Submitted:

05 August 2025

Posted:

05 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

- Infant: from one month of age to one year of age.

-

Older infant: from the first year of life to two years of age. The infant has an accelerated growth rate that gradually decreases towards the second year of life when the growth rate stabilizes [3] The recommendations of the WHO and UNICEF for optimal infant nutrition, as established in the Global Strategy are:

- Exclusive breastfeeding during the first 6 months of life

-

Start adequate and safe complementary feeding from 6 months of age, maintaining breastfeeding until two years of age or more [2].The Spanish Academy of Pediatrics (AEP) reminds us of the periods of child feeding as defined by the Nutrition Committee of the American Academy of Pediatrics:Breastfeeding period: comprises the first 6 months of life, during which the child's diet should be exclusively breast milk or, failing that, infant formula. Breast milk protein is of optimal quality and is the reference standard [4]. Breastfeeding should begin early, in the first hours after birth, avoiding bottle feeding. This promotes mother-child contact and provides the first stimulus for milk secretion.It is well established that breastfeeding decreases the risk of death in childhood and protects the child against infections, necrotizing enterocolitis, obesity, type 2 diabetes, leukemia and promotes neurodevelopment [5]

| BENEFITS OF BREASTFEEDING | |

| FOR THE CHILD | FOR THE MOTHER |

| Decrease in infectious gastrointestinal and respiratory diseases | Decreased postpartum bleeding |

| Protection against allergic diseases such as asthma, rhinitis and atopy | Decreased menstrual bleeding and lactational amenorrhea |

| Protection against obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and type 2 diabetes mellitus during adulthood | Decreased risk of high blood pressure, obesity, type 2 diabetes, and dyslipidemia |

| Decreased risk of developing leukemia during childhood | Longer intergenic period |

| Reducing the risk of developing necrotizing enterocolitis in newborns | Faster recovery of pre-pregnancy weight |

| Reduction in the risk of inflammatory bowel diseases and gluten allergies | Decreased risk of breast and ovarian cancer |

| Better neurodevelopment and better IQ score | |

| Lower risk of attention deficit, autism spectrum disorder, and behavioral disorders | |

|

Emotional affective relationship that favors the child's psychological development and mother reinforces her maternal behavior | |

Co-Sleeping and Night Feeding

Materials and Methods

Study Data and Sample

Inclusion Criteria

Exclusion Criteria

Procedures

Method

Information Collection or Processing: Ethical Aspects

Results and Discussion

| AGE MONTHS | Percentage |

| 4 | 21.05% |

| 5 | 15.79% |

| 6 | 5.26% |

| 7 | 21.05% |

| 8 | 15.79% |

| 9 | 10.53% |

| 10 | 5.26% |

| 11 | 5.26% |

| Total | 100.00% |

| Age in months | n | % |

| 4 | 14 | 15.9 |

| 5 | 14 | 15.9 |

| 6 | 9 | 10.2 |

| 7 | 14 | 15.9 |

| 8 | 14 | 15.9 |

| 9 | 9 | 10.2 |

| 10 | 5 | 5.7 |

| 11 | 4 | 4.5 |

| 12 | 5 | 5.7 |

| Total | 88 | 100.00 |

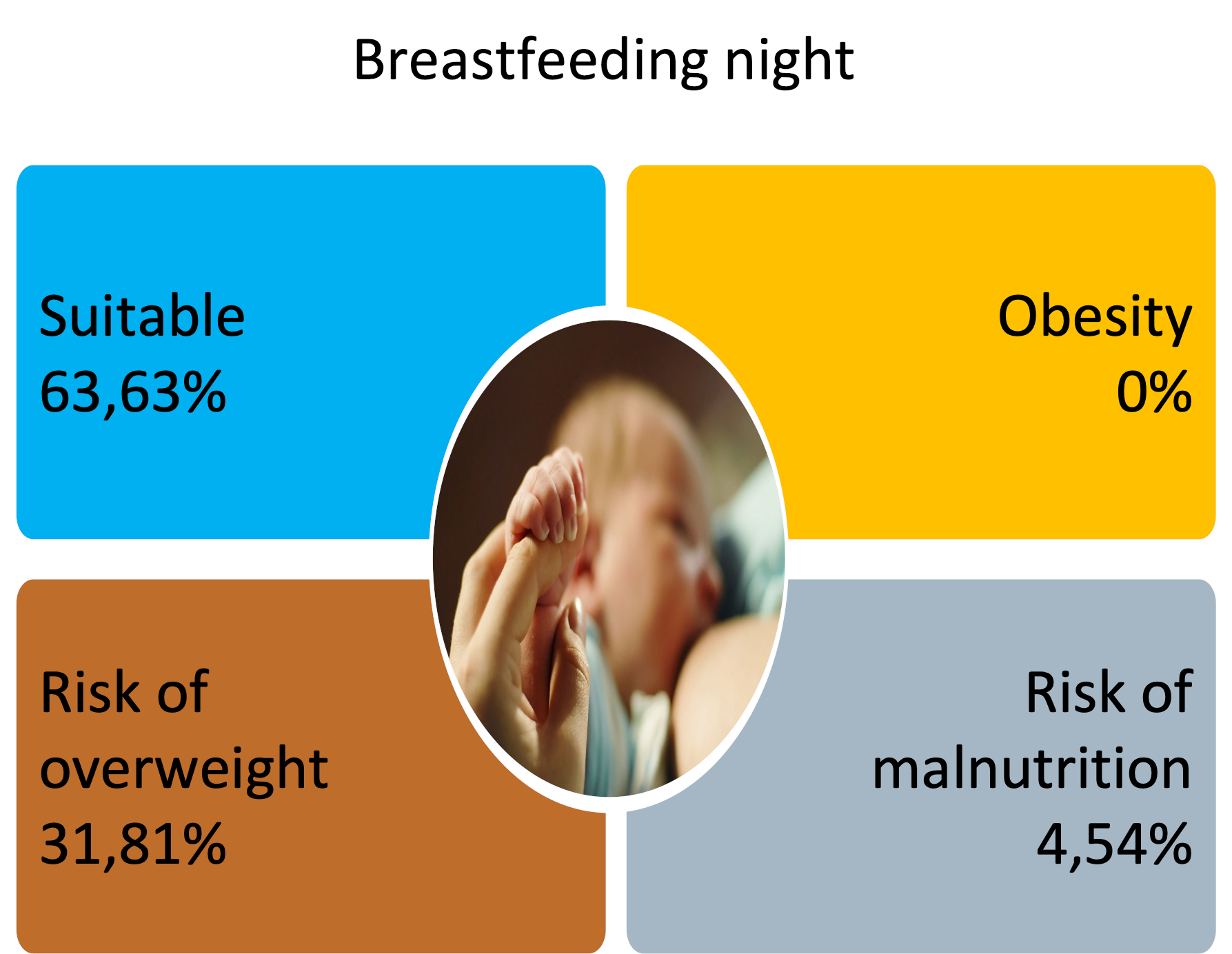

| CLASSIFICATION | Frequency | Percentage |

| SUITABLE | 56 | 63.63% |

| RISK OF MALNUTRITION | 4 | 4.54% |

| RISK OF OVERWEIGHT | 28 | 31.81% |

| Total | 88 | 100.00% |

Conclusions

References

- Folgoso, CC, Martinón-Torres, N., & Martínez, BM (2021). Nutrition during the first 1,000 days of life. Diagnostic and therapeutic protocols in pediatric gastroenterology, hepatology, and nutrition. https://www.aeped.es/sites/default/files/documentos/protocolos_seghnp-aep_2023.pdf#page=445.

- World Health Organization. (2009). Indicators for assessing infant and young child feeding practices: conclusions of the consensus meeting held on 6–8 November 2007 in Washington, DC, USA. In Indicators for assessing infant and young child feeding practices: conclusions of the consensus meeting held on 6–8 November 2007 in Washington, DC, USA. https://pesquisa.bvsalud.org/portal/resource/pt/who-44156.

- American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Nutrition. Feeding the child. In: Kleinman RE, Greer FR, eds. Pediatric Nutrition. 7th ed. Ed Grove Village, IL:American Academy of Pediatrics; 2014: 143.

- Argentine Pediatric Society. Nutrition Committee. Nutritional Guide for Healthy Children from 0 to 2 Years. 2001. https://pediatria.ucoz.es/_ld/0/14_Alimentacion-So.pdf.

- Brahm P, Valdés V. Benefits of breastfeeding and risks of not breastfeeding. Rev chil Pediatr. 2017;88(1):7-14. [CrossRef]

- Rojas M, C. Breastfeeding. In: Leal Quevedo, Ed. The Efficient Pediatrician. 7th ed. 2013.

- Daza W, Dadán S. Complementary feeding in the first year of life. Precop SCP. CCAP, 8; 4: 18-27.

- Feeding from 6 to 24 months. Health information and education: Preventive advice. Child Health Program. AEPap. 2009.

- Chilean Ministry of Health. Nutritional Guidelines for Children Under 2 Years of Age. Nutritional Guidelines for Adolescents. Department of Nutrition and Life Cycle, Division of Disease Prevention and Control. 2005. https://www.enfermeriaaps.com/portal/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/Guide-to-feeding-of-children-under-2-years-Guide-to-feeding-until-adolescent-minsal-chile-2015.pdf.

- Landa R, L., et al. (2012). Co-sleeping promotes breastfeeding and does not increase the risk of sudden infant death: Sleeping with parents. Pediatría Atención Primaria, 14(53), 53-60. https://scielo.isciii.es/pdf/pap/v14n53/revision1.pdf.

- Ball, H.L., Howel, D., Bryant, A., Best, E., Russell, C., & Ward-Platt, M. (2016). Bed-sharing by breastfeeding mothers: who bed-shares and what is the relationship with breastfeeding duration?. Acta paediatrica, 105(6), 628-634. [CrossRef]

- Madar, A.A., Kurniasari, A., Marjerrison, N. et al. Breastfeeding and Sleeping Patterns Among 6–12-Month-Old Infants in Norway. Matern Child Health J 28, 496–505 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Halal, CS, Matijasevich, A., Howe, LD, Santos, IS, Barros, FC, & Nunes, ML (2016). Short sleep duration in the first years of life and obesity/overweight at age 4 years: a birth cohort study. The Journal of pediatrics, 168, 99-103. [CrossRef]

- Olsen, NJ, Rohde, JF, Händel, MN, Stougaard, M., Mortensen, EL, & Heitmann, BL (2018). Joining Parents' Bed at Night and Overweight among 2-to 6-Year-Old Children-Results from the 'Healthy Start'Randomized Intervention. Obesity facts, 11(5),372-380. [CrossRef]

- Seng, C.T., et al. (2016). Predominantly nighttime feeding and weight outcomes in infants. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 104(2), 380-388). [CrossRef]

- Messayke, S., Davisse-Paturet, C., Nicklaus, S., Dufourg, MN, Charles, MA, de Lauzon-Guillain, B., & Plancoulaine, S. (2021). Infant feeding practices and sleep at 1 year of age in the nationwide ELFE cohort. Maternal & child nutrition, 17(1), e13072. [CrossRef]

- Ongprasert, K., Chawachat, J., Kiratipaisarl, W. et al (2025). Breast milk feeding practices and frequencies among complementary-fed children: a cross-sectional study in Northern Thailand. Int Breastfeed J 20, 28. [CrossRef]

- Roy, M., Haszard, JJ, Savage, JS, Yolton, K., et al. (2020). Bedtime, body mass index and obesity risk in preschool-aged children. Pediatric Obesity, 15(9), e12650-e12650. [CrossRef]

- Bedtime in preschool-aged children and risk for adolescent obesity. J Pediatr. 2016;09(176):17–22. [CrossRef]

- O'Shea, KJ, Ferguson, MC, Esposito, L. et al. The impact of reducing the frequency of night feeding on infant BMI. Pediatr Res 91, 254–260 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Gray, MJ, Vazquez, CE & Agnihotri, O. “Struggle at night – He doesn't let me sleep sometimes”: a qualitative analysis of sleeping habits and routines of Hispanic toddlers at risk for obesity. BMC Pediatr 22, 413 (2022). [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).