Submitted:

18 August 2025

Posted:

19 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

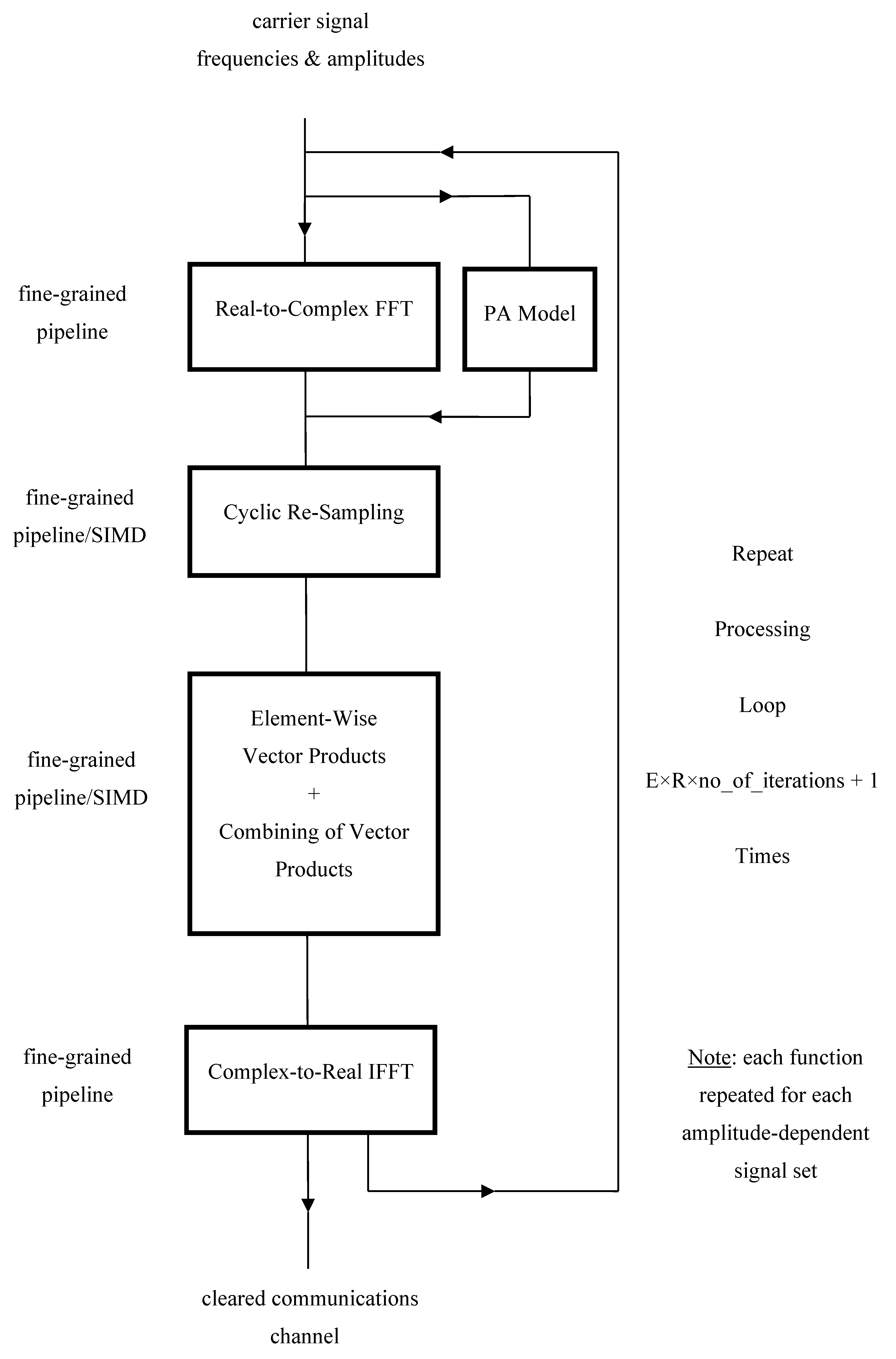

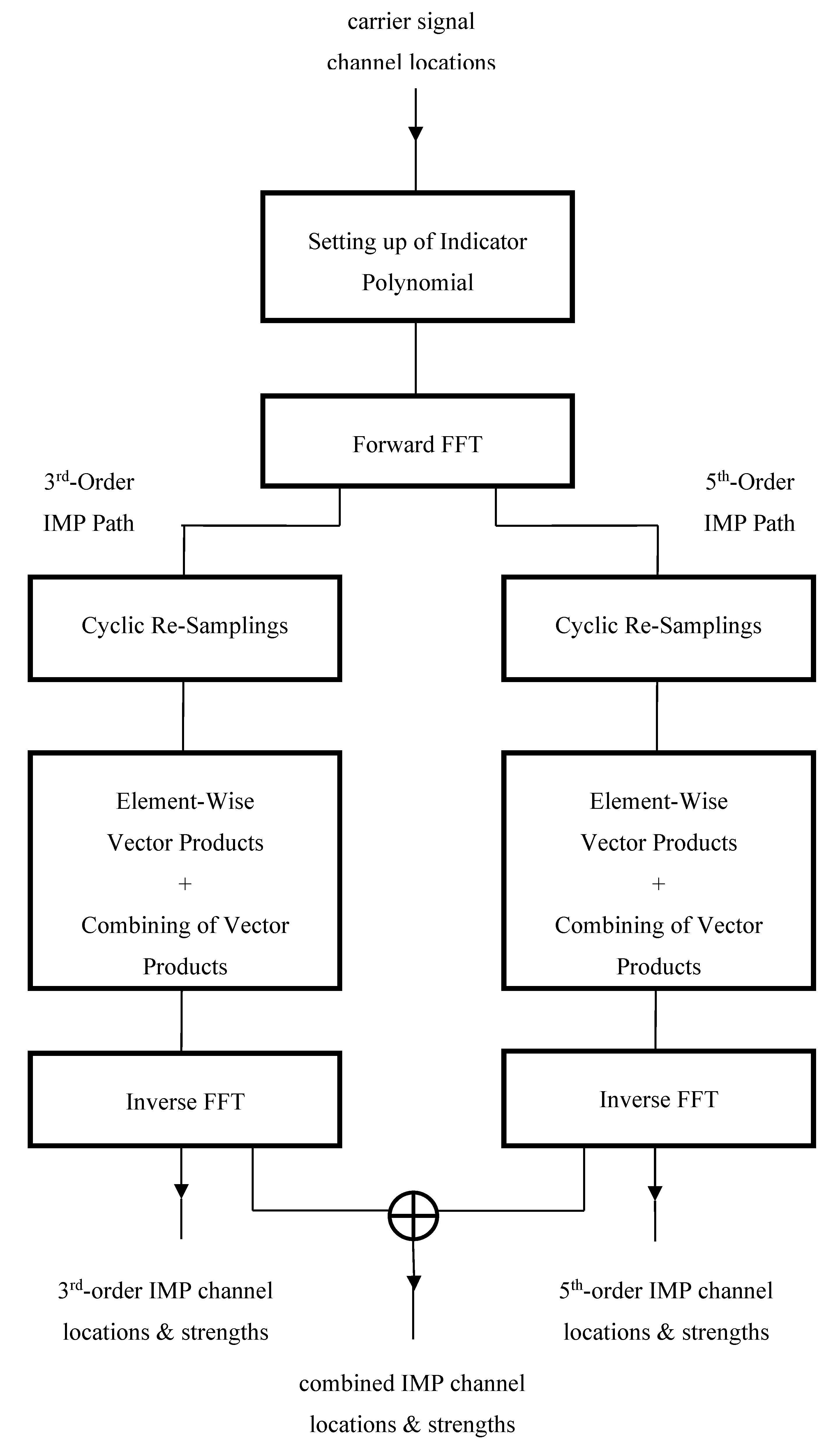

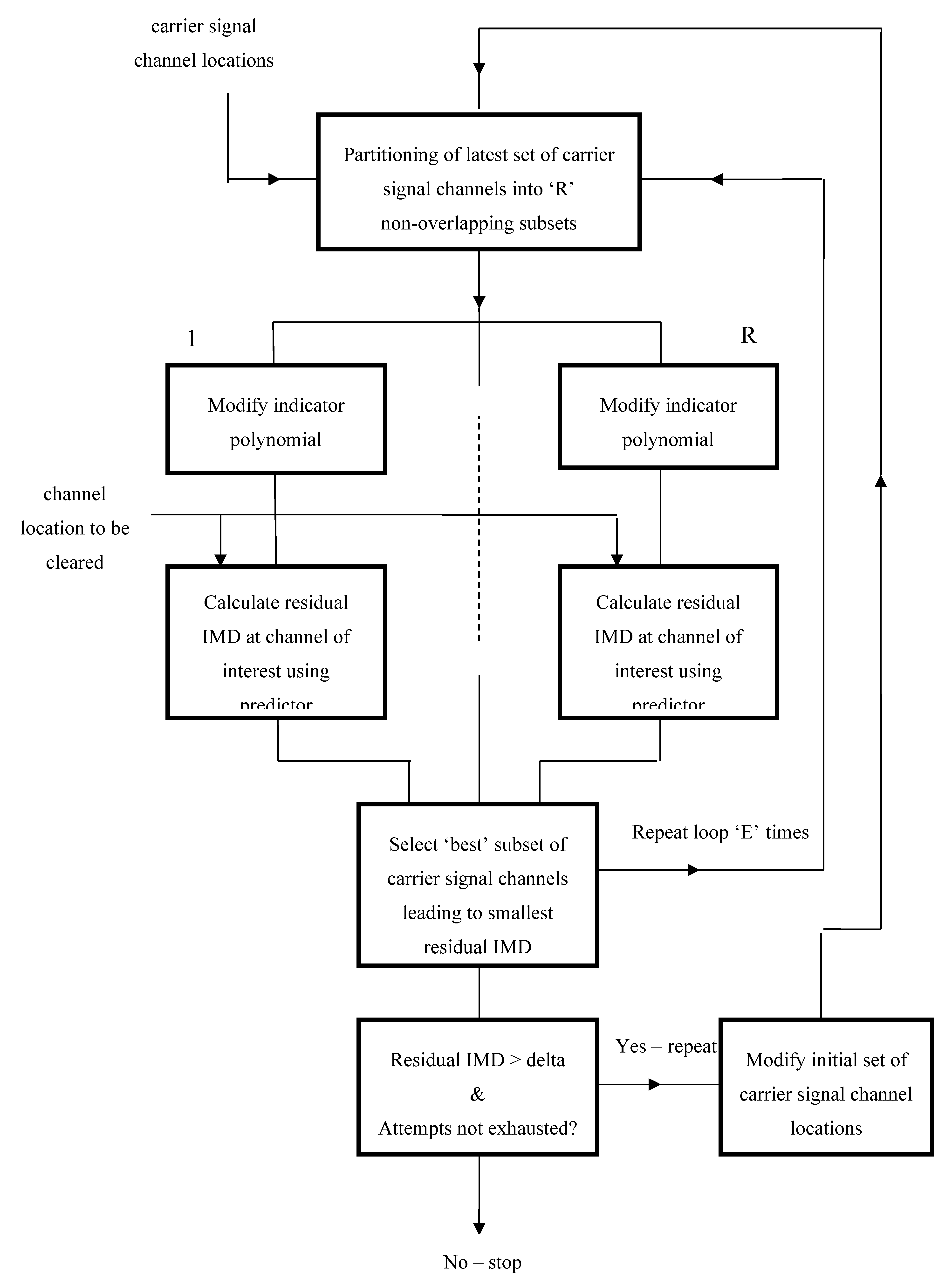

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Polynomial Modelling of Non-Linear PA Behaviour

3. Catering for More Sophisticated Signal Types

3.1. Arbitrary Signal Bandwidths

3.2. Arbitrary Signal Powers – Two Amplitude Levels

3.3. Arbitrary Signal Powers – Three Amplitude Levels

3.4. Discussion

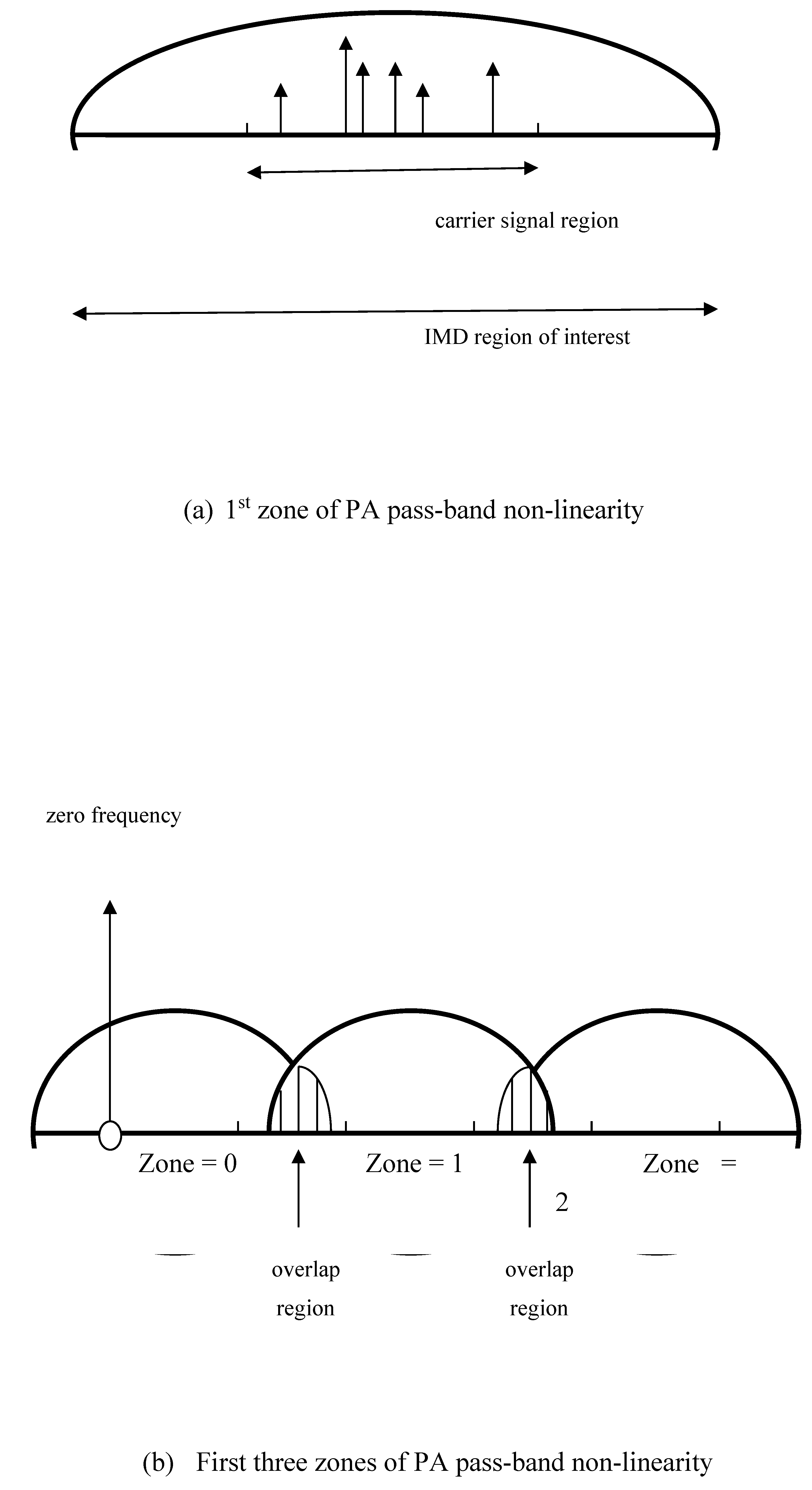

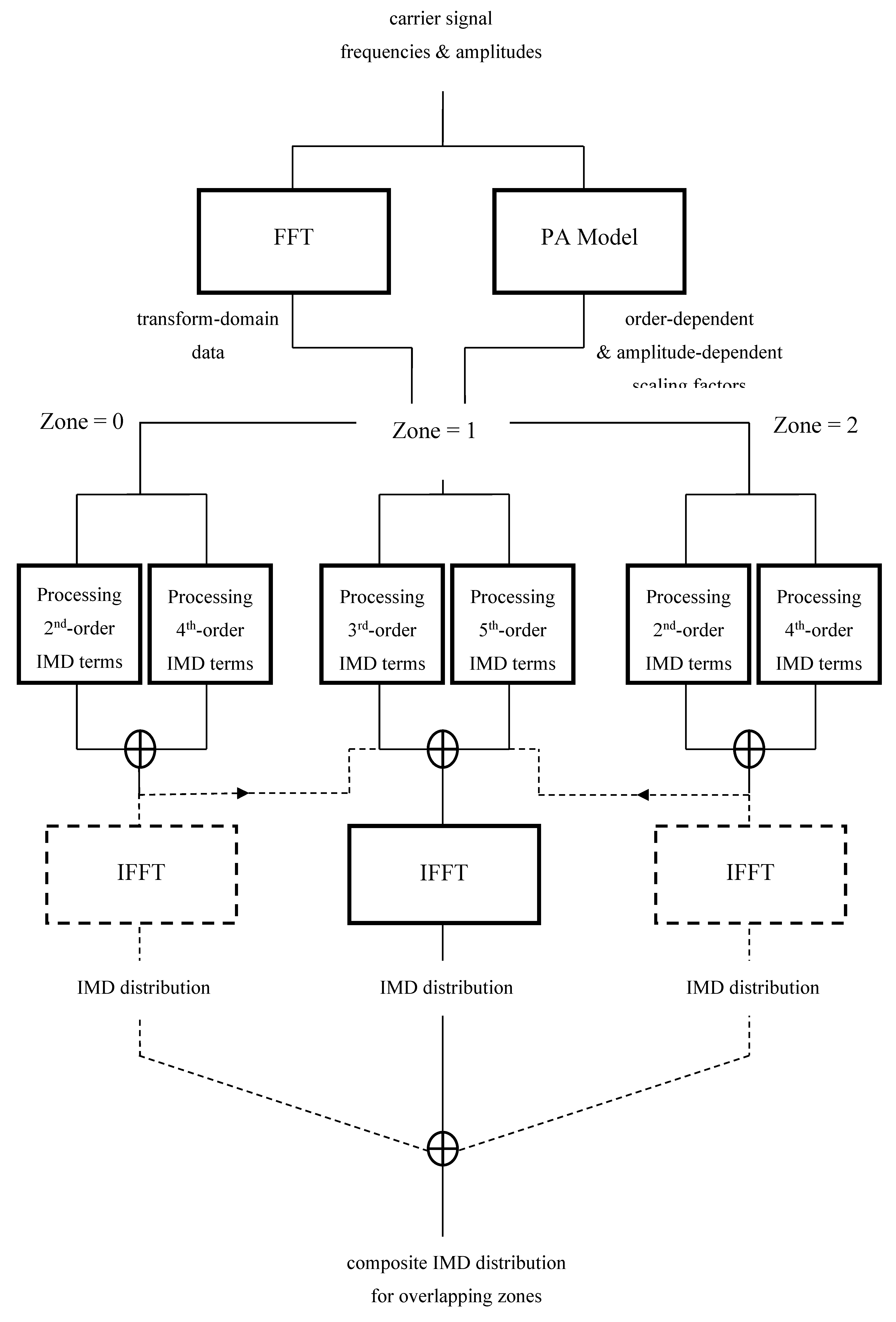

4. Catering for Multiple Zones of Distortion

5. Complexity Issues

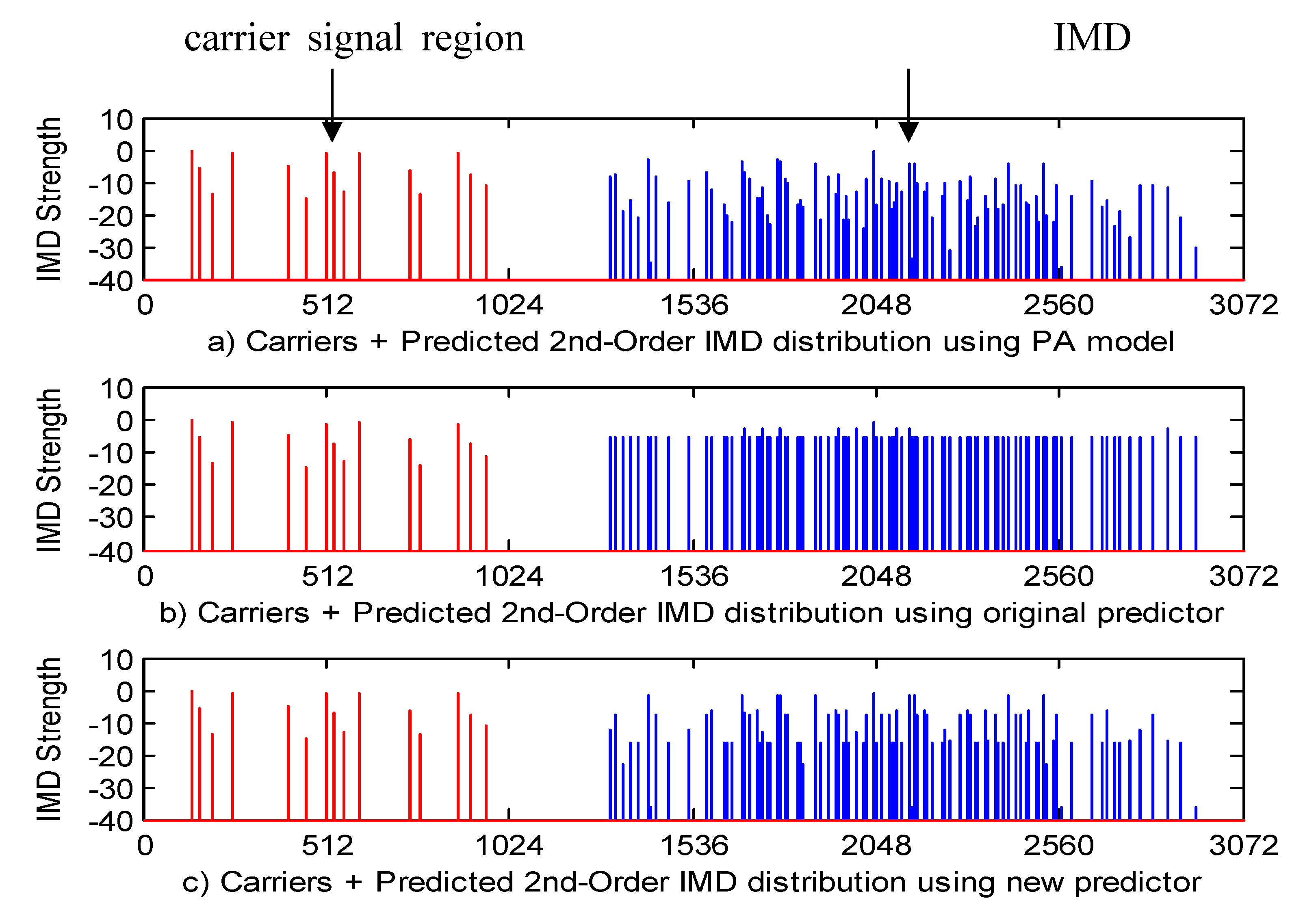

6. Simulation Results

7. Summary and Conclusions

Note

Appendix – PA Model Properties

References

- Rappaport, T.S.: “Wireless Communications: Principles and Practice” (Prentice Hall PTR, Upper Saddle River, N.J., 1999).

- Green, D.C.: “Radio Communication” (Longman, 2nd edition, 2000).

- Jones, K.J.: “Design of Low-Complexity Scheme for Maintaining Distortion-Free Multi-Carrier Communications”, IET Signal Processing, December 2013.

- Baruffa, G., and Reali, G.: “A Fast Algorithm to Find Generic Odd and Even Order Intermodulation Products”, IEEE Trans. on Wireless Comms., 2007, 6, (10), pp. 3749-3759. [CrossRef]

- Blahut, R.: “Fast Algorithms for Digital Signal Processing” (Addison-Wesley, 1985).

- Chu, E., and George, A.: “Inside the FFT Black Box” (CRC Press, Boca Raton, Fl., 2000).

- Blachman, N.M.: “Detectors, Bandpass Non-Linearities and their Optimization: Inversion of the Chebyshev Transform”, IEEE Trans. on Inf. Theory, 1971, 17, pp. 398-404.

- Qian, H., and Zhou, G.T.: “A Neural Network Pre-distorter for Nonlinear Power Amplifiers with Memory”, IEEE 10th Digital Signal Processing Workshop, 2002, pp. 312-316.

- Goldberg, D.E.: “Genetic Algorithms in Search, Optimization and Machine Learning” (Addison-Wesley, 1989).

- Oppenheim, A.V., and Schafer, R.W.: “Discrete-Time Signal Processing” (Englewood Cliffs, N.J., 1989).

- Akl, S.G.: “The Design and Analysis of Parallel Algorithms” (Prentice-Hall, Upper Saddle River, N.J., 1989).

- Cormen, T.H., Leiserson, C.E., and Rivest, R.L.: “Introduction to Algorithms” (MIT Press, McGraw-Hill, 2000).

- Silva, V., and Perdigao, F.: “Generalising the Simultaneous Computation of the DFTs of Two Real Sequences using a Single N-point DFT”, Signal Processing, 2002, 82, pp. 503-505. [CrossRef]

- Bracewell, R.N.: “The Hartley Transform” (Oxford University Press, New York, 1986).

- Jones, K.J.: “The Regularized Fast Hartley Transform: Low-Complexity Parallel Computation of FHT in One and Multiple Dimensions”, (Springer, 2nd Edition, 2022).

| Iteration No | Measured IMD for Original IMD Prediction & Channel Clearance Scheme: Orders: 2 to 5 Zones: 0 to 5 |

Measured IMD for New IMD Prediction & Channel Clearance Scheme: Orders: 2 to 5 Zones: 0 to 5 |

|---|---|---|

| start = 0 | 0.95 (0 dB) | 0.94 (0 dB) |

| 1 | 0.89 (-0.3 dB) | 0.31 (-4.8 dB) |

| 2 | 0.83 (-0.6 dB) | 0.26 (-5.6 dB) |

| 3 | 0.77 (-0.9 dB) | 0.21 (-6.5 dB) |

| 4 | 0.71 (-1.3 dB) | 0.19 (-6.9 dB) |

| 5 | 0.66 (-1.6 dB) | 0.15 (-8.0 dB) |

| 6 | 0.62 (-1.9 dB) | 0.12 (-8.9 dB) |

| 7 | 0.57 (-2.2 dB) | 0.09 (-10.2 dB) |

| 8 | 0.53 (-2.5 dB) | 0.08 (-10.7 dB) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).