Introduction

Prostate cancer (PCa) exerts significant burden globally both in the health sector and economic sector. It is ranked top 5 in both incidence and mortality globally, in incidence after lung, breast and colorectal cancer and in mortality after lung, liver, stomach cancer [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. Zhang et al. (2023) in their Systematic Analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study concluded prostate cancer is the most common diagnosed cancer in men [

3]. In Africa, statistics show that prostate cancer is as loud as it is globally but there are discrepancies [

5,

6,

7,

8] which is most likely due to poor cancer registration systems [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]. Evidence suggests that most new cases of cancers are now found in Africa and low-and middle-income countries (LMICs), increasing from 15% in 1970, to 56% in 2008, and projected to reach about 70% by 2030 [

4].

Numerous epidemiologic studies have linked PCa risk to various factors, i.e. age, ethnicity, family history, insulin-like growth factors, lifestyle, diet, environmental and occupational exposure [

9]. The unequal prevalence of PCa among Black men can be linked to various factors, including personal, provider, institutional, and health system influences. Factors related to black men that have been associated with disparities in prostate cancer (PCa) include limited knowledge about PCa, lack of awareness regarding PCa risks, and delays in detection efforts for PCa [

10]. Therefore, interventions and strategies to reduce the PCa health problems are essential, especially those that aim to address community, family and personal factors through behavioral-change intervention programs.

Due to its global burden, many interventions have been implemented to help spread the information on the topic. Most commonly used method is the focused group talk which has sort of become the traditional method of educating the public not just on prostate cancer but almost everything [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. Researchers like F. T. Odedina et al. (2004) used this method in their approach to educate their sample population and gained significant increase in their knowledge of prostate cancer in their result [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. Other noticeable method is by Odedina et al. (2014) known as the Working through Outreach to Reduce Disparity (W.O.R.D) on Prostate Cancer which employed the use recorded video sketches as the mode of education [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. They also adapted the use of a Consensus Working Group using the NCI-Grid-Enable Measures (GEM) platform with two Special Interest Groups to focus on behavioral and epidemiology topics [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. To be more inclusive, Kaskowitz et al. (2006) in their article titled Bringing prostate cancer education to deaf men, used the American Sign Language (ASL) as their mode of communication [

12]. Sadly, the improvement seen in most if not all these implementations are only modest in their early phases [

13].

Keywords in prostate cancer management are screening, early detection, diagnosis, and curative treatments. However, these pillars of utopia are not readily available in most subcontinents in Africa for prostate cancer management. This, together with the rapid population growth, increasing life expectancy, urbanization with progressively westernized lifestyles [

4] have contributed to the high frequency of advanced prostate cancer in Africa. Late or advanced stages of prostate cancer and almost every other cancer is difficult to treat and mostly the choices of management are palliative care . There also exist barriers to the treatment of advanced cases in low- and- middle- income countries (LMICs [

4]).

Prostate cancer’s effect is felt globally, but quite disproportionately among Black men. According to studies, [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12] the highest estimated mortality rates of this disease were found in the Caribbean (Barbados Trinidad and Tobago, and Cuba), sub-Saharan Africa (South Africa), parts of former Soviet Union (Lithuania, Estonia, and Latvia), whereas the lowest rates were found in Asia (Thailand and Turkmenistan). From available data, prostate cancer incidence and mortality rates have been on the decline or have stabilized recently in many countries, with decreases more pronounced in high-income countries [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. But there is an increase in trend of prostate cancer incidence with advancing age [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12].

In Nyakotey-Obu’s article titled Review of Prostate Cancer in Ghana in 2020 he compares the incidence of cervical, breast and prostate cancer using 2015 Data from the Ghana Health Service [

13,

14]. He found that prostate cancer, although had a lower incidence of 912 cases per-year, had a higher mortality rate of 75 percent as compared to 3052 cases per year of cervical cancer with 51 percent mortality and breast cancer 2260 cases with 45 percent mortality rate. He estimated the mortality rate of the prostate cancer in Ghana to be well above three times the global limit. In his article, he attributed this to the fact that there is fewer screening done for prostate cancer and also funding into prostate cancer is few and far between. A Similar article published in Ghana by (Osei Agyemang et al., 2024) to assess PCa awareness, knowledge, and screening practices considered 423 men aged at least 30 years. The result was that although majority of respondents (85.8%) were aware of PCa only 52.5% of the respondents interviewed had adequate knowledge of PCa based on their criterion. Highest educational level and occupation of respondents were found to be significantly associated with awareness and knowledge of PCa. Only, 10.2% of the respondents had ever screened for PCa. Additionally, lack of education on PCa and fear of the unknown were the most reported barriers to prostate cancer screening [

13,

14].

Focused group discussions, survey, personal interviews and consensus working groups as stated before are the methods of approach for most outreaches and public health promotion activities, and even though these methods are regularly at play there is still an increase in the incidence of PCa with increasing age in Africa [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22].

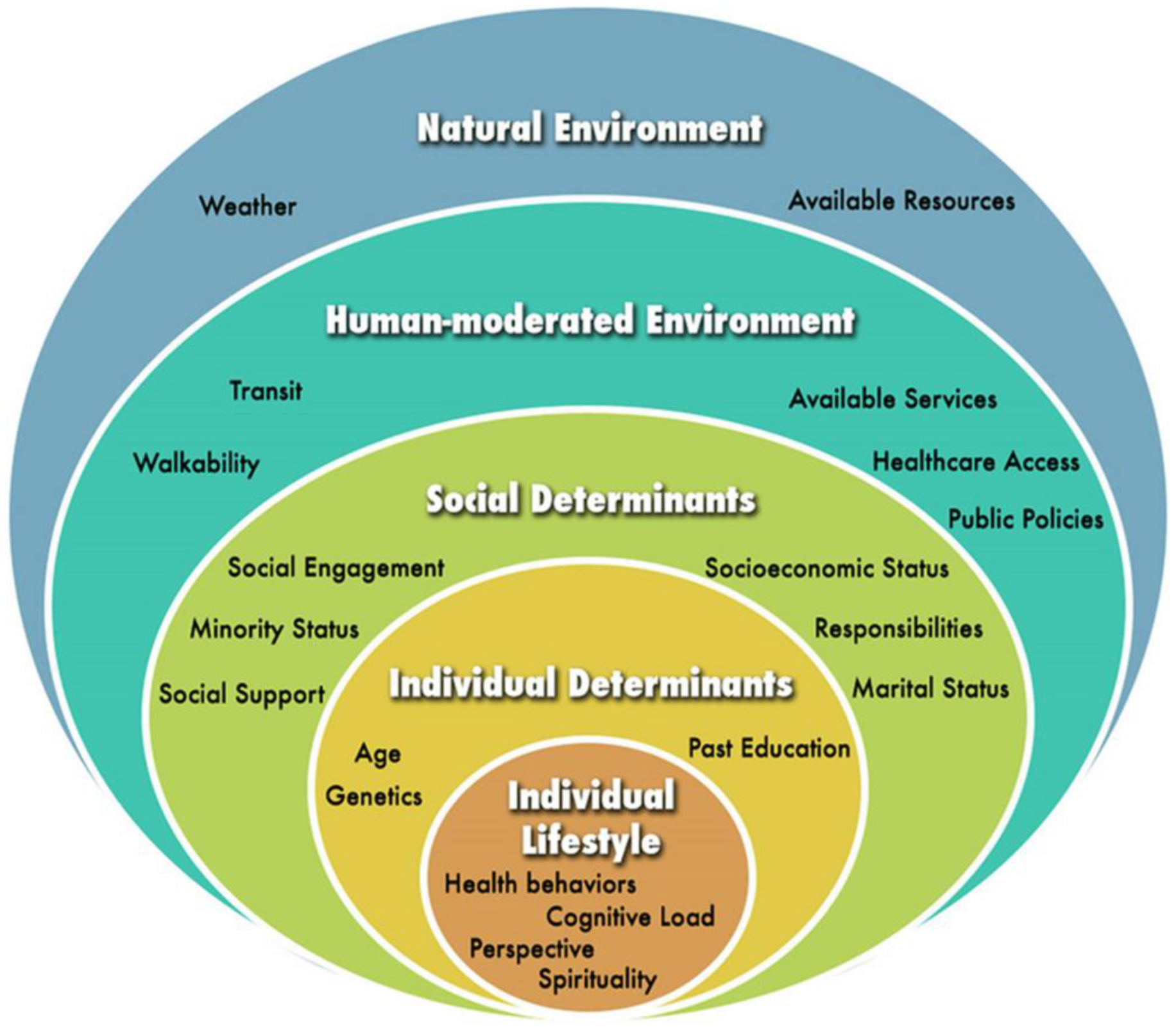

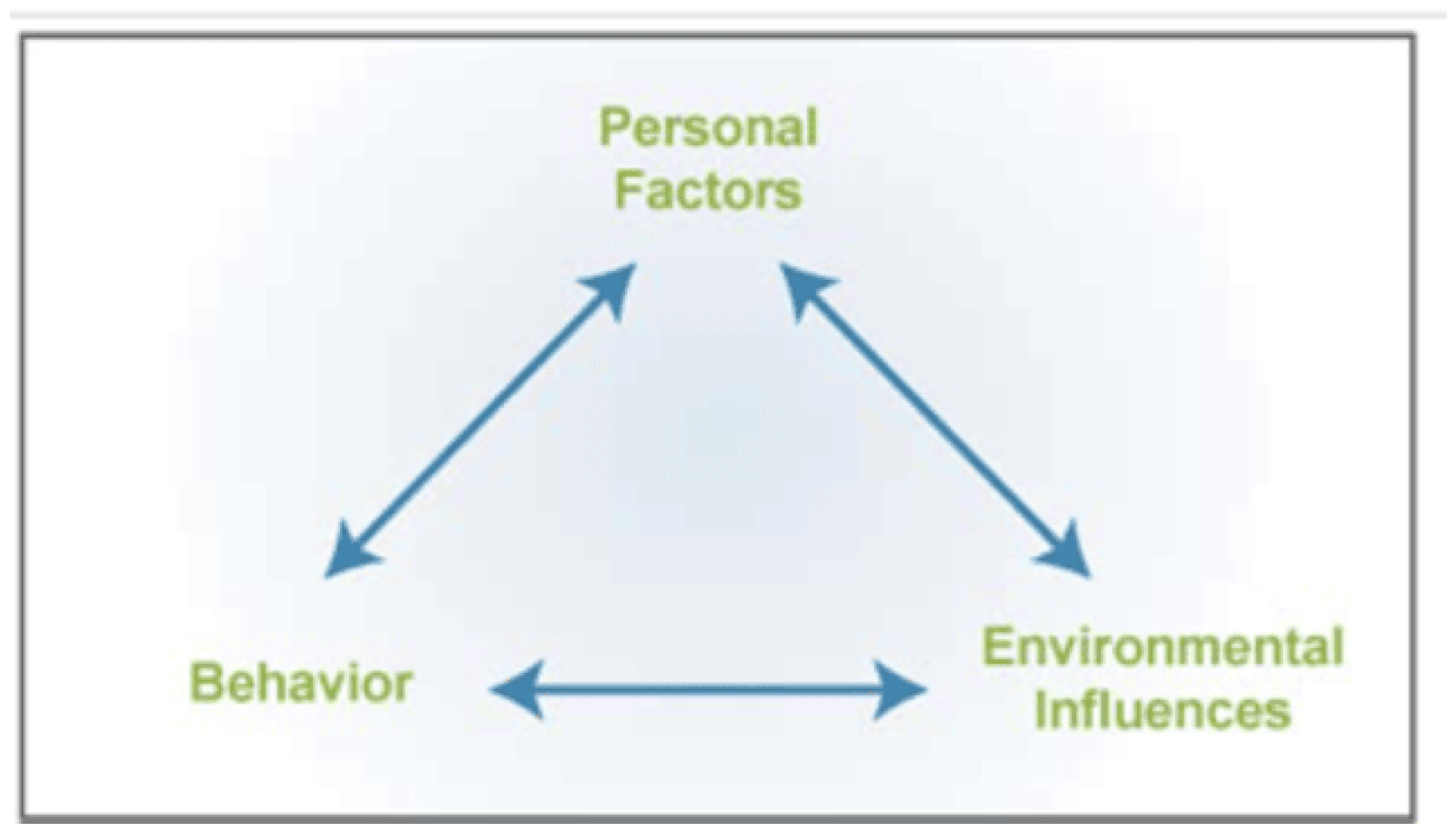

There is therefore the need to adopt new more engaging and lasting methods which will target not just the individual, but his circle of influence as well [

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29]; as stipulated by frameworks like the social cognitive theory (SCT) and the socioecological model(SEM) of health [

26,

27,

28,

29]. This approach would make these men and their circles of influence well-equipped with requisite literacy about the disease and also make them new agents of carrying information about the topic far and wide. Essentially, this study seeks to introduce the PCa board game (LIBOG) which is an adaptation from the popular mosquito ludo game from the Boateng et al. (2021) in their interventional study “Co-creation and prototyping of an intervention focusing on health literacy in the management of malaria at the community-level in Ghana” [

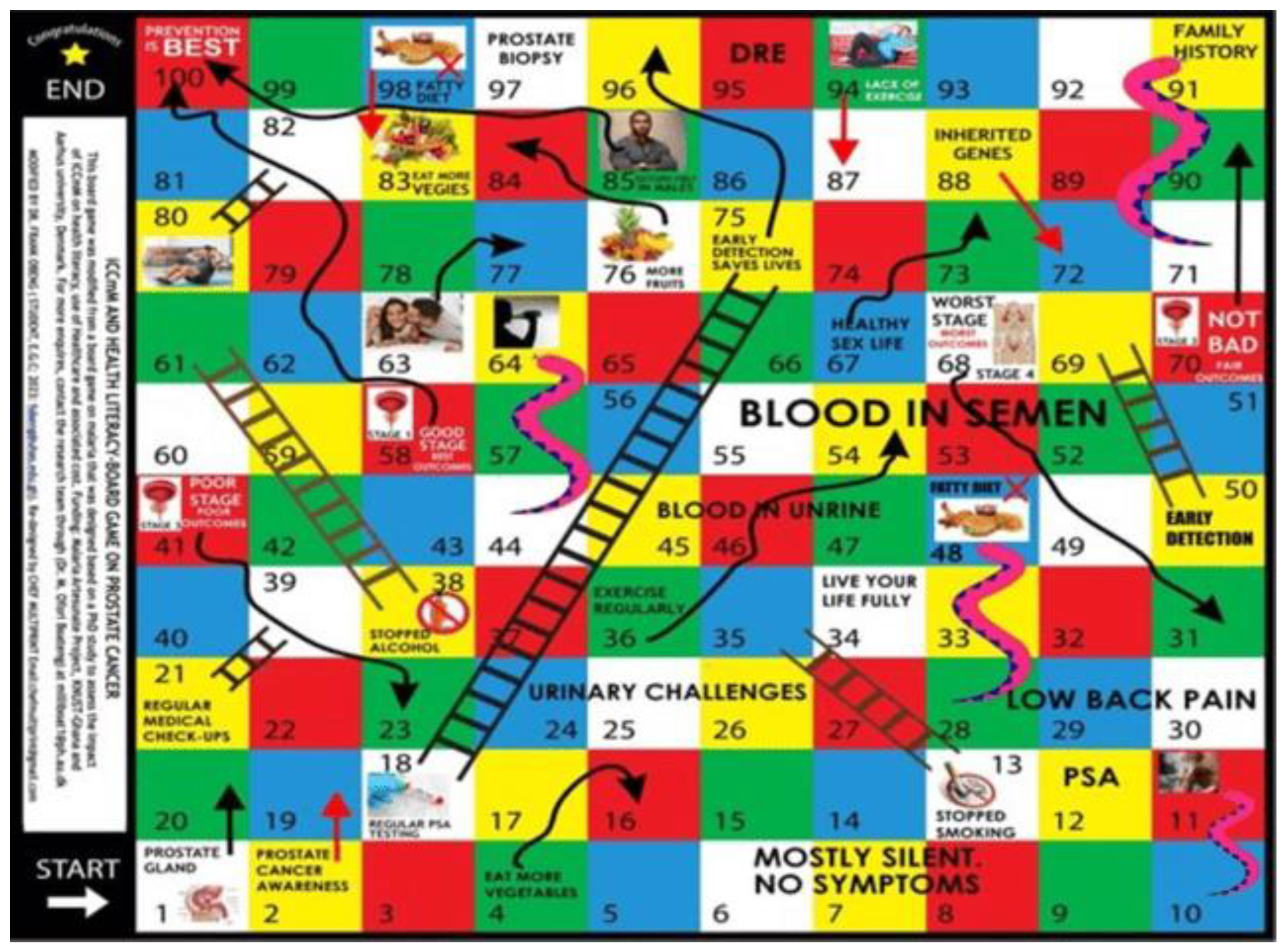

24]. The LIBOG has been modified further by basing it on the social cognitive theory (SCT) by Bandura et al., 1986 and the socioecological model (SEM) of health (McLeroy 1988 [

27,

28,

29]). Similar board games have been tried by other researchers in other important conditions like HIV/AIDS with significantly positive results, and in the learning urogenital diseases in oddity (LUDO) study that used a parches ludo game to improve the knowledge of emergency physician residents in urologic emergencies by Mallick and Waheed, 2024 [

20,

21]. Participants and facilitators favored the board game over the health talk as an educational method, in these previous studies [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

27,

28,

29,

30]). The PROCEE game designed by Cosma et al., 2016 as an innovative serious game aimed at providing prostate cancer information and risk evaluation to black African-Caribbean men (using a co-design approach) is another example of gamified approach to prostate cancer health literacy [

20,

21]. The aim of the index study therefore was to introduce and evaluate the effectiveness of a Snakes, Ladders, and Arrows Literacy board game (properly referred to as the SCT-SEM Prostate Cancer Literacy-Board- Game (S-S-LIBOG) versus traditional educational methods in enhancing prostate cancer knowledge, attitudes, and behavioral intentions amongst a Ghanaian cohort.

The primary objective of this comparative effectiveness study is to evaluate through pretest, intervention, and post- test assessments, the effectiveness of the traditional method (health talk) versus an interactive board game in improving Literacy, attitudes and intended behavior amongst participants towards prostate cancer. The secondary objective was to evaluate the usability of the board game amongst participants, in that arm of the study.

Hypothesis: The study’s null hypotheses were:

There is no difference in the proportion of participants with good knowledge of prostate cancer before and after a standard health talk intervention.

There is no difference in the proportion of participants with good knowledge of prostate cancer before and after the session of interaction with the LIBOG game.

There is no difference in the median percentage gains between LIBOG and Health Talk interventional groups in the study.

Results

Sociodemographic Characteristics of Study Participants (Pre-Intervention)

A total of 197 individuals participated in the pre-intervention phase of the study. The gender distribution showed a predominance of males, accounting for 127 participants (64.5%), followed by females at 58 (29.4%), and a small proportion identifying as other genders (12 participants, 6.1%).

The age ranged from 21 to 86 years, with a mean age of 34.3 years (±10.1). When categorized, the majority were in the middle age group (31-50 years), comprising 115 participants (58.4%). Young adults (≤30 years) accounted for 73 participants (37.1%), while the elderly (≥51 years) were 9 participants (4.6%).

With regard to educational attainment, the overwhelming majority had attained tertiary education (161 participants, 81.7%). Participants with secondary education constituted 9.6% (19 participants), while 3.0% (6 participants) and 5.6% (11 participants) had primary and postgraduate education respectively.

In terms of income level, 98 participants (49.7%) reported a medium income, 52 (26.4%) reported low income, and 13 (6.6%) were in the high-income bracket. Income data was not available for 34 participants (17.3%).

Ethnic distribution showed that Ewes formed the largest ethnic group, comprising 82 participants (41.6%), followed by Akan (26.9%), Northern Ghanaians (13.7%), Ga (6.6%), and Guan (1.5%), Others (9.6%).

Participants were fairly well distributed by place of residence: 91 (46.2%) lived in urban areas, 59 (29.9%) in rural areas, and 47 (23.9%) in suburban settings.

Tobacco use was very low, with only 1 current user (0.5%) and 13 former users (6.6%). A vast majority, 183 participants (92.9%), had never used tobacco. Alcohol use was slightly more common: 14 participants (6.6%) were current users, 46 (23.4%) were former users, and 137 (69.5%) had never consumed alcohol.

Family history of various cancers revealed that only 9 participants (4.6%) reported a family history of prostate cancer. Seventeen participants (8.6%) reported a family history of breast cancer, 5 (2.5%) had a family history of ovarian cancer, and 9 (4.6%) had relatives with bladder cancer. A family history of gastrointestinal tract (GIT) cancers was reported by 7 participants (3.0%).

Regarding exercise habits, the majority engaged in some physical activity. Light exercisers (1-2 times per week) accounted for 40.6% (80 participants), while 19.8% (39 participants) reported moderate activity (3-4 times/week). Only 10.7% (21 participants) were classified as active (≥5 times/week), and 28.9% (57 participants) led sedentary lifestyles.

Finally, dietary preferences were mostly mixed: 178 participants (90.4%) consumed a combination of fatty and vegetarian diets. Sixteen participants (8.1%) reported vegetarian diets exclusively, and only 3 participants (1.5%) consumed predominantly fatty foods.

Baseline Knowledge, Attitude and Perception (pretest results), and tests of associations at Baseline:

The baseline pretest dataset comprised a total of 197 participants categorized by various socio-demographic and behavioral characteristics, with knowledge, attitude, and perception (KAP) outcomes relating to prostate cancer awareness. These are shown in

Table 1.

Following the above age categorization that 37.1% of participants were classified as “young” (n = 73), 58.4% as “middle-aged” (n = 115), and 4.6% as “old” (n = 9), an analysis of prostate cancer knowledge levels across these age groups showed that good knowledge level was present in 49.3% of the young, 54.8% of the middle-aged, and 33.3% of the old. Poor knowledge was more pronounced among the old (55.6%) and the young (45.2%) compared to the middle-aged (39.1%). However, the association between age and knowledge level category was not statistically significant (χ² = 2.0891, p = 0.719). In terms of attitude, the young demonstrated a higher proportion of positive attitudes (60.3%) compared to middle-aged (50.4%) and older participants (55.6%), with a non-significant association (χ² = 4.2741, p = 0.370). Similarly, perception categories did not differ significantly by age (χ² = 3.5696, p = 0.467), although neutral perceptions were more common in the middle-aged group (18.3%) than in the young (11.0%) and old (0%).

Knowledge scores showed significant variation across gender (χ² = 19.9202, p = 0.001). While 62.1% of females demonstrated good level of knowledge, this was lower among males (52.0%) and entirely absent among those identifying as “other,” all of whom exhibited poor knowledge. A slightly inversed (and still statistically significant) pattern was observed in attitude categories (χ² = 32.5956, p < 0.001), with positive attitudes highest among males (60.6%) and females (51.7%), but absent among the “other” gender group, all of whom had negative attitudes. Perception scores were also significantly associated with gender (χ² = 61.2492, p < 0.001), with the “other” gender group predominantly neutral (91.7%), while males and females were more evenly distributed across categories.

From above, educational level was heavily skewed toward tertiary education (81.7%), with only small proportions having primary (3.1%), secondary (9.6%), or postgraduate (5.6%) education. A statistically significant association was observed between education level and knowledge (χ² = 13.4968, p = 0.036). Good knowledge was most common among postgraduates (63.6%) and those with tertiary education (55.9%), but much lower among those with only primary (16.7%) or secondary (21.1%) education. Attitudes also varied significantly with education (χ² = 27.4030, p < 0.001), with positive attitudes seen in 58.4% of tertiary-educated respondents and 54.6% of postgraduates, compared to just 25.0% and 33.3% of secondary and primary-level participants, respectively. Perceptions followed a similar pattern (χ² = 43.7216, p < 0.001), with positive perceptions more prevalent among tertiary-educated respondents (45.9%).

No statistically significant association was observed between ethnicity and prostate knowledge levels (χ² = 7.4478, p = 0.683), although knowledge appeared highest among the Guan (66.7%) and Ga (61.5%). However, both attitude (χ² = 34.6644, p < 0.001) and perception concerning prostate cancer (χ² = 37.1847, p < 0.001) were strongly associated with ethnicity. Positive attitudes were most frequent among Guan (66.7%) and Northern Ghanaians (63.0%), while the “Other” ethnic group had a high concentration of negative attitudes (78.9%) and poor perception scores (only 10.5% with positive perception).

Urban residents showed the highest rate of good knowledge level on prostate cancer (65.9%), compared to suburban (38.3%) and rural (40.7%) participants. This association was statistically significant (χ² = 14.5797, p = 0.006). Positive attitudes also followed a similar trend (χ² = 15.6341, p = 0.004), being most prevalent among urban (60.4%) and rural (54.2%) residents. Perceptions differed significantly as well (χ² = 9.9496, p = 0.041), with urban and rural dwellers having similar positive perception levels (43.9% and 42.4%, respectively), while suburban residents showed a more neutral outlook (27.7%).

The tobacco user-grouping were significantly associated with good knowledge level on prostate cancer (χ² = 11.8984, p = 0.018), positive attitude (χ² = 29.2372, p < 0.001), and positive perception (χ² = 55.5389, p < 0.001). Good knowledge was least common among former and current users. Among former users, 84.6% had poor knowledge, and only 7.7% exhibited a positive attitude. Notably, all current users reported negative attitudes and perceptions.

Alcohol use was reported as never by 69.5% of respondents, formerly by 23.9%, and currently by 6.6%. Significant differences in knowledge levels (χ² = 19.8448, p = 0.001), attitude (χ² = 26.6195, p < 0.001), and perception (χ² = 56.0029, p < 0.001) were found. All current users (100%) had poor knowledge levels, with a vast majority expressing negative attitudes (92.3%) and perceptions (84.6% neutral) on prostate cancer. In contrast, good knowledge and positive attitudes were more frequent among teetotalers and former users.

Family history of prostate cancer (FMH) was present in 4.6% of participants but not significantly associated with disease knowledge levels (χ² = 0.5000, p = 0.779) or attitude (χ² = 1.0431, p = 0.594). However, there was a modest but statistically significant association with perception (χ² = 6.8469, p = 0.033), as those with FMH were more likely to express neutral perceptions about the disease (44.4%) compared to those without.

Family history of breast cancer (FHBca) was not significantly associated with knowledge levels of prostate cancer (χ² = 2.2079, p = 0.332) or attitude (χ² = 2.7175, p = 0.257) but showed a significant link with perception (χ² = 6.4487, p = 0.040), as neutral perceptions were more common among those with FHBca (35.3%).

A significant association was also found between family history of ovarian cancer (FHOca) and all three KAP outcomes. All respondents with such history had poor knowledge (χ² = 7.0463, p = 0.030), negative attitudes (χ² = 12.2948, p = 0.002), and neutral perceptions (100%) (χ² = 29.7198, p < 0.001) about prostate cancer. Similarly, a history of bladder cancer (FHBlca) was significantly associated with prostate cancer knowledge levels (χ² = 8.4802, p = 0.014), attitude (χ² = 22.6015, p < 0.001), and perception (χ² = 30.3669, p < 0.001), with very poor KAP outcomes among those with such family history.

Family history of gastrointestinal cancers (GITca) was relatively rare (3.0%) and not significantly associated with prostate knowledge levels (χ² = 4.2942, p = 0.117) or attitude (χ² = 4.4776, p = 0.107), though perception showed a modestly significant association (χ² = 6.2392, p = 0.044).

Exercise habits were mostly light (40.6%) or sedentary (28.9%), with fewer reporting moderate (19.8%) or active (10.7%) lifestyles. Knowledge levels differed significantly with exercise levels (χ² = 16.9078, p = 0.010), with good knowledge highest among those engaging in moderate (61.5%) or light (60.0%) activity. Positive attitudes were also more prevalent among those with light (61.3%) and moderate (48.7%) activity levels (χ² = 18.2742, p = 0.006). Perceptions varied significantly (χ² = 36.8740, p < 0.001), with high neutral perceptions reported among the most active group (57.1%).

Lastly, significant associations were observed between diet type and prostate cancer knowledge levels (χ² = 11.3794, p = 0.023), attitude (χ² = 19.0436, p = 0.001), and perception (χ² = 44.7034, p < 0.001). Poor knowledge levels and negative attitudes towards prostate cancer were most common among vegetarians, while those consuming mixed diets showed relatively higher levels of good knowledge (54.5%) and positive attitudes (56.7%). Notably, all respondents consuming only fatty foods had negative perceptions, while vegetarians were more neutral.

In summary, statistically significant associations were found between KAP outcomes and gender, education, residence, ethnicity, lifestyle factors (exercise, diet, tobacco and alcohol use), and selected family cancer histories. These baseline findings provide insight into how socio-demographic and behavioral factors influence prostate cancer awareness and dispositions and form the foundation for evaluating the subsequent interventions in this study.

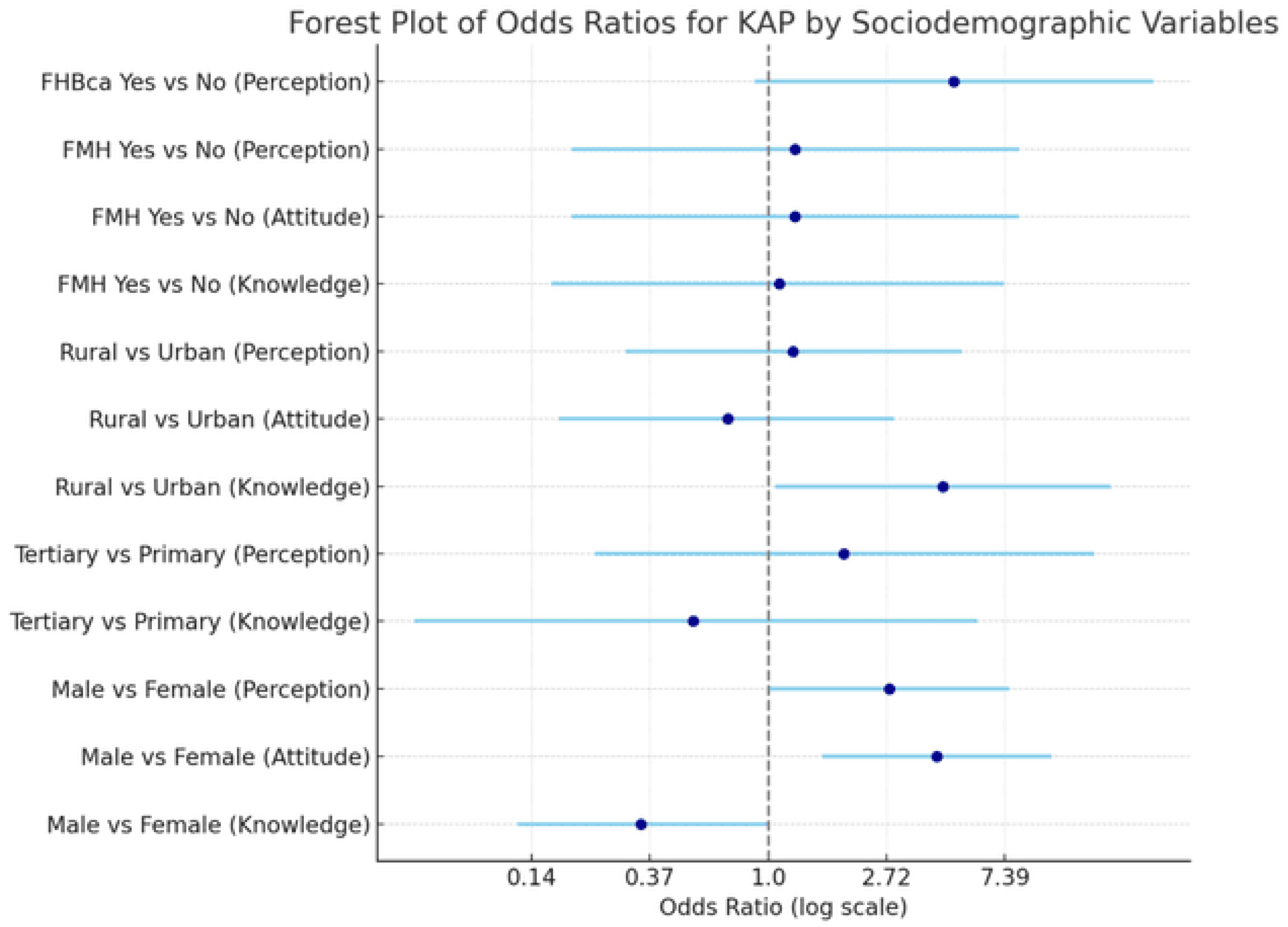

Relationships between demographic parameters and knowledge, attitude, and perception

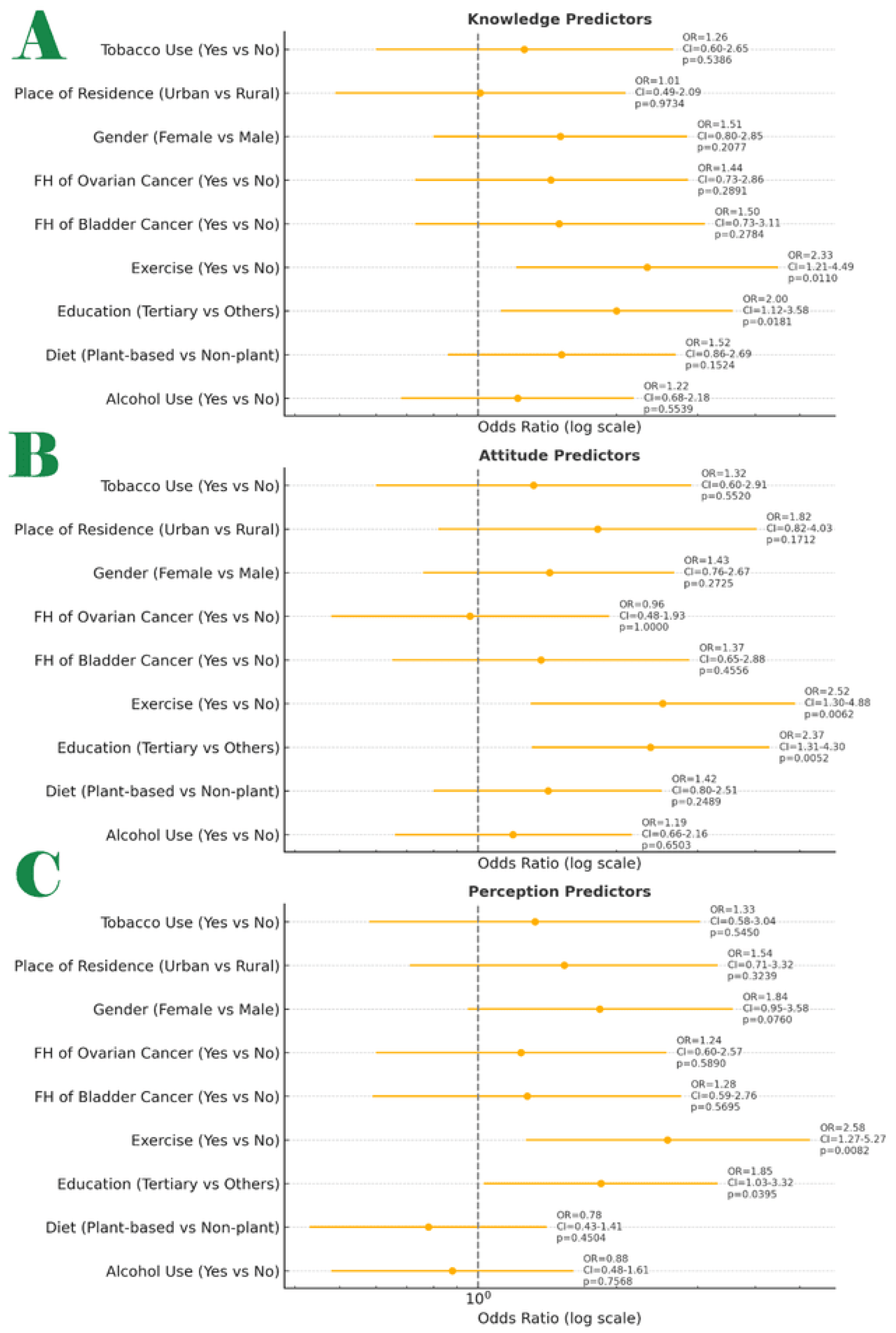

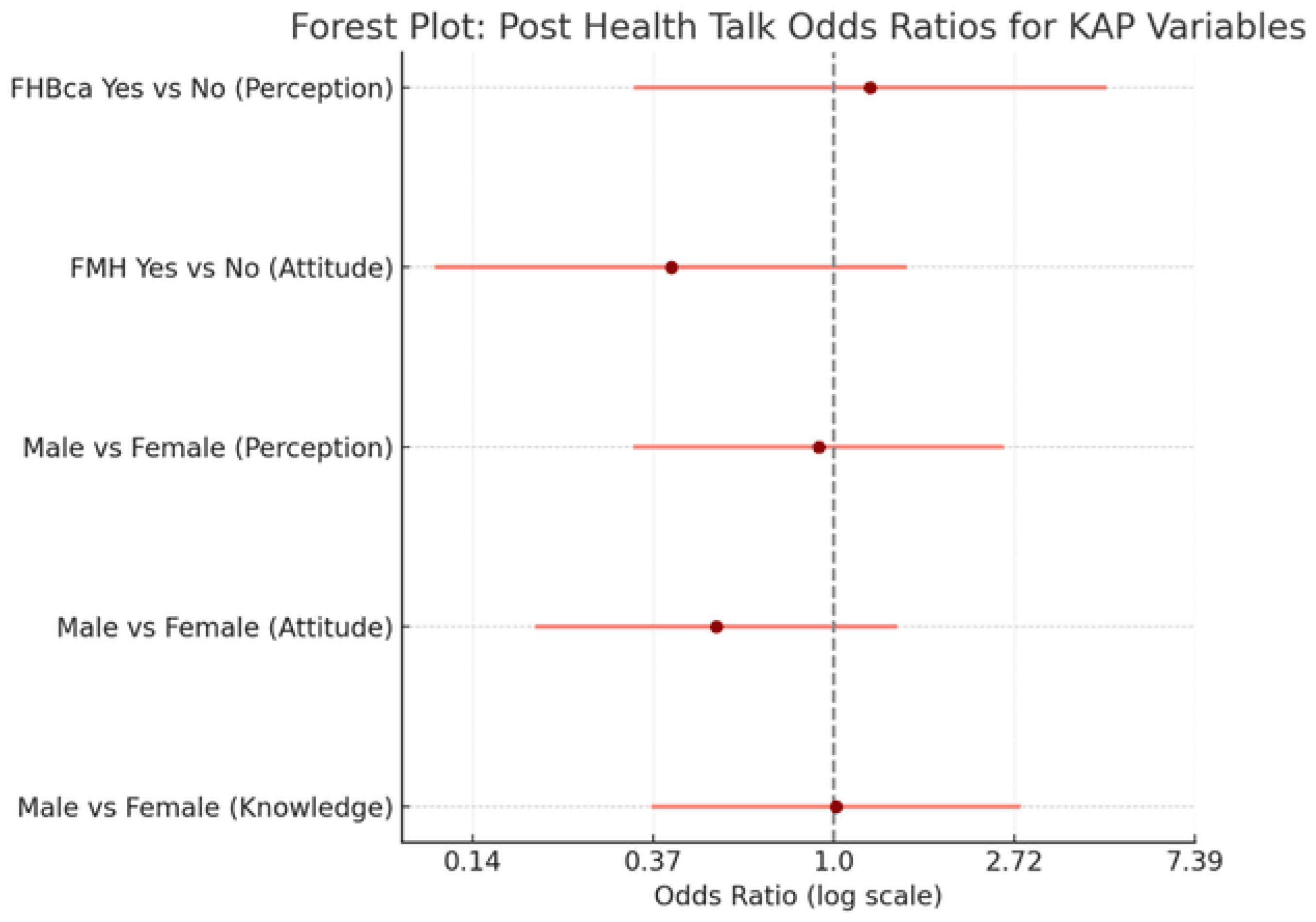

Knowledge: A forest plot was constructed to display the adjusted odds ratios (ORs), 95% confidence intervals (CIs), and p-values for the association between nine selected variables and each of the three KAP domains: Knowledge, Attitude, and Perception toward prostate cancer risk prevention and treatment methods (

Figure 4).

OR value, Confidence interval range, Exact p-value. The Statistically significant predictors (p < 0.05) were Knowledge: Tertiary education, Exercise, Attitude: Tertiary education, Perception: Tertiary education, Exercise. The odds ratios were calculated from 2x2 contingency tables using Fisher’s Exact Test and are displayed on a logarithmic scale for interpretability.

In the Knowledge domain, two factors showed statistically significant positive associations:

Tertiary education (OR = 2.37; 95% CI: 1.29-4.35; p = 0.0052) and Regular exercise (OR = 2.14; 95% CI: 1.11-4.14; p = 0.0225)

In the Attitude domain, only tertiary education remained statistically significant (OR = 2.37; 95% CI: 1.29-4.35; p = 0.0052)

In the Perception domain, both tertiary education and exercise were again found to be significantly associated with correct perception (OR = 1.85; 95% CI: 1.03-3.32; p = 0.0395), Regular exercise (OR = 2.57; 95% CI: 1.22-5.41; p = 0.0132).

Other variables-such as gender, place of residence, dietary pattern, tobacco use, alcohol use, and family history of cancer-showed non-significant associations across the three domains.

Multivariate Analysis

Baseline knowledge, Attitude and Perception levels as a function of participants Socio-demographic features were used in multivariate logistic regression analyses.

Table 2 shows the outputs.

Good Knowledge

After adjusting for socio-demographic and lifestyle variables, only exercise habits emerged as a significant predictor of good knowledge about prostate cancer. Respondents who exercised regularly had significantly higher odds of having good knowledge level compared to those who did not (AOR = 1.45, 95% CI: 1.06-1.98, p = 0.0207). Gender showed a borderline association, with males having higher odds of good knowledge than females (AOR = 1.81, 95% CI: 0.94-3.46, p = 0.0751), although this did not reach statistical significance. Educational level and income level were not significantly associated with knowledge in this model.

Positive Attitude

Significant predictors of a positive attitude toward prostate cancer screening included gender, income level, and exercise habits. Males were more than twice as likely as females to exhibit a positive attitude (AOR = 2.56, 95% CI: 1.30-5.01, p = 0.0062). Higher income levels were associated with greater odds of a positive attitude (AOR = 1.34, 95% CI: 1.01-1.77, p = 0.0395). Additionally, participants who exercised regularly were significantly more likely to have a positive attitude (AOR = 1.58, 95% CI: 1.15-2.17, p = 0.0047). Educational level was not significantly associated with the attitude towards the disease.

Correct Perception

Among the predictors examined, gender was the only variable significantly associated with correct perception. Males were substantially more likely to have correct perception scores than females (AOR = 16.84, 95% CI: 4.92-57.63, p < 0.0001). No significant associations were found between perception and educational level (AOR = 1.28, p = 0.5706), income (AOR = 0.85, p = 0.3179), or exercise habits (AOR = 1.14, p = 0.451).

Logistic Regression Equations (Logit Models): Let Y₁ = Good Knowledge, Y₂ = Positive Attitude, Y₃ = Correct Perception; then,

\log\left(\frac{P(Y=1)}{1 - P(Y=1)}\right) = \beta_0 + \beta_1X_1 + \beta_2X_2 + \dots + \beta_nX_nlog(1−P(Y=1)P(Y=1))=β0+β1X1+β2X2+…+βnXn

where:

P(Y=1)P(Y=1)P(Y=1) is the probability of the outcome (e.g., Good Knowledge)

β0\beta_0β0 is the intercept

βi\beta_iβi are the logit coefficients (ln(AOR)

XiX_iXi are the predictor variables

Model 1: Good Knowledge (with the variable codes in

Table 3),

\log\left(\frac{P(\text{Good Knowledge})}{1 - P(\text{Good Knowledge})}\right) = -2.9591 + 0.5910(\text{Gender}) - 0.0114(\text{Educational Level}) + 0.1319(\text{Income Level}) + 0.3696(\text{Exercise Habits})log(1−P(Good Knowledge)P(Good Knowledge))=−2.9591+0.5910(Gender)−0.0114(Educational Level)+0.1319(Income Level)+0.3696(Exercise Habits)

Model 2: Positive Attitude

\log\left(\frac{P(\text{Positive Attitude})}{1 - P(\text{Positive Attitude})}\right) = -3.5066 + 0.9401(\text{Gender}) - 0.1748(\text{Educational Level}) + 0.2944(\text{Income Level}) + 0.4552(\text{Exercise Habits})log(1−P(Positive Attitude)P(Positive Attitude))=−3.5066+0.9401(Gender)−0.1748(Educational Level)+0.2944(Income Level)+0.4552(Exercise Habits)

Model 3: Correct Perception

\log\left(\frac{P(\text{Correct Perception})}{1 - P(\text{Correct Perception})}\right) = -6.3479 + 2.8234(\text{Gender}) + 0.2476(\text{Educational Level}) - 0.1626(\text{Income Level}) + 0.1316(\text{Exercise Habits})log(1−P(Correct Perception)P(Correct Perception))=−6.3479+2.8234(Gender)+0.2476(Educational Level)−0.1626(Income Level)+0.1316(Exercise Habits)

Intervention (Post-baseline): (1) Participants’ interaction with the Literacy Board Game (study arm). (2) Participants listened to a standardized PowerPoint Health Talk on Prostate Cancer (control Arm). Assignment of participants to the respective arm was determined by systematic random sampling of the baseline participants into two groups, and the toss of a dice to determine which group experiences which intervention. After editing and validating the filled post-test questionnaires and accounting for attrition (which unfortunately was quite extreme in the post-intervention phase of the study (28.4%), the LIBOG arm had 80 participants, whilst the HT arm had 61 participants.

Post-Intervention Summary of Knowledge, Attitude, and Perception Towards Prostate Cancer After playing/interacting with the LIBOG: Following the LIBOG game intervention (

Figure 5), a comprehensive analysis was conducted across multiple demographic and behavioral variables to assess the KAP changes. The new associations/relationships between the sociodemographic/ lifestyle factors and knowledge, attitude, and perception (KAP) regarding prostate cancer screening were also studied.

Chi-Square Analysis Post-LIBOG: Gender and Knowledge, Attitude, and Perception

Among females, 43.14% had poor knowledge, 1.96% had moderate knowledge, and 54.9% had good knowledge. Among males, 20.69% had poor knowledge, 3.45% moderate, and 75.86% had good knowledge. Although males appeared to show a higher proportion of good knowledge, this difference remained statistically non-significant (χ²(2) = 4.12, p = 0.127). At baseline, there was statistical significance in this aspect. This suggested a bridge in knowledge level disparities after the intervention.

Attitude still showed a statistically significant difference (χ²(2) = 9.81, p = 0.007). 49.02% of females had a negative attitude, 19.61% neutral, and 31.37% positive attitude, whereas 16.67% of males had a negative attitude, 20.00% neutral, and 63.33% positive attitude.

Perception was no longer significantly associated with gender (χ²(2) = 3.56, p = 0.168). 45.10% of females had a negative perception, 1.96% neutral, and 52.94% positive perception. For males, 26.67% had a negative perception, none were neutral, and 73.33% had positive perception.

Education Level and Knowledge, Attitude, and Perception

Among postgraduates, 77.78% had poor knowledge, 0.00% moderate, and 22.22% good knowledge. Among primary school participants, 25% had poor knowledge, none were moderate, and 75% had good knowledge. The highest ‘good knowledge level’ was seen in primary school respondents. The association has now become statistically non-significant (χ²(6) = 8.51, p = 0.203) post-intervention.

Attitudes no longer showed significant differences (χ²(6) = 5.38, p = 0.496). Positive attitudes were most common among postgraduates (22.22%) and secondary school respondents (25.00%). Neutral attitudes remained unchanged, while negative attitudes ranged from 25% to 66.67%.

Perception after LIBOG intervention, also lacked significant association with education level (χ²(6) = 8.58, p = 0.199). The highest proportion of good perception (66.67%) was among tertiary and primary respondents. Neutral perceptions were very low or absent across all education levels.

Ethnicity and Knowledge, Attitude, and Perception

Knowledge remained not significantly associated with ethnicity (χ²(10) = 6.99, p = 0.726). Good knowledge was highest among Ga (80.00%) and Guan (100.00%), and lowest among Northern Ghanaians (55.56%).

Attitude now shifted and showed no statistically significant variation (χ²(10) = 3.90, p = 0.952). Positive attitudes were most prominent among Ga (60.00%) and Guan (100.00%), post LIBOG.

Perception persisted in showing a significant association with ethnicity (χ²(10) = 27.96, p = 0.002). The highest proportion of good perception was among Guan (100%), Ga (60.00%), and Northern Ghanaians (55.56%). The lowest positive perception was among Ewes (34.15%), post LIBOG.

Residence and Knowledge, Attitude, and Perception associations also evened out:

Knowledge levels did not differ significantly across residence (χ²(4) = 3.05, p = 0.549). Rural residents had 72.73% good knowledge, suburban 38.46%, and urban 37.78%.

Attitude and perception were also not significantly associated with residence (Attitude: χ²(4) = 0.70, p = 0.952; Perception: χ²(4) = 1.72, p = 0.786). Positive attitudes and perceptions were slightly more prevalent among suburban and rural residents post LIBOG. The LIBOG changes are shown in

Table 4 and

Figure 6.

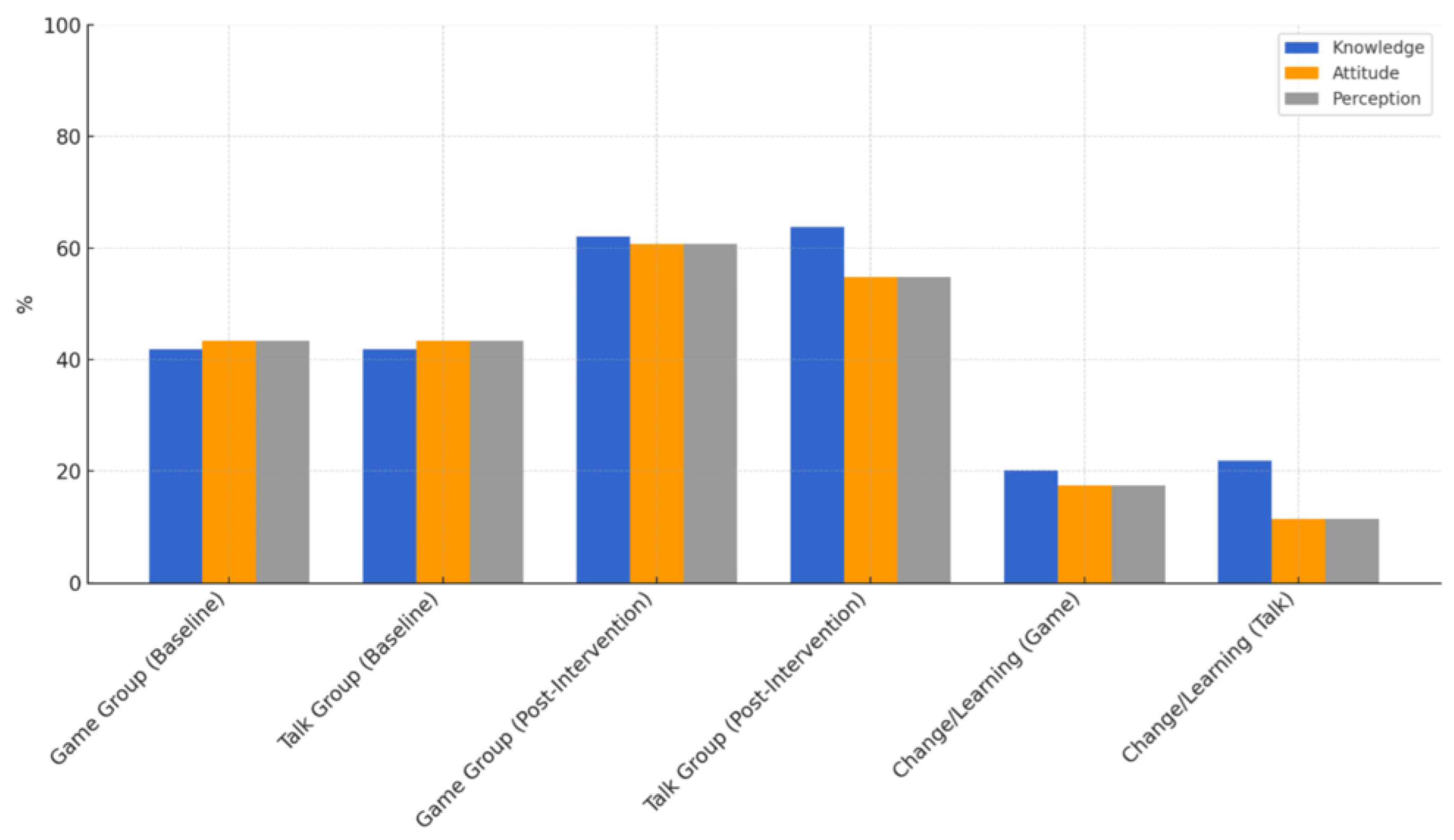

All values are expressed as percentages. The LIBOG group showed higher mean post-intervention scores in attitude and perception, and comparable gains in knowledge, while the health talk demonstrated slightly higher post-knowledge scores. The change bars (on the far right) illustrate the net gains from baseline, with the LIBOG game outperforming in affective domains (attitude and perception), indicating the potential effectiveness of interactive educational tools in shaping psychosocial learning outcomes.

Grid lines represent 10% increments to aid in visual comparison. All groupings reflect N = 80 for LIBOG, N = 61 for the Talk group, and N = 197 at baseline.

Family History of Prostate Cancer (FMH)

Knowledge became significantly associated with family history of prostate cancer (χ²(2) = 8.75, p = 0.013). 25% of those with family history had poor knowledge, 25% moderate, and 50% good knowledge, compared to 35.53% good knowledge among those without FMH.

Attitude was still not significantly associated (Attitude: χ²(2) = 1.07, p = 0.587; Perception however evened out after LIBOG: χ²(2) = 0.392, p = 0.822). 50% had a negative attitude and 25% a positive perception among those with FMH, compared to 38.96% positive perception in those without.

Family History of Breast Cancer (FHBca) attributes also evened out:

Knowledge (χ²(2) = 3.05, p = 0.217) and attitude (χ²(2) = 0.46, p = 0.793) were not statistically associated. However, perception was significantly associated (χ²(2) = 10.42, p = 0.005), with positive perception among those with FHBca at 77.78% compared to 42.25% among those without.

Family History of Ovarian Cancer (FHOca) attributes also evened out:

Knowledge remained highly significant (χ²(2) = 39.49, p = 0.000), with 100% good knowledge among the only positive case. Attitude and perception were not statistically significant, though 100% of those with FHOca had positive attitude and perception after the LIBOG intervention.

Family History of Bladder and Gastrointestinal (GIT) Cancer

Also, after the intervention, both bladder and GIT family history showed highly significant associations with knowledge (χ²(2) = 39.49 and 38.99 respectively, p < 0.001). Good knowledge among the positive case was 100%. Attitudes and perceptions did not differ significantly but shifted toward complete positivity.

After the LIBOG intervention, most of the Lifestyle Factors evened out, narrowing disparities:

Tobacco Use: No significant associations were observed (Knowledge: χ²(2) = 1.88, Attitude: χ²(2) = 1.33, Perception: χ²(2) = 0.66). The only current user had 100% good knowledge and positive attitude.

Alcohol Use: No significant associations. Good knowledge was highest among regular users (100%) and occasional drinkers (44.44%). Attitude showed 100% positivity in regular users.

Exercise Habits: Attitude approached significance but was not (χ²(6) = 11.34, p = 0.078). Positive attitude was most prominent in active exercisers (87.50%), while moderate exercisers had more negative views. Knowledge and perception showed no significant differences.

Diet Type: No significant associations were found, though higher good knowledge levels and positive attitudes were noted among vegetarians and those on fatty diets.

Regression analysis post-LIBOG: The valid odds ratios from the post-LIBOG game intervention show several statistically meaningful relationships between socio-demographic variables and the new knowledge, attitude, or perception (KAP) outcomes.

Males had significantly lower odds of demonstrating good knowledge compared to females, with an odds ratio of 0.34 (95% CI: 0.12-0.99, p = 0.047) after intervention with the LIBOG game. However, in contrast, males were significantly more likely to express a positive attitude than females, with an odds ratio of 4.16 (95% CI: 1.58-10.94, p = 0.004). Similarly, males also had significantly higher odds of having a positive perception than females, with an odds ratio of 2.79 (95% CI: 1.01-7.69, p = 0.047).

When educational background was examined, tertiary-educated participants had lower odds of good knowledge than those with only primary education (a finding that may also support a bridging of disparities by the intervention), though this difference was not statistically significant (OR = 0.53, 95% CI: 0.05-5.86, p = 0.607). Likewise, they were more likely to have a positive perception (OR = 1.89, 95% CI: 0.23-15.74, p = 0.557), though again not statistically significant.

In terms of residential setting, rural residents were more likely to demonstrate good knowledge compared to their urban counterparts, with an odds ratio of 4.39 (95% CI: 1.06-18.16, p = 0.041), a statistically significant finding. However, regarding attitude, rural residents were less likely to have a positive attitude than urban residents, with an odds ratio of 0.71 (95% CI: 0.17-2.89, p = 0.632), though this association was not statistically significant. Similarly, rural residents had slightly higher odds of a positive perception compared to urban dwellers, but the difference was not significant (OR = 1.23, 95% CI: 0.30-5.13, p = 0.776).

For family history of prostate cancer (FMH), participants with a positive family history had slightly higher odds of demonstrating good knowledge than those without (OR = 1.10, 95% CI: 0.16-7.34, p = 0.920), but the difference was not statistically significant. The same trend was seen for attitude (OR = 1.25, 95% CI: 0.19-8.33, p = 0.813) and perception (OR = 1.25, 95% CI: 0.19-8.33, p = 0.813), both showing no significant association between FMH and post-intervention improvements.

When examining family history of breast cancer (FHBca), participants with a positive history were more likely to demonstrate a positive perception, with an odds ratio of 4.80 (95% CI: 0.89-25.88), though the association approached but did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.068). This suggests a potential trend where family history of related cancers may influence perception positively after educational intervention.

Overall, the LIBOG game intervention appeared to reduce gender disparities in knowledge and significantly improve attitudes and perceptions among males. Residence and family cancer history showed varying degrees of influence, though only a few associations reached statistical significance. These findings highlight the importance of tailoring interventions to account for baseline demographic differences while demonstrating the utility of game-based education in enhancing prostate cancer screening awareness, and allied attributes,

Figure 6,

Figure 7 and

Table 4.

Knowledge, Attitude and Perception After listening to the PowerPoint health talk(HT) on prostate cancer (Post-test results).

Chi-Square Analysis post-HT:

Gender and Knowledge, Attitude, and Perception (Post-HT intervention): After the educational talk, both female and male participants demonstrated high levels of knowledge regarding prostate cancer. Among females, 62.22% had good knowledge, 2.22% moderate, and 35.56% poor. Similarly, 62.50% of males had good knowledge and 37.50% poor, with none reporting moderate knowledge. The distribution was nearly identical between sexes, and this was confirmed by a non-significant association (χ²(2) = 0.3681, p = 0.832).

Table 4 depicts the post-HT percentage changes in the KAP moieties as well.

Concerning attitude, females appeared to show stronger positivity, with 57.78% having a positive attitude compared to 43.75% of males. Negative attitudes were more prevalent in males (50%) than in females (26.67%). Despite these differences, the association between gender and attitude was not statistically significant (χ²(2) = 3.1687, p = 0.205).

Perceptions were also favorable across both genders. Positive perception was slightly higher in females (64.44%) than in males (62.50%), and the gender difference was not statistically significant (χ²(2) = 0.6066, p = 0.738). Considering the fact that the pre-interventional associations were significant, it means that the intervention had bridged the pre-exiting disparities in this aspect.

Education and Knowledge, Attitude, and Perception Post-HT

Participants with higher education levels exhibited generally better knowledge. Among those with postgraduate education, 100% had good knowledge. For tertiary-educated participants, 61.54% had good knowledge, and 36.54% had poor knowledge. The association between education and knowledge was not statistically significant (χ²(6) = 3.2371, p = 0.779). So, the talk intervention had evened out the initial disparities.

Attitudes were also largely positive across all education levels. Notably, 100% of participants with only primary education expressed a positive attitude. Tertiary-educated participants showed a balance, with 50% expressing positive attitudes, 15.38% neutral, and 34.62% negative. There was no statistically significant association (χ²(6) = 3.0481, p = 0.803). Meaning HT levelled up attitudes as well, from the baseline.

However, perception was still significantly associated with education level (χ²(6) = 13.5617, p = 0.035). All postgraduates had positive or neutral perceptions, while those with primary education had exclusively negative perceptions. The majority of tertiary-level participants (65.38%) held positive perceptions.

Ethnicity and Knowledge, Attitude, and Perception post-HT showed an evening out in the attitude and perception moieties.

Ewe participants exhibited the highest level of good knowledge (73.33%), followed by the Ga (66.67%) and Northern Ghanaian (60.00%) groups. Akan participants had a lower good knowledge rate (37.50%), and the overall association between ethnicity and knowledge remained not statistically significant (χ²(8) = 8.7651, p = 0.362).

Attitude and perception(unlike at baseline) did not differ significantly across ethnic groups (Attitude: χ²(8) = 2.5270, p = 0.960; Perception: χ²(8) = 2.1933, p = 0.975). Most groups reported a high proportion of positive attitudes and perceptions, especially among Ewe and Northern Ghanaian participants.

Residence and Knowledge, Attitude, and Perception post-HT, showed a levelling out in all the KAP components post-intervention.

Knowledge was high across all residence categories, with rural participants showing 65% good knowledge, followed by urban (59.26%) and suburban (58.33%). Unlike at baseline, no significant difference was observed (χ²(4) = 2.4627, p = 0.651).

Attitudes were most positive among suburban dwellers (66.67%), followed by urban (55.56%) and rural (40.00%) participants, although not statistically significant (χ²(4) = 4.3929, p = 0.355) unlike at baseline. Similarly, perception was highest in the suburban group (75.00%), followed by urban (62.96%) and rural (55.00%), with no significant association observed (χ²(4) = 1.5490, p = 0.818) unlike at baseline.

Family History of Prostate Cancer (FMH) post-HT showed mixed results.

There was still no significant association between FMH and knowledge (χ²(2) = 0.0679, p = 0.967), with 66.67% of those with FMH and 62.07% of those without FMH reporting good knowledge.

However, attitude and perception were significantly associated with PCa FMH. Among those with FMH, only 33.33% had a positive attitude compared to 55.17% of those without (χ²(2) = 8.1854, p = 0.017) similar to baseline. Additionally, 66.67% of those with FMH had a positive perception, compared to 63.79% of those without FMH (χ²(2) = 9.7307, p = 0.008), suggesting greater disparities in perception post-talk among participants with PCa FMH.

Lifestyle Factors (Tobacco, Alcohol, Exercise, and Diet) post-HT all experienced an evening out, suggesting a bridge in disparities by the HT across the various groups studied.

Tobacco use did not show any statistically significant relationship (unlike at baseline) with knowledge (χ²(2) = 0.6154, p = 0.735), attitude (χ²(2) = 0.8626, p = 0.650), or perception (χ²(2) = 2.0842, p = 0.353). Former users and never-users had comparable proportions of positive views.

Alcohol use also showed no significant association with knowledge (χ²(2) = 2.3787, p = 0.304), attitude (χ²(2) = 0.7925, p = 0.673), or perception (χ²(2) = 3.7983, p = 0.150) unlike at baseline. However, those who never drank were slightly more likely to exhibit good knowledge and positive perceptions.

Unlike at baseline, Exercise frequency was not significantly associated with any of the three outcome measures (Knowledge: χ²(6) = 3.6731, p = 0.721; Attitude: χ²(6) = 8.3929, p = 0.211; Perception: χ²(6) = 3.8248, p = 0.700). Positive attitudes were most common among participants engaging in light exercise (72.73%).

Diet type also showed no significant associations (Knowledge: χ²(4) = 0.2549, p = 0.993; Attitude: χ²(4) = 2.4807, p = 0.648; Perception: χ²(4) = 0.4167, p = 0.981) unlike at baseline, though vegetarians had consistently higher levels of good knowledge and positive attitudes.

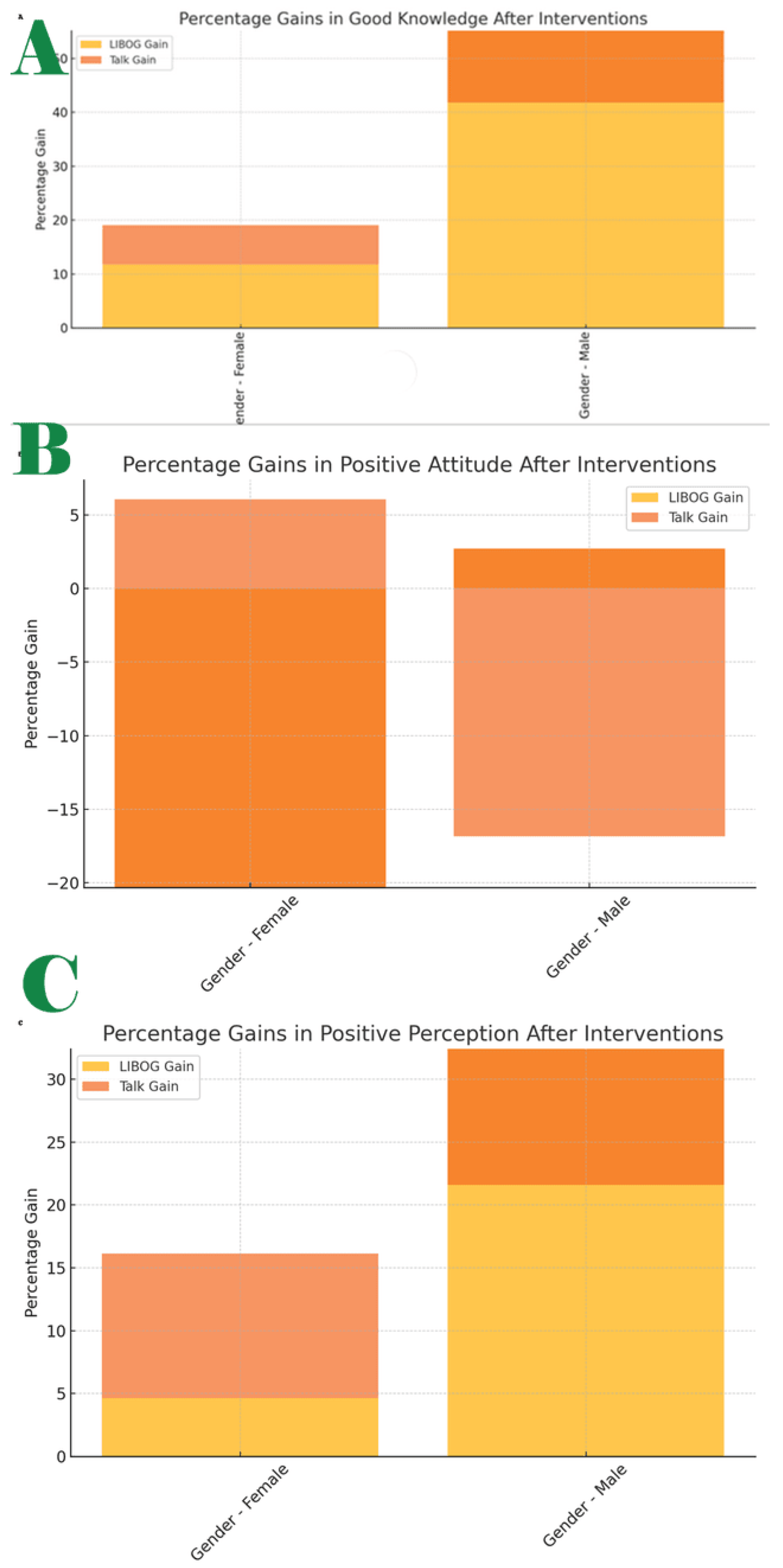

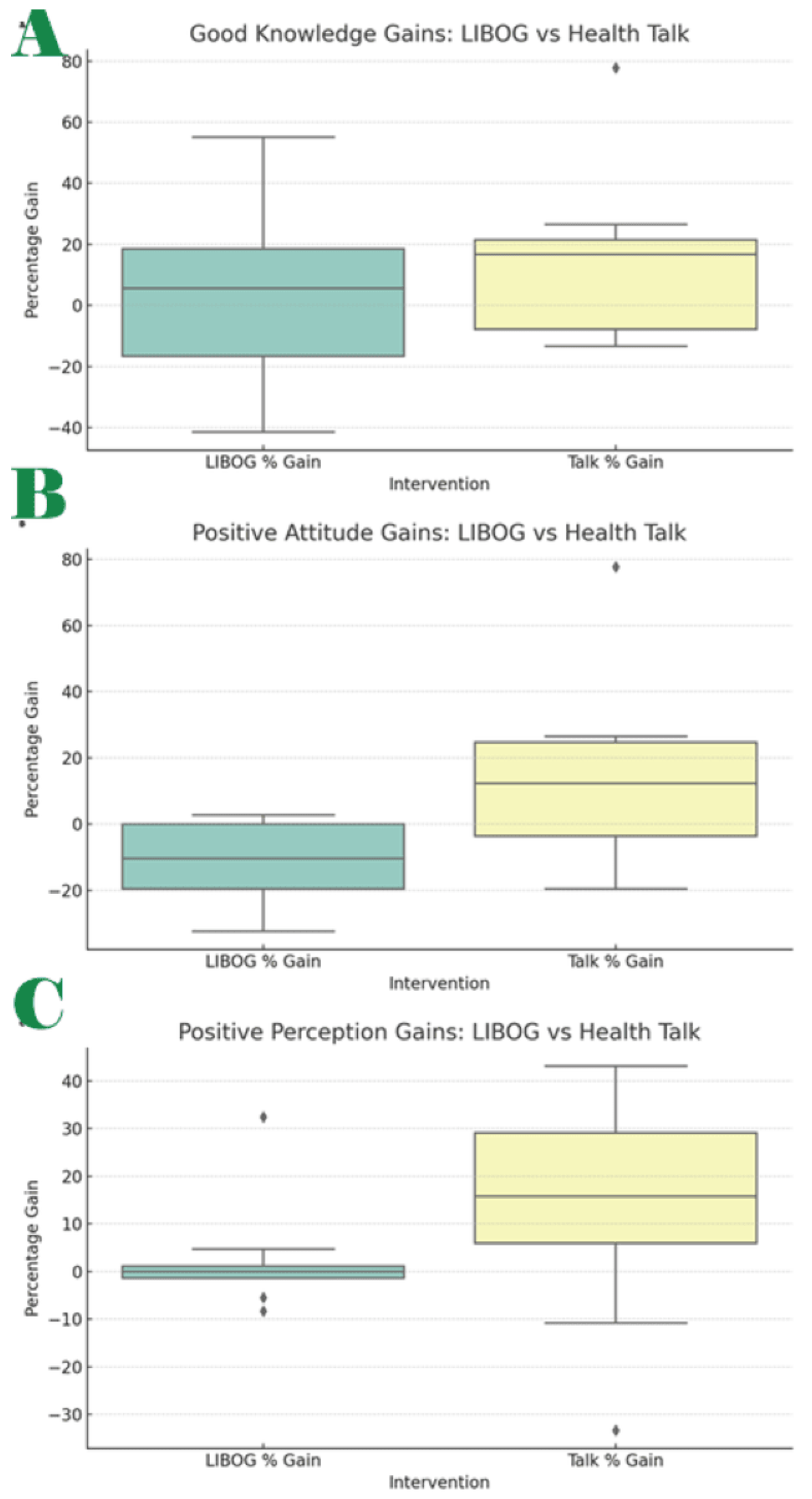

Figure 8 A to C and

Figure 9 showcase some of these post-interventional shifts.

Regression analysis post-HT: Following the prostate cancer health talk (intervention 2), several odds ratio analyses were conducted to examine relationships between key demographic and familial variables and the likelihood of demonstrating good knowledge, a positive attitude, or a positive perception post-HT.

In terms of knowledge, the odds of having good knowledge among males were virtually identical to those among females, with an odds ratio of 1.01 (95% CI: 0.36 to 2.81, p = 0.982). This indicates no significant gender-based difference in knowledge acquisition, and a levelling up after the intervention.

When examining attitude, males were less likely than females to have a positive attitude, with an odds ratio of 0.52 (95% CI: 0.19 to 1.42, p = 0.204). However, this difference was not statistically significant. Similarly, the odds of having a positive perception were slightly lower among males compared to females, with an odds ratio of 0.92 (95% CI: 0.33 to 2.57, p = 0.873), again showing no significant difference (bridged disparities after HT exposure).

Turning to family history of prostate cancer, participants with such a history had lower odds of expressing a positive attitude than those without, with an odds ratio of 0.41 (95% CI: 0.11 to 1.50, p = 0.177). While suggestive of a trend, this finding did not reach statistical significance. For perception, individuals with a family history of prostate cancer had marginally higher odds of expressing a positive perception compared to those without such history, with an odds ratio of 1.22 (95% CI: 0.33 to 4.54, p = 0.764), but this too was not statistically significant.

Overall, these results suggest that the educational intervention had a broadly equalizing effect across gender and family history subgroups, with no significant disparities observed in knowledge, attitude, or perception outcomes.

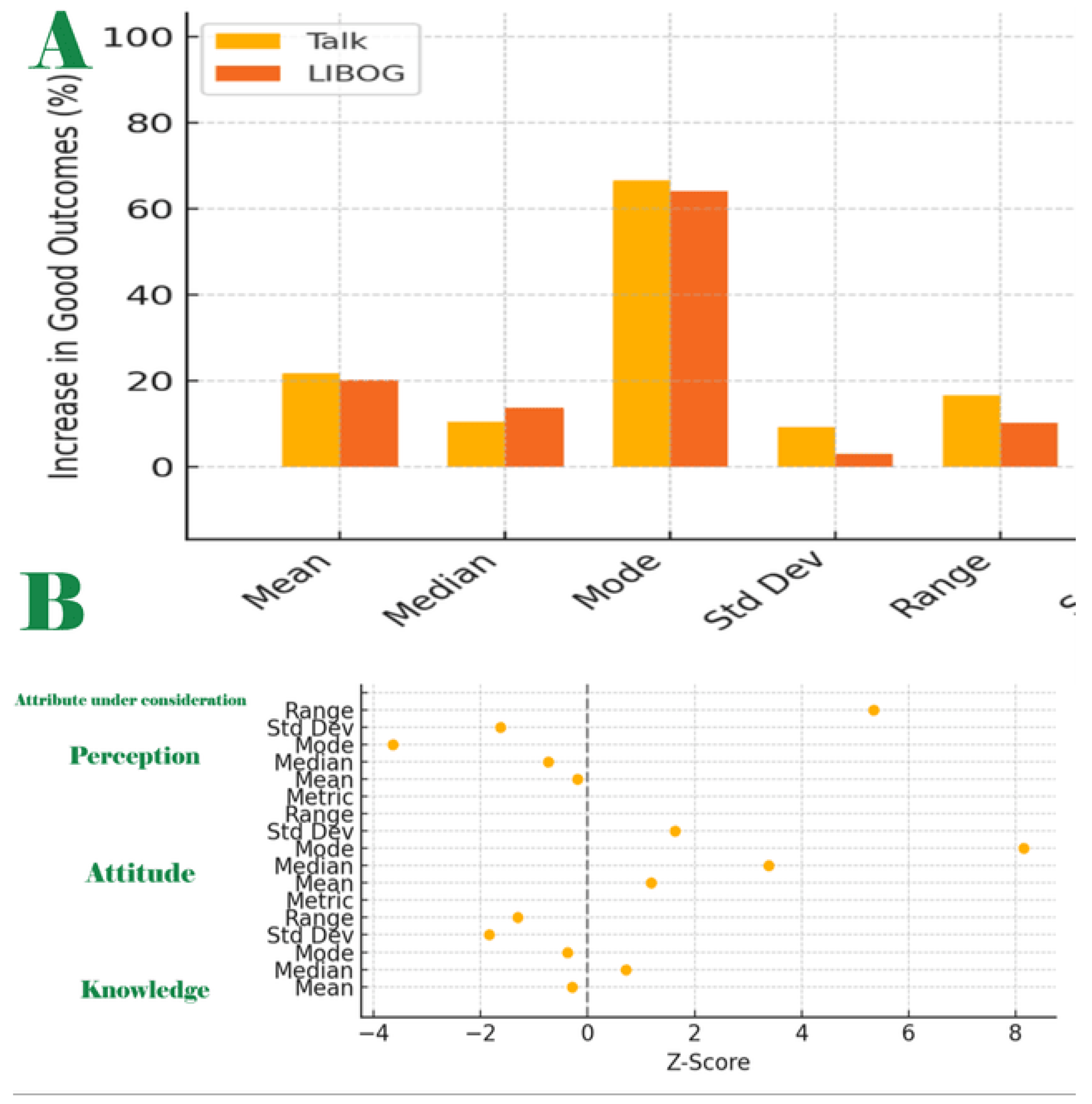

Differences in Knowledge Attitude and Perception between Baseline and Final for Both LIBOG and Health Talk:

The final output table presents a comparative analysis of baseline and post-intervention performances across three outcome domains: Knowledge, Attitude, and Perception, following two different educational interventions: a standard health talk (HT), and an interactive LIBOG game. It organizes the metrics into statistical descriptors (mean, median, mode, standard deviation, range) and tracks the percentage of participants with good and poor outcomes before and after interventions. It further includes absolute changes from baseline (improvements), Relative performance of LIBOG vs Talk, and Tests of statistical significance (Z-tests and p-values). See

Table 5,

Table 6,

Table 7 and

Table 8;

Figure 10A and B.

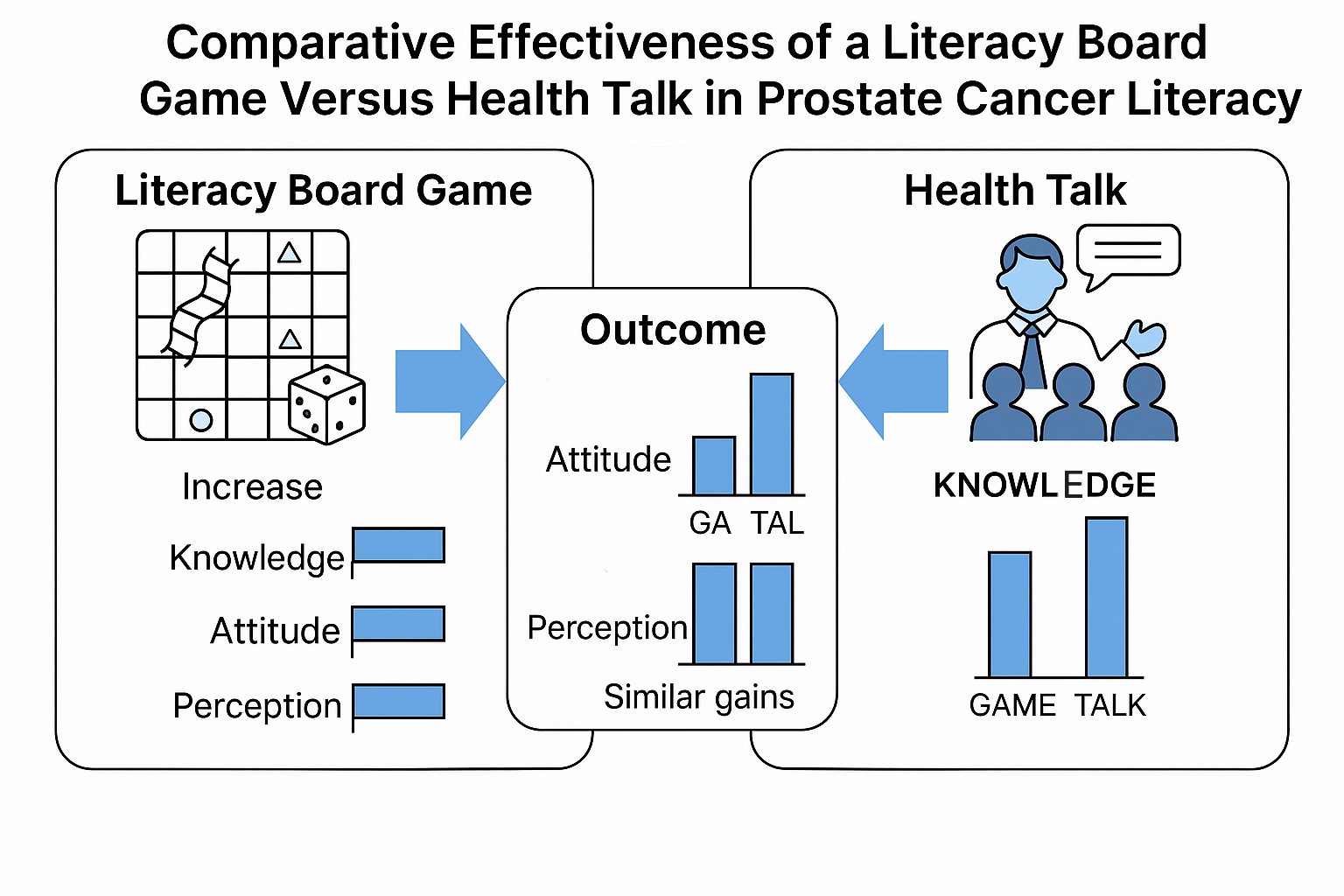

Key Insight: Both interventions significantly improved good knowledge outcomes (

Table 5 and

Table 6). LIBOG and Talk showed comparable effectiveness overall, with health talk slightly edging LIBOG in mean gain but LIBOG showing a steadier median and smaller variability. However, no statistically significant difference was found between the LIBOG and Talk improvements (all p > 0.05). The two are comparable. LIBOG compared favorably with HT in the knowledge moiety.

Key Insight: The LIBOG game led to larger gains in attitude (

Table 5 and

Table 7), especially in mode and mean values, with a statistically significant difference observed for the modal value (z = 3.85, p < 0.001). The range analysis suggests LIBOG also reached more individuals at the extremes (better outcomes for some), despite slightly higher variability. LIBOG may be superior in modifying the attitude moiety.

Perception Domain: baseline, post-LIBOG and post-HT; mean, median, mode, range, standard deviation and statistically significant differences.

Perception metrics were also analyzed separately. The LIBOG intervention demonstrated positive perception shifts that outperformed the Talk intervention (

Table 5).

Comparison by Aggregates

Aggregates of HT gains: The health talk intervention yielded notable improvements in both positive and negative KAP attributes across all three domains:

Knowledge: Improvement in good knowledge levels : Total improvement was 125.11%, averaging 25.02% across the five statistical measures.

Reduction in poor knowledge level: An even more substantial improvement was observed here, with a total of 229.72%, averaging 45.94%.

Overall (Final) Aggregate Score: 354.83%, translating to an average of 35.48% improvement in the knowledge domain.

Attitude:

Improvement in Positive Attitude: Total = 69.51%, Average = 13.90%

Reduction in Negative Attitude: Total = 226.97%, Average = 45.39%

Final Aggregate: 296.48%, Average = 29.64%

Perception:

Improvement in Positive perception: Total = 100.45%, Average = 20.09%

Reduction in Negative perception: Total = 75.01%, Average = 15.00%

Final Aggregate: 175.46%, Average = 17.55%

Overall (Grand Totals) for Health Talk

Positive Improvements Total: 295.07% (Average: 19.67%)

Negative Reductions Total: 531.70% (Average: 35.45%)

Combined Grand Total: 826.79%, yielding a grand average of 27.56% across all KAP domains and demographic strata (

Table 9).

Aggregates for LIBOG Game Intervention:

The LIBOG board game intervention, which emphasizes interactivity and participation, also demonstrated strong gains, especially in attitude and perception:

Knowledge:

Improvement in Positive knowledge: Total = 111.52%, Average = 22.30%

Reduction in Negative knowledge: Total = 122.65%, Average = 24.53%

Final Aggregate: 234.17%, Average = 23.47%

Attitude:

Improvement in Positive Attitude: Total = 122.43%, Average = 24.49%

Reduction in Negative Attitude: Total = 116.91%, Average = 23.38%

Final Aggregate: 239.34%, Average = 23.93% (

Table 10)

Perception:

Improvement in Positive perception: Total = 91.66%, Average = 18.33%

Reduction in Negative perception: Total = 26.04%, Average = 5.21%

Final Aggregate: 117.0%, Average = 11.77%

Overall (Grand Totals) for LIBOG Game

Positive Improvements Total: 325.61%, Average = 21.70%

Negative Reductions Total: 262.94%, Average = 17.53%

Combined Grand Total: 588.56%, with a grand average of 19.61% across all domains and parameters.

Table 11.

Comparative Insights LIBOG vs HT.

Table 11.

Comparative Insights LIBOG vs HT.

| Dimension |

Health Talk Avg. (%) |

LIBOG Avg. (%) |

Difference |

| Knowledge |

35.48 |

23.47 |

HT leads by 12.01 pts |

| Attitude |

29.64 |

23.93 |

HT leads by 5.71 pts |

| Perception |

17.55 |

11.77 |

HT leads by 5.78 pts |

| Grand Avg. |

27.56 |

19.61(71% of HT’s) |

HT leads by 7.95 pts |

While both interventions were effective, the health talk consistently produced higher percentage improvements and reductions, especially in knowledge and attitude domains. However, the LIBOG game still showed appreciable gains, particularly in affective and perceptual areas, and may offer benefits in engagement and longer-term behavioral reinforcement.

in the final analysis, HT leads by 7.95% points overall ahead of LIBOG: is the difference statistically significant?

Statistical Test: Difference Between Proportions

To assess whether the observed difference in overall grand average performance between the Health Talk (HT) group and the LIBOG group is statistically significant, a Z-test for two proportions was performed.

Input Values:

Health Talk Mean (p₁): 27.56% → 0.2756

LIBOG Mean (p₂): 19.61% → 0.1961

Sample Size (HT): 61

Sample Size (LIBOG): 80

Difference in Means: 7.95 percentage points

Test Output: Z-score = 1.11, p-value = 0.267

Interpretation:

The observed advantage of the Health Talk group (+7.95%) over the LIBOG group is not statistically significant at the conventional 5% threshold (p = 0.267). While numerically higher, the difference in average overall gains could plausibly be due to random variation given the sample sizes involved.

Finally, to cross-check, the Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Test with the Objective of determining whether there is a statistically significant difference (in medians) between the effectiveness (in percentage gain) of two paired educational interventions: LIBOG Game and Standard Health Talk, was conducted.

The test was conducted on the assumptions that each pair of values represents the percentage gain in knowledge, attitude, or perception for the same subgroup across both interventions. It was based on the assumptions that:

The data are paired and come from the same population. The paired differences are continuous and symmetrically distributed around the median. The dependent variable (here, percentage gain) is ordinal or continuous and The observations are mutually independent.

The Null Hypothesis (H₀) that the test was based on stated that:

There is no difference in median percentage gains between LIBOG and Health Talk.

H₀: median (LIBOG - Talk) = 0

The test was conducted to involve all 14 sociodemographic parameters, over both sets of:

Good and Poor Knowledge Gains, Good and Poor Attitude Gains, Good and Poor Perception Gains; across 25 subgroup comparisons, the test results were:

Test Statistic (W) = 102.0, p-value = 0.107.

Interpretation: Since p = 0.107 > 0.05, we failed to reject the null hypothesis.

There is no statistically significant difference in the overall effectiveness of the LIBOG Game vs the Health Talk when combining all domains and subgroup improvements (

Table 12 and

Figure 11).

Evaluation of the three hypotheses we started with: The study’s null hypotheses were:-

Hypothesis 1:There is no difference in the proportion of participants with good knowledge of prostate cancer before and after a standard health talk intervention. We reject this hypothesis, as baseline versus post - HT differences between mean-proportions of those with a ‘good knowledge level’ had a test statistic of (z = 3.10, p = 0.002). This suggests that there was an improvement that was statistically significant (and indeed this statistically significant difference was observed in a total of 16 out of the 24 measures of central tendency and dispersion for baseline versus post-HT metrics).

Hypothesis 2:There is no difference in the proportion of participants with good knowledge of prostate cancer before and after the session of interaction with the LIBOG game. We reject this hypothesis, as baseline versus post - LIBOG differences between mean-proportions of those with a ‘good knowledge level’ had a test statistic of (z = 2.85, p = 0.004). This suggests that there was an improvement that was statistically significant (and indeed this statistically significant difference was observed in a total of 14 out of the 24 measures of central tendency and dispersion for baseline versus post-LIBOG metrics).

Hypothesis 3:There is no difference in the median percentage gains between LIBOG and Health Talk interventional groups in the study. We fail to reject this statement as the Test Statistic across all the KAP domains (over all the 14 sociodemographic and lifestyle characteristics), the Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Statistic (W) was 102.0, p-value = 0.107. It means that the two interventions are comparable in effectiveness. LIBOG compares favorably with HT. Since it actually offers us at least 71% of the grand gains attributable to HT in this study, it is not an inferior modality for health literacy.

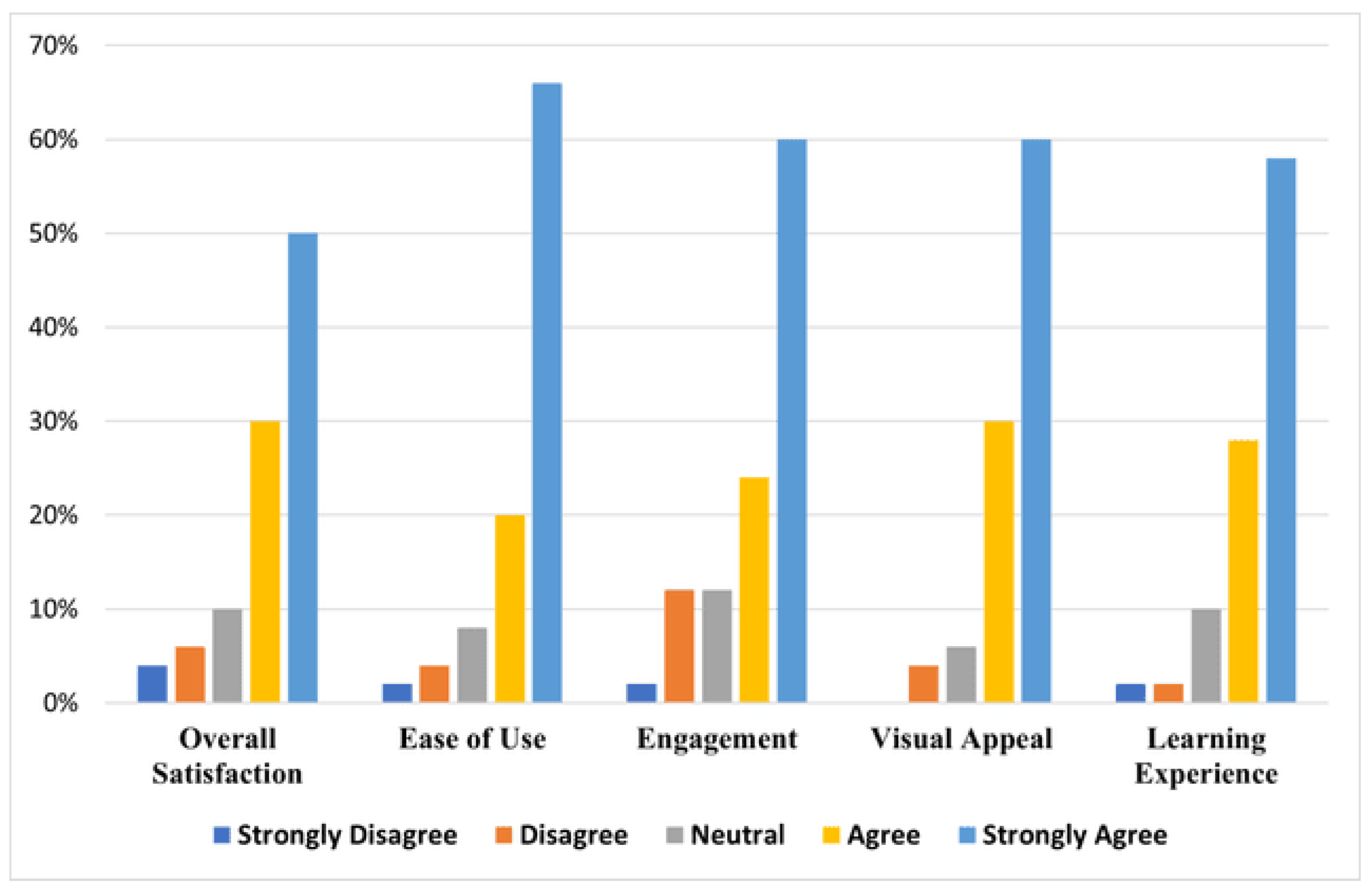

Literacy Game Usability Testing: The usability testing also showed that at least a total of 80% of all users of the LIBOG game agreed or strongly agreed that it was easy to use, engaging, had a good visual appeal, and gave them good satisfaction and learning experience (

Figure 12).

The Likert Scale-based questionnaires for the main study and the Post Usability Testing for the LIBOG is presented in

Table 13 under the Appendix Section of this paper.

Important Resources:

1. The drive to the prostate cancer S-S-LIBOG and its manuals are on the following links:

THE 18 LIBOGS(jpegs)

THE 18 LIBOGS (PDF): These includes S-S-LIBOGs on Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health, Asthma, Antimicrobial Resistance, Breast cancer, Breastfeeding/Breastfeeding Hospital Initiative, Cervical cancer, Diabetes Mellitus, Hypertension, Family Planning, Hematuria and Bladder cancer, Kidney diseases, Male Circumcision Complications, Malnutrition (in children), Mental health, Menstrual Health, Prostate cancer, Sickle Cell Disease.

THE MANUALS FOR THE 18 LIBOGS

2. The prototype digital version of the LIBOG is available on the following link:

3. The standard PowerPoint slides used for the HT are available on the following link:

4. Health Talk Guides for the other 16 diseases.