Submitted:

26 August 2025

Posted:

27 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

| Biological Mycelium | Mycelial_Net Architecture | Functional Analogy |

|---|---|---|

| Network of hyphae forming an interconnected, decentralized structure | Graph-like network of nodes with dynamically reconfigurable connections | Distributed processing without a central controller |

| Environmental sensing via chemical, physical, and electrical signals | Input feature “sensing” via convolutional filters and structural feature extractors | Pattern detection and feature recognition from raw data |

| Nutrient discrimination between usable resources and harmful substances | Adaptive weighting between relevant and irrelevant features | Selective amplification of informative signals |

| Resource allocation to growth zones or symbiotic interfaces | Dynamic connectivity adjustment to strengthen high-utility paths | Prioritization of pathways that improve classification |

| Memory through structural changes in hyphal pathways | Plasticity in network topology and hyper-parameters during training | Long-term retention of learned decision patterns |

| Resilience to local damage due to redundancy in the network | Fault tolerance to image imperfections and noisy inputs | Robust performance under imperfect or incomplete data |

| Collaborative symbiosis with plants via mycorrhizal interfaces | Integration with other models (e.g., ResNet, CNN, SVM hybrids) |

Cooperative knowledge sharing across architectures |

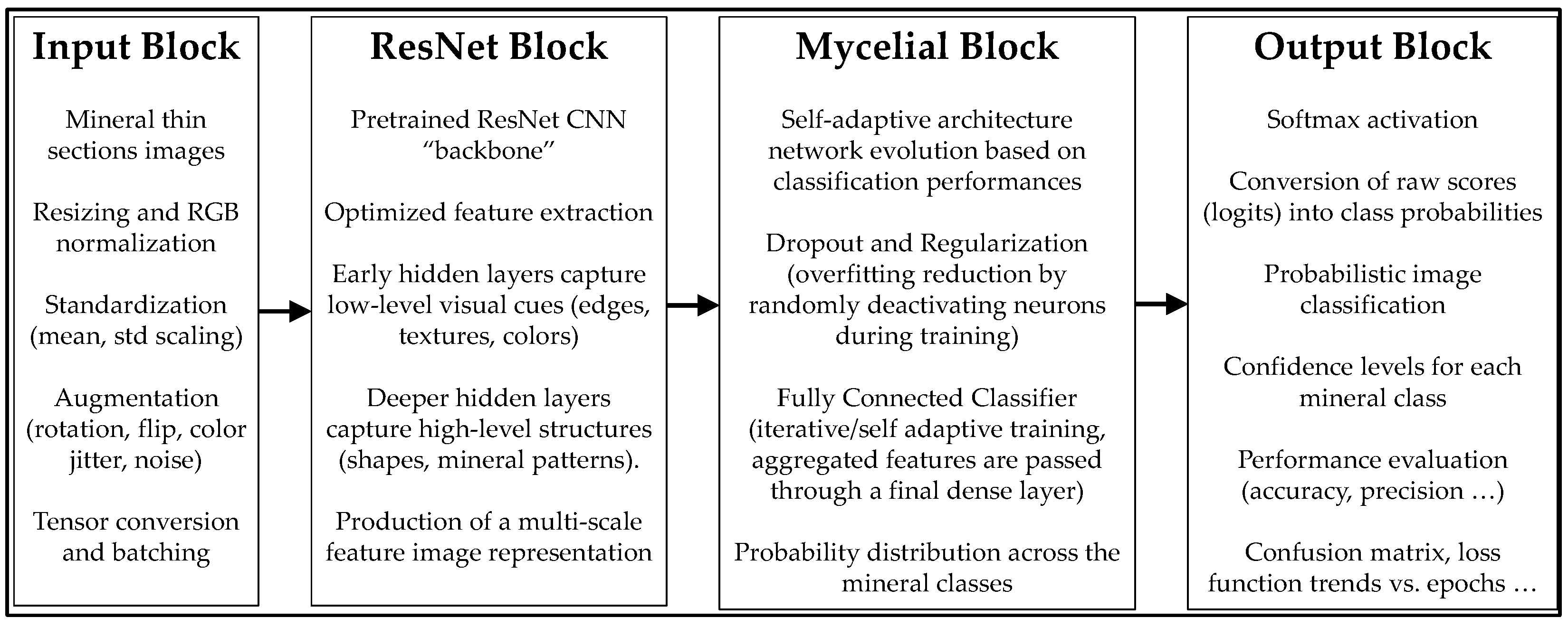

2. Methodology

2.1. Basic Principles

2.2. Formalization of Myclelial_Net Model

- Wt is the weight matrix at time t,

- Wt-1 is the weight matrix at the previous time step t-1,

- Mt∈ {0,1} n×d is a binary mask matrix controlling active connections at time t,

- n is the number of features,

- d is the number of neurons in the layer.

- ⊙ represents the Hadamard (elementwise) product,

- η is the learning rate,

- is the gradient of the loss function L at time t.

- m is the number of samples (e.g., thin section mineral samples), as state earlier,

- k is the number of output classes (e.g., types of minerals), as state earlier,

- is the true label (one-hot encoded, where for the true class and otherwise),

- is the predicted probability for the j-th class for the i-th sample, computed using the Softmax function.

- is the activation from the previous neuronal layer,

- is the dynamically adjusted weight matrix,

- is the bias vector,

- is an activation function (e.g., Rectified Linear Unit, briefly ReLU, or sigmoid, as well as other activation functions settable by the user).

2.3. Empowering Myclelial_Net Model with Residual Network

- -

- Early convolutional layers capture low-level visual features such as edges, textures, and simple color transitions.

- -

- Intermediate layers progressively detect more complex structures, such as mineral grain boundaries, morphological patterns, and characteristic textures.

- -

- Deeper layers encode high-level, abstract representations, including shapes, compositional structures, and object-level features that are essential for distinguishing among different minerals.

- -

- The residual design stabilizes the optimization process and increases efficiency, ensuring that very deep models remain trainable and resistant to degradation.

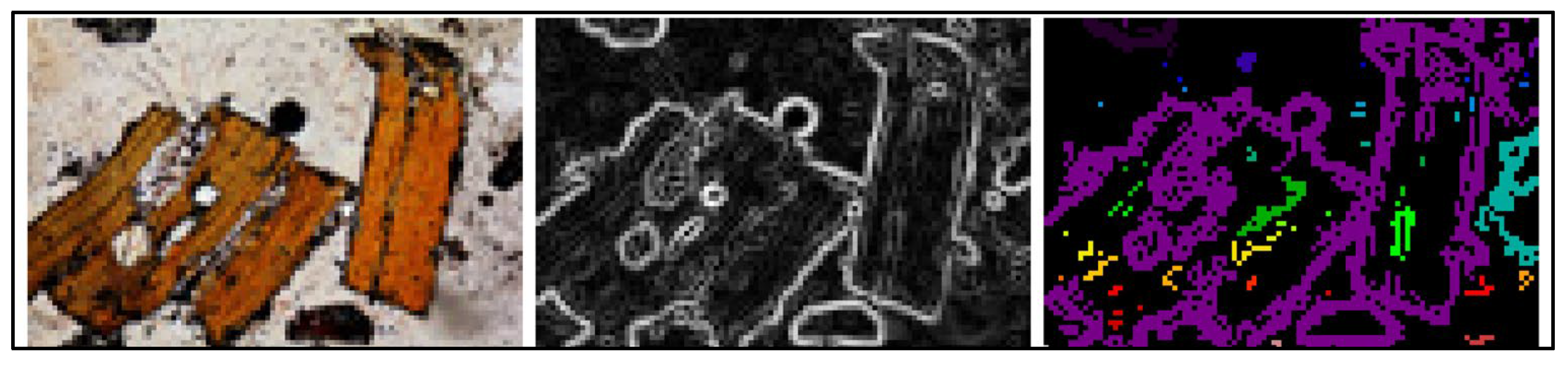

3. Image Analysis, Edge Detection and Segmentation

4. Test: Adaptive Training and Classification with Mycelial_Net

4.1. The Model

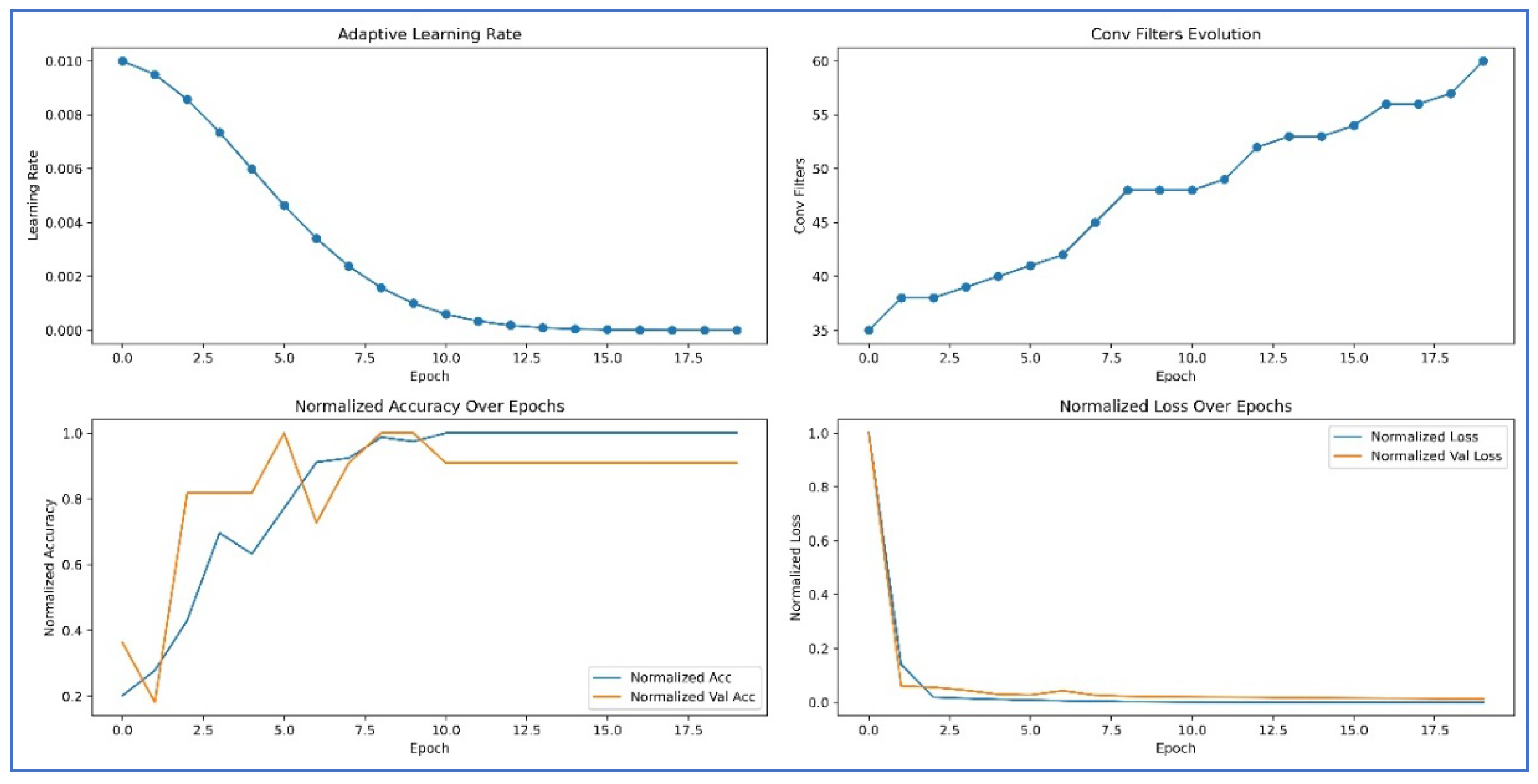

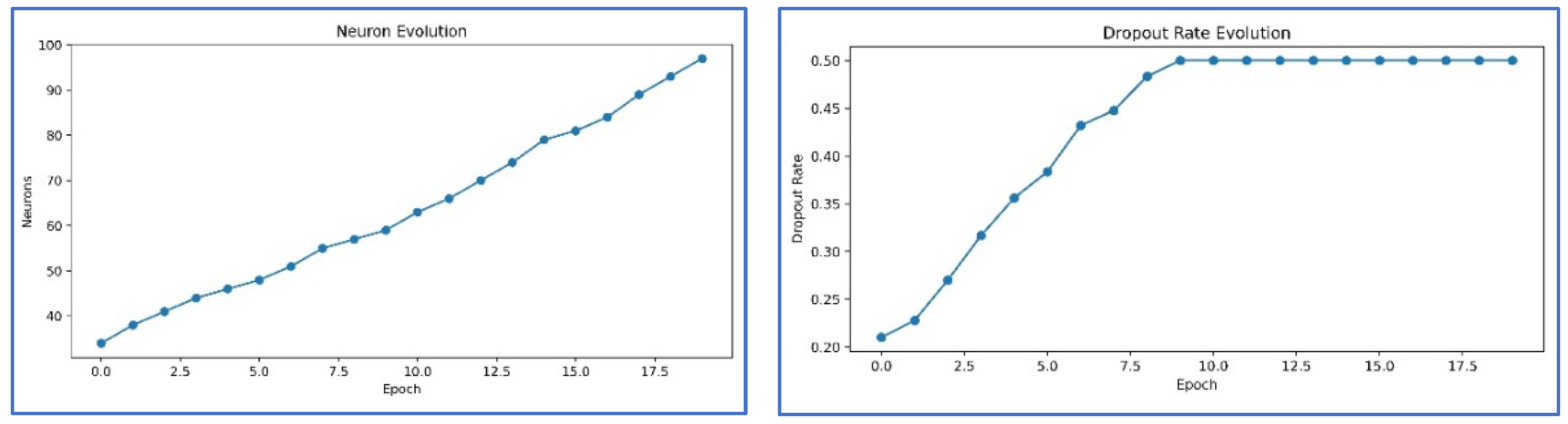

4.2. Adaptive Hyperparameter Strategy

4.3. Training Procedure

4.4. Evaluation

4.5. Results and Visualization

- -

- Biologically inspired architecture – The Mycelial_Net model integrates multiple hidden layers connected through mycelium-like blocks, which combine linear and non-linear transformations in a way that enhances information flow and feature abstraction.

- -

- Resilience to noise and degradation – As explained earlier, our Mycelial_Net model is empowered by deep feature extraction from the ResNet backbone with adaptive hidden layers. The model captures subtle textural and structural patterns of minerals that remain invariant under poor image quality.

- -

- Progressive self-adaptation – During training, the network dynamically grows by adding new hidden layers and neurons when the learning stagnates. This process allows the model to adaptively refine its internal representations and reach optimal classification performance.

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Izadi, H.; Sadri, J.; Bayati, M. An intelligent system for mineral identification in thin sections based on a cascade approach. Comput. Geosci. 2017, 99, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- She, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhang, X.; Qian, W. Mineral identification based on machine learning for mineral resources exploration. J. Appl. Geophys. 2019, 168, 68–77. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, K.; Liu, J.; Wang, K.; Wang, Y.; Ma, Y. Deep learning-based mineral classification in thin sections using convolutional neural network. Minerals 2020, 10, 1096. [Google Scholar]

- Slipek, B.; Młynarczuk, M. Application of pattern recognition methods to automatic identification of microscopic images of rocks registered under different polarization and lighting conditions. Geol. Geophys. Environ. 2013, 39, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aligholi, S.; Khajavi, R.; Razmara, M. Automated mineral identification algorithm using optical properties of crystals. Comput. Geosci. 2015, 85, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, M.; Han, S.; Ren, Q.; Shi, J. Intelligent Identification for Rock-Mineral Microscopic Images Using Ensemble Machine Learning Algorithms. Sensors 2019, 18, 3914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dell’Aversana, P. An Integrated Deep Learning Framework for Classification of Mineral Thin Sections and Other Geo-Data, a Tutorial. Minerals 2023, 13, 584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dell’Aversana, P. , Deep Learning for automatic classification of mineralogical thin sections. Bull. Geophys. Oceanogr. 2021, 62, 455–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dell’Aversana, P. , Enhancing Deep Learning and Computer Image Analysis in Petrography through Artificial Self-Awareness Mechanisms. Minerals 2024, 14, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dell’Aversana, P. Evolutionary Ensembles of Artificial Agents for Enhanced Mineralogical Analysis. Minerals 2024, 14, 1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dell’Aversana, P. A Biological-Inspired Deep Learning Framework for Big Data Mining and Automatic Classification in Geosciences. Minerals 2025, 15, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldrake, M. Entangled life: how fungi make our worlds, change our minds & shape our futures; First US edition 2020; Random House: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Dell’Aversana, P. Self-Aware Joint Inversion of Multidisciplinary Geophysical Data in Mineral Exploration Using Hyperparameter Self-Adjustment: A Preliminary Study. Minerals 2025, 15, 623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, B. Facies classification using machine learning. Lead. Edge 2016, 35, 906–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- She, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhang, X.; Qian, W. , Mineral identification based on machine learning for mineral resources exploration. J. Appl. Geophys. 2019, 168, 68–77. [Google Scholar]

- Mamani, M.; Wörner, G.; Sempere, T. Geochemical variations in igneous rocks of the Central Andean orocline (13°S to 18°S): Tracing crustal thickening and magma generation through time and space. GSA Bulletin 2010, 122, 162–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binetti, M.S.; Massarelli, C.; Uricchio, V.F. Machine Learning in Geosciences: A Review of Complex Environmental Moni-toring Applications. Mach. Learn. Knowl. Extr. 2024, 6, 1263–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.E.; O’Malley, D.; Beroza, G.; Curtis, A.; Johnson, P. Machine Learning Developments and Applications in Solid-Earth Geosciences: Fad or Future? J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2023, 128, e2022JB026310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sören, J.; Fontoura do Rosário, Y.; Fafoutis, X. Machine Learning in Geoscience Applications of Deep Neural Networks in 4D Seismic Data Analysis. Ph.D. Thesis, Technical University of Denmark, Kongens Lyngby, Denmark, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya, S. Summarized Applications of Machine Learning in Subsurface Geosciences. In A Primer on Machine Learning in Subsurface Geosciences; SpringerBriefs in Petroleum Geoscience & Engineering; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 123–165. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Gu, X.; Tang, L.; Yin, Y.; Liu, D.; Zhang, Y. Application of machine learning, deep learning and optimization algorithms in geoengineering and geoscience: Comprehensive review and future challenge. Gondwana Res. 2022, 109, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Model | Validation accuracy | Average F1-Score |

| Baseline CNN | ≤ 0.78 | ≤ 0.76 |

| Mycelial_Net | ≥ 0.95 | ≥ 0.95 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).