1. Introduction

Spotty Liver Disease (SLD) is an infectious disease of poultry that causes multifocal whitish-gray liver lesions and is associated with high mortality and egg-production losses [

1,

2]. First described more than half a century ago, SLD was nonetheless only sporadically reported in laying hens in the United States and Europe (often described as a "vibrionic hepatitis" or similar syndrome) prior to falling largely out of attention for many decades [

3]. In recent years, however, SLD has re-emerged as an economically important disease in egg-production systems worldwide. Outbreaks can lead to flock mortalities approaching 10-15% and egg-production losses of up to 35%. The impact is especially severe in free-range and cage-free layer operations, where SLD now occurs with a higher frequency. Field reports and surveys are strongly suggestive that flocks provided outdoor access or floor housing are at increased risk for SLD compared to caged layer flocks [

4]. Indeed, the industry trend toward free-range management has coincided with the re-emergence of SLD outbreaks in countries such as Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States [

3]. The disease thus represents a significant threat to the health and productivity of commercial layer chickens, underscoring the need for further research into its causes and control measures.

The causative agent of SLD was not determined until the 2010s. Early studies had reported the presence of

Campylobacter-like organisms within the livers of compromised chickens, but positive identification was elusive. It was only in 2015 that Crawshaw et al. isolated a novel thermophilic

Campylobacter from diseased hens in the United Kingdom [

5,

6]. Shortly thereafter, Van et al. in Australia recovered and described a similar bacterium from layers suffering from SLD and officially designated it as

Campylobacter hepaticus in 2016 [

7,

8]. These studies marked a major breakthrough in understanding the causative agent of SLD. Subsequent experimental infections confirmed that oral challenge of healthy hens with pure cultures of

C. hepaticus produced characteristic liver lesions and disease, with re-isolation of the bacterium from liver and bile [

8,

9]. Notably,

C. hepaticus has extensive invasiveness in vitro, shows the capacity to enter and survive within chicken hepatocyte cell cultures, and develops disease within several days of being introduced to susceptible hens [

8]. By 2018, the organism had been recovered on several continents, including from Australian free-range flocks experiencing outbreaks and the first documented instances in the United States [

10]. The establishment of

C. hepaticus as the causative agent of SLD ended a long-running enigma and categorized SLD as a bacterial disease, thus enabling directed research into its pathogenesis and epidemiology.

Although

C. hepaticus has been identified as the causative agent of SLD, its pathogenesis remains poorly understood. It is further complicated by its fastidious, slow-growing nature, requiring precise microaerobic conditions, narrow temperature ranges (growing at 37–42 °C but not at 25 °C), and prolonged incubation times of 3 to 7 days for visible colony formation [

11]. Unlike

C. jejuni or

C. coli, which colonize poultry relatively harmlessly,

C. hepaticus causes severe disease in layer chickens. Although it has been isolated from the liver, bile, intestines, caeca, and cloacal swabs of infected chickens, the specific mode of dissemination to the liver is unclear. [

12]. Histopathologic analyses reveal necrotic hepatitis with associated inflammatory infiltrates [

1,

13]. Nevertheless, the bacterial components responsible for initiating this reaction remain unclear. The specific bacterial components responsible for necrotic hepatitis accompanied by inflammatory infiltrates observed in histopathological analyses are also not clear. Notably,

C. hepaticus lacks many of the typical classical virulence and stress-response genes possessed by other species of

Campylobacter, including the cytolethal distending toxin (CdtA/B/C) cluster and multiple iron acquisition systems, thus possibly relying on alternative strategies, such as metabolic adaptation or immune evasion, to establish infection [

3,

12]. Observational field data indicate that stressors associated with the flock, such as competition for nest space and delay in egg production, often occur before the outbreak and highlight the possible role of host factors in the pathogenesis of the disease [

14]. Key questions remain about the processes by which

C. hepaticus survives, transmits itself, and causes disease within its host.

Recent genomics and transcriptomics studies have begun to elucidate the biology of

C. hepaticus. Its genome is notably smaller (approximately 1.5 Mb, G+C ~28%) than the genomes of other species of

Campylobacter [

15,

16], suggesting a characteristic diminution in genomic content adapted to the chicken liver environment [

9]. Transcriptomic profiling has also provided insights into how

C. hepaticus survives in vivo. Van et al. demonstrated that, in comparison to in vitro culture, bacteria recovered from infected bile upregulate genes associated with stress response, nutrient acquisition, and metabolism, such as glucose metabolism, hydrogen metabolism, and sialic acid modification [

12]. These results imply metabolic adaptation and stress tolerance are critical for

C. heapticus survival in the bile during infection. The study was, however, restricted to bile vs. Brucella broth media, and bacterial gene expression in other environmental niches is yet to be investigated.

To fill this gap, we undertook RNA-sequencing of C. hepaticus in three host-relevant niches: bile, chicken liver hepatocellular carcinoma epithelial (LMH) cells, and infected liver tissue collected from SLD chickens. By comparing C. hepaticus gene expression in these host-relevant niches to that of bacteria grown in standard microaerophilic conditions in culture media (control), we aimed to identify niche-specific gene expression patterns contributing to virulence, metabolism, and stress adaptation. This work provides the first in-depth transcriptomic map of C. hepaticus across infection-relevant environments and yields new insights into SLD pathogenesis and targets for the development of control measures.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial Strain and Culture Conditions

Campylobacter hepaticus strain NCTC 13823T (The National Collection of Type Cultures (NCTC), Porton Down, Salisbury, UK) was grown on Thermo Scientific Columbia Agar with 5% Sheep Blood (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA) under microaerophilic conditions using Mitsubishi AnaeroPack-MicroAero gas generator (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) at 37°C in an airtight chamber for 48 to 72 hours to facilitate optimum growth of the bacteria. Following incubation, well-isolated colonies were carefully picked and resuspended in Remel Brucella Broth (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Lenexa, KS, USA) to achieve a homogeneous bacterial suspension. This suspension was centrifuged to harvest bacterial cells as a pellet. Total RNA extracted from bacterial pellets was used as a control for transcriptomic analysis. Bacterial suspension containing 1 x 108 CFU/mL of C. hepaticus used for in vitro inoculation experiments.

2.2. In Vitro Exposure of C. hepaticus to Chicken Bile

To mimic the biliary environment, C. hepaticus was resuspended in sterile-filtered bile collected from apparently healthy C. hepaticus-free commercial layer chickens and incubated at 37 °C under microaerophilic conditions using Mitsubishi AnaeroPack-MicroAero gas generator (Thermo Fisher Scientific) in a leak-proof container for 72 hours. After incubation, the solution was centrifuged to pellet both bacterial cells and bile components. The pellet was then stored in RNAlater (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Lenexa, KS, USA) for RNA stabilization, at –80 °C until total RNA extraction.

2.3. Chicken Liver Hepatocellular Carcinoma Epithelial Cells (LMH) and Infection

Chicken liver hepatocellular carcinoma epithelial cells (LMH; CRL-2117, Manassas, VA, USA) were cultured in Waymouth’s medium (Waltham, MA, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Atlanta Biologicals, Flowery Branch, GA, USA) and maintained at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO₂. For infection assays, LMH cells were seeded into T75 flasks (Corning Life Sciences, Tewksbury, MA, USA) pre-coated with 0.1% gelatin (Cell Biologics, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and allowed to grow until confluent monolayers were established [

17]. Cells were then infected with C. hepaticus and incubated for 12 hours under the same culture conditions. After incubation, the infected monolayers were gently washed with sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), harvested by centrifugation, and the resulting pellets were stored in RNAlater (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Lenexa, KS, USA) at –80 °C until total RNA extraction.

2.4. Liver Sample Collection from Spotty Liver Disease (SLD) Infected Chicken

Liver samples were collected from commercial layer chickens during the course of a confirmed SLD outbreak under the direction of a poultry extension veterinarian. The flock had a documented history of SLD. All affected chickens were 31 weeks of age and at peak egg production. The flock was experiencing increased mortality, and characteristic white foci on the surfaces of the livers were observed on necropsy. Liver tissues containing white foci were collected and preserved immediately in RNAlater. Samples were stored at –80 °C until total RNA extraction was performed.

2.5. RNA Extraction, rRNA Depletion, and mRNA Enrichment

Total RNA was extracted using the RiboPure RNA Purification Kit (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA). In the case of LMH cells and liver tissue samples, bacterial RNA was selectively enriched with the MICROBEnrich Kit (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA) to deplete host RNA. All samples were then subjected to rRNA depletion to enrich bacterial mRNA with the MICROBExpress Bacterial mRNA Enrichment Kit (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA). All processes were performed following the manufacturer's instructions. RNA quality and quantity were determined at each step with a Qubit 4.0 Fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Wilmington, DE, USA).

2.6. Transcriptome Library Preparation, Sequencing, and Differential Gene Expression Analysis

Approximately 100 ng of enriched bacterial mRNA from each sample was used for cDNA library construction using the TruSeq Stranded mRNA Library Prep Kit (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). The mRNA was enzymatically fragmented and used for synthesis of first- and second-strand cDNA. The resulting double-stranded cDNA fragments were adenylated at the 3' ends and ligated with TruSeq RNA Combinatorial Dual Index Adapters (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, USA), followed by PCR amplification to enrich the libraries. The indexed cDNA libraries were multiplexed and clustered across two lanes of a flow cell, and sequencing was performed using the Illumina NovaSeq X Series (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) platform. Raw RNA sequencing data were processed using the CLC Genomics Workbench V.25.0.2 (Qiagen, Redwood City, CA, USA). Adapter sequences and low-quality reads (Phred score < 30) were removed. Cleaned reads were mapped to the C. hepaticus UF2019SK1 reference genome (NCBI Genome Assembly: ASM1577487v1). Differential gene expression (DGE) analysis was conducted to compare transcriptomic profiles across bile-exposed, LMH-infected, and liver-derived samples. Genes were considered differentially expressed, following the criteria outlined in the previous studies, when they exhibited a p-value < 0.01, a false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05, and a fold change (FC) > 2 [

18,

19]. All experimental conditions were tested in triplicate (i.e., three biological replicates per condition).

2.7. Data Availability

The transcriptomic profile data (raw and processed) described in this study were deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database in NCBI under accession number …….. (waiting for the accession number).

3. Results

3.1. Overall Transcriptomic Response of C. hepaticus Across Different Host-Associated Environments

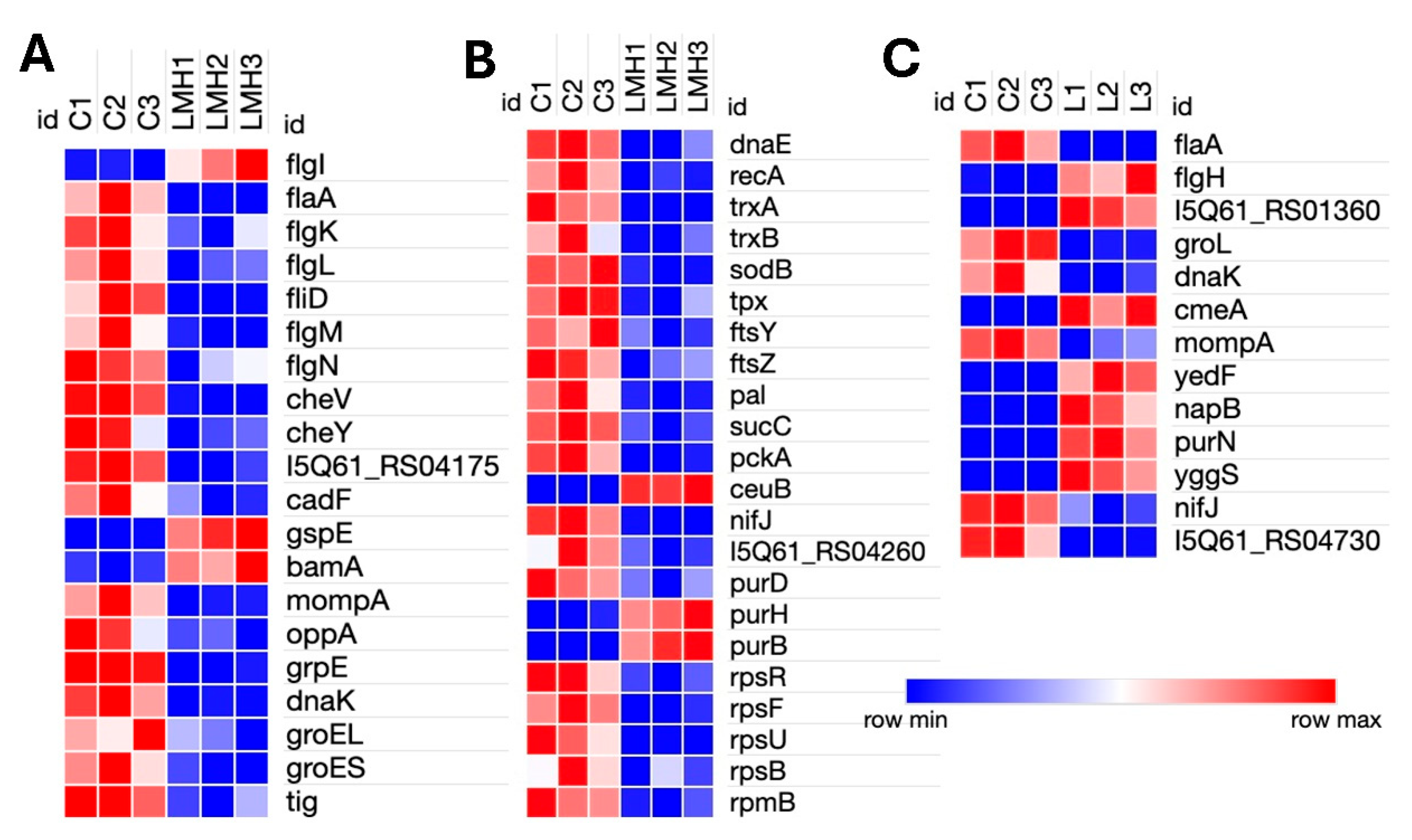

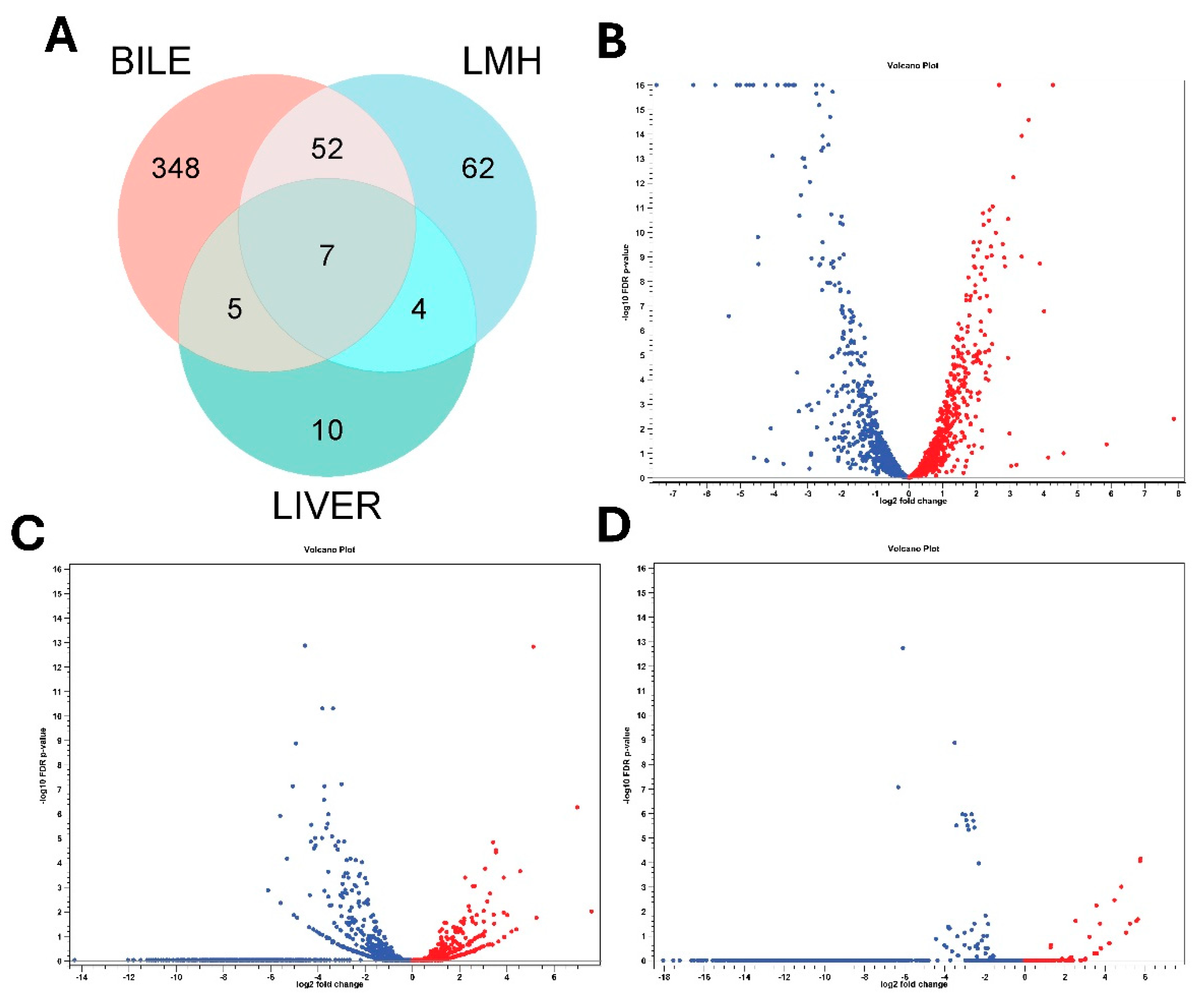

Transcript reads obtained under all three conditions (in vitro bile, LMH infection and SLD infected liver samples) mapped with high rates to the C. hepaticus reference genome, C. hepaticus UF2019SK1 reference genome (NCBI Genome Assembly: ASM1577487v1), providing strong transcriptome coverage, between 98.7%–99.8% for bile samples, 99.3%–99.6% for LMH samples, and 99.3% for liver samples. RNA Integrity Number (RIN) values of 6 to 7 for all samples confirmed the quality and integrity of the RNA. Differential expression analysis uncovered unique transcriptional responses. Supplementary File S1 provides detailed, unfiltered differential gene expression profiles for each condition. After applying filtration parameters, the bile showed 412 DEGs, with 189 were upregulated and 223 downregulated. In LMH cells, 125 DEGs were found, of which 29 were upregulated and 96 were downregulated, suggesting a shift toward a low-activity intracellular state. In liver tissue, 26 DEGs were found, including 9 upregulated and 17 downregulated, indicative of ongoing adaptation during infection. Of these, only seven genes were consistently differentially expressed across all three niches, all of which were downregulated. These included flaA, groEL, rrf1, rrf2, rrf3, ssrA, and a DUF2910 family protein I5Q61_RS04730 (

Figure 1A). These results underscore the dynamic transcriptional reprogramming of C. hepaticus to accommodate various host environments. Volcano plots showing the differential gene expression patterns are presented in

Figure 1B–D, while heat maps of gene expression profiles are provided in Supplementary

Figures S1–S3.

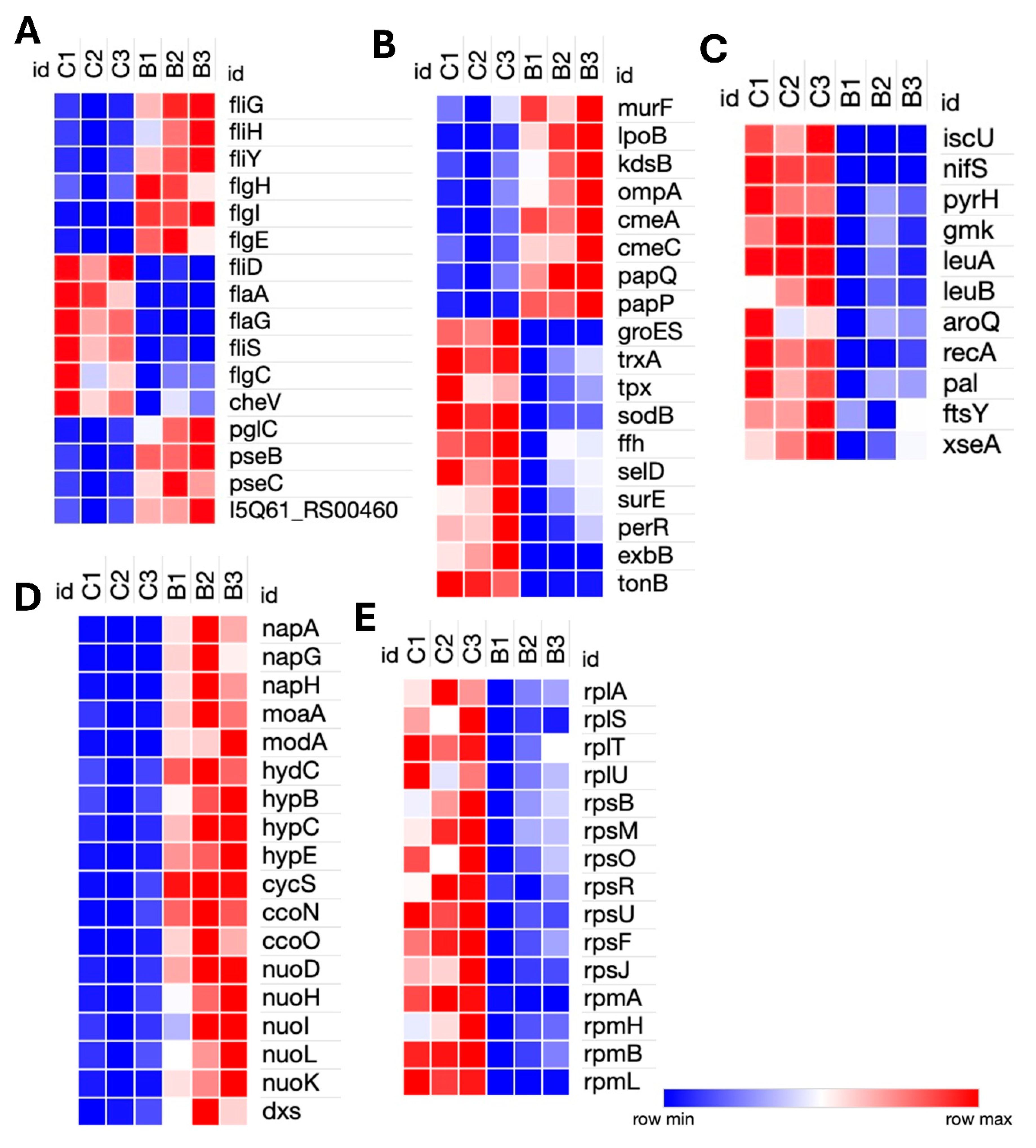

3.2. Transcriptomic Response of C. hepaticus to Bile Exposure

Genes relating to surface structure modification and glycosylation, such as pglC, pseB, pseC, and motility-associated glycosyltransferases (I5Q61_RS00460), were upregulated in bile. Motility genes showed differential regulation; components of the flagellar motor and assembly machinery, such as fliG, fliH, fliY, flgH, flgI, and flgE, were upregulated, while structural and filament-associated genes, including flaA, flaG, fliD, fliS, and flgC, were downregulated. The chemotaxis gene cheV was also downregulated, indicating a potential suppression of environmental sensing and directional motility (

Figure 2A). Upregulation of murF and lpoB (peptidoglycan biosynthesis), and kdsB (lipopolysaccharide core biosynthesis) reflects a strengthening of the cell envelope. Expression of an ompA family outer membrane protein

(I5Q61_RS03650

) was modulated, potentially to alter membrane permeability or surface antigenicity. Notably, the genes involved CmeABC multidrug efflux system, cmeA and cmeC, as well as ABC transporters papP and papQ

, were significantly upregulated, indicating activation of defense mechanisms against bile and other stressors (

Figure 2B).

Genes associated with energy metabolism were broadly induced. These included dxs (isoprenoid biosynthesis), napA, napG, and napH (components of the periplasmic nitrate reductase complex involved in anaerobic nitrate respiration and iron-sulfur electron transfer), moaA and modA (molybdenum cofactor biosynthesis), and hydC, hypB, hypC, and hypE (hydrogen metabolism genes). Components of the electron transport chain, including cycS, ccoN, ccoO, and NADH dehydrogenase subunits, nuoD, nuoH, nuoI, nuoK, and nuoL, were also upregulated, suggesting a shift toward alternative respiratory strategies under bile-induced stress. Conversely, genes involved in several key cellular pathways, including stress response genes (groES, trxA, tpx, sodB, ffh, selD, surE, and perR), membrane transporters (exbB and tonB), and iron-sulfur cluster biogenesis genes (iscU and nifS) were downregulated. Nucleotide biosynthesis genes (pyrH and gmk), branched-chain and aromatic amino acid biosynthesis genes (leuA, leuB, and aroQ) were also repressed. There was a general downregulation of transcriptional and translational machinery, with numerous ribosomal protein genes (rplA, rplS, rplT, rplU, rpsB, rpsF, rpsJ, rpsM, rpsO, rpsR, rpsU, rpmA, rpmB, rpmH, and rpmI) downregulated, indicating reduced protein synthesis. DNA repair (recA and xseA) and cell division genes (pal and ftsY) were also downregulated, indicating an overall reduction in cellular replication and maintenance activities (Figures 2C and 2D). Additionally, a significant number of the highly upregulated or downregulated genes encode hypothetical proteins, whose functions have not yet been ascertained.

3.3. Transcriptomic Adaptation of C. hepaticus During In Vitro LMH Cell Infection

Transcriptomic analysis of C. hepaticus-infected LMH cells identified 125 DEGs, including 29 upregulated and 96 downregulated genes. Motility genes had opposing patterns of expression, where flgI (flagellar basal body) was upregulated, while structural elements (flaA, flgK, flgL, and fliD) and regulators (flgM and flgN) were downregulated. Chemotaxis-related genes (cheV, cheY, and methyl-accepting chemotaxis protein, I5Q61_04175) were downregulated. Among secretion system genes, gspE (type II secretion system protein) and bamA (outer membrane assembly) were upregulated, and mompA (major outer membrane protein) was downregulated. The ceuB iron transport gene was upregulated, but nifJ (pyruvate metabolism) and the iron-sulfur cluster assembly gene I5Q61_RS04260 were downregulated. Protein folding chaperone genes, such as grpE, dnaK, groES, groEL, and tig, were markedly downregulated. The purine biosynthesis genes had mixed expression levels; notably, purH and purB were upregulated, whereas purD was downregulated. Several genes participating in basic cellular processes, including ribosomal proteins (rpsR, rpsF, rpsU,rpsB, and rpmB), DNA repair (dnaE and recA), and the ABC transporter (oppA), were downregulated as well. Furthermore, antioxidant defense genes (sodB, tpx, trxA, and trxB), essential metabolic enzymes (sucC and pckA), the adhesion gene cadF, and the division genes ftsZ, ftsY, and pal were downregulated. Such patterns of expression are indicative of C. hepaticus assuming a persistent intracellular, low-metabolic state when infecting LMH cells.

3.4. Transcriptomic Analysis of C. hepaticus Isolated from Infected Livers

Transcriptomic analysis of C. hepaticus isolated from liver tissue identified 26 DEGs, 9 upregulated and 17 downregulated. Within the motility-associated genes, flaA was downregulated while flgH exhibited upregulation. Similar to the bile environment, liver-infected C. hepaticus also showed upregulation of the gene involved in the CmeABC multidrug efflux system, cmeA, alongside a glycosyltransferase protein 2 gene (I5Q61_RS01360). Evidence of metabolic adaptation is detected by the upregulation of yedF (sulfur metabolism) and napB (a component of the nitrate reductase complex), which facilitates anaerobic respiration. In the purine biosynthesis pathway, purN was upregulated. In contrast, the significant outer membrane porin mompA and stress response chaperones dnaK and groL were downregulated, along with the electron transport gene nifJ. Genes related to intracellular adaptation, such as yggS, which plays a role in PLP homeostasis, were found to be upregulated. Furthermore, a DUF2920 family protein (I5Q61_RS04730) was downregulated. Other than these genes, highly upregulated genes were classified as hypothetical proteins. Collectively, these results indicate that C. hepaticus adopts a metabolically poised and low-activity condition within liver tissue, thereby facilitating immune evasion and persistence, which may contribute to the pathogenesis of SLD.

Figure 3.

Heatmap of Differentially Expressed Genes in Campylobacter hepaticus: LMH-Infected and Liver-Infected Samples vs. Controls. (A) Genes involved in motility, chemotaxis, adhesion, outer membrane protein assembly, Type II secretion system, and protein folding/stress response in LMH-infected cells. (B) Genes associated with DNA repair, cell division, core metabolic enzymes, iron transport, purine biosynthesis, and ribosomal proteins in LMH-infected cells. (C) Genes differentially expressed in liver-isolated C. hepaticus, including those related to motility, stress response chaperones, multidrug efflux systems, outer membrane proteins, sulfur and nitrate metabolism, purine biosynthesis, and electron transport.

Figure 3.

Heatmap of Differentially Expressed Genes in Campylobacter hepaticus: LMH-Infected and Liver-Infected Samples vs. Controls. (A) Genes involved in motility, chemotaxis, adhesion, outer membrane protein assembly, Type II secretion system, and protein folding/stress response in LMH-infected cells. (B) Genes associated with DNA repair, cell division, core metabolic enzymes, iron transport, purine biosynthesis, and ribosomal proteins in LMH-infected cells. (C) Genes differentially expressed in liver-isolated C. hepaticus, including those related to motility, stress response chaperones, multidrug efflux systems, outer membrane proteins, sulfur and nitrate metabolism, purine biosynthesis, and electron transport.

4. Discussion

Our transcriptomic analysis of C. hepaticus, under three distinct growth conditions, such as in vitro exposure to chicken bile, infection of LMH cells, and isolation from naturally infected chicken livers, reveals that C. hepaticus extensively reprograms its gene expression, enabling it to survive under diverse environmental conditions and stresses. Although every condition prompted unique responses, several general trends were also observed.

4.1. Adaptation to Bile Exposure

Bile, rich in deoxycholate, is a hostile and detergent-rich environment that can damage membranes and create oxidative stress [

20]. In response to this harsh environment, C. hepaticus undergoes extensive transcriptomic reprogramming to fortify its cell envelope, modulate motility, alter metabolism, and activate defences [

12]. We observed significant upregulation of genes involved in surface structure modification and cell envelope biogenesis in bile. For example, glycosylation-related genes (pglC, pseB, pseC, and a motility-associated glycosyltransferase) were induced, suggesting active remodelling of surface architecture. Consistently, C. hepaticus upregulated peptidoglycan biosynthesis genes (murF) and periplasmic peptidoglycan assembly factors (lpoB), along with an LPS core biosynthesis gene (kdsB), indicating it reinforces its cell wall and outer membrane under bile exposure. An outer membrane protein of the OmpA family (ompA) also showed high expression, potentially adjusting membrane permeability or antigenicity. CmeABC is a well-known Resistance-Nodulation-Division (RND) family efflux system in Campylobacter that is essential for bile resistance and intestinal colonization [

21]. The induction of cmeA and cmeC by bile salts provides a rapid defensive mechanism to expel toxic bile components. These changes indicate that the bacterium reinforces and remodels its surface membrane to combat the toxic effects of the bile. This observation strongly agrees with findings in C. jejuni, where LPS structure activity alteration enhances bile resistance [

22]. Similarly, the papP/Q transporter (involved in glutamine uptake) has been implicated in stress tolerance and virulence of C. jejuni, with high upregulation of papP/Q genes, suggesting that C. hepaticus similarly activates nutrient-scavenging and stress-protective transport systems to survive bile stress [

12,

22].

Bile exposure triggered a complex change in C. hepaticus motility gene expression. Interestingly, several genes encoding the flagellar motor and assembly apparatus (fliG, fliH, fliY, flgH, flgI, and flgE) were upregulated, whereas the major structural components of the flagellum (such as the flagellin flaA, flaG, fliD, flgC, and fliS) were downregulated. The chemotaxis signaling gene cheV was also strongly repressed. This pattern suggests C. hepaticus might be fine-tuning its motility by maintaining or strengthening the flagellar motor function while limiting production of the exposed filament. By reducing FlaA and related structural proteins, the bacterium could restrict flagellar assembly to conserve energy or avoid immune recognition, even as it preserves the machinery needed for motility. Flagellin is a major antigen, and many pathogens downregulate flagellar expression in host environments to evade detection [

12]. Indeed, a previous in vivo study on C. hepaticus found that numerous flagella and chemotaxis genes were downregulated when the bacteria were recovered from bile in infected chickens [

12]. Our in vitro findings mirror this defensive strategy. In contrast, C. jejuni has been shown to transiently increase flaA expression upon bile. exposure [

22], presumably to enhance motility for initial colonization of the gut. The divergence for C. hepaticus may reflect a different survival strategy, such as during early bile exposure, which might limit flagellar filament production to minimize host immune stimulation, as our data indicated, aligning with the long-term suppression of flagella observed in vivo [

12]. We speculate that C. hepaticus briefly relies on its existing motility organelle to navigate bile, but quickly down-modulates flagellin and chemotaxis receptors (e.g., CheV) once within the biliary environment, adopting a more sessile or stealthy state. This nuanced motility response could help the bacterium balance the need to spread versus the need to persist undetected in the gallbladder or bile ducts.

Bile exposure triggered significant changes in C. hepaticus energy metabolism, marked by upregulation of genes involved in anaerobic and alternative respiration. Notably, the periplasmic nitrate reductase operon genes (napA, napG, and napH) were strongly upregulated, suggesting the use of nitrate as a terminal electron acceptor under oxygen-limited conditions in the bile [

12]. Key components of the cbb3-type cytochrome c oxidase (ccoN and ccoO) and NADH dehydrogenase subunits (nuoD, nuoH, nuoI, nuoK, and nuoL) were also upregulated, indicating a reorganization of the electron transport chain to maintain energy production. Additionally, in our study, C. hepaticus elevated hydrogen metabolism genes (hydC, hypB, hypC, and hypE), which is consistent with the use of molecular hydrogen for respiration, as observed in Campylobacter [

12] and Helicobacter spp [

23]. The induction of dxs (moaA and modA further supports metabolic adaptation to sustain membrane function and redox balance [

24,

25]. Collectively, these responses suggest that C. hepaticus shifts toward anaerobic respiration and energy conservation to survive in the bile-rich, microaerobic environment.

Conversely, downregulation of genes involved in growth and housekeeping functions, such as multiple ribosomal proteins (rplA, rplS, rpsB, and rpsM), DNA replication and cell division (ftsY, pal, recA, and xseA), nucleotides biosynthesis (pyrH, gmk), amino acids biosynthesis (leuA, leuB, and aroQ), along with several classical oxidative stress response genes (groES, trxA, tpx, sodB, and perR), suggests that C. hepaticus adopts a semi-dormant, energy-conserving state by minimizing metabolic output and potentially reducing expression of immunogenic proteins. This semi-dormant state is specifically referred to as a viable but nonculturable (VBNC) state [

26]. These similar transcriptional profiles observed in C. hepaticus recovered from chicken bile indicate a quiescent adaptation strategy [

12]. The suppressed stress response and heat-shock genes may reflect either a stabilized post-stress state or an unconventional survival mechanism. Rather than arresting growth entirely, C. hepaticus appears to selectively divert resources toward envelope fortification, transporter activation, and metabolic remodeling. Notably, many strongly regulated genes remain hypothetical, hinting at novel, uncharacterized factors involved in adaptation. Overall, this transcriptomic profile reflects a bacterium in survival mode, modulating its physiology for persistence in the bile-rich hepatic niche and contributing to its role in SLD.

4.2. Adaptation Within LMH Cells

Within LMH cells, C. hepaticus exhibited broad-scale gene downregulation, reflecting a transition to a low-activity state that is probably intended to avoid host defenses and adapt to the hepatocellular microenvironment intracellular niche. This is corroborated by previous in vitro infection experiments, which showed that C. hepaticus was strongly invasive in LMH cells and had much higher internalization compared to C. jejuni, C. lari, and C. upsaliensis, with a high bacterial population localized intracellularly by 5 hours post-infection [

8]. Thus, in our 12-hour post-infection model, we reasonably assume that most C. hepaticus cells had been internalized and were actively adapting to the intracellular hepatocellular environment.

Remarkably, motility and chemotaxis genes, such as central flagellar constituents (flaA, flgK/L, and fliD) and regulators (flgM and flgN), were strongly downregulated. As mentioned above under ‘Adaptation to Bile Exposure’, flagellin is a potent immune stimulus through TLR5; repression of flagellar expression may help the bacterium evade host immune detection [

27,

28]. This mirrors the mechanisms observed for C. jejuni, which downregulates flagella upon long-term colonization of the host to minimize immune activation [

12,

29,

30]. Likewise, chemotaxis genes (cheY, cheV, and methyl-accepting receptors or transducer-like protein, I5Q61_04175) were also repressed, indicating a decreased requirement for movement within the static intracellular habitat and transition toward a sessile, adapted state. In contrast to the broad downregulation of motility and chemotaxis genes, C. hepaticus upregulated some secretion and membrane-related genes, implying specific adaptations for intracellular survival. For example, gspE, a component of the type II secretion system, was induced, which may facilitate the secretion of effectors involved in modulating host functions or obtaining nutrients [

31]. Additionally, bamA, which participates in outer membrane protein assembly, was upregulated, whereas mompA (major outer membrane protein) was downregulated, suggesting membrane remodeling, perhaps to decrease permeability or conceal surface antigens. Furthermore, cadF, an important adhesin necessary for initial host cell binding and invasion, was downregulated in intracellular C. hepaticus, likely to reflect both a reduced need for adhesion post-invasion and a strategy to further evade immune recognition.

Downregulation of growth-related genes and protein synthesis implies that C. hepaticus enters a reduced or dormant phenotype within host cells [

32]. Decreased expression of ribosomal proteins (rpsR, rpsF, rpsU,rpsB, and rpmB), replication/repair genes (dnaE and recA), and the cell division genes ftsZ, ftsY, and pal are indicative of a general inhibition of growth and cell division machinery. This profile is consistent with the hypothesis that C. hepaticus is not actively growing in LMH cells but remains in a low-activity, intracellular state [

5]. Interestingly, despite entering a slower growth phase, C. hepaticus downregulated many chaperone and stress response genes in LMH cells, including grpE, dnaK, groES, groEL, and tig. This suggests the intracellular environment may be less stressful than external conditions like growth in bile or bacteriologic media under microaerophilic conditions. Suppression of highly immunogenic proteins, such as GroEL and DnaK, may further help the bacterium evade immune detection. Overall, C. hepaticus appears to adapt to the intracellular niche without triggering a classical stress response.

Metabolic changes observed in LMH-infected C. hepaticus suggest a shift toward energy conservation and nutrient scavenging. Selective upregulation (purH, and purB) and downregulation (purD) of genes involved in purine metabolism point to partial reliance on host-derived nucleotides, allowing the bacterium to bypass the energy-intensive early steps of de novo purine synthesis. Concurrently, downregulation of central carbon metabolism genes (sucC, and pckA) indicates reduced glycolytic and TCA activity, possibly due to dependence on amino acids or fatty acids available within the nutrient-rich LMH intracellular environment. Similarly, the downregulation of antioxidant enzymes like sodB, tpx, and trxA/B suggests that the intracellular environment of hepatocytes does not subject the bacterium to high levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS), in contrast to phagocytic immune cells that actively generate oxidative bursts [

33]. This apparent lack of oxidative stress in LMH cells might enable C. hepaticus to conserve energy by downregulating ROS-detoxifying enzymes. Additionally, the upregulation of ceuB in LMH showed that C. hepaticus can sense and respond to iron limitation within host cells. CeuB, a component of the siderophore-mediated iron uptake system in Campylobacter, imports ferric iron. Given that the free iron is tightly sequestered by host nutritional immunity mechanisms, the upregulation of ceuB likely reflects a bacterial strategy to maintain iron homeostasis and support essential metabolic processes under iron-restricted intracellular conditions by increasing iron uptake [

34,

35].

4.3. In Vivo Adaptation in the Liver

The C. hepaticus gene expression profile in infected liver tissue shares many similarities with that observed in the bile and LMH cell infection model. The liver, the primary site of SLD lesions, is a nutrient-rich environment but also exposes the bacterium to the immune defense of the host and antimicrobials like bile salts and complement proteins derived via the bloodstream and bile ducts [

36]. As in the bile and LMH intracellular niche, C. hepaticus in the liver downregulated prominent motility gene flaA, which supports the hypothesis that diminished motility aids the bacterium in evading immune detection in its target organ. This finding aligns with the observations in C. jejuni, where long-term colonization of the host is often associated with downregulation of flagellar and chemotaxis genes, likely to avoid detection by host immune cells [

12,

29,

37]. Notably, despite overall suppression of flagellar genes, flgH, which encodes the L-ring of the flagellar basal body, was upregulated. Given its role in anchoring the flagellum to the outer membrane, solitary upregulation of flgH might reflect a need to stabilize the flagellar base or strengthen the outer membrane during stress conditions [

38]. Alternatively, flgH expression could be a result of operon-level transcriptional control or an indication of host-driven signaling subtleties [

39].

The key adaptation of C. hepaticus in the liver is its change in respiratory metabolism. Upregulation of napB suggests reliance on nitrate as an alternative electron acceptor. This shift may confer an energetic advantage or reflect greater availability of nitrate/nitrite due to hepatic inflammation. It mirrors findings in C. jejuni readily switches to nitrate/nitrite respiration under in vivo bile conditions, and upregulation of nap genes has been documented during bile exposure [

12]. This is consistent with the upregulation of the nitrate reductase gene (napA) in our in vitro bile experiment. By prioritizing nitrate respiration, C. hepaticus can produce energy in low-oxygen environments and may also reduce harmful reactive nitrogen species from the host through baseline nrf gene activity, which provides two key advantages for survival in host tissues. Beyond respiration, several other metabolic genes of C. hepaticus were also differentially expressed in the liver. For example, yedF, a gene potentially engaged in sulfur metabolism, was upregulated. The liver and gallbladder are rich in sulfur-containing compounds (e.g., taurine-conjugated bile acids) [

40], so elevated yedF expression may enhance the bacterium’s ability to utilize or detoxify sulfur compounds available in this environment. Additionally, yggS, which is involved in the preservation of pyridoxal phosphate (PLP), was also induced. As PLP is vital for amino acid metabolism and oxidative stress protection, elevated yggS likely supports PLP-dependent enzyme activities during infection, indicating another level of fine-tuning of bacterial metabolism in the host [

41]. Changes in nucleotide biosynthesis further suggest metabolic reprogramming of C. hepaticus in the liver. Upregulation of purN suggests a possible shift toward purine salvage or later-stage synthesis, likely enabled by the availability of host-derived precursors like glycine or formate. This may also reflect feedback inhibition from abundant purines released by lysed host cells.

An important virulence gene,

cmeA, codes for the periplasmic adaptor protein of the

CmeABC multidrug efflux pump, which plays a key role in bile salt resistance in

Campylobacter [

42]. Similar to our bile experiment,

cmeA overexpression in the liver suggests that

C. hepaticus activates the

CmeABC efflux pump to detoxify bile salts and other toxic compounds present in the hepatic environment. This mechanism, also used by

C. jejuni, contributed to antimicrobial resistance and allows bacterial survival within host tissues [

22,

43]. The major porin gene

mompA was downregulated in liver-derived

C. hepaticus, likely reducing outer membrane permeability to limit bile salts and host complement molecules entering through porin channels. While this may restrict nutrient intake, it enhances defense in the hostile liver environment. This pattern of porin downregulation paired with efflux pump activation mirrors a well-known stress response in

C. jejuni and other Gram-negative bacteria under bile exposure [

42,

44]. The similarity of transcriptomic changes observed in the

C. hepaticus LMH infection model (upregulation of

gspE and

bamA, and downregulation of

mompA) further supports that outer membrane remodeling is a consistent survival strategy inside host cells and tissues. Along with porin changes, the aa glycosyltransferase gene (I5Q61_RS01360) was strongly upregulated in liver-isolated

C. hepaticus, indicating potential modifications to surface structures like capsule or lipooligosaccharides (LOS). In

Campylobacter, surface glycosylation of LOS, capsule, and flagellin is a known strategy for immune evasion and host mimicry [

45]. Both in vitro LMH and in vivo liver isolates,

C. hepaticus downregulated classic heat-shock or general stress response chaperone genes

groL and

dnaK (Hsp70). These molecular chaperones typically help refold misfolded proteins under stress but are also highly immunogenic and can trigger strong host immune responses when exposed to the cell surface or released during infection [

46]. Repression of these genes in the liver suggests one of two possibilities: either the bacterium experiences a relatively stable intracellular/bile environment that doesn’t elicit a stress response, or it intentionally suppresses these immunostimulatory proteins to reduce immune detection. This strategy contrasts sharply with many acute infections where bacteria upregulate stress proteins and inadvertently provoke robust immunity [

46,

47]. Collectively, these transcriptomic results indicate that

C. hepaticus adopts a metabolically poised, dormant state within liver tissue. Through downregulation of strong immunogenic proteins,

C. hepaticus can evade immediate immune clearance to form chronic infection foci. However, constant metabolic activities, such as ammonia production via nitrite reduction, can provoke local inflammation and hepatocellular injury. Such a balance between immune evasion and sustained, low-level stimulation is likely a key factor in the formation of the typical necrotic lesions observed in SLD.

5. Conclusions

This study highlights dynamic translational adaptations of C. hepaticus across distinct host-relevant environments, such as chicken bile, hepatocyte (LMH) cells, and infected liver tissue, demonstrating dynamic niche-specific gene expression adaptations. In bile, C. hepaticus exists in a metabolically active, semi-dormant state, with remodeling of the cell envelope, activation of efflux, and induction of alternative respiratory pathways to resist detergent stress and oxygen restriction. In hepatocytes and infected liver, in contrast, the bacterium assumes a low-active, dormant, immune-evasive phenotype, where all motility, protein synthesis, and immunogenic stress proteins are repressed, but key metabolic processes, such as nitrate respiration, sulfur utilization, and pyridoxal phosphate homeostasis, are preserved. These results underscore the two-phase infection strategy of C. hepaticus: active colonization and resistance during initial biliary transit, followed by intracellular persistence in host tissues by metabolic reprogramming and immune evasion. Targeting these phase-specific processes may present effective strategies for SLD control. Vaccines against outer membrane iron transporters or flagellum components may impair bacterial colonization and fitness, whereas inhibitors of hydrogenase or nitrite reductase might selectively weaken C. hepaticus without disrupting the commensal gut microbiota. Additional functional studies involving gene knockouts or knockdowns will be necessary to validate these targets and further elucidate the molecular basis of C. hepaticus virulence. Overall, this transcriptomic analysis of C. hepaticus in various niches enhances our knowledge of C. hepaticus pathogenesis and identifies potential bacterial targets that may be exploited to protect chickens against SLD.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: Preprints.org, File S1: Overall differential gene expression profile data of C. hepaticus in bile, LMH cells, and infected liver; Figure S1: Heat map of all differentially expressed genes of C. hepaticus in bile; Figure S2: Heat map of all differentially expressed genes of C. hepaticus in LMH cells; Figure S3: Heat map of all differentially expressed genes of C. hepaticus in the infected liver.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.K.; methodology, V.B., L.K.E. and C.G; software, V.B. and L.K.E.; validation, V.B. and L.K.E.; formal analysis, V.B. and L.K.E.; investigation, V.B., L.K.E., C.G. and G.B.; resources, G.B. and S.K.; data curation, V.B. and L.K.E.; writing—original draft preparation, V.B. and L.K.E.; writing—review and editing, V.B., L.K.E. and S.K.; visualization, V.B.; supervision, S.K.; project administration, S.K.; funding acquisition, S.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Agriculture and Food Research Initiative Competitive Grant no. 1031150 from the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) National Institute of Food and Agriculture (NIFA) and the USDA NIFA Animal Health and Disease Grant no. 1023600.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable. Field samples were collected during a formal disease outbreak investigation by an avian extension veterinarian.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database in NCBI under the accession number ……..(waiting for accession).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| SLD |

Spotty liver disease |

| LMH |

Chicken liver hepatocellular carcinoma epithelial cells |

| FBS |

Fetal bovine serum |

| FDR |

false discovery rate |

| DEG |

Differentially expressed gene |

| RIN |

RNA integrity number |

| FC |

Fold change |

| LOS |

Lipooligosaccharide |

| VBNC |

Viable but non-culturable |

References

- Courtice, J.M.; Mahdi, L.K.; Groves, P.J.; Kotiw, M. Spotty Liver Disease: A Review of an Ongoing Challenge in Commercial Free-Range Egg Production. Vet Microbiol 2018, 227, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade, B.; Rautenschlein, S.; Hao Van, T.T.; Moore, R.J. Campylobacter Hepaticus and Spotty Liver Disease in Poultry. Avian Dis 2025, 68, 481–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ienes-Lima, J.; Becerra, R.; Logue, C.M. Comparative Genomic Analysis of Campylobacter Hepaticus Genomes Associated with Spotty Liver Disease, Georgia, United States. Front Microbiol 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groves, P.J.; Gao, Y.K.; Kotiw, M.; Wong, P.H.L.; Muir, W.I. Epidemiological Risk Factors and Path Models for Spotty Liver Disease in Australian Cage-Free Flocks Incorporating a Scratch Area. Poult Sci 2025, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtice, J.M.; Ahmad, T.B.; Wei, C.; Mahdi, L.K.; Palmieri, C.; Juma, S.; Groves, P.J.; Hancock, K.; Korolik, V.; Petrovsky, N.; et al. Detection, Characterization, and Persistence of Campylobacter Hepaticus, the Cause of Spotty Liver Disease in Layer Hens. Poult Sci 2023, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawshaw, T.R.; Chanter, J.I.; Young, S.C.L.; Cawthraw, S.; Whatmore, A.M.; Koylass, M.S.; Vidal, A.B.; Salguero, F.J.; Irvine, R.M. Isolation of a Novel Thermophilic Campylobacter from Cases of Spotty Liver Disease in Laying Hens and Experimental Reproduction of Infection and Microscopic Pathology. Vet Microbiol 2015, 179, 315–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van, T.T.H.; Elshagmani, E.; Gor, M.C.; Scott, P.C.; Moore, R.J. Campylobacter Hepaticus Sp. Nov., Isolated from Chickens with Spotty Liver Disease. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2016, 66, 4518–4524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van, T.T.H.; Elshagmani, E.; Gor, M.C.; Anwar, A.; Scott, P.C.; Moore, R.J. Induction of Spotty Liver Disease in Layer Hens by Infection with Campylobacter Hepaticus. Vet Microbiol 2017, 199, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrovska, L.; Tang, Y.; van Rensburg, M.J.J.; Cawthraw, S.; Nunez, J.; Sheppard, S.K.; Ellis, R.J.; Whatmore, A.M.; Crawshaw, T.R.; Irvine, R.M. Genome Reduction for Niche Association in Campylobacter Hepaticus, a Cause of Spotty Liver Disease in Poultry. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, M.; Klein, B.; Sahin, O.; Girgis, G. Isolation and Characterization of Campylobacter Hepaticus from Layer Chickens with Spotty Liver Disease in the United States. Avian Dis 2018, 62, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phung, C.; Wilson, T.B.; Quinteros, J.A.; Scott, P.C.; Moore, R.J.; Van, T.T.H. Enhancement of Campylobacter Hepaticus Culturing to Facilitate Downstream Applications. Sci Rep 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao Van, T.T.; Lacey, J.A.; Vezina, B.; Phung, C.; Anwar, A.; Scott, P.C.; Moore, R.J. Survival Mechanisms of Campylobacter Hepaticus Identified by Genomic Analysis and Comparative Transcriptomic Analysis of in Vivo and in Vitro Derived Bacteria. Front Microbiol 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiarpinitnun, P.; Iwakiri, A.; Fuke, N.; Pongsawat, P.; Miyanishi, C.; Sasaki, S.; Taniguchi, T.; Matsui, Y.; Luangtongkum, T.; Yamada, K.; et al. Involvement of Campylobacter Species in Spotty Liver Disease-like Lesions in Broiler Chickens Detected at Meat Inspections in Miyazaki Prefecture, Japan. Microorganisms 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.K.; Singh, M.; Muir, W.I.; Kotiw, M.; Groves, P.J. Identification of Epidemiological Risk Factors for Spotty Liver Disease in Cage-Free Layer Flocks in Houses with Fully Slatted Flooring in Australia. Poult Sci 2023, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottapu, C.; Sahin, O.; Edison, L.K.; Srednik, M.E.; Kariyawasam, S. Complete Genome Sequences of Campylobacter Hepaticus Strains USA1 and USA5 Isolated from a Commercial Layer Flock in the United States. Microbiol Resour Announc 2025, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arukha, A.; Denagamage, T.N.; Butcher, G.; Kariyawasam, S. Complete Genome Sequence of Campylobacter Hepaticus Strain UF2019SK1, Isolated from a Commercial Layer Flock in the United States. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van, T.T.H.; Elshagmani, E.; Gor, M.C.; Anwar, A.; Scott, P.C.; Moore, R.J. Induction of Spotty Liver Disease in Layer Hens by Infection with Campylobacter Hepaticus. Vet Microbiol 2017, 199, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edison, L.K.; Kudva, I.T.; Kariyawasam, S. Comparative Transcriptome Analysis of Shiga Toxin-Producing Escherichia Coli O157:H7 on Bovine Rectoanal Junction Cells and Human Colonic Epithelial Cells during Initial Adherence. Microorganisms 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edison, L.K.; Kariyawasam, S. From the Gut to the Brain: Transcriptomic Insights into Neonatal Meningitis Escherichia Coli Across Diverse Host Niches. Pathogens 2025, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begley, M.; Gahan, C.G.M.; Hill, C. The Interaction between Bacteria and Bile. FEMS Microbiol Rev 2005, 29, 625–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cremers, C.M.; Knoefler, D.; Vitvitsky, V.; Banerjee, R.; Jakob, U. Bile Salts Act as Effective Protein-Unfolding Agents and Instigators of Disulfide Stress in Vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negretti, N.M.; Gourley, C.R.; Clair, G.; Adkins, J.N.; Konkel, M.E. The Food-Borne Pathogen Campylobacter Jejuni Responds to the Bile Salt Deoxycholate with Countermeasures to Reactive Oxygen Species. Sci Rep 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benoit, S.L.; Maier, R.J.; Sawers, R.G.; Greening, C. Molecular Hydrogen Metabolism: A Widespread Trait of Pathogenic Bacteria and Protists. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Chen, J.; Jiang, Q.; Huang, N.; Ding, X.; Peng, L.; Deng, X. The Molybdate-Binding Protein ModA Is Required for Proteus Mirabilis-Induced UTI. Front Microbiol 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, E.C.; Freel Meyers, C.L. DXP Synthase Function in a Bacterial Metabolic Adaptation and Implications for Antibacterial Strategies. Antibiotics 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakur, S.G.J.; Williamson, S.L.; Pavic, A.; Gao, Y.K.; Harris, T.; Kotiw, M.; Muir, W.I.; Groves, P.J. Developing a Selective Culturing Approach for Campylobacter Hepaticus. PLoS One 2024, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajam, I.A.; Dar, P.A.; Shahnawaz, I.; Jaume, J.C.; Lee, J.H. Bacterial Flagellin-a Potent Immunomodulatory Agent. Exp Mol Med 2017, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmi, A.; Nasher, F.; Dorrell, N.; Wren, B.; Gundogdu, O. Revisiting Campylobacter Jejuni Virulence and Fitness Factors: Role in Sensing, Adapting, and Competing. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friman, V.P.; Lindstedt, C.; Hiltunen, T.; Laakso, J.; Mappes, J. Predation on Multiple Trophic Levels Shapes the Evolution of Pathogen Virulence. PLoS One 2009, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, C.A.; Bogacz, M.; El Abbar, F.M.; Browning, D.D.; Hsueh, B.Y.; Waters, C.M.; Lee, V.T.; Thompson, S.A. The Campylobacter Jejuni Response Regulator and Cyclic-Di-GMP Binding CbrR Is a Novel Regulator of Flagellar Motility. Microorganisms 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korotkov, K. V.; Sandkvist, M.; Hol, W.G.J. The Type II Secretion System: Biogenesis, Molecular Architecture and Mechanism. Nat Rev Microbiol 2012, 10, 336–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Gao, B.; Novik, V.; Galán, J.E. Quantitative Proteomics of Intracellular Campylobacter Jejuni Reveals Metabolic Reprogramming. PLoS Pathog 2012, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allameh, A.; Niayesh-Mehr, R.; Aliarab, A.; Sebastiani, G.; Pantopoulos, K. Oxidative Stress in Liver Pathophysiology and Disease. Antioxidants 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randaisi, V.R.; Bunch, M.L.; Beavers, W.N.; Rogers, T.; Mesler, R.; Ashurst, T.D.; Donohoe, D.R.; Monteith, A.J.; Johnson, J.G. Efficient Gastrointestinal Colonization by Campylobacter Jejuni Requires Components of the ChuABCD Heme Transport System 2025.

- Miller, C.E.; Williams, P.H.; Ketley, J.M. Pumping Iron: Mechanisms for Iron Uptake by Campylobacter. Microbiology (N Y) 2009, 155, 3157–3165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urdaneta, V.; Casadesús, J. Interactions between Bacteria and Bile Salts in the Gastrointestinal and Hepatobiliary Tracts. Front Med (Lausanne) 2017, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloomfield, S.J.; Midwinter, A.C.; Biggs, P.J.; French, N.P.; Marshall, J.C.; Hayman, D.T.S.; Carter, P.E.; Mather, A.E.; Fayaz, A.; Thornley, C.; et al. Genomic Adaptations of Campylobacter Jejuni to Long-Term Human Colonization. Gut Pathog 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, T.; Makino, F.; Miyata, T.; Minamino, T.; Kato, T.; Namba, K. Structure of the Molecular Bushing of the Bacterial Flagellar Motor. Nat Commun 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soutourina, O.A.; Bertin, P.N. Regulation Cascade of Flagellar Expression in Gram-Negative Bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Rev 2003, 27, 505–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, A.; Schmitt-Kopplin, P. The Role of Fecal Sulfur Metabolome in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. International Journal of Medical Microbiology 2021, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Chen, Y.; Wang, L.; Bai, X.; Bu, T.; Zhang, J.; Lu, M.; Ha, N.C.; Quan, C.; Nam, K.H.; et al. Structural and Functional Analysis of the Pyridoxal Phosphate Homeostasis Protein YggS from Fusobacterium Nucleatum. Molecules 2022, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Cagliero, C.; Guo, B.; Barton, Y.W.; Maurel, M.C.; Payot, S.; Zhang, Q. Bile Salts Modulate Expression of the CmeABC Multidrug Efflux Pump in Campylobacter Jejuni. J Bacteriol 2005, 187, 7417–7424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dzieciol, M.; Wagner, M.; Hein, I. CmeR-Dependent Gene Cj0561c Is Induced More Effectively by Bile Salts than the CmeABC Efflux Pump in Both Human and Poultry Campylobacter Jejuni Strains. Res Microbiol 2011, 162, 991–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, E.M.; Raftery, M.; Goodchild, A.; Mendz, G.L. Campylobacter Jejuni Response to Ox-Bile Stress. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 2007, 49, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Day, C.J.; Semchenko, E.A.; Korolik, V. Glycoconjugates Play a Key Role in Campylobacter Jejuni Infection: Interactions between Host and Pathogen. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2012, 2, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henderson, B.; Allan, E.; Coates, A.R.M. Stress Wars: The Direct Role of Host and Bacterial Molecular Chaperones in Bacterial Infection. Infect Immun 2006, 74, 3693–3706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figaj, D. The Role of Heat Shock Protein (Hsp) Chaperones in Environmental Stress Adaptation and Virulence of Plant Pathogenic Bacteria. Int J Mol Sci 2025, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).