1. Introduction

Video anomaly detection (VAD) plays a critical role in surveillance and safety applications, as it aims to detect abnormal events in visual scenes without explicit supervision. In real-world scenarios, collecting comprehensive annotated datasets for all possible anomalies is nearly impossible due to the diversity and rarity of such events. This challenge has motivated the development of unsupervised video anomaly detection (UVAD) techniques, which are trained only on normal data and identify anomalies based on deviations from learned patterns. Traditional UVAD approaches, such as ConvLSTM autoencoders or GANomaly, focus on reconstructing video frames and detecting anomalies through reconstruction errors. However, these methods often struggle to jointly capture spatial appearance and temporal motion dynamics, leading to limited generalization on complex datasets. Furthermore, many existing frameworks lack robustness in diverse domains such as violent crowd behavior, sports incidents, or urban surveillance. To address these limitations, we propose a unified GAN-based framework that integrates optical flow—computed by the UniMatch model—and RGB information through a dual-encoder generator. The generator includes a temporal GRU-attention bottleneck, and the discriminator is designed using a ConvLSTM-based structure with residual enhancement. In addition, we introduce a novel composite loss function, DASLoss, combining pixel-level, perceptual, temporal, and feature-based components for stable training and enhanced reconstruction fidelity. Compared to prior works such as ITAE and SVD-GAN, which focus on implicit reconstruction or frame differencing, our model explicitly fuses motion and appearance cues, enabling improved anomaly localization. Evaluations on three benchmarks—XD-Violence, Hockey Fight, and UCSD Ped2—demonstrate strong cross-domain generalization, with our model achieving an AP of 80.5 on XD-Violence, AUC of 0.92 on Hockey Fight, and AUC of 0.96 on Ped2. These results validate the effectiveness of our unsupervised paradigm across highly diverse and challenging video datasets.

2. Related Work

Existing approaches for unsupervised video anomaly detection (UVAD) can be broadly categorized into five main paradigms: reconstruction-based, motion-based, temporal modeling, generalization-focused, and multi-modal methods.

Reconstruction-based models identify anomalies by measuring the difference between input frames and their reconstructions, assuming that networks trained only on normal data will fail to accurately reconstruct abnormal inputs. For example, ConvLSTM-AE [

8] employs convolutional LSTM autoencoders to jointly capture spatial and temporal dependencies, while MemAE [

1] introduces a memory module that stores prototypical normal patterns, improving discrimination capability during reconstruction. Despite these advancements, such methods often rely on pixel-wise L2 losses, which tend to produce overly smooth outputs. As a result, they may inadvertently reconstruct anomalous regions with high fidelity [

2], leading to false negatives. Furthermore, pixel-level errors alone may not align with semantic anomalies, limiting the effectiveness of these methods in complex scenarios.

Motion-based approaches focus on dynamic aspects of scenes, often using future frame prediction or optical flow analysis to detect unexpected motion patterns. Liu et al. [

3] proposed a predictive ConvLSTM framework to generate future frames and identify anomalies based on large prediction errors. Although suitable for dynamic actions like running or fighting, these methods generally struggle with subtle or static anomalies (e.g., loitering), and are also sensitive to motion estimation noise. Optical flow–only methods, such as FlowNet [

9] and PWC-Net [

10], offer dense motion representations but often lack high-level scene understanding and struggle in cluttered or occluded environments. More recent optical flow methods like UniMatch [

16] improve accuracy and robustness through transformer-based attention mechanisms, yet still require integration with appearance features for holistic understanding.

Temporal modeling is essential for understanding sequential patterns in videos, as many anomalies involve sudden or progressive changes over time. Traditional recurrent models like RNNs, GRUs, and LSTMs have been widely used, but they typically assume fixed temporal dependencies and often fail to capture long-range dynamics or adapt to variable scene transitions. Nguyen et al. [

4] proposed a spatiotemporal autoencoder to address this, but their model lacked mechanisms to assign attention to informative frames, treating all inputs equally and introducing noise into the latent space. Recent works have explored temporal attention modules [

22] and Transformer architectures for anomaly detection, enabling more flexible temporal dependency modeling. However, their application in fully unsupervised settings remains limited due to high training complexity and data requirements.

Generalization and scalability remain persistent challenges in UVAD. Many early methods were developed and evaluated on constrained datasets like UCSD Ped2 [

18] or Avenue [

11], which contain repetitive patterns and simple backgrounds. While these datasets are useful for benchmarking, they often overestimate real-world applicability. Sultani et al. [

5] emphasized this issue through the introduction of the XD-Violence dataset, which includes diverse and unconstrained scenes such as crowded streets, sports, and violent behavior. Models trained on simpler datasets tend to overfit to specific environments and fail to generalize to new domains. Addressing this issue requires models that can learn robust representations invariant to background noise, scale changes, and camera viewpoints.

Multi-modal fusion has recently emerged as a promising direction to overcome the limitations of single-modality models. Inspired by supervised action recognition methods like I3D [

12] and ECO [

7], which combine RGB and optical flow streams, several UVAD models have attempted to integrate both appearance and motion cues. For example, MGAFlow [

13] introduced motion-guided attention for fusing optical flow with RGB features, yielding strong performance on challenging datasets. However, multi-modal fusion in the unsupervised setting remains underexplored due to architectural complexity and the absence of aligned supervision signals. Additionally, balancing the contribution of each modality, especially when one (e.g., optical flow) may be noisy or unreliable, poses another technical challenge. Nonetheless, the potential of cross-modal integration to enhance anomaly detection in real-world environments—where both spatial and temporal abnormalities occur simultaneously—makes it a critical area of ongoing research.

In summary, while substantial progress has been made in unsupervised video anomaly detection, existing methods still face limitations in generalizability, temporal reasoning, and modality fusion. Recent trends point toward unified architectures that combine appearance and motion signals, leverage attention mechanisms, and adopt dynamic decision strategies to better handle the complexities of real-world scenarios.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Overall Framework

The proposed framework is an unsupervised video anomaly detection model that utilizes both RGB frames and optical flow, integrated into a unified GAN-based architecture. The generator consists of two parallel encoders (for RGB and flow), a GRU-attention bottleneck, and a multi-stage decoder. The discriminator is designed using a ConvLSTM-based temporal module. The model is trained only on normal data(without label) and evaluated on both normal and abnormal video clips.

3.2. Input Preprocessing

To enable efficient and standardized data handling for both training and evaluation, raw video files are preprocessed into fixed-length tensors containing both RGB and optical flow information. Each sample consists of consecutive frames.

Given a directory of video files, each video is opened using OpenCV’s cv2.VideoCapture. If the number of available frames is fewer than 6, the video is skipped to ensure consistency in the model input shape. For valid samples, RGB frames are first extracted and resized to pixels.

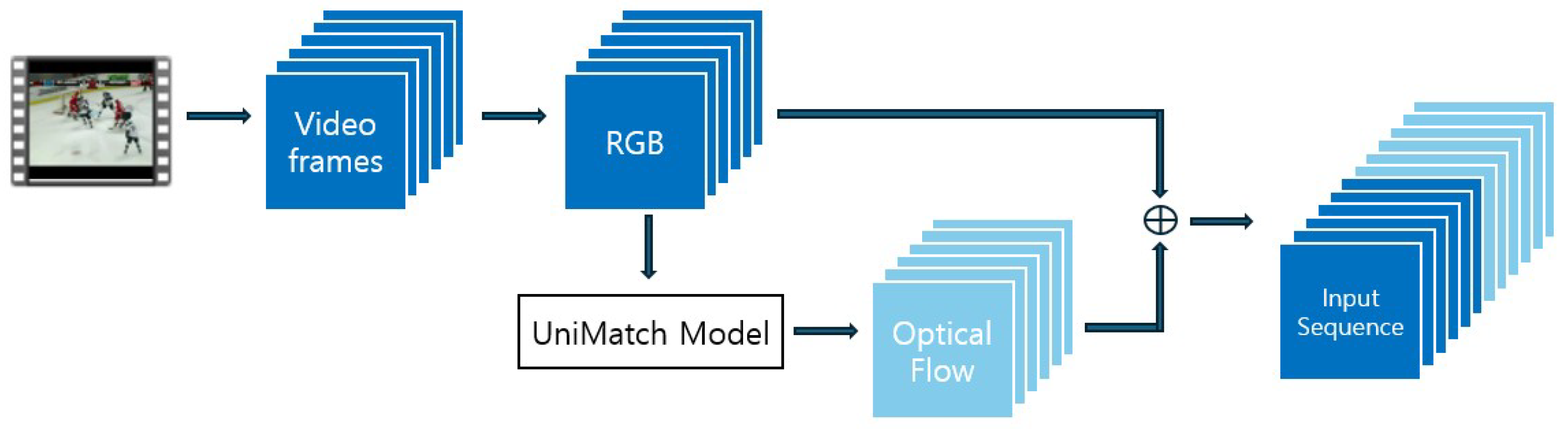

The overall preprocessing pipeline is illustrated in

Figure 4. As shown in the figure, RGB frames are first extracted from the video and then passed into the UniMatch [

16] model to compute the corresponding optical flow maps. UniMatch [

16] is a multi-scale optical flow estimator enhanced with Swin Transformer attention and bidirectional prediction. The resulting optical flow captures inter-frame motion dynamics critical for anomaly detection.

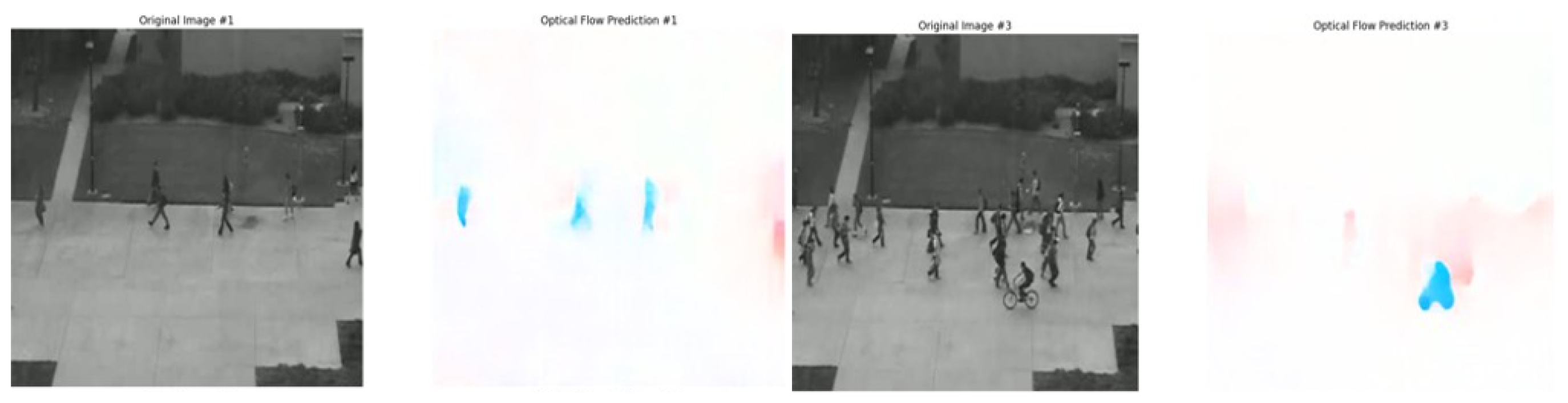

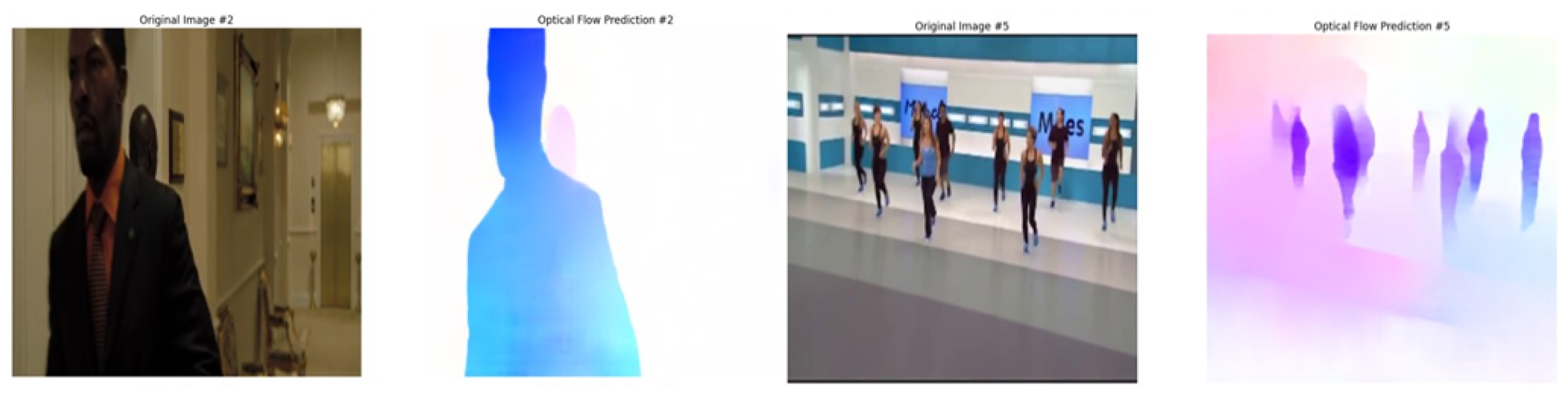

To demonstrate the effectiveness and clarity of the optical flow representations, we present sample visualizations from each of the three benchmark datasets used in our experiments.

Figure 1 displays an optical flow map extracted from the Hockey Fight dataset, which contains violent interactions in sports settings. The strong motion patterns between aggressive actions are captured in vivid color transitions, effectively distinguishing abnormal events.

Figure 2 illustrates a sample from the UCSD Ped2 dataset, which consists of surveillance footage of pedestrians on a walkway. Here, optical flow captures subtle anomalies such as bicycles or running individuals in a typically slow-moving scene.

Finally,

Figure 3 presents a frame from the XD-Violence dataset, which features complex and diverse real-world scenarios. The optical flow visualizes large-scale motion and chaotic dynamics across multiple actors and objects in uncontrolled environments.

Each flow map encodes motion direction and magnitude via hue and saturation, highlighting temporally salient regions. These visualizations confirm the ability of UniMatch[

16] to produce meaningful motion representations across varied datasets, facilitating robust spatiotemporal modeling in our proposed framework.

Figure 4.

Input preprocessing network.

Figure 4.

Input preprocessing network.

As depicted in

Figure 4, both RGB and optical flow sequences are then stacked to construct a unified representation. Each modality contributes 6 frames, resulting in a combined sequence of 12 frames. These are normalized to the

range using OpenCV’s

cv2.normalize with

cv2.NORM_MINMAX, and then stacked to form a tensor of shape

.

This tensor is converted to a PyTorch FloatTensor. A ground-truth label is assigned based on the directory name: samples in “Train” folders are considered normal (label 0), while those in “Test” folders are labeled as anomalous (label 1). Each sample is saved as a .pt file using torch.save(), containing:

frames: a 4D tensor of shape ,

label: a scalar indicating the normal (0) or abnormal (1) category.

During training and evaluation, a custom Dataset class is used to load these .pt files. The DataLoader provides efficient batch sampling, GPU memory transfer, and shuffling during training to facilitate scalable learning.

3.3. Handling and Evaluation of UCSD Ped2 Dataset

Unlike the other datasets, the UCSD Ped2 dataset is provided as frame-level image sequences rather than continuous video files. To maintain consistency with our video-based processing pipeline, we apply a stride-1 sliding window directly over the frame folders to extract 6-frame sequences. Each window of 6 consecutive frames

is used to compute 6 RGB frames and 6 corresponding optical flow maps using UniMatch [

16]. These are concatenated to form a tensor of shape

, consistent with our unified input format.

This preprocessing approach is applied uniformly for both training and testing. All training samples are extracted from normal clips only. During testing, sequences are sampled with stride 1 to ensure dense coverage and high-resolution anomaly localization. Anomaly scores are generated for the last frame of each 6-frame sequence.

Since the UCSD Ped2 dataset provides frame-level ground truth annotations, evaluation is conducted at the frame level. Specifically, the model’s predictions for frame in each window are compared against the corresponding ground truth. Frame-level AUC and F1-score are then computed over all predicted frames, enabling a fair and consistent evaluation aligned with the dataset’s annotation scheme.

3.4. Training Environments

The model is implemented using PyTorch and trained on an NVIDIA RTX 4090 GPU. The batch size is 4, and the input clip length is 12. We use the Adam optimizer with a learning rate of . Training is conducted for 400 epochs with early stopping based on validation AUC. Only normal clips are used for training; abnormal clips are reserved for testing.

3.5. Generator Architecture

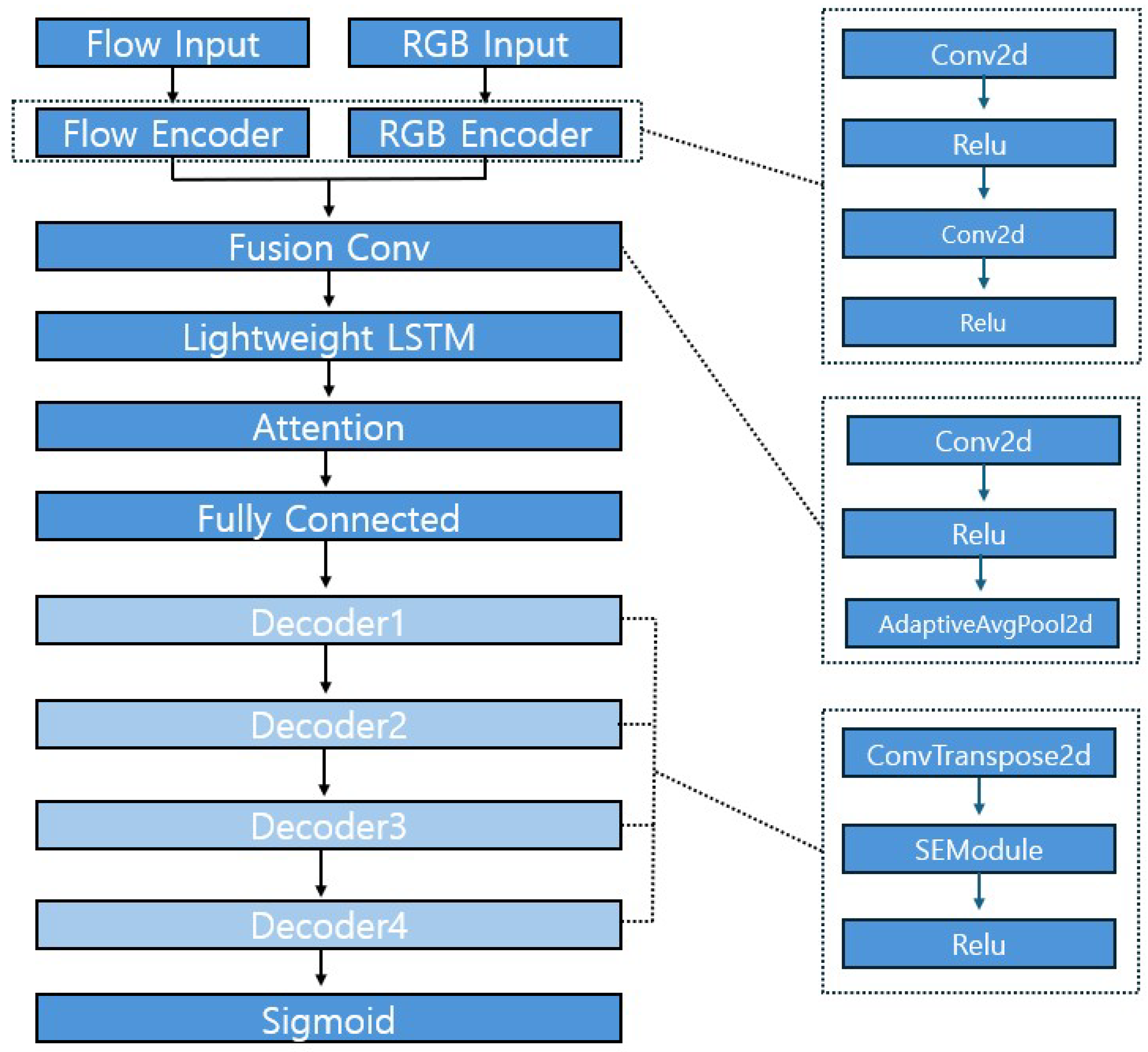

The overall structure of the generator is illustrated in

Figure 5. As shown in the diagram, the generator adopts a dual-stream encoder-decoder architecture designed to jointly process optical flow and RGB information for frame reconstruction.

The top portion of

Figure 5 shows the parallel input branches:

Flow Input and

RGB Input. Each stream is processed by its own encoder—Flow Encoder and RGB Encoder—both of which consist of two sequential convolutional layers with ReLU activations:

These encode low-level spatial features from each modality independently.

The outputs of the two encoders are then concatenated along the channel dimension, resulting in a 64-channel feature map. This fused representation is passed into the

Fusion Conv block (centered in

Figure 5), which is composed of:

This operation performs spatial compression while preserving semantic content across modalities.

To capture temporal dynamics across the input sequence, the fused features are reshaped into a sequence and processed by the

Lightweight LSTM module. The output is then passed through a temporal attention mechanism (labeled

Attention in

Figure 5), which enhances features that are temporally informative.

The attended features are flattened and projected via a fully connected layer to yield a bottleneck tensor of size , marked as Fully Connected in the figure. This serves as the initial input to the decoder stack.

The decoder (lower part of

Figure 5) consists of four hierarchical stages labeled

Decoder1 to

Decoder4. Each decoder stage includes a transposed convolution followed by an SE (Squeeze-and-Excitation) module and ReLU activation:

This design allows the network to restore spatial resolution while dynamically recalibrating channel-wise feature importance.

The final layer is a Sigmoid activation that constrains the output pixel values to the range , producing a reconstructed RGB frame of resolution .

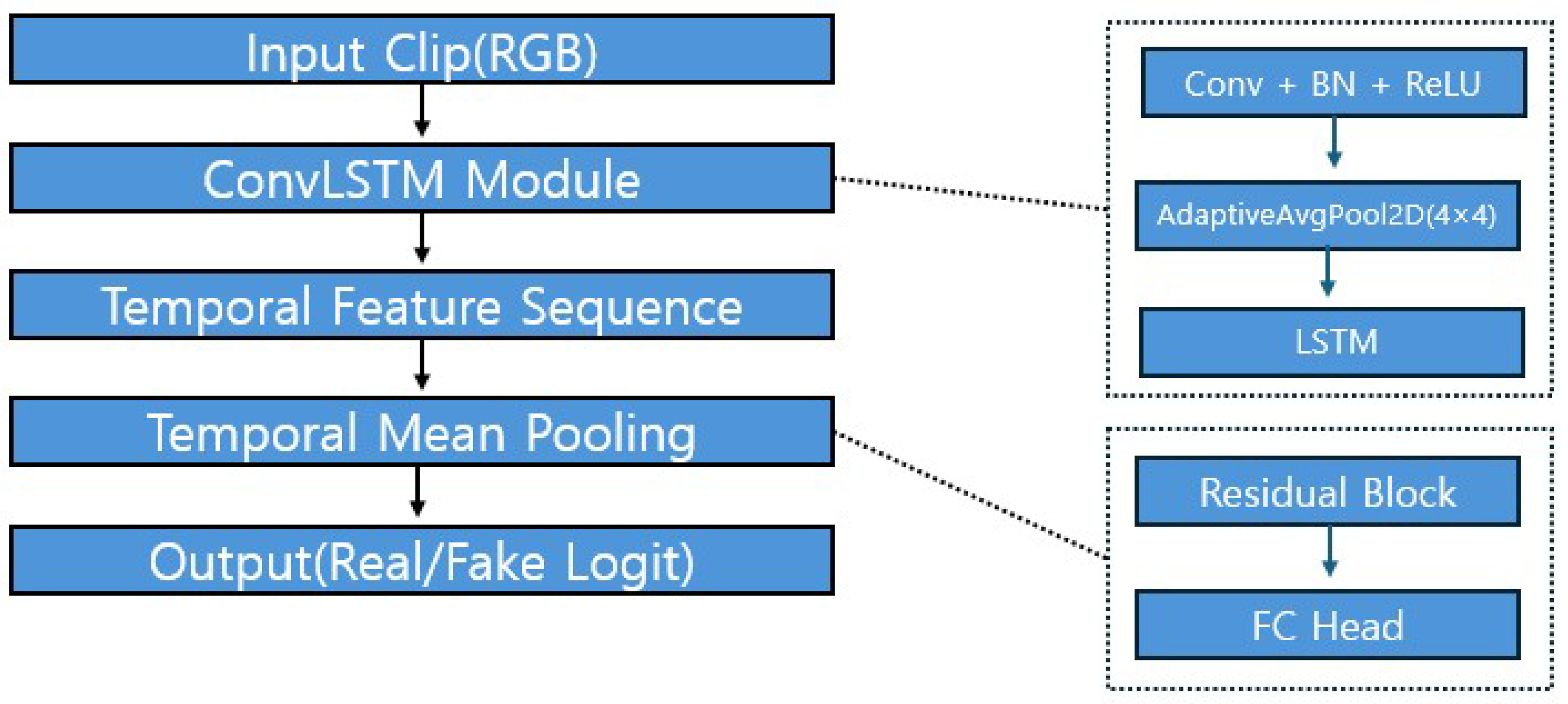

3.6. Discriminator Architecture

The overall structure of the discriminator is illustrated in

Figure 6. As shown in the figure, the discriminator is designed to evaluate the authenticity of RGB input clips by modeling both spatial and temporal dependencies through a ConvLSTM-based framework.

The process begins with an

Input Clip (RGB) of

T consecutive frames. These frames are passed through the

ConvLSTM Module, highlighted in the right panel of

Figure 6. This module consists of a convolutional layer followed by batch normalization and ReLU activation:

Afterward, an

AdaptiveAvgPool2d operation compresses spatial resolution to a fixed size of

, followed by an LSTM layer that models the temporal progression of features across frames. This produces a temporal feature sequence as depicted in the main diagram.

Next, temporal information is aggregated via Temporal Mean Pooling, which computes the average across all time steps, yielding a single feature vector per sequence.

The pooled feature is then passed into a

Residual Block + FC Head, also detailed on the right side of

Figure 6. The residual block includes two fully connected layers interleaved with

LayerNorm and

ReLU activations. The input is added back to the block output to preserve gradient flow:

This residual-enhanced feature is passed to the final

FC Head, which consists of two

LeakyReLU-activated fully connected layers followed by a final linear layer that outputs a single real/fake logit.

Importantly, intermediate feature sequences from the ConvLSTM module are also reused during generator training to compute feature-level consistency loss. This encourages the generator to produce outputs that align with real temporal semantics.

3.7. Loss Function

Generator Loss: DASLoss

The generator is trained using a composite objective called the

DASLoss, named after its three core components —

Discriminator feature alignment (

),

Appearance/perceptual consistency (

), and

Smoothness in the temporal domain (

). In addition, a pixel-level reconstruction loss (

) is included to preserve low-level fidelity.

where each term is defined as:

Pixel Reconstruction Loss () :

Mean squared error between ground-truth and reconstructed frames, widely used in autoencoder-based video anomaly detection [

8,

29].

Feature Matching Loss () :

L1 distance between intermediate discriminator features of real and generated frames, following the feature matching strategy from [

33].

Temporal Smoothness Loss () :

L2 norm of differences between consecutive reconstructed frames to encourage temporal consistency [

34,

35].

Perceptual Loss () :

L2 distance between VGG-16 features of real and reconstructed frames, based on perceptual loss from [

36].

Discriminator Loss

The discriminator is trained to distinguish real frames from generated ones using a least-squares GAN loss:

This least-squares formulation [

37] stabilizes training by preventing vanishing gradients. The generator and discriminator are updated alternately, with detached gradients used for the discriminator to avoid affecting the generator’s backpropagation.

3.8. Anomaly Scoring and Thresholding

During inference, the anomaly score

for each frame

t is computed as a weighted sum of pixel-wise reconstruction error and feature-space discrepancy from the discriminator:

where:

and are the ground-truth and reconstructed frames at time t.

denotes the discriminator’s final intermediate feature layer.

and are weighting coefficients for pixel and feature components.

This scoring strategy is inspired by combining pixel and feature reconstruction errors [

1,

2].

To convert scores into binary anomaly predictions, a dynamic threshold

is selected using Youden’s J-statistic [

38]:

This adaptive criterion ensures optimal separation between normal and abnormal samples and is applied per video or scene to account for distributional shifts, improving both F1 and recall compared to fixed thresholding.

4. Results

We evaluate the model’s generalizability and effectiveness on three benchmark datasets: XD-Violence [

19], Hockey Fight [

17], and UCSD Ped2 [

18]. These datasets include various real-world challenges such as complex motion, violent behavior, and subtle anomalies in surveillance scenes.

4.1. Evaluation Metrics and Setup

The performance is measured using widely adopted metrics: Average Precision (AP), Area Under the Curve (AUC), and F1-score. The model is trained using only normal data and tested on both normal and anomalous clips. Evaluation is conducted at the frame level using dynamic thresholding based on Youden’s J-statistic.

F1-Score. The F1-score is the harmonic mean of precision and recall, and is defined as:

Average Precision (AP). AP measures the area under the precision-recall curve and is defined as:

Area Under the Curve (AUC). AUC corresponds to the area under the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve and is defined as:

Table 1.

Summary of key hyperparameters used in the proposed model.

Table 1.

Summary of key hyperparameters used in the proposed model.

| Parameter |

Value / Description |

| Input frame size |

|

| Input sequence length |

6 frames (flow) + 6 frames (RGB) |

| Batch size |

4 |

| Optimizer |

Adam |

| Learning rate |

|

| Training epochs |

400 (with early stopping) |

|

1.0 |

|

0.1 |

|

0.1 |

|

0.01 |

4.2. Quantitative Results on Benchmark Datasets

As shown in

Table 2, our model achieves an AP of 80.5% on the XD-Violence dataset [

19], outperforming other unsupervised methods such as MGAFlow [

13], DiffusionAD, STPM [

23], MemAE [

1], and even the zero-shot Flashback model [

14]. This demonstrates our model’s robustness under real-world, unconstrained conditions.

Table 3 shows results on the Hockey Fight dataset [

17]. Our model achieves an AUC of 0.92 and F1-score of 0.85, surpassing prior unsupervised models such as AnoGAN [

2], GANomaly [

21], MemAE [

1], CFA-HLGAtt [

22], and ConvLSTM-AE [

8].

Finally,

Table 4 presents results on the UCSD Ped2 dataset [

18]. Our model reaches an AUC of 0.96, comparable to hybrid models such as CR-AE [

31] and Optical Flow + STC + GAN [

32], and just below memory-augmented AMC [

1].

5. Discussion

5.1. Performance Analysis Across Datasets

To assess the generalization and anomaly detection performance of our GAN-based framework, we evaluated it on three public benchmarks: Hockey Fight, UCSD Ped2, and XD-Violence. All experiments were conducted in a fully unsupervised setting, using only normal sequences for training and no anomaly labels at any training stage.

On the Hockey Fight dataset, our model achieved an AUC of 0.92 and an F1-score of 0.85. While the AUC surpasses prior unsupervised methods such as MemAE [

1], the F1-score is comparable to that of ConvLSTM-AE [

8] (0.86). This indicates that, although our model shows a stronger ability to rank anomalies correctly, its decision threshold performance in terms of precision–recall balance is on par with the best existing unsupervised baselines. The GRU-attention bottleneck was particularly helpful in capturing localized bursts of motion, while the optical flow estimated by UniMatch [

16] provided motion cues that complemented RGB appearance information.

On UCSD Ped2, our model obtained a high AUC of 0.96, showing robustness in static surveillance environments. The dual-encoder design successfully detected subtle spatial anomalies such as bicycles or small vehicles in pedestrian zones. While optical flow extraction for Ped2 is generally weak due to the camera’s distant viewpoint and the slow pace of normal pedestrians, anomalies in this dataset—bicycles and cars—exhibit much larger size and speed differences, resulting in clear motion patterns. As illustrated in

Figure 2, optical flow extraction for these anomalies remains effective. Furthermore, our DASLoss, with its perceptual and feature matching terms, helped maintain semantic-level reconstruction quality even when motion cues were limited. Together, these factors offset the shortcomings of optical flow in low-motion settings.

The most challenging benchmark, XD-Violence, includes diverse scenes and heterogeneous anomalies. Our model achieved an AP of 80.5, surpassing recent unsupervised models like MGAFlow [

13] (75.3) and Flashback [

14] (75.1). Notably, this was accomplished without using any labeled anomalies. The fusion of RGB and optical flow streams, combined with the multi-component DASLoss, was critical for capturing both semantic appearance and motion patterns. Despite the dataset’s complexity, performance was close to that of weakly-supervised methods such as WRAE [

15] (83.0), underscoring the effectiveness of our dual-stream design.

5.2. Architectural Contributions

The generator employs a dual-encoder design, processing RGB and optical flow separately to preserve modality-specific information before fusion. This enables balanced capture of fine spatial details from RGB and motion dynamics from optical flow. A GRU with attention pooling then focuses on the most informative temporal segments, enhancing detection of short, sudden anomalies. The SE-enhanced decoder further refines channel-wise responses, preserving small object details and clear boundaries.

The discriminator adopts a ConvLSTM-based structure to model sequence-level temporal dependencies, with residual fully connected layers improving adversarial stability. The proposed DASLoss combines pixel-level reconstruction, feature matching, perceptual, and temporal smoothness terms. The perceptual term improves global semantic coherence, while the temporal term reduces flicker and maintains motion continuity.

6. Conclusions and Future Work

In this paper, we presented a unified GAN-based framework for unsupervised video anomaly detection that leverages both RGB and optical flow inputs. By integrating a dual-stream encoder, temporal GRU-attention bottleneck, and ConvLSTM [

26]-based discriminator, our model effectively captures complex spatiotemporal patterns without relying on labeled anomalies. The proposed DASLoss further enhances training stability and reconstruction fidelity through a combination of pixel, feature, temporal, and perceptual consistency terms. Experimental results on three challenging benchmarks—Hockey Fight, UCSD Ped2, and XD-Violence—demonstrated that our approach achieves competitive or superior performance compared to state-of-the-art unsupervised methods, and even rivals some weakly-supervised models. These findings validate the robustness and generalizability of our unsupervised paradigm, making it a promising candidate for real-world video surveillance applications.

Despite its strong performance, our framework still has room for improvement in two key areas. First, the computational cost of optical flow estimation remains a challenge, particularly for real-time deployment. While UniMatch[

16] provides accurate motion representations, calculating optical flow for every frame pair is resource-intensive. To address this, we plan to explore lightweight or approximated motion representation techniques that reduce memory and processing overhead, such as using adaptive flow computation intervals or learning flow-free motion embeddings.

Second, although our model is currently designed for offline analysis, real-world applications often require low-latency responses. Therefore, we aim to extend our framework for real-time anomaly detection by redesigning the temporal components—such as the GRU bottleneck and ConvLSTM [

26]discriminator—to support online and incremental processing. These advancements will enhance the scalability and practicality of our approach, allowing it to operate effectively in dynamic and resource-constrained environments.

Finally, we observed that although our model performed well on the UCSD Ped2 dataset, it did not achieve the absolute highest accuracy among all benchmarks. This limitation is partly due to the dataset’s nature: slow pedestrian movement and distant viewpoints result in weak optical flow signals, making it harder for the model to exploit motion cues effectively. We believe that incorporating more sensitive or adaptive optical flow extraction methods—such as learning-based refinement or attention-driven flow amplification—could further enhance anomaly localization in such subtle scenarios. Future work will investigate these directions to boost detection performance in low-motion environments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.-H.K.; methodology, S.-H.K.; software, S.-H.K.; validation, S.-H.K. and H.-S.K.; formal analysis, S.-H.K. investigation, H.-S.K.; resources, H.-S.K.; data curation, S.-H.K.; writing—original draft preparation, S.-H.K.; writing—review and editing, S.-H.K. and H.-S.K.; visualization, S.-H.K. and H.-S.K.; supervision, H.-S.K.; project administration, H.-S.K.; funding acquisition, H.-S.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was partially supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF), funded by the Ministry of Education under Grant 2020R1I1A3A04037680, and partly by the Innovative Human Resource Development for Local Intellectualization program through the Institute of Information & Communications Technology Planning & Evaluation (IITP) grant funded by the Korea Government [Ministry of Science and ICT (MSIT)] (IITP-2025-RS-2020-II201462, 50%).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Gong, D.; Liu, L.; Le, V.; Saha, B.; Mansour, M.R.; Venkatesh, S.; van den Hengel, A. Memorizing Normality to Detect Anomaly: Memory-Augmented Deep Autoencoder for Unsupervised Anomaly Detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Seoul, Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 1705–1714.

- Sabokrou, M.; Khalooei, M.; Fayyaz, M.; Adeli, E. Adversarially Learned One-Class Classifier for Novelty Detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 3379–3388.

- Liu, W.; Luo, W.; Lian, D.; Gao, S. Future Frame Prediction for Anomaly Detection – A New Baseline. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 6536–6545.

- Nguyen, H.; Liu, V.; Prasad, S.; Tran, D. Anomaly Detection in Video Sequence with Appearance-Motion Correspondence. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision Workshops (ICCVW), Seoul, Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 1272–1281.

- Sultani, W.; Chen, C.; Shah, M. Real-World Anomaly Detection in Surveillance Videos. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 6479–6488.

- Tran, D.; Wang, H.; Torresani, L.; Ray, J.; LeCun, Y.; Paluri, M. A Closer Look at Spatiotemporal Convolutions for Action Recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 6450–6459.

- Zolfaghari, M.; Singh, K.; Brox, T. ECO: Efficient Convolutional Network for Online Video Understanding. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 695–712.

- Luo, W.; Liu, W.; Gao, S. A Revisit of Sparse Coding Based Anomaly Detection in Stacked RNN Framework. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 341–349.

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Fischer, P.; Ilg, E.; Hausser, P.; Hazirbas, C.; Golkov, V.; van der Smagt, P.; Cremers, D.; Brox, T. FlowNet: Learning Optical Flow with Convolutional Networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Santiago, Chile, 7–13 December 2015; pp. 2758–2766.

- Sun, D.; Yang, X.; Liu, M.Y.; Kautz, J. PWC-Net: CNNs for Optical Flow Using Pyramid, Warping, and Cost Volume. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 8934–8943.

- Lu, C.; Shi, J.; Jia, J. Abnormal Event Detection at 150 FPS in MATLAB. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Sydney, NSW, Australia, 1–8 December 2013; pp. 2720–2727.

- Carreira, J.; Zisserman, A. Quo Vadis, Action Recognition? A New Model and the Kinetics Dataset. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 6299–6308.

- Park, H.; Kim, T.; Oh, J.; Kim, C.; Kim, G. MGAFlow: Motion-Guided Attention Flow Network for Video Anomaly Detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 18–22 June 2023; pp. 12861–12870.

- Georgescu, M.I.; Ionescu, R.T.; Popescu, M.; Khan, F.S.; Shao, L. Anomaly Detection in Video via Self-Supervised and Multi-Task Learning. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Virtual, 19–25 June 2021; pp. 14366–14375.

- Cho, M.; Kim, M.; Shin, Y. Weakly-Supervised Video Anomaly Detection via Robust Temporal Feature Alignment. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 18–22 June 2023; pp. 14213–14222.

- Xu, H.; Zhang, J.; Cai, J.; Rezatofighi, H.; Yu, F.; Tao, D.; Geiger, A. Unifying Flow, Stereo and Depth Estimation. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence (TPAMI), 2023. doi:10.1109/TPAMI.2023.3242203.

- Nievas, E.B.; Suarez, O.D.; Garcia, G.B.; Sukthankar, R. Violence detection in video using computer vision techniques. In Computer Analysis of Images and Patterns (CAIP), Seville, Spain, 29–31 August 2011; pp. 332–339.

- Mahadevan, V.; Li, W.; Bhalodia, V.; Vasconcelos, N. Anomaly detection in crowded scenes. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–18 June 2010; pp. 1975–1981.

- Wu, J.; Zhang, W.; Gao, C.; He, Z.; Jiao, J. Not only look, but also listen: Learning multimodal violence detection under weak supervision. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Glasgow, UK, 23–28 August 2020; pp. 322–339.

- Yang, Z.; Wu, Y.; Huang, Q.; Loy, C.C. DiffusionAD: Masked Spatiotemporal Autoencoding for Video Anomaly Detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 18–22 June 2023; pp. 3055–3064.

- Akçay, S.; Atapour-Abarghouei, A.; Breckon, T.P. Ganomaly: Semi-supervised Anomaly Detection via Adversarial Training. In Proceedings of the Asian Conference on Computer Vision (ACCV), Perth, Australia, 2–6 December 2018; pp. 622–637.

- Tian, Y.; Chen, X.; Wu, J.; Zha, Z.J.; Zhang, Z. Cross-feature Attention with Hierarchical Local-Global Modeling for Video Anomaly Detection. In Proceedings of the 29th ACM International Conference on Multimedia (MM), Virtual Event, 20–24 October 2021; pp. 1126–1135.

- Zhou, W.; Wu, W.; Lin, W. Spatio-temporal Predictive Memory Network for Video Anomaly Detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Montreal, QC, Canada, 11–17 October 2021; pp. 13929–13938.

- Yu, P.; Lu, H.; Li, L. STADNet: Spatial-Temporal-Appearance Distribution-Aware Network for Video Anomaly Detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 19–24 June 2022; pp. 20833–20842.

- Tang, Y.; Wang, L.; Liu, L.; Li, B.; Wu, Y.; Gao, J. Integrating Multimodal and Temporal Perception for Dynamic Event Understanding. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Glasgow, UK, 23–28 August 2020; pp. 312–328.

- Shi, X.; Chen, Z.; Wang, H.; Yeung, D.Y.; Wong, W.K.; Woo, W.C. Convolutional LSTM Network: A Machine Learning Approach for Precipitation Nowcasting. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), Montreal, QC, Canada, 7–12 December 2015; pp. 802–810.

- Tang, Y.; Wu, J.; Song, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, W. RTFM: A General Framework for Video Anomaly Detection via Robust Temporal Feature Magnitude Learning. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Montreal, QC, Canada, 11–17 October 2021; pp. 15804–15813.

- Kim, J.; Grauman, K. Observe locally, infer globally: A space-time MRF for detecting abnormal activities with incremental updates. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Miami, FL, USA, 20–25 June 2009; pp. 2921–2928.

- Hasan, M.; Choi, J.; Neumann, J.; Roy-Chowdhury, A.K.; Davis, L.S. Learning temporal regularity in video sequences. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 26 June–1 July 2016; pp. 733–742.

- Ji, S.; Xu, W.; Yang, M.; Yu, K. 3D convolutional neural networks for human action recognition. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, 2013, 35(1), 221–231.

- Ionescu, R.T.; Smeureanu, S.; Alexe, B.; Popescu, M. Object-centric auto-encoders and dummy anomalies for abnormal event detection in video. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 7842–7851.

- Ravanbakhsh, M.; Nabi, M.; Sangineto, E.; Sebe, N. Plug-and-play CNN for crowd motion analysis: An application in abnormal event detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), Lake Tahoe, NV, USA, 12–15 March 2018; pp. 1689–1698.

- Salimans, T.; Goodfellow, I.; Zaremba, W.; Cheung, V.; Radford, A.; Chen, X. Improved techniques for training GANs. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), Barcelona, Spain, 5–10 December 2016; pp. 2234–2242.

- Mathieu, M.; Couprie, C.; LeCun, Y. Deep multi-scale video prediction beyond mean square error. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), San Juan, Puerto Rico, 2–4 May 2016.

- Villegas, R.; Yang, J.; Hong, S.; Lin, X.; Lee, H. Decomposing motion and content for natural video sequence prediction. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), Toulon, France, 24–26 April 2017.

- Johnson, J.; Alahi, A.; Fei-Fei, L. Perceptual losses for real-time style transfer and super-resolution. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 11–14 October 2016; pp. 694–711.

- Mao, X.; Li, Q.; Xie, H.; Lau, R.Y.; Wang, Z.; Smolley, S.P. Least squares generative adversarial networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 2794–2802.

- Youden, W.J. Index for rating diagnostic tests. Cancer, 1950, 3(1), 32–35.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).