervation and fasciculations, providing irrefutable electrophysiological evidence of cessation of motor neuron death and supporting the conclusion of disease reversal. Considering this unprecedented finding, the Northwestern neurologist discontinued all the patient’s ALS medications which is an outcome virtually unimaginable for a disease long regarded as irreversible and consistently fatal. Both riluzole and edaravone, prescribed exclusively for ALS, were stopped, reflecting the extraordinary fact that the patient no longer met diagnostic criteria for ALS underscoring the plausibility of cure through programmed fever therapy. That grim prognosis for ALS is no longer a reality: instead of being shackled to a death sentence, the patient here now faces life in abundance, free of ALS, able to dance and even play golf and pickleball, as seen in the videos provided in this report.

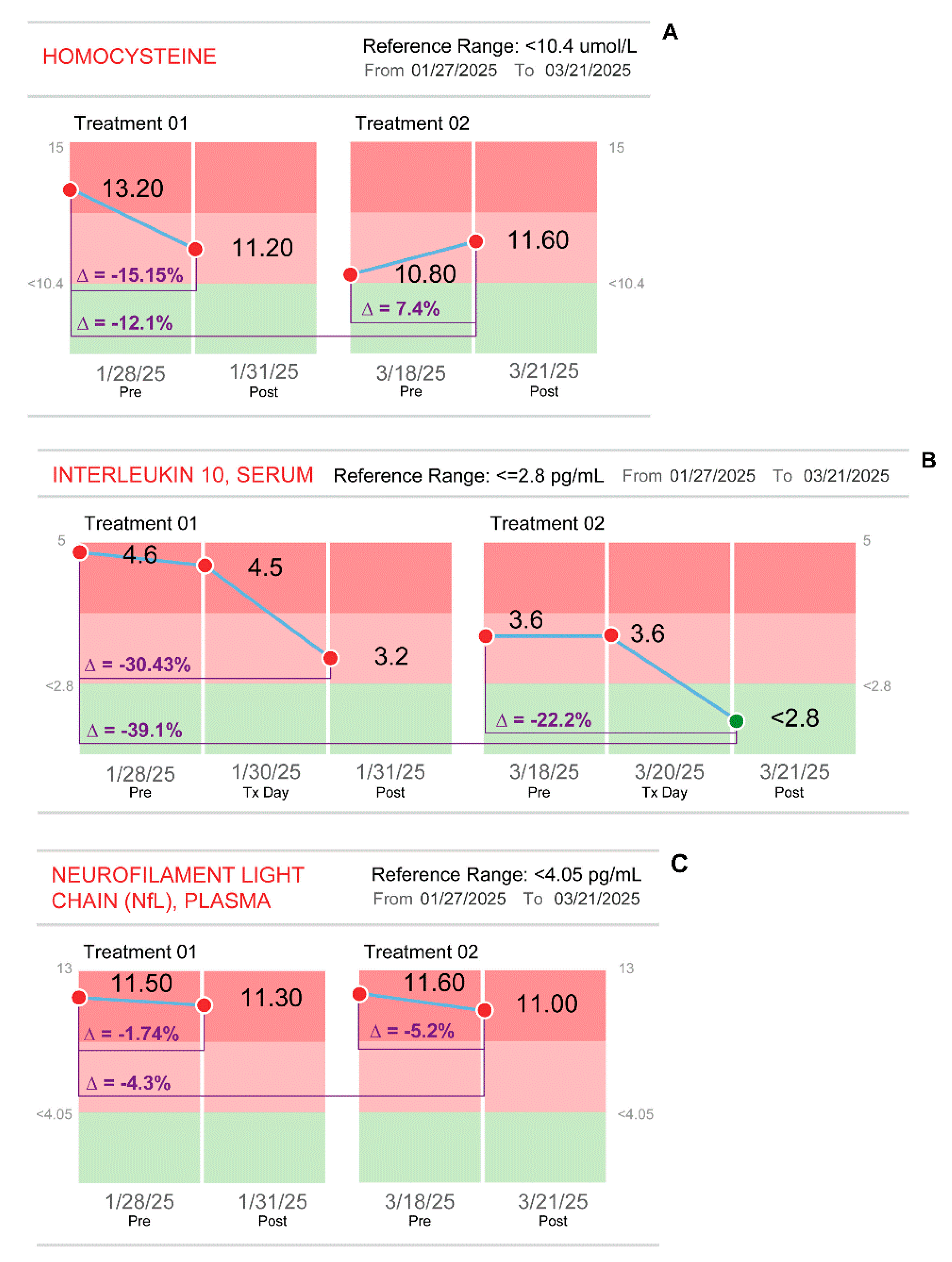

In addition to EMG demonstrating that ALS was no longer present, biomarkers shifted toward recovery, with reductions in neurofilament light chain and homocysteine, normalization of IL-10, a cytokine whose persistent elevation as seen in this patient correlates with increased mortality, besides a surge in HSP70 expression. Clinically, she advanced from walker dependence to restored gait, safe swallowing, strengthened respiration, improved speech, and fully normalized cognition. Most strikingly, she regained the ability to perform complex motor tasks once thought irretrievable, such as swimming, walking unaided onto a golf green and sinking consecutive putts as well as returning to active sports.

Findings herein revealed restoration of motor neuron function following BTT-based intelligent programmed fever treatment, which is an outcome that directly contradicts the presumed irreversibility of motor neuron loss. This transformation, once unimaginable, echoes a truth first acknowledged nearly a century ago, when the Nobel Prize Committee recognized malarial fever therapy as the first demonstration of fever’s curative power for neuropsychiatric disease. The exceptional ALS reversal achieved here honors the vision, extending it into the modern era through BTT-based brain-guided programmed fever therapy. Nearly a century later, that foundation identified by the Nobel Prize has been extended and reengineered through CBIT², transforming a once-forgotten treatment into a modern, infection-free, computerized intelligent brain-guided fever therapy that culminated in full reversal of ALS, which resulted in the discontinuation of all ALS-specific pharmacologic treatment.

The febrile response was digitally induced using CBIT², a novel, artificial intelligence-enhanced treatment that delivers therapeutic fever safely and precisely through synchronized thermoregulatory modulation using an FDA-approved computerized platform [

19]. CBIT² digitally reengineers the curative principle behind the 1927 Nobel Prize–winning malarial fever therapy into a brain-guided, programmable intelligent treatment. This fully noninvasive and unique procedure proved exceptionally safe, with no adverse effects or complications observed during treatment, within the critical 48-hour post-treatment window, or across the entire six-month follow-up, affirming both its safety and durability of therapeutic effect.

By normalizing the inflammatory response and activating the neuroprotective heat shock response, without pharmacologic agents or infectious stimuli, CBIT² provides a molecularly grounded and clinically actionable strategy for the restoration of motor neurons in ALS, a disease historically defined by relentless progression, therapeutic failure, irreversibility, and fatal outcome.

Malarial fever therapy, initially developed to combat spirochete infection in neurosyphilis through induced fever, earned the Nobel Prize in Medicine in 1927, though its impact on brain pathology was not yet understood at the time. Nevertheless, this fever-based intervention was rapidly validated across Europe for achieving what was once deemed impossible: the reversal of advanced neurological disease, with restoration of both motor and cognitive function in patients with dementia paralytica [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. This disease reversal by malarial fever therapy that was later extensively documented across diverse populations worldwide, emptied asylums once filled with paralyzed patients facing inevitable death, and established, more than a century ago, that brain damage is, in fact, reversible, which is the principle that supports the restoration of brain function in ALS reported here. However, there is a major distinction in the proposed mechanisms. Restoration from malarial fever was historically attributed to the fever-induced death of

Treponema pallidum. By contrast, Abreu recognized that fever itself was capable of restoring brain function through activation of the heat shock response, a molecular defense that acts directly on misfolded proteins such as TDP-43. The findings described above, and confirmed in our patient, demonstrate that neuronal recovery arises from the direct biomolecular effect of fever-induced heat shock responses acting at the level of injured nervous tissue.

CBIT2 represents a paradigm shift from symptom management to disease-modifying therapy that transformed fever into a computer-controlled treatment guided by real-time feedback from the brain’s thermoregulatory center. The mechanistic rationale for this unprecedented recovery in ALS lies in hypothalamic-guided induction of the heat shock response. By directly addressing misfolded proteins such as TDP-43, the molecular driver of ALS pathology, CBIT² restores proteostasis and neuronal function via HSP induction. Unlike saunas or conventional hyperthermia, which trigger heat-dissipating reflexes and oppose therapeutic temperature elevation, CBIT² operates in synchrony with hypothalamic pathways via the Brain–Eyelid Thermoregulatory Tunnel, enabling safe, titrated induction of therapeutic fever without adverse effects. This noninvasive approach transforms the hypothalamus from an opponent into the driver of fever, overcoming physiological barriers that have limited prior thermal therapies.

Using continuous, noninvasive monitoring of brain temperature and thermodynamics at the eyelid via the BTT, this intelligent system modulates thermal delivery via a thermal chamber and an eyelid heat inductor to prevent hypothalamic counterproductive cooling mechanisms, maintaining alignment with thermoregulatory response required to induce therapeutic thermofebrile response. CBIT

2 integrates algorithmically controlled and synchronized delivery of radiative and conductive heat directed by hypothalamic signals through a computerized platform having a sensor assembly, thermal chamber, eyelid heat inductor, and an intelligent closed-loop feedback control (

Figure 1). Bidirectional heat exchange in concert with the hypothalamus is achieved by a sensor at the BTT site capturing efferent brain thermal signals while a heat inductor delivers afferent inputs, resulting in a controlled rise and fall in brain temperature, reaching up to 41.6 °C, that replicates the natural cyclic rhythm of malarial fever within a safe, noninfectious therapeutic architecture, which is enabled by the discovery and characterization of the BTT [

46].

Emerging molecular evidence unveils a surprising mechanistic bridge between the dramatic recoveries once seen with malarial fever therapy in 1927 and the remarkable restoration of motor neuron function in 2025 observed in ALS following CBIT

2. Though separated by more than a century and distinct in etiology, neurosyphilis and ALS reveal a striking pathological convergence at the molecular level marked by the accumulation of misfolded proteins forming TDP-43 aggregates [

42,

43]. This shared molecular pathology reveals disrupted protein homeostasis as a disease mechanism in both neurosyphilis and ALS, suggesting that targeted fever-based modulation may offer an effective treatment to restore neural function. Just as malarial fever therapy reversed motor and cognitive decline in dementia paralytica, the digitally controlled, brain-guided programmed fever described here restored lost motor and cognitive function in ALS, revealing a molecular mechanism spanning a century of clinical practice.

By eliminating the risks associated with malarial infection including potentially fatal complications such as cerebral malaria caused by parasitic invasion of the brain, CBIT2 safely replicates the intensity and cyclic dynamics of malarial fever once used to cure dementia paralytica, transforming this century-old therapy into a noninfectious, titratable, computer-guided intervention. In a single 2.5- to 5-hour treatment session, CBIT2 delivers an average of two cycles of thermofebrile activation mimicking malarial fever, consisting of hyperthermia via chamber and fever induction via hypothalamic signaling at the BTT site, dynamically calibrated to the patient’s individual hypothalamic thermal signal, thereby avoiding conflict with central thermoregulation while enabling safe induction of programmed thermofebrile response.

Hypothalamic-driven treatment by CBIT² stands in stark contrast to saunas and conventional skin-heating methods—including infrared hyperthermia devices, resistive heating systems, radiant heat panels, far-infrared equipment, infrared therapy beds, heat blankets, and whole-body hyperthermia systems—which act at the skin surface. These approaches stimulate cutaneous thermoreceptors and trigger hypothalamic heat-dissipating reflexes, turning the brain into an opponent, as occurs with saunas, actively fighting against the very temperature elevation required for therapy. In effect, the brain deploys its thermal defenses as a barrier, activating cooling mechanisms, and preventing the safe achievement and maintenance of the core and brain temperatures needed for robust activation of heat shock transcription factors. CBIT² uniquely overcomes this physiological opposition, transforming the hypothalamus from an opponent into the driver of therapeutic fever.

Additionally, hyperthermia methods lacking synchronization with hypothalamic thermoregulation can subject patients to significant physiological distress including dizziness, nausea, vomiting, respiratory compromise, and even loss of consciousness, severe brain thermal injury, and coma [

51] as externally applied heat to the body surface conflicts with central thermal signaling. Because unopposed hypothalamic-driven heat dissipation mechanisms counteract heat applied to the skin surface, as occurs with conventional whole-body hyperthermia, achieving therapeutic temperature levels often requires excessive heating, which may lead to complications such as heatstroke, respiratory arrest, and brain injury. Despite their associated physiological burden and significant safety risks, conventional whole-body hyperthermia methods frequently fail to achieve or sustain therapeutic fever temperatures, such as the 41.6 °C observed in malarial fever, primarily due to misalignment with hypothalamic thermoregulatory control. Efforts to mitigate these uncomfortable and potentially serious adverse effects through conventional anesthetics are similarly counterproductive, as these agents disturb thermoregulatory function and are well documented to induce intraoperative hypothermia [

52], directly opposing the desired thermal increase for effective heat shock response.

Attempts to achieve therapeutic temperature levels during whole-body hyperthermia for cancer treatment have been constrained by serious safety concerns, including coma resulting from excessive heat exposure compounded by reliance on rectal temperature monitoring [

51], a technique known for over a century to inadequately reflect brain temperature [

53,

54,

55,

56,

57], resulting in undetected cerebral thermal overload and potentially life-threatening complications. In sharp contrast, CBIT

2 titrates perihypothalamic temperature, using digitally synchronized, hypothalamic-guided modulation to replicate the therapeutic dynamics of malarial fever without triggering defensive cooling responses, enabling a safe, well-tolerated, and effective treatment.

By advancing the Nobel Prize-recognized fever-induced disease reversal with digital precision, CBIT

2 safely offers a potential treatment not merely to slow but to reverse neurodegenerative processes. In the ALS case presented, reversal was supported by objective improvements in motor function, reductions in disease-associated blood biomarkers, and increased expression of heat shock proteins. The restoration of functional independence and recovery of complex motor tasks, such as dancing, singing, and playing golf, including coordinated swings and successful hole completion, in the ALS case here suggest reversal of underlying neurodegenerative pathology, closely resembling the total restoration of lost brain function once achieved a century ago with malarial fever therapy [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18].

A profound impact, with implications for all ALS patients, was revealed electrophysiologically (see

Appendix A). Following CBIT², EMG demonstrated the complete absence of denervation across all tested muscles, which is a remarkable finding given that continuous active denervation, prior to BTT-based programmed fever therapy, is a hallmark of ongoing motor neuron death in ALS. The disappearance of both fibrillations and fasciculations previously present provides irrefutable electrophysiological evidence that the pathological process of motor neuron degeneration was eradicated. Moreover, widespread chronic reinnervation changes observed in the absence of denervation confirmed that compensatory mechanisms were active and now proceeding without ongoing neuronal destruction. These electrophysiological results were paralleled by normalization of disease-associated molecular biomarkers and objective neuromuscular recovery, further reinforcing the conclusion that the underlying neurodegenerative process had been reversed. The clinical, molecular, and electrophysiological findings challenge the long-standing view of ALS as an irreversible and fatal condition, suggesting that CBIT

2 may reactivate the therapeutic principle of malarial fever, first successfully applied to reverse dementia paralytica, and now offering a path to structural and functional brain recovery in ALS.

CBIT

2 induced significant clinical improvements, supported by objective quantitative measures as well as patient self-report and physical therapist evaluations. These included increased strength in the arms and legs, improved balance and gait, improved bulbar function (enhanced speech, salivation and swallowing), improved fine motor (handwriting, cutting food), coordinated motor (playing golf and pickleball) and gross motor (walking, stair climbing) activity and improved pulmonary capacity, as well as gains in visuospatial function and cognition. Objective assessments confirmed enhanced motor control balance with eyes open (EO) and eyes closed (EC), feet apart (FA) and feet together (FT) (

Figure 2), normalized gait (

Figure 3), restored cognition (

Figure 4), increased tongue endurance and improved speech articulation. These functional improvements were accompanied by a five-point increase in the ALSFRS, sustained over a six-month period, an outcome of particular significance given that the ALSFRS is primarily designed to measure progressive decline, and a sustained increase or stabilization in score is considered both exceptional and clinically meaningful [

58]. Notably, even edaravone, an approved drug known for its ability to slow ALS progression by preventing neuronal damage, has not been able to produce a significant difference in ALSFRS-R scores compared to placebo [

59]. Although previous studies have demonstrated that a subset of patients with early-stage ALS experienced a slower rate of functional decline with edaravone, they have failed to demonstrate any increase in ALSFRS-R scores [

60].

At the biomarker molecular level, the response observed following CBIT

2 indicates a shift from active neurodegeneration toward neuronal preservation and recovery, reflected in meaningful changes in biomarkers associated with ALS progression and fatal outcome. Blood levels of NfL are considered robust predictors of ALS progression [

61], and their reduction, as shown here post BTT-based programmed fever, has been explored as a promising therapeutic target with disease-modifying potential, as exemplified by tofersen, an antisense oligonucleotide recently approved for the treatment of ALS in adults with SOD1 (superoxide dismutase-1) gene mutations [

21].

Our results also revealed a striking and unprecedented molecular finding involving normalization of IL-10, a cytokine whose persistent elevation in ALS is a hallmark of relentless neuroinflammation and a harbinger of poor prognosis and mortality [

62]. This cytokine normalization (IL-10) followed the second treatment and coincided with a marked increase in HSP70 expression, rising from 6.82% after the first session to 53.4% post-second session. Elevated IL-10 has been inversely correlated with survival in ALS, and its downregulation may signal reduced inflammatory burden and a departure from a fatal disease trajectory post CBIT

2. Together, the reduction in neurofilament and homocysteine, which are biomarkers associated with neuronal death [

61] and poor prognosis in ALS [

63], respectively, alongside the normalization of IL-10, provides early evidence that CBIT

2 may halt the pathological course of ALS and initiate a process of functional restoration and molecular reversal.

The neuromuscular, molecular, and electrophysiological improvements observed are consistent with a CBIT²-induced rise in heat shock proteins (HSPs). HSPs are molecular chaperones that regulate protein folding, degradation, and cellular stress responses, while preventing the accumulation of neurotoxic aggregates, which are functions that are critically impaired in ALS [

64,

65]. Among them, HSP70 is especially notable for its neuroprotective and restorative roles, including counteracting misfolded protein toxicity, enhancing cellular resilience to oxidative stress, and facilitating neuronal repair [

31,

66,

67]. The ability to use programmed fever to induce HSP70 noninvasively in a clinical setting represents an unprecedented therapeutic achievement, long considered unattainable, and provides a mechanistic foundation for the reversal of neurodegeneration documented in this case.

ALS reversal aligns with the principle of malarial fever therapy, that we revealed here may have acted at the molecular level by refolding misfolded TDP-43 protein and eliminating toxic aggregates in dementia paralytica. Studies in ALS animal models have shown that exogenous HSP70 administration enhances neuromuscular function and prolongs survival [

32,

67]. These findings parallel those in the present case, which demonstrated improved neuromuscular performance accompanied by normalization of IL-10 levels, which is a biomarker shift associated with extended survival, as elevated IL-10 has been linked to increased mortality [

62]. Upregulation via histone deacetylase inhibitors enhances motor neuron resistance to stress-induced damage [

68] and regional differences in HSP expression and inflammation in ALS may influence disease progression [

69], supporting the potential of HSP-modulating therapies, as shown here.

The collapse of the cellular stress response in ALS disrupts proteostasis, leading to the accumulation of misfolded proteins and neurotoxic aggregates. In contrast, CBIT² induced a robust upregulation of HSPs, which may restore proteostatic balance by enhancing chaperone-mediated protein folding and promoting the clearance of toxic aggregates. These molecular effects are consistent with the known role of HSP70 in maintaining proteostasis and regulating neuroimmune signaling. Through activation of HSF1, HSP70 suppresses inflammatory cascades involving NF-κB (nuclear factor kappa B) and JNK (c-Jun N-terminal Kinase) [

70] besides reducing cytokine production [

71] while modulating glial activity by inhibiting pro-inflammatory microglial phenotypes (M1) [

72], enhancing anti-inflammatory responses, and reducing astrocyte reactivity [

70]. This immunological modulation highlights a broader mechanism by which CBIT

2 restores immune homeostasis and reverses molecular hallmarks of ALS progression and mortality. The upregulation of endogenous HSPs during CBIT

2 thus offers a promising avenue for ALS treatment and disease reversal, paralleling malarial fever therapy outcomes that achieved clinical cure in neurosyphilis despite structurally damaged brain tissue harboring misfolded TDP-43, which is also present in ALS, further supporting the plausibility of a cure for ALS.

Clinical studies have tested pharmacological amplification of the heat shock response, such as with arimoclomol, a co-inducer that enhances HSP70 expression. However, despite its mechanistic rationale, arimoclomol failed to provide meaningful clinical benefit in ALS patients and was associated with adverse effects including approximately 29% increase in NfL levels compared with placebo [

20], which is in sharp contrast to reduction of NfL observed following CBIT².

We anticipate that the impact of CBIT

2 on HSP levels will constitute a major therapeutic breakthrough. In this two-session introduction of CBIT

2, HSP70 increased by 53.4% between pre1 and post2 determinations, reaching a peak increase of 64% two months after the first treatment session. The observation that HSPs in our patient reached their highest at the assessment two months after the first CBIT

2 treatment is consistent with a multi-step process which includes treatment-induced release of HSF1 which in turn causes DNA-mediated synthesis of HSPs via heat shock element gene. It has been shown in in vitro primary culture ALS models that activation of HSF1 enhances motor neuron survival, reducing protein aggregation and mitigating proteotoxic stress [

27].

The prolonged therapeutic impact of CBIT² observed in this case reinforces its biological plausibility and supports the durability of its effect. The heat shock response activated by CBIT² is a well-established neuroprotective and restorative mechanism, associated with reduced neuroinflammation, enhanced cellular resilience to oxidative stress, and decreased accumulation of misfolded proteins, which are hallmarks of neurodegenerative disease [

31,

66,

67].

In apparent contrast to the known effects of hyperthermia on HSP activity [

73], a thoughtfully designed study using a mouse model of ALS reported potential therapeutic effects of chronic intermittent mild whole-body hypothermia [

74]. By inducing mild hypothermia through chronic intermittent cooling cycles, investigators observed delayed disease onset, improved neuromuscular junction integrity, and prolonged survival in the mouse model of ALS [

74]. They also demonstrated that hypothermia restored levels of HSP70 and other molecular chaperones, further supporting its neuroprotective effects in the mice [

74]. The findings further support the rationale for developing thermally-based therapies, both fever and cooling, for neurodegeneration. It remains to be determined how temperature(s) and thermodynamics impact the structural and functional deterioration(s) of ALS. The ability to noninvasively assess brain temperature and hypothalamic responses via the BTT and its correlation with disease activity may help address longstanding questions in ALS pathophysiology. However, species-specific genetic differences, particularly those influencing synaptic connectivity and neural circuitry, likely contribute to the therapeutic effects of hypothermia observed in ALS mouse models [

75]. While such animal models provide valuable mechanistic information, it is well recognized that these interspecies distinctions limit the direct translation of findings to human neurobiology [

75].

The customization of brain-guided programmed fever to enhance both efficacy and safety, nearly a century after Wagner-Jauregg’s revolutionary, life-saving fever therapy, has been enabled by the discovery of the BTT, the first identified thermal waveguide in the human body, consisting of previously unrecognized bidirectional, bilateral pathways conducting thermal signals between the hypothalamus and the eyelid [

46]. The discovery of the BTT has enabled, for the first time, noninvasive access to the hypothalamic thermoregulatory center, allowing continuous brain temperature monitoring via a noninvasive surface sensor placed on the eyelid, confirmed by recent studies showing brain cooling during yawning [

47]. Studies have shown measurement of brain temperature noninvasively via the BTT during neurosurgery and distinguished BTT temperature measurements from those of neighboring skin as well as from blood surrounding the brain (e.g. during open-heart surgery) and ipsilateral to unilateral seizures [

46]. Afferent thermal input from the eyelid skin to the brain is supported by the presence of heat-sensitive coatings on the trigeminal nerve as it courses along the wall of the cavernous sinus [

76], at the terminal segment of the BTT [

46].

Recognition of the BTT has enabled development of the computerized system presented herein, allowing precise modulation of both systemic and brain temperatures through cyclical increases and decreases in heat delivery to the body core via a thermal chamber and to the hypothalamic thermoregulatory center via a BTT thermal inductor positioned on the eyelid (

Figure 1). Digital control of the thermal chamber and eyelid-mounted inductor allows CBIT

2 to maintain stable thermoregulation and brain-to-core temperature differentials that align with the body’s natural fever threshold [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18].

The sustained upregulation of HSPs and accompanying biomarker normalization support a disease-modifying effect; however, the durability of these benefits beyond the current 6-month follow-up remains unknown. Further studies and large clinical trials are required to determine whether repeated CBIT2 sessions can achieve cure comparable to those historically observed with malarial fever therapy.

By brain-guided programmed fever offering a biologically supported method to augment endogenous HSP expression, it may enhance the effect of pharmacological chaperones like arimoclomol [

68], supporting future studies on combining CBIT

2 with arimoclomol therapy addressing proteostasis restoration. Moreover, CBIT

2 through targeted induction of the heat shock response may provide a biologically complementary mechanism to existing FDA-approved ALS therapies and potentially enhance their therapeutic efficacy. Riluzole, which reduces glutamate-mediated excitotoxicity [

22], may be potentiated by fever induced HSP-mediated neuroprotection via protein stabilization and attenuation of oxidative stress. Edaravone, an antioxidant that mitigates neuronal oxidative injury [

60], may benefit from enhanced cellular resilience and free radical buffering induced by HSP-mediated programmed fever. For tofersen, an antisense oligonucleotide that reduces toxic SOD1 protein levels in ALS associated with SOD1 mutation [

21], CBIT

2 may act synergistically by facilitating the refolding and clearance of misfolded proteins. This combination may support multimodal disease modification by addressing excitotoxicity, oxidative stress, and proteostasis dysfunction, complementing CBIT

2-induced heat shock protein activation as a unified strategy with pharmacological agents towards curing for ALS.

By activating HSPs and restoring proteostatic equilibrium, the brain-guided programmed thermofebrile activation introduced in this report offers a therapeutic strategy for reversing neurodegenerative pathology by directly targeting its root cause: misfolded proteins. What was once a mysterious clinical phenomenon that restored function and completely reversed disease in patients with dementia paralytica over 100 years ago is now revealed as a scientifically grounded molecular strategy targeting misfolded TDP-43, rekindling the long-dormant legacy of fever-based treatment, not as a historical curiosity, but as a renewed frontier in modern molecular medicine.

Beyond ALS, this breakthrough opens the path to treating and potentially curing other devastating neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, Huntington’s disease, Lewy body dementia, the spinocerebellar ataxias, frontotemporal dementia, vascular dementia, multiple system atrophy, progressive supranuclear palsy, corticobasal degeneration, and prion diseases such as Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease, which are conditions long considered irreversible and uniformly fatal. In addition, the same mechanistic principles of protein misfolding reversal may extend to non-fatal but highly debilitating disorders such as autism spectrum disorders and diabetic neuropathy, widening the therapeutic horizon of brain-guided programmed fever.

This renewed molecular understanding of fever-induced therapeutic effects in neurological disease resulting in brain restoration, emerges at a critical moment in history. ALS, long regarded as irreversible and fatal, may now serve as a gateway for therapeutic innovation for effective neurological treatment amid one of the most urgent global health crises, as highlighted by the alarming announcement by the WHO that neurological disorders affect over 3 billion people worldwide [

2]. Moreover, according to the WHO neurological disorders are the leading cause of disability [

2], posing a profound threat to societal stability by diminishing workforce capacity, increasing long-term care demands, and straining healthcare systems worldwide. In the United States alone, Alzheimer’s disease generated

$360 billion in direct costs in 2024 [

77], projected to reach

$384 billion in 2025 [

78], with an additional

$413 billion linked to 19 billion hours of unpaid caregiving [

78], totaling an annual burden of

$773 billion, revealing a looming socioeconomic crisis worldwide. As WHO Director-General Dr. Tedros A. Ghebreyesus warned,

“Neurological conditions cause great suffering to the individuals and families, they rob communities and economies of human capital”[

2].

Neurological disorders now constitute one of the most debilitating and economically destabilizing health burdens worldwide, affecting cognition, motor control, speech, and even vital functions such as swallowing and respiration. A central driver of this crisis is the pathological accumulation of misfolded proteins across multiple age groups, disrupting brain function in conditions ranging from ALS in otherwise healthy individuals and elite athletes to Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease in the aging population. The global wave of protein misfolding disorders extends even to the young as Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), is increasingly being recognized as involving disrupted proteostasis [

79], which may be responsive to therapies that activate HSPs [

80]. The well-documented ‘fever effect’, where febrile illness transiently improves behavioral symptoms in ASD, suggests that endogenous fever pathways can modulate neurological function [

81]. This effect is further supported by studies demonstrating that sulforaphane improves ASD symptoms through activation of the heat shock response and upregulation of HSPs [

80].

Proteopathic disorders are increasingly linked to this global public health emergency, as neurological diseases now affect more than one in three people worldwide. With the WHO projecting neurological disorders to become the second leading cause of death globally, today’s crisis of disability is on track to become a mass mortality event [

3]. This escalating threat compels a renewed scientific focus on therapeutic fever, first documented in a 1917 case report describing recovery from dementia paralytica [

15]. Now, 108 years later, this ALS case report may serve as its modern molecularly based counterpart, reopening the possibility that advanced neurodegeneration can be therapeutically reversed. However, unlike the localized threat of neurosyphilis a century ago, today’s challenge is global as misfolded proteins are now recognized as central drivers of the most prevalent and debilitating neurological disorders.

The successful induction of therapeutic fever using CBIT

2 in ALS, a disease historically regarded as uniformly progressive and notably resistant to treatment due to its exceptionally high threshold for HSP induction [

24], reframes this terminal condition as a potential therapeutic gateway. In this case report, the comprehensive restoration of motor and cognitive function following CBIT

2 demonstrates that even the most treatment-refractory neuronal populations, such as motor neurons, can undergo recovery through the reactivation of endogenous repair mechanisms. If proteostatic resistance can be overcome in ALS, it is plausible that brain regions with lower activation thresholds may exhibit even greater response. Indeed, preliminary findings from ongoing applications of CBIT

2 in other misfolding-related disorders including Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, Huntington’s disease, progressive supranuclear palsy, and ataxias have revealed clinical and biomarker changes suggestive of disease modification and brain restoration.

These therapeutic effects likely reflect the molecular reactivation of cytoprotective pathways, including HSP–mediated refolding of misfolded proteins such as TDP-43, restoration of proteostasis, and stabilization of neuronal structure and function. Together, these processes support the biological and molecular rationale for therapeutic fever as a strategy capable of restoring functional neural networks, opening new possibilities for care and redefining what is achievable in the treatment of neurodegenerative disease. Collectively, these results position ALS not only as a clinical inflection point but as a critical entry point to developing disease-modifying therapies, addressing its molecular roots, across diverse neurodegenerative as well as neurodevelopmental pathologies as ASD.

Patient perspective

Following CBIT², functional gains continue to advance and remained strikingly evident. At a local golf course, 3 months after CBIT2 the patient walked unaided to the green with restored balance and motor control. She lined up her putt and sank the ball into the hole, twice in succession. Further underscoring her recovery, she later shared a video of herself putting at home, sending the ball into the cup with a single, fluid swing on her first attempt (Video S16) in addition to returning to play pickleball (Video S17). While visually impressive, these moments conveyed something beyond what any clinical scale, test, or biomarker could capture: the restoration of ordinary life, the freedom to live life to the fullest once more, echoing the profound and complete recoveries documented a century ago during malarial fever therapy. This regained ability to play golf and pickleball revealed a clinically meaningful restoration of neuromotor precision, postural control, balance, and complex coordination, capacities once considered irretrievable in the course of ALS.

5. Conclusions

This case report demonstrates, for the first time, that ALS, long regarded as an irreversible and uniformly fatal neurodegenerative disorder, can be reversed through CBIT², a fully noninvasive treatment that reengineers the 1927 Nobel Prize–recognized malarial fever therapy into a modern, intelligent, brain-guided digital intervention.

The patient, a 56-year-old woman, was diagnosed with ALS at the Mayo Clinic, based on electromyography confirming denervation and fasciculations along with neurological and MRI findings. Northwestern University independently confirmed the diagnosis and continued her on FDA-approved ALS drugs riluzole and edaravone. Despite expert management at both institutions, her disease progressed relentlessly, consistent with expectations for ALS, a disorder defined by paralysis, respiratory failure, and death.

Yet following treatment by Dr. Marc Abreu in his private practice at the BTT Medical Institute, using CBIT² delivered through an FDA-approved computerized platform, this fatal trajectory was not merely slowed but fundamentally transformed achieving neurological, molecular, and electrophysiological reversal of ALS. Electromyography revealed the disappearance of denervation and fasciculations, signifying eradication of motor neuron death, while biomarkers shifted toward recovery with reductions in neurofilament light chain and homocysteine, normalization of IL-10 (with levels prior to CBIT2 linked to increased mortality), and a dramatic rise in HSP70 expression. Correspondingly, the patient progressed from walker dependence to restored gait, safe swallowing, improved respiration, enhanced speech, and cognition restored to normal score. Most strikingly, she regained the ability to perform complex motor tasks including walking unaided onto a golf green, sinking consecutive putts, and playing pickleball, signaling not only survival, but a return to full life once thought irretrievably lost. Confronted with the extraordinary absence of diagnostic evidence for ALS, her Northwestern neurologist discontinued all ALS-specific medications, an outcome previously unimaginable for ALS.

Dr. Wagner-Jauregg’s pioneering case report, published more than a century ago, described the reversal of dementia paralytica through deliberate fever induction [

15], the first step in revealing fever’s curative potential for neuropsychiatric disease. Initially met with skepticism, clinical trials confirmed its effects, reshaping neurology and psychiatry and earning recognition by the 1927 Nobel Prize. In that same lineage, the current report extends Wagner-Jauregg’s vision into the modern era with digital precision. Using CBIT², fever is no longer a dangerous byproduct of infection but a brain-guided, programmable therapy delivered safely and noninvasively through the Brain–Eyelid Thermoregulatory Tunnel (BTT). Just as malarial fever once restored patients from the devastation of neurosyphilis, CBIT² here restored a patient from the devastation of ALS, a disease long considered irreversible and fatal.

This convergence of digital medicine and neurobiology reawakens the Nobel-recognized principle that fever can restore neurological function, offering a molecularly grounded strategy for disease reversal. Unlike externally applied heat or conventional hyperthermia, which often fail to trigger the heat shock response and may provoke physiological distress or even fatal complications, CBIT² operates in synchrony with hypothalamic thermoregulation, enabling safe, titrated, and effective induction of therapeutic fever with robust HSP activation. This fully noninvasive procedure exhibited an excellent safety profile, with no adverse events observed during treatment, within the critical 48-hour post-treatment window, or across six months of follow-up.

Beyond the confines of this case, our intervention responds to a broader global emergency, aligned with the Brain Economy Declaration at the June 2025 Brain Economy Summit, where G7 leaders urged prioritization of brain health as essential economic and societal infrastructure. In this context, the tragic irony of the Ice Bucket Challenge, co-founded by ALS patient Pete Frates, engaging over 440 million people and virtually every major celebrity and many heads of state, which raised hundreds of millions of dollars, yet yielding no therapeutic breakthrough while Frates himself died of ALS, which underscores the urgency of translating awareness into cures.

Taken together, these insights provide a compelling rationale for rigorous, large-scale clinical trials to confirm reproducibility, define durability, and establish the broader therapeutic potential of CBIT². What begins here with ALS may extend to Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, Huntington’s disease, Lewy body dementia, spinocerebellar ataxias, frontotemporal dementia, multiple system atrophy, progressive supranuclear palsy, prion diseases, and beyond. The same molecular misfolding protein logic may also apply to nonfatal but debilitating disorders such as autism spectrum disorder and diabetic neuropathy.

By reviving Nobel Prize–recognized fever therapy a century later, not as memory but as method, CBIT² transforms medical history into medical future, opening a new frontier where brain function can be restored, lives reclaimed, and the trajectory of the global neurological crisis fundamentally changed. What is ultimately at stake is nothing less than the preservation of thought, memory, movement, and independence for over one third of humanity.