1. Introduction

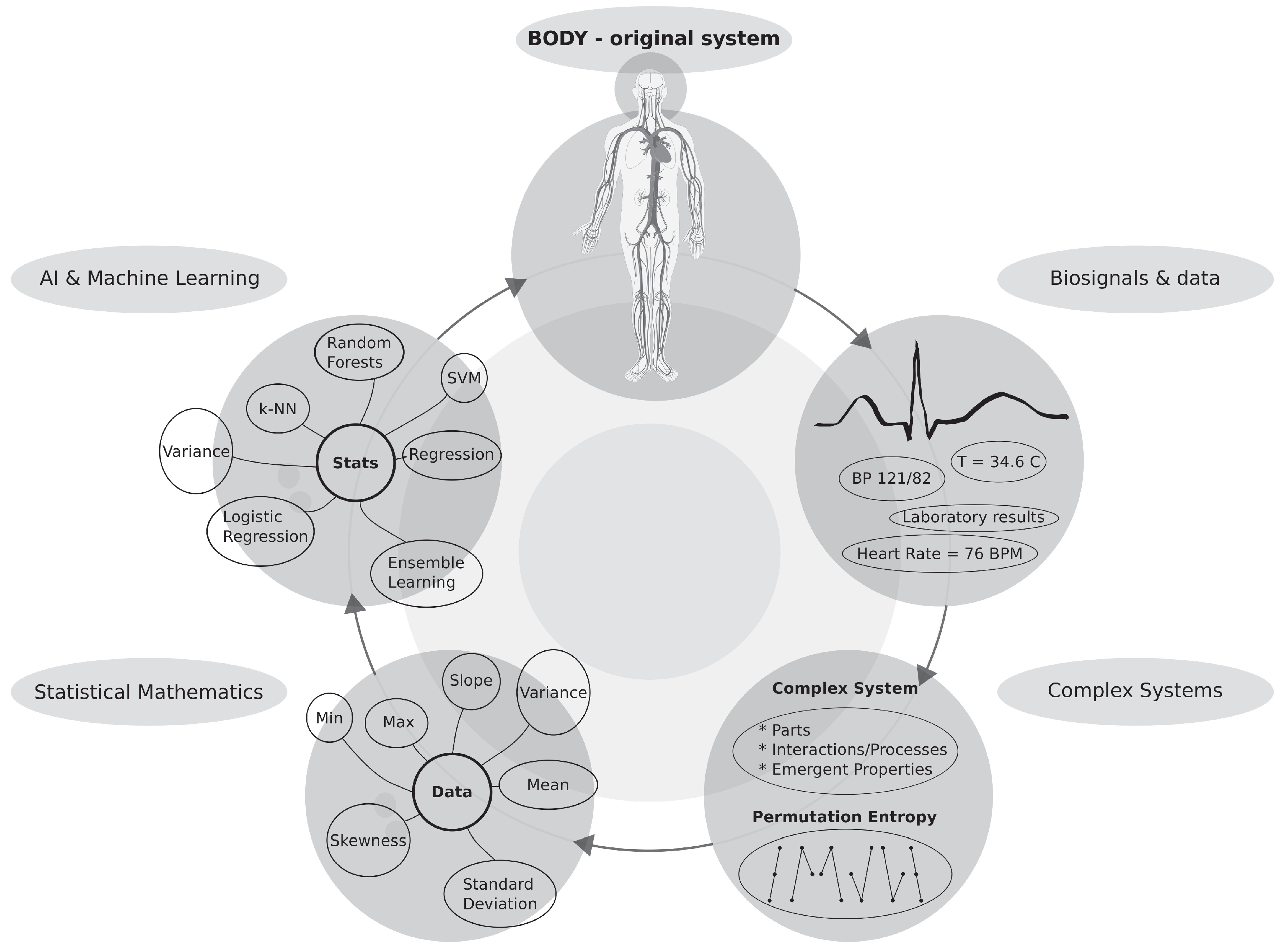

Medicine is facing one of the biggest challenges it has gone through during its history. It is gathering ever-increasing amount of imaging, genetics, epigenetics, proteomics, interactions of cells with drugs, raw physiological, and other types of data. Despite such a huge amount of information—it is better to say, due to it—in most cases, we are unable to understand the functioning of body parts and systems, including the physiology of human bodies, to the level applicable in therapy. We are aware of the fact that a deep understanding of regulatory mechanisms existing and operating at the levels of cells, tissues, organs, and bodies is critical for understanding many diseases, their causes, and their possible therapies. Fortunately, some of those hidden regulatory mechanisms just started to be revealed. This brings us to the main goal of this paper.

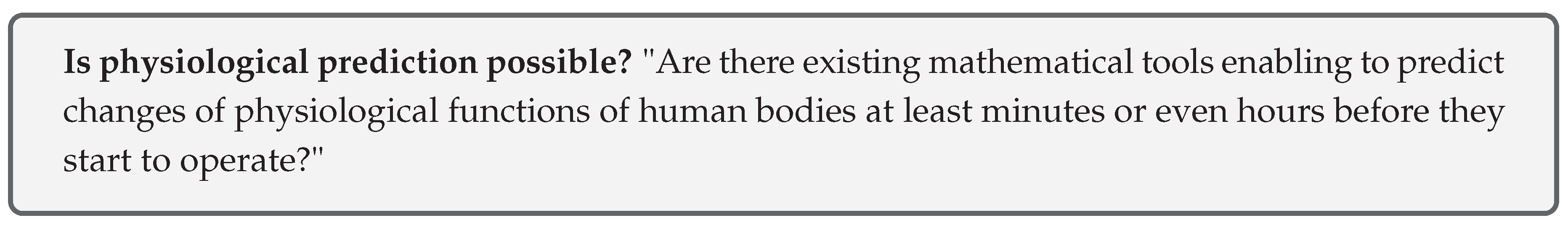

We are aware of the fact that deeper understanding of different segments of human physiology will enable medicine to make a crucial step towards better understanding of human body functioning as a whole and to design novel, so-far-inaccessible, complex, dynamically changing therapies based on this knowledge. Hence, we address the following general question:

This general question will be studied on a specific, simple model of the rabbit heart that is leading to the drug-induced

Torsades de Pointes (TdP) arrhythmia [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7].

Currently, we are already aware of the fact that organs and their regulatory systems are mutually influencing each other, but we are still mostly unable to reveal the exact topology, interdependence, and real effects of those regulatory networks and to quantify them (e.g., see books on the application of AI in medicine [

8,

9], examples of the central nervous system and emotions [

10,

11], and the heart [

7,

12]). To achieve this goal, the following steps must be accomplished:

(a) huge data sets of digitized, physiological recordings must be collected (e.g., ECGs, EEGs, breath patterns) with their relevant medical classification (distinction among various cases),

(b) they must be provided as open access data (with citations of teams which are providing them plus their responsibility),

(c) data will serve as the calibration tool to all newly developed mathematical methods and as means of comparison of various methods (there will be available versions of databases and their closing dates),

(d) all newly developed mathematical tools and methods will be tested on them,

(e) physiological dependencies will be gradually revealed and cross-tested,

(f) only tested therapies based on such physiological knowledge will be used medically,

(g) any failure of an already developed method will be studied and initiate the improvement of the database, and

(h) medicine can gradually achieve holistic modularity (this means that it can be treated locally while being aware of holistic responses due to knowledge of physiology networks) in this way. This automatically leads to a possibility of highly individualized therapies and not statistically based therapies (RCTs). There already exists a whole range of successful pilot physiological studies in some areas, providing proof of the vitality and importance of this approach [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. Unfortunately, researchers are still quite far from mapping the whole physiology in this way; one of the reasons is a lack of knowledge about emergent information processing that relies on the massively-parallel nature of all living systems [

24,

25,

26,

27].

The current physiological research on animals and humans faces several principal difficulties and obstacles, which inevitably occur during any attempt to better describe, understand, and predict the actual physiological state of the various bodily functions. The first obstacle: an intricate network of physiological processes (further called the physiological network) where said processes are often mutually entangled in unexpected ways across all organ systems just started to be revealed. The second obstacle is that when a particular physiological process is studied, we do have to be aware of those interconnections through the physiological network, as it can easily modulate and change the behavior of the studied part according to the changes within the rest of the network (e.g., the heart is heavily influenced by adrenal and thyroid hormones or by the autonomous nervous system). There does not exist an ideal stable operational mode/fixed point within the physiological network operation. Contrary to it, we know that physiological network is constantly changing and adjusting according various physiological inputs (physical or mental stress, digestion, relaxation, etc.).

That all together is a quite challenging situation from the mathematical perspective. It can be said that the structure of the physiological network possess a unique position within the context of the modern medicine and one of the biggest, if not the biggest, challenges in better understanding living organisms in health and disease. Once this network is understood, it will enable medicine to handle diseases and deal with various physiological disturbances from a completely new position using so far unknown and inaccessible treatments. Development of such novel methods and tools enables medicine to measure, to understand, and finally to change and control physiological states of bodies with unprecedented precision.

There are existing many approaches that are enabling measurement of the complexity observed in biomedical systems, for example, entropy [

28,

29,

30] (with its novel reinterpretation [

31,

32] linking it with information), fractals [

33], or statistical [

34] measures. The main idea behind the construction of various measures of complex systems (CSs) is our inability to trace all subtle details of evolving CSs [

35]. Instead, we map the whole system into its simplified form using some kind of measure (see below for an example and detailed description). In the following, we focus our attention to information entropy measures [

30,

36,

37]. A set of the key mathematical tools—which importance has been recently recognized and with one of them used in this study—that are enabling to measure and quantify CSs properties is composed of various types of information entropy: ApproxEn [

13,

38,

39], SampEn [

13], PeE [

40], multiscale entropy [

15,

41,

42], and others [

19,

28,

43,

44].

Entropy is typically designed in such a way that it maps the whole system into a small, restricted set of

K bins with probabilities

. Bins are giving the information about the frequency of an observed event/value falls in a given bin

. Those probabilities

are inserted into the entropy equation. The generic entropy equation [

45,

46],

is measuring variability of probabilities

across all those bins and hence, indirectly, measuring the observed system. All systems that are giving a constant output, i.e., the only one bin is nonzero with

for one index

j, have entropy equal to

because

for

. Whereas, the white noise (all bins have the same probabilities

for all

) has the highest possible value of entropy

because, in such a case, all states of the system are visited equally; the value of

increases with the value

K. All probabilities equal to zero are omitted from the sum (otherwise they will contribute by infinity values in the entropy

equation; that is an unwanted situation).

As already mentioned, better understanding of CSs achieved during the past 20 or 30 years yielded an increasing number of specialized CS measures that are capable of observing major and even subtle changes in biosignal recordings, which are otherwise not accessible to even highly trained specialists, even when using very precise biosignal recordings. The explanation of the major obstacle in the humans comprehension of those biosignals follows. Humans are unable to precisely follow, measure, and classify long intervals of signals having lengths of tens of seconds or even minutes simultaneously. This task must be accomplished for many biosignals simultaneously. That is beyond human comprehension and capabilities, but it is ideal for computer algorithms.

This is the moment when AI and machine learning techniques step in and provide us tools to distill information and classify various behaviors and modes of CSs with unprecedented precision [

8,

9,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51]. The exact procedure of applying ML methods is explained and studied in depth in this case study, which is dealing with physiological changes in heart functioning. The input for this paper is an animal study on rabbits [

52], which were subjected to extremely harsh conditions generating arrhythmias that were artificially induced by the application of arrhythmogenic drugs (anesthetics and cardiomyocyte ion-pump disruptors). The heart occupies a unique position within all physiological studies [

7,

12] because it can be easily, indirectly observed using ECG recordings (we use ’ECGs’ and ’ECG recordings’ interchangeably in the following text) due to the heart’s very strong electromagnetic fields. Similarly, brain observation by EEGs provides another rich source of physiological data [

16,

17]. Unfortunately, other organs do not provide us with such precious physiological data sources due to our inability to detect and measure them as easily and precisely as is done for hearts and brains.

This brings us to the core of this paper: the prediction of drug-induced arrhythmias, which originate in the dispersion of the action potential propagation velocities across the thickness of the ventricular walls. This could lead, under certain conditions, to the creation of a reentry system leading to focally unstable ventricular arrhythmias that are meandering through ventricles, and that are called

Torsades de Pointes (TdP) arrhythmia [

3,

4,

5,

6]. The spiral tip meandering within ventricles—and hence, the location of the reentry system—leads to the typically observed periodic changes of the modulation of the ECG channel amplitudes during TdP arrhythmia because the projection of action potentials into the fixed electrodes is changing with the changing position of the spiral tip. A part of TdP arrhythmia ends spontaneously, but a non-negligible number of them lead to a ventricular fibrillation or flutter and subsequently to a cardiac arrest followed by a death within minutes. Due to TdP’s unpredictability in some patients—even after ruling out long QT syndrome patients who are highly susceptible to TdPs, [

1,

2,

3,

44] and those with a genetic predisposition—TdPs are called, for a good reason, a silent killer.

Only a smaller portion of TdPs is observed within in-patient settings. The actual number of heart arrests caused by TdPs is unknown because it cannot be decided by an autopsy. There exists a still-growing list of drugs that can cause the onset of TdPs in predisposed patients. Often, it comes as a complete surprise to many people that the main cause of drug-induced TdPs results from the use of drugs that are not primarily used to treat heart diseases (e.g., anti-arrhythmics, etc.) [

1,

2,

3] but they somehow manage to disrupt or to interfere with ion channels of cardiomyocytes (including some drugs treating mental disorders by modulation of ion channels in neurons, PPIs, immunosuppressive drugs, etc.). This poses a relatively large risk for patients that have never acquired any heart disease or disturbances during their lives because the occurrence of TdPs is not expected in them (unfortunately, the fraction of unknown susceptible patients is unknown). The ideal solution requires an in-hospital cardiology observation of all patients—or at least several ECG checkups—during the initial stages of the application of those potentially TdP-generating drugs, which is based on acquiring an ECG on a regular basis and searching for their undesired changes.

For example, during the period of time from February to April 2020, when COVID-19 had been spreading in the world, there were existing large cohorts of well-followed patients who were experiencing TdP arrhythmia. The reason was that some of the latest therapies for SARS-CoV-2 are using hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin, chloroquine, and combinations with other antiviral drugs, leading in a high proportion of cases to long QT syndrome and a great risk of TdP arrhythmia—it can be up to 11%, according to this study [

3]. Well documented recordings of those patients can serve as inputs to a database that can be utilized in development of ML methods predicting TdP arrhythmia.

For those reasons, techniques observing prolongation of the QT interval were developed: prolongation of the QT interval is caused by an increase in the variation of action potential duration in different parts of the heart wall. A prolongation of the heart rate corrected

interval above 500 ms is a marker of patients that have a high probability of developing TdPs [

4,

5,

6]. Recently, genetic studies enabled narrowing of the pool of all TdP-susceptible patients by the use of genetic markers. Despite a great effort, there are still many patients who develop a TdP, which is not detectedable by the previous criteria, in out-of-hospital settings—this puts those patients in danger.

It is the exact moment when complex systems can take their place with the already well-established notion of information entropy [

36,

37]. In the recent two or three decades, many information entropy measures have been developed across many disciplines [

16,

17,

53]. Simply said, the actual value of an information entropy measure at a given moment enables to assess the operational state/mode of the underlying CS. Many types of entropy measures demonstrated their usefulness in the processing of biosignals originating in different parts of the physiological network [

20,

42,

54,

55]. ECG signals contain a vast amount of hidden information that just started to be understood and become decodable, which represents a great potential for future research. Permutation entropy (

) can reveal hidden information with high precision [

56,

57,

58]. It is achieved using relatively short signals when compared to other techniques, as is, e.g., heart rate variability (HRV) [

59,

60,

61,

62]. Processing ECGs using

provides a greater deal of the underlying information, which is impossible to reveal by any standard analytic or statistical method. Due to the complicated nature and high dispersion of information among entropy data, it is necessary to apply ML techniques that are capable of revealing those hidden dependencies [

8,

9,

47,

49,

51,

63].

The main goal of this work is to demonstrate that a proper use of the carefully selected CSs measures with the support of ML techniques can reveal unprecedented details from the physiological network. This study is a pilot study of a whole set of possible, more detailed studies that can, one by one, pinpoint so far inaccessible information flows and predictive markers of physiological changes within the physiological network. In the case of drug-induced TdP arrhythmia, it is demonstrated that arrhythmia prediction can be performed with a relatively high precision even on a small set of ECG recordings.

The availability of wearable devices is increasing in sync with their increased penetration within the society. Once the reliable algorithms predicting various life-threatening heart diseases including this algorithm, become available with the specificity and sensitivity high enough, they can be applied in wearable devices and literally save a lot of lives. Due to public safety, the first mandatory applications of such types of algorithms—and devices based on them—will be very probably used in occupations like driver, pilot, astronaut, industrial operator, etc. where a lot of lives and property is at stake due to a potential health collapse of the operator. It can happen due to a heart attack, arrhythmia, ongoing stress, or distress. Currently, detection devices are mostly developed and tested in cars [

64,

65]. Detection of stress and psychological state of the drivers/pilots can help avoid accidents and catastrophes [

66,

67].

This paper deals with the problem of solving the long-term prediction of physiological changes of the heart, which was studied on a pilot, rabbit model where two different cardiomyocyte ion channels modulating drugs were delivered (methoxamine and dofetilide) along with anesthetics (ketamine and xylazine) to studied animals. Some of those rabbits were susceptible to double- and triple-chained premature ventricular contractions (PVCs). Double- and triple-chained PVCs were, in a fraction of the cases, developing into Torsades de Pointes arrhythmias, and those were typically lasting between one and two hours during experimental observations. Firstly, and most importantly, the whole study serves as a template of research strategies that can be applied in similar cases from the complex systems and ML methods points of view. Secondly, the study paves the way towards a completely new class of predictive tools working in real time that are capable of performing a reliable, long-term prediction of physiological functions.

Why is this methodical paper designed in this way? It is written from three distinct points of view: complex systems, biology & medicine, and computational mathematics. Readers coming from different areas of research might find some paper parts redundant due to their expertise. Basically, this paper should be readable to all groups of readers. Nevertheless, it is still the publication about mathematical and computational methods used to classify biological signals, but it is mathematically demanding (introductory and method sections should enable every reader to fill the gaps in the theory).

The structure of the paper is as follows: the role of AI and machine learning in biomedical research in

Section 2, a brief introduction to information entropy in

Section 3, results of (TdP + non-TdP) vs. non-arrhythmogenic rabbits in

Section 4, narrowed results of TdP vs. non-arrhythmogenic rabbits in

Appendix C, discussion in

Section 5, data & methods in

Section 6, and

Appendixes A.1-A.3.

2. Importance and Role of AI and Machine Learning Techniques

in Biomedical Research

Over many millennia, science has been gradually developing a set of increasingly sophisticated mathematical approaches, methods, and theories enabling us to quantify, describe, and predict observed natural phenomena. Currently, as everyone knows, we do have geometry, arithmetic, algebra, calculus, statistics and probability, differential equations, chaos, fractals, mathematical & computational modeling, and simulations within our mathematical toolkit. We are continuously developing even more advanced tools; see for details [

63,

68].

Historically, initially, humans were working with simple numbers used for counting possessions that were soon extended to arithmetic. Simultaneously, the necessity to administer large land areas led to the development of geometry. There had been a long period of stagnation after which infinitesimal values, limits, and calculus with differential equations occurred during the 17th century. This enabled researchers to study physical bodies and develop advanced mechanical theories (e.g., celestial mechanics). Those were later, in the 20th century, extended into deformation of bodies, heat diffusion, and fluid flows described by partial differential equations (implemented using finite element methods). During the 17th century, the development of statistical approaches in physics that are describing ’fluid bodies’ consisting of large ensembles of simple particles (gases, liquids) had started. Those parts have some fixed properties, averages, or distributions, that do not change with time; and hence, the systems under study can reach only some well-defined global states. Studies of large ensembles of atoms and molecules led to development of statistical physics in the 19th century and to the notion of entropy [

69,

70,

71]. In the 20th century, we developed deterministic chaos [

72], chaos [

73,

74], and fractal [

75] theories that enlarged the mathematical toolkit with methods enabling us to describe more sophisticated natural phenomena (weather, solitons, phase transitions, and some emergent structures).

So far, all biomedical theories and models had been based on the application of functions, equations, and more or less defined dependencies, or on statistics & probability [

76]. From the current state of the biological and medical research, it is seen that models based on the above-provided mathematical frameworks fail to describe most of the phenomena observed in those complicated biosystems. What are the main causes of this failure? Currently, scientists are aware of the fact that mean field approximations, which are applied in deriving dependencies among variables, differential equations, and statistical parameters of biological phenomena, are insufficient in capturing and reproducing the fundamental processes operating within biosystems. Let us take a closer look at it.

What are omitted and not well described fundamental processes critical for the precise evaluation and prediction of biological systems’ behavior? Those are mutual interactions among a system’s constituting parts that are operating within the given biological system under consideration, e.g., the human body. Proteins, signaling molecules, genes, epigenetics, distinct regulatory mechanisms, cells, organs, and tissues with their well-defined one-to-one, one-to-many, and many-to-one interactions, which are often spanning multiscale levels, are the key.

Scientists arrived and started intensively studying a theoretical and modeling concept, which can be applied to such a class of problems, that has been developing since around 1980. Simply put, researchers realized that there exists a huge number of systems that are based on interactions of large numbers of relatively simple components that are mutually interacting in parallel within some restricted neighborhood of each component. From and through those interactions, global properties of the system raise, including self-organization, emergence, self-assembly, self-replication, and a whole range of similar phenomena. Gradually, researchers arrived at the concept of complex systems that is often called complexity (do not confuse with complexity of algorithms from the theory of computing); see for the review [

63,

68]. It is a known that complex systems, when well-defined from the beginning—it is meant their local spatio-temporal interactions—produce surprisingly robust and generic responses that are easy to be identified with observed natural phenomena.

Natural phenomena observed in biology and medicine are not efficiently describable by any of the above-mentioned mathematical approaches except the last and newest one. This leads us naturally to the latest mathematical description, briefly described above—which started to be increasingly applied in biology and medicine—to complex systems. Complex systems (CSs) enable us for the first time in the history of science to describe biological systems at the level of their systemic parts and their mutual interactions (see review of such complexity models [

63,

68] and research [

24,

25,

27,

77] along with citations there), as shown above.

The problem with the majority of complex systems-based models of biological phenomena is that their constituent elements are not known. Hence, researchers are incapable of building those models in ways that can be directly compared to observed phenomena. This obstacle in description and understanding of those biological phenomena can be overcome by application of artificial intelligence (AI), machine learning (ML), and deep learning (DL) techniques. Modern techniques developed within AI, ML, and DL [

8,

9,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

78] (see biomedical AI books [

8,

9]) enable us to distill dependencies—from the observed data produced by complex systems—that are otherwise invisible to all other before-mentioned approaches developed in mathematics. Generally, AI enables us to reveal dependencies that must be reproduced by all future, now non-existent, models of biological phenomena. In other words, AI enables us to identify and reconstruct global responses and dependencies of the biological systems that are driving their evolution even without any knowledge of their internal causes. It is possible to distill empiric dependencies in this way. That is why a combination of a well-selected complex system measure (permutation entropy) and machine learning techniques had been applied in this study. This explains research in one sentence.

3. Entropy: Motivation, Three Definitions, and Applications

The historical development of the concept of entropy is quite complicated to follow for non-specialists because it involves several distinct streams of thought—accumulated during centuries—that occurred independently during the development of various scientific disciplines: thermodynamics, statistical physics, and theory of information. It requires deeper understanding of all those disciplines. Such diversity of entropy definitions led, leads, and will lead to much misunderstandings. To make things even more complicated, the concepts and the interpretations of entropy are often misunderstood and misinterpreted even by trained physicists themselves. Awareness about this confusion is increasing, and there are attempts to resolve this confusion [

31,

32,

79]. Not many researchers from across all research fields are aware of this fact—as they expect that there exists just one, ultimate, compact definition of the entropy—when they read about it in any scientific text. But the term entropy is always context-dependent.

This expectation is incorrect. In science, there exist only a handful of more convoluted terms throughout all literature. Briefly, the main source of difficulties with understanding of entropy lays in re-discovering and novel re-defining the notion of entropy within three distinct research areas and contexts: experimental physics (Clausius), theoretical physics (Boltzmann), and theory of communication and information (Shannon).

As explained above, this all created a great, persistent, long-lasting confusion among scientists coming from different disciplines in spite the fact that all definitions within their own research areas and their use there are mostly correct. In his era, Boltzmann himself was facing a big opposition when he proposed the kinetic theory of gases and explained entropy atomistically. Gradually, over centuries, a Babylonian-like confusion of languages has arisen. No one knows what entropy really is. We must be careful when dealing with entropy in our research. Using words of John von Neumann: "Whoever uses the term ’entropy’ in a discussion always wins since no one knows what entropy really is, so in debate one has the advantage." It is crucial to be aware of this confusion originating in the historical development of the entropy concepts.

3.1. Brief History of Entropy

Very roughly said, three major periods of development and application areas of entropy can be recognized in the history: two in physics and one in information theory.

- (a)

Experimental physics—Thermodynamics—Heat machines and Heat engines (Clausius): The development of heat machines such as steam engines, initiated by Carnot, required experimental and theoretical understanding of the conversion of heat into mechanical work. Unexpectedly, it occurred that not all heat energy can be converted into mechanical work. The remaining part of energy that was impossible to convert into mechanical work got the name of entropy (Clausius [

80,

81,

82]); for details, see

Section 3.2.

- (b)

Theoretical Physics—Statistical Physics—Kinetic Theory of Gases (Boltzmann): The necessity to build a theoretical description of entropy led to the development of the entropy equation (Boltzmann [

69,

70,

83]). The idea of quantization of momentum,

, of gas molecules was used. That leads to the well-known Boltzmann equation and velocity distribution; for details; see

Section 3.4.

- (c)

Theory of Communication and Information (Shannon): It occurred that the information content of messages can be described by entropy defined, specially for this purpose. This set of mathematical approaches had been developed within the communication theory. Later it was improved encoding/decoding tool and used by the military during WWII. Even later it was used in computer & Internet communication (Shannon [

45,

46]); for details; see

Section 3.5.

The latest development of the notion of the entropy in quantum physics is not covered here, as it is not relevant to this paper.

3.2. Entropy Definition in Thermodynamics

Carnot, father and son, studied the efficiency of heat machines at the beginning of the 19th century [

80,

81,

82] due to the development of steam engines used by the military. Carnot’s son’s important observation is that the efficiency of the ideal heat engine—which is operating between two temperatures under ideal conditions—depends only on the difference of temperatures and not on the medium itself used within the engine. The efficiency of Carnot’s ideal engine cannot be improved by any other means.

Those observations and conclusions paved the way to the later developed definition of the 2nd thermodynamic law (2nd-TL). Kelvin’s formulation of the 2nd-TL: "No engine operating in cycles pumping energy from a heat reservoir can convert it completely into work." Perfect understanding of the 2nd-TL is very important for understanding a very wide number of quite different processes across the whole spectrum of science, which is ranging from physics across biology towards the theory of information.

Any of the following events is never observed: unmixing of liquids, undissolving of a dye, all heat going spontaneously to one end of a metallic bar, or all gas going to one corner of a room. As we will see later, those processes are principally possible, but their probability is effectively equal to zero, . Clausius came to a significant conclusion that heat cannot spontaneously flow from cold bodies to hot ones due to all those observations! This was later recognized as a variant of the 2nd thermodynamic law. Flow from hot bodies towards those cold is spontaneous. Clausius’s formulation of 2nd-TL puts all those processes under one umbrella term. Additionally, Clausius introduced the term entropy for the first time in history, and it meant ’change’ or ’transformation,’ which is an incorrect formulation within the scope of our current knowledge.

As already explained, entropy was originally defined by Clausius [

80,

81,

82] as the part of energy within a thermal system that is not available to create mechanical work (note that it is just an experimental observation without any theoretical explanation). It is worth emphasizing that the necessity to introduce such quantity originated in the development of thermal machines—steam engines—used to create mechanical work.

Thermodynamic entropy

is defined by the Clausius formula in the form

where

represents change of energy and

T is the temperature of the heat bath, with physical units [J/K].

In an isolated system, when a spontaneous process starts to operate, entropy never decreases. The question "Why is entropy increasing on its own?" is going to be answered in subsequent subsections, as it is impossible to answer within the limits of classical macroscopic thermodynamics. This leads us directly to the mathematical foundations of the mathematical formulation of 2nd-TL.

3.3. Concept of Entropy and Its Mathematical Foundations

Nowadays, it is a little-known fact that in the past—even as recently as in 50s of the 20th century—many physicists looked at probability in physical theories with great suspicion due to a long-standing Newtonian-based clockwise worldview. Nevertheless, after its appearance in physics around the mid-19th century, mathematical probability—together with discreteness of entities and events—besides other concepts, helped to build firm theoretical foundations for the notion of entropy and the 2nd-TL. We explore the mathematical background of this approach that will be utilized in the subsection dealing with the kinetic theory of gases.

Boltzmann discovered [

69,

70,

71,

83] that there exists a connection between all possible microstates, which belong to a given macrostate, and entropy of this macrostate. A macrostate is understood as the volume, pressure, and temperature of some large portions of matter/gas. A microstate is one specific combination of atoms and their properties leading to a given macrostate. There is existing tremendous number of microstates belonging to one macrostate in real physical systems. The best way to understand the mathematical principles that are involved in the concept of entropy and 2

nd-TL is to study throws of independent dice: by following the value of sum of all values on all thrown dice as the measure of their collective behavior. The macrostate of a given throw is the value of the total sum. All microstates belonging to a given macrostate are provided by all combinations of numbers on all thrown dice that are giving the specific sum.

Let us start with throws of two dice; see

Table 1 for the list of all possible macrostates and relevant microstates. The minimal sum is

, and the maximal is

for two dice. Hence, all macrostates are located within the interval

. In general, all macrostates always lie within the interval,

, for

N dice. The number of all possible combinations of outcomes of two dice throws is 36 (microstates), which is higher than 12 macrostates. Most of the macrostates are associated with more than one microstate; see the table. The most probable observed macrostates are having sums of 6, 7, and 8, which together give

microstates; those three macrostates contain almost half of all microstates! They give a 44.4% probability visiting of any of those macrostates. Contrary to it, macrostates 2 and 12 gave only a chance of being visited equal to

each. Remember, this asymmetry because it is crucial for understanding of the 2

nd-TL.

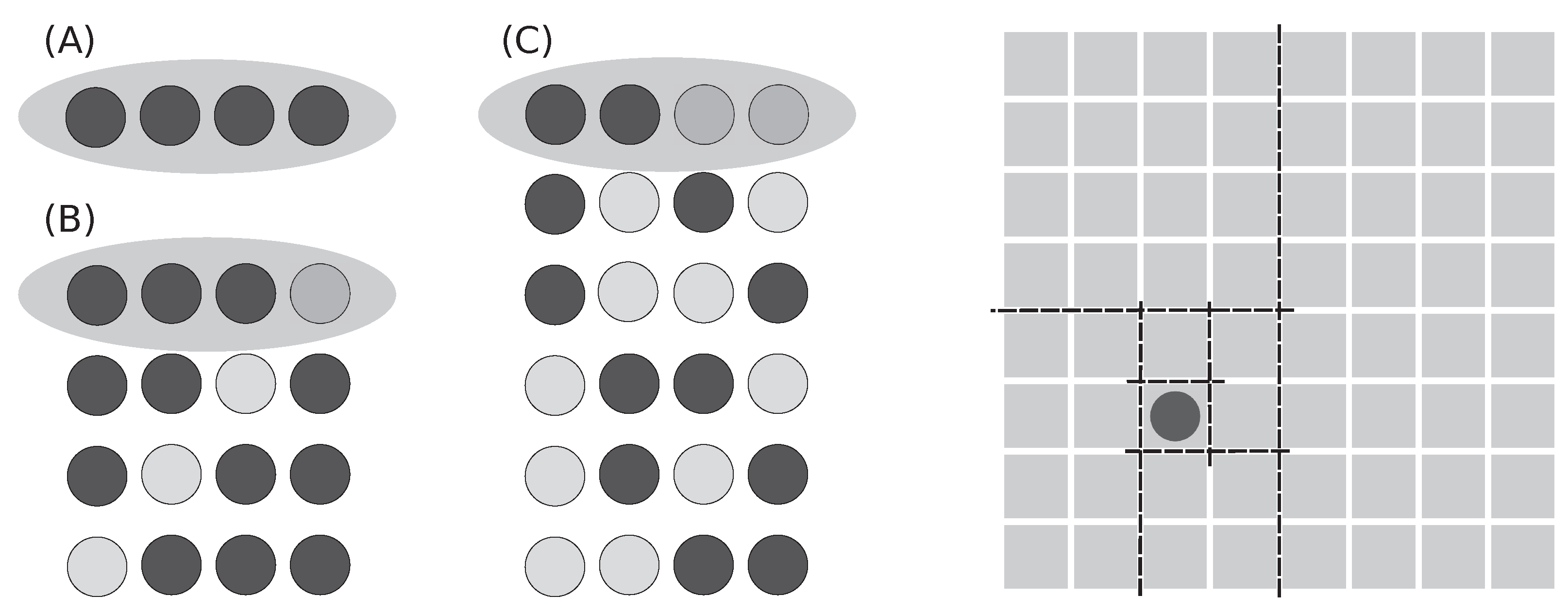

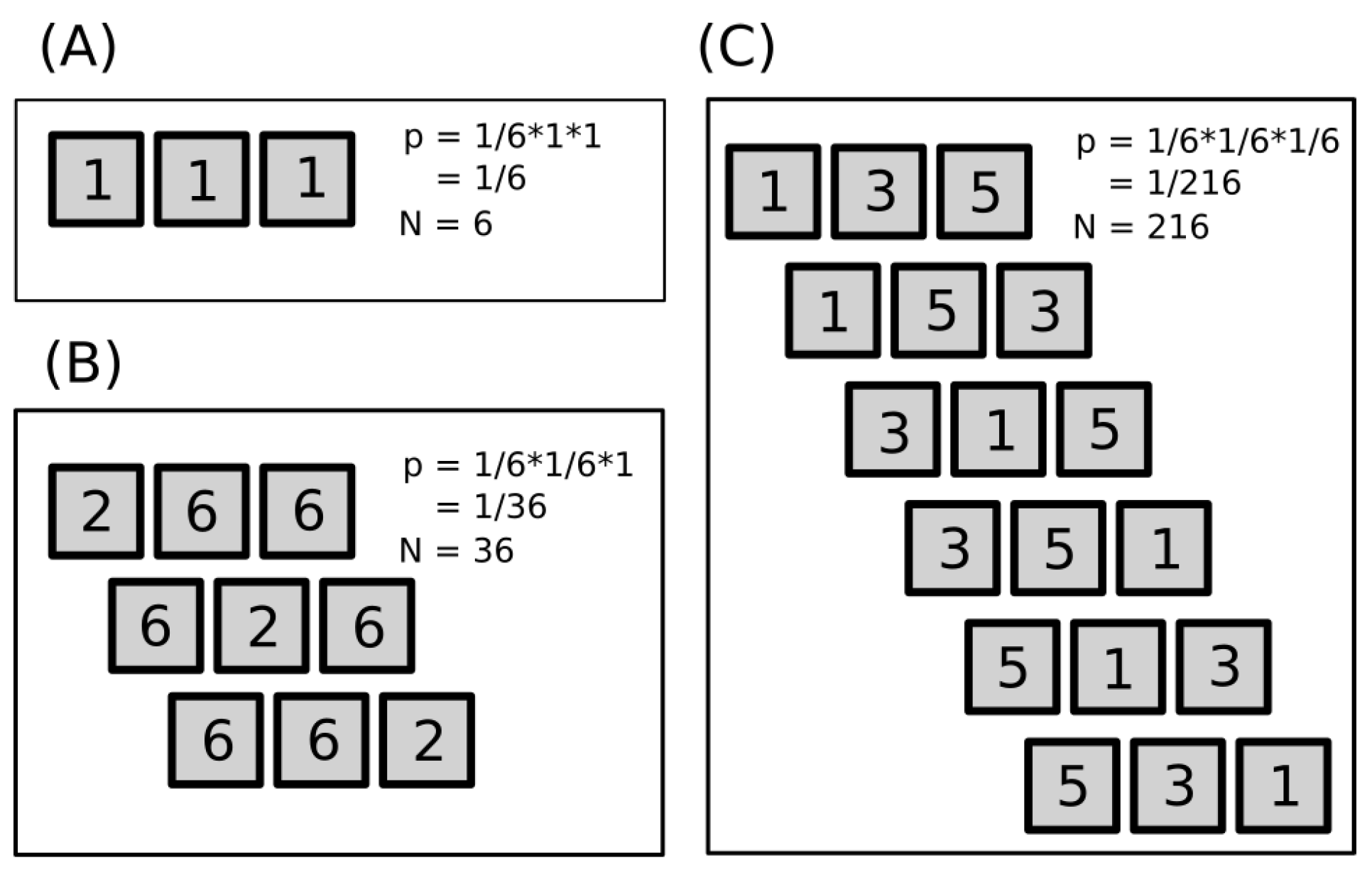

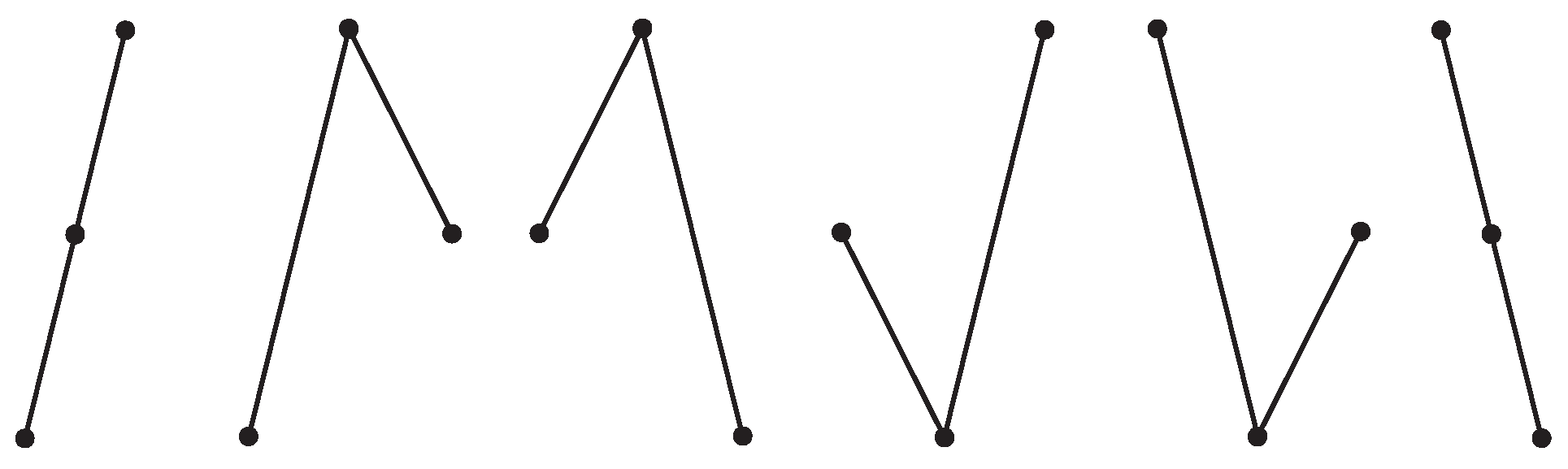

Throws of three dice give richer outputs; see

Figure 1 for three selected examples: 1+1+1, 2+6+6, and 1+3+5 and their combinations. Only the first case (A), 1+1+1, is a pure macrostate. The other two cases in figure (B and C) are subsets of all microstates belonging to macrostates 14 and 9, which contain in total 15 and 25 microstates, respectively (see

Table 2).

Figure 1 demonstrates three basic cases: all dice have identical output (they are dependent), two got identical output, and all three give independent results. The number

p defines the chance of finding a specific configuration for a given case, and the number

N defines the total number of possible outcomes. As the degree of independence rises, the number of possible outcomes substantially increases. Cases with higher independence contain all cases with lower independence.

There are shown some outcomes that belong to three different macrostates (sums) and selected microstates; examples are shown in

Figure 1: (A)

, (B)

, and (C)

. Only case (A) shows all microstates. Cases (B) and (C) contain total 15 and 25 microstates instead of the in-the-figure-shown 3 and 6, respectively; for details, see

Table 2.

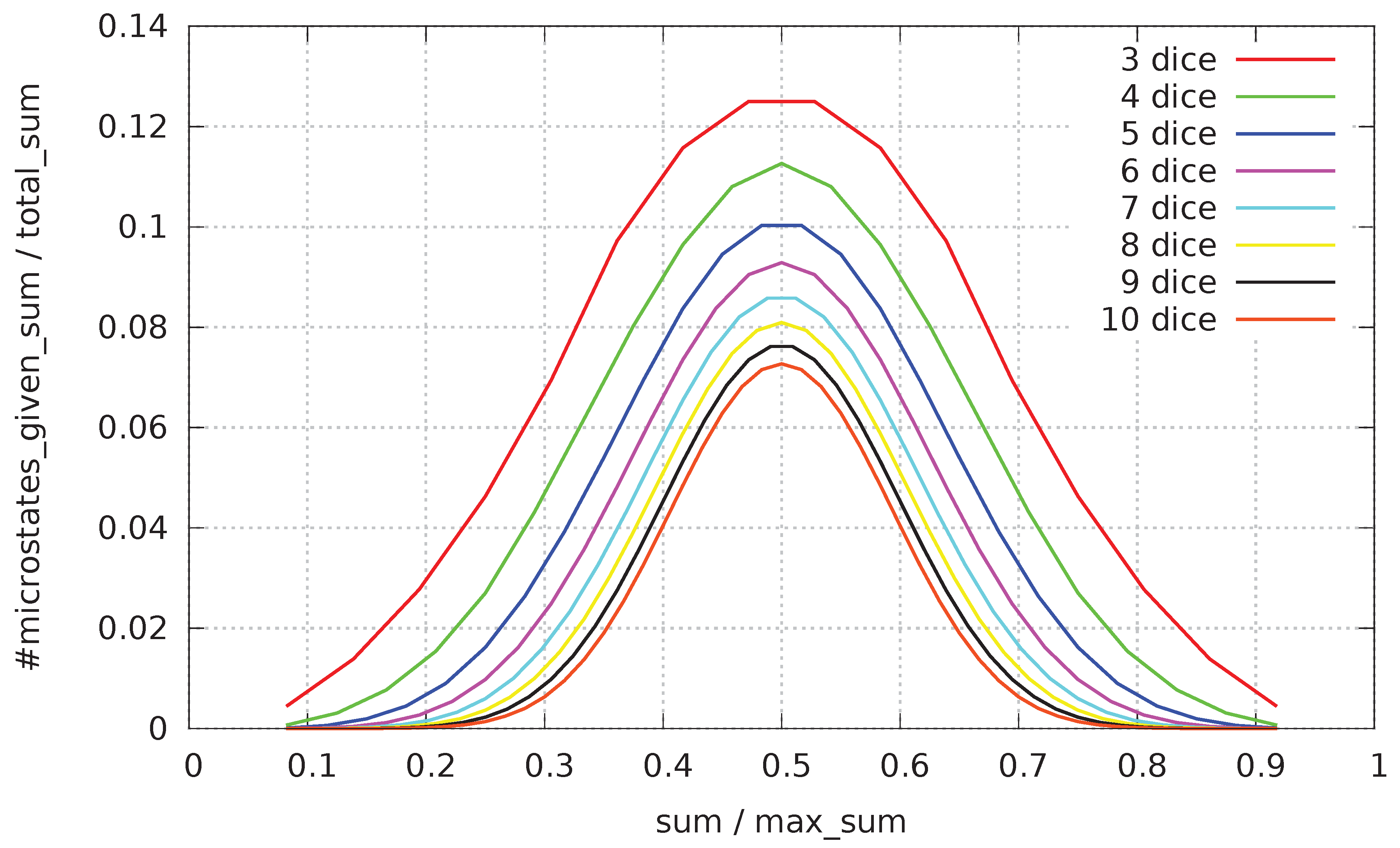

The complete list of all macro- and microstates is provided in the

Table 2, where an obvious tendency of central sums to explode in the number of microstates is occurring. With an increasing number of dice,

N, the central region of the macrostates that contain the majority of microstates gets narrower—it means that majority of dice throws will fall in this region.

When the change of distribution of #-of-microstates with respect to all possible macrostates for three to ten dice is depicted in a graph (see

Figure 2; values are rescaled to make values comparable), there is present an evident tendency of shrinking the region of most often visited macrostates located around the center of all macrostates.

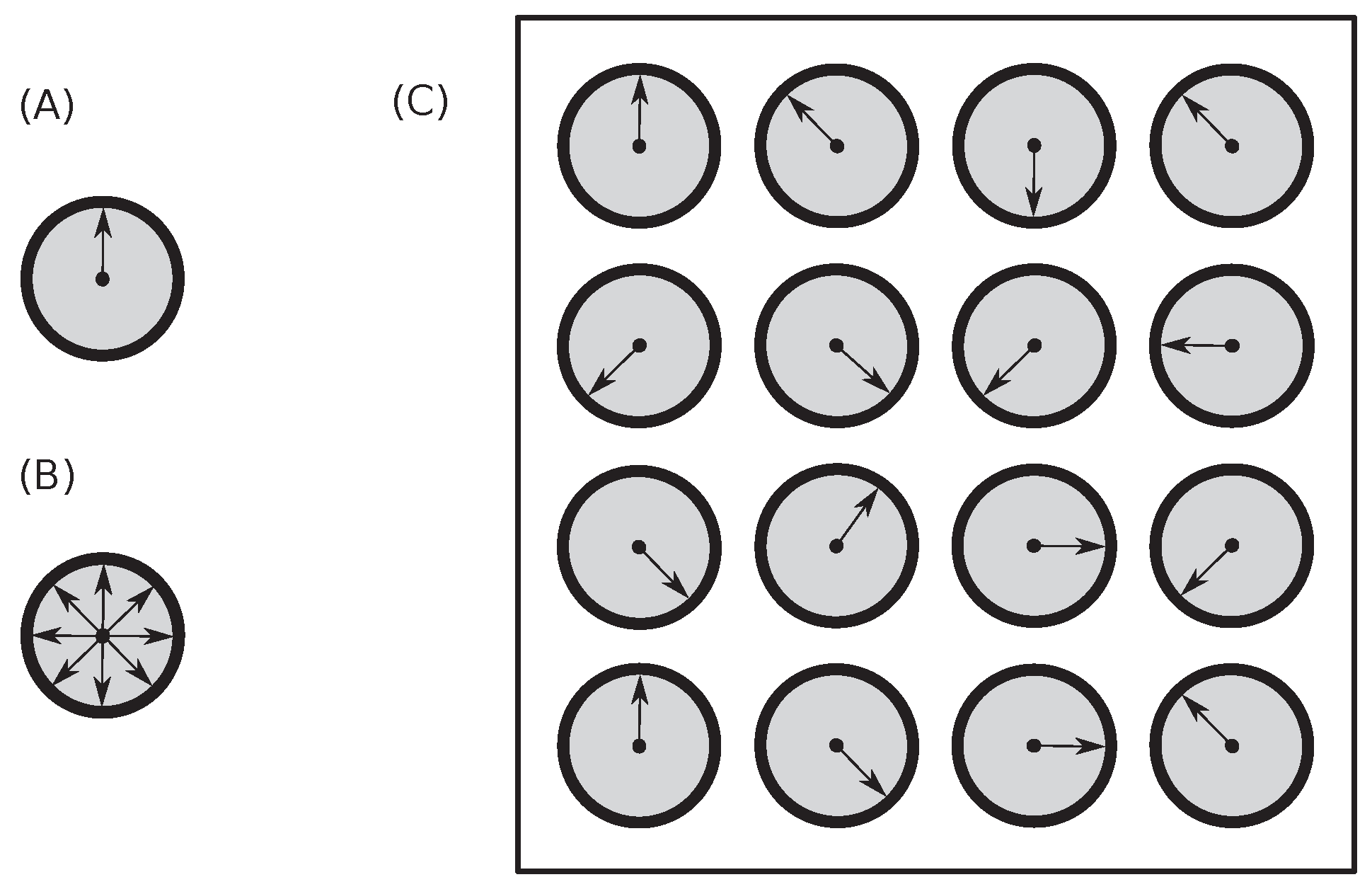

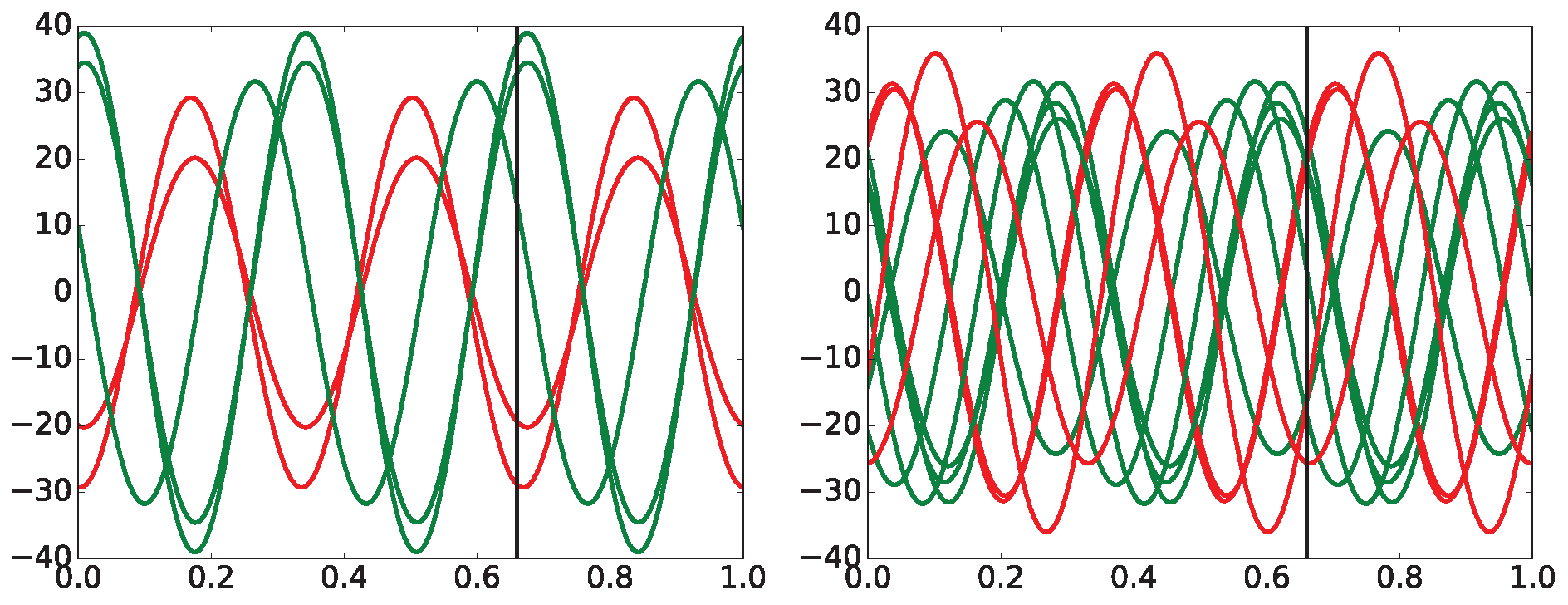

To demonstrate that the principles developed on dice throws can be easily applied to any other physical situations, an example with velocities having eight different directions of particle movements is shown in

Figure 3. We can easily substitute directions with numbers, use eight instead of six numbers, use ’eight-sided dice,’ and study such cases exactly as we did with dice previously.

3.4. Entropy Definition in Statistical Physics

As we already know from

Section 3.2, there is no way to deeply understand the very principles of the 2

nd thermodynamic law from within thermodynamics itself because it treats heat as a continuum. The 2

nd-TL is understood as the absolute law. Within thermodynamics, it is the absolute law as the entropy of an isolated system only increases there.

Ludwig Boltzmann overcame this difficulty [

69,

70,

71,

83] in his seminal research on the kinetic theory of gasses; gas is treated as a collection of atoms there. It was, for this period of time, a revolutionary concept of quantization of physical matter and properties!

The mathematical foundations of kinetic theory of gases—developed by Boltzmann—are covered by mathematics demonstrated in the previous

Section 3.3. Statistical entropy

—is a measure of the number of specific realizations of microstates [

84]—and is defined by the Boltzmann formula [

85] in the form

where

is the Boltzmann constant and

W is the number of microstates attainable by the system. This formula was derived under the assumption that states of the gas are quantized equally according to a function of momentum (

).

As already mentioned, the definition of Boltzmann entropy relies on the atomic structure of gas and, in general, on the discreteness of the studied phenomenon.

It is easily seen that entropy is proportional to the amount of missing information. More indistinguishable microstates leading to a given macrostate means greater uncertainty (a constant system gives

, whereas white noise, where all states are visited equally, gives

). The importance of this formula lies in the fact that it can be used not only in physics but also in communication, sociology, biology, and medicine. To be able to use this entropy formula, the following requirement must be fulfilled: all

W states of the system (called in physics the micro-canonical ensemble) have to have equal probabilities. In such a case, it leads to probabilities

(for all

). Entropy

described in Equation (

2) can be rewritten using this assumption into the following form

When the condition of equal probabilities

is not fulfilled, an ensemble of micro-canonical subsystems is introduced with the property that within each

th of the subsystems

all probabilities are equiprobable. Averaging Boltzmann entropy

under those assumptions leads to Gibbs-Shannon entropy

where

defines averaging over probability

p. Such derivation of Gibbs-Shannon entropy

is often seen in textbooks [

86,

87]. This entropy is commonly used in statistical thermodynamics and in information theory; see the next subsection for details on information entropy.

Let us briefly review the historical development of the mathematical formulation of entropy [

69,

70,

71,

83] as it can be applied in other research areas, including biology & medicine, when understood correctly. Firstly, Boltzmann derived the H-theorem dealing with molecular collisions of atoms, which decreases in isolated systems and goes towards an equilibrium (it is also called the minimum theorem). Secondly, he proved that any initial atomic configuration reaches an equilibrium with time. This equilibrium approaches a specific distribution of atomic velocities, which depends on temperature, and is called the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution.

Kinetic theory of gases explained the notion of pressure and temperature contrary to all previous continuous approaches. Additionally, Boltzmann proved that Quantity H behaves similarly to entropy except for a constant! His ideas were perceived as too revolutionary by his colleagues for the given level of understanding of physics. He had been repeatedly attacked by many leading physicists in his era. Their reason was an assumption that perfectly reversible atomic movements cannot lead to the irreversibility of H quantity!

A big fight was focused around the following discrepancy: deterministic movements of atoms leading to reversibility of their movements versus stochastic irreversibility of their ensembles. Boltzmann poured even more oil in the fire when he said that

-TL is not absolute and in some cases entropy can spontaneously decrease from purely statistical reasons—exactly as we saw in the

Section 3.3. He said, "most of the time entropy increases but sometimes decreases, and hence,

-TL is not absolute." His work became a cornerstone of the foundations of modern physics and, subsequently, many other scientific disciplines, including biology. It gave impetus to the quantization of quantum physics.

3.5. Entropy Definition in Theory of Information

The notion of information was introduced by Claude Shannon to quantitatively describe the transmission of information along communication lines [

45,

46]. This concept later become useful in other scientific disciplines: linguistics, economics, statistical mechanics, complex systems, psychology, sociology, medicine, and other fields. It was shown by Shannon that entropy known from statistical physics is a special case of information entropy (often called Shannon entropy).

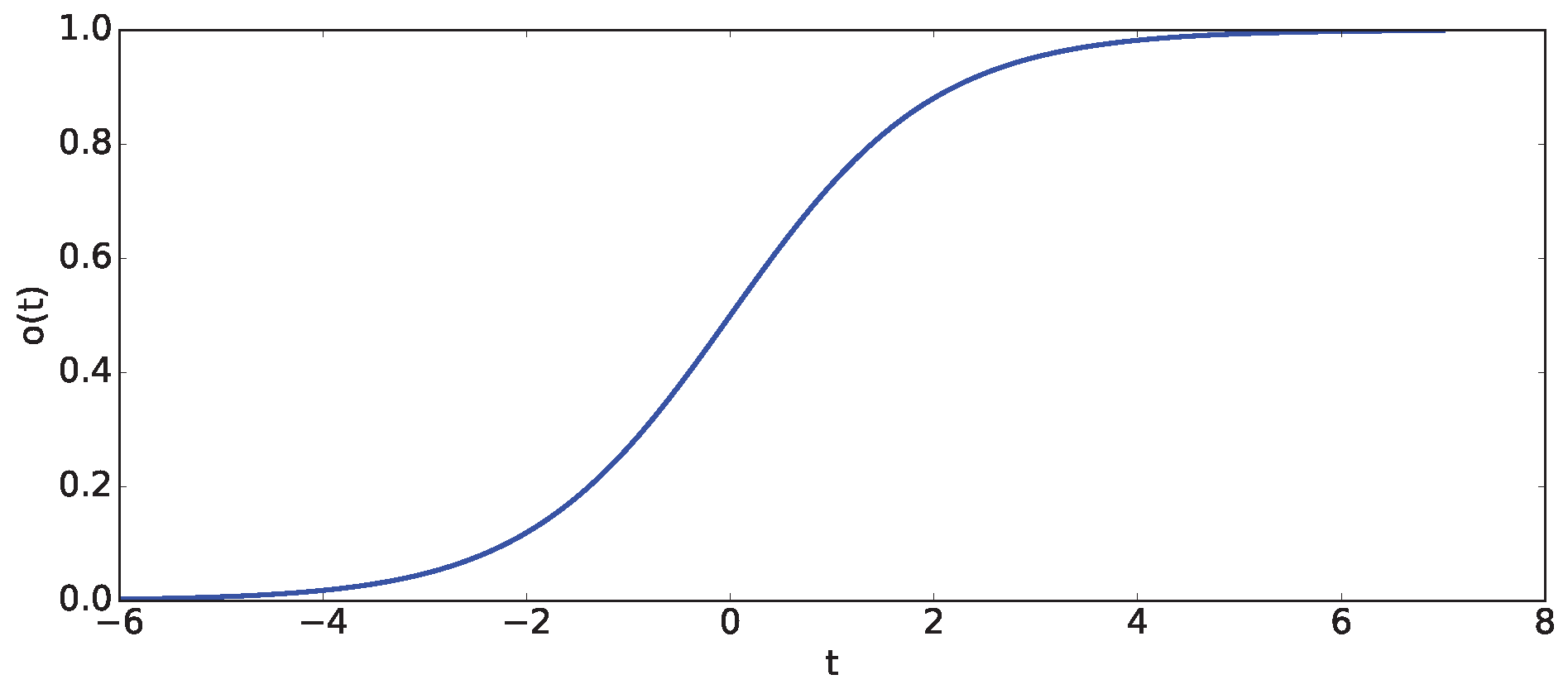

Figure 4.

(Left) Balls can help us understand the amount of missing information (which is equal to entropy): (A) All balls are same, which leads to zero entropy (1 config). (B) 3+1 balls have higher entropy (4 configs). (C) 2+2 balls give the highest entropy (6 configs). It is seen from the numbers of depicted, possible configurations. (Right) One square of a chessboard made of squares is hiding one nugget of gold. How many questions do we need to find out where it is hidden by splitting the region into two parts repeatedly? We need exactly six questions—it means six bits of information—while using splitting in halves. Otherwise, we need more.

Figure 4.

(Left) Balls can help us understand the amount of missing information (which is equal to entropy): (A) All balls are same, which leads to zero entropy (1 config). (B) 3+1 balls have higher entropy (4 configs). (C) 2+2 balls give the highest entropy (6 configs). It is seen from the numbers of depicted, possible configurations. (Right) One square of a chessboard made of squares is hiding one nugget of gold. How many questions do we need to find out where it is hidden by splitting the region into two parts repeatedly? We need exactly six questions—it means six bits of information—while using splitting in halves. Otherwise, we need more.

Let us introduce the amount of missing information on one example. We have a chessboard with squares where one square is hiding a golden nugget. The problem is to localize a given square by giving questions. What is the best strategy to find it? It is possible to guess which square is hiding the nugget. It might take up to 63 questions to find it: not so good a strategy. We can divide the board into two unequal parts and ask which one is hiding the nugget. It is definitely a better strategy: in the worst case, the output is approaching the speed of the previous case. What about halves? Yes. When we split the board into decreasing halves, the fastest localization of the nugget is found. It takes just steps to arrive at the final result each single time!

From this explanation, it is easily seen that the amount of missing information is equal to the number of questions necessary to localize information. As shown above, the gain from the smart way of questioning is maximal. Gain of information is one bit. Maximal information gain is in the case when two parts are equal. Contrary to it, asking one square after the other requires a tremendous number of questions.

Shannon entropy

where probabilities of all

W events are equiprobable, gives the following formula

There are W events, each having a probability of , giving . This can be simplified by making sum over equiprobable states that leads to .

Shannon entropy

where probabilities of events are unequal

must be split into different parts having the same probabilities that lead to the following formula

In this case, the sum

cannot be removed from the formula as is done in the previous case.

In the seminal work of Shannon [

45,

46], the measure of the amount of information

contained in a series of events

was derived under the assumption that it satisfies three requirements:

should be continuous in the .

When all are equally probably, so , then is increasing function of N.

should be additive.

This led to the famous Equation (

6) because the above-provided assumptions yielded only this formula.

Information entropy and its applications are described in the following publications [

29,

30,

36,

37], where the topic is discussed with different levels of background requirements and where many examples are shown. Shannon entropy and its relationship to many scientific disciplines deserves more space, which we do not have here, because it is representing the root concept that is very useful in complex systems and many other disciplines.

3.6. Applications of Information Entropy in Biology and Medicine

As we already know, many natural systems, including complex ones, are beyond our capabilities to trace all their constituting parts in every detail. It was found that such tracing is not necessary for the correct description of macroscopically observed responses in complicated systems that acquire tremendous numbers of microstates. The concept of entropy demonstrated itself as very useful in the description of complex systems, in which detailed knowledge of their microstate configurations is not necessary for the description of macroscopic behavior. The usefulness of this approach was confirmed in the description of physiological processes operating within the bodies of animals and humans [

13].

The obstacle in employment of entropy in description and prediction of biological systems is our insufficient ability to produce mapping of the complex system into the bins used in entropy. We must be able to find the best possible way of doing this mapping. None of the developed entropy measures is perfect—each of them has own pros and cons. There exist many approaches enabling the measurement of the complexity observed in biomedical systems using various types of information entropy: ApproxEn [

13,

38,

39], SampEn [

13], PeE [

40], multiscale entropy [

15,

41,

42], and others [

28,

43]. Permutation entropy (PeE) is used in this study to acquire data that are distributed in bins; see detailed explanation in

Section 6.2.

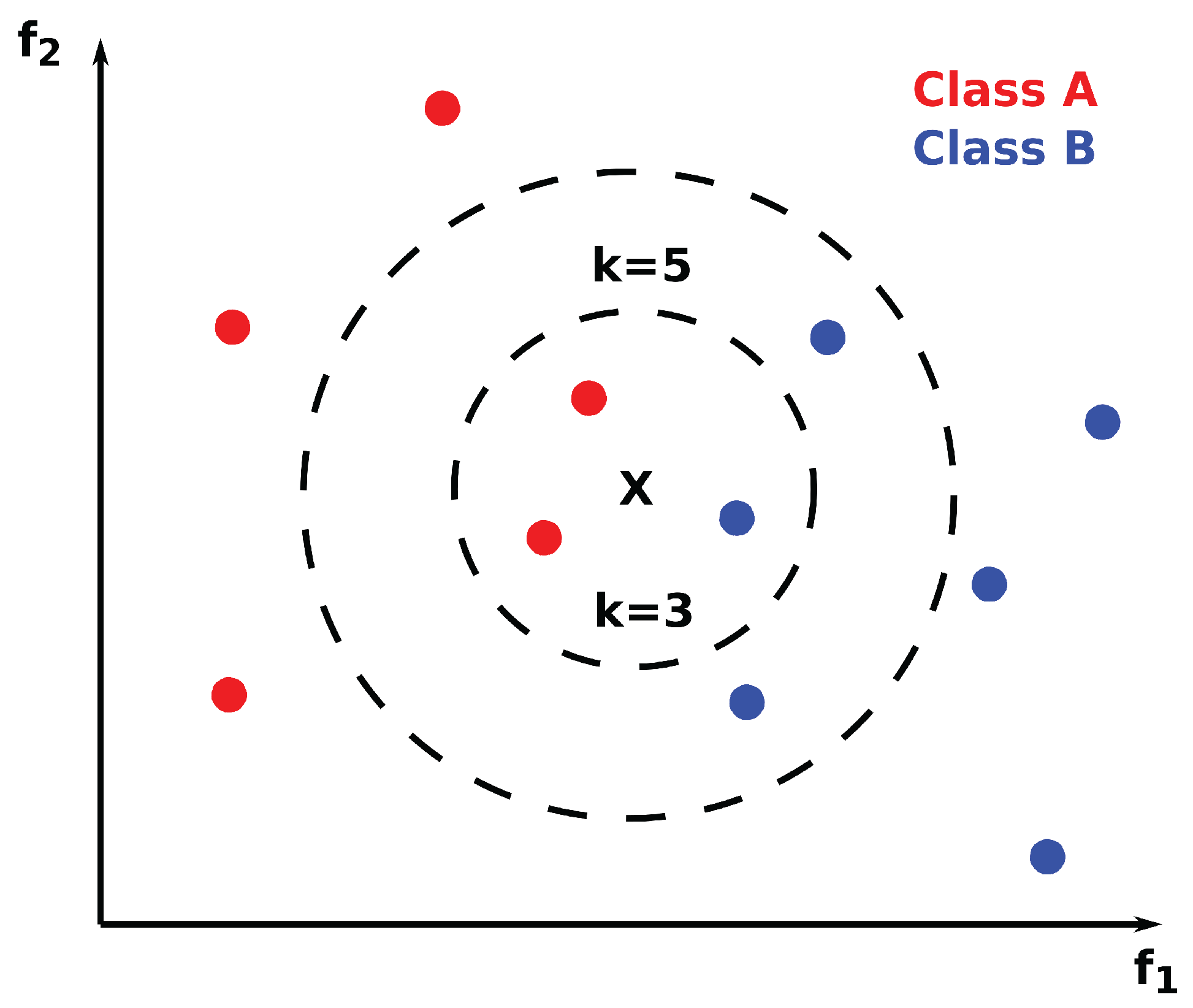

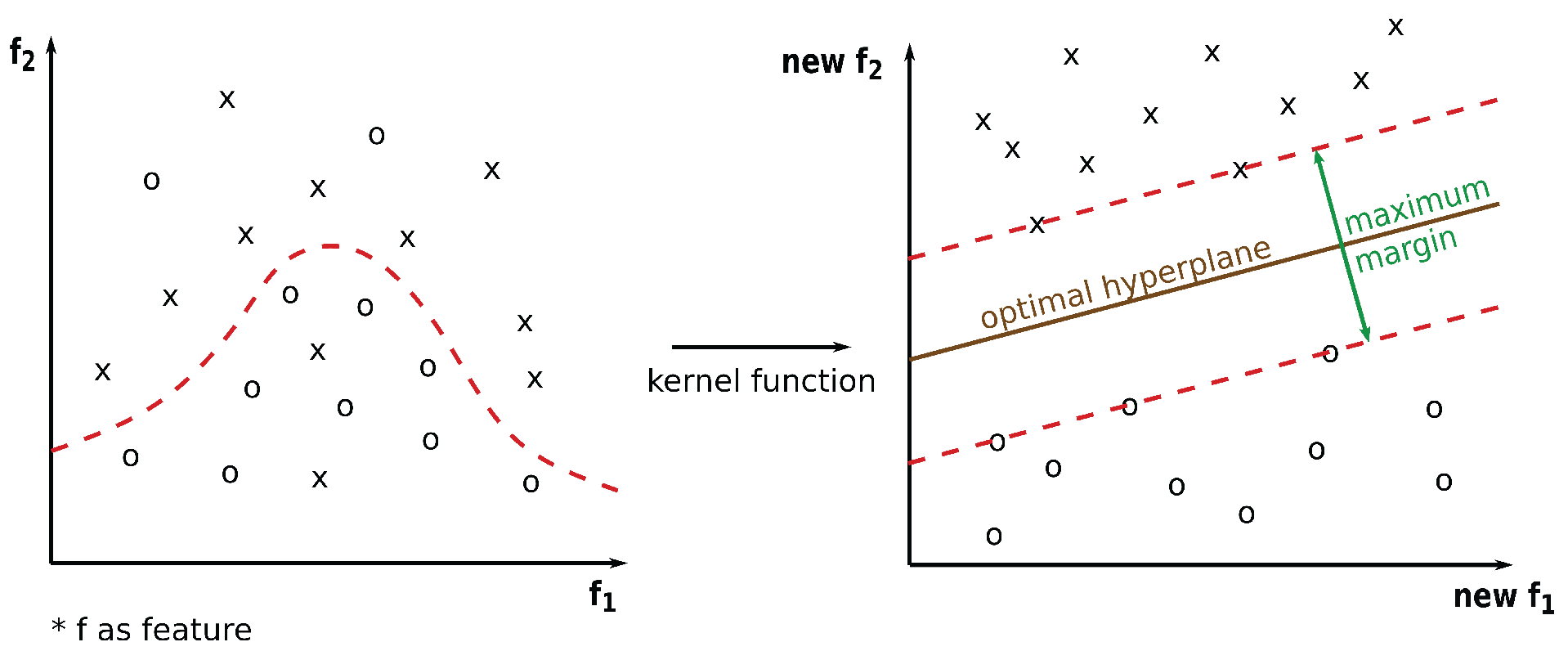

4. Results–Part 1: Comparison of ’Normal’ with ’Non-TdP + TdP’ Rabbits

This section deals with the following grouping of tested rabbits: Torsades de Pointes (TdP) and non-TdP arrhythmia-acquiring rabbits (called arrhythmogenic) are included within one group, which is compared with the second group of rabbits that do not acquire any arrhythmia (called normal). Beware, later, in the next Results Section, see

Appendix C, non-TdP arrhythmias acquiring rabbits will be excluded, and hence, only rabbits acquiring TdPs with those non-responsive (normal) will be compared there: discussion section will explain the details. Hence, it is necessary to be careful in comparing those two results sections!

Inclusion of both sub-groups in one group is done because ECG changes are expressing very similar features (definition follows) in both cases: TdP and non-TdP arrhythmia. A feature is defined as a measurable characteristic or property of the observed phenomenon. The selection of the most important features is crucial for building a highly predictive model. Simply said, we can suspect that all those rabbits showing double or triple subsequent PVCs—ectopic activity originating in the ventricles—can acquire TdPs, VTs, or VFs in the next hours or days. Authors of the experimental study [

52] did not test this possibility (it was personally discussed with [

88,

89] by J.K. several times.) Firstly, in both cases (TdP and non-TdP) are displaying similar changes of T-waves: their broadening and increase of the amplitude that become comparable to the height of QRS complexes. Such morphological changes of ECG recordings are present a long time before the onset of a TdP arrhythmia; their presence is crucial. Secondly, TdP and non-TdP arrhythmia express a very similar pattern in the generation of double or triple subsequent PVCs at the stage where the T-wave becomes broad and high. This gives a consistent picture of the onset of an unstable substrate within the heart’s wall that is triggering twins (bigemini activity) and triplets (trigemini activity) of premature ventricular contractions (PVCs), which are sometimes called extra-systoles, because they are not preceded by an atrial contraction.

The search for the best mathematical method capable to visualize changes on ECGs capturing the development of TdPs was from the very beginning aimed towards the application of entropy measures of the original, unfiltered signals; see

Section 2 and

Section 3. This phase took the longest time as it was necessary to develop a wide and deep overview of complexity in medicine—the result is covered and reviewed in [

63,

68] and serve as an introduction onto this research. Permutation entropy [

56] was selected as the most suitable entropy that can be applied to this problem. Immediately after the evaluation of permutation entropy, it was evident that outputs are very rich in information. Unfortunately, as was expected and shown later in this section, common statistical methods [

76] applied by J.K. failed to reveal hidden correlation between computed permutation entropy and presence/lack of arrhythmia. Hence, it was decided to apply machine learning (ML) methods to automate the entire process of the best hypothesis search; see

Section 2 for the motivation; see

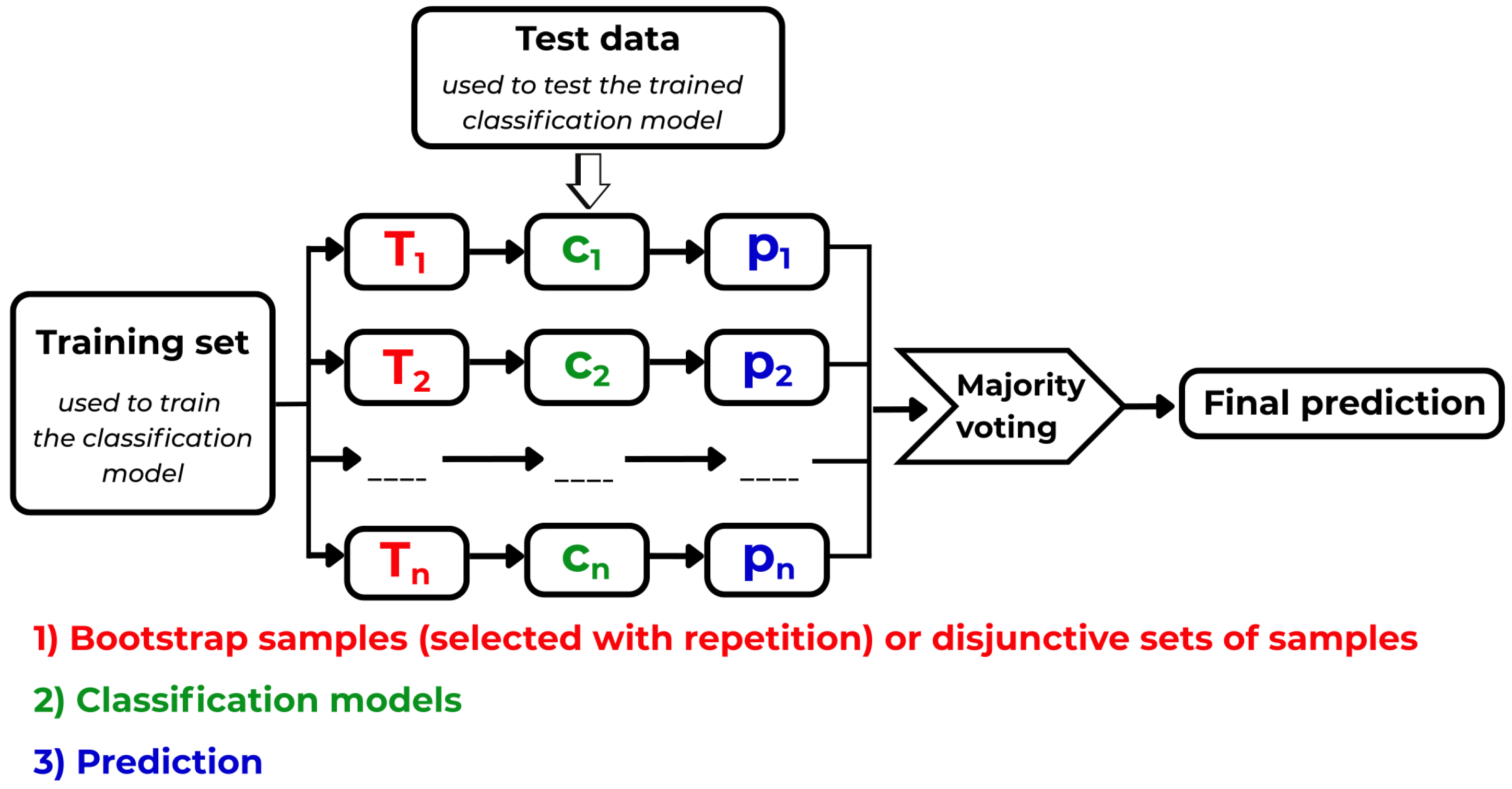

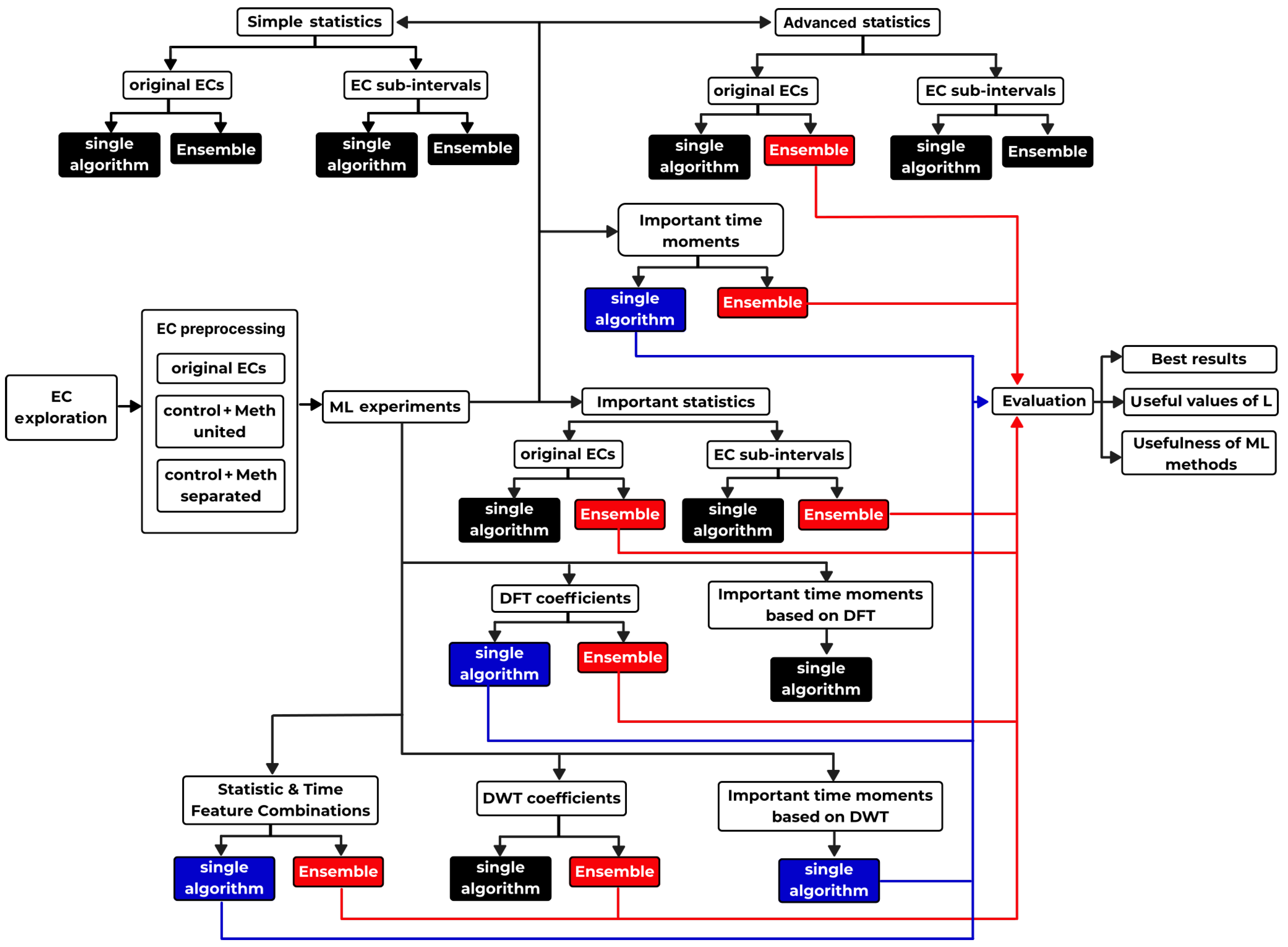

Table 3 for a brief description of all tested approaches.

The research done on finding the best up-to-date ML methods, which are capable of predicting arrhythmia with the highest scores, was very thorough, wide, and deep [

90]. Authors decided to provide this information as a part of the paper for methodical reasons. It can enable everyone to conduct similar research in other areas of the biosignal processing, where ML methods might become more successful compared to the application of common statistical techniques. The sequence of all steps performed during the search for the best ML methods is explained in

Section 4.8 and depicted in the picture in

Appendix A.1. In order to enable the reader easily orient in the search, this section has the following structure: description of major types of arrhythmia, permutation entropy evaluation algorithm, permutation entropy (

) of rabbit ECG recordings, selection of sub-intervals of

, feature selection, simple and advanced statistics, ML experiments, and ML results.

4.1. Description of Major Arrhythmia Types as Seen on ECG Recordings of Humans and Their Curves: TdP, VT, VF, and PVC in Contrast with Normal Ones

To provide a medical perspective to this position paper, real human ECG recordings: normal, Torsades de Points (TdP), ventricular tachycardia (VT), ventricular fibrillation (VF), and premature ventricular contractions (PVC) are presented in this subsection. Rabbit ECG recordings look quite similar.

A reliable prediction of life-threatening arrhythmias is the question of life and death in many cases; for example, heart diseases, guarding consciousness of professional drivers and airplane pilots, sportsmen, or hospital settings. In the following are presented samples of different types of naturally observed arrhythmias as observed on ECG recordings of humans along with the respective changes, if any exist, on PeE curves. This enables even non-specialists to visually recognize those serious, life-threatening arrhythmias; see their brief description in

Table 4 and depictions in

Figure 7,

Figure 8,

Figure 9, and

Figure 10. Make sure to compare those arrhythmia recordings with the sample of the normal ECG recording

Figure 6.

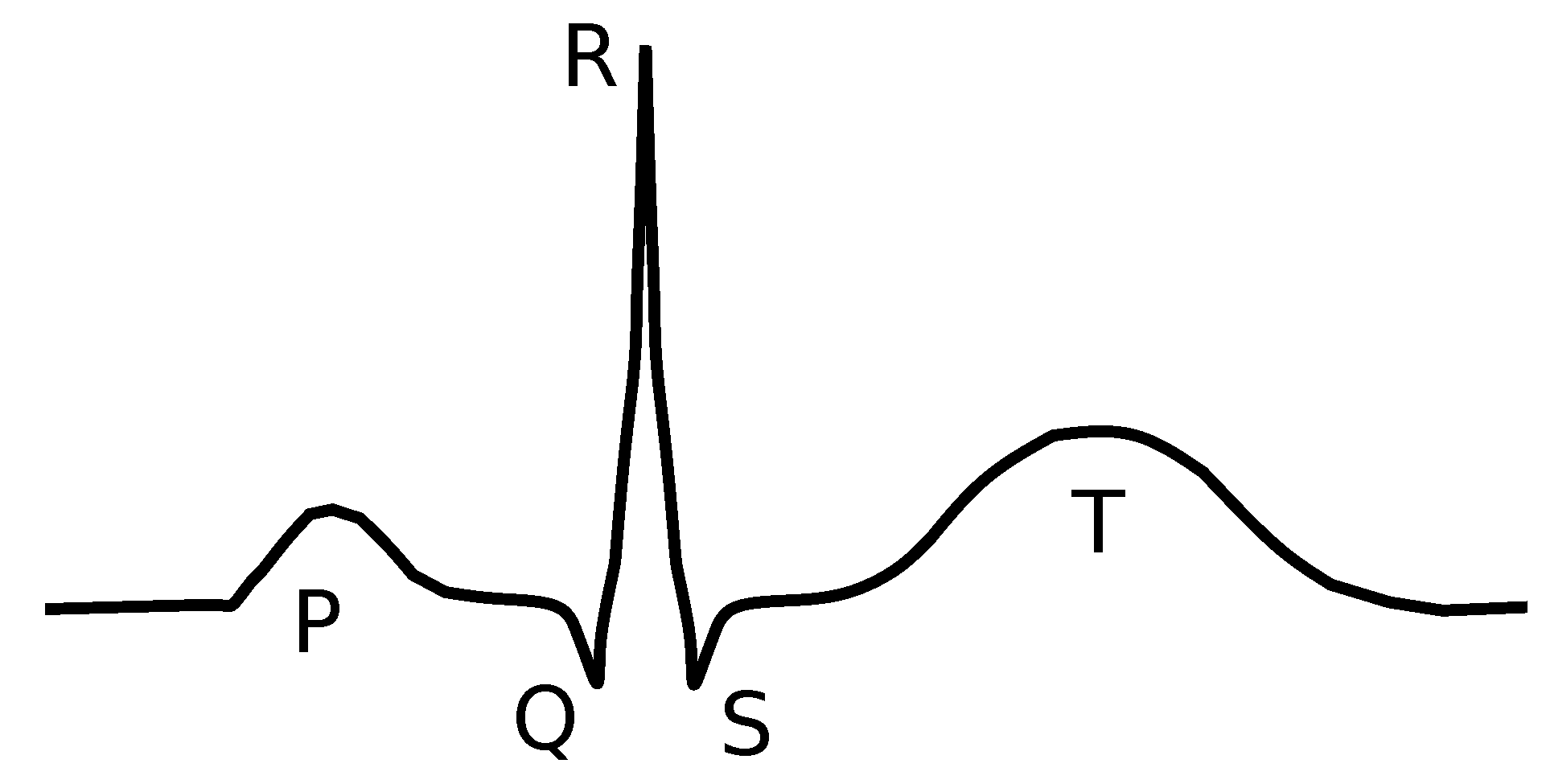

Figure 5.

A schematic depiction of one heart beat as seen on an ECG recording. The sequence of P-QRS-T is divided as follows: P-wave represents contraction of atria, QRS-complex contraction of ventricles, and P-wave repolarization of ventricles (repolarization of atria is covered by QRS complex). The normal ECG recording of a healthy rabbit is shown in

Figure 6.

Figure 5.

A schematic depiction of one heart beat as seen on an ECG recording. The sequence of P-QRS-T is divided as follows: P-wave represents contraction of atria, QRS-complex contraction of ventricles, and P-wave repolarization of ventricles (repolarization of atria is covered by QRS complex). The normal ECG recording of a healthy rabbit is shown in

Figure 6.

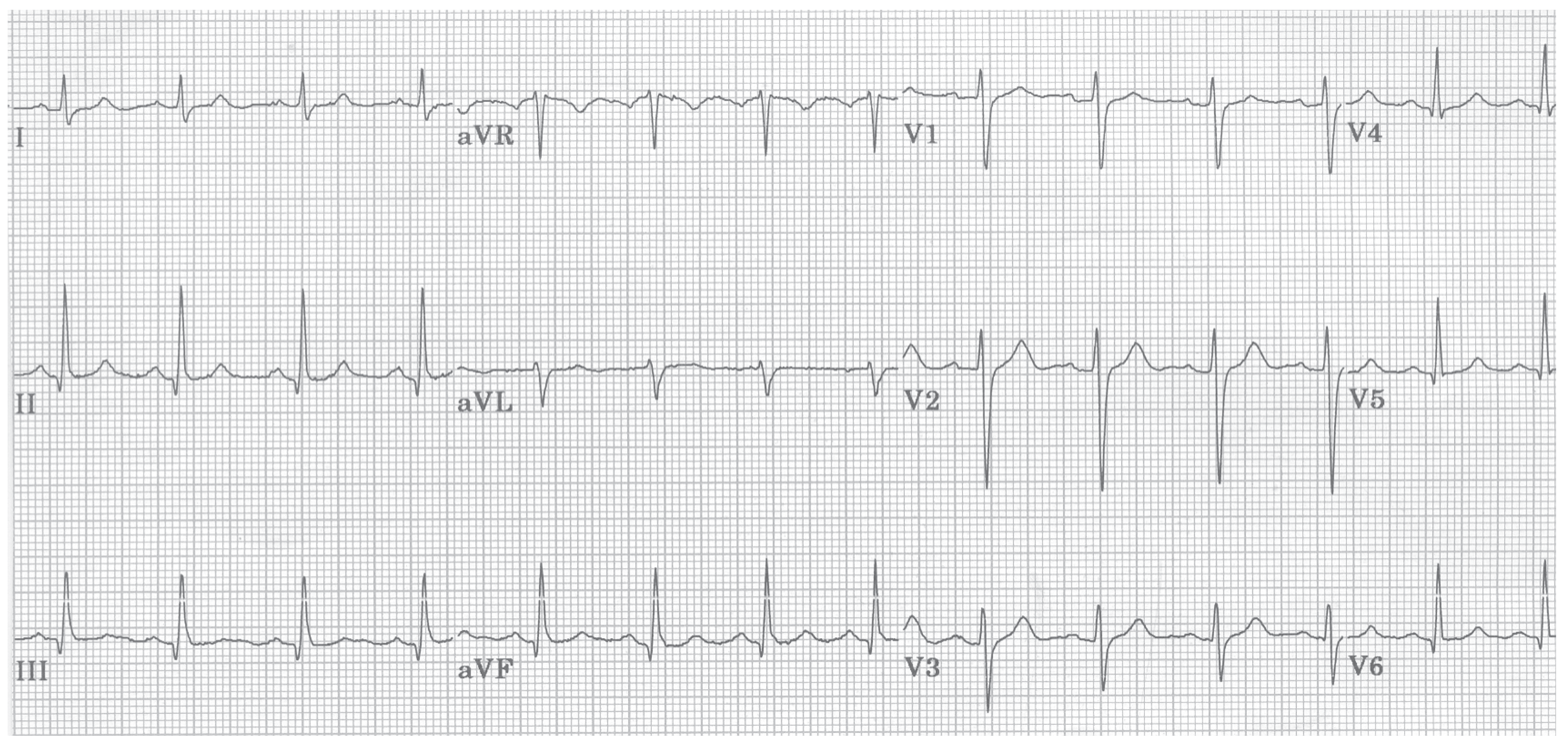

To make a good reference ECG curve,

Figure 6 depicts the case of the standard ECG recording of a healthy person, which is called in the following text the normal ECG recording. It clearly shows the standard sequence of atrial contraction (P-wave), ventricular contraction (QRS-complex), and ventricular repolarization (T-wave). The schematic depiction of a normal heart contraction, as observed on ECG recordings, is depicted in

Figure 5.

Figure 6.

A normal ECG recording of a human is providing the baseline to all arrhythmias shown in the subsequent figures. A normal ECG curve always contains a P-wave, a QRS complex, and a P-wave. All the subsequent graphs, which are depicting arrhythmia recordings, show distorted ECG curves; courtesy of [

91].

Figure 6.

A normal ECG recording of a human is providing the baseline to all arrhythmias shown in the subsequent figures. A normal ECG curve always contains a P-wave, a QRS complex, and a P-wave. All the subsequent graphs, which are depicting arrhythmia recordings, show distorted ECG curves; courtesy of [

91].

Torsades de Pointes arrhythmia is typically triggered when the QT interval, which is measured between Q and the end of the T-wave, exceeds a certain threshold; in humans, it is 500 ms. In such cases, it can happen that partially recovered cardiomyocytes after excitation can be excited again. This leads to the occurrence of an unnatural, meandering pacemaker focal point in ventricles instead of in the atrium, which subsequently triggers an arrhythmia that is quite often fatal.

Figure 7.

Torsades de Pointes (TdP) arrhythmia of a human, which is typically induced by drugs, both medical and recreational, affects the functioning of ion channels that, in turn, change the propagation speed of the action potential through cardiomyocytes. As seen from the figure, ECG recordings have sinusoidal shape of the envelope following the maxima of the ECG curve. TdP often degenerates into a life-threatening VT or VF; courtesy of [

91].)

Figure 7.

Torsades de Pointes (TdP) arrhythmia of a human, which is typically induced by drugs, both medical and recreational, affects the functioning of ion channels that, in turn, change the propagation speed of the action potential through cardiomyocytes. As seen from the figure, ECG recordings have sinusoidal shape of the envelope following the maxima of the ECG curve. TdP often degenerates into a life-threatening VT or VF; courtesy of [

91].)

Ventricular tachycardia is typically triggered by either morphological disturbance(s) or by dispersion of velocities of action potential propagation through ventricles; it has normally shape of a distorted sinus curve. It triggers self-sustainable excitable focus that replaces the natural pacemaker located in the atria. Frequencies of VT typically lie within the range of 130-250 bpm. With increasing frequency of VT, ejection fraction of expelled blood from the heart decreases substantially. Above 200 bpm, such arrhythmia when generated in ventricles is typically classified as ventricular fibrillation by automatic defibrillators despite it still being a VT run. Ventricular fibrillation is seen as an uncoordinated, random noise on ECG recording.

Figure 8.

An ECG recording of ventricular tachycardia (VT) of a human looks like a deformed sinusoidal curve (due to aberrated QRS-complex) of fixed maximum height. The heart’s ejection fraction (the volume of ejected blood) is substantially decreased during VT; an affected body can cope with such arrhythmia for some period of time but often does not; courtesy of [

91].

Figure 8.

An ECG recording of ventricular tachycardia (VT) of a human looks like a deformed sinusoidal curve (due to aberrated QRS-complex) of fixed maximum height. The heart’s ejection fraction (the volume of ejected blood) is substantially decreased during VT; an affected body can cope with such arrhythmia for some period of time but often does not; courtesy of [

91].

Figure 9.

During a ventricular fibrillation (VF) of a human the ECG recording is randomly going up and down in a completely uncoordinated fashion. The heart’s ejection fraction is reaching zero value during VF and quickly leads to a condition incompatible with life; courtesy of [

91].

Figure 9.

During a ventricular fibrillation (VF) of a human the ECG recording is randomly going up and down in a completely uncoordinated fashion. The heart’s ejection fraction is reaching zero value during VF and quickly leads to a condition incompatible with life; courtesy of [

91].

Figure 10.

Premature ventricular contractions (PVC), a.k.a., extra-systoles, look like a single oscillation of a VT run with a missing P-wave. Actually, replacement of SA-node pace-making activity by an ectopic center(s) in ventricles is the same in both cases. PVCs occur sporadically even in healthy people; courtesy of [

91].

Figure 10.

Premature ventricular contractions (PVC), a.k.a., extra-systoles, look like a single oscillation of a VT run with a missing P-wave. Actually, replacement of SA-node pace-making activity by an ectopic center(s) in ventricles is the same in both cases. PVCs occur sporadically even in healthy people; courtesy of [

91].

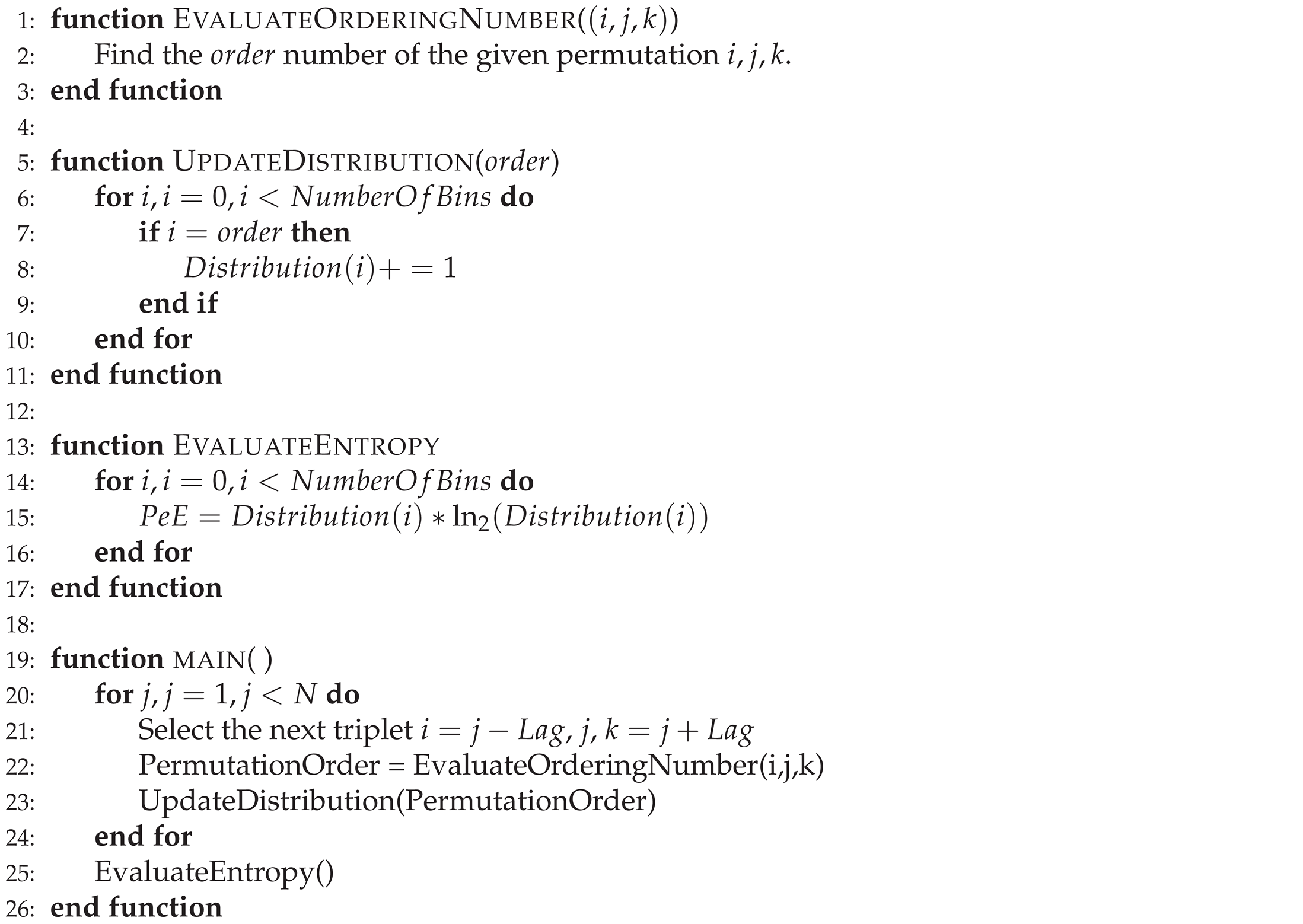

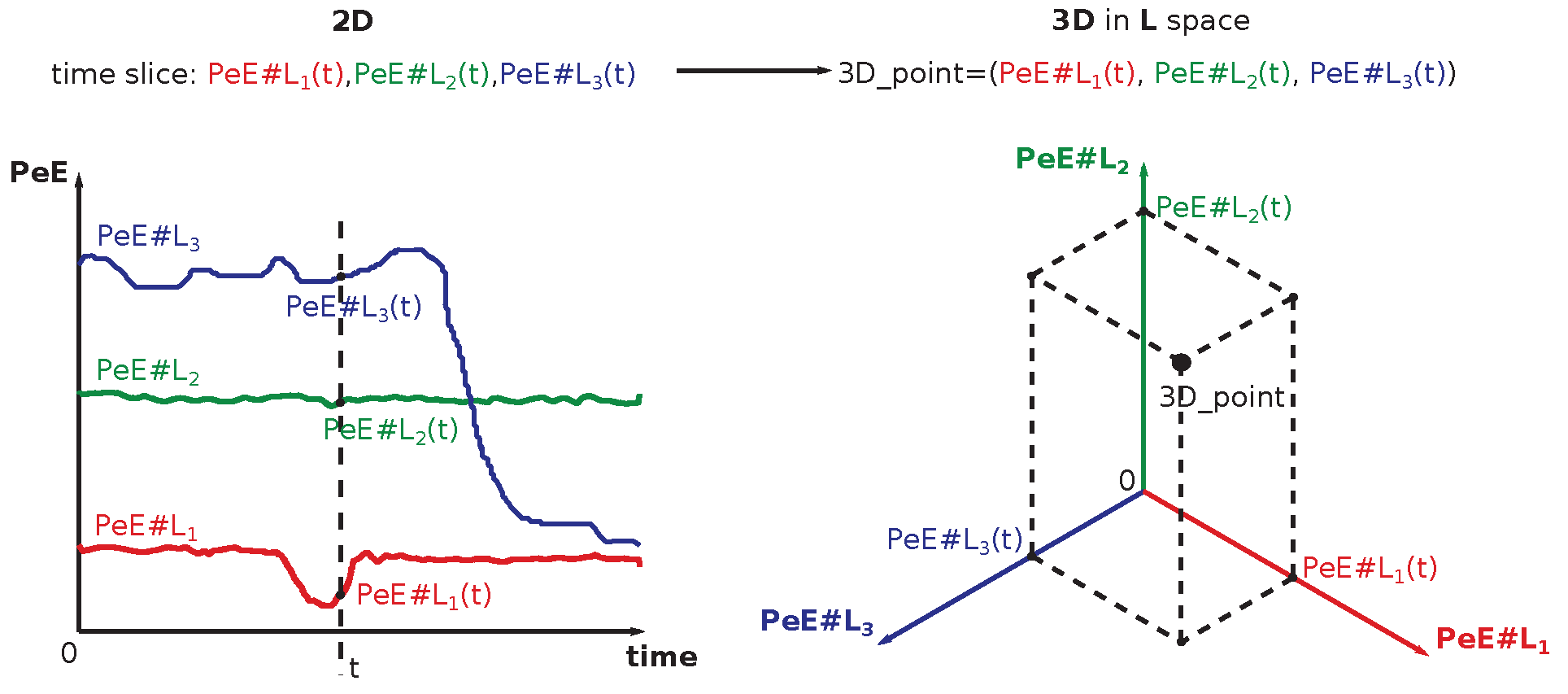

4.2. Algorithm and Graphic Depiction Describing Evaluation of Permutation Entropy: Allowing Easy Orientation in Following Results

For a better understanding of the role that permutation entropy (PeE) is playing in deciphering hidden processes that are operating within complex systems, it is necessary to acquire a basic understanding of the PeE evaluation. For this reason, the following brief introduction to PeE is provided. The rigorous definition of PeE is found in

Section 6.2.

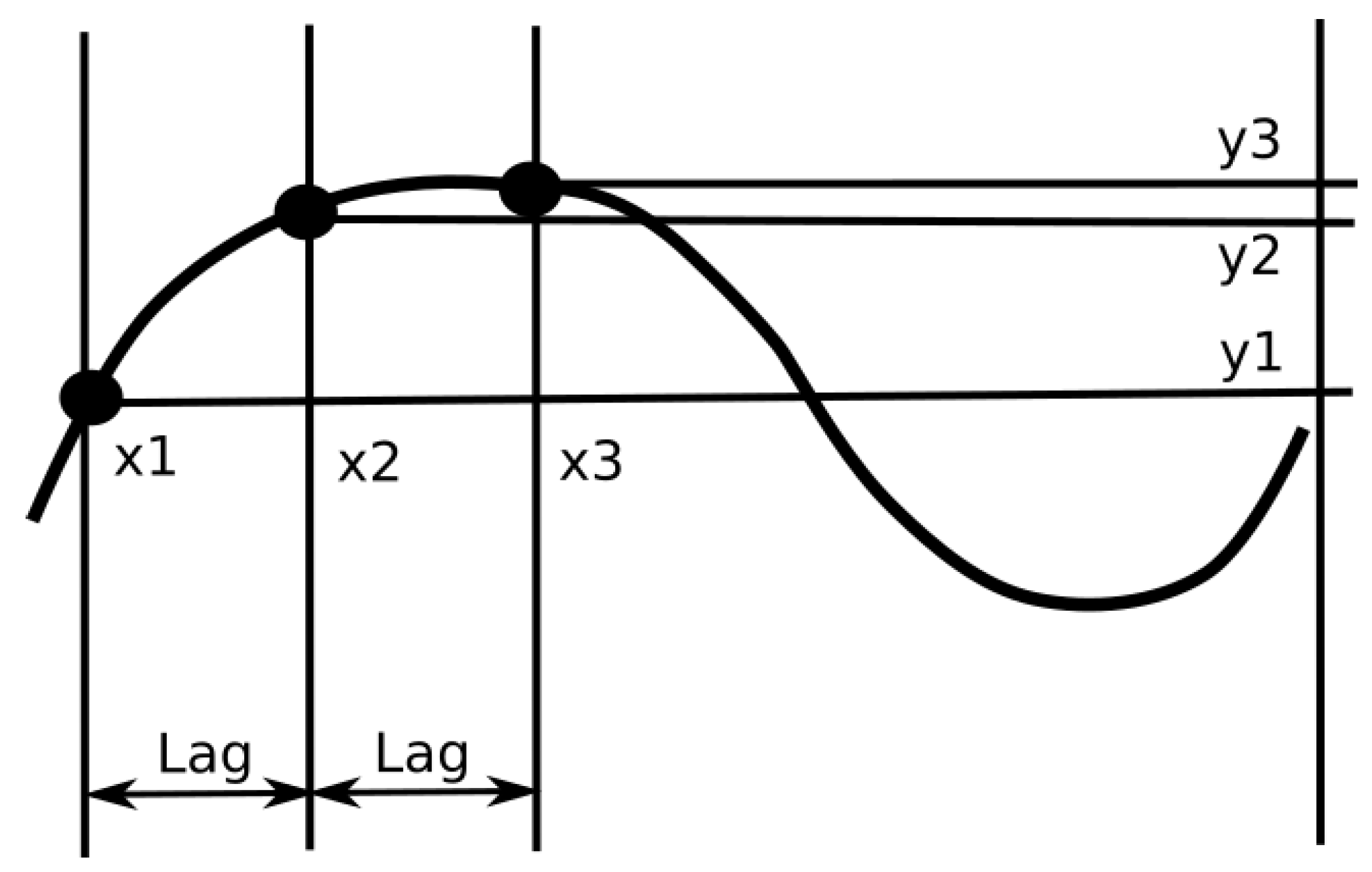

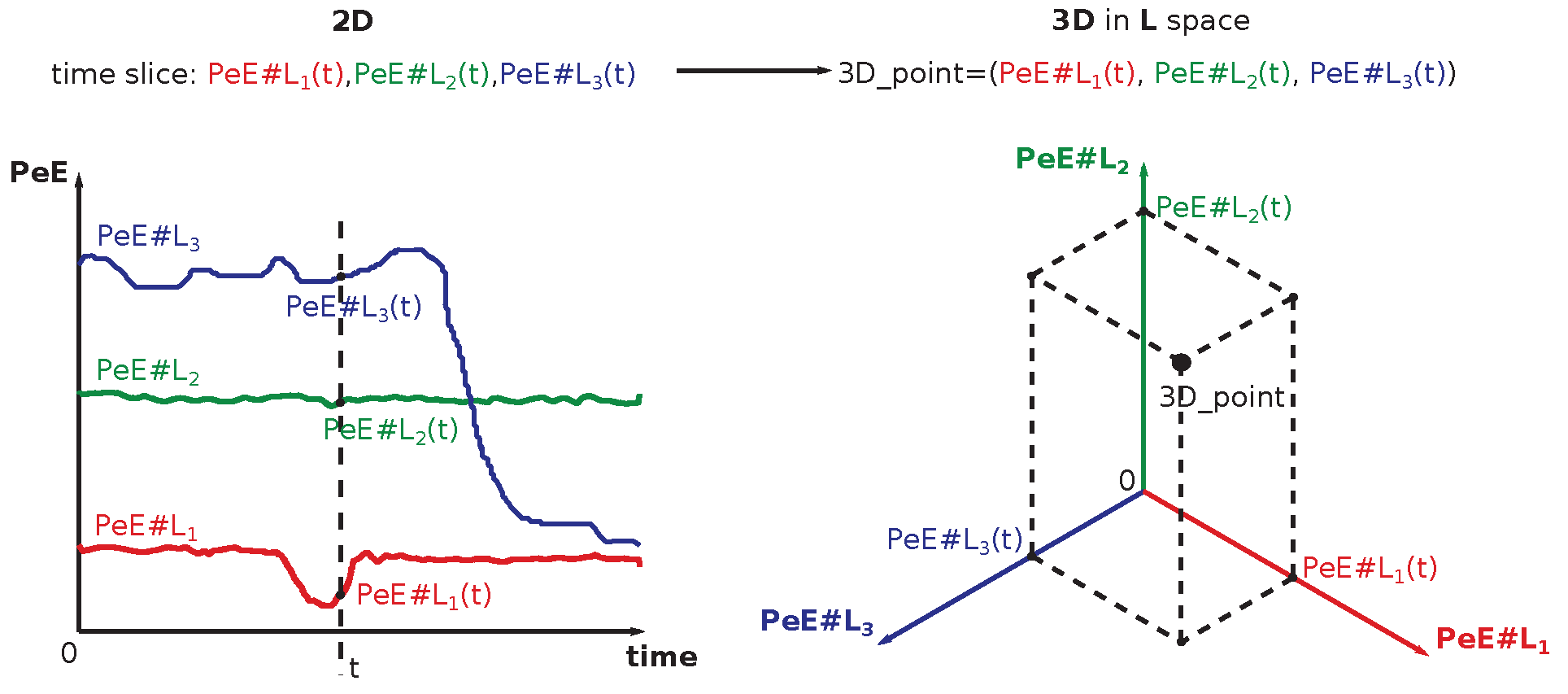

Figure 11 depicts the evaluation of a single value of permutation entropy using three points. Each of those evaluated values is added to the relevant bin of the PeE distribution, where the number of bins is equal to the total value of permutations (in this case, it is equal to six,

). Finally, PeE is evaluated using this distribution.

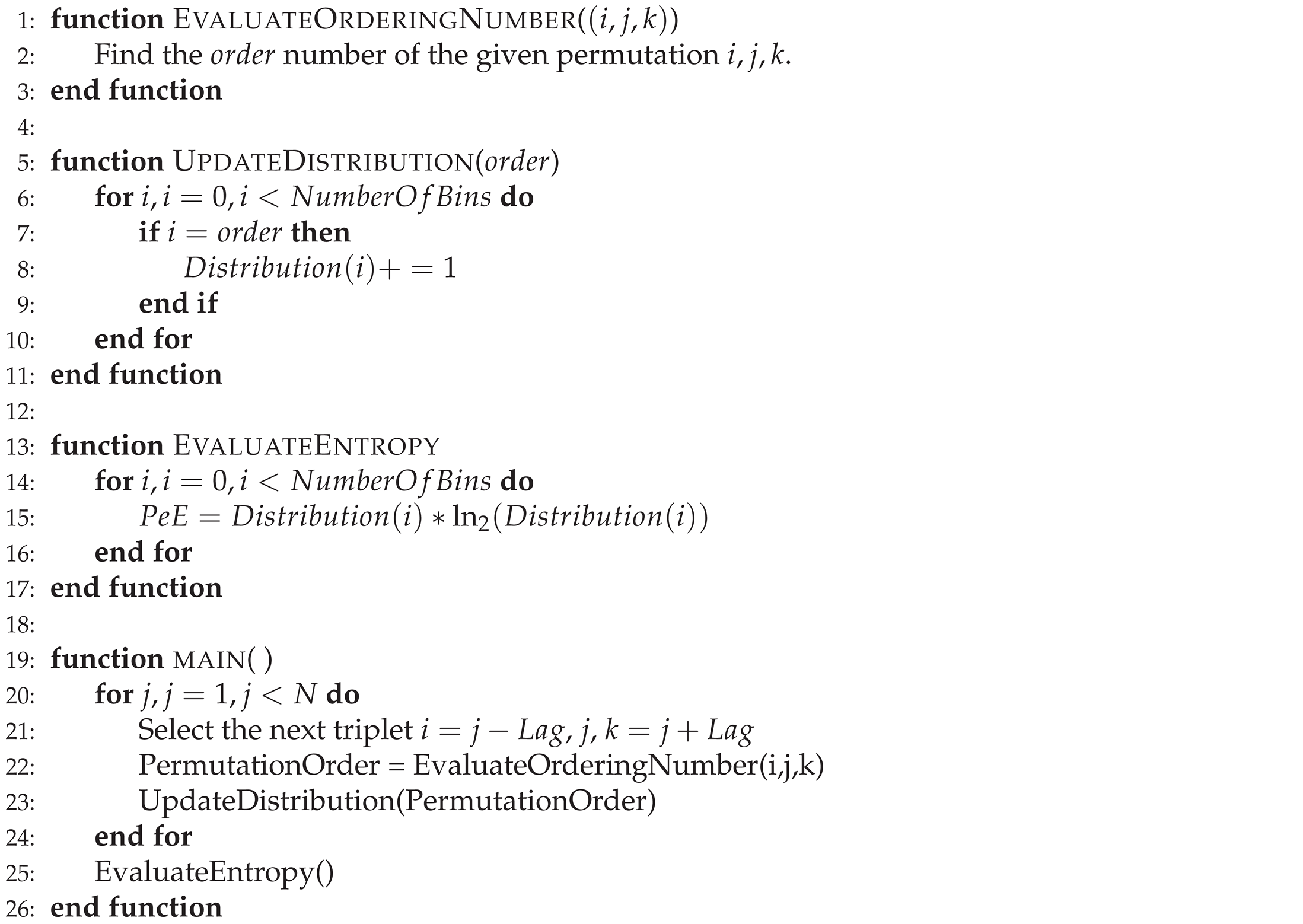

The principle of PeE evaluation is described at Algorithm 1 in the form of a pseudo-algorithm whereas the code itself is found at [

92]. The Python code contains a main function, evaluation of the single value of PeE, evaluation of the ordering number, and update of the distribution.

|

Algorithm 1 The algorithm that is evaluating permutation entropy, which uses three points with the distance equal to , is described using a pseudo-code [92]. N is the length of the input string; triplets of points; the variable defines the distance of values between points of triplets; the variable represents the number of bins within the distribution. |

|

4.3. Permutation Entropy () of Rabbits’ ECG Recordings

Permutation entropy,

[

56], is normally applied to R-R intervals (the distance in [ms] measured between two R peaks of the subsequent QRS complexes) to reveal hidden dependence of R-R variation and a given disease (cardiomyopathy, arrhythmia, or sleep apnea [

18,

55], etc.). Traditionally, R-R intervals are processed in order to remove PVC beats, which are replaced by some local, averaged value of R-R. In HRV studies, ECG recordings might be preprocessed by filtering and other signal preprocessing tools to achieve ’clean’ curves. The novelty of the presented approach lays in the fact that we do not use any kind of preprocessing at all and do study the full ECG recordings. ECG recordings are used in their native form without a change of even a single bit (e.g., it can be checked by use of a visualization software [

93]). The idea behind it is quite simple: in this way, we are not losing any valuable, hidden information about underlying physiology—hence, we keep all hidden information from the underlying complex system within the evaluation process.

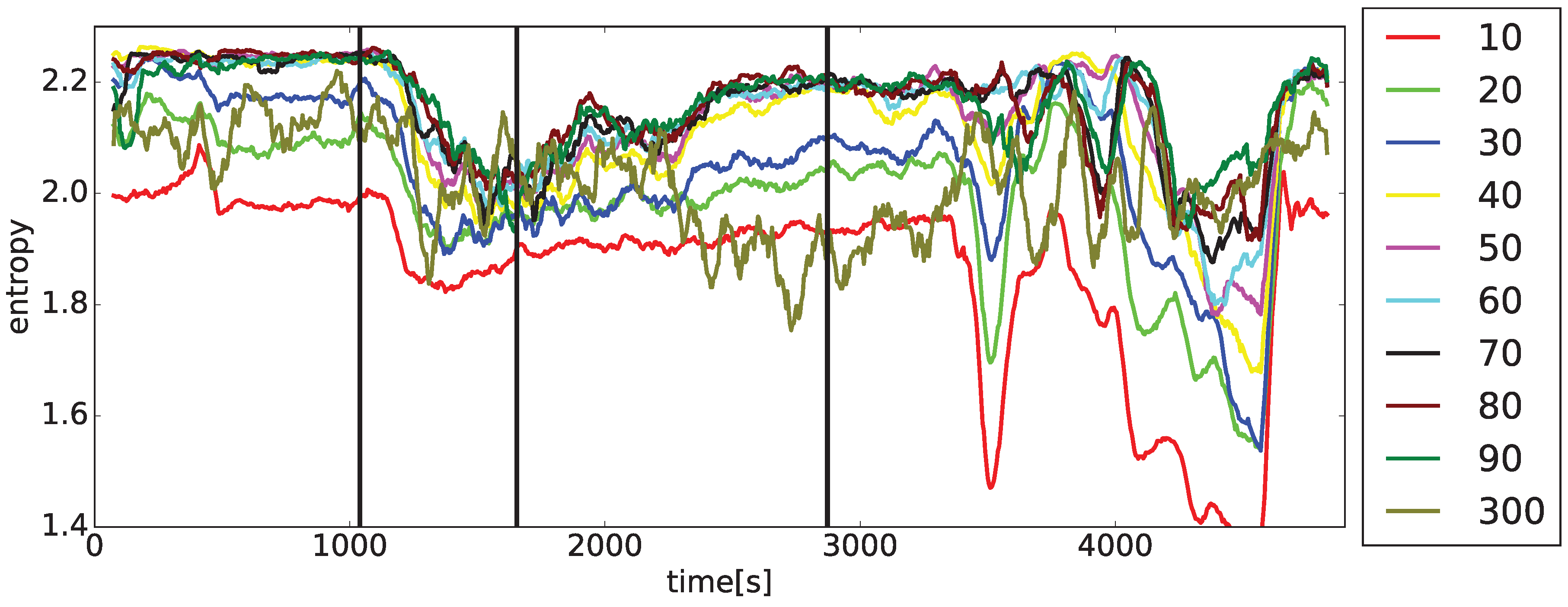

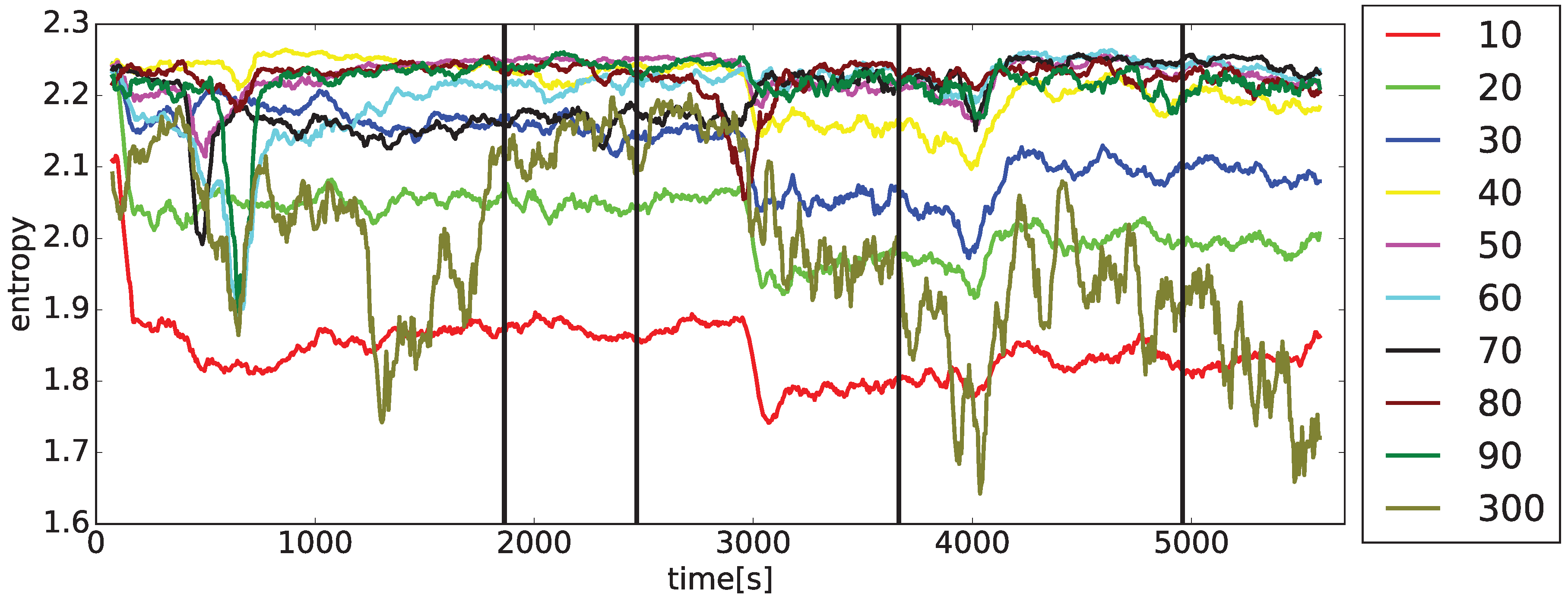

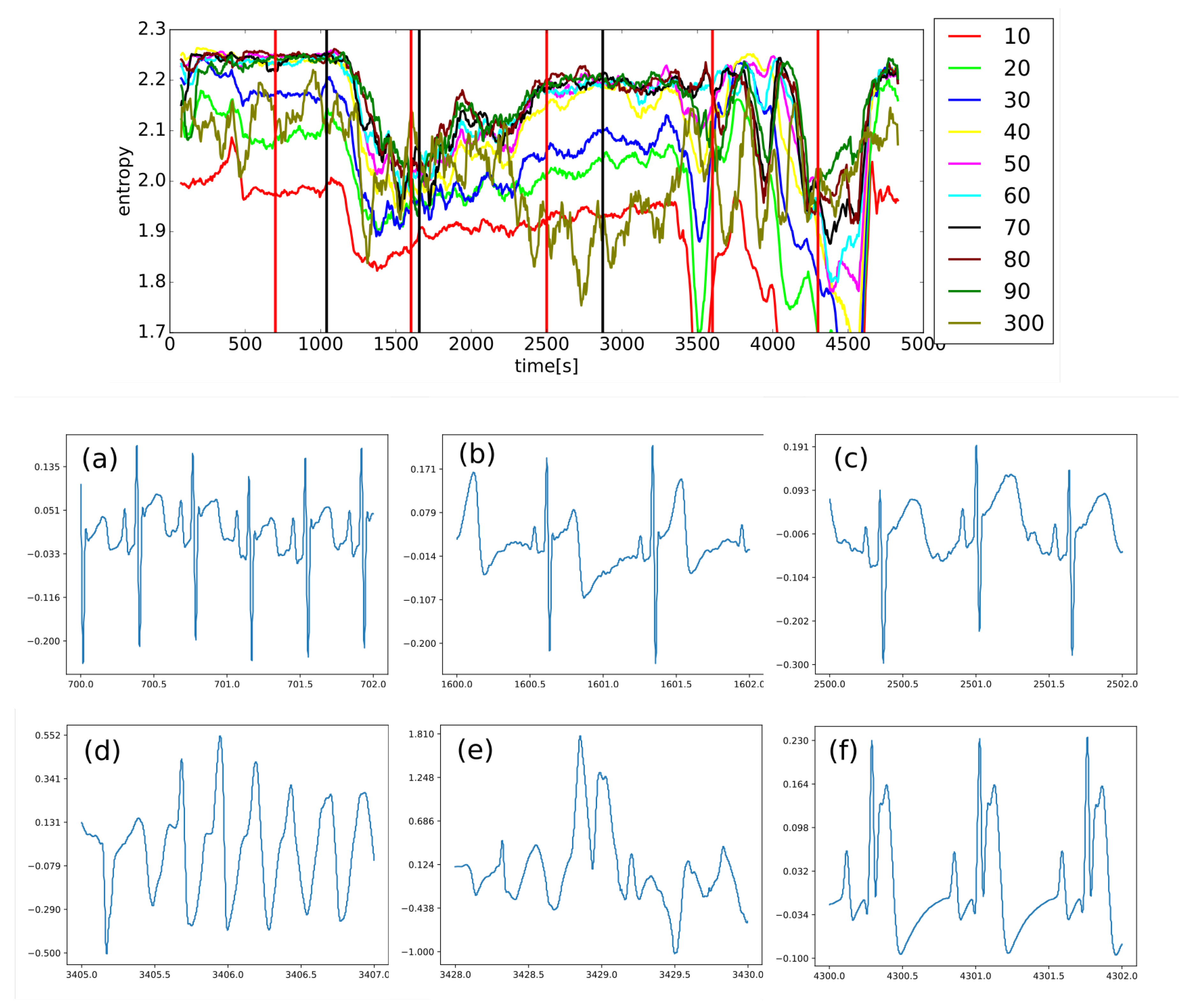

Two sets of

curves with varying

L-s (10, 20, 30, ..., 90, 300) are shown for typical arrhythmogenic (

Figure 12) and non-arrhythmogenic (

Figure 13) rabbits, respectively. The full set of

L-s (representing the distance between measuring points of triplets in [ms], details in

Section 6.2) encompasses: 10, 20, 30, ..., 90, 100, 200, 300, and 500 [ms]. In some cases, the abbreviation

is used, where #L stands for the measure

L. There is present an apparent dependence of

curves on the drug application times for the typical arrhythmogenic rabbit, and a lack of this dependence for the typical non-arrhythmogenic rabbit. The problem is that this behavior can be swapped, in a minor number of cases, for unknown reasons, i.e., an arrhythmogenic rabbit can express the response that is visually close to a non-arrhythmogenic one and

vice versa. We are unable to distinguish those two cases visually and using statistics, as it is necessary to simultaneously compare fourteen projections of each single ECG recording into different

with varying

L-s. Additionally, there are 37 different ECG recordings.

Observations achieved during the initial stages of entropy evaluation that are briefly summarized in

Figure 12,

Figure 13 and

Figure 14, along with a number of standard statistical evaluations, led to the hypothesis that there are existing hidden relationships between

curves and the presence/non-presence of arrhythmia. It was found that simple statistical measures such as mean, variance, standard deviation (STD), min/max differences, and slopes of curves cannot discriminate arrhythmogenic rabbits from those non-arrhythmogenic—this is the moment where a lot of research using standard statistical approaches ends [

95,

96,

97].

The next natural step is to apply modern machine learning methods (ML) [

8,

9,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

63] that are becoming routinely used in such situations. Whenever there exists a hidden relationship among data that is impossible to reveal by standard approaches (equations, statistical methods, etc.), ML methods are often capable of finding such missing relationships.

4.4. Preprocessing of ECG Recordings: Detailed Inspection of ECG Recordings, and Defining Exact Moments of Drug Applications and Their Increasing Doses

The moments of application of medical drugs (anesthesia, methoxamine, and dofetilide), along with their increasing dosages for every single tested rabbit, were carefully put into a table. This was later utilized in defining the appropriate segments of ECG recordings that were used in the ML experiments. This table made by (J.K.), along with all ECG recordings [

52], is not part of this study. The original drug application times are stored in [

52].

4.5. Statistical Features of Subintervals: Demonstrated on Selected Example of 20

The first natural step in finding hidden dependencies and relationships among experimental data is the application of all standard and advanced statistical methods to uncover them [

90]. Unfortunately, according to previous non-systematic testing (J.K.), it appeared that

data resisted revealing any reasonable dependence between the presence/non-presence of an arrhythmia in rabbits and the shape of

curves using statistics; it was anticipated due to the works of other researchers that failed for the same reason (using HRV studies [

52]). The best achieved sensitivity and specificity of decisions of the presence of arrhythmia using statistics from

curves was about 75% in the best cases, which is not sufficient for any effective clinical predictions.

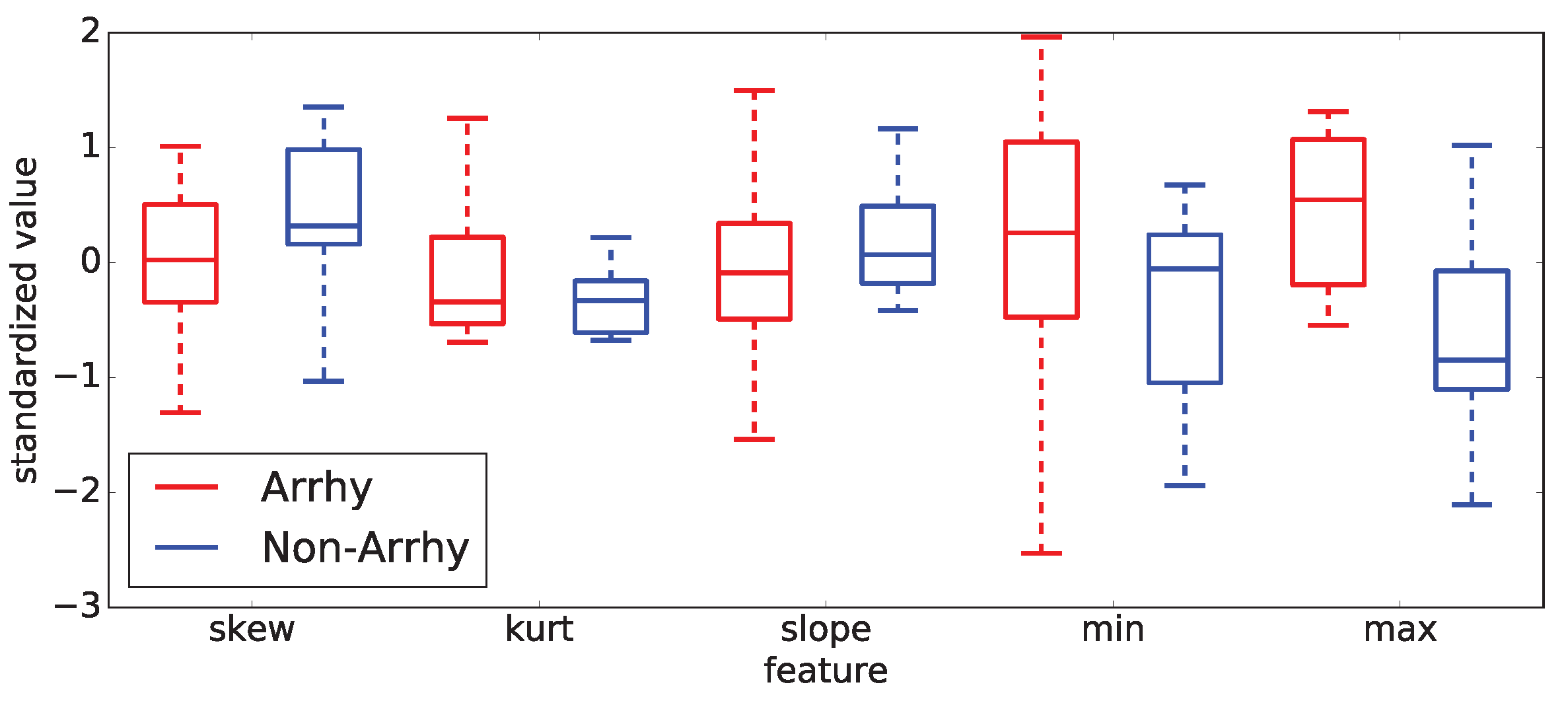

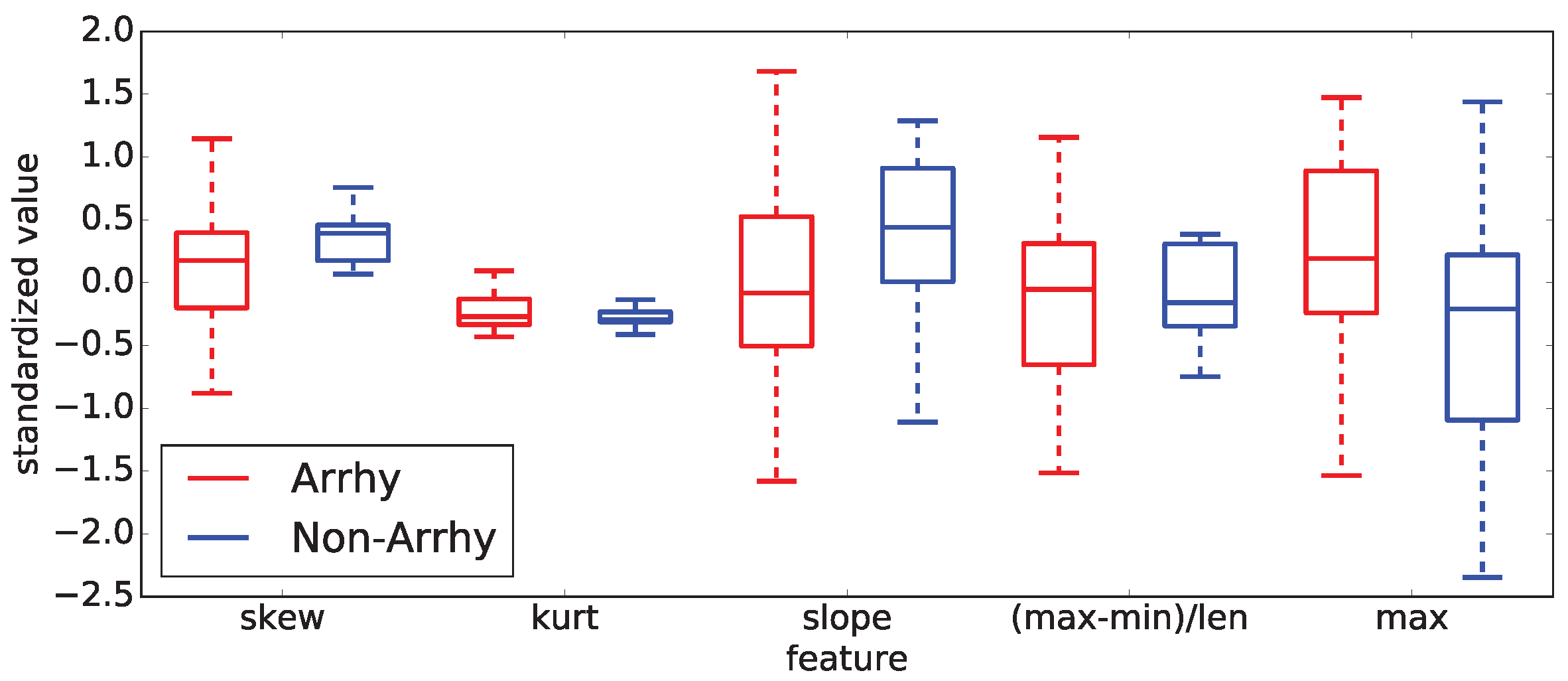

Examples of those observations are documented on two selected sub-intervals of

20 (control and methoxamine), which are giving the best results from all computed results. To demonstrate those facts, two box plots are shown in

Figure 15 and

Figure 16.

Figure 15 shows the five most important statistical features for the control sub-interval of the

20 curve of all rabbits (arrhythmogenic rabbits are in blue and non-arrhythmogenic rabbits are in red).

Figure 16 displays the identical situation but this time for the first methoxamine sub-interval. Evidently, the discrimination between arrhythmogenic and non-arrhythmogenic rabbits is impossible using statistical features. As already said, it was the moment where most, if not all, studies end. The question was, “Is possible to go further and find hidden dependencies among data?” This possibility is demonstrated in the rest of this section.

After a thorough inspection of the presented data in

Figure 15 and

Figure 16 and all other cases of PeE#L (with #L going from 10 up to 500), it became evident that yet another modern, more sophisticated computational approach must be used to reveal information that is scattered among many PeE#L curves and their features simultaneously. This approach is called machine learning (ML)—an important part of the AI research area—which is gaining increasing popularity among researchers processing physiological and other medical data. ML often succeeds in finding dependencies among measured and preprocessed data in situations where all statistical methods fail.

Machine learning is represented by many algorithms and computational methods—regression (the oldest one), decision trees, random forest, support vector machine, clustering, ensembles, neural networks, etc. [

9,

35,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

63]—that are used to reveal hidden data dependencies, which are not being possible to describe by equations, curves, or statistical methods.

4.6. Systematic Definitions of All Features Used During Preprocessing and Evaluation of Curves: This Section Serves as Reference to all Experiments Conducted in This Study and To Easy Orientation

4.6.1. Definition of Data, Features, and Used Operators Abbreviations: Systematic Overview

A large number of features were tested during the search for the best ML methods that can predict the occurrence of arrhythmia; see

Table 5. To allow everybody to follow all tested cases easily, a clear and concise abbreviation of all feature combinations was developed; those abbreviations were used consistently within all evaluations presented in the following subsections and tables. The abbreviations are covered in this subsection.

Each feature abbreviation has the following structure; it consists of the following three parts: <data part><symbol><feature part>. The features that are specified in the feature part are evaluated using data specified in the data part. The <data part> contains the following abbreviations: OC = original curve, SI = sub-intervals, M = merged (M is used before SI), I = isolated (I is used before SI), and the attribute RM = rolling mean.

The <symbols> used in the description of each feature abbreviation (definitions above and below): "_": separates data and feature parts (e.g., ISI_Top5-TM); "-": represents the logical relation inside both data and feature parts of the abbreviation (e.g., ISI-DFT_Top5-C); "&": merges together features computed on the left and right sides of this operator (e.g., ISI_Top5-TM & ISI_ASF). The priority of evaluation of symbols is the following: ’-’ > ’_’ > ’&’. It starts with the symbol of the highest priority, ’-’, and ends with the symbol ’&’ of the lowest priority.

The <feature part> can contain the following symbols: -L = values of the L parameter, _Top5 = top five, *SI-DFT = s reconstructed by discrete Fourier transformation (DFT) approach, *SI-DWT = s reconstructed by discrete wavelet transformation (DWT) approach, *SI-D*T_Top5-C = top five coefficients (D*T = DFT or DWT), -TM = time moments, -SSF = simple statistical features, and -ASF = all statistical features (simple + advanced).

An example of the use of the abbreviations follows: MSI_Top5-TM = Merged Sub-Intervals_Top 5-Time Moments; see

Table 5. The operator "-" is

left-associative, it is meaning that the operations are grouped from the left. An example is

that gets interpreted as

.

4.6.2. Assessing Curves and Designing Data Structures for ML-Experiments

Each rabbit was subjected to a number of drug infusions, which were applied at different times and had different durations. Such data cannot be compared directly. It is necessary to reflect those variations in the data evaluation and comparison by making an appropriate data preprocessing. Data had to be properly shifted and sliced to enable their comparison. Shifts were done according to the times when the respective drug infusion was applied (methoxamine and dofetilide I-III, -). Drugs had been applied continuously after each infusion initiation: they were not mere boluses. Therefore, the following data exploration steps were performed:

- (i)

The minimum number of drug infusions that was common for all rabbits was selected in order to compare rabbits correctly. It yielded two intervals: the interval ’0’, called the comparison/control interval (before ), and the interval ’1’, called the methoxamine one (after ). No other intervals can be used because some rabbits got arrhythmia and expired during the second interval (after the application of the first infusion of dofetilide, ; the interval called ’2’). Yet some other rabbits died at the interval ’3’, after an increase of the dose of dofetilide, . Whereas, all non-arrhythmogenic rabbits survived all harsh drug insults applied.

- (ii)

For each rabbit, a selected control interval had the length of 505 seconds (the minimal common value) just before the application of the first infusion (methoxamine). The actual moment of methoxamine application, , vary for all rabbits.

- (iii)

Time intervals between the moment of initiation of methoxamine infusion , , and the first dofetilide infusion, , are different for each rabbit, and they yield . Firstly, the length of this interval is retrieved for each rabbit separately. Secondly, the minimal common length of this interval for all rabbits was assessed, which produced the value of 465 seconds. It is assumed that the moment of methoxamine application, , belongs to the interval of methoxamine and not to the control interval—the drug disruption of physiology starts there, whereas anesthesia disruption is already present in the control interval.

4.6.3. Preprocessing of Curves: Design and Creation of Subintervals That Were Subsequently Tested by Whole Range of ML Methods

According to the previous section dealing with the data exploration, two intervals were dissected from each curve control and methoxamine that are abbreviated and called control (’0’) and methoxamine (’1’), respectively. In the following, the term ’value’ is used, which represents an interval having length of 5 seconds. curves were exported by averaging over this interval because the actual signal oscillates too much when displayed at each point of the original ECG recording within each [ms]). The lengths of the original curves have between 550 and 1416 values (2750 and 7080 seconds). According to the previous, 101 values (505 seconds) were taken for the control interval and 93 values (465 seconds) were assumed for the methoxamine interval. The maximal lengths of control and methoxamine intervals are defined by their respective maximal common lengths in all curves. Remember, from now on we work only with evaluated s and not original ECG recordings.

It is necessary to take into account the rounding process that might have an influence to results, but which size is difficult to assess. Obviously, drug infusions started in arbitrary moments. Due to this fact, the initiation times of drug infusions were rounded to the nearest lower value, which is a multiplication of five seconds (141 to 140, 14 to 10, 88 to 85 etc.).

4.7. List of All Tested Combinations of Features Used to Find the Best Statistics and ML Methods: This Serves as Thorough Navigation Tool to Design Similar Future Approaches

This subsection briefly describes why features are so important and also provides an overview of all used features along with their mutual combinations in this study (details in [

90]). Generally, each evaluation of data using ML methods goes from simple features to the more advanced ones. Combinations of features are used in the case when everything else fails. The necessity to use features extracted from the original data in ML methods is manifold: (i) original data are too huge, (ii) original data are not suitable to apply ML methods on, and (iii) there is a need to describe data by some special features not present in the original data (slope, maximum, mean, SD, entropy, information content, etc.).

4.7.1. Simple Statistical Features

Simple statistical features used in this study are represented by mean, standard deviation, variance, min, max, 25th, 50th, and 75th percentiles. Those are standardly used statistical features.

4.7.2. Advanced Statistical Features

Advanced statistical features used in this study are represented by: integral, skewness, kurtosis, slope, , energy of time series, sum of values of time series, and trend of time series (uptrending, downtrending, or without trend).

4.7.3. All Tested Features and Their Combinations

Control and methoxamine sub-intervals were cut from all

curves for all rabbits using a special procedure; see the preprocessing above (

Section 4.4 and

Section 4.6.3). Those sub-intervals were and the original PeE curves were used to compute all features—see

Table 5 for a list of all used features and their combinations—which were applied in the search for the best methods for predicting arrhythmia. To enable an easy orientation among all features, a visual guidance is provided. The importance of each set of features (which are acquired during subsequent evaluation) is reflected by the number of stars (more star symbols equals more important results). Results are grouped into the following groups: ’***’ as best (ARARS ≥ 90%), ’**’ as sufficient (80% ≤ ARARS < 90%), ’*’ as average (75% ≤ ARARS < 80%), and ’ ’ as not useful (no star) (ARARS < 75%); see the Equation (

9) for the definition of ARARS score.

4.8. List of All Performed Machine Learning Experiments: The Core Part of the Conducted Research Together with Permutation Entropy Evaluation

This is one of two essential parts of the whole research conducted and covered in this paper (see details of ML experiments in [

90]), which is intentionally made very detailed and deep for methodical reasons. The entire search algorithm is shown in

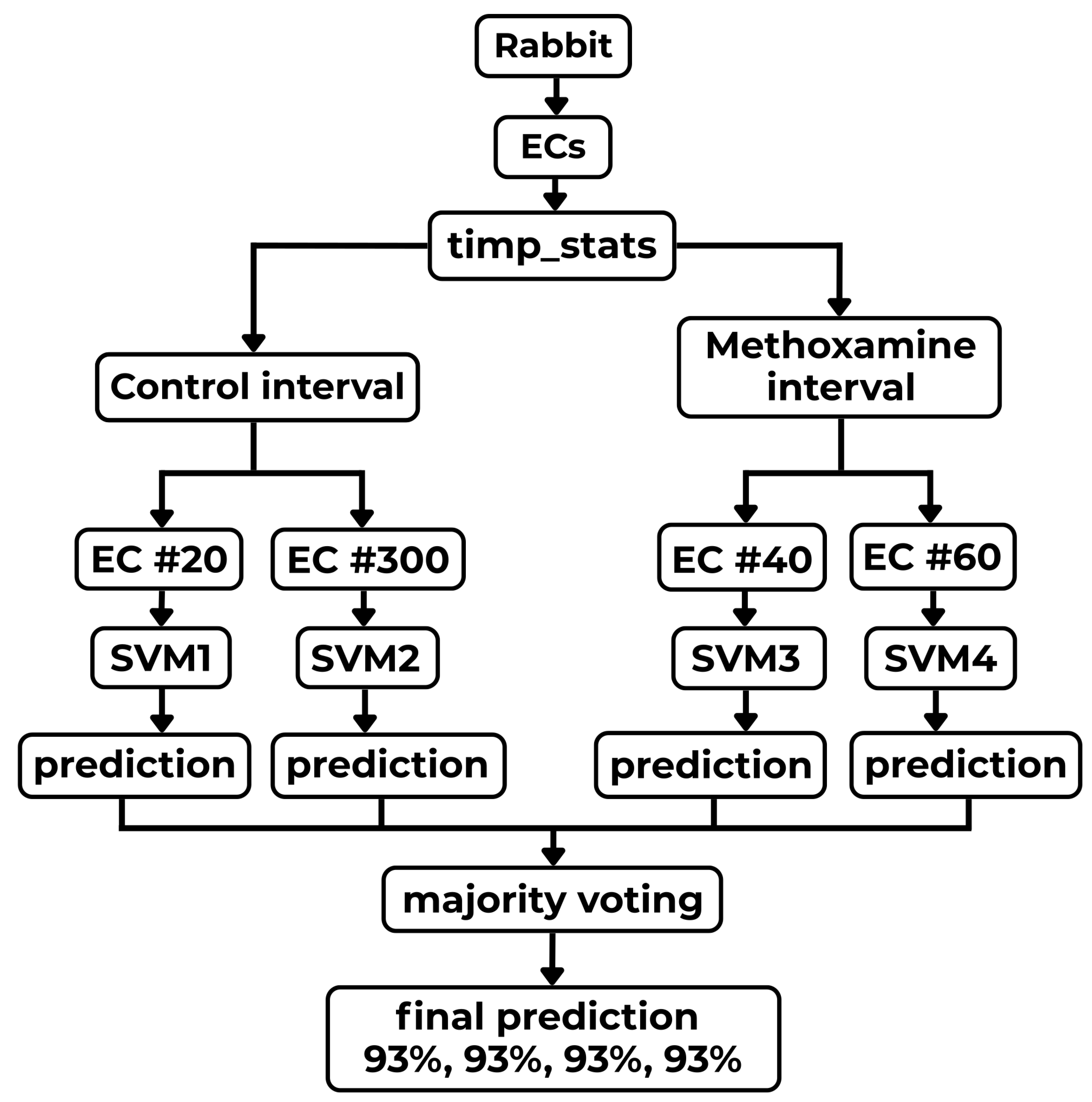

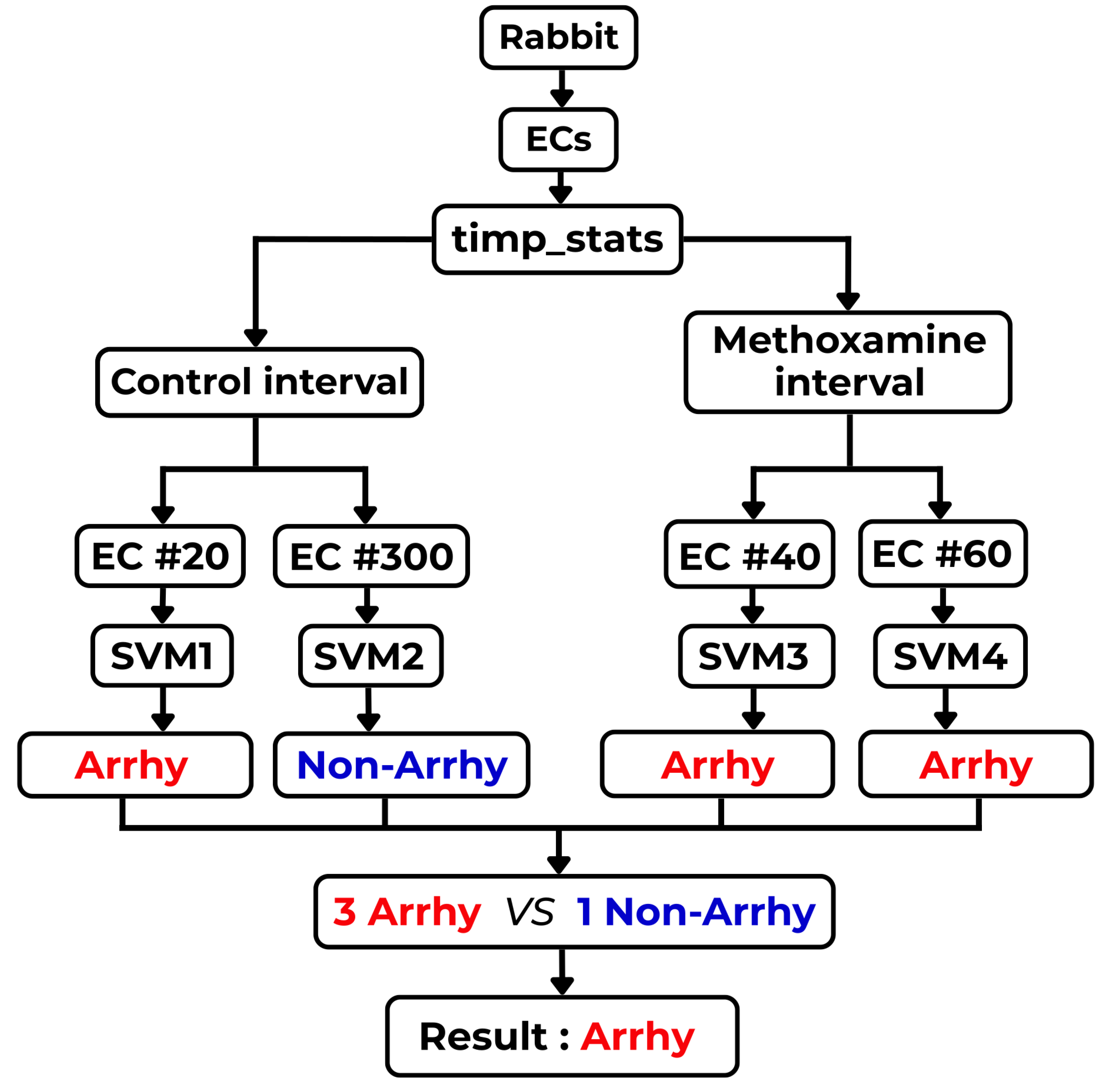

Appendix A.1 in the form of a map depicted in

Figure A1. The main reason behind all of this is to provide enough procedural knowledge to all who would like to apply similar research in their respective field of signal processing—not only in biology, but also in any scientific field working with signals (physics, sociology, economy, etc.). This thoroughness helps non-specialists to realize the full capabilities of ML methods in not only biosignal processing.

- (A)

-

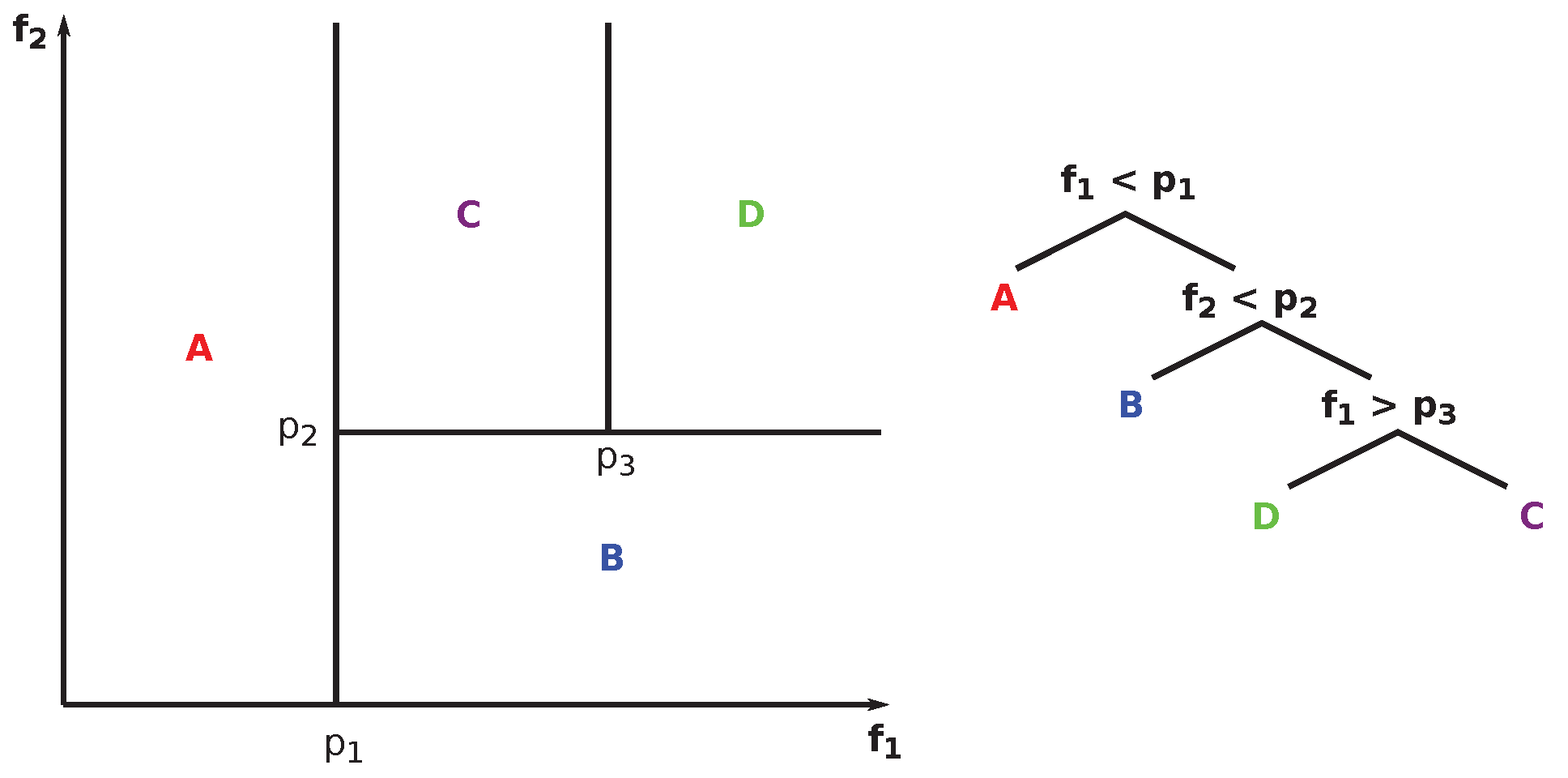

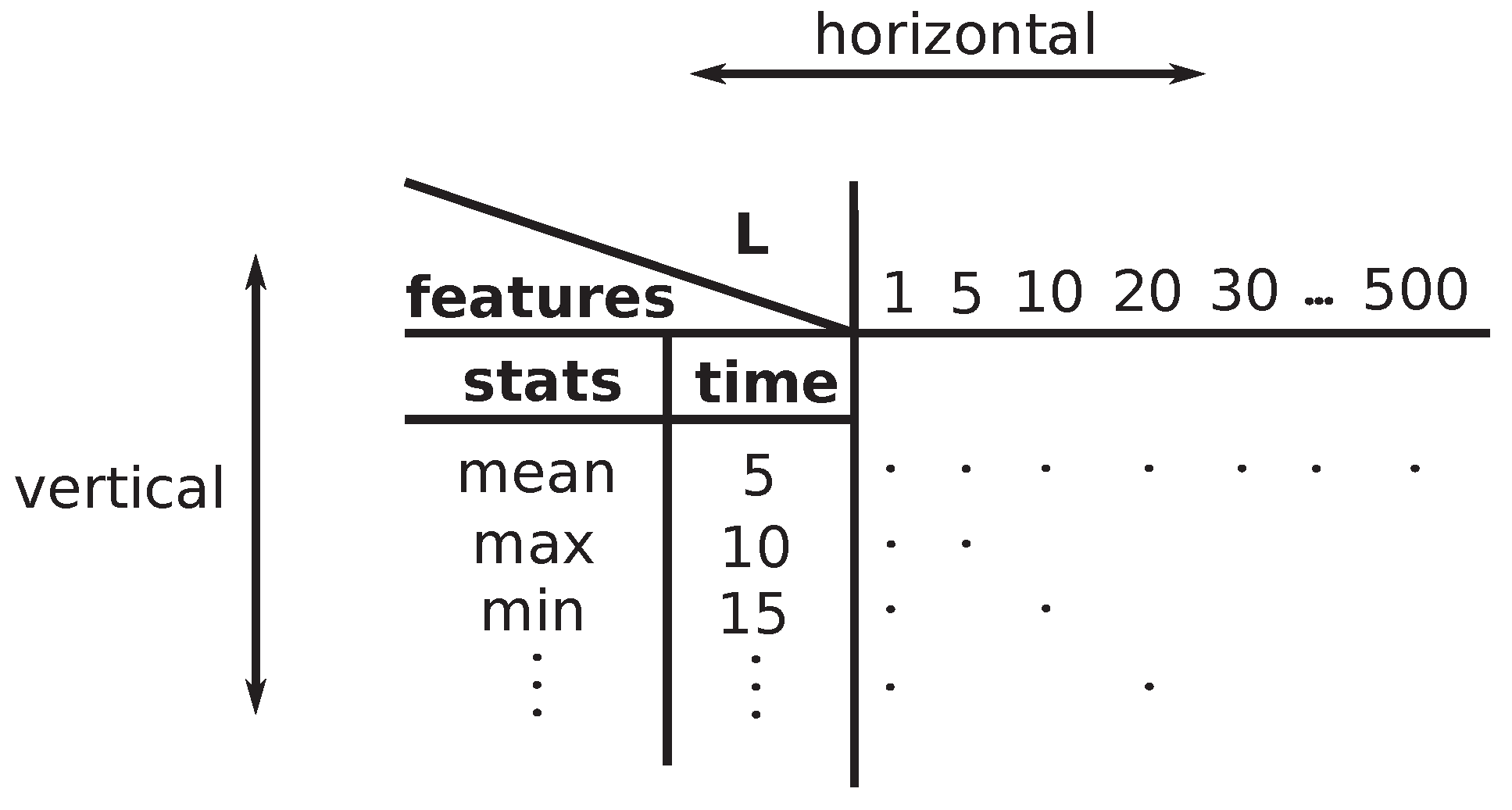

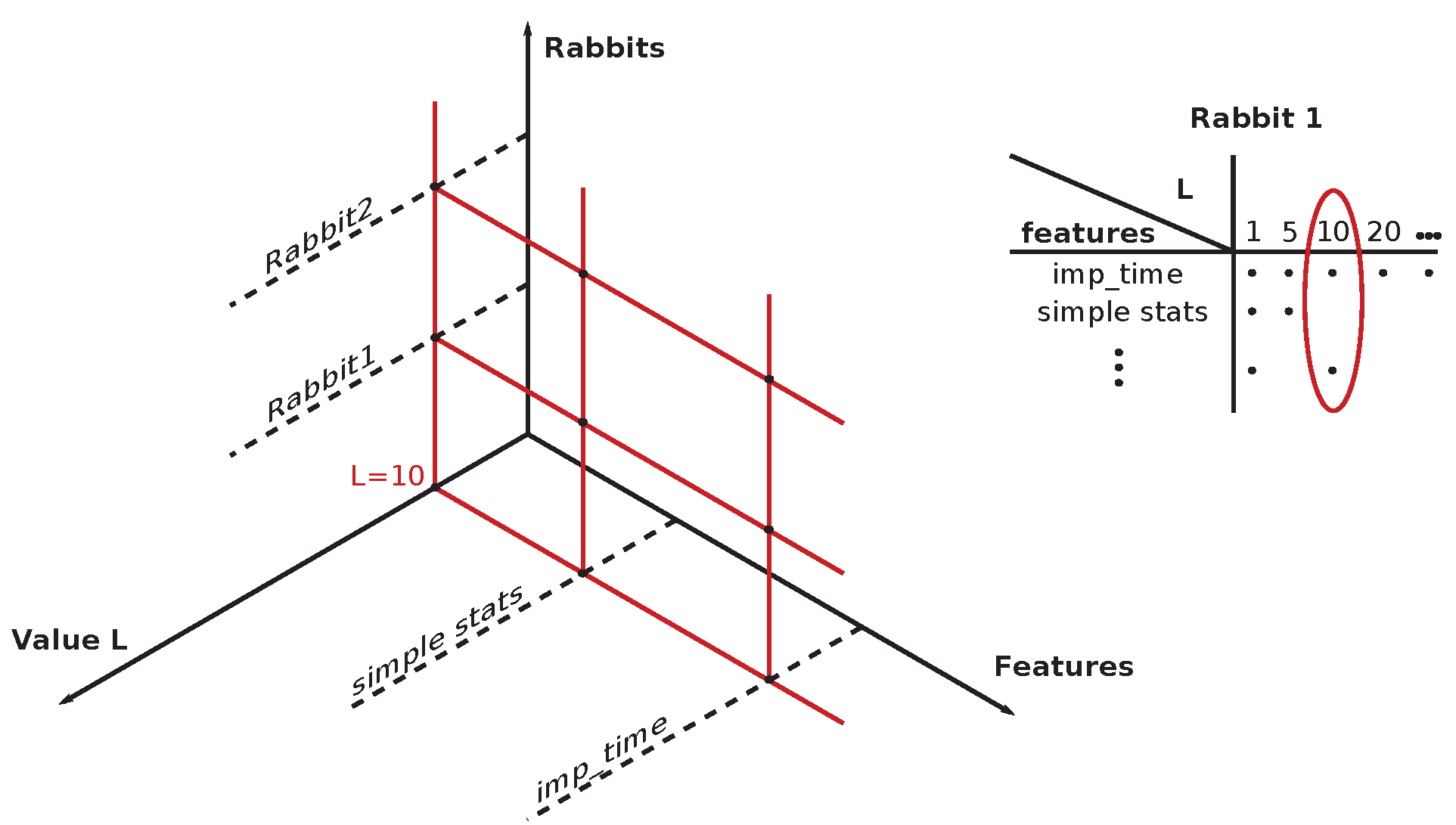

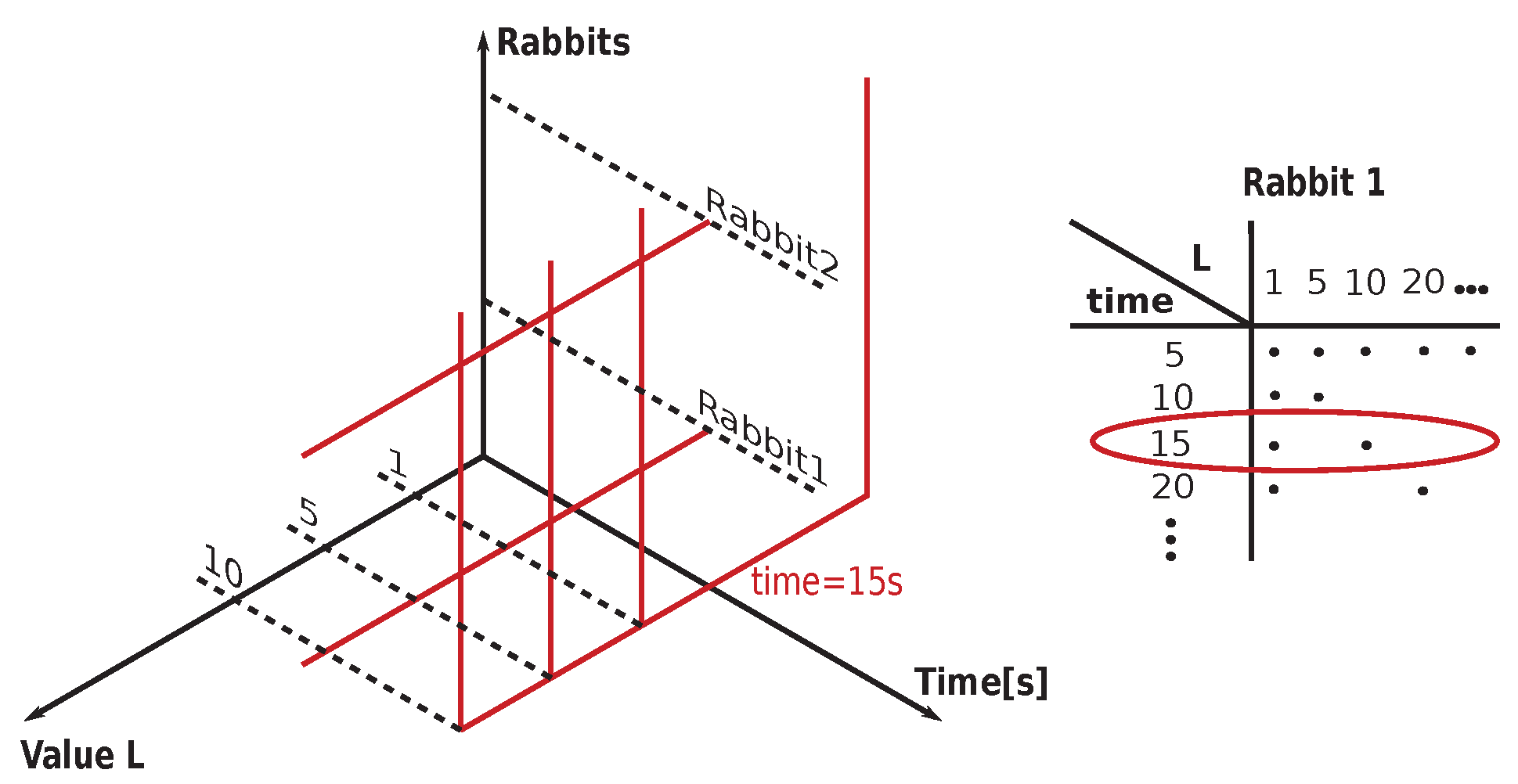

Important time moments: each of s sub-intervals was too long for ML methods (approximately 100 values), and thus various subsampling strategies were tested: only Random Forest succeeded. The pitfall in this approach is that the classification outputs were—in this way—introduced to the experiment already during the subsampling process by Random Forest. After this preselection, the identified important time moments (subsamples of the sub-intervals) were used—served as the input—for subsequently used ML methods. It is not sure whether this approach can be considered an allowable one when we deal with such an extremely low number of ECG recordings.