Submitted:

08 July 2025

Posted:

09 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Acquisition

2.3. Model Description

2.3.1. Heat Flux Model Description

2.3.2. Morphodynamics and Sediment Transport Module Description

2.3.3. Configuration and Parameterization of Simulation Input Variables

3. Results and Discussion

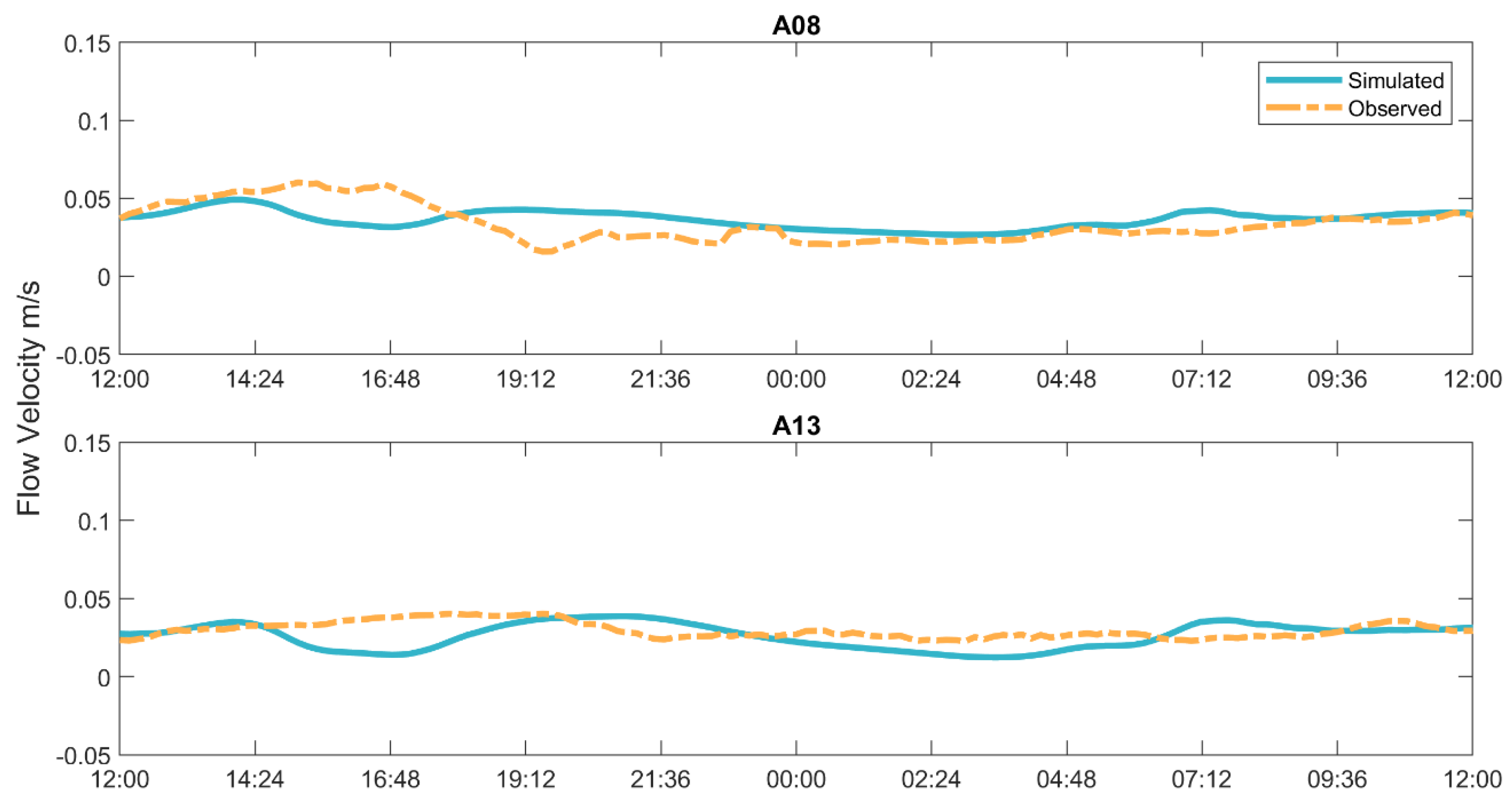

3.1. Calibration

3.2. Model Validation

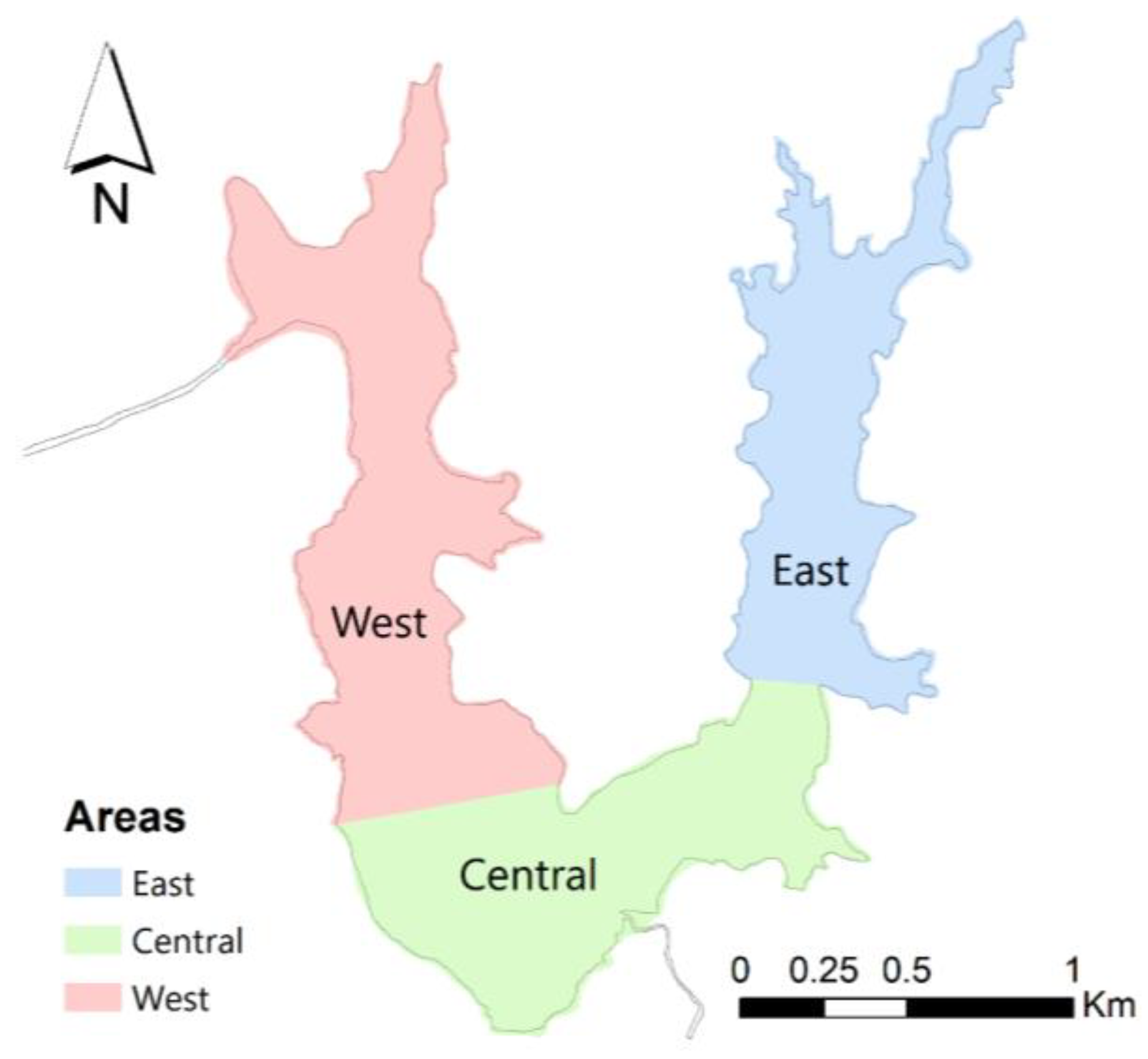

3.3. Setorização

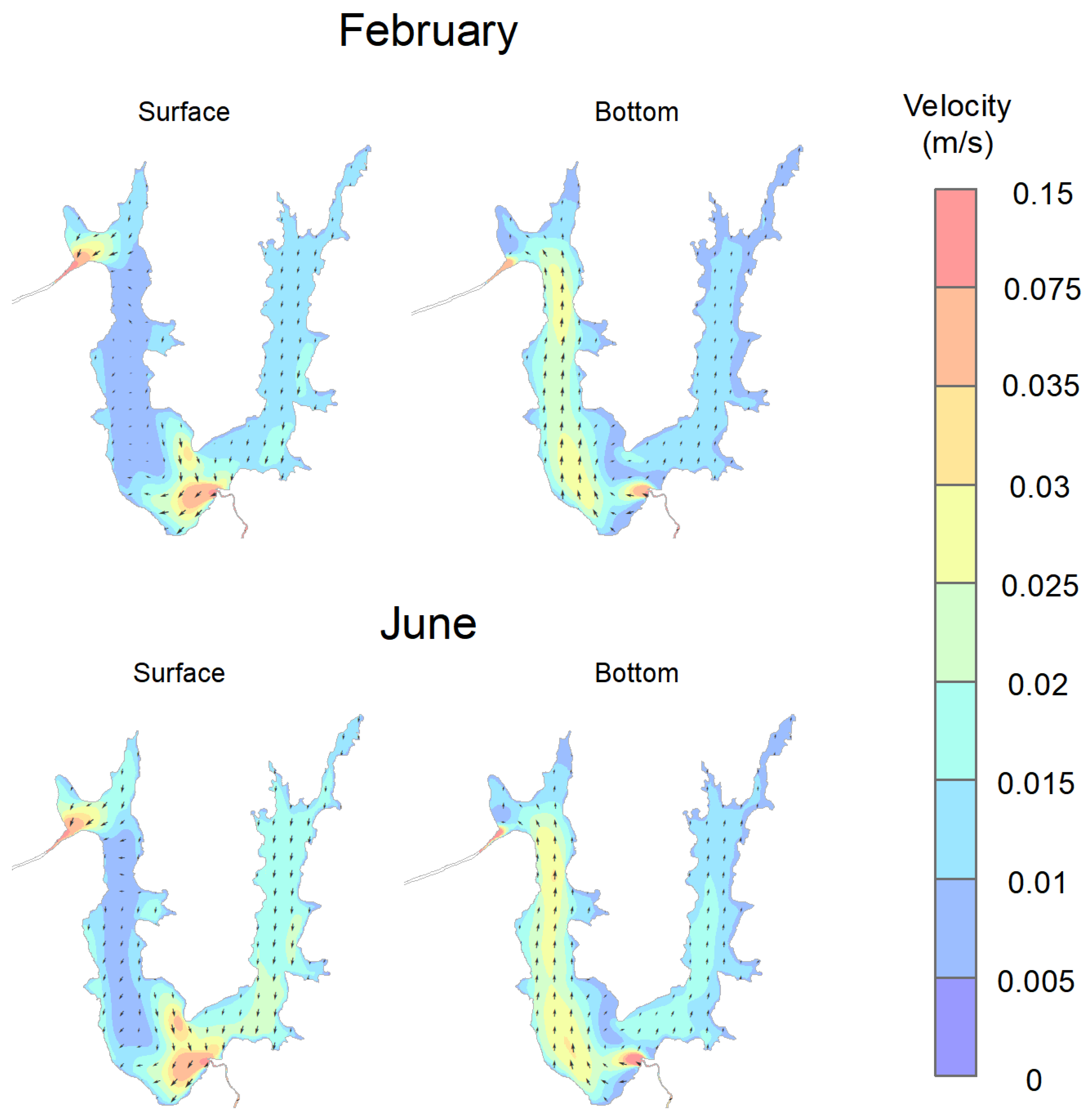

3.4. Circulation Patterns of Água Preta Lake

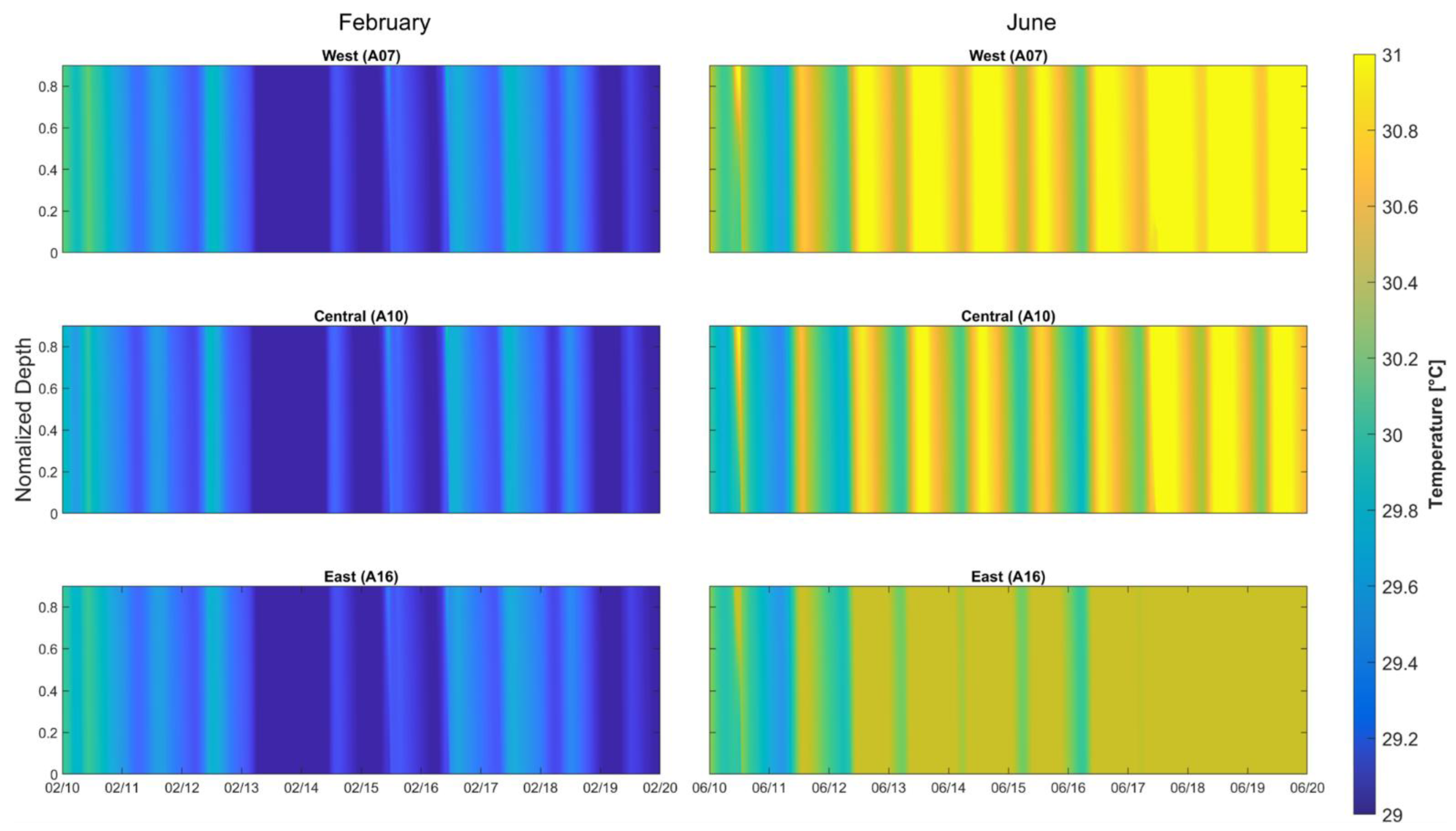

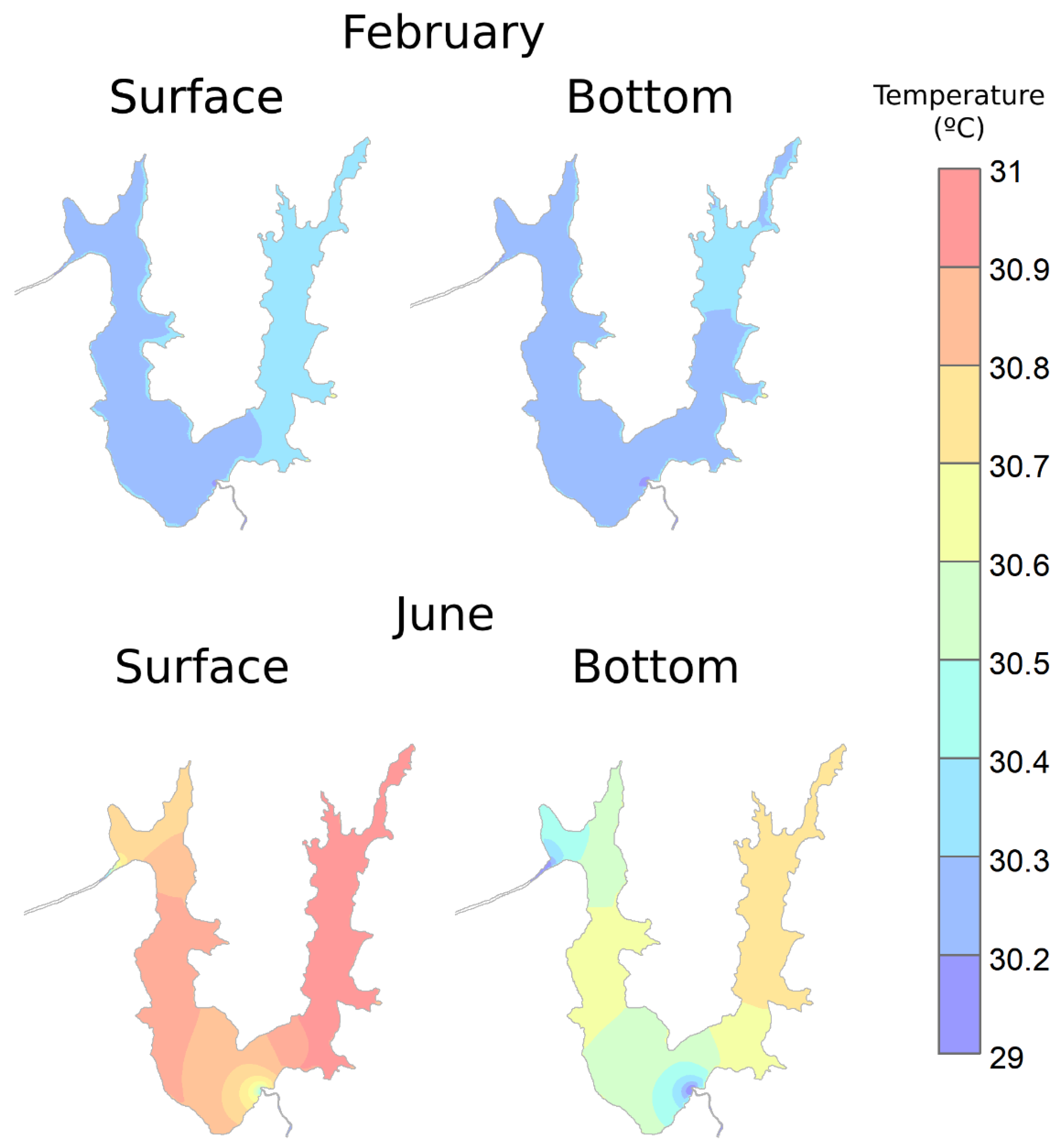

3.5. Temperature Patterns and Stratification

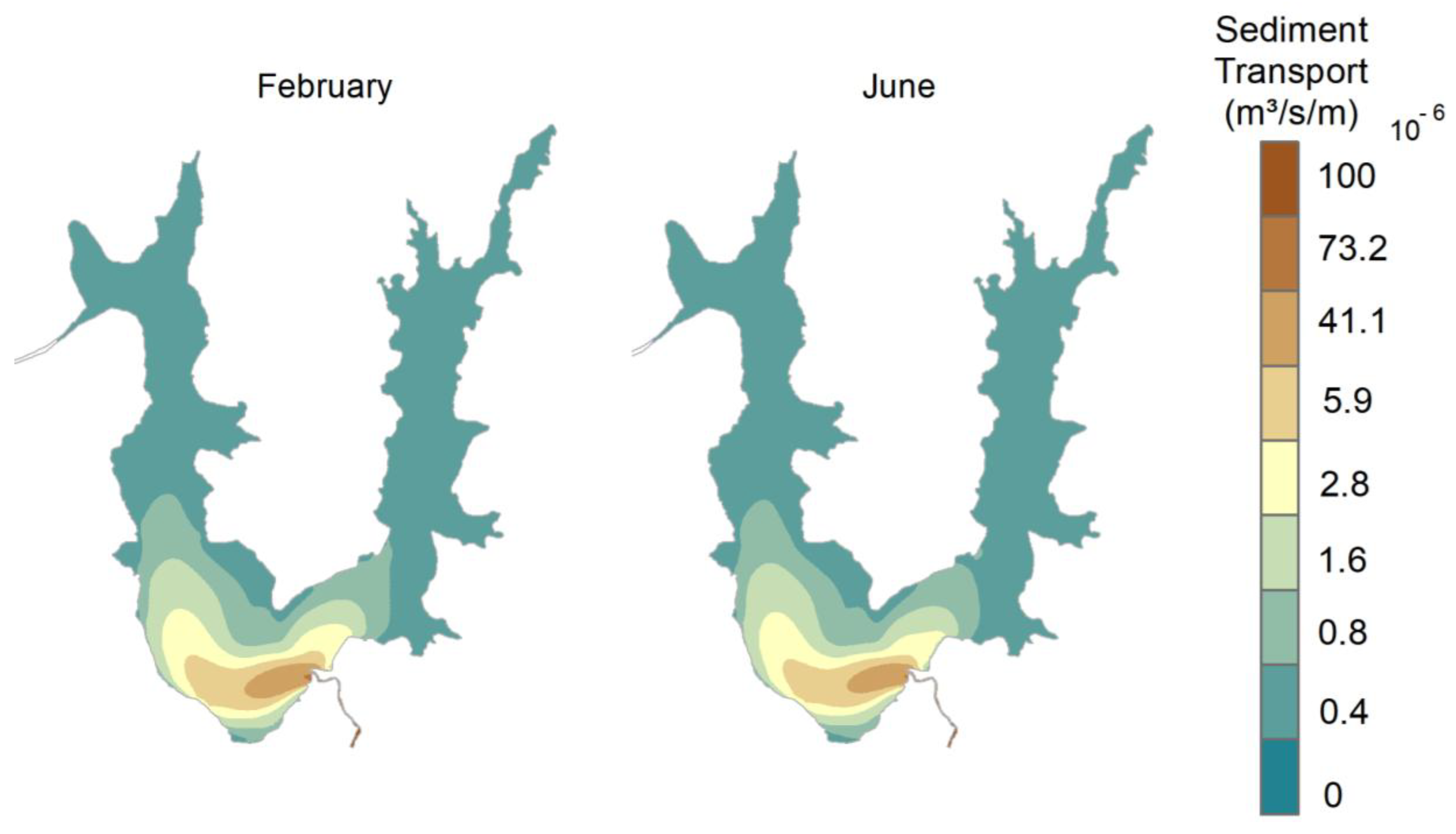

3.6. Transport and Sedimentation of Lake Água Preta

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Esteves, F.A. 1998. Fundamentos de limnologia. Interciência.

- Liu, S.; Ye, Q.; Wu, S.; Stive, M.J.F. Horizontal Circulation Patterns in a Large Shallow Lake: Taihu Lake, China. Water 2018, 10, 792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, M.C.; Hamilton, D.P. Wind Induced Sediment Resuspension: A Lake-Wide Model. Ecological Modelling 1997, 99, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, R. Thomas.; Martin, J.; Wool, T.; Wang, P.F. A Sediment Resuspension and Water Quality Model of Lake Okeechobee. JAWRA Journal of the American Water Resources Association 1997, 33, 661–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, B.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, G.; Gao, G. Eutrophication Control of Large Shallow Lakes in China. Science of The Total Environment 2023, 881, 163494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheffer, M.; van Nes, E.H. Shallow Lakes Theory Revisited: Various Alternative Regimes Driven by Climate, Nutrients, Depth and Lake Size. Hydrobiologia 2007, 584, 455–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, E.G.; Bombardelli, F.A.; Schladow, S.G. Sediment Resuspension in a Shallow Lake. Water Resources Research 2009, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Ding, W.; Xu, S.; Ruan, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, S. Prediction of Sediment Resuspension in Lake Taihu Using Support Vector Regression Considering Cumulative Effect of Wind Speed. Water Science and Engineering 2021, 14, 228–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Chen, L. A Review of Wind-Driven Hydrodynamics in Large Shallow Lakes: Importance, Process-Based Modeling and Perspectives. Cambridge Prisms: Water 2023, 1, e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naselli-Flores, L. Urban Lakes: Ecosystems at Risk, Worthy of the Best Care. Materials of the 12th World Lake Conference, Taal 2007 2008, 1333–1337.

- Zhao, L.; Li, T.; Przybysz, A.; Liu, H.; Zhang, B.; An, W.; Zhu, C. Effects of Urban Lakes and Neighbouring Green Spaces on Air Temperature and Humidity and Seasonal Variabilities. Sustainable Cities and Society 2023, 91, 104438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jandaghian, Z.; Colombo, A. The Role of Water Bodies in Climate Regulation: Insights from Recent Studies on Urban Heat Island Mitigation. Buildings 2024, 14, 2945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schirpke, U.; Tasser, E.; Ebner, M.; Tappeiner, U. What can geotagged photographs tell us about cultural ecosystem services of lakes? Ecosyst. Serv. 2021, 51, 101354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koue, J. Modeling the Effects of River Inflow Dynamics on the Deep Layers of Lake Biwa, Japan. Environ. Process. 2023, 10, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; Brereton, A.; Beckler, J.; Moore, T.; Brewton, R.A.; Hu, C.; Lapointe, B.E.; McFarland, M.N. Modeling Water Quality and Cyanobacteria Blooms in Lake Okeechobee: I. Model Descriptions, Seasonal Cycles, and Spatial Patterns. Ecological Modelling 2025, 502, 111018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menchén, A.; Espín, Y.; Valiente, N.; Toledo, B.; Álvarez-Ortí, M.; Gómez-Alday, J.J. Distribution of Endocrine Disruptor Chemicals and Bacteria in Saline Pétrola Lake (Albacete, SE Spain) Protected Area Is Strongly Linked to Land Use. Applied Sciences 2020, 10, 4017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, J.; Luo, X.; Li, C.; Zhang, L. Urban Lake Spatial Openness and Relationship with Neighboring Land Prices: Exploratory Geovisual Analytics for Essential Policy Insights. Land Use Policy 2020, 92, 104479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Qu, M.; Hu, Y.; Liu, X.; Mei, Y. Differences in Microbial Communities and Phosphorus Cycles between Rural and Urban Lakes: Based on Glyphosate and AMPA Effects. Journal of Environmental Management 2025, 376, 124577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, J.; Parashar, D.D.; Kumar, D.R. Review of Planning Guidelines for Urban Lakes In India. Journal of Positive School Psychology 2023, 555–562. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Q.; Ren, L.; Yang, C. Regulation of Water Bodies to Urban Thermal Environment: Evidence from Wuhan, China. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBGE Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics) Cidades. Available online: https://cidades.ibge.gov.br/brasil/pa/belem/panorama (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Hossu, C.A.; Iojă, I.-C.; Onose, D.A.; Niță, M.R.; Popa, A.-M.; Talabă, O.; Inostroza, L. Ecosystem Services Appreciation of Urban Lakes in Romania. Synergies and Trade-Offs between Multiple Users. Ecosystem Services 2019, 37, 100937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, G.; Yang, Z.; Liang, C.; Yang, X.; Zhang, S. Urban Lake Scenic Protected Area Zoning Based on Ecological Sensitivity Analysis and Remote Sensing: A Case Study of Chaohu Lake Basin, China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, M.; Singhal, A.; Srinivas, R. Effect of Urbanization on the Urban Lake Water Quality by Using Water Quality Index (WQI). Materials Today: Proceedings 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, A.L.C.; Tavares, P.A.; Santos, Y.R.; Brabo, L.D.M.; Ribeiro, H.M.C.; Beltrão, N.E.S. Diagnóstico ambiental dos impactos da proliferação de vegetação macrófita no lago Bolonha na cidade de Belém-PA. In Proceedings of the Blucher Engineering Proceedings; Editora Blucher: Belo Horizonte, Brasil, July, 2017; pp. 473–481. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, G. M. T. S. De., Oliveira, E. S. De., Santos, M. De L. S., Melo, N. F. A. C. De., & Krag, M. N... Concentrações de metais pesados nos sedimentos do lago Água Preta (Pará, Brasil). Engenharia Sanitaria E Ambiental 2018, 23, 599–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, D.C.C. de; Rodrigues, R.S.S.; Filho, D.F.F. Surface runoff from drainage area of the lakes Bolonha and Black Water in Belém and Ananindeua, Pará. Research, Society and Development 2020, 9, e38932373–e38932373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, C.; Zhan, Q.; Zhan, D.; Zhao, H.; Yang, C. Spatiotemporal Evolution of Lakes under Rapid Urbanization: A Case Study in Wuhan, China. Water 2021, 13, 1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Ma, Y.; Jin, X.; Jia, S.; Zhao, X.; Zhao, X.; Cai, Y.; Xu, J.; Wu, F.; Giesy, J.P. Land Use and River-Lake Connectivity: Biodiversity Determinants of Lake Ecosystems. Environmental Science and Ecotechnology 2024, 21, 100434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; van Leeuwen, C.H.A.; Van de Waal, D.B.; Bakker, E.S. Impacts of Sediment Resuspension on Phytoplankton Biomass Production and Trophic Transfer: Implications for Shallow Lake Restoration. Science of The Total Environment 2022, 808, 152156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; Chen, D.; Lu, J.; Liu, S.; Wu, J.; Gan, L.; Yang, X.; He, X.; He, H.; Yu, J.; et al. Restoring Turbid Eutrophic Shallow Lakes to a Clear-Water State by Combined Biomanipulation and Chemical Treatment: A 4-Hectare in-Situ Experiment in Subtropical China. Journal of environmental management 2025, 380, 125061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteith, J.L.; Unsworth, M.H. Micrometeorology. In Principles of Environmental Physics; Elsevier, 2013; pp. 289–320. ISBN 978-0-12-386910-4. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, L.; Li, T.; Przybysz, A.; Liu, H.; Zhang, B.; An, W.; Zhu, C. Effects of Urban Lakes and Neighbouring Green Spaces on Air Temperature and Humidity and Seasonal Variabilities. Sustainable Cities and Society 2023, 91, 104438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schirpke, U.; Tasser, E.; Ebner, M.; Tappeiner, U. What Can Geotagged Photographs Tell Us about Cultural Ecosystem Services of Lakes? Ecosystem Services 2021, 51, 101354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Cheng, Y. Urban Lake Health Assessment Based on the Synergistic Perspective of Water Environment and Social Service Functions. Global Challenges 2024, 8, 2400144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiefer, I.; Odermatt, D.; Anneville, O.; Wüest, A.; Bouffard, D. Application of Remote Sensing for the Optimization of In-Situ Sampling for Monitoring of Phytoplankton Abundance in a Large Lake. Science of The Total Environment 2015, 527–528, 493–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baracchini, T.; Chu, P.Y.; Šukys, J.; Lieberherr, G.; Wunderle, S.; Wüest, A.; Bouffard, D. Data Assimilation of in Situ and Satellite Remote Sensing Data to 3D Hydrodynamic Lake Models: A Case Study Using Delft3D-FLOW v4.03 and OpenDA v2.4. Geoscientific Model Development 2020, 13, 1267–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holanda, P. da S.; Blanco, C.J.C.; Cruz, D.O. de A.; Lopes, D.F.; Barp, A.R.B.; Secretan, Y. Hydrodynamic Modeling and Morphological Analysis of Lake Água Preta: One of the Water Sources of Belém-PA-Brazil. J. Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. & Eng. 2011, 33, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, M.L.S.; Saraiva, A.L.D.L.; Pereira, J.A.R.; Nogueira, P.F.R.D.S.M.; Silva, A.C.D. Hydrodynamic Modeling of a Reservoir Used to Supply Water to Belem (Lake Agua Preta, Para, Brazil). Acta Sci. Technol. 2015, 37, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.-C.; Liu, H.-M.; Yam, R.S.-W. A Three-Dimensional Coupled Hydrodynamic-Ecological Modeling to Assess the Planktonic Biomass in a Subalpine Lake. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pará. Secretaria de Estado de Meio Ambiente. Revisão do Plano de Manejo do Parque Estadual do Utinga. Belém, 2013.

- Thomaz, S.M. Fatores ecológicos associados à colonização e ao desenvolvimento de macrófitas aquáticas e desafios de manejo. Planta daninha 2002, 20, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, P.A. de; Blanco, C.J.C.; Mesquita, A.L.A.; Lopes, D.F.; Filho, M.D.C.F. Estimation of Suspended Sediment Concentration in Guamá River in the Amazon Region. Environ Monit Assess 2021, 193, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastos, T.X.; Pacheco, N.A.; Nechet, D. Aspectos Climáticos de Belém nos Últimos Cem Anos, 2002.

- SEGEP - Secretaria Municipal de Coordenação Geral do Planejamento e Gestão. ANUÁRIO ESTATÍSTICO DO MUNICÍPIO DE BELÉM, v. 16. 2012.

- Brasil, N.M. de Q.X.; Neto, A.B.B.; Paumgartten, A.É.A.; Silveira, J.M. de Q.X.; Silva, A.A. da Análise multitemporal da cobertura do solo do Parque Estadual do Utinga, Belém, Pará/ Multitemporal analysis of the soil coverage of the Utinga State Park, Belém, Pará. Brazilian Journal of Development 2021, 7, 36109–36118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herb, W.R.; Stefan, H.G. Temperature Stratification and Mixing Dynamics in a Shallow Lake With Submersed Macrophytes. Lake and Reservoir Management 2004, 20, 296–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, K.-R.; Ji, Z.-G. Application and Validation of Three-Dimensional Model in a Shallow Lake. Journal of Waterway, Port, Coastal, and Ocean Engineering 2005, 131, 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soulignac, F.; Vinçon-Leite, B.; Lemaire, B.J.; Scarati Martins, J.R.; Bonhomme, C.; Dubois, P.; Mezemate, Y.; Tchiguirinskaia, I.; Schertzer, D.; Tassin, B. Performance Assessment of a 3D Hydrodynamic Model Using High Temporal Resolution Measurements in a Shallow Urban Lake. Environ Model Assess 2017, 22, 309–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DELTARES. Delft3D-FLOW, User Manual. Delft, Deltares. 2024 ver. 4.05. 753 p.

- Baracchini, T.; Hummel, S.; Verlaan, M.; Cimatoribus, A.; Wüest, A.; Bouffard, D. An Automated Calibration Framework and Open Source Tools for 3D Lake Hydrodynamic Models. Environmental Modelling & Software 2020, 134, 104787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Ye, Q.; Wu, S.; Stive, M.J.F. Wind Effects on the Water Age in a Large Shallow Lake. Water 2020, 12, 1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, A.; Ismail, S.; Elmoustafa, A.; Khalaf, S. Evaluating Evaporation Rate from High Aswan Dam Reservoir Using RS and GIS Techniques. The Egyptian Journal of Remote Sensing and Space Science 2017, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesser, G.R.; van Kester, J.; Walstra, D.J.R.; Roelvink, J.A. Three-Dimensional Morphological Modelling in Delft3D-FLOW. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, B., Haider, M.R., Yunus, A. A Study on Hydrodynamic and Morphological Behavior of Padma River Using Delft3d Model. proceedings of the 3rd international conference on civil engineering for sustainable development, KUET, Khulna, Bangladesh; 2016; p. 12. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, R.; Pereira, L.; Raes, D.; Smith, M. Crop Evapotranspiration Guidelines for Computing Crop Requirements. FAO Irrig. Drain. Report Modeling and Application. J. Hydrol. 1998, 285, 19–40. [Google Scholar]

- Lick, W. Numerical modeling of lake currents. Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences 1976, 4, 49–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resio, D.; Vincent, C. Estimation of Winds over the Great Lakes. J. Waterway Harbour. Coast. Eng. Div. ASCE 1977, 102, 263–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Zhang, C.; Brett, M.T.; Nielsen, J.M. The Importance of the Wind-Drag Coefficient Parameterization for Hydrodynamic Modeling of a Large Shallow Lake. Ecological Informatics 2020, 59, 101106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcement, G.J.; Schneider, V.R. Guide for Selecting Manning’s Roughness Coefficients for Natural Channels and Flood Plains; U.S. G.P.O. ; For sale by the Books and Open-File Reports Section, U.S. Geological Survey. 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, J.V.; Tadayon, S. Selection of Manning’s Roughness Coefficient for Natural and Constructed Vegetated and Non-Vegetated Channels, and Vegetation Maintenance Plan Guidelines for Vegetated Channels in Central Arizona. Scientific Investigations Report 2006. [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Strokal, M.; Burek, P.; Kroeze, C.; Ma, L.; Janssen, A.B.G. Excess Nutrient Loads to Lake Taihu: Opportunities for Nutrient Reduction. Science of The Total Environment 2019, 664, 865–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasca-Ortiz, T.; Pantoja, D.A.; Filonov, A.; Domínguez-Mota, F.; Alcocer, J. Numerical and Observational Analysis of the Hydro-Dynamical Variability in a Small Lake: The Case of Lake Zirahuén, México. Water 2020, 12, 1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, H.; Badr, H.M. Validation of Numerical Models of the Unsteady Flow in Lakes. Applied Mathematical Modelling 1979, 3, 416–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napiorkowski, J.J.; Piotrowski, A.P.; Osuch, M.; Zhu, S.; Karamuz, E. How the Choice of Model Calibration Procedure Affects Projections of Lake Surface Water Temperatures for Future Climatic Conditions. Journal of Hydrology 2025, 133236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tundisi, J. G.; Tundisi, T. M. Limnologia. São Paulo: Oficina de Textos, 2008.

- Torma, P.; Wu, C.H. Temperature and Circulation Dynamics in a Small and Shallow Lake: Effects of Weak Stratification and Littoral Submerged Macrophytes. Water 2019, 11, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wüest, A.; Lorke, A. SMALL-SCALEHYDRODYNAMICS INLAKES. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 2003, 35, 373–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sodré S dos, V. Hidroquímica dos lagos Bolonha e Água Preta mananciais de Belém-PA. Belém: UFPA. Dissertation in Portuguese, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Aviz, M.D. de, Souza, A.J.N. de, Coelho, A.O., Farias, F.F. de, Mendes, J.O.O., Oliveira, T.D.T.S. de, Pereira, J.A.R., Santos, M. de L.S. Sensoriamento remoto como ferramenta da estimativa do estado trófico de lago urbano na Amazônia (Belém, PA). Revista Ibero-Americana de Ciências Ambientais 2022, 13, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, M.C. Investigação do registro histórico da composição isotópica do chumbo e da concentração de metais pesados em testemunhos de sedimentos no Lago Água Preta, região metropolitana de Belém-Pará. Dissertation in Portuguese (Mestrado em Geoquímica e Petrologia) - Centro de Geociências, Universidade Federal do Pará, Belém, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Scheffer, M.; Hosper, S.H.; Meijer, M.-L.; Moss, B.; Jeppesen, E. Alternative Equilibria in Shallow Lakes. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 1993, 8, 275–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilt, S.; Brothers, S.; Jeppesen, E.; Veraart, A.J.; Kosten, S. Translating Regime Shifts in Shallow Lakes into Changes in Ecosystem Functions and Services. BioScience 2017, 67, 928–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Months/year | Discharge(m³/s) | Months/year | Discharge(m³/s) |

| nov/23 | 20 | may/24 | 16 |

| dec/23 | 19 | jun/24 | 18 |

| jan/24 | 16 | jul/24 | 19 |

| feb/24 | 14 | aug/24 | 20 |

| mar/24 | 14 | sep/24 | 20 |

| apr/24 | 14 | oct/24 | 19 |

| Region | Manning Roughness value |

| Region dominated by macrophytes | 0.030 |

| Sandy sediment predominance region | 0.025 |

| Sandy-silty sediment region | 0.018 |

| Silty sediment region | 0.016 |

| R | RMSE (ºC) | R² | MAE (ºC) | |||||||||||||

| Pts | Dec | Feb | Jun | Aug | Dec | Feb | Jun | Aug | Dec | Feb | Jun | Aug | Dec | Feb | Jun | Aug |

| A01* | -0.05* | 0.85 | 0.82 | 0.96 | 0.78 | 0.78 | 0.87 | 0.34 | 0.00 | 0.72 | 0.68 | 0.91 | 0.98 | 1.31 | 1.16 | 0.39 |

| A02 | 0.95 | 0.85 | 0.94 | 0.83 | 0.80 | 0.26 | 0.42 | 0.26 | 0.91 | 0.74 | 0.89 | 0.69 | 0.91 | 0.43 | 0.64 | 0.28 |

| A03 | -0.29 | 0.86 | 0.99 | 0.96 | 0.24 | 0.41 | 0.57 | 0.37 | 0.08 | 0.73 | 0.99 | 0.91 | 0.27 | 0.70 | 0.75 | 0.50 |

| A04 | 0.91 | 0.79 | 0.41 | 0.36 | 0.25 | 0.39 | 0.69 | 0.41 | 0.83 | 0.63 | 0.17 | 0.13 | 0.33 | 0.51 | 1.19 | 0.45 |

| A05 | 0.98 | 0.86 | 0.97 | 0.47 | 0.24 | 0.46 | 0.43 | 0.25 | 0.96 | 0.74 | 0.94 | 0.22 | 0.29 | 0.49 | 0.69 | 0.35 |

| A06 | 0.92 | 0.86 | 0.86 | 0.69 | 0.40 | 0.41 | 0.62 | 0.51 | 0.84 | 0.74 | 0.74 | 0.48 | 0.56 | 0.46 | 0.97 | 0.63 |

| A07 | 0.90 | 0.91 | 0.84 | 0.89 | 0.38 | 0.60 | 0.50 | 0.55 | 0.82 | 0.82 | 0.70 | 0.80 | 0.47 | 0.72 | 0.97 | 0.91 |

| A08 | 0.95 | 0.96 | 0.86 | 0.91 | 0.55 | 0.66 | 0.39 | 0.47 | 0.90 | 0.91 | 0.74 | 0.83 | 0.65 | 0.71 | 0.69 | 0.62 |

| A09* | 0.73 | 0.69 | 0.97 | -0.30* | 0.52 | 0.75 | 0.19 | 0.32 | 0.53 | 0.48 | 0.93 | 0.09 | 0.56 | 0.91 | 0.30 | 0.41 |

| A10 | 0.97 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 0.93 | 0.37 | 0.63 | 0.59 | 0.46 | 0.93 | 0.97 | 0.99 | 0.86 | 0.48 | 0.68 | 0.82 | 0.75 |

| A11* | 0.95 | 0.31 | -0.65* | 0.94 | 0.50 | 0.52 | 0.08 | 0.56 | 0.90 | 0.10 | 0.42 | 0.89 | 0.62 | 0.68 | 0.12 | 0.72 |

| A12 | 0.94 | 0.99 | 0.94 | 0.86 | 0.25 | 0.81 | 0.26 | 0.18 | 0.87 | 0.98 | 0.88 | 0.73 | 0.38 | 0.87 | 0.43 | 0.24 |

| A13 | 0.94 | 0.95 | 0.91 | 0.98 | 0.35 | 0.67 | 0.40 | 0.14 | 0.88 | 0.90 | 0.82 | 0.95 | 0.72 | 0.75 | 0.60 | 0.24 |

| A14 | 0.84 | 0.88 | 0.80 | 0.98 | 0.21 | 0.50 | 0.30 | 0.48 | 0.70 | 0.77 | 0.63 | 0.97 | 0.34 | 0.71 | 0.56 | 0.72 |

| A15 | 0.98 | 0.87 | 0.92 | 0.67 | 0.35 | 0.51 | 0.44 | 0.29 | 0.96 | 0.76 | 0.84 | 0.45 | 0.64 | 0.61 | 0.65 | 0.50 |

| A16 | 0.87 | 0.88 | 0.88 | 0.90 | 0.43 | 0.57 | 0.49 | 0.31 | 0.75 | 0.78 | 0.77 | 0.82 | 0.68 | 0.94 | 0.73 | 0.53 |

| A17* | 0.99 | 0.92 | -0.19* | 0.95 | 0.18 | 0.10 | 0.87 | 0.56 | 0.97 | 0.85 | 0.04 | 0.90 | 0.33 | 0.18 | 2.04 | 0.83 |

| A18 | 0.96 | 0.55 | 0.89 | 0.89 | 0.56 | 0.77 | 0.44 | 0.20 | 0.93 | 0.30 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.96 | 1.40 | 0.63 | 0.41 |

| A19 | 0.56 | 0.65 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.74 | 0.62 | 0.53 | 0.93 | 0.32 | 0.42 | 0.97 | 0.96 | 1.07 | 1.16 | 0.60 | 1.34 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).