1. Introduction

Firebreak zones, also known as firebreaks, are crucial in wildfire management, acting as strategic areas where vegetation has been removed or managed to prevent the spread of wildfires [

1]. These zones interrupt the continuity of fuels that wildfires rely on to grow and spread, effectively slowing down or even halting the advance of a fire [

2]. Firebreaks can be natural, such as rivers or rocky terrain, or man-made, such as roads, cleared strips of land, or areas where vegetation has been intentionally thinned or removed [

3].

Creating firebreaks involves various methods tailored to different environments and fire management needs, each with specific advantages [

1]. Mechanical cleaning is one of the most common techniques, involving the use of heavy machinery like bulldozers, chainsaws, and mowers to remove vegetation and other flammable materials from designated areas. Bulldozers are typically employed to clear large swaths of land quickly, while chainsaws and mowers are used for more precise removal of trees, shrubs, and grasses. This method is especially useful in areas where controlled burns are not feasible due to safety concerns or environmental conditions. However, it requires ongoing maintenance to ensure that the firebreak remains effective, as vegetation can quickly regrow and restore the fire hazard if not regularly managed [

2].

The maintenance of firebreaks has become increasingly critical as the frequency and intensity of wildfires rise due to climate change [

1]. As global temperatures climb, many regions experience longer dry seasons, reduced snowfall, and more intense heat waves, all of which contribute to drier vegetation and higher wildfire risks [

4]. Since the vegetation is always growing, continuous monitoring and maintenance of a firebreak is essential for effective wildfire management. Nowadays, semi-automatic remote sensing is used for the detection of firebreak maintenance operations [

2]. Such methodologies can help local and national authorities since they have a large firebreak network to monitor annually.

Forestry residues are divided into two major categories [

5]. Primary residues, including the materials remaining after logging operations (branches, stumps, treetops, bark, sawdust, etc) and secondary residues, including by-products from industrial wood-processing (bark, sawmill slabs, sawdust, wood chips, etc). Primary residues collected during creation or maintenance are a valuable resource and shouldn’t be considered as wastes [

6]. Unfortunately, only round wood (i.e., stemwood) is typically collected during firebreak maintenance and harvested from site, while the above ground biomass (such as branches, foliage and treetops) is disposed of adjacent to the collection site.

An emerging area of interest is renewable energy production from forest biomass residues [

7]. Indeed, there is a strategic increase of the installed electrical capacity using biomass residues in different countries, for example Portugal and China [

8]. In the second case, forest biomass is currently used to generate power and fuel with a share of 54.2% of the available energy sources. Anaerobic digestion is a mature technology that can be used for biogas production from forest biomass residues [

9]. Under appropriate conditions, the theoretical methane yields from lignocellulosic biomass and woody biomass were between 470 and 480 mL g

-1 VS [

9]. Actual biogas yield from residual forest biomass (e.g., pine needles, branches, and bark) with milling pre-treatment ranges from 30 up to 250 mL g

-1 VS [

6]. The collection and conversion of such biomass not only provides a renewable energy source but also help reduce the risk of forest fires by removing combustible materials from the forest floor [

7].

This study aims to address this intersection of fire management and energy recovery by evaluating the biomass residues generated during the maintenance of firebreak zones and forest road networks on Thasos Island, Greece. Specifically, it focuses on identifying the type and quantity of vegetation removed, analyzing its physicochemical characteristics, and assessing its potential for biogas production through anaerobic digestion. By quantifying the biogas yields of different biomass types, the study seeks to identify which species contribute most significantly to both fire hazard reduction and renewable energy generation. The overarching goal is to inform more strategic and sustainable firebreak maintenance practices – ones that not only reduce wildfire risk but also contribute to circular economy models by valorizing what is typically treated as waste. In doing so, this research contributes to a growing body of work exploring how land management and energy systems can be integrated to achieve greater ecological and economic resilience in fire-prone regions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Site Selection and Description

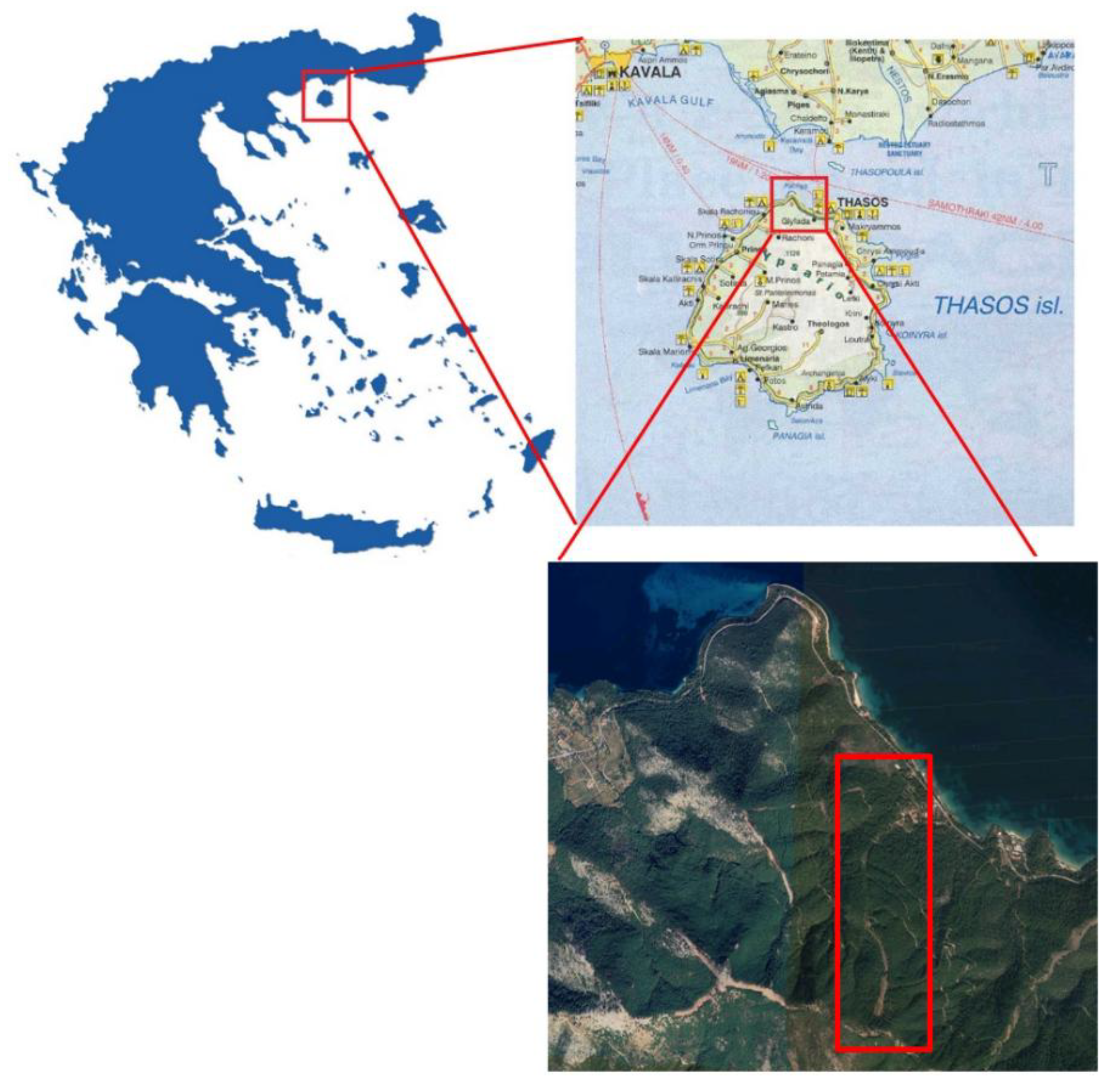

The firebreak examined was situated in Thasos Island (north Greece) ranging between 40 and 440 m altitude (40.784382, 24.660910 to 40.772239, 24.659652). The forest cover of the island constitutes 11,070 ha (full cover 3,033 ha, partially forest cover 4,218 ha, shrubs 3,819 ha) from a total area of 37,226 ha. The firebreak network includes 82 firebreaks with a total area of 437 ha. The firebreak zone examined was located between “La scala” and “Glikadi beach”. It was 40 m wide and 1500 m in length, with a total area of 3 ha. Pinus brutia was the most common species of the island and the forests. In the largest part of Pinus brutia forests there was a ground layer consisting of shrub-like species with unfavorable effect on the natural regeneration of the forest stands. In this work the understory vegetation and shrubs were also collected including Medicago sativa, Verbascum sinuatum, Cistus creticus and Cichorium intybus. The climate of Thasos is transitional Mediterranean with quite cold, rainy winters and hot, sunny summers.

Figure 1.

Location of Thasos Island and the firebreak under investigation.

Figure 1.

Location of Thasos Island and the firebreak under investigation.

2.2. Vegetation Removal Process

Daily 10-15 m of firebreak was cleared depending on the number of trees present. Forest biomass in firebreak consisted mostly of Pinus brutia trees with different sizes. Before clearing the site, the number and diameter of trees and the presence of low vegetation were recorded. The trees were then cut down using chainsaws, the branches and treetops were removed, while the tree trunk was cut to assist harvesting. The tree branches from each study site were collected to the ground, compressed by foot and the volume occupied (height, length, width) was determined. Twenty-five (25) sites, each with an area between 200 to 400 m2 were studied in detail. Vegetation removal was performed manually using a team, including chainsaws, axes and shears for cutting tree branches and low vegetation.

2.3. Biomass Collection and Classification

Samples of different forest biomass residues (tree branches and shrubs) were transported to the laboratory to determine their apparent density, i.e., to determine the fresh weight per unit volume of material. For this purpose, the quantity of material used was 1 m2 and a height of around 5 cm. Moreover, the forest biomass samples were used to evaluate the distribution of shoot/trunk and foliage/flower. For this reason, five random samplings were carried out from different points of each of the five predominant species found in the area. The species were Pinus brutia, Verbascum sinuatum, Medicago sativa, Cistus creticus and Cichorium intybus. After weighing the pinus branches were separated from the leaves. For the rest of the plant species the stem was separated from the flowers and leaves. All fractions were weighed as fresh matter. In this work, the biomass samples were digested without separation, except for pine tree sample where only the needles were ground.

2.4. Biogas Production Potential

Biogas production potential from the examined forest biomass residues was determined in laboratory-scale anaerobic digesters with 2 L working volume. The digesters were operated under mesophilic conditions (38-39

oC) in batch mode using a substrate to inoculum ratio of 0.25. Biogas production was measured using acidified water displacement in reverse columns. All samples were milled (using a kitchen grinder) before use in anaerobic digestion experiments. The biogas methane content was determined using an alkaline trap. Methane yield was expressed per kg volatile solids added at standard temperature and pressure conditions (STP).

Figure 2 show the examined forest biomass residues before and after milling pre-treatment. Moisture content, totals solids (TS) and volatile solids (VS) of different biomass samples were determined according to standard methods [

10].

3. Results

3.1. Biomass Quantity and Type

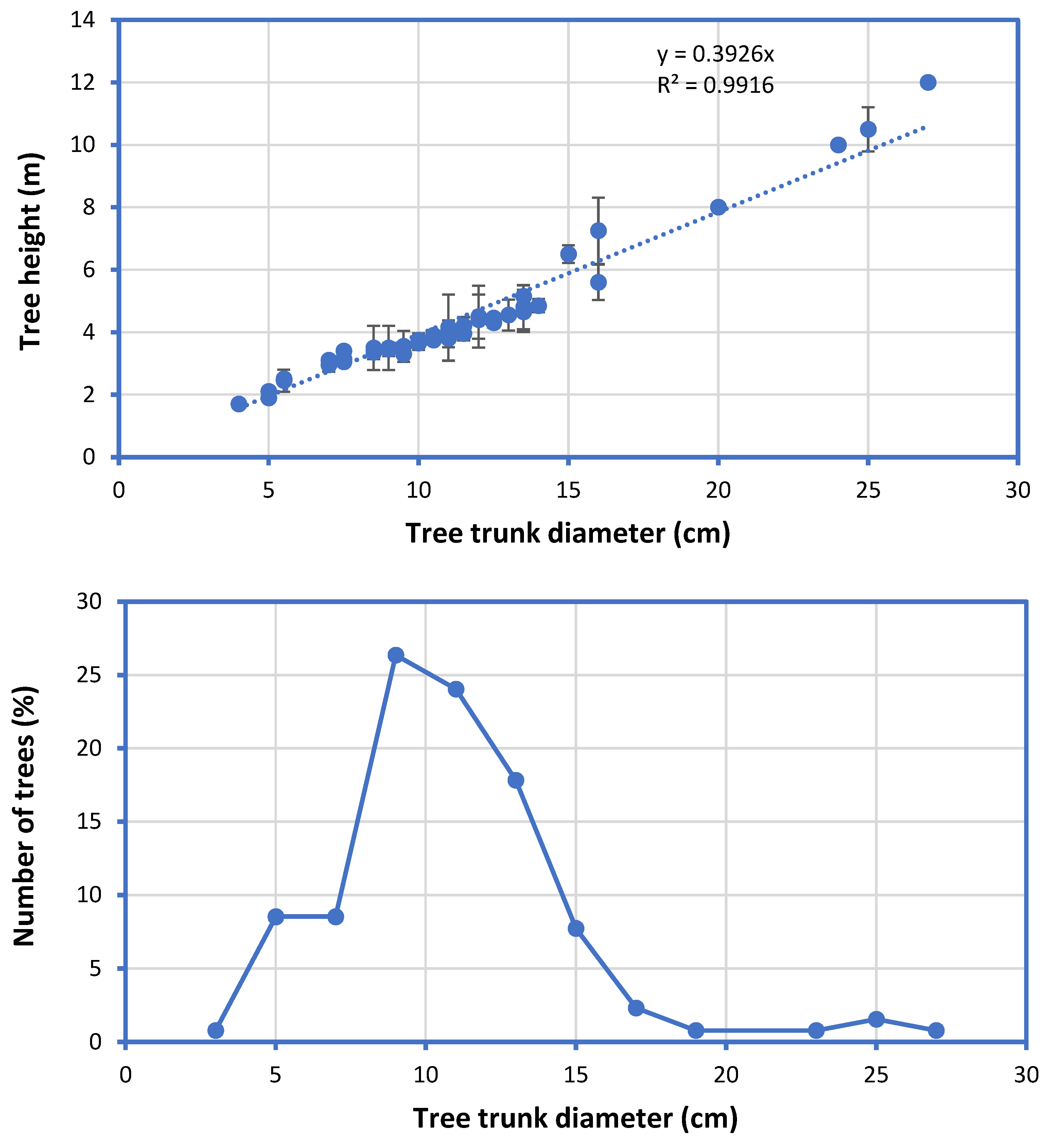

Figure 3 presents the tree height and trunk diameter data of

Pinus brutia trees removed from 25 sampling locations within the firebreak zone on Thasos Island. Tree heights ranged from 2 to 12 meters, and trunk diameters varied between 4 and 27 cm. Maintenance operations involved felling these trees and separating trunks from branches, with branch volume and pine needle content recorded on site.

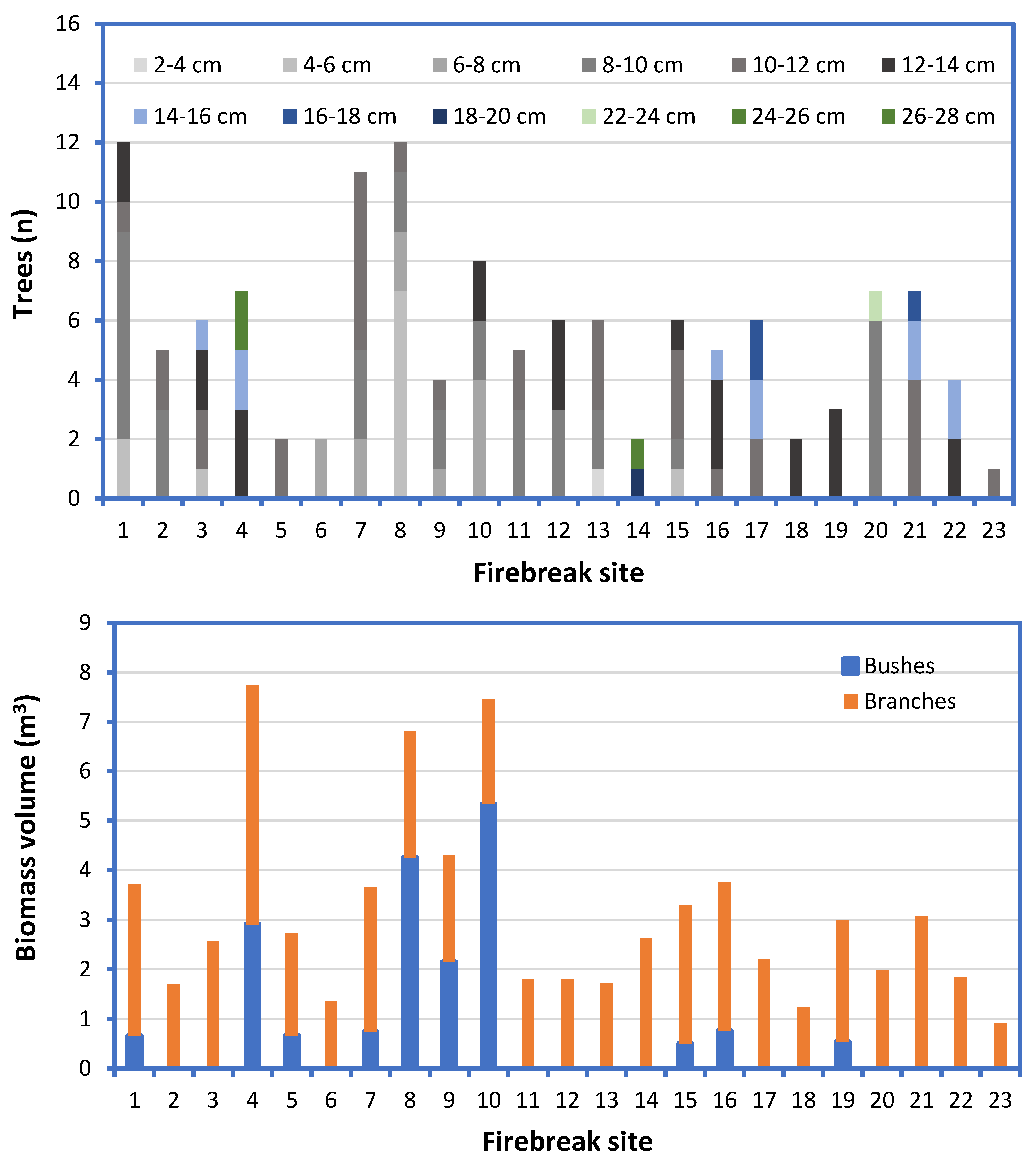

On average, 22 ± 11 trees were removed per 1000 m

2 of firebreak zone, corresponding to a branch volume of 11 ± 8 m

3 per 1000 m

2 (

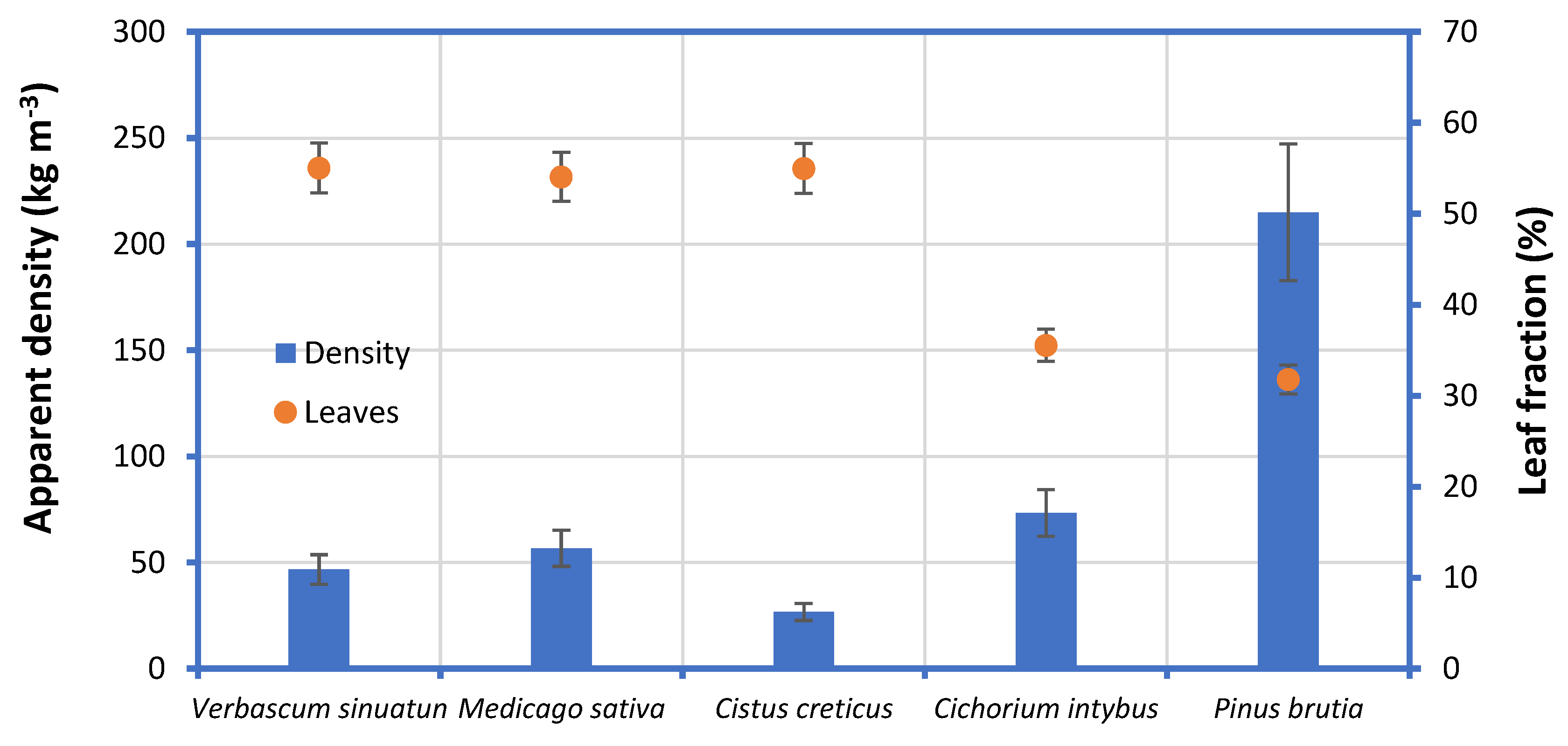

Figure 4). The apparent density of

Pinus brutia branches was estimated at 215 kg m

-3. Pine needles represented 31.7% of the branch biomass by weight, as shown in

Figure 5. Low-lying vegetation and shrub biomass included species such as

Verbascum sinuatum,

Medicago sativa,

Cistus creticus, and

Cichorium intybus. Biomass components were classified into leaves, stems, and flowers. As depicted in

Figure 5,

Pinus brutia had the lower leaf fraction (32%), compared to

Verbascum sinuatum,

Medicago sativa and

Cistus creticus (55%).

3.2. Biomass Composition and Biogas Production

Table 1 summarizes the key physicochemical properties of the biomass samples.

Cistus creticus exhibited the highest moisture content (670 g kg

-1), while

Pinus brutia needles had 537 g kg

-1. Volatile solids (VS) content ranged from 86.9% (dry basis) (

Cichorium intybus) to 97.2 % (

Pinus brutia).

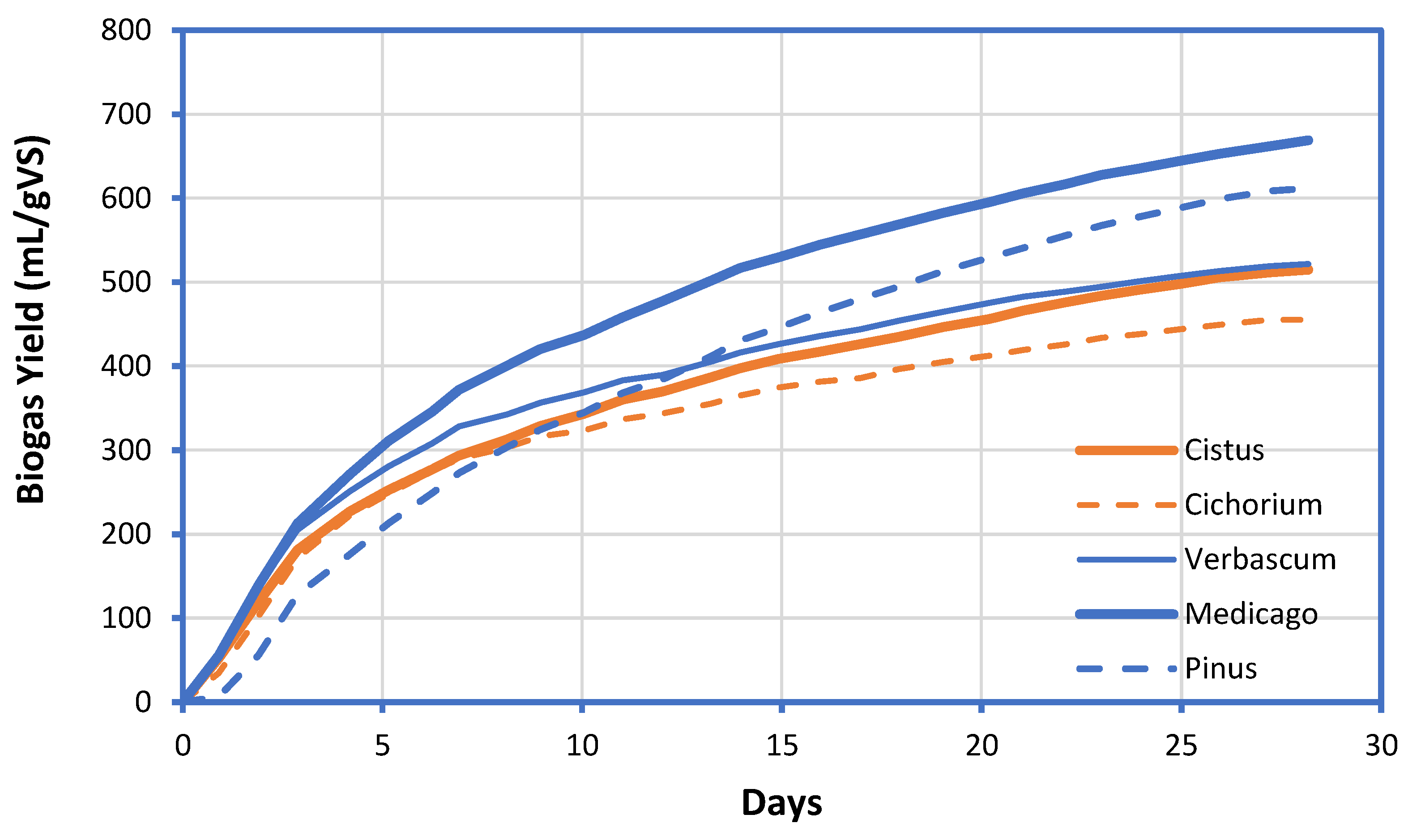

Biogas yields from batch anaerobic digestion tests are shown in

Figure 6.

Medicago sativa yielded the highest biogas production at 669 ± 110 m

3 tn

-1 VS, followed by

Pinus brutia needles at 612 ± 83 m

3 tn

-1 VS. The lowest biogas yield was observed in

Cichorium intybus, with 455 ± 32 m

3 tn

-1 VS. These results align with the VS content and moisture levels recorded in

Table 1. Biogas yield from pine needles was negligible during the first day of anaerobic digestion experiments which is indicative of inhibition or low bioavailability. Biogas production typically plateaued within 30 days from all biomass types, indicating effective degradation within the experimental timeframe. Notably, all biomass samples demonstrated a biogas yield comparable to typical energy crops (150-250 m

3 tn

-1 FM). Based on the current research, the estimated specific biogas yield from

Pinus brutia needles could reach 230 m

3 per 1000 m

2 of firebreak.

The data confirms that firebreak vegetation, particularly pine needle biomass, holds strong potential for renewable energy generation via anaerobic digestion. These insights also support more strategic firebreak management by prioritizing the removal of high-biomass and high-yielding species.

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications for Firebreak Management

Wildfires can spread rapidly when dry vegetation is abundant, underscoring the importance of well-maintained firebreaks. In Europe, roughly 65,000 wildfires occur annually, burning about 500,000 hectares – a statistic that highlights the need for effective fuel management to curb such losses [

11]. Regular maintenance of firebreaks is essential for them to remain effective. Without periodic clearing, they can quickly become overgrown with grasses, shrubs, and saplings, which replenishes the fuel and diminishes the firebreak’s protective value. Understanding the types and quantities of biomass present in firebreak zones allows managers to optimize their maintenance strategies. Different vegetation types burn in different ways, significantly influencing fire behavior [

12]. Fine fuels like dry grasses ignite easily and burn very rapidly, leading to fast-moving flames [

13]. These flashy fuels can cause a fire to race across a landscape, so it is essential to remove or reduce them within firebreaks. In contrast, larger and denser vegetation (such as thick shrubs or small trees) may not ignite as readily, but once they are lit they produce longer-lasting flames and can sustain fire for a greater duration. Such heavy fuels can generate intense heat and tall flame lengths, potentially allowing wildfire to breach a firebreak if not properly managed [

14]. By analyzing the biomass profile in each section of a firebreak – for instance, identifying areas dominated by fast-burning grasses versus areas with woody shrubs – land managers can tailor their clearing and thinning practices accordingly. Dry, fine fuels would be prioritized for aggressive removal, whereas denser or higher-moisture vegetation might by thinned or pruned to prevent sustained burning [

15]. Areas that accumulate large amounts of biomass quickly (due to fast-growing species or invasive plants) will require more frequent intervention to keep fuels in check – whether through mechanical clearing, livestock grazing, or periodic controlled burns [16-18]. In some cases, applying fire-retardant chemicals or reseeding a firebreak with less flammable plant species could be strategies to maintain a low fuel load [19, 20].

4.2. Potential for Renewable Energy

Maintaining firebreaks produces significant amounts of vegetative residue – branches, brush, grasses, and leaf litter – which historically have been treated as waste (often left in place or burned on site) [

21]. However, these biomass residues hold considerable potential as a sustainable energy source [

22,

23]. Turning firebreak trimmings and forest residues into bioenergy (for instance, by producing biogas or wood chips for combustion) can transform a fire safety task into an opportunity [

24]. Recent studies support this dual benefit: by prioritizing the removal of certain high-biomass, high-fuel vegetation types, fire management efforts can both reduce wildfire hazards and supply valuable feedstock for bioenergy production [

25].

Not all biomass is equal in its energy potential, so understanding which vegetation yields the most usable energy is key. The results of this study showed that some vegetation types common in fire-prone areas have remarkably high biogas yields when processed via anaerobic digestion. For instance, Medicago sativa (alfalfa, a fast growing perennial herbaceous legume) and Pinus brutia needles stood out for their methane generation, yielding on the order of 600-670 m3 biogas per ton volatile solids – significantly higher than other plant species like Cichorium intybus (~455 m3 tn-1 VS) under the same conditions. In practice, dense shrubs and invasive grasses often accumulate substantial biomass quickly, and this trait translates into significant biogas production potential when those plants are harvested.

Anaerobic digestion (AD) is one of the most promising ways to convert firebreak biomass into usable energy (biogas) [

26]. AD is a well-established technology where microbes decompose organic matter in oxygen-free tanks, producing biogas that can be burned for heat and power or refined into biomethane fuel [

27,

28]. Forest and brush residues are more fibrous and lignified than typical energy crops or food waste, but under the right conditions they can still produce a substantial amount of biogas [

29,

30]. In fact, theoretical studies indicate that lignocellulosic biomass (like wood and leaves) contain enough degradable material to yield around 470-480 mL of biogas per gram of volatile solids, and while real-word yields are lower, trials with pre-treated forest residues have achieved 30-350 mL CH

4 g

-1 VS [

31,

32]. For example, milling pine needles and branches to a fine particle size has been shown to significantly improve gas yields, with pine biomass producing methane in the upper part of that range in batch reactors [

33,

34].

Bioenergy from forest biomass is often considered carbon-neutral when harvested sustainably: the CO

2 released from burning biogas or wood is roughly equivalent to the CO

2 that the plants absorbed while growing [

35]. Additionally, by offsetting the use of fossil fuels, bioenergy derived from firebreak residues can further contribute to climate-change mitigation [

36]. It’s worth noting that wildfires themselves are significant sources of greenhouse gases; for example, a single large wildfire can release hundreds of thousands of tons of CO

2 in just days [

37,

38]. Therefore, preventing high-intensity fires through fuel removal, and utilizing that biomass in a cleaner energy system, can have a meaningful emissions benefit in the broader picture.

From an economic perspective, integrating biogas or biomass power production with firebreak clearing can help defray the costs of wildfire prevention and even create local economic opportunities. For instance, in parts of the western United States, the establishment of biomass power facilities has provided an outlet for small trees and woody debris from forest thinning projects, offsetting what would otherwise be purely disposal costs [39-41]. In a similar way, a community-scale biogas plant could take in vegetation cleared from local firebreaks and produce electricity or heat for the community, effectively turning a fire safety by-product into a source of revenue or energy savings [

42,

43]. Some countries already capitalize on forest biomass in their energy mix – in China, for example, forest residues account for over 50% of biomass-based energy production, demonstrating the viability of large-scale biomass utilization [44-46].

4.3. Challenges and Future Considerations

While the idea of repurposing firebreak biomass for biogas or other energy uses is promising, several practical challenges must be considered before such a strategy can be scaled up widely. The vegetation removed from firebreaks is heterogeneous – a mix of grasses, leaves, needles, and woody debris – each with different combustion or digestion characteristics [

47]. For instance, lignin-rich materials tend to resist decomposition and yield less methane unless given special pre-treatment [

48]. In experiments, some forest biomass samples (like dry leaf litter and bark) produced as little as 20–80 mL of methane per gram of volatile solids, whereas more easily degraded organic matter yields much more [

6]. The need for tailored pre-treatments (e.g., grinding to sawdust, thermal or chemical treatment to break down fibers) is a technical and economic hurdle, as it raises the processing cost and complexity [

49,

50]. There could also be issues with digester stability; for example, tree oils and tannins could inhibit microbial activity if concentrations are high [

51]. The results of our study revealed a slight inhibition in biogas production during the first day of anaerobic digestion experiments of

Pinus brutia needles attributed to the essential oils present therein.

One of the most significant practical challenges is gathering and transporting the biomass from widely distributed firebreaks to a central processing site. Firebreaks and fuel breaks often stretch across remote or rugged terrain. The biomass available is typically spread out in a linear fashion, not piled conveniently in one location. Collecting it requires mobilizing crews and machinery (chippers, loaders, trucks) along sometimes difficult access roads or trails. The low bulk density of materials like tree branches, brush, and straw means that they take up a lot of space relative to their weight, making transport inefficient [

52]. This inefficiency drives up transportation costs, especially if the distance to the bioenergy facility is great. Potential solutions include establishing decentralized digesters near forest areas minimizing the need for biomass transport. Heavy machinery like masticators or brush cutters can speed up fuel break clearing, but not all areas are accessible to such equipment (steep slopes, protected zones, or areas without roads). In some cases, manual labor by saw crews may be the only way to clear a firebreak, which is slow and costly. Furthermore, once biomass is cut, additional steps are needed to gather and load it.

It’s also important to ensure that removing biomass from ecosystems for energy doesn’t inadvertently cause ecological harm [

53]. Dead wood and plant litter in forests do play roles in nutrient cycling, soil protection, and providing habitat for wildlife. If a “fuel break” is too thoroughly cleaned out, it might lead to erosion or loss of soil moisture retention [

54]. Managers will need to balance fire safety with conservation, perhaps by leaving some level of residue or by timing operations to minimize impact [

55].

5. Conclusions

In summary, integrating firebreak management with biomass-based energy production offers an innovative way to enhance wildfire preparedness while contributing to renewable energy goals. The results on biomass types and quantities in the examined firebreaks reveal that by identifying and removing the most troublesome fuel types (those that not only drive severe fires but also happen to be good energy sources), we can make forests safer and extract a useful product in the process. However, realizing this vision on a large scale will require overcoming significant technical, logistical, and economic challenges. If these challenges are met, communities in fire-prone regions could implement programs where regular firebreak maintenance yields not just safety benefits but also locally produced biogas or power – turning a necessary firefighting expense into a partial asset.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.D. and V.D.; methodology, V.D.; investigation, C.D., A.E. and A.L.; data curation, V.D.; writing—original draft preparation, V.D.; writing—review and editing, A.E., C.D. and A.L.; supervision, V.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Christos Michailidis for his assistance with the laboratory work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Aubard, V.; Pereira-Pires, J. E.; Campagnolo, M. L.; Pereira, J. M.; Mora, A.; Silva, J. M. Fully automated countrywide monitoring of fuel break maintenance operations. Remote Sens. 2020, 12(18), 2879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira-Pires, J. E.; Aubard, V.; Ribeiro, R. A.; Fonseca, J. M.; Silva, J. M.; Mora, A. Semi-automatic methodology for fire break maintenance operations detection with sentinel-2 imagery and artificial neural network. Remote Sens. 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ascoli, D.; Russo, L.; Giannino, F.; Siettos, C.; Moreira, F. Firebreak and fuelbreak. In Encyclopedia of wildfires and wildland-urban interface (WUI) fires; Manzello, S., Eds.; Springer, Cham, 2018; pp. 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Abatzoglou, J. T.; Williams, A. P. Impact of anthropogenic climate change on wildfire across western US forests. PNAS 2016, 113(42), 11770–11775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karan, S. K.; Hamelin, L. Towards local bioeconomy: A stepwise framework for high-resolution spatial quantification of forestry residues. Renewable Sustainable Energy Rev. 2020, 134, 110350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eftaxias, A.; Passa, E. A.; Michailidis, C.; Daoutis, C.; Kantartzis, A.; Diamantis, V. Residual forest biomass in pinus stands: accumulation and biogas production potential. Energies 2022, 15(14), 5233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Wang, Y.; Van Le, Q.; Yang, H.; Hosseinzadeh-Bandbafha, H.; Yang, Y.; Sonne, C.; Tabatabaei, M.; Lam, S.S.; Peng, W. An overview on the conversion of forest biomass into bioenergy. Front. Energy Res. 2021, 9, 684234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Costa, T. P.; Quinteiro, P.; Arroja, L.; Dias, A. C. Environmental comparison of forest biomass residues application in Portugal: Electricity, heat and biofuel. Renewable Sustainable Energy Rev. 2020, 134, 110302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijeyekoon, S. L.; Vaidya, A. A. Woody biomass as a potential feedstock for fermentative gaseous biofuel production. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2021, 37(8), 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, E.W.; Bridgewater, L. ; American Public Health Association (Eds.) Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater; American Public Health Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- San-Miguel-Ayanz, J.; Schulte, E.; Schmuck, G.; Camia, A.; Strobl, P.; Liberta, G.; Giovando, C.; Boca, R.; Sedano, F.; Kempeneers, P.; McInerney, D.; Withmore, C.; de Oliveira, S.S.; Rodrigues, M.; Durrant, T.; Corti, P.; Oehler, F.; Vilar, L.; Amatulli, G. Comprehensive monitoring of wildfires in Europe: the European forest fire information system (EFFIS). In Approaches to managing disaster-Assessing hazards, emergencies and disaster impacts; Tiefenbacher, J., Ed.; Intechopen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2012; pp. 87–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loudermilk, E. L.; O’Brien, J. J.; Goodrick, S. L.; Linn, R. R.; Skowronski, N. S.; Hiers, J. K. Vegetation’s influence on fire behavior goes beyond just being fuel. Fire Ecol. 2022, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hantson, S.; Andela, N.; Goulden, M. L.; Randerson, J. T. Human-ignited fires result in more extreme fire behavior and ecosystem impacts. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H. H.; Finney, M. A.; Song, Z. L.; Wang, Z. S.; Li, X. C. Ecological techniques for wildfire mitigation: Two distinct fuelbreak approaches and their fusion. For. Ecol. Manage. 2021, 495, 119376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awadhiya, A. (2025). Wildfires: Principles, Management Strategies, and Best Practices, 1st ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, P. E.; Porter, B. A.; Pellant, M.; Dyer, K.; Norton, T. P. Evaluating the efficacy of targeted cattle grazing for fuel break creation and maintenance. Rangeland Ecol. Manage. 2023, 89, 69–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro Rego, F.; Morgan, P.; Fernandes, P.; Hoffman, C. Fire science: from chemistry to landscape management; Springer Textbooks in Earth Sciences, Geography and Environment. Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 509–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreelakshmi, P. K.; AswinKrishna, M. V.; Maurya, L. L. Wildfire management and prevention strategies. In Advances in Forestry and Agro-forestry, 1st ed.; Stella International Publication: Haryana, India, 2023; pp. 400–437. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, K.; Qin, Z.; Gao, W.; Wang, Z. Refining Ecological Techniques for Forest Fire Prevention and Evaluating Their Diverse Benefits. Fire 2024, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabipour, H.; Shi, H.; Wang, X.; Hu, X.; Song, L.; Hu, Y. Flame retardant cellulose-based hybrid hydrogels for firefighting and fire prevention. Fire Technol. 2022, 58, 2077–2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, T. P.; Sullivan, D. S.; Klenner, W. Fate of postharvest woody debris, mammal habitat, and alternative management of forest residues on clearcuts: a synthesis. Forests 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titus, B. D.; Brown, K.; Helmisaari, H. S.; Vanguelova, E.; Stupak, I.; Evans, A.; Clarke, N.; Guidi, C.; Bruckman, V.J.; Varnagiryte-Kabasinskiene, I.; Armolaitis, K.; de Vries, W.; Hirai, K.; Kaarakka, L.; Hogg, K.; Reece, P. Sustainable forest biomass: A review of current residue harvesting guidelines. Energy, Sustainability Soc. 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clauser, N. M.; González, G.; Mendieta, C. M.; Kruyeniski, J.; Area, M. C.; Vallejos, M. E. Biomass waste as sustainable raw material for energy and fuels. Sustainability 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamantis, V.; Eftaxias, A.; Stamatelatou, K.; Noutsopoulos, C.; Vlachokostas, C.; Aivasidis, A. Bioenergy in the era of circular economy: Anaerobic digestion technological solutions to produce biogas from lipid-rich wastes. Renewable Energy 2021, 168, 438–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastos, T.; Teixeira, L.; Nunes, L. J. Fire Risk Reduction and Recover Energy Potential: A Disruptive Theoretical Optimization Model to the Residual Biomass Supply Chain. Fire 2024, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alengebawy, A.; Ran, Y.; Osman, A. I.; Jin, K.; Samer, M.; Ai, P. Anaerobic digestion of agricultural waste for biogas production and sustainable bioenergy recovery: a review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2024, 22, 2641–2668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M. M.; Wright, M. M. Anaerobic digestion fundamentals, challenges, and technological advances. Physical Sciences Reviews 2023, 8, 2819–2837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obileke, K.; Nwokolo, N.; Makaka, G.; Mukumba, P.; Onyeaka, H. Anaerobic digestion: Technology for biogas production as a source of renewable energy—A review. Energy Environ. 2021, 32, 191–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, A.; Kumar, A.; Somya, A. Forestry and Agricultural Residues-Based Wastes: Fundamentals, Classification, Properties, and Applications. In Biomass Wastes for Sustainable Industrial Applications. In Biomass Wastes for Sustainable Industrial Applications, 1st ed.; Verma., C., Dubey, S., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, USA, 2024; pp. 95–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwokolo, N.; Mukumba, P.; Obileke, K.; Enebe, M. Waste to energy: A focus on the impact of substrate type in biogas production. Processes 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, M. M.; Forgács, G.; Sárvári Horváth, I. Biogas from lignocellulosic materials. In Lignocellulose-based bioproducts. Biofuel and Biorefinery Technologies, volume 1; Karimi, K., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 207–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, M.; Balan, V.; Varjani, S.; Tyagi, V. K.; Chaudhary, G.; Pareek, N.; Vivekanand, V. Multidisciplinary pretreatment approaches to improve the bio-methane production from lignocellulosic biomass. BioEnergy Res. 2023, 16, 228–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahajan, R.; Chandel, S.; Puniya, A. K.; Goel, G. Effect of pretreatments on cellulosic composition and morphology of pine needle for possible utilization as substrate for anaerobic digestion. Biomass Bioenergy 2020, 141, 105705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, M.; Chakravarty, S.; Kishore, B.; Kundu, K. Lab-scale optimization of biogas production from pine needles co-digested with cow dung: influence of varying mixing ratio, pretreatment and temperature regime. Biofuels 2025, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirschbaum, M. U. To sink or burn? A discussion of the potential contributions of forests to greenhouse gas balances through storing carbon or providing biofuels. Biomass Bioenergy. 2003, 24(4-5), 297-310. [CrossRef]

- Garvie, L. C.; Roxburgh, S. H.; Ximenes, F. A. Greenhouse gas emission offsets of forest residues for bioenergy in Queensland, Australia. Forests 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knorr, W.; Jiang, L.; Arneth, A. Climate, CO2 and human population impacts on global wildfire emissions. Biogeosciences 2016, 13, 267–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; Sarkar, S. Impact of wildfires on some greenhouse gases over continental USA: A study based on satellite data. Remote Sens. Environ. 2017, 188, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page-Dumroese, D. S.; Jurgensen, M.; Terry, T. Maintaining soil productivity during forest or biomass-to-energy thinning harvests in the western United States. Western Journal of Applied Forestry 2010, 25, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, D. L.; Monserud, R.; Dykstra, D. Biomass utilization for bioenergy in the western United States. For. Prod. J. 6: (1/2); -16.

- Galik, C. S.; Benedum, M. E.; Kauffman, M.; Becker, D. R. Opportunities and barriers to forest biomass energy: A case study of four US states. Biomass Bioenergy 2021, 148, 106035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Zhang, C.; Yang, G.; Feng, Y.; Ren, G.; Han, X. Comparison of biogas development from households and medium and large-scale biogas plants in rural China. Renewable Sustainable Energy Rev. 2014, 33, 204–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amirante, R.; Bruno, S.; Distaso, E.; La Scala, M.; Tamburrano, P. A biomass small-scale externally fired combined cycle plant for heat and power generation in rural communities. Renewable Energy Focus 2019, 28, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junfeng, L.; Runqing, H. Sustainable biomass production for energy in China. Biomass Bioenergy 2003, 25, 483–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Zhang, A.; Lam, S. K.; Zhang, X.; Thomson, A. M.; Lin, E.; Jiang, K.; Clarke, L.E.; Edmonds, J.A.; Kyle, P.G.; Yu, S.; Zhou, Y.; Zhou, S. An integrated assessment of the potential of agricultural and forestry residues for energy production in C hina. GCB Bioenergy 2016, 8, 880–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, T.; Ke, J.H.; Zhou, S.; Xie, G. H. Estimation of the quantity and availability of forestry residue for bioenergy production in China. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 162, 104993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, G.; Lestander, T. A.; Geladi, P.; Xiong, S. Biomass properties in association with plant species and assortments I: A synthesis based on literature data of energy properties. Renewable Sustainable Energy Rev. 2012, 16, 3481–3506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliva, A.; Papirio, S.; Esposito, G.; Lens, P. N. Pretreatment of lignocellulosic materials to enhance their methane potential. In Renewable Energy Technologies for Energy Efficient Sustainable Development, Sinharoy, A., Lens, P.N.L., eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Dieter Jürgen Korz, I. Biogas production: Mechanical and thermal pre-treatment technologies. In Biogas: Fundamentals, Process, and Operation, Tabatabaei, M., Ghanavati, H., eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 117–133. [Google Scholar]

- Poddar, B. J.; Nakhate, S. P.; Gupta, R. K.; Chavan, A. R.; Singh, A. K.; Khardenavis, A. A.; Purohit, H. J. A comprehensive review on the pretreatment of lignocellulosic wastes for improved biogas production by anaerobic digestion. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 19, 3429–3456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashama, C.; Ijoma, G. N.; Matambo, T. S. The effects of phytochemicals on methanogenesis: insights from ruminant digestion and implications for industrial biogas digesters management. Phytochem. Rev. 2021, 20, 1245–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pari, L.; Suardi, A.; Santangelo, E.; García-Galindo, D.; Scarfone, A.; Alfano, V. Current and innovative technologies for pruning harvesting: A review. Biomass Bioenergy 2017, 107, 398–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, A. B.; Francis, V.; Nandakumar, N. Environmental Effects and Potential Solutions in the Realm of Biomass Management. In Handbook of Advanced Biomass Materials for Environmental Remediation, Thomas, S., Chirayil C.J., Varghese R.T., eds.; Springer Nature Singapore: Gateway East, Singapore, 2024; pp. 313–335. [Google Scholar]

- Zuazo, V. H. D.; Pleguezuelo, C. R. R. Soil-erosion and runoff prevention by plant covers: a review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2008, 28, 65–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, A. J. D.; Alegre, S. P.; Coelho, C. O. A.; Shakesby, R. A.; Pascoa, F. M.; Ferreira, C. S. S.; Keizer, J.J.; Ritsema, C. Strategies to prevent forest fires and techniques to reverse degradation processes in burned areas. Catena 2015, 128, 224–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).