1. Introduction

The mining industry is one of the biggest waste producers among human activities, most of it being left forever as huge legacy disposal sites. The evolution of ore grades and recovery technology leads to continuously increasing waste to commodity ratios, and to ever larger waste management facilities. There is no option to reduce the volume of generation by process improvement, contrary to many industries. The only possible mitigation scheme is to find secondary uses to new and historic mine waste. Such secondary uses are a step for the mining industry to integrate the circular economy thinking, and to reduce its needs for hazardous landfill areas and its global footprint.

Matching a given waste characteristics and the requirements of an end user industry (civil engineering, construction, minerals industries,…) is usually a tough challenge, based on compromises on the specifications, acceptable volumes, distance between mine and user, and time. Characteristics and specifications are poorly known, and this does not allow the emergence of resource platforms between producers and users.

Mining waste is usually classified according to its origin in the mining process:

Waste rock, which comprises barren rock which has to be excavated to gain access to ore (overburden), and undergrade ore (parts of an orebody which cannot be processed economically at the time of mining). Most of it is coarse to massive, stored as dumps,

Tailings, or mining residues, which are the waste fraction after ore processing. They are milled down to the same fine grain as valorisable ore, and therefore stored behind dams or other containment facilities. They may be used to backfill mining cavities. They contain large volumes of minerals in sand or mud forms, undergrade concentrations of the mined commodity, and increased concentrations of other elements including undesirable ones,

Metallurgy waste, such as slag, at sites where the mined commodity is further refined.

We propose here to develop a classification based on the possible uses for a given waste, taking into account the constraints of each possible user industry, in order to promote reuse according to Circular principles, and to reduce as much as possible the volume of legacy disposal sites. We included the mining industry itself among the end users, to take into account remining of legacy waste for new or previous commodities. We did not include small volume uses, in order to stay in a waste reduction perspective.

1.1. Reference to Circular Principles

Circular economy is a framework for an array of critical changes in the global economy trends, aimed at reducing its pressure on the Earth’s resources, on the environment and on the climate [

1,

2,

3]. Its relationships with sustainability were recently discussed [

4]. The most prominent of these changes is a systematic increase of recycling, reducing together the need in primary resources and the waste generation. Both are critical for the mining sector, which is living on resources extraction and has to manage waste as one of its biggest costs – and burdens [

5].

Early works [

6,

7] connected the recycling loop with the concept of sustainability, in which no human activity should exceed the ability of the Earth to support it. Unsustainable activities are bound to be short-lived, when meeting their system boundaries: resource exhaustion, energy or land shortage, or permanent damage to the environment. Mining, according to 20

th century practice, was unsustainable as it extracted faster and faster finite resources, with fast increasing energy and land needs, and generating fast increasing waste piles.

Circular economy principles are already applied to metals: “ Recovery and reuse of metals from products is on the increase for some metals. For example, 75 per cent of all aluminium ever produced is still in use” [

8]. Case studies on recent developments in this field were summarised by ICMM [

9].

1.2. The Size of the Problem

Mining waste is the biggest waste flow generated by mankind – up to at least 65,000 Mt/year [

10] - and due to its inalterability, it accumulates without any significant reduction. The main source of existing waste reduction is weathering and erosion, which means actually disposal in the surface water network (

Figure 1) and on the sea bottom [

11]. It is therefore highly desirable to find uses for mining waste in the world needs in minerals.

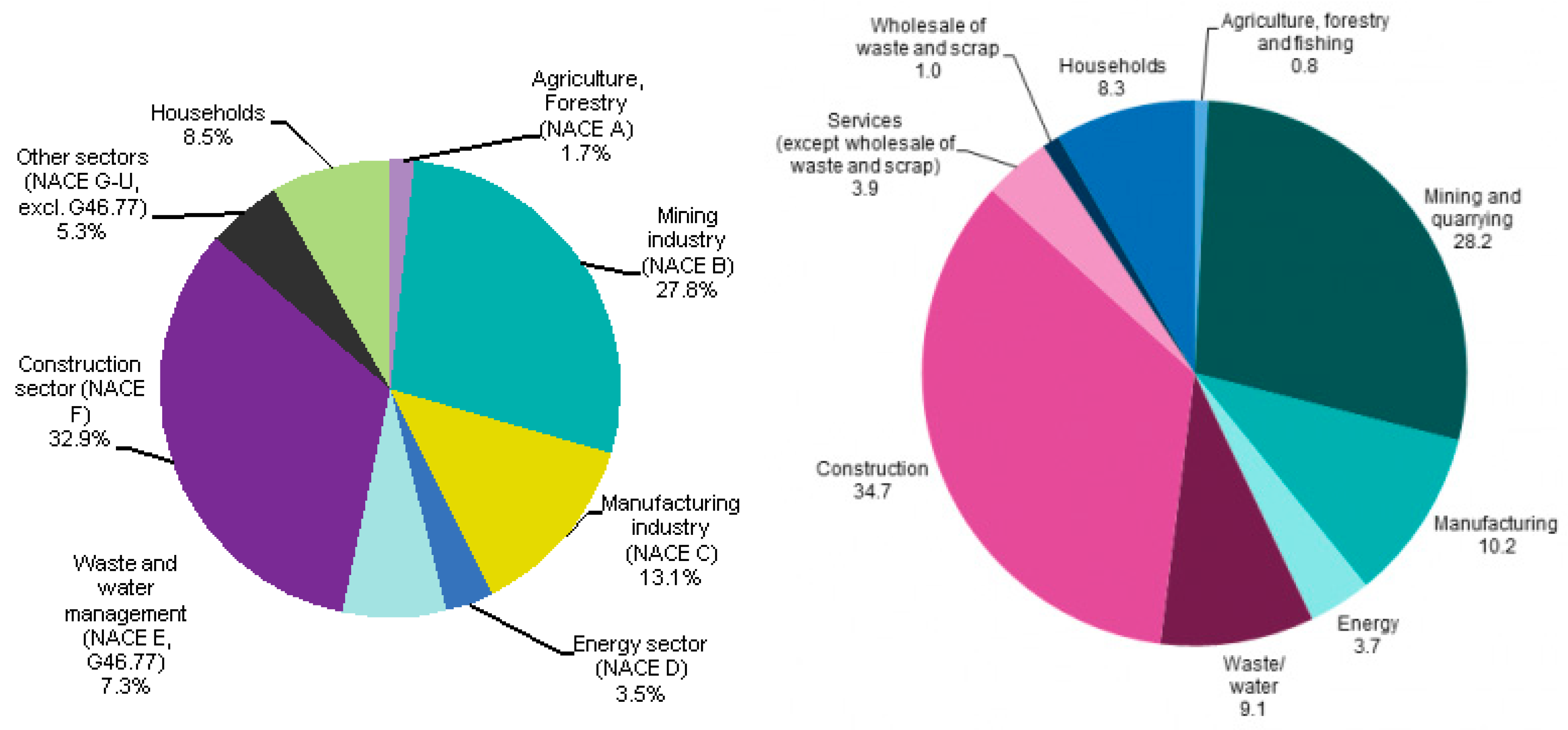

An example of the size of mining waste among other waste flows can be deduced for Europe using Eurostat statistics (

Figure 2, [

12]). This can be extrapolated to large mining countries (Australia, Canada, China, USA, South Africa…) using their own statistics, or their total mining commodities production as a scaling factor. In most developing countries, mining waste has an even larger part of the total waste, due to less developed secondary industries and consumer markets. Mining technology being almost the same everywhere, the use of ore production statistics to estimate mining waste is justified [

13].

1.3. Waste Rates of Modern Mining

Since the beginning of mining statistics, a continuous decreasing trend is observed in minable grades for most commodities [

14]. This is first due to mining economics: small high grade deposits indeed became exhausted, but, more important, were unable to cope with the ever increasing demand. This is also due to the continuous improvement of beneficiation technology, which allowed the profitable recovery from ever lower grade ores [

15]. This is exemplified by West [

16]: The

“massive decrease in copper ore grades was not driven by depletion of higher grade deposits with resulting higher copper prices. It was instead a direct result of innovation that converted massive supplies of previously worthless “waste” rock into valuable ore”. This tendency implies that the waste rate increases in ore beneficiation. A decrease by 10% of the cutoff grade will, for a constant commodity production, result in a 11 to 12% increase of the waste produced.

Energy concerns played also a role in this general trend [

15,

17]. The higher energy needs of lower grade ores [

15] are hidden by the preferential availability of cheap energy and water offered by mining countries as an infrastructure support to mining development. This driver may fade away in the future with climate change mitigation actions (most of mining energy is provided by fossil fuels) and is expected to be the first cause of commodities rarefaction [

15], even more than orebodies depletion.

Furthermore, mining operations mechanisation allows mining deeper orebodies, with larger waste rock amounts. The move from underground mining to open pit extraction increased also massively the amount of waste rock to be managed, and often disposed of. More generally, the constant trend to lower grades leads to higher waste amounts for a given quantity of commodity.

Reprocessing existing waste to recover further the commodity will have positive impacts on extracted volumes or energy needs, but it will not significantly affect the volume of residual waste, except where cut-off grades are extremely high (Al, Fe, coal). The main benefit of reprocessing, in waste reduction terms, is to reduce the need for new extraction, and subsequent waste generation.

2. Profitable Uses of Mine Waste in Modern/Circular Economy

Two main types of profitable uses of mine waste can be identified within a waste reduction and circular economy perspective:

Profitable use by the mining sector itself, for its own needs and benefit. We describe it hereunder as Further recovery of commodities or Remining. It is most often led by a new company, different from the mining company which produced and stored the waste. This activity belongs to the Circular Economy because it reduces the needs in extraction of primary resources, and it often reduces the volume of residual waste,

Use by the mining sector itself, for its own needs and benefit in site rehabilitation and/or mine closure. Mine waste with desirable features such as acid neutralisation potential belongs also to the Circular Economy because it reduces the needs in extraction of primary resources,

Secondary use of mining waste as a raw material, in another economic sector than mining. In this case, the activity belongs to the Circular Economy because it reduces the needs in extraction of primary minerals, and it always reduces the volume of residual waste.

The former will be described here to allow comparisons with non-mining uses, but the latter will be the main focus of the present paper, as waste reduction is its direct purpose and it offers significant contributions to sustainability Safeguard Standards 1 (Biodiversity, Ecosystems and Sustainable Natural Resource Management), 2 (Climate Change and Disaster Risks), 3 (Pollution Prevention and Resource Efficiency) and 4 (Community Health, Safety and Security) [

18]. Reference to sustainability is also explicated by [

19].

Cotrina-Teatino and Marquina-Araujo [

20] emphasised the link between circular economy strategies for tailings and waste management in mining, and sustainability and optimised resource use in the mining industry, calling for more innovation in mining waste beneficial use.

An in-depth study [

21] identified five key drivers for mine waste valorisation in a circular economy perspective : 1/Social dimensions, 2/Geoenvironmental aspects, 3/Geometallurgy specifications, 4/Economic drivers and legal implications, and 5/Circular economy aspirations. The objective of the present paper being developing a mine waste classification based on circular economy abilities, we focused on 3, 4 and 5, as social and geoenvironmental issues are chiefly site-specific, while we look for material characteristics.

2.1. Further Recovery of Commodities

2.1.1. Remining

Remining available waste has been an active practice for centuries (see for instance [

22]). Recovery of valuable resources from mining waste applies mainly to existing waste from past activities, as the business model of current activities implies that all what is economically recoverable will be included in the beneficiation chain. However, undergrade ore can still be considered as waste, though the current practice is to store it apart in the hope of better commodity prices [

23].

Recoverable commodities from existing waste include:

previously undergrade ore which becomes amenable to beneficiation due to better commodity prices or to improved technology. In this case, the ore can be classified under the same commodity as for previous mining at the site. At still active mines, blending waste and primary new ore can be applied to streamline process feed,

commodities which were not beneficiated at the time of previous mining, either because of a lack of interest for them, or because no economic beneficiation technique was then available. This is often the case for critical metals, currently required by new technologies (for instance B, Be, Li, Ga, Ge, Ni, Co, V, Sr, In, Hf, Ta, W, Nb, Y, rare earths, Cd, Sb, Ba, Bi and PGEs). It is possible to process again this waste, which will be classified under the new commodity. For instance, copper waste containing residual cobalt [

24,

25] may be classified under “recoverable cobalt”,

non-metallic commodities (usually industrial minerals) that may be recovered from existing waste on the opportunity of site closure or remediation work. The largest such commodities are aggregate, for waste rock [

26] and sand, for tailings [

27].

This approach to recovery can be applied for exploration, as an alternative to new deposits discovery, for the evaluation of strategic resources at a country level [

28] or as a way to fund site remediation [

29,

30].

2.1.2. Tailings and Process Waste

Reprocessing of existing tailings for commodities saves on cost, energy and water, compared to primary resource extraction, both for crushing and milling and for extraction. Further milling of coarser tailings may be needed but at a fraction of the cost. Extraction of tailings from their storage facility (TSF) is also much cheaper than open cast or underground mining. Last but not least, reprocessing an older TSF and rebuilding a new one allows the improvement of its stability and environmental impacts, saving on otherwise required site management costs. The world tailings stock was estimated to be 217 billion m

3 stored in 8500 facilities [

31], with an annual growth of 11.1 billion m

3, and 223Gt (534 billion m

3) from 29,000–35,000 facilities, with an annual growth of 8 to 10Gt [

32].

Many examples are available, both from research [

31,

33,

34,

35] or from full-size operations [

36,

37,

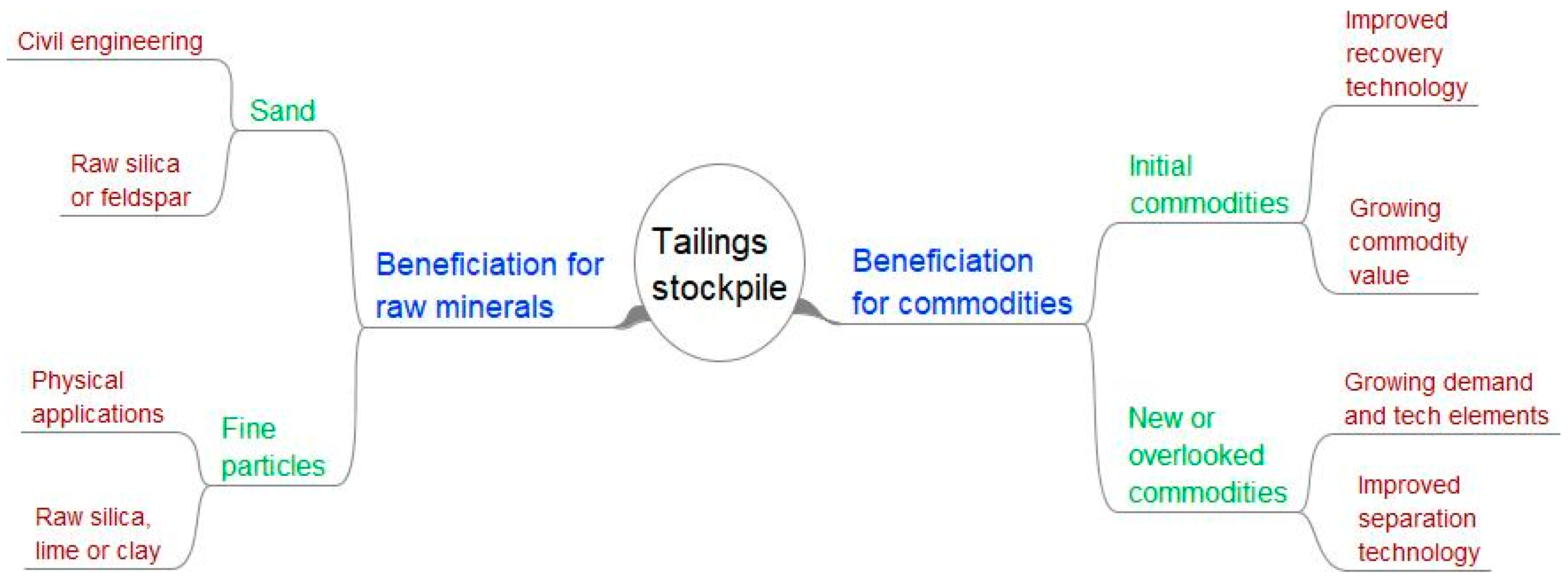

38], covering both the original commodities and new elements of interest, including critical elements (

Figure 3). Hydraulic mining is the most frequently used technology [

39].

2.1.3. Waste Rock and Undergrade Ore

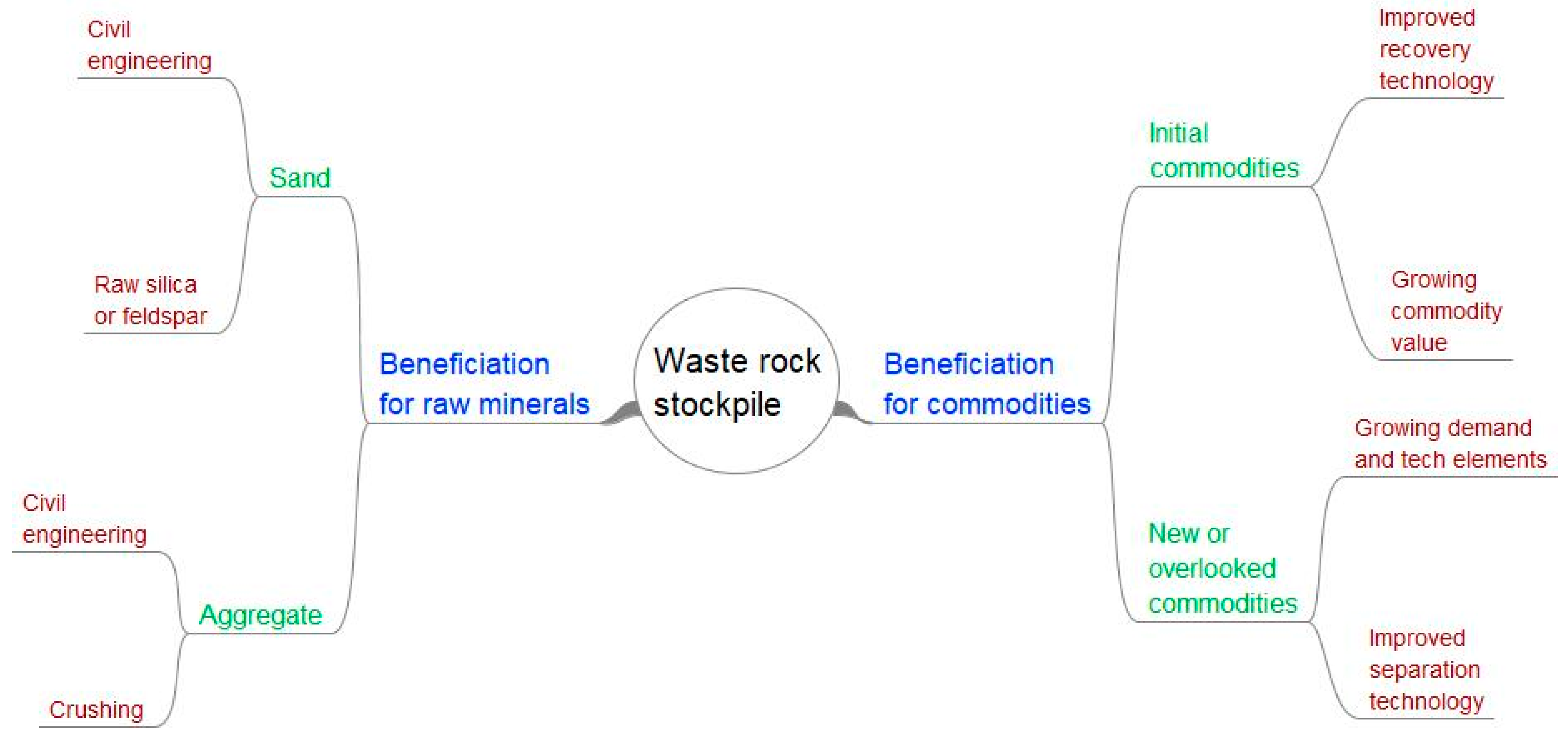

Reprocessing of existing waste rock heaps for commodities is possible for low-grade ores, disposed of as undergrade at the time of initial mining (

Figure 4). It saves on cost and energy, compared to primary resource extraction by open cast or underground mining. Though waste rock heaps are usually less of a concern than TSFs, reprocessing an older waste rock heap may allow also the improvement of its stability and reduce environmental impacts.

2.1.4. Slag

Using slag or other metallurgical waste is considered less often than tailings or waste rock for further beneficiation for commodities, as is extraction and mechanical processing is usually more complex and energy-intensive. The most commonly used technologies are pyrometallurgical processes (re-smelting the slag to separate metals, common in copper recovery using an electric furnace or a slag cleaning reactor), hydrometallurgical processes (acid or alkaline leaching, followed by electrowinning or precipitation, especially used for zinc, lead or nickel recovery) and bioleaching (use of microorganisms to extract metals).

Recovery from slag is described for copper [

36,

40] and for zinc and lead [

41]. These processes include the recovery of precious and critical elements such as Se, Te, Sb or Bi [

40].

2.2. Waste as a Raw Material

2.2.1. Tailings and Process Waste

Tailings and other fine-grained process waste are minerals ranging from sand to clay by their physical properties, and may be used as such (

Figure 3) when their chemical properties do not preclude this use. Most tailings are deposited by gravity from slurries in tailing dams, otherwise designated as TSFs (tailings storage facilities), but a significant proportion is used by the miners as backfill material and can be considered as engineering resources rather than waste.

The easy handling and large available volumes are assets for backfill, landscaping material, sand in civil engineering and road construction, as long as their sulphide, salts or metals contents are not excessive. Cement and concrete applications are possible [

42], as well as artificial soil applications. More specific applications such as coatings, resin, glass and glazes, bricks, floor tiles and cement, soil amender or water treatment may be considered for clayey tailings or red mud from aluminium refineries. Reactive waste can be used as a chemical agent for other mineral industries (i.e. as a source of acids).

2.2.2. Overburden Waste Rock

Waste rock is similar in many aspects to primary rocks quarried for aggregate applications, but also for backfill, landscaping material, aggregate in construction and civil engineering, and for source material for cement and concrete (

Figure 4; [

42]). Waste rock with acid neutralising properties [

43] are valuable raw mineral resources for mine closure and acid drainage mitigation.

2.2.3. Under Grade Ore

Though under grade ore is rather used for reprocessing to extract minerals and metals, it may be used as aggregate as long as its chemical and physical stability do not constitute a significant hazard. The main issue is the contents in acid-generating oxidisable sulphides or in soluble salts.

2.2.4. Slag and Other Metallurgy Waste

Slag is also used for road construction and in concrete, due to its toughness, and in cement for its chemical properties. They can be used as a replacement for Portland cement up to 70%, improving long-term strength, permeability and durability [

44].

3. Mining Waste Classification

There are a number of classification schemes for mining waste, each of them according to a specific purpose. We will review them in order to establish how far they can be used to evaluate circular economy opportunities.

3.1. According to Mining Activity and Storage Facility

The main waste categories are extraction waste (more often named waste rock) and processing waste, with markedly different properties, and subsequently of waste forms [

45]. Their key properties are summarised in

Table 1.

Extraction waste can be further subdivided in overburden, barren host rocks, and low grade mineralised rocks. Most are stored as waste heaps, or dumps, or spoils, usually above the original ground level, which makes further access easier than excavation mining, but in some cases they can be dumped in mining excavations or along slopes.

Milled ore is usually directly processed and

processing waste is mostly referred to as

tailings. This is the most familiar category of mining waste. It is usually extremely fine grained, but on older mine sites, coarser waste from mechanical beneficiation processes can be found. It is stored as reservoirs limited by dams in which it is transferred in fluid or semi-fluid form (slurry) for natural decantation and dehydration (

Figure 5), usually named tailing dams, Tailings Storage Facilities or TSFs.

They can be built in available valleys, similarly to hydropower reservoirs, or by elevation above the natural ground, in flat areas. After complete decantation and dehydration, the result is a compact fine-grained sedimented structure, which can be later dug for commodity recovery with minimal comminution [

11,

13,

33]. The construction and management of TSFs is strictly regulated and subject to risk assessment [

46,

47,

48,

49].

When metal recovery is performed at the mine site, metallurgy waste (slag) can be found, mostly as stockpiles as it is usually granular. A specific category of metallurgy waste, red muds from alumina processing, is similar to tailings.

3.2. Classification by Ore Grade in Waste Rock

During mining (both underground or in open-pits), various categories of rock are extracted. Rocks without any ore content may need to be removed to expose ore or to access it: this is usually referred to as overburden, but may be called also steriles. At the moment they are extracted, the miners know they are barren. They do not direct them to crushing but to waste rock stockpiles.

Orebody sections which are known to be significantly lower than cutoff grade may be also directed to waste rock stockpiles, if the miners do not expect them to be profitably beneficiated even with better market conditions. However, it may be desirable to manage them separately if they have AMD potential, or other properties that can make them unsuitable for reuse. They are managed as mineralised waste rock or undergrade ore stockpiles.

Orebody sections which are known to be lower than cutoff grade, but may become minable under better market conditions, will be directed to low grade ore stockpiles, waiting hopefully for future beneficiation. If never used, they have to be manage separately if they have AMD potential, or other properties that can make them unsuitable for safe disposal. They are managed as undergrade ore stockpiles.

Orebody sections around or above cutoff grade are usually stored for blending and directed to crushing. In some configurations, crushed ore may be stockpiled rather than directly milled and may have to be managed as undergrade ore when the mine closes.

3.3. Classification by Ore Grade in Tailings

By definition, tailings fit totally the waste definition, a substance discarded after primary use, as worthless. Tailings are ore which underwent the full beneficiation process, and for which no economic valorisation option is available at the time of disposal. Beneficiation options may arise later, as a result of newly available technologies, or of a rise in commodities market value. Reprocessing legacy tailings is then a desirable option, as the cost and energy needs of milling will be much lower than for primary ore. When considering the new market conditions and technologies, tailings which have still no possible economic valorisation for commodities are raw fine grained minerals.

3.4. Grain Size and Beneficial Use Options

One key separation between potential beneficial uses is between coarse grained material, used as a substitute for aggregate, and fine grained material, used as a substitute for sand, or as bulk minerals.

3.4.1. Coarse Grained Material

Waste rock and other coarse material will be evaluated for potential reuse according to the criteria applicable to aggregate. This includes bulk aggregate used for infrastructures by civil engineering, and aggregate used in construction, especially by the concrete industry [

50]. Physical criteria defining the fitness for purpose are the following [

26,

46,

51],

Table 2:

According to civil engineering properties, it is often admitted that coarser waste rock provides better strength (the coarser the better), especially for angular blocks, while for concrete applications, a blend of various grain sizes may be designed for the planned use. This implies that a good knowledge of the grain size of waste rock is needed for beneficial use, especially as it was not homogeneous in the waste feed, and it tended to evolve with storage time, the finer fragments moving towards the bottom of the form between the larger blocks. Other criteria defining the fitness for purpose, such as matrix chemistry and stability, will be listed further on.

3.4.2. Tailings

Grain size of tailings therefore range from sand to clay, with a large proportion of silt-size material. Sand size tailings can be used in civil engineering or in concrete production if their chemical composition does not preclude this use [

52]. They tend to have more homogeneous grain sizes than primary extraction sand. Silt and clay size tailings are suitable for bulk mineral uses, such as cement or glass, subject to the same chemical limitation, or for non-structural engineering (landscaping, for instance). In this case, their grain size has little effect on their suitability for beneficial use. Due to the evolution of ore processing technology, older tailings are coarser, especially from gravity processes, while chemical processes require finer grain material for better exchange surfaces.

3.4.3. According to Matrix Chemistry and Mineralogy

Rock matrix chemistry and mineralogy are determined by the geology of the ore and gangue, and the orebody genetic type. They will define chemical groups with potentially different characteristics for beneficial use and possible applications. Some examples are listed in

Table 3

The matrix chemistry (

Table 3) determines the possible use as a raw material component (cement, glass, bricks), part of the physical properties and the stability (concrete).

3.5. According to Chemical Stability

Leaching tests (

Table 4) are at the core of this classification. Potential undesirable properties are solubility (salts), reactivity (alkali reaction in concrete) and release of potentially harmful elements (metals or metalloids) during weathering of the secondary use products. The key issue about chemical stability is acid mine drainage (AMD) or acid rock drainage (ARD, which can happen outside mining areas). For a full review of ARD issues and prediction, see [

43].

3.5.1. Waste Rock

If they do not contain undesirable substances or sulphide, such rocks can be directly reused as aggregate or for civil engineering. If they have acid neutralisation potential, they may be stored separately for future site remediation and AMD mitigation. Testing waste rock for potential release of contaminants is generally based on the quantification of undesirable elements in water or other solutions exposed to waste according to a standardised protocol [

53,

54,

55]. The large size of waste rock fragments, and the subsequently low interaction surface, are a challenge for such tests: the release potential may be underestimated if large blocks are tested, especially as block fragmentation is likely to occur on the long term, beyond test duration; and if blocks are fragmented for the test, the test result will not reflect the real waste rock behaviour.

3.5.2. Crushed Rock and Low Grade Ore

Testing for chemical stability and potential leaching is more critical for lower grain size material, which is expected to be more prone to oxidation and leaching. Due to its potential applications, acid generation and subsequent metals and metalloid leaching are the most critical issues for beneficial uses. Chemical reactivity is also an issue, especially for uses in concrete. Applications in mine backfill are less critical as such waste does not differ much from the host rocks, apart from its fragmentation and permeability to water and oxygen.

3.5.3. Tailings

When used for backfill or civil engineering, tailings are less permeable than crushed rocks and may present a more hydrogeochemical favourable behaviour. When used as a raw material, such as in cement crude, bricks or concrete, chemical stability and potential leaching are critical for acceptability as a substitute for primary raw materials. Fine grain milling offers easy access to oxidation and facilitates sulphide decomposition. Long term stability and leaching behaviour need to be assessed, and kinetic testing may be useful.

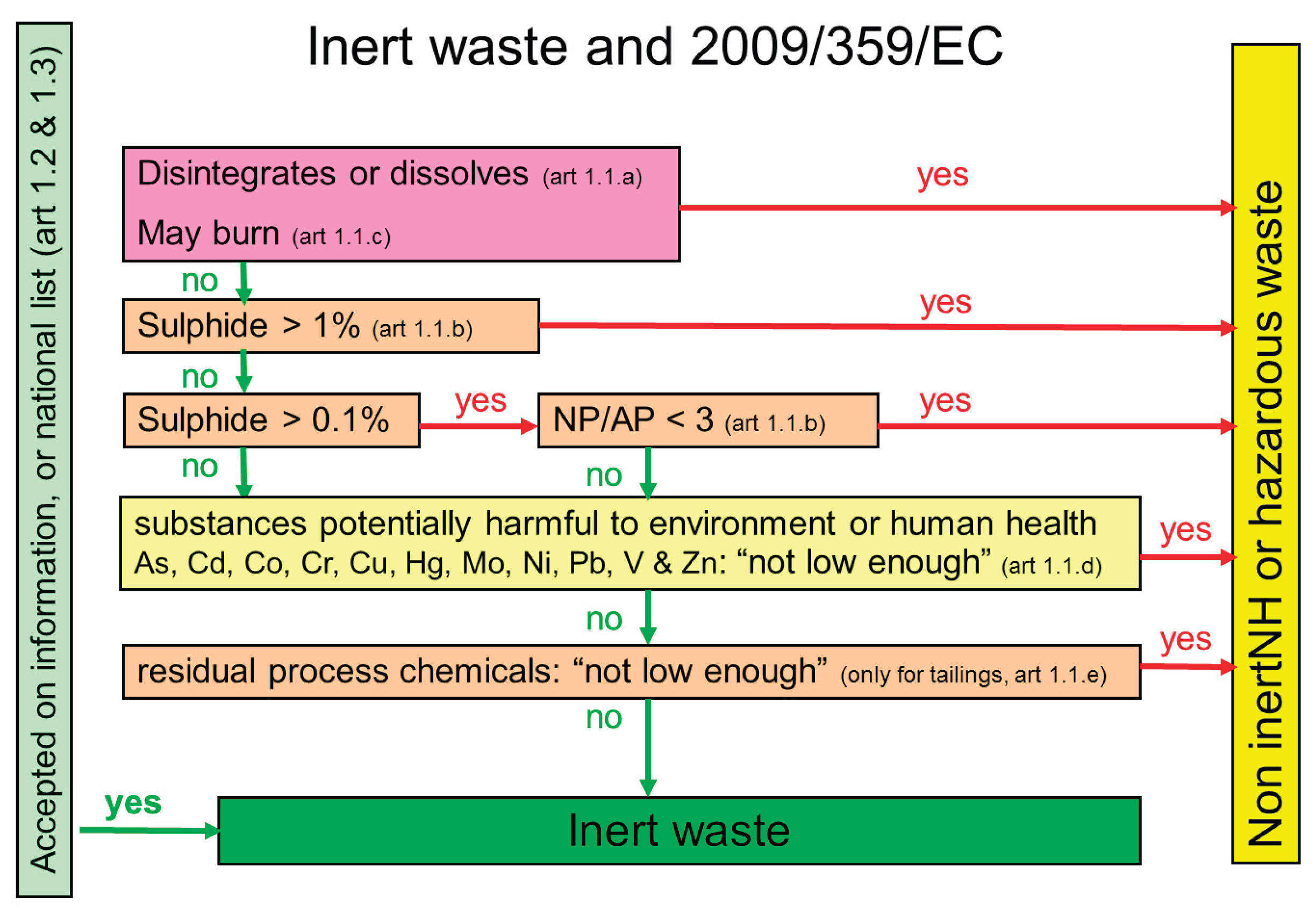

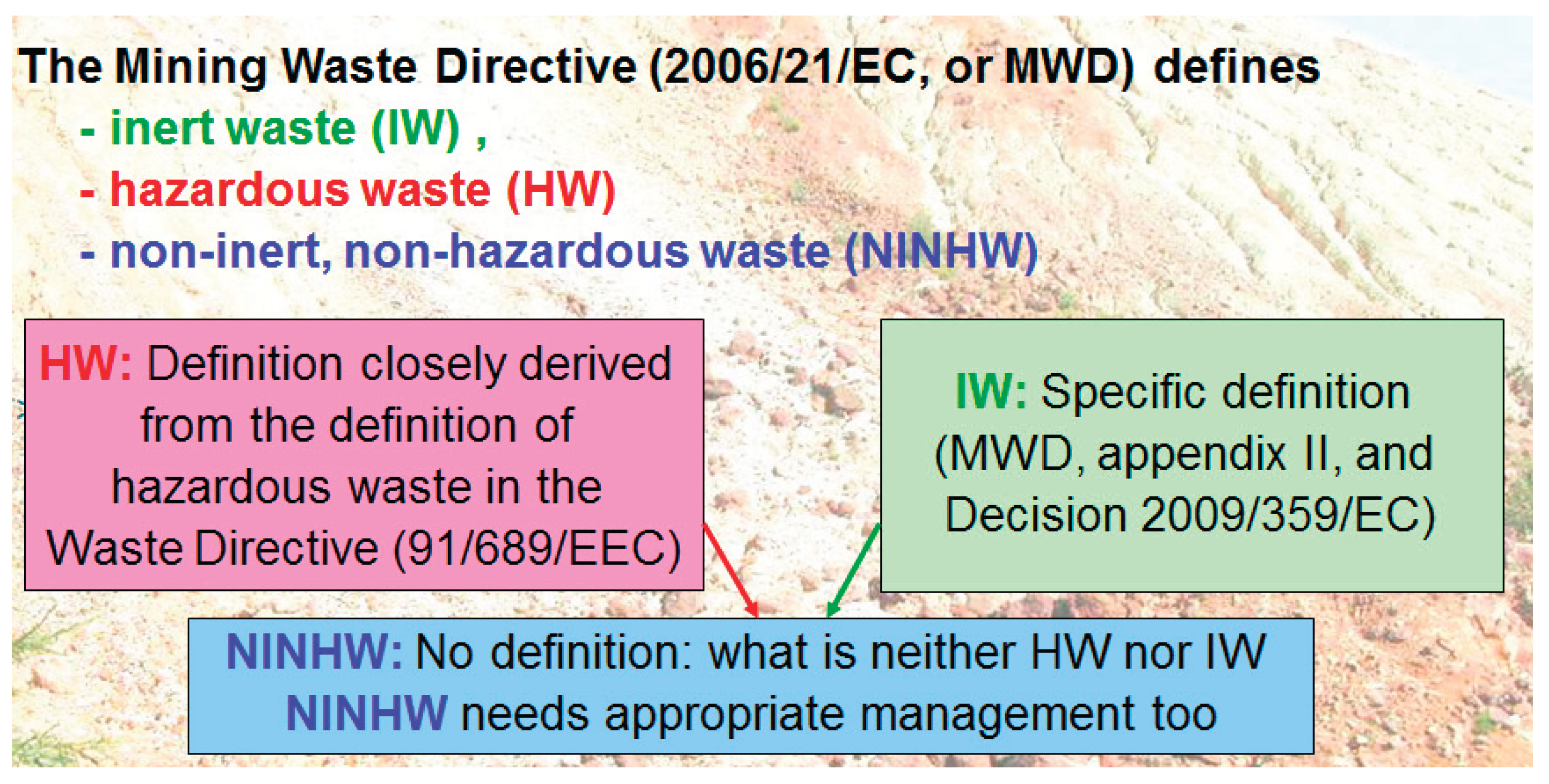

3.6. According to Risk, and Legislation

The main categories defined by the European Mining Waste Directive (2006/21/EC, or MWD) are inert waste (IW), hazardous waste (HW), and non-inert, non-hazardous waste (NINHW) [

45,

46]. Equivalents can be found in most national regulations or international guidelines.

The European definition of hazardous mining waste is closely derived from the definition of hazardous waste in the Waste Directive (91/689/EEC or MWD), while the definition of inert mining waste is specific (MWD, appendix II, and Decision 2009/359/EC).

Figure 6.

Waste categories in the extractive industry [

45,

46].

Figure 6.

Waste categories in the extractive industry [

45,

46].

Similar definitions can be found worldwide. For Australia, Canada, USA or Brazil, it is often at the State level rather than country level. Definitions in China are included in the National Hazardous Waste Catalogue. In developing countries, national definitions are often derived from those in use with the mining partners.

This classification is used to define waste management categories, their specifications and monitoring needs, but it does not contain any dispositions on the potential future waste. This use is regulated by the dispositions on general waste, including the producer responsibility, despite the specificities of mining waste. Furthermore, the waste regulations are designed with freshly produced waste in mind, and not for legacy waste, with no provisions on reuse for remediation. This has until now hampered most initiatives for considering legacy waste as a possible resource.

3.6.1. Inert Waste Definition

The inert category is based on an extended characterisation scheme, intended at demonstrating the innocuity of the waste, or at minimising the risk of any further hazard. The European scheme is summarised on

Figure 7.

3.6.2. Hazardous Waste Definition

In Europe, no specific definition of hazardous waste is applicable to mining waste. The general provisions of the waste regulation

1991/689/EC (

Table 5) are applicable:

Some of the following substances may be found in mining waste, due to present or past extraction machinery or processing reagents (as listed in waste regulation 1991/689/EC):

residue from substances employed as solvents

halogenated organic substances not employed as solvents, excluding inert polymerized materials

tempering salts containing cyanides

mineral oils and oily substances (e.g. cutting sludges, etc.)

oil/water, hydrocarbon/water mixtures, emulsions

substances containing PCBs and/or PCTs (e.g. dielectrics etc.)

tarry materials arising from pyrolytic treatment (e.g. still bottoms, etc.)

pyrotechnics and other explosive materials.

3.6.3. Not Inert, Not Hazardous

This category, hereunder abbreviated NINH, is by far the most bulky. It has no specific definition, waste that does not fit the inert criteria nor meets the hazardous thresholds is implicitly NINH. There are no specific rules and regulations for NINH mining waste in Europe beyond the general waste regulations, usually less stringent than rules for hazardous waste. Waste management facilities for this category follow design rules applicable to very large volumes.

3.6.4. The Key Role of Sulphide and Sulphate in Inertness

Hazardous waste definitions are not specific to mine waste. They are based on potential effects. They cannot be directly related with the mining activity classification. However, most ores, and therefore mining waste, contains sulphides, to the exception of Al and many Fe ores. These minerals and their oxidised forms, especially sulphates, are specifically targeted by inertness criteria (Figure 8) and are the main reason for failing the inert status.

Among the hazardousness criteria, H5 and H13 (

Table 3) are the most likely affected by sulphides. This is especially true when sulphides are accompanied by potentially toxic substances (As, Cd, Pb,...) which are likely to be more mobile in the presence of sulphides, sulphates or sulphur-generated acidity.

3.7. According to Circular Economy Potential

None of the above classifications can provide by itself a robust framework for circular economy potential evaluation of mining waste, as the constraints for a safe beneficial use vary widely between waste types, but all of them have nevertheless to be taken into account.

3.7.1. According to Waste Producer

Research is carried out by the mining and mineral chemical industries in order to develop applications for their waste flows: coal fly ash [

56,

57], aluminium waste [

58,

59], phosphogypsum [

60], in order to improve their profitability and reduce waste expenditures. Even if this is carried out in-house, such developments belong to circular economy and improve the sustainability of the producer. The phosphogypsum example is particularly meaningful, due to the very large size of its producing industry, and to the need for finding an outlet for this waste. The limitations are the concentration of radioactive elements [

61] and potentially toxic trace elements (the so-called “heavy metals”).

3.7.2. According to User Sector

Due to the low intrinsic value of mining waste and the high cost of its transportation, having a potential user as close as possible from the waste flow or waste stock is primordial. The most widespread user sector, anywhere, is the building materials and civil engineering sector [

62].

Some more specific mineral transformation industries can use large amounts of specific types of mining waste. An example of this is the aluminate sector for the cement and concrete industry, which is able to use high Al waste, usually bauxite residues [

63]. In this case, the user industry may be implemented closer to the waste source, in order to ship only higher value products, and even on the mine site itself. Similarly, plaster board manufacture can use phosphogypsum [

60,

64]. This requires careful monitoring for undesirable substances, including fluoride and radionuclides [

65], which could lead to regulatory health issues with the end product.

The concrete sector [

26] has by itself large needs in raw materials which may be problematic for territories. This is a driver to tap alternative sources such as mineral waste, hence the early consideration of mining waste.

3.7.3. Trying to Find New Sources for Scarce Substances, Esp. Critical Elements

When a need quickly arises for a substance which was not actively mined before, or which is in a short supply, it may be cost- and energy-effective to extract it from waste. When opening new mines has to face social reluctance and legacy waste is an environmental burden, it is tempting to extract new commodities from old waste while remediating the legacy site. A well known example is the Kasese former copper mine in Uganda, which tailings were a serious threat for the catchment, but were also a rich untapped stock of cobalt [

24,

37]. Gold tailings in Witwatersrand are currently re-examined as a potential uranium resource [

66].

4. Residual Waste Rates of Mining Waste Reprocessing

4.1. Residual Waste Rates of Commodity Reprocessing

Preliminary statement: there is no such thing as zero waste mining. The proportion of the mined commodity in the mined volume is always less than 50% and may be as low as 0.01%.

Waste production is driven by the equation:

W=WR + Mx(1-b)

where W is the total amount of waste produced, WR is the total waste rock (not beneficiated), M the total ore mined (excluding waste rock) and b is the mined ore grade. The commodity production will be C=Mxb.

The equation is, for a single commodity of cut-off grade b :

W=WR + M x (1-b)

where W is the total amount of waste produced, WR is the total waste rock (not beneficiated), M the total ore mined (excluding waste rock) and b is the mined ore grade.

For several recovered commodities, it would become

W=WR + M x ∑i(1-bi)

For the sake of simplicity let us continue with one commodity.

The waste equation may be written as

W=WR + MW

where MW is the total ore mined, minus the amount of commodities recovered (M x b). MW is the mined waste.

It becomes

W=WR1 + WR2 + MW x (1-h) + MW x h

where W is the total amount of waste produced, WR1 is the total waste rock that can be beneficiated, WR2 is the total amount of waste rock that cannot be beneficiated), MW is the total mined waste, h is the proportion of mined ore that is too hazardous for disposal, and that cannot be economically processed to become non-hazardous.

It may become

W=WR1 + WR2 + MW1 + MW2

where W is the total amount of waste produced, WR1 is the total waste rock that can be beneficiated, WR2 is the total amount of waste rock that cannot be beneficiated), MW1 is the total amount of mined waste for which a sustainable reuse is possible or which can be processed to make it reusable, and MW2 the total amount of mined waste that is too hazardous for disposal, and that cannot be economically processed to become non-hazardous.

In this case,

VW = WR1 + MW1 (the total amount of valorisable waste, for which a sustainable reuse is possible)

RW = WR2 + MW2 (the total amount of residual waste, for which no sustainable reuse is economically possible)

VR = VW/(VW+RW) (or VW/W) is the achievable valorisation ratio of the mining operation. It is obviously a time variable figure, according to many factors such as manpower or energy costs and to current commodity prices.

In no case, VR can reach, or come close to, its maximal value of one. The highest VR values are achieved by aggregate quarrying and sand mining. On the opposite, very low VR values are met for rare or precious commodities (gold, PGEs, diamond…). VW and VR are not usually documented, because they do not have direct relevance for mining economics. On the opposite, RW is better known, as it affects mine closure costs.

4.2. Residual Waste Rates of Civil Engineering Reprocessing

A similar calculation can be attempted, but with more limitations. In civil engineering, the valorisable part is usually one fraction (clean aggregate) or two fractions (aggregate and valorisable fines), with MW1/MW2 higher than for commodity reprocessing. The residual waste fraction is therefore lower, and final repositories may be smaller in favourable cases.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

The beneficial use of mining waste is obviously to be encouraged, with several key benefits to be expected :

saving primary resources and subsequently extending the availability lifetime of highly needed mineral resources,

reducing the volume of legacy mining waste, and its environmental impacts,

developing a resource beneficiation industry which is less greedy in energy and water.

In this perspective, beneficial use of mining waste is fully in line with circular economy thinking.

Examples of successful mine waste remining for commodities are many, and will be even more in the future. But examples of beneficial use as raw materials or for civil engineering are not so many, though it seems to be easier.

5.1. Beneficial Use for Commodities Recovery

This part of mining waste beneficial use is indeed in the scope of circular economy, as it saves primary resources without adding to waste generation. It cannot reduce significantly the volume of legacy waste unless raw materials production is a side activity. But, by reworking it to better standards, it contributes to impact reduction and site remediation.

It is however still a mining activity, organised with the traditional exploration-processing-waste storage and closure cycles and rules. A circular economy classification of existing waste will be of little use, as this waste is still chiefly an ore, and there will still be waste stocks afterwards, even if cleaner. The focus of this paper is therefore limited to the use of mining waste as raw minerals.

5.2. Key Criteria Conditioning Beneficial Use as Raw Minerals

The most important criteria identified by this review are:

grain size and homogeneity, which will screen possible large scale applications, especially civil engineering and construction,

chemical stability and potential contaminants release: in mine waste, the abundance of sulphides is a key criterion, as it controls acid drainage (ARD) and metals leaching, now and on the long term,

the local needs in raw minerals and the distance between the waste stock and the end user.

The economic value of the available waste is often close to zero, and the cost of primary extraction minerals is usually low. The economic benefit of waste reuse is difficult to demonstrate, unless the indirect benefits are identified and quantified. First of them is the contribution of beneficial use to mining site remediation, an expensive activity which is rarely taken in charge by the mine operator.

5.3. Constraints of Mining Waste Reuse When Compared with Primary Material

Mining waste reuse for commodities obeys to mining economics, and requires traditional mining technology. The size of operations is usually smaller than new mines, and may be even small enough to require mobile technologies. The capital needs and associated risks are not so high. The carbon and water footprint are usually smaller. The smaller output compared to a large mine may be a limitation if the commodities customers require a dependable resource availability.

Risk factors are more important when the beneficial use is as raw materials. The end user can be a minerals provider or user, or a civil engineering contractor. They need to be sure that no liability will result from the beneficial use, due to the mining waste origin. For instance, the raw materials should not degrade with time, disaggregate, collapse or release contaminants at significant levels. This would be likely for potentially acid generating materials. This requires extensive testing, which cost may exceed the cost of primary minerals extraction. Even when the beneficial use is expected to be profitable, the precautionary principle or the public acceptance for waste reuse may preclude any operation.

Mining waste processing in order to reuse part of it is still an extractive industry, and it has to take care of its own waste management and later site cleanup. It cannot be a Zero Waste operation. On the opposite, it contributes to the legacy site cleanup, which would have to be supported otherwise by public money.

5.3. Refining Criteria and Developing Tests

Lottermoser [

67] stressed the fact, that circular economy applications require innovative protocols, beyond what was developed for environmental purposes, such as compliance leaching tests. The present review demonstrated that none of the available criteria is able by itself to give a reliable indication of the viability of a beneficial use application, and the suitability of a given waste for this application. All of them have some relevance for this purpose, but the potential user needs to weigh them up according to the specificities of his application and the considered waste stock.

Would a formal classification of waste based on the criteria listed in this paper help ? It will be at least difficult, due to the diversity of criteria, of regulations and to the lack of consensus on economic and indirect benefits. Such a classification will be complex to build, due to the large diversity of waste types and of possible beneficial uses.

Developing public acceptance and stakeholder confidence is another obstacle which cannot be surmounted by tests compliance alone. Compliance is required, and transparency on test results will help, but other benefits need to be demonstrated to gain adhesion.

On the opposite, selecting a shortlist of possible beneficial uses from local material needs or from waste availability and characteristics seems to be a sensible approach, with specific test thresholds.

Author Contributions

All contents was elaborated by the author, who submits the paper under his responsibility.

Funding

This research received no external funding. It was based on experience gathered by the author during his participation to many projects, but no specific part of the paper is a result of any of them.

Data Availability Statement

All data used for this paper are accessible through the references.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to express his gratitude to Pr. XXX, for advice, language proofing and final revision, to anonymous reviewers for the constructive remarks, and to the many mining professionals who welcomed him on their sites and discussed waste issues. The author has reviewed and edited the output and takes full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation (2013) Towards the circular economy. Economic and business rationale for an accelerated transition, vol. 1. Retrieved from https://emf.thirdlight.com/file/24/xTyQj3oxiYNMO1xTFs9xT5LF3C/Towards%20the%20circular%20economy%20Vol%201%3A%20an%20economic%20and%20business%20rationale%20for%20an%20accelerated%20transition.pdf on 2025-02-11.

- European Commission (2015) An EU action plan for the Circular Economy. COM/2015/0614 final. Retrieved on 2017-09-03 from http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52015DC0614&from=EN.

- Ling, Z.S., Jaafar, M.H. and Ismail, N. (2025) The knowledge, attitudes and practices in circular economy: A review of industrial waste management in China. Cleaner Waste Systems 11, 100276. [CrossRef]

- Geissdoerfer, M., Savaget, P., Bocken, N.M.P., & Hultink, E.J. (2017) The Circular Economy – A new sustainability paradigm? Journal of Cleaner Production, 143, 757–768. [CrossRef]

- ICMM (2016) Mining and metals and the circular economy. Retrieved on 2025-02-09 from https://www.icmm.com/website/publications/pdfs/responsible-sourcing/icmm-circular-economy-1-.pdf.

- Stahel, W.R. & Reday-Mulvey, G. (1981) Jobs for tomorrow : the potential for substituting manpower for energy. Vantage Press, New York, 116 p.

- Pearce, D.W. & Turner, R.K. (1989) Economics of Natural Resources and the Environment. Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0801839870.

- ICMM (2017) Ensure sustainable production and consumption patterns. Retrieved on 2017-11-05 from https://www.icmm.com/en-gb/metals-and-minerals/making-a-positive-contribution/responsible-consumption-and-production.

- ICMM (2024) Tools for Circularity. Retrieved on 2025-02-09 from https://www.icmm.com/website/publications/pdfs/innovation/2024/guidance_tools-for-circularity.pdf.

- Kalisz, S., Kibort, K., Mioduska, J., Lieder, M. and Małachowska, A. (2022). Waste management in the mining industry of metals ores, coal, oil and natural gas - A review. Journal of Environmental Management 304, 114239. [CrossRef]

- Hudson-Edwards, K.A., Jamieson, H.E. & Lottermoser, B.G. (2011) Mine Wastes: Past, Present, Future. Elements, 7, 375–380. [CrossRef]

- Eurostat (2024) Waste statistics. Retrieved on 2025-02-10 from https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Waste_statistics.

- Lottermoser, B. (2010) Mine Wastes. Characterization, Treatment and Environmental Impacts. Springer. [CrossRef]

- Mudd, G.M. (2004) Sustainable Mining : An Evaluation of Changing Ore Grades and Waste Volumes. International Conference on Sustainability Engineering & Science, Auckland, New Zealand - 6-9 July 2004.

- Northey, S., Mohr, S., Mudd, G.M., Weng, Z. & Giurco, D. (2014) Modelling future copper ore grade decline based on a detailed assessment of copper resources and mining. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 83, 190-201. [CrossRef]

- West J. (2011) Decreasing Metal Ore Grades: Are They Really Being Driven by the Depletion of High-Grade Deposits? Journal of Industrial Ecology 15(2), 165–168. [CrossRef]

- Calvo, G., Mudd, G., Valero, Al. and Valero, An. (2016) Decreasing Ore Grades in Global Metallic Mining: A Theoretical Issue or a Global Reality? Resources, 5, 36. [CrossRef]

- UNEP (2020a) UNEP environmental, social and sustainability framework. Retrieved on 2025/03/11 from https://wedocs.unep.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.11822/32022/ESSFEN.pdf.

- ICMM (2003). ICMM Sustainable Development Framework; International Council on Mining and Metals: London, UK, pp. 2–17. . Retrieved on 2025-02-09 from https://www.icmm.com/en-gb/our-principles.

- Cotrina-Teatino, M.A. and Marquina-Araujo, J.J. (2025). Circular economy in the mining industry: A bibliometric and systematic literature review. Resources Policy 102, 105513. [CrossRef]

- Tayebi-Khorami, M., Edraki, M., Corder, G. and Golev, A. (2019) Re-Thinking Mining Waste through an Integrative Approach Led by Circular Economy Aspirations. Minerals, 9(5), 286; [CrossRef]

- Agricola G (1556) De re metallica. Translated by Hoover HC, Hoover LH (1950). Dover Publications, New York. ISBN 0-486-60006-8. Available from https://gutenberg.org/ebooks/38015.

- Vallero, D.A., Blight, G. (2019) Mine Waste: A Brief Overview of Origins, Quantities, and Methods of Storage. Waste (Second Edition) - A Handbook for Management Chapter 6, 129-151. [CrossRef]

- Briggs, A.P., Millard, M. (1997) Cobalt recovery using bacterial leaching at the Kasese Project, Uganda, Conference Proceedings. International Biohydrometallurgy Symposium IBS97, BIOMINE 97. Glenside, South Australia: Australian Mineral Foundation, 1997, pp. M2.4.1–M2.4.11.

- Morin, D., d’Hugues, P. (2007) Bioleaching of a cobalt-containing pyrite in stirred reactors: a case study from laboratory scale to industrial application. In: Rawlings, D.E., Johnson, D.B. (Eds.), Biomining, Chapter 2. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, pp. 35–55.

- El Machi, A.; El Berdai, Y.; Mabroum, S.; Safhi, A.e.M.; Taha, Y.; Benzaazoua, M.; Hakkou, R. (2024) Recycling of Mine Wastes in the Concrete Industry: A Review. Buildings 2024, 14, 1508. [CrossRef]

- Golev, A., Gallagher, L., Vander Velpen, A., Lynggaard, J.R., Friot, D., Stringer, M., Chuah, S., Arbelaez-Ruiz, D., Mazzinghy, D., Moura, L., Peduzzi, P., Franks, D.M. (2022). Ore-sand: A potential new solution to the mine tailings and global sand sustainability crises. Final Report. Version 1.4 (March 2022). The University of Queensland & University of Geneva. Retrieved on 2025-02-09 from https://espace.library.uq.edu.au/view/UQ:503a3fd.

- Žibret, G., Lemiere, B., Mendez, A.-M., Cormio, C., Sinnett, D., Cleall, P., Szabó, K., & Carvalho, M. T. (2020). National Mineral Waste Databases as an Information Source for Assessing Material Recovery Potential from Mine Waste, Tailings and Metallurgical Waste. Minerals, 10(5), 446. [CrossRef]

- Lemière, B. (2012) Mining the waste: prospecting valuable residues, optimising processes with modern technology, sustainably remediating legacy sites. Eurasia-MENA Mining Summit, Istanbul, June 6th, 2012.

- Ermakova, D., Jin Whan Bae, Wainwright, H., & Vujic, J., 2022. Remining And Restoring Abandoned Us Mining Sites: The Case For Materials Needed For Zero-Carbon Transition. Nuclear Energy and Fuel Cycle Division, Oak Ridge National Laboratory report ORNL/TM-2022/2591, 30p. Retrieved from https://info.ornl.gov/sites/publications/Files/Pub182920.pdf on 2025/04/27.

- Maest, A.S. (2023). Remining for Renewable Energy Metals: A Review of Characterization Needs, Resource Estimates, and Potential Environmental Effects. Minerals 2023, 13(11), 1454; [CrossRef]

- Nelson, P.P. & Spiller, D.E. (2024) Handbook of Recycling (Second Edition) Chapter 18 - Mine tailings, pp. 287-297, . [CrossRef]

- Lottermoser, B. (2011) Recycling, Reuse and Rehabilitation of Mine Wastes. Elements, 7, 405–410. [CrossRef]

- Kinnunen, P., Karhu, M., Yli-Rantala, E., Kivikytö-Reponen, P. and Mäkinen, J. (2022) A review of circular economy strategies for mine tailings. Cleaner Engineering and Technology, 8, June 2022, 100499. [CrossRef]

- Nakhaei, F., Corchado-Albelo, J., Alagha, L., Moats, M. & Munoz-Garcia, N. (2025). Progress, challenges, and perspectives of critical elements recovery from sulfide tailings. Separation and Purification Technology 354, 4, 128973. [CrossRef]

- Kaur, R., Nexhip, C., Krippner, D., George-Kennedy, D., & Routledge, M., 2011. Kennecott-Outotec ‘Double Flash’ Technology After 16 Years. Conference: 13th International Flash Smelting Congress, Zambia, Oct 2011. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Colin-Nexhip/publication/305281555_KENNECOTT-OUTOTEC_%27DOUBLE_FLASH%27_TECHNOLOGY_AFTER_16_YEARS/links/5786b6f508aec5c2e4e2f44e/KENNECOTT-OUTOTEC-DOUBLE-FLASH-TECHNOLOGY-AFTER-16-YEARS.pdf on 2025/04/26.

- Natarajan, K.A. (2018) Bioleaching of Zinc, Nickel, and Cobalt, Biotechnology of Metals Chapter 7, Editor(s): K.A. Natarajan, Elsevier, p.151-177, ISBN 9780128040225, . [CrossRef]

- New Century Resources (2020) Century Mine Project, Geology & Resources. Retrieved from https://web.archive.org/web/20200803085645/https://www.newcenturyresources.com/century-mine-project/geology-resources/ on 2025/04/28.

- Gibson, B.A.K.K., Nwaila, G., Manzi, M., Ghorbani, Y., Ndlovu, S., & Petersen, J. (2023). The valorisation of platinum group metals from flotation tailings: A review of challenges and opportunities. Minerals Engineering 201, 108216. [CrossRef]

- Moats, M., Alagha, L. & Awuah-Offei, K. (2021). Towards resilient and sustainable supply of critical elements from the copper supply chain: A review. Journal of Cleaner Production, 307, 127207. [CrossRef]

- Lin, H-F, Weng, W., Zhong, S-P & Qiu, G-Z (2022). Enhanced recovery of zinc and lead by slag composition optimization in rotary kiln. Transactions of Nonferrous Metals Society of China 32, 9, 3110-3122. [CrossRef]

- Gayana, B C and Ram Chandar, K (2018) A study on suitability of iron ore overburden waste rock for partialreplacement of coarse aggregates in concrete pavements. IOP Conf. Ser.: Mater. Sci. Eng. 431 102012. Retrieved from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/328817701_A_study_on_suitability_of_iron_ore_overburden_waste_rock_for_partial_replacement_of_coarse_aggregates_in_concrete_pavements [accessed Feb 10 2025].

- INAP (The International Network for Acid Prevention) (2018) Global Acid Rock Drainage Guide. Retrieved from https://www.gardguide.com/index.php?title=Main_Page on 2025-06-26.

- American Concrete Institute (2024). Benefits of using slag cement. Retrieved from https://www.concrete.org/frequentlyaskedquestions.aspx on 2025/05/13.

- Lemière, B., Cottard, F. & Piantone, P. (2011) Mining waste characterization in the perspective of the European mining waste directive. In: Geochemistry for risk assessment of metal contaminated sites, workshop, 25th International Applied Geochemistry Symposium 2011, Rovaniemi, Finland.

- European Commission (2009) Reference Document on Best Available Techniques for Management of Tailings and Waste-Rock in Mining (BREF). Retrieved on 2017-11-05 from http://eippcb.jrc.ec.europa.eu/reference/BREF/mmr_adopted_0109.pdf.

- Australian Government (2011) A Guide To Leading Practice Sustainable Development In Mining. Leading Practice Sustainable Development Program for the Mining Industry https://www.industry.gov.au/sites/default/files/2019-04/lpsdp-a-guide-to-leading-practice-sustainable-development-in-mining-handbook-english.pdf.

- UNEP (2020b) Global Industry Standard on Tailings Management. Retrieved on 2025-07-08 at https://www.unep.org/resources/report/global-industry-standard-tailings-management.

- Mining Association of Canada (2021) A Guide to the Management of Tailings Facilities version 3.2. Retrieved from https://mining.ca/resources/guides-manuals/mac-tailings-guide-version-3-2/ on 2025/05/13.

- Brown, T. (2019) Mineral planning factsheet : construction aggregates. Nottingham, UK, British Geological Survey, 32pp. Retrieved from https://nora.nerc.ac.uk/id/eprint/524079/1/aggregates_2019.pdf on 2025/04/23.

- Mitchell, C.J. (2015) Construction aggregates: evaluation and specification. Retrieved on 2025-06-02 from: https://nora.nerc.ac.uk/id/eprint/510909/1/Construction%20aggregates%20evaluation%20and%20specification.pdf.

- Almeida, J., Ribeiro, A.B., Santos Silva, A., Faria, P. (2020) Overview of mining residues incorporation in construction materials and barriers for full-scale application. Journal of Building Engineering 29 (2020) 101215. [CrossRef]

- de Groot, G.J., van der Sloot, H.A. (1992) Determination of leaching characteristics of waste materials leading to environmental product certification. ASTM Spec. Tech. Publ. 1123, 149–170355. [CrossRef]

- Gao, S., Li, J.S., Zhang, S. and Poon, C.S. (2025) A state-of-the-art review of solid waste leaching mechanisms and evaluation methodologies. Waste Management 204, 114941. [CrossRef]

- US-EPA (1992) SW-846 Test Method 1311: Toxicity Characteristic Leaching Procedure. Retrieved on 2025-07-08 at https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2015-12/documents/1311.pdf.

- Fedorka, W., KnowIes, J. & Castleman, J. (2015) Reclaiming and Recycling Coal Fly Ash for Beneficial Reuse with the START”’ Process. World of Coal Ash (WOCA) Conference in Nasvhille, TN - May 5-7, 2015. Retrieved on 2017-11-05 from http://www.flyash.info/2015/168-fedorka-2015.pdf.

- US-EPA (2013) Methodology for Evaluating Encapsulated Beneficial Uses of Coal Combustion Residuals. Retrieved on 2017-12-07 at https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2014-12/documents/ccr_bu_method.pdf.

- Schwarz, M. & Lalík, V. (2012) Possibilities of Exploitation of Bauxite Residue from Alumina Production, Recent Researches in Metallurgical Engineering - From Extraction to Forming, Dr Mohammad Nusheh (Ed.), ISBN: 978-953-51-0356-1, InTech, retrieved on 2017-12-07 from: http://www.intechopen.com/books/recentresearches-in-metallurgical-engineering-from-extraction-to-forming/possibilities-of-exploitation-of-bauxiteresidue-from-alumina-production-.

- Hertel, T., Blanpain, B. & Pontikes, Y. (2016) A Proposal for a 100 % use of Bauxite Residue Towards Inorganic Polymer Mortar, Journal of Sustainable Metallurgy, 2, 4, 394-405. [CrossRef]

- Garrabrants A.C., Kirkland R.A., Van der Sloot H.A., Price L.M., and Kosson D.S. (2009) Leaching Assessment for the Proposed Beneficial Use of Red Mud and Phosphogypsum as Alternative Construction Materials. WASCON 2009 conference, Lyon, France.

- US-EPA (2025) TENORM: Fertilizer and Fertilizer Production Wastes. Retrieved on 2025-07-03 at https://www.epa.gov/radiation/tenorm-fertilizer-and-fertilizer-production-wastes.

- Essex, J. (2010) Increasing local reuse of building materials. Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers - Waste and Resource Management, 163, 4, 183-189. [CrossRef]

- Pöllmann, H. (2012) Calcium Aluminate Cements – Raw Materials, Differences, Hydration and Properties. Reviews in Mineralogy & Geochemistry, 74, 1-82. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J., Li, X., Zhao, Y., Shu, Z., Wang, Y., Zhang, Y. & Shen, X., 2020. Preparation of paper-free and fiber-free plasterboard with high strength using phosphogypsum. Construction and Building Materials, 243, 118091, . [CrossRef]

- Bhavan, P. 2014. Guidelines for Management, Handling, Utilisation and Disposal of Phosphogypsum Generated from Phosphoric Acid Plants. Central Pollution Control Board (Ministry of Environment, Forests & Climate Change) Report, 64 p. Retrieved from https://cpcb.nic.in/technical-guidelines/ on 2025/04/23.

- Gerstmann, B. S., Fairclough, M., Lottermoser, B. G., & Winde, F. (2022). Witwatersrand Gold Tailings as a Possible Uranium Resource: Opportunities and Constraints (p. 8 p.). In IAEA (International Atomic Energy Agency), Management of naturally occurring radioactive material (NORM) in industry. Proceedings series STI/PUB/1998, ISSN 0074–1884.

- Lottermoser, B. (2023) A review of protocols and tests to characterize mine wastes for circular economy strategies. In Proceedings of the EGU General Assembly 2023, Vienna, Austria, 24–28 April 2023. EGU23-1797. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).