Introduction

Entomophobia is an irrational and persistent fear of insects even when it is known by the patients that most insects are not harmful [

1]. Entomophobia is defined not as a separate disease entity in the 5th edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders (DSM-5), but subsumed under the topic of specific phobias (SP). The revised DSM-5 defines crucial criteria for the diagnosis of a specific phobia including having fear or anxiety about a certain object or situation, an immediate anxiety response, avoidance behavior or enduring extreme fear and anxiety, inadequately severe fear or anxiety, typically lasting for 6 months or more, resulting in significant distress or impairment, which is not explained by another disorder [

2]. According to the DSM-5, Five subtypes of SP are available (animal, natural environment, blood-injection-injury, situational, and others); these subtypes are usually explored in studies by collapsing categories, but evidence suggests these phobias may have different associated key factors, such as animal fears, which are more frequent in females, and threat control, which is more frequent in the environmental subtype of specific phobia [

3,

4]. The animal subtype (e.g., bee, spider) is close to the entomophobia concept, and resembles the most frequent phobia subtype beneath acrophobia. The lifetime prevalence of SPs ranges from 3% to 15% worldwide, and in 10-30% of cases, this type of phobia persists [

5]. A systematic review suggests that exposure therapy (ET) and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) are well-suited psychotherapies for a range of SPs, and ET can be augmented by other technology-based (e.g virtual reality) and pharmacologic interventions [

6]. Effects of ET, and CBT have been also described in a respective meta-analysis [

7]. Besides the effectiveness of ET as the gold standard treatment for SPs, about one-third of the patients experience relapse of fear, vegetative reactions, and avoidance, thus there is a need for alternative well-tolerated and efficient treatments in SP [

6,

8,

9]. Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) is a non-invasive brain stimulation method that alters excitability and plasticity of cortical areas by delivering electrical currents at subthreshold levels with regard to the generation of action potentials; at the macroscale level cathodal and anodal stimulation over cerebral target regions have excitability-enhancing and -reducing effects respectively with standard stimulation protocols [

10]. Studies have suggested that tDCS effectively reduces symptoms of a variety of psychiatric disorders, including depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and schizophrenia [

11,

12,

13]. A review including 32000 interventions in 1000 healthy humans and patients did not report serious adverse effects of tDCS protocols. Therefore, standard protocols can be accounted as safe [

14]. Recently, intensified tDCS protocols have been described. These protocols were developed to induce long-term effects similar to l-LTP, by applying more than one stimulation session per day at specific time intervals [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19], have shown positive results in psychiatric disorders [

14] and to be safe and feasible in previous studies. In the project research, the focus is on determining the effectiveness of an enhanced number of tDCS sessions within the conceptual frame described above (30 sessions). Previous findings in other psychiatric disorders suggest that the therapeutic effect of 2mA stimulation with these intensified protocols may be superior to 1mA intensified tDCS [

18,

20].

Studies exploring the neurophysiological mechanisms of fear-related behaviors in humans and rodent models suggest that different parts of the prefrontal cortex (PFC) have a key role in the development and extinction of fear [

21]. Evidence from animal studies shows that the prelimbic (PL) and infralimbic (IL) cortices, the homologues of the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) in humans, are involved in top-down regulation of subcortical regions involved in fear processing crucial for an appropriate behavioral fear response [

22]. High-frequency stimulation of the mPFC induces top-down regulation in humans, leading to enhanced fear extinction. The proposed mechanism underlying this process involves activation of a specific type of GABA ergic neurons in the amygdala, the intercalated cells, by the mPFC. These neurons play a crucial role in the inhibition of the amygdala, which is a key region involved in the initiation of fear responses [

23]. Similar to animal models, recent studies in healthy humans show that increasing vmPFC activity via non-invasive brain stimulation, namely anodal tDCS, enhances fear extinction, which has implications for the treatment of anxiety disorders [

24]. Studies suggest that targeting the vmPFC via tDCS with the anode over that region (atDCS), and the cathode (ctDCS) over the DLPFC can have a positive effect on fear, fear memory, and the enhanced classification accuracy of threat, extinction, and extinction recall [

25,

26,

27,

28]. This is the first time that an intensified tDCS protocol with repeated stimulation with a short interval (20 min) is used for treating SP. In this case report, we stimulated the vmPFC [

24] in an entomophobia patient (extreme fear of cockroaches) with 30 intensified anodal tDCS sessions with 2.0 mA conducted twice daily with a twenty-minutes interval to reduce fear-related symptoms. We hypothesized that anodal tDCS over the vmPFC (AF3) significantly improves the severity of phobia symptoms and the anxiety level to phobic stmuli (cockroach) in a female patient with severe cockroach phobia.

Case Report

The patient was a 23-year-old woman who was massively afraid of cockroaches. She was not tolerating to see pictures of the animals, sometimes experienced the illusion of the sound of cockroaches and did not go to places where she was not sure that there were no cockroaches. This fear had led to disruptions in her daily life, she was not able to do things properly and had difficulty in doing things that required attention. She did not have any memories or experiences that caused this phobia and stated that she was always afraid of cockroaches since she can remember. In addition, there was no history of this fear in any of her family members. It should be noted that she had not taken any treatment until she came to us, and she did not receive any other intervention at the time of tDCS treatment. The diagnosis was made by a psychiatrist according to the respective DSM-5 criteria.

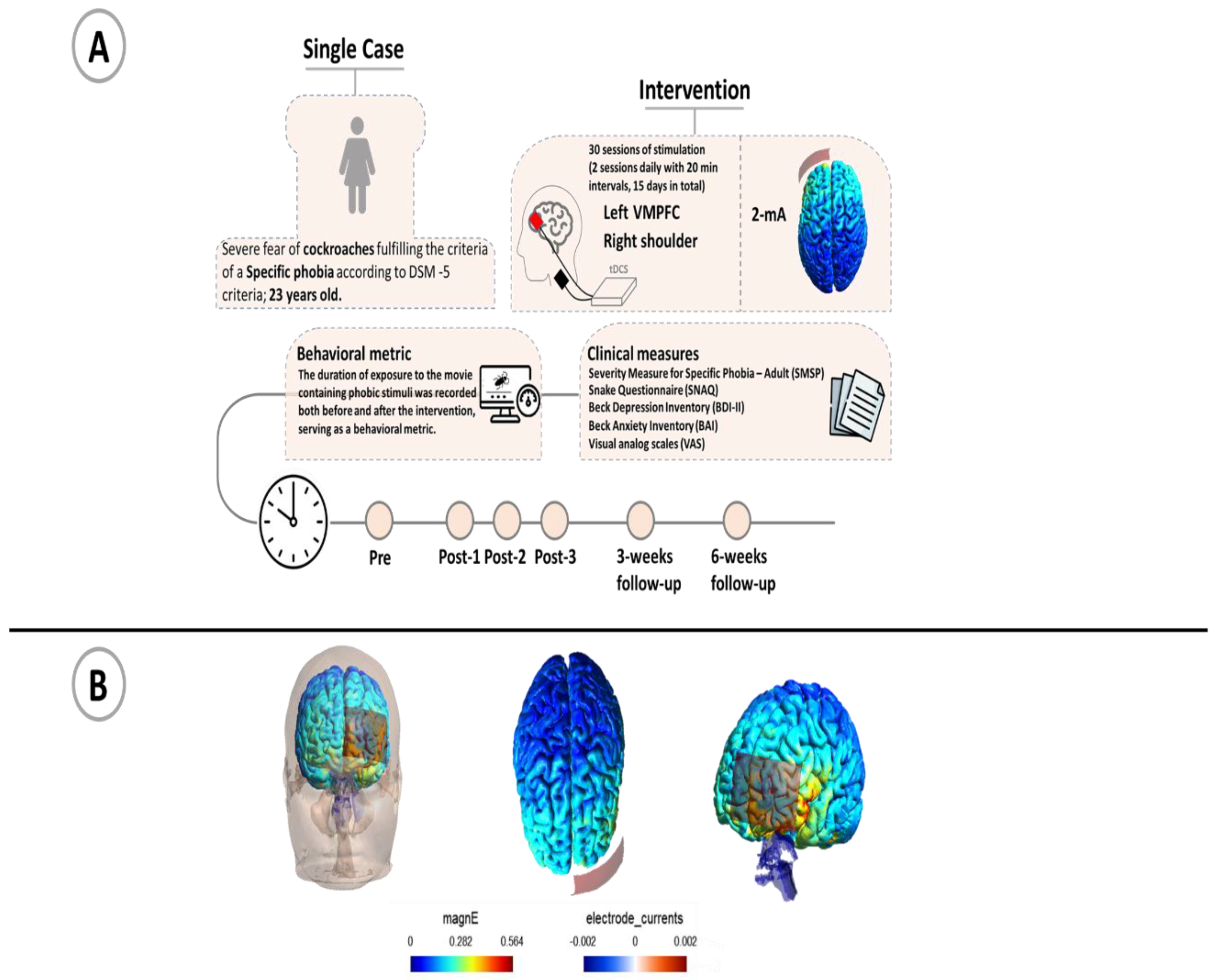

The psychological assessment of the patient was done in six stages: 1) one week before the intervention (baseline), 2) immediately after the end of 10 stimulation sessions, 3) immediately after the end of 20 stimulation sessions, 4) immediately after the end of 30 stimulation sessions and, 5) 3 weeks (follow-up1), 6) 6 weeks after the terminal intervention (follow-up2).

Before the intervention, the overall goal, and procedure was fully explained to the participant so that she was aware of the treatment process. She was evaluated for suitability for tDCS treatment based on standard inclusion/exclusion criteria such as no previous history of neurological diseases, brain surgery, epilepsy, seizures, brain injury, head injury or metal brain implants. Also, she signed a written informed consent before tDCS treatment. The treatment protocol involved 30 sessions with the anodal electrode placed over the left vmPFC (electrode position over the AF3 electrode position in accordance with the International 10 20 Electrode system), and the cathodal electrode placed over the contralateral shoulder [

29]. Each day, two tDCS sessions were administered with a 20-minute interval inbetween. The current intensity was set at 2 mA for 20 minutes per session, totaling 15 days of treatment. Direct current stimulation was delivered by a transcranial electrical stimulation device (V.L340. liv. Iran) through a pair of saline-soaked physiotherapy sponges and conductive rubber electrodes (5 x 7 cm) with a ramp up for 15 s and a ramp down of 15 s at the start and end of stimulation.

After each stimulation session, the participant completed a tDCS side effect questionnaire [

30]. Questionnaires for evaluating symptoms of phobia behavior and psychiatric symptoms were answered by the patient at six time points of the study, as outlined above. To explore phobia-related symptoms, the Severity Measure for Specific Phobia – Adult (SMSP) [

31]), and the Snake Anxiety Questionnaire (SNAQ) [

32] were used. In the latter scale, the word "snake" was replaced by "cockroach" [

33]. In order to evaluate other psychiatric symptoms, the patient completed the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II) [

34,

35] and Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) [

36,

37]. In order to measure behavioral metrics related to cockroach phobia, a 2-minute film with pictures of cockroaches was shown to the patient (baseline, after every 10 stimulation sessions and also 3 weeks and 6 weeks after the last stimulation session).

Negative affective states elicited by these short film clips, emotional distress and threat (estimating the possibility of emotional and physical harm) were assessed with visual analog scales (0-100) [

38]. The cockroach movie was presented to the patient until she reported being unable to continue watching. The duration of movie-watching was measured to assess the intensity of avoidance behavior in response to fearful stimuli

. The movie contained 10 different pictures of cockroaches from the internet. Each picture was displayed for about 7 seconds and then the picture was changed, after ten pictures these were repeated for a total duration of the movie of 2 minutes and after viewing the pictures, the level of emotional disturbance was measured.

The trial was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Zanjan University (Ethics code: IR.ZNU.REC.1402.029).

The steps and protocol of the study are shown in

Figure 1.

Results

The results of the psychological evaluations are reported in

Table 1. A significant improvement in both scales evaluating symptoms of phobia behavior emerged comparing outcomes before and after intervention. For the SNAQ scale, the percentage of reduction from pre-intervention to post-30 stimulation sessions was -25.00% and from pre-intervention to the follow-up after 3 and 6 weeks -50.00%. For the SMSP scale, the symptom reduction was -55.56% from pre-intervention to post-30 stimulation sessions and -44.44% from pre-intervention to 3 and 6 weeks follow-up. During presentation fear stimuli, the percentage of reduction of emotional distress and threat appraisals from pre- intervention to post-30 stimulation sessions was in order -10.00%, -20.00% and from pre-intervention to follow-up-3 and 6 weeks -25.00%, -30.00%.

The total length of the cockroach movie presentation was 2 minutes. Before the intervention, the patient did not tolerate to look at the movie at all (0). After 10 sessions, she tolerated to watch it for 10 seconds, after 20 sessions for 14 seconds, after 30 sessions for 18 seconds and at the 3- and 6-months follow up, she tolerated to watch the movie for 25 and 30 seconds.

For the questionnaires obtaining information about other psychiatric symptoms, specific changes after intervention as compared to baseline were seen. The percentage of reduction in the depression scale BDI-II from pre-intervention to post-30 stimulation sessions was -20.00%, from pre-intervention to the follow-up 3 weeks -20.00% and for the follow-up 6 weeks after intervention it was 0.00%. For the BAI scale, the score reduction from pre-intervention to post-30 stimulation sessions was -22.73% and from pre-intervention to follow-up 3 and 6 weeks -9.09%.

In order to measure side effects of stimulation, after each tDCS session, the patient answered a respective questionnaire. The respective results showed that the patient tolerated the stimulation well. Only minor side effects of mild intensity, including burning sensations and skin redness were reported by the participant on the anodal side (Left VMPFC) (

Table 2).

Discussion

In this case report study, we examined the effects of an intensified tDCS protocol (30 sessions, 2 mA stimulation for 20 minutes, twice a day with a 20-minute interval) over the left vmPFC with a cathodal return electrode over the right shoulder in a patient with a specific insect phobia. To our knowledge, this is the first study that applied this protocol for phobia symptoms. Our findings suggest intensified tDCS as an efficient treatment for Entomophobia. The patient showed significant improvement (up to 55 percent reduction) of phobic symptom severity in the third post-test immediately after the last intervention. This is not consistent with previous studies indicating that single session tDCS combined with ET did not affect phobia severity [

41]. The reason for this difference is most likely the intensitied stimulation in the present study, including twice daily stimulation over multiple days. In the present study, the intensity of phobic symptoms was moreover reduced during (-11%, -22% and -55%) and after intervention at the 3 and 6 weeks follow-ups (-44%) on the SMSP scale. Additionally, we observed that the tolerated watch time for movies containing phobic objects increased from

0 seconds to 18 seconds in the the final post-test , the 3 weeks follow- up and the 6 weeks follow- up This behavioral measure indicates a significant reduction of avoidance of fearful objects

. One likely reason for the larger efficacy of the applied intensified protocol as compared to previous studies might be that this protocol is suggested to induce late LTP-like plasticity, as shown for motor cortex excitability [

19]. Also, previous randomized clinical trials show that the 2 mA intensified (20 sessions, 2 mA stimulation for 20 minutes, twice a day with a 20-minute interval) tDCS protocol has a larger effect than the 1 mA intensfied protocol on social anxiety disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder symptoms, which indicates that higher tDCS intensity enhances efficacy [

20,

30]. We furthermore explored safety and tolerability of the transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) protocol used here. The patient did report mild burning sensations and skin redness after intervention. In addition to the side effects questionnaire, the participant was asked about other side effects, but no serious side effects were reported

, consistent with findings from Buchanan et al., which supports the safety of tDCS [

42]. It is however important to note that our study involved only a single patient, and larger sample sizes may reveal different results regarding treatment side effects.

The results of the BDI-II showed that depression decreased by 20% during intervention, and for the 3 week follow-up, but no improvement was observed for the 6 week follow-up compared to the baseline value. Also for anxiety, which was measured by the BAI questionnaire, a decrease of 22% during the three weeks of intervention was observed, but in the 6 week follow-up, this improvement was reduced to 9% as compared to the baseline.

These findings are promising for the treatment of specific phobia with tDCS, but because of missing sham and/or active control conditions, and only a single patient involved delivers only preliminary evidence. Further studies with a larger sample size and a rigorous randomized placebo-controlled design with long term follow-up are needed to substantiate these results. Ideally, a sham-controlled comparative analysis of tDCS alone versus combined protocols (e.g. tDCS + psychotherapy) should be conducted. In addition, one limitation of our study is the uncertainty regarding whether the improvement in film watching duration is attributable to the effect of tDCS or to habituation from repeatedly presenting the movie containing the fearful object during sessions, or a cmbined effect. Therefore, it is recommended in future studies to use different stimuli in separate sessions. In conclusion, our study provides preliminary evidence for the effectiveness, safety and tolerablity of a novel intensified tDCS protocol on Entomophobia symptoms. Further studies are needed to determine the effectiveness of this intervention on different types of phobias. Finally, future studies are suggested to combine tDCS with neuroimaging for gaining mechanistic information about the tDCS effects.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Jaber Alizadehgoradel: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Validation, Supervision, Project administration, Conceptualization. Danial Nejadmasoom: Methodology, Writing – original draft & Software. Zahra Bigdeli and Mina Taherifard: Methodology, Investigation, Data curation. Zekrollah Morovati: Software, Methodology. Michael A. Nitsche: Writing – review & editing.

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Zanjan University (Ethics code: IR.ZNU.REC.1402.029). Participant provided written informed consent. All procedures were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration.

References

- Ozkan AT, Mumcuoğlu KY. [Entomophobia and delusional parasitosis]. Turkiye Parazitol Derg. 2008;32(4):366-70.

- Diagnostic, Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed. tr. Anxiety Disorders. American Psychiatric Association Washington, DC; 2022.

- Zsido AN, Kiss BL, Basler J, Birkas B, Coelho CM. Key factors behind various specific phobia subtypes. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):22281. [CrossRef]

- Ajdacic-Gross V, Rodgers S, Müller M, Hengartner MP, Aleksandrowicz A, Kawohl W, et al. Pure animal phobia is more specific than other specific phobias: epidemiological evidence from the Zurich Study, the ZInEP and the PsyCoLaus. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2016;266(6):567-77. [CrossRef]

- Eaton WW, Bienvenu OJ, Miloyan B. Specific phobias. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5(8):678-86. [CrossRef]

- Thng CEW, Lim-Ashworth NSJ, Poh BZQ, Lim CG. Recent developments in the intervention of specific phobia among adults: a rapid review. F1000Res. 2020;9. [CrossRef]

- Feske U, Chambless DL. Cognitive behavioral versus exposure only treatment for social phobia: A meta-analysis. Behavior Therapy. 1995;26(4):695-720. [CrossRef]

- Boschen MJ, Neumann DL, Waters AM. Relapse of Successfully Treated Anxiety and Fear: Theoretical Issues and Recommendations for Clinical Practice. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;43(2):89-100. [CrossRef]

- Wood BS, McGlynn FD. Research on Posttreatment Return of Claustrophobic Fear, Arousal, and Avoidance Using Mock Diagnostic Imaging. Behavior Modification. 2000;24(3):379-94. [CrossRef]

- Sudbrack-Oliveira P, Razza LB, Brunoni AR. Non-invasive cortical stimulation: Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS). Int Rev Neurobiol. 2021;159:1-22. [CrossRef]

- Cheng PWC, Louie LLC, Wong YL, Wong SMC, Leung WY, Nitsche MA, et al. The effects of transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) on clinical symptoms in schizophrenia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Asian Journal of Psychiatry. 2020;53:102392. [CrossRef]

- Kumari B, Singh A, Kar SK, Tripathi A, Agarwal V. Bifrontal-transcranial direct current stimulation as an early augmentation strategy in major depressive disorder: A single-blind randomised controlled trial. Asian Journal of Psychiatry. 2023;86:103637. [CrossRef]

- Parlikar R, Sreeraj VS, Chhabra H, Thimmashetty VH, Parameshwaran S, Selvaraj S, et al. Add-on HD-tDCS for obsessive-compulsive disorder with comorbid bipolar affective disorder: A case series. Asian Journal of Psychiatry. 2019;43:87-90. [CrossRef]

- Bikson M, Grossman P, Thomas C, Zannou AL, Jiang J, Adnan T, et al. Safety of Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation: Evidence Based Update 2016. Brain Stimul. 2016;9(5):641-61. [CrossRef]

- Alizadehgoradel J, Razavi SD, Shirani Z, Barati M, Taherifard M, Nejati V, et al. Targeting the left DLPFC and right VLPFC in unmarried romantic relationship breakup (love trauma syndrome) with intensified electrical stimulation: A randomized, single-blind, parallel-group, sham-controlled study. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2024;175:170-82. [CrossRef]

- Alizadehgoradel J, Molaei B, Barzegar Jalali K, Pouresmali A, Sharifi K, Hallajian A-H, et al. Targeting the prefrontal-supplementary motor network in obsessive-compulsive disorder with intensified electrical stimulation in two dosages: a randomized, controlled trial. Translational Psychiatry. 2024;14(1):78. [CrossRef]

- Alizadehgoradel J, Taherifard M, Vanderhasselt M-A. Safety and efficacy of intensified electrical stimulation targeting dorsolateral prefrontal cortex for the treatment of gambling disorder associated with online sports betting: a case report. International Gambling Studies.1-10. [CrossRef]

- Jafari E, Alizadehgoradel J, Pourmohseni Koluri F, Nikoozadehkordmirza E, Refahi M, Taherifard M, et al. Intensified electrical stimulation targeting lateral and medial prefrontal cortices for the treatment of social anxiety disorder: A randomized, double-blind, parallel-group, dose-comparison study. Brain Stimul. 2021;14(4):974-86. [CrossRef]

- Monte-Silva K, Kuo MF, Hessenthaler S, Fresnoza S, Liebetanz D, Paulus W, et al. Induction of late LTP-like plasticity in the human motor cortex by repeated non-invasive brain stimulation. Brain Stimul. 2013;6(3):424-32. [CrossRef]

- Alizadehgoradel J, Molaei B, Barzegar Jalali K, Pouresmali A, Sharifi K, Hallajian AH, et al. Targeting the prefrontal-supplementary motor network in obsessive-compulsive disorder with intensified electrical stimulation in two dosages: a randomized, controlled trial. Transl Psychiatry. 2024;14(1):78. [CrossRef]

- Alexandra Kredlow M, Fenster RJ, Laurent ES, Ressler KJ, Phelps EA. Prefrontal cortex, amygdala, and threat processing: implications for PTSD. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2022;47(1):247-59. [CrossRef]

- Giustino TF, Maren S. The Role of the Medial Prefrontal Cortex in the Conditioning and Extinction of Fear. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience. 2015;9. [CrossRef]

- Guhn A, Dresler T, Andreatta M, Müller LD, Hahn T, Tupak SV, et al. Medial prefrontal cortex stimulation modulates the processing of conditioned fear. Frontiers in behavioral neuroscience. 2014;8:44. [CrossRef]

- Vicario CM, Nitsche MA, Hoysted I, Yavari F, Avenanti A, Salehinejad MA, et al. Anodal transcranial direct current stimulation over the ventromedial prefrontal cortex enhances fear extinction in healthy humans: A single blind sham-controlled study. Brain Stimul. 2020;13(2):489-91. [CrossRef]

- Van't Wout M, Longo SM, Reddy MK, Philip NS, Bowker MT, Greenberg BD. Transcranial direct current stimulation may modulate extinction memory in posttraumatic stress disorder. Brain Behav. 2017;7(5):e00681. [CrossRef]

- Lee D, Guiomar R, Gonçalves Ó F, Almeida J, Ganho-Ávila A. Effects of transcranial direct current stimulation on neural activity and functional connectivity during fear extinction. Int J Clin Health Psychol. 2023;23(1):100342. [CrossRef]

- Yosephi MH, Ehsani F, Daghiani M, Zoghi M, Jaberzadeh S. The effects of trans-cranial direct current stimulation intervention on fear: A systematic review of literature. J Clin Neurosci. 2019;62:7-13. [CrossRef]

- Ganho-Ávila A, Gonçalves Ó F, Guiomar R, Boggio PS, Asthana MK, Krypotos AM, et al. The effect of cathodal tDCS on fear extinction: A cross-measures study. PLoS One. 2019;14(9):e0221282. [CrossRef]

- Ney LJ, Vicario CM, Nitsche MA, Felmingham KL. Timing matters: Transcranial direct current stimulation after extinction learning impairs subsequent fear extinction retention. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2021;177:107356. [CrossRef]

- Jafari E, Alizadehgoradel J, Pourmohseni Koluri F, Nikoozadehkordmirza E, Refahi M, Taherifard M, et al. Intensified electrical stimulation targeting lateral and medial prefrontal cortices for the treatment of social anxiety disorder: A randomized, double-blind, parallel-group, dose-comparison study. Brain Stimulation. 2021;14(4):974-86. [CrossRef]

- Diagnostic Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed. tr. Online Assessment Measures. 2024.

- Klieger DM. The Snake Anxiety Questionnaire as a Measure of Ophidophobia. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 1987;47(2):449-59. [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-García A, Valero-Aguayo L. Multimedia intervention for specific phobias: A clinical and experimental study. Psicothema. 2020;32(3):298-306. [CrossRef]

- Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4:561-71. [CrossRef]

- Hojat M, Shapurian R, Mehryar AH. Psychometric properties of a Persian version of the short form of the Beck Depression Inventory for Iranian college students. Psychol Rep. 1986;59(1):331-8. [CrossRef]

- Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, Steer RA. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: psychometric properties. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1988;56(6):893-7. [CrossRef]

- Hossein Kaviani H, Mousavi A S. Psychometric properties of the Persian version of Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI). Tehran University Medical Journal. 2008;66(2):136-40.

- Aitken RC. Measurement of feelings using visual analogue scales. Proc R Soc Med. 1969;62(10):989-93. [CrossRef]

- Thielscher A, Antunes A, Saturnino GB. Field modeling for transcranial magnetic stimulation: A useful tool to understand the physiological effects of TMS? Annu Int Conf IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2015;2015:222-5. [CrossRef]

- Grabner G, Janke AL, Budge MM, Smith D, Pruessner J, Collins DL. Symmetric atlasing and model based segmentation: an application to the hippocampus in older adults. Med Image Comput Comput Assist Interv. 2006;9(Pt 2):58-66. [CrossRef]

- Cobb AR, O’Connor P, Zaizar E, Caulfield K, Gonzalez-Lima F, Telch MJ. tDCS-Augmented in vivo exposure therapy for specific fears: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2021;78:102344. [CrossRef]

- Buchanan DM, Amare S, Gaumond G, D'Angiulli A, Robaey P. Safety and Tolerability of tDCS across Different Ages, Sexes, Diagnoses, and Amperages: A Randomized Double-Blind Controlled Study. J Clin Med. 2023;12(13). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).