Submitted:

20 August 2025

Posted:

21 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

2.2. Behavioural Tests

2.2.1. Open Field

2.2.2. Forced Swim Test (FST)

2.2.3. Pre-Pulse Inhibition (PPI) of Acoustic Startle Response (ASR)

2.2.4. Latent Inhibition (LI)

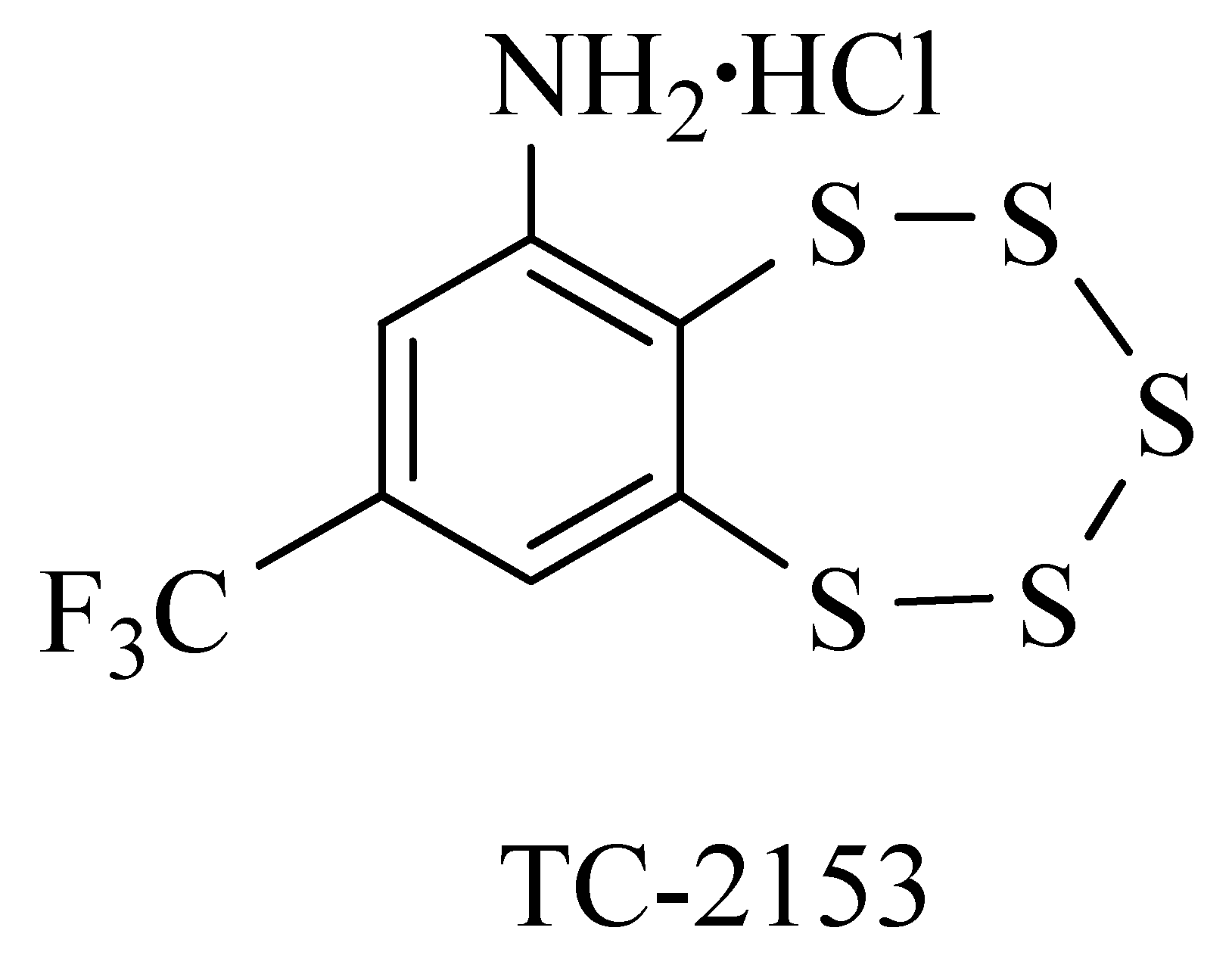

2.3. Drugs

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

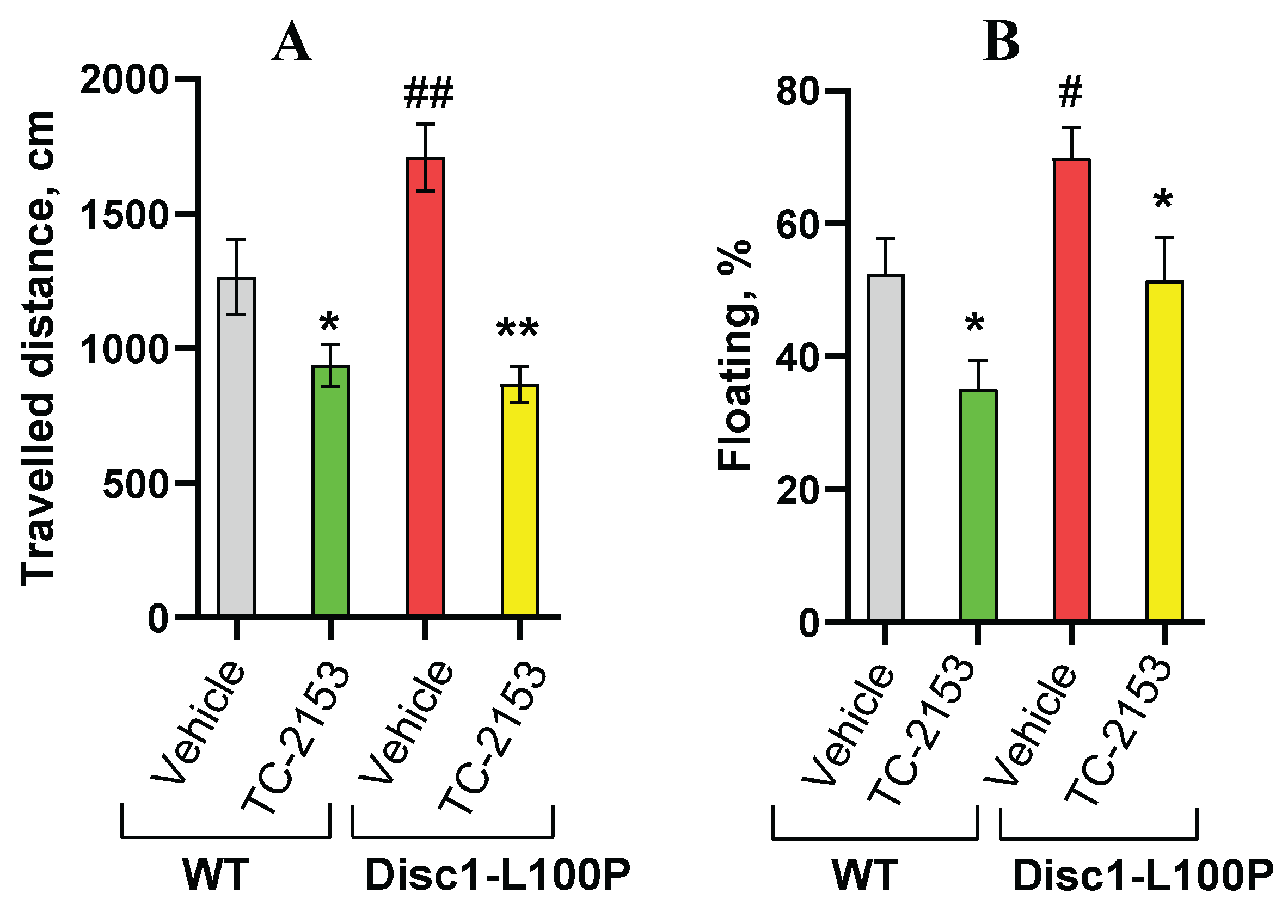

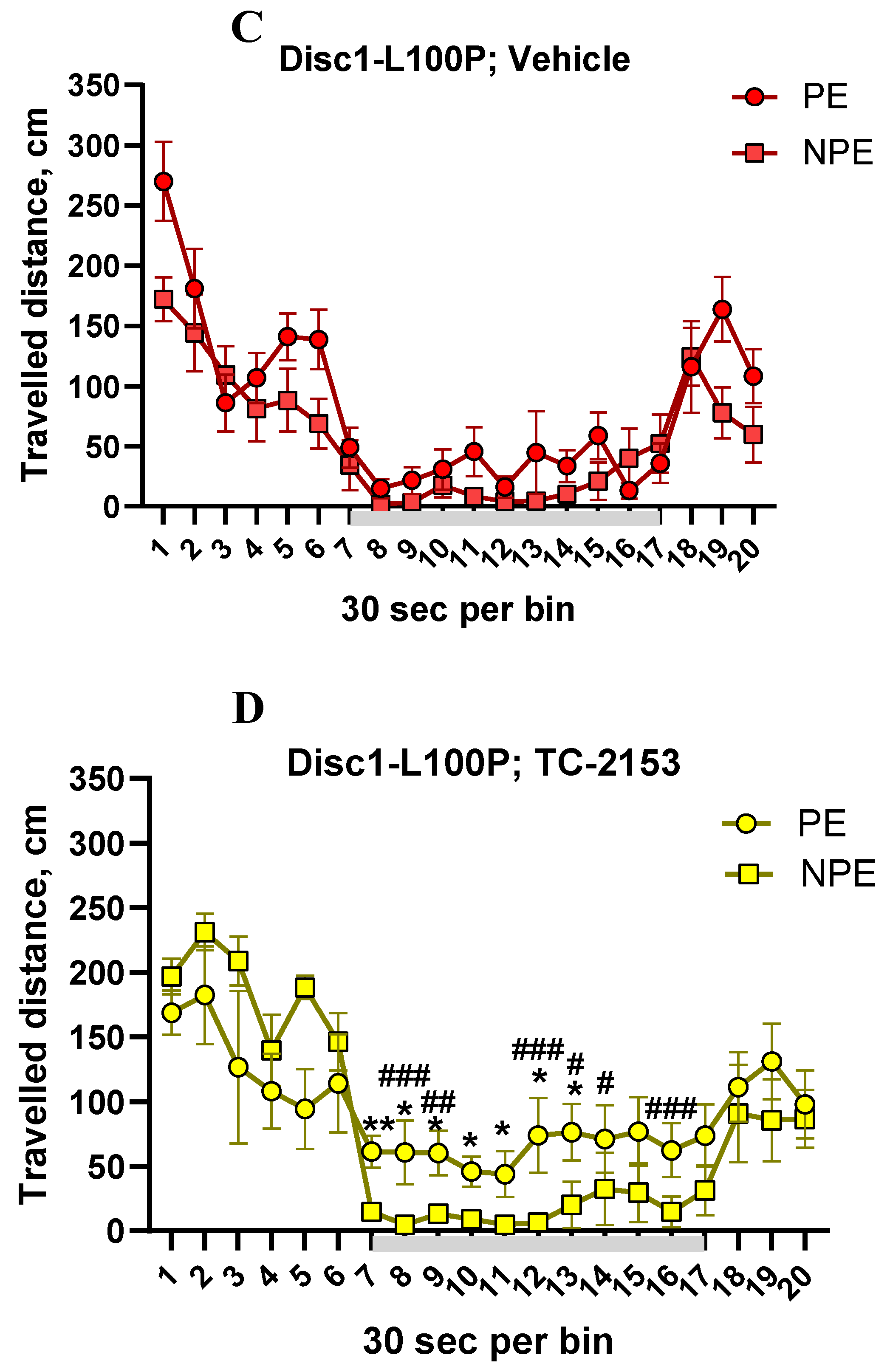

3.1. Effects of TC-2153 on Hyperactivity Assessed in the Open Field

3.2. Effects of TC-2153 on Behavioral Despair Assessed in the FST

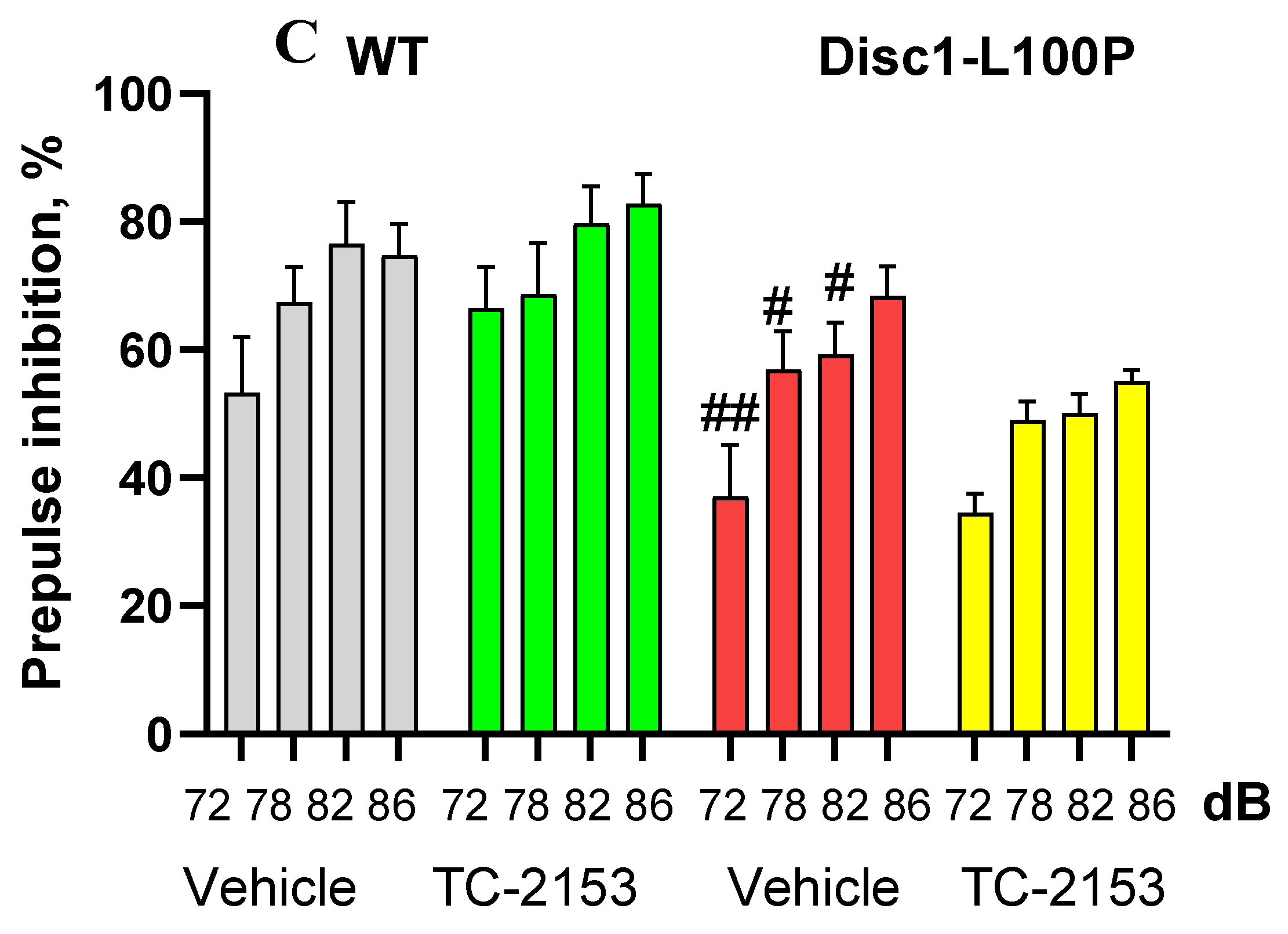

3.3. Effects of TC-2153 on Sensorimotor Gating Assessed by PPI of ASR

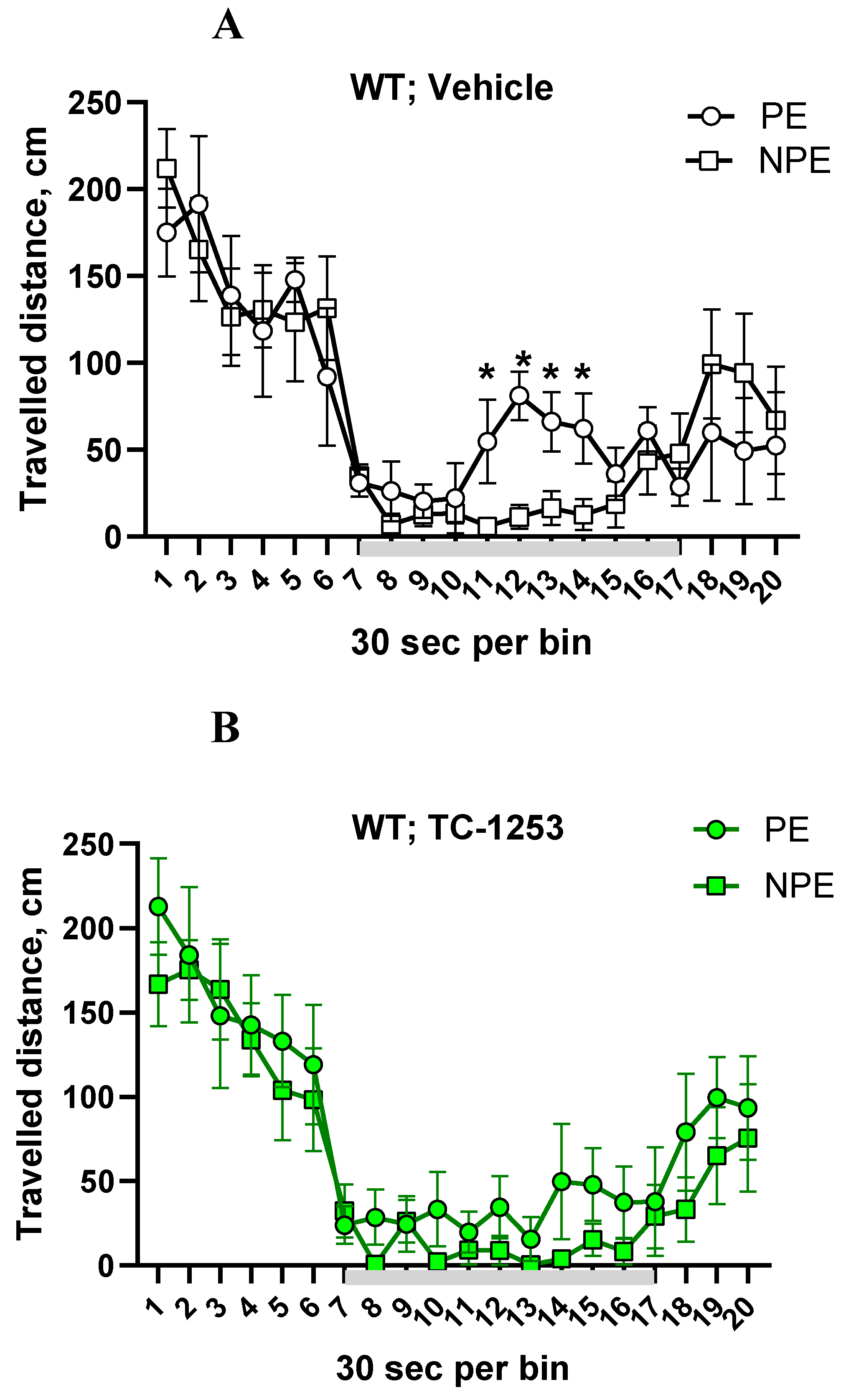

3.4. Effects of TC-2153 on Decremental Attention Assessed by LI

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Snyder, S.H. The dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia: focus on the dopamine receptor. Am J Psychiatry 1976, 133, 197-202. [CrossRef]

- Howes, O.D., Kapur, S. The dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia: version III – the final common pathway. Schizophr Bull, 2009, 35, 549-562. [CrossRef]

- Howes, S.R., Dalley, J.W., Morrison, C.H., Robbins, T.W., Everitt, B.J. Left ward shift in the acquisition of cocaine self-administration in isolation– reared rats: relationship to extracellular levels of dopamine, serotonin and glutamate in the nucleus accumbens and amygdala– striatal FOS expression. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2000, 151, 55-63. [CrossRef]

- Jones, G.H., Hernandez, T.D., Kendall, D.A., Marsden, C.A., Robbins, T.W. Dopaminergic and serotonergic function following isolation rearing in rats: study of behavioural responses and postmortem and in vivo neurochemistry. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 1992, 43, 17-35. [CrossRef]

- Pruessner, J.C., Champagne, F., Meaney, M.J., Dagher, A. Dopamine release in response to a psychological stress in humans and its relationship to early life maternal care: a positron emission tomography study using [11C]raclopride. J Neurosci 2004, 24, 2825-2831. [CrossRef]

- GBD 2017. Disease and injury incidence and prevalence collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet, 2018, 392, 1789-1858. [CrossRef]

- Seeman, P., Lee, T., Chau-Wong, M., Wong, K. Antipsychotic drug does and neuroleptic/dopamine receptors. Nature 1976, 261, 717-719. [CrossRef]

- Missale, C., Nash, S.R., Robinson, S.W., Robinson, S.W., Jaber, M., Caron, M.G. Dopamine receptors: from structure to function. Physiol Rev 1998, 78, 189-225. [CrossRef]

- Beaulieu, J-M, Gainetdinov, R.R., Caron, M.G. Akt/GSK3 signaling in the action of psychotropic drugs. Annual Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 2009, 49, 327-347. [CrossRef]

- Hanyaloglu, A.C., von Zatrow, M. Regulation of GPCRs by endocytic membrane trafficking and its potential implications. Annual Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 2008, 48, 537 – 568. [CrossRef]

- Su, P., Li, S., Chen, S., Lipina, T.V., Wang, M., Lai, T.K., Lee, F.H., Zhang, H., Zhai, D., Ferguson, S.S., Nobrega, J.N., Wong, A.H., Roder, J.C., Fletcher, P.J., Liu, F. A dopamine D2 receptor-DISC1 protein complex may contribute to antipsychotic-like effects. Neuron 2014, 4, 1302-1316. [CrossRef]

- Lipina, T.V., Kaidanovich-Beilin, O., Patel, S., Wang, M., Clapcote, S.J., Liu, F., Woodgett, J.R., Roder, J.C. Genetic and pharmacological evidence for schizophrenia-related Disc1 interaction with GSK-3. Synapse 2011, 65, 234-248. [CrossRef]

- Clapcote, S.J., Lipina. T.V., Millar, J.K., Mackie, S., Christie, S., Ogawa, F., Lerch, J.P., Trimble, K., Uchiyama, M., Sakuraba, Y., Kaneda, H., Shiroishi, T., Houslay, M.D., Henkelman, R.M., Sled, J.G., Gondo, Y., Porteous, D.J., Roder, J.C. Behavioral phenotypes of Disc1 missense mutations in mice. Neuron 2007, 54, 387-402. [CrossRef]

- Dahoun, T., Trossbach, S.V., Brandon, N.J., Korth, C., Howes, O.D. The impact of Disrupted-In-Schizophrenia (DISC1) on the dopaminergic system: a systematic review. Transl Psychiatry 2017, 7, e1015. [CrossRef]

- Carty, N.C., Xu, J., Kurup, P., Brouillette, J., Goebel-Goody, S.M., Austin, D.R., Yuan, P., Chen, G., Correa, P.R., Haroutunian, V., Pittenger, C., Lombroso, P.J. The tyrosine phosphatase STEP: implications in schizophrenia and the molecular mechanism underlying antipsychotic medications. Transl Psychiatry 2012, 2, e137. [CrossRef]

- Lombroso, P.J., Murdoch, G., Lerner, M. Molecular characterization of a protein-tyrosine-phosphatase enriched in striatum Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1991, 88, 7242-7246. [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.Y., Lee, H.J., Kim, Y.N., Yoon, S., Lee, J.E., Sun, W., Choi, E.J., Baik, J.H. Striatal-enriched protein tyrosine phosphatase regulates dopaminergic neuronal development via extracellular signal-regulated kinase signaling. Exp Neurol 2008, 214, 69-77. [CrossRef]

- Snyder, E.M., Nong, Y., Almeida, C.G., Paul, S., Moran, T., Choi, E.Y., Nairn, A.C., Salter, M.W., Lombroso, P.J., Gouras, G.K., Greengard, P. Regulation of NMDA receptor trafficking by amyloid-beta. Nat Neurosci 2005, 8, 1051-1058. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., Venkitaramani, D.V., Gladding, C.M., Zhang, Y., Kurup, P., Molnar, E., Collingridge, G.L., Lombroso, P.J. The tyrosinephosphatase STEP mediates AMPA receptor endocytosis after metabotropic glutamate receptor stimulation. J Neurosci 2008, 28, 10561–10566. [CrossRef]

- Paul, S., Nairn, A.C., Wang, P., Lombroso, P.J. NMDA-mediated activation of the tyrosine phosphatase STEP regulates the duration of ERK signaling. Nat Neurosci 2003, 6, 34-42. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.H., Liu, J., Lombroso, P.J. Striatal enriched phosphatise 61 dephosphorylates Fyn at phosphotyrosine 420. J Biol Chem 2002, 277, 24274–24279. [CrossRef]

- Xu, J., Kurup, P., Bartos, J.A., Patriarchi, T., Hell, J.W., Lombroso, P.J. STriatal-enriched protein tyrosine phosphatase (STEP) regulates Pyk2 activity. J Biol Chem 2012, 287, 20942-20956. [CrossRef]

- Goebel-Goody, S.M., Baum, M., Paspalas, C.D., Fernandez, S.M., Carty, N.C., Kurup, P., Lombroso, P.J. Therapeutic implications forstriatal-enriched protein tyrosine phosphatase (STEP) in neuropsychiatric disorders. Pharmacol Rev, 2012, 64, 65-87. [CrossRef]

- Khomenko, T.M., Tolstikova, T.G., Bolkunov, A.V., Dolgikh, M.P., Pavlova, A.V., Korchagina, D.V., Volcho, K.P., Salakhutdinov, N.F. 8–(Trifluoromethyl)–1,2,3,4,5–benzopentathiepin–6–amine: novel aminobenzopentathiepine having in vivo anticonvulsant and anxiolytic activities. Lett Drug Design Discov 2009, 6, 464-467. [CrossRef]

- Baguley, T.D.; Nairn, A.C., Lombroso, P.J., Ellman, J.A. Synthesis of benzopentathiepin analogs and their evaluation as inhibitor of the phosphatase STEP. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 2015, 25,1044-1046. [CrossRef]

- Xu, J., Kurup, P., Baguley, T.D., Foscue, E., Ellman, J.A., Nairn, A.C., Lombroso, P.J. Inhibition of the tyrosine phosphate STEP61 restores BDNF expression and reverses motor and cognitive deficits in phencyclidine-treated mice. Cell Mol Life Sci 2016, 73, 1503-1514. [CrossRef]

- Zong, M-m., Yuan, H-m., He, X., Zhou, Z-q., Qiu, X-d., Yang, J-j., Ji, M-h. Disruption of Striatal-Enriched protein tyrosine phosphatise signalling might contribute to memory impairment in a mouse model of sepsis-associated encephalopathy. Neurochem Res 2019, 44, 2832-2842. [CrossRef]

- Kulikova, E.A., Volcho, K.P., Salakhutdinov, N.F., Kulikov, A.V. Benzopentathiepine derivative, 8-(trifluoromethyl)-1,2,3,4,5-benzopentathiepin-6-amine hydrochloride (TC-2153), as a promising antidepressant of new generation. Lett Drug Design Discov 2017, 14, 974-984. [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, M., Singh. P., Xu. J., Lombroso. P.J., Kurup. P.K. Inhibition of striatal-enriched protein tyrosine phosphatise (STEP) activity reverses behavioural deficits in a rodent model of autism. Behav Brain Res 2020, 391, 112713. [CrossRef]

- Moskaliuk, V.S., Kozhemyakina, R.V., Bazovkina, D.V., Terenina, E., Khomenko, T.M., Volcho, K.P., Salakhutdinov, N.F., Kulikov, A.V., Naumenko, V.S., Kulikova, E. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2022, 147, 112667. [CrossRef]

- Moskaliuk, V.S., Kozhemyakina, R.V., Khomenko, T.M., Volcho, K.P., Salakhutdinov, N.F., Kulikov, A.V., Naumenko, V.S., Kulikova, E. On Associations between Fear-Induced Aggression, Bdnf Transcripts, and Serotonin Receptors in the Brains of Norway Rats: An Influence of Antiaggressive Drug TC-2153. Int. J. Mol. Sci, 2023, 24, 983. [CrossRef]

- Moskaliuk, V.S., Kozhemyakina, R.V., Khomenko, T.M., Volcho, K.P., Salakhutdinov, N.F., Kulikov, A.V., Naumenko, V.S., Kulikova, E. Key Enzymes of the Serotonergic System - Tryptophan Hydroxylase 2 and Monoamine Oxidase A – In the Brain of Rats Selectively Bred for a Reaction toward Humans: Effects of Benzopentathiepin TC-2153. Biochemistry (Moscow),2024, 89, 1109-1121. [CrossRef]

- Lipina, T.V., Roder, J.C. Disrupted-In-Schizophrenia-1 (DISC1) interactome and mental disorders: impact of mouse models. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2014, 45, 271-294. [CrossRef]

- Petrova, E.S., Gromova, A.V., Anisimenko, M.S., Ruban, L.A., Egorova, S.A., Petrovskaya, E.F., Amstislavskaya, T.G., Lipina, T.V. Maintenance of genetically modified mouse lines: input to the development of bio-collections in Russia. Laboratory animals for science, 2018, 2, 2-15. [CrossRef]

- Lipina, T.V., Beregovoy, N.A., Tkachenko, A.A., Petrova, E.S., Starostina, M.V., Zhou, Q., Li, S. Uncoupling DISC1 x D2R protein-protein interactions facilitates latent inhibition in Disc1-L100P animal models of schizophrenia and enhances synaptic plasticity via D2 receptors. Frontiers Synaptic Neuroscience 2018, 10, 31. [CrossRef]

- Rajarajan, P., Gil, S.E., Brennand, K.J., Akbarian, S. Spatial genome organization and cognition. Nat Rev Neurosci 2016, 17, 681-691. [CrossRef]

- Han, K., Jeng, E.E., Hess, G.T., Morgens, D.W., Li, A., Bassik, M.C. Synergistic drug combinations for cancer identified in a CRISPR screen for pairwise genetic interactions. Nat Biotechnol 2017, 35, 463-474. [CrossRef]

- Foley, C., Corvin, A., Nakagome, S. Genetics of schizophrenia: ready to translate? Curr Psychiatry Rep 2017, 19, 61. [CrossRef]

- Bradshaw, N.J., Porteous, D.J. DISC1-binding proteins in neural development, signaling and schizophrenia. Neuropharmacology 2012, 62, 1230-1241. [CrossRef]

- Thomson, P.A., Parla, J.S., McRae, A.F., Kramer, M., Ramakrishnan, K., Yao, J., Soares, D.C., McCarthy, S., Morris, S.W., Cardone, L., Cass, S., Ghiban, E., Hennah, W., Evans, K.L., Rebolini, D., Millar, J.K., Harris, S.E., Starr, J.M., MacIntyre, D.J., Generation Scotland, McIntosh, A.M., Watson, J.D., Deary, I.J., Visscher, P.M., Blackwood, D.H., McCombie, W.R., Porteous, D.J. 708 Common and 2010 rare DISC1 locus variants identified in 1542 subjects: analysis for association with psychiatric disorder and cognitive traits. Mol Psychiatry 2014, 19, 668-675. [CrossRef]

- Lipina, T.V., Zai, C., Hlousek, D., Roder, J.C., Wong, A.H. Maternal immune activation during gestation interacts with Disc1 point mutation to exacerbate schizophrenia-related behaviors in mice. J Neurosci 2013, 33, 7654-7666. [CrossRef]

- Lewis, D.A., Levitt, P. Schizophrenia as a disorder of neurodevelopment Annu Rev Neurosci 2002, 25, 409-432. [CrossRef]

- Lipina, T.V., Niwa, M., Jaaro-Peled, H., Fletcher, P.J., Seeman, P., Sawa, A,. Roder, J.C. Enhanced dopamine function in DISC1-L100P mutant mice: implications for schizophrenia. Genes Brain Behav 2010, 9, 777-789.

- Walsh, J., Desbonnet, L., Clarke, N., Waddington, J.L., O’Tuathaigh, C.M. Disruption of exploratory and habituation behavior in mice with mutation of DISC1: an ethologically based analysis. J Neurosci Res 2012, 90, 1445-1453. [CrossRef]

- Lubow, R.E. A short history of latent inhibition research. In the book “Latent inhibition: cognition, neuroscience and applications to schizophrenia”. 2010, p. 1-10; Eds R.E. Lubow and I. Weiner. Cambridge University Press. [CrossRef]

- Swerdlow, N.R., Braff, D.L., Taaid, N., Geyer, M.A. Assessing the validity of an animal model of deficient sensorimotor gating in schizophrenia patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994, 51, 139-154. [CrossRef]

- Braff, D., Geyer, M.A., Swerdlow, N.R. Sensorimotor gating and schizophrenia: human and animal model studies. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2001, 47, 181–188. [CrossRef]

- Weiner, I., Shadach, E., Tarrasch, R., Kidron, R., Feldon, J. The latent inhibition model of schizophrenia: further validation using the atypical neuroleptic, clozapine. Biol Psychiatry 1996, 40, 834-843. [CrossRef]

- Gray, N.S., Hemsley, D.R., Gray, J.A. Abolition of latent inhibition in acute, but not chronic, schizophrenics. Neurol PsychiatryBrain Res, 1992, 1, 83-89. [CrossRef]

- Geyer, M.A., Krebs-Thomson, K., Braff, D.L., Swerdlow, N.R. Pharmacological studies of prepulse inhibition models sensorimotor gating deficits in schizophrenia: a decade in review. Psychopharmacology, 2001, 156, 117-154. [CrossRef]

- Moser, P.C., Hitchcock, J.M., Lister, S., Moran, P.M. The pharmacology of latent inhibition as an animal model of schizophrenia. Brain Res Rev 2000, 33, 275-307. [CrossRef]

- Weiner, I., Feldon, J. The switching model of latent inhibition: an update of neural substrate. Beh Brain Res 1997, 88, 11-25. [CrossRef]

- Sukoff Rizzo, S.J., Lotarski, S.M., Stolyar, P., McNally, T., Arturi, C., Roos, M., Finely, J.E., Reinhart, V., Lanz, T.A. Behavioral characterization of striatal-enriched protein tyrosine phosphatase (STEP) knockout mice. Genes Brain Behav 2014, 13, 643-652. [CrossRef]

- Fitzpatrick, C.J., Lombroso, P.J. The role of striatal-enriched protein tyrosine phosphatase (STEP) in cognition. Front Neuroanatomy 2011, 5, 47. [CrossRef]

- 55. Malavasi, E.L.V., Economides, K.D., Grunewald, E., Makedonopoulou, P., Gautier, P., Mackie, S., Murphy, L.C., Murdoch, H., Crummie, D., Ogawa, F., McCartney, D.L., O’Sullivan, S.T., Burr, K., Torrance, H.S., Phillips, J., Bonneau, M., Anderson S.M., Perry, P., Pearson, M., Costantinidies, C., Davidson-Smith, H., Kabiri, M., Duff, B., Johnstone, M., Polites, H.G., Lawrie, S.M., Blackwood, D.H., Semple, C.A., Evans, K.L., Didier, M., Chandran, S., McIntosh, A.M., Price, D.J., Houslay, M.D., Porteous, D.J., Millar, J.K. DISC1 regulates N-methyl-D-asparate receptor dynamics: abnormalities induced by a Disc1 mutation modelling a translocation linked to major mental illness. Transl Psychiatry 2018, 8, 184. [CrossRef]

- Cui, L., Sun, W., Yu, M., Li, N., Guo, L., Gu, H., Zhou, Y. Disrupted-in-schizophrenia1 (DISC1) L100P mutation alters synaptic transmission and plasticity in the hippocampus and causes recognition memory deficits. Mol Brain 2016, 9, 89. [CrossRef]

| Group | WT | Disc1-L100P |

|---|---|---|

| Vehicle (n = 6-8) | 159.8 ± 34.9 | 90.0 ± 3.1 ### |

| TC-2153 (n = 6-8) | 132.4 ± 27.7 | 91.2 ± 5.7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).