Submitted:

22 July 2025

Posted:

23 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

3. Case Studies

3.1. Pilot Site Selection

3.2. The Algarve Pilot Site

- ▪

- In-situ ship transects: A set of irregularly spaced SST measurements collected along a research vessel’s transect in the study area (shipborne survey). These moving platform measurements sample a continuous path but leave large portions of the domain unobserved.

- ▪

- Fixed buoy station: SST time series measurements from the permanent oceanographic buoy near Faro (approximately 36°54′ N, 7°54′ W). On the target date, this buoy provided a high accuracy point SST reading, anchoring the dataset at a fixed coastal location.

- ▪

- Satellite reanalysis product: Gridded SST from the ODYSSEA reanalysis system, which blends multi sensor satellite data at about 0.10° resolution. Over the ~30km extent, this corresponds to a coarse grid spacing of roughly 10km, yielding only a few grid points covering the region.

3.3. The La Spezia Pilot Site

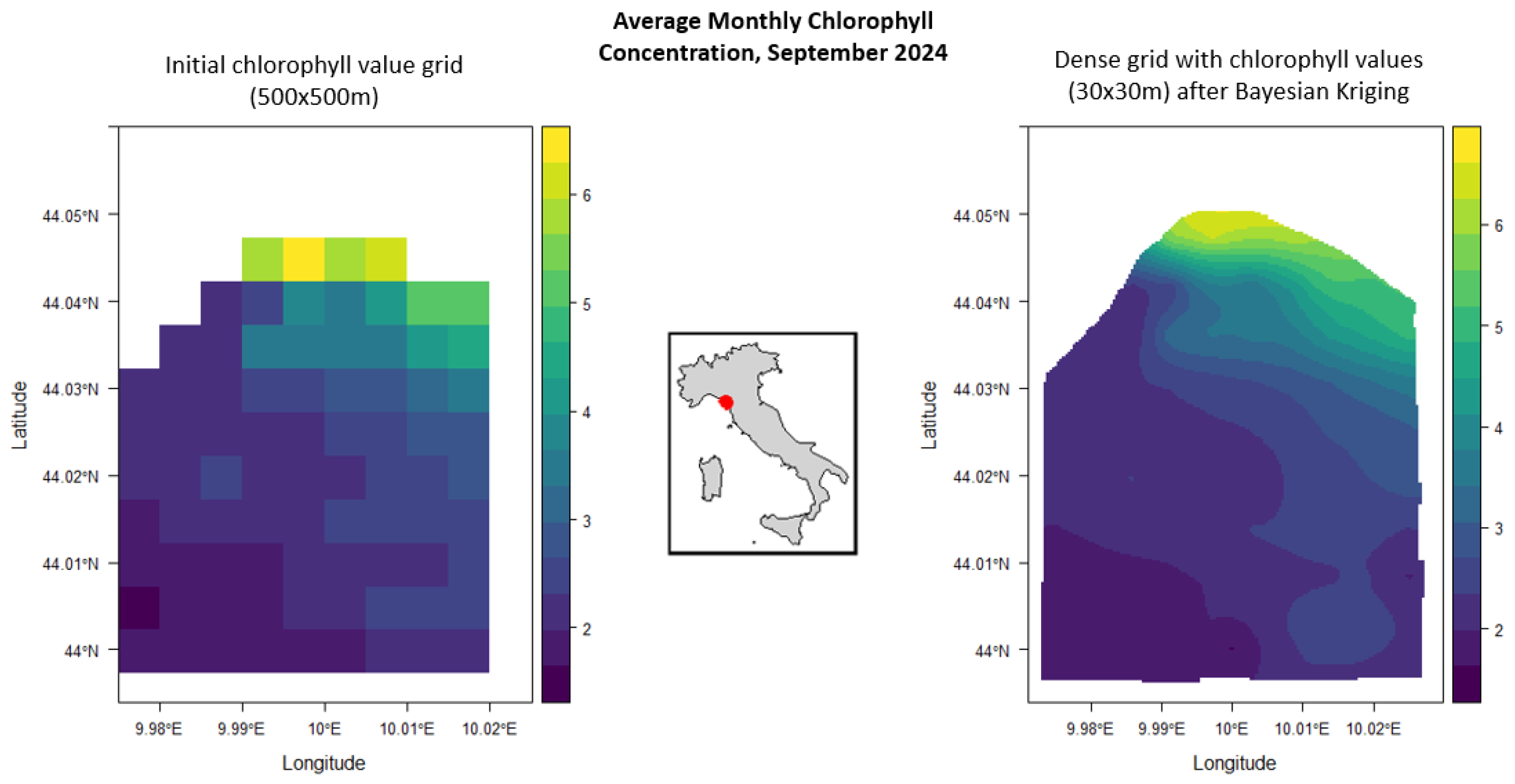

3.4. Densification Grid

4. Model Specification and Implementation

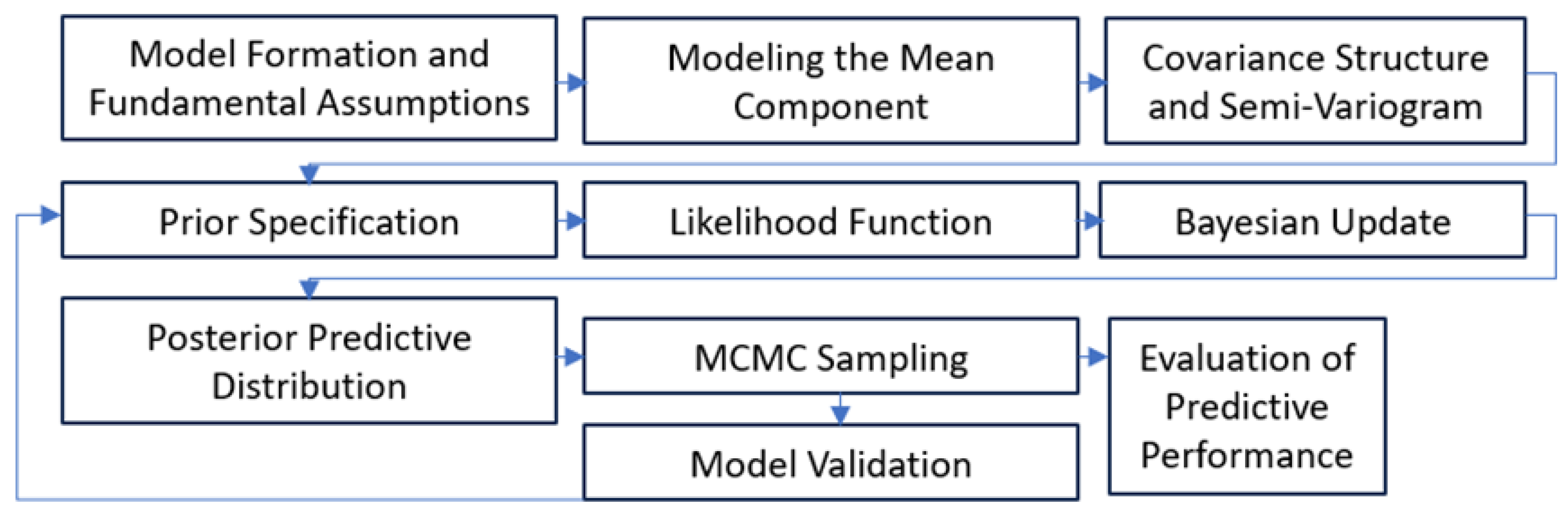

4.1. Bayesian Kriging Formulation

- ▪

- Model Formation and Fundamental Assumptions: The response variable is treated as a realization of a Gaussian random field defined on geographic space. Stationarity of the increments and second order moments is assumed so that spatial dependence can be characterised solely through the semivariogram function.

- ▪

- Modeling the Mean Component: Large scale trends are represented by a deterministic mean μ(s), typically specified as an intercept only term or a linear combination of geographic covariates. Removing this trend isolates the small scale, spatially correlated residuals that kriging is designed to model.

- ▪

- Covariance Structure and Semivariogram: Spatial autocorrelation is introduced through the Matern covariance function, parameterised by partial sill, range and nugget. The empirical semivariogram provides the initial diagnostic for selecting the functional form and for setting hyperparameters.

- ▪

- Prior Specification: Weakly to non informative priors are assigned to the variogram parameters (e.g. suitable inverse gamma for variances, uniform or log normal for the range) and to the regression coefficients. Knowledge such as expected correlation lengths or measurement error magnitude, is encoded at this stage.

- ▪

- Likelihood Function: Given the assumed Gaussian process, the joint likelihood of the observations is multivariate normal with mean μ(s) and covariance Σ(θ). This term links the data to the unknown parameter vector θ = {σ², τ², ϕ}.

- ▪

- Bayesian Update: Bayes’ rule combines the likelihood with the priors to obtain the posterior distribution p(θ | Z). This update formally propagates both sampling noise and prior uncertainty into all subsequent predictions.

- ▪

- Posterior Predictive Distribution: For any unsampled location s₀, the predictive distribution p(Z(s₀) | Z) is obtained by integrating the kriging conditional mean and variance over the posterior of θ. The result is a full probabilistic surface rather than a single point estimate.

- ▪

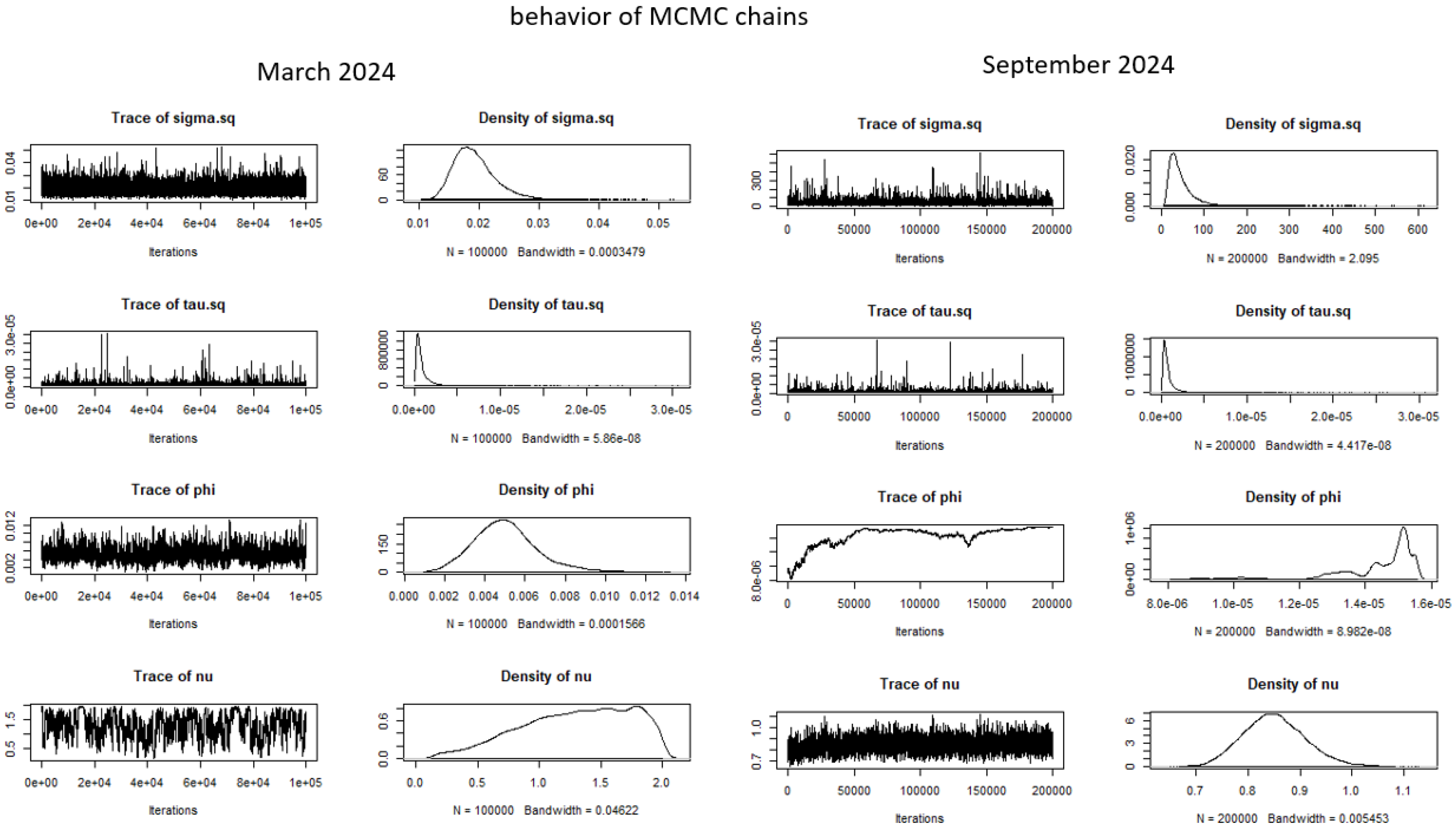

- MCMC Sampling: Because the posterior is analytically intractable, MCMC (Gibbs/Metropolis Hastings algorithm) is used to draw a representative ensemble of θ values. Convergence diagnostics (trace plots, Geweke z-scores, acceptance rates) ensure adequate exploration of the space parameter.

- ▪

- Evaluation of Predictive Performance: Posterior draws are summarised to compute point predictions, 95% credible intervals and uncertainty maps. Accuracy is quantified with cross validation metrics RMSE, MAE, R², while coverage tests verify that the empirical proportion of observations falling inside the credible bands matches the nominal level.

- ▪

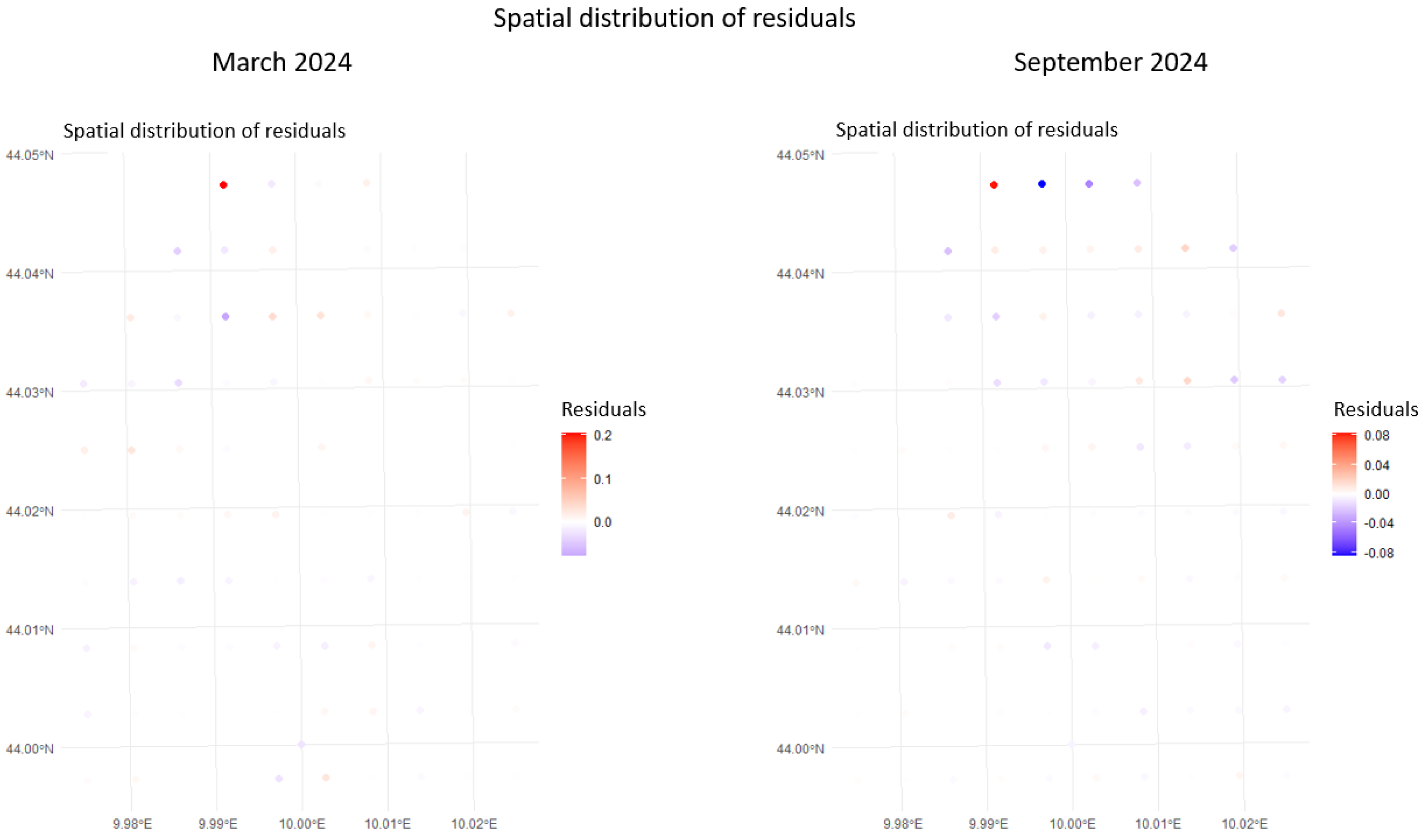

- Model Validation: Residual analyses assess whether assumptions are met and whether additional covariates or alternative priors are required. Validated models are then carried forward to generate the final, high resolution densified grids.

4.2. MCMC Configuration

4.3. Computational Setup

5. Results and Evaluation

- ▪

- Acceptance rates: ~0.35 for key parameters indicating efficient proposal acceptance.

- ▪

- Convergence tests: Gelman - Rubin potential scale reduction factors were ≈1.00 for all monitored parameters and Geweke’s z-scores (two sided test) were not significant (p > 0.05), indicating no evidence of non convergence.

- ▪

- Trace plots: Representative chains stabilized relatively quickly after burn-in with no apparent trends. The multiple experiments (poilot runs) we did showed that quick convergence depends directly on the size of the study area.

- ▪

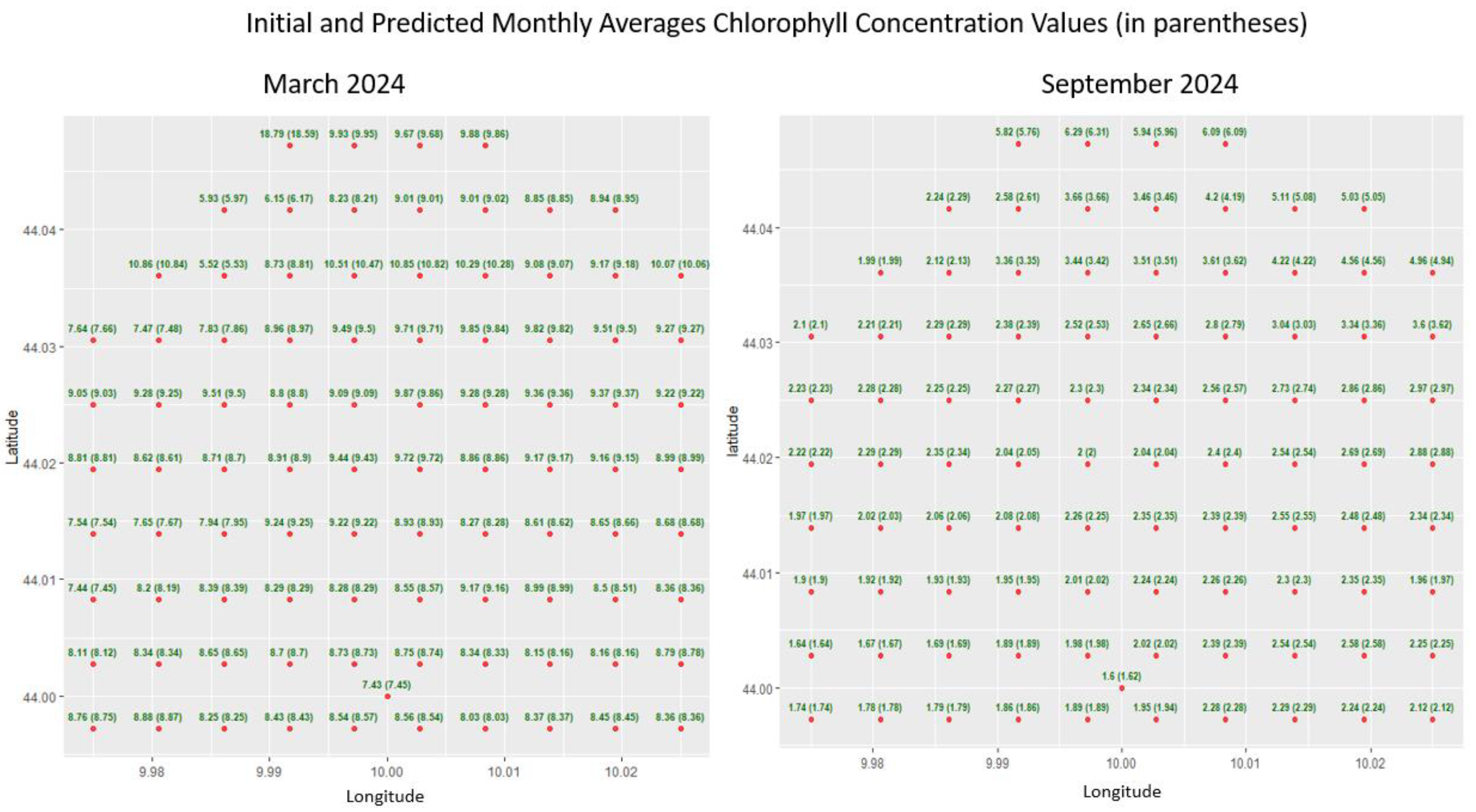

- Cross validation performance assessment using RMSE, MAE and R² metrics.

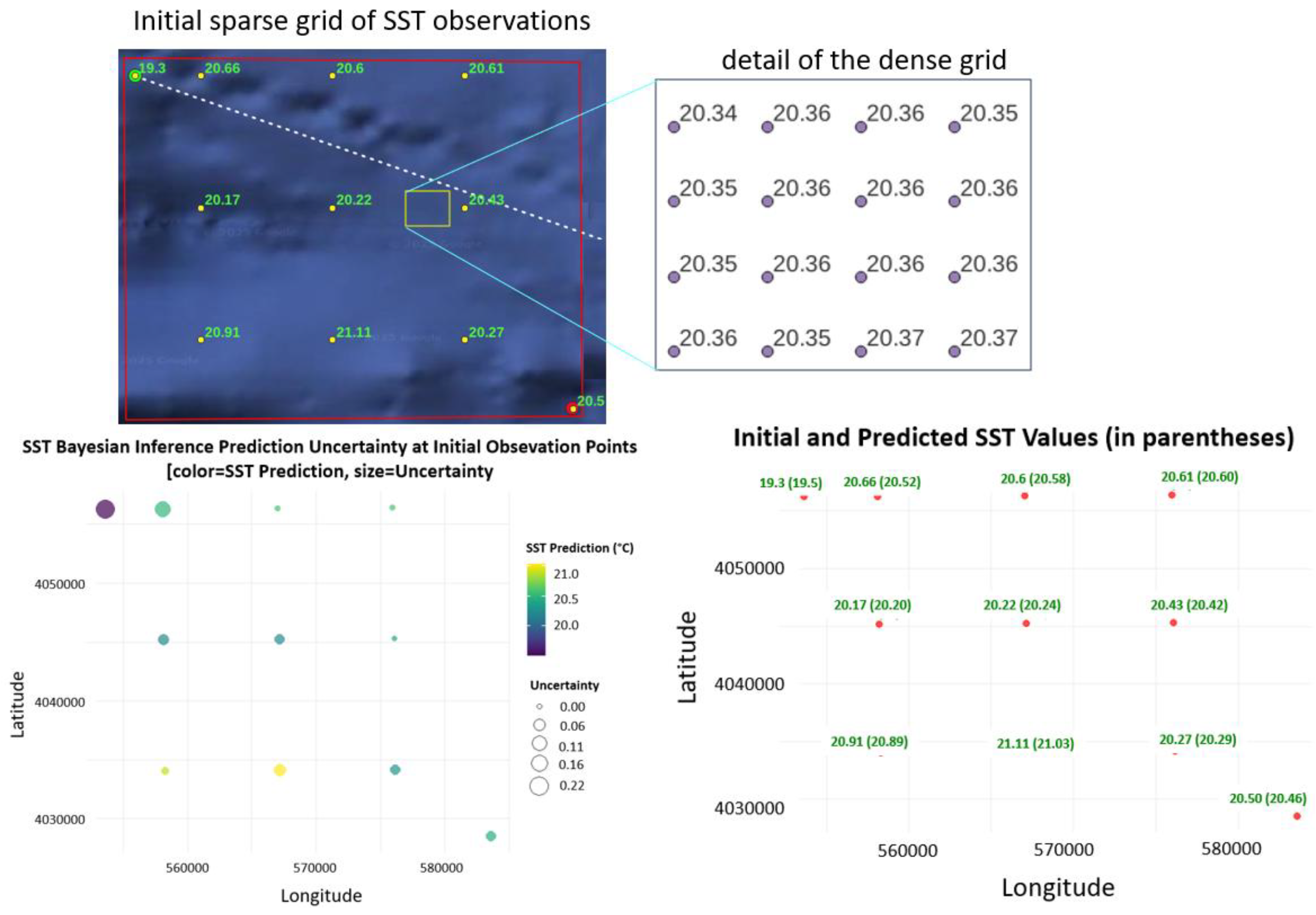

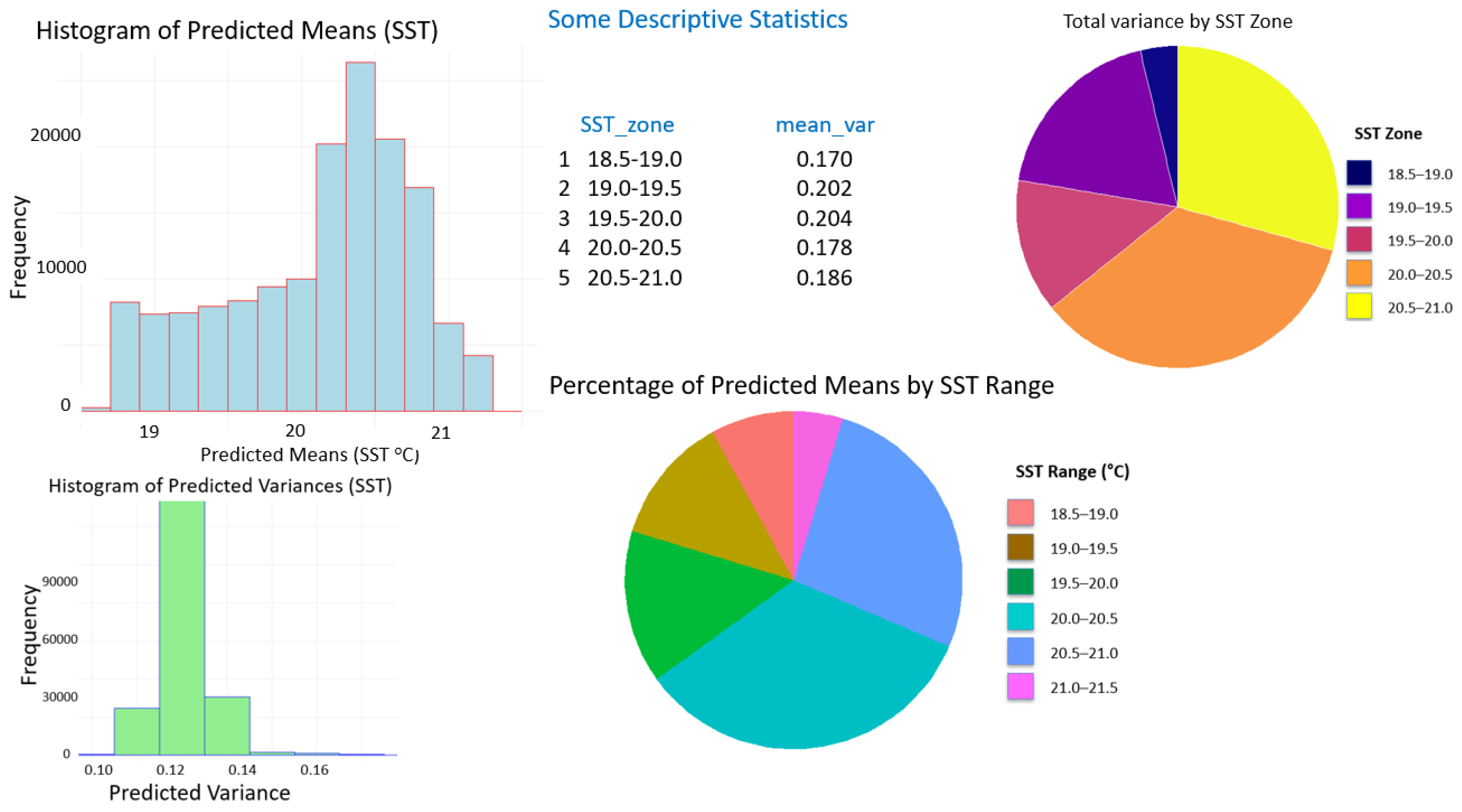

5.1. Algarve, SST Densification

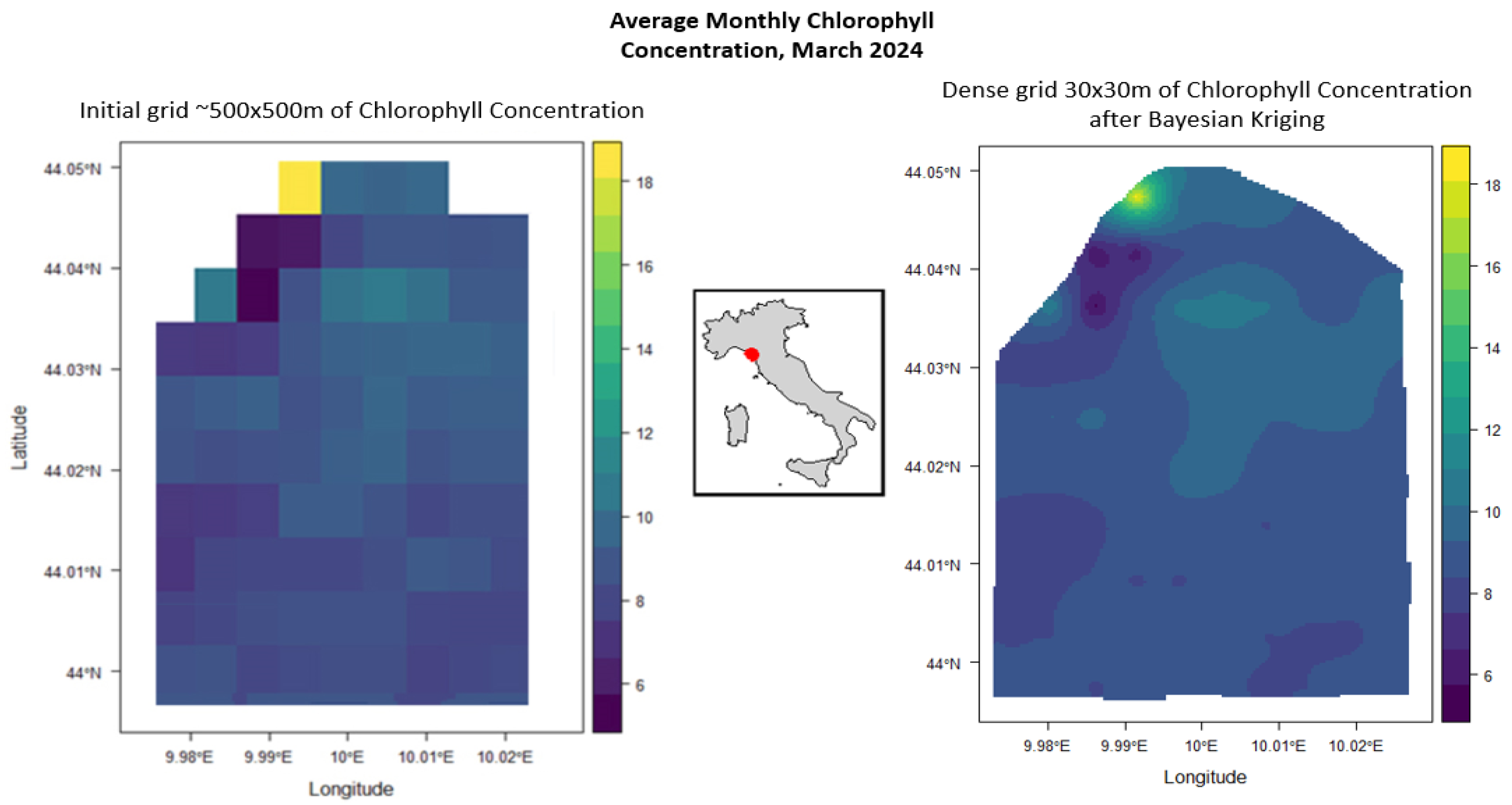

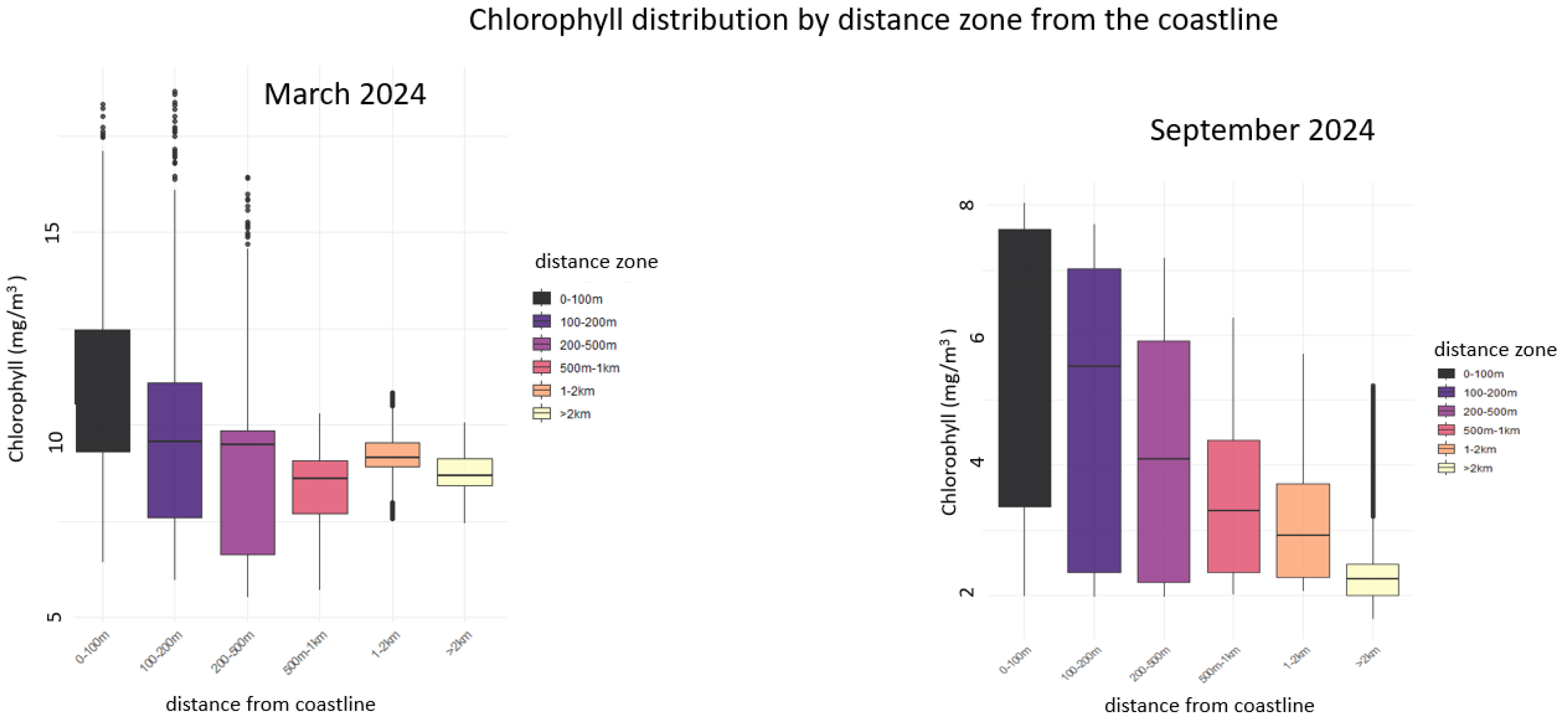

5.2. La Spezia (Italy), Chlorophyll Densification

6. Discussion - Conclusions

6.1. Comparative Performance in Algarve vs. La Spezia

6.2. Implications for Hypotheses and Broader Context

6.3. Influence of Prior Specification on Densification Quality

6.4. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SST | Sea Surface Temperature |

| EBK | Empirical Bayesian Kriging |

| MCMC | Markov Chain Monte Carlo |

| RMSE | Root Mean Square Error |

| MAE | Mean Absolute Error |

| R² | Coefficient of Determination |

| LOOCV | Leave One Out Cross Validation |

| UTM | Universal Transverse Mercator (projection) |

| IG | Inverse Gamma (distribution) |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

References

- Wang, R.; Pan, D.; Guo, X.; Sun, K.; Clarisse, L.; Van Damme, M.; Coheur, P.-F.; Clerbaux, C.; Puchalski, M.; Zondlo, M.A. Bridging the spatial gaps of the Ammonia Monitoring Network using satellite ammonia measurements. Atmospheric Meas. Tech. 2023, 23, 13217–13234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, Y.; Duan, M.; Cui, X.; Zhao, Q.; Tian, S.; Lin, Y.; Wang, W. Advancing application of satellite remote sensing technologies for linking atmospheric and built environment to health. Front. Public Heal. 2023, 11, 1270033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Li, X.; Yang, R.; Liu, Q.; Zhao, L.; Dou, B. An Extended Kriging Method to Interpolate Near-Surface Soil Moisture Data Measured by Wireless Sensor Networks. Sensors 2017, 17, 1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Heap, A.D. A review of comparative studies of spatial interpolation methods in environmental sciences: Performance and impact factors. Ecol. Informatics 2011, 6, 228–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, N.D.; Zidek, J.V. Interpolation with uncertain spatial covariances: A Bayesian alternative to Kriging. J. Multivar. Anal. 1992, 43, 351–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omre, H. Bayesian kriging?Merging observations and qualified guesses in kriging. J. Int. Assoc. Math. Geol. 1987, 19, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handcock, M.S.; Stein, M.L. A Bayesian Analysis of Kriging. Technometrics 1993, 35, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krivoruchko, K.; Gribov, A. Evaluation of empirical Bayesian kriging. Spat. Stat. 2019, 32, 100368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veronesi, F.; Schillaci, C. Comparison between geostatistical and machine learning models as predictors of topsoil organic carbon with a focus on local uncertainty estimation. Ecol. Indic. 2019, 101, 1032–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, U.; Gautam, S.; Riley, W.J.; Hoffman, F.M. Ensemble Machine Learning Approach Improves Predicted Spatial Variation of Surface Soil Organic Carbon Stocks in Data-Limited Northern Circumpolar Region. Front. Big Data 2020, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, T.; Li, X.; Zhang, L.; Du, J.; Wang, Z. ; A Bayesian Approach to Estimate the Spatial Distribution of Seawater Temperature Using Remote Sensing Data. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaresefat, M.; Derakhshani, R.; Griffioen, J. Empirical Bayesian Kriging, a Robust Method for Spatial Data Interpolation of a Large Groundwater Quality Dataset from the Western Netherlands. Water 2024, 16, 2581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takoutsing, B.; Heuvelink G., B.M. Comparing the prediction performance, uncertainty quantification and extrapolation potential of regression kriging and random forest while accounting for soil measurement errors. Geoderma 2022, 428, 116192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bykov, K.; Höhne, M.-C.; Creosteanu, A.; Müller K., R.; Klauschen, F.; Nakajima, S.; Kloft, M. ; Explaining Bayesian Neural Networks; arXiv:2108. 1 0346. [CrossRef]

- Vicedo-Cabrera, A.M.; Biggeri, A.; Grisotto, L.; Barbone, F.; Catelan, D. A Bayesian kriging model for estimating residential exposure to air pollution of children living in a high-risk area in Italy. Geospat. Heal. 2013, 8, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lompar, M.; Lalić, B.; Dekić, L.; Petrić, M. Filling Gaps in Hourly Air Temperature Data Using Debiased ERA5 Data. Atmosphere 2019, 10, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senanayake, I.P.; Arachchilage, K.R.L.P.; Yeo, I.-Y.; Khaki, M.; Han, S.-C.; Dahlhaus, P.G. Spatial Downscaling of Satellite-Based Soil Moisture Products Using Machine Learning Techniques: A Review. Remote. Sens. 2024, 16, 2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoff, R. M.; Christopher, S. A. Remote sensing of particulate pollution from space: have we reached the promised land? Journal of the Air & Waste Management Association 2009, 59, 645–675. [Google Scholar]

- Agyeman, P.C.; Kebonye, N.M.; John, K.; Borůvka, L.; Vašát, R.; Fajemisim, O. Prediction of nickel concentration in peri-urban and urban soils using hybridized empirical bayesian kriging and support vector machine regression. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaddick, G.; Thomas, M.L.; Amini, H.; Broday, D.M.; Cohen, A.; Frostad, J.; Green, A.; Gumy, S.; Liu, Y.; Martin, R.V.; et al. Data Integration for the Assessment of Population Exposure to Ambient Air Pollution for Global Burden of Disease Assessment. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 9069–9078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stein, M.L. Interpolation of Spatial Data: Some Theory for Kriging; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1999; 87, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, C.E.; Williams, C.K.I. Gaussian Processes for Machine Learning; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2006; pp. 84–89. ISBN 978-0-262-18253-9. [Google Scholar]

- Lindgren, F.; Rue, H.; Lindström, J. An Explicit Link between Gaussian Fields and Gaussian Markov Random Fields: The Stochastic Partial Differential Equation Approach. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B (Statistical Methodol. 2011, 73, 423–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulain, P.-M.; Mauri, E.; Gerin, R.; Chiggiato, J.; Schroeder, K.; Griffa, A.; Borghini, M.; Zambianchi, E.; Falco, P.; Testor, P.; et al. On the dynamics in the southeastern Ligurian Sea in summer 2010. Cont. Shelf Res. 2020, 196, 104083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapucci, C.; Rella, M.A.; Brandini, C.; Ganzin, N.; Gozzini, B.; Maselli, F.; Massi, L.; Nuccio, C.; Ortolani, A.; Trees, C. Evaluation of empirical and semi-analytical chlorophyll algorithms in the Ligurian and North Tyrrhenian Seas. J. Appl. Remote. Sens. 2012, 6, 063565–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Tejedor, M.; Velasco, J.E.; Angelats, E. Accurate Estimation of Chlorophyll-a Concentration in the Coastal Areas of the Ebro Delta (NW Mediterranean) Using Sentinel-2 and Its Application in the Selection of Areas for Mussel Aquaculture. Remote. Sens. 2022, 14, 5235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finley, A.; Banerjee, S. spBayes: Univariate and Multivariate Spatial-Temporal Modeling. R package version 0.4-8; 2024; DOI: 10.32614/CRAN.package.spBayes; https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=spBayes.

- Finley, A.O.; Banerjee, S.; E.GElfand, A. spBayesfor Large Univariate and Multivariate Point-Referenced Spatio-Temporal Data Models. J. Stat. Softw. 2015, 63, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro Jr PJ, Diggle P (2025). geoR: Analysis of Geostatistical Data. R package version 1.9-5; DOI:10.32614/CRAN.package.geoR; https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=geoR.

- Shi, Y.; Zhou, X.; Yang, X.; Shi, L.; Ma, S. Merging Satellite Ocean Color Data With Bayesian Maximum Entropy Method. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote. Sens. 2015, 8, 3294–3304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Wong, S.W. Spatio-temporal data fusion for the analysis of in situ and remote sensing data using the INLA-SPDE approach. Spat. Stat. 2024, 64, 100863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obenour, D.R.; Gronewold, A.D.; Stow, C.A.; Scavia, D. Using a Bayesian hierarchical model to improve Lake Erie cyanobacteria bloom forecasts. Water Resour. Res. 2014, 50, 7847–7860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Hu, X.; Chang, H.H.; Waller, L.A.; Belle, J.H.; Liu, Y. A Bayesian Downscaler Model to Estimate Daily PM2.5 Levels in the Conterminous US. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2018, 15, 1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Truong, P.N.; Heuvelink, G.B.; Pebesma, E. Bayesian area-to-point kriging using expert knowledge as informative priors. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinformation 2014, 30, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Stein, A.; Myers, D.E. Extension of spatial information, bayesian kriging and updating of prior variogram parameters. Environmetrics 1995, 6, 373–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Statistic | Estimated uncertainty (°C) |

| Min | 0.010 |

| 1st Qu. | 0.022 |

| Median | 0.091 |

| Mean | 0.101 |

| 3rd Qu. | 0.160 |

| Max | 0.221 |

| SD | 0.062 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).