Submitted:

20 July 2025

Posted:

22 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

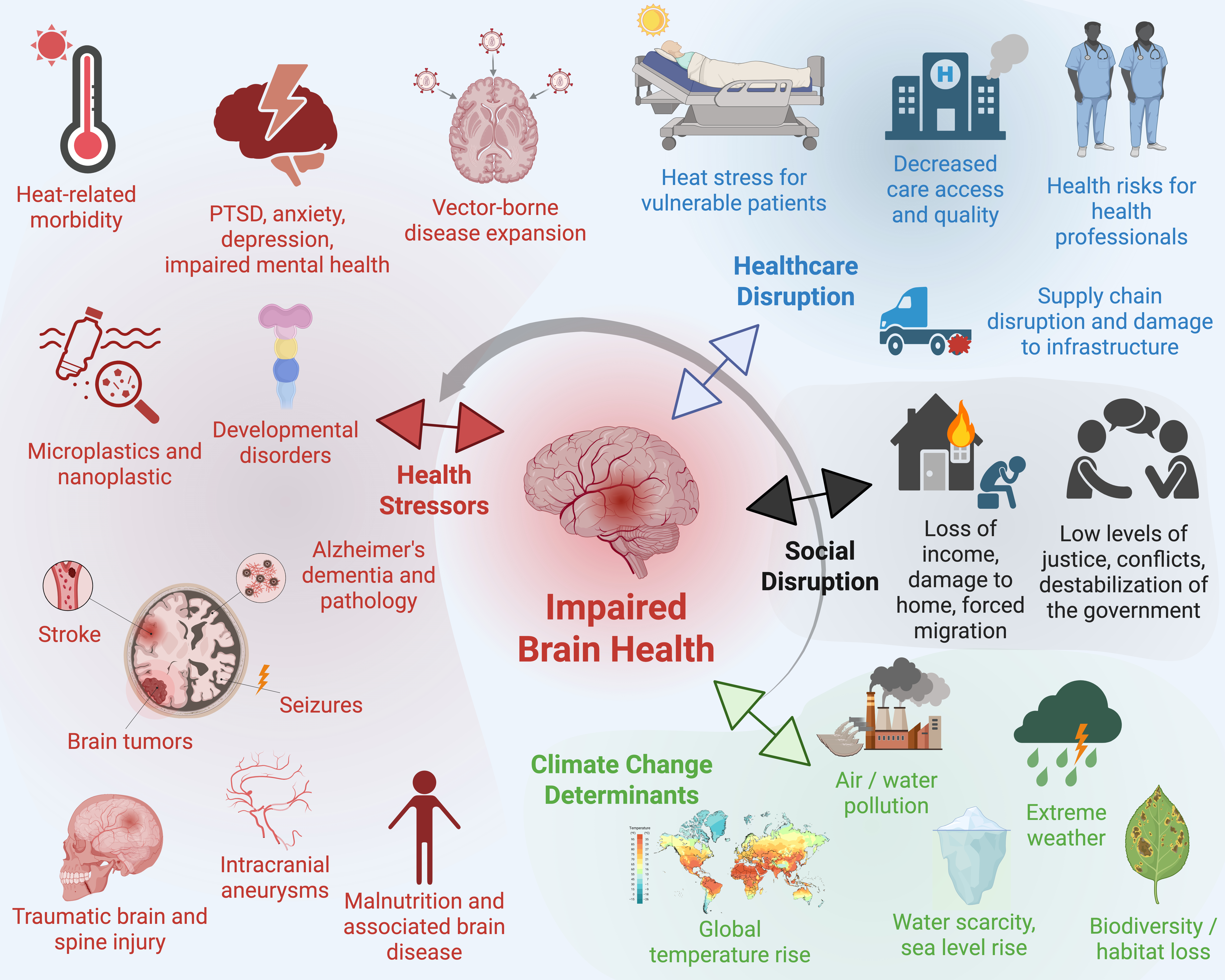

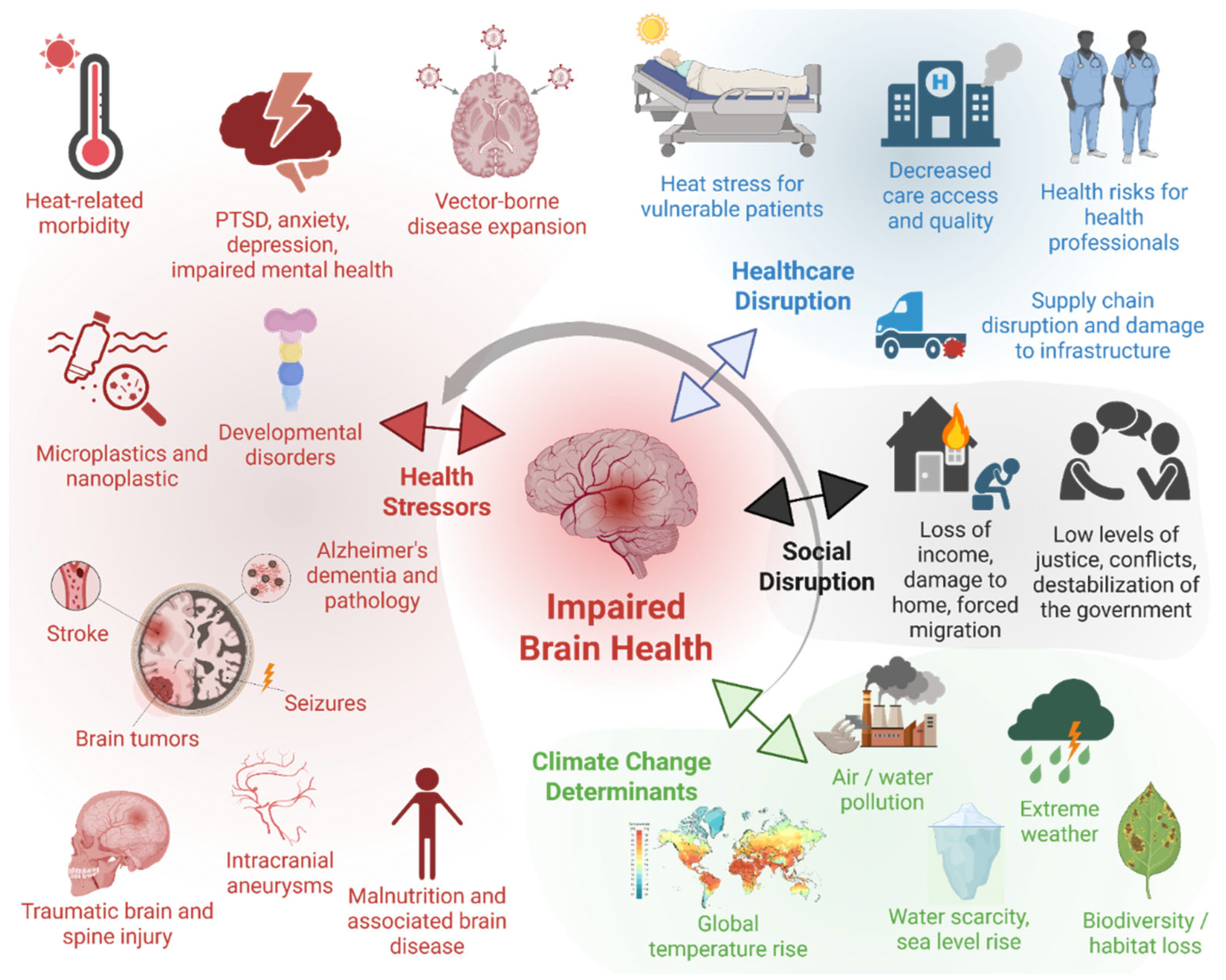

3. Mechanisms of Climate Change-Related Effects on Brain Health

4. Interdisciplinary Overview Including Disease-Specific Findings

Neurology

Psychiatry

Neurosurgery

Neuropediatrics

Neuropathology

Neuropsychology

Neuroradiology

5. Limitations

6. Perspectives and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- GBD 2021 Nervous System Disorders Collaborators; Steinmetz, J.D.; Seeher, K.M.; Schiess, N.; Nichols, E.; Cao, B.; Servili, C.; Cavallera, V.; Cousin, E.; Hagins, H.; et al. Global, regional, and national burden of disorders affecting the nervous system, 1990–2021: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet Neurol. 2024, 23, 344–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bassetti, C.L.A.; Heldner, M.R.; Adorjan, K.; Albanese, E.; Allali, G.; Arnold, M.; Bègue, I.; Bochud, M.; Chan, A.; Cuénod, K.Q. do; et al. The Swiss Brain Health Plan 2023–2033. Clin. Transl. Neurosci. 2023, 7, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization Optimizing brain health across the life course: WHO position paper; World Health Organization: Geneva, 2022.

- Sisodiya, S.M.; Gulcebi, M.I.; Fortunato, F.; Mills, J.D.; Haynes, E.; Bramon, E.; Chadwick, P.; Ciccarelli, O.; David, A.S.; Meyer, K.D.; et al. Climate change and disorders of the nervous system. Lancet Neurol. 2024, 23, 636–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watts, N.; Amann, M.; Arnell, N.; Ayeb-Karlsson, S.; Belesova, K.; Berry, H.; Bouley, T.; Boykoff, M.; Byass, P.; Cai, W.; et al. The 2018 report of the Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: shaping the health of nations for centuries to come. Lancet 2018, 392, 2479–2514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bathiany, S.; Dakos, V.; Scheffer, M.; Lenton, T.M. Climate models predict increasing temperature variability in poor countries. Sci. Adv. 2018, 4, eaar5809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Louis, S.; Carlson, A.K.; Suresh, A.; Rim, J.; Mays, M.; Ontaneda, D.; Dhawan, A. Impacts of Climate Change and Air Pollution on Neurologic Health, Disease, and Practice. Neurology 2023, 100, 474–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goenjian, A.K.; Molina, L.; Steinberg, A.M.; Fairbanks, L.A.; Alvarez, M.L.; Goenjian, H.A.; Pynoos, R.S. Posttraumatic Stress and Depressive Reactions Among Nicaraguan Adolescents After Hurricane Mitch. Am. J. Psychiatry 2001, 158, 788–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majeed, H.; Lee, J. The impact of climate change on youth depression and mental health. Lancet Planet. Heal. 2017, 1, e94–e95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souza, W.M. de; Weaver, S.C. Effects of climate change and human activities on vector-borne diseases. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2024, 22, 476–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paz, S. Climate change: A driver of increasing vector-borne disease transmission in non-endemic areas. PLOS Med. 2024, 21, e1004382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazmi, S.S.U.H.; Yapa, N.; Karunarathna, S.C.; Suwannarach, N. Perceived Intensification in Harmful Algal Blooms Is a Wave of Cumulative Threat to the Aquatic Ecosystems. Biology 2022, 11, 852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonak, S.; Patil, K.; Devi, P.; D’Souza, L. Causes, Human Health Impacts and Control of Harmful Algal Blooms: A Comprehensive Review. Environ. Pollut. Prot. 2018, 3, 40–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, M.; González, F.; Baylis, P.; Heft-Neal, S.; Baysan, C.; Basu, S.; Hsiang, S. Higher temperatures increase suicide rates in the United States and Mexico. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2018, 8, 723–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collaborators, G. 2021 S.R.F.; Feigin, V.L.; Abate, M.D.; Abate, Y.H.; ElHafeez, S.A.; Abd-Allah, F.; Abdelalim, A.; Abdelkader, A.; Abdelmasseh, M.; Abd-Elsalam, S.; et al. Global, regional, and national burden of stroke and its risk factors, 1990–2021: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet Neurol. 2024, 23, 973–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranta, A.; Kang, J.; Saad, A.; Wasay, M.; Béjot, Y.; Ozturk, S.; Giroud, M.; Reis, J.; Douwes, J. Climate Change and Stroke: A Topical Narrative Review. Stroke 2024, 55, 1118–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulick, E.R.; Kaufman, J.D.; Sack, C. Ambient Air Pollution and Stroke: An Updated Review. Stroke 2023, 54, 882–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GBD 2019 Dementia Forecasting Collaborators; Nichols, E. ; Steinmetz, J.D.; Vollset, S.E.; Fukutaki, K.; Chalek, J.; Abd-Allah, F.; Abdoli, A.; Abualhasan, A.; Abu-Gharbieh, E.; et al. Estimation of the global prevalence of dementia in 2019 and forecasted prevalence in 2050: an analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Public Heal 2022, 7, e105–e125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henrotin, J.-B.; Zeller, M.; Lorgis, L.; Cottin, Y.; Giroud, M.; Béjot, Y. Evidence of the role of short-term exposure to ozone on ischaemic cerebral and cardiac events: the Dijon Vascular Project (DIVA). Heart 2010, 96, 1990–1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Royé, D.; Zarrabeitia, M.T.; Riancho, J.; Santurtún, A. A time series analysis of the relationship between apparent temperature, air pollutants and ischemic stroke in Madrid, Spain. Environ. Res. 2019, 173, 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, X.; Chen, R.; Yuan, J.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ji, X.; Kan, H.; Zhao, J. Hourly Heat Exposure and Acute Ischemic Stroke. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e240627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowland, S.T.; Chillrud, L.G.; Boehme, A.K.; Wilson, A.; Rush, J.; Just, A.C.; Kioumourtzoglou, M.-A. Can weather help explain “why now?”: The potential role of hourly temperature as a stroke trigger. Environ. Res. 2022, 207, 112229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christensen, G.M.; Li, Z.; Liang, D.; Ebelt, S.; Gearing, M.; Levey, A.I.; Lah, J.J.; Wingo, A.; Wingo, T.; Hüls, A. Association of PM 2.5 Exposure and Alzheimer Disease Pathology in Brain Bank Donors—Effect Modification by APOE Genotype. Neurology 2024, 102, e209162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuijpers, P.; Kumar, M.; Karyotaki, E. Climate Change and Mental Health—Time to Act Now. JAMA Psychiatry 2023, 80, 1183–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, K.; Blashki, G.; Wiseman, J.; Burke, S.; Reifels, L. Climate change and mental health: risks, impacts and priority actions. Int. J. Ment. Heal. Syst. 2018, 12, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bundo, M.; Schrijver, E. de; Federspiel, A.; Toreti, A.; Xoplaki, E.; Luterbacher, J.; Franco, O.H.; Müller, T.; Vicedo-Cabrera, A.M. Ambient temperature and mental health hospitalizations in Bern, Switzerland: A 45-year time-series study. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0258302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golitaleb, M.; Mazaheri, E.; Bonyadi, M.; Sahebi, A. Prevalence of Post-traumatic Stress Disorder After Flood: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 890671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bär, S.; Bundo, M.; Schrijver, E. de; Müller, T.J.; Vicedo-Cabrera, A.M. Suicides and ambient temperature in Switzerland: A nationwide time-series analysis. Swiss Méd. Wkly. 2022, 152, w30115–w30115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clayton, S. Climate anxiety: Psychological responses to climate change. J. Anxiety Disord. 2020, 74, 102263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berry, H.L.; Waite, T.D.; Dear, K.B.G.; Capon, A.G.; Murray, V. The case for systems thinking about climate change and mental health. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2018, 8, 282–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, G.; Sartore, G.-M.; Connor, L.; Higginbotham, N.; Freeman, S.; Kelly, B.; Stain, H.; Tonna, A.; Pollard, G. Solastalgia: the distress caused by environmental change. Australas. Psychiatry 2009, 15, S95–S98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clayton, S.; Manning, C.; Krygsman, K.; Speiser, M. Mental Health And Our Changing Climate: Impacts, Implications, and Guidance - ClimaHealth; American Psychological Association, and ecoAmerica: Washington, D.C, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Fritze, J.G.; Blashki, G.A.; Burke, S.; Wiseman, J. Hope, despair and transformation: Climate change and the promotion of mental health and wellbeing. Int. J. Ment. Heal. Syst. 2008, 2, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palinkas, L.A.; Wong, M. Global climate change and mental health. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2020, 32, 12–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, R.D.; Broderick, J.P. Unruptured intracranial aneurysms: epidemiology, natural history, management options, and familial screening. Lancet Neurol. 2014, 13, 393–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kockler, M.; Schlattmann, P.; Walther, M.; Hagemann, G.; Becker, P.N.; Rosahl, S.; Witte, O.W.; Schwab, M.; Rakers, F. Weather conditions associated with subarachnoid hemorrhage: a multicenter case-crossover study. BMC Neurol. 2021, 21, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, M.-H.; Kim, J.; Choi, K.-S.; Kim, C.H.; Kim, J.M.; Cheong, J.H.; Yi, H.-J.; Lee, S.H. Monthly variations in aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage incidence and mortality: Correlation with weather and pollution. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0186973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piters, W.A.A. de S.; Algra, A.; Broek, M.F.M. van den; Mees, S.M.D.; Rinkel, G.J.E. Seasonal and meteorological determinants of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Neurol. 2013, 260, 614–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, R.; Chen, X.; Zhao, Y. Potential triggering factors associated with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: A large single-center retrospective study. J. Clin. Hypertens. 2022, 24, 861–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.-N.; Ling, F. Zika Virus Infection and Microcephaly: Evidence for a Causal Link. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2016, 13, 1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- VHP, L.; Aragão, M.; Pinho, R.; Hazin, A.; Paciorkowski, A.; Oliveira, A.P. de; Masruha, M.R. Congenital Zika Virus Infection: a Review with Emphasis on the Spectrum of Brain Abnormalities. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 2020, 20, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarke, B.; Otto, F.; Stuart-Smith, R.; Harrington, L. Extreme weather impacts of climate change: an attribution perspective. Environ. Res.: Clim. 2022, 1, 012001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salam, A.; Wireko, A.A.; Jiffry, R.; Ng, J.C.; Patel, H.; Zahid, M.J.; Mehta, A.; Huang, H.; Abdul-Rahman, T.; Isik, A. The impact of natural disasters on healthcare and surgical services in low- and middle-income countries. Ann. Med. Surg. 2023, 85, 3774–3777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamrick, I.; Norton, D.; Birstler, J.; Chen, G.; Cruz, L.; Hanrahan, L. Association Between Dehydration and Falls. Mayo Clin. Proc.: Innov., Qual. Outcomes 2020, 4, 259–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Gu, S.; Bi, P.; Yang, J.; Liu, Q. Heat Waves and Morbidity: Current Knowledge and Further Direction-A Comprehensive Literature Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2015, 12, 5256–5283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization WHO global air quality guidelines: particulate matter (PM2.5 and PM10), ozone, nitrogen dioxide, sulfur dioxide and carbon monoxide; Geneva. 2021.

- Jaffe, D.A.; O’Neill, S.M.; Larkin, N.K.; Holder, A.L.; Peterson, D.L.; Halofsky, J.E.; Rappold, A.G. Wildfire and prescribed burning impacts on air quality in the United States. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 2020, 70, 583–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Zhu, M.; Ji, M.; Fan, J.; Xie, J.; Wei, X.; Jiang, X.; Xu, J.; Chen, L.; Yin, R.; et al. Air Pollution, Genetic Factors, and the Risk of Lung Cancer: A Prospective Study in the UK Biobank. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2021, 204, 817–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hiatt, R.A.; Beyeler, N. Cancer and climate change. Lancet Oncol. 2020, 21, e519–e527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Youogo, L.M.-A.K.; Parent, M.-E.; Hystad, P.; Villeneuve, P.J. Ambient air pollution and prostate cancer risk in a population-based Canadian case-control study. Environ. Epidemiology 2022, 6, e219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Praud, D.; Deygas, F.; Amadou, A.; Bouilly, M.; Turati, F.; Bravi, F.; Xu, T.; Grassot, L.; Coudon, T.; Fervers, B. Traffic-Related Air Pollution and Breast Cancer Risk: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Cancers 2023, 15, 927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kost, E.; Kundel, D.; Conz, R.F.; Mäder, P.; Krause, H.-M.; Six, J.; Mayer, J.; Hartmann, M. Soil microbial resistance and resilience to drought under organic and conventional farming. Eur. J. Soil Biol. 2024, 123, 103690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Jiang, K.; Wang, X.; Liu, D. Insecticide activity under changing environmental conditions: a meta-analysis. J. Pest Sci. 2024, 97, 1711–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maluvu, Z.M.; Oludhe, C.; Kisangau, D.; Maweu, J. Adaptation Strategies and Interventions to Increase Yield in Green Gram Production Under a Changing Climate in Eastern Kenya. Afr. J. Clim. Chang. Resour. Sustain. 2024, 3, 370–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidd, S.A.; Gong, J.; Massazza, A.; Bezgrebelna, M.; Zhang, Y.; Hajat, S. Climate change and its implications for developing brains – In utero to youth: A scoping review. J. Clim. Chang. Heal. 2023, 13, 100258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne-Sturges, D.C.; Marty, M.A.; Perera, F.; Miller, M.D.; Swanson, M.; Ellickson, K.; Cory-Slechta, D.A.; Ritz, B.; Balmes, J.; Anderko, L.; et al. Healthy Air, Healthy Brains: Advancing Air Pollution Policy to Protect Children’s Health. Am. J. Public Heal. 2019, 109, e1–e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartlett, S. Climate change and urban children: impacts and implications for adaptation in low- and middle-income countries. Environ. Urban. 2008, 20, 501–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auger, N.; Fraser, W.D.; Sauve, R.; Bilodeau-Bertrand, M.; Kosatsky, T. Risk of Congenital Heart Defects after Ambient Heat Exposure Early in Pregnancy. Environ. Heal. Perspect. 2017, 125, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderko, L.; Chalupka, S.; Du, M.; Hauptman, M. Climate changes reproductive and children’s health: a review of risks, exposures, and impacts. Pediatr. Res. 2020, 87, 414–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sisodiya, S.M. Climate change and the brain. Brain 2023, 146, 1731–1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perera, F.P.; Chang, H.; Tang, D.; Roen, E.L.; Herbstman, J.; Margolis, A.; Huang, T.-J.; Miller, R.L.; Wang, S.; Rauh, V. Early-Life Exposure to Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons and ADHD Behavior Problems. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e111670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perera, F.P.; Li, Z.; Whyatt, R.; Hoepner, L.; Wang, S.; Camann, D.; Rauh, V. Prenatal Airborne Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon Exposure and Child IQ at Age 5 Years. Pediatrics 2009, 124, e195–e202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peterson, B.S.; Rauh, V.A.; Bansal, R.; Hao, X.; Toth, Z.; Nati, G.; Walsh, K.; Miller, R.L.; Arias, F.; Semanek, D.; et al. Effects of Prenatal Exposure to Air Pollutants (Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons) on the Development of Brain White Matter, Cognition, and Behavior in Later Childhood. JAMA Psychiatry 2015, 72, 531–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perera, F.P. Multiple Threats to Child Health from Fossil Fuel Combustion: Impacts of Air Pollution and Climate Change. Environ. Heal. Perspect. 2017, 125, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marfella, R.; Prattichizzo, F.; Sardu, C.; Fulgenzi, G.; Graciotti, L.; Spadoni, T.; D’Onofrio, N.; Scisciola, L.; Grotta, R.L.; Frigé, C.; et al. Microplastics and Nanoplastics in Atheromas and Cardiovascular Events. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 390, 900–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, J.; Suh, S. Strategies to reduce the global carbon footprint of plastics. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2019, 9, 374–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Wang, C.; Duan, X.; Liang, B.; Xu, E.G.; Huang, Z. Micro- and nanoplastics: A new cardiovascular risk factor? Environ. Int. 2023, 171, 107662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Donkelaar, A. van; Hammer, M.S.; McDuffie, E.E.; Burnett, R.T.; Spadaro, J.V.; Chatterjee, D.; Cohen, A.J.; Apte, J.S.; Southerland, V.A.; et al. Reversal of trends in global fine particulate matter air pollution. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 5349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thal, D.R.; Rüb, U.; Orantes, M.; Braak, H. Phases of Aβ-deposition in the human brain and its relevance for the development of AD. Neurology 2002, 58, 1791–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braak, H.; Alafuzoff, I.; Arzberger, T.; Kretzschmar, H.; Tredici, K.D. Staging of Alzheimer disease-associated neurofibrillary pathology using paraffin sections and immunocytochemistry. Acta Neuropathol. 2006, 112, 389–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gatto, N.M.; Ogata, P.; Lytle, B. Farming, Pesticides, and Brain Cancer: A 20-Year Updated Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analysis. Cancers 2021, 13, 4477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mora, C.; McKenzie, T.; Gaw, I.M.; Dean, J.M.; Hammerstein, H. von; Knudson, T.A.; Setter, R.O.; Smith, C.Z.; Webster, K.M.; Patz, J.A.; et al. Over half of known human pathogenic diseases can be aggravated by climate change. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2022, 12, 869–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiyatkin, E.A.; Brown, P.L.; Wise, R.A. Brain temperature fluctuation: a reflection of functional neural activation. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2002, 16, 164–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Core Writing Team; Lee, H. ; Romero, J. IPCC, 2023: Sections. In: Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 35–115;

- Karnauskas, K.B.; Miller, S.L.; Schapiro, A.C. Fossil Fuel Combustion Is Driving Indoor CO2 Toward Levels Harmful to Human Cognition. GeoHealth 2020, 4, e2019GH000237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doherty, T.J.; Clayton, S. The Psychological Impacts of Global Climate Change. Am. Psychol. 2011, 66, 265–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reser, J.P.; Swim, J.K. Adapting to and Coping With the Threat and Impacts of Climate Change. Am. Psychol. 2011, 66, 277–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Treble, M.; Cosma, A.; Martin, G. Child and Adolescent Psychological Reactions to Climate Change: A Narrative Review Through an Existential Lens. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2023, 25, 357–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leiserowitz, A. Climate Change Risk Perception and Policy Preferences: The Role of Affect, Imagery, and Values. Clim. Chang. 2006, 77, 45–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, E.U. What shapes perceptions of climate change? Wiley Interdiscip. Rev.: Clim. Chang. 2010, 1, 332–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C.; Dietz, T.; Abel, T.D.; Guagnano, G.; Kalof, L. A Value-Belief-Norm Theory of Support for Social Movements: The Case of Environmentalism. Human Ecology Review 1999, 6, 81–97. [Google Scholar]

- Gifford, R. The Dragons of Inaction. Am. Psychol. 2011, 66, 290–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ford, J.D. Indigenous Health and Climate Change. Am. J. Public Heal. 2012, 102, 1260–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Astone, R.; Vaalavuo, M. Climate Change and Health: Consequences of High Temperatures among Vulnerable Groups in Finland. Int. J. Soc. Determinants Heal. Heal. Serv. 2022, 53, 94–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basu, R.; Samet, J.M. Relation between Elevated Ambient Temperature and Mortality: A Review of the Epidemiologic Evidence. Epidemiologic Rev. 2002, 24, 190–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charlson, F.; Ali, S.; Benmarhnia, T.; Pearl, M.; Massazza, A.; Augustinavicius, J.; Scott, J.G. Climate Change and Mental Health: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2021, 18, 4486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansen, A.; Bi, L.; Saniotis, A.; Nitschke, M. Vulnerability to extreme heat and climate change: is ethnicity a factor? Glob. Heal. Action 2013, 6, 21364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McEwen, B.S.; Gianaros, P.J. Central role of the brain in stress and adaptation: Links to socioeconomic status, health, and disease. Ann. N. York Acad. Sci. 2010, 1186, 190–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Semenza, J.C.; Suk, J.E.; Estevez, V.; Ebi, K.L.; Lindgren, E. Mapping Climate Change Vulnerabilities to Infectious Diseases in Europe. Environ. Heal. Perspect. 2012, 120, 385–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Power, M.C.; Adar, S.D.; Yanosky, J.D.; Weuve, J. Exposure to air pollution as a potential contributor to cognitive function, cognitive decline, brain imaging, and dementia: A systematic review of epidemiologic research. NeuroToxicology 2016, 56, 235–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paterson, J.; Berry, P.; Ebi, K.; Varangu, L. Health Care Facilities Resilient to Climate Change Impacts. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2014, 11, 13097–13116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salas, R.N.; Burke, L.G.; Phelan, J.; Wellenius, G.A.; Orav, E.J.; Jha, A.K. Impact of extreme weather events on healthcare utilization and mortality in the United States. Nat. Med. 2024, 30, 1118–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitmee, S.; Haines, A.; Beyrer, C.; Boltz, F.; Capon, A.G.; Dias, B.F. de S.; Ezeh, A.; Frumkin, H.; Gong, P.; Head, P.; et al. Safeguarding human health in the Anthropocene epoch: report of The Rockefeller Foundation–Lancet Commission on planetary health. Lancet 2015, 386, 1973–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sveikata, L.; Bègue, I.; Guzman, R.; Remonda, L.; Bassetti, C.L. Changing the landscape of neurological education. Lancet Neurol. 2024, 23, 1078–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bègue, I.; Flahault, A.; Bolon, I.; Castañeda, R.R. de; Vicedo-Cabrera, A.M.; Bassetti, C.L.A. One brain, one mind, one health, one planet—a call from Switzerland for a systemic approach in brain health research, policy and practice. Lancet Reg. Heal. - Eur. 2025, 50, 101229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, F.; Wang, Y.; Du, X. Changes in healthy effects and economic burden of PM2.5 in Beijing after COVID-19. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 60294–60302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venter, Z.S.; Aunan, K.; Chowdhury, S.; Lelieveld, J. COVID-19 lockdowns cause global air pollution declines. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2020, 117, 18984–18990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, R.; Masselot, P.; Vicedo-Cabrera, A.M.; Sera, F.; Blangiardo, M.; Forlani, C.; Douros, J.; Jorba, O.; Adani, M.; Kouznetsov, R.; et al. Differential impact of government lockdown policies on reducing air pollution levels and related mortality in Europe. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Accorroni, A.; Nencha, U.; Bègue, I. The Interdisciplinary Synergy Between Neurology and Psychiatry: Advancing Brain Health. Clin. Transl. Neurosci. 2025, 9, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, C.; MacNeill, A.J.; Hughes, F.; Alqodmani, L.; Charlesworth, K.; Almeida, R. de; Harris, R.; Jochum, B.; Maibach, E.; Maki, L.; et al. Learning to treat the climate emergency together: social tipping interventions by the health community. Lancet Planet. Heal. 2023, 7, e251–e264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kioumourtzoglou, M.-A.; Schwartz, J.D.; Weisskopf, M.G.; Melly, S.J.; Wang, Y.; Dominici, F.; Zanobetti, A. Long-term PM2.5 Exposure and Neurological Hospital Admissions in the Northeastern United States. Environ. Heal. Perspect. 2016, 124, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, L.; Wu, X.; Yazdi, M.D.; Braun, D.; Awad, Y.A.; Wei, Y.; Liu, P.; Di, Q.; Wang, Y.; Schwartz, J.; et al. Long-term effects of PM2·5 on neurological disorders in the American Medicare population: a longitudinal cohort study. Lancet Planet. Heal. 2020, 4, e557–e565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munro, A.; Kovats, R.S.; Rubin, G.J.; Waite, T.D.; Bone, A.; Armstrong, B.; Group, E.N.S. of F. and H.S.; Waite, T.D.; Beck, C.R.; Bone, A.; et al. Effect of evacuation and displacement on the association between flooding and mental health outcomes: a cross-sectional analysis of UK survey data. Lancet Planet. Heal. 2017, 1, e134–e141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erazo, D.; Grant, L.; Ghisbain, G.; Marini, G.; Colón-González, F.J.; Wint, W.; Rizzoli, A.; Bortel, W.V.; Vogels, C.B.F.; Grubaugh, N.D.; et al. Contribution of climate change to the spatial expansion of West Nile virus in Europe. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lukan, M.; Bullova, E.; Petko, B. Climate Warming and Tick-borne Encephalitis, Slovakia - Volume 16, Number 3—March 2010 - Emerging Infectious Diseases journal - CDC. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2010, 16, 524–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, P.H.; Kwark, R.; Marick, H.M.; Davis, J.; Stark, J.H.; Madhava, H.; Dobler, G.; Moïsi, J.C. Different environmental factors predict the occurrence of tick-borne encephalitis virus (TBEV) and reveal new potential risk areas across Europe via geospatial models. Int. J. Heal. Geogr. 2025, 24, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suryawan, A.; Jalaludin, M.Y.; Poh, B.K.; Sanusi, R.; Tan, V.M.H.; Geurts, J.M.; Muhardi, L. Malnutrition in early life and its neurodevelopmental and cognitive consequences: a scoping review. Nutr. Res. Rev. 2021, 35, 136–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camille, C.; Ghislaine, B.; Yolande, E.; Clément, P.; Lucile, M.; Camille, P.; Pascale, F.-P.; Pierre, L.; Isabelle, B. Residential proximity to agricultural land and risk of brain tumor in the general population. Environ. Res. 2017, 159, 321–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burke, M.; Childs, M.L.; Cuesta, B. de la; Qiu, M.; Li, J.; Gould, C.F.; Heft-Neal, S.; Wara, M. The contribution of wildfire to PM2.5 trends in the USA. Nature 2023, 622, 761–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazhin, S.A.; Khankeh, H.; Farrokhi, M.; Aminizadeh, M.; Poursadeqiyan, M. Migration health crisis associated with climate change: A systematic review. J. Educ. Heal. Promot. 2020, 9, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fransen, S.; Hunns, A.; Jaber, T.; Janz, T. Climate risks for displaced populations: a scoping review and research agenda. J. Refug. Stud. 2024, feae074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astell-Burt, T.; Feng, X. Association of Urban Green Space With Mental Health and General Health Among Adults in Australia. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e198209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maes, J.; Zulian, G.; Günther, S.; Thijssen, M.; Raynal, J. Enhancing Resilience Of UrbanEcosystems through Green Infrastructure. Final Report, EUR 29630 EN; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Banwell, N.; Michel, S.; Senn, N. Greenspaces and Health: Scoping Review of studies in Europe. Public Heal. Rev. 2024, 45, 1606863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araújo, L.D.; Zanotta, D.C.; Ray, N.; Veronez, M.R. Earth observation data uncover green spaces’ role in mental health. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 20933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barboza, E.P.; Cirach, M.; Khomenko, S.; Iungman, T.; Mueller, N.; Barrera-Gómez, J.; Rojas-Rueda, D.; Kondo, M.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M. Green space and mortality in European cities: a health impact assessment study. Lancet Planet. Heal. 2021, 5, e718–e730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abebe, Y.A.; Pregnolato, M.; Jonkman, S.N. Flood impacts on healthcare facilities and disaster preparedness – A systematic review. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2025, 119, 105340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balikuddembe, J.K.; Zheng, Y.; Prisno, D.E.L.; Stodden, R. Impact of climate-induced floods and typhoons on geriatric disabling health among older Chinese and Filipinos: a cross-country systematic review. BMC Geriatr. 2024, 24, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Climate change stressors | Brain health impact | Mechanisms | Population and geographical area studied | Adaptation strategies | Future research directions | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extreme temperatures (heat/cold), heatwaves | ↑ Stroke (especially ischemic):

↑ hospitalizations in dementia ↑ dehydration and risk of falls ↑ Heat-related mental morbidity in people with impaired thermoregulation, namely with pre-existing mental health illness and taking prescription medications (lithium, neuroleptic, anticholinergic) or substance abuse (alcohol and drugs)

|

|

|

|

|

[6,16,17,20,21,22,45,57] |

| Air pollution (e.g., PM2.5, NO₂) | ↑ Stroke ↑ Burden of Alzheimer’s pathology

↑ Developmental disorders ↑ Neuroinflammatory CNS disease (e.g. multiple sclerosis) |

|

|

|

|

[7,19,23,68,101,102] |

| Natural disasters (e.g. earthquakes, floods) | ↑ PTSD, depression, anxiety, suicide ↑ TBI/spinal trauma |

|

|

|

|

[8,9,27,42,103] |

| Vector-borne disease expansion | ↑ CNS infections (e.g., Zika, Tick-borne encephalitis), epilepsy, encephalitis |

|

|

|

|

[10,11,40,41,89,104,105,106] |

| Food insecurity / malnutrition | Developmental delay ↑ Cognitive dysfunction Vulnerability to mental illness |

|

|

|

|

[56,57,58,64,107] |

| Exposure to neurotoxins (e.g., pesticides, algal toxins, wildfire smoke) | ↑ Brain tumors ↑ Developmental disorders ↑ Seizures ↑ Neurodegeneration |

|

|

|

|

[12,13,48,50,52,53,108,109] |

| Displacement / forced migration | ↑ Anxiety, PTSD, depression, adjustment disorder, psychosis |

|

|

|

|

[29,30,31,78,110,111] |

| Loss of green space/urbanization | ↑ Depression, anxiety, ↓ executive function and attention |

|

|

|

|

[25,26,32,74,112,113,114,115,116] |

| Healthcare Infrastructure Disruption | ↓ Stroke/thrombectomy care Delayed neuroimaging Medication and treatment interruption |

|

|

|

|

[85,86,91,92,117,118] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).