1. Introduction

Phased antenna arrays are essential components in modern communication systems, radar technologies, and satellite networks due to their capability to dynamically steer beams and control radiation patterns [

1]. Among these,

conformal antenna arrays—those mounted on curved surfaces such as satellite bodies or Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) fuselages—are gaining increased attention for their mechanical adaptability and seamless integration into complex platforms [

2,

3]. However, designing efficient conformal arrays is challenging due to the geometric constraints introduced by non-planar surfaces. When arrays are mounted on curved structures like cylindrical or spherical surfaces, traditional design methodologies often fall short of meeting stringent performance requirements [

4,

5].

Conventional synthesis of antenna arrays has relied on manual tuning or semi-automated optimization. Techniques such as

particle swarm optimization (PSO),

genetic algorithms (GA), and

differential evolution (DE) have been widely used to optimize array parameters based on predefined objectives [

6,

7]. While effective in some cases, these methods are computationally intensive, require repeated interactions with electromagnetic solvers, and lack scalability in high-dimensional or non-convex design spaces—challenges that are amplified when dealing with conformal geometries [

8]. Gradient-based algorithms and

simulated annealing (SA) also suffer from similar limitations in such complex design environments [

9,

10].

Recent advances in

machine learning (ML) have opened new possibilities in automating and accelerating the antenna design process. Supervised learning using deep neural networks (DNNs) has been applied to predict optimal parameters from labeled datasets, achieving significant speedups over traditional methods [

11,

12]. However, these models are heavily dependent on large, diverse datasets and struggle to generalize across novel antenna geometries or configurations [

13]. Unsupervised approaches, such as k-means clustering, have been used for design space exploration and pattern recognition, but they do not directly optimize antenna performance [

14].

A more recent and promising direction involves

reinforcement learning (RL), which enables agents to iteratively improve performance through feedback-based interactions with an environment [

15,

16]. In antenna design, RL can optimize beam steering or array configurations by learning from reward signals linked to communication performance metrics as seen in [

17]. However, traditional RL methods require extensive real-time interaction, which is not ideal for antenna synthesis especially in resource-constrained environments due to the high cost and time associated with electromagnetic simulations. To address this limitation,

offline reinforcement learning, particularly the

Deep Q-Network (DQN) algorithm, has emerged as a viable solution. By learning from precomputed datasets, offline RL significantly reduces resource consumption while maintaining robust policy learning [

18].

The key advantages of offline RL in antenna synthesis include its ability to adapt to diverse environments, scale to high-dimensional spaces, and learn optimal strategies without real-time experimentation. When combined with predictive ML models, this approach enables end-to-end automation of antenna array design and beam steering.

In this paper, we propose a multi-stage deep learning framework for conformal antenna array synthesis and beam steering in LEO satellite-based IoT networks. Our architecture integrates a machine learning module that predicts optimal geometric and material parameters based on mission-specific input features such as frequency, gain, satellite altitude, and surface curvature. These parameters are then passed to an offline reinforcement learning model based on the DQN algorithm, which learns to optimize beam steering strategies to maximize signal gain toward dynamic ground terminals.

To train both stages, we generate a static simulation dataset using CST Studio Suite and COMSOL Multiphysics, modeling realistic electromagnetic behaviors of curved antenna surfaces. The proposed system is validated through simulation, demonstrating that the ML-predicted parameters align closely with optimal configurations and that the RL policy enables effective adaptive beam steering under LEO satellite constraints.

This work highlights the power of combining ensemble machine learning with offline reinforcement learning for intelligent, scalable, and resource-efficient antenna design. It presents a viable alternative to traditional optimization techniques, particularly suited to constrained environments such as space-based IoT, where adaptability, efficiency, and autonomous operation are critical [

19].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Overview

This work proposes a two-stage model to optimize antenna array design for conformal applications by combining machine learning and reinforcement learning techniques as outlined in

Figure 1. The first stage involves predicting antenna geometric parameters using a stacking ensemble model. The second stage optimizes these parameters through a reinforcement learning approach to maximize beam steering performance.

2.2. Dataset Generation

To mitigate the challenges posed by the limited availability of real-world antenna datasets, we generate a synthetic dataset by applying statistical distributions to key antenna parameters, including resonant frequency, bandwidth, gain, and reflection coefficient [

1,

20]. These parameters are derived from fundamental antenna theory [

1], enabling the creation of a diverse dataset that significantly reduces the computational costs associated with traditional simulation-based methods [

21].

2.2.1. Antenna Gain Calculation

A key performance indicator of antenna design is the antenna’s

gain, which measures how well the antenna directs energy in a particular direction. To calculate gain, we use an

aperture efficiency model based on fundamental principles of antenna theory [

1,

22]. The gain

G is given by:

where:

is the wavelength of the signal,

d is the physical dimension (e.g., diameter of the antenna aperture),

e is the efficiency factor,

The term inside the logarithm represents the physical and geometric factors contributing to the antenna’s directivity and efficiency.

This model approximates the antenna’s gain based on its physical dimensions and efficiency, key factors influencing antenna performance [

1,

22,

23].

2.2.2. Resonant Frequency and Bandwidth

The

resonant frequency and

bandwidth are crucial parameters determining the antenna’s operational range [

1,

22]. These parameters are uniformly sampled within ranges observed from our CST simulations and reported literature [

1,

24] to ensure realistic variability.

Resonant frequency:

where

and

define the frequency range of interest.

Bandwidth:

where

and

define the bandwidth range.

The use of uniform distributions ensures exploration of a broad design space reflecting real-world antenna performance [

24].

2.2.3. Reflection Coefficient

The

reflection coefficient characterizes how well the antenna matches the transmission line [

1,

25]. Lower values indicate better matching and signal transmission efficiency.

We estimate

using the empirical relation [

26]:

where:

k is a sensitivity constant related to antenna design,

is the antenna’s effective radius or a related geometric feature,

is a baseline reference for effective radius,

is an offset constant related to baseline reflection characteristics.

This formulation provides realistic reflection characteristics based on physical dimensions and design parameters [

25,

26].

2.2.4. Synthetic Dataset Generation Procedure

To create the synthetic dataset, the following procedure is applied:

- (1)

Resonant frequency and bandwidth are sampled uniformly within ranges obtained from CST simulations and literature [

1,

25].

- (2)

Gain is computed using the aperture efficiency model to ensure realistic antenna performance [

1,

27].

- (3)

Reflection coefficient is estimated via the empirical formula to simulate antenna matching characteristics [

25,

26].

This approach yields a comprehensive dataset capturing the complex relationships among antenna parameters while avoiding the computational expense of full electromagnetic simulations. The dataset serves as a robust foundation for training machine learning models to optimize antenna array performance across diverse design spaces [

1,

25].

2.2.5. Reinforcement Learning Dataset

The dataset used for training both the Convolutional Neural Network and the Offline Reinforcement Learning Model consists of tuples with the following components in addition to the output from the stacking ensemble model:

Table 1.

Structure of each data sample used for training.

Table 1.

Structure of each data sample used for training.

| Component |

Description |

| State |

Phase distribution of a patch antenna array. Discrete values represent the state. |

| Action |

Phase change applied to each element: , 0, or . |

| Next State |

Resulting state after applying the action to the current state. |

| Gain Array |

Output from the stacking ensemble model: 360-length array, each index representing gain at a specific angle. |

| Max Gain Direction |

Angle corresponding to the maximum value in the gain array for the given configuration. |

| Reward |

Maximum gain in the direction computed from the next state. |

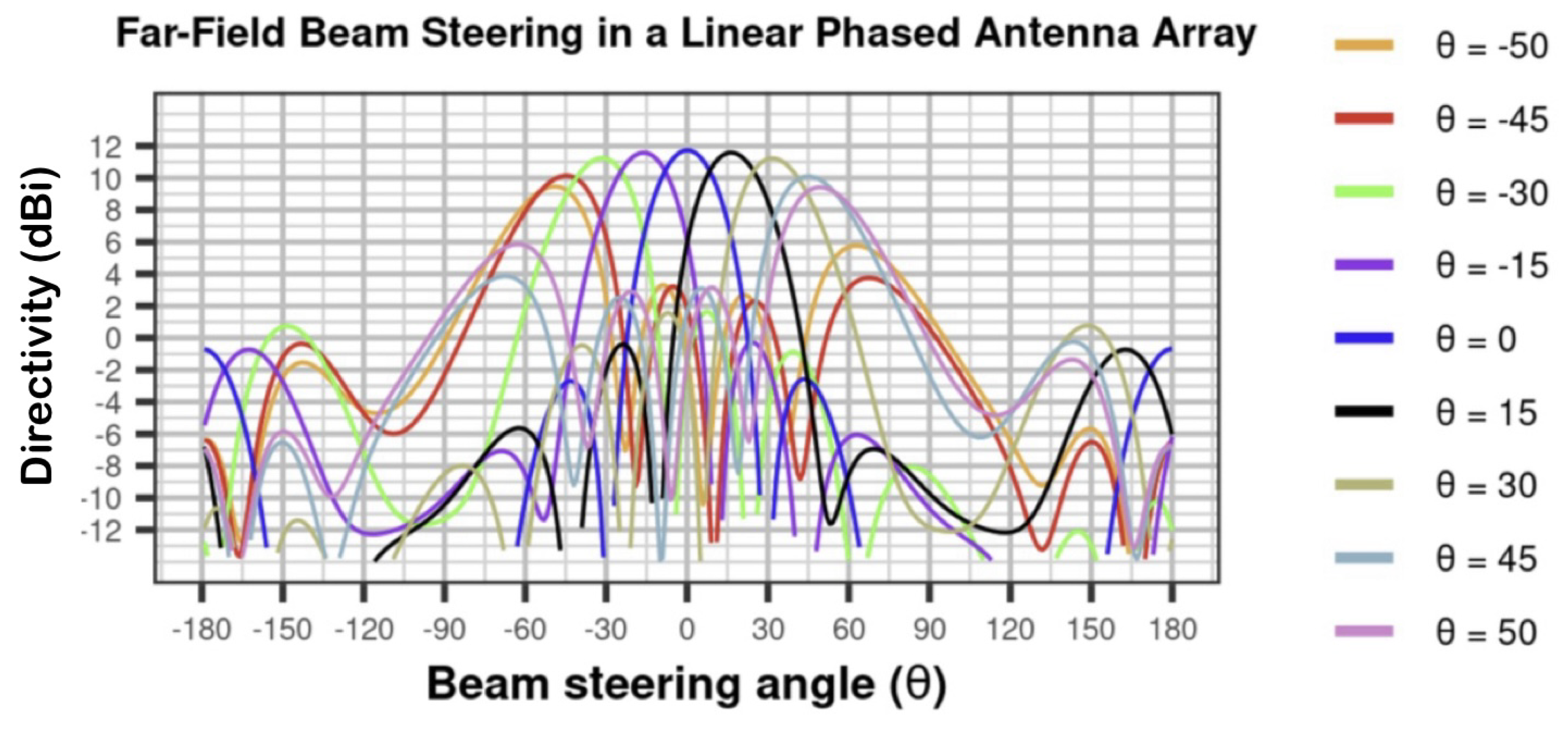

Figure 3 shows the 2D radiation pattern of a couple sample from our Reinforcement Learning Dataset with the current state represented in blue and next state in yellow.

Figure 2.

Heatmap of gain distribution across first 50 samples; The x-axis represents gain values; the y-axis denotes sample indices from 1 to 50.

Figure 2.

Heatmap of gain distribution across first 50 samples; The x-axis represents gain values; the y-axis denotes sample indices from 1 to 50.

Figure 3.

2D radiation pattern showing the state and next state values of 3 samples from the Reinforcement Learning Dataset with gain values measured in dBi.

Figure 3.

2D radiation pattern showing the state and next state values of 3 samples from the Reinforcement Learning Dataset with gain values measured in dBi.

2.3. Stacking Ensemble Model

The stacking ensemble model predicts the geometric parameters of the antenna array based on its input features. It integrates multiple learners to improve prediction accuracy.

2.3.1. Base Learner

A

Linear Regression (LR) model serves as the base learner, capturing linear relationships between input features and antenna parameters [

28].

2.3.2. Primary Learners

The primary learners consist of:

Support Vector Regression (SVR): Captures nonlinear relationships using kernel methods [

29].

Gradient Boosting (GB): An ensemble of weak learners to model complex data patterns [

30].

Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost): An optimized boosting algorithm that enhances model robustness and generalization [

31].

2.3.3. Meta Learner

A

Linear Regression meta-learner combines the outputs from the primary learners to generate final geometric parameter predictions [

32].

2.3.4. Input Features

The model inputs include key antenna geometric parameters, such as - array shape (e.g., linear, cylindrical), element spacing, element orientation, element size, surface curvature, operational frequency range, beamwidth, radiation pattern.

2.3.5. Output

The output is the predicted set of antenna geometric parameters used as input for the reinforcement learning optimization stage.

2.4. Reinforcement Learning Optimization

Reinforcement Learning (RL) is utilized to optimize the predicted antenna parameters by interacting with a defined environment and maximizing a reward signal based on beam steering performance [

15,

33].

2.4.1. Markov Decision Process Formulation

The RL problem is formulated as a Markov Decision Process (MDP) defined by:

2.4.2. Deep Q-Network (DQN)

A Deep Q-Network approximates the optimal action-value function using a neural network to select actions that maximize expected rewards [

15].

2.4.3. Batch DQN with Offline Learning

Batch DQN trains on a fixed dataset of experience tuples

to avoid costly real-time interactions [

35]. Experience replay buffers store these samples to improve learning stability.

2.4.4. Loss Function: Huber Loss

The Huber loss function is used for training, providing robustness against noisy data and outliers [

36]. It combines mean squared error and absolute error characteristics:

where

and

is a threshold hyperparameter.

2.4.5. Algorithm

The Batch DQN training procedure follows the standard update of Q-values with target networks and epsilon-greedy exploration. Pseudocode is provided in Algorithm 1. A fixed replay buffer is used to sample mini-batches of transitions, and target values are computed using the Double DQN strategy to mitigate overestimation bias. The Huber loss is used to stabilize training.

|

Algorithm 1 Batch DQN Algorithm |

|

3. Results

3.1. Ensemble Model Performance

This section presents the results of the proposed end-to-end model for optimizing conformal antenna arrays in IoT applications, focusing on the stacking ensemble model used for predicting antenna design parameters and the reinforcement learning (RL) optimization for beam steering. The evaluation metrics include prediction accuracy, optimization efficiency, and beamforming performance relevant to typical IoT communication scenarios.

3.1.1. Stacking Ensemble Model

The stacking ensemble model, incorporating Linear Regression (LR), Support Vector Regression (SVR), Gradient Boosting (GB), and Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) as base learners, demonstrated strong predictive capability for key geometric parameters of the IoT antenna array design [

37]. Performance was assessed by comparing predicted parameters against ground truth values from standard antenna design references [

38].

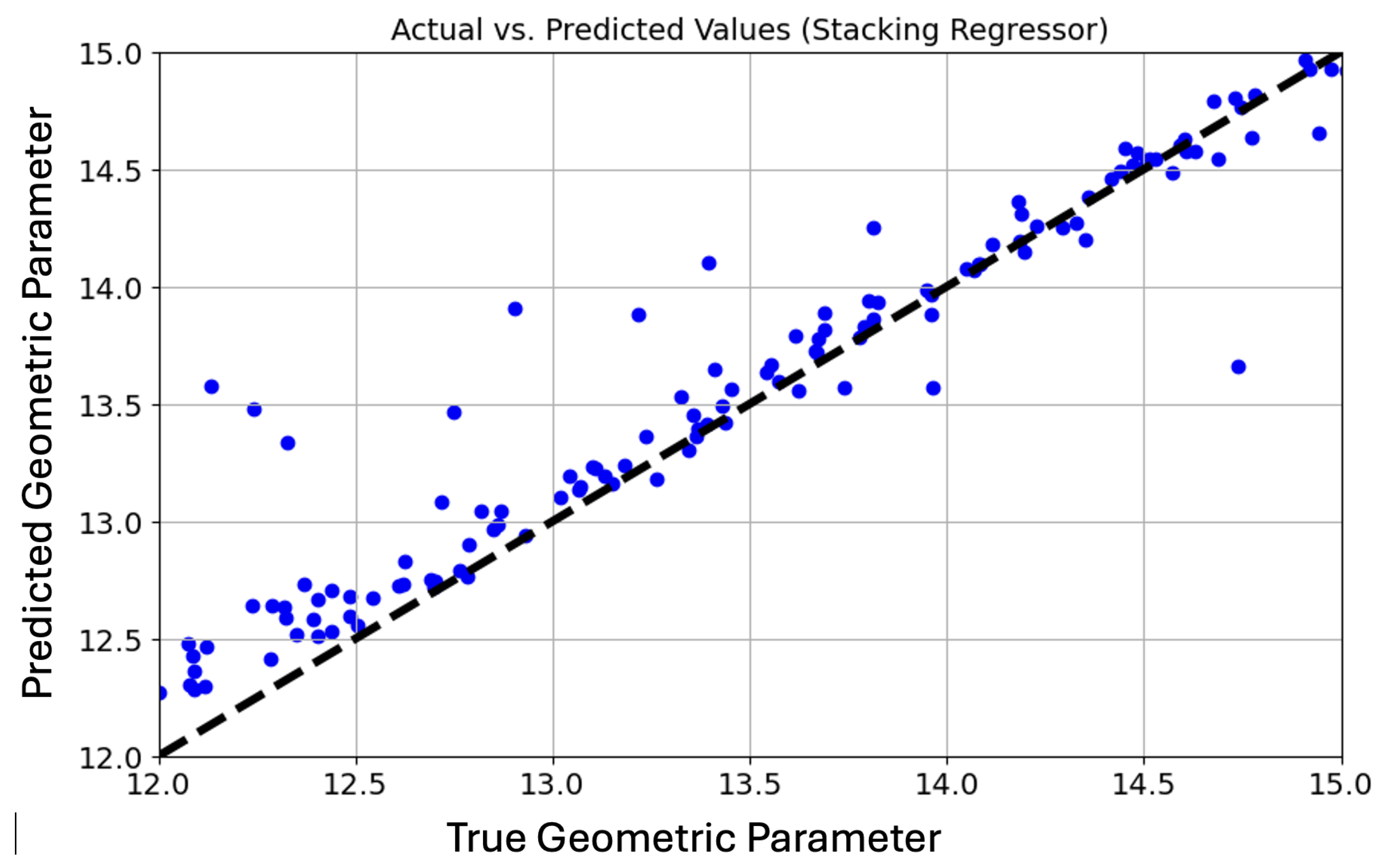

Figure 5 shows the plot of true values vs predicted values obtained from the stacking ensemble model.

Figure 4.

Plot of true geometric parameter Vs Predicted Geometric parameters showing the results of the proposed ensemble model.

Figure 4.

Plot of true geometric parameter Vs Predicted Geometric parameters showing the results of the proposed ensemble model.

Table 2.

Mean Squared Error (MSE) of Ensemble Learners for IoT Antenna Parameter Prediction.

Table 2.

Mean Squared Error (MSE) of Ensemble Learners for IoT Antenna Parameter Prediction.

| Model |

MSE |

| Base Model (Linear Regression) |

0.48 |

| Ensemble Model |

0.20 |

| Meta Learner |

0.22 |

| Overall Model (IoT Antenna Prediction) |

0.06 |

The stacking ensemble reduced the prediction error significantly, achieving an average MSE of 0.06. The meta learner, combining base models, provided robust parameter estimation that enables effective antenna optimization. An R² score of 0.91 confirms that the ensemble model explains 91% of the variance in antenna design parameters relevant to IoT devices.

3.2. Reinforcement Learning-Based Optimization for IoT Beam Steering

Predicted antenna parameters were input to the RL optimization stage in addition to the RL dataset, where a Batch Deep Q-Network (DQN) agent adjusted antenna array characteristics such as element spacing and orientation to maximize directional gain and signal quality in typical IoT operating bands (e.g., 2.4 GHz ISM band) [

39]. The offline learning approach minimizes the need for costly real-time experimentation, suitable for resource-constrained IoT environments.

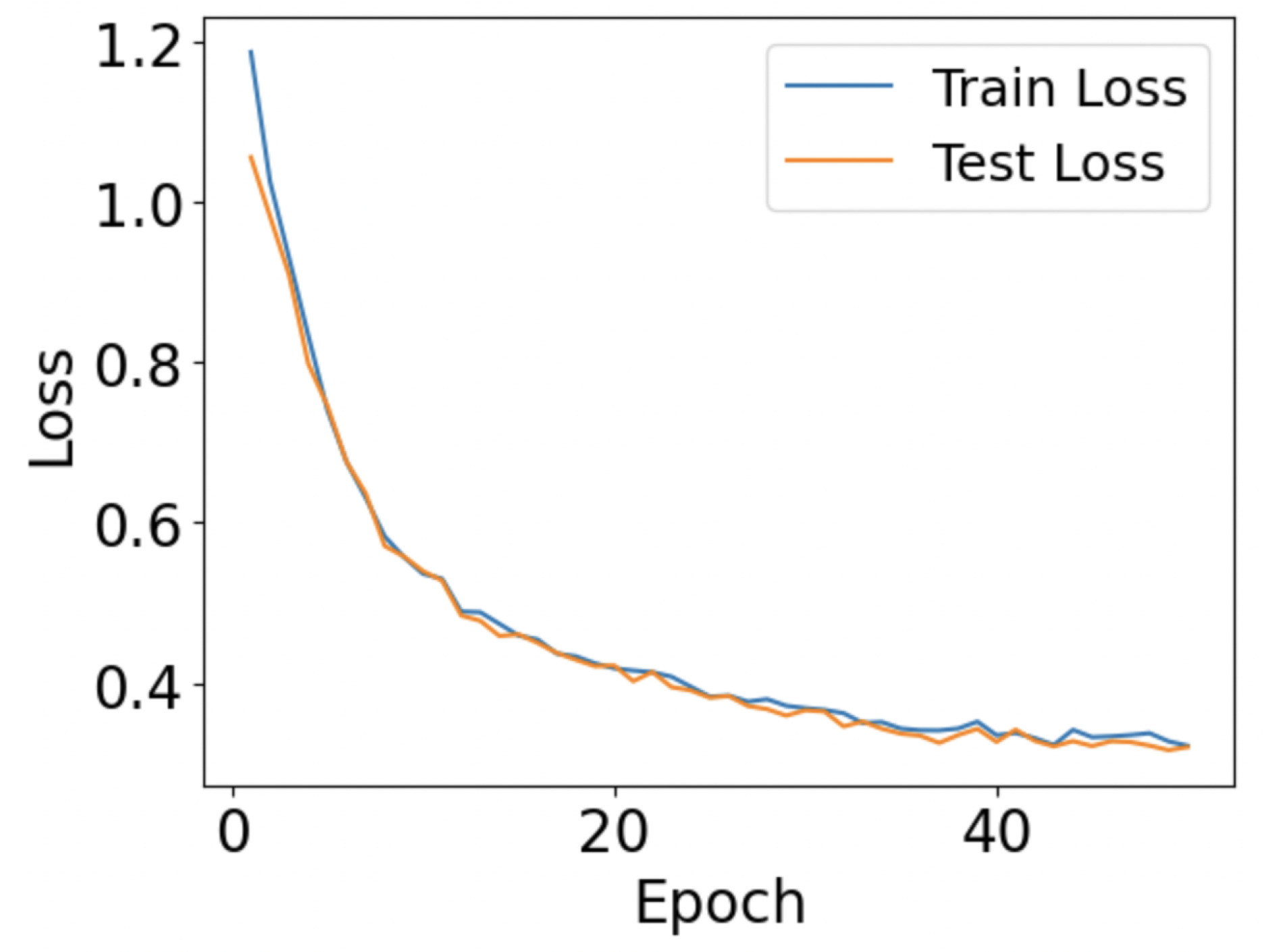

Figure 5.

The Rate of Convergence of the Proposed Reinforcement Learning Model showing the decrease in the training and testing loss over epochs.

Figure 5.

The Rate of Convergence of the Proposed Reinforcement Learning Model showing the decrease in the training and testing loss over epochs.

Optimization results were benchmarked against a baseline rectangular patch antenna and a traditional Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) algorithm [

40,

41].

Table 3.

Beamforming performance for IoT antenna array optimization.

Table 3.

Beamforming performance for IoT antenna array optimization.

| Model |

Gain (dB) |

Reflection Coefficient (, dB) |

| Baseline patch antenna array [37,38] |

8.5 |

-11 |

| PSO optimization [40,41] |

11.0 |

-14 |

| DQN optimization (proposed) |

12.5 |

-17 |

The proposed DQN model achieved the highest gain (12.5 dB) and best impedance matching ( of -17 dB), outperforming both the baseline and PSO optimization methods. These results demonstrate improved antenna performance critical for IoT devices, where enhanced beam steering improves communication range and reduces interference.

3.3. Generalization and Robustness

We tested the optimization model on a variety of IoT antenna array configurations with different element sizes and operating frequencies to assess robustness. The model consistently improved gain and reflection coefficient values across all configurations, validating its adaptability to diverse IoT hardware constraints.

Table 4.

Optimization Results on Various IoT Antenna Array Configurations.

Table 4.

Optimization Results on Various IoT Antenna Array Configurations.

| Configuration |

Gain (dB) |

(dB) |

| Small Element Size (Baseline) [1,42] |

8.0 |

-11 |

| Large Element Size (Baseline) [1,42] |

8.3 |

-11 |

| Small Element Size (Optimized) |

10.8 |

-15 |

| Large Element Size (Optimized) |

11.3 |

-16 |

These findings highlight the model’s capability to generalize antenna optimization across multiple IoT device form factors and environmental conditions.

Figure 6.

The synthesized antenna array’s gain values from CST simulations to cross validate the results from the proposed deep learning model.

Figure 6.

The synthesized antenna array’s gain values from CST simulations to cross validate the results from the proposed deep learning model.

3.4. Limitations and Future Directions

Despite promising results, the Batch DQN approach relies on pre-collected offline datasets, limiting adaptability to dynamic IoT environments with fluctuating signal conditions. Future work will integrate online learning and explore policy-gradient methods such as Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) to improve real-time adaptability. Additionally, extending the model to multi-band and multi-antenna (MIMO) IoT systems can further enhance communication reliability and throughput.

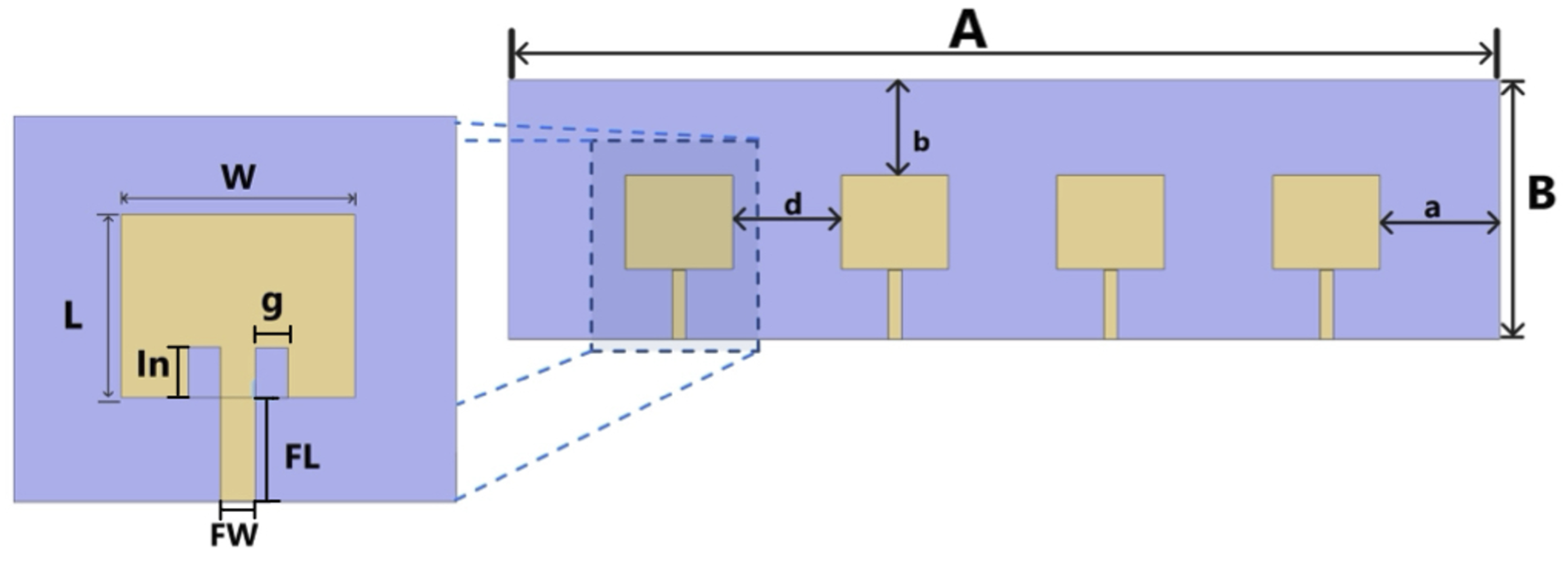

Figure 7.

An electromagnetic simulation of a 1x4 patch antenna array from CST validating the results of the proposed deep learning model; where A = 250 mm, B = 55.5 mm, L=W = 35.6 mm, FL = 9.7 mm, In = 1 mm, g = 1 mm, FW = 4.5 mm, d = 26.9 mm, a = 13.45 mm, and b = 10.2 mm.

Figure 7.

An electromagnetic simulation of a 1x4 patch antenna array from CST validating the results of the proposed deep learning model; where A = 250 mm, B = 55.5 mm, L=W = 35.6 mm, FL = 9.7 mm, In = 1 mm, g = 1 mm, FW = 4.5 mm, d = 26.9 mm, a = 13.45 mm, and b = 10.2 mm.

4. Discussion

This paper presents a novel approach to antenna array synthesis for IoT applications by integrating machine learning ensemble methods with reinforcement learning to predict and optimize antenna array geometric parameters for conformal and resource-constrained devices. Our method addresses traditional challenges in IoT antenna design, such as high-dimensional, nonconvex, and discontinuous optimization problems, which are often exacerbated by IoT devices’ size, power, and deployment constraints.

4.1. Strengths and Contributions of the Approach

The multi-model stacking ensemble used for predicting antenna parameters significantly improves prediction accuracy while reducing the need for extensive labeled datasets, which are difficult to obtain for diverse IoT antenna designs. By coupling this ensemble with offline reinforcement learning powered by a Deep Q-Network (DQN), the model iteratively refines antenna parameters to optimize beam steering performance without requiring costly real-time experimentation or physical prototyping.

Offline reinforcement learning is especially advantageous in IoT contexts, where devices are often deployed in environments where on-the-fly training or feedback collection is infeasible. Leveraging simulation data from tools like CST and COMSOL, our approach enables rapid and scalable training cycles while accommodating complex antenna geometries relevant to conformal and compact IoT antennas.

The results confirm that the predicted antenna parameters correlate well with simulation benchmarks, underscoring the model’s reliability and applicability for practical IoT antenna design tasks. This reduces reliance on time-consuming manual tuning and enables the development of optimized antenna arrays that improve communication range, energy efficiency, and interference mitigation in IoT networks.

4.2. Comparison with Traditional Methods

Conventional IoT antenna design methods, including manual optimization, evolutionary algorithms (e.g., PSO, Genetic Algorithms), or gradient-based techniques, typically require real-time interaction with physical devices or extensive iterative testing. These approaches are often computationally expensive and poorly suited for high-dimensional, nonconvex antenna design spaces typical of conformal IoT antennas.

Our integrated ensemble and reinforcement learning framework provides a scalable and efficient alternative. By decoupling training from real-time experimentation and employing a global optimization approach via reinforcement learning, it overcomes limitations of local optima entrapment and high computational cost. This enables faster convergence to optimal antenna configurations, which is critical for accelerating IoT device development and deployment cycles.

4.3. Practical Implications and Future Work

The proposed method has significant implications for IoT industries, including smart home devices, wearable sensors, and industrial IoT, where antenna performance directly impacts device reliability and network connectivity. The ability to autonomously optimize antenna arrays without physical trial-and-error expedites device prototyping and facilitates adaptive antenna designs that can adjust to dynamic deployment scenarios.

Nonetheless, some limitations warrant further investigation. The current reliance on simulation-generated offline datasets may not capture all environmental variables encountered by IoT devices in real-world deployments, such as multipath effects, interference, or device orientation variability. Incorporating real-world measurement data and online learning mechanisms will be essential to improve model robustness and adaptability.

Future work could also explore reinforcement learning algorithms beyond DQN, such as Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) or Advantage Actor-Critic (A2C), to enhance learning efficiency and adaptability in complex IoT antenna optimization problems. Expanding the approach to support multi-band antennas and MIMO (Multiple Input Multiple Output) systems would further broaden its applicability and impact across diverse IoT communication standards.

Overall, this research lays the groundwork for fully autonomous, efficient, and scalable antenna design frameworks tailored to the evolving demands of IoT technology ecosystems.

5. Conclusions

In this work, a novel, data-driven framework for antenna array synthesis in IoT applications was developed by integrating ensemble learning with offline reinforcement learning. The proposed method overcomes the spatial and hardware constraints of conventional design approaches by automatically learning the relationships among geometric parameters and optimizing beam-steering performance without relying on time-consuming physical prototyping. Experimental results demonstrate substantial gains: for small-element arrays, antenna gain increased from 8.0 dB to 10.8 dB and the reflection coefficient improved from –11 dB to –15 dB; for larger arrays, gain rose from 8.3 dB to 11.3 dB with enhancements from –11 dB to –16 dB. These findings confirm that the integrated learning-based approach significantly elevates array performance in resource-limited settings. By automating design and minimizing manual tuning, this framework establishes a scalable pathway toward adaptive, conformal antenna systems capable of meeting the dynamic demands of emerging IoT networks. Future work will focus on incorporating real-world deployment data and exploring advanced reinforcement-learning strategies to further improve robustness and generalization across diverse operational environments

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, VA; methodology, VA; software, VA; validation, DM, LR, and VA; formal analysis, VA; investigation, VA and LR; resources, DM, RG; data curation, LR; writing—original draft preparation, VA; writing—review and editing, DM, RG,MRA, SD; visualization, DM, VA, LR; supervision, DM; project administration, DM; funding acquisition, DM. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by WiSys and the Universities of Wisconsin applied research funding (Ignite Grant for Applied Research) under grant no. FY25-106-068000-4.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the support received from the Computer Science and Computer Engineering Department at the University of Wisconsin - La Crosse (UW-L) to pursue the research work. They would like to extend thanks to the Dean’s Distinguished Fellowship Committee at (UW-L) for providing Fellowship and supporting our work. AI assisted tools were used in the preparation of this manuscript for language editing.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Balanis, C.A. Antenna Theory: Analysis and Design; John Wiley & Sons, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, D.B.; de Paula, C.B.; Nascimento, D.C. Design Techniques for Conformal Microstrip Antennas and Their Arrays. Advancement in Microstrip Antennas with Recent Applications 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Veera S, A. ; J., S.; Kavitha, T. Conformal Antenna for Aircraft Applications. 11 2023, pp. 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Jensen, N.S.; Christiansen, L.H. Real-time Antenna Array Synthesis Using Machine Learning. TICRA News, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Usmani, W.U.; Chietera, F.P.; Mescia, L. Flexible Phased Antenna Arrays: A Review. Sensors 2025, 25, 4690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goudos, S. , Swarm intelligence algorithms for antenna design and wireless communications; 2018; pp. 755–784. [CrossRef]

- Valdez-Cervantes, L.; Núñez, C.; Ripoll, L.; Guerrero-Granados, B. Optimizing Linear Antenna Arrays with Genetic Algorithms. 08 2024, pp. 1–4. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Huang, D.; Niu, B.; Bai, M. High-efficient Optimisation Method of Antenna Array Radiation Pattern Synthesis Based on Multi-layer Perceptron Network. IET Microwaves, Antennas & Propagation 2022, 16, 763–770. [Google Scholar]

- Kirkpatrick, S.; Gelatt, C.D.; Vecchi, M.P. Optimization by Simulated Annealing. Science 1983, 220, 671–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suman, B.; Kumar, P. A survey of simulated annealing as a tool for single and multiobjective optimization. Journal of the Operational Research Society 2006, 57, 1143–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Misilmani, H.; Naous, T. Machine Learning in Antenna Design: An Overview on Machine Learning Concept and Algorithms. 07 2019. [CrossRef]

- Gajbhiye, P.; Singh, S.; Kumar Sharma, M. A comprehensive review of AI and machine learning techniques in antenna design optimization and measurement. Discover Electronics 2025, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramasamy, R.; Bennet, M.A. An Efficient Antenna Parameters Estimation Using Machine Learning Algorithms. Progress In Electromagnetics Research C 2023, 130, 169–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benoni, A.; Poli, L. Pattern Matching Approach for the Synthesis of Sub-Arrayed Linear Antenna Arrays. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Symposium on Antennas and Propagation and USNC-URSI Radio Science Meeting (AP-S/URSI); 2022; pp. 1620–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mnih, V.; Kavukcuoglu, K.; Silver, D.; et al. Human-level control through deep reinforcement learning. Nature 2015, 518, 529–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lillicrap, T.P.; Hunt, J.J.; Pritzel, A.; et al. Continuous control with deep reinforcement learning. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1509.02971. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, B.; Jin, C.; Cao, K.; Lv, Q.; Mittra, R. Cognitive Conformal Antenna Array Exploiting Deep Reinforcement Learning Method. IEEE Transactions on Antennas and Propagation 2022, 70, 5094–5104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hessel, M.; Silver, D.; Van Hasselt, H.; et al. Rainbow: Combining Improvements in Deep Reinforcement Learning. Proceedings of the 32nd International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, 2018; 3216–3224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadiq, M.; Sulaiman, N.; Isa, M.; Hamidon, M.N. A Review on Machine Learning in Smart Antenna: Methods and Techniques. TEM Journal 2022, 11, 695–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, S.C.; McAllister, P.E.; Kelsall, T. Antenna Engineering Handbook, 4th ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Y.; Chen, L.; Zhang, Y.; Shen, M.; Wang, H.; Wang, X.; van Rechem, C.; Fu, T.; Wei, W. Machine Learning for Synthetic Data Generation: A Review. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2302.04062v10. [Google Scholar]

- Kraus, J.D.; Marhefka, R.J. Antennas: For All Applications, 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Tse, D.; Viswanath, P. Fundamentals of Wireless Communication; Cambridge University Press, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Rana, M.; Rahman, M. Study of Microstrip Patch Antenna for Wireless Communication System. 01 2022, pp. 1–4. [CrossRef]

- Pozar, D.M. Microwave Engineering, 4th ed.; John Wiley & Sons, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Landron, O.; Feuerstein, M.; Rappaport, T. A comparison of theoretical and empirical reflection coefficients for typical exterior wall surfaces in a mobile radio environment. IEEE Transactions on Antennas and Propagation 1996, 44, 341–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rappaport, T.S. Wireless Communications: Principles and Practice, 2nd ed.; Prentice Hall, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop, C.M. Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning; Springer, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Vapnik, V. The Nature of Statistical Learning Theory; Springer, 1995.

- Friedman, J.H. Greedy Function Approximation: A Gradient Boosting Machine. The Annals of Statistics 2001, 29, 1189–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A Scalable Tree Boosting System. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining; 2016; pp. 785–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolpert, D.H. Stacked Generalization. Neural Networks 1992, 5, 241–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, R.S.; Barto, A.G. Reinforcement Learning: An Introduction; MIT Press, 2018.

- Bellman, R. Dynamic Programming; Princeton University Press, 1957.

- Fujimoto, S.; Meger, D.; Precup, D. Off-Policy Deep Reinforcement Learning without Experience Replay. Proceedings of the 34th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML) 2019, 3, 2051–2060. [Google Scholar]

- Huber, P.J. Robust Estimation of a Location Parameter. Annals of Mathematical Statistics 1964, 35, 73–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattar, S.E.; Baghdad, A. Design and optimization of a rectangular microstrip patch antenna for dual-band 2.45 GHz/ 5.8 GHz RFID application. International Journal of Electrical and Computer Engineering (IJECE) 2022, 12, 5114–5122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullen, A. Microstrip Antenna Theory and Design. Electronics and Power 1982, 28, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, R.; Haque, M.J.; Samsuzzaman, M.; Masud, M.A.; Azim, R.; Hossain, I. Patch Antenna Design and Optimization Using Machine Learning Techniques. In Proceedings of the 2024 6th International Conference on Sustainable Technologies for Industry 5.0 (STI); 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, N.; Rahmat-Samii, Y. Particle Swarm Optimization for Antenna Designs in Engineering Electromagnetics. Journal of Artificial Evolution and Applications 2008, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlosser, E.R.; Tolfo, S.M.; Heckler, M.V.T. Particle Swarm Optimization for antenna arrays synthesis. In Proceedings of the 2015 SBMO/IEEE MTT-S International Microwave and Optoelectronics Conference (IMOC), Nov 2015; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tawk, Y.; Ghaddar, S. Design of a Microstrip Patch Antenna for IoT Applications. International Journal of Antennas and Propagation 2019, 2019, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).