1. Introduction

The guidelines of the Surviving Sepsis Campaign (SSC) discourage the administration of intravenous immunoglobulins (IvIg) in septic and septic shock patients primarily because the published studies do not fulfill the Evidence-Based Criteria (EBM) [

1]; actually, most published Randomized Clinical Trials (RCT) are biased by a number of original sins [

2], including the heterogeneity of patients enrolled, the different composition of the IvIg used, the variable timing of their administration, the sources of sepsis, the involved pathogens etc. The current definition of sepsis and septic shock consider these clinical entities as the consequence of a derangement of the immune system; the definition is wide enough to cover the hyperinflammatory phase and the immunosuppression that often appears in the advanced states of the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) admission [

3]. Consequently, the IvIg could be valuable due to either biological and clinical reasons; the former include their antibacterial and opsonizing capabilities and the immune-modulating activities, that makes them suitable both in the both phases of sepsis and during the immunoparalysis that often follows the initial insult [

4], whereas the latter are based on a number of investigations demonstrating that (a) low values of endogenous Ig are associated with a worse outcome in septic patients [

5]; (b) their decrease and/or failed increase in response to an infection is associated to the shift from sepsis to septic shock [

6,

7]; (c) septic patients given IvIg have a better outcome as compared to untreated ones [

8]; (d) this survival advantage is more marked in patients treated with a preparation enriched with higher-than-normal amounts of IgA and IgM (eIg) [

9,

10]; and, finally, that (e) early treated patients have a better outcome as compared with those given eIg in a more advanced phase of their clinical course [

11]. A mayor matter of concern for the use of this expensive preparation consists in the absence of precise indications for their initiation, making the decision to start their administration somewhat arbitrary: as a consequence, this approach can lead to the administration of eIg to moribund patients or, conversely, to withhold their use in patients that could benefit from it in a wide array of clinical settings in which the eIg could represent a valuable adjunctive therapy [

12].

To fill this gap and provide some rule of engagement (ROE) easily suitable at the bedside we used the data collected in a multi-center observational study obtained from a large number of patients given eIg.

2. Materials and Methods

The current study basically consists in three different phases. In the first we recorded the clinical course, a number of biological variables and the outcome of sepsis and septic shock patients given eIg enrolled in the Italian Multicentric SORRISO (Studio Osservazionale Registro Rianimazioni Italiane Sepsi Ospedaliere) observational registry, performed in Italy from May, 2015 until March, 2022 that involved 7 ICUs to study the effects of eIg in septic shock patients treated with eIg (Pentaglobin®, Biotest, Dreiech, Germany, Spain). Each patient admitted with septic shock or severe sepsis was considered eligible for the administration of eIg; the age < 18 years, pregnancy, known reactions to blood and derivates and a life expectancy < 3 months were considered exclusion criteria.

The severity of the clinical conditions at the admission was assessed with the SAPSII score. The diagnosis of septic shock was based on the current definitions [

3]. The diagnosis of sepsis-induced coagulopathy (SIC) was based on a platelet count < 100.000/mL and a spontaneous INR > 1.5 [

13].

The antibiotic therapy was defined adequate when (a) it was active against at least 75% of culture isolates or (b) it was coherent with the current guidelines for a determined infection. Multiple drug resistance (MDR) was defined as the acquired non-susceptibility to at least one agent in ≥ 3 antibiotic categories [

14].

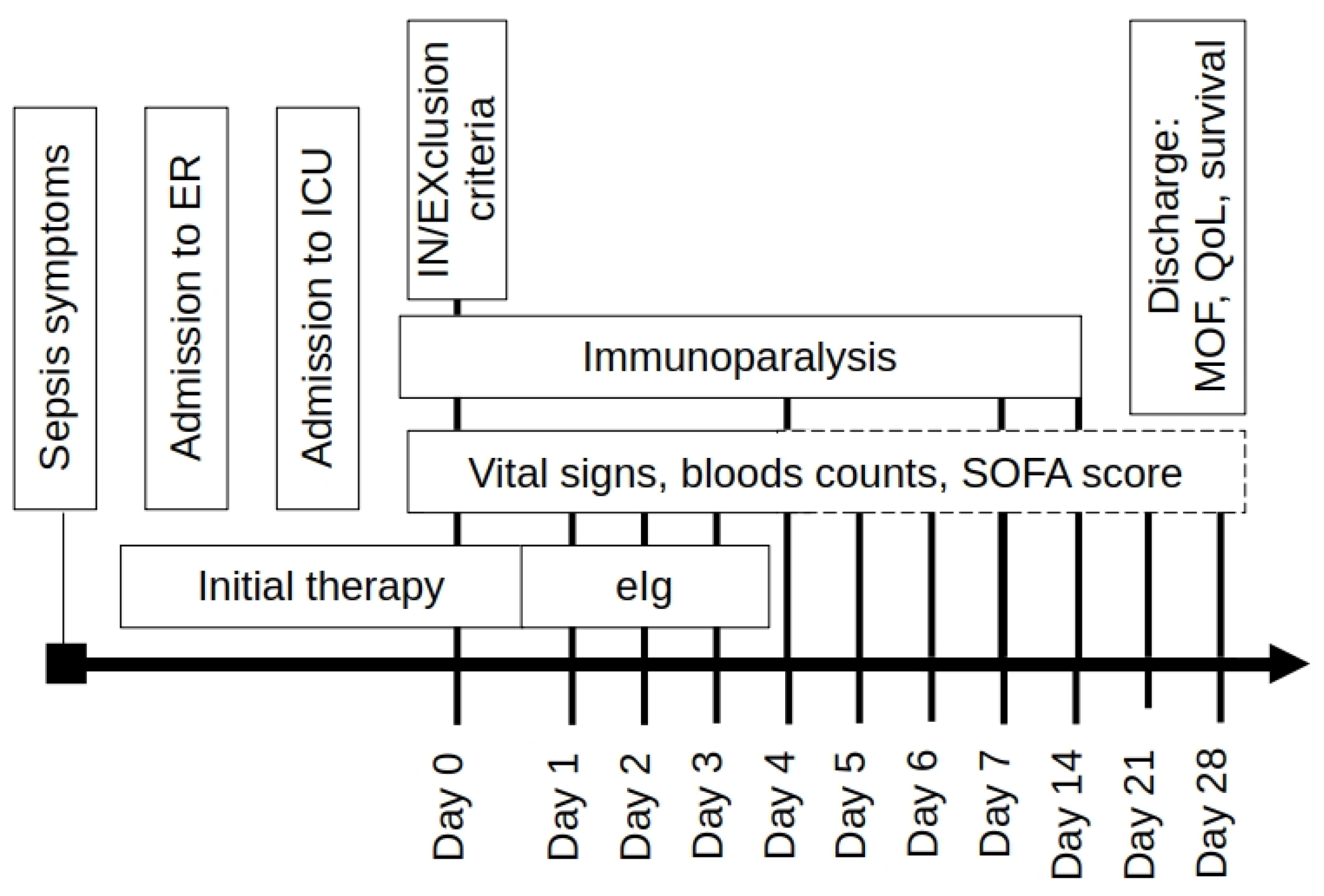

The decision of eIg administration was left to the attending staff but, since the start of the first infusion on, all ICUs followed the same monitoring protocol (

Figure 1).

Apart from the eIg, every ICU was allowed to follow its own internal procedures, including the use of techniques of blood purification (BP) with the exclusion of therapeutic plasma exchange as this procedure remove all the plasma content.

The eIg were administered at a fixed dose of 250 mg/kg for 3 consecutive days; the duration of each infusion varied from 12 to 24 hours. As the eIg are not removed or absorbed their administration was not interrupted during BP. The patients were subdivided in early and late starters (ES and LS) using a cutoff value of 72 hours from the hospital admission.

In the second phase we added some therapy-centered variables recorded in the SORRISO database that resulted significantly different between survivors (S) and non survivors (NS) including the timing of eIg initiation and the adequacy of the antibiotic therapy, to a preexistent score (TO-PIRO) [

15]; this score represents a modification of the PIRO system of description of the underlying conditions of septic patients [

16]; this considers four different items (that are Predisposition, Insult, Response, Organ failure) used to evaluate their influence on the outcome. In the TO-PIRO score, that has been developed from an experts’ consensus, each variable is given a score whose sum indicates the opportunity to administer the eIg within a determined time window.

In the last phase, all the statistically significant or near-significant variables demonstrated in this revised TO-PIRO Score (rTO-PIRO) were analyzed and used to build-up a SORRISO-SCORE.

Statistical analyses were performed unless otherwise indicated using Jamovi software version 2.3.28.

3. Results

In the considered period, 248 patients were enrolled in the study (

Table 1).

The most significant differences among the different centers include the age of the patients (p=0.009), the sites of infection (p<0.001) and with a borderline significant value the proportion of ICU admission for medical or surgical pathology (p=0.058); whereas the severity of cases did not differ among the centers (p=0.799); the lack precise enrollment criteria likely account for these variations. In the overall population, the appropriateness of the antibiotic treatment was 85%.

The coordinating center in Trieste alone enrolled about 2/3 of the total patients. Therefore, other important criteria that could potentially affect the primary outcome (28-day hospital survival) were also considered. Among these variables, the most significant were the presence of septic shock at the onset of therapy and the precocity of the treatment (hours between hospital admission and treatment initiation) with a cut-off early vs late of 72 hours.

The last two factors exhibited highly significant differences between the coordinating center and other hospitals (p<0.001). The coordinating center admitted more septic shock patients who received eIg within a shorter treatment-free interval. These factors seem to counterbalance each other, resulting in no significant impact on the primary outcome at 28 days (p=0.165).

The 28-day and in-hospital mortality rates were 38.3% and 44.4%. respectively.

Following this descriptive analysis, the impact of various factors on the response to eIg therapy was more comprehensively assessed using Kaplan Meier Curves analysis for binary parameters (presence/absence), either grouped by homogeneous clusters or based on a cut-off value.

Subsequently, the TO-PIRO score [

15] was modified by adding some variables identified by the SORRISO Project Board (

Table 2). The items included in this revised score (rTO-PIRO) included (a) the presence of any kind and any stage of solid or hematologic neoplasms; (b) the presence immunosuppression of whatever cause; (c) the blood levels of only the C-reactive protein (PCR) and procalcitonin (PCT); (d) a simplified DIC score for SIC evaluation [

13].

Subsequently, the influence of each component of the rTO-PIRO score on the outcome was analyzed separately.

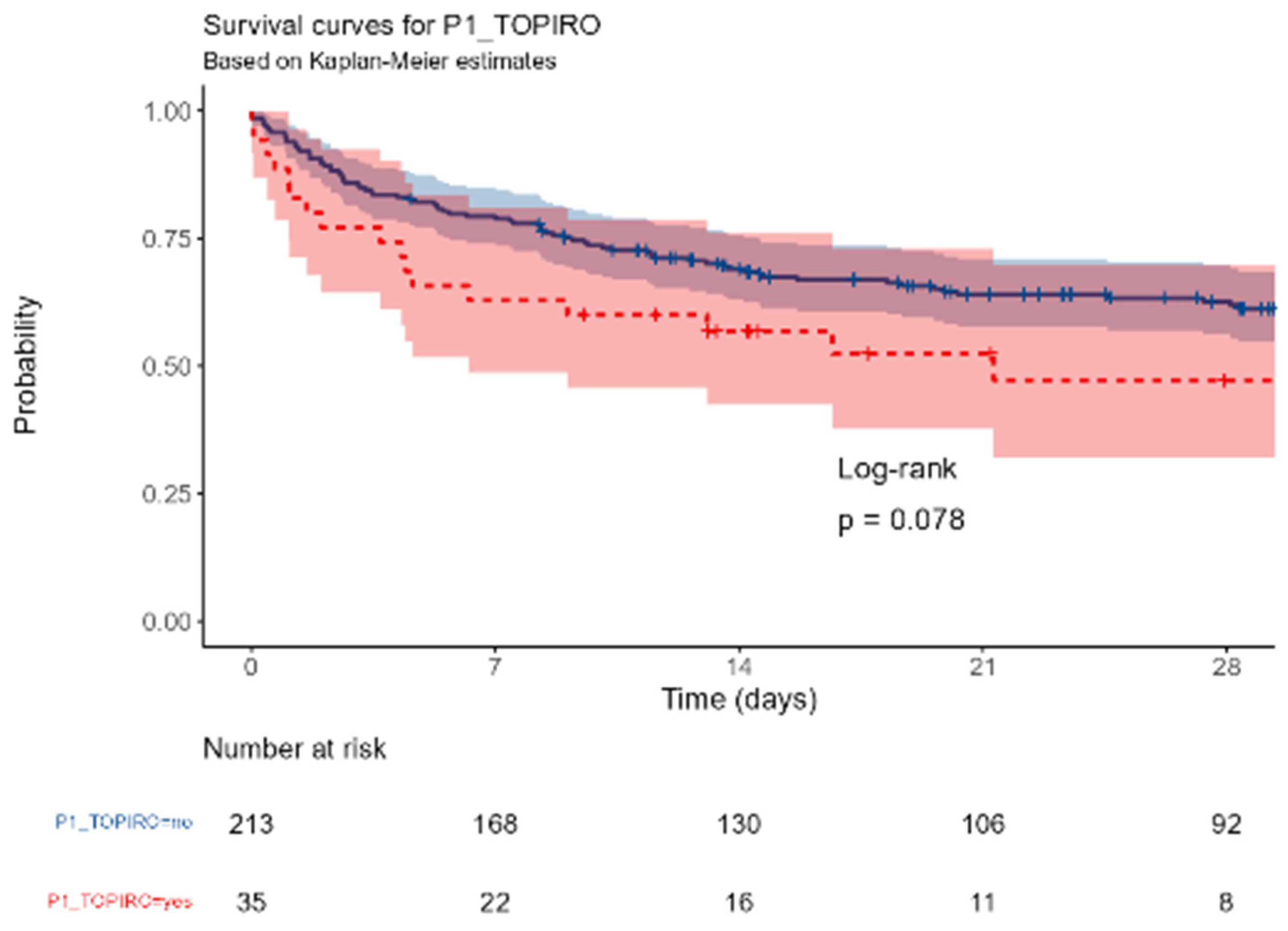

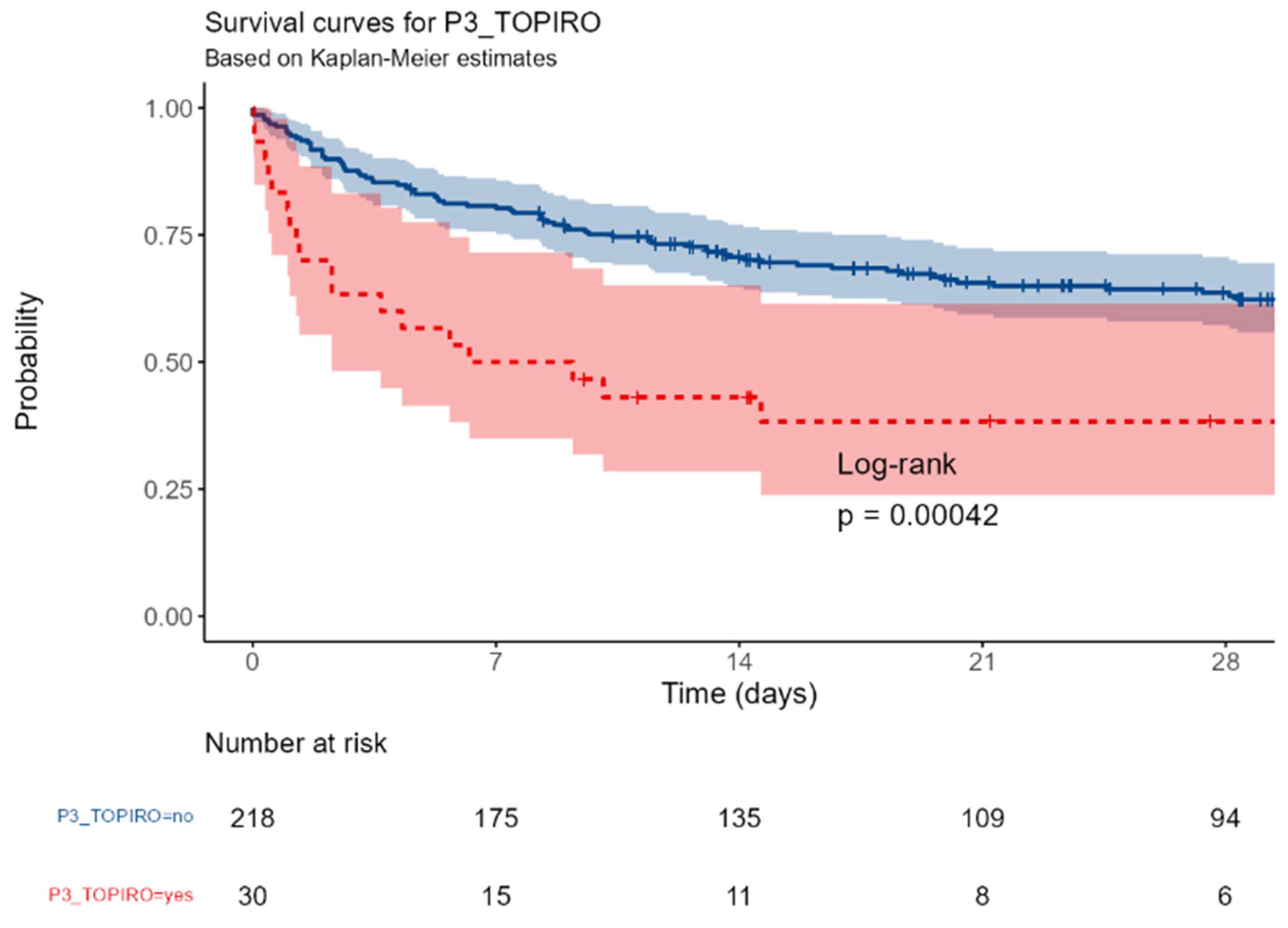

3.1. Predisposition Criteria

No difference in mortality was observed among the different centers. Similarly, neither gender (p=0,72), age groups (p=0,12), BMI (p= 0,94), colonization with MDR pathogens or fungi (p=0,75) were associated with the outcome; the presence of either solid or hematologic cancer was associated with a near-significant increased mortality (p= 0,078); conversely, any kind of immunosuppression was highly correlated with the outcome (p=0,00042)

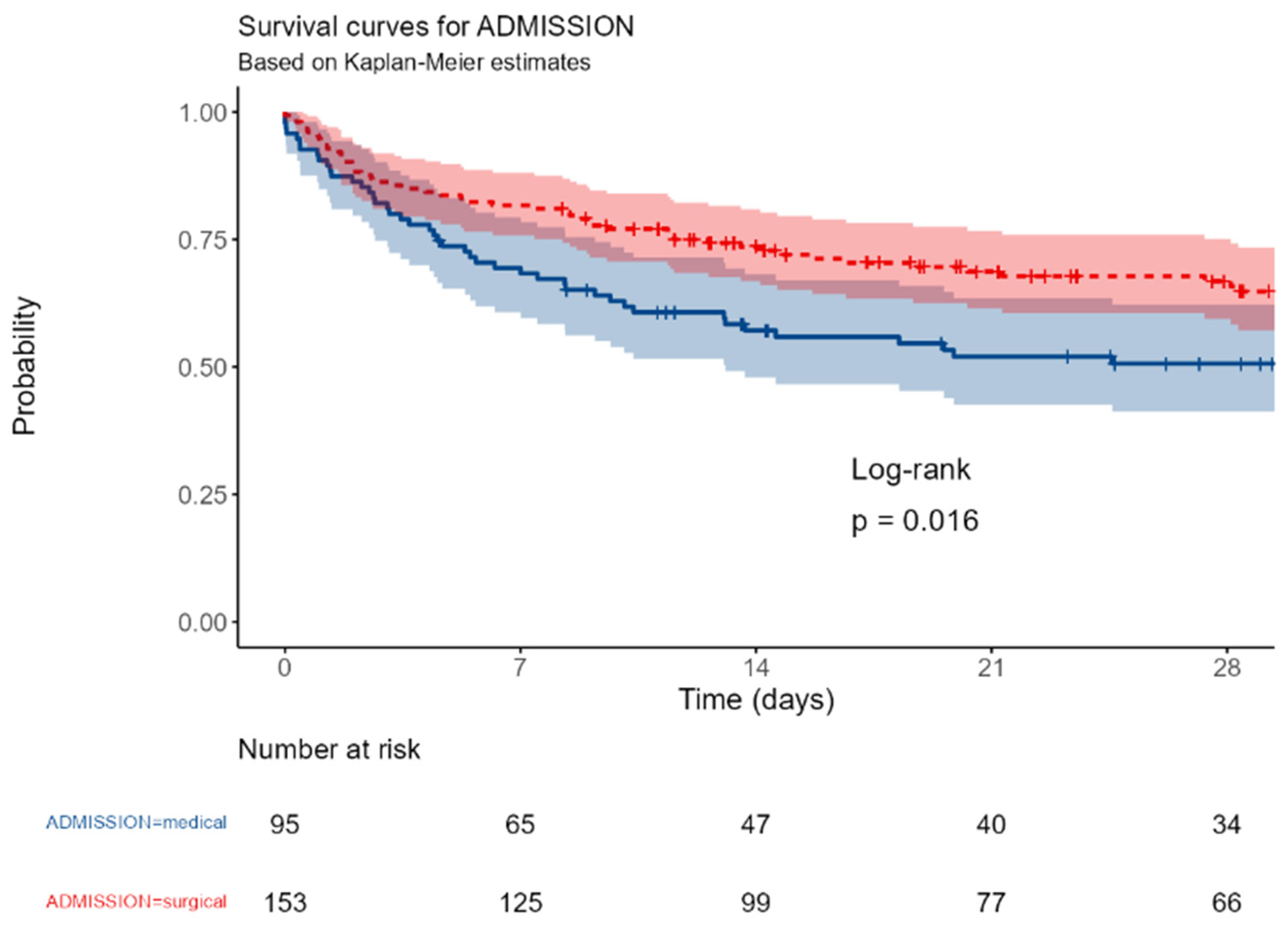

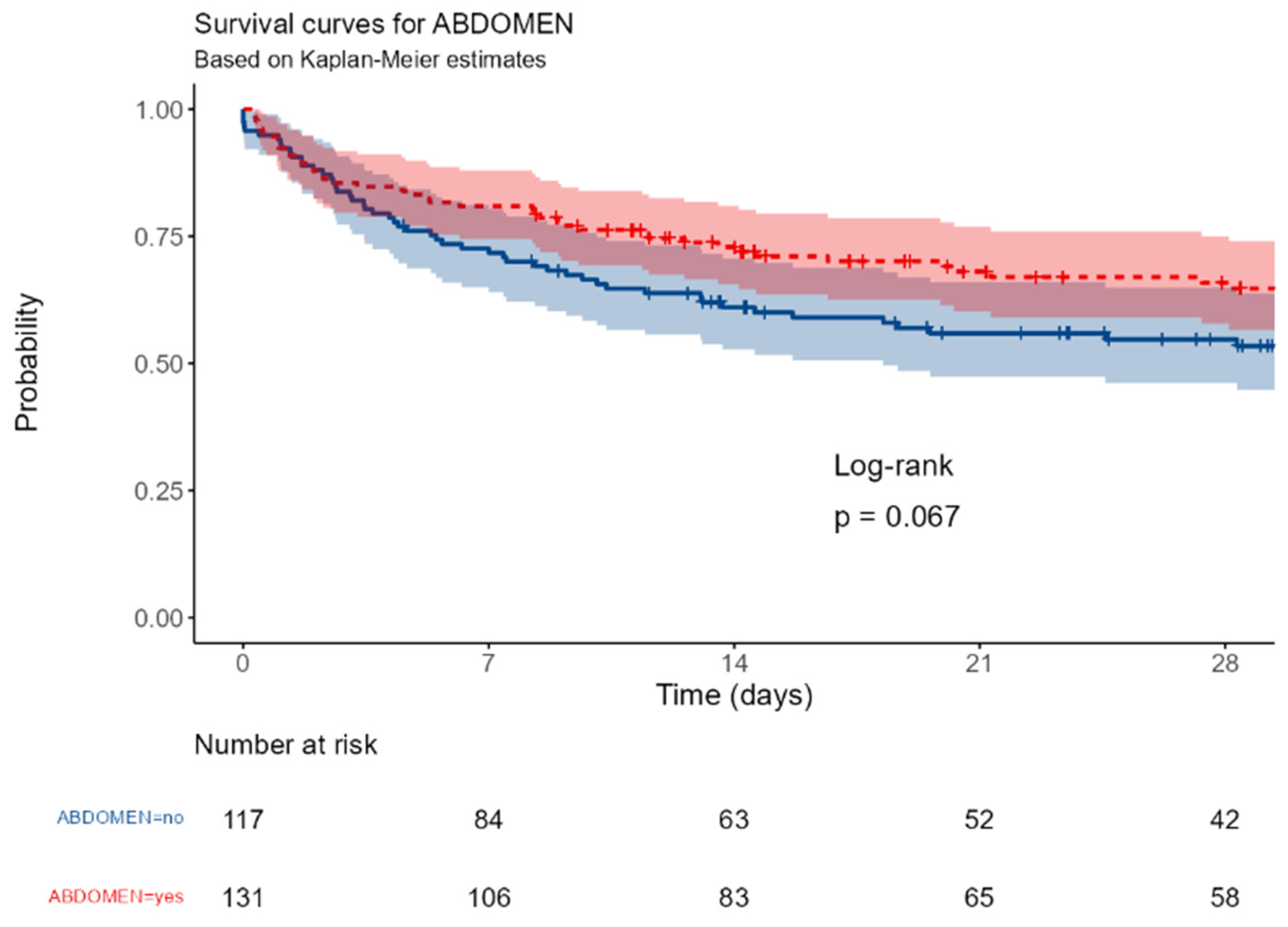

3.2. Insult Criteria

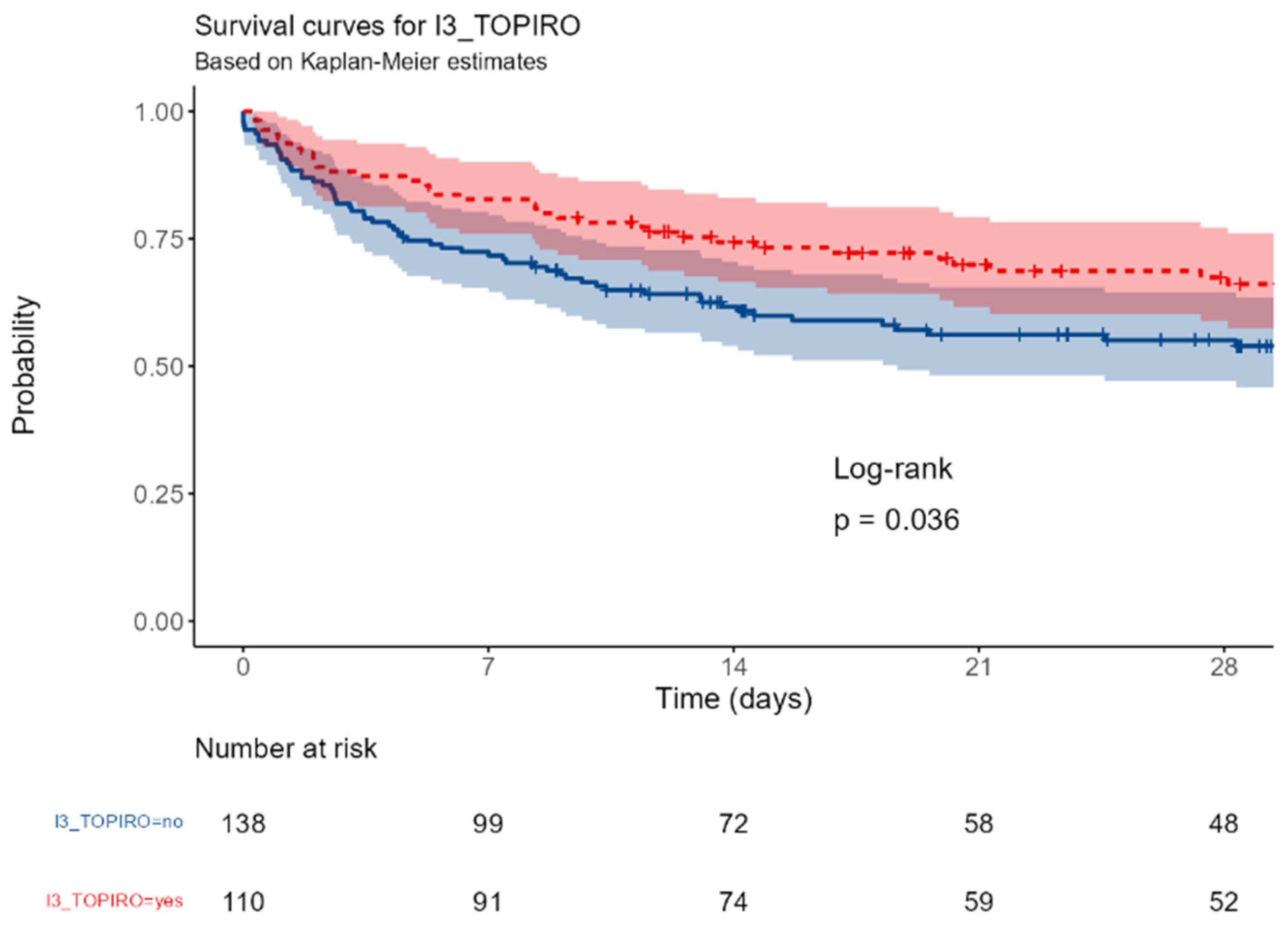

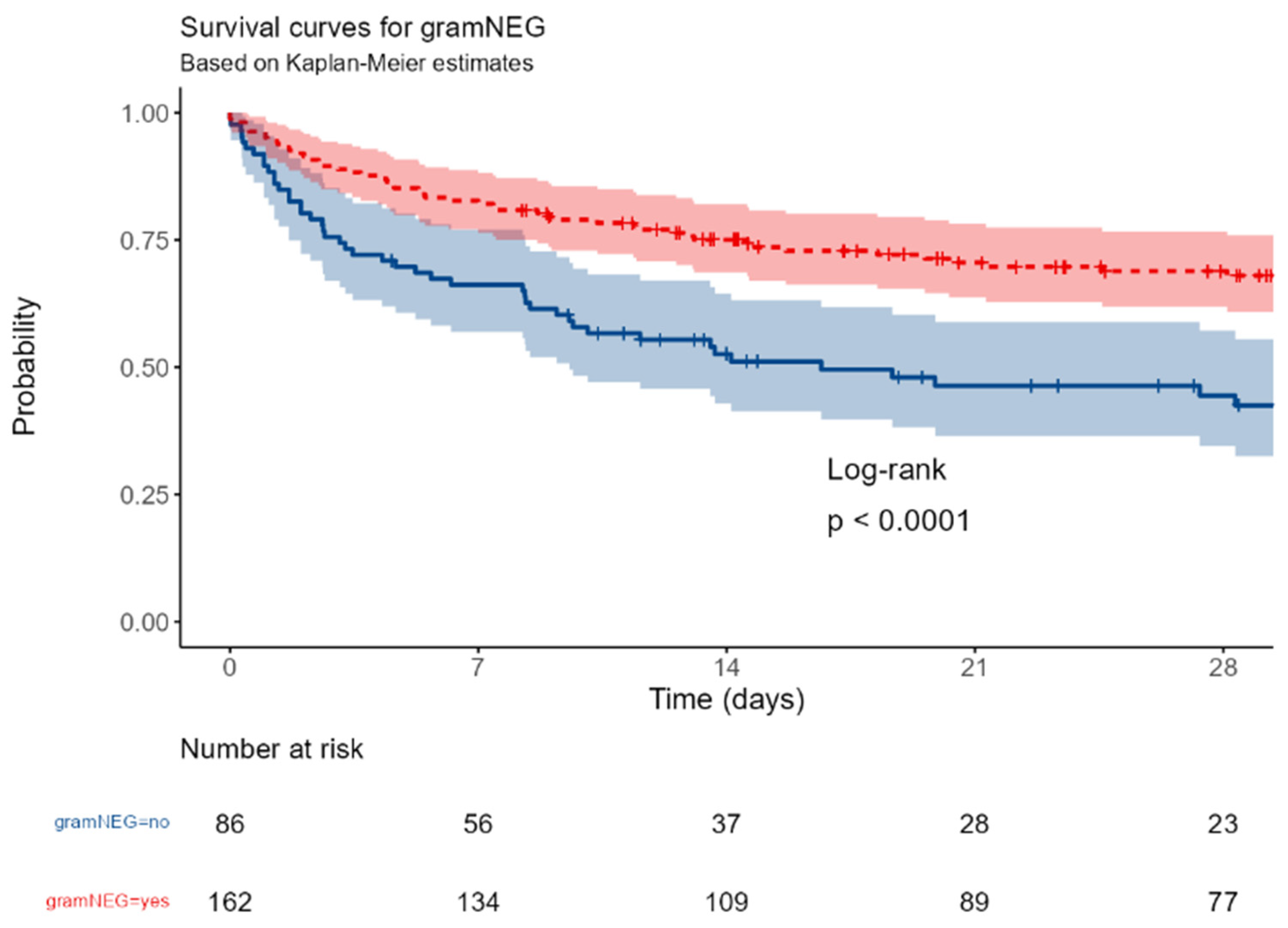

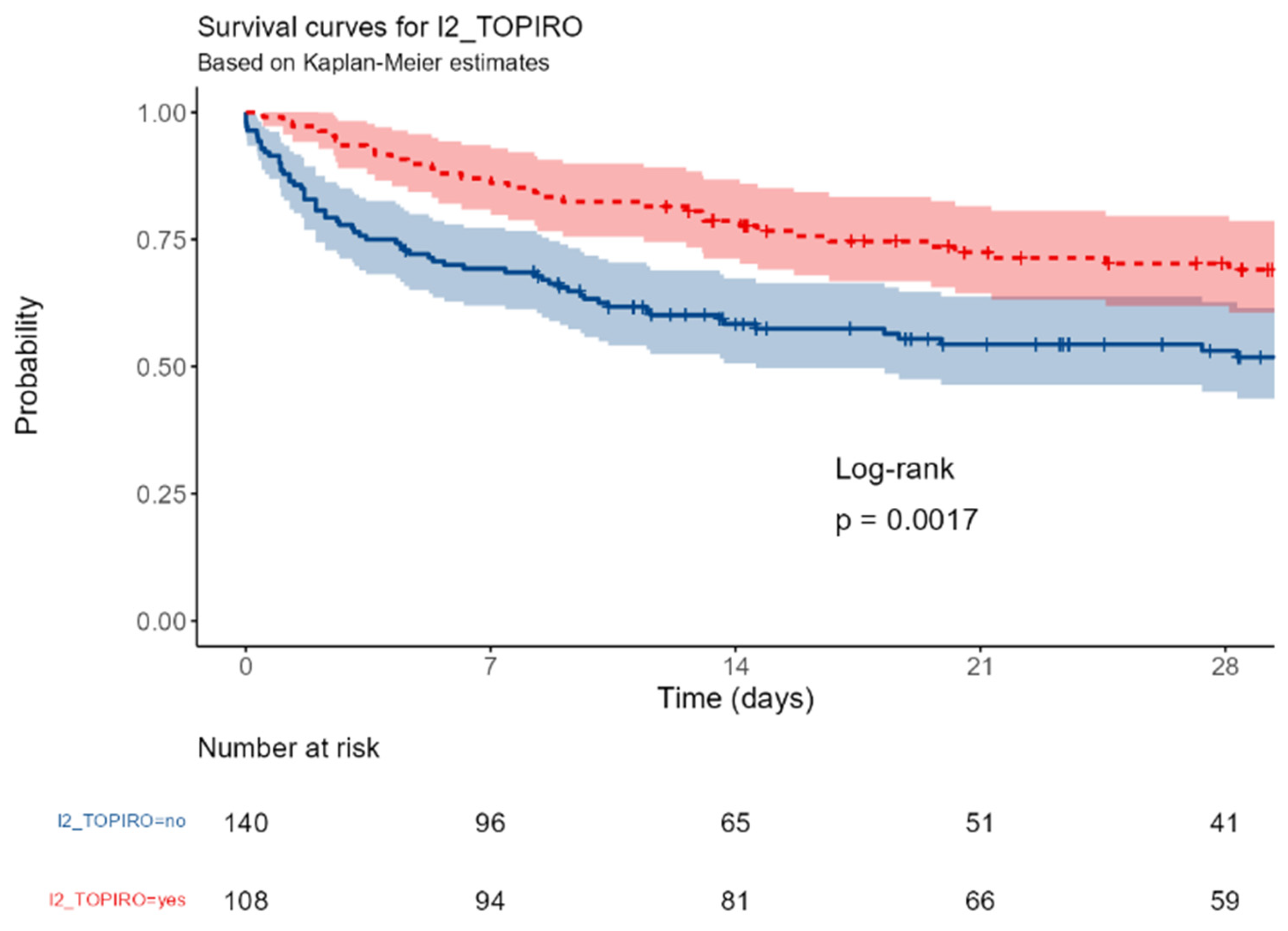

The survival was significantly different between patients with surgical or medical ICU admission (p=0,016); a near-significant better outcome was observed in patients with abdominal vs non-abdominal infections (p=0,067); this trend became significant in patients with primary or secondary peritonitis (p=0,036). The involvement of a gram-negative or of a MDR strain were associated with a better (p<0,0001 and = 0,0017, respectively).

3.3. Response Criteria

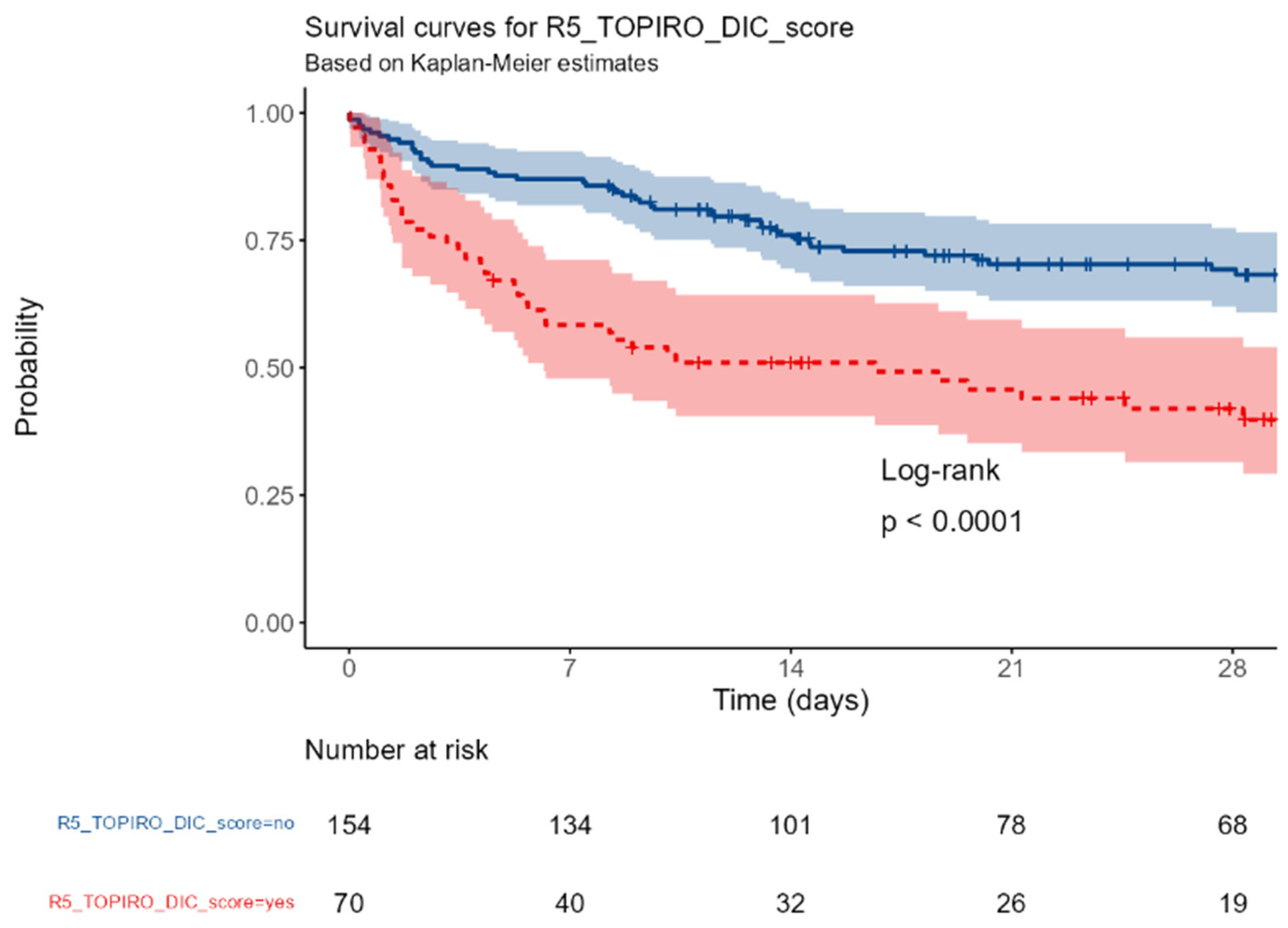

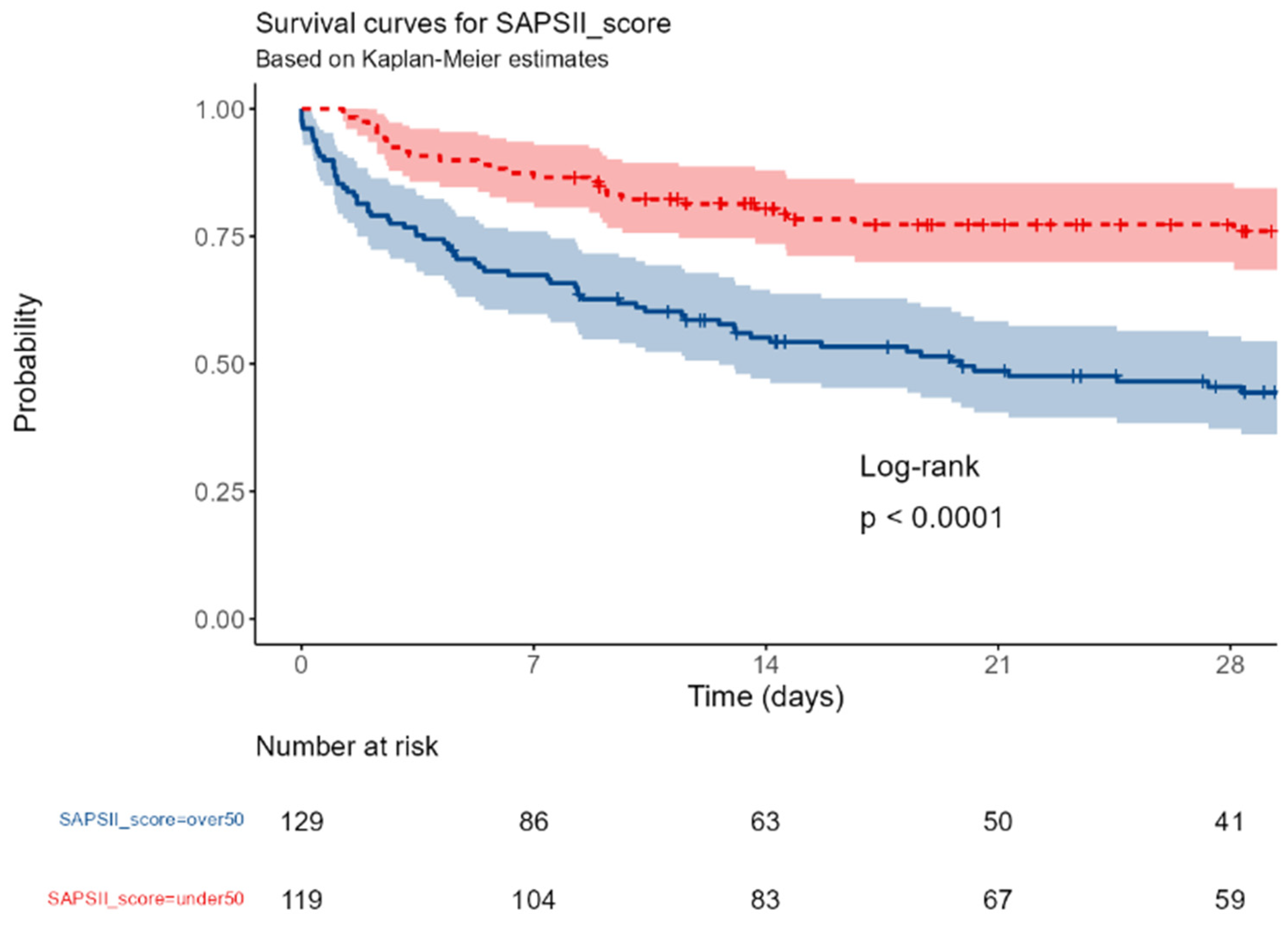

An admission SAPSII score and the presence of SIC were associated with an increased mortality (p< 0.0001); conversely, the baseline IgM values, the PCT and the PCR were not associated with the outcome.

3.4. Organ Criteria

Septic shock and blood lactate levels were not significantly different between survivors and non-survivors (p=0,081 and 0,096, respectively).

3.5. Treatment Criteria

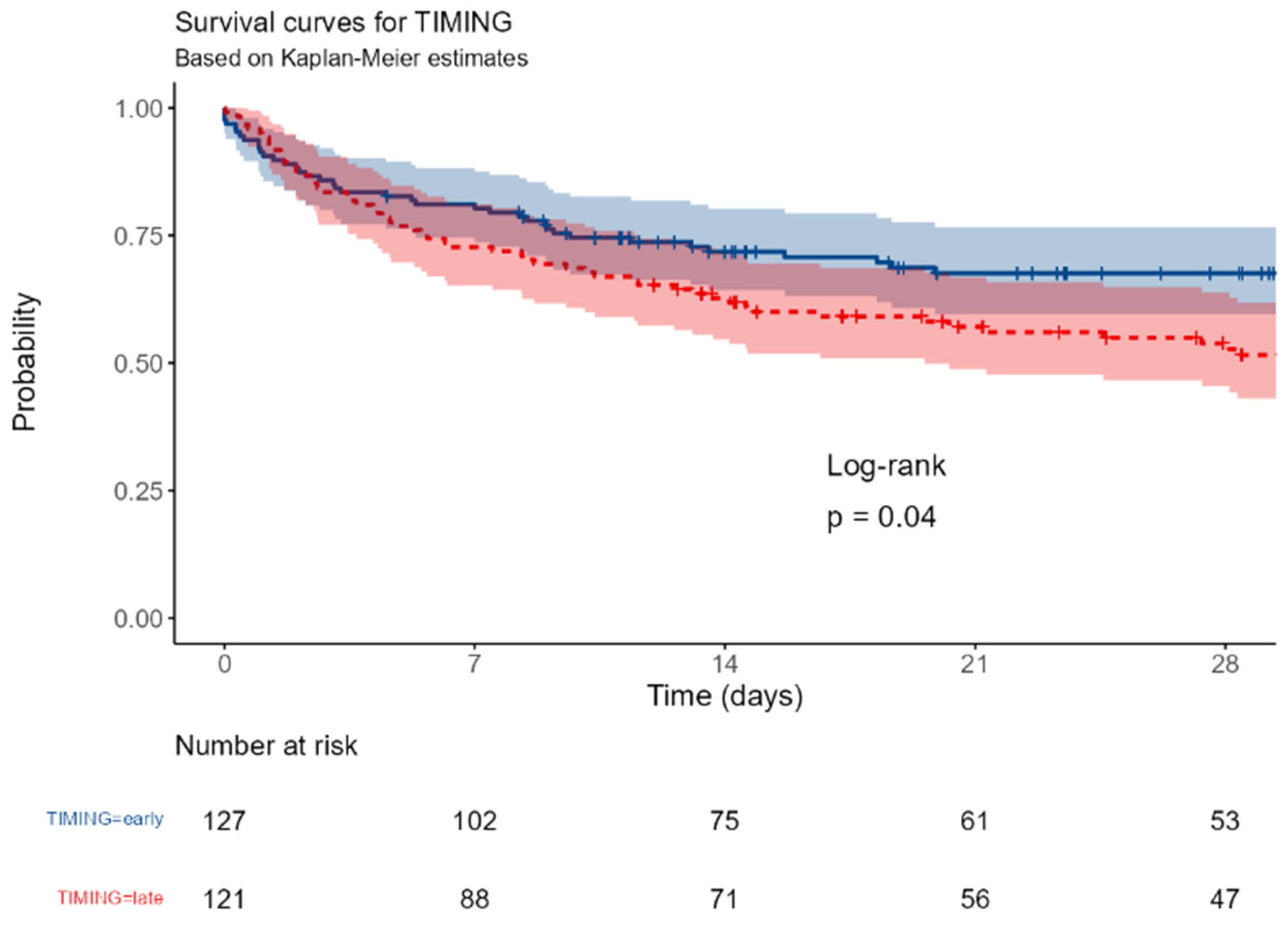

The 28-day and in-hospital survival were significantly better in ES than in LS (p = 0.04 and 0.025, respectively) as well as in the case of appropriate antibiotic therapy (p = 0,021).

3.6. SORRISO-Score Development

The variables of the rTO-PIRO Score resulting significantly or near-significantly different between S and NS in the Kaplan Meyer analysis were weighted according to the ODDS ratio at univariate analysis to develop the SORRISO Score (see

Table 3). The SAPSII score was excluded both because it is an already extensively validated predictor of mortality and because the score is also based on some of the parameters already included individually. It was not possible to include any Organ criteria in the score.

The SORRISO Score is calculated by summing the value of individual items with a range from 0 (worst) to 20.3 (best).

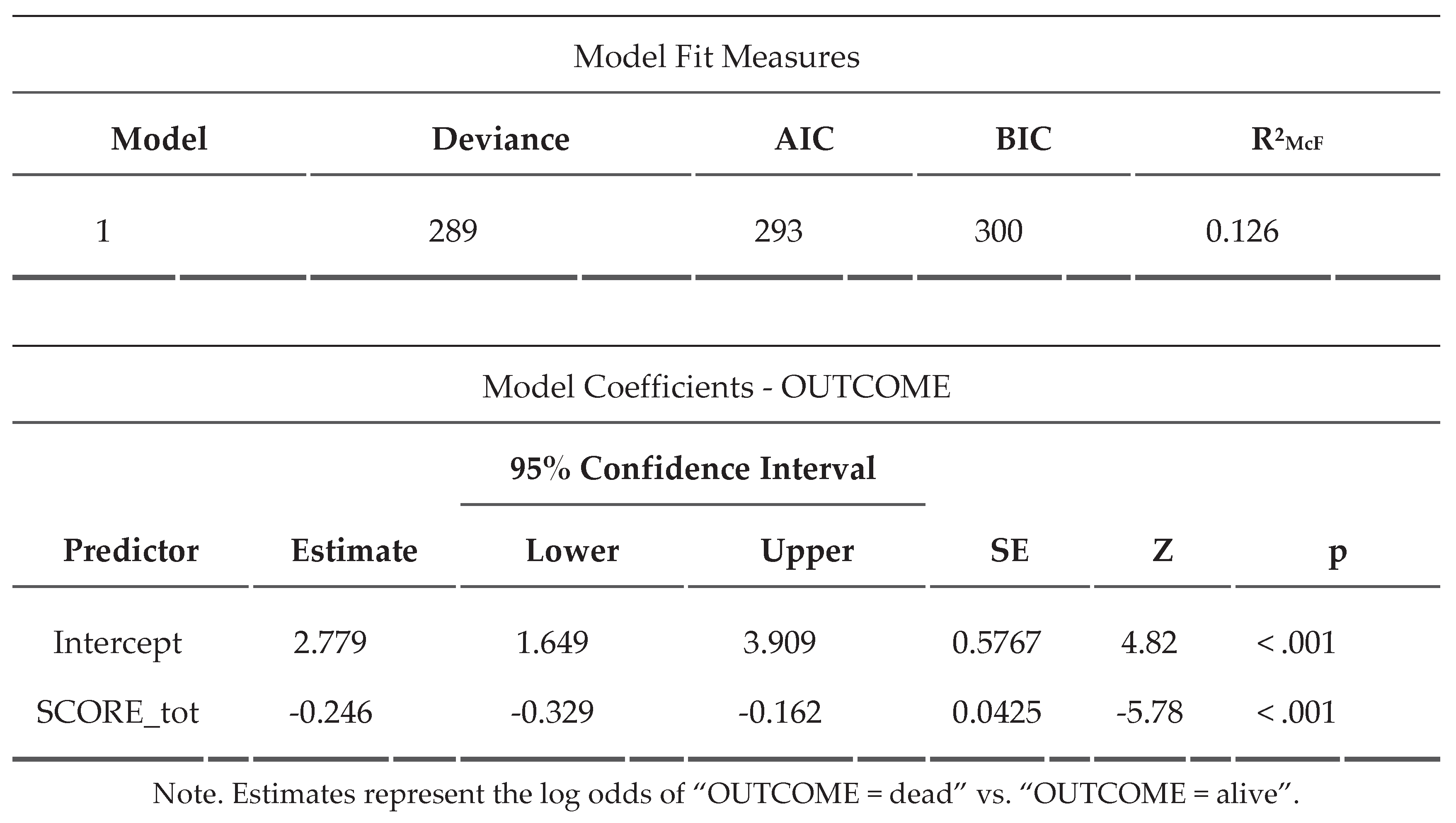

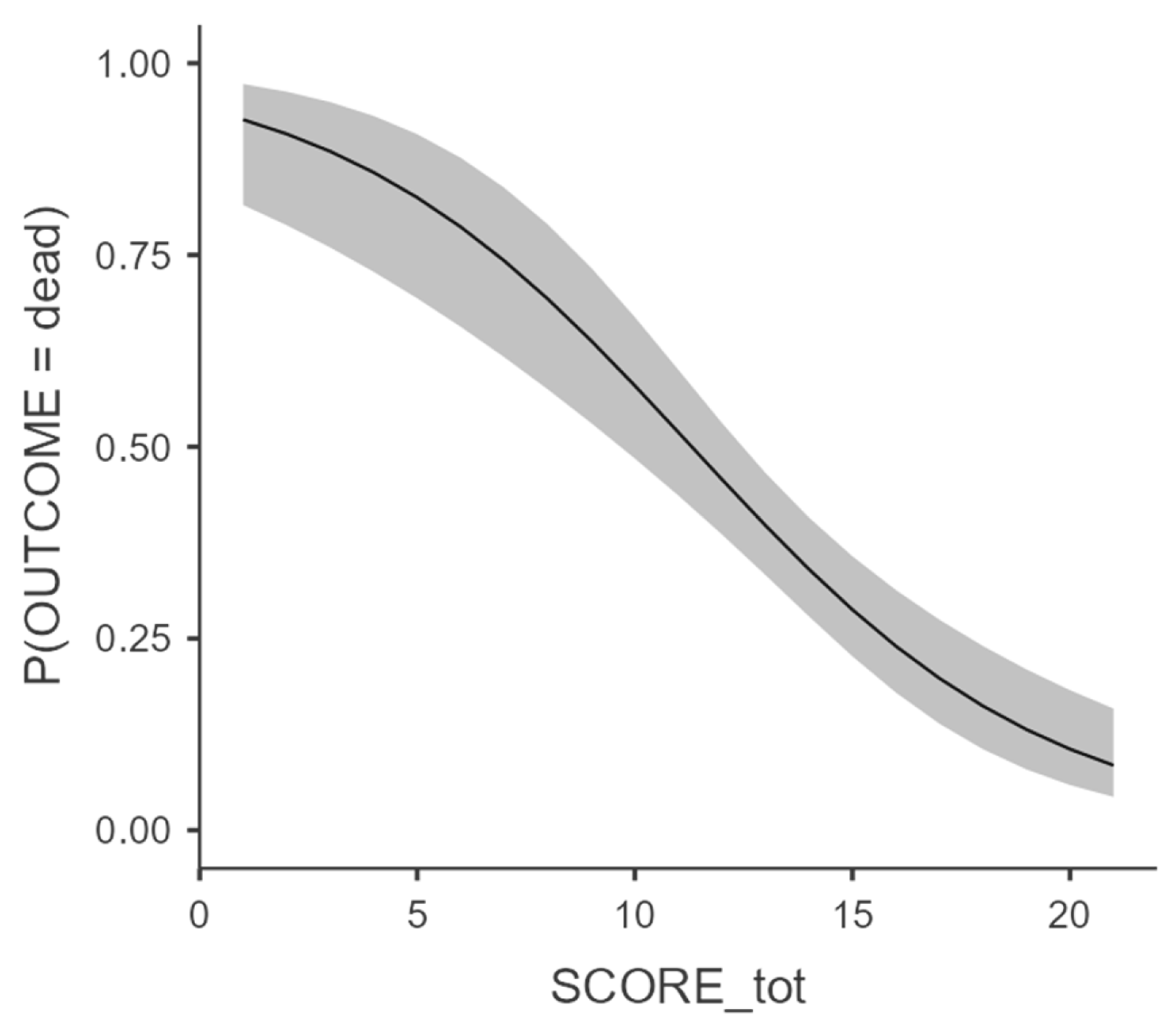

A binomial linear regression with marginal mean estimation (

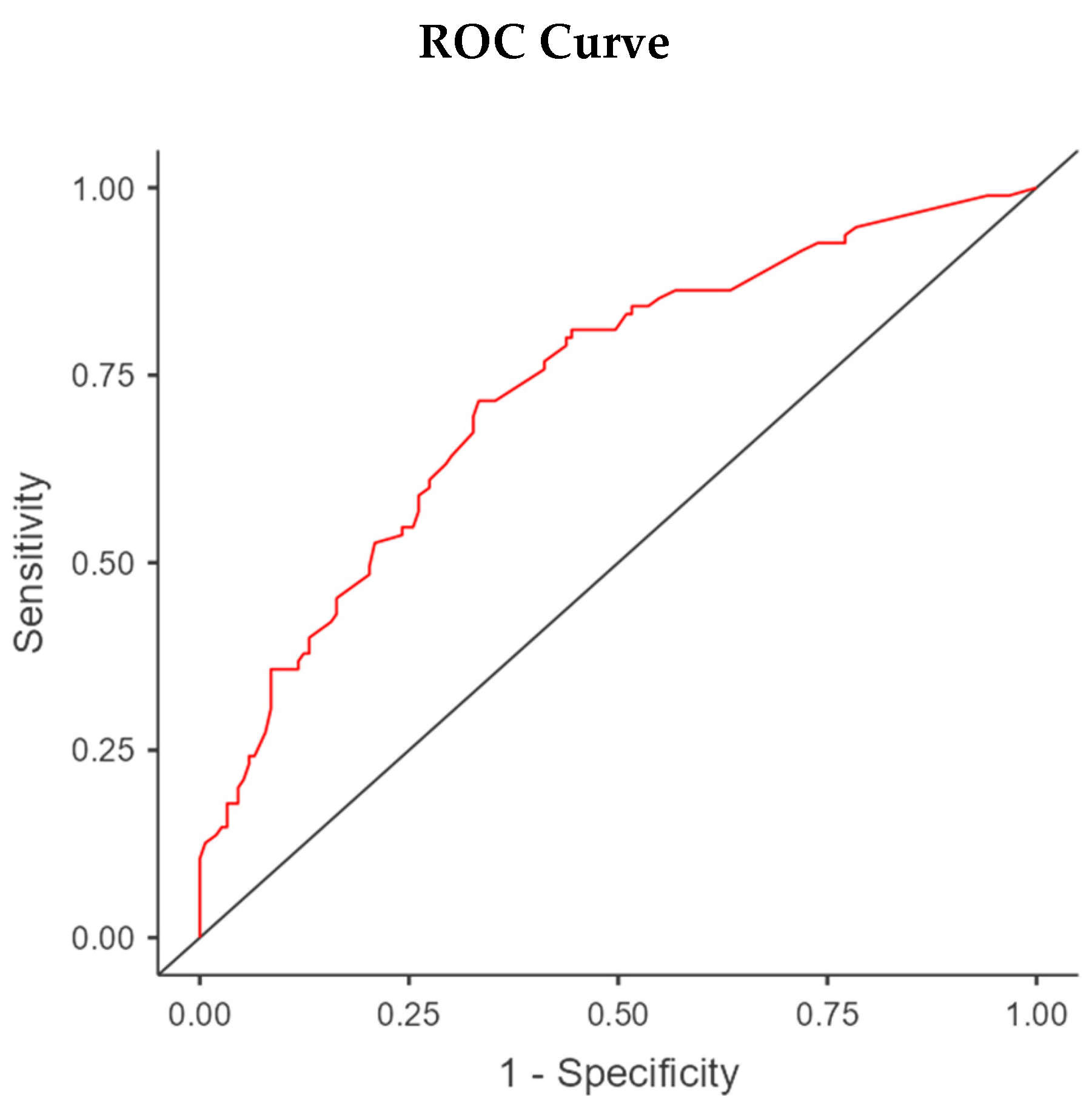

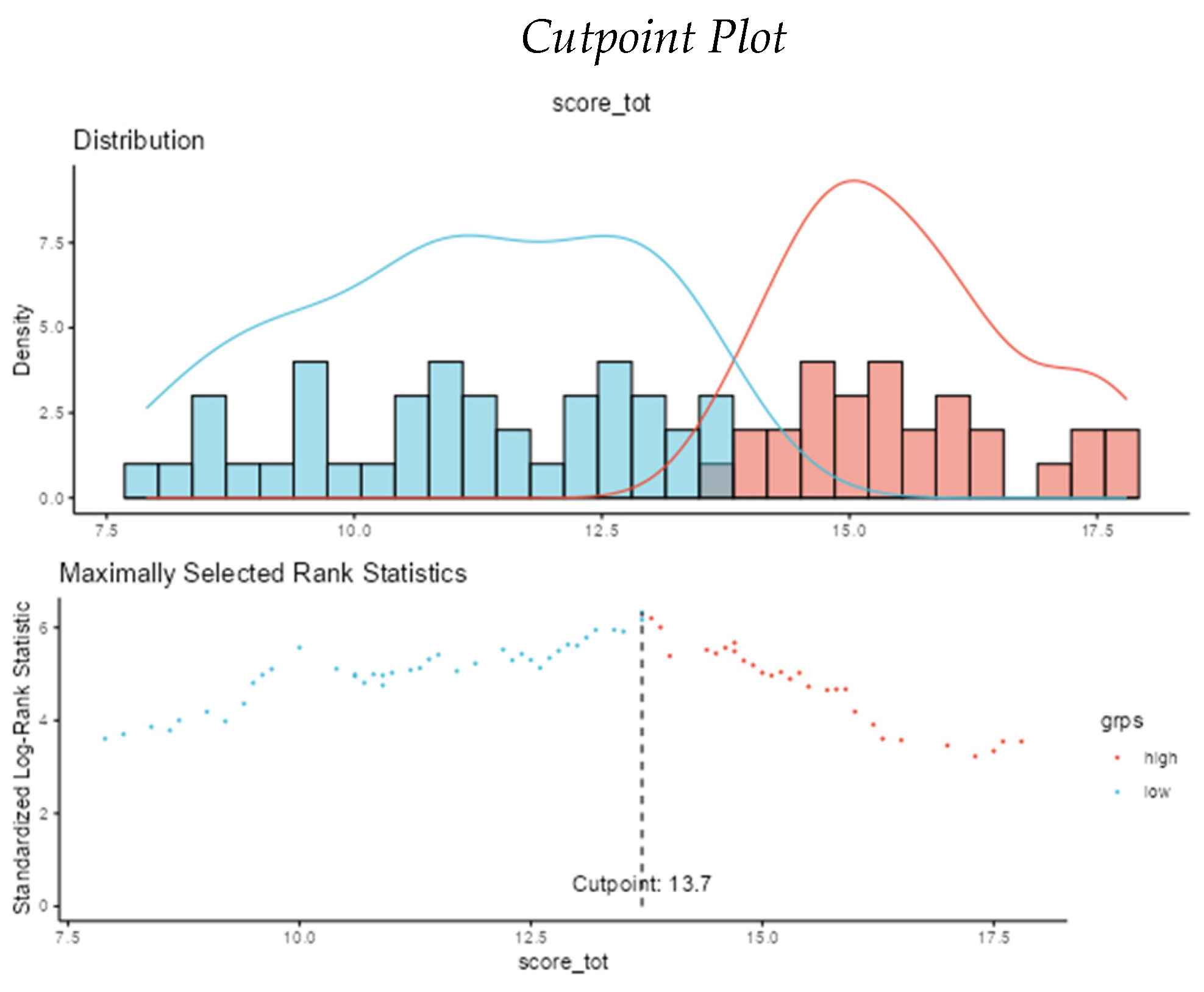

Figure 2) was performed showing an excellent correlation (p<0,001) between the increase in SORRISO-score and the reduction in case fatality.

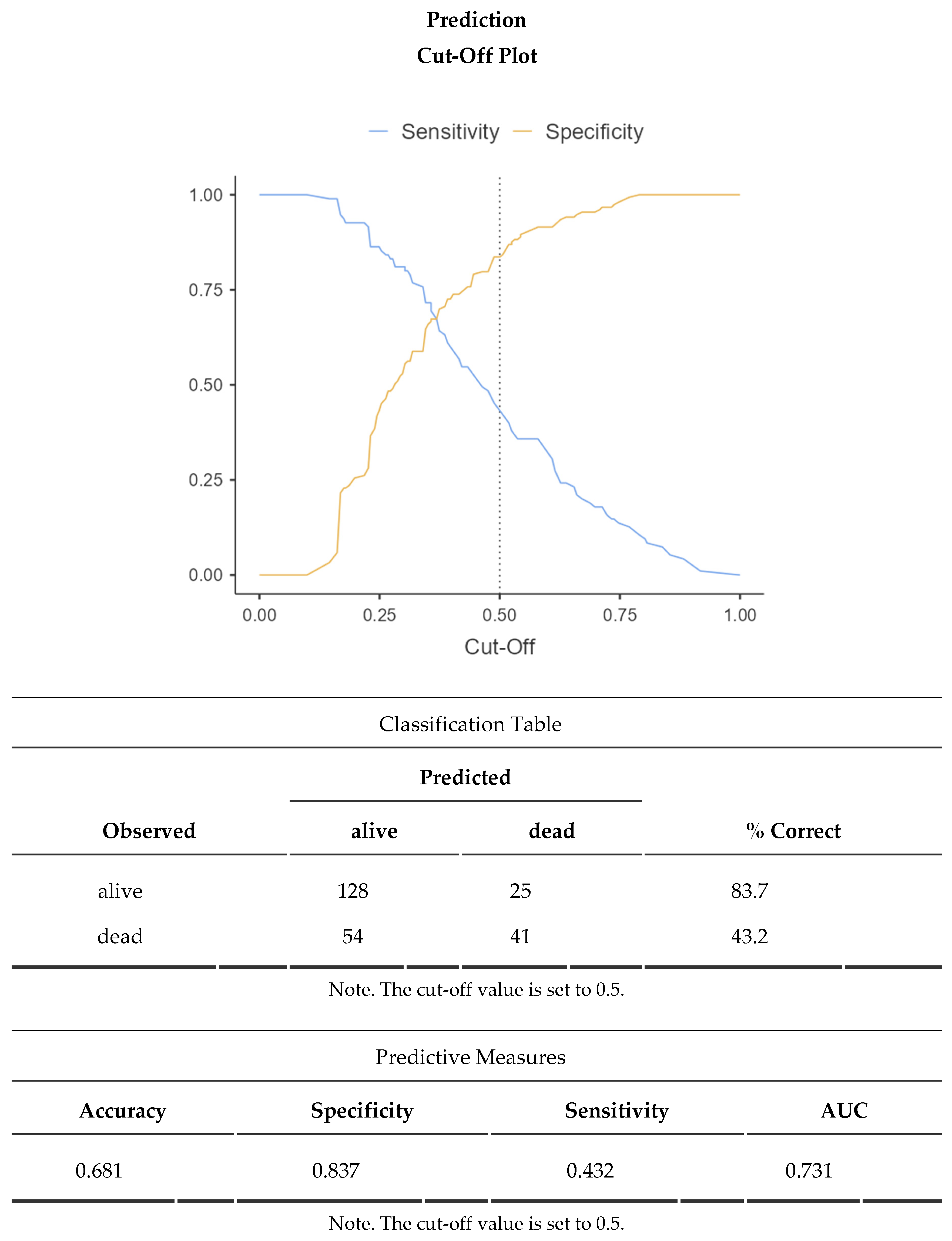

The ideal cut-off for best sensitivity and specificity was then identified as 13,7 points with an appreciable AUC of 0,731 at the ROC curve using a Cox Regression and an Optimal Cut-point Analysis on Jamovi Survival module (see

Appendix A).

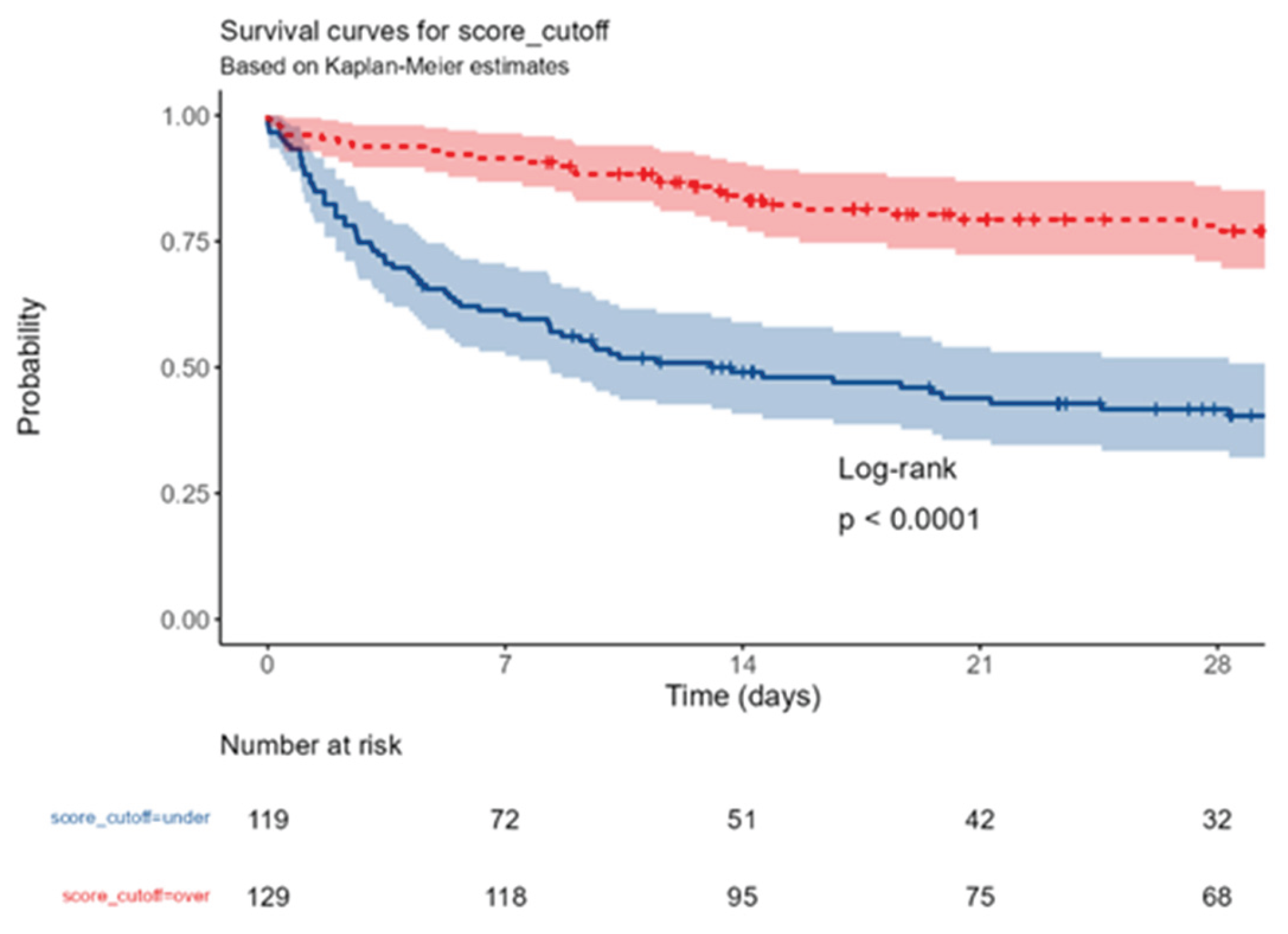

To further confirm the validity of the score and its cut-off, a Kaplan Meyer with high significance (p<0,0001) was produced (

Figure 3).

Considering 28-day mortality the low score group has 57,1% mortality and the high score group has only 20,9% mortality with a clear distinction from the mean value of all patients of 38,3%.

4. Discussion

Despite the opposite indications of SSC, eIg are largely used in septic patients on the basis of a number of studies and MA that demonstrate their efficacy in different subsets of patients [

8,

9,

10] alone or in association with other adjunctive treatments, including BP [

17]; however, the decision for the eIg administration remains somewhat arbitrary due to the lack of precise indications; consequently, their use in septic shock looks more as an act of faith than a rational choice relying on sound scientific bases.

To overcome this too individual approach a number of possible triggers have been suggested that basically can be subdivided in four main categories, each with its own advantages and limitations.

The first consists in the restoration of normal Ig values as low levels have been associated with an increased mortality in septic patients [

7]; however, it is not clear whether in these circumstances, “normal values” of native Ig represents “safe values” or an above-than-normal vales are desirable; should this be the case, their administration could be indicated even in the presence of physiologic levels if Ig.

The second is based on the measurement of the circulating levels of the light λ chains, whose increase indicates the failed production of mature Ig molecules [

18]; even if this approach has a sound biological rationale, it is expensive, requires a prolonged runaround time and could not be available on a 24H/7D basis, thus exceeding the relatively narrow window of opportunity for the eIg.

The third considers some clinical circumstances in which the eIg have been proved to be clinically effective both in the florid phase of sepsis and during the more advanced stage of immunoparalysis [

12].

The fourth uses a score based on expert’s opinion whose final value indicates the opportunity to initiate immediately or to delay the treatment [

15].

We used this last approach as a starting point that was modified by adding some patient and treatment-related variables that differed between S and NS in the SORRISO study. Some of these (i.e., the treatment-free interval, the prevalence of MDR infections etc.) present wide variations among the centers, but these differences are valuable as they reflect better the real-world scenario of a busy ICU than an RCT, in which the patients are enrolled and treated according to a rigid and predetermined protocol.

On the basis of these results, according to the rTO-PIRO score it appears that:

the timing of treatment appears particularly relevant as a longer eIg-free interval has been associated with a worse outcome [

11]; the same applies also for the initiation of an appropriate antibiotic [

19];

surgical patients, even when the infection is caused by MDR strains have a better outcome as compared with medical patients, especially if the site is abdominal (peritonitis) related to gram-negative bacteria;

immunosuppressed patients, independently from the underlying causes and oncologic patients poorly respond to the eIg;

the same consideration applies for patients with SIC, that is considered a consequence of activation of the coagulative cascade by the septic mediators [

13]; among the different items considered in the SORRISO score, it represents the only condition that can be modified by the treatment

The levels of IgM, PCR, and PCT, as well as lactate dosage and norepinephrine requirements, do not appear to be useful trigger criteria for initiating or delaying the administration of eIg.

The subsequent development of the SORRISO Score provides a cut-off value separating patients with different outcomes and thus represents a potential indication for the eIg; however, we guess that the presence of conditions associated with a poor outcome should not elicit a nihilistic attitude and preclude their administration because patients enrolled in the SORRISO study were treated according to the manufacturers’ indications; actually, among the different items used to calculate the SORRISO Score, SIC represents the only modifiable variable, then constituting a potential indicator of the efficacy of the treatment

Our study presents an indication bias constituted by the lack of randomization, as the decision to start eIg was exclusively based on the single center’s experience.

The SORRISO Score is a registry-based proposal, derived and validated in the same cohort, for an explorative tool that must be validated in a greater number of septic patients.

5. Conclusions

The SORRISO score is an explorative tool based on the combination of easily achievable patients- and treatment-related variables and has showed to identify subjects with different profiles of severity and, consequently, different opportunities of taking advantage from the administration of eIg.

Author Contributions

The Board of the SORRISO Project consisting of Giorgio Berlot, Mattia Bixio, Lucia Mirabella, Alessandro Conti, Francesco Forfori, Alberto Noto, Valeria Bonato and Andrea Cortegiani provided conceptualization, methodology, validation, writing-review and editing. Giorgio Berlot played the role of supervision, project administration and writing-original draft preparation. Mattia Bixio and Alberto Noto took care of the software. Lucio Torelli did the statistical analysis and formal analysis. The other authors (Livio Tullo – Anesthesia and Intensive Care Teresa Masselli Mascia Hospital ASL San Severo, Foggia; Montrano Luigi – Anesthesia and Intensive Care, University of Foggia; Luigi Cardia - Division of Anesthesia and Critical Care Department of Human Pathology of the adult and evolutive age “Gaetano Barresi”, University of Messina; Giacomo Castiglione - UO di Rianimazione Ospedale San Marco, Catania; Luca Montagnani - UO Anestesia e Rianimazione, Ospedale Policlinico San Martino – Genova; Serena Spanò, Dipartimento di Patologia Chirurgica Medica Molecolare e dell’Area Critica, Università di Pisa - AOUP ; Maura Camolese, Ilaria Barbaresco, Giulia Moratelli, Beatrice Baso, Michele Contadini, Tatiana Istrati, Giulia Marcer, Christian Ursella, Giorgia Romano - Azienda Sanitaria Universitaria Giulino Isontina Dept. Anesthesia, Intensive Care and Pain Therapy of Trieste) constitute the SORRISO Group who contributed investigation, resources, data collection and curation. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of all centers involved (first approval: protocol code 207 of Ethics Committee of Alessandria, date of approval 4.5.2015).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because GDPR restrictions.

Acknowledgments

We are deeply grateful to the nursing teams of the participating ICUs. Without their valuable and dedicated commitment no study, including the present, could be feasible.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| eIg |

intravenous immunoglobulins enriched with IgA and IgM |

| SORRISO |

Studio Osservazionale Registro Rianimazioni Italiane Sepsi Ospedaliere |

| ICU |

Intensive Care Unit |

| AUC |

Area Under the Curve |

| SCC |

Surviving Sepsis Campaign |

| IvIg |

Intravenous immunoglobulins |

| EBM |

Evidence Based Medicine |

| RCT |

Randomized Clinical Trials |

| ROE |

Rule Of Engagement |

| SIC |

Sepsis-Induced Coagulopathy |

| MDR |

Multiple Drug Resistance |

| BP |

Blood Purification |

| ES |

Early Starters |

| LS |

Late starters |

| S |

Survivors |

| NS |

Non-Survivors |

| PIRO |

Predisposition, Insult, Response, Organ failure |

| MA |

Meta-Analysis |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1 Statistical Analysis with Kaplan-Meier Curves for rTo-PIRO Criteria with p-Values Below 0.05 or Almost Significant Nonetheless Included in the SORRISO Score

Figure A.

P1_TOPIRO (revised): any cancer vs no cancer.

Figure A.

P1_TOPIRO (revised): any cancer vs no cancer.

Figure B.

P3_TOPIRO (revised): Neutropenia or immunosuppressive drugs (monoclonal/steroids/micophenolate/cyclosporin) or allogenic stem cell transplant or splenectomy or AIDS vs none.

Figure B.

P3_TOPIRO (revised): Neutropenia or immunosuppressive drugs (monoclonal/steroids/micophenolate/cyclosporin) or allogenic stem cell transplant or splenectomy or AIDS vs none.

Figure C.

Type of admission: surgical vs medical.

Figure C.

Type of admission: surgical vs medical.

Figure D.

Site of infection: abdomen vs others.

Figure D.

Site of infection: abdomen vs others.

Figure E.

I3_TOPIRO: Secondary/tertiary peritonitis vs none.

Figure E.

I3_TOPIRO: Secondary/tertiary peritonitis vs none.

Figure F.

positive culture isolation: gram negative bacteria vs none.

Figure F.

positive culture isolation: gram negative bacteria vs none.

Figure G.

I2_TOPIRO: MDR infections or nosocomial infections.

Figure G.

I2_TOPIRO: MDR infections or nosocomial infections.

Figure H.

R5_TOPIRO (revised): Disseminated intravascular coagulation vs none.

Figure H.

R5_TOPIRO (revised): Disseminated intravascular coagulation vs none.

Figure I.

SAPSII score: under 50 vs over 50.

Figure I.

SAPSII score: under 50 vs over 50.

Figure L.

Timing of eIg infusion (72 hours): early vs late.

Figure L.

Timing of eIg infusion (72 hours): early vs late.

Figure M.

Adequacy of antibiotic therapy: yes vs no.

Figure M.

Adequacy of antibiotic therapy: yes vs no.

Appendix A.2 Binomial Logistic Regression for the Calculation of the SORRISO Score

Appendix A.3 Cox Regression Summary and Table for the Calculation of the SORRISO Score Cut-Off

When SCORE_tot increases 1 unit, the hazard increases 0.85 (0.81-0.89, p<0.001) times.

| Explanatory |

Levels |

all |

HR (Univariable) |

HR (Multivariable) |

| . |

Mean (SD) |

13.5 (3.8) |

0.85 (0.81-0.89, p<0.001) |

0.85 (0.81-0.89, p<0.001) |

Model Metrics: Number in dataframe = 248, Number in model = 248, Missing = 0, Number of events = 110, Concordance = 0.696 (SE = 0.025), R-squared = 0.165(Max possible = 0.988), Likelihood ratio test = 44.842 (df = 1, p = 0.000)

| Cut Point |

Statistic |

| 13.7 |

6.33 |

References

- Evans L, Rhodes A, Alhazzani W, Antonelli M, Coopersmith CM, French C, Machado FR, Mcintyre L, Ostermann M, Prescott HC, Schorr C, Simpson S, Wiersinga WJ, Alshamsi F, Angus DC, Arabi Y, Azevedo L, Beale R, Beilman G, Belley-Cote E, Burry L, Cecconi M, Centofanti J, Coz Yataco A, De Waele J, Dellinger RP, Doi K, Du B, Estenssoro E, Ferrer R, Gomersall C, Hodgson C, Møller MH, Iwashyna T, Jacob S, Kleinpell R, Klompas M, Koh Y, Kumar A, Kwizera A, Lobo S, Masur H, McGloughlin S, Mehta S, Mehta Y, Mer M, Nunnally M, Oczkowski S, Osborn T, Papathanassoglou E, Perner A, Puskarich M, Roberts J, Schweickert W, Seckel M, Sevransky J, Sprung CL, Welte T, Zimmerman J, Levy M. Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock 2021. Intensive Care Med. 2021 Nov;47(11):1181-1247. . Epub 2021 Oct 2. PMID: 34599691; PMCID: PMC8486643. [CrossRef]

- Almansa R, Tamayo E, Andaluz-Ojeda D, Nogales L, Blanco J, Eiros JM, Gomez-Herreras JI, Bermejo-Martin JF. The original sins of clinical trials with intravenous immunoglobulins in sepsis. Crit Care. 2015 Feb 26;19(1):90. . PMID: 25882822; PMCID: PMC4343266. [CrossRef]

- Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, Shankar-Hari M, Annane D, Bauer M, Bellomo R, Bernard GR, Chiche JD, Coopersmith CM, Hotchkiss RS, Levy MM, Marshall JC, Martin GS, Opal SM, Rubenfeld GD, van der Poll T, Vincent JL, Angus DC. The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA. 2016 Feb 23;315(8):801-10. . PMID: 26903338; PMCID: PMC4968574. [CrossRef]

- Ehrenstein MR, Notley CA: The importance of natural IgM: scavenger, protector and regulator. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010; 10 :778-86.

- Giamarellos-Bourboulis EJ, Apostolidou E, LadaM. Kinetics of circulating immunoglobulin M in sepsis: relationship with final outcome. Crit Care. 2013;17: R247-256.

- Bermejo-Martín JF, Rodriguez-Fernandez A, Herrán-Monge R, Andaluz-Ojeda D, Muriel-Bombín A, Merino P, García-García MM, Citores R, Gandía F, Almansa R, Blanco J; GRECIA Group (Grupo de Estudios y Análisis en Cuidados Intensivos). Immunoglobulins IgG1, IgM and IgA: a synergistic team influencing survival in sepsis. J Intern Med. 2014 Oct;276(4):404-12. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24815605.

- Krautz C, Maier SL, Brunner M, Langheinrich M, Giamarellos-Bourboulis EJ, Gogos C, Armaganidis A, Kunath F, Grützmann R, Weber GF. Reduced circulating B cells and plasma IgM levels are associated with decreased survival in sepsis - A meta-analysis. J Crit Care 2018;45:71–5. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29413726.

- Busani S, Damiani E, Cavazzuti I, Donati A, Girardis M. Intravenous immunoglobulin in septic shock: review of the mechanisms of action and meta-analysis of the clinical effectiveness. Minerva Anestesiol. 2016 May;82(5):559-72. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26474267.

- Cui J, Wei X, Lv H, Li Y, Li P, Chen Z, Liu G. The clinical efficacy of intravenous IgM-enriched immunoglobulin (pentaglobin) in sepsis or septic shock: a meta-analysis with trial sequential analysis. Ann Intensive Care 2019;9(1):27. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30725235.

- Pan B, Sun P, Pei R, Lin F, Cao H. Efficacy of IVIG therapy for patients with sepsis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Transl Med. 2023 Oct 28;21(1):765. . PMID: 37898763; PMCID: PMC10612304. [CrossRef]

- Berlot G, Vassallo MC, Busetto N, Nieto Yabar M, Istrati T, Baronio S, Quarantotto G, Bixio M, Barbati G, Dattola R, Longo I, Chillemi A, Scamperle A, Iscra F, Tomasini A. Effects of the timing of administration of IgM- and IgA-enriched intravenous polyclonal immunoglobulins on the outcome of septic shock patients. Ann Intensive Care. 2018 Dec 10;8(1):122. . Erratum in: Ann Intensive Care. 2019 Mar 5;9(1):33. PMID: 30535962; PMCID: PMC6288102. [CrossRef]

- Nierhaus A, Berlot G, Kindgen-Milles D, Müller E, Girardis M. Best-practice IgM- and IgA-enriched immunoglobulin use in patients with sepsis. Ann Intensive Care. 2020 Oct 7;10(1):132. . PMID: 33026597; PMCID: PMC7538847. [CrossRef]

- Iba T, Umemura Y, Wada H, Levy JH. Roles of Coagulation Abnormalities and Microthrombosis in Sepsis: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Arch Med Res. 2021 Nov;52(8):788-797. . Epub 2021 Jul 31. PMID: 34344558. [CrossRef]

- Macesic N, Uhlemann AC, Peleg AY. Multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacterial infections. Lancet. 2025 Jan 18;405(10474):257-272. . PMID: 39826970. [CrossRef]

- De Rosa FG, Corcione S, Tascini C, Pasero D, Rocchetti A, Massaia M, Berlot G, Solidoro P, Girardis M. A Position Paper on IgM-Enriched Intravenous Immunoglobulin Adjunctive Therapy in Severe Acute Bacterial Infections: The TO-PIRO SCORE Proposal. New Microbiol. 2019 Jul;42(3):176-180. Epub 2019 Jun 3. PMID: 31157400.

- Marshall JC. The PIRO (predisposition, insult, response, organ dysfunction) model: toward a staging system for acute illness. Virulence. 2014 Jan 1;5(1):27-35. . Epub 2013 Nov 1. PMID: 24184604; PMCID: PMC3916380. [CrossRef]

- Paternoster G, De Rosa S, Bertini P, Innelli P, Vignale R, Tripodi VF, Buscaglia G, Vadalà M, Rossi M, Arena A, Demartini A, Tripepi G, Abelardo D, Pittella G, Di Fazio A, Scolletta S, Guarracino F, de Arroyabe BML. Comparative Effectiveness of Combined IgM-Enriched Immunoglobulin and Extracorporeal Blood Purification Plus Standard Care Versus Standard Care for Sepsis and Septic Shock after Cardiac Surgery. Rev Cardiovasc Med. 2022 Sep 14;23(9):314. . PMID: 39077704; PMCID: PMC11262381. [CrossRef]

- Shankar-Hari M, Singer M, Spencer J. Can Concurrent Abnormalities in Free Light Chains and Immunoglobulin Concentrations Identify a Target Population for Immunoglobulin Trials in Sepsis? Crit Care Med. 2017 Nov;45(11):1829-1836. . PMID: 28742550. [CrossRef]

- Van Heuverswyn J, Valik JK, Desirée van der Werff S, Hedberg P, Giske C, Nauclér P. Association Between Time to Appropriate Antimicrobial Treatment and 30-day Mortality in Patients With Bloodstream Infections: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Clin Infect Dis. 2023 Feb 8;76(3):469-478. . PMID: 36065752; PMCID: PMC9907509. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).