Submitted:

28 July 2025

Posted:

29 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Background and Related Work

2.1. CRISM

2.2. Summary Products for Data Processing

2.3. Unsupervised Machine Learning

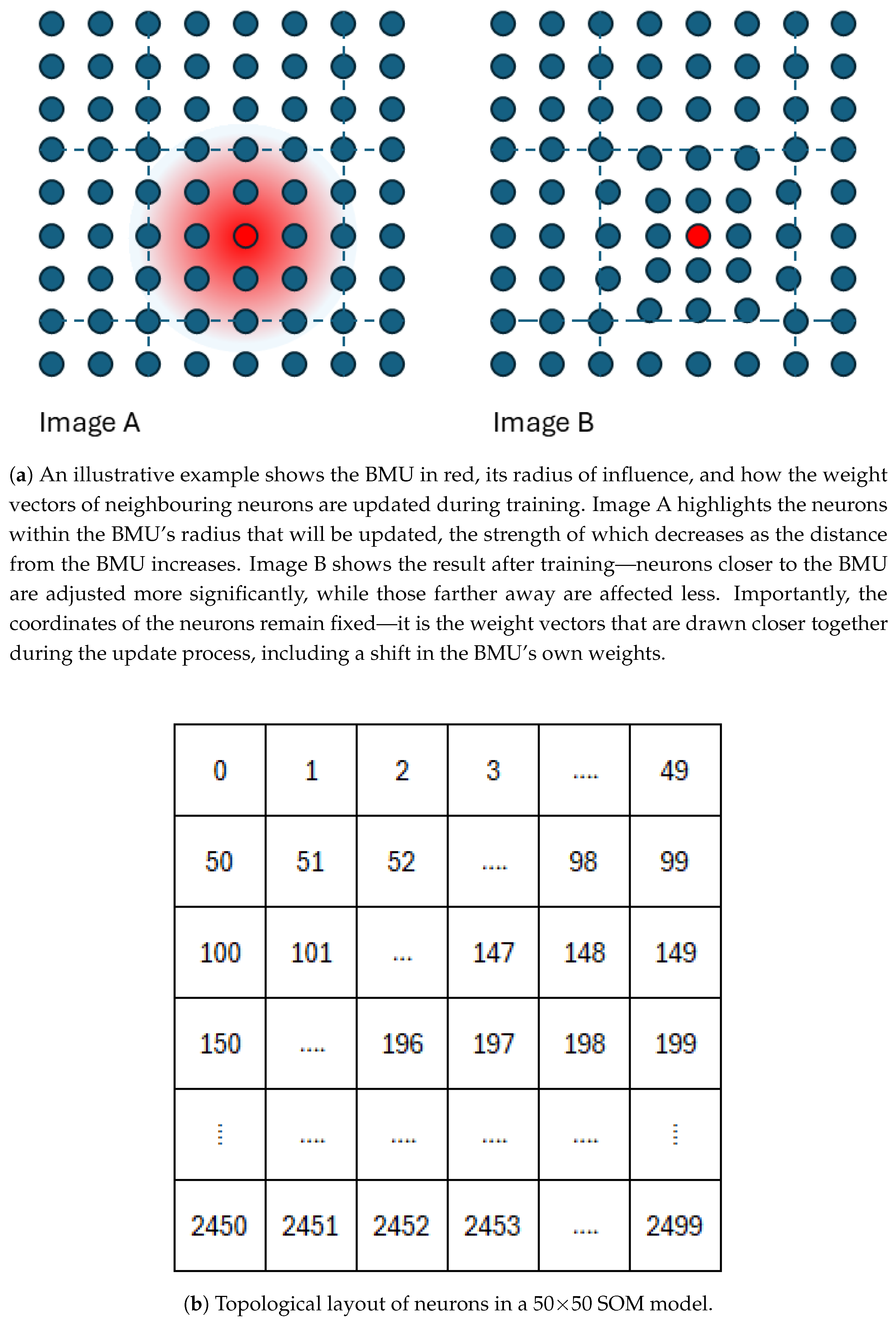

2.3.1. SOM

- High-dimensional Input Handling: A SOM model can process high-dimensional data directly without requiring dimensionality reduction (aside from computational performance considerations). Although SOMs typically use Euclidean distance (which assumes the linearity of the input space), other distance metrics can be adopted.

- Topological Preservation: Unlike traditional clustering algorithms, a SOM model preserves the topological structure of the input space. This is particularly useful in hyperspectral analysis and can reveal distinct and isolated mineral clusters.

- Robustness to Overdimensioning: The SOM’s structured output space enables intuitive interpretation even when the number of neurons exceeds the number of distinct clusters. Over-dimensioning leads to finer topological granularity rather than fragmented or scattered clusters; coherent patterns can be visually observed.

- Representative Abstraction: In large-scale clustering (e.g., summary product vectors into 100 clusters), summarising each group meaningfully can be difficult. Simple averaging of cluster members may blur subtle spectral distinctions. In contrast, SOMs assign each neuron a weight vector that captures the core spectral characteristics of the clustered instances, as well as, to a lesser extent, those of nearby clusters, without the need for post-processing.

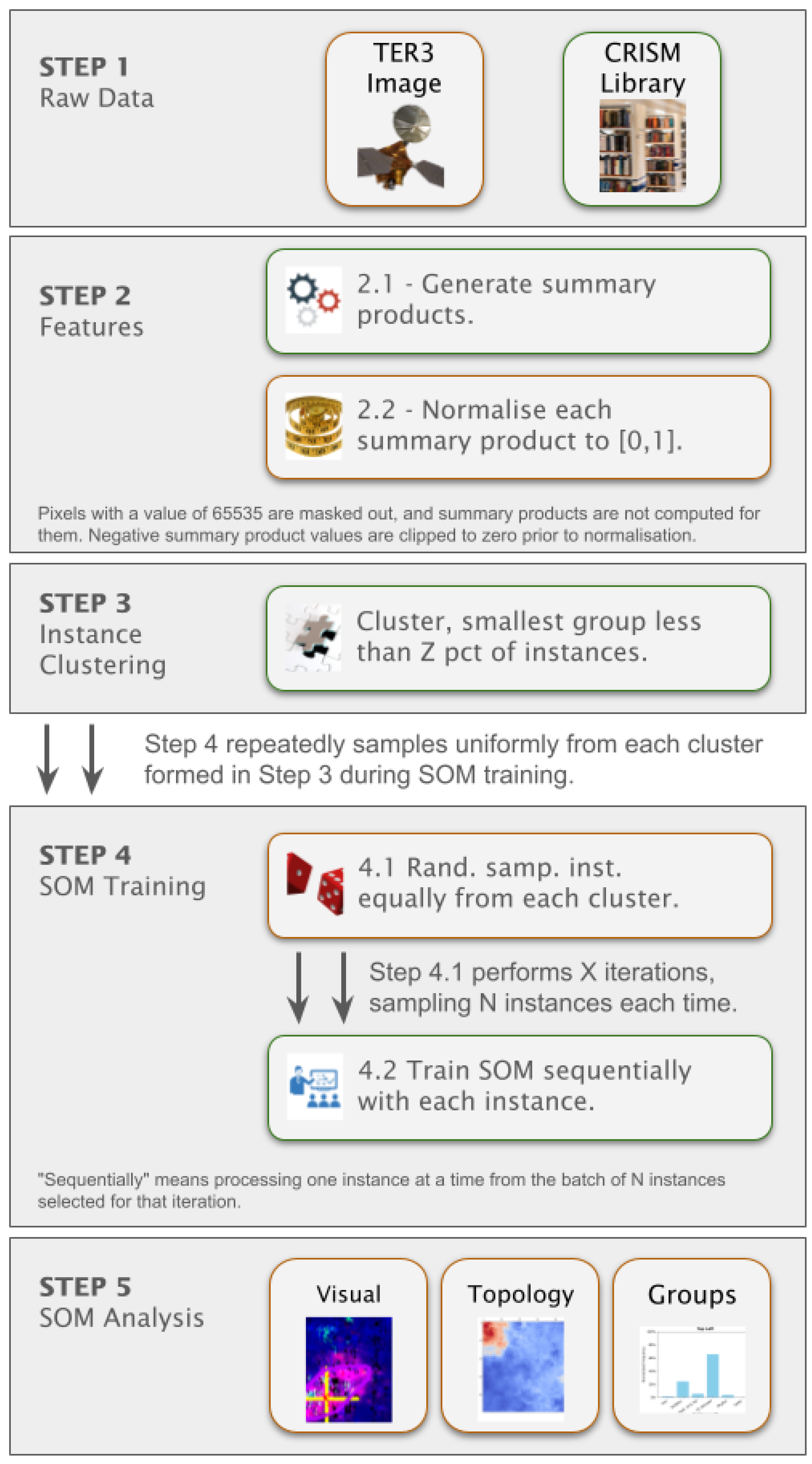

3. Methodology

3.1. Mars Coordinate System

3.2. Data Preprocessing

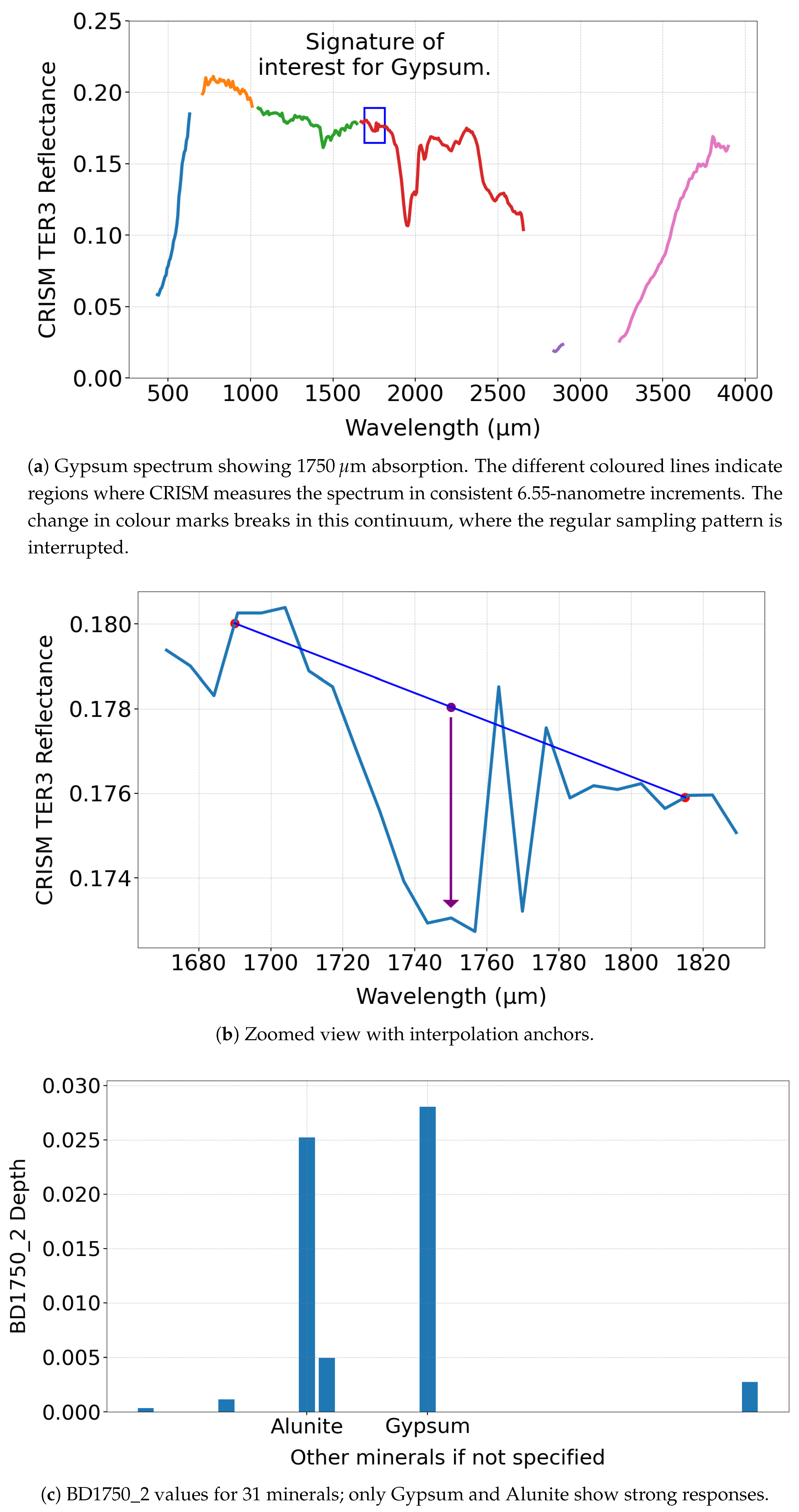

- Summary product recalculation: We use summary products derived from specific spectral absorption features [8] to cluster minerals as summary products are designed to detect key mineral signatures. Although MTRDR images files include these summary products, our analysis identified discrepancies between the values contained within and their intended spectral formulas used to generate them [16,35]. Therefore, we use Targeted Empirical Record - version 3 (TER-3) files, which enable us to recalculate summary products from the original spectral measurements. TER-3 is a specific CRISM image type [35] that consists of un-projected hyperspectral observations that have been corrected for atmospheric and photometric effects for Mars.

- Spectral labelling: We use the MRO CRISM Type Spectra Library to label clusters, which provides reference spectra for each mineral, specifically, we use the Numerator from the library - the source of which is also from a pixel in a TER-3 image - where the mineral has been previously verified [47]. These spectra serve as ground truth references to support the identification of mineral clusters detected by the SOM model. Ideally, each pixel (numerator) would be normalised using a reference pixel (denominator) and the ratio used to calculate summary products. Whilst the library provides a denominator for each reference spectra, we did not adopt this approach due to uncertainty about reliably identifying a reference pixel in each TER-3 image. If done incorrectly, this could complicate comparisons between the summary products calculated from targeted TER-3 image files and library reference spectra. Spectra for each mineral contained within the library is converted into a summary product for direct comparison.

- We mask pixels that have a specific value of 65535 in any frame, as this indicates invalid or missing spectral data. These pixels are excluded from analysis, and summary products are not calculated for them.

- We compute summary products for each pixel from the unmasked pixels.

- We clip any summary product values below zero to zero. Although the formula for summary products does not specify a minimum bound. We refer to BD1750_2 in Equation (1), which can yield negative values, absorption features are inherently positive. This clipping approach is consistent with recommendations in the literature [34].

- We normalise all summary products to a range [0,1] to eliminate dimensional disparities and standardise inputs for the model.

3.3. Unsupervised Machine Learning Framework

- Stage 1- Rough Topological Organisation: In the initial stage, neurons are updated with a high learning rate and a large neighbourhood radius, facilitating a coarse topological structure that guides the model in later stages.

- Stage 2- Refinement: The learning rate progressively decays, and the neighbourhood radius shrinks, enabling the model to fine-tune and converge on subtle distinctions in mineral characteristics.

3.3.1. SOM Implementation

3.3.2. Cluster Labelling

3.3.3. Threshold for Mineral Confidence Levels

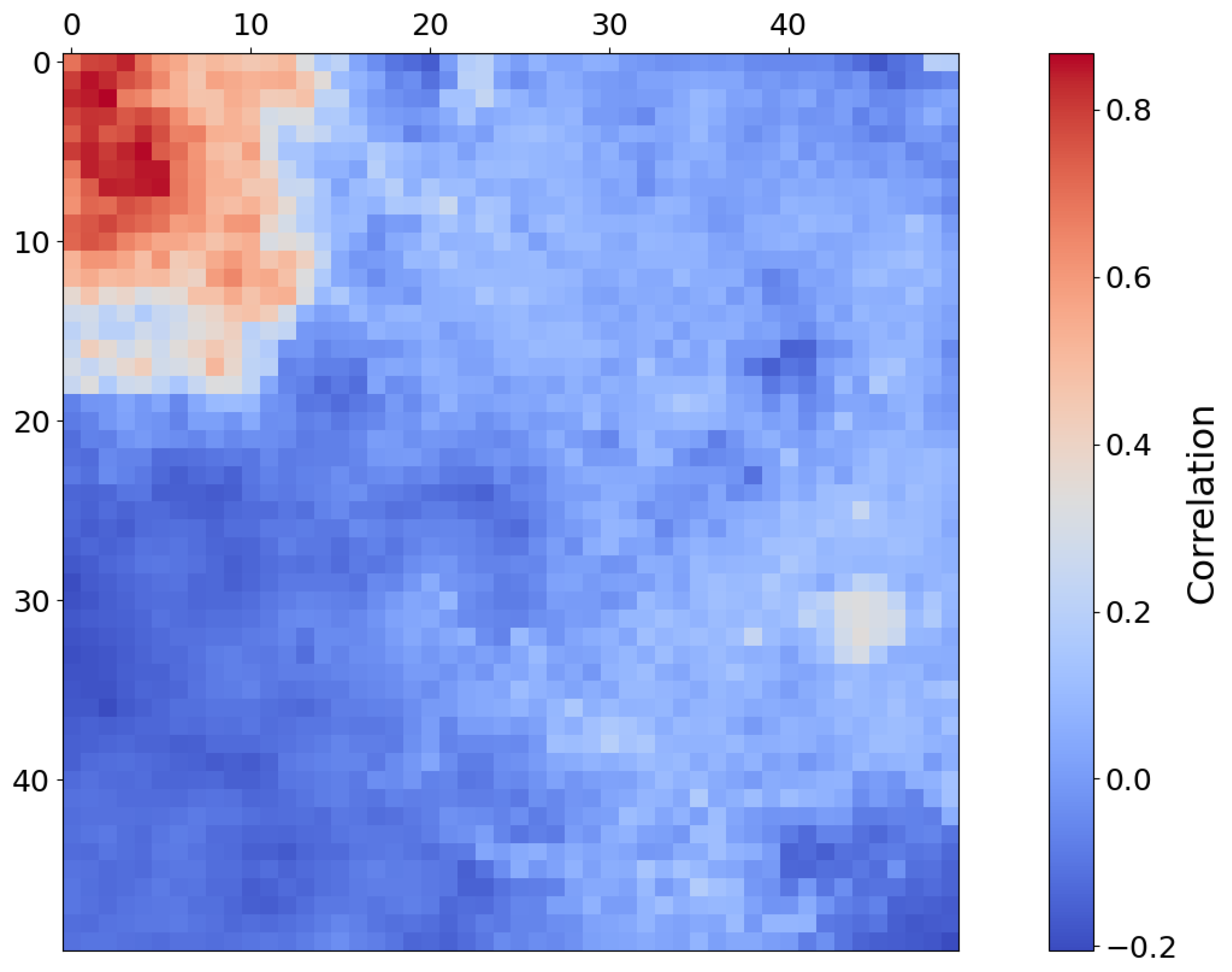

- Correlation Calculation: We calculate the correlation of all 2,500 neurons to each of the 31 mineral reference spectra in the CRISM MRO Type Spectra Library, resulting in 77,500 individual correlation values.

- Global Thresholding: The neurons are considered to have a high correlation to a mineral if their correlation exceeded the 95th percentile of all neurons. The median correlation value was also used as a threshold, with neurons correlating with the median being excluded from further consideration.

-

Z-Score Transformation: For each mineral, the correlation values to each neuron were converted to z-scores (for just that mineral). A neuron was deemed to belong to a mineral if:

- -

- The neuron had a high correlation with the mineral, and its z-score exceeded the mean z-score for that mineral across all neurons (indicating a strong and representative correlation).

- -

- Alternatively, if the mineral’s correlation to the neuron was low, the z-score had to exceed 2 to be considered relevant.

- Rationale for Approach: This method was adapted based on our observations that some minerals appeared to be widely distributed across a target region, while others were highly localised. The approach aimed to capture both scenarios by emphasising stronger correlations for widely distributed minerals and allowing for more flexibility with more isolated minerals.

4. Results

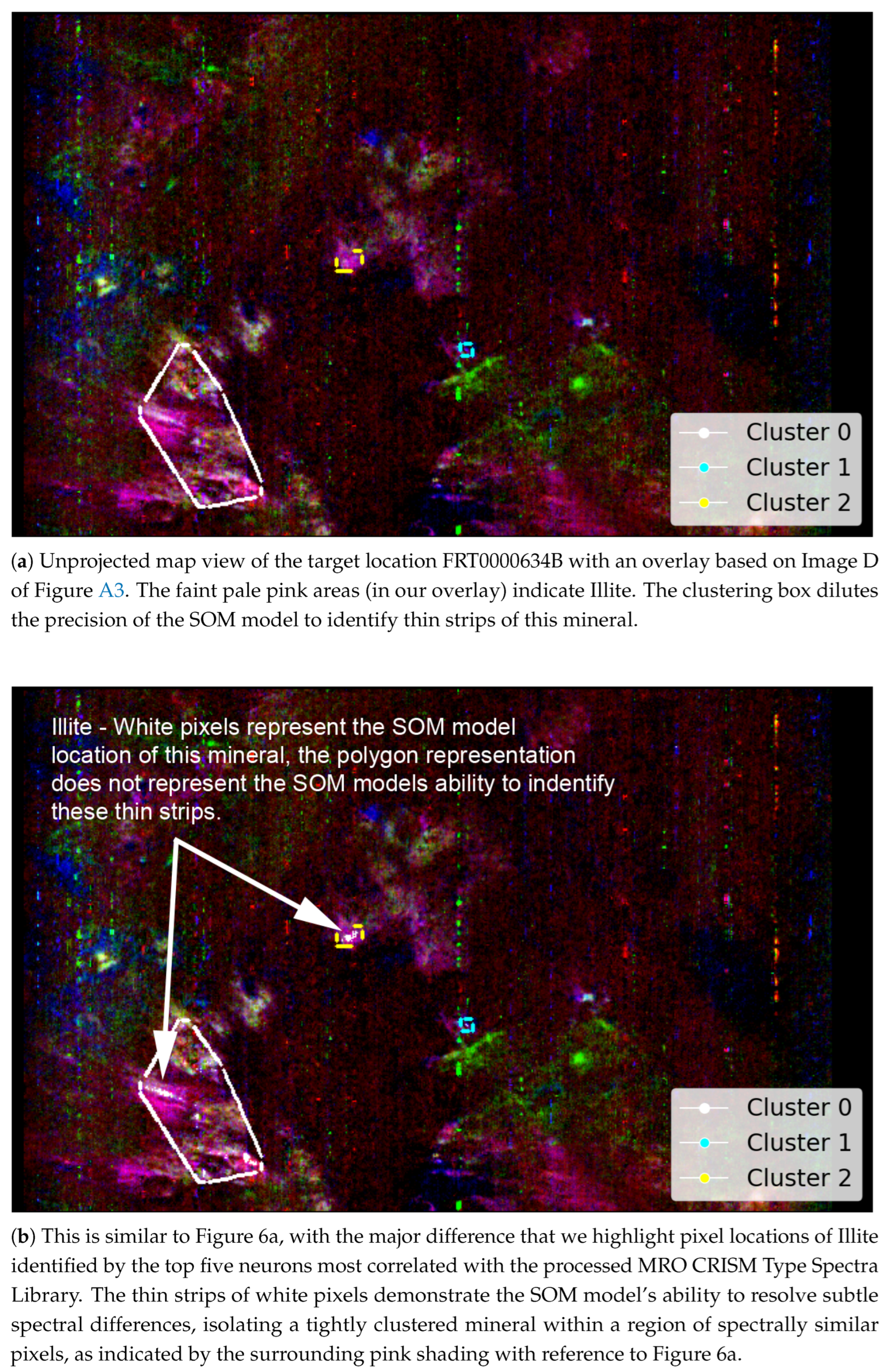

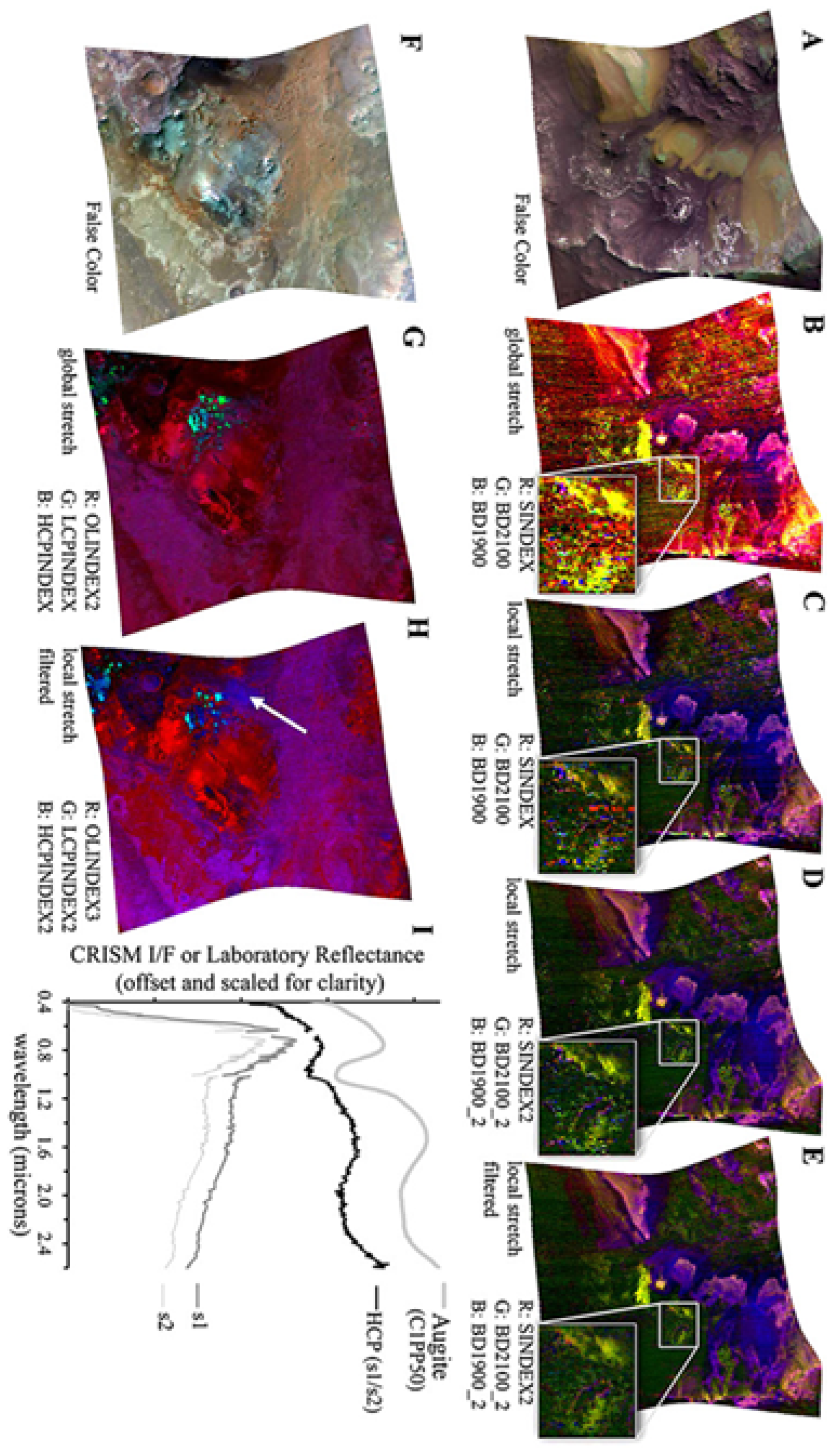

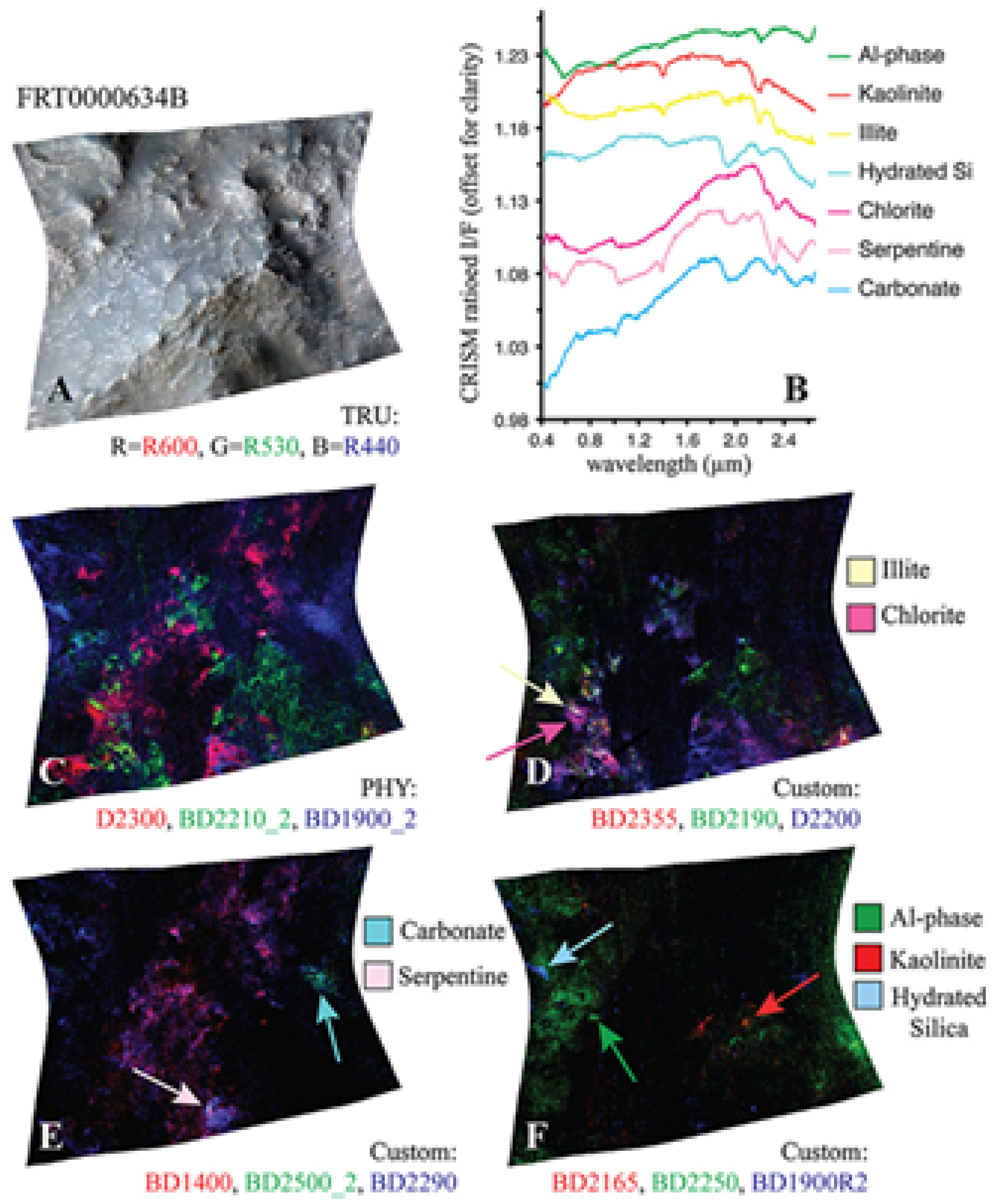

- A visual comparison of the SOM model’s ability to detect the spatial distribution of the mineral Illite with reference to the distribution identified by Viviano et al. [34].

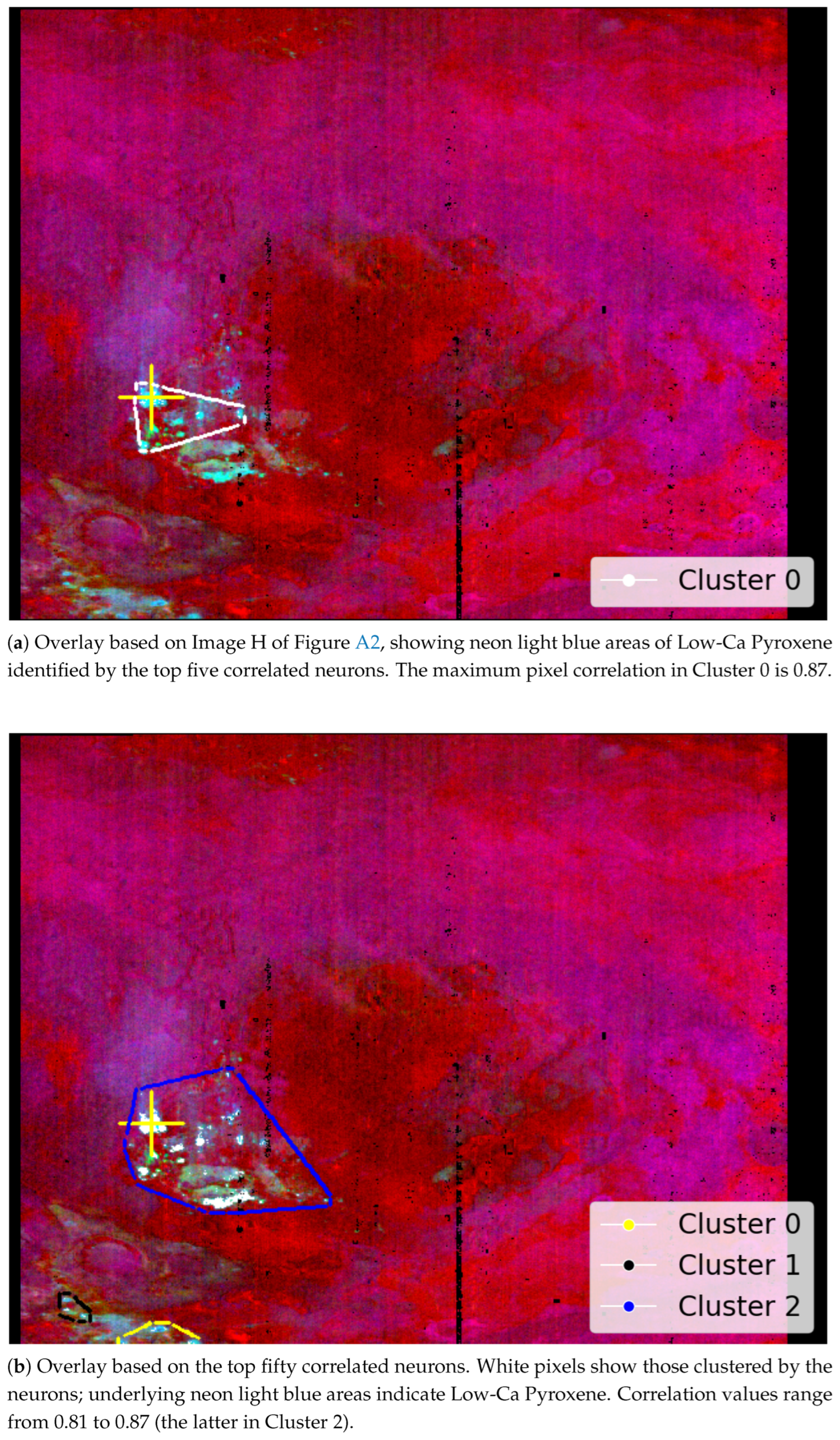

- The SOM model’s ability to detect the specific location of the mineral Low-Ca Pyroxene, as previously identified by [34].

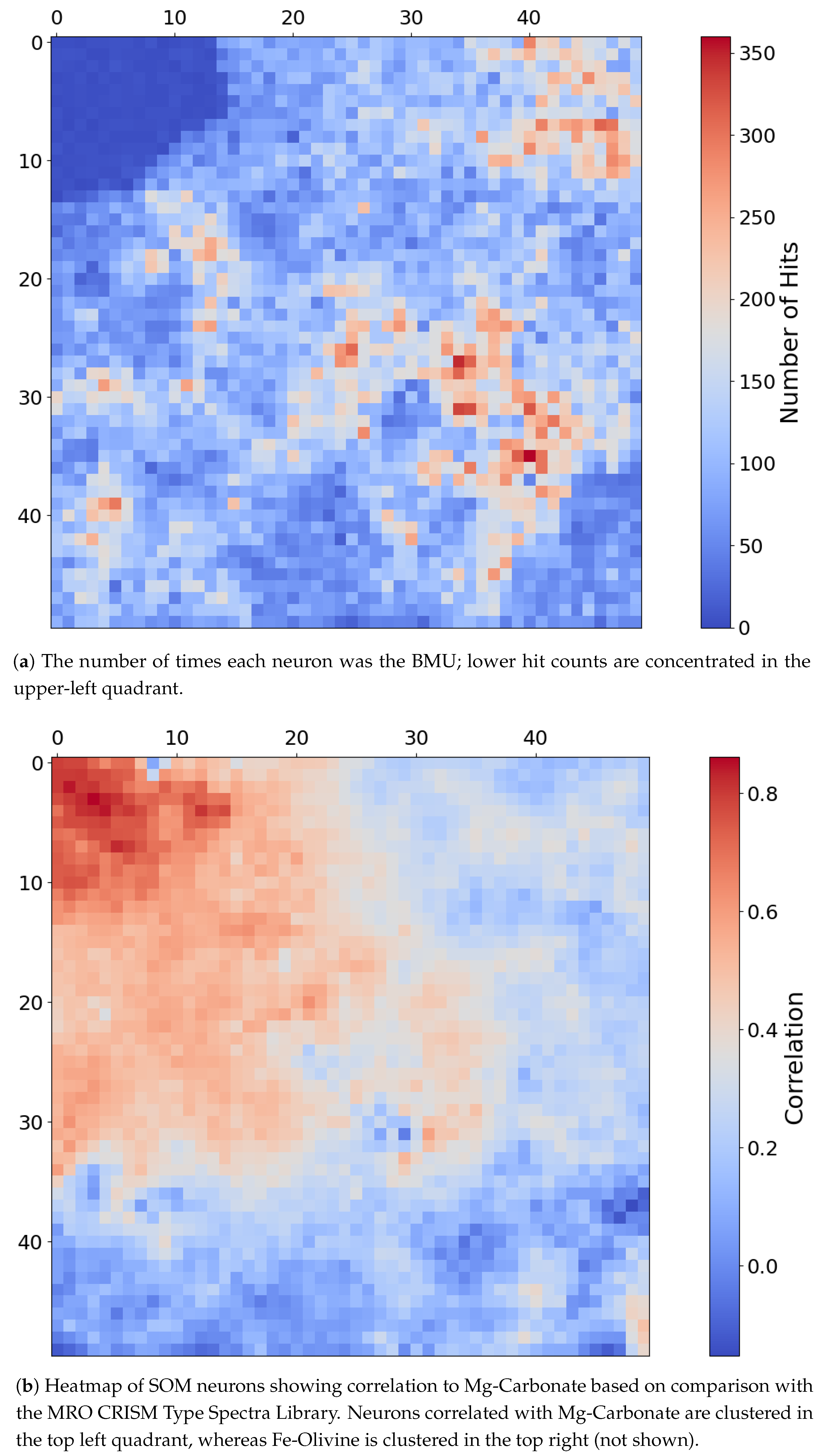

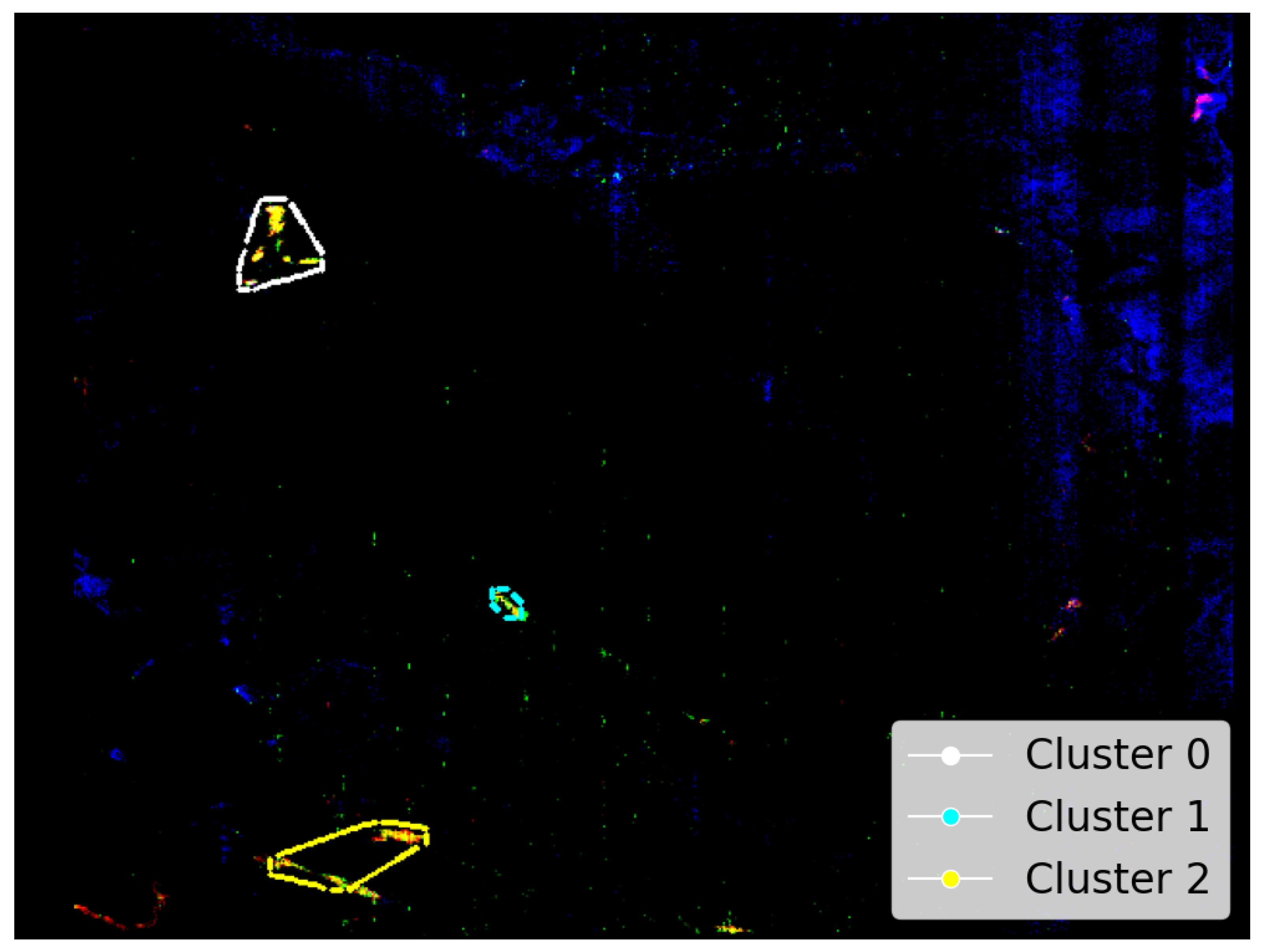

- An application of the SOM model’s topological structure to identify the presence of Mg-Carbonate on Mars in a previously unknown location.

- A qualitative review of the topological organisation of mineral groups within the SOM model neuron grid.

4.1. Mineral Classification

4.2. SOM Model Structure and Mineral Organization

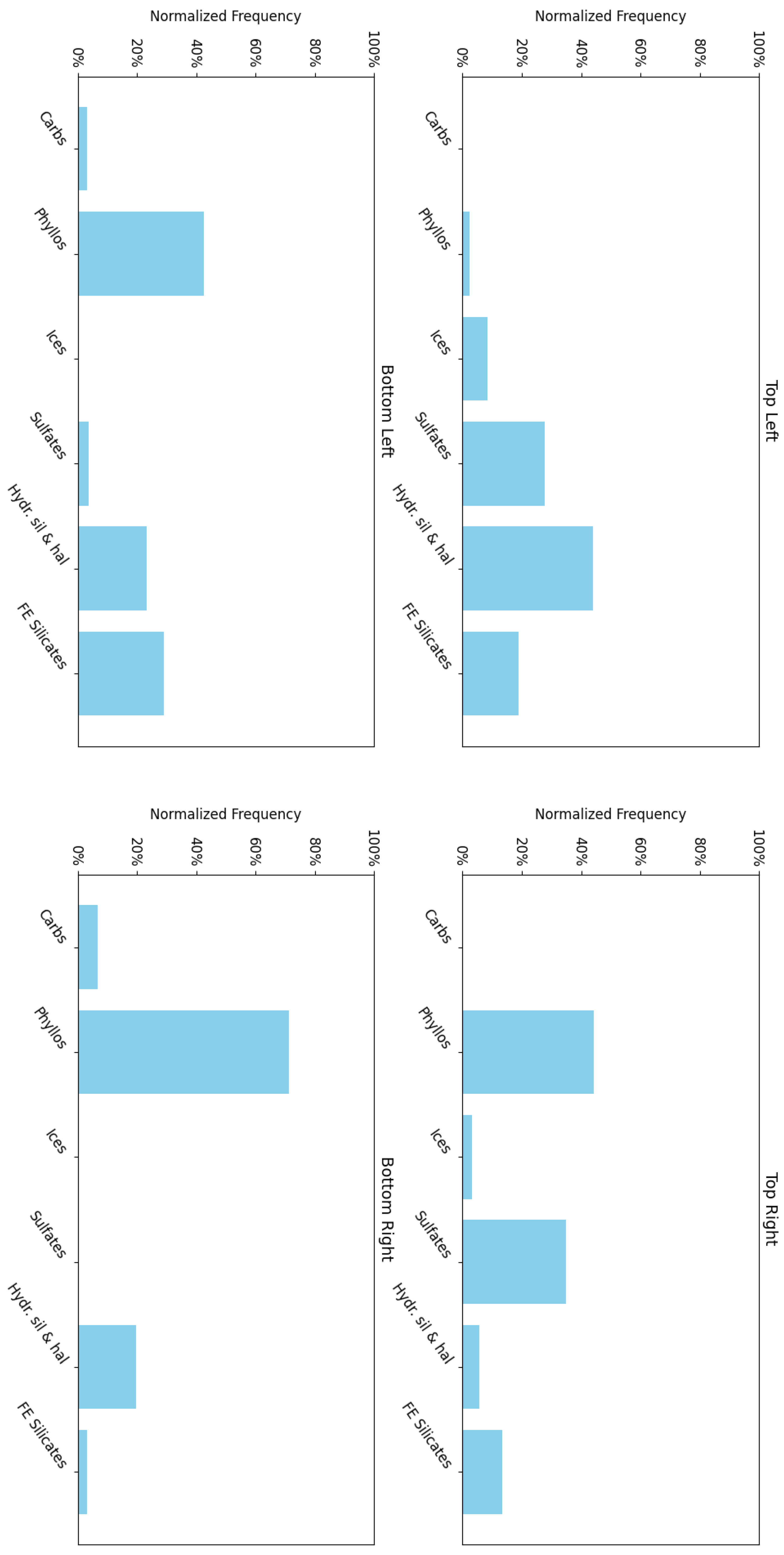

- The top-left corner of Figure 11 is notably sparse in Phyllosilicate minerals, which are primarily mapped to neurons in opposing corners.

- Sulfates and Ices (the latter of which there are only two instances of in the MRO CRISM Type Spectra Library) are more prevalent in the upper regions of the SOM model, with ices absent from the bottom corners.

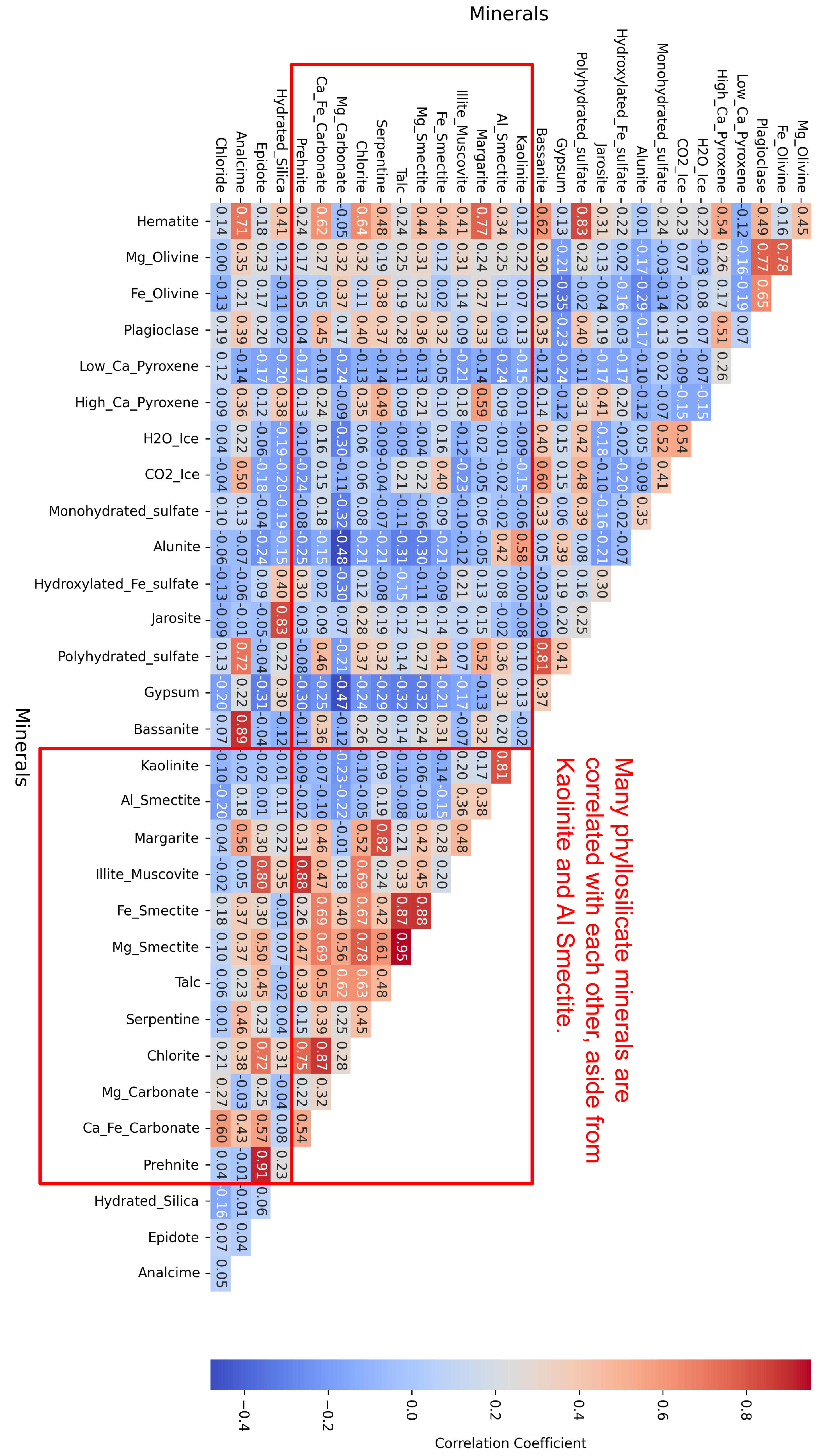

- Phyllosilicates exhibit high intra-group correlation, except for Kaolinite and Al-Smectite, which are mostly negatively correlated with their peers.

- Ices are consistently only correlated with Sulfates.

4.3. K-Means Clustering

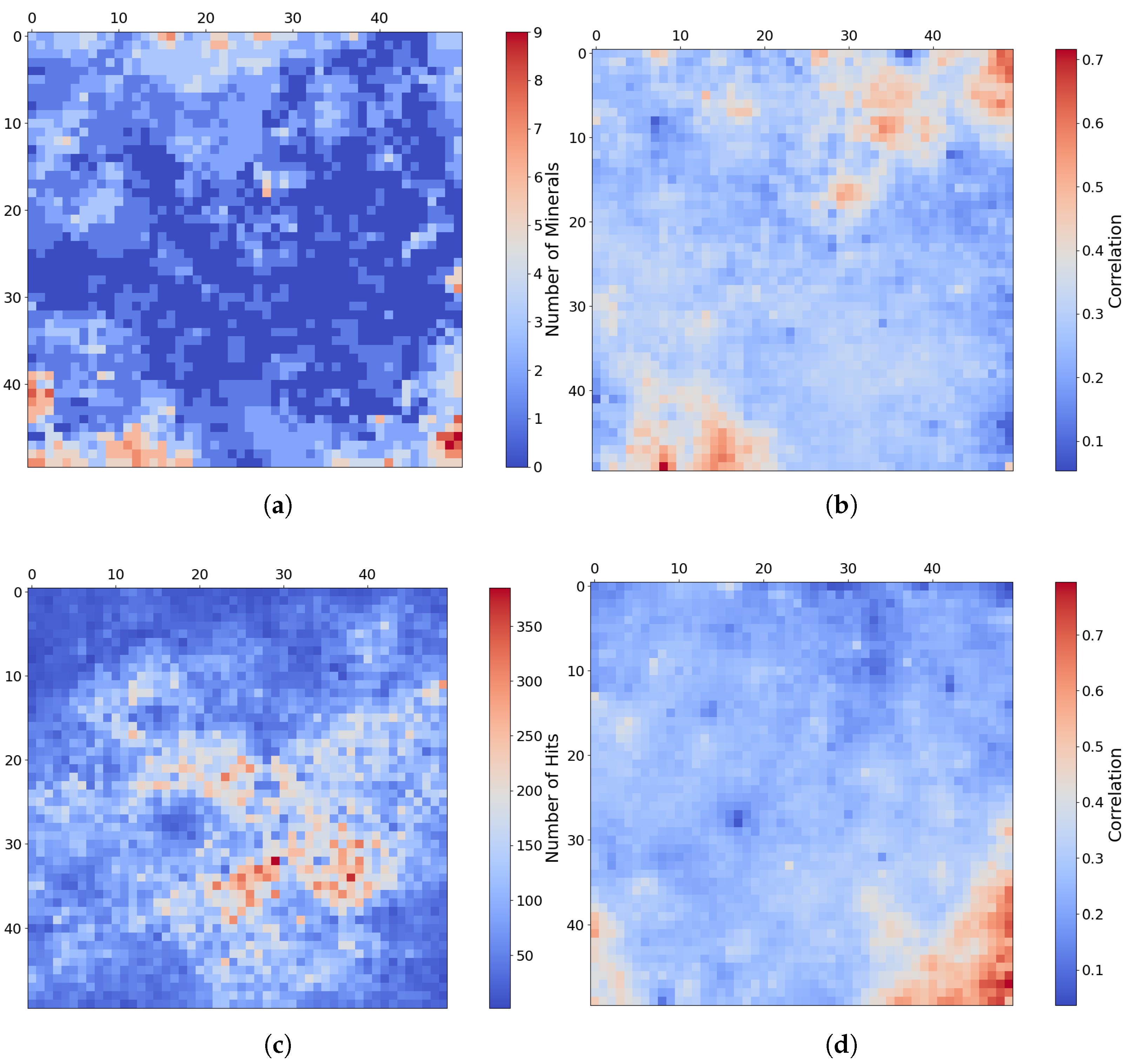

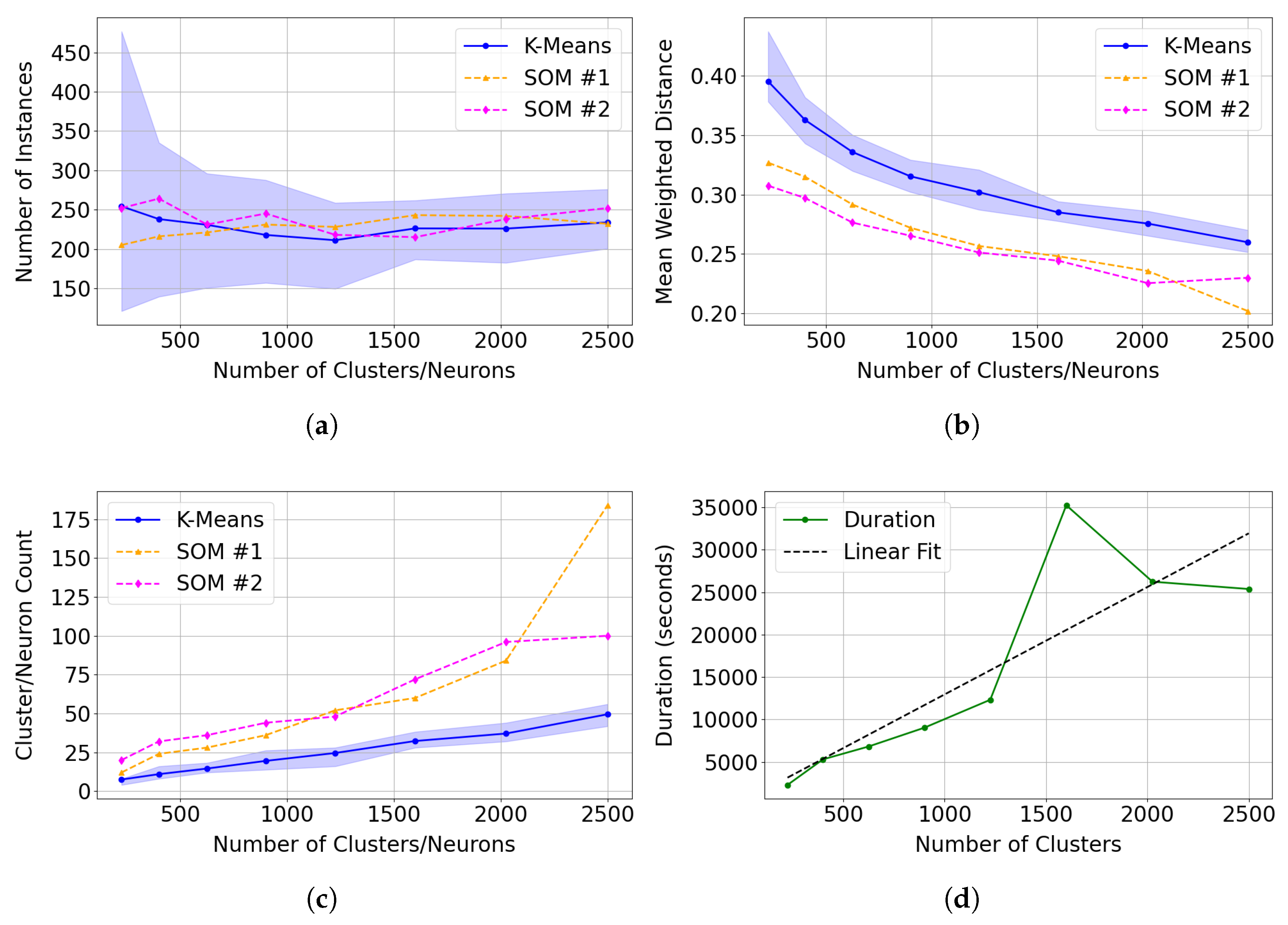

- Demonstrates stable clustering of instances identified as Mg-Carbonate, with both SOM training iterations appearing to show reduced variation in clustering assignments. Notably, the SOM results remain close to the mean and well within the confidence interval generated from 30 independent K-Means trials (see Figure 14(a)).

- Generates tighter clusters, as indicated by a mean weighted distance that is consistently and significantly lower than that of K-Means (see Figure 14(b)).

- Allocates more neurons to represent distinct and unique instances, capturing greater detail (see Figure 14(c)).

5. Discussion

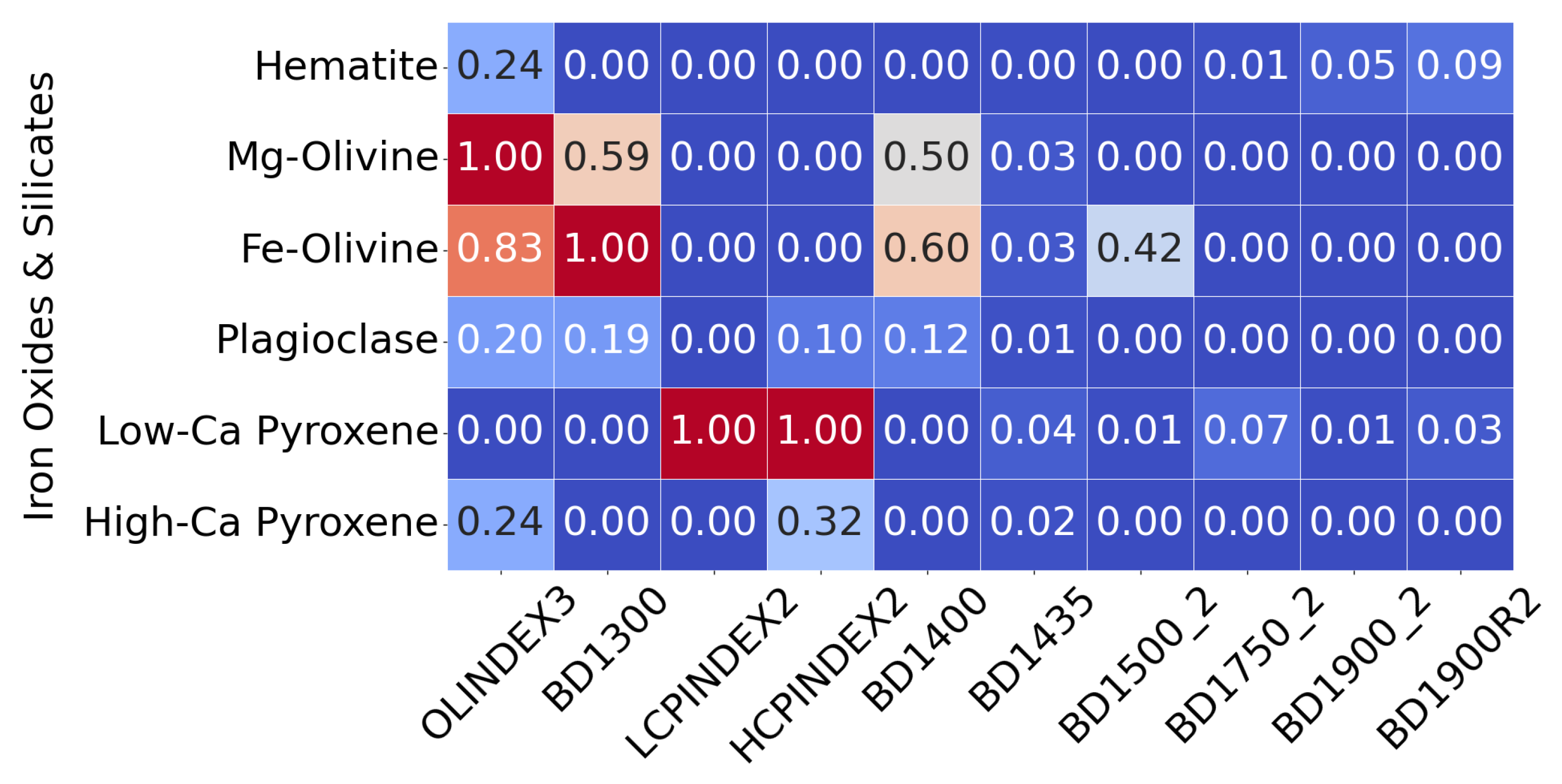

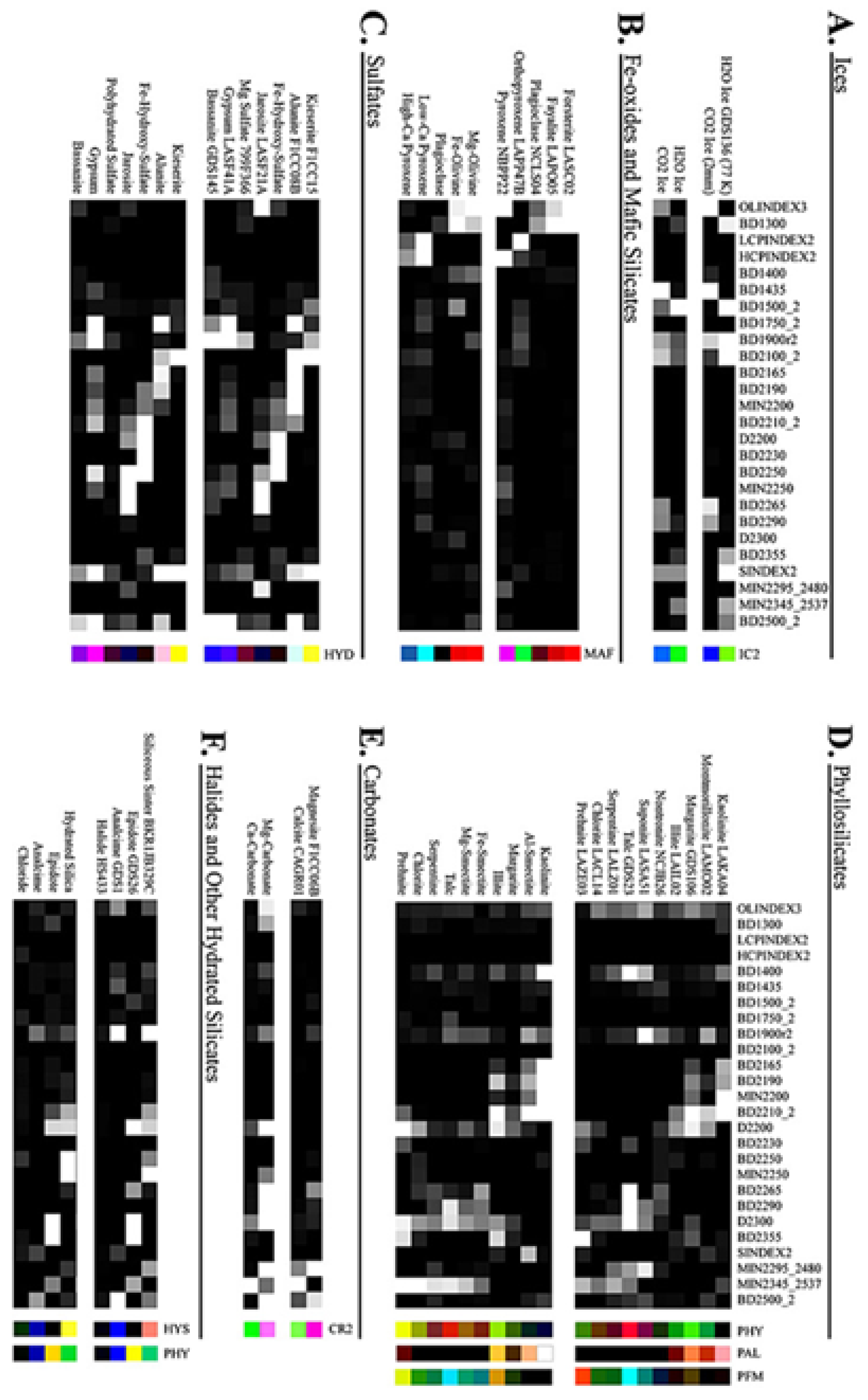

- This study utilised the set of summary products outlined in Figure A1, however significant spectral overlap remains among many minerals, which limits the ability of clustering algorithms to differentiate between compositionally similar but distinct mineral types. While the MTRDR dataset includes approximately 60 summary product bands, we have only validated, corrected and recalculated 29 of these. Expanding the feature set to include additional summary products may improve mineral discrimination, but each new feature must be validated due to the discrepancies identified with precomputed summary products within MTRDR files and the intended spectral features. These discrepancies appear to exist in both directions - MTRDR files contain formula errors when compared to the CRISM DPSIS documentation, while in other cases, the formulas in the CRISM DPSIS do not accurately reflect updated or enhanced outputs found in the MTRDR files [16,35].

- An expert review of the formulae to compute summary products is warranted as current versions rely on conflicting or overlapping definitions from multiple sources, for example, in some instances, the same summary product has a different formula specified in [34] compared to [35]. Although this research addressed several known issues, uncertainty remains whether some summary products accurately capture the intended spectral features in the first instance. This ambiguity risks leading clustering algorithms to identify misleading or spurious patterns, ultimately undermining the reliability of the results.

- Ideally, a machine learning approach to deriving summary products by automatically identifying key spectral features may be a preferred approach compared to expert review. Unlike traditional, expert-driven methods, which are time-consuming, subjective, and may miss complex patterns, machine learning methods should be capable of generating summary products that overcome these shortcomings.

- Normalising hyperspectral data using a representative reference (or "bland") pixel within each target region has the potential to enhance diagnostic absorption features, this technique is widely used in CRISM-based analyses [34,47]. In this study, summary products were derived directly from unnormalised TER-3 hyperspectral data. While this approach simplifies preprocessing, it may reduce the clarity of absorption features and hinder mineral differentiation. Future work should explore automated methods to reliably identify representative bland pixels within each region to facilitate normalisation.

- For each target region, summary product values were scaled locally, i.e., normalised between 0 and 1 based on the minimum and maximum values within each individual target region. While this method is effective for within-region clustering, it introduces inconsistencies when comparing results across multiple regions. For instance, two regions may appear to contain similar mineral signatures when scaled locally, but global scaling could reveal significant differences. Additionally, the color representation of mineral associations, as per Figure 9 in [34], becomes inconsistent across regions due to the relative nature of local scaling. A more rigorous approach would involve applying global normalisation using consistent reference values, though this would require the construction of a comprehensive global database of summary product statistics. Summary products derived from hyperspectral data from the MRO CRISM Type Spectra Library should be scaled according to the same global limits.

- Our results show that the SOM model organises into stable topological patterns, often clustering similar mineral types in adjacent nodes. This raises the possibility of accelerating SOM model training by initialising weights based on an informed prior structure. Further investigation into pre-initialisation techniques may improve training efficiency and output quality.

- A promising avenue for future work involves training a global SOM model exclusively on verified mineral spectra, independent of any specific region. This "Master SOM model" could then be deployed to new Martian sites for rapid classification and mapping. Such a model would enhance consistency, reduce preprocessing time, and allow for more direct comparisons between studies and across target areas. Due to the global nature of this approach, normalised hyperspectral data would be required before deriving summary products.

- A critical challenge in planetary mineralogy is the identification of pixels with spectral profiles that do not closely match any known hyperspectral samples. Developing a systematic approach to detect and flag distinct but unknown spectra signatures might be important for discovering new or unknown mineral types.

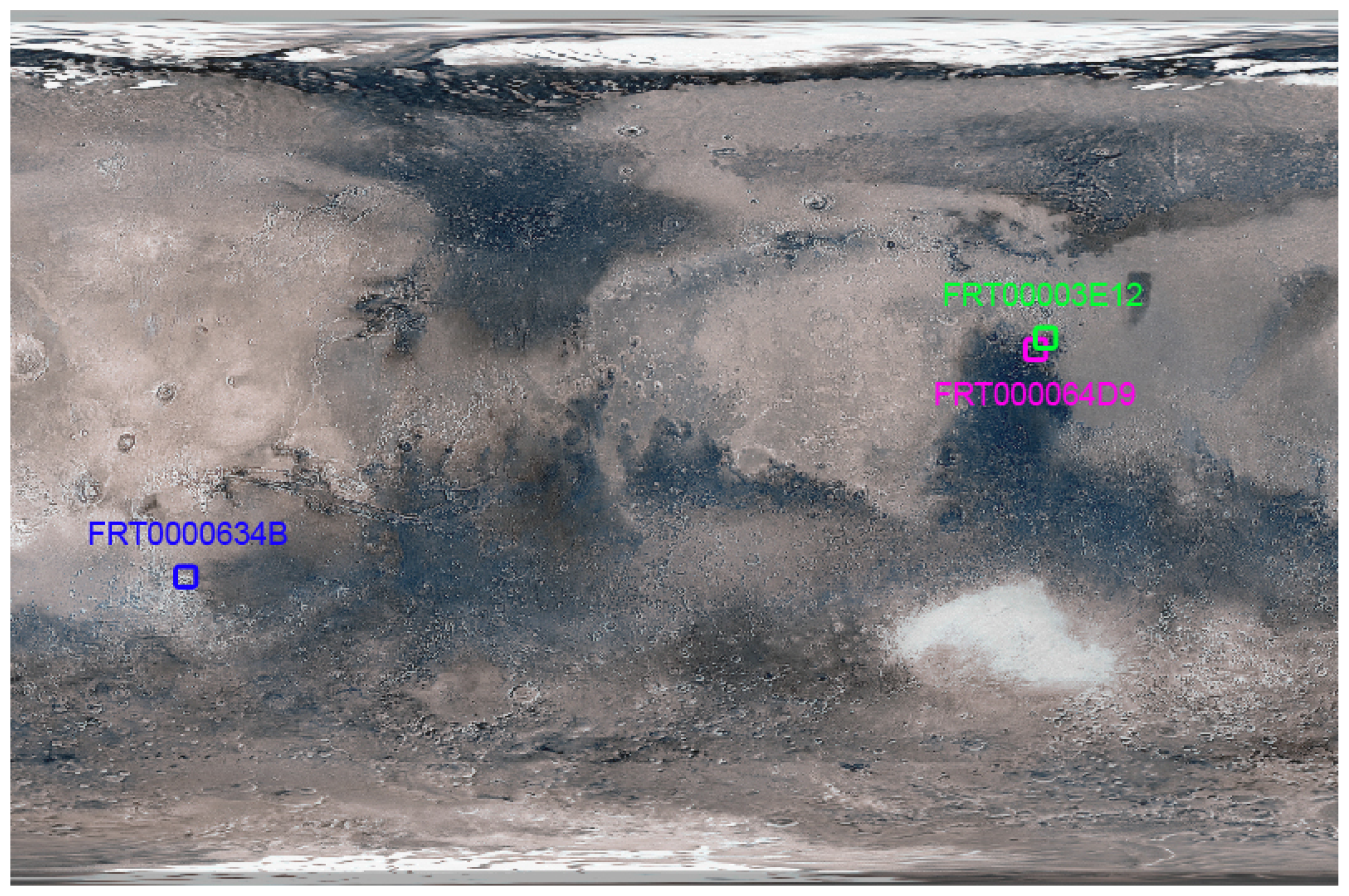

| Mineral | Figure | Target Region | Original X | Original Y | Rotated |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illite | 6a | FRT0000634B | NA | NA | YES |

| Illite | 6b | FRT0000634B | NA | NA | YES |

| Low-Ca Pyroxene | 7a | FRT000064D9 | 174 | 528 | YES |

| Low-Ca Pyroxene | 7b | FRT000064D9 | 174 | 528 | YES |

| Mg-Carbonate | 10 | FRT00003E12 | NA | NA | NO |

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

- Target region FRT00003E12 - https://zenodo.org/records/16397494

- Target region FRT000064D9 - https://zenodo.org/records/16397520

- Target region FRT0000634B - https://zenodo.org/records/16397583

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BMU | Best Matching Unit |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Networks |

| CRISM | Compact Reconnaissance Imaging Spectrometer for Mars |

| DBSCAN | Density-Based Spatial Clustering of Applications with Noise |

| DPSIS | Data Product Summary Image Specification |

| EDR | Experiment Data Record |

| ICA | Independent Component Analysis |

| LMM | Linear Mixing Models |

| MNF | Minimum Noise Fraction |

| MRO | Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter |

| MTRDR | Map-Projected Targeted Reduced Data Record (CRISM) |

| MWD | Mean Weighted Distance |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| SOM | Self-Organising Map |

| TER | Targeted Empirical Record |

| TER-3 | Targeted Empirical Record version 3 |

| TRDR | Targeted Reduced Data Record |

| VNIR | Visible-to-Near-Infrared |

Appendix A. Visualise Mineral Locations

Appendix B. Summary Products

| OLINDEX3 | BD1300 | LCPINDEX2 | HCPINDEX2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| BD1400 | BD1435 | BD1500_2 | BD1750_2 |

| BD1900_2 | BD1900R2 | BD2100_2 | BD2165 |

| BD2190 | MIN2200 | BD2210_2 | D2200 |

| BD2230 | BD2250 | MIN2250 | BD2265 |

| BD2290 | D2300 | BD2355 | SINDEX2 |

| MIN2295_2480 | MIN2345_2537 | BD2500_2 | CINDEX2 |

| R3920 |

- OLINDEX3 - The following kernel widths are used R1210:7, R1250:7, R1263:7, R1276:7, R1330:7 anchored at R1750:7 and R1862:7. The parameter is calculated as 0.1 × RB1210 + 0.1 × RB1250 + 0.2 × RB1263 + 0.2 × RB1276 + 0.4 × RB1330.

- HCPINDEX2 - The anchor points are R1690:7 and R2530:7, the parameter is calculated as 0.1 × RB2120 + 0.1 × RB2140 + 0.15 × RB2230 + 0.3 × RB2250 + 0.2 × RB2430 + 0.15 × RB2460

- BD1900R2 - A kernel width of 5 is used for the anchor bands R1850 and R2060.

- BD2100_2 - The kernel width of R2250:3 was used in place of R2250:5.

- MIN2200 - The kernel width of R2210:3 is used in place of R2120:3

- BD2230 - The kernel width R2235:3 is used in place of R2230:3

- BD2265 - The kernel width R2340:5 is used in place of R2295:5.

- R3920 is not specifically a summary product but is recommended by [34] for the IC2 Browse Product and was calculated using a kernel width of 5.

Appendix C. SOM Updates

Appendix D. Data

Appendix D.1. Download CRISM TER-3 Image Files for a Target Region

- In Step 1, select TER as the product type.

- In Step 2, define the target region by entering the appropriate Product ID such as FRT00003E12* for target region FRT00003E12.

- Review the search results.

-

Download all files containing "if" in the file name such asfrt0000cbe5_07_if166j_ter3.img.

- Consolidate all downloaded TER-3 files into a single folder. There should be an img (500+ mb), lbl and hdr file in the same folder.

-

Open the script CRISM_Spectral_Conversion.py located in theCRISM_Spectral_Conversion folder.

- Specify the path to the TER-3 .img file and set the desired output directory in the script.

- Execute the script.

Appendix E. SOM

- Open the script som_training.py located in the SOM_Training folder.

- Set the path to the .h5 file which contains preprocessed summary products for the target region..

- Configure the SOM training parameters as necessary.

- Run the script to train the SOM.

Appendix F. Visualise Mineral Locations

- Open the script Layer_Visuals.py located in the SOM_Analysis folder.

- Specify the relevant data sources (including the original TER-3 image file - required for False views), which should be familiar from previous steps.

- Under the section Identify Spatial Distribution of a Specific Mineral, configure the settings for your analysis.

- The output will be a false-color or custom image displaying the identified spatial distribution of the nominated mineral on the Martian surface and target pixel location if you specify such a target.

Appendix F.1. SOM Hierarchical Analysis

- Open the script SOM_analysis.py located in the SOM_Analysis folder.

- Specify the relevant data sources from the previous steps (excluding the original TER-3 image file and summary product outputs contained in the h5 file).

- Run the script to perform a comprehensive topological analysis of the SOM model.

Appendix F.2. K-Means Comparison

- Ensure the SOM model is trained before running this process, as the inputs reshaped_data_loc and reshaped_locations_loc are generated during the SOM training.

- Open the script kmeans.py located in the KMeans folder.

- Specify the relevant data locations and mineral information.

- Run the script to perform the KMeans comparison.

References

- NASA. Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, 2025. Accessed: 2025-06-14.

- Li, S.; Song, W.; Fang, L.; Chen, Y.; Ghamisi, P.; Benediktsson, J.A. Deep Learning for Hyperspectral Image Classification: An Overview. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2019, 57, 6690–6709. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Zhou, X.; Xi, B.; Li, J.; Kang, J.; Tang, S.; Chen, Z.; Hong, W. Diverse-Region Hyperspectral Image Classification via Superpixelwise Graph Convolution Technique. Remote. Sens. 2022, 14, 2907. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Hao, Y.; Liu, Q.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, M.; Xiao, L. Deep Learning for Hyperspectral Image Classification: A Critical Evaluation via Mutation Testing. Remote. Sens. 2024, 16, 4695. [CrossRef]

- Team, C. CRISM Targeted Empirical Record (TER) Data Products Released, 2016. Accessed: 2025-05-21.

- Ehlmann, B.L.; Edwards, C.S. Mineralogy of the Martian surface. Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences 2014, 42, 291–315.

- Wu, X.; Mustard, J.; Tarnas, J.; Zhang, X.; Das, E.; Liu, Y. Imaging Mars analog minerals' reflectance spectra and testing mineral detection algorithms. Icarus 2021, 369. [CrossRef]

- Pelkey, S.M.; Mustard, J.F.; Murchie, S.; Clancy, R.T.; Wolff, M.; Smith, M.; Milliken, R.; Bibring, J.; Gendrin, A.; Poulet, F.; et al. CRISM multispectral summary products: Parameterizing mineral diversity on Mars from reflectance. J. Geophys. Res. 2007, 112. [CrossRef]

- Ke, T.; Zhong, Y.; Song, M.; Wang, X.; Zhang, L. Mineral detection based on hyperspectral remote sensing imagery on Mars: From detection methods to fine mapping. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote. Sens. 2024, 218, 761–780. [CrossRef]

- Pieters, C.M.; Boardman, J.; Buratti, B.; Chatterjee, A.; Clark, R.; Glavich, T.; Green, R.; Head III, J.; Isaacson, P.; Malaret, E.; et al. The Moon mineralogy mapper (M3) on chandrayaan-1. Current Science 2009, pp. 500–505.

- Li, S.; Moriarty III, D.P.; Pieters, C.M.; Klima, R.L.; Dapremont, A.M. A controlled mosaic of moon mineralogy mapper (M3) reflectance data in the lunar polar regions for understanding the mineralogy and water of the Artemis exploration zone. Icarus 2025, p. 116668.

- NASA. Artemis – Humans in Space. https://www.nasa.gov/humans-in-space/artemis/, 2025. Accessed: 2025-07-22.

- Bedini, E. The use of hyperspectral remote sensing for mineral exploration: a review. J. Hyperspectral Remote. Sens. 2017, 7, 189–211. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, M.; Walter, M.R. Application of Hyperspectral Infrared Analysis of Hydrothermal Alteration on Earth and Mars. Astrobiology 2002, 2, 335–351. [CrossRef]

- Gao, A.F.; Rasmussen, B.; Kulits, P.; Scheller, E.L.; Greenberger, R.; Ehlmann, B.L. Generalized unsupervised clustering of hyperspectral images of geological targets in the near infrared. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2021, pp. 4294–4303.

- Not Applicable. Calculation of BD1900_2 in MTRDR data. https://geoweb.rsl.wustl.edu/community/index.php?/topic/3761-calculation-of-bd1900_2-in-mtrdr-data/, Not Applicable. Accessed: 2025-05-05.

- Shirmard, H.; Farahbakhsh, E.; Müller, R.D.; Chandra, R. A review of machine learning in processing remote sensing data for mineral exploration. Remote. Sens. Environ. 2022, 268. [CrossRef]

- Shirmard, H.; Farahbakhsh, E.; Heidari, E.; Pour, A.B.; Pradhan, B.; Müller, D.; Chandra, R. A Comparative Study of Convolutional Neural Networks and Conventional Machine Learning Models for Lithological Mapping Using Remote Sensing Data. Remote. Sens. 2022, 14, 819. [CrossRef]

- Peyghambari, S.; Zhang, Y. Hyperspectral remote sensing in lithological mapping, mineral exploration, and environmental geology: an updated review. J. Appl. Remote. Sens. 2021, 15, 031501. [CrossRef]

- Yoldi, Z.; Pommerol, A.; Poch, O.; Thomas, N. Reflectance study of ice and Mars soil simulant associations–I. H2O ice. Icarus 2021, 358, 114169.

- Wellington, D.; Bell III, J. Patterns of surface albedo changes from Mars reconnaissance orbiter Mars color imager (MARCI) observations. Icarus 2020, 349, 113766.

- Ma, Y.; Chen, S.; Ermon, S.; Lobell, D.B. Transfer learning in environmental remote sensing. Remote. Sens. Environ. 2023, 301. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Gao, P.; Dong, H.; Zhuang, Y.; Wang, G.; Zhang, W.; Chen, H. Consecutive Pre-Training: A Knowledge Transfer Learning Strategy with Relevant Unlabeled Data for Remote Sensing Domain. Remote. Sens. 2022, 14, 5675. [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, P.; Skupin, A. Self-organising maps: Applications in geographic information science; John Wiley & Sons, 2008.

- Vesanto, J.; Alhoniemi, E. Clustering of the self-organizing map. IEEE Transactions on neural networks 2000, 11, 586–600.

- Danielsen, A.S.; Johansen, T.A.; Garrett, J.L. Self-Organizing Maps for Clustering Hyperspectral Images On-Board a CubeSat. Remote. Sens. 2021, 13, 4174. [CrossRef]

- Iranzad, A. Hyperspectral Mineral Identification using SVM and SOM 2013.

- Raatikainen, M.; Sarala, P.; Ranta, J.-P. Self-organizing map modelling and prospectivity mapping of surface geochemical data in Au and multi-metal mineral exploration: example from northern Finland. Geochem. Explor. Environ. Anal. 2025, 25. [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wang, Y.; Wen, S.; Zhang, S.; Zhu, K.; Liu, J. Comprehensive Evaluation of the Lunar South Pole Landing Sites Using Self-Organizing Maps for Scientific and Engineering Purposes. Remote. Sens. 2025, 17, 1579. [CrossRef]

- Murchie, S.; Arvidson, R.; Bedini, P.; Beisser, K.; Bibring, J.; Bishop, J.; Boldt, J.; Cavender, P.; Choo, T.; Clancy, R.T.; et al. Compact Reconnaissance Imaging Spectrometer for Mars (CRISM) on Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO). J. Geophys. Res. Planets 2007, 112. [CrossRef]

- Seelos, F.P.; Seelos, K.D.; Murchie, S.L.; Novak, M.A.M.; Hash, C.D.; Morgan, M.F.; Arvidson, R.E.; Aiello, J.; Bibring, J.-P.; Bishop, J.L.; et al. The CRISM investigation in Mars orbit: Overview, history, and delivered data products. Icarus 2023, 419. [CrossRef]

- Parente, M.; McGuire, P.C.; Bishop, J.L.; Murchie, S.L. Analysis of the effects of spectral mixture resolution on the detection of phyllosilicates on Mars using Mars Express OMEGA and Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter CRISM data. Planetary and Space Science 2008, 56, 1009–1020.

- Alemanno, G. Spectral Parameters, Solar System Planets. In Encyclopedia of Astrobiology; Springer, 2023; pp. 2814–2815.

- Viviano, C.E.; Seelos, F.P.; Murchie, S.L.; Kahn, E.G.; Seelos, K.D.; Taylor, H.W.; Taylor, K.; Ehlmann, B.L.; Wiseman, S.M.; Mustard, J.F.; et al. Revised CRISM spectral parameters and summary products based on the currently detected mineral diversity on Mars. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 2014, 119, 1403–1431. [CrossRef]

- Murchie, S.; Stein, T.; Ward, J. Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter: CRISM Data Product Software Interface Specification, Version 1.3.7.7. Technical report, PDS Geosciences Node, Washington University in St. Louis and Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, 2024. Accessed: 2025-05-05.

- Barve, S.; Webster, J.M.; Chandra, R. Reef-Insight: A Framework for Reef Habitat Mapping with Clustering Methods Using Remote Sensing. Information 2023, 14, 373. [CrossRef]

- Wan, S.; Wang, Y.-P. The Comparison of Density-Based Clustering Approach among Different Machine Learning Models on Paddy Rice Image Classification of Multispectral and Hyperspectral Image Data. Agriculture 2020, 10, 465. [CrossRef]

- Keshava, N.; Mustard, J.F. Spectral unmixing. IEEE Signal Processing Magazine 2002, 19, 44–57.

- Hong, D.; Yokoya, N.; Chanussot, J.; Zhu, X.X. An Augmented Linear Mixing Model to Address Spectral Variability for Hyperspectral Unmixing. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2019, 28, 1923–1938. [CrossRef]

- Haijen, X.; Koirala, B.; Tao, X.; Scheunders, P. A Two-step Linear Mixing Model for Unmixing under Hyperspectral Variability. arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.17212 2025.

- Zou, S.; Zare, A. Hyperspectral unmixing with endmember variability using Partial Membership Latent Dirichlet Allocation. 2017 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP). LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, COUNTRYDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 6200–6204.

- Zhang, W.; Wang, J.; Jin, D.; Oreopoulos, L.; Zhang, Z. A Deterministic Self-Organizing Map Approach and its Application on Satellite Data based Cloud Type Classification. 2018 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (Big Data). LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, USADATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 2027–2034.

- Jayashree, S.; Maya, K.V.; Indira, K.; Dinesh, P.A. Self Organizing Map based Land Cover Clustering for Decision-Level Jaccard Index and Block Activity based Pan-Sharpened Images. J. Indian Soc. Remote. Sens. 2024, 53, 549–569. [CrossRef]

- Cracknell, M.; Reading, A.; de Caritat, P. Multiple influences on regolith characteristics from continental-scale geophysical and mineralogical remote sensing data using Self-Organizing Maps. Remote. Sens. Environ. 2015, 165, 86–99. [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Qu, K.; Zhou, J. Reconstructing Sound Speed Profile From Remote Sensing Data: Nonlinear Inversion Based on Self-Organizing Map. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 109754–109762. [CrossRef]

- Shalaginov, A.; Franke, K. A new method for an optimal som size determination in neuro-fuzzy for the digital forensics applications. In Proceedings of the Advances in Computational Intelligence: 13th International Work-Conference on Artificial Neural Networks, IWANN 2015, Palma de Mallorca, Spain, June 10-12, 2015. Proceedings, Part II 13. Springer, 2015, pp. 549–563.

- Viviano-Beck, C.E.; et al. MRO CRISM Type Spectra Library. https://crismtypespectra.rsl.wustl.edu, 2015. NASA Planetary Data System.

- Kohonen, T. Self-Organizing Maps, 3rd ed.; Vol. 30, Springer Series in Information Sciences, Springer, 2001.

| Number of Neurons | Execution time (hours and minutes) |

|---|---|

| 225 | 00:38 |

| 400 | 01:28 |

| 625 | 01:54 |

| 900 | 02:31 |

| 1225 | 03:25 |

| 1600 | 09:47 |

| 2025 | 07:17 |

| 2500 | 07:03 |

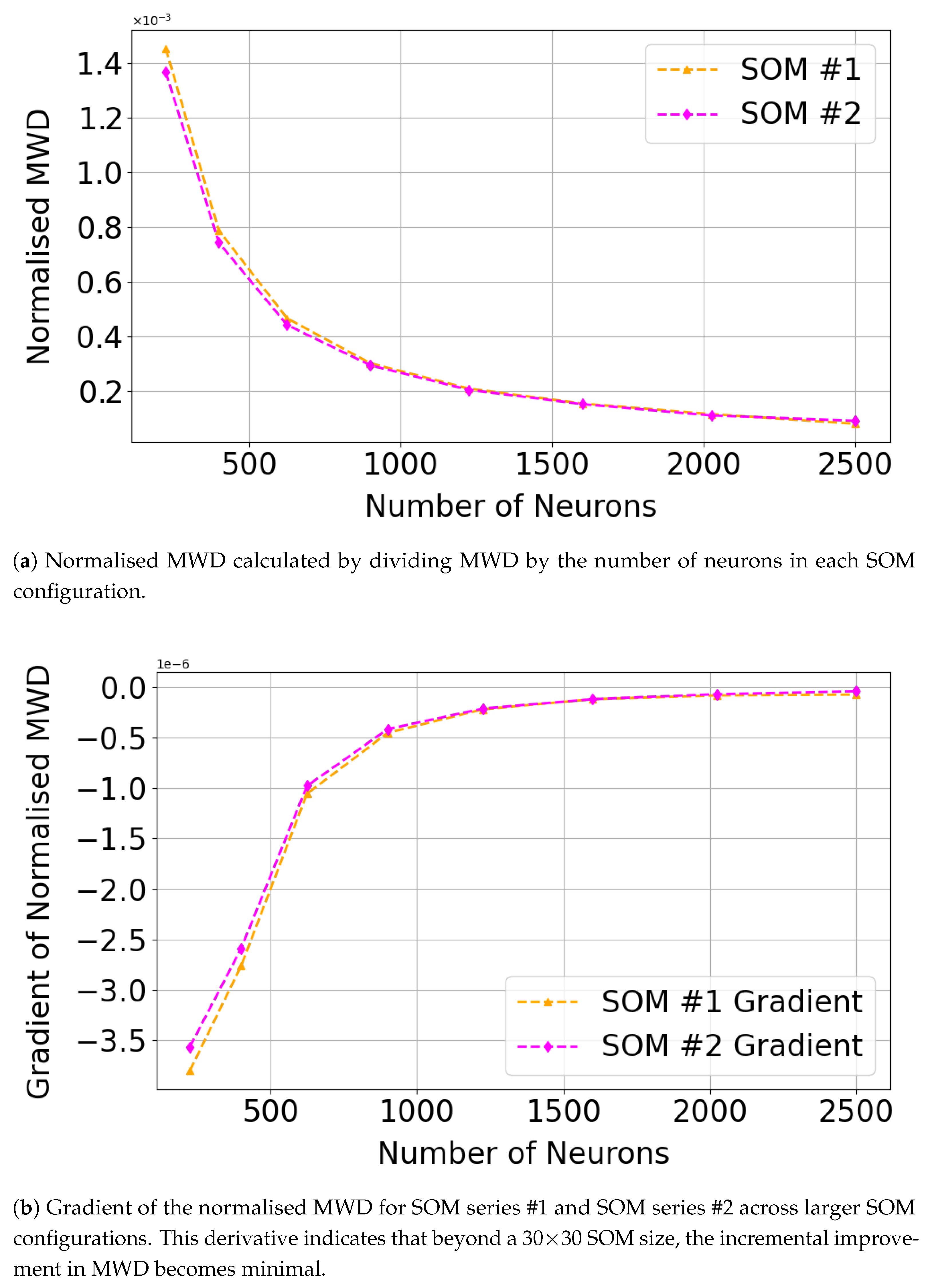

| Neurons | MWD | Norm. MWD | Gradient |

|---|---|---|---|

| 225 | 0.3269 | 1.453E−03 | E−06 |

| 400 | 0.3150 | 7.874E−04 | E−06 |

| 625 | 0.2916 | 4.665E−04 | E−06 |

| 900 | 0.2719 | 3.021E−04 | E−07 |

| 1225 | 0.2566 | 2.095E−04 | E−07 |

| 1600 | 0.2480 | 1.550E−04 | E−07 |

| 2025 | 0.2356 | 1.163E−04 | E−08 |

| 2500 | 0.2017 | 8.069E−05 | E−08 |

| Neurons | MWD | Norm. MWD | Gradient |

|---|---|---|---|

| 225 | 0.3074 | 1.366E−03 | E−06 |

| 400 | 0.2971 | 7.427E−04 | E−06 |

| 625 | 0.2763 | 4.421E−04 | E−07 |

| 900 | 0.2653 | 2.947E−04 | E−07 |

| 1225 | 0.2511 | 2.050E−04 | E−07 |

| 1600 | 0.2442 | 1.527E−04 | E−07 |

| 2025 | 0.2253 | 1.112E−04 | E−08 |

| 2500 | 0.2298 | 9.192E−05 | E−08 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).