1. Introduction

A course recommendation mechanism recommends similar courses based on learners’ preferences [1]. Udemy, Coursera, and EdX are online training resources that utilize such methodologies and offer a wide variety of courses across several disciplines [2]. Online course recommendation systems are becoming increasingly popular because they guide students to discover suitable courses and enrich their learning experiences by offering personalized recommendations tailored to their needs [3].

A recommendation system is a variety of information filtering systems designed to recall the possible rating or preference that a user would give a particular item. It is a program that suggests a suitable course to users [4]. For example, it can recommend a movie to watch on Netflix or suggest a product to buy on online shops [5]. A variety of types of recommender systems contribute to filtering information by suggesting suitable content based on numerous data sources and methods. Content-based filtering and Collaborative filtering are among the most widely applied and studied methods in various applications, such as education, e-commerce, and entertainment [6].

1. Content-Based Filtering: Under this method, items are observed and then matched with the user’s preferences. It performs tight item recommendations based on past interactions, utilizing techniques such as TF-IDF and machine learning. It is very personalized, but it has a problem of a cold start and can lead to a filter bubble, as the diversity of the shown content is reduced. To illustrate, a movie streaming service that proposes movies to the client according to his or her preferences regarding actors and genres [7].

2. Collaborative filtering: This method suggests items not based on their features, but instead on the behavior patterns of the users. It identifies similar users or items using techniques such as user-based and item-based collaborative filtering. Although efficient, it has problems with data sparsity and cold start. An example is where Netflix suggests programs to watch depending on what similar users to you have watched [8].

Online AI courses often lack individualized recommendations, resulting in many users having less-than-ideal learning experiences. Conventional methods of finding courses, such as keyword-based searches or manual browsing, don’t offer customized suggestions [9,10], especially when there are numerous courses to choose from. This phenomenon is known to occur in some instances, resulting in information overload, which leads to poor learning processes and decreased levels of satisfaction among learners. Besides, a significant portion of current recommendation systems is based on the collaborative filtering algorithm, which cannot be efficiently implemented in situations where user data is sparse, as for courses or new users, resulting in the cold start problem [8].

In this regard, this paper proposes the design of a content-based recommendation system that focuses on online courses in artificial intelligence. Content-based filtering can achieve good and significant results in the course recommendation problem by utilizing only course attributes such as titles, descriptions, and categories, without requiring a considerable amount of historical user interaction data. This strategy aims to enhance course discovery, reduce information overload, and improve the overall educational experience of AI learners. In addition to strengthening course discovery and improving the overall learning experience, our method ensures learners receive accurate and personalized recommendations.

This study introduces an AI recommender system that combines TF-IDF and BERT for effective content representation and enhances the system’s accuracy with the aid of a Random Forest classifier. Unlike most systems, infer learning relies just on the course metadata and not on interaction with students. A set of 2,238 Udemy AI courses was gathered by web scraping and preprocessing. Ninety-one percent of the cases were handled correctly, and the contributions of this research are:

We constructed a real-world dataset of 2,238 AI-related courses collected from Udemy using multiple web scraping sessions, followed by rigorous cleaning and preprocessing to ensure data quality.

A novel hybrid recommendation architecture is introduced, combining TF-IDF for lexical feature extraction, BERT embeddings for contextual semantic representation, and a Random Forest classifier to enhance predictive accuracy.

The proposed system addresses the cold-start problem effectively by relying solely on course metadata, eliminating the need for historical user interaction data.

Extensive empirical evaluation demonstrates that the proposed approach significantly outperforms state-of-the-art baselines, achieving a recommendation accuracy of 91.25% and an F1-score of 90.77%.

The entire system is implemented and deployed as a real-time interactive web application using Flask, providing users with immediate and highly relevant AI course recommendations in a user-friendly interface.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 presents the details of the techniques employed in this study. Next, in

Section 3, we introduce the literature review on recommendation systems.

Section 4 contains our methodology. The experimental results are presented in

Section 5. Finally,

Section 6 presents the conclusions and outlines future work.

2. Literature Review

Various applications and usage methods of recommendation systems, as well as their associated challenges, have already been outlined in numerous studies concerning the educational field. Pointing out the imperfections that our offered solution aims to address, the following section presents a detailed literature review on content-based filtering and its application in the context of online learning.

Julian et al. [17] presented a self-governing structure for a recommendation system that can be employed to enhance the education process by recommending online courses to students. The contextual data, student information, and course requirements used in the research were made available through the online learning environment (VLE). There is certainly improvement in terms of utilizing metadata, but the study has not explored hybrid and content-based filtering methods. The study also highlights the potential of intelligent systems in the context of personalized learning, which is one of the objectives of our system, namely, to provide customized course recommendations.

In [18], the authors applied genetic algorithms and K-means clustering to enhance educational recommendations. Although this cutting-edge approach enhanced accuracy, the research gave special attention to collaborative filtering and did not utilize metadata to its full extent. Yonghong Tian [19] proposed a hybrid recommendation system that combines collaborative filtering and content-based filtering to enhance the utilization of library resources. In the investigation, the clustering algorithms were employed to address the problem of data sparsity. This method, however, required a substantial amount of user-item interaction data to be effective. To reduce this dependence, the proposal suggests limiting ourselves to using content-based filtering alone, utilizing metadata such as course categories, levels, and descriptions, to make recommendations based on user preferences.

In [20], Yiling Dai explored the role of explanations in improving user satisfaction and learning outcomes in a math recommender system. Although the study highlighted the significance of individualized explanations, it did not place a strong focus on metadata usage. Metadata is utilized comprehensively in the system, serving not only to enhance accurate recommendations but also to facilitate a better learning experience for the user. Additionally, in a separate article, the authors in [12] developed a personalized book recommender system that employed collaborative filtering and Euclidean distance measures. The recommender system’s accuracy was enhanced in this research work, with a primary focus on the Amazon review dataset, which comprises user ratings and reviews. Personalization could also be improved by including metadata, such as book descriptions and their corresponding genres. Zhong and Ding [8] introduced a system that recommends learning resources based on collaborative filtering. Content recommendations were generated based on behavioral data, including user interactions and learning patterns. The following issues were to be addressed in the studies: the cold start problem, data sparsity and diversity, and content-based filtering.

Research studies presented in this section demonstrate the importance of recommendation systems as a method for addressing information overload, personalization, and data sparsity issues in the education field. Collaborative filtering has had a broad application, but it has not been widely used in cases involving missing data or for new users, as it relies on user Utilization of Metadata interaction data. It, however, offers an alternative to content-based filtering through the use of extensive information that makes recommendations in this respect. However, gaps included in:

1. To get proper suggestions, only a minimal number of researchers use metadata, including levels, classifications, and descriptions, fully.

2. Problem of Cold Start: Content-based filtering addresses the issue of collaborative filtering methods’ inability to handle new users and objects.

3. Scalability and simplicity: Most solutions are associated with complicated algorithms and might be challenging to scale and use.

4. Over-reliance on Collaborative Filtering: Many systems rely on information about user interactions, which makes them useless for courses and new users.

Recent studies on course recommendation systems have utilized deep learning and hybrid techniques. For example, Li and Kim (2021) introduced the DECOR model—a deep learning–based framework capturing both user behavior and course attributes—demonstrating improved accuracy over collaborative filtering methods [21].

Guruge et al. (2021), in a systematic literature review, highlighted the increasing trend towards hybrid recommender systems for online courses and noted the advantages in addressing cold-start issues [22].

A recent approach by Lee et al. (2023) proposed a two-stage collaborative-filtering model enhanced with item-dependency awareness, achieving a high AUC of 0.97 on real-world course data. In another hybrid strategy, an AutoLFA model combined autoencoder and latent factor analysis to boost recommendation performance across multiple datasets [26].

Unlike these approaches, our system uniquely merges TF-IDF for lexical features and BERT embeddings for semantic understanding, with a Random Forest classifier layered on top. It addresses cold-start solely via metadata, and includes full deployment as a real-time Flask web application—a combination not commonly explored in the existing literature.

This study addresses these gaps by developing a content-based recommendation system for online AI courses using a dataset collected from Udemy. Without relying on information about user interactions, the system generates precise recommendations by utilizing metadata, including course titles, descriptions, classifications, and levels. Content-based filtering enables the proposal of recently uploaded courses based on their qualities, although it does not entirely resolve the cold-start issue. The system’s efficient and scalable design ensures that it can be used practically in online learning environments.

3. Theoretical Backgrounds

3.1. Techniques Used in Feature Extraction

Feature extraction is a core process in the AI Course Recommender System, as it converts unstructured text data into structured numerical data [11]. Through this, the system can quantify course content and establish similarities among different courses. In this study, two of the most prominent techniques employed in feature extraction were TF-IDF Vectorization and BERT Embeddings. To enhance the efficiency of feature extraction, course names and course descriptions were merged into a new feature called combined content. The merging enables the title keywords and context information in the description to be utilized for similarity analysis. By combining keyword-based and semantic approaches, the system can provide more accurate course recommendations [12].

3.1.1. TF-IDF Vectorization

Term Frequency-Inverse Document Frequency (TF-IDF) is a standard feature extraction technique in Natural Language Processing (NLP) that identifies the importance of words within a document and reduces the impact of commonplace but less significant words in distinguishing meaning [13]. It is very effective for keyword detection that describes course content [12]. TF-IDF has two main elements. Firstly, Term Frequency (TF) measures the frequency of a word appearing in a course description relative to the total words in the description. Secondly, Inverse Document Frequency (IDF) assigns more importance to words that appear in fewer course descriptions so that commonplace words will not dominate the similarity analysis.

3.1.2. Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (BERT)

It is a deep learning NLP model that outperforms traditional feature extraction methods, such as TF-IDF, in terms of word meaning and context understanding [14]. Unlike TF-IDF, which considers word frequency, BERT learns word relationships within a sentence, such as nuances, synonyms, and sentence syntax. BERT creates high-dimensional numeric text embeddings in such a way that semantically related courses are closer to one another in the vector space, even though they might not share the exact keywords. One of the most significant features of BERT is that it is bidirectionally reading, i.e., left-to-right as well as right-to-left, to understand the general context of a sentence. This represents a significant leap from traditional keyword-based approaches, such as TF-IDF, which analyze words in isolation without considering their interrelationships [15].

3.1. Random Forest

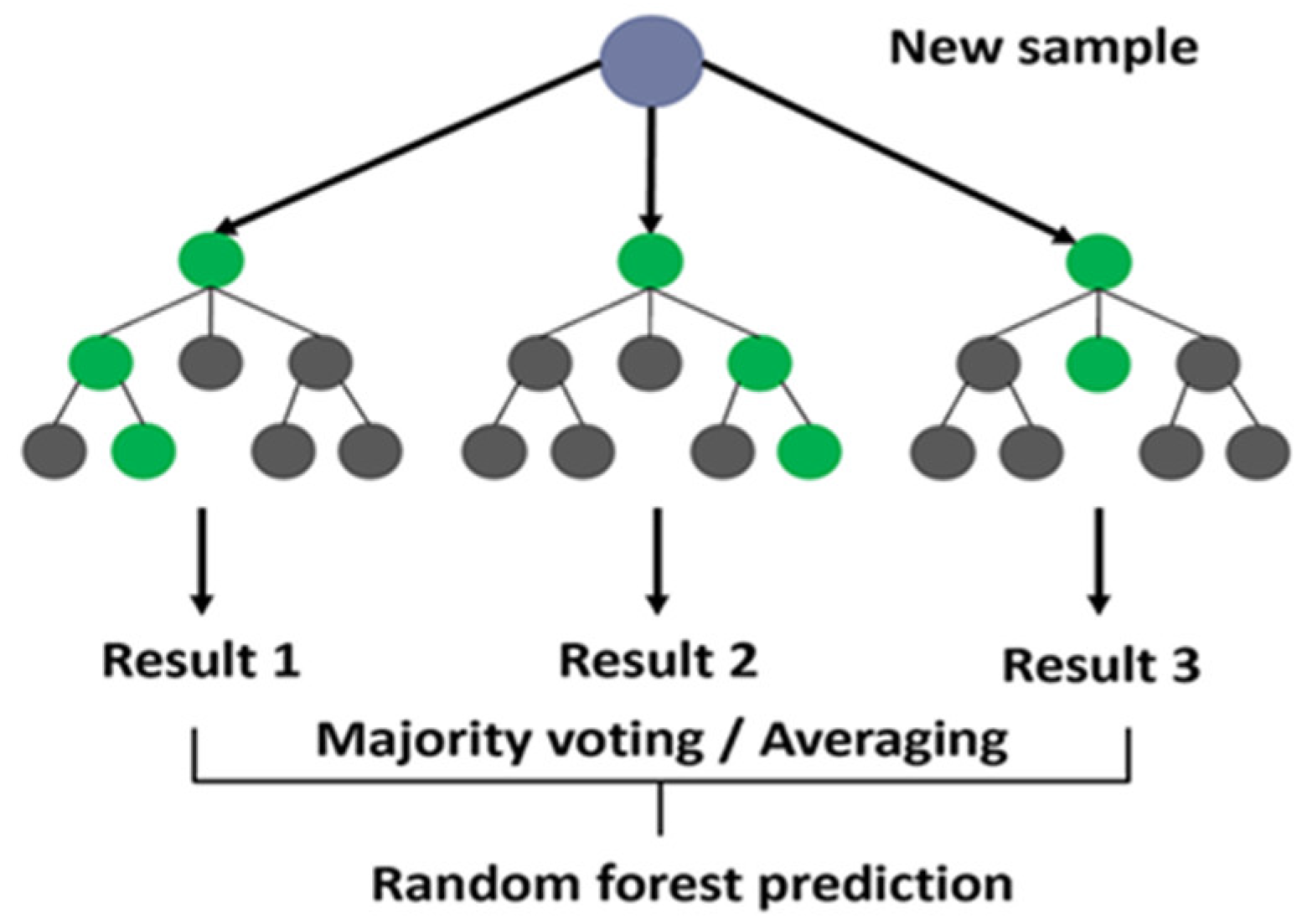

Random Forest, as illustrated in

Figure 1, is an ensemble learning method that constructs multiple decision trees and combines their predictions to enhance classification accuracy and mitigate overfitting. It can handle complex datasets and can expand as needed, making it widely used in machine learning tasks such as classification and regression. Random Forest relies on the concept of bagging (Bootstrap Aggregating), which involves training numerous decision trees on random subsets of the data and then aggregating the predictions of these trees to conclude. This enables the model to be effective in generalization across various datasets, thereby preventing overfitting, a common problem with single decision trees [16]. The final prediction is performed through a majority vote when classification is performed or through averaging when regression is performed. Random Forest is tolerant of noisy data, and it can express complex dependencies among features.

4. Methodology

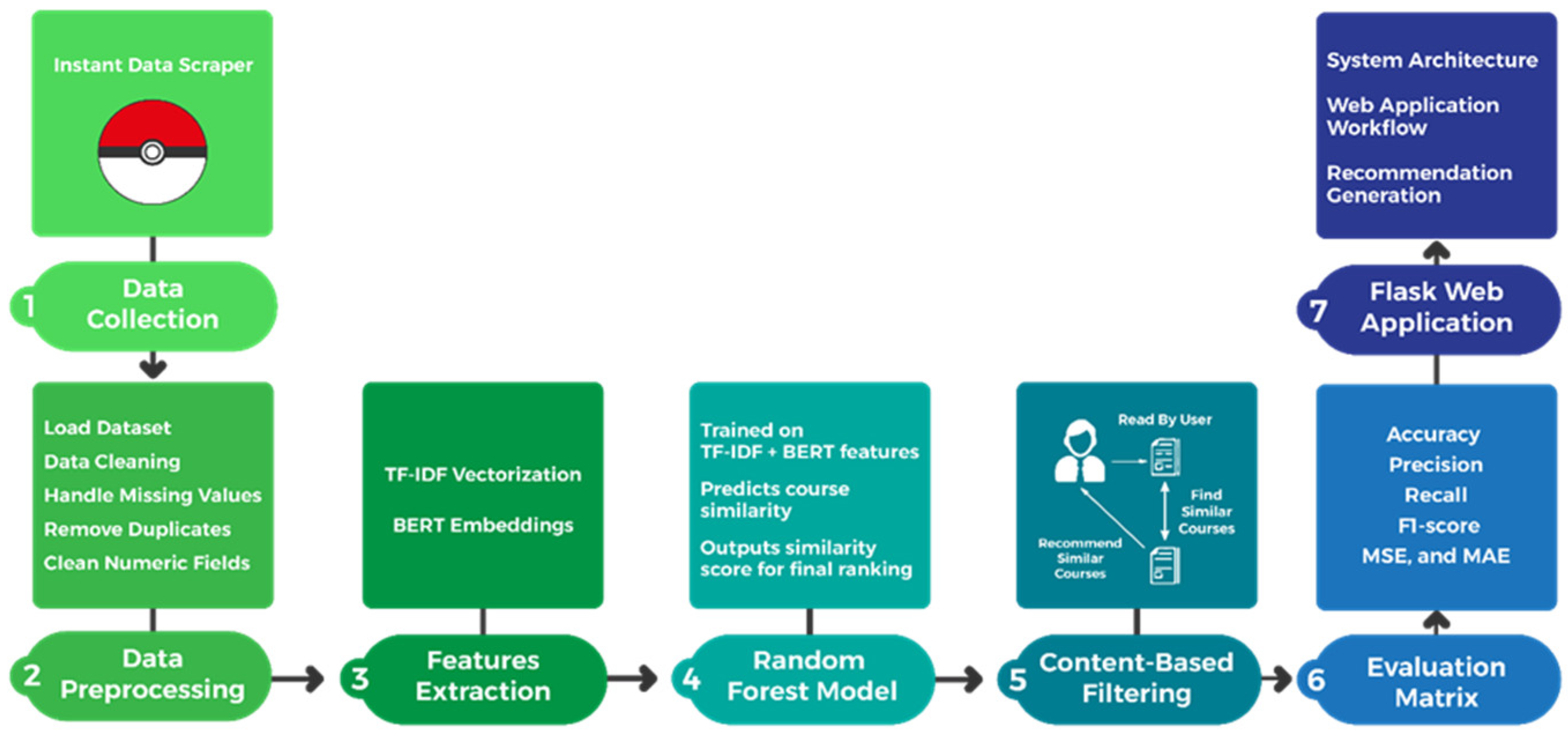

This study is planned and organized to create an AI Course Recommender System by using a machine learning model.

Figure 2 illustrates the main steps of the methodology, which include collecting data, preprocessing it, extracting features using the TF-IDF and BERT embeddings language model, training a Random Forest classifier to enhance accuracy, training a content-based model, evaluating the model, and developing the frontend using the Flask web application.

4.1. Data Collection

The dataset for this study was collected from Udemy, a well-known online learning platform, and was also gathered using Instant Data Scraper, a web scraping tool. The dataset consisted of AI-related courses carefully selected to enable the development of a content-based AI Course Recommender System. The scraping tool, only between 100 and 200 courses could have been taken out. Due to this limitation, data collection was conducted over ten separate scraping sessions. The collected files were then combined manually into a single, complete dataset. This dataset contains important attributes that provide us with helpful information about AI courses, including title, description, instructor name, and level. It also features key metrics such as course ratings, reviews, price, and duration, which are crucial for determining a course’s relevance. On a scale from 1 to 5, the average rating of a course shows how satisfied users are with the course, as in

Table 1 below, which introduces a raw dataset of AI Courses for 2238 rows and 12 columns extracted from Udemy. This information outlines the requirements for building the Recommender System. In the following parts of the study, feature extraction, similarity computation, and model training will all be based on the collected dataset.

4.2. Data Preprocessing

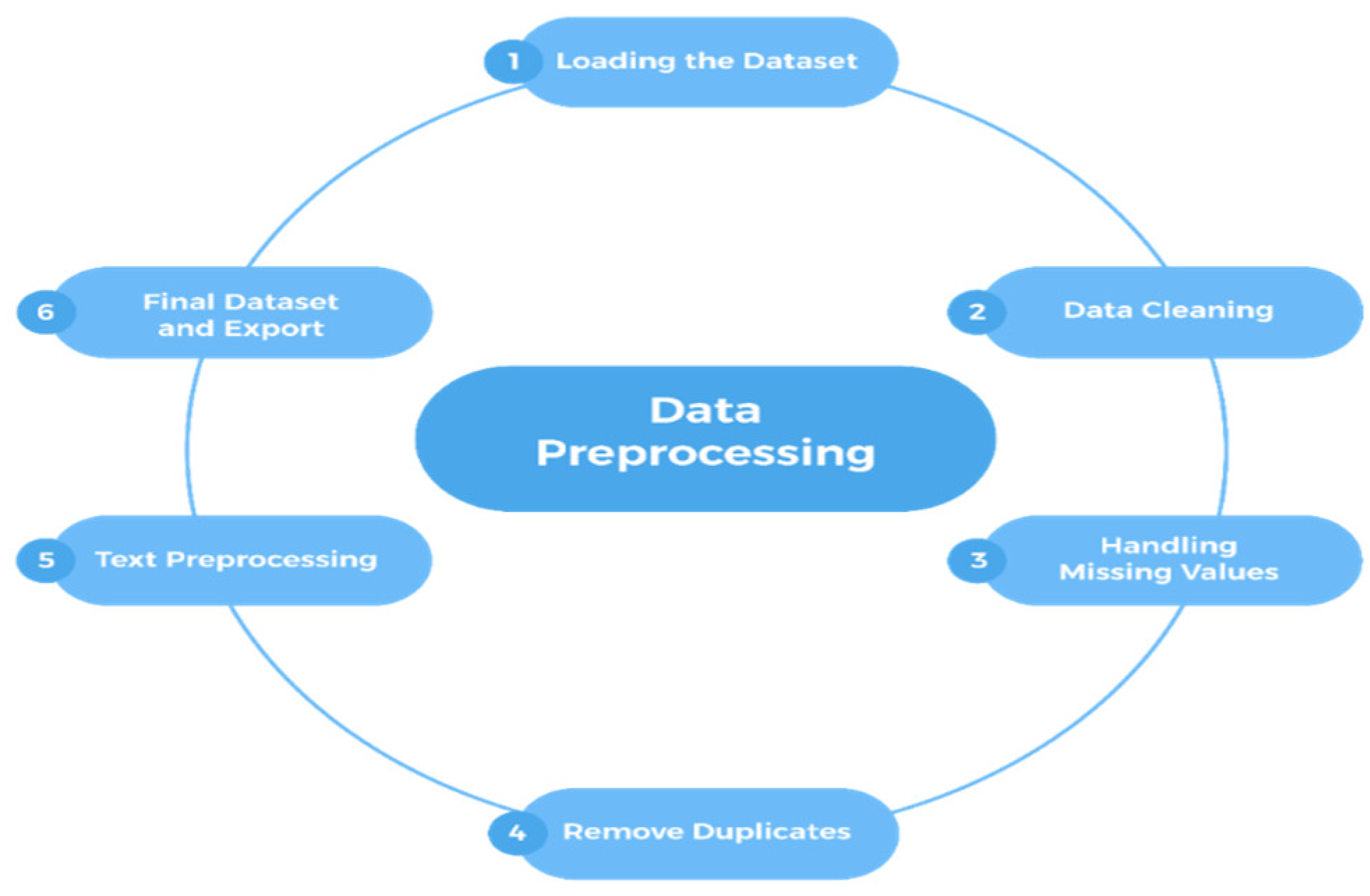

Data preparation is key to ensuring that the dataset is clean, structured, and prepared for feature extraction and model training. The unprocessed dataset had missing values, duplicate entries, confused words, and numerical errors. The issues were overcome via the Python language. The pre-processing methods employed in this research are explained in

Figure 3.

Loading the Dataset: Loading the dataset using Python and the Pandas library. This allowed for the handling of course attributes, such as name, description, instructor name, price, and rating. This step is preparing the dataset for further processing.

Data Cleaning: Several steps were implemented to ensure the dataset was consistent and accurate, including text normalization, removal of extra spaces and special characters, and standardization of numerical fields. To enable speedier processing, these procedures centered on standardizing textual and numerical values.

Handling Missing Values: While processing the dataset, we identified missing information, including instructor names and course descriptions, which required correction.

If an instructor’s name was missing, the course was marked as “Unknown”.

If a course description was unavailable, it was labeled as “No description available”. These corrections ensured dataset completeness and prevented issues caused by empty fields.

- 4.

Removing Duplicates: A few courses were duplicated due to the combined sessions of scraping. Initially, used Python’s drop_duplicates() function to remove duplicate values, but some courses still appeared twice because they had minor differences in other columns. Since those courses also shared the same URL, we removed duplicates based on their URLs (course-URL). That way, we ensured that each course appeared only once. Cleaning up these duplicates guaranteed that the dataset was accurate and well-structured.

- 5.

-

Text Preprocessing: For the textual processing of the data, we employed natural language preprocessing to calculate similarities between the course titles and descriptions. The techniques were:

Lemmatization & Tokenization: The course names were tokenized into individual words and lemmatized for the minimization of the words into the most fundamental form (e.g., “learning” → “learn”).

Stop word Removal: The universally present non-descriptive words within the texts’ context were eliminated to make the dataset more informative and efficient for machine learning models.

These preprocessing steps were crucial for the dataset’s readiness for content-based models, such as BERT-based embeddings and TF-IDF, utilizing the cosine measure to recommend courses effectively.

- 6.

Final Dataset and Export: The cleaned dataset will be used for feature extraction and the development of the recommendation model.his section may be divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

4.3. Feature Extraction

Feature extraction is a crucial process in the AI Course Recommender System, transforming course names and course descriptions into structured numerical features from unstructured data. Three feature extraction techniques were employed: TF-IDF Vectorization for keyword-based relevance, BERT Embeddings for deep semantic understanding, and Cosine Similarity to compute similarity. A concatenation-based approach was used to construct training data for the Random Forest model.

4.3.1. Term Frequency-Inverse Document Frequency (TF-IDF)

The Textual data about a course was transformed through the Term Frequency-Inverse Document Frequency (TF-IDF) technique to suggest content-based recommendations in the AI Course Recommender System. Keywords and contextual data, i.e., main keywords and description, were preserved due to the concatenation of course titles and descriptions into a single textual representation. To improve the data, a preprocessing step was employed to normalize the text string by converting it to lowercase and removing punctuation marks, non-alphanumeric characters, and stop words.

Subsequently, the processed text corpus was subjected to TfidfVectorizer of Scikit-learn with the following configuration parameters: ngram_range=(1,2) to combine both unigrams and bigrams to get a better semantic implementation; min_df=2 and max_df=0.9 to remove the terms that are either rare or too common; and stop_words=‘english’ to remove the non-informative tokens. Computing pairwise cosine similarity scores on the resulting sparse TF-IDF matrix, the system could compare the textual features of the courses and find how similar their content seemed.

4.3.2. BERT Embeddings

The various number of semantic relations that course descriptions imply was encoded using Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (BERT) embeddings. Such contextualized vector representations of words do not simply conduct keyword matching, but rather provide a significantly better understanding of the textual meaning. To return similar courses by calculating the cosine similarity after embedding with BERT [24]. This similarity measure on the TF-IDF vectors produced values in [0,1], where 0 meant total dissimilarity and one meant similarity. The cosine similarity measure was leveraged in a two-stage process: initially, to filter and rank candidate course recommendations based on textual relevance, and subsequently, to construct labeled training data for a Random Forest classifier, thereby enhancing the accuracy of the downstream recommendation model.

4.3.3. Fuzzy Matching for User Queries

To handle misspellings and inconsistencies, Fuzzy Wuzzy was used to match user inputs with existing course names.ata preparation is key to ensuring that the dataset is clean, structured, and prepared for feature extraction and model training. The unprocessed dataset had missing values, duplicate entries, confused words, and numerical errors. The issues were overcome via the Python language. The pre-processing methods employed in this research are explained in

Figure 3.

4.4. Random Forest Model

To further improve course recommendation accuracy from simple similarity estimations, a Random Forest classifier was integrated into the recommendation pipeline. It was tasked only with predicting whether two courses were similar or not, based on already-derived numerical features. The Random Forest classifier was applied to a consistent process for 100 decision trees in ensembling, which significantly enhanced the model’s generalizability. A random_state of 42 was utilized to provide reproducible outcomes across multiple runs. The model was trained by fitting a classifier to the training data. Subsequently, an evaluation was conducted on the withheld test dataset to thoroughly assess predictive performance and extrapolate the results to new data.

4.5. Content-Based Filtering

Content-based filtering is among the most common recommendation approaches, which suggests items based on their intrinsic properties rather than user behavior [25]. In contrast to collaborative filtering, which is user-behavior-oriented, content-based filtering examines course attributes to identify similarities and, therefore, is particularly suitable for applications where user interaction data are limited, as shown in

Figure 4. Feature extraction is a crucial process in the AI Course Recommender System, transforming course names and course descriptions into structured numerical features from unstructured data. Three feature extraction techniques were employed: TF-IDF Vectorization for keyword-based relevance, BERT Embeddings for deep semantic understanding, and Cosine Similarity to compute similarity. A concatenation-based approach was used to construct training data for the Random Forest model.

Content-based filtering was employed to recommend AI courses based on their textual descriptions. For the course-name and course-caption features, course names and descriptions were merged into a single feature, known as combined content. This means that both title keywords and description context will be utilized during the recommendation process. Content-based filtering was chosen in this research due to its scalability, flexibility, and precision in recommending courses.

4.6. Evaluation Metrics

The performance of the AI Course Recommender System is evaluated on various metrics to decide the effectiveness and accuracy of the course recommendations. These evaluation metrics are crucial for ensuring that the recommender system provides accurate and relevant course recommendations [26,27,28,29]. The following standard performance measures were used to quantify the performance of the recommender system:

F1-Score: is a blend of precision and recall, which provides a trade-off between the two. It is most effective when you need to evaluate the model’s performance, particularly when both false positives and false negatives are high. The formula is:

Mean Relative Error (MRE): MRE finds the difference between expected values and actual values, showing it as the number of times the expected value differs. It is good when you need to see the size of the error relative to the real values, not the error itself.

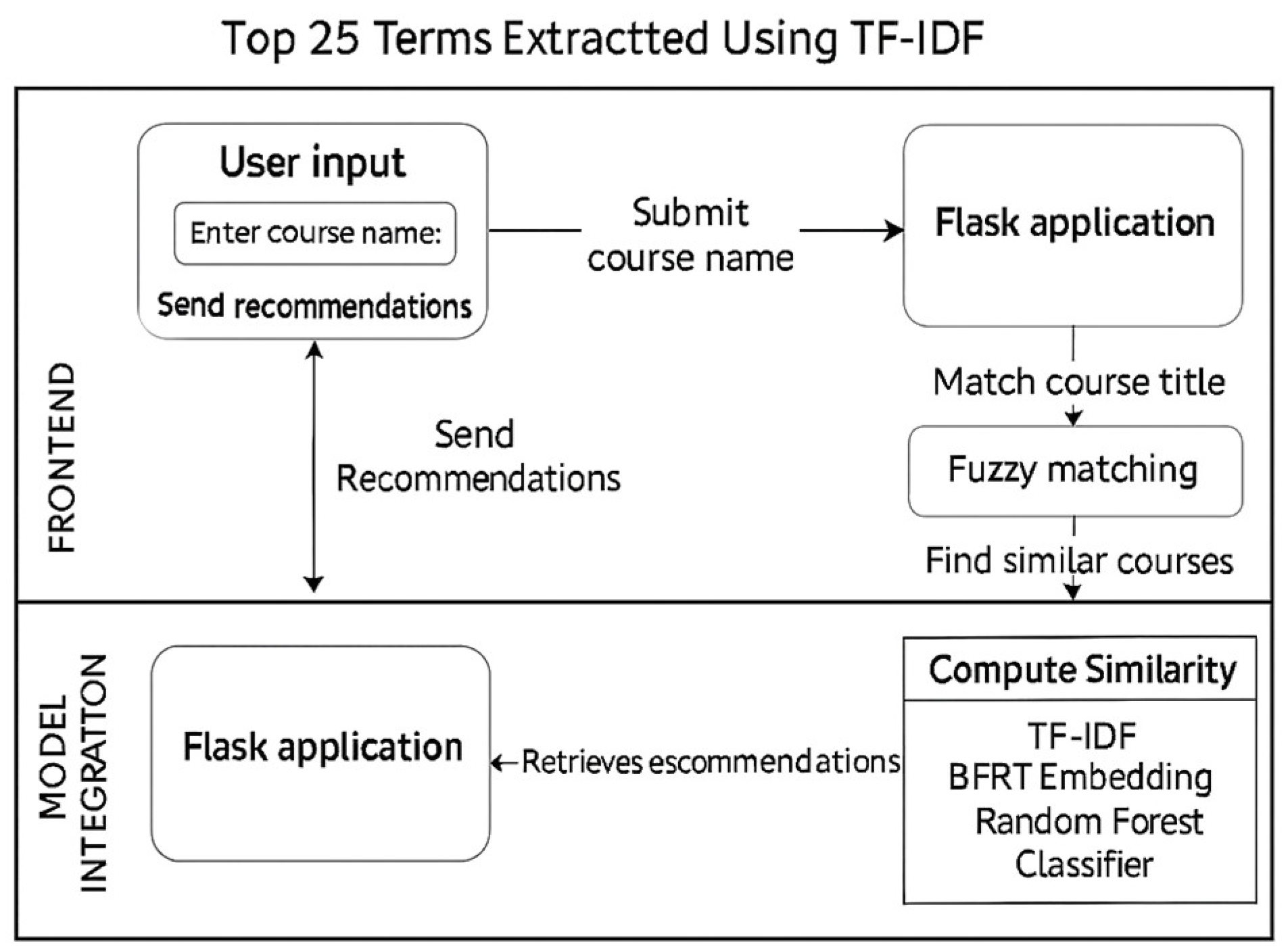

4.7. Flask Web Application

To provide users with an interactive experience, the AI Course Recommender System was deployed as a web-based application using Flask, a lightweight Python web framework well-suited for seamless integration with machine learning models and front-end interfaces. The system architecture follows a three-tiered design: (1) the frontend, developed with HTML, CSS, and Bootstrap, features a user-friendly input form that allows users to enter the name of a course of interest; (2) the Flask-based backend handles HTTP requests, manages the recommendation workflow, and serves the results; and (3) the model integration layer combines BERT embeddings, a pre-trained Random Forest classifier, and a TF-IDF-based similarity model to generate relevant course recommendations as shown in

Figure 5. Upon receiving user input, the system employs fuzzy string matching (via FuzzyWuzzy) to correct potential misspellings and map the input to the closest matching course title. The recommendation engine then computes similarity scores and returns the top five most relevant courses, each accompanied by metadata such as instructor name, cost, rating, number of reviews, and a similarity percentage score, thereby enhancing the user’s decision-making process.

5. Results and Discussion

This section presents the results of the AI Courses Recommender System, including feature extraction, model training, and the performance of recommendations, which provides an evaluation of the system’s accuracy in terms of TF-IDF, BERT embeddings, and a Random Forest classifier. It will demonstrate a comparison between different methods used for recommendations.

5.1. Results of the Feature Extraction and Representation

We extract features with the course name and course descriptions. The system will be able to make accurate recommendations based on course content.

5.1.1. TF-IDF (Term Frequency-Inverse Document Frequency)

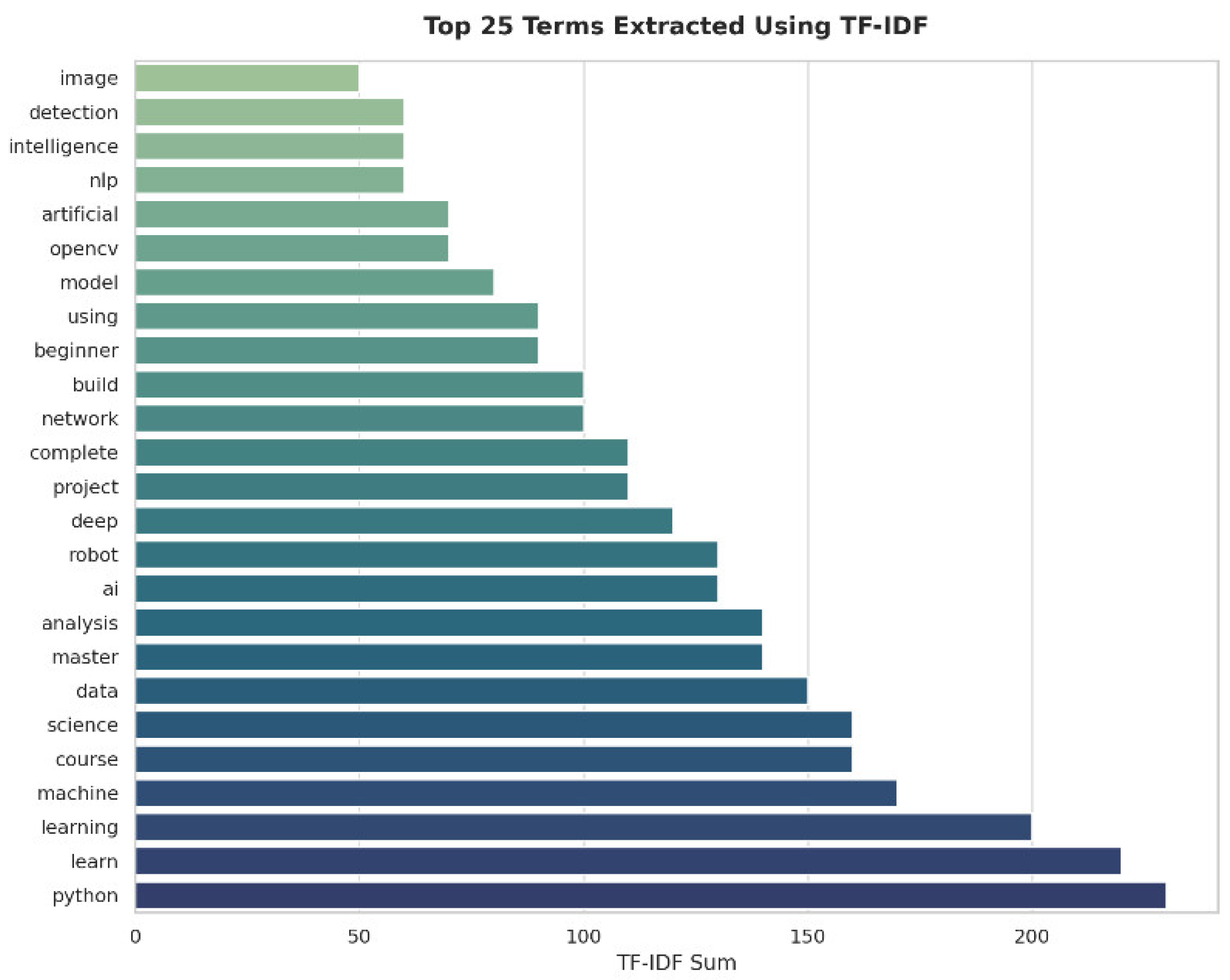

TF-IDF vectorization produced a matrix that represents the most important terms for each course. Commonly used terms, such as AI, machine learning, and Python, received high TF-IDF scores, indicating their relevance to the entire dataset. The most significant terms have been retrieved and used to define relevance for individual courses about a given user query.

Figure 6 illustrates the top 25 most significant terms that the TF-IDF method extracts. Such terms would help clarify the keywords that are most important for distinguishing course contents in the system and thus its recommendations.

5.1.2. BERT (Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers) Embeddings

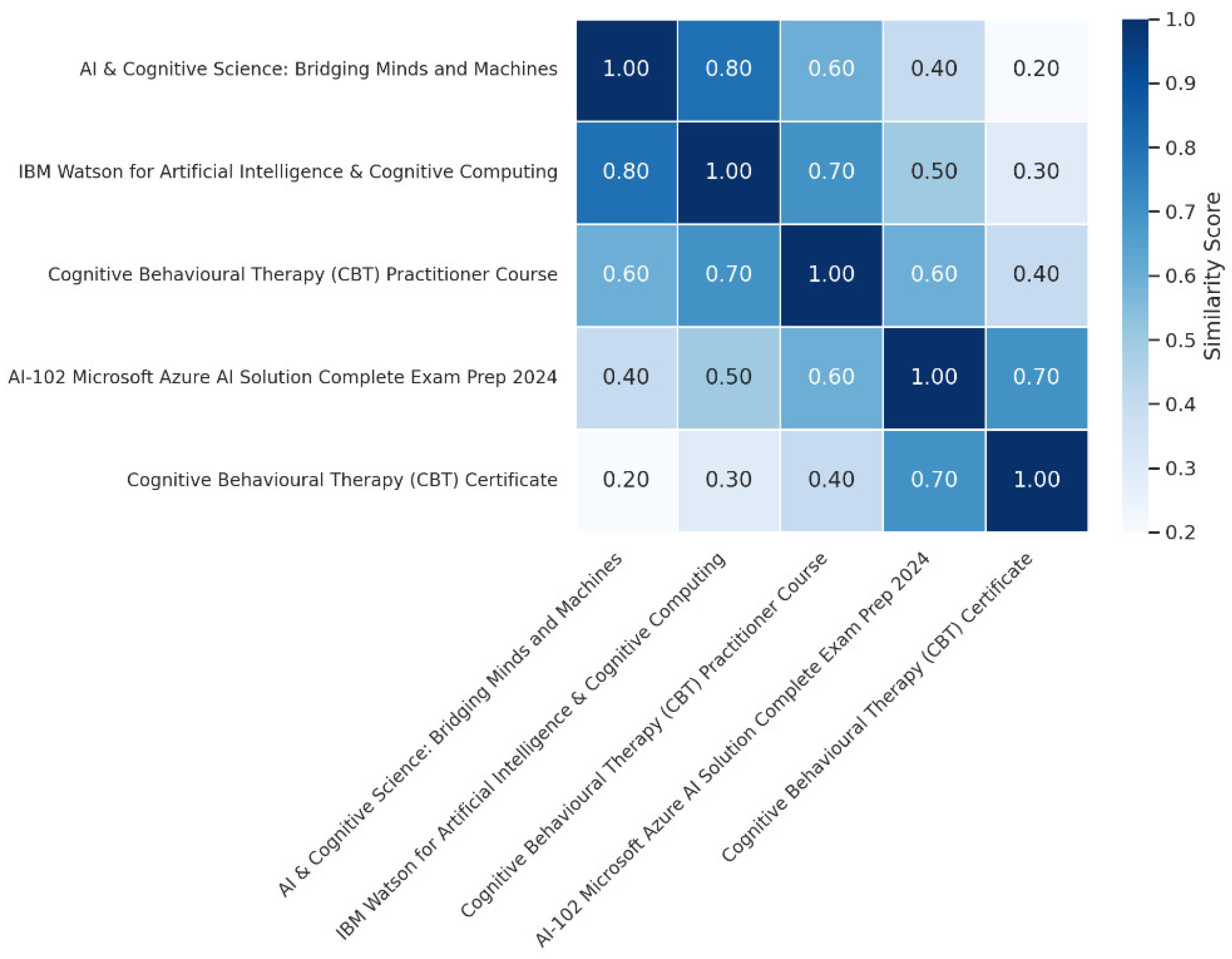

BERT embeddings were generated using a pre-trained BERT model, resulting in dense vector representations for each course. These embeddings capture much deeper meanings and relationships between courses, even when different phrasing is used in their content. By using cosine similarity, we visualized the similarity between courses based on their BERT embeddings, which further enhanced the performance of our recommendation system.

Figure 7 shows the visualization of cosine similarity between five courses using BERT embeddings. The heatmap reveals how courses with similar content are grouped, improving the recommendation system’s ability to suggest courses based on a deeper understanding of their content.

5.2. Model Training and Evaluation

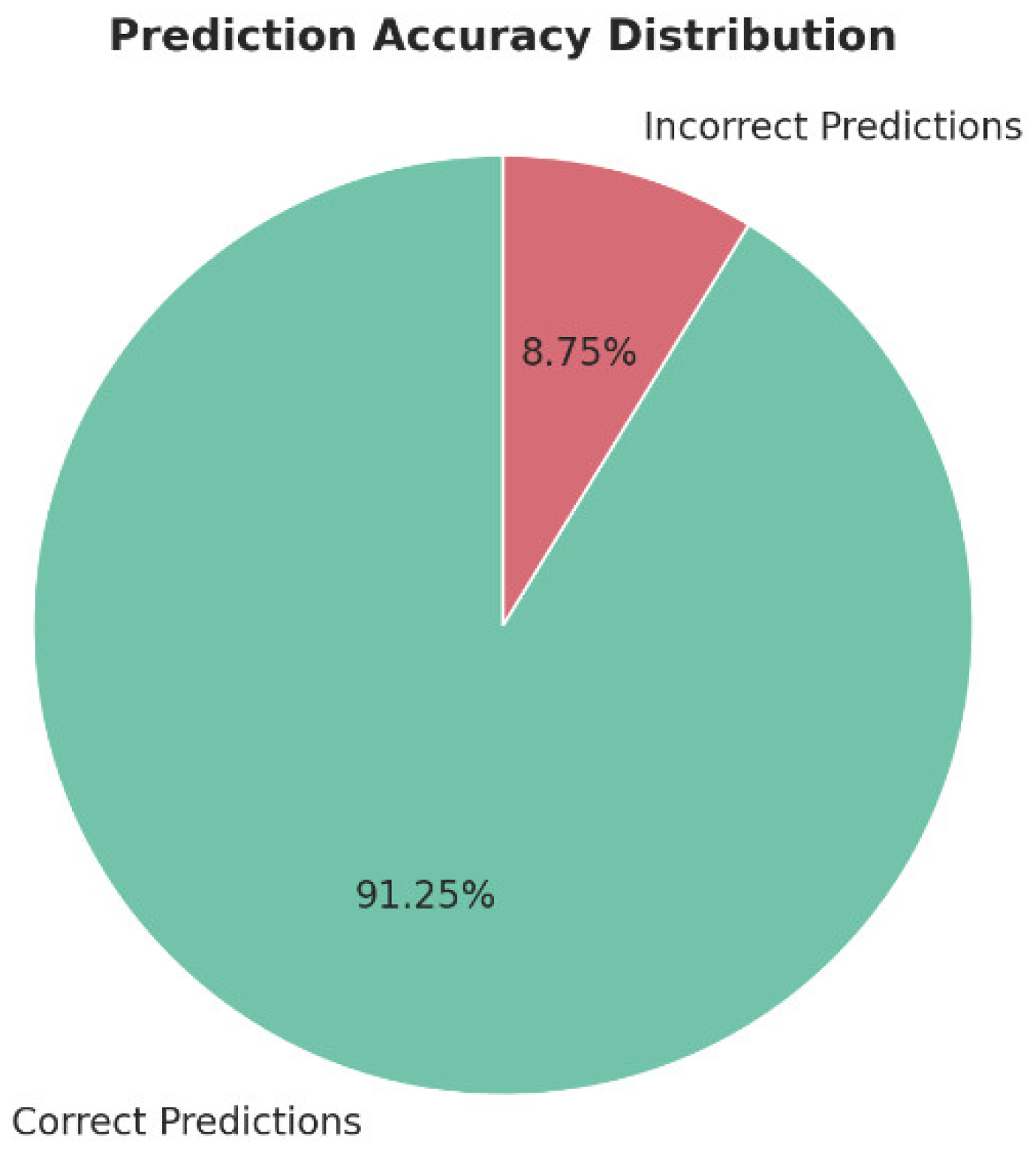

The model was trained using a Random Forest classifier, utilizing TF-IDF and BERT embeddings to predict course relevance based on cosine similarity. Key performance criteria were the primary focus of the study, which evaluated the efficiency and accuracy of the recommendation system. As shown in

Figure 8, the model achieves a 91.25% accuracy rate, demonstrating its ability to suggest relevant courses effectively.

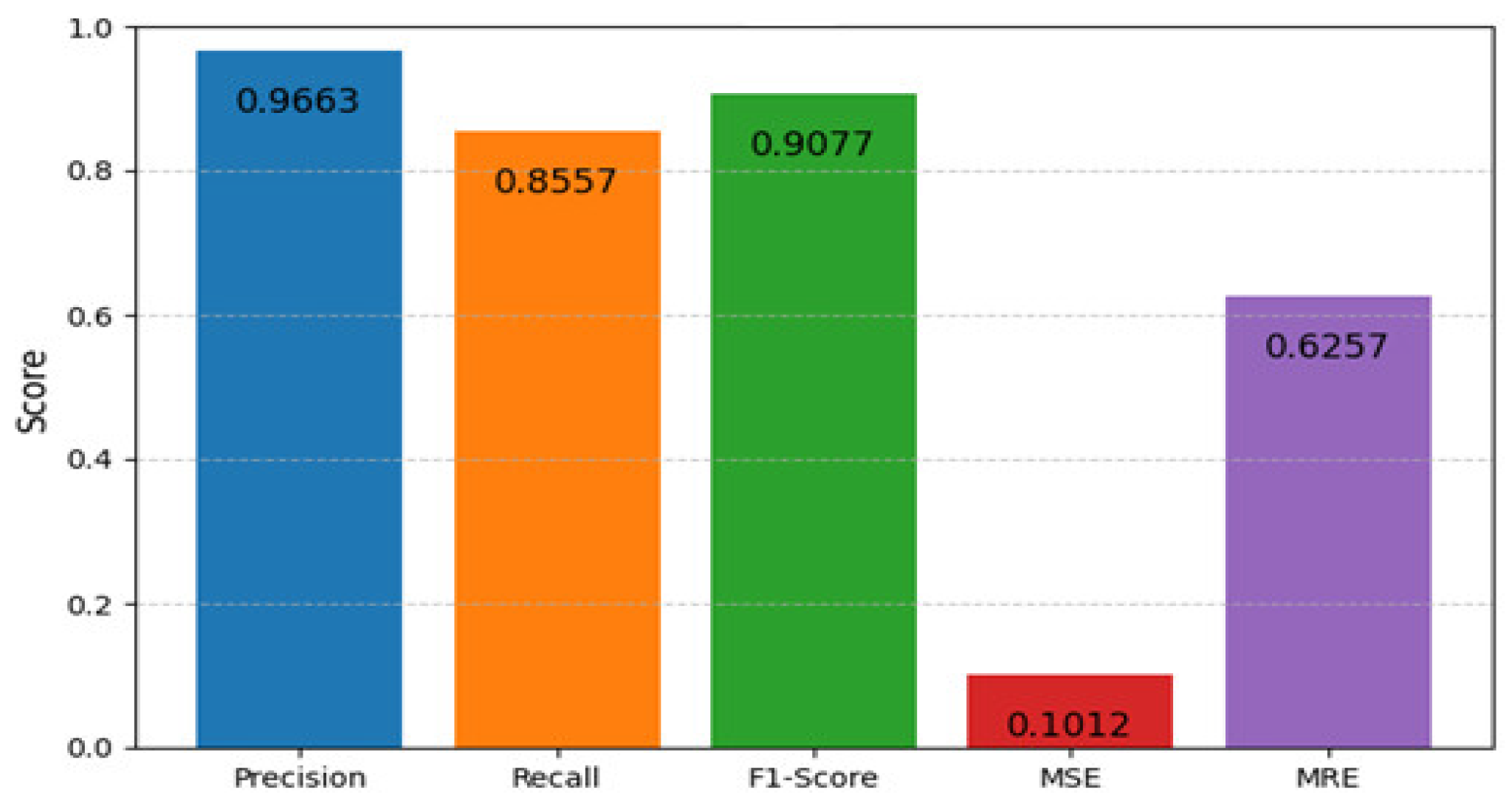

5.2.1. Performance Analysis

Performance evaluation metrics of the introduced model are depicted in

Figure 9, including Precision, Recall, F1-score, Mean Squared Error (MSE), and Mean Relative Error (MRE). Together, these metrics evaluate regression reliability and classification accuracy, offering insight into the model’s performance. With a high Precision of 96.63, the system showed that most of the recommendations were, in fact, appropriate to the user’s input. In recommendation systems, where it is costly to display ineffective items, this is crucial. The system effectively recovered a significant percentage of all relevant courses, as indicated by a recall score of 85.57. However, there is still a need for improvement. A balanced performance between accuracy and completeness in course retrieval was demonstrated by the F1-Score, which is a harmonic mean of Precision and Recall, which was 90.77. A recommender system tries to assess the similarity between courses. MSE and MAE describe the overall difference, but MRE helps you find mistakes for each similarity group and thus allows you to keep the quality of the ranking in recommendations. The Mean Squared Error (MSE) for the regression-based evaluation was determined to be 0.1012, indicating a minimal variance between the actual and displayed course similarity scores. In addition, the Mean Relative Error (MRE) of 0.6257 indicates possible areas for improvement in the estimation of similarity values.

This suggests that even if the model classifies relevant courses correctly, it may be able to improve the accuracy of similarity score predictions through tuning, particularly for use cases that require precise ranking. The hybrid model, BERT embeddings, TF-IDF similarity, and a Random Forest classifier show generally practical classification skills. These results highlight the system’s potential for use in actual educational platforms and validate its reliability in providing relevant course suggestions.

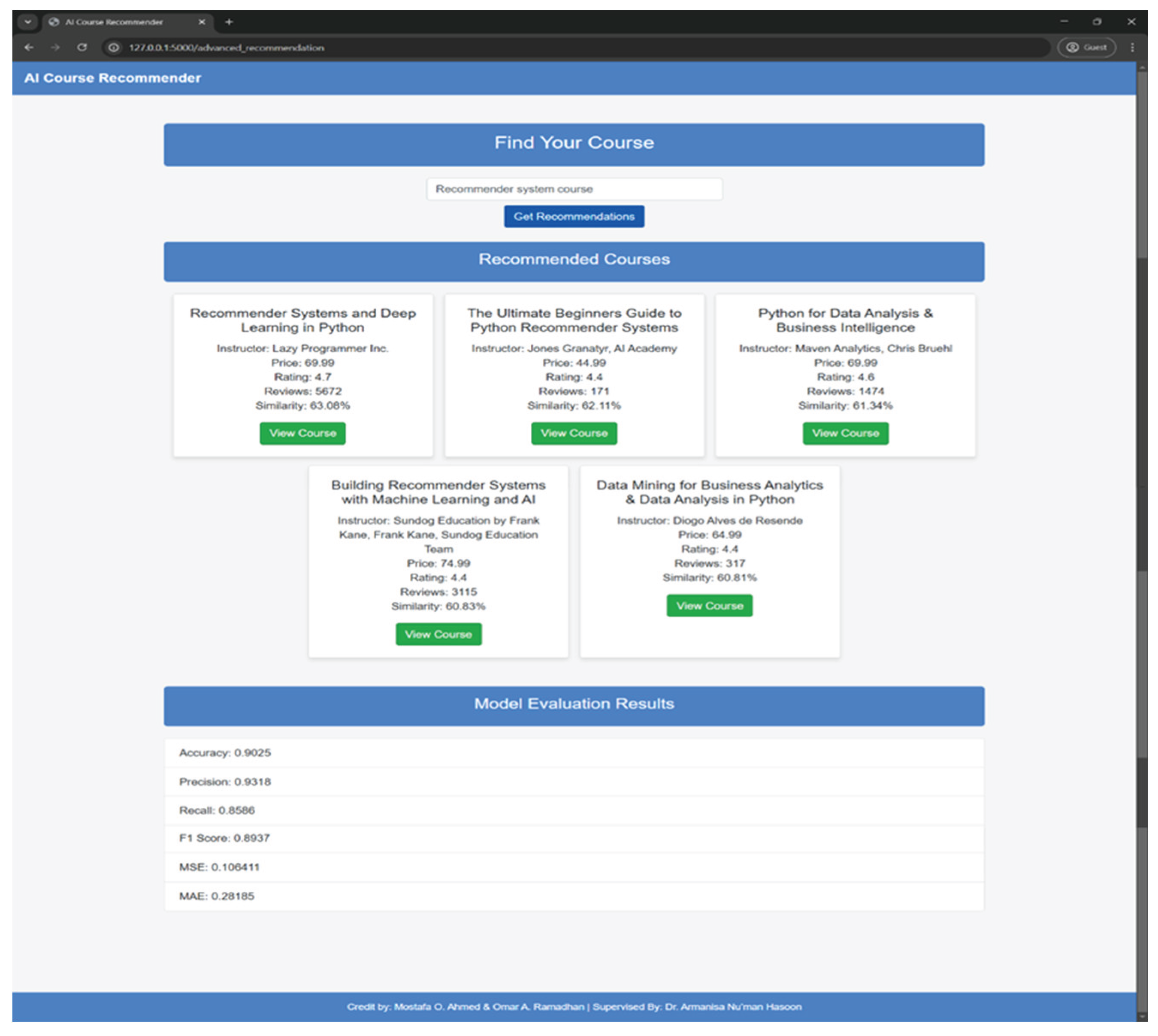

5.3. Deployment of the Flask Web Application

A course recommender system is implemented using a web-based Flask application that generates real-time recommendations and dynamic interaction with users. This section describes the visualization of recommendation results and model evaluation metrics. Upon receiving a course name or keywords related to it, the input is processed by an integrated TF-IDF and BERT model to provide recommendations regarding the course. Consequently, an update is made dynamically on the interface displaying the results and model performance metrics of relevance, including course details such as the instructor, price, ratings, and similarity score.

Figure 10 illustrates the application’s interface after a query is processed, presenting the results and associated performance metrics. It highlights the system’s responsiveness and ability to offer the user instant.

5.4. Comparing the Proposed System with Other Recommenders

To better demonstrate the effectiveness of the AI Course Recommender System, we conducted comparisons with other existing systems designed for educational or course recommendation settings. All the models were trained on the same Udemy AI courses dataset and given identical preprocessing and test splits.

Table 2 gives together the results of Accuracy, F1-score, and Mean Squared Error.

The hybrid proposal yields better results than traditional collaborative filtering, which relies heavily on users’ past actions. It works exceptionally well when you have to handle a lot of new events at once, such as when AI course platforms are used every day. Despite utilizing deep learning, DeepFM requires a substantial amount of interaction data to realize its potential fully. Instead, our approach utilizes context-focused keyword relevance (TF-IDF) in conjunction with BERT-generated semantic embeddings, as well as Random Forest classification. As a result, it achieves both good results and generalization, without requiring extensive user history.

5.5. Use Case Scenario

To demonstrate the practical use of the proposed system, a preliminary user study was carried out with five undergraduate students without any knowledge of AI. Specifically, each participant was required to fill in a few specific keywords of interest that he or she was learning (e.g., “deep learning,” “AI for beginners,” “Python for ML”) within the web-based system. The system found relevant AI courses in seconds, with each user including at least one course from the top 5 recommendations. Feedback was gathered via a brief Likert-scale form (1–5), asking students to rate ease of use, relevance of recommendations, and interface. Summary of participants’ responses is shown in

Table 3. Average satisfaction score was 4.6/5 with majority of users finding the recommendation “very relevant” to their goal. These preliminary evaluations evidence good usability and foster deployment in academic advising systems or university course portals.

6. Conclusions and Future Works

We introduced a hybrid AI course recommendation model which uses machine learning algorithms to improve personalized course recommendation. The system integrates TF-IDF for lexical-based features representation and BERT embeddings for deep contextual- based semantics, and classification is addressed using a Random Forest model. The proposed model attained 91.25% accuracy, 96.63% precision with F1-score 90.77% demonstrating the effectiveness of this model in matching user input with the relevant course. Feature-rich web application built with Flask, offering dynamic, interactive course recommendations in real-time via an intuitive user interface. One of the main limitations of this work is the use of a single source dataset extracted from Udemy, which might reduce the diversity of the model that can be generalized. Training Random Forest classifiers on such data may lead to over-fitting, and this in turn may influence recommendations of courses on unseen and wider topics. Next, one could explore enriching the dataset by adding courses from different platforms of online learning, or introducing regularization and cross-validation to improve the robustness of the models, or incorporating more sophisticated transformer-based models (e.g., fine-tuned BERT or GPT) to increase the adaptability of recommendations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.N.H.; methodology, A.N.H., S.K.A. and R.S.A.; software, A.N.H. and R.S.A.; validation, M.L.S., R.S.A. and S.K.A.; formal analysis, A.N.H. and S.K.A.; investigation, A.N.H. and S.K.A.; resources, S.K.A. and M.L.S.; data curation, S.K.A. and R.S.A.; writing— original draft preparation, A.N.H.; writing—review and editing, S.K.A., R.S.A. and M.L.S.; visualization, M.L.S. and R.S.A.; supervision, A.N.H.; project administration, A.N.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Gm, D., Goudar, R. H., Kulkarni, A. A., Rathod, V. N., & Hukkeri, G. S. A digital recommendation system for personalized learning to enhance online education: A review. IEEE Access, 2024; 12: 34019-34041. [CrossRef]

- Yurchenko, A., Drushlyak, M., Sapozhnykov, S., Teplytska, A., Koroliova, L., & Semenikhina, O. Using Online IT-Industry Courses in Computer Sciences Specialists’ Training. International Journal of Computer Science & Network Security, 2021:21(11):97-104. [CrossRef]

- Madhavi, A., Nagesh, A., & Govardhan, A. A study on E-Learning and recommendation system. Recent Advances in Computer Science and Communications (Formerly: Recent Patents on Computer Science), 2022; 15(5): 748-764. [CrossRef]

- Urdaneta-Ponte, M. C., Mendez-Zorrilla, A., & Oleagordia-Ruiz, I. Recommendation systems for education: Systematic review. Electronics, 2021; 10(14); 1611. [CrossRef]

- Algarni, S., & Sheldon, F. Systematic Review of Recommendation Systems for Course Selection. Machine Learning and Knowledge Extraction, 2023; 5(2): pp. 560-596. [CrossRef]

- Hassan, R. H., Hassan, M. T., Sameem, M. S. I., & Rafique, M. A. Personality-Aware Course Recommender System Using Deep Learning for Technical and Vocational Education and Training. Information, 2024; 15(12): 803. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S., Yao, L., Sun, A., & Tay, Y. Deep learning based recommender system: A survey and new perspectives. ACM computing surveys (CSUR), 2019; 52(1): 1-38. [CrossRef]

- Zhong, M., & Ding, R. Design of a personalized recommendation system for learning resources based on collaborative filtering. International Journal of Circuits, Systems and Signal Processing, 2022; 16(1): 122-131. [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q., Zhuang, F., Qin, C., Zhu, H., Xie, X., Xiong, H., & He, Q. A survey on knowledge graph-based recommender systems. IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering, 2020; 34(8): pp. 3549-3568. [CrossRef]

- Burke, R. Hybrid Recommender Systems: Survey and Experiments. User Model User-Adap Inter, 2002; 12: 331–370. [CrossRef]

- Ramzan, B., Bajwa, I. S., Jamil, N., Amin, R. U., Ramzan, S., Mirza, F., & Sarwar, N. An intelligent data analysis for recommendation systems using machine learning. Scientific Programming, 2019; 2019(1): 5941096. [CrossRef]

- Usman, A., Roko, A., Muhammad, A. B., & Almu, A. Enhancing personalized book recommender system. International Journal of Advanced Networking and Applications, 2022; 14(3): 5486-5492. [CrossRef]

- Thakkar, A., & Chaudhari, K. Predicting stock trend using an integrated term frequency–inverse document frequency-based feature weight matrix with neural networks. Applied Soft Computing, 2020; 96: 106684. [CrossRef]

- Zalte, J., & Shah, H. Contextual classification of clinical records with bidirectional long short-term memory (Bi-LSTM) and bidirectional encoder representations from transformers (BERT) model. Computational Intelligence, 2024; 40(4): e12692. [CrossRef]

- Selva Birunda, S., & Kanniga Devi, R. A review on word embedding techniques for text classification. Innovative Data Communication Technologies and Application: Proceedings of ICIDCA 2020,(03 February 2021), (pp. 267-281), 2021. [CrossRef]

- Parmar, A., Katariya, R., & Patel, V. A review on random forest: An ensemble classifier. In International conference on intelligent data communication technologies and internet of things (ICICI) 2018, (21 December 2018). (pp. 758-763), 2018. [CrossRef]

- Monsalve-Pulido, J., Aguilar, J., Montoya, E., & Salazar, C. Autonomous recommender system architecture for virtual learning environments. Applied Computing and Informatics, 2024; 20(1/2):69-88. [CrossRef]

- Chen, W., Shen, Z., Pan, Y., Tan, K., & Wang, C. Applying machine learning algorithm to optimize personalized education recommendation system. Journal of Theory and Practice of Engineering Science, 2024; 4(01): 101-108. [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y., Zheng, B., Wang, Y., Zhang, Y., & Wu, Q. College library personalized recommendation system based on hybrid recommendation algorithm. procedia cirp, 2019;83: 490-494. [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y., Takami, K., Flanagan, B., & Ogata, H. Beyond recommendation acceptance: Explanation’s learning effects in a math recommender system. Research and Practice in Technology Enhanced Learning, 2024; 19:1-21. [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Kim, J. A Deep Learning-Based Course Recommender System for Sustainable Development in Education. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 8993. [CrossRef]

- Guruge, D.B.; Kadel, R.; Halder, S.J. The State of the Art in Methodologies of Course Recommender Systems—A Review of Recent Research. Data 2021, 6, 18. [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.L.; Kuo, T.T.; Lin, S.D. A Collaborative Filtering-Based Two Stage Model with Item Dependency for Course Recommendation. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Data Science and Advanced Analytics (DSAA), Tokyo, Japan, 19–21 October 2017; pp. 496–503. [CrossRef]

- Pawar, A., Patil, P., Hiwanj, R., Kshatriya, A., Chikmurge, D., & Barve, S. Language Model Embeddings to Improve Performance in Downstream Tasks. In 2024 IEEE 16th International Conference on Computational Intelligence and Communication Networks (CICN), (December2024), (pp. 1097-1101), 2024.

- Javed, U., Shaukat, K., Hameed, I. A., Iqbal, F., Alam, T. M., & Luo, S. A review of content-based and context-based recommendation systems. International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning (iJET), 2021; 16(3): 274-306. [CrossRef]

- Ghatora, P. S., Hosseini, S. E., Pervez, S., Iqbal, M. J., & Shaukat, N. Sentiment Analysis of Product Reviews Using Machine Learning and Pre-Trained LLM. Big Data and Cognitive Computing, 2024; 8(12):1-18. [CrossRef]

- Sultan, L. R., Abdulateef, S. K., & Shtayt, B. A. Prediction of student satisfaction on mobile learning by using fast learning network. Indonesian Journal of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, 2022; 27(1): 488-495. [CrossRef]

- Kiran, R., Kumar, P., & Bhasker, B. DNNRec: A novel deep learning based hybrid recommender system. Expert Systems with Applications, 2020; 144. uthor 1, A.B.; Author 2, C.D. Title of the article. Abbreviated Journal Name Year, Volume, page range. [CrossRef]

- Shuwandy, M.L.; Alasad, Q.; Hammood, M.M.; Yass, A.A.; Abdulateef, S.K.; Alsharida, R.A.; Qaddoori, S.L.; Thalij, S.H.; Frman, M.; Kutaibani, A.H.; Abd, N.S. A Robust Behavioral Biometrics Framework for Smartphone Authentication via Hybrid Machine Learning and TOPSIS. J. Cybersecur. Priv. 2025, 5, 20. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).