Introduction

One of the most studied potential adverse effects of the long-term use of PPIs is dementia [

1]. An early and large epidemiological study based on the German ageing, cognition, and dementia databases showed a significantly elevated risk of developing dementia in patients exposed to long-term PPI therapy [

2]. A subsequent study conducted on a longitudinal sample of elderly patients from the largest German statutory health insurer also showed an increased risk of developing dementia compared with patients not exposed to PPIs [

3].

A weakly but significantly increased risk of non-AD dementia was observed among PPI users in a community-based retrospective cohort study was conducted in the Catalan health service (CatSalut) system from 1st January 2002 to 31st December 2015. Despite a higher dose of PPIs was not associated with an increased risk of either AD or non-AD dementias, it has been observed an increased risk of both AD and non-AD dementias in users of two types of PPI in the above mentioned 13 years of community-based data compared with those who employed only one type [

4].

Conversely, a few recent meta-analyses and systematic reviews have concluded that there was no statistically significant association between PPI use and risk of dementia or AD (P >.05) [

106,

107,

108].

However, these controversial findings claimed that distinct PPIs may have a potential role in the progression of cognitive disorders.

Despite these studies, the bioinformatics-based evidence from our current study led us to explore the relationship between PPIs and AD as well as non-AD dementias. In particular, we aimed to review the relationship between PPI use and the basic mechanisms of neuronal dysfunction. In this regard, we discuss if PPI utilization is associated with greater susceptibility to developing dementia, focusing on a neurobiological basis of AD. Consequently, we propose a novel hypothesis regarding the physio-pathological mechanisms of cognitive impairment induced by acute and chronic PPI use and examine some associated factors that can increase dementia susceptibility after PPI exposure.

Limitations:

Our review has certain limitations such as the study was confined only to bioinformatics. These bioinformatics were performed based on earlier evidences and so it is reliable to perform some wet lab experiments as per our current findings. Some earlier studies which contradict on facts can be better proven with wet lab experiments. This study has limitations because it shows the silico interactions among drug and protein but whether it's truly possible in vivo needs further studies keeping this information as base.

Methodology for Docking Study

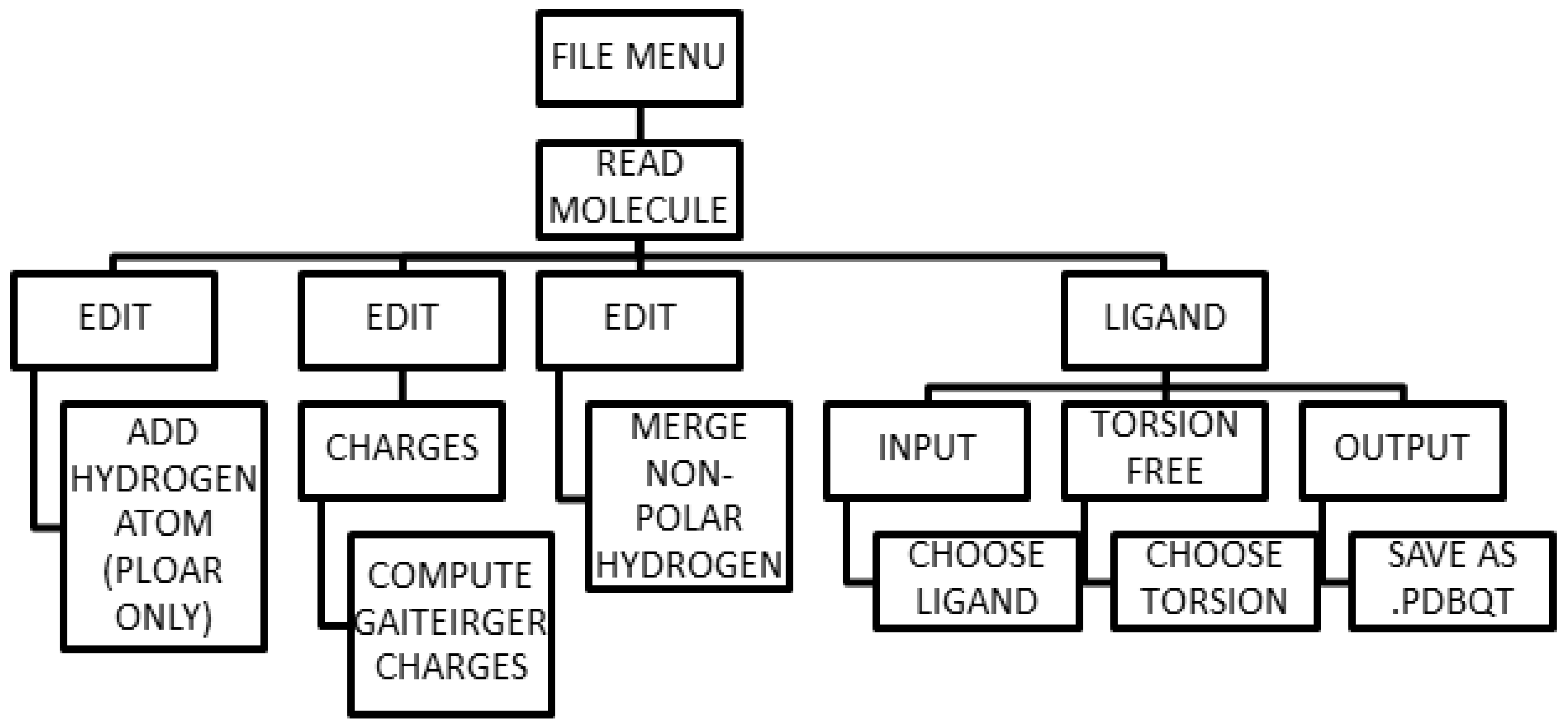

The structure of protein and ligands were downloaded from websites

https://www.rcsb.org/ and

https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/. AutoDock Tool 1.5.6 [ATD] was utilized for this study. The AutoDock Vina 1.0 software automatically computed Gasteiger charges, merged non-polar hydrogens, and autodock type to each atom. Then torsions were defined, which showed rotatable and non-rotatable bonds in the ligand. Finally, results were saved in pdbqt file format (see

Figure-i and

Figure-ii). AutoDock Vina software was run using the Windows command prompt. All the programme files, ligand [.pdbqt], protein [.pdbqt] and configuration files [.conf] were saved in same folder. The computation was performed in the same folder as log .txt and ligand_out.pdbqt. Log .txt file showed binding energy of ligand to the protein and ligand_out.pdbqt file revealed sites on the proteins with binding energy. The output [.pdbqt] files obtained from the docking study were used to evaluate the hydrophobic interaction of the ligand with protein. The results were then processed with chimaera software version 1.8 for the creation of copies of protein as well as ligand. This was followed by an assessment of interactions between protein and ligand by using ligplot+ version 1.4.5 [

5,

6,

7,

8].

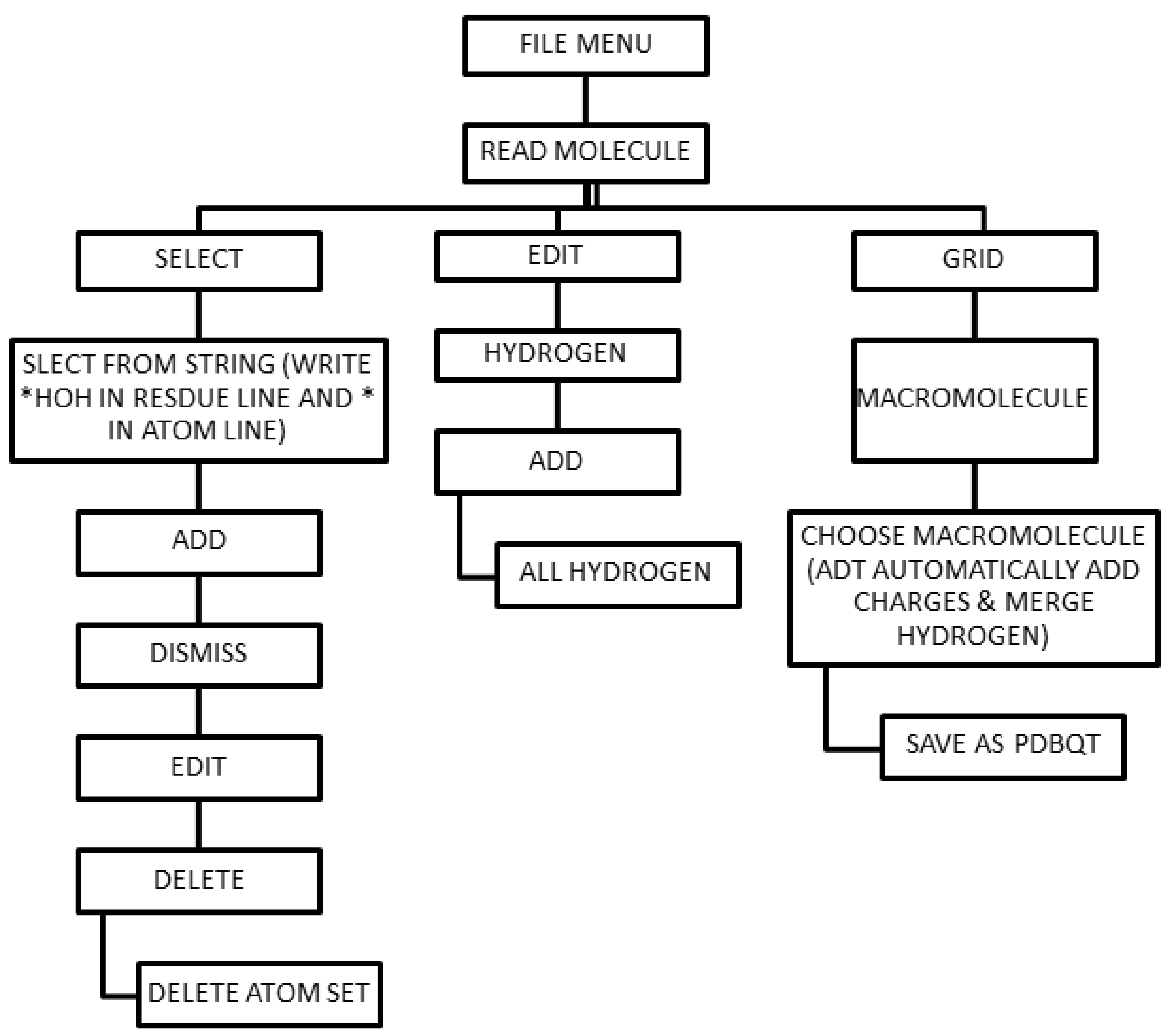

Determination of Grid Box Size

The grid box should enclose the known binding site. It should be large enough to accommodate the largest ligand under consideration. It should provide enough room for flexible residues to manoeuvre. If the binding site on the receptor is known, then a smaller grid box will help in the reduction of docking time and increase the accuracy. Figure-iii explains the procedure we adapted to fix the grid box size and noted the values. These values were used to run AutoDock Vina (

Figure-iii).

Figure-i.

Detailed procedure for preparation of .pdbqt file is shown in Figure i &ii.

Figure-i.

Detailed procedure for preparation of .pdbqt file is shown in Figure i &ii.

Figure-iii.

Determination of Grid box size.

Figure-iii.

Determination of Grid box size.

Results

PPI Interaction with GABAA Receptor

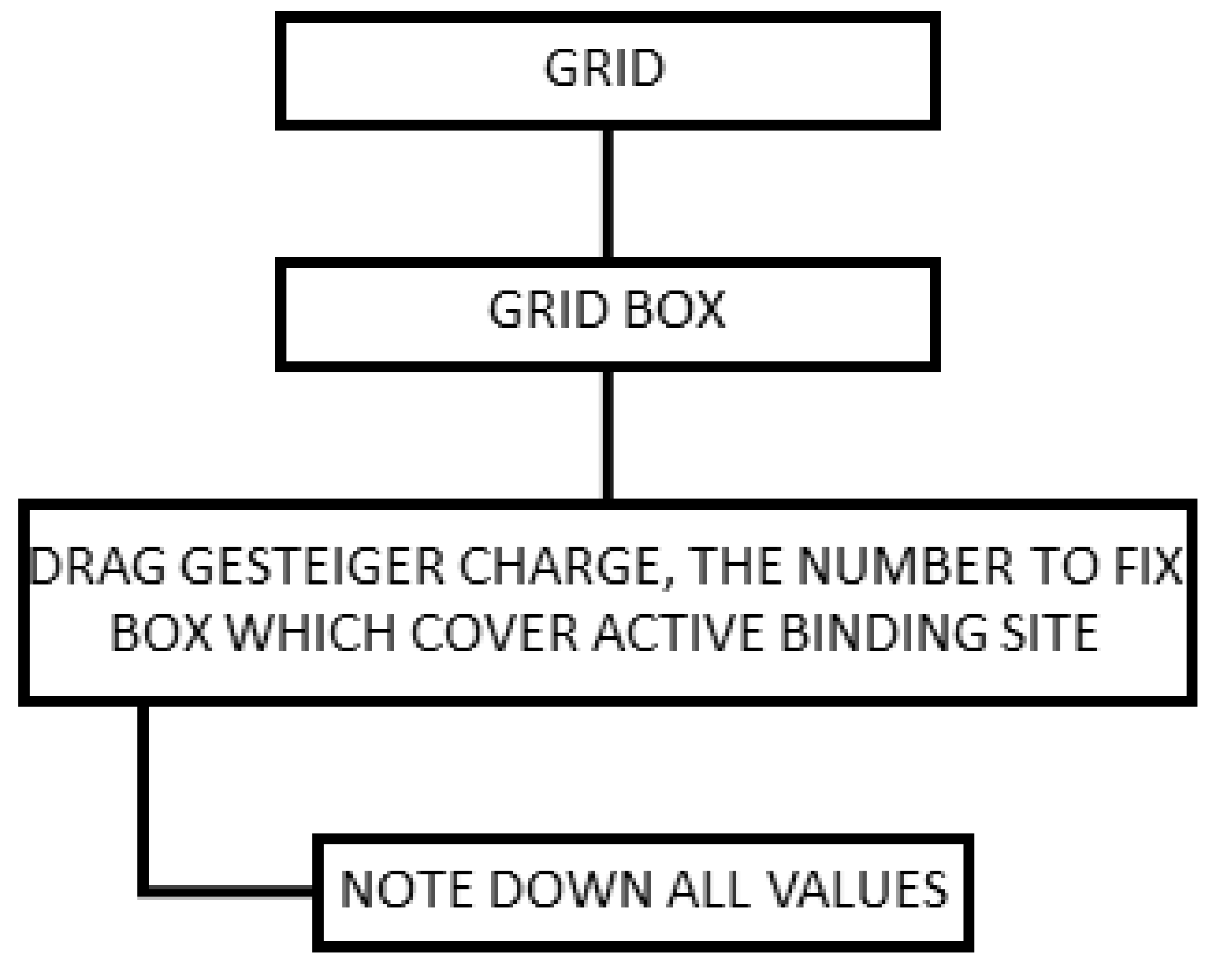

Comparative analysis of the binding ability of benzodiazepines and PPI to GABA

A R showed that PPI binds to GABA

A R in an almost similar fashion with high affinity, and lower binding energy compared to benzodiazepines and more hydrophobic interactions that increase the chances of easy binding. Therefore, it can be assumed that PPI may activate GABA

A R similar to Benzodiazepines. Consequently, PPI may lead to neuronal degeneration possibly causing dementia or AD (

Table 1,

Figure 1).

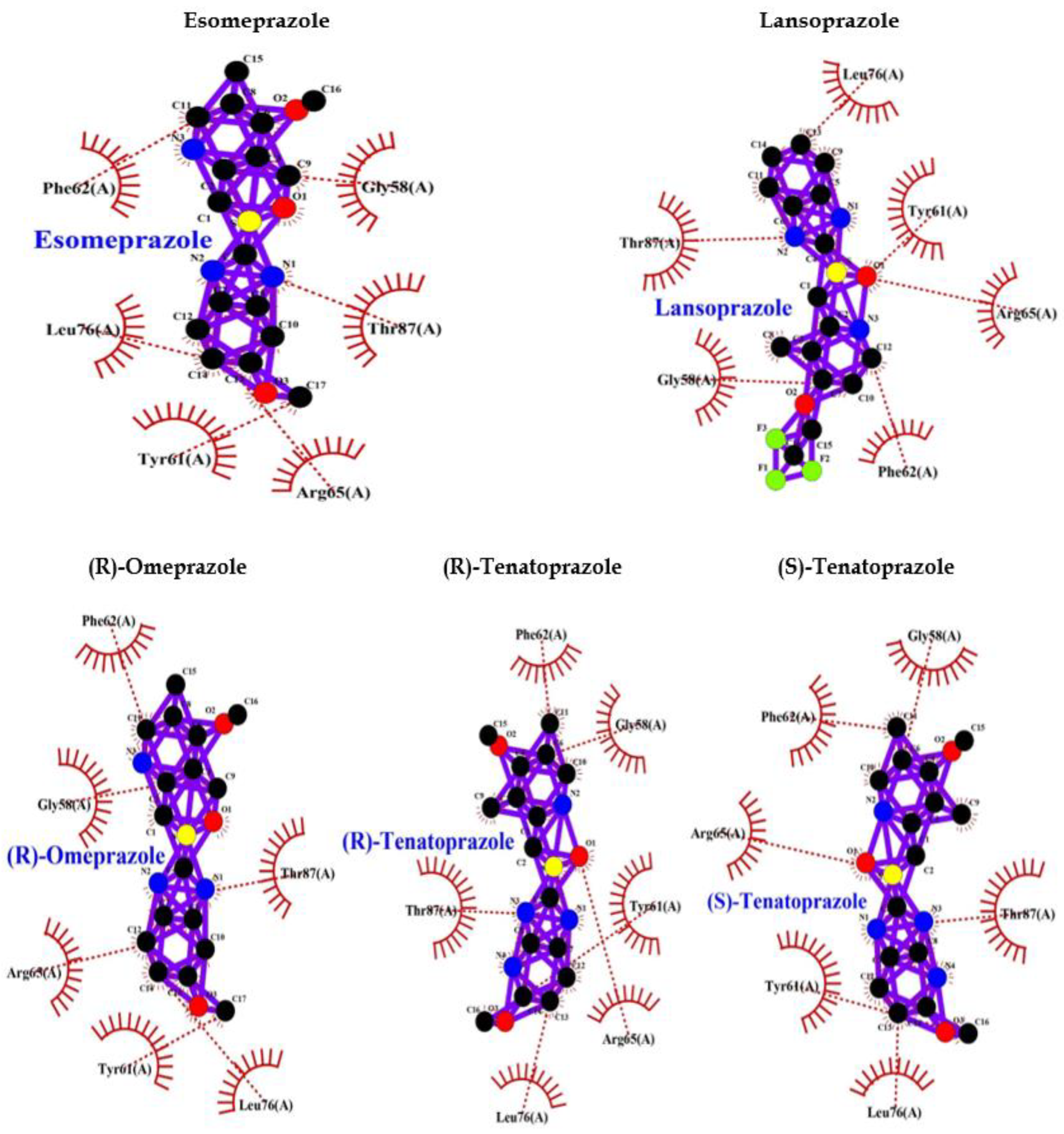

PPI Interaction with AMP-Activated Protein Kinase (AMPK)

PPI such as (R)-(+)-Pantoprazole, Esomeprazole, Lansoprazole, (R)-Omeprazole, (R)-Tenatoprazole, (S)-Tenatoprazole binds to AMPK with less energy compared to known (Dorsomorphin) of AMPK. Interaction bonds contain the number of amino acids with hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic bonding. The data have been shown the lowest level of energy in the binding site. Thus, PPI can be a potential inhibitor of AMPK and its long-term use may keep inhibiting AMPK for the long term and thus may allow AD or dementia development (

Table 2,

Figure 2).

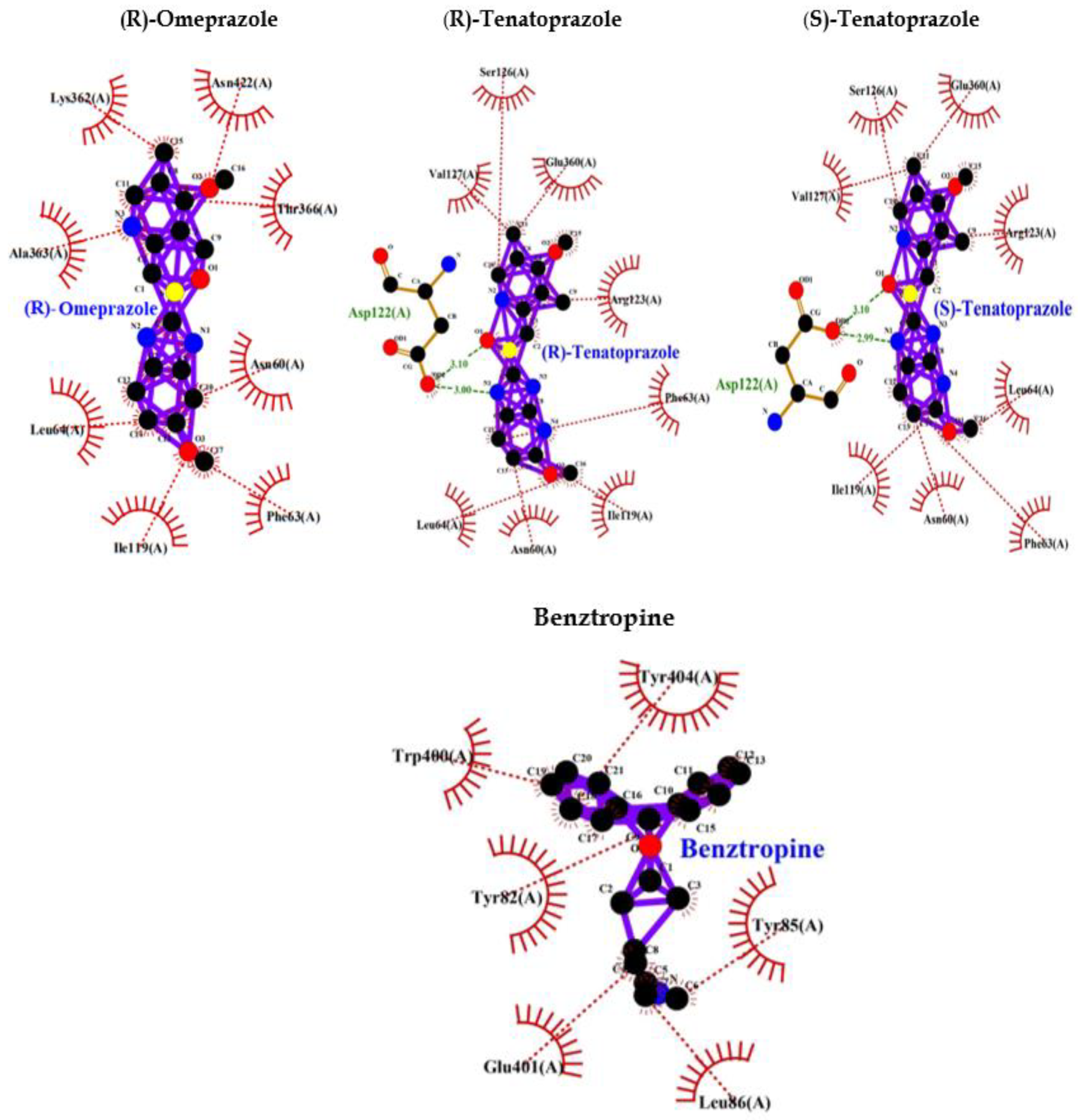

PPI Interaction with M1 Muscarinic Acetylcholine Receptor (M1 mAChR)

Benzotropine is a known inhibitor of M1 mAChR. It shows binding energy of -9.0 and a few hydrophobic bonds with no hydrogen bonds. Whereas PPI shows interaction bonds of aminoacids with hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic bonding along with binding energy lower than Benzotropine. These data indicate the lowest level of energy in the binding site and thus PPI can efficiently bind to M1 mAChR and inhibit it as benztropine (

Table 3:

Figure 3).

The buildup of beta-amyloid has been implicated in the progression and pathogenesis of dementia syndromes such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD) in humans. Central nervous system (CNS) microglial cells use enzymes such as V-ATPase to degrade and scavenge beta-amyloid [

2].

Murine models suggest that PPIs interfere with the activity of scavenger enzymes such as V-ATPase leading to the accumulation of beta-amyloid [

9]. PPIs have been also associated with certain chronic kidney disease (CKD) that may also lead to cognitive impairment, dementia, or AD. Further studies are needed to elucidate the mechanisms linking PPIs with dementia in humans. In the current study we have considered various CNS-associated proteins by previous studies such as Tau aggregation beta-amyloid accumulation, to find what type of effects, PPI may have on CNS.

Kidney disease case reports have linked PPIs to acute interstitial nephritis (AIN) and acute kidney injury (AKI) since 1992. In 2016, two studies received widespread attention because they connected PPIs to an excess risk for CKD [

10,

11]. Data retrieved retrospectively from a cohort of 10,482 patients who were actively followed and another larger cohort of 249,751 patients, it was found that PPIs were associated with a 50% increased risk in the smaller cohort and a 17% risk increase for CKD in the larger cohort.

Another study compared 173,321 PPI users with 20,270 H2RA users in a VA dataset [

11], they included patients who had a normal Glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) at baseline and followed patients for up to 5 years and found a 1.8% absolute annual excess risk for CKD in PPI users compared to H2 receptor antagonists (H2RAs).

These studies are thought-provoking since PPI’s effect on the kidney may vary with the degree of severity within important comorbidity categories such as diabetes [

9].

Evidence also exists that CKD is a risk factor for cognitive decline. Earlier studies explain that kidney disorder may be an important mechanism leading to cognitive impairment [

12]. Cognitive dysfunction is a well-known complication of CKD [

13]. AKI patients have a 3-fold more risk of developing dementia compared with those without AKI. The association of AKI with dementia or death is valid in several studies and shows an increased risk of 60% [

14].

How AKI may lead to cognitive dysfunction is unclear, but increased inflammation, oxidative stress, and endothelial dysfunction are all described complications of AKI [

15,

16,

17]. In mice models, ischemic AKI resulted in inflammation and functional changes in the brain specifically, compared with sham mice, those with AKI had increased neuronal pyknosis and microgliosis in the brain [

17]. In addition, the mice with AKI had significant microvascular dysfunction in the brain. Whether these changes occur in humans has not been determined and further study is required. AKI is associated with long-term adverse outcomes. A significantly increased risk of dementia following AKI has been reported in patients without a previous history of cognitive dysfunction [

13]. In a previous study performed in Taiwan of 2,905 patients with AKI had a greater risk for subsequent development of dementia than those without AKI independent of cardiovascular risk factors [

18]. PPI use is associated with an increased risk of acute kidney injury (AKI), incident CKD, and progression to end-stage renal disease (ESRD), ultimately participating in cognitive impairment [

19].

The Effect of PPIs on the Central Nervous System

AD or dementia is caused by the deposit of β-amyloid and hyperphosphorylated tau protein in the brain of the patients, while in frontotemporal lobar degeneration deposits of Tau or TDP-43 can be characterized or Lewy body dementia, which is characterized by the presence of alpha-synuclein deposits [

20,

21,

22,

23].

Symptoms may be similar in different cognitive disorders at very early and also in the final stages of the disease, making the differential diagnosis difficult. However, the causes of neurodegeneration are different in each one of them. Evaluating the risk of PPIs on dementia, AD as a whole may provide essential insights into the disease. In this review, we will be discussing how PPI may affect CNS, neurodegeneration via different modes.

PPI may inhibit -ATP12A/ ATP1AL1 (Alpha Polypeptide) Gene Product

The ATP12A/ATP1AL1 genes encode H+/K+-ATPase, which is expressed in the brain, colon, and placenta, while the ATP4A gene encodes H+/K+-ATPase in gastric epithelial cells. RNA blot analysis revealed that the colon had the highest levels of expression, whereas the kidney, uterus, heart, and forestomach had the lowest levels [

109]. Moreover, this study has also shown the interaction of H+/K+-ATPase in gastric epithelial cells with rabeprazole and omeprazole [

24,

25]. A few other isoforms of the H+/K+ -ATPase are expressed in the central nervous system (CNS) which maintains acid-base and potassium homeostasis in neurons [

24,

26]. V-ATPases are involved in both exocytosis and endocytosis in nerve terminals and are needed for the packing of neurotransmitters into synaptic vesicles by generating a proton gradient [

27,

28]. PPIs including omeprazole, lansoprazole, dexlansoprazole, rabeprazole, pantoprazole, and esomeprazole bind to H+/K+ - ATPases efficiently on the parietal cell membrane's luminal surface and inhibit acid secretion [

29,

30]. Most of the PPIs react with cysteine 813 though the site of reaction on the enzyme differs according to the type of PPI [

30]. Due to the homology properties of P-type ATPase’s, PPIs can plausibly inhibit even other ionic pumps in CNS and elsewhere. Hence, PPI may reduce pH in the brain, cerebrospinal fluid, and blood by inducing metabolic alterations.

According to the measurement of PPI passage through the blood-brain barrier, up to 15% of a single intravenous dose of omeprazole will pass through the blood-brain barrier and enter the CNS [

31]. Repetitive long-term use and 15% of this drug at each dose can potentially become a risk for the brain and can cause cognitive dysfunction. Lansoprazole has also been shown (in vitro and in vivo) to penetrate BBB [

32]. Lansoprazole, esomeprazole, and pantoprazole have been associated with headaches, dizziness, nervousness, tremor, sleep disturbances, and depression [

33,

34,

35]. There have also been reports of senso-perceptual abnormalities (i.e., hallucinations) [

36] and delirium [

37] in very rare cases. Although the exact mechanisms of action of PPI on brain circuits and neurological side effects are not fully understood [

38]. PPI drugs can facilitate tau and Aβ-induced neurotoxicity, which may increase AD progression and cognitive decline. Below, we discuss the most relevant physiopathological mechanisms.

PPIs and Aβ Plaques

Dementia build-up of β-amyloid (Aβ) protein predisposes to AD. Microglial cells use V-type ATPases to degrade amyloid-β, and PPIs may block V-ATPases to increase isoforms of amyloid-β in mice [

39]. PPIs increase the development of Aβ plaques, which is one of the most well-known factors in the case of dementia [

39]. Extracellular aggregation of Aβ plaques, which leads to oxidative and inflammatory damage in the brain, is one of the main hallmarks of AD. Aβ is produced through the proteolytic processing of a transmembrane protein, amyloid precursor protein (APP), by β-secretases (also known as β-site APP-cleaving enzyme 1 [BACE1]) and γ-secretases.

Amyloidogenic processing of APP is carried out by the sequential action of membrane-bound β- and γ-secretases. β-Secretase cleaves APP into the membrane-tethered C-terminal fragments β (CTFβ or C99) and N-terminal sAPPβ. CTFβ is subsequently cleaved by γ-secretases into the extracellular Aβ and APP intracellular domain (AICD) [

40]. Although the total number of Aβ plaques does not correlate well with AD severity, there is a direct effect on cognition and cell death in APP/tau transgenic mice because of neuronal loss and the astrocyte inflammatory response investigated the effect of PPIs on Aβ production using cell and animal models and suggested a novel hypothesis that considers PPIs as acting like inverse γ-secretase modulators (iGSM), which change the γ-secretase cleavage site and thereby increase Aβ42 levels and decrease Aβ38 levels [

39,

41]. PPIs also increase BACE1 activity, thereby increasing levels of Aβ37 and Aβ40. In AD, the major pathological species is thought to be Aβ42, but the most produced is Aβ40 [

42]. PPIs and specifical lansoprazole was also noticed to alter the media pH responsible for amplifying the activity of other proteases, such as memprin-β, and generating Aβ2-37, Aβ2-40, and Aβ2-42 species. Moreover, Badiola et al. were able to demonstrate that lansoprazole enhances Aβ production using in vivo and in vitro models, supporting the theory that PPIs affect AD by boosting Aβ production [

39,

41]. PPIs inhibit vacuolar proton pumps (VPP) in microglia and macrophages, VPP acidifies lysosomes by pumping protons from the cytoplasm into the lumen of vacuoles [

43,

44]. This acid environment in lysosomes causes the degradation of fibrillary Aβ. As PPIs can cross the BBB, they act on V-ATPases in an inhibitory way, causing less degradation of fibrillary Aβ and hence a reduction in its clearance [

31,

44]. To date, few studies have explained the relationship between the effects of PPIs and the presence of Aβ plaques. It would be interesting if future studies determine why Aβ plaque production increases or their clearance decreases with PPI use. Results from solid-state NMR measurements showed that amyloid fibril “cross β” structures are of two patterns: parallel and antiparallel. Transglutaminase (tTG) causes crosslinking of Aβ peptides and indicates that the Aβ fibril is a hydrogen-bonded, parallel β-sheet with the propagation long axis of the Aβ fibril [

45]. Similar to human AD cases, tTG was related to Aβ depositions in these AD models. Evidence for an early role of tTG in Aβ pathology was given in an earlier study [

46].

One of the oxidative modifications involved in mediating Aβ toxicity through Aβ aggregation is the formation of dityrosine cross-links. Several studies have shown that Aβ can be converted to dityrosine through two different biochemical pathways. One method is peroxidase-catalyzed cross-linked tyrosine and the second method is metal-catalyzed oxidative tyrosyl radical formation [

47,

48,

49,

50]. At certain concentrations omeprazole induced HO-1 which also increased H2O2 levels [

51,

52]. This increased hydrogen peroxide due to PPI use may cause the formation of dityrosine cross-links which leads to the formation of Aβ aggregation that ultimately leads to cognitive impairment or dementia or AD.

Role of PPI on Tau Protein

A definitive diagnosis can only be confirmed histopathologically by the extensive presence of Aβ and neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) in the neocortex of post-mortem brain tissue [

53]. The main component of NFTs is paired helical filaments (PHFs) formed from hyperphosphorylated tau protein [

54,

55]. Tau protein acts as a microtubule-associated protein in neuronal axons, stabilizing and inducing microtubule assembly [

56]. When tau protein is hyperphosphorylated, it loses its ability to bind and stabilize microtubules, resulting in neuron degeneration [

57]. According to the neuro-immunomodulation hypothesis of AD, the earliest CNS modifications before the clinical onset of AD are caused by a persistent inflammatory reaction, which causes excessive tau phosphorylation and triggers the development of PHFs and tau protein aggregates, eventually leading to cytoskeletal changes [

58]. As a result, these lesions exist before the onset of clinical signs of AD [

59]. They looked at over 2000 compounds to find agents for PET and discovered that quinoline and benzimidazole are high-affinity components of NFTs, and not senile plaques [

59]. A docking experiment discovered significant hydrogen bond interactions between the NH group of lansoprazole's benzimidazole ring and the tau core's C-terminal hexapeptide (386TDHGAE391) [

58]; lansoprazole has high lipophilicity and can cross the BBB, within 37 min and can reach the brain; therefore, indeed it has also been used as a radiotracer for PET imaging [

60]. Tau undergoes multiple posttranslational changes resulting in conformational modifications in aggregates that alter binding affinities and binding sites of tau protein [

60]. Lansoprazole, indeed with its high affinity for tau protein and can be used to create noninvasive techniques for diagnosing AD in the early stages. This has been proved that Tau protein effectively binds to PPI such as lansoprazole. Thus, the effect of other PPI on Tau protein and its affinity may also increase aggregation and stabilize tau aggregates. It's worth noting that TSP1 usually forms disulfide-linked trimers; it's unclear if proteins with a proclivity for multimerization are more sensitive to omeprazole, but direct towards further investigation [

61].

The appearance of abnormal phosphorylation of the microtubule-associated protein tau in the brains of patients with AD is a key characteristic of the disease's development. Identification of the kinases involved in this mechanism, as well as the development of pharmacological agents to inhibit these molecules, has been a major focus of research. This analysis focuses on recent advances in Tau phosphorylation's physiological and pathological effects, as well as the role of phosphorylation in Tau toxicity and pathological progression in AD. Therapeutic research is being reshaped by the emerging understanding of Tau's functions in cellular biology and the mechanisms by which phosphorylation controls Tau activity [

62].

The balance of Tau kinase and phosphatase activities controls Tau phosphorylation. This equilibrium has been proposed to be disrupted, which may lead to abnormal Tau phosphorylation and hence Tau aggregation. Thus, identifying the potential causes of Tau aggregate development and developing defense methods to deal with these lesions in AD necessitates a thorough understanding of Tau dephosphorylating control modes. Stimulation of some Tau phosphatases is one of the effective and reasonably precise treatments for reversing Tau phosphorylation. We looked at Tau protein phosphatases and analyzed their physiological functions and regulation, their function in Tau phosphorylation, and their possible connection with AD in this article. We also reviewed the involvement of Tau phosphatase including protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) [

63].

Effect of PPI on GABAA Receptor

Findings suggest that NR2A receptor activation is critical in limiting Tau phosphorylation by the PKC/GSK3 pathway, and they support the concept that these receptors can function as a molecular device to prevent neuronal cell death and a variety of pathological conditions. After GABA

A receptor (R) activation, Tau phosphorylation at these residues was elicited by a pathway requiring cdk5, resulting in reduced PP2A interaction with Tau [

64]. A reduced PP2A will result in increased Tau phosphorylation that may stabilize microtubules, leading to neuron degeneration. Thus, hyper-activation of GABA

A R imbalances Tau’s phosphorylation state that may ultimately enhance the chances of dementia or AD via neuronal degeneration. According to previous positive interactive studies of PPI with some proteins, we made interaction of GABA

A R with various PPI and compared the interaction with a well-known GABA

A R activator.

The binding of diazepam (benzodiazepines) to a specific allosteric site on GABA

A R at the interface between α and γ subunits facilitates the inhibitory actions of GABA and can lead to a rapid increase in chloride/bicarbonate channels gating [

65] which results in cumulative enhancement of GABA-mediated transmission at inhibitory synapses in the brain. Comparative analysis of the binding ability of benzodiazepines and PPI to GABA

A R showed that it binds to GABA

A R in an almost similar fashion with high affinity, and lower binding energy compared to benzodiazepines (

Table 1,

Figure 1) and more hydrophobic interactions that increase the chances of easy binding. Therefore, it can be concluded that PPI may activate GABA

A R as benzodiazepines. Accordingly, PPI may lead to neuronal degeneration causing dementia or AD.

Figure 1.

PPI Interaction with GABAA Receptor.

Figure 1.

PPI Interaction with GABAA Receptor.

PPI as a Potential Inhibitor of AMP-Activated Protein Kinase (AMPK)

A study also indicated that AMPK activation reduces Tau phosphorylation that improves brain function by inhibiting GSK3β in the AD-like model. These findings proved that AMPK might be a novel target for AD treatment in the future. Thus, activation of AMPK can be useful for preventing AD occurrence and inhibition [

66] of AMPK will be unfavourable and may be associated with the development of AD. In the current study, we performed an interactive study between AMPK and various PPI and our bioinformatics results showed that PPI can inhibit AMPK that may accelerate Tau phosphorylation. This can be unfavourable for neuronal development due to imbalanced phosphorylation of Tau and activation of GSK3β which phosphorylates Tau. The PPI such as (R)-(+)-pantoprazole, esomeprazole, lansoprazole, (R)-omeprazole, (R)-tenatoprazole, (S)-tenatoprazole binds to AMPK with less energy compared to a known inhibitor (Dorsomorphin) of AMPK [

67]. Interaction bonds contain the number of amino acids with hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic bonding. The data has been shown the lowest level of energy in the binding site. Thus, PPI can be a potential inhibitor of AMPK and its chronic use may keep inhibiting AMPK for the long term and thus may allow AD or dementia development (

Table 2,

Figure 2).

Figure 2.

PPI interaction with AMPK.

Figure 2.

PPI interaction with AMPK.

PPI and Acetylcholine Esterase (AChE) and M1 mAChR

A study also suggests that AChE and the A-beta peptide may be involved in physiologically relevant interactions, associated with the pathogenesis of AD [

68]. An advanced in silico docking analysis followed by enzymological assessments was performed on PPIs against the core-cholinergic enzyme that is choline-acetyltransferase (ChAT), which synthesizes Ach. PPIs acted as inhibitors of ChAT, with high selectivity. Given that cholinergic dysfunction is a major driving force in dementia disorders [

110]. This study mechanistically explains how prolonged PPI use may increase the incidence of dementia. Thus, prolonged PPI use in the elderly and patients with dementia or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis should be restricted.

Role M1 Muscarinic Acetylcholine Receptor (M1 mAChR) in Dementia and Alzheimer’s Disease: PPI Binds M1 mAChR in an Inhibitory Fashion

Aβ is an important player in AD and is derived from β-amyloid precursor protein (APP) through sequential cleavages by β and γ-secretases: APP is cleaved by β-secretase to generate the large secreted derivative sAPPβ and the membrane-bound APP C-terminal fragment-β; the latter can be further cleaved by γ-secretase to generate Aβ and APP intracellular domain. Alternatively, APP can be cleaved by α-secretase within the Aβ domain, which precludes Aβ production and instead generates secreted sAPPα that is neuroprotective [

69,

70]. Interestingly, stimulation of M1 mAChR by agonists has been found to enhance sAPPα generation and reduce Aβ production [

71,

72] Stimulation of M1 mAChR is well-known to activate Protein Kinase C (PKC). PKC is found to promote the activity of α-secretase [

72] and the transferring of APP from the Golgi/ trans-Golgi network to the cell surface [

73]. M1 mAChR stimulation also activates ERK1/2, which modulates α-secretase activity and processing of APP [

74], though some contradictory findings are showing opposite results [

72]. In mouse AD models M1 mAChR promotes brain Aβ plaque pathology by increasing amyloidogenic APP processing in neurons and the brain (Davis et al., 2010). M1 mAChR also affects BACE1, the rate-limiting enzyme for Aβ generation [

75,

76]. APP/PS1/tau triple transgenic (3×Tg) AD mice were treated with AF267B, a selective M1 mAChR agonist. It reduces BACE1 endogenous level accompanied by a decreased Aβ level via an unclear mechanism, directly interacts with BACE1, and mediates its proteasomal degradation [

77,

78]. However, another study found that stimulation of M1 mAChR upregulates BACE1 levels in SK-SH-SY5Y cells via the PKC and MAPK signalling cascades [

79]. M1 mAChR was found to induce the Wnt signalling pathway to counteract Aβ-induced neurotoxicity [

80]. The involvement of M1 mAChR in AD is also manifested by its amelioration of tau pathology. Carbachol and AF102B (agonists) stimulate M1 mAChR in two, time- and dose-dependent manners and decrease tau phosphorylation in PC12 cells [

81]. AF267B (M1 mAChR agonist) lessens tau pathology by activating PKC and inhibiting GSK-3β in 3×Tg AD mice [

77,

82]. Activation of M1 mAChR protects against apoptotic factors (such as DNA damage, oxidative stress, caspase activation, and mitochondrial impairment) in human neuroblastoma (SH-SY5Y cells) [

83]. M1 mAChR cascade counteracts decreased cerebral blood flow which is a pathological characteristic in AD, ischemic brain injury, and cognitive dysfunction [

84,

85]. Uncoupling of M1 mAChR from G-protein in the hippocampal area, which is the most affected by Aβ was reported in the postmortem brains of AD patients [

86,

87,

88,

89,

90]. Aβ causes the uncoupling of M1 mAChR from G-protein, which inhibits the function of M1 mAChR [

91,

92].

Eventually, these studies depicted that a decreased M1 mAChR signal transduction will reduce levels of sAPPα, thereby increasing Aβ, thus triggering the onset of pathological features of AD. Though the mechanism of Aβ disrupting mAChR-G-protein coupling is unclear and is palliated implicating antioxidants and reducing the involvement of free radicals [

91]. Ultimately we found that inhibition of M1 mAChR results in dementia and AD, and since PPI has a wide range of interactions with various proteins we selected to analyze the interaction between PPI and M1 mAChR. Benztropine is a well-known inhibitor of acetylcholine (ACh) Muscarinic M1 and M3 receptors (mAChR). The implication of benztropine promotes differentiation of oligodendrocyte precursor cells and allows greater axonal remyelination in comparison to other drugs or molecules employed for treating multiple sclerosis [

93]. More hydrophobic interactions were noticed in the case of PPI in comparison to benztropine which declares better chances of binding. PPI showed lower binding energy and higher chances of binding; lansoprazole and tenatoprazole also showed hydrogen bond which requires less binding energy. Whereas benztropine showed no hydrogen bonding and thus PPI have higher chances of binding or a similar fashion of binding as benztropine.

PPI may also similarly inhibit M1 mAChR or more potentially as benztropine (

Table 3:

Figure 3).

Figure 3.

PPI Interaction with M1 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor (5CXV).

Figure 3.

PPI Interaction with M1 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor (5CXV).

PPIs and Vitamin B12 Deficiency

Gastric acidity is necessary for the absorption of vitamin B12, which is an essential water-soluble vitamin, obtained from different dietary sources such as fish, meat, dairy products, and fortified cereal [

94]. The risk of B12 deficiency increases with age [

95]. B12 is firmly bound to salivary R proteins and consequently requires acid-activated proteolytic digestion. PPI causes hypochlorhydria, resulting in vitamin B12 malabsorption [

96]. PPI treatment for 2 years or longer showed a statistically significant association with an increased risk of B12 deficiency [

97]. Whereas another study in contrast reported that a 3-year or longer PPI use had no change in B12 levels [

98].

In recent studies, dementia and cognitive impairment has been associated with vitamin B12 deficiency due to chronic use of PPI [

99]. Vitamin B12 is required for the production of nucleotides, phospholipids, and certain monoamine neurotransmitters [

100]. Usually, vitamin B12 is responsible to convert tetrahydrofolate into methylcobalamin which presents its methyl group to homocysteine which is acted upon by methionine synthase finally turns into methionine [

99]. Vitamin B12 deficiency results in hyperhomocysteinemia and is together considered as risk factors for cognitive impairment, dementia, and brain atrophy [

101]. PP2A plays a crucial role in brain-associated disorders as it is the key serine/threonine phosphatase and prevents tau hyperphosphorylation in the brain [

102]. Reduced methylation reduces PP2A function and leads to hyperphosphorylation and tau aggregation [

99]. Hyperhomocysteinemia also increases A

β production, while folate/vitamin B12 supplementation may attenuate these effects in animal models [

103,

104].

According to these studies elevated homocysteine levels are a strong risk factor for developing AD [

105]. Alternatively, B12 can interact with thiol groups, i.e., cobalamin can directly bind to tau protein via cysteine forming B12/tau protein complex that prevents fibrillation of tau protein [

99]. Vitamin B12 capping on cysteine also prevents tau aggregation. In summary, PPI causing vitamin B12 deficiency and hyperhomocysteinemia leads to PP2A inactivation and tau hyperphosphorylation that may result in cognitive impairment. Direct binding of vitamin B12 to tau protein resulting inhibited fibrillation and aggregation is also one of the major cause [

99].

Conclusion

There is currently no consensus on the role of PPIs and the associated risk of developing dementia and AD. Dementia and AD possess multifactorial nature and chronic PPI consumption may represent an additional risk factor of inducing neurodegeneration due to various interactions with the CNS. Moreover, PPI as well as possibly its interactions with various drugs, and may also act as a γ-aminobutyric acid GABA A agonist leading to neurological adverse events.

Indeed, people with dementia are prescribed two or more medications, including PPIs and benzodiazepines for a long time. FDA proves that adverse events could be associated with PPIs and benzodiazepine interactions. Long-term benzodiazepine employment itself has an underlying dementia risk, which can be increased by PPI use. Considering that PPI can strongly bind and may have an inhibitory action on the GABAA R. These may lead to neurological dysfunction, the physiopathology of dementia and AD, and other cognitive dysfunctions.

Though the mechanisms by which PPIs may induce brain impairment are currently unknown. They may also influence multimerization and stabilize tau aggregates or just increase their susceptibility to form aggregates. Additionally, PPIs influence ionic pumps that control membrane potential in neurons, thus altering electrochemical gradients.

In summary, our results indicate that chronic treatment with PPIs can effectively influence several biochemical targets including Aβ and tau protein formation, as well as M1 mAChR, AMPK, GABAA R, and endothelial function. The effect of PPIs on vitamin B12 levels, and their capability to induce H2O2 production plausibly has indirect effects on brain health, mainly in older adults with moderate and severe malnutrition or suffering from other chronic conditions.

Therefore, before starting a PPI treatment except in remarkably inevitable cases, it is necessary to also determine the cognitive status of patients, as well as the pharmacokinetic drug interactions that may occur due to the employment of multiple drugs and PPI. Finally, it is necessary to evaluate the risk and benefit ratio regarding the chronic use of PPI in patients at risk of dementia and AD while prescribing drugs.

Author Contributions

Ahmed and Nazmeen were the guarantor of the study; Ahmed, Nazmeen, Vekaria contributed to study conception, design, and data acquisition; Ahmed supervised the manuscript; Nazmeen and Vekaria created the figures and tables; Ahmed, Nazmeen, and Shahini provided critical reviews to the manuscript; all authors assisted in formatting, editing and revising the manuscript; all authors interpreted the data and wrote the first and final draft of the manuscript; all authors revised the article critically for important intellectual content and they gave final approval of the article to be published.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict-of-Interest Statement

The authors declare no conflict of interests for this article

Abbreviations

| Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) |

| Alzheimer’s disease (AD) |

| AutoDock Tool 1.5.6 [ATD] |

| M1 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor (M1 mAChR) |

| γ-amino butyric acid A receptor (GABA A R) |

| AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) |

| Acute interstitial nephritis (AIN) |

| Acute kidney injury (AKI) |

| Chronic kidney disease (CKD) |

| H2 receptor antagonists (H2RAs). |

| End-stage renal disease (ESRD) |

| ATP12A/ ATP1AL1 (alpha polypeptide) |

| Central nervous system (CNS) |

|

β-site APP-cleaving enzyme 1 (BACE1) |

| tethered C-terminal fragments β (CTFβ or C99) |

| extracellular Aβ and APP intracellular domain (AICD) |

|

γ-secretase modulators (iGSM), |

| Transglutaminase (tTG) |

| Neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) |

| Paired helical filaments (PHFs) |

| Protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) |

| Choline-acetyltransferase (ChAT) |

| β-amyloid precursor protein (APP) |

References

- JAYNES M., KUMAR A.B. The risks of long-term use of proton pump inhibitors: a critical review. Ther Adv Drug Saf., 2018, 10 : 2042098618809927. [CrossRef]

- HAENISCH B., VON HOLT K., WIESE B., PROKEIN J., LANGE C., ERNST A., et al. Risk of dementia in elderly patients with the use of proton pump inhibitors. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci., 2015, 265 : 419-28. [CrossRef]

- GOMM W., VON HOLT K., THOME F., BROICH K., MAIER W., FINK A., et al. Association of Proton Pump Inhibitors With Risk of Dementia: A Pharmacoepidemiological Claims Data Analysis. JAMA Neurol., 2016, 73 : 410-6.

- TORRES-BONDIA F., DAKTERZADA F., GALVAN L., BUTI M., BESANSON G., GILL E., et al. Proton pump inhibitors and the risk of Alzheimer's disease and non-Alzheimer's dementias. Sci Rep., 2020, 10 : 21046. [CrossRef]

- PARASURAMAN S., RAVEENDRAN R., VIJAYAKUMAR B., VELMURUGAN D., BALAMURUGAN S. Molecular docking and ex vivo pharmacological evaluation of constituents of the leaves of Cleistanthus collinus (Roxb.) (Euphorbiaceae). Indian J Pharmacol., 2012, 44 : 197-203. [CrossRef]

- THAL D.M., SUN B., FENG D., NAWARATNE V., LEACH K., FELDER C.C., et al. Crystal structures of the M1 and M4 muscarinic acetylcholine receptors. Nature., 2016, 531 : 335-40.

- KNIGHT D., HARRIS R., MCALISTER M.S., PHELAN J.P., GEDDES S., MOSS S.J., et al. The X-ray crystal structure and putative ligand-derived peptide binding properties of gamma-aminobutyric acid receptor type A receptor-associated protein. J Biol Chem., 2002, 277 : 5556-61. [CrossRef]

- DITE T.A., LANGENDORF C.G., HOQUE A., GALIC S., REBELLO R.J., OVENS A.J., et al. AMP-activated protein kinase selectively inhibited by the type II inhibitor SBI-0206965. J Biol Chem., 2018, 293 : 8874-8885. [CrossRef]

- FREEDBERG D.E., KIM L.S., YANG Y.X. The Risks and Benefits of Long-term Use of Proton Pump Inhibitors: Expert Review and Best Practice Advice From the American Gastroenterological Association. Gastroenterology., 2017, 152 : 706-715.

- LAZAURUS B., CHEN Y., WILSON F.P., SANG Y., CHANG A.R., CORESH J., et al. Proton Pump Inhibitor Use and the Risk of Chronic Kidney Disease. JAMA internal medicine., 2016, 176 : 238–246.

- XIE Y., BOWE B., LI T., XIAN H., BALASUBRAMANIAN S., AL-ALY Z. Proton Pump Inhibitors and Risk of Incident CKD and Progression to ESRD. J Am Soc Nephrol., 2016, 27 : 3153-3163.

- KHATRI M., NICKOLAS T., MOON Y.P., PAIK M.C., RUNDEK T., ELKIND M.S., et al. CKD associates with cognitive decline. J Am Soc Nephrol., 2009, 20 : 2427-32.

- DAVEY A., ELIAS M.F., ROBBINS M.A., SELIGER S.L., DORE G.A. Decline in renal functioning is associated with longitudinal decline in global cognitive functioning, abstract reasoning and verbal memory. Nephrol Dial Transplant., 2013, 28 : 1810-9. [CrossRef]

- KENDRICK J., HOLMEN J., SRINIVAS T., YOU Z., CHONCHOL M., JOVANOVICH A. Acute Kidney Injury Is Associated With an Increased Risk of Dementia. Kidney Int Rep., 2019, 4 : 1491-1493. [CrossRef]

- GRAMS M.E., RABB H. The distant organ effects of acute kidney injury. Kidney Int., 2012, 81 : 942-948.

- VERMA S.K., MOLITORIS B.A. Renal endothelial injury and microvascular dysfunction in acute kidney injury. Semin Nephrol., 2015, 35 : 96-107. [CrossRef]

- LIU M., LIANG Y., CHIGURUPATI S., LATHIA J.D., PLETNIKOV M., SUN Z., et al. Acute kidney injury leads to inflammation and functional changes in the brain. J Am Soc Nephrol., 2008, 19 : 1360-70. [CrossRef]

- KAO C.C., WU C.H., LAI C.F., HUANG T.M., CHEN H.H., WU V.C., et al. Long-term risk of dementia following acute kidney injury: A population-based study. Ci Ji Yi Xue Za Zhi., 2017, 29 : 201-207.

- XIE Y., BOWE B., LI T., XIAN H., YAN Y., AL-ALY Z. Long-term kidney outcomes among users of proton pump inhibitors without intervening acute kidney injury. Kidney Int., 2017, 91 : 1482-1494.

- MCKHANN G.M., KNOPMAN D.S., CHERTKOW H., HYMAN B.T., JACK C.R J.R., KAWAS C.H., et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer's disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement., 2011, 7 : 263-9.

- RASCOVSKY K., HODGES J.R., KNOPMAN D., MENDEZ M.F., KRAMER J.H., NEUHAUS J., et al. Sensitivity of revised diagnostic criteria for the behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia. Brain., 2011, 134 : 2456-77. [CrossRef]

- GORNO-TEMPINI M.L., HILLIS A.E., WEINTRAUB S., KERTESZ A., MENDEZ M., CAPPA S.F., et al. Classification of primary progressive aphasia and its variants. Neurology., 2011, 76 : 1006-14. [CrossRef]

- MCKEITH I.G., BOEVE B.F., DICKSON D.W., HALLIDAY G., TAYLOR J.P., WEINTRAUB D., et al. Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies: Fourth consensus report of the DLB Consortium. Neurology., 2017, 89 : 88-100.

- VAN DRIEL I.R., CALLAGHAN J.M. Proton and potassium transport by H+/K(+)-ATPases. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol., 1995, 22 : 952-60.

- SINGH V., MANI I., CHAUDHARY D.K. ATP4A gene regulatory network for fine-tuning of proton pump and ion channels. Syst Synth Biol., 2013, 7 : 23-32. [CrossRef]

- MODYANOV N.N., PETRUKHIN K.E., SVERDLOV V.E., GRISHIN A.V., ORLOVA M.Y., KOSTINA M.B., et al. The family of human Na,K-ATPase genes. ATP1AL1 gene is transcriptionally competent and probably encodes the related ion transport ATPase. FEBS Lett., 1991, 278 : 91-4.

- WANG D., HEISINGER P.R. The vesicular ATPase: a missing link between acidification and exocytosis. J Cell Biol., 2013, 203 : 171-3.

- TABARES L., BETZ B. Multiple functions of the vesicular proton pump in nerve terminals. Neuron., 2010, 68 : 1020-2.

- SHIN J.M., KIM N. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of the proton pump inhibitors. J Neurogastroenterol Motil., 2013, 19 : 25-35.

- SHIN J.M., MUNSON K., VAGIN O., SACHS G. The gastric HK-ATPase: structure, function, and inhibition. Pflugers Arch., 2009, 457 : 609-22.

- CHENG F.C., HO Y.F., HUNG L.C., CHEN C.F., TSAI T.H. Determination and pharmacokinetic profile of omeprazole in rat blood, brain and bile by microdialysis and high-performance liquid chromatography. J Chromatogr A., 2002, 949 : 35-42.

- ROJO L.E., ALZATE-MORALES J., SAAVEDRA I.N., DAVIES P., MACCIONI R.B. Selective interaction of lansoprazole and astemizole with tau polymers: potential new clinical use in diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease. J Alzheimers Dis., 2010, 19 : 573-89. [CrossRef]

- LIANG J.F., CHEN Y.T., FUH J.L., LI S.Y., CHEN T.J., TANG C.H., et al. Proton pump inhibitor-related headaches: a nationwide population-based case-crossover study in Taiwan. Cephalalgia., 2015, 35 : 203-10.

- MARTIN R.M., DUNN N.R., FREEMANTLE S., SHAKIR S. The rates of common adverse events reported during treatment with proton pump inhibitors used in general practice in England: cohort studies. Br J Clin Pharmacol., 2000, 50 : 366-72. [CrossRef]

- CHIMIRRI S., AIELLO R., MAZZITELLO C., MUMOLI L., PALLERIA C., ALTOMONTE M., et al. Vertigo/dizziness as a Drugs' adverse reaction. J Pharmacol Pharmacother., 2013, 4 : S104-9. [CrossRef]

- HANNEKEN A.M., BABAI N., THORESON W.B. Oral proton pump inhibitors disrupt horizontal cell-cone feedback and enhance visual hallucinations in macular degeneration patients. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci., 2013, 54 : 1485-9. [CrossRef]

- HECKMANN J.G., BIRKLEIN F., NEUNDORFER B. Omeprazole-induced delirium. J Neurol., 2000, 247 : 56-7. [CrossRef]

- DE LA COBA ORTIZ C., ARGUELLAS ARIAS F., MARTIN DE ARGILA DE PRADOS C., JUDEZ GUTIERREZ J., LINARES RODRIGUES A., ORTEGA ALONSO A., et al. Proton-pump inhibitors adverse effects: a review of the evidence and position statement by the Sociedad Española de Patología Digestiva. Rev Esp Enferm Dig., 2016, 108 : 207-24.

- BADIOLA N., ALCALDE V., PUJOL A., MUNTER L.M., MULTHAUP G., LLEO A., et al. The proton-pump inhibitor lansoprazole enhances amyloid beta production. PLoS One., 2013, 8 : e58837. [CrossRef]

- CHEN G.F., XY T.H., YAN Y., ZHOU Y.R., JIANG Y., MELCHER K., et al. Amyloid beta: structure, biology and structure-based therapeutic development. Acta Pharmacol Sin., 2017, 38 : 1205-1235.

- DAROCHA-SOUTO B., SCOTTON T.C., COMA M., SERANNO-POZO A., HASHIMOTO T., SERENO L., et al. Brain oligomeric β-amyloid but not total amyloid plaque burden correlates with neuronal loss and astrocyte inflammatory response in amyloid precursor protein/tau transgenic mice. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol., 2011, 70 : 360-76. [CrossRef]

- STEVEN G.Y., RUDOLPH E.T. Presenilins and Alzehimer’s Disease : Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 1998.

- FALLAHZADEH M.K., BORHANI HAGHIGHI A., NAMAZI M.R. Proton pump inhibitors: predisposers to Alzheimer disease? J Clin Pharm Ther., 2010, 35 : 125-6.

- NAMAZI M.R., JOWKAR F. A succinct review of the general and immunological pharmacologic effects of proton pump inhibitors. J Clin Pharm Ther., 2008, 33 : 215-7. [CrossRef]

- BENZINGER T.L., GREGORY D.M., BURKOTH T.S., MILLER-AUER H., LYNN D.G., BOTTO R.E., et al. Propagating structure of Alzheimer's beta-amyloid(10-35) is parallel beta-sheet with residues in exact register. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A., 1998, 95 : 13407-12.

- WILHELMUS M.M., DE JAGER M., SMIT A.B.S., VAN DER LOO R.J., DRUKARCH B. Catalytically active tissue transglutaminase colocalises with Aβ pathology in Alzheimer's disease mouse models. Sci Rep., 2016, 6 : 20569. [CrossRef]

- ATWOOD C.S., MOIR R.D., HUANG X., SCARPA R.C., BACARRA N.M., ROMANO D.M., et al. Dramatic aggregation of Alzheimer abeta by Cu(II) is induced by conditions representing physiological acidosis. J Biol Chem., 1998, 273 : 12817-26. [CrossRef]

- SOUZA J.M., GIASSON B.I., CHEN Q., LEE V.M., ISCHIROPOULOS H. Dityrosine cross-linking promotes formation of stable alpha -synuclein polymers. Implication of nitrative and oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative synucleinopathies. J Biol Chem., 2000, 275 : 18344-9.

- YOBURN J.C., TIAN W., BROWER J.O., NOWICK J.S., GLABE C.G., VAN VRANKEN D.L. Dityrosine cross-linked Abeta peptides: fibrillar beta-structure in Abeta(1-40) is conducive to formation of dityrosine cross-links but a dityrosine cross-link in Abeta(8-14) does not induce beta-structure. Chem Res Toxicol., 2003, 16 : 531-5.

- ATWOOD C.S., PERRY G., ZENG H., KATO Y., JONES W.B., LING K.Q., et al. Copper mediates dityrosine cross-linking of Alzheimer's amyloid-beta. Biochemistry., 2004, 43 : 560-8.

- PATEL A., ZHANG S., SHRESTHA A.K., MATURU P., MOORTHY B., SHIVANNA B. Omeprazole induces heme oxygenase-1 in fetal human pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells via hydrogen peroxide-independent Nrf2 signaling pathway. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol., 2016, 311 : 26-33. [CrossRef]

- AL-HILALY Y.K., WILLIAMS T.L., STEWART-PARKER M., et al. A central role for dityrosine crosslinking of Amyloid-β in Alzheimer’s disease. acta neuropathol commun., 2013, 1 : 83.

- DAWBARN D., ALLEN S.J. Neurobiology of Alzheimer’s Disease. BIOS Scientific Publishers, 1995.

- FARIAS G.A., VIAL C., MACCIONI R.B. Specific macromolecular interactions between tau and the microtubule system. Mol Cell Biochem., 1992, 112 : 81-8. [CrossRef]

- KOSIK K.S., JOACHIM C.L., SELKOE D.J. Microtubule-associated protein tau (tau) is a major antigenic component of paired helical filaments in Alzheimer disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A., 1986, 83 : 4044-8. [CrossRef]

- MACCIONI R.B., CAMBIAZO V. Role of microtubule-associated proteins in the control of microtubule assembly. Physiol Rev., 1995, 75 : 835-64. [CrossRef]

- BILLINGSLEY M.L., KINCAID R.L. Regulated phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of tau protein: effects on microtubule interaction, intracellular trafficking and neurodegeneration. Biochem J., 1997, 323 : 577-91. [CrossRef]

- ROJO L.E., FERNANDEZ J.A., MACCIONI A.A., JIMENEZ J.M., MACCIONI R.B. Neuroinflammation: implications for the pathogenesis and molecular diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease. Arch Med Res., 2008, 39 : 1-16. [CrossRef]

- OKAMURA N., SUEMOTO T., FURUMOTO S., SUZUKI M., SHIMADZU H., AKATSU H., et al. Quinoline and benzimidazole derivatives: candidate probes for in vivo imaging of tau pathology in Alzheimer's disease. J Neurosci., 2005, 25 : 10857-62. [CrossRef]

- FAWAZ M.V., BROOKS A.F., RODNICK M.E., CARPENTER G.M., SHAO X., DESMOND T.J., et al. High affinity radiopharmaceuticals based upon lansoprazole for PET imaging of aggregated tau in Alzheimer's disease and progressive supranuclear palsy: synthesis, preclinical evaluation, and lead selection. ACS Chem Neurosci., 2014, 5 : 718-30.

- CARTEE N.M.P., WANG M.M. Binding of omeprazole to protein targets identified by monoclonal antibodies. PLoS One., 2020, 15 : e0239464.

- DOLAN P.J., JOHNSON G.V. The role of tau kinases in Alzheimer's disease. Curr Opin Drug Discov Devel., 2010, 13 : 595-603.

- MARTIN L., LATYPOVA X., WILSON C.M., MAGNAUDEIX A., PERRIN M.L., TERRO F. Tau protein phosphatases in Alzheimer's disease: the leading role of PP2A. Ageing Res Rev., 2013, 12 : 39-49. [CrossRef]

- DE MONTIGNY A., ELHIRI I., ALLYSON J., CYR M., MASSICOTTE G. NMDA reduces Tau phosphorylation in rat hippocampal slices by targeting NR2A receptors, GSK3β, and PKC activities. Neural Plast., 2013, 2013 : 261593. [CrossRef]

- NICHOLSON M.W., SWEENEY A., PEKLE E., ALAM S., ALI A.B., DUCHEN M., JOVANOVIC J.N. Diazepam-induced loss of inhibitory synapses mediated by PLCδ/ Ca2+/calcineurin signalling downstream of GABAA receptors. Mol Psychiatry., 2018, 23 : 1851-1867. [CrossRef]

- WANG L., LI N., SHI F.X., XU W.Q., CAO Y., LEI Y., et al. Upregulation of AMPK Ameliorates Alzheimer's Disease-Like Tau Pathology and Memory Impairment. Mol Neurobiol., 2020, 57 : 3349-3361.

- LIU X., CHHIPA R.R., NAKANO I., DASGUPTA B. The AMPK inhibitor compound C is a potent AMPK-independent antiglioma agent. Mol Cancer Ther., 2014, 13 : 596-605. [CrossRef]

- OPAZO C., INESTROSA N.C. Crosslinking of amyloid-beta peptide to brain acetylcholinesterase. Mol Chem Neuropathol., 1998, 33 : 39-49. [CrossRef]

- ZHENG H., KOO E.H. Biology and pathophysiology of the amyloid precursor protein. Mol Neurodegener., 2011, 6 : 27.

- ZHANG Y.W., THOMPSON R., ZHANG H., XU H. APP processing in Alzheimer's disease. Mol Brain., 2011, 4 : 3.

- HARING R., GURWITZ D., BARG J., PINKAS-KRAMARSKI R., HELDMAN E., PITTEL Z., et al. Amyloid precursor protein secretion via muscarinic receptors: reduced desensitization using the M1-selective agonist AF102B. Biochem Biophys Res Commun., 1994, 203 : 652-8. [CrossRef]

- WOLF B.A., WERTKIN A.M., JOLLY Y.C., YASUDA R.P., WOLFE B.B., KONRAD R.J., et al. Muscarinic regulation of Alzheimer's disease amyloid precursor protein secretion and amyloid beta-protein production in human neuronal NT2N cells. J Biol Chem., 1995, 270 : 4916-22. [CrossRef]

- XU H., GREENGARD P., GANDY S. Regulated formation of Golgi secretory vesicles containing Alzheimer beta-amyloid precursor protein. J Biol Chem., 1995, 270 : 23243-5. [CrossRef]

- BIGL V., ROSSNER S. Amyloid precursor protein processing in vivo--insights from a chemically-induced constitutive overactivation of protein kinase C in Guinea pig brain. Curr Med Chem., 2003, 10 : 871-82.

- CHAMI L., CHECLER F. BACE1 is at the crossroad of a toxic vicious cycle involving cellular stress and β-amyloid production in Alzheimer's disease. Mol Neurodegener., 2012, 7 : 52. [CrossRef]

- COLE S.L., VASSAR R. The Alzheimer's disease beta-secretase enzyme, BACE1. Mol Neurodegener., 2007, 2 : 22.

- CACCAMO A., ODDO S., BILLINGS L.M., GREEN K.N., MARTINEZ-CORIA H., FISHER A., et al. M1 receptors play a central role in modulating AD-like pathology in transgenic mice. Neuron., 2006, 49 : 671-82. [CrossRef]

- JIANG S., WANG Y., MA Q., ZHOU A., ZHANG X., ZHANG Y.W. M1 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor interacts with BACE1 and regulates its proteosomal degradation. Neuroscience letters., 2012, 515 : 125–130.

- ZUCHNER T., PEREZ-POLO J.R., SCHLIEBS R. Beta-secretase BACE1 is differentially controlled through muscarinic acetylcholine receptor signaling. J Neurosci Res., 2004, 77 : 250-7. [CrossRef]

- FARIAS G.G., GODOY J.A., HERNANDEZ F., AVILA J., FISHER A., INESTROSA N.C. M1 muscarinic receptor activation protects neurons from beta-amyloid toxicity. A role for Wnt signaling pathway. Neurobiol Dis., 2004, 17 : 337-48.

- SADOT E., GURWITZ D., BARG J., BEHAR L., GINZBURG I., FISHER A. Activation of m1 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor regulates tau phosphorylation in transfected PC12 cells. J Neurochem., 1996, 66 : 877-80. [CrossRef]

- FORLENZA O.V., SPINK J.M., DAYANANDAN R., ANDERTON B.H., OLESEN O.F., LOVESTONE S. Muscarinic agonists reduce tau phosphorylation in non-neuronal cells via GSK-3beta inhibition and in neurons. J Neural Transm (Vienna)., 2000, 107 : 1201-12. [CrossRef]

- DE SARNO P., SHESTOPAL S.A., KING T.D., ZMIJEWSKA A., SONG L., JOPES R.S. Muscarinic receptor activation protects cells from apoptotic effects of DNA damage, oxidative stress, and mitochondrial inhibition. J Biol Chem., 2003, 278 : 11086-93.

- HANYU H., SHIMIZU T., TANAKA Y., TAKASAKI M., KOIZUMI K., ABE K. Regional cerebral blood flow patterns and response to donepezil treatment in patients with Alzheimer's disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord., 2003, 15 : 177-82. [CrossRef]

- BATEMAN G.A., LEVI C.R., SCHOFIELD P., WANG Y., LOVETT E.C. Quantitative measurement of cerebral haemodynamics in early vascular dementia and Alzheimer's disease. J Clin Neurosci., 2006, 13 : 563-8. [CrossRef]

- FERRARI-DILEO G., MASH D.C., FLYNN D.D. Attenuation of muscarinic receptor-G-protein interaction in Alzheimer disease. Mol Chem Neuropathol., 1995, 24 : 69-91. [CrossRef]

- TSANG S.W., LAI M.K., KIRVELL S., FRANCIS P.T., ESIRI M.M., HOPE T., et al. Impaired coupling of muscarinic M1 receptors to G-proteins in the neocortex is associated with severity of dementia in Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Aging., 2006, 27 : 1216-23. [CrossRef]

- POTTER P.E., RAUSCHKOLB P.K., PANDYA Y., SUE L.I., SABBAGH M.N., WALKER D.G., et al. Pre- and post-synaptic cortical cholinergic deficits are proportional to amyloid plaque presence and density at preclinical stages of Alzheimer's disease. Acta Neuropathol., 2011, 122 : 49-60. [CrossRef]

- LADNER C.J., LEE J.M. Reduced high-affinity agonist binding at the M(1) muscarinic receptor in Alzheimer's disease brain: differential sensitivity to agonists and divalent cations. Exp Neurol., 1999, 158 : 451-8.

- SHIOZAKI K., ISEKI E. Decrease in GTP-sensitive high affinity agonist binding of muscarinic acetylcholine receptors in autopsied brains of dementia with Lewy bodies and Alzheimer's disease. J Neurol Sci., 2004, 223 : 145-8. [CrossRef]

- KELLY J.F., FURUKAWA K., BARGER S.W., RENGEN M.R., MARK R.J., BLANC E.M., et al. Amyloid beta-peptide disrupts carbachol-induced muscarinic cholinergic signal transduction in cortical neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A., 1996, 93 : 6753-8. [CrossRef]

- JANICKOVA H., RUDAJEV V., ZIMCIK P., JAKUBIK J., TANILA H., EL-FAKAHANY E.E., et al. Uncoupling of M1 muscarinic receptor/G-protein interaction by amyloid β(1-42). Neuropharmacology., 2013, 67 : 272-83.

- DESHMUKH V.A., TARDIF V., LYSSIOTIS C.A., GREEN C.C., KERMAN B., KIM H.J., et al. A regenerative approach to the treatment of multiple sclerosis. Nature., 2013, 502 : 327-332. [CrossRef]

- OH R., BROWN D.L. Vitamin B12 deficiency. Am Fam Physician., 2003, 67 : 979-86.

- HUNT A., HARRINGTON D., ROBINSON S. Vitamin B12 deficiency. BMJ., 2014, 349 : g5226.

- SARVARINO V., DULBECCO P., SARVARINO E. Are proton pump inhibitors really so dangerous? Dig Liver Dis., 2016, 48 : 851-9.

- LAM J.R., SCHNEIDER J.L., ZHAO W., CORLEY D.A. Proton pump inhibitor and histamine 2 receptor antagonist use and vitamin B12 deficiency. JAMA., 2013, 310 : 2435-42.

- LOMBARDO L., FOTI M., RUGGIA O., CHIECCHIO A. Increased incidence of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth during proton pump inhibitor therapy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol., 2010, 8 : 504-8. [CrossRef]

- RAFIEE S., ASADOLLAHI K., RIAZI G., AHMADIAN S., SABOURY A.A. Vitamin B12 Inhibits Tau Fibrillization via Binding to Cysteine Residues of Tau. ACS Chem Neurosci., 2017, 8 : 2676-2682. [CrossRef]

- PENNINX B.W., GURALNIK J.M., FERRUCCI L., FRIED L.P., ALLEN R.H., STABLER S.P. Vitamin B(12) deficiency and depression in physically disabled older women: epidemiologic evidence from the Women's Health and Aging Study. Am J Psychiatry., 2000, 157 : 715-21. [CrossRef]

- MA F., WU T., ZHAO J., JI L., SONG A., ZHANG A., et al. Plasma Homocysteine and Serum Folate and Vitamin B12 Levels in Mild Cognitive Impairment and Alzheimer's Disease: A Case-Control Study. Nutrients., 2017, 9 : 725.

- BOTTIGLIERI T., ARNING E., WASEK B., NUNBHAKDI-CRIAG V., SONTAG J.M., SONTAG E. Acute administration of L-DOPA induces changes in methylation metabolites, reduced protein phosphatase 2A methylation, and hyperphosphorylation of Tau protein in mouse brain. J Neurosci., 2012, 32 : 9173-81. [CrossRef]

- WEI W., LIU Y.H., ZHANG C.E., WANG Q., WEI Z., MOUSSEAU D.D., et al. Folate/vitamin-B12 prevents chronic hyperhomocysteinemia-induced tau hyperphosphorylation and memory deficits in aged rats. Journal of Alzheimer's disease : JAD., 2011, 27 : 639–650.

- ZHANG C.E., WEI W., LIU Y.H., PENG J.H., TIAN Q., LIU G.P., et al. Hyperhomocysteinemia increases beta-amyloid by enhancing expression of gamma-secretase and phosphorylation of amyloid precursor protein in rat brain. Am J Pathol., 2009, 174 : 1481-91.

- RAVAGLIA G., FORTI P., MAIOLI F., MARTELLI M., SERVADEI L., BRUNETTI N., et al. Homocysteine and folate as risk factors for dementia and Alzheimer disease. Am J Clin Nutr., 2005, 82 : 636-43.

- LI M., LUO Z., YU S., TANG Z. Proton pump inhibitor use and risk of dementia: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore)., 2019, 98 : e14422.

- SONG Y.Q., LI Y., ZHANG S.L., GAO J., FENG S.Y. Proton pump inhibitor use does not increase dementia and Alzheimer's disease risk: An updated meta-analysis of published studies involving 642305 patients. PLoS One., 2019, 14 : e0219213.

- KHAN M.A., YUAN Y., IQBAL U., KAMAL S., KHAN M., KHAN Z., et al. No Association Linking Short-Term Proton Pump Inhibitor Use to Dementia: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Observational Studies. Am J Gastroenterol., 2020, 115 : 671-678.

- CROWSON M.S., SHULL, G.E. (1992) Isolation and characterization of a cDNA encoding the putative distal colon Ht, K+-ATPase: Similarity of deduced amino acid sequence to gastric H', K+-ATPase and Na+, K+-ATPase and mRNA expression in distal colon, kidney, uterus. J Biol Chem., 1992, 267 : 13740-8.

- KUMAR R., KUMAR A., NORDBERG A., LANGSTROM B., DARREH-SHORI T. Proton pump inhibitors act with unprecedented potencies as inhibitors of the acetylcholine biosynthesizing enzyme-A plausible missing link for their association with incidence of dementia. Alzheimers Dement., 2020, 16 : 1031-1042. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).