Introduction

Prostate cancer (PCa) is a leading male malignancy globally and the second most diagnosed cancer in men, after lung cancer, with an estimated 1.4 million new cases and 375,000 deaths worldwide reported in 2020 [

1]. The burden of PCa is disproportionately high in populations of African descent, including West African countries such as Ghana, where prostate cancer is the most prevalent male cancer and among the top causes of cancer-related mortality [

2,

3]. Unlike Western populations, where PSA screening and early detection protocols have reduced mortality, late presentation remains a major challenge in sub-Saharan Africa, associated with aggressive tumour biology and limited healthcare resources.

Several well-established risk factors influence prostate cancer development, including advanced age, family history, ethnicity, hormonal environment, and lifestyle factors such as diet and physical activity [

4]. Of particular importance is the genetic predisposition observed among men of African ancestry, which may partially explain increased incidence and aggressive tumour phenotypes reported in Ghanaian cohorts [

18].

Bone metastasis is the predominant site of distant spread in advanced prostate cancer, commonly resulting in skeletal-related events that contribute significantly to morbidity and decreased quality of life [

5]. The use of Technitium-99m methylene diphosphonate (Tc-99m MDP) bone scintigraphy has been the standard imaging technique for detection of skeletal metastases for several decades due to its wide availability, relatively low cost, and high sensitivity [

5]. Early identification of bone involvement is critical for staging, prognostication, and optimization of treatment strategies.

Despite its importance, data describing the clinicopathologic features and metastatic burden of prostate cancer patients who undergo bone scanning in Ghana remain limited. This study aims to fill this gap by describing the sociodemographic characteristics, clinical presentation, pathological grading, and bone scan findings of prostate cancer patients at a tertiary nuclear medicine center in Ghana to better understand disease patterns and inform improved cancer control strategies.

Aim

To characterize the sociodemographic and clinicopathologic features of prostate cancer patients undergoing Technetium-99 bone scan and identify predictors of bone metastasis.

The Objectives of the study were to: To analyse demographic characteristics, including age, ethnicity, education, and occupation, describe clinicopathologic parameters, including PSA, ISUP grade, prostate volume, and clinical staging, and investigate associations between sociodemographic characteristics and clinicopathological features.

Materials & Methods

Study Design and Setting

This cross-sectional study retrospectively analysed clinical and imaging data collected from medical records of patients referred for bone scintigraphy at the Nuclear Medicine Department of Korle-Bu Teaching Hospital, Accra, Ghana, over 12 months (January to December 2018). The hospital serves as a tertiary referral centre for oncology and nuclear medicine services nationally.

Study Population

Inclusion criteria consisted of male patients with histologically confirmed prostate adenocarcinoma who underwent Technetium-99m MDP bone scans during the study period. Patients without complete clinical or imaging data were excluded.

Data Collection and Variables

Demographic data extracted included age, ethnicity, education level, and occupation. Clinical data collected included presenting symptoms, serum PSA levels at diagnosis or referral, clinical TNM staging according to AJCC guidelines, Gleason histologic scores from biopsy or surgical specimens, and the presence or absence of bone metastases on bone scans.

Bone scans were interpreted by experienced nuclear medicine physicians. Scan results were classified as positive or negative for bone metastases based on abnormally increased tracer uptake patterns consistent with metastatic disease.

Imaging Technique

All bone scans were performed using standard protocols with Tc-99m MDP, acquiring whole-body images 3–4 hours post-injection. Scans were interpreted by experienced nuclear medicine physicians, classifying metastasis as positive, equivocal, or negative.

Conceptual Framework

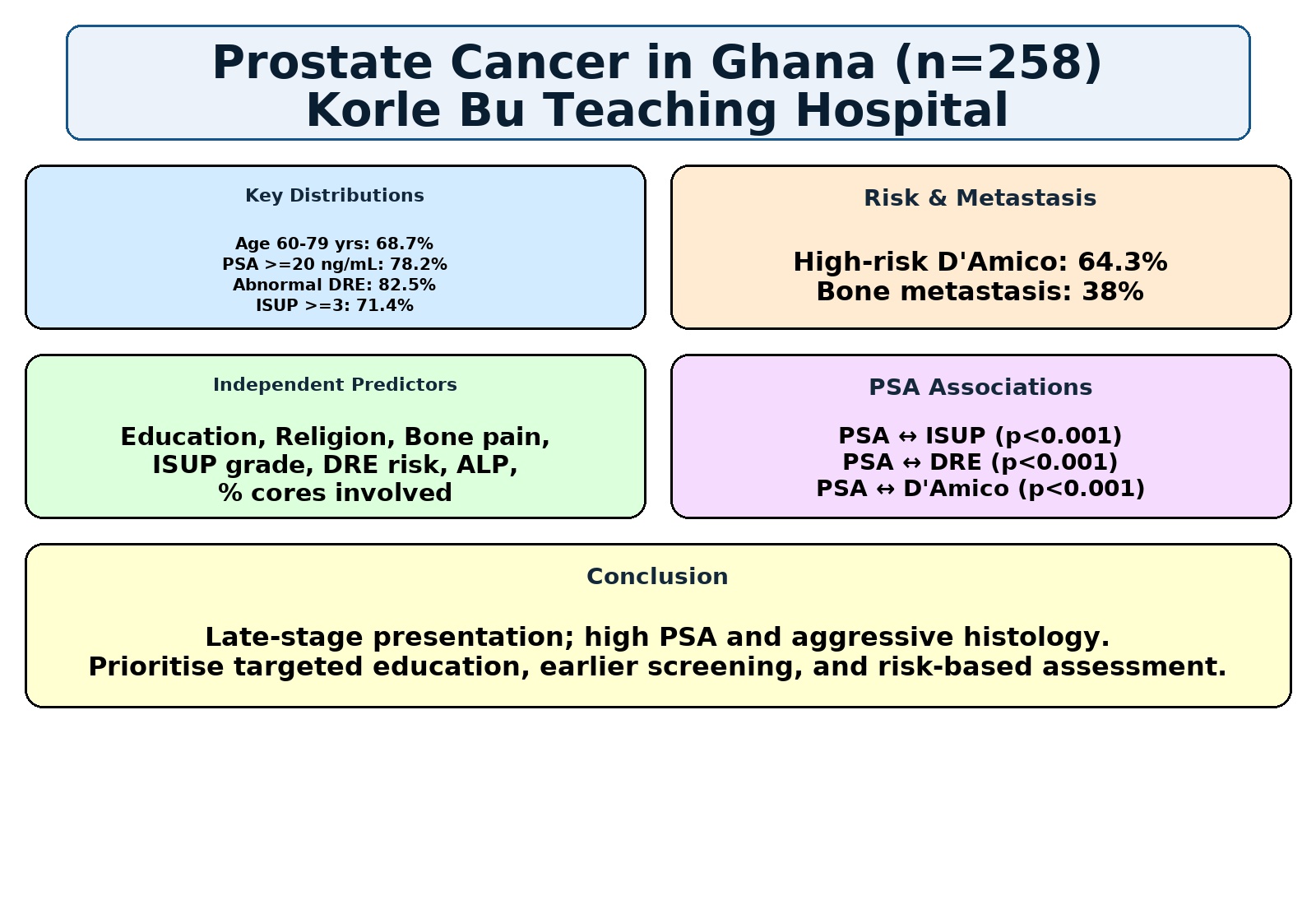

The conceptual framework of this study is grounded in understanding the multifactorial interplay between sociodemographic factors, clinical-pathological characteristics, and metastatic progression in prostate cancer (PCa) patients within the Ghanaian healthcare context. The framework elucidates how these domains collectively influence disease presentation, diagnostic evaluation through bone scintigraphy, and eventual clinical outcomes (

Figure 1).

Prostate cancer development and progression are influenced by inherent biological factors—including genetic predisposition, tumour biology, and hormonal milieu—and extrinsic factors such as environmental exposures, lifestyle, and sociodemographic determinants. Age remains the most significant non-modifiable risk factor, with increasing incidence seen in older men due to the accumulation of genetic mutations and hormonal changes [

1,

4]. Ethnicity, particularly African ancestry, is associated with higher incidence, aggressive tumour phenotypes, and poorer prognosis, likely driven by distinct genetic variants and socio-environmental disparities [

2,

18].

Sociodemographic factors such as education level, occupation, and ethnicity influence health-seeking behaviours, awareness, and access to health services [

15]. For instance, higher educational attainment can improve knowledge of prostate cancer symptoms and screening options, facilitating earlier diagnosis; however, systemic barriers such as healthcare accessibility and cultural perceptions may modulate this effect [

15,

16]. Occupational status and socioeconomic position further impact the timeliness of presentation and adherence to follow-up care.

Clinicopathological features constitute intermediate variables mediating disease aggressiveness and metastatic potential. Serum prostate specific antigen (PSA) is a sensitive biomarker reflecting tumour burden and is integral to screening and monitoring [

10]. Histopathological grading via Gleason score provides prognostic insight into tumour differentiation and likelihood of progression [

9]. Clinical tumour staging captures local and regional disease extent, often reflecting delays in diagnosis in resource-limited settings [

4].

Bone metastases represent a critical endpoint of prostate cancer progression, with significant implications for morbidity and mortality [

5]. The presence of skeletal metastases detected by Technetium-99m methylene diphosphonate (Tc-99m MDP) bone scans informs prognosis and therapeutic decision-making. The likelihood of bone metastasis is modulated by PSA levels, Gleason score, and clinical stage, with elevated values correlating with increased metastatic risk [

10].

This framework thus posits a linkage pathway where sociodemographic factors affect early detection and disease presentation, which in turn determine clinicopathologic characteristics at diagnosis. These characteristics predict the presence and extent of bone metastasis detected via bone scintigraphy, ultimately influencing patient management and outcomes (

Figure 1).

Understanding these interrelationships provides insight into the observed pattern of advanced disease and high metastatic burden among Ghanaian prostate cancer patients. It further informs targeted public health interventions aimed at improving awareness, screening uptake, and early referral. Addressing the socio-environmental determinants alongside biological factors is crucial for reducing prostate cancer mortality in this context (

Figure 1).

Data Sources/Measurement

To reduce selection and misclassification bias, all records within the defined period and criteria were exhaustively reviewed. A uniform data extraction template was used. Independent reviewers performed cross-checking to validate the accuracy of the extraction.

Sample Size and Sampling

This was a census-based study of all eligible cases over the year from January to December 2018. No prior sample size calculation was conducted, as the aim was to obtain the full set of cases that meet the eligibility criteria.

Data Analysis/Statistical Methods

Descriptive statistics (means, medians, frequencies, proportions, percentages) were calculated to summarize demographic characteristics. This constituted the Socio-demographic analysis. Bivariate analyses to test associations, multivariate. Results were presented in tables and graphs to aid interpretation. All analyses were conducted in Stata-version 17. A 5% level of significance was used.

Ethical Approval

This study was reviewed and approved by the Ethical Review Committee of the Korle-Bu Teaching Hospital (Approval number: KBTH-IRB/00086/2018). Before data collection, written informed consent was obtained from the guardians of all participating children, ensuring that they fully understood the purpose, procedures, potential risks, and benefits of the study (Except for the part of the study that used retrospective data from hospital electronic records). All research activities were conducted in strict compliance with the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki regarding research involving human participants.

Results

Sociodemographic, Family History, and Lifestyle Factors

A total of 258 male patients met the inclusion criteria. The mean age was 68.18 years (SD ±8.3), ranging from 47 to 85 years, with the largest subgroup (42%) aged 60–69 years. The descriptive statistics for continuous variables are shown in

Table 1.

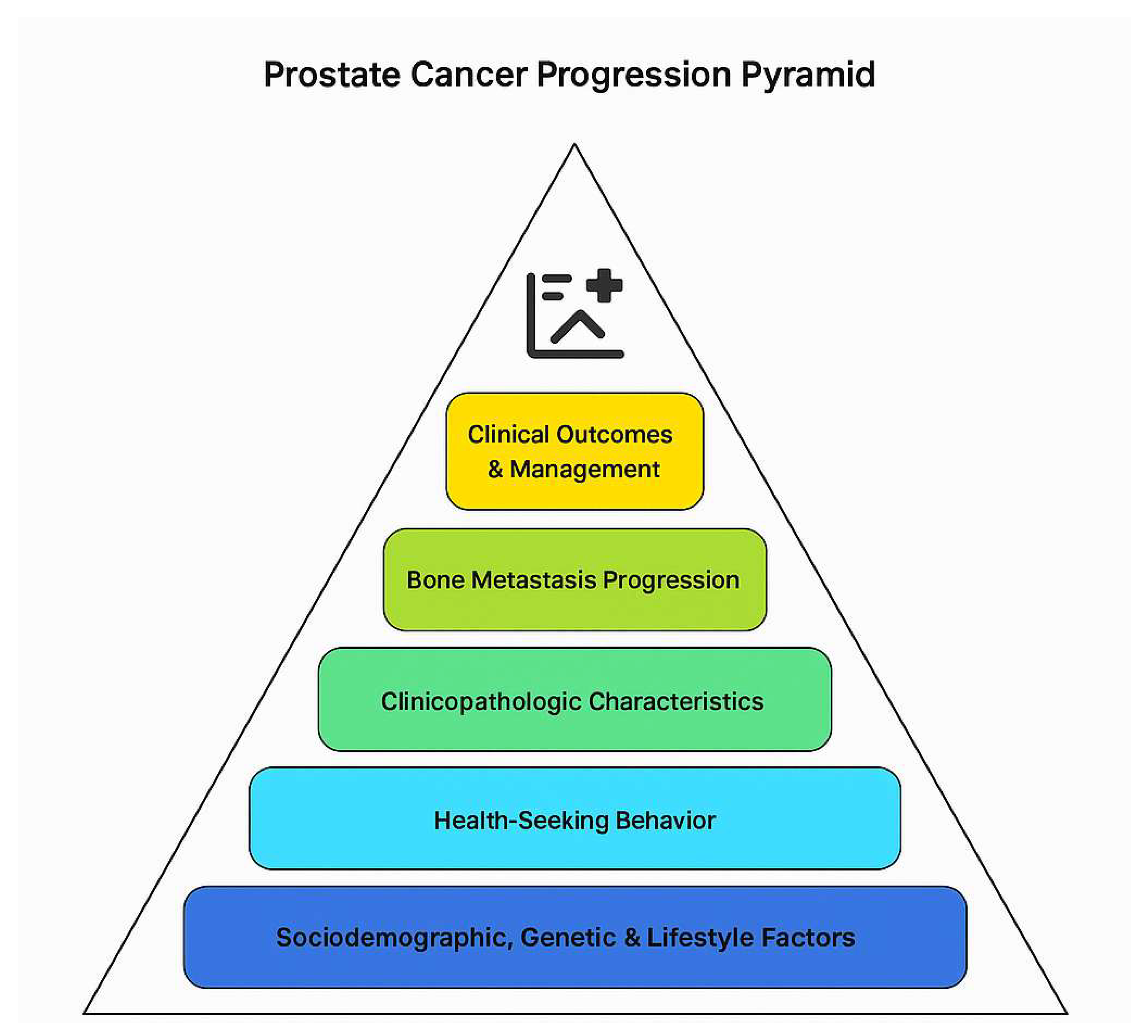

Educational attainment was high, with nearly half (48%) reporting tertiary education, 28% secondary education, 21.0% basic education, and 3.0% no formal education (

Figure 2).

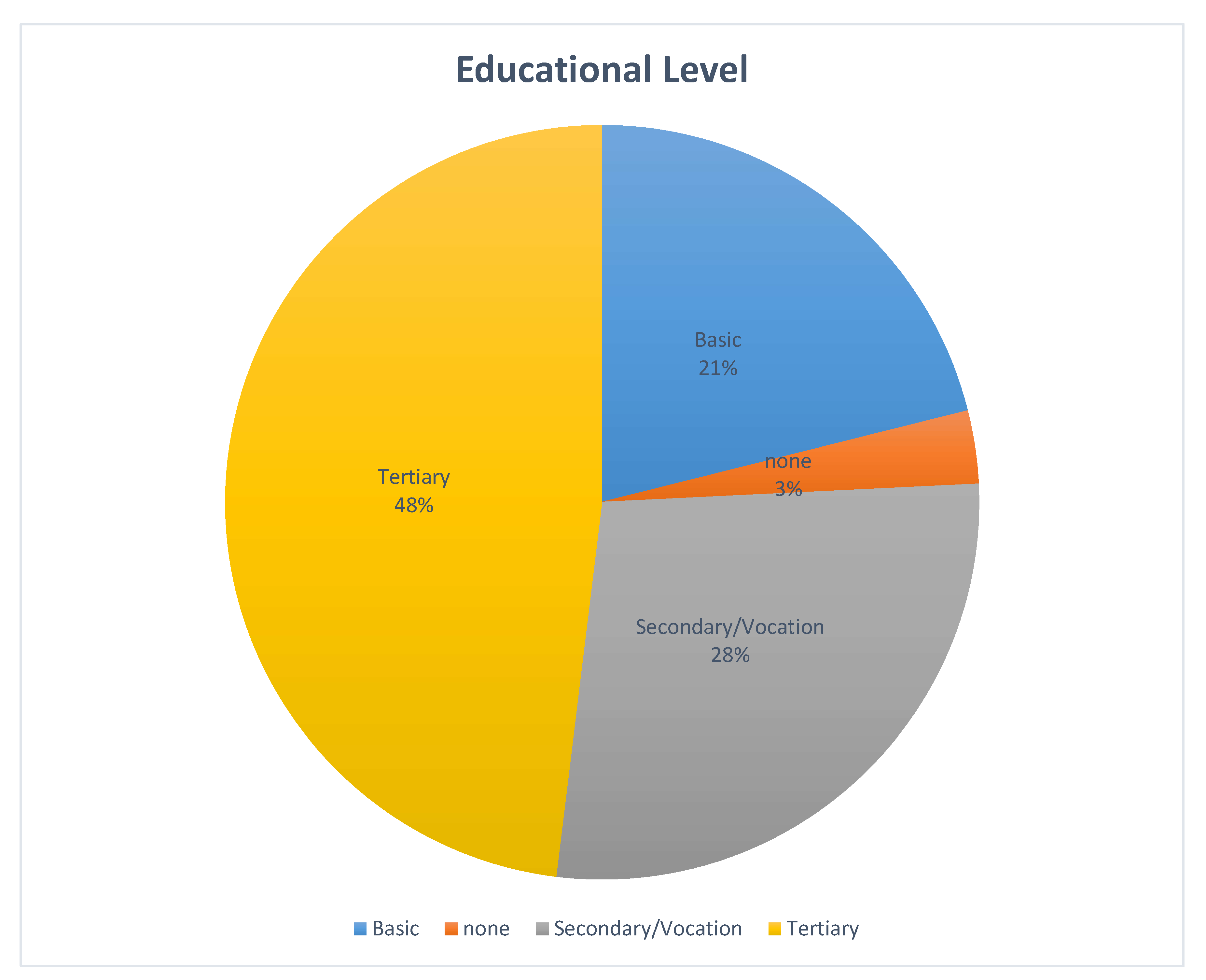

Civil servants/administrators comprised the largest occupational group (25.1%), followed by businessmen/traders (17.4%) and professionals (17.0%); artisans (13.5%) and farmers/fishermen (7.3%) followed closely

Figure 3). Academics were 2.3%.

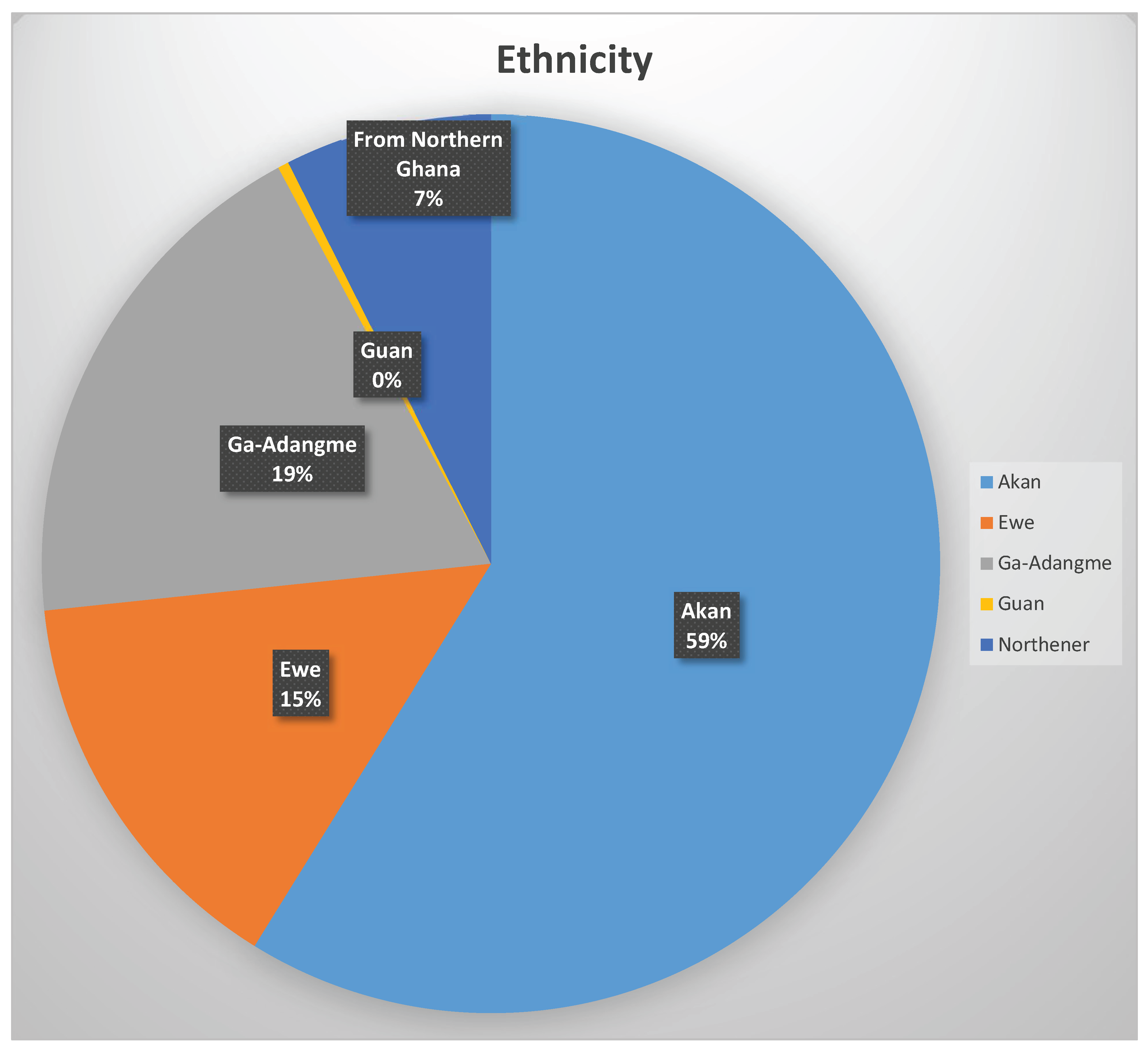

Ethnic distribution was dominated by Akans (59%), followed by Ga-Adangbes (19%) and Ewes (15%). Guans were the least represented, while participants from northern Ghana comprised only 7% (

Figure 4).

A positive family history of prostate cancer was reported by 21.3% of participants, most often involving a brother (8.1%) or father (6.6%) (

Table 2).

Regarding lifestyle, only 11.6% reported smoking, mostly <10 pack-years (8.9%). Alcohol intake was reported by 52% (Tables 3 & 4).

Table 3.

History of smoking.

Table 3.

History of smoking.

| Category |

Frequency |

Percentage (%) |

| No |

228 |

88.8 |

| Yes |

30 |

11.6 |

| Pack-years smoked |

Frequency |

Percentage (%) |

| 0 |

228 |

88.3 |

| 1–10 |

23 |

8.9 |

| 11–20 |

4 |

1.6 |

| >20 |

3 |

1.2 |

Table 4.

Alcohol intake.

| Response |

Frequency |

Percentage (%) |

| No |

124 |

48.0 |

| Yes |

134 |

52.0 |

Bone pain was reported by 47.3% of participants before bone scan evaluation. Of those without bone pain, 25.1% had bone metastases; of those with bone pain, 48.4% had bone metastases (

Table 5).

Clinicopathological Features

On digital rectal examination (DRE), 40.3% had low-risk disease (T1–T2a), 14.3% intermediate risk (T2b), and 45.3% high risk (T2c or above) (

Table 6).

By ISUP grade, 30.6% were Grade 1, 36.8% Grade 2–3, and 32.6% Grade 4–5 (

Table 7).

PSA risk categorization revealed that 71.7% had PSA >20 ng/ml (

Table 8). D’Amico classification showed 80.6% in the high-risk category (

Table 9).

Bivariate Analysis

To assess the relationships between sociodemographic, lifestyle, family history, and bone pain (independent variables) and each clinicopathological feature (dependent variables), a series of chi-square tests were performed. These analyses identify which baseline characteristics were significantly associated with disease severity and extent.

Table 10 shows the chi-square associations between each clinicopathological dependent variable against sociodemographic, lifestyle, family history, and bone pain predictors, with the chi-square statistics, and p-values.

The bivariate analysis revealed several statistically significant associations. Educational level was significantly associated (inversely) with bone metastasis (χ2 = 12.299, p = 0.011), PSA category (χ2 = 25.40, p = 0.013), DRE category (χ2 = 19.43, p = 0.0127), PSA density (χ2 = 24.85, p = 0.0156), ALP (χ2 = 22.97, p = 0.028), percentage of cores involved (χ2 = 94.27, p = 0.0234), PSA–Age index (χ2 = 27.57, p = 0.0064), PSA–Age deviation (χ2 = 26.41, p = 0.0094), bone pain, (p<0.05) and number of metastatic sites (χ2 = 41.71, p = 0.003).

Occupation was not significantly associated with disease severity. Alcohol intake showed some association with bone metastasis (p=0.033), whereas smoking influenced metastasis distribution patterns but not presence/absence.

Religion showed significant associations with PSA category (χ

2 = 7.82, p = 0.0498), ISUP grade group (χ

2 = 33.80, p < 0.001), ISUP risk group (χ

2 = 7.44, p = 0.0242), Gleason score (χ

2 = 60.50, p < 0.001), PSA–Age index (χ

2 = 7.91, p = 0.0479), and PSA–Age deviation (χ

2 = 7.91, p = 0.0479). Alcohol intake (χ

2 = 8.739, p = 0.033) and bone pain (χ

2 = 9.007, p = 0.011. Pathological factors including ISUP grade (χ

2 = 66.500, p < 0.001), DRE category (χ

2 = 34.85, p < 0.001), serum ALP (χ

2 = 168.33, p < 0.001), percentage of cores involved (χ

2 = 40.12, p = 0.029), and perineural invasion (χ

2 = 7.505, p = 0.029) also showed strong associations with bone metastasis. In contrast, variables such as ethnicity (p = 0.940), occupation (p > 0.28), family history of prostate cancer (p = 0.572), smoking history (p = 0.138), prostate volume (p = 0.940), perivascular invasion (p = 0.346), and cribriform/intraductal pattern (p = 0.080) demonstrated no statistically significant relationship with most clinicopathological features (

Table 10).

Chi-square analysis also revealed strong associations between PSA levels and Gleason score, ISUP grade, and DRE risk category (all p<0.001), but not prostate volume. Higher PSA values were linked to higher-grade disease and more advanced DRE findings (

Table 11).

Logistic Regression Analysis

Bivariate logistic regression demonstrated that ISUP 4 (OR=7.94, p<0.0001) and ISUP 5 (OR=42.0, p=0.0099) strongly predicted PSA >100 ng/ml, while ISUP 1 (OR=0.06, p<0.0001) and ISUP 2 (OR=0.36, p=0.0391) were protective. High DRE risk (OR=9.4, p<0.0001) was similarly predictive of very high PSA, while low DRE risk was protective (OR=0.09, p<0.0001).

Age ≥75 years predicted higher tumour volume (percentage of core biopsy) on biopsy (OR=4.11, p<0.0001) and multiple bone metastasis sites (OR=2.16, p=0.023).

Religion-based analysis indicated that Muslim patients had higher odds of PSA in the top quartile (>124.48 ng/ml) (OR=3.27, p=0.023) and high-grade Gleason disease (OR=3.30, p=0.033).

Higher educational attainment significantly reduced the odds of high PSA, high PSA density, and metastasis. Tertiary education was associated with an 88% reduction in bone pain at presentation (OR=0.12, p=0.0503) and a 90% reduction in high PSA (>38 ng/ml) (OR=0.10, p=0.0056) compared to no education.

Discussion

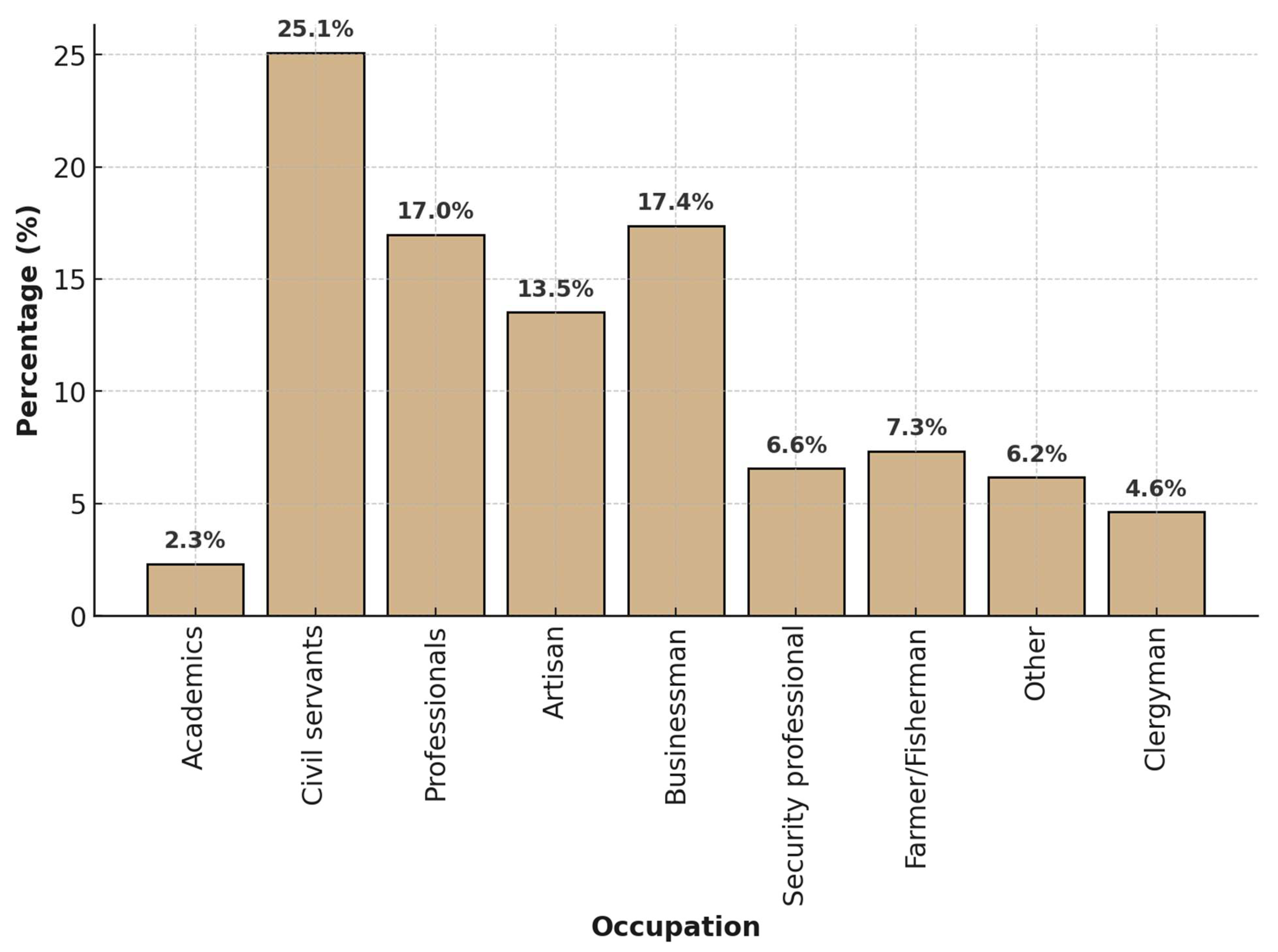

Summary of Key Findings

The study population was predominantly aged 60–79 years (68.7%), with 71.7% having PSA ≥20 ng/mL, 45.3% high risk DRE findings, 32.6.% high risk ISUP grade (≥4), 80.6% in the high-risk D’Amico category. Bone metastases were confirmed in 38% of cases. Educational level, religion, bone pain, and pathological factors—including ISUP grade (χ2 = 66.50, p < 0.001), DRE risk (χ2 = 34.85, p < 0.001), ALP (χ2 = 168.33, p < 0.001), percentage of cores involved (χ2 = 40.12, p = 0.029), and perineural invasion (χ2 = 7.505, p = 0.029)—were significantly associated with adverse clinicopathological parameters. Conversely, ethnicity (p = 0.940), occupation (p > 0.28), family history of prostate cancer (p = 0.572), smoking (p = 0.138), and prostate volume (p = 0.940) showed no significant associations.

PSA level was strongly associated with ISUP grade, DRE risk category, and D’Amico classification, with higher PSA corresponding to more advanced disease features. Multivariable logistic regression identified education, religion, bone pain, ISUP grade, DRE risk, ALP, and percentage of cores involved as independent predictors of severe disease, mirroring patterns in PSA, DRE, ISUP, and metastasis distribution, and reinforcing the importance of these factors in risk stratification.

Comparison with Existing Literature

The age distribution in this cohort showed a near-normal curve, with a mean age of 68.18 years (median 69 years, modal age 65 years, range 47–85 years). The closeness of the mean and median suggests a symmetric distribution, supporting the application of parametric statistical methods within the accepted levels of significance. These figures closely agree with those reported by Mensah et al. in 2016 for Ghanaian men undergoing prostate brachytherapy [

5], and are consistent with other local and international studies showing that the peak incidence of PCa occurs in the seventh decade of life [

6,

7,

21]. Globally, this age pattern is linked to cumulative DNA damage, epigenetic changes, and androgen-driven cellular proliferation in the prostate gland over time [

4].

The high proportion of participants with tertiary education (48%) is notable and contrasts with earlier Ghanaian cancer cohorts reporting lower literacy rates [

15]. However, the majority still presented with advanced disease, indicating that higher education does not fully offset other barriers such as limited access to PSA screening, cultural beliefs, socioeconomic constraints, and delayed health-seeking behaviour. Similar findings in the United States suggest that while higher education may slightly increase PCa incidence—likely due to more frequent screening—it is also associated with lower mortality because of earlier detection and treatment [

15].

Bone metastases in 38% of patients confirm the high metastatic burden seen in sub-Saharan Africa, where late presentation remains common [

3,

8]. In contrast, PSA screening in high-income countries has shifted diagnosis towards localized disease. The skeletal distribution of metastases, predominantly to the axial skeleton, aligns with the “seed and soil” hypothesis in which PCa cells preferentially colonize marrow-rich bone sites [

5].

Our findings also point to sociodemographic modifiers of disease presentation. Education was inversely related to metastasis frequency (75% with no education vs. 30.9% with tertiary education), supporting the idea that health literacy facilitates earlier diagnosis. Similarly, religion showed significant associations with PSA category, Gleason score, ISUP grade, and PSA-age index—Muslim patients had over threefold higher odds of presenting with very high PSA (>124.48 ng/mL) and high-grade tumours compared to Christians. This may reflect differences in healthcare access, awareness, or cultural attitudes to screening.

Several pathological variables were strong predictors of bone metastases, including high PSA, elevated ALP, perineural invasion, higher ISUP grade, and advanced DRE category—all in keeping with established metastatic risk factors [

8,

10]. Conversely, ethnicity, occupation, smoking status, and family history showed no statistically significant association with metastasis, though small subgroup sizes may limit interpretation.

PSA demonstrated robust associations with ISUP grade, DRE risk, and D’Amico classification, with increasing PSA levels corresponding to a higher proportion of aggressive histology and advanced clinical staging. Logistic regression further identified ISUP grades 4–5 and high-risk DRE findings as strongly predictive of PSA >100 ng/mL, highlighting their diagnostic and prognostic value.

Overall, this study reinforces the aggressive clinicopathological profile of prostate cancer in Ghanaian men, with frequent high-grade, high-stage presentations and a substantial metastatic burden. Public health strategies must therefore prioritize earlier detection through targeted screening and education, while also addressing systemic barriers to timely diagnosis and treatment.

What Is Already Known About This Topic

Prostate cancer is the most common malignancy among men in Ghana and sub-Saharan Africa, frequently presenting at advanced stages.

High PSA levels, abnormal digital rectal examination (DRE) findings, and high Gleason/ISUP grades are established markers of aggressive disease.

Late presentation is often attributed to limited screening, poor awareness, socioeconomic barriers, and cultural beliefs.

While some studies in Ghana have described demographic and clinical profiles, few have comprehensively examined associations between sociodemographic factors, lifestyle variables, and multiple clinicopathological indicators within the same cohort.

What This Study Adds

Provides simultaneous analysis of sociodemographic, lifestyle, and pathological variables with PSA, DRE risk category, ISUP grade, D’Amico classification, and bone metastases in a large Ghanaian cohort.

Demonstrates that lower educational attainment, certain religious affiliations, bone pain, high ALP, greater tumour core involvement, and high risk ISUP/DRE categories are independent predictors of severe disease.

Shows strong associations between PSA levels and both histological grade (ISUP) and clinical staging systems (DRE and D’Amico).

Highlights that ethnicity, occupation, smoking, and family history were not significantly associated with advanced disease in this population.

Offers evidence to support targeted community education, earlier screening, and risk-based assessment protocols in resource-limited settings.

Limitations of the Study

Firstly, the cross-sectional retrospective design relies on existing medical records, which may have incomplete or missing data for certain variables such as family history, comorbidities, and exact timing of symptom onset, potentially introducing information bias.

Secondly, this study was conducted at a single tertiary referral center in an urban setting, which might limit the generalizability of findings to prostate cancer patients from rural or underserved regions of Ghana with different socio-demographic characteristics and healthcare access.

Thirdly, the sample size, while sufficient for descriptive analysis, restricts the power of inferential statistics to detect smaller associations or perform multivariate analyses controlling for confounding variables.

Additionally, the study did not incorporate molecular or genetic analyses that could elucidate underlying biological differences in tumour behaviour among the studied population.

Finally, changes in referral patterns or diagnostic technologies during the study period were not accounted for, which may affect representativeness.

Future prospective multicenter studies with larger cohorts and inclusion of molecular profiling are recommended to address these limitations and provide a more comprehensive understanding of prostate cancer patterns in Ghana.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that prostate cancer in Ghanaian men commonly presents at an advanced stage, with high PSA levels, aggressive histopathological features, and a substantial burden of bone metastases. Sociodemographic factors—particularly lower educational attainment and certain religious affiliations—along with clinical indicators such as bone pain, high ISUP grade, advanced DRE category, elevated ALP, and greater tumour core involvement, were strongly associated with disease severity. Multivariable analysis confirmed these as independent predictors of advanced presentation, underscoring their potential value in risk stratification where access to full diagnostic resources is limited. These findings highlight the urgent need for targeted community education, earlier screening, and streamlined referral pathways to improve detection and outcomes for prostate cancer in resource-constrained settings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Frank Obeng; Data curation, Frank Obeng, Clement Korsah, Selasie Owiafe and Nii-Boye Hammond; Formal analysis, Frank Obeng; Investigation, Frank Obeng, Clement Korsah and Nii-Boye Hammond; Methodology, Frank Obeng, Clement Korsah and Nii-Boye Hammond; Project administration, Frank Obeng and Clement Korsah; Resources, Frank Obeng, Clement Korsah, Selasie Owiafe and Nii-Boye Hammond; Software, Frank Obeng, Selasie Owiafe and Nii-Boye Hammond; Supervision, Nii-Boye Hammond; Validation, Frank Obeng, Clement Korsah, Selasie Owiafe and Nii-Boye Hammond; Visualization, Selasie Owiafe; Writing – original draft, Frank Obeng and Nii-Boye Hammond; Writing – review & editing, Frank Obeng, Clement Korsah and Selasie Owiafe. All authors have agreed to the submitted version of the manuscript.