Submitted:

16 July 2025

Posted:

17 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Method

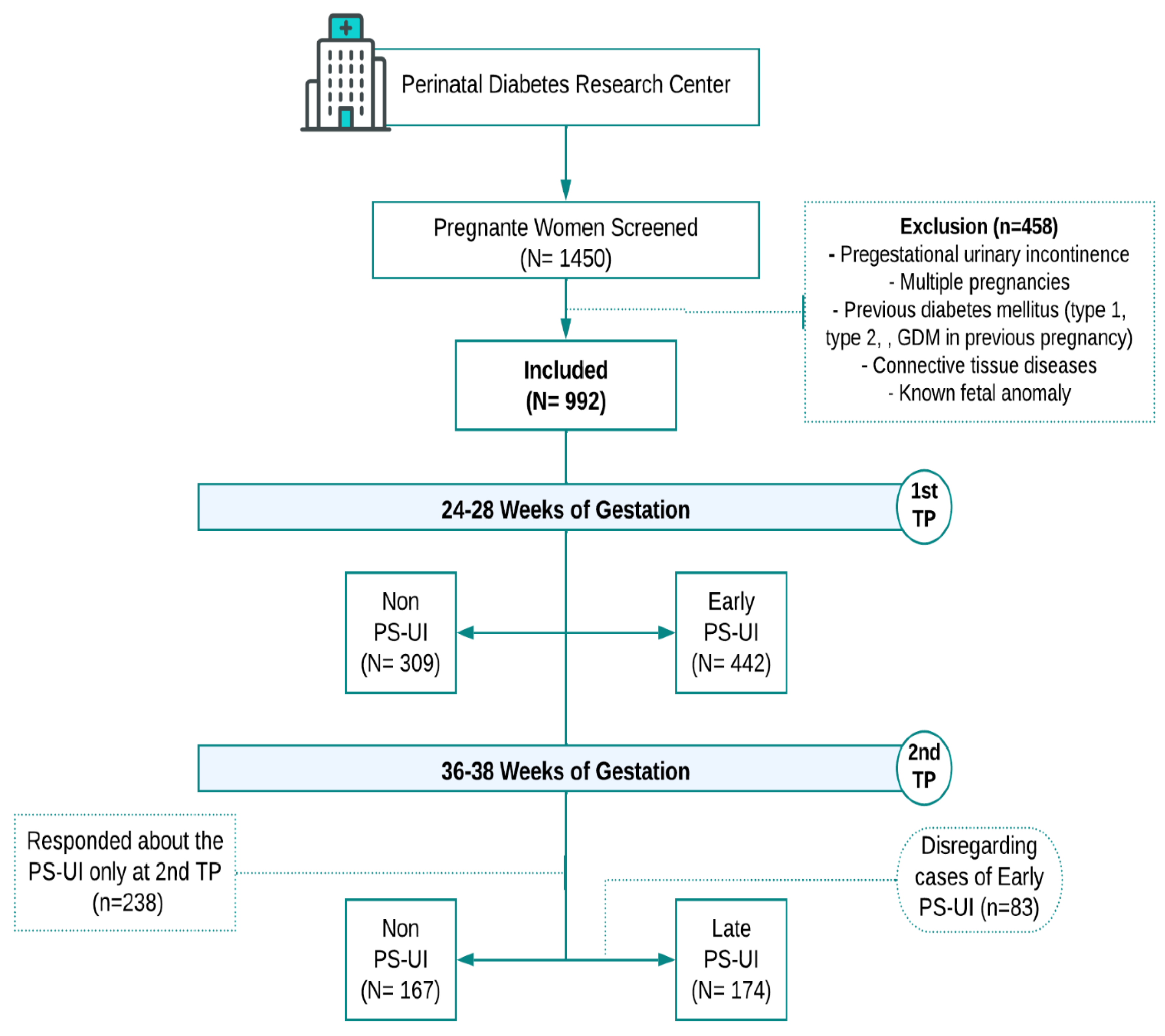

Research Design and Subjects

Data Collection

Statistical Analysis

Results

Discussion

Conclusion

Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

List of Abbreviations:

References

- Ali H, Ahmed A, Olivos C, Khamis K, Liu J. Mitigating urinary incontinence conditions using machine learning. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2022;22(1):243. [CrossRef]

- Milsom I, Altman D, Cartwright R, et al. Epidemiology of urinary incontinence (UI) and other lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS), pelvic organ prolapse (POP), and anal incontinence (AI). In: Abrams P, Cardozo L, Wagg A, Wein A, editors. Incontinence. 6th ed. International Continence Society; 2017. p. 4–142.

- Datar M, Pan LC, McKinney JL, Goss TF, Pulliam SJ. Healthcare resource use and cost burden of urinary incontinence to United States payers. Neurourol Urodyn. 2022;41(7):1553-1562. [CrossRef]

- Hvidman L, Foldspang A, Mommsen S, Bugge Nielsen J. Correlates of urinary incontinence in pregnancy. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2002;13(5):278-283. [CrossRef]

- Wesnes SL, Rortveit G, Bø K, Hunskaar S. Urinary incontinence during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109(4):922-928. [CrossRef]

- Chang SR, Lin WA, Chang TC, Lin HH, Lee CN, Lin MI. Risk factors for stress and urge urinary incontinence during pregnancy and the first year postpartum: a prospective longitudinal study. Int Urogynecol J. 2021;32(9):2455-2464. [CrossRef]

- Zhu L, Li L, Lang JH, Xu T. Prevalence and risk factors for peri- and postpartum urinary incontinence in primiparous women in China: a prospective longitudinal study. Int Urogynecol J. 2012;23(5):563-572. [CrossRef]

- Wang X, Jin Y, Xu P, Feng S. Urinary incontinence in pregnant women and its impact on health-related quality of life. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2022;20(1):13. [CrossRef]

- Nur Farihan M, Ng BK, Phon SE, Nor Azlin MI, Nur Azurah AG, Lim PS. Prevalence, Knowledge and Awareness of Pelvic Floor Disorder among Pregnant Women in a Tertiary Centre, Malaysia. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(14):8314. [CrossRef]

- Hage-Fransen MAH, Wiezer M, Otto A, et al. Pregnancy- and obstetric-related risk factors for urinary incontinence, fecal incontinence, or pelvic organ prolapse later in life: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2021;100(3):373-382. [CrossRef]

- Daly D, Clarke M, Begley C. Urinary incontinence in nulliparous women before and during pregnancy: prevalence, incidence, type, and risk factors. Int Urogynecol J. 2018;29(3):353-362. [CrossRef]

- Piculo F, Marini G, Vesentini G, et al. Pregnancy-specific urinary incontinence in women with gestational hyperglycemia worsens the occurrence and severity of urinary incontinence and quality of life over the first year postpartum. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2020;252:336-343. [CrossRef]

- Mason L, Glenn S, Walton I, Hughes C. Women’s reluctance to seek help for stress incontinence during pregnancy and following childbirth. Midwifery. 2001;17(3):212–221. [CrossRef]

- Anyanwu L-JJC, Anyanwu OM, Yakubu AA. Missed opportunities for breast awareness information among women attending the maternal and child health services of an urban tertiary hospital in Northern Nigeria. J Cancer Res Ther. 2016;12:765–769. [CrossRef]

- Nagraj S, Kennedy SH, Norton R, et al. Cardiometabolic Risk Factors in Pregnancy and Implications for Long-Term Health: Identifying the Research Priorities for Low-Resource Settings. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2020;7:40. [CrossRef]

- Tudor Car L, Van Velthoven MH, Brusamento S, et al. Integrating prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission programs to improve uptake: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e35268. [CrossRef]

- Rudge MVC, Souza FP, Abbade JF, et al. Study protocol to investigate biomolecular muscle profile as predictors of long-term urinary incontinence in women with gestational diabetes mellitus. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20(1):117. Published 2020 Feb 19. [CrossRef]

- Rudge MVC, Calderon I de MP, Ramos MD, et al. Hiperglicemia materna diária diagnosticada pelo perfil glicêmico: um problema de saúde pública materno e perinatal. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet. 2005;27(11):691-697. [CrossRef]

- International Association of Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Groups Consensus Panel, Metzger BE, Gabbe SG, et al. International association of diabetes and pregnancy study groups recommendations on the diagnosis and classification of hyperglycemia in pregnancy. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(3):676-682. [CrossRef]

- Abrams P, Cardozo L, Fall M, et al. The standardization of terminology in lower urinary tract function: report from the standardization sub-committee of the International Continence Society. Urology. 2003;61(1):37-49. [CrossRef]

- Pizzoferrato AC, Briant AR, Le Grand C, Gaichies L, Fauvet R, Fauconnier A, et al. Influence of prenatal urinary incontinence and mode of delivery in postnatal urinary incontinence: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod. 2023 Mar;52(3):102536. [CrossRef]

- Tahra A, Bayrak O, Dmochowski R. The Epidemiology and Population-Based Studies of Women with Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms: A Systematic Review. Türk Üroloji Dergisi/Turkish J Urol [Internet]. 2022 Apr 7;48(2):155–65. Available from: https://turkishjournalofurology.com/en/the-epidemiology-and-population-based-studies-of-women-with-lower-urinary-tract-symptoms-a-systematic-review-133793. [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, M. P., & Brensinger, C. M. What We Don’t Know About Pelvic Floor Disorders in Women. Obstetrics and GynecologyGynecology Clinics of North America. 2021; 48(4), 665-678. [CrossRef]

- Rafique S, Iqbal N, Alvi R. Risk factors for antenatal urinary incontinence in nulliparous women: A systematic review. Int J Womens Health. 2021;13:83-92.

- Baruch Y, Manodoro S, Barba M, Cola A, Re I, Frigerio M. Prevalence and Severity of Pelvic Floor Disorders during Pregnancy: Does the Trimester Make a Difference? Healthcare. 2023 Apr 11;11(8):1096. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira BL, Souza RT, Dutra LO, Moura CS. Urinary incontinence in obese women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Urogynecol J. 2020 Nov;31(11):2215-2224. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subak LL, Wing R, West DS, Franklin F, Vittinghoff E, Creasman JM, et al. Weight Loss to Treat Urinary Incontinence in Overweight and Obese Women. N Engl J Med. 2009 Jan 29;360(5):481–90. [CrossRef]

- Yazdany T, Jakus-Waldman S, Jeppson PC, Schimpf MO, Yurteri-Kaplan LA, Ferzandi TR, et al. American Urogynecologic Society Systematic Review: The Impact of Weight Loss Intervention on Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms and Urinary Incontinence in Overweight and Obese Women. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2020 Jan;26(1):16–29. [CrossRef]

| Variable | non PS-UI | PS-UI | p - value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Partnership status | Married | 311 (83.4%) | 515 (83.6%) | 0.926 | |

| Not married | 62 (16.6%) | 101 (16.4%) | |||

| Education level | basic level | 27 (7.2%) | 42 (6.9%) | 0.014 | |

| high school | 229 (61.1%) | 427 (69.7%) | |||

| college/university | 119 (31.7%) | 144 (23.5%) | |||

| Ethnicity | Caucasian | 299 (81%) | 495 (80.5%) | 0.835 | |

| Non-caucasian | 70 (19%) | 120 (19.5%) | |||

| Pregestational BMI (kg/m2) | 26.9 ± 6.25 | 28.48 ± 7.28 | 0.002 | ||

| BMI - 1st TP (kg/m2) | 29.4 ± 6.04 | 30.8 ± 6.85 | 0.004 | ||

| BMI - 2nd TP (kg/m2) | 31.6 ± 6.20 | 33.75 ± 6.51 | 0.002 | ||

| Gestational weight gain - 1st TP (kg) | 6.39 ± 5.04 | 6.08 ± 6.19 | 0.477 | ||

| Gestational weight gain - 2nd TP (kg) | 11.76 ± 7.34 | 11.36 ± 7.63 | 0.613 | ||

| Fasting blood glucose (mg/dL) | 79.48 ± 12.71 | 80.11 ± 14.44 | 0.583 | ||

| OGTT - fasting (mg/dL) | 74.82 ± 12.66 | 76.11 ± 11.06 | 0.161 | ||

| OGTT- 1 h (mg/dL) | 116.7 ± 31.27 | 119.17 ± 32.7 | 0.321 | ||

| OGTT - 2 h (mg/dL) | 105.08 ± 28.1 | 107.01± 8.88 | 0.378 | ||

| Chronic coughing | 0 | 9 (1.8%) | 0.025 | ||

| Constipation | 91 (31.5%) | 152 (28.9%) | 0.439 | ||

| Fecal incontinence | 3 (1.1%) | 6 (1.2%) | 0.887 | ||

| Previous arterial hypertension | 24 (8.3%) | 53 (10.2%) | 0.376 | ||

| Alcohol consumption | 1 (0.4%) | 9 (1.8%) | 0.091 | ||

| Smoking in pregnancy | 12 (4.3%) | 26 (5%) | 0.615 | ||

| Physical activity | 66 (23.1%) | 76 (14.7%) | 0.003 | ||

| Gestational diabetes mellitus | 81 (22%) | 154 (25.2%) | 0.242 | ||

| Pregnancy-induced hypertension | 2 (3%) | 8 (4.4%) | 0.611 | ||

| Urinary tract infection | 7 (10.8%) | 22 (12.4%) | 0.735 | ||

| Weeks of gestation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | |||

| 24-28 weeks | ||||

| 1st TP | (1) non PS-UI | 309 | 41.15 | |

| (2) Early PS-UI | 442 | 58.85 | ||

| 36-38 weeks | ||||

| 2nd TP | (1) non PS-UI | 167 | 49.0 | |

| (2) Late PS-UI | 174 | 51.0 | ||

| 1st and 2nd TP | ||||

| (1) non-PS-UI | 376 | 37.9 | ||

| (2) PS-UI | 616 | 62.1 |

| Variable | 1st TP | 2nd TP | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| non PS-UI (n=309) | Early PS-UI (n=442) | p-value | non PS-UI (n=167) | Late PS-UI (n=174) | p-value | |||

| Partnership status | Married | 261 (84.5%) | 367 (83%) | 0.601 | 136 (82.4%) | 148 (85.1%) | 0.511 | |

| Not-married | 48 (15.5%) | 75 (17%) | 29 (17.6%) | 26 (14.9%) | ||||

| Education level | basic level | 22 (7.1%) | 27 (6.1%) | 0.007 | 11 (6.6%) | 15 (8.7%) | 0.210 | |

| high school | 191 (61.8%) | 319 (72.5%) | 93 (55.7%) | 108 (62.4%) | ||||

| college/university | 96 (31.1%) | 94 (21.4%) | 63 (5.2%) | 50 (28.9%) | ||||

| Ethnicity | Caucasian | 253 (82.4%) | 365 (82.6%) | 0.952 | 124 (76.1%) | 130 (75.1%) | 0.843 | |

| Non-caucasian | 54 (17.6%) | 77 (17.4%) | 39 (23.9%) | 43 (24.9%) | ||||

| Pregestational BMI (kg/m2) | 27.04 ± 6.28 | 28.5 ± 7.33 | 0.003 | 27.31 ± 6.42 | 29.47 ± 6.69 | 0.003 | ||

| BMI - 1st TP (kg/m2) | 29.49 ± 6.1 | 30.83 ± 6.87 | 0.005 | 29.58 ± 6.8 | 30.24 ± 6.64 | 0.637 | ||

| BMI - 2nd TP (kg/m2) | 31.23 ± 6.76 | 33.49 ± 6.33 | 0.213 | 31.67 ± 6.2 | 33.92 ± 6.64 | 0.002 | ||

| Gestational weight gain - 1st TP (kg) | 6.31 ± 5.01 | 6.09 ± 6.26 | 0.614 | 6.18 ± 7.73 | 5.85 ± 4.97 | 0.833 | ||

| Gestational weight gain - 2nd TP (kg) | 10.81 ± 5.55 | 10.62 ± 8.76 | 0.863 | 11.6 ± 8.18 | 11.81 ± 6.83 | 0.802 | ||

| Fasting blood glucose (mg/dL) | 79.86 ± 12.4 | 79.42 ± 12.23 | 0.691 | 81.63 ± 13.26 | 82.12 ± 19.37 | 0.826 | ||

| OGTT - fasting (mg/dL) | 74.58 ± 12.83 | 75.77 ± 10.58 | 0.206 | 78.46 ± 11.73 | 77.84 ± 13.2 | 0.755 | ||

| OGTT- 1 h (mg/dL) | 115.65 ± 29.98 | 118.24 ± 32.9 | 0.311 | 126.02 ± 35.13 | 123.81 ± 31.5 | 0.755 | ||

| OGTT - 2 h (mg/dL) | 105.08 ± 26.77 | 106.19 ± 28.86 | 0.615 | 112.05 ± 33.39 | 111.15 ± 28.87 | 0.862 | ||

| Chronic coughing | 0 | 1 (0.3%) | 0.426 | 0 | 8 (6.7%) | 0.012 | ||

| Constipation | 79 (31.6%) | 113 (28.7%) | 0.430 | 27 (27.8%) | 39 (29.5%) | 0.778 | ||

| Fecal incontinence | 1 (0.4%) | 3 (0.8%) | 0.568 | 2 (2.2%) | 3 (2.5%) | 0.879 | ||

| Previous arterial hypertension | 17 (6.8%) | 29 (7.3%) | 0.795 | 12 (12.4%) | 24 (19.4%) | 0.163 | ||

| Alcohol | 1 (0.4%) | 4 (1%) | 0.391 | 0 | 5 (4.2%) | 0.047 | ||

| Smoking | 8 (3.2%) | 19 (4.8%) | 0.328 | 6 (6.6%) | 7 (5.9%) | 0.832 | ||

| Physical activity | 53 (21.4%) | 51 (12.8%) | 0.004 | 22 (22.9%) | 25 (20.7%) | 0.689 | ||

| Gestational diabetes mellitus | 70 (23.0%) | 103 (23.5%) | 0.877 | 116 (70.7%) | 121 (70.3%) | 0.939 | ||

| Pregnancy-induced hypertension | 0 | 3 (4.2%) | 0.185 | 3 (3.8%) | 5 (4.6%) | 0.778 | ||

| Urinary infection | 1 (2.6%) | 7 (9.5%) | 0.184 | 9 (11.3%) | 15 (14.4%) | 0.526 | ||

| Variable | Early PS-UI (n=442) | Late PS-UI (n=442) | PS-UI (1st plus 2nd TP) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR* | 95% CI** | p - value | OR* | 95% CI** | p - value | OR* | 95% CI** | p - value | ||||||

| Education level | basic level | |||||||||||||

| high school | 1.28 | 0.62 ; 2.63 | 0.172 | 0.62 | 0.04 | 9.28 | 0.491 | 1.21 | 0.58 ; 2.51 | 0.304 | ||||

| college/university | 0.89 | 0.40 ; 1;96 | 0.359 | 1.20 | 0.08 ; 19.02 | 0.629 | 0.91 | 0.41 ; 2.04 | 0.493 | |||||

| Ethnicity | Caucasian | 1.22 | 0.76 ; 1.96 | 0.416 | 2.65 | 0.46 ; 15.15 | 0.274 | 1.28 | 0.88 ; 0.78 | 0.519 | ||||

| Non-caucasian | ||||||||||||||

| Age (years) | 0.99 | 0.96 ; 1.02 | 0.375 | 1.01 | 0.92 ; 1.12 | 0.805 | 0.99 | 0.96 ; 1.03 | 0.706 | |||||

| Pregestational BMI | 1.03 | 1.01 ; 1.06 | 0.014 | 1.02 | 0.93 ; 1.11 | 0.716 | 1.04 | 1.01 ; 1.07 | 0.006 | |||||

| Constipation | 1.21 | 0.84 ; 0.83 | 0.312 | 1.02 | 0.26 ; 4.03 | 0.974 | 0.78 | 0.54 ; 1.13 | 0.193 | |||||

| Fecal incontinence | 3.02 | 0.29 ; 31.82 | 0.358 | 2.81 | 0.26 ; 29.92 | 0.392 | ||||||||

| Previous arterial hypertension | 0.83 | 0.41 ; 1.70 | 0.616 | 1.4 | 0.16 ; 12.32 | 0.761 | 0.84 | 0.41 ; 1.76 | 0.652 | |||||

| Smoking | 2.08 | 0.78 ; 5.53 | 0.141 | 1.85 | 0.69 ; 4.91 | 0.220 | ||||||||

| Physical activity | 0.51 | 0.32 ; 0.80 | 0.003 | 0.72 | 0.13 ; 3.88 | 0.700 | 0.5 | 0.32 ; 0.79 | 0.003 | |||||

| Gestational diabetes mellitus | 1.10 | 1.01 ; 1.06 | 0.649 | 0.94 | 0.25 ; 3.58 | 0.928 | 1.16 | 0.75 ; 1.81 | 0.500 | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).