Path

p depends on the execution of instructions, which can be uniquely labeled, such as:

This nondeterministic instruction, labeled

, can be split into two deterministic ones:

Each deterministic instruction is assigned a unique label (e.g.,

).

2.1. Textbook Approach

To capture the step-by-step behavior of

N on

, we focus on the aforementioned instruction

as it applies to the following TM configuration, denoted as

C:

The symbol

indicates that the machine is currently in state

, with its head oriented towards the tape cell containing the symbol

a. This information can be expressed propositionally through the Boolean variable

, where indices

i and

j denote the row

i and column

j in a tableau—a matrix of

rows and

columns, as shown in

Table 1.

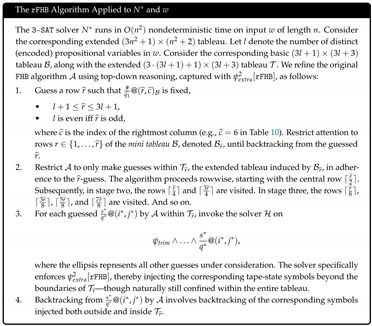

We analyze the execution of instructions

and

separately—both outcomes are depicted on the left and right sides of

Table 2, respectively—before combining them into one implication. This results in an expression of the form:

where both

and

take the form

. Ultimately, this forms a 3cnf-formula corresponding to the notion of a

window. By taking conjunctions over all

windows defined by

N, and for each row and column in the tableau, we derive a 3cnf-formula

of size

.

To the best of our knowledge, every approach to

-completeness ultimately hinges on the notion of “a tableau,” a concept that can be traced back to Cook’s seminal paper [

7]. The work of Cook in the United States was mirrored by Levin’s concurrent developments in the Soviet Union [

8,

9].

Specifically, the two tableau illustrations presented in

Table 2 are modified adaptations of the exemplars found in Sipser [

10](p. 280). (Sipser’s textbook treatment uses “

” instead of “

” when referring to a

window [

10](p. 280). However, this is merely a cosmetic variation on the concept at hand.) Similarly, Papadimitriou introduces the notion of a “computation table” in Section 8.2 of his work [

11]. In the same spirit, Hopcroft, Motwani, and Ullman refer to a comparable structure as “an array of cell/ID facts” [

12](p. 443). Aaronson also echoes this idea of a tableau, albeit using more informal language in his accessible book [

13](p. 61).

2.2. Our Approach

Can the step-by-step behavior of

N on

be represented using a compact Horn formula,

, instead of a 3cnf-formula,

? We answer affirmatively in [

2] by introducing an

extended tableau with

rows and

columns, explicitly storing the instruction labels, such as

and

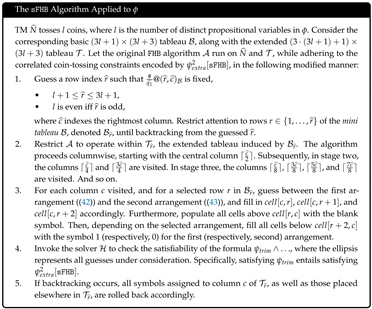

. Two parts of such a tableau are shown in

Table 3, illustrating only one change occurring at a time. This contrasts with the two simultaneous changes depicted in each illustration in

Table 2.

We arrived at this result by adopting Aaronson’s vision of philosophy as a “scout” that explores and maps out “intellectual terrain for science to

later move in on, and build condominiums on …” [

13](p. 6, original emphasis). Building on this metaphor, and in dialogue with the perspectives of Dean [

14], Tall [

15], and Turner [

16], our investigation explores the interplay between two distinct modes of reasoning: Aristotelian, step-by-step thinking and Platonic, static reasoning—as largely formulated by Linnebo and Shapiro [

17].

These contrasting perspectives are illustrated in the following two quotes:

Lance Fortnow as an Aristotelian:

A Turing machine has a formal definition but that’s not how I think of it. When I write code, or prove a theorem involving computation, I feel the machine processing step by step. …I feel it humming along, updating variables, looping, branching, searching until it arrives as its final destination and gives an answer. (Quoted from Lance Fortnow’s blog post [

18].)

Robin K. Hill as a Platonist:

A Turing Machine is a static object, a declarative, a quintuple or septuple of the necessary components. The object

that constitutes the transition function that describes the action is itself a set of tuples. All of this is written in appropriate symbols, and just sits there. (Quoted from Robin K. Hill’s CACM blog post [

19].)

In our published work [

2], we analyze these two intellectual modes in the context of nondeterministic TMs, and ultimately show how to transform the 3cnf-formula

, which captures the step-by-step behavior of

N on

, into the compact Horn formula

.

Technically, we employ an

extended tableau—also called a

tableau with labels. Here, the TM configurations are represented in rows

where

. The two auxiliary rows,

and

, each contain exactly one instruction label, and row

contains precisely one

symbol, where

s is a tape symbol and

q a state symbol. Corresponding to

Table 3, we define in [

2] the Horn formula

of size

literals.

Remark 3. The formula is called in [2].

The innovation behind

is representing the binary choice between

and

as a conjunction of two formulas:

yielding a Horn formula. In contrast, Sipser’s textbook treatment expresses this choice with a disjunction, recall formula (

4), which necessitates a 3cnf-formula.

To be more precise,

represents the knowledge derived from

through both upward and downward reasoning in our extended tableau. We express this derivation with the following formula:

which is equivalent to:

where

is a placeholder for a literal. The formula is a Horn formula. Likewise for

and derived knowledge

, which amounts to:

where the subscript

i stands for:

.

To convey the essence of our prior contribution without providing formal definitions, let

denote the knowledge derived from

for some instruction label

t of machine

N stored in

, with

. In [

2], we demonstrate the construction of multiple Horn formulas, including:

where the latter formula represents

N’s step-by-step behavior. We use “

V” to denote “vertical” reasoning within the extended tableau, and “

H” to signify “helicopter” reasoning across a block of rows, ranging from

to

.

2.3. Explicating

More rigorously, consider an arbitrary nondeterministic polynomial time TM , or N for short. Let the tape alphabet , state set Q, and label set be extracted from the specifications of machine N.

Definition 1.

A nondeterministic polynomial time Turing machine, denoted as , is defined as N = , a nondeterministic Turing machine in accordance with Definition A5, which serves as a decider with a running time of — as specified in Definition A8, where n and k represent the length of input w and some constant, respectively.

Remark 4. Without loss of generality, the nondeterminism associated with TM N consists solely of binary choices. For each such choice, say between instructions and , the movement of is to the left (−), while the movement of is to the right (+).

Recall that the propositional formula

is defined as:

with

To elucidate the variables within

, we define:

For each

i and

j ranging from 1 to respectively

and

, and for every symbol

s in

, we introduce a Boolean variable,

. We have a total of

such variables.

The formula

reflects the coordination between the

V and

H subsystems. This coordination is achieved primarily by ensuring that specific vertical symbol conversions in the extended tableau are carried out in two distinct stages.

For instance, rather than directly converting symbol

into symbol

when traversing a column in the extended tableau top-down, the

V subsystem first transforms

into the intermediate label

, and only then into the symbol

. This deliberate two-step conversion guarantees that

V produces a unique intermediate trace—namely, the instruction label

of machine

N—which can then be identified by the

H subsystem. This example, involving the label

, corresponds to the following deterministic machine instruction:

In general however, an instruction of

N is nondeterministic. For each binary choice of

N, such as

we must first

determinize the instruction by splitting it into two distinct deterministic ones:

Each deterministic instruction is assigned a unique label (e.g.,

). Notably, determinizing an instruction that is already deterministic—such as

,

, or

—has no effect.

After applying

determinization to all uniquely labeled instructions of

N, we ensure that

V, when selecting any deterministic instruction label

t, explicitly records the label

t as an intermediate trace in the extended tableau. Examples of

and

are shown in the center column, in the left and right illustrations, respectively, in

Table 3. Consequently,

H reads label

t from the tableau and acts accordingly. The behavior of

V and

H is described by Horn formulas

and

, respectively, as formally defined in [

2, Section 4].

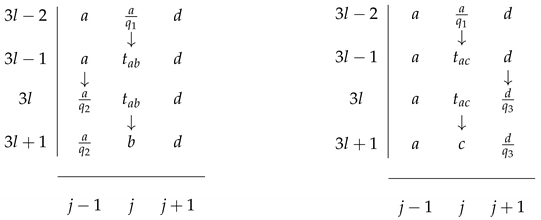

Fundamentally, any conversion between two distinct tape symbols, say from

a to

b, in any column of the extended tableau, must occur through an intermediate trace.

Table 4 provides an illustration, relying on the label

and, more precisely, the following instruction of machine

N:

The marked symbol

a in the top row in

Table 4 can only change into the marked symbol

b in the bottom row via an intermediate trace, such as

.

A few additional clarifications regarding

Table 4 are necessary. First, each symbol change from row to row is indicated with an arrow for better visualization. Second, the boxes surrounding symbols

a and

b are merely included to improve readability.

To summarize, the novelty of our approach in [

2] is twofold. First, we introduce an

extended tableau that explicitly stores instruction labels, enabling single-symbol changes between consecutive rows. Second, we analyze the tableau from both a vertical perspective (

) and a helicopter perspective (

), combining them into the succinct Horn formula:

.

2.4. Explicating

We now explicate the second conjunct of equation (

5), which pertains exclusively to the deterministic instructions

t of the nondeterministic TM under consideration; specifically, those satisfying

, as defined in Definition A7.

We distinguish between the subsets

and

, along with their associated formulas

and

, respectively. The overall formula for deterministic transitions is thus expressed as:

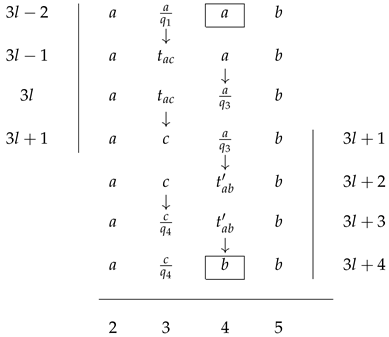

We present the explicit definition of the first conjunct,

, leaving the construction of

to the reader by symmetry:

where

and

, with

. For precise definitions of the operators such as

,

, and

, see Definition A6.

The formula

comprises

literals. An analogous construction, along with the same complexity bound, applies to

. Together, these formulas encapsulate traditional top-down reasoning. Here, the top is row

, going via row

to the bottom row

. This aligns with the established result that such reasoning can be fully captured by a Horn formula [

20](p. 35).