Introduction

Pregnancy induces a wide range of physiological changes, many of which affect the ocular system. Hormonal, metabolic, and vascular alterations that occur during gestation can significantly impact ocular health, potentially increasing risks for individuals with preexisting eye conditions such as glaucoma. Key gestational hormones – including estrogen, progesterone, human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), and relaxin – play critical roles in modulating ocular physiology, influencing intraocular fluid dynamics, corneal structure, tear film stability, and intraocular pressure (IOP) [

1,

2,

3].

One of the most consistent and well-documented ocular changes during pregnancy is a reduction in intraocular pressure (IOP), typically ranging from 2 to 4 mmHg, particularly during the second and third trimesters. This decrease is primarily attributed to enhanced uveoscleral outflow, reduced episcleral venous pressure, and decreased aqueous humor production [

4]. Additionally, systemic vasodilation – largely mediated by estrogen-induced nitric oxide activity – further facilitates aqueous humor drainage and contributes to the lowering of IOP [

5].

Corneal physiology also undergoes significant modifications during pregnancy. In-creased fluid retention and tissue remodeling lead to corneal thickening, which can in-fluence the accuracy of tonometry measurements – an important consideration in glaucoma management. Studies such as that by Ibraheem et al. (2015) underscore the importance of accounting for these changes when monitoring pregnant patients with glaucoma [

6]. Increased corneal hydration may also contribute to temporary refractive shifts, reduced contact lens tolerance, and symptoms such as ocular dryness and dis-comfort [

6,

7]. Pregnancy-related changes also affect the conjunctiva and tear film. Many pregnant individuals experience dry eye syndrome due to altered tear production and tear film instability. This condition may be exacerbated in glaucoma patients using topical medications containing preservatives, such as benzalkonium chloride, potentially necessitating adjustments to the therapeutic regimen to manage ocular surface disease [

7,

8].

Deeper ocular structures are also affected during pregnancy. Studies using enhanced depth imaging optical coherence tomography (EDI-OCT) have demonstrated choroidal thickening, likely due to increased choroidal perfusion [

9]. While the clinical impact of these changes on glaucoma progression remains uncertain, they highlight the importance of thorough ophthalmic monitoring throughout pregnancy. Furthermore, visual field testing – a critical component of glaucoma assessment – may yield less consistent results during pregnancy due to factors such as fatigue, mood fluctuations, and decreased attentiveness [

10].

Pregnancy-induced immune modulation, marked by a shift toward immunotolerance to support fetal development, may also affect ocular immune responses. Emerging evidence shows that neuroinflammatory processes and microglial activation contribute to the pathogenesis of glaucomatous optic neuropathy [

11]. However, the impact of gestational immune changes on the progression of glaucoma remains poorly understood. The natural reduction in IOP may allow for the temporary discontinuation or reduction of glaucoma medications in some patients [

12]. However, pregnancy-related changes in ocular physiology complicate disease monitoring, necessitating regular follow-up and close collaboration between ophthalmologists and obstetricians [

13].

The emotional well-being of the patient is also a critical consideration in managing glaucoma during pregnancy. Pregnant women with glaucoma may experience anxiety regarding the safety of medications and the potential need for surgical intervention [

14]. Open, empathetic communication is essential for alleviating concerns, building trust, and ensuring better adherence to treatment. With carefully tailored and consistent follow-up, most pregnant women with glaucoma can maintain stable visual function throughout the course of pregnancy [

15].

In summary, pregnancy induces complex systemic and ocular physiological changes. A thorough understanding of these pathophysiological processes and their clinical implications is essential for optimizing visual health outcomes for both mother and child [

16]. The purpose of this review is to provide an updated overview of intraocular pressure changes during pregnancy and available treatment modalities, with a particular focus on the risks associated with medication use during gestation.

Materials and Methods

A narrative synthesis of the literature, integrating findings obtained through systematic searches of electronic databases, manual searches, and established scholarly sources.

2.1. Database Search Strategy

A comprehensive literature review was conducted using several major academic databases, including PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, Embase, and Google Scholar, to evaluate the relationship between glaucoma and pregnancy [

4]. The search was limited to English-language studies published between January 2000 and March 2025. Specific keywords were used, such as “glaucoma AND pregnancy,” “intraocular pressure AND gestation,” “hormones AND ocular pressure,” “ophthalmic medication safety in preg-nancy,” “glaucoma surgery AND pregnant patients,” “SLT AND gestational glaucoma,” and “MIGS AND pregnancy.” Boolean operators (AND, OR, NOT) were applied to expand and refine the search results [

9].

To ensure comprehensive coverage, manual searches of the reference lists in key review articles were also performed [

2]. The selected articles were managed using citation management software, including EndNote and Mendeley, to remove duplicates and facilitate the organization of studies based on relevance and methodological quality. Additionally, Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) were incorporated into PubMed searches to enhance sensitivity and ensure a more thorough exploration of the relevant scientific literature [

17].

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

Inclusion criteria. Studies were considered eligible for inclusion if the following criteria were met: (1) the study population included pregnant women diagnosed with glaucoma or ocular hypertension; (2) the study addressed any aspect of glaucoma management during pregnancy, including pharmacological, laser-based, or surgical interventions; and (3) at least one ophthalmologic outcome was reported, such as intraocular pressure control, optic nerve evaluation, or visual field assessment [

15].

Exclusion criteria. We excluded studies published in languages other than English, animal or in vitro research, conference abstracts lacking full data, editorials, opinion pieces, and narrative reviews. Additionally, we did not include studies focusing solely on other ocular complications of pregnancy, such as diabetic retinopathy or hypertensive retinopathy, unless they provided comparative or mechanistic insights directly relevant to glaucoma [

18]. See

Table 1

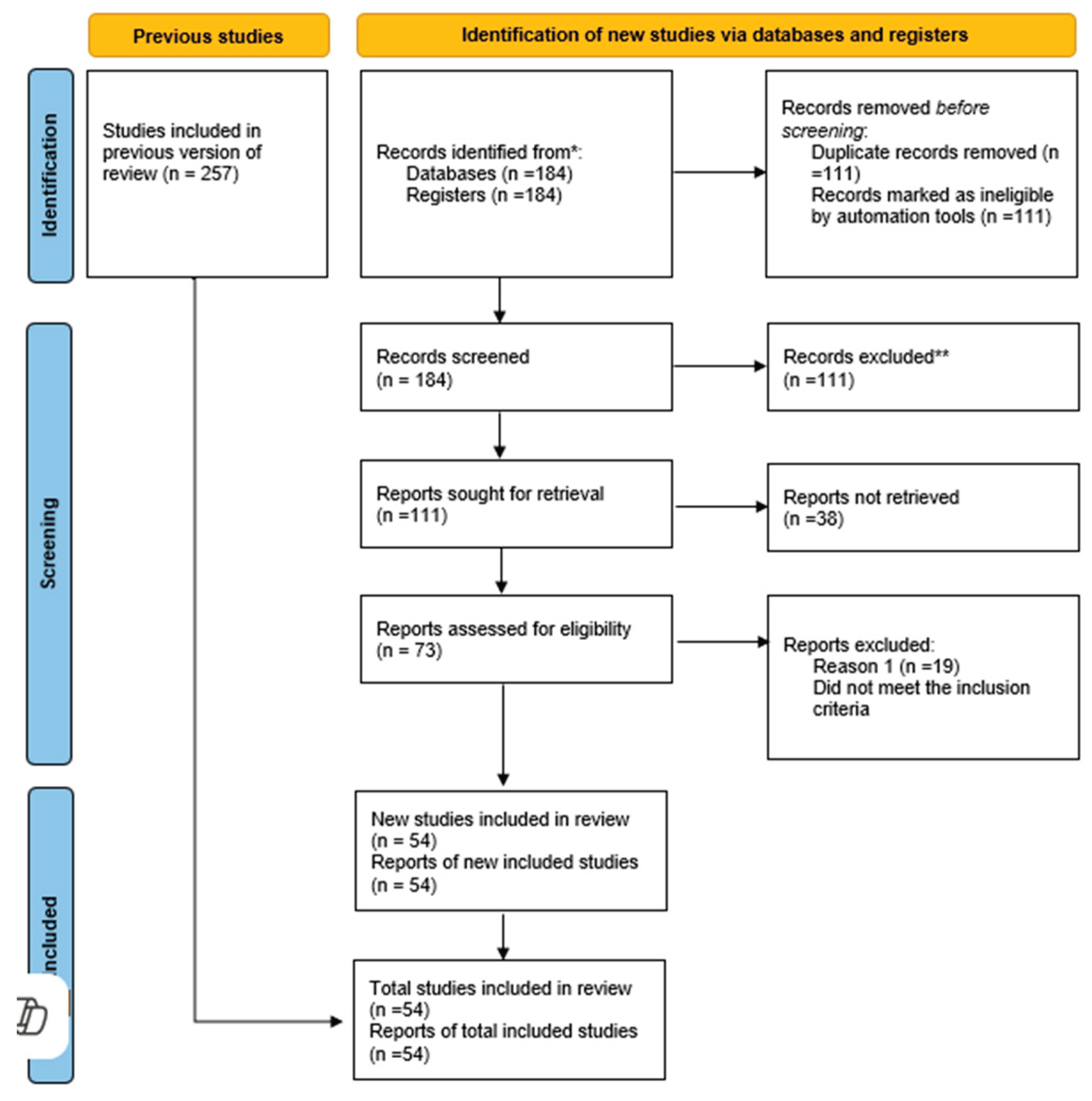

The selection of studies was conducted independently by two reviewers with training in ophthalmology. An initial screening of article titles and abstracts was followed by full-text assessments of potentially eligible studies. The PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) framework was used as a guide to ensure methodological rigor and transparency [

7].

2.3. Risk of Bias Assessment

Due to the heterogeneity and small size of most included studies, no formal risk-of bias tool (e.g., ROBINS-I or Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool) was applied. Most studies exhibited a moderate risk of bias, primarily due to small sample sizes, lack of control groups, and potential confounding variables that were not adequately addressed. No automation tools were used in the risk of bias assessment process, and evaluations were conducted manually.

3. Results

From an initial pool of 257 records identified through database searches, 184 studies remained after duplicate removal. Following the title and abstract screening, 73 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility. Ultimately, 54 studies met all inclusion criteria and were included in the final review [

8]. According to studies, although glaucoma during pregnancy is relatively rare, its prevalence among pregnant women is 0.16% in the 15-34 age group and between 0.3% and 0.7% in the 35-44 age group [

12]. Data extraction was performed using a standardized template, and a qualitative synthesis was conducted to identify key themes related to treatment strategies, medication safety, and clinical outcomes. A PRISMA flow diagram was generated to illustrate the study selection process and enhance transparency in reporting [

9] (

Figure 1).

Pregnancy-related pathological changes may present as new ocular developments, changes in existing ocular pathology, and ocular complications of systemic diseases.

3.1. Changes in Intraocular Pressure During Pregnancy

Intraocular pressure (IOP) is essential in the diagnosis and management of glaucoma, and it is well established that pregnancy significantly influences IOP levels. A substantial body of evidence indicates a physiological reduction in IOP during pregnancy, particularly in the second and third trimesters [

2,

13]. The mechanisms underlying this phenomenon are complex and involve hormonal, vascular, and anatomical changes that alter aqueous humor dynamics.

Among the principal factors contributing to reduced IOP during pregnancy are elevated levels of endogenous estrogen and progesterone [

5]. These hormones are believed to affect the trabecular meshwork and uveoscleral outflow pathways. Progesterone, for instance, may reduce aqueous humor production by inhibiting carbonic anhydrase, while estro-gen’s vasodilatory effects are thought to lower episcleral venous pressure, thereby de-creasing IOP. Additionally, pregnancy-specific hormone relaxin may promote ocular tissue relaxation and facilitate outflow through non-traditional pathways [

9].

Data from Ibraheem et al. (2015) and Wang et al. (2017) support these mechanisms [

4,

6]. Their findings indicate that IOP typically decreases by approximately 2–4 mmHg from pre-pregnancy levels, with the most pronounced reductions observed during the second and third trimesters. Postpartum, IOP generally returns to baseline levels. These reductions are more consistently observed in women with normal baseline IOP, whereas those with ocular hypertension or glaucoma may exhibit a less marked response [

8].

However, the degree of IOP reduction during pregnancy is not uniform and appears to be influenced by additional physiological and demographic factors. Variables such as age, parity, systemic blood pressure, and CCT can affect the magnitude of IOP change. Multiparous women, for example, often show more substantial IOP reductions compared to primigravida’s, possibly reflecting cumulative hormonal effects or adaptive vascular changes [

16]. Although diurnal IOP fluctuations persist during pregnancy, their amplitude may be diminished, complicating efforts to accurately monitor disease progression [

10].

Changes in corneal biomechanics during pregnancy, particularly increased CCT due to estrogen-mediated fluid retention, can further affect the interpretation of tonometry measurements. Corneal thickening may result in falsely elevated IOP readings when using Goldmann applanation tonometry. Clinicians are therefore advised to interpret these measurements with caution and consider alternative methods, such as dynamic contour tonometry or rebound tonometry, which are less influenced by corneal properties [

18].

While a decrease in IOP is typical, a subset of patients may experience paradoxical elevations during pregnancy. This is especially relevant for individuals with narrow-angle glaucoma or those who have undergone prior surgical interventions affecting aqueous outflow. Hormonal and anatomical changes in these patients may promote angle narrowing or exacerbate existing outflow resistance, necessitating close monitoring and, in some cases, therapeutic adjustments [

15].

Moreover, systemic complications of pregnancy, such as preeclampsia and gestational hypertension, can also impact ocular health. Preeclampsia, characterized by widespread vascular dysfunction, may contribute to choroidal thickening and, in certain cases, elevated IOP. Although the precise mechanisms are still under investigation, clinicians should remain vigilant for atypical ocular presentations in these high-risk populations [

19].

From a clinical standpoint, the pregnancy-associated reduction in IOP presents an opportunity to temporarily reduce or discontinue glaucoma medications, thereby mini-mizing fetal exposure to potentially teratogenic agents. However, such adjustments must be made cautiously and under close supervision, with frequent monitoring to detect early signs of disease progression. Ancillary diagnostic tools, such as OCT and visual field testing, can provide essential support in assessing disease stability during this period [

12].

In conclusion, pregnancy induces a consistent and often beneficial reduction in IOP through hormonally and vascularly mediated mechanisms. Despite these advantages, pregnancy also introduces challenges related to accurate IOP assessment, variability in patient response, and the potential for paradoxical pressure increases. An individualized approach – incorporating alternative measurement techniques, careful monitoring, and a solid understanding of pregnancy-specific ocular physiology – is crucial for the effective management of glaucoma during this critical period [

3].

Table 2.

provides a concise overview of selected studies that address intraocular pressure (IOP) changes during pregnancy.

Table 2.

provides a concise overview of selected studies that address intraocular pressure (IOP) changes during pregnancy.

| No. |

Title |

Study Type |

Number of

Eyes |

Type of Treatment |

Results |

Conclusions |

| 1. |

A Narrative Review of the Complex Rela-tionship between Pregnancy and Eye Changes [2] |

review |

N/A |

N/A |

Hormonal influences during pregnancy lead to physiological ocular changes in Caucasian women, including alterations in corneal sensitivity, refractive status, intraocular pressure (IOP), and visual acuity. |

Periodic ophthalmologic evaluation may facilitate early detection and treatment of ocular changes, improving both short- and long-term visual prognosis and quality of life. |

| 2. |

Pregnancy hormone to control intraocular pressure? [5] |

update |

N/A |

N/A |

In pregnant glaucoma patients, IOP tends to decrease; however, in some cases, it may remain stable or even increase. |

The development of new targets for glaucoma therapy may enhance medical management of uncontrolled glaucoma, particularly when surgical options are not viable. |

| 3. |

Changes in intraocular pressure and central corneal thickness during pregnancy: a systematic review and Meta-analysis [4] |

Meta-Analysis |

N/A |

N/A |

Fifteen studies were included. IOP was significantly decreased during the second and third trimesters of pregnancy. |

IOP reduction during pregnancy is accompanied by increased central corneal thickness (CCT), particularly in the second and third trimesters. |

| 4. |

Tear Film Functions and Intraocular Pressure Changes in Pregnancy [6] |

Clinical study |

270 participants (165 pregnant women, 105 non-pregnant controls) |

N/A |

Mean values for IOP (mmHg), tear breakup time (TBUT, seconds), and Schirmer’s test (mm) were 13.24±2.18, 25.05±9.30, and 37.03±17.06 for pregnant women, and 14.24±2.66, 22.10±10.81, and 50.13±19.10 for controls, respectively. Schirmer’s values were significantly lower in pregnant women. |

The findings suggest the need for policy interventions promoting routine ocular examinations during pregnancy. |

| 5. |

Management of Glaucoma in Pregnancy[10] |

review |

N/A |

N/A |

IOP tends to be lower in pregnant women compared to non-pregnant women. |

Open communication and a close clinician–patient relationship are essential for optimizing outcomes in women of childbearing age with glaucoma. |

| 6. |

Is Estrogen a Therapeutic Target for Glaucoma?[11] |

review |

N/A |

N/A |

Elevated estrogen levels may be associated with a lower risk of glaucoma and glaucoma-related traits, such as reduced IOP. Pregnancy, a hyperestrogenic state, is linked to decreased IOP in the third trimester. |

Increasing evidence suggests that lifetime estrogen exposure may influence glaucoma pathogenesis. Estrogen may have a neuroprotective role in primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG), though further research is needed. |

3.2. Glaucoma Progression and Management During Pregnancy

Although pregnancy is often associated with a physiological reduction in IOP, its influence on glaucoma progression is more complex. For women with moderate to severe glaucoma or a history of rapid disease progression, pregnancy may paradoxically represent a period of increased risk due to hormonal and vascular changes that disrupt ocular homeostasis [

13,

16].

While relatively rare, glaucoma progression during pregnancy has been documented in case series and retrospective analyses. A notable study by Mathew et al. (2019) reported cases in which patients who discontinued their medications early in pregnancy – primarily due to concerns about fetal safety – subsequently experienced measurable optic nerve damage and visual field deterioration [

10]. These findings underscore the importance of rigorous monitoring throughout pregnancy, even when IOP readings ap-pear stable. It is hypothesized that glaucomatous damage may continue despite modest IOP reductions if optic nerve perfusion or neuroprotective mechanisms are compromised [

11].

Several physiological changes during pregnancy may affect optic nerve integrity independently of IOP. Hormonal fluctuations, increased blood volume, altered vascular resistance, and systemic fluid retention can collectively influence ocular perfusion pressure, potentially impairing nutrient delivery to retinal ganglion cells [

3]. Some researchers propose that the widespread vasodilation observed in pregnancy could paradoxically result in relative hypoperfusion of the optic nerve head, particularly in eyes already prone to vascular dysregulation [

18].

Behavioral and psychological factors also influence disease management during pregnancy. Anxiety, fatigue, and the demands of prenatal care may reduce adherence to ophthalmic follow-up visits, medication regimens, and self-monitoring routines [

12]. Missed appointments or inconsistent medication use can compromise disease control. Therefore, patient education and proactive counseling are essential, helping patients prioritize ocular health alongside prenatal responsibilities.

Effective management of glaucoma during pregnancy requires an individualized risk-benefit assessment for each patient. Key considerations include current disease severity, IOP control, treatment history, and the availability of non-pharmacologic alternatives such as laser therapy or minimally invasive glaucoma surgeries (MIGS) [

8]. These factors guide the development of a personalized care plan tailored to each patient’s needs. Cross-disciplinary collaboration between ophthalmologists and obstetricians becomes particularly critical when treatment intensification is necessary. A coordinated care approach helps safeguard both maternal vision and fetal well-being [

14].

Preconception counseling is an emerging and valuable strategy for women with glau-coma planning pregnancy. These consultations offer an opportunity to optimize disease control, transition to safer therapies where appropriate, and establish a multidisciplinary care framework before conception [

15]. Early discussions also facilitate contingency planning in the event that surgical intervention becomes necessary.

Although visual field-testing during pregnancy may be affected by fatigue and reduced attention, it remains an important tool. Imaging of the retinal nerve fiber layer and optic nerve head using optical coherence tomography (OCT) is also recommended to aid in the early detection of disease progression [

20].

Overall, managing glaucoma during pregnancy involves balancing disease stability with the safety of both mother and child. Clinical evaluations, OCT imaging, and cautious IOP monitoring should be conducted regularly, with management strategies re-evaluated each trimester to account for changing risks. The postpartum period also warrants close attention, as hormonal normalization and IOP rebound may reveal previously undetected disease progression [

21].

In summary, although glaucoma progression during pregnancy is relatively uncommon, it remains a significant clinical concern – particularly in high-risk patients. A proactive, flexible, and patient-centered approach – grounded in regular monitoring and interdisciplinary collaboration – can help ensure favorable outcomes for both mother and baby [

22].

Table 3.

presents a concise overview of studies addressing both medical and surgical management of glaucoma.

Table 3.

presents a concise overview of studies addressing both medical and surgical management of glaucoma.

| No. |

Title |

Study Type |

Number of

Patients/ eyes |

Type of Treatment |

Results |

Conclusions |

| 1. |

A Practical Guide to the Pregnant and Breastfeeding Patient with Glaucoma. Ophthalmol Glaucoma[8] |

update |

N/A |

N/A |

The FDA pregnancy categories are: A (deemed safe), B (possibly safe), C (adverse effects reported in animal studies), D (known risks but potential benefits), and X (known fetal risks that outweigh any possible benefit). Most glaucoma medications fall under category C. No medications in this classification were assigned to categories D or X. |

Ophthalmologists should be aware that there are safe options for treating glaucoma during pregnancy. Laser trabeculoplasty is often viable, and selected surgical interventions may also be appropriate. |

| 2. |

Pregnancy outcomes in the medical management of glaucoma: An interna-tional multicenter descriptive survey[14] |

Clinical case |

114 pregnancies in 56 patients (mean: 2.0 pregnancies per patient) |

Of the 111 analyzed pregnancies, 20 (18.0%) involved no medications, while 91 (82.0%) involved at least one. Topical medications: carbonic anhydrase inhibitors (n=45), beta-blockers (n=55), alpha-agonists (n=56), prostaglandin analogues (n=28) |

Reported outcomes included: preterm contractions/labor (6.3%), miscarriage (4.5%), stillbirth (4.5%), induction of labor (11.9%), unplanned caesarean section (13.9%), NICU admission (15.8%), congenital anomalies (8.1%), and low birth weight (10.9%). Most NICU admissions associated with alpha-agonists occurred after third-trimester exposure. |

The findings suggest a generally favorable safety profile for topical glaucoma medications during pregnancy. However, caution is advised with alpha-agonists in the third trimester due to their association with NICU admissions. Further research is warranted. |

| 3. |

Glaucoma Surgery in Pregnancy: A Case Series and Literature Review.[15] |

Case series |

6 eyes in 3 pregnant patients with uncontrolled glaucoma on maximum tolerated medications |

All 3 patients had juvenile open-angle glaucoma and were on various anti-glaucoma medications, including oral acetazolamide. The first case described underwent trabeculectomy without antimetabolites in both eyes. The second patient had an Ahmed valve implantation in both eyes during the second and third trimesters. The third case had a Baerveldt valve implantation under general anesthesia in the second trimester. |

Case 1. The IOP was 13 mm Hg2 weeks after the second operation in both eyes and then was stable at low teens throughout pregnancy. She gave birth to a normal baby at the 38th week of gestation. The baby weighed 3050 grams and her Apgar score was 10.

case 2. The IOP was 18 mm Hg in both eyes with dorzolamide over the last 2 weeks of pregnancy and 2 months after delivery. The mother gave birth to a healthy baby with a birth weight of 2750 grams and an Apgar score of 9. Case 3. One month later, the IOP was 14 mm Hg in the right eye and 16 mm Hg in the left eye. The patient delivered a healthy baby girl with a birth weight of 2523 grams at term with an Apgar score of 10 |

In selected pregnant glaucoma patients with medically uncontrolled intraocular pressure threatening vision, incisional surgery may lead to good outcomes for the patient with no risk for the fetus. |

| 4. |

Glaucoma medications in pregnancy[42] |

Review |

N/A |

N/A |

Category A: Safety established using human studies • Category B: Presumed safety based on animal studies, but no human studies • Category C: Uncertain safety, with no human studies and animal studies showing adverse effect • Category D: Unsafe; evidence of risk that in certain clinical circumstances may be justifiable • Category X: Definitely unsafe, with the risk of use outweighing any possible benefit. |

No topical antiglaucoma agents have strong evidence of safety to the fetus based on the human studies.

Alternate effective IOP lowering methods including surgery can be explored or achieved before the beginning of the pregnancy

|

3.2.1. Medical Treatment of Glaucoma During Pregnancy

The medical management of glaucoma during pregnancy presents distinct challenges that require a careful, individualized approach [

9]. The primary goal is to achieve optimal intraocular pressure (IOP) control while minimizing potential risks to the developing fetus. Although many topical and systemic antiglaucoma agents are effective at lowering IOP, their safety profiles during pregnancy vary considerably and are often based on limited clinical evidence or extrapolated from animal studies.

Beta-adrenergic blockers, such as timolol, are classified by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as Pregnancy Category C medications. These drugs can cross the placenta and have been associated with fetal bradycardia and neonatal respiratory de-pression, especially when used during the later stages of pregnancy [

8]. Nevertheless, beta-blockers remain among the more commonly prescribed agents during pregnancy, particularly when techniques such as punctal occlusion are used to minimize systemic absorption [

12].

Alpha-adrenergic agonists, particularly brimonidine, are classified as Category B and are generally considered safer during early gestation. Brimonidine shows minimal systemic absorption when administered topically and has not demonstrated teratogenic effects in animal studies [

2]. However, due to the risk of central nervous system depression in neonates, its use is typically discontinued several weeks prior to delivery [

14]. Apraclonidine is used less frequently due to its lower efficacy and higher incidence of side effects.

Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors (CAIs), such as dorzolamide and brinzolamide, are also classified as Category C. While topical formulations result in lower systemic exposure compared to oral acetazolamide, caution is still warranted. Oral acetazolamide has been linked to skeletal malformations in animal studies, although human data remain conflicting [

15]. As a result, systemic CAIs are generally avoided during the first trimester unless the maternal benefit clearly outweighs potential fetal risks [

23].

Prostaglandin analogs – including latanoprost, bimatoprost, and travoprost – are like-wise categorized as Category C and are typically avoided during pregnancy. These agents may induce uterine contractions by stimulating smooth muscle activity, raising the risk of miscarriage or preterm labor, especially when used in high doses [

24]. Although systemic absorption from ocular administration is minimal, the theoretical risks usually preclude their use except in cases refractory to other treatments [

25].

Cholinergic agents such as pilocarpine are rarely used during pregnancy due to their side effect profile and the lack of consistent safety data. These medications, also Category C, should only be considered when no safer alternatives are available [

13].

Netarsudil (Rhopressa) (Rho Kinase Inhibitor) is a newer glaucoma medication without an assigned FDA category. Although animal studies have not shown clear teratogenic-ity, there are many downstream targets of the rho kinase enzyme that could lead to adverse fetal events if inhibited [

12,

13,

14].

To minimize systemic drug absorption, several strategies can be employed. Techniques such as punctal occlusion for two to three minutes after instillation and eyelid closure can significantly reduce systemic exposure [

10]. Additional measures include using the lowest effective dose, minimizing dosing frequency, and opting for preservative-free formulations when available, to reduce ocular surface irritation and systemic absorption [

26].

In selected cases, it may be appropriate to temporarily suspend pharmacologic therapy during pregnancy. In such situations, alternative treatments such as selective laser trabeculoplasty (SLT) or minimally invasive glaucoma surgery (MIGS) may be consid-ered, depending on the severity of the disease and gestational timing. In

Table 4 we summarize common glaucoma medications class and their use in pregnancy.

Close collaboration between ophthalmologists and obstetricians is essential for managing glaucoma patients who require ongoing treatment during pregnancy. Shared de-cision-making, with a strong emphasis on patient values and preferences, is crucial to developing an effective and acceptable treatment plan. Preconception counseling is also highly recommended, as it allows for the adjustment of medications and the exploration of safer therapeutic alternatives prior to conception [

27,

28,

29].

In conclusion, the medical management of glaucoma during pregnancy requires navigating a narrow therapeutic window. Although several medications can be used with caution, successful outcomes depend on minimizing systemic exposure, implementing close monitoring, and considering non-pharmacologic therapies such as selective laser trabeculoplasty (SLT) or minimally invasive glaucoma surgery (MIGS) when appropriate [

22].

3.2.2. Selective Laser Trabeculoplasty (SLT) During Pregnancy

Selective laser trabeculoplasty (SLT) has become a particularly valuable treatment modality for pregnant women with glaucoma, especially for those who are unable to con-tinue or initiate pharmacologic therapies due to concerns about fetal safety [

9,

29]. As a noninvasive, outpatient procedure with a favorable safety profile, SLT offers several advantages within the unique physiological context of pregnancy.

SLT lowers intraocular pressure (IOP) by targeting pigmented cells within the trabec-ular meshwork using low-energy laser pulses, thereby enhancing aqueous humor out-flow through the conventional drainage pathway [

30]. Importantly, this mechanism avoids the systemic absorption associated with topical and oral glaucoma medications, making SLT an especially attractive option during pregnancy [

12].

One of the primary benefits of SLT in pregnant patients is the elimination of systemic drug exposure, thereby minimizing potential teratogenic risks [

13]. Since the procedure acts locally at the trabecular meshwork without introducing pharmacologic agents into systemic circulation, the risk of adverse fetal outcomes is negligible. Consequently, SLT is often considered either as a first-line therapy or as an adjunctive measure for patients seeking to avoid fetal drug exposure.

Although the evidence base consists primarily of case reports and small observational studies, outcomes have been promising. Authors such as Výborný (2017) and Strelow & Fleischman (2020) have advocated for the use of SLT in pregnancy, citing effective IOP reduction, favorable patient tolerance, and the absence of maternal or fetal complications [

13,

31]. While long-term data remain limited, SLT appears to be safe when per-formed by experienced clinicians.

Certain practical considerations must be addressed when planning SLT during preg-nancy. The procedure is typically performed in a sitting position, which is generally well tolerated in early gestation [

22]. In later stages of pregnancy, modifications may be necessary to accommodate maternal comfort and prevent inferior vena cava compression. Additionally, although SLT usually does not require systemic anesthesia, any topical anesthetic agents used should be selected with careful consideration of their safety during pregnancy [

26].

Postoperative care following SLT is minimal. Unlike filtering surgeries, SLT does not require intensive postoperative management or the use of corticosteroids, further en-hancing its appeal during pregnancy [

8]. Temporary use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) may be employed to address transient inflammation, but clinicians often prefer preservative-free, pregnancy-safe formulations and limit their use to short durations.

Another advantage of SLT is its repeatability; if the IOP-lowering effect diminishes over time, the procedure can be safely repeated. This makes SLT an excellent option for long-term management, particularly in women planning multiple pregnancies or seeking to minimize systemic drug exposure [

32,

33]. Some clinicians even advocate for preconception SLT to optimize IOP control before pregnancy.

Patient selection for SLT should be based on factors such as open-angle anatomy, mild to moderate IOP elevation, and intolerance or contraindication to medical therapy [

2,

34]. Its effectiveness in pregnant patients appears comparable to that observed in the general population, with similarly high success rates and minimal complications. However, careful individualized assessment remains essential.

SLT represents an effective and safe treatment option for glaucoma management during pregnancy. Its non-invasive nature, lack of systemic drug exposure, and well-documented efficacy make it particularly well-suited to this unique patient population. While larger, high-quality studies are needed to confirm long-term outcomes, current evidence supports the integration of SLT into the glaucoma treatment algorithm for pregnant patients.

3.2.3. Minimally Invasive Glaucoma Surgery (MIGS and MICS) During Pregnancy

Minimally Invasive Glaucoma Surgery (MIGS) and Minimally Invasive Conjunctival Surgery (MICS) represent significant advancements in the surgical management of glaucoma, offering less invasive alternatives to traditional filtering procedures. These techniques are characterized by smaller incisions, minimal tissue disruption, faster recovery times, and lower complication rates – qualities that are especially advantageous during pregnancy, when minimizing surgical risk and systemic exposure is paramount [

16].

Several MIGS procedures have been successfully performed in pregnant patients, particularly when pharmacological and laser therapies have proven inadequate. Devices such as the Xen Gel Stent, iStent, and Hydrus Microstent, as well as procedures like the Kahook Dual Blade goniotomy, have yielded favorable outcomes, although current data primarily originate from case reports and small case series [

26,

32].

For instance, Zehavi-Dorin et al. (2019) reported successful bilateral implantation of the Xen Gel Stent in a pregnant patient with early-onset primary open-angle glaucoma, achieving significant IOP reduction without adverse pregnancy outcomes [

35,

36,

37].

MIGS offers an appealing safety profile, largely due to its ab interno approach, which preserves conjunctival tissue and reduces the risk of postoperative complications such as bleb leaks. Furthermore, MIGS typically eliminates the need for antimetabolites such as mitomycin C, whose safety during pregnancy has not yet been established [

38,

39]. Many MIGS procedures can be performed under local or topical anesthesia, thereby avoiding fetal exposure to systemic anesthetics [

40,

41,

42].

MICS, although less widely used, represents an innovative extension of minimally invasive techniques. By avoiding conjunctival incisions altogether, MICS promotes faster healing and facilitates bleb-independent IOP control. Early experiences suggest that MICS may offer a safer surgical option for selected pregnant patients, particularly those with advanced or refractory disease [

30,

43].

Surgical decision-making regarding the use of MIGS or MICS during pregnancy must consider disease severity, gestational age, prior treatment responses, and patient preferences. A comprehensive, multidisciplinary strategy involving ophthalmologists, obstetricians, and anesthesiologists is essential to optimize outcomes [

44,

45].

Postoperatively, MIGS procedures typically require fewer medications and less intensive follow-up than conventional trabeculectomy – an advantage during pregnancy, when patient mobility and access to care may be limited [

13]. Moreover, MIGS often reduces or eliminates the need for prolonged corticosteroid therapy, further minimizing systemic exposure.

Nevertheless, it is important to recognize that the evidence supporting the use of MIGS and MICS during pregnancy remains preliminary and is based largely on case reports [

14]. While early outcomes are encouraging, these procedures should be used with caution and reserved for cases in which conservative therapies have failed.

Table 5.

summarizes the advantages of MIGS versus MICS during pregnancy.

Table 5.

summarizes the advantages of MIGS versus MICS during pregnancy.

| Procedure |

Advantages |

Disadvantages |

Use in pregnancy |

| MIGS |

- Safe

- Ab interno approach

- Low risk of postoperative complications (e.g., conjunctival leakage)

- Can be performed under local or topical anesthesia (avoiding fetal exposure to systemic agents) |

- May require antimetabolites like mitomycin C, whose safety in pregnancy is unconfirmed |

local or topical anesthesia, thereby avoiding fetal exposure to systemic anesthetics |

| MICS |

- Promotes faster healing

- Bleb-independent IOP control

-Avoids conjunctival incisions |

Same advanced or refractory disease |

Safer surgical option for selected pregnant patients

|

In conclusion, MIGS and MICS represent promising minimally invasive surgical alternatives for the management of glaucoma during pregnancy. Their favorable safety pro-files, compatibility with local anesthesia, and reduced postoperative requirements make them attractive options for selected pregnant patients requiring surgical intervention. Ongoing research is essential to fully establish their efficacy and safety in this unique patient population.

3.2.4. Surgical Treatment: Trabeculectomy During Pregnancy

Trabeculectomy remains a cornerstone surgical option for the management of glaucoma, typically reserved for moderate to severe cases unresponsive to medical or laser interventions. In the context of pregnancy, however, the decision to proceed with trabeculectomy requires a careful risk-benefit analysis, weighing potential risks to both maternal and fetal health.

A major concern with trabeculectomy during pregnancy is the use of adjunctive anti-metabolites such as mitomycin C (MMC) and 5-fluorouracil (5-FU). Although these agents enhance surgical success by reducing postoperative fibrosis and bleb failure, their potential for systemic absorption and teratogenicity presents significant concerns. Neither MMC nor 5-FU is FDA-approved for use during pregnancy, and animal studies suggest embryotoxic effects. Consequently, their use is generally avoided or applied with caution, typically during the second trimester when organogenesis is complete and surgical intervention is deemed necessary [

15,

26].

Clinical evidence – primarily from case reports and small series – indicates that tra-beculectomy can be performed safely during pregnancy using local anesthesia to minimize fetal exposure. For example, Banad et al. (2020) reported successful outcomes in pregnant patients who underwent trabeculectomy with modified techniques minimizing or omitting antimetabolite use [

32]. In some cases, safer adjunctive alternatives such as collagen matrix implants (e.g., Ologen) have been employed to support surgical outcomes without the risks associated with conventional antimetabolites [

40].

The choice of anesthesia is critical. Local techniques, including peribulbar and sub-Tenon’s blocks, are preferred due to their minimal systemic absorption and low fetal risk. Lidocaine, classified as an FDA Category B drug, is generally considered safe during pregnancy. General anesthesia should be reserved for cases where local anesthesia is inadequate and must be administered under multidisciplinary oversight involving anesthesiologists and maternal-fetal medicine specialists [

22,

41,

42].

While the core steps of trabeculectomy remain consistent, procedural modifications are recommended during pregnancy. These include optimizing maternal positioning to avoid inferior vena cava compression, minimizing surgical time, and selecting intraoperative agents with favorable safety profiles. Gentle tissue handling and the use of absorbable sutures are advised to reduce postoperative inflammation and limit the need for prolonged corticosteroid therapy, thereby minimizing systemic exposure [

9].

Postoperative management must also be carefully planned. Although corticosteroids are essential for controlling inflammation, shortened treatment regimens or substitution with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) may be appropriate. Regular follow-up is essential to monitor bleb function, IOP stability, and wound healing. Non-invasive imaging modalities such as anterior segment optical coherence tomography (OCT) offer a safe and effective means of assessing bleb morphology without risk to the fetus [

10,

44,

45].

Regarding surgical timing, the second trimester is generally considered the safest period for elective ocular surgery, as it avoids the higher risk of spontaneous abortion in the first trimester and preterm labor in the third. Nevertheless, urgent surgical intervention may be required at any stage if there is a rapid rise in IOP or progressive optic nerve damage, necessitating an individualized approach [

37,

46].

Psychological preparedness and comprehensive informed consent are crucial, especially given the heightened anxiety many pregnant patients experience concerning fetal risks. Thorough counseling, clear communication of both known and potential risks, and shared decision-making are essential components of ethical, patient-centered care [

8,

47,

48].

Although trabeculectomy during pregnancy poses distinct challenges, it can be per-formed safely and effectively when conducted under carefully controlled conditions. For patients at significant risk of vision loss who cannot be managed adequately with medical or laser therapies, trabeculectomy remains a vital surgical option [

5,

49]. With meticulous planning, judicious anesthesia use, and robust interdisciplinary collaboration, favorable outcomes for both mother and fetus can be successfully achieved [

16,

50].

Table 6 summarizes the advantages and pregnancy-specific considerations of trabeculectomy.

In general, the therapeutic trimester plan of pregnancy and the complications that may occur must be known; therefore, the table below describes the drugs and related studies that can be administered during preconception. The administration of topical anti-glaucoma medications during pregnancy is highly dependent on the stage of gestation. During the preconception period, it is advisable to establish a comprehensive glaucoma management plan in advance of conception. Patients should be thoroughly counseled about the potential risks of anti-glaucoma pharmacotherapy during pregnancy and the possible need for laser or surgical intervention prior to conception. In the first trimester, anti-glaucoma medications are generally contraindicated, and discontinuation is advised if treatment has already commenced. Among the available agents, brimonidine – classified as a category B drug – may be considered a relatively safe option during this period, particularly when combined with punctal occlusion to minimize systemic absorption. Surgical intervention is typically avoided in the first trimester due to restrictions on the use of anesthetic agents. In contrast, laser therapy is regarded as safe and may be employed throughout all trimesters of pregnancy. In the second trimester, brimonidine remains the preferred first-line agent. Beta-blockers may also be used, but only under strict maternal and fetal monitoring due to the potential for systemic side effects. Prostaglandin analogues, although effective, carry an increased risk of preterm labor and should therefore be used with caution. During the third trimester, beta-blockers, prostaglandin analogues, and carbonic anhydrase inhibitors may be administered, but only following a careful risk-benefit assessment. Anti-glaucoma surgery may be performed, if necessary, during the second trimester with appropriate precautions. Normal vaginal delivery does not appear to significantly affect intraocular pressure in otherwise healthy women. In the postpartum period – particularly during lactation – caution is warranted: brimonidine is contraindicated due to the risk of central nervous system depression in the neonate, while beta-blockers should be used with caution, especially in newborns with congenital cardiac conditions. [

2,

7,

8,

10,

14,

15]. (

Table 7)

4. Discussion

The management of glaucoma during pregnancy continues to evolve, driven by tech-nological advancements, a deeper understanding of gestational ocular physiology, and a growing body of evidence regarding the safety and efficacy of available treatments. Although current strategies – ranging from medical therapy to laser interventions and surgical procedures – provide a strong foundation for care, there remains a critical need for further research to refine management approaches and minimize risks to both mother and fetus. Future therapeutic strategies should focus on identifying interventions that offer effective intraocular pressure control while exerting minimal systemic effects.

4.1. Emerging Glaucoma Medications and Safety Considerations

An important frontier in glaucoma management is the development of medications with improved safety profiles for use during pregnancy. Given the limited clinical data on existing therapies, therapeutic decision-making remains complex and challenging [

4,

15,

51]. Expanding our understanding of the teratogenic risks associated with current drugs, along with the development of formulations that exhibit favorable pharmaco-kinetic and pharmacodynamic properties during pregnancy, holds significant promise for improving outcomes [

52].

Future research is likely to focus on the development of selective carbonic anhydrase inhibitors (CAIs) and prostaglandin analogs designed to minimize systemic absorption and, consequently, fetal exposure [

52,

53]. Innovations in nano formulations and targeted drug delivery systems offer additional potential, enabling highly localized treatment with minimal systemic effects. Ultimately, the goal is to develop therapies that not only provide effective intraocular pressure (IOP) control but are also demonstrably safe for use during pregnancy [

16].

4.2. Advances in Laser Therapies

Selective laser trabeculoplasty (SLT) has already become a mainstay in the management of glaucoma during pregnancy. Nevertheless, ongoing innovations in laser technology continue to expand therapeutic possibilities. Emerging procedures and refinements of established techniques aim to achieve more precise and effective intraocular pressure (IOP) reduction while minimizing risks to both maternal and fetal health [

16].

Micro-invasive laser modalities, such as laser suture lysis and laser cyclophotocoagulations, represent promising alternatives for patients with advanced or treatment-resistant disease. Additionally, combining laser therapies with adjunctive pharmacological agents may enhance long-term disease control while reducing the need for systemic medications [

16].

Further research is essential to optimize procedural timing, laser parameters, and safety protocols specifically for pregnant patients. A deeper understanding of how pregnancy induced hormonal and vascular changes influence laser outcomes will be critical for developing individualized treatment strategies. Advances in imaging technologies, such as enhanced depth imaging optical coherence tomography (EDI-OCT), will further support real-time monitoring and personalized care.

4.3. Progress in Minimally Invasive Surgical Procedures

Minimally invasive glaucoma surgeries (MIGS) represent a rapidly expanding field, offering significant advantages in the management of glaucoma during pregnancy. Compared to traditional filtering surgeries, MIGS techniques involve smaller incisions, shorter recovery times, and a lower risk of complications – features that are particularly valuable in pregnant patients [

4,

10,

12,

25].

Devices such as the iStent, Hydrus Microstent, and Xen Gel Stent have shown encourage-aging outcomes; however, further research is needed to confirm their long-term safety and efficacy in pregnant populations. Of particular interest is the advancement of conjunctival-sparing MIGS techniques, which aim to preserve conjunctival integrity and reduce the risk of postoperative complications [

16].

Minimally invasive conjunctival surgeries (MICS) further build upon this paradigm by eliminating the need for conjunctival incisions, promoting bleb-independent IOP con-trol, and potentially offering safer surgical options for pregnant patients. In addition, advancements in minimally invasive cyclophotocoagulation – which targets aqueous humor production – may provide effective alternatives for cases of refractory glaucoma [

16].

Despite these promising developments, large-scale, well-designed studies are essential to validate the safety and efficacy of MIGS and MICS procedures during pregnancy.

4.4. Telemedicine and Remote Monitoring Innovations

The integration of telemedicine and remote monitoring technologies presents a promising avenue for enhancing glaucoma management during pregnancy. Given the logistical challenges often associated with frequent in-person visits during gestation, tele-medicine offers a valuable means of maintaining consistent and accessible care.

Remote monitoring devices, such as home tonometer’s and digital imaging systems, allow for regular tracking of intraocular pressure and ocular health from the comfort of the patient’s home, thereby reducing the need for travel and in-clinic appointments [

4,

16].

Additionally, telemedicine enables real-time communication between patients and healthcare providers, supports adherence to medication regimens, and facilitates early detection of complications. As digital health platforms continue to advance, their role in patient education, symptom monitoring, and treatment oversight is expected to become increasingly central to improving outcomes for pregnant women managing glaucoma [

16].

4.5. Personalized and Precision Medicine Approaches

Advancements in genetics and molecular biology are paving the way for personalized medicine approaches in glaucoma care. These may include genetic screening, ocular biomarker profiling, and individualized imaging strategies [

16,

53].

A more thorough understanding of the interactions between pregnancy-related hormonal changes and glaucoma risk factors will further support the development of tailored treatment plans that prioritize both maternal and fetal health. As precision medicine continues to evolve, clinicians will be better equipped to predict disease progressions, optimize therapeutic responses, and select the safest and most effective interventions for each patient [

53].

4.6. Strengthening Multidisciplinary Care Models

Effective management of glaucoma during pregnancy requires close multidisciplinary collaboration among ophthalmologists, obstetricians, maternal-fetal medicine specialists, and anesthesiologists. Integrated care models promote coordinated decision-making, optimize risk management, and ensure comprehensive attention to both ocular and systemic health [

7,

16,

54].

Furthermore, such collaborative approaches enhance patient education and empower pregnant women to actively engage in informed decisions about their treatment and care. In managing complex conditions like glaucoma during pregnancy, a multidisci-plinary approach is essential to achieving the best possible outcomes for both mother and child [

16,

46].

4.7. Research Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, although a comprehensive literature review was conducted, the number of articles that met the inclusion and exclusion criteria was relatively small. Second, the heterogeneity of the included studies limited the feasibility of a consistent and comparative analysis. Furthermore, the number of original experimental studies was notably low – an anticipated limitation, given that such research can only be ethically conducted using animal models.

5. Conclusions

The future of glaucoma management during pregnancy is full of promise. Advances in pharmacologic therapies, innovative laser and surgical techniques, telemedicine, and the evolution of precision medicine are poised to transform the field. Ongoing research and interdisciplinary collaboration will be essential in developing new approaches while safeguarding both maternal and fetal health.

As innovation progresses, clinicians will be better equipped to deliver safe, personalized, and effective glaucoma care for pregnant patients, ultimately improving outcomes for this unique and often challenging population.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.A., B.D. and F.C.D; methodology, N.A., B.D., and F.C.D; software, formal analysis C.M.B. and T.A.; resources, data curation, validation N.A., T.A.,F.C.D and B.D.; investigation, N.A., B.D., T.A. and F.C.D; visualization, supervision N.A. and B.D.; writing – original draft, writing – review and editing, N.A. and B.D.; project administration, funding acquisition N.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Yenerel, N.M.; Küçümen, R.B. Pregnancy and the Eye. Turk. J. Ophthalmol. 2015, 45, 213–219. [CrossRef]

- Anton N, Doroftei B, Ilie O-D, Ciuntu R-E, Bogdănici CM, Nechita-Dumitriu I. A Narrative Review of the Complex Relationship between Pregnancy and Eye Changes. Diagnostics. 2021; 11(8):1329. [CrossRef]

- Khong EWC, Chan HHL, Watson SL, Lim LL. Pregnancy and the eye. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2021 Nov 1; 32(6):527-535. [CrossRef]

- Wang C, Li AL, Pang Y, Lei YQ, Yu L. Changes in intraocular pressure and central corneal thickness during pregnancy: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Int J Ophthalmol. 2017 Oct 18;10(10):1573-1579. [CrossRef]

- Akkara JD, Kuriakose A. Commentary: Pregnancy hormone to control intraocular pressure? Indian J Ophthalmology. 2020 Oct;68(10):2121. [CrossRef]

- Ibraheem, W.A.; Ibraheem, A.B.; Tijani, A.M.; Oladejo, S.; Adepoju, S.; Folohunso, B. Tear Film Functions and Intraocular Pressure Changes in Pregnancy. Afr. J. Reprod. Health 2015, 19, 118–122.

- Sethi, H.S.; Naik, M.; Gupta, V.S. Management of glaucoma in pregnancy: Risks or choices, a dilemma? Int. J.Ophthalmol. 2016, 9, 1684–1690. [CrossRef]

- Belkin A, Chen T, DeOliveria AR, Johnson SM, Ramulu PY, Buys YM; American Glaucoma Society and the Canadian Glaucoma Society. A Practical Guide to the Pregnant and Breastfeeding Patient with Glaucoma. Ophthalmol Glaucoma. 2020 Mar-Apr;3(2):79-89. [CrossRef]

- Salim S. Glaucoma in pregnancy. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2014 Mar;25(2):93-97. [CrossRef]

- Mathew S, Harris A, Ridenour CM, Wirostko BM, Burgett KM, Scripture MD, Siesky B. Management of Glaucoma in Pregnancy. J Glaucoma. 2019 Oct;28(10):937-944. [CrossRef]

- Dewundara SS, Wiggs JL, Sullivan DA, Pasquale LR. Is Estrogen a Therapeutic Target for Glaucoma? Semin Ophthalmol. 2016;31(1-2):140-146. [CrossRef]

- Kumari R, Saha BC, Onkar A, Ambasta A, Kumari A. Management of glaucoma in pregnancy - balancing safety with efficacy. Ther Adv Ophthalmol. 2021 Jun 28;13:25158414211022876. [CrossRef]

- Strelow, B.; Fleischman, D. Glaucoma in pregnancy: An update. Curr. Opin. Ophthalmol. 2020, 31, 114–122. [CrossRef]

- Kaufman AR, Ali Al-Djasim L, Rivkin AC, Al-Futais M, Venkataraman G, Vimalanathan M, Sahu A, Ahluwalia NS, Shakya R, Vajaranant TS, Wilensky JT, Edward DP, Aref AA. Pregnancy outcomes in the medical management of glaucoma: An international multicenter descriptive survey. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2024 Mar;34(2):471-479. [CrossRef]

- Razeghinejad M.R.; Masoumpour Md, M.; Eghbal Md, M.H.; Myers Md, J.S.; Moster Md, M.R. Glaucoma Surgery in Pregnancy: A Case Series and Literature Review. Iran. J. Med. Sci. 2016, 41, 437–445.

- Salvetat ML, Toro MD, Pellegrini F, Scollo P, Malaguarnera R, Musa M, Mereu L, Tognetto D, Gagliano C, Zeppieri M. Advancing Glaucoma Treatment During Pregnancy and Breastfeeding: Contemporary Management Strategies and Prospective Therapeutic Developments. Biomedicines. 2024 Nov 25;12(12):2685. [CrossRef]

- Webber, J.; Charlton, M.; Johns, N. Diabetes in pregnancy: Management of diabetes and its complications from preconception to the postnatal period (NG3). Br. J. Diabetes Vasc. Dis. 2015, 15, 107. [CrossRef]

- Morrison, J.L.; Hodgson, L.A.B.; Lim, L.L.; Al-Qureshi, S. Diabetic retinopathy in pregnancy: A review. Clin. Experiment. Ophthalmol. 2016, 44, 321–334. [CrossRef]

- Egan, A.M.; McVicker, L.; Heerey, A.; Carmody, L.; Harney, F.; Dunne, F.P. Diabetic retinopathy in preg-nancy: A population-based study of women with pregestational diabetes. J. Diabetes Res. 2015, 2015, 310239. [CrossRef]

- Perez CI, Mellado F, Jones A, Colvin R. Trabeculectomy Combined With Collagen Matrix Implant (Ologen). J Glaucoma. 2017 Jan;26(1):54-58. [CrossRef]

- Seo D, Lee T, Kim JY, Seong GJ, Choi W, Bae HW, Kim CY. Glaucoma Progression after Delivery in Patients with Open-Angle Glaucoma Who Discontinued Glaucoma Medication during Pregnancy. J Clin Med. 2021 May 19;10(10):2190. [CrossRef]

- Pol S, Upasani SD. Glaucoma in Pregnancy: Know What Next!! J Obstet Gynaecol India. 2022 Dec;72(Suppl 2):366-368. [CrossRef]

- Al-Saleem AI, Al-Jobair AM. Possible association between acetazolamide administration during pregnancy and multiple congenital malformations. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2016 Apr 15; 10:1471-6. [CrossRef]

- Vajaranant TS. Clinical Dilemma-Topical Prostaglandin Use in Glaucoma During Pregnancy. JAMA Oph-thalmol. 2022 Jun 1;140(6):637-638. [CrossRef]

- Mansoori, Tarannum MS. Management of Glaucoma in Pregnancy. Journal of Glaucoma 29(4):p e26-e27, April 2020. [CrossRef]

- Pellegrino M., D’Oria, L.; De Luca, C.; Chiaradia, G.; Licameli, A.; Neri, C.; Nucci, M.; Visconti, D.; Caruso, A.; De Santis, M. Glaucoma Drug Therapy in Pregnancy: Literature Review and Teratology Information Service (TIS) Case Series. Curr. Drug Saf. 2018, 13, 3–11. [CrossRef]

- Schockman, S.; Glueck, C.J.; Hutchins, R.K.; Patel, J.; Shah, P.; Wang, P. Diagnostic ramifications of ocular vascular occlusion as a first thrombotic event associated with factor V Leiden and prothrombin gene het-erozygosity. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2015, 9, 591–600. [CrossRef]

- Khadka, D.; Bhandari, S.; Bajimaya, S.; Thapa, R.; Paudyal, G.; Pradhan, E. Nd:YAG laser hyaloidotomy in the management of Premacular Subhyaloid Hemorrhage. BMC Ophthalmol. 2016, 16, 41. [CrossRef]

- Lee JY, Kim JM, Kim SH, Kim IT, Kim HT, Chung PW, Bae JH, Won YS, Lee MY, Park KH; Epidemiologic Survey Committee of the Korean Ophthalmological Society. Associations Among Pregnancy, Parturition, and Open-angle Glaucoma: Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2010 to 2011. J Glau-coma. 2019 Jan; 28(1):14-19. [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.J.; Hall, L.; Liu, J. Improving Glaucoma Surgical Outcomes with Adjunct Tools. J. Curr. Glaucoma Pract. 2018, 12, 19–28. [CrossRef]

- Výborný P, Sičáková S, Flórová Z, Sováková I. Selective Laser Trabeculoplasty - Implication for Medicament Glaucoma Treatment Interruption in Pregnant and Breastfeeding Women. Cesk Slov Oftalmol. 2017 Sum-mer;73(2):61-63. Czech.

- Banad NR, Choudhari N, Dikshit S, Garudadri C, Senthil S. Trabeculectomy in pregnancy: Case studies and literature review. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2020 Mar; 68(3):420-426. [CrossRef]

- Toda, J.; Kato, S.; Sanaka, M.; Kitano, S. The effect of pregnancy on the progression of diabetic retinopathy. Jpn. J. Ophthalmol. 2016, 60, 454–458. [CrossRef]

- Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT); Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complica-tions (EDIC) Research Group; Lachin, J.M.; White, N.H.; Hainsworth, D.P.; Sun, W.; Cleary, P.A.; Nathan, D.M. Effect of intensive diabetes therapy on the progression of diabetic retinopathy in patients with type 1 diabetes: 18 years of follow-up in the DCCT/EDIC. Diabetes 2015, 64, 631–642. [CrossRef]

- Zehavi-Dorin, T.; Heinecke, E.; Nadkarni, S.; Green, C.; Chen, C.; Kong, Y.X.G. Bilateral consecutive Xen gel stent surgery during pregnancy for uncontrolled early-onset primary open angle glaucoma. Am. J. Oph-thalmol. Case Rep. 2019, 15, 100510. [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, S.-F.; Letafat-Nejad, M.; Ashrafi, E.; Delshad-Aghdam, H. A survey of ophthalmologists and gynecologists regarding termination of pregnancy and choice of delivery mode in the presence of eye dis-eases. J. Curr. Ophthalmol. 2017, 29, 126–132. [CrossRef]

- Kurtz, W.S.; Glueck, C.J.; Hutchins, R.K.; Sisk, R.A.; Wang, P. Retinal artery and vein thrombotic occlusion during pregnancy: Markers for familial thrombophilia and adverse pregnancy outcomes. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2016, 10, 935-938. [CrossRef]

- Schlote T, Chan E, Germann U. Ophthalmika in der Schwangerschaft [Ophthalmic agents during pregnancy]. Ophthalmologie. 2024 Apr;121(4):333-348. German. [CrossRef]

- Sen, M.; Midha, N.; Sidhu, T.; Angmo, D.; Sihota, R.; Dada, T. Prospective Randomized Trial Comparing Mitomycin C Combined with Ologen Implant versus Mitomycin C Alone as Adjuvants in Trabeculecto-my.Ophthalmol. Glaucoma 2018, 1, 88–98. [CrossRef]

- Colás-Tomás, T.; López Tizón, E. Ex-PRESS mini-shunt implanted in a pregnant patient with iridocorneal endothelial syndrome. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 2019, 30, NP25–NP28. [CrossRef]

- Scheetz TE, Faga B, Ortega L, Roos BR, Gordon MO, Kass MA, Wang K, Fingert JH. Glaucoma risk alleles in the ocular hypertension treatment study. Ophthalmology. 2016;123(12):2527–2536. [CrossRef]

- Razeghinejad MR. Glaucoma medications in pregnancy. Oman J Ophthalmol. 2018 Sep-Dec;11(3):195-199. [CrossRef]

- Boardman H, Ormerod O, Leeson P. Haemodynamic changes in pregnancy: what can we learn from com-bined datasets? Heart. 2016;102(7):490–491. [CrossRef]

- Drake SC, Vajaranant TS. Evidence-Based Approaches to Glaucoma Management During Pregnancy and Lactation. Curr Ophthalmol Rep. 2016 Dec;4(4):198-205. [CrossRef]

- Agrawal N, Agarwal LT, Lavaju P, Chaudhary SK. Physiological Ocular Changes in Various Trimesters of Pregnancy. Nepal J Ophthalmol. 2018 Jan;10(19):16-22. [CrossRef]

- Blumen-Ohana E, Sellem E. Grossesse & glaucome : recommandations SFO–SFG [Pregnancy & glaucoma: SFO-SFG recommendations]. J Fr Ophtalmol. 2020 Jan; 43(1):63-66.

- Pitukcheewanont O, Tantisevi V, Chansangpetch S, Rojanapongpun P. Factors related to hypertensive phase after glaucoma drainage device implantation. Clin Ophthalmol. 2018 Aug 17;12:1479-1486. [CrossRef]

- Perez, C.I.; Mellado, F.; Jones, A.; Colvin, R. Trabeculectomy Combined with Collagen Matrix Im-plant(Ologen). J. Glaucoma 2017, 26, 54–58. [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto Y, Michihata N, Yamana H, Shigemi D, Morita K, Matsui H, Yasunaga H, Aihara M. Intraocular pressure-lowering medications during pregnancy and risk of neonatal adverse outcomes: a propensity score analysis using a large database. Br J Ophthalmol. 2021 Oct;105(10):1390-1394. [CrossRef]

- Patel P, Harris A, Toris C, Tobe L, Lang M, Belamkar A, Ng A, Verticchio Vercellin AC, Mathew S, Siesky B. Effects of Sex Hormones on Ocular Blood Flow and Intraocular Pressure in Primary Open-angle Glaucoma: A Review. J Glaucoma. 2018 Dec;27(12):1037-1041. [CrossRef]

- Moneta-Wielgos,J.;Brydak-Godowska,J.;Golebiewska,J.; Lipa,M.; Rekas, M.The assessment of retina in pregnant women with myopia. Neuro Endocrinol. Lett. 2018, 39, 321–324.

- Wojtowiec A, Wojtowiec P, Misiuk-Hojto M. The role of estrogen in the development of glacomatous optic neuropathy. Klin Oczna. 2016 Sep;117(4):275-277.

- Huang Q, Rui EY, Cobbs M, Dinh DM, Gukasyan HJ, Lafontaine JA, Mehta S, Patterson BD, Rewolinski DA, Richardson PF, Edwards MP. Design, synthesis, and evaluation of NO-donor containing carbonic anhydrase inhibitors to lower intraocular pressure. J Med Chem. 2015;58(6):2821–2833. [CrossRef]

- Zhao SH, Kim CK, Al-Khaled T, Chervinko MA, Wishna A, Mirza RG, Vajaranant TS. Comparative insights into the role of sex hormones in glaucoma among women and men. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2025 Mar;105:101336. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).