Submitted:

30 July 2025

Posted:

02 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Subjects

2.2. Research Area

2.3. Questionnaire and Measures

3. Results

3.1. Classification Method of a Family Physician and/or Dentist

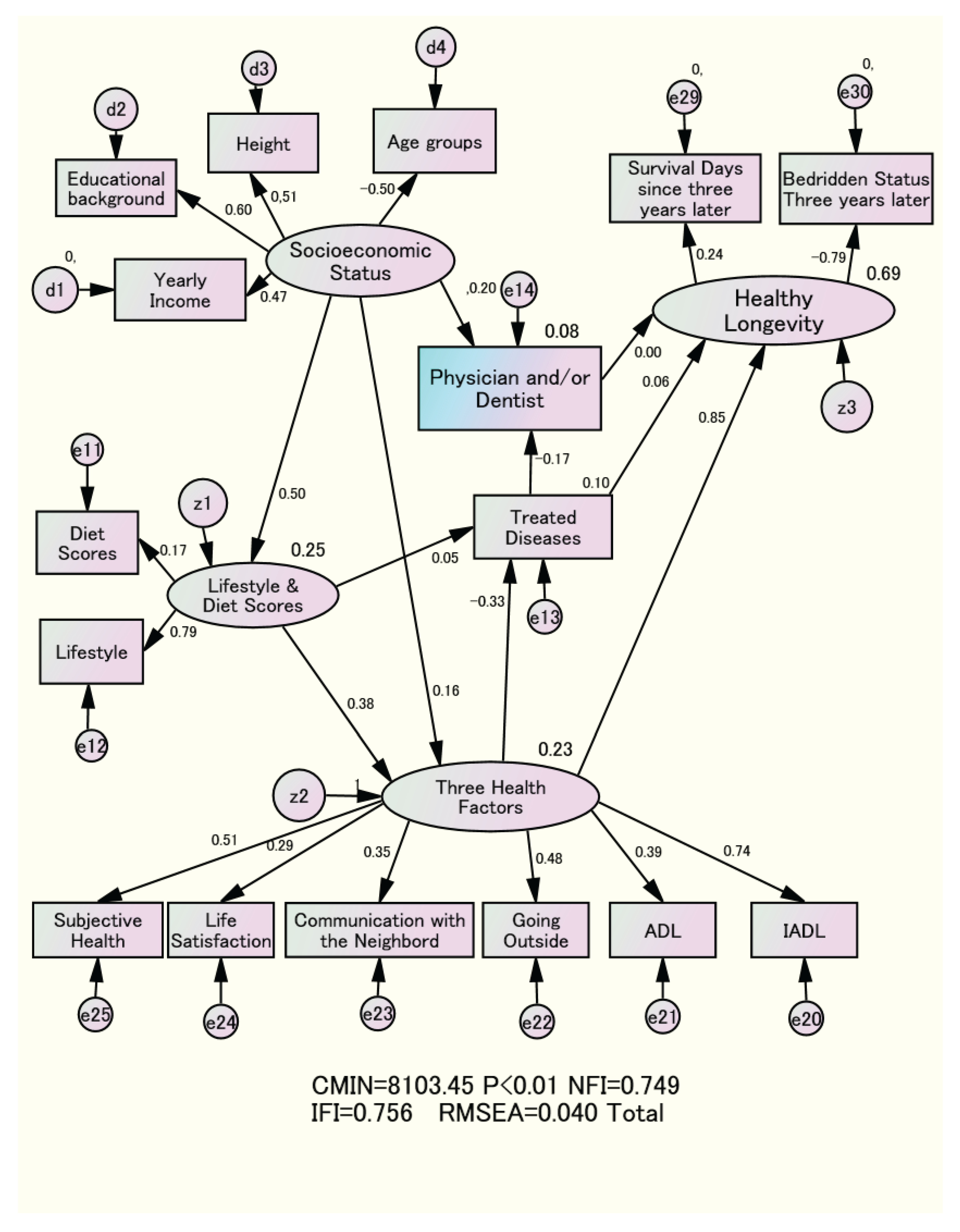

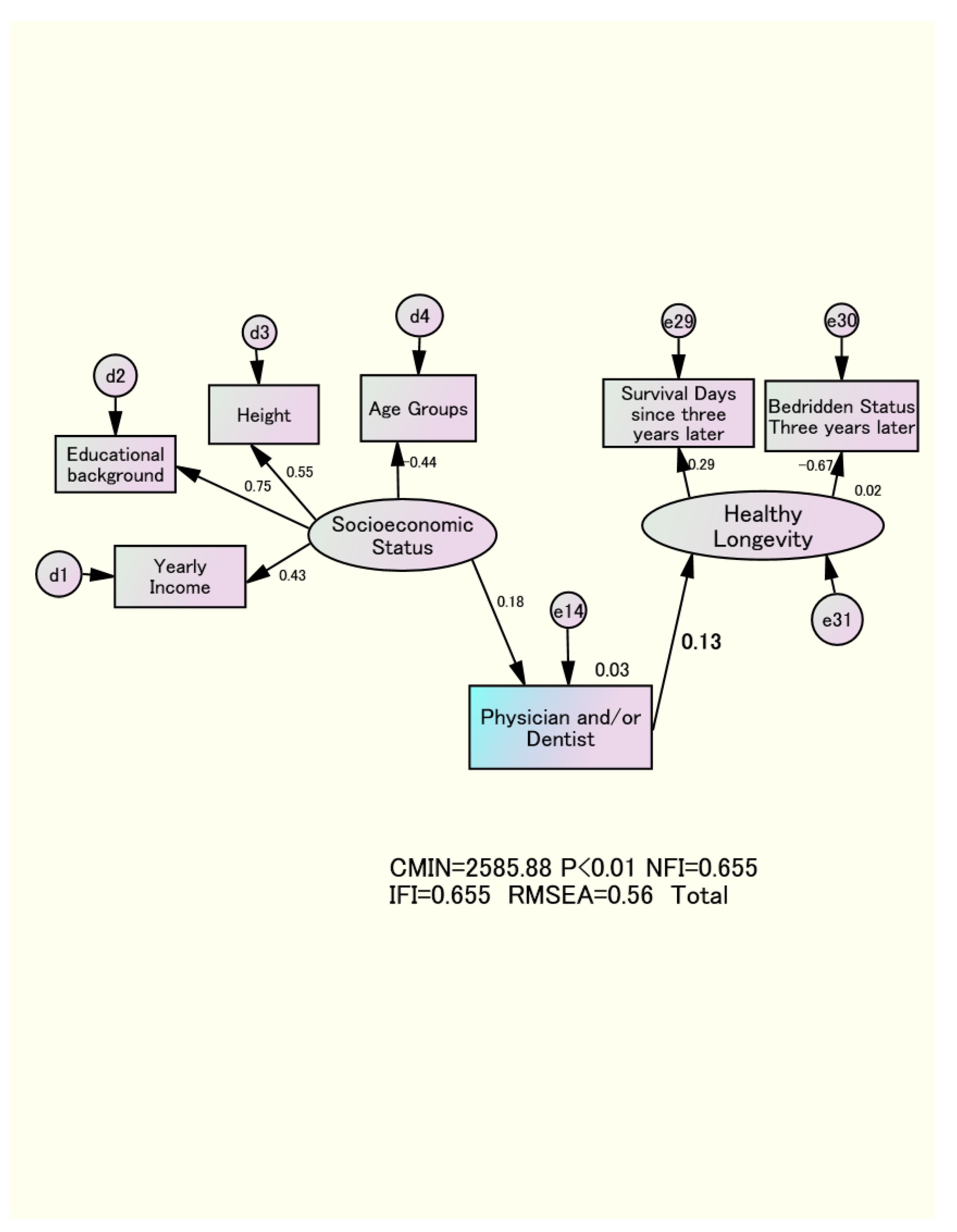

3.2. Causal Structure with Various Factors for Healthy Longevity

4. Discussion

4.1. The Causal Effect of Having Only a Family Dentist and Healthy Longevity

4.2. Importance of the Three Health Factors for the Total Effect on Healthy Longevity

4.3. The Actual Situation of a Physician and/or Dentist

4.4. The Importance of Having a Family Physician and/or Dentist and Research Topics

4.5. Collaboration Between Family Physicians and Dentists

4.6. Future Research Issues

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| QOL | Quality of Life |

| BADLs | Basic activities of daily living |

| IADLs | Instrumental activities of daily living |

| NFI | Normed fit index |

| IFI | Incremental fit index |

| RMSEA | Root mean square error of approximation |

| CPITNN | Community Periodontal Index Treatment Needs |

References

- Labor Statistics Association. Trends in National Hygiene 65 (2018/2019); pp. 82–84. Available online: https://ndlsearch.ndl.go.jp/books/R000000004-I032347714 (accessed on June 16th, 2025).

- Sakurai, N.; Hoshi, T. The aim of Health Japan 21. Hokennokagaku 2003, 45. Available online: https://ndlsearch.ndl.go.jp/books/R000000004-I6665573 (accessed on June 16th, 2025).

- Definition of Family Dentist in Japan. Available online: https://www.jda.or.jp/jda/other/kakaritsuke.html (accessed on June 16th, 2025).

- Definition of Family Physician in Japan. Available online: https://www.med.or.jp/doctor/kakari/ (accessed on June 16th, 2025).

- Scientific evidence of dental health and oral health that contributes to a healthy and long-lived society in 2015. Jpn. Dent. Assoc. 2019. Available online: https://www.jda.or.jp/dentist/program/pdf/world_concgress_2015_evidence_jp.pdf (accessed on June 16th, 2025).

- Fukai, K.; Takiguchi, T.; Ando, Y.; Aoyama, H.; Miyakawa, Y.; Ito, G.; Inoue, M.; Sasaki, H. Mortality rates of community- residing adults with and without dentures. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2008, 8, 152–159. [CrossRef]

- Yoneyama, T.; Yoshida, M.; Matsui, T.; Sasaki, H.; Oral Care Working Group. Oral hygienic care and pneumonia. Lancet 1999, 354, 515. [CrossRef]

- Tano, R.; Hoshi, T.; Takahashi, T.; et al. The Effects of Family Dentists on Survival in the Urban Community-dwelling Elderly. American J. Med. Med. Sci. 2013, 3, 156–165. [CrossRef]

- Berkman; Breslow, L. Health and Ways of Living: The Alameda County Study; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1983. https://openlibrary.org/books/OL3488287M/Health_and_ways_of_living (accessed on June 16th, 2025).

- Kodama, S.; Hoshi, T.; Kurimori, S. Decline in independence after three years and its association with dietary patterns and IADL-related factors in community-dwelling older people: An analysis by age stage and sex. BMC Geriatr. 2021, 21, 385. [CrossRef]

- 1Kaplan, G.A.; Camacho, T. Perceived health and mortality: A nine-year follow-up of the human population laboratory cohort. J. Epidemiol. 1983, 117, 292–304. [CrossRef]

- Laura, C.R.; Longdi, F.; Emmalin, B.; Goel, V. Death and Chronic Disease Risk Associated with Poor Life Satisfaction: A Population-Based Cohort Study. J. Epidemiol. 2019, 18, 323–331. [CrossRef]

- Branch, L.G.; Katz, S.; Kniepmann, K.; Papsidero, J.A. A prospective study of functional status among community elders. Am. J. Public Health 1984, 74, 266–268. [CrossRef]

- Koyano, W.; Shibata, H.; Nakazato, K.; Haga, H.; Suyama, Y. Measurement of competence. Liability and validity of the TMIG Index of Competence. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 1991, 13, 103–116. [CrossRef]

- Berkman, L.F.; Syme, S.L. Social networks, host resistance, and mortality: A nine-year follow-up study of Alameda County residents. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1979, 109, 186–204. [CrossRef]

- Seeman, T.E.; Kaplan, G.A.; Knudsen, L.; Cohen, R.; Guralnik, J. Social network ties and mortality among the elderly in the Alameda County Study. J. Epidemiol. 1987, 126, 714–723. [CrossRef]

- Hoshi T. Causal Structure for the Healthy Longevity Based on the Socioeconomic Status, Healthy Diet and Lifestyle, and Three Health Dimensions, in Japan. Health Promotion. InterOpen. 2024;1-19. [CrossRef]

- Hoshi T. The Causal Structure of the Role of Physicians and Dentists in the Healthy Longevity of Elderly Dwellers Residents. International Journal of Dentistry and Oral Health. 2022. 8(4). [CrossRef]

- Finkel, S.E. Causal Analysis with Panel Data; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA. 1995; pp. 41–56. Available online: https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/book/causal-analysis-panel-data (accessed on June 16th, 2025 ).

- Bentler, P.M.; Dudgeon, P. Covariance structure analysis: Statistical practice, theory, and directions. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 1996, 47, 563–592. [CrossRef]

- Jousilahti, P.; Tuomilehto, J.; Vartiainen, E.; Eriksson, J.; Puska, P. Relation of adult height to cause-specific and total mortality: A prospective follow-up study of 31,199 middle-aged men and women in Finland. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2000, 151, 1112–1120. [CrossRef]

- Hoshi, T.; Nakayama, N.; Takagi, T.; et al. Relationship between height and BMI classification of elderly people living at home in urban suburbs. Jpn. Jour. Health Education and Promotion 2010, 18, 268–277. https://cir.nii.ac.jp/crid/1010000782124139913.

- Hoshi, T. SES. Dietary and lifestyle habits, three health-related dimensions, and healthy survival days. In The Structure of Healthy Life Determinants: Lessons from the Japanese Aging Cohort Studies; Hoshi, T., Kodama, S., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2018; pp. 134–189. Available online: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-981-10-6629-0_8 (accessed on June 16th, 2025 ).

- Ogden, G.R.; Macluskey, M. An overview of the prevention of oral cancer and diagnostic markers of malignant change: 1. Prev. Dent Update 2000, 27, 95–99. [CrossRef]

- Gellrich, N.C.; Suarez-Cunqueiro, M.M.; Bremerich, A.; Schramm, A. Characteristics of oral cancer in a central European population: Defining the dentist’s role. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2003, 134, 307–314. [CrossRef]

- Reichart, P.A. Primary prevention of mouth carcinoma and oral precancerous conditions Article in German. Mund Kiefer Gesichtschir. 2000, 4, 357–364. [CrossRef]

- Takada, Y.; Maeda, Y.; Isada, T. Characteristics of workers for whom oral hygiene education is effective. J. Health Wellness Stat. 2004, 51, 25–29. Available online: https://ndlsearch.ndl.go.jp/books/R000000004-I6885636 (accessed on June 16th, 2025).

- Hoshi, T.; Yabuki, T.; Nagai, H.; et al. Causal structure of the existence of a family dentist and subsequent QOL and maintenance of survival.8020. Hachi-Maru-Nii-Maru 2016, 15, 130–133. Available online: https://ndlsearch.ndl.go.jp/books/R000000004-I027157339 (accessed on June 16th, 2025).

- Wang, Y.; Wan, E.Y.F.; Mak, I.L.; Ho, M.K.; Chin, W.Y.; Yu, E.Y.T.; Lam, C.L.K. The association between trajectories of risk factors and risk of cardiovascular disease or mortality among patients with diabetes or hypertension: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0262885. [CrossRef]

- Yamaza, H.; Takayama, F.; Ogasawara, T.; et al. A Case Report of Dental Treatment for Removing Sources of Oral Infection before Heart Surgery in a Patient with Noonan Syndrome through Medical Examination. Jpn. Soc. Disabil. Oral Health 2020, 41, 318–324. [CrossRef]

| Dentist only | Neither a dentist nor a Physician | Having both a dentist and a Physician | Physician only | Total | ||

| Men | 65-69 | 311 | 232 | 881 | 296 | 1720 |

| 18.1% | 13.5% | 51.2% | 17.2% | 100.0% | ||

| 70-74 | 116 | 77 | 634 | 166 | 993 | |

| 11.7% | 7.8% | 63.8% | 16.7% | 100.0% | ||

| 75-79 | 57 | 39 | 349 | 98 | 543 | |

| 10.5% | 7.2% | 64.3% | 18.0% | 100.0% | ||

| 80-84 | 14 | 23 | 162 | 55 | 254 | |

| 5.5% | 9.1% | 63.8% | 21.7% | 100.0% | ||

| Survival days | 1042.9(114.2) | 1041.1(114.7) | 1027.0(151.7) | 1028.1(145.0) | ||

| Bedridden status | 4( 0.8%) | 15( 4.0%) | 111( 5.5%) | 48( 7.8%) | ||

| Non of the bedridden status | 494(99.2%) | 356(96.0%) | 1,915(94.5%) | 567(92.2%) | ||

| Women | 65-69 | 270 | 124 | 1022 | 230 | 1646 |

| 16.4% | 7.5% | 62.1% | 14.0% | 100.0% | ||

| 70-74 | 98 | 54 | 700 | 157 | 1009 | |

| 9.7% | 5.4% | 69.4% | 15.6% | 100.0% | ||

| 75-79 | 44 | 45 | 485 | 147 | 721 | |

| 6.1% | 6.2% | 67.3% | 20.4% | 100.0% | ||

| 80-84 | 11 | 18 | 217 | 92 | 338 | |

| 3.2% | 5.3% | 64.0% | 27.2% | 100.0% | ||

| Survival days | 1054.7(83.9) | 1042.8(117.9) | 1048.2(104.3) | 1036.7(129.2) | ||

| Bedridden status | 9(2.1%) | 18( 7.5%) | 19( 7.8%) | 8(12.8%) | ||

| None of the bedridden status | 414(97.9%) | 223(92.5%) | 2234(92.2%) | 546(87.2%) | ||

| ( ): Standard Deviation | ||||||

| Men | Women | |||||

| Physician only | Dentist only | Physician only | Dentist only | |||

| Educational Background | ||||||

| Graduated from high school | 322(57.6%) | 224(47.9%) | 469(84.8%) | 273(72.4%) | ||

| Graduated from vocational school | 32( 5.7%) | 19( 4.1%) | P<0.01 | 63(11.4%) | 58(15.4%) | P<0.01 |

| Graduated from college | 205(36.7%) | 225(48.1%) | 21( 3.8%) | 46( 12.2%) | ||

| Yealy Income | ||||||

| <1million yen | 10( 1.8%) | 7( 1.5%) | 74(13.9%) | 28( 7.7%) | ||

| 1milion-3 million yen | 235(41.5%) | 128(27.8%) | 284(53.4%) | 146(40.0%) | ||

| 3 million-7 million yen | 268(47.3%) | 260(56.5%) | P<0.01 | 153(28.8%) | 157(43.0%) | P<0.01 |

| >7million yen | 53( 9.4%) | 65( 4.1%) | 21( 3.9%) | 34( 9.3%) | ||

| Height(cm) | 163.2(6.1) | 164.5(7.0) | P<0.01 | 150.2(7.2) | 152.0(4.9) | P<0.01 |

| Age | 71.5(5.1) | 69.5(4.1) | P<0.01 | 72.7(5.4) | 69.1(4.1) | P<0.01 |

| Subjective Health | ||||||

| very healthy | 63(10.2%) | 146(29.4%) | 50( 8.0%) | 250(27.2%) | ||

| almost healthy | 409(66.5%) | 317(63.8%) | P<0.01 | 390(62.3%) | 605(65.8%) | P<0.01 |

| not so healthy | 97(15.8%) | 27( 5.4%) | 129(20.6%) | 47( 5.1%) | ||

| Unhealthy | 46( 7.5%) | 7( 1.4%) | 57( 9.1%) | 18( 2.0%) | ||

| Life Satisfaction | ||||||

| very satisfied | 367(51.5%) | 490(45.1%) | 368(60.9%) | 93(70.6%) | ||

| moderately satisfied | 142(57.0%) | 107(43.0%) | P<0.01 | 179(29.6%) | 99(23.9%) | P<0.01 |

| Unsatisfied | 188(70.4%) | 37(29.6%) | 57( 9.4%) | 23( 5.5%) | ||

| Communication with the Neighborhood | ||||||

| Seldom | 234(39.6%) | 138(28.6%) | 180(30.2%) | 79(19.8%) | ||

| Once a month | 147(24.9%) | 135(28.0%) | P<0.03 | 110(18.4%) | 101(25.4%) | P<0.03 |

| 3 to 4 times a week | 147(24.9%) | 145(30.0%) | 218(36.5%) | 149(37.4%) | ||

| almost every day | 63(10.7%) | 65( 13.5%) | 89(14.9%) | 69(17.3%) | ||

| Going Outside | ||||||

| less than once a month | 40( 6.7%) | 12( 2.4%) | 45( 7.6%) | 7( 1.7%) | ||

| more than once a month | 46( 7.8%) | 31( 6.3%) | P<0.01 | 58( 9.8%) | 25( 6.1%) | P<0.01 |

| 3 to 4 times a week | 507(85.5%) | 447(91.2%) | 490(82.6%) | 377(92.2%) | ||

| Total Number of Treated Diseases | 0.92(0.82) | 0.17(0.48) | P<0.01 | 0.73(0.77) | 0.07(0.28) | P<0.01 |

| Basic Activities of Daily Living | 2.89(0.43) | 2.92(0.27) | P<0.12 | 2.87(0.41) | 2.89(0.32) | P<0.46 |

| Instrumental Activities of Daily Living | 4.59(1.05) | 4.83(0.50) | P<0.01 | 4.51(1.17) | 4.92(1.41) | P<0.01 |

| Lifestyle Scores | 2.75(1.20) | 3.04(1.11) | P<0.01 | 2.73(1.02) | 2.96(0.99) | P<0.01 |

| Diet Scores | 3.53(2.27) | 3.84(2.30) | P<0.01 | 4.13(2.18) | 4.57(2.25) | P<0.01 |

| ()means Standard Deviation | ||||||

| Physical Health | Mental & Social Health | Socioeconomic Status | Factor 4 | |

| IADL | 0.722 | 0.258 | 0.037 | -0.124 |

| Bedridden Status | -0.619 | -0.178 | -0.036 | 0.100 |

| BADL | 0.484 | 0.048 | 0.045 | -0.007 |

| Life Satisfaction | 0.043 | 0.524 | 0.062 | -0.075 |

| Subjective Health | 0.210 | 0.500 | 0.123 | -0.349 |

| Communication with the Neighborhood | 0.083 | 0.455 | -0.060 | 0.007 |

| Going Outside | 0.323 | 0.328 | 0.083 | -0.026 |

| Lifestyle | 0.164 | 0.304 | 0.138 | -0.002 |

| Diet Scores | 0.058 | 0.180 | -0.031 | -0.034 |

| Educational Background | 0.057 | -0.021 | 0.648 | -0.087 |

| Height(cm) | 0.058 | -0.088 | 0.592 | -0.034 |

| Yealy Income | 0.022 | 0.197 | 0.434 | -0.027 |

| Treated Diseases | -0.061 | -0.111 | 0.022 | 0.654 |

| Family physician and/or Dentist | -0.045 | -0.025 | -0.102 | 0.426 |

| Men | Women | Total | ||

| “Socioeconomic Status”⇒「Physician and/or Dentist」 | 0.20 | 0.22 | 0.19 | |

| “Socioeconomic Status”⇒“Lifestyle and Diet Scores” | 0.20 | 0.22 | 0.19 | |

| Standardized | “Socioeconomic Status”⇒“Three Health Factors” | 0.52 | 0.64 | 0.47 |

| Direct Effect | “Lifestyle and Diet Score”⇒「Treated Diseases」 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| “Lifestyle and Diet Score”⇒“Three Health Factors” | 0.51 | 0.53 | 0.35 | |

| “Three Health Factors”⇒“Healthy Longevity” | 0.80 | 0.89 | 0.82 | |

| 「Physician and or Dentist」⇒Three Health Factors” | 0.06 | 0.21 | 0.14 | |

| “Three Health Factors”⇒「Treated Diseases」 | -0.40 | -0.36 | -0.36 | |

| 「Treated Diseases」⇒「Physician and/or Dentist」 | -0.16 | -0.07 | -0.13 | |

| 「Treated Diseases」⇒“Healthy Longevity” | -0.16 | -0.07 | -0.13 | |

| “Socioeconomic Status”⇒⇒“Three Health Factors” | 0.28 | 0.32 | 0.30 | |

| “Socioeconomic Status”⇒⇒「Treated Diseases」 | -0.11 | -0.12 | -0.11 | |

| “Lifestyle and Diet scores”⇒⇒「Treated Diseases」 | -0.20 | -0.19 | -0.19 | |

| Standardized | “Socioeconomic Status”⇒⇒「Physician and/or Dentist」 | 0.22 | 0.22 | 0.22 |

| Total Effect | “Three Health Factors”⇒⇒「Physician and/or Dentist」 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.05 |

| “Lifestyle and Diet scores”⇒⇒「Physician and/or Dentist」 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.02 | |

| “Socioeconomic Status”⇒⇒“Healthy Longevity” | 0.24 | 0.31 | 0.27 | |

| “Lifestyle and Diet scores”⇒⇒“Healthy Longevity” | 0.43 | 0.50 | 0.45 | |

| “Three Health Factors”⇒⇒“Healthy Longevity” | 0.80 | 0.89 | 0.83 | |

| ⇒means direct effect ⇒⇒means total effect | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).