1. Introduction

Virtual memory is a technique in memory management that allows a computer to use more memory than is physically available by temporarily transferring data from Random Access Memory (RAM) to disk storage. This is essential for running large programs or multiple applications simultaneously without running out of physical memory [

1]. Virtual memory allows processes to use more memory than is physically available by swapping data between physical memory and secondary storage. This is a key mechanism in systems with virtual memory, where memory is divided into pages and the operating system dynamically manages their placement between RAM and disk [

2,

3]. However, this can lead to page faults. It happens when a process tries to access a virtual memory address for which there's currently no valid mapping in physical RAM and this is called "minor fault".

Page faults can also be the result of poor code locality. Poor code locality directly affects the frequency of page faults because it determines how often and in what order the program accesses memory pages [

4,

5,

6]. Poor code locality causes the program to switch between pages frequently and can lead to thrashing (the system spends more time paging than executing code). The problem is how to relocate blocks (or program segments) across pages of virtual memory to minimize page faults [

7,

8]. Program code transformations, such as program restructuring [

9,

10,

11] and refactoring [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16], as well as various forms of code reorganization, have a positive impact on page faults, particularly in terms of locality. The absence of a definitive solution to this problem has sustained ongoing interest and research in both past and present studies.

Many formulations of page faults or program optimization problems lead to complex combinatorial challenges, making it necessary in practice to rely on approximate or heuristic approaches. Most existing research in this area is based on clustering techniques [

17,

18]. While these techniques have shown improvements in experimental settings, they provide only approximate solutions with unknown accuracy, i.e., the cluster approach does not estimate how the solutions are obtained far or close to unknown exact (optimal) solutions [

19,

20]. The Working Set strategy, proposed by P.Denning [

21], aims to prevent thrashing (excessive swapping that slows down the system) by ensuring that the pages a process needs are resident in memory. This strategy is particularly relevant for optimizing performance in systems with limited RAM, as it balances the degree of multiprogramming (running multiple processes) and CPU utilization. In [

22] proposed page replacement policy monitors the current working-set size and controls the deferring level of dirty pages, preventing excessive preservation that could lead to increased page faults, thus optimizing performance while minimizing write traffic to PCM. In [

23] authors modified the ballooning mechanism to enable memory allocation at huge page granularity. Next, they developed and implemented a huge page working set estimation mechanism capable of precisely assessing a virtual machine’s memory requirements in huge page-based environments. Integrating these two mechanisms, they employed a dynamic programming algorithm to attain dynamic memory balancing. Also, in [

24,

25,

26] discussed working set size (WSS) estimation to predict memory demand in virtual machines, which helps optimize memory management. By accurately estimating WSS, the strategy minimizes page faults by ensuring sufficient memory allocation to meet actual usage needs. The working set strategy solves the problem of page faults by preventing actively used pages from being freed, even if the code is suboptimal. However, poor locality increases the size of the working set and makes it too large to fit in RAM, which can negate the benefits of the strategy. We propose an approach to optimize the working set size by using combinatorial space, in the form of Hasse diagram. This problem is classified as

NP-hard, meaning that finding the optimal solution is computationally hard for large instances, as it would require checking an exponentially large number of possibilities. Thus, the research has also a fundamental aspect [

27,

28,

29,

30,

31] that has encouraged us in our research efforts.

In this paper, we focus on the problem of page faults minimization for virtual memory systems. Motivated by the need to achieve either an optimal or near-optimal solution, our goal is to construct an approach based on identifing functional and corresponding constraints using the working set swapping strategy to minimize page faults. We use the geometric interpretation of the computational process because it offers a visual and analytical tool for solving a problem that is typically approached through algorithmic or heuristic methods. This approach could potentially reveal patterns or properties not evident in purely computational models.

2. Methods

In computing systems with page-based organization of the virtual memory, programs generate a sequence of references (accesses) to their pages during execution, which we will call as “control state”. At any moment of program execution, the physical memory (RAM) does not contain all pages of the program, but only a part of them (the resident set).

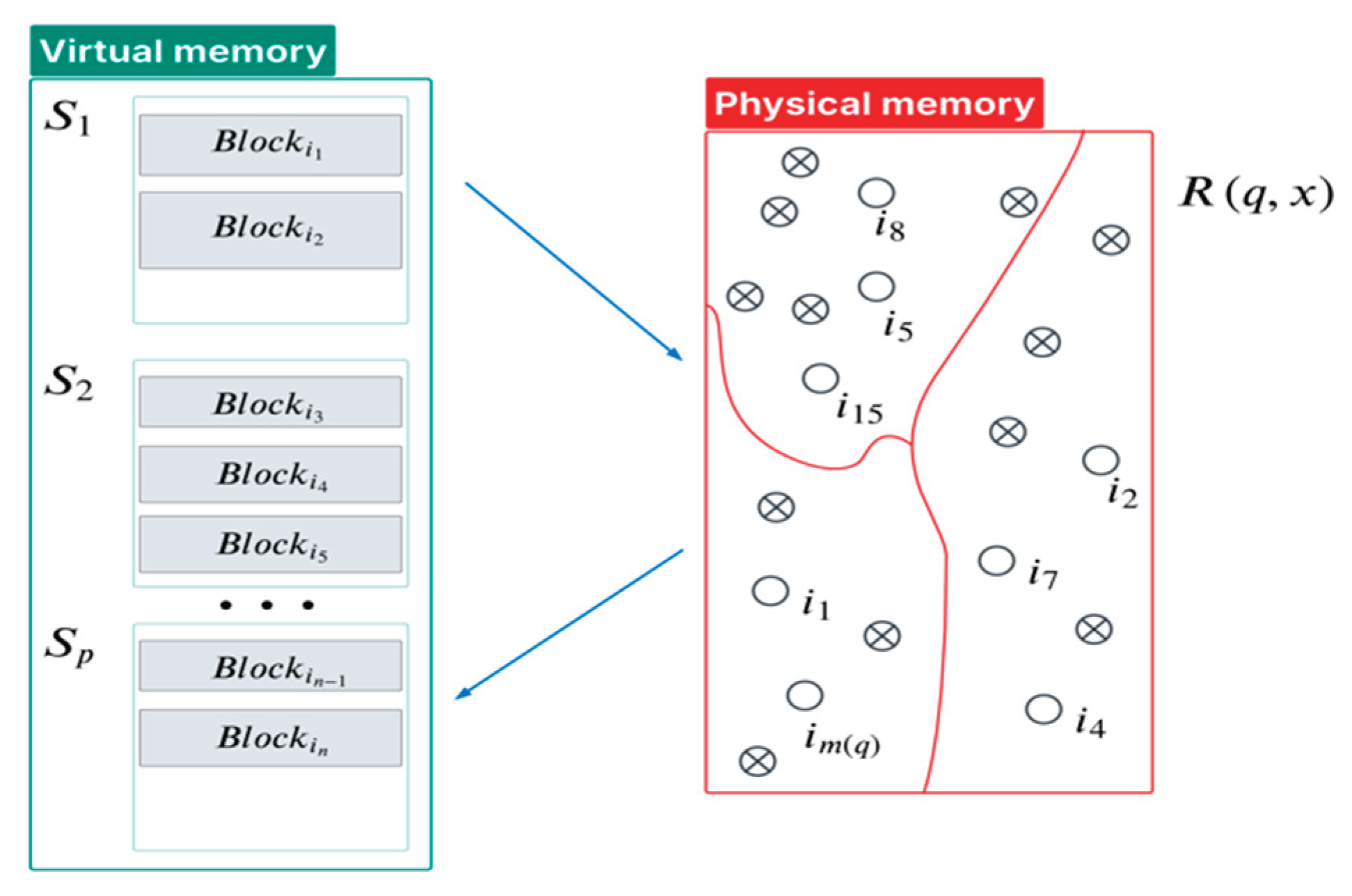

Figure 1 shows an example of virtual and physical memory. Virtual memory contains blocks of different sizes divided into pages. The physical memory contains copies of the virtual memory pages and here the blocks are restructured. The size of the physical memory at any moment of the computational process is much smaller than the size of the virtual memory. Let the program code with poor locality that requires segmentation consist of

blocks with numbers

which are singled out in advance and scattered over

pages

of a virtual memory.

The code execution causes a problem because of generating a redundant number of page faults, which can be greatly affected by the reason of poorly structured program code and that reduces performances both of the program code and a system itself. Let

be a length of

r-th page,

and

be a length of block

,

Thus the system supports multidimensional size of pages [

32]. As blocks we mean a part of the code such as subroutines, linear segments of a code, separate interacting programs, data blocks and etc. Distribution of blocks

over pages

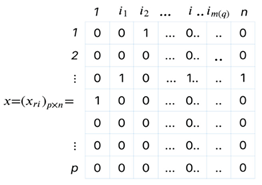

is assigned, for example via Boolean matrix

, where an element

, if the block with number

belongs to the page with number

and

, otherwise. All of such kind matrices we denote via

.

In our case, working set

is generated by control state

and matrix

As corresponding denotation for control state, we will use

. The control state

of the program at moment

, it is a sequence of program references to their pages for the last

moments before moment

.

Figure 1 indicated that control state

is

where

is block number

, which belongs to

and any of them marked as 〇. Another one symbol

in

Figure 1 means blocks (or its numbers) which does not belong to

but belong to corresponding page of working set

and present in the physical memory. In other words, all elements 〇 are blocks that are often referenced and they form the working set, other elements

are also blocks that do not form the working set, but they can be present in physical memory at any moment of the computational process. For the matrix

, there are constraints (a)-(c) [

33], which are described below:

Functional: As a functional of the main problem, we will take a mathematical expectation of number of page faults for one run of the program code. As a functional of the auxiliary problem, we will take a mean value of page faults for runs of the program code.

Constraint (a): Total length of the blocks belong to any page does not exceed the length of this page.

Constraint (b): Any block of the program code belongs only one page of the program code.

Constraint (c): Total length of any working set generated while execution of the program code does not exceed some system constant that known in advance.

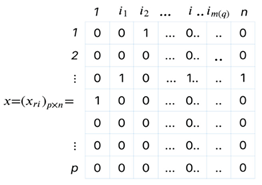

Constraints (a)-(c) have to be assigned by a matrix which defines distribution of the blocks over pages An important role for our consideration plays a Boolean matrix which determines the structure of a program, i.e., distribution blocks of a program over pages For it has to hold constraints (a)-(c), and all of such kind of matrices form the set . Next, we present an example of the structure of matrix with control state singled out among columns of matrix . The matrix helps to calculate the function :

|

2.1. Geometric Interpretation of the Computational Process

We consider the geometric interpretation of the computational process using the Hasse diagram, a graphical representation of a partially ordered set [

34]. Each element of the set is represented by a node. A line (edge) exists between each pair of nodes

and

such that

and there is no d such that

, i.e., we say that

covers

[

35]. In combinatorial space the control state

may happen at latter moments when our program unexpectedly offloads from the physical memory and after a while the program activates as if it runs from the start (cold start). Another way to start is a warm start when the system is trying to continue the computing process from level 1 or 2. Further, we propose that any such event should restore as a warm start (restart) and treat it as one additional page fault, which we will take into account in additional expressions (1), (2) for functionals of main and auxiliary problems.

Let the set of control state

be denoted as

. When the set

is formed we have to find the subset of the

, which we denote as

and which will be useful for us under the constraint (

c). Any element

has the property, namely, in the

there is no element

such as

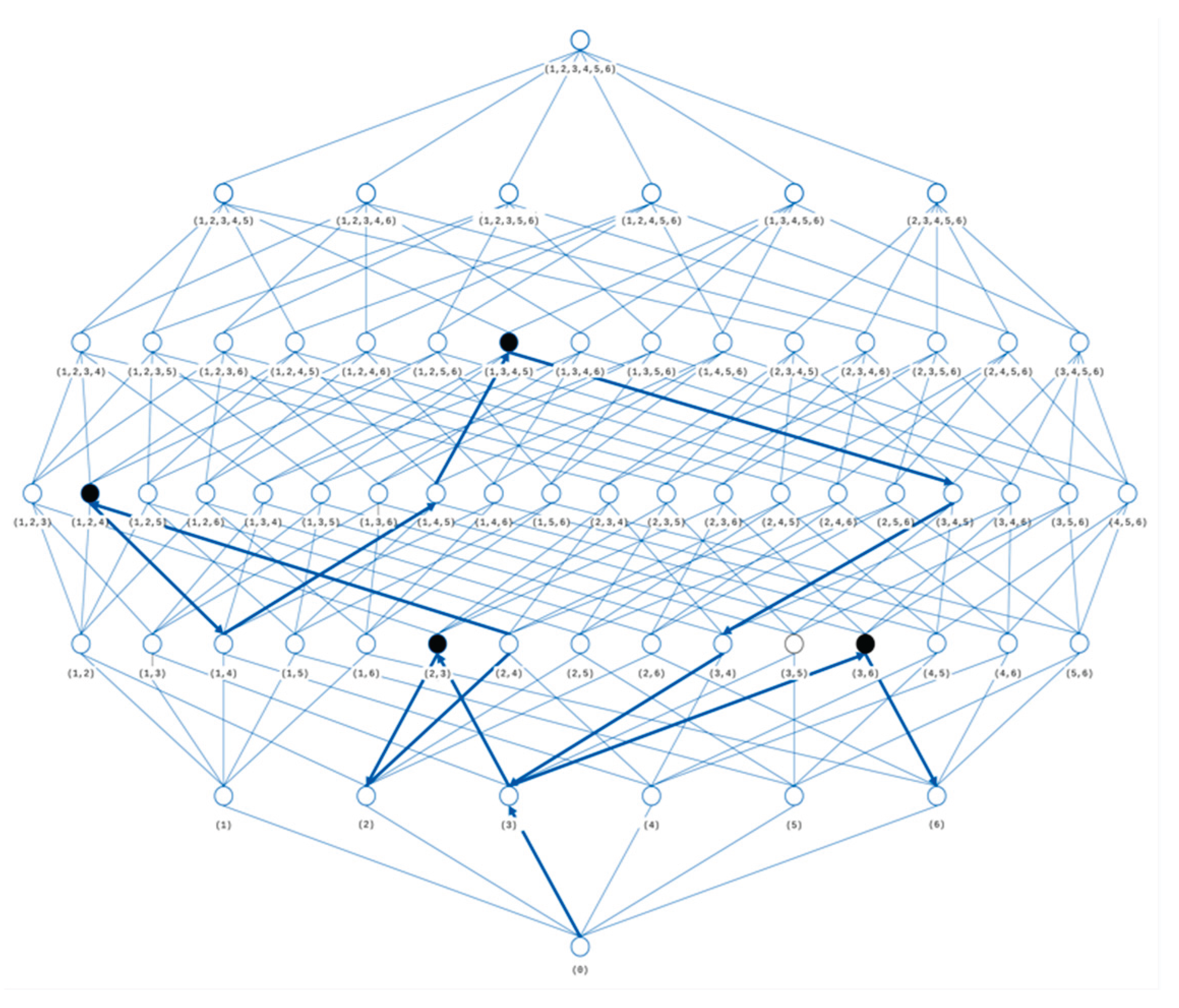

. Conceptually looking at the Hasse diagram, as shown in

Figure 2, the element

is a node which is a peak-node under any random walk path over nodes of the Hasse diagram. Following our approach for any sequence of control state already from

along the axis

with fixed

is a corresponding random walk path over nodes of the combinatorial space. Thus, the computational process is a random walk path through the nodes of the combinatorial space, for which we use the Hasse diagram.

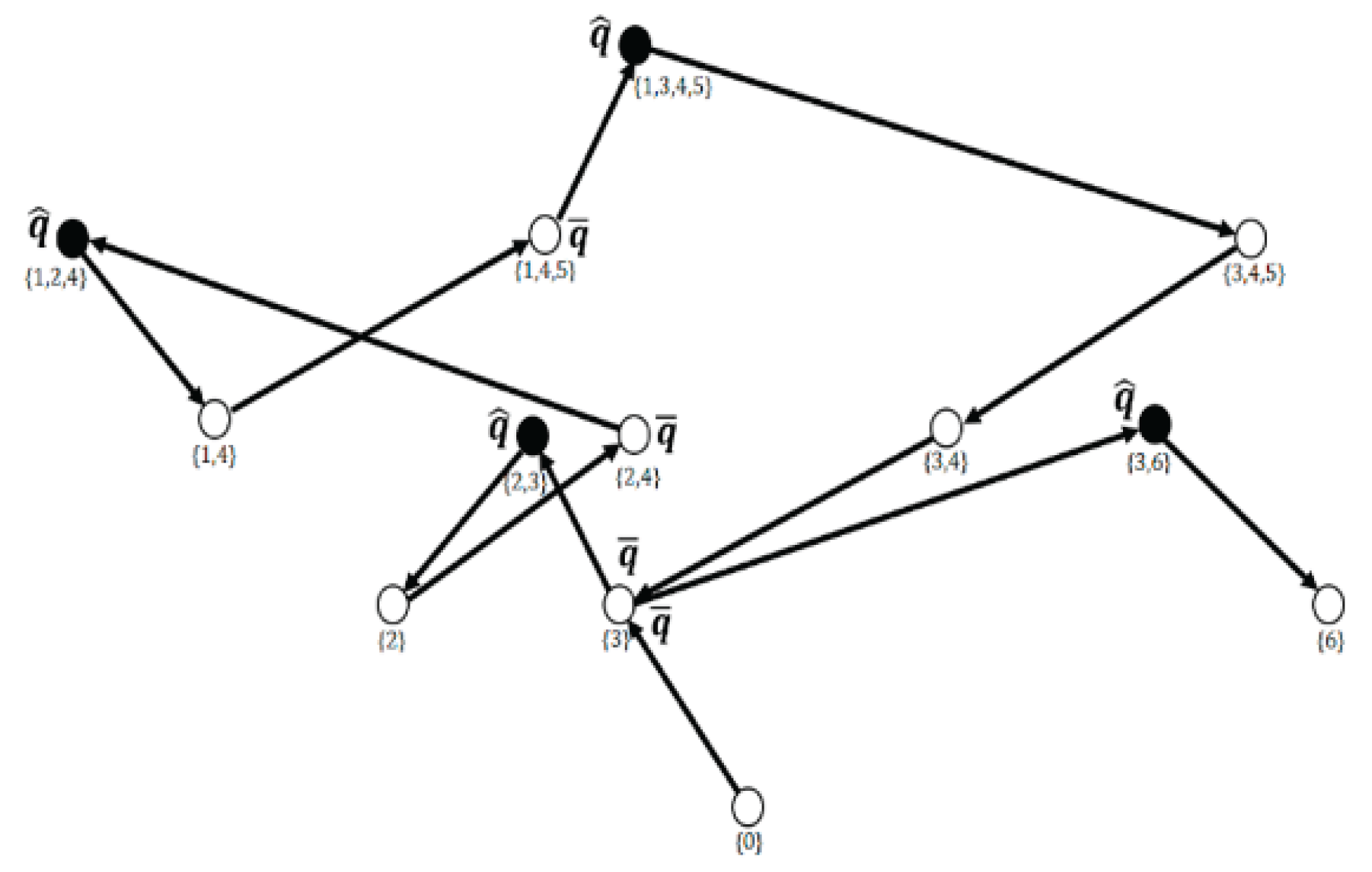

A Hasse diagram is a two poles combinatorial space with a number of blocks , and several levels. The down pole, located at the zero level corresponds to the empty set for starting any process. The upper pole corresponds to a number of blocks of the program code, i.e., . Elements of the set correspond to appropriate nodes of the combinatorial space. Any control state that corresponds to the intermediate node . For example, at level , is an ordered record, such that and connects with nodes of the level and with nodes of the level And, node of the level 2, connects with two nodes at level 1, namely, and and connects also with four nodes at level 3, namely, , , Among nodes of the singled out path, black nodes are: (2,3), (1,2.4), (1,3,4,5), (3,6) and are needed for us to optimize nodes , which are down nodes of the edges ( namely: (2,4), (1,4,5) (3).

Figure 3 indicates a dedicated random walk path along nodes under

, that correspond to a working set and singled out path with

and

nodes on it. Eventually, we have a random walk path over nodes with

and

. Under multiple runs nodes

and

can be changed but at all times they are existing in the computional process, including the final situation, when the set

is determined. The only point to note for description of an algorithm to determine

is very simple and consists of sequentially sorting out elements of the

and comparison to a current

First, it takes removal of the current element

from

If yes, i.e., then

has to be crossed out of consideration as the candidate for

. If no then we have to continue the check of an inclusion into the next

from

If we cannot find such

from

and the set

already is exhausted then

becomes

and we add

into

. We repeat the process with the next elements of

as

until the set

is exhausted and we form the set

It has to be noted that any run of the program takes finite time.

2.2. Functionals and Constraints for

In this subsection we describe functionals and constrains of the main and auxiliary problems. We will start by finding expressions of the functional of both the main and auxiliary problem and expressions for corresponding constrains for matrix

. As well, it is useful to determine the connection between the calculation that will be done and its geometric interpretation. Using information given above, we introduce a random variable

which is a number of references to block

under the execution of control state

for one run of the program. Let random variable

be the same as

but in

j-th run of the program

Let expected value of

and

be:

and a mean value:

Calculation of the

can be done in the following way:

In other words, the value

is corresponding to the absence of the page fault under event

, the value

if block

belongs to some page

from

Otherwise the value

is corresponding to the page fault. If block

then it has to be

for any

Next, we can remove the control state

from

, then a total number of page faults for one run of the program will be:

and for the functional of the main problem which has to be minimized we have:

It is worth noting that in the expression for

the any value

does not depend on matrix

and quite the opposite the function

depends on given

and

and

and does not depend on random event

and where it happens. For the functional

of the auxiliary problem holds:

It is interesting to note that value

from (2) can be assigned to the edge that connects the node

and the node

in the Hasse diagram, where the function

and otherwise. This edge has to be weighted as zero if the function

It may help to calculate the value of the functional

for fixed

It will be sufficient to determine whether the weight of any edge in question is 1 or 0, which means whether a page error has occurred or not. The system of constraints (a) - (c) setting the set of

of admissible solutions for both the main problem (1) and for auxiliary problem (2) registers in the form:

where in (5) the value

is length of page

. The system (3)-(6) contains

non-trivial correlations. Note that constraints (3)-(5) correspond to constraints (a)-(c) respectively. The function

, if page

and

, otherwise, i.e., the function

is the characteristic function of the

. Under given

and

it is easy to calculate

via elements of the matrix

, namely if

q= (

then:

2.3. Reduction in a Number of Inequalities of the Control State in Working Set

Constraint (5) contains |Q| inequalities and probably there are a lot. Here is an opportunity to reduce essentially a number of inequalities in (5). As already mentioned, from a practical point of view, we may propose that there exists a system constant, let it be

, which limits the dimension of any working set

and which is known in advance. It is necessary to note the set

and then we can substitute system (5) for:

but first we must put in (5) for all

,

Let

be the length of the working set

, and

To give a ground for substitution it is worth paying attention to

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 with black nodes on them corresponding to control state

and nodes

such as

. Then the next correlations hold: if

then

and

where

,

and if inequality (7) holds for some

then it also holds for any

which

. Here it is taken into account that any

belongs to at least one

from

as shown in

Figure 3, node (3). Evidently, the set

of admissible solutions is non empty since an initial distribution block

over pages

satisfies constraints (3)-(6).

3. Results

The nonlinear model of the reorganization of the program code which is constructed above, contains nonlinear functional (1) and/or (2) and both linear inequalities (3), (4) and nonlinear system of constraints in (5). The power of the set

in (7) is not too large in contrast with the power of

in (5). The constraints (5), (7) show instead of controlling a size of any

with totally

inequalities, after substitution (7) instead of (5) we have in (7) only

inequalities. As for functional (1) or (2) it can be reduced to a number of addends in (1) or (2) on the basis of the idea that if block

then

for any

and second sum in (1) or (2) has instead of

, only the indexes

, where the set

does not contain such

belongs to

Under given

and

and under the event

if

and

then there will be no page fault. If

and

then there will also be no page fault. It is important to note that some methods of discrete optimization, based on construction of valuation function, in our case, for the problem (2) on the basis of geometric interpretation of the computational process, it is the lower valuation function, which is written on the left side of (8):

From [

19,

36] it follows that, if it is possible to solve the problem with valuation function, which has been written also in (9)

then it gives the opportunity, with appropriate complexity, to get an exact (optimal) solution of the problem (2) with functional on the right side of (8). The set

on the left part of (8) is a subset of

, which is defined by a separate

and consists of a number of

. If we look to

Figure 3, a node

has to be connected with node

by the edge, i.e., (

which is the oriented edge with nodes

and

. Meanwhile it is not necessary to take into account both on the left side of (8) and (9) the edge (

, since the weight of the (

equals 0. On the left side of (8) for any

a node

is running for edge (

until the set

is exhausted. We include a node

into

if there is at least one reference, while

h runs of the program, from node

to the node

The number

on the left part of (8) is defined as

i.e.,

let it be a denotation

. The left part of (8) contains a lesser number of addends than the right side of (8). The same we may say about the functional of the problem (1), i.e., about

As for optimal solution of (1) it is interesting to point out conditions for initial data when the optimal solution of problem (2), let it be the matrix

, will be an

- optimal solution of the problem (1) in sense:

where the matrix

is an unknown optimal solution of the problem (1). Those conditions first of all imply, to determine common properties of the distribution laws for the variables

and lower bound for the number h of executions (runs) of the code, under which inequality (10) holds.

Under the known values

in (1) i.e., the distribution law of each random variable

is known, the algorithm of the solution, both the initial problem (1), and the problem (2) can be based on valuation function (see (8)) and the property of the function

:

which takes place for any

and represents a special case of the property of supermodularity. In the case of unknown values

(the distribution law of the random variables

is unknown) the situation for solution of problem (1) becomes more complicated. In this case the problem (2) could be used as an auxiliary problem for (1) and optimal solution of (2), i.e.,

can be taken as the solution of (1) in the sense of the inequality (10).

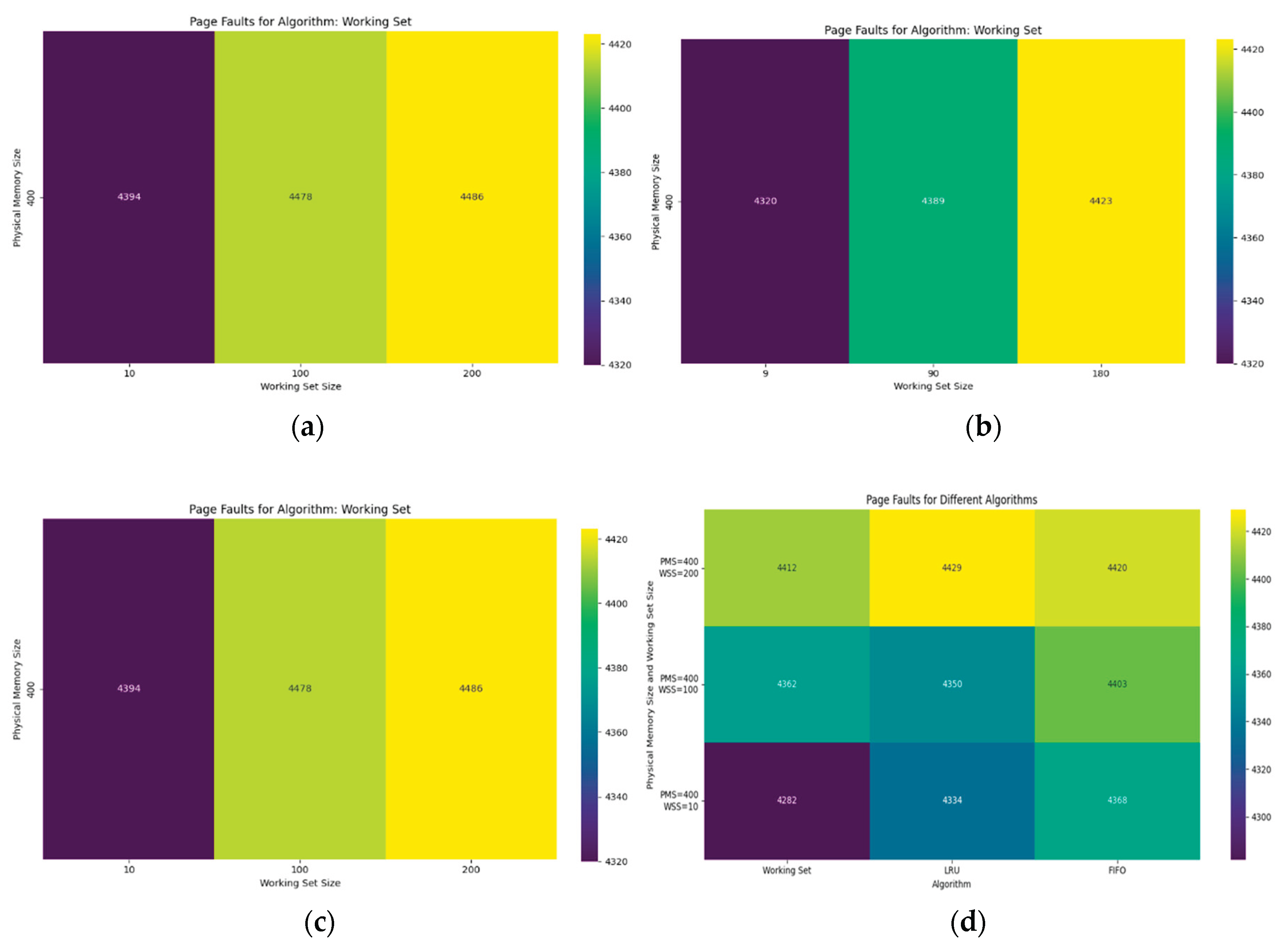

We used a heatmap technique to visualize page faults and different working set sizes as shown in

Figure 4(a), (b) and (c), where are shown the number of page faults with a different working set size and a fixed Physical Memory Size.

Figure 4(d) indicates a comparison result of page faults simulation in different algorithms like Working Set, LRU (Least Recently Used) and FIFO (First In, First Out). Experiments were performed with different parameters: Virtual Memory Size, Physical Memory Size, Working Set Size, Access Sequence Length, Locality Factor. The Working Set algorithm tries to keep only actively used pages in memory. If the working set size is smaller than the physical memory size, the number of page faults will be low, if working set size increases, then page faults also increase accordingly. The LRU algorithm unloads the page that has not been used for the longest time. It performs well, especially when there is locality in the order of accesses.

The FIFO algorithm unloads the page that was loaded first. It shows worse results compared to LRU and working set, especially in the presence of cyclic access patterns. The simulation results on page fault optimization show that in the fixed size of physical memory, there are fewer page faults for all algorithms. This is because more pages can be loaded simultaneously, reducing the need for paging. When the physical memory size is small, the number of faults increases because the algorithms are forced to offload pages more frequently. The heatmap shows that for a given algorithm and physical memory size, if the cell color is light, it indicates a large number of page faults. For example, a FIFO with a small physical memory size may have a high number of page faults. If the cell color is dark, it indicates a low number of page faults. For example, an LRU with a large physical memory size may have low page fault values.

Table 1 presents that Working Set is the most effective when there is locality in the order of accesses, especially when the physical memory size is large. LRU performs consistently well and is a compromise between implementation complexity and efficiency. This algorithm effectively minimizes the number of page faults. FIFO is the least efficient, especially when the physical memory size is small, because it does not consider locality and may discard pages that will be used soon.

We conducted two more experimental studies using a 10-node FPGA-based system arranged in a ring topology. These experiments extend the original analysis by comparing caching algorithms and exploring the impact of varying cache sizes, using a random memory access workload to simulate a worst-case scenario. We evaluated WS, LRU and FIFO caching algorithms with a cache size of 5% allocated from free memory. Each of the 10 nodes performed 100,000 operations, with 80% accessing local memory and 20% requesting remote data. Performance was assessed through average page fault time, page fault frequency, and total execution time.

Table 2 shows the results indicate that the WS algorithm consistently outperformed the alternatives. WS reduced the average page fault time to 6 µs and the fault frequency to 35%, yielding a total execution time of 13 seconds. LRU and FIFO showed similar performance, with average fault times of 7 µs and frequencies around 38%, resulting in execution times of 14.5 seconds. Random Replacement performed the worst, with a fault time of 8 µs, a frequency of 40%, and an execution time of 15 seconds.

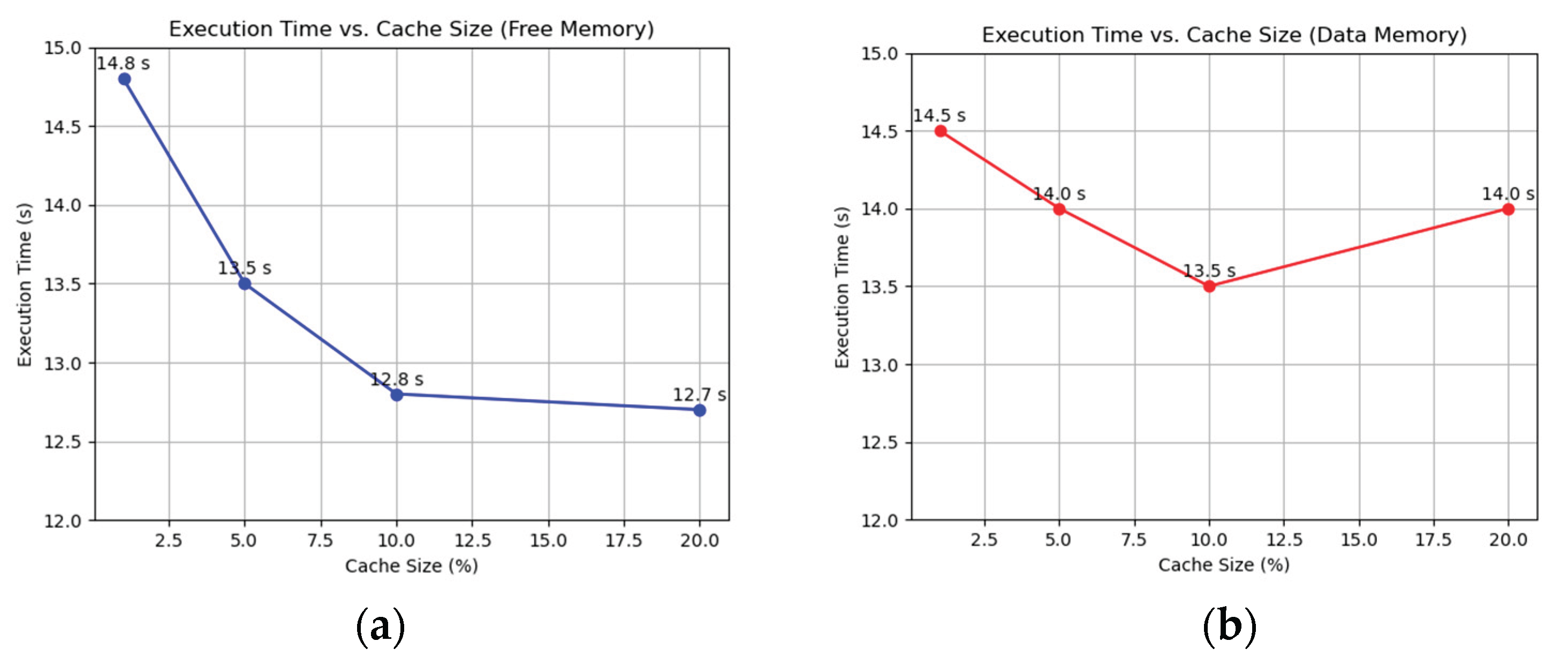

The superior performance of WS likely stems from its ability to maintain a set of actively used pages, adapting even to random access patterns. LRU and FIFO, while effective in workloads with locality, offer little advantage here, and RR’s lack of pattern consideration makes it the least efficient. We varied the cache size—1%, 5%, 10%, and 20% of total memory—using the Working Set algorithm, sourcing memory from both free reserves and data memory (overflow). The same workload and system configuration were applied. As cache size increased from 1% to 10%, page fault frequency dropped from 39% to 33%, and total execution time decreased from 14.8 seconds to 12.8 seconds as shown in

Figure 5a. Beyond 10%, at 20%, the frequency stabilized at 32%, and execution time plateaued at 12.7 seconds, indicating diminishing returns. Average page fault time remained steady at around 6 µs across all sizes. With data memory caching, fault frequency decreased from 38% at 1% to 30% at 10%, with execution time improving from 14.5 seconds to 13.5 seconds. However, at 20%, execution time rose to 14 seconds despite a frequency of 29%, as reduced data memory led to more frequent evictions and reloads as shown

Figure 5b.

These experiments reaffirm the efficacy of RAM page caching, with the Working Set algorithm proving optimal for random workloads. The choice of algorithm significantly impacts performance, with WS reducing execution time by up to 14% compared to no caching (15 seconds).

5. Conclusions

Poor code locality encourages the study of program restructuring and optimization strategies, such as the working set strategy, to minimize page faults in[ virtual memory systems. This paper proposes a combinatorial approach to optimize working set size, and aims at obtaining near optimal solutions using geometric interpretation and functional constraints. In order to optimize the calculations, a valuation function was found which includes the empirical average of the experiments and a system of constraints. Our proposed geometric interpretation of the computational process in the form of a Hasse diagram helps to reduce the dimensionality of the page faults minimization problem. The approach outlined in the paper provides a basis for finding the optimal solution to the main problem, i.e., to page faults minimization, if the minimum distribution of random variables is known in advance. Otherwise, with an unknown minimum of the random variable distribution, the constructed approach provides the basis for finding an accurate solution to the auxiliary problem, i.e., the experimental average of page faults.

Currently, the working set strategy is usually used as a theoretical research base, either for comparison or for auxiliary purposes, as it is considered expensive to implement. However, in our case, if the program code has a block structure, then the results obtained can be used to build a fast, accessible and affordable swap algorithm.