1. Introduction

Digital health technologies (DHTs) encompass a broad ecosystem of digital tools, including software, connected devices, and data services, designed to enhance health outcomes across the care continuum —from prevention to diagnosis, monitoring, treatment, and rehabilitation. These tools range from telehealth platforms and mobile health applications to wearable sensors, remote patient monitoring infrastructures, artificial intelligence (AI) and machine-learning (ML) algorithms for clinical decision-making and predictive analytics, as well as AI agents and digital twins that mimic patient physiology. Digital therapeutics (DTx) represent a specific, regulated subset of DHTs. They are software-driven, evidence-based interventions that deliver a direct therapeutic action to prevent, manage, or treat a medical condition. Unlike general wellness apps, DTx make explicit clinical claims, undergo rigorous evaluation (often as Software as a Medical Device, SaMD), and must meet regulatory, quality, privacy, and cybersecurity requirements similar to those of other medical technologies [

1,

2,

3]. A broader overview of the promise of digital healthcare technologies is provided elsewhere [

4].

Nevertheless, although these strategies offer great potential for research and clinical care in different fields of medicine, several key challenges remain. For example, a recent study showed a significant overrepresentation of male figures in generative AI text-to-image outputs [

5]. Many of these limitations arise from the gender health data gap. It involves two main issues, including insufficient research on conditions affecting women and the use of male-based data as the medical standard [

6]. Consequently, to prevent the perpetuation of existing inequalities and data disaggregation, these technologies must be developed and validated using diverse, representative datasets that minimize gender bias and prevent discriminatory outcomes [

7].

This narrative review aims to explore the current state of DTx and its potential applications. We also examine how DHTs are applied to animals within the One Digital Health framework. Finally, ethics issues and challenges related to data bias are addressed, with a focus on future directions and recommendations as well as the steps necessary to improve inclusivity and minimize health disparities.

2. Clinical Evidence of Digital Health Technologies

Clinical evidence suggests the potential efficacy of DTx in managing chronic diseases. For instance, in a multicenter randomized trial assessing the HERB digital therapeutic system for hypertension, patients under 65 who were not on antihypertensive medications experienced significant reductions in 24-hour systolic blood pressure using a smartphone app-based intervention compared to lifestyle counselling alone [

8]. Another trial (HERB-DH1) showed favorable trends toward improved home blood pressure control when behavioral change content was delivered via a smartphone application [

9]. These studies demonstrate the potential of DTx to enhance adherence, improve self-care, and potentially delay the need for pharmacological treatment.

Beyond cardiovascular disease, DTx has demonstrated utility in mental health care, particularly through programs that integrate smartphone-based monitoring with coaching or structured feedback. In a randomized trial comparing web-based coaching versus access to digital resources alone for depression, patients in the coached group achieved superior symptom improvement, highlighting the role of human facilitation in maximizing the effectiveness of digital tools [

10]. Furthermore, home-based digital interventions, such as Moving Through Glass, have been shown to improve balance and mobility in individuals with neurodegenerative diseases [

11].

The scope of DTx extends to vulnerable populations. Among solid organ transplant recipients, who face a high risk from vaccine-preventable infections, digital systems have been proposed to centralize immunization records and deliver automated vaccine reminders, potentially addressing barriers such as care fragmentation and provider miscommunication [

12]. Similarly, in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), qualitative research reveals both opportunities and challenges for DHT adoption. Clinicians cited patient digital literacy, device data quality, and the lack of integration into clinical workflows as critical barriers [

13]. Despite promising results, implementation of DTx remains uneven, hindered by structural, regulatory, and behavioral obstacles. Nonetheless, programs like DOORS (Digital Opportunities for Outcomes in Recovery Services), which provide digital literacy training to patients with severe mental illness, demonstrate how targeted interventions can bridge the "second digital divide" and enable equitable access to digital care tools [

14].

3. Wearable Technologies and Remote Patient Monitoring

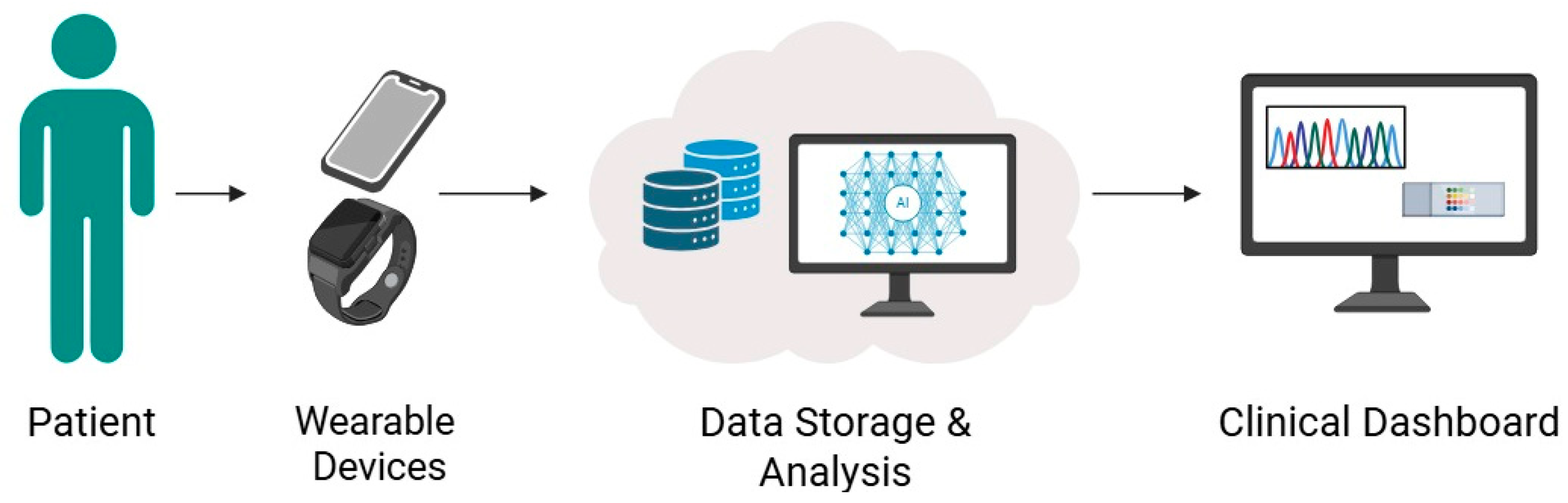

Wearable devices and remote monitoring technologies have become increasingly relevant in chronic disease management, allowing real-time tracking of physiological parameters while enhancing patient engagement. These tools range from photoplethysmography (PPG)-enabled wristbands to smartwatches and implantable devices that transmit continuous data to clinicians (

Figure 1).

In cardiovascular care, wearables have demonstrated clinical utility in various populations. Broers et al. evaluated a lifestyle intervention supported by wearable tracking in patients with cardiovascular disease, showing that personalized feedback led to improved physical activity and behavioral change across multicenter cohorts in Spain and the Netherlands [

15]. Similarly, the CHIEF-HF trial utilized Fitbit smartwatches to monitor step counts and correlate them with patient-reported health status using the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ). The study found a significant non-linear association between daily step count and both symptom severity and physical limitation scores, reinforcing the value of wearables in tracking heart failure progression [

16].

Furthermore, wearables offer opportunities for early detection of clinical deterioration. Hochstadt et al. demonstrated the feasibility of using smartphone-connected PPG to detect cardiac rhythm abnormalities, including atrial fibrillation, in ambulatory settings with high signal quality and accuracy [

17]. In a different context, Wu et al.[

18] implemented a remote monitoring system for COPD patients that integrated wearable sensors, air quality metrics, and mobile app data. Their system successfully predicted exacerbations using ML models, exemplifying the integration of environmental and biometric data for remote respiratory care.

The application of wearables in older or frail populations is also advancing. Liu et al. [

19] demonstrated that remote follow-up using smartwatches after transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) in elderly patients was both feasible and clinically valuable, enabling the early detection of complications and reducing unnecessary hospital visits [

19]. Complementarily, the REMOTE-CIED trial evaluated remote patient monitoring (RPM) in patients with heart failure and implantable defibrillators. The results indicated improved clinical outcomes and reduced burden of in-person follow-ups [

20].

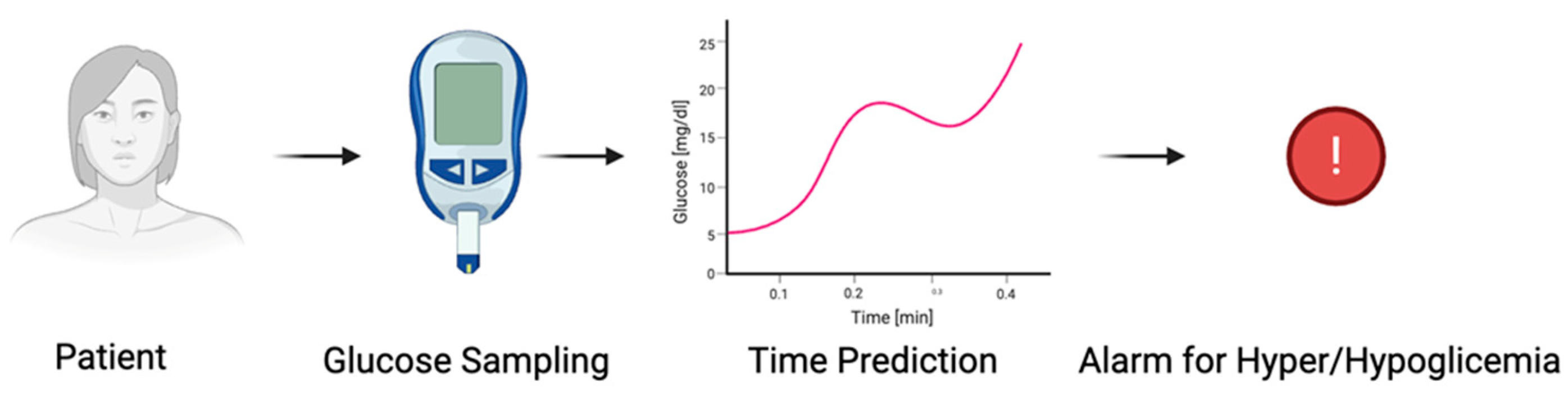

Thanks to their versatility and effectiveness in predicting sugar levels, systems for continuous glucose tracking are among the most widely used wearable medical devices. To avoid or at least reduce the risk of complications in diabetic people, continuous blood glucose monitoring [

21] reports to the patient when it is essential to give an insulin injection. Therefore, predictive algorithms should be capable of acquiring and processing data in real-time (with high sampling rate and fast transitions), producing fast responses with high accuracy for the relationship between both future glucose levels and prediction time. This process should guarantee a low computational weight (

Figure 2).

For this aim, the AutoRegressive Moving Average (ARMA) is one of the most implemented predictive algorithms. It is a mathematical model that utilizes past values of a time series modulated by specific coefficients to predict the future level of blood glucose, anticipating hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia events within an arbitrary time window [

22]. Investigations demonstrated the capability of ARMA models to obtain data predictions with time-dependent root mean square errors (RMSEs) at 30, 45, and 60 minutes, respectively, of ~9.04, ~11.84, and ~14.82 mg/dl. However, these models are not generalizable for every situation and are strictly dependent on the specific subject characteristics; therefore, the hyperparameters should be trained and computed based on the individual patient's history data. This key limitation is particularly evident when a multiple comparison is performed between different ML techniques [

23]. For example, a generalized ARMA model performed poorly compared to individual (i.e., patient-centered) ARMA models, especially when the input time series had non-linear patterns or when a prediction for a timestamp higher than 30 minutes was required [

24].

Despite these limitations, remote monitoring technologies in diabetes care have demonstrated tangible clinical benefits. A retrospective cohort study involving patients with type 1 diabetes revealed that a commercially available remote glucose monitoring platform facilitated more individualized care and helped identify those most in need of intervention [

25]. Additionally, in the context of gestational diabetes, RPM was associated with improved maternal glycemic control and better neonatal outcomes compared to standard in-person care [

26].

Furthermore, research focused on neurodegenerative diseases. In Parkinson's disease (PD), wearable sensors allow continuous monitoring of key physiological parameters, including movement, tremor, gait, balance, and sleep patterns [

27,

28]. The data collected on motor and non-motor symptoms are analyzed using AI algorithms, enabling timely and precise therapeutic adjustments [

29]. Moreover, these technologies provide valuable insights into disease progression, treatment efficacy, and quality of life [

30].

4. Artificial Intelligence-Based Applications

The integration of AI into wearable and portable medical technologies is reshaping how patient data is interpreted, enabling earlier detection, refined risk stratification, and personalized intervention across diverse clinical domains. These AI-powered devices process high-resolution physiological signals, often collected passively, and translate them into clinically actionable information.

One of the most prominent applications is cardiology. Dhingra et al. [

31] developed an AI model capable of predicting new-onset heart failure using single-lead ECGs acquired from portable devices. The model was validated across large and diverse cohorts in the US, UK, and Brazil, demonstrating a 3- to 7-fold increase in heart failure risk among individuals with a positive AI screen, with superior performance compared to traditional clinical scores. Similarly, Lopez-Jimenez et al. [

32] validated a cuffless, wearable blood pressure monitor powered by AI, which demonstrated robust accuracy across all hypertension categories.

The capacity of AI to facilitate early detection of critical events was explored by Beqari et al. [

33], who applied a machine learning algorithm (NightSignal) to wearable-derived biometrics in patients recovering from cardiothoracic surgery. The algorithm identified 81% of complications up to two days before symptom onset, demonstrating the potential of AI in optimizing perioperative care.

In women's health, Luo et al. validated machine learning models that predict ovulation and menstruation based on wrist skin temperature and heart rate recorded by a wearable device. The study reported an AUC of 0.869 for fertile window prediction, underlining how AI can support reproductive planning in both regular and irregular menstruators [

34].

Moreover, AI is also being deployed in visual diagnostics. The WISDOM AI study by Rochon et al. implemented a computer vision system to triage surgical wound images submitted via smartphones. The algorithm achieved a sensitivity of 89% in identifying wounds that required priority reviews, thereby helping to reduce the clinical burden while maintaining safety standards [

35]. Finally, a study by Shah et al. [

36] introduced an AI system embedded in a consumer-grade smartwatch to detect pulseless electrical activity, suggesting the feasibility of population-scale arrest detection (

Table 1).

5. Artificial Intelligence Agents and Digital Twins

AI agents are autonomous systems that analyze data and make decisions or predictions. DTs are virtual models of individual patients that simulate their physiological responses. Together, they enable personalized medicine by forecasting health outcomes and tailoring treatments based on a patient's unique biological and clinical data.

In artificial agents and multi-agent systems, a specific role is assigned to each agent. Consequently, researchers have utilized these systems to simulate the work dynamics present in medical teams, reproducing the procedures that occur during triage, for example, in the field of emergency medicine and clinical diagnosis. Thus, agents can act at various points in the clinical process, such as the preliminary evaluation of the patient, the establishment of a diagnosis, and the determination of the required treatments, along with the allocation of resources [

37].

These technologies can enable real-time, individualized simulations of human physiology, supporting precision diagnostics, predictive modeling, and personalized treatment strategies. Therefore, they have the potential to transform medicine into a proactive, data-driven discipline rooted in each patient's unique biological and clinical profile [

38]. Another example of this is the Medical Decision-Making Agent (MDAgent). It is a system designed to process multimodal medical data by leveraging large language models (LLMs) to make decisions based on the complexity of a patient's case. MDAgent operates in four stages. First, it assesses the complexities of the clinical case. Second, it brings together an appropriate team, ranging from a single physician to a multidisciplinary group. Third, it conducts an analysis and synthesis of the response using techniques. Lastly, an MDA consolidates all the inputs to provide a coherent and informed final response. These teams can work independently or in collaboration with each other [

37],

A major contributor to this progress is the ongoing growth of comprehensive biochemical resources such as the Virtual Metabolic Human (VMH) in combination with AI-driven technologies. Given each update, these databases enrich DT models by providing deeper biological insights, thereby improving their precision and predictive capabilities.

The expanding VMH platform integrates a range of new biological data, including [

39]:

Human metabolic reactions, genes, and enzymes.

Disease-specific metabolic profiles.

Host–microbiome metabolic interactions.

Pharmacometabolic and drug-response pathways.

This influx of data supports high-resolution simulation of individual physiology. For example, a DT enhanced with newly annotated metabolic pathways can offer superior prediction of efficacy and potential side effects compared to static models, based on the following approach:

A baseline DT is created using a patient's multi-omics data (e.g., genomic and metabolomic profiles) aligned with the VMH framework.

Computational models predict physiological responses to various conditions such as medications, diets, or diseases.

Simulation outputs are compared with observed clinical outcomes to assess accuracy.

Based on discrepancies, the DT is refined, and insights feed back into knowledge bases like VMH, forming a self-improving feedback loop.

Due to robust VMH integration, DTs enable virtual trials to identify which patient subpopulations may benefit from—or be harmed by—specific treatments, facilitating more accurate dosing. Modeling disease trajectories based on individual metabolic maps enhances early detection and risk assessment, particularly for complex conditions such as metabolic syndrome or cancer. Ultimately, predicting personal responses to interventions—ranging from dietary adjustments to probiotics—enables the development of deeply personalized treatment and prevention strategies [

40].

Moreover, starting from diagnostic imaging with AI, it is possible to generate DTs that have a wide range of applications. One example is the Lung-DT framework, which combines AI and Internet of Things (IoT) data to classify and monitor lung diseases from real-time chest X-rays [

41]. An application in the vascular field is CardioVision. This framework combines diagnostic imaging with a segmentation model to create DTs of the aorta, aortic valve, and associated calcifications, from which morphological measurements can be obtained and hemodynamic modeling can be supported, thus offering innovative tools to assist in personalized therapeutic decision-making. This approach also enables the simulation of TAVR procedures and the evaluation of devices [

42].

Through ongoing feedback between knowledge base expansion and model refinement, DTs are evolving into increasingly sophisticated virtual surrogates. This dynamic interplay is steering medicine toward a future where healthcare is not only personalized but also anticipatory and highly adaptive to individual biology.

6. Application of DHT in Animals: The One Digital Health Framework

In this scenario of immense interactions between medicine, people, and technology, animals cannot be ignored, whether they are pets, working animals, farm animals, or wild animals. Technology has become increasingly accessible to everyone, and the global pet wearable market continues to grow. These devices enable owners and veterinarians to monitor their animals' health. Moreover, they can be used for unique identification, tracking, and monitoring their behavior and developmental activities continuously. Pet-specific wearables range from smart harness devices fastened around the ' 'pet's body, which are integrated with sensors to monitor body language, posture, sound, body temperature, and heart rate, to smart collars that utilize Global Positioning System (GPS). New technology and products are being created each year [

43]. Wearable sensors have countless applications in dairy and beef cattle, with garment-like devices being the most popular among farmers. Neck-mounted accelerometers were used in the studies to monitor feeding and rumination behaviors, and the guild was accurately assessed [

44]. Wearable sensors have significantly enhanced the tracking and analysis of wildlife migration, not only for mammals but also for birds and marine mammals [

45].

Advantages of using these technologies are very similar to those of human medicine, including remote monitoring of vital signs, pets and owners do not need to travel to send data to a veterinarian, improved accessibility of care, facilitate tele-triage, monitor animal health in real time, collect data for research, etc. Additionally, dogs and cats may behave differently in a veterinary hospital compared to their at-home settings, and other animals, such as wild ones, are not accustomed to the presence of humans [

43]. These devices can be used to monitor pain or movement after surgery, or to track respiratory rate, heart rate, and pulse oximetry in cases of chronic disease. For example, working/police dogs can be constantly monitored to avoid hyperthermia when they are under stress and performing very physically demanding jobs [

43].

Other technologies include infrared thermography, which can be used in cattle to detect mastitis or diagnose lameness, in horses to assess musculoskeletal injuries, and in dogs and cats to evaluate osteoarthritis or neoplasia [

41].

In veterinary medicine, the problems associated with applying these technologies include species difference, because the research is not equally distributed across animal types, with pets and major farm animals receiving more attention than exotic and wild species; environmental sensitivity; cost and complexities of some devices; ethical consideration for pets, farm animals and wild animals; and finally training data limitation as veterinary applications often have limited data availability unlike human massive data sets [

43]. The last strategy is to transform the One Health into a One Digital Health framework, becoming a real-time, interconnected system capable of integrating data derived from health information of multiple species and environmental areas. In this way, the spread of particular diseases could be more predictable, considering the movements of animals and humans, as well as the habitat preference of the pathogen [

43,

44].

7. Data Bias and Ethical Implications

The present topic raises significant concerns about data bias and ethical implications. For example, Yfantidou et al. [

46] reported that wearable-based systems disproportionately under-represent individuals with chronic conditions (such as diabetes or hypertension) and women, with such biases further amplified in machine learning models. In a systematic review, Gianfrancesco et al. [

47] confirmed that ML algorithms trained on imbalanced datasets routinely underperform for minorities, with downstream effects on the accuracy of digital twin applications as confirmed by Norori et al. [

48].

Regarding social and gender bias, Weinberger et al. [

49] emphasized that most DTs fail to incorporate gender-sensitive and socioeconomic variables, thereby reinforcing biased clinical predictions and reducing model trust for underserved groups. Furthermore, it was underlined that health data systems, including wearables, often default to male-centric models, which can result in poor sensitivity to female-specific symptoms and patterns, ultimately perpetuating clinical misdiagnosis and unequal care [

50].

Additionally, pediatric applications face unique challenges, as reported by Drummond et al. [

51]. The authors highlighted that limited historical data, difficulties obtaining consent, and the need to preserve children's autonomy all contribute to data quality concerns and ethical complexity in digital twin systems for chronic disease management. Finally, broader socio-ethical assessments, including interviews with industry, policy, and civil society stakeholders, indicate persistent risks related to data ownership, privacy, inequality, and disruption of existing care structures in healthcare DT implementations [

52].

To address these issues, mitigation strategies are increasingly being proposed and evaluated. Regulatory frameworks, such as the European Union's General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and the FDA's Digital Health Innovation Action Plan, have established standards for transparency, privacy, and user consent, explicitly requiring explainability and audit trails in medical AI systems. Algorithmic transparency is also being promoted, with interpretability methods like SHAP and LIME gaining traction to help clinicians and patients understand model predictions and identify potential biases, as outlined by Amann et al. [

53]. Moreover, Herzog et al. [

54] proposed that building trustworthy medical AI requires shifting from isolated technical fixes to a holistic, "ecosystem" approach, where adaptive governance structures, embedded ethical principles, and ongoing impact assessments foster justified trust among all stakeholders. Additionally, Boardman [

55] argued for the formalization of "ethical analytics" as a new, practically-oriented sub-discipline within data science, insisting that ethics must be foundational and interwoven into every stage of AI system development. Finally, Norori et al. [

48] call for an " open science" approach focused on inclusivity and transparency, recommending participant-centered development, responsible and privacy-preserving data sharing, and the use of inclusive data standards and interoperable formats. Sharing code and algorithms, generating synthetic data to augment underrepresented groups, and employing participatory science approaches to directly involve vulnerable communities are further proposed.

8. Future Directions and Recommendations

Given the current limitations and concerns, different recommendations could be suggested. For example, the field must first commit to inclusive, representative datasets that encompass gender, life course (including pediatrics), ethnicity, and socioeconomic strata. This process is mandatory for reducing algorithmic bias and improving generalizability [

7]. Additionally, robust interoperability and open standards (e.g., FHIR, USCDI) are crucial for privacy-preserving data exchange across institutions and sectors [

56]. Sustainable innovation requires human-centered, participatory design that engages patients and clinicians throughout ideation, prototyping, and deployment to optimize usability, adherence, and trust [

57]. Fourth, evidence generation should migrate toward hybrid evaluation frameworks that blend randomized controlled trials with real-world evidence, adaptive designs, and formal cost-effectiveness analysis to accelerate iteration while satisfying regulators and payers [

58]. Continuous post-market surveillance—combining automated drift detection with clinician-reported outcomes—should become mandatory to assure ongoing safety and effectiveness of AI-driven DTx in diverse real-world settings [

59]. Finally, end-to-end transparent governance and "ethical analytics"—embedding explainability, accountability, and public oversight from development through decommissioning—are essential for building a trustworthy biomedical-AI ecosystem [

60] (

Figure 3).

9. Conclusions

There is a growing interest in applications of DHTs, DTx, and AI-enabled wearables for enhancing preventive and therapeutic strategies across numerous clinical domains. Nevertheless, although evidence supports their clinical utility, ethical, regulatory, and implementation challenges must be systematically addressed. Algorithmic bias, data privacy risks, and the limited inclusion of vulnerable populations are the main critical issues. Moreover, large-scale adoption is hindered by structural barriers, such as poor interoperability, low digital literacy, and the complex integration of these tools into clinical workflows. Therefore, to truly consider the power of these technologies, there is a need for data ecosystems that are inclusive and representative, algorithms that are transparent and easy to understand, clear regulatory pathways, and evaluation frameworks that blend clinical trials with real-world evidence. From this perspective, the One Digital Health framework enhances the role of digital technologies by bringing together human, animal, and environmental health. This evolutionary process is necessary to fully realize the potential of these technologies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.C. and D.G.; methodology, R.F.; software, M.G. and P.G.; validation, M.T.A., F.F., M.D., C.A.C., C.P., D.M., and E.S.; formal analysis, V.G.; investigation, M.C.; resources, M.C.; data curation, A.T., M.B.; writing—original draft preparation, M.C.; all authors participated in writing—review and editing; visualization, A.S., G.D'O., C.I., F.S., E.B., and V.G.; supervision, B.B. and C.J.F.; project administration, P.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data analyzed in this article are included in the manuscript. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DHTs |

Digital Health Technologies |

| DTx |

Digital Therapeutics |

| AI |

Artificial Intelligence |

| ML |

Machine Learning |

| AUC |

Area Under the Curve |

| CAST |

Center for Advanced Studies and Technology |

| CIED |

Cardioverter-Implantable Electronic Device |

| COPD |

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease |

| DHTs |

Digital Health Technologies |

| DOORS |

Digital Opportunities for Outcomes in Recovery Services |

| DTs |

Digital Twins |

| ECG |

Electrocardiogram |

| ARMA |

AutoRegressive Moving Average |

| RMSE |

Root Mean Square Error |

| MDAgent |

Medical Decision-Making Agent |

| LLMs |

Large Language Models |

| IoT |

Internet of Things |

| TAVR |

Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement |

| FDA |

US Food and Drug Administration |

| GPS |

Global Positioning System |

| FHIR |

Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources |

| GDPR |

General Data Protection Regulation |

| HERB-DH1 |

Hypertension digital therapeutic trial HERB-DH1 |

| KCCQ |

Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire |

| LIME |

Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations |

| PPG |

Photoplethysmography |

| RPM |

Remote Patient Monitoring |

| SaMD |

Software as a Medical Device |

| SHAP |

SHapley Additive exPlanations |

| USCDI |

United States Core Data for Interoperability |

| VMH |

Virtual Metabolic Human |

References

- von Huben A, Howell M, Howard K, Carrello J, Norris S. Health technology assessment for digital technologies that manage chronic disease: a systematic review. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2021;37(1):e66. [CrossRef]

- Yan K, Balijepalli C, Druyts E. The Impact of Digital Therapeutics on Current Health Technology Assessment Frameworks. Front Digit Health. 2021;3:667016. [CrossRef]

- Hong JS, Wasden C, Han DH. Introduction of digital therapeutics. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2021;209:106319. [CrossRef]

- Yeung AWK, Torkamani A, Butte AJ, et al. The promise of digital healthcare technologies. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1196596. [CrossRef]

- Currie G, Hewis J, Hawk E, Rohren E. Gender and Ethnicity Bias of Text-to-Image Generative Artificial Intelligence in Medical Imaging, Part 2: Analysis of DALL-E 3. J Nucl Med Technol. 2025;53(2):162-168. [CrossRef]

- Lego, VD. Uncovering the gender health data gap. Cad Saude Publica. 2023;39(7):e00065423. [CrossRef]

- Cirllo D, Catuara-Solarz S, Morey C, et al. Sex and gender differences and biases in artificial intelligence for biomedicine and healthcare. NPJ Digit Med. 2020;3:81. [CrossRef]

- Kario K, Nomura A, Kato A, et al. Digital therapeutics for essential hypertension using a smartphone application: A randomized, open-label, multicenter pilot study. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2021;23(5):923-934. [CrossRef]

- Kario K, Nomura A, Harada N, et al. A multicenter clinical trial to assess the efficacy of the digital therapeutics for essential hypertension: Rationale and design of the HERB-DH1 trial. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2020;22(9):1713-1722. [CrossRef]

- MacLean S, Corsi DJ, Litchfield S, et al. Coach-Facilitated Web-Based Therapy Compared With Information About Web-Based Resources in Patients Referred to Secondary Mental Health Care for Depression: Randomized Controlled Trial. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(6):e15001. [CrossRef]

- Tunur T, DeBlois A, Yates-Horton E, Rickford K, Columna LA. Augmented reality-based dance intervention for individuals with Parkinson's disease: A pilot study. Disabil Health J. 2020;13(2):100848. [CrossRef]

- Feldman AG, Atkinson K, Wilson K, Kumar D. Under immunization of the solid organ transplant population: An urgent problem with potential digital health solutions. Am J Transplant. 2020;20(1):34-39. [CrossRef]

- Slevin P, Kessie T, Cullen J, Butler MW, Donnelly SC, Caulfield B. Exploring the barriers and facilitators for the use of digital health technologies for the management of COPD: a qualitative study of clinician perceptions. QJM. 2020;113(3):163-172. [CrossRef]

- Hoffman L, Wisniewski H, Hays R, et al. Digital Opportunities for Outcomes in Recovery Services (DOORS): A Pragmatic Hands-On Group Approach Toward Increasing Digital Health and Smartphone Competencies, Autonomy, Relatedness, and Alliance for Those With Serious Mental Illness. J Psychiatr Pract. 2020;26(2):80-88. [CrossRef]

- Broers ER, Gavidia G, Wetzels M, et al. Usefulness of a Lifestyle Intervention in Patients With Cardiovascular Disease. Am J Cardiol. 2020;125(3):370-375. [CrossRef]

- Golbus JR, Gosch K, Birmingham MC, et al. Association Between Wearable Device Measured Activity and Patient-Reported Outcomes for Heart Failure. JACC Heart Fail. 2023;11(11):1521-1530. [CrossRef]

- Hochstadt A, Havakuk O, Chorin E, et al. Continuous heart rhythm monitoring using mobile photoplethysmography in ambulatory patients. J Electrocardiol. 2020;60:138-141. [CrossRef]

- Wu CT, Li GH, Huang CT, et al. Acute Exacerbation of a Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Prediction System Using Wearable Device Data, Machine Learning, and Deep Learning: Development and Cohort Study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2021;9(5):e22591. [CrossRef]

- Liu X, Fan J, Guo Y, et al. Wearable Smartwatch Facilitated Remote Health Management for Patients Undergoing Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement. J Am Heart Assoc. 2022;11(7):e023219. [CrossRef]

- Chiu CSL, Timmermans I, Versteeg H, et al. Effect of remote monitoring on clinical outcomes in European heart failure patients with an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator: secondary results of the REMOTE-CIED randomized trial. Europace. 2022;24(2):256-267. [CrossRef]

- Jancev M, Vissers TACM, Visseren FLJ, van Bon AC, Serné EH, DeVries JH, de Valk HW, van Sloten TT. Continuous glucose monitoring in adults with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetologia. 2024 May;67(5):798-810. [CrossRef]

- Reifman J, Rajaraman S, Gribok A, Ward WK. Predictive monitoring for improved management of glucose levels. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2007 Jul;1(4):478-86. [CrossRef]

- Eren-Oruklu M, Ci-nar A, Quinn L, Smith D. Estimation of future glucose concentrations with subject-specific recursive linear models. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2009 Apr;11(4):243-53. [CrossRef]

- Goel S, Sharma S. A Comparative Study of Time Series Models for Blood Glucose Prediction. In: Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Information Management and Machine Intelligence: ICIMMI 2021 (pp. 81-91). Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore.

- Crossen SS, Romero CC, Lewis C, Glaser NS. Remote glucose monitoring is feasible for patients and providers using a commercially available population health platform. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023;14:1063290. [CrossRef]

- Kantorowska A, Cohen K, Oberlander M, et al. Remote patient monitoring for management of diabetes mellitus in pregnancy is associated with improved maternal and neonatal outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2023;228(6):726.e1-726.e11. [CrossRef]

- Lukšys D, Jonaitis G, Griškevičius J. Quantitative Analysis of Parkinsonian Tremor in a Clinical Setting Using Inertial Measurement Units. Parkinsons Dis. 2018;2018:1683831. [CrossRef]

- Bougea, A. Application of Wearable Sensors in Parkinson’s Disease: State of the Art. Journal of Sensor and Actuator Networks. 2025; 14(2):23. [CrossRef]

- Kehnemouyi YM, Coleman TP, Tass PA. Emerging wearable technologies for multisystem monitoring and treatment of Parkinson's disease: a narrative review. Front Netw Physiol. 2024;4:1354211. [CrossRef]

- Bougea A, Angelopoulou E. Non-Motor Disorders in Parkinson Disease and Other Parkinsonian Syndromes. Medicina (Kaunas). 2024;60(2):309. [CrossRef]

- Dhingra LS, Aminorroaya A, Pedroso AF, et al. Artificial Intelligence-Enabled Prediction of Heart Failure Risk From Single-Lead Electrocardiograms. JAMA Cardiol. 2025;10(6):574-584. [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Jimenez F, Deshmukh A, Bisognano J, et al. Development and Internal Validation of an AI-Enabled Cuff-less, Non-invasive Continuous Blood Pressure Monitor Across All Classes of Hypertension. J Cardiovasc Transl Res. 2025;18(2):280-290. [CrossRef]

- Beqari J, Powell JR, Hurd J, et al. A Pilot Study Using Machine-learning Algorithms and Wearable Technology for the Early Detection of Postoperative Complications After Cardiothoracic Surgery. Ann Surg. 2025;281(3):514-521. [CrossRef]

- Luo C, Su YF, Ren YY, et al. Prediction of the fertile window and menstruation with a wearable device via machine-learning algorithms. Reprod Biomed Online. 2025;51(1):104795. [CrossRef]

- Rochon M, Tanner J, Jurkiewicz J, et al. Wound imaging software and digital platform to assist review of surgical wounds using patient smartphones: The development and evaluation of artificial intelligence (WISDOM AI study). PLoS One. 2024;19(12):e0315384. [CrossRef]

- Shah K, Wang A, Chen Y, et al. Automated loss of pulse detection on a consumer smartwatch. Nature. 2025;642(8066):174-181. [CrossRef]

- Kim Y, Park C, Jeong H, Grau-Vilchez C, Chan Y, Xu X, McDuff D, Lee H, Ghassemi M, Breazeal C, Park HW. (2024). A demonstration of adaptive collaboration of large language models for medical decision-making. 10. 48550/Arxiv. 2411. 00248.

- Böttcher L, Fonseca LL, Laubenbacher RC. Control of medical digital twins with artificial neural networks. Philos Trans A Math Phys Eng Sci. 2025;383(2292):20240228. [CrossRef]

- Kimpton LM, Paun LM, Colebank MJ, Volodina V. Challenges and opportunities in uncertainty quantification for healthcare and biological systems. Philos Trans A Math Phys Eng Sci. 2025;383(2292):20240232. [CrossRef]

- Ginsburg GS, Phillips KA. Precision Medicine: From Science To Value. Health Aff (Millwood). 2018;37(5):694-701. [CrossRef]

- Avanzato R, Beritelli F, Lombardo A, Ricci C. Lung-DT: an AI-based digital twin framework for monitoring and diagnosing chest health. Sensors (Basel). , 2024; 24(3):958. 1 February. [CrossRef]

- Rouhollahi A, Willi JN, Haltmeier S, Mehrtash A, Straughan R, Javadikasgari H, Brown J, Itoh A, de la Cruz KI, Aikawa E, Edelman ER, Nezami FR. CardioVision: A fully automated deep learning package for medical image segmentation and reconstruction generating digital twins for patients with aortic stenosis. Comput Med Imaging Graph. 2023 Oct;109:102289. [CrossRef]

- Mitek A, Jones D, Newell A, Vitale S. Wearable Devices in Veterinary Health Care. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 2022 Sep;52(5):1087-1098. [CrossRef]

- Zhao X, Tanaka R, Mandour AS, Shimada K, Hamabe L. Remote Vital Sensing in Clinical Veterinary Medicine: A Comprehensive Review of Recent Advances, Accomplishments, Challenges, and Future Perspectives. Animals (Basel). 2025 Apr 3;15(7):1033. [CrossRef]

- Kays R, Crofoot MC, Jetz W, Wikelski M. ECOLOGY. Terrestrial animal track-ing as an eye on life and planet. Science. 2015 Jun 12;348(6240):aaa2478. [CrossRef]

- Yfantidou S, Sermpezis P, Vakali A, Baeza-Yates R. Uncovering bias in personal informatics. Proc ACM Interact Mob Wearable Ubiquitous Technol. 2023;7(3):1-30.

- Gianfrancesco MA, Tamang S, Yazdany J, Schmajuk G. Potential Biases in Machine Learning Algorithms Using Electronic Health Record Data. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(11):1544-1547. [CrossRef]

- Norori N, Hu Q, Aellen FM, Faraci FD, Tzovara A. Addressing bias in big data and AI for health care: A call for open science. Patterns (N Y). 2021;2(10):100347. [CrossRef]

- Weinberger N, Hery D, Mahr D, et al. Beyond the gender data gap: co-creating equitable digital patient twins. Front Digit Health. 2025;7:1584415. [CrossRef]

- Baskett, F. Books: Invisible Women: Exposing Data Bias in a World Designed For Men: Mind the Gap. Br J Gen Pract. 2020;70(694):250. [CrossRef]

- Drummond D, Coulet A. Technical, Ethical, Legal, and Societal Challenges With Digital Twin Systems for the Management of Chronic Diseases in Children and Young People. J Med Internet Res. 2022;24(10):e39698. [CrossRef]

- Popa EO, van Hilten M, Oosterkamp E, et al. The use of digital twins in healthcare: socio-ethical benefits and socio-ethical risks. Life Sci Soc Policy. 2021;17:6. [CrossRef]

- Amann J, Vetter D, Blomberg SN, et al. To explain or not to explain?-Artificial intelligence explainability in clinical decision support systems. PLOS Digit Health. 2022;1(2):e0000016. [CrossRef]

- Herzog C, Wagner B, Lütge C, Jongsma KR. Towards trustworthy medical AI ecosystems – a proposal for supporting responsible innovation practices in AI-based medical innovation. AI & Soc. 2025;40:2119–2139. [CrossRef]

- Boardman, J. A New Kind of Data Science: The Need for Ethical Analytics. 2022. Published and Grey Literature from PhD Candidates. 33. https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/dataphdgreylit/33.

- Canali S, Schiaffonati V, Aliverti A. Challenges and recommendations for wearable devices in digital health: Data quality, interoperability, health equity, fairness. PLOS Digit Health. 2022;1(10):e0000104. [CrossRef]

- Velez FF, Luderer HF, Gerwien R, Parcher B, Mezzio D, Malone DC. Evaluation of the cost-utility of a prescription digital therapeutic for the treatment of opioid use disorder. Postgrad Med. 2021;133(4):421-427. [CrossRef]

- Huh KY, Oh J, Lee S, Yu KS. Clinical Evaluation of Digital Therapeutics: Present and Future. Healthc Inform Res. 2022;28(3):188-197. [CrossRef]

- Thomas L, Hyde C, Mullarkey D, Greenhalgh J, Kalsi D, Ko J. Real-world post-deployment performance of a novel machine learning-based digital health technology for skin lesion assessment and suggestions for post-market surveillance. Front Med (Lausanne). 2023;10:1264846. [CrossRef]

- Sankar BS, Gilliland D, Rincon J, et al. Building an Ethical and Trustworthy Biomedical AI Ecosystem for the Translational and Clinical Integration of Foundation Models. Bioengineering (Basel). 2024;11(10):984. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).