1. Introduction

The dark web, commonly accessed via specialized networks like Tor and I2P, presents significant challenges for cybersecurity due to its anonymous and unregulated nature. While advanced security tools increasingly protect the surface web, the darknet remains a haven for illicit activities, ranging from illegal marketplaces to ransomware communications. As cyber threats become more sophisticated, the need for accurate and granular classification of darknet traffic grows urgently. Despite a growing body of research in this field, progress is limited by the lack of comprehensive, labeled datasets tailored specifically for darknet traffic behaviors and types.

Existing datasets, such as CIC-Darknet2020 and CTU-13, often have limitations, including a lack of class diversity, inadequate labeling, and restricted availability of raw traffic data. Moreover, many focus primarily on detection—merely distinguishing between normal and malicious traffic—without addressing the nuanced classification of darknet traffic into distinct behavioral categories. This limitation hampers the development of robust machine learning models capable of detecting darknet activity and understanding its underlying patterns.

To address these gaps, we present a novel darknet dataset specifically designed for traffic classification. The dataset was constructed by capturing real-world darknet traffic across multiple machine environments, including physical and virtual systems operating on conventional networks. Each type of darknet behavior was intentionally invoked and recorded to ensure the traffic's authenticity, and labeling was performed accordingly. This process yielded a diverse and well-structured dataset for traffic detection, behavior-based classification, and pattern analysis.

In addition to its comprehensiveness, the dataset has been evaluated using several machine learning models, demonstrating high classification accuracy (exact values to be inserted). The dataset is also intended for public release, offering researchers a valuable resource for advancing darknet traffic analysis. This work contributes a foundational asset for future research and developing more precise cybersecurity tools by bridging the gap between detection and detailed classification.

Darknet traffic detection and classification have received increasing attention in recent years, particularly with the rise of encrypted and decentralized communication platforms. Various studies have explored protocol-specific behaviors, developed classification models, and constructed datasets to identify darknet-related activities. However, existing efforts regarding behavioral diversity, platform scope, or real-world applicability are often limited.

1.1. Datasets and Traffic Classification Models

Several studies have utilized existing darknet datasets or created new ones to train machine learning models for traffic detection and classification. In [1], the authors focused on classifying Tor traffic using time-related features like flow duration and inter-arrival time. By employing a Random Forest (RF) model on the UNB-CIC Tor network traffic dataset, they achieved a classification accuracy of 98% between Tor and non-Tor flows. In [2], the authors proposed a machine learning-based intrusion detection system for IoT networks using the CIC-Darknet2020 dataset. They evaluated six supervised algorithms and found that BAG-DT achieved the highest accuracy of 99.5%, indicating the effectiveness of ensemble models for darknet detection. A more comprehensive multi-platform approach was taken. [3], where the authors created a custom dataset that includes traffic from Tor, I2P, ZeroNet, and Freenet. They applied both flat and hierarchical classification techniques using CICFlowMeter-extracted features. Among various models tested—such as XGBDT, LightGBM, MLP, and LSTM—XGBDT achieved the highest performance with an accuracy of 99.42% in darknet behavior classification. This work demonstrated strong model performance but used a limited feature set (26 features), which may restrict fine-grained behavior analysis. In [4], a novel deep learning system called Tor-VPN Detector was proposed to classify darknet traffic into four categories: Tor, non-Tor, VPN, and non-VPN. Using the DIDarknet dataset, which contains over 141,000 samples and 79 flow-level features, the authors trained a six-layer deep neural network that achieved a 96% accuracy and 96.06% F1-score, without requiring preprocessing or balancing techniques.

1.2. Protocol-Specific Behavioral Analysis

Beyond detection accuracy, some studies have explored specific darknet technologies in greater technical and behavioral detail. In [5], the authors analyzed Tor artifacts on Windows 11 systems, proposing a virtual lab setup to simulate cyberattacks and generate traffic for forensic and machine learning research. Although methodologically strong, this work emphasized operating system traces more than network flow analysis.

In [6], the researchers studied the architecture and mechanisms of the I2P protocol, including NTCP communication, AES-256 encryption, and tunnel routing. They used Tranalyzer2 to extract flow features and tested multiple supervised classifiers, finding Random Forest the most effective. However, their focus remained largely on technical protocol behavior rather than creating a reusable dataset.

Study [7] Focused on ZeroNet architecture and its robustness challenges, highlighting its dependency on centralized trackers and proposing peer-exchange improvements. While useful for understanding platform limitations, the work did not include traffic classification or dataset contributions.

1.3. Foundational and Contextual Studies

In [8], a broader perspective on the dark web’s dual-use nature was provided, emphasizing its legitimate role in preserving privacy and anonymity and its risks in enabling criminal activity. The study reinforces the need for advanced detection tools and datasets to support privacy-preserving and threat-identifying research.

1.4. Gaps in Existing Work

Despite these efforts, current studies often fail to capture the behavioral diversity and multi-protocol coverage required for robust darknet traffic analysis. Most datasets are centered on a single platform (e.g., Tor) and focus on binary detection tasks (darknet vs. non-darknet), leaving a resource gap that enables behavior-level classification across multiple darknet ecosystems.

1.5. Contribution of This Work

The

SafeSurf Darknet 2025 dataset addresses these limitations by introducing a behaviorally labeled, flow-based dataset encompassing five key technologies:

Tor, I2P, Freenet, ZeroNet, and VPN. It includes

79 flow-level features and labels corresponding to user behaviors (e.g., email, chat, file transfer, video streaming), making it suitable for multi-class classification, behavior profiling, and anomaly detection. In contrast to prior datasets, it emphasizes

diversity and

structure, offering a practical resource for researchers and practitioners aiming to understand or secure darknet environments [

8].

1.6. Paper Structure

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 outlines the methodology and data collection procedures used in building the dataset.

Section 3 details the dataset’s structure and labeling approach.

Section 4 discusses the evaluation results using machine learning models. Finally,

Section 5 concludes the paper and outlines potential future directions.

2. Dataset Description

2.1. Dataset Collection Methodology

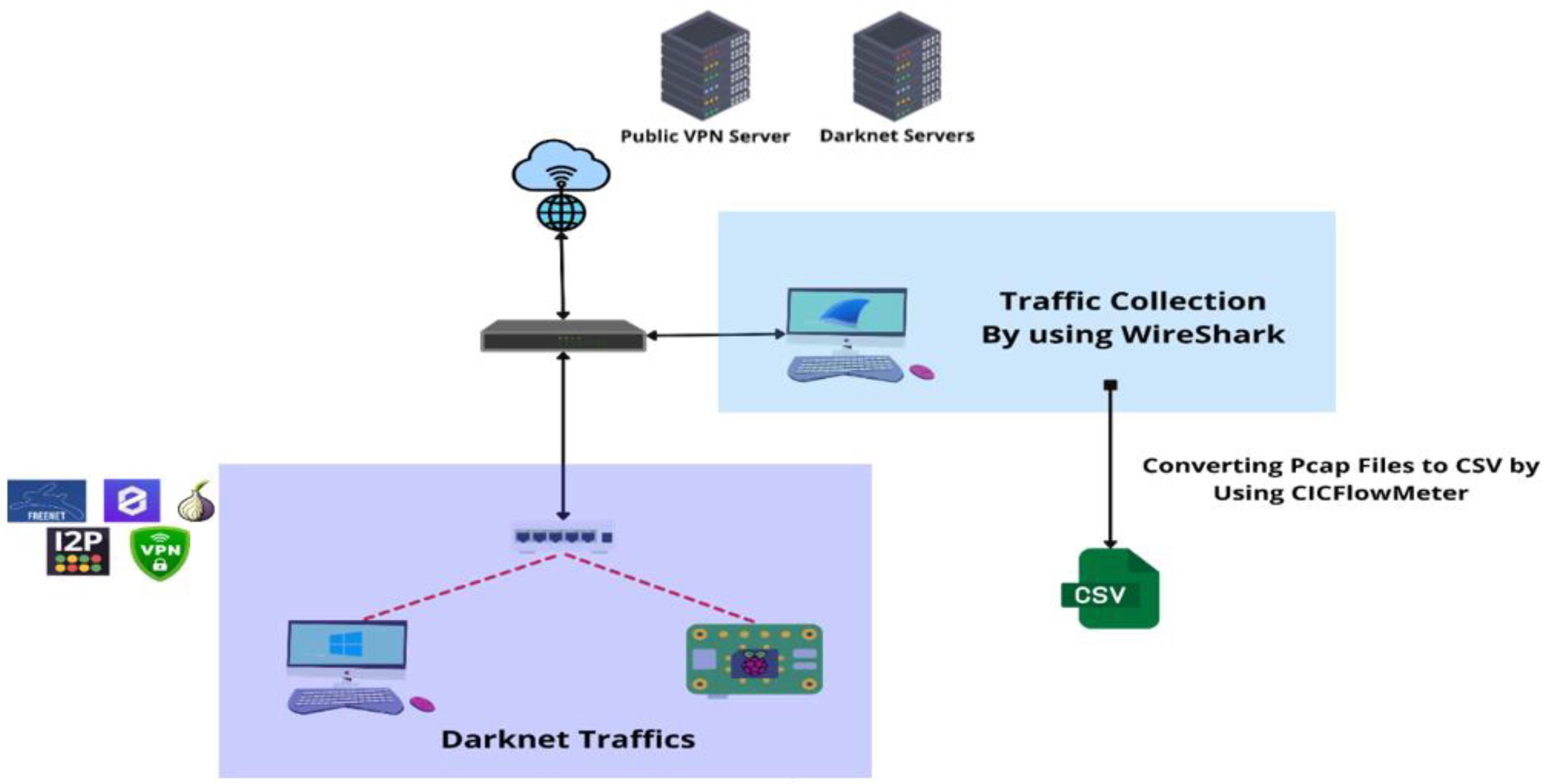

We run darknet activity on a Raspberry Pi device and multiple virtual machine environments to develop a comprehensive and realistic darknet traffic dataset. Traffic was captured using Wireshark and then processed using CICFlowMeter to convert raw Pcap files into structured flow-based CSV data with 79 extracted features per flow. This methodology ensured depth and structure, facilitating machine learning applications such as classification and anomaly detection.

Figure 1.

Dataset Capture Methodology.

Figure 1.

Dataset Capture Methodology.

Multiple platforms and protocols representing diverse darknet behaviors were used in data collection. These included:

Tor (The Onion Router): We configured Tor on a Raspberry Pi 5 (Kali Linux), Windows machines, and Azure-based VPNs. Behaviors captured included web browsing, email via Thunderbird (through proxychains), chatting and VoIP via Telegram, file transfers, audio, and video streaming (including YouTube).

Freenet: We used the Freenet platform to simulate browsing, file sharing, chatting (via FMS), video streaming (via FreeTube), and decentralized email (via Web of Trust).

ZeroNet: Deployed on a Windows 10 environment, this protocol allowed the collection of traffic related to ZeroMail, ZeroChat, ZeroTube, decentralized file transfers (IFS), and general browsing behaviors through peer-to-peer hosting.

VPN: An OpenVPN server was deployed on Microsoft Azure to simulate encrypted communication and traffic redirection. Services accessed included Spotify (audio), YouTube (video), Discord, WhatsApp, and Telegram for chat, VoIP, and file transfer sessions.

I2P (Invisible Internet Project): We installed I2P using Docker, simulating access to hidden services like ramble.i2p and i2pforum.i2p. Behaviors recorded included browsing, email via i2pmail, chatting via i2pchat, video streaming (via invidious front-end), and torrent-based file transfers.

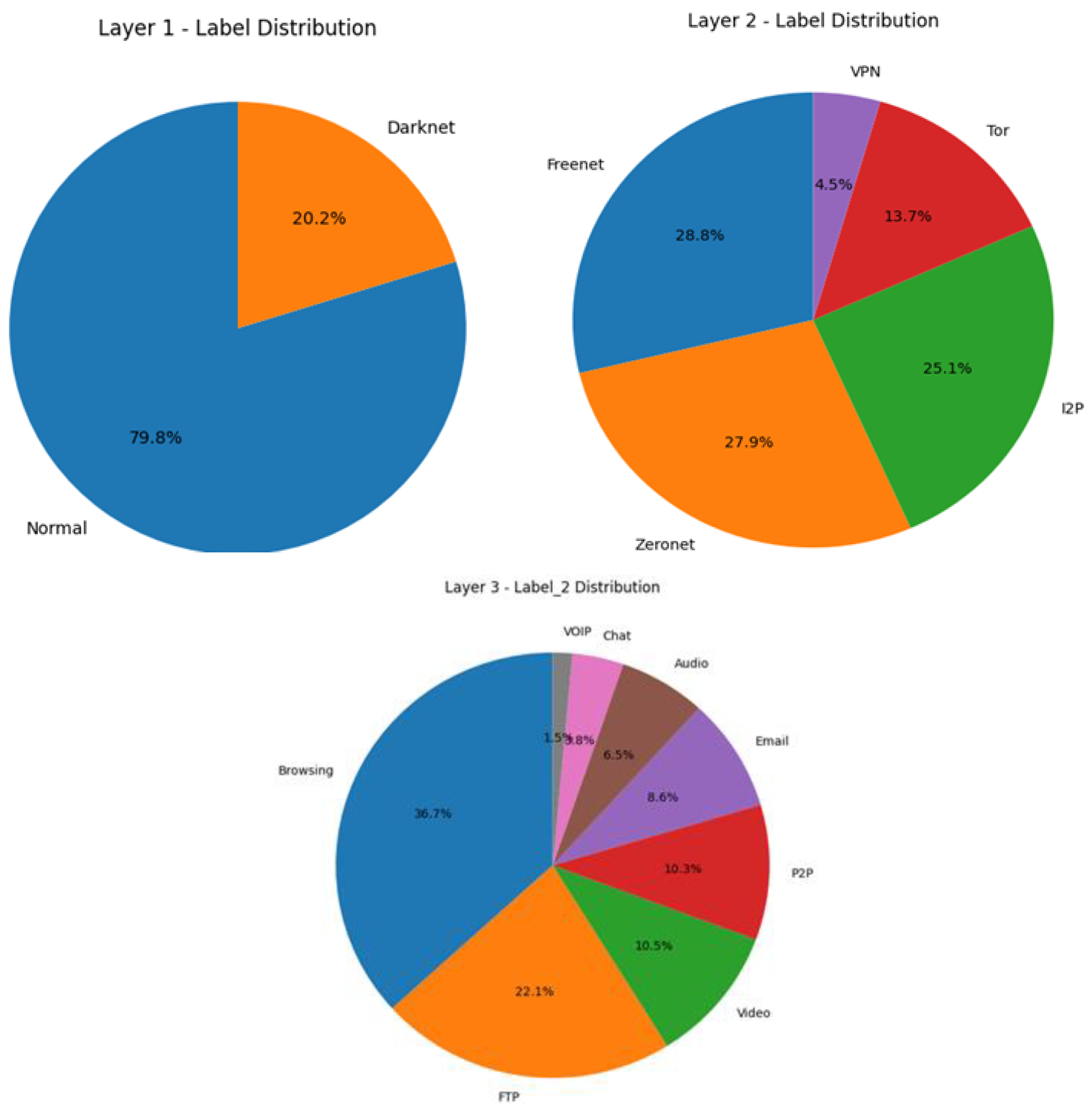

Traffic was generated manually to reflect realistic usage patterns, capturing user-initiated behaviors in various darknet ecosystems. Some automation (e.g., repeated uploads/downloads) was used in the VPN file transfer scenario to ensure sufficient data volume. Approximately

127 MB of traffic was collected, resulting in layer One

~253,000 flows and

~91,000 flows in layer 2 and 3, as shown in

Figure 2, each annotated with

79 distinct features. This setup offers a wide behavioral representation while maintaining a manageable dataset size for experimentation and analysis.

2.2. Dataset Characteristics

Labeling was achieved by manually assigning a behavior class to each traffic capture session, based on the known generation context. For instance, if a capture session involved streaming a video over Tor, it was labeled accordingly. No automated labeling tools were used; the behavior was isolated by setup and traffic timing, ensuring ground-truth integrity. The dataset is organized around behavioral classes rather than protocol or port distinctions. Across the Tor, Freenet, I2P, Zeronet, and VPN environments, we defined and captured traffic for nine behaviors: browsing, Email, chatting, VOIP, file transfer, audio streaming, video streaming, and P2P sharing. Each class has multiple examples derived from different darknet technologies to allow for intra-class variation and robust classifier training. For example, video streaming traffic includes captures from YouTube over Tor, FreeTube on Freenet, and ZeroTube on ZeroNet, each exhibiting underlying traffic signatures.

The dataset is structured in CSV format, with each row representing a single network flow and labeled according to the behavior class. The features include timestamp, flow duration, packet statistics, byte counts, inter-arrival times, and header information. This structure is intended to support tasks such as classifying darknet behaviors, traffic profiling, and anomaly detection in academic and operational cybersecurity research.

2.3. Data Annotation and Labeling

Due to availability issues, we did not cover all nine behaviors in all darknet types in the table. The captured behaviors for each darknet type are shown below in

Table 1.

The following table,

Table 2, shows the label counts of the layer one dataset:

The following table,

Table 3, shows the label counts of the layer two dataset:

The following table,

Table 4, shows the label counts of the layer three dataset:

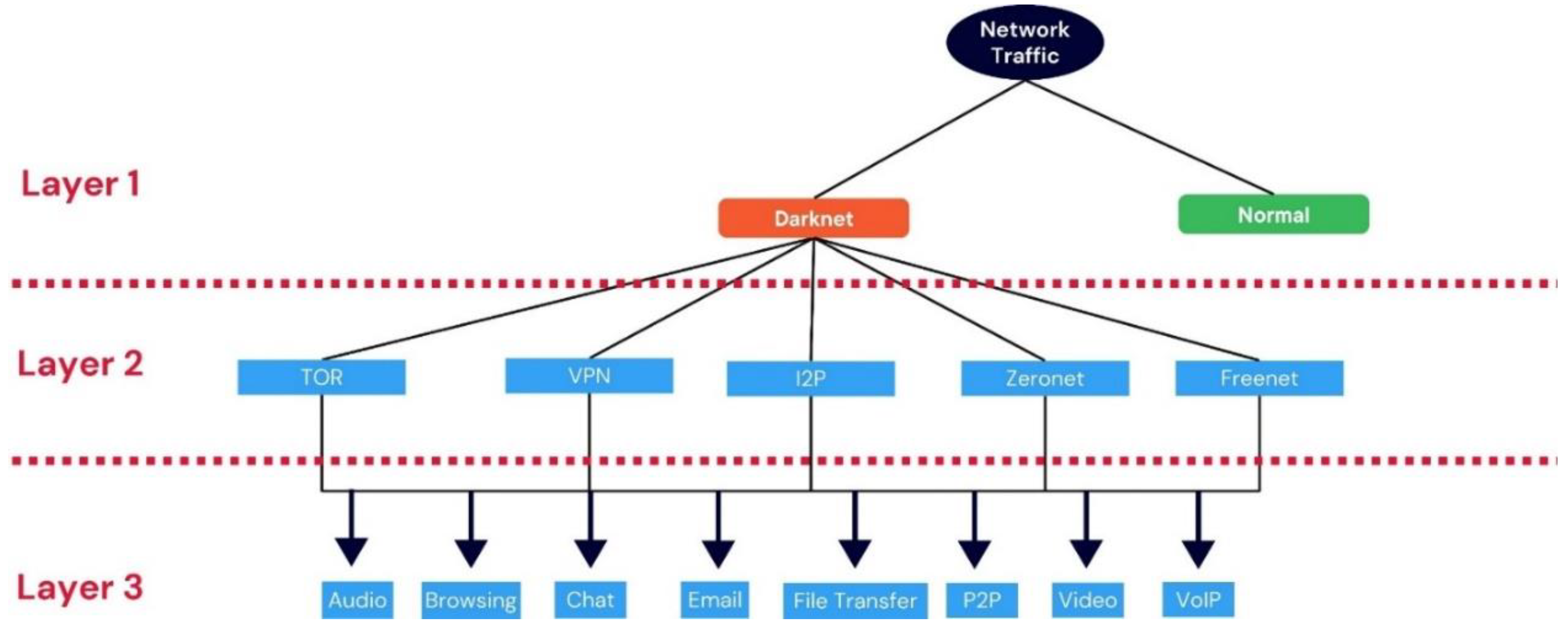

The following pie charts in

Figure 3 Illustrate each label's distribution in the three layers of the captured data.

3. Experimental Setup and Benchmarking

3.1. Data Preprocessing

The preprocessing phase involved several key steps to prepare the dataset from all three layers for machine learning:

Feature Inspection: All dataset features across the three layers were initially examined.

Handling Missing Values: Null values were identified and removed to ensure data completeness.

Removing Duplicates: Duplicate records were checked and addressed.

Zero-Value Features: Features with only zero values were detected and excluded from the dataset.

Filtering Misclassified and Non-Relevant Flows: (a) Traffic involving well-known DNS servers (e.g., Google, Cloudflare) was removed. (b) Communications between private IPs were also excluded.

Eliminating String-Based Features: Features containing non-numeric (string) values unsuitable for machine learning were removed.

Feature Selection via ANOVA: (a) Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was applied to select the most relevant numerical features. (b) Features with a p-value ≤ 0.05 were retained as they showed statistically significant differences between label groups.

3.2. Machine Learning Training

In this section, cleaned and pre-processed data are trained through various machine learning models, including the following:

Gaussian Naive Bayes (GNB) is a type of Naive Bayes method based on continuous attributes and the data features that follow a Gaussian distribution throughout the dataset. This “naive” assumption simplifies calculations and makes the model fast and efficient. Gaussian Naive Bayes is widely used because it performs well even with small datasets and is easy to implement and interpret

Decision Tree Classifier (DT): is a flowchart-like tree structure where an internal node represents a feature (or attribute), the branch represents a decision rule, and each leaf node represents the outcome.

Random Forest (RF) is a method that combines the predictions of multiple decision trees to produce a more accurate and stable result. It can be used for both classification and regression tasks.

The random forest classifier has two main parameters that can be adjusted to maximize prediction accuracy: the number of estimators and the maximum leaf nodes. The following table,

Table 5, represents the best parameters of each layer, which we determined through trial and comparison.

Logistic Regression is a supervised machine learning algorithm used for classification tasks where the goal is to predict the probability that an instance belongs to a given class or not. Logistic regression is a statistical algorithm that analyzes the relationship between two data factors.

XGBoost is a high-performance machine learning algorithm that utilizes gradient boosting and ensemble learning techniques to optimize predictive accuracy and computational speed by efficiently combining multiple decision trees for improved model performance.

Multilayer Perceptron (MLP): is an artificial neural network consisting of multiple layers of interconnected nodes, each performing specific computations to process input data and make predictions.

A Support Vector Machine (SVM) is a supervised machine learning algorithm for classification and regression tasks. It finds the optimal hyperplane (or line in 2D space) that best separates different classes in a dataset, maximizing the margin between them.

Bagging Decision Trees (Bag-DT) is an ensembled modelling technique, used to combine multiple Decision Trees in parallel into memory, to build a stronger model

Ensemble Learning (DT, RF, XGBoost): is a method where we use many small models instead of just one. Each model may not be strong, but when we combine their results, we get a better and more accurate answer. It's like asking a group of people for advice instead of just one person. Each one might be a little wrong, but together, they usually give a better answer

Testing and evaluation. The table summarizes the classification accuracy of various machine learning models across three hierarchical layers.

Decision Tree achieved the highest accuracy in Layer 1 (

99.46%) and Layer 3 (

84.93%), while

XGBoost slightly outperformed others in Layer 2 with

96.21% accuracy. Ensemble methods and Random Forest also demonstrated strong performance, especially in Layers 1 and 2. In contrast, models like

GaussianNB and

Logistic Regression underperformed across all layers, indicating their limited suitability for this task. Overall, tree-based models and ensemble techniques proved to be the most effective for this multi-layer classification problem as provided in

Table 6.

Table 7 Evaluates the computational efficiency of each model across the three classification layers. We measured the Training time in seconds. Simpler models like

Decision Tree and

SVM (with MinMax Scaler) demonstrated the lowest time complexity, completing execution in under 0.1 seconds across all layers.

GaussianNB also maintained low execution times, though slightly higher in Layer 3 due to increased complexity. In contrast, ensemble methods such as

Bagging-DT and

Ensemble (XGBoost, DT, RF) required significantly more processing time, particularly in Layers 1 and 3, highlighting the trade-off between accuracy and computational cost. For instance, Bagging-DT took over 9 seconds in Layer 1.

MLP and

Random Forests offered a balanced performance in terms of time and accuracy, maintaining moderate training times below 1 second for most layers. This comparison helps choose models based on accuracy and resource efficiency, which are crucial in real-time or resource-constrained environments. The following tables,

Table 8,

Table 9 and

Table 10, show the summary of the study, including the accuracy performance of various machine learning models across three classification layers and their corresponding training time (in seconds), highlighting the trade-offs between predictive performance and computational efficiency. Based on the results, the Decision Tree model was selected as the final choice due to its consistently high accuracy across all layers and low computational cost.

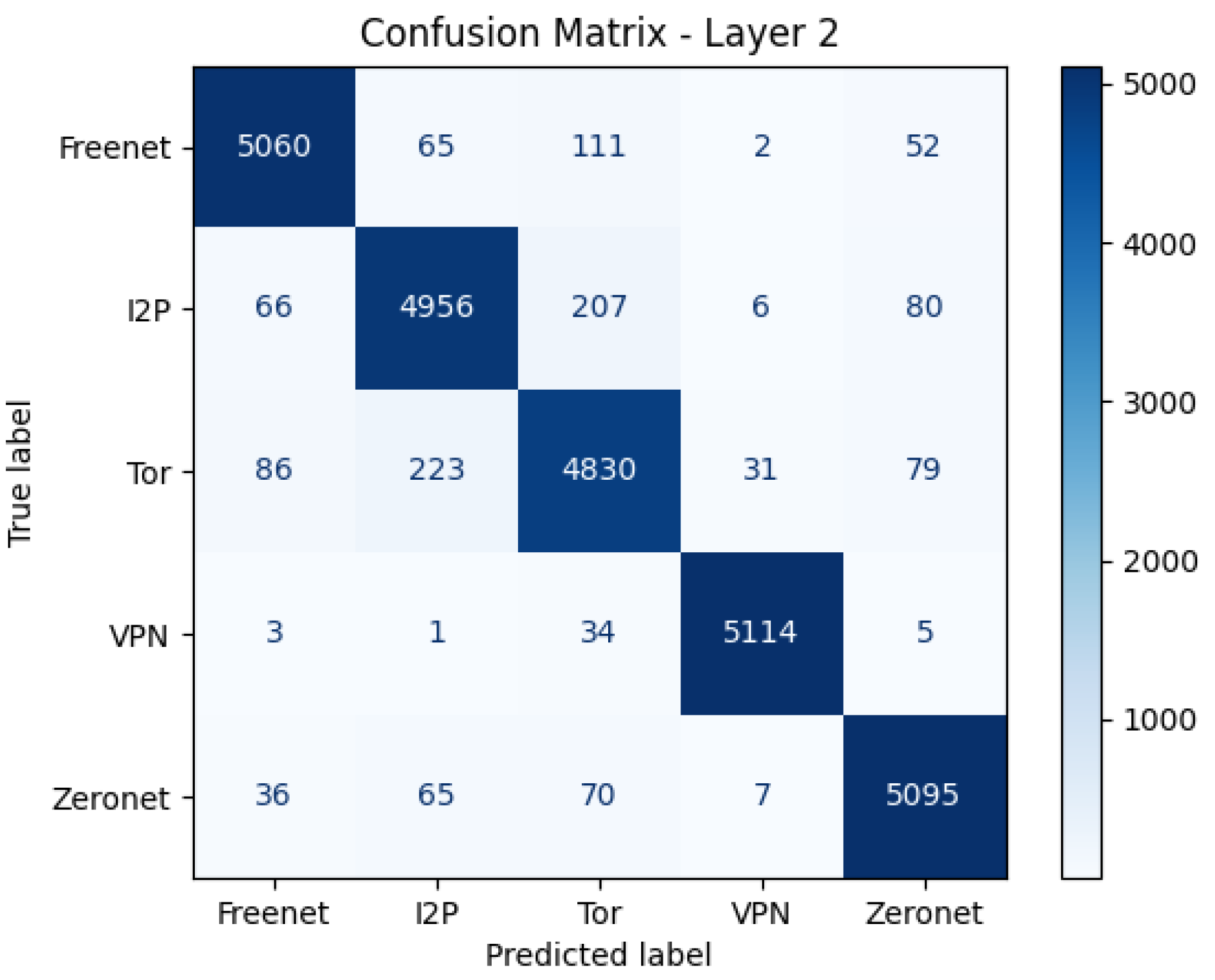

After we conducted this comprehensive evaluation of various supervised learning algorithms, we assessed each model based on standard metrics such as accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and performance, and the Decision Trees consistently demonstrated inferior results. Consequently, we selected the Decision Tree algorithm as the best algorithm. More details about the results of the Decision Trees algorithm are provided below. The following

Figure 4 shows the Confusion Matrix for Layer 2 (Darknet Protocol Classification)

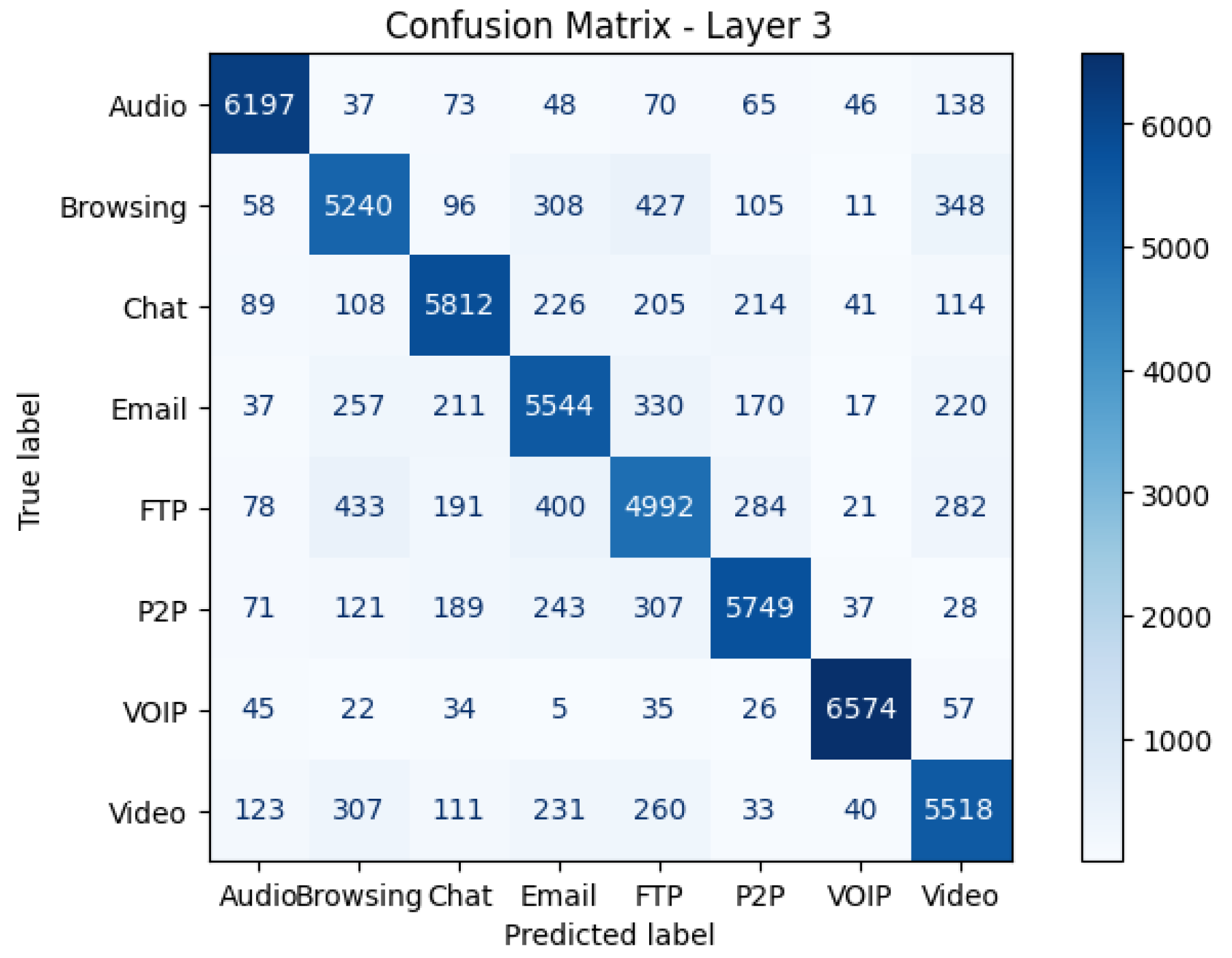

The following

Figure 5 shows the Confusion Matrix for Layer 3 (Darknet Behavior Classification)

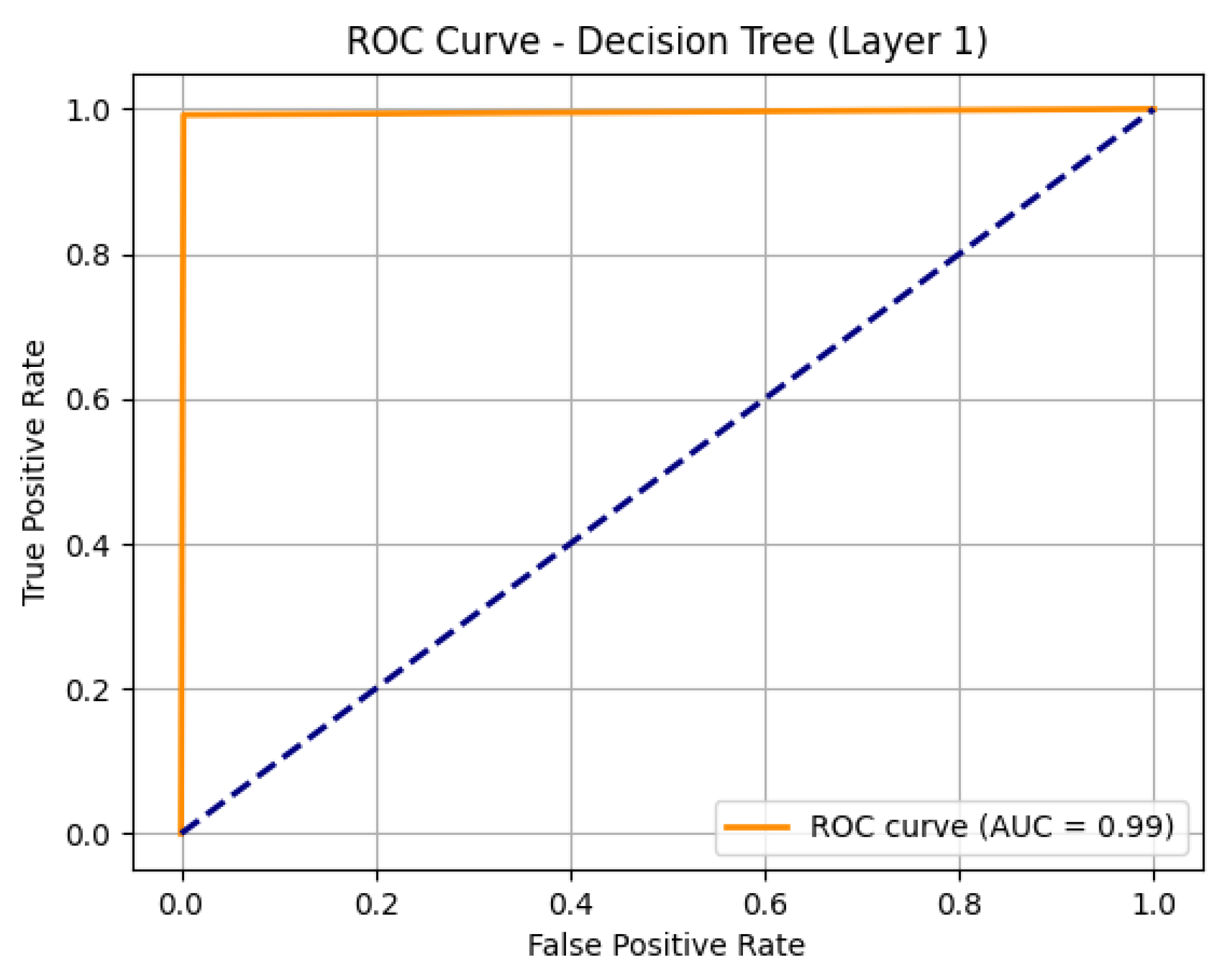

The following

Figure 6 shows the ROC Curve for Layer 1 (Normal vs Darknet)

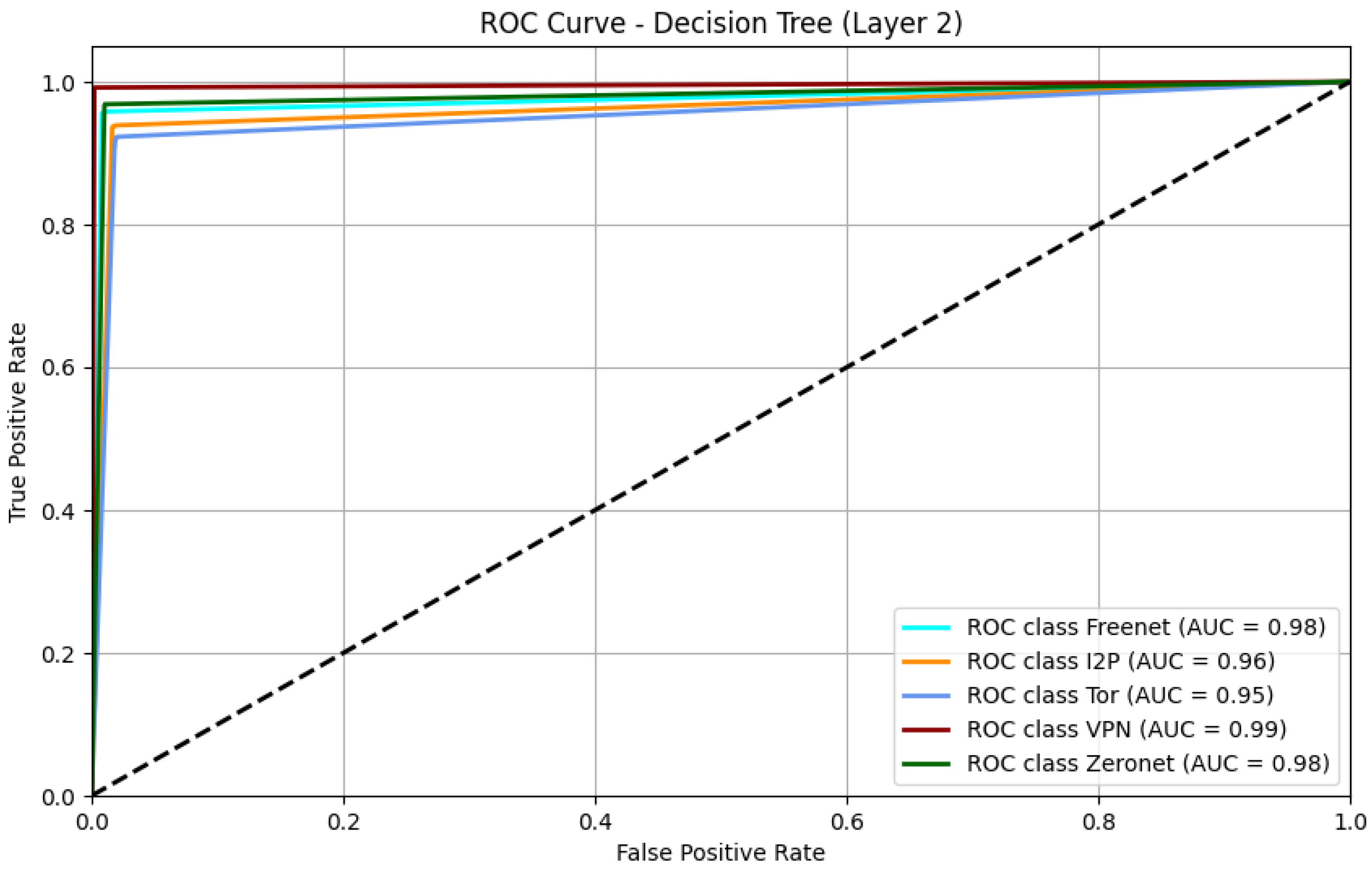

The following

Figure 7 shows the ROC Curve for Layer 2 (Darknet Protocol Classification)

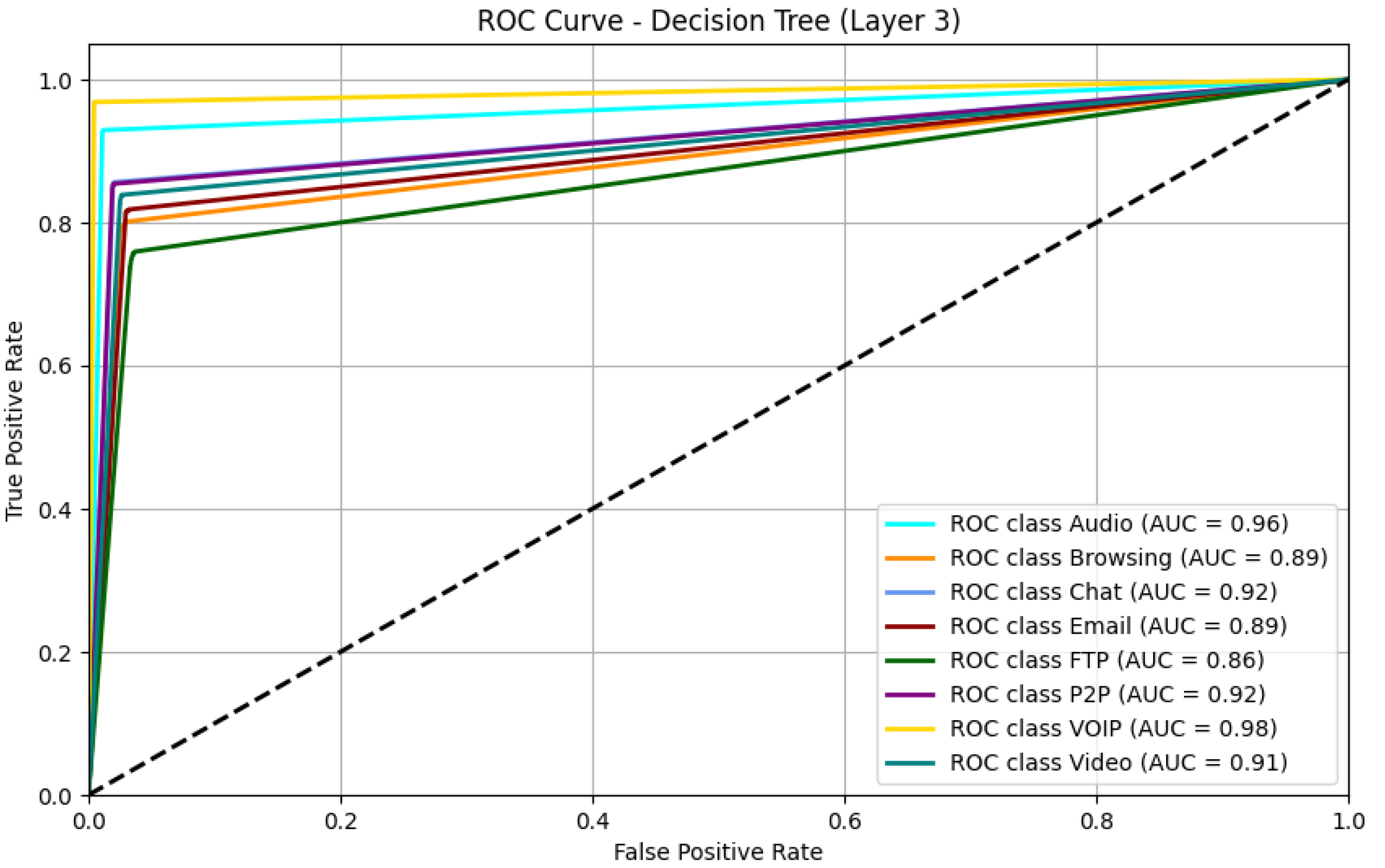

The following

Figure 8 shows the ROC Curve for Layer 3 (Darknet Behavior Classification)

4. Potential Applications

The SafeSurf Darknet 2025 dataset presents numerous opportunities for researchers and cybersecurity practitioners by providing rich, labeled traffic data across multiple darknet technologies and behavioral categories. Its detailed structure and behavior-focused labeling make it suitable for real-world and academic applications.

4.1. Intrusion Detection and Anomaly Detection

One of the primary applications of this dataset is the development and evaluation of Intrusion Detection Systems (IDS) and Anomaly Detection models. Due to its encrypted and obfuscated nature, traditional IDS solutions often struggle to detect or correctly interpret darknet traffic. By offering labeled samples of diverse darknet behaviors such as P2P sharing, encrypted chat, and decentralized video streaming, the dataset allows training models to detect anomalous patterns within network traffic, even when payload data is inaccessible.

4.2. Cyber Threat Intelligence

The dataset supports extracting behavioral signatures associated with various darknet technologies, enabling improved threat profiling and network intelligence. For example, by analyzing flow-level characteristics of Freenet or I2P traffic, analysts can better understand how these protocols operate in the wild. This aids in constructing threat indicators for Security Operations Centers (SOCs), law enforcement investigations, and national cybersecurity agencies aiming to identify or disrupt illicit darknet activities.

4.3. Behavioral Traffic Classification

Unlike many existing datasets that only distinguish between benign and malicious traffic, SafeSurf Darknet 2025 supports multi-class behavioral classification. Machine learning models can be trained to detect darknet traffic and classify the specific type of activity (e.g., video streaming vs. file transfer). This capability is crucial for building context-aware security systems that adapt responses based on the detected activity rather than relying solely on binary decisions.

4.4. Network Traffic Analysis Research

The dataset is also well-suited for academic research in network traffic analysis, particularly studies focusing on encrypted traffic, flow-based feature engineering, and darknet protocol identification. With a diverse mix of traffic types across Tor, Freenet, ZeroNet, I2P, and VPN environments, researchers can experiment with various analytical techniques, from feature selection to time-series modeling.

4.5. Curriculum and Educational Use

Finally, the dataset can be a practical resource for educational purposes in cybersecurity and data science courses. It provides students with hands-on experience in preprocessing, exploratory data analysis, and machine learning on real-world darknet traffic, preparing them for cyber defense and intelligence careers.

5. Ethical Considerations and Limitations

Ethical concerns related to darknet data collection.

Steps taken to ensure privacy and compliance with regulations.

Limitations of the dataset (e.g., biases, data representativeness).

5.1. Ethical Considerations

Creating and analyzing darknet traffic datasets involves unique ethical challenges due to the nature of the data and its potential associations with privacy-sensitive or illicit content. In the SafeSurf Darknet 2025 dataset, we took deliberate steps to ensure the ethical integrity of our data collection and handling procedures.

First, no engagement with illegal darknet services or marketplaces occurred during the data collection. All behaviors were simulated using publicly accessible darknet tools and services that support anonymity but are not inherently illegal, such as Tor, I2P, Freenet, and ZeroNet. The browsing and communication patterns captured were confined to generic activities (e.g., accessing blogs, downloading sample files, sending test messages), avoiding exposure to illicit content.

Second, no real personal data was included in the dataset. All traffic was generated in a controlled and consented environment using test accounts and machines. Any potentially sensitive identifiers (e.g., IP addresses, usernames) were anonymized or sanitized where applicable to preserve privacy.

Third, the dataset aligns with ethical guidelines for cybersecurity research and complies with local data protection standards. The traffic does not contain payload data; only flow-level metadata and statistical features were retained to reduce any risk of content-level privacy violations.

The dataset is intended strictly for research and educational purposes, and users are expected to comply with institutional review board (IRB) policies or national regulations applicable in their jurisdictions.

5.2. Limitations

While the SafeSurf Darknet 2025 dataset introduces several improvements over existing datasets, certain limitations must be acknowledged to contextualize its appropriate use and interpretation.

Synthetic Environment Bias: The traffic was generated through real applications and intentional behaviors but was still conducted in a controlled and partially simulated environment. This may not fully reflect the complexity, noise, or unpredictability of actual darknet communications in the wild, potentially affecting the robustness of models trained exclusively on this dataset.

Representativeness and Overfitting Risk: The dataset, while diverse, may not capture the full spectrum of darknet traffic variations due to differences in user behavior, time, geography, and network conditions. As a result, machine learning models trained on this dataset may risk overfitting to its specific traffic patterns, particularly when applied to unseen or real-world environments. Researchers are encouraged to use this dataset alongside other sources or perform cross-dataset validation when possible.

Incomplete Behavioral Coverage: In some darknet technologies, we could not simulate or access certain behaviors, especially those in deeper functional layers (e.g., decentralized email, P2P file sharing, or video streaming in inactive or partially deprecated networks). This was due to service unavailability, inactive peer networks, or technical restrictions in protocols like Freenet and I2P during the data collection.

Protocol and Platform Scope: The dataset includes a targeted set of darknet platforms (Tor, Freenet, ZeroNet, I2P, VPN), but omits other technologies such as GNUnet, LokiNet, or RetroShare. This may limit its comprehensiveness in representing the entire darknet ecosystem.

Temporal Constraints: All traffic was collected over a specific period, which may exclude evolving usage patterns or emerging darknet platforms. Periodic updates would be needed to maintain relevance and adaptability to current threats.

Encrypted Traffic Complexity: As with many flow-based datasets, payload content is unavailable. While this enhances privacy and ethics compliance, it also restricts the depth of semantic analysis possible in applications like content-based filtering or deep behavioral profiling.

Despite these limitations, the dataset remains a valuable and much-needed resource for advancing darknet detection, classification, and threat intelligence research. Future iterations aim to address these gaps through broader behavioral coverage, longer data collection windows, and integration with additional darknet technologies.

6. Conclusions and Future Work

This paper introduced the SafeSurf Darknet 2025 dataset — a novel and behavior-focused darknet traffic analysis and classification resource. Unlike many datasets primarily focusing on binary detection tasks, our dataset is structured around various behavioral classes across multiple darknet technologies, including Tor, I2P, Freenet, ZeroNet, and VPN. Traffic was captured in realistic environments using physical and virtual machines, and labeling was performed based on direct observation and controlled behavior invocation, ensuring strong ground-truth accuracy.

The dataset offers a rich foundation for various applications, such as anomaly detection, traffic classification, and cyber threat intelligence. Its structured format and feature-rich design support traditional analysis and modern machine learning research. It is also intended for public release, making it a valuable resource for academic and professional cybersecurity communities.

Looking ahead, several directions can be pursued to enhance the scope and utility of the dataset:

Expansion of Behavioral Coverage: Additional behaviors that could not be captured due to technical or network limitations—such as decentralized email or video streaming on inactive darknet services—can be included in future iterations.

Inclusion of More Protocols: Future versions may incorporate other darknet technologies such as GNUnet, LokiNet, or Retroshare to broaden the representational coverage of darknet traffic.

Long-Term Data Collection: Extending the capture period will enable the observation of temporal changes in darknet traffic, allowing for the study of long-term trends and protocol evolution.

Machine Learning Benchmarking: While initial tests showed promising results, future work may include formal benchmarking of classification models across multiple behaviors, feature sets, and darknet technologies. This could also include comparisons with other datasets to evaluate generalization.

Cross-Dataset Validation: To reduce overfitting risks and improve robustness, future studies may combine this dataset with others in joint evaluations.

Payload-Inclusive Variant(If ethically and legally viable) Consider a secure variant with limited payload samples for advanced analysis or encrypted traffic modeling.

Public Release and Community Support: We aim to release the dataset with full documentation, usage guidelines, and version control to encourage reproducibility, community feedback, and collaborative improvements.

In summary, the SafeSurf Darknet 2025 dataset addresses key limitations in existing darknet traffic datasets and sets the stage for more nuanced and effective research in cybersecurity. Future developments will continue to refine its accuracy, scope, and relevance in detecting and understanding darknet activities.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset generated in this research is published by Mendeley Data/Elsevier, a public repository, and can be accessed through:

Dataset Link:

https://data.mendeley.com/drafts/kcrnj6z4rm.

Dataset DOI: 10.17632/kcrnj6z4rm.2.

References

- Al-Fayoumi, M.; Elayyan, A.; Odeh, A.; Al-Haija, Q.A. Tor network traffic classification using machine learning based on time-related feature. 6th Smart Cities Symposium (SCS 2022), Hybrid Conference, Bahrain, 2022, pp. 92-97. [CrossRef]

- Al-Haija, A.; Krichen, Q.; Elhaija, A.W. Machine-Learning-Based Darknet Traffic Detection System for IoT Applications. Electronics 2022, 11, 556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Zou, F.; Li, L.; Yi, P. Traffic Classification of User Behaviors in Tor, I2P, ZeroNet, Freenet. 2020 IEEE 19th International Conference on Trust, Security and Privacy in Computing and Communications (TrustCom), Guangzhou, China, 2020, pp. 418-424. [CrossRef]

- Alimoradi, M.; Zabihimayvan, M.; Daliri, A.; Sledzik, R.; Sadeghi, R. Deep Neural Classification of Darknet. Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence and Applications, Volume 356: Artificial Intelligence Research and Development.

- Rawashdeh, M.; Al-Haija, Q.A.; Qasaimeh, M. Analysis of TOR Artifacts and Traffic in Windows 11: A Virtual Lab Approach and Dataset Creation," 2023 14th International Conference on Information and Communication Systems (ICICS), Irbid, Jordan, 2023, pp. 1-6. [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; He, Y. I2P Anonymous Traffic Detection and Identification. 2019 5th International Conference on Advanced Computing & Communication Systems (ICACCS), Coimbatore, India, 2019, pp. 157-162. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Gao, Y.; Shi, J.; Wang, X.; Zhao, C.; Yin, Z. 2020. Look deep into the new deep network: A measurement study on the ZeroNet. In Computational Science–ICCS 2020: 20th International Conference, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, June 3–5, 2020, Proceedings, Part I 20 (pp. 595-608). Springer International Publishing.

- Al-Haija, Q.A.; Ibrahim, R. Introduction to Dark Web. in Perspectives on Ethical Hacking and Penetration Testing, IGI Global, 2023, p. 445.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).