Submitted:

03 July 2025

Posted:

04 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods and Materials

2.1. Animals

2.2. Genotyping

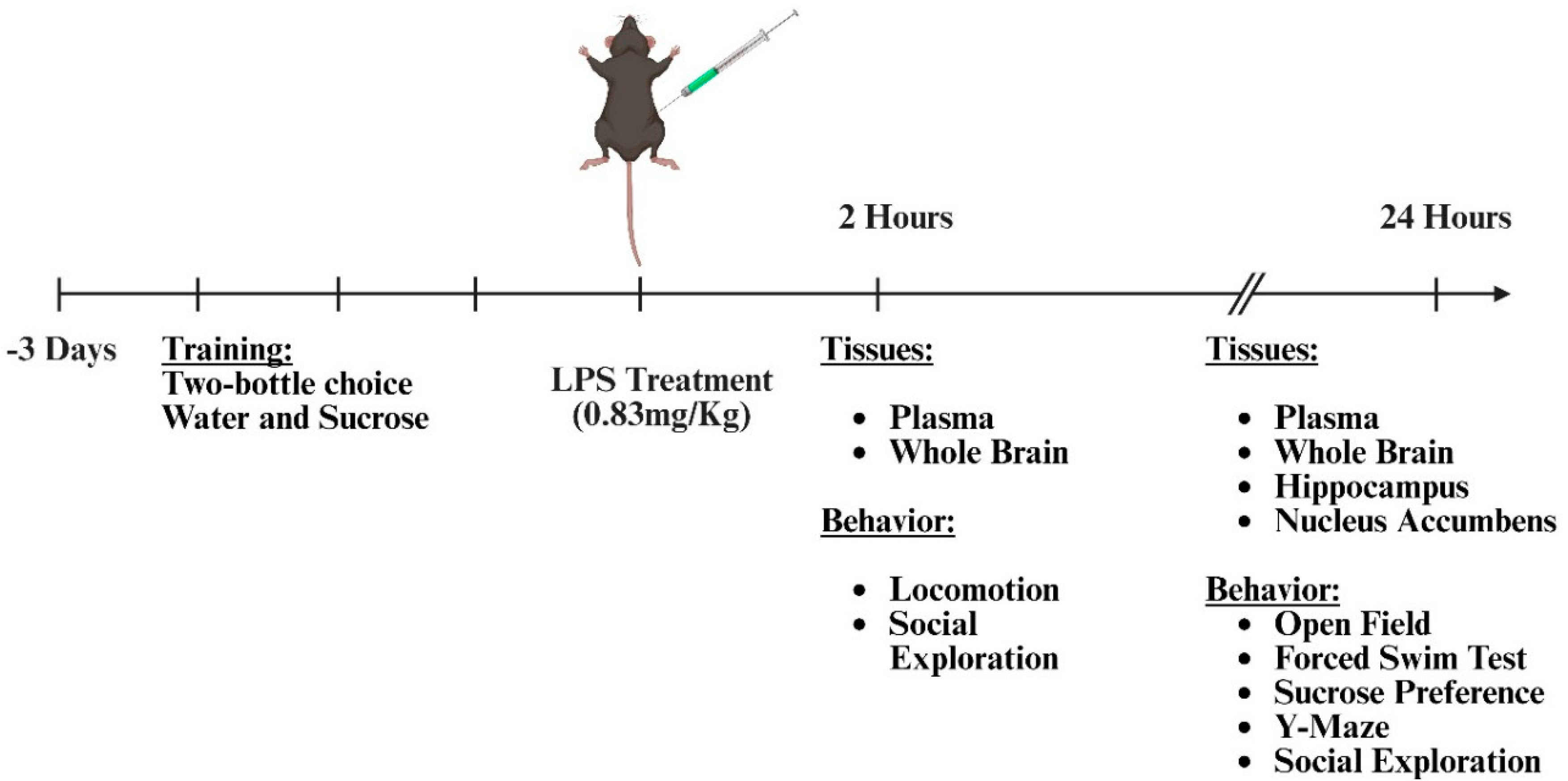

2.3. Experimental Timeline and Treatments

2.4. Behavior Testing

2.5. Tissue Preparation and RT-qPCR

2.6. Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

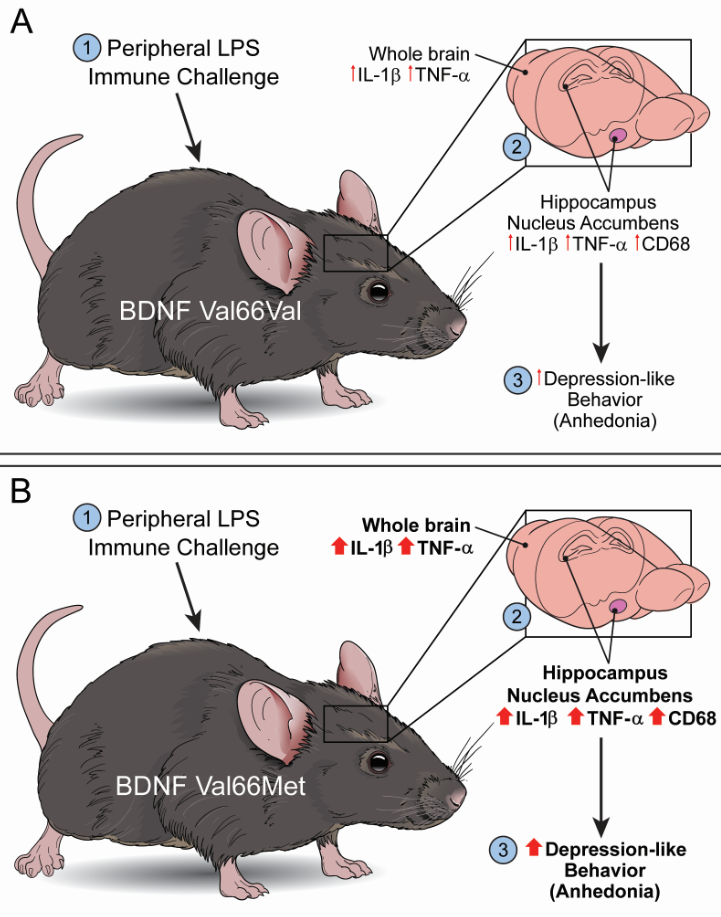

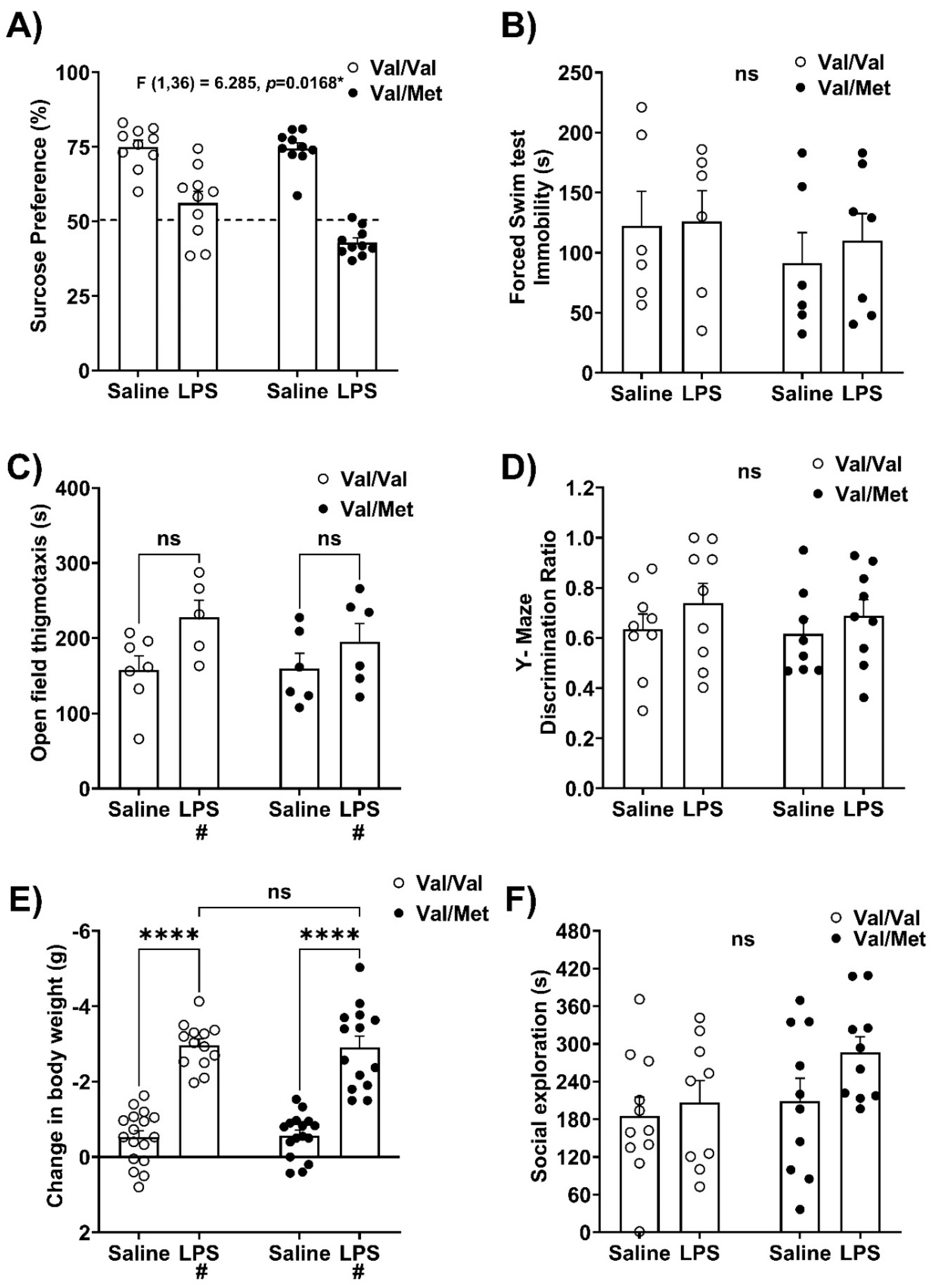

3.1. BDNF Val66Met Expression Results in Susceptibility to the Anhedonia-Like Behavioral Effects of Immune Challenge

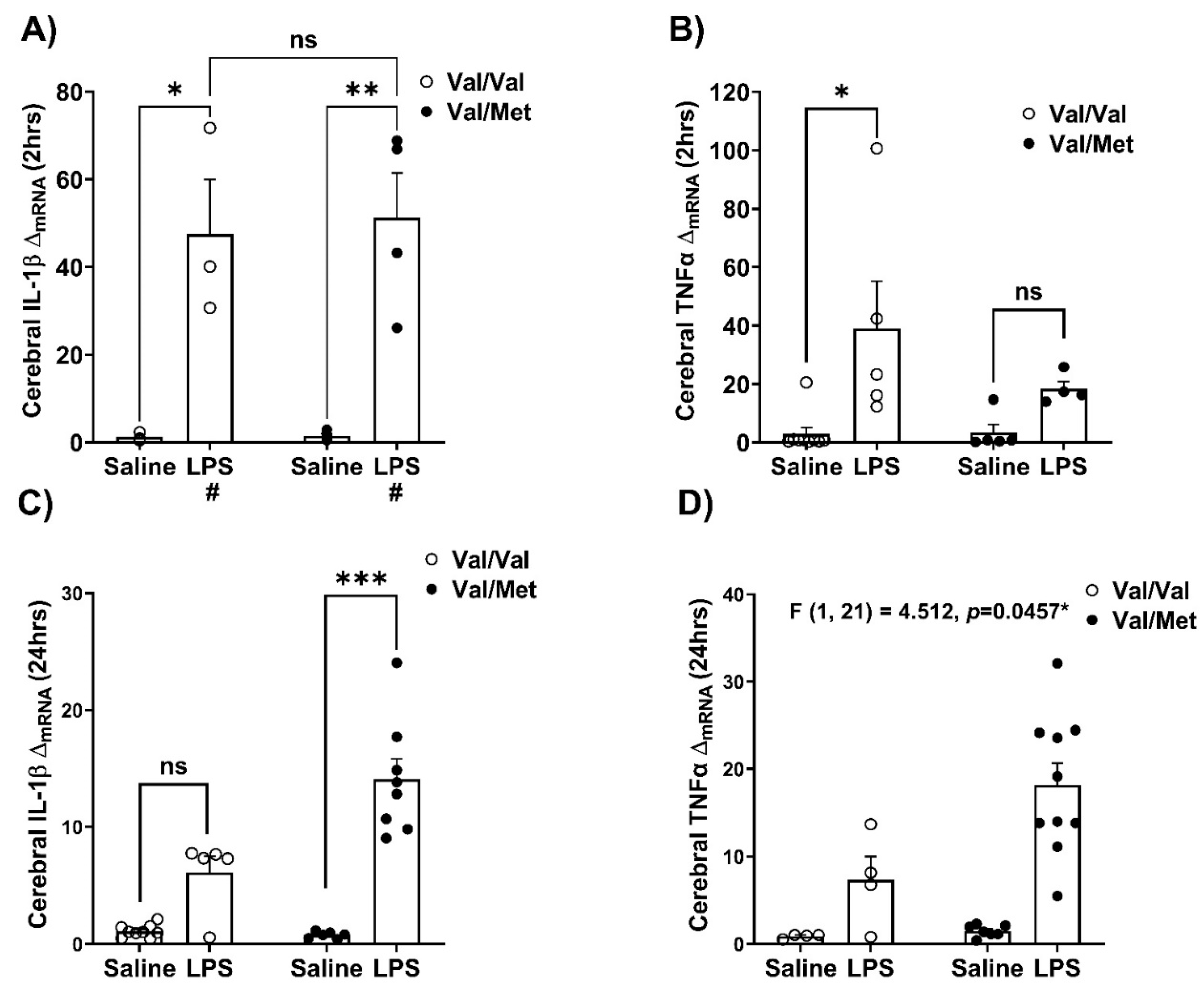

3.2. Immune Challenge Induces Dysregulated Whole Brain Pro-Inflammatory Cytokine Expression in BDNF Val66Met Mice

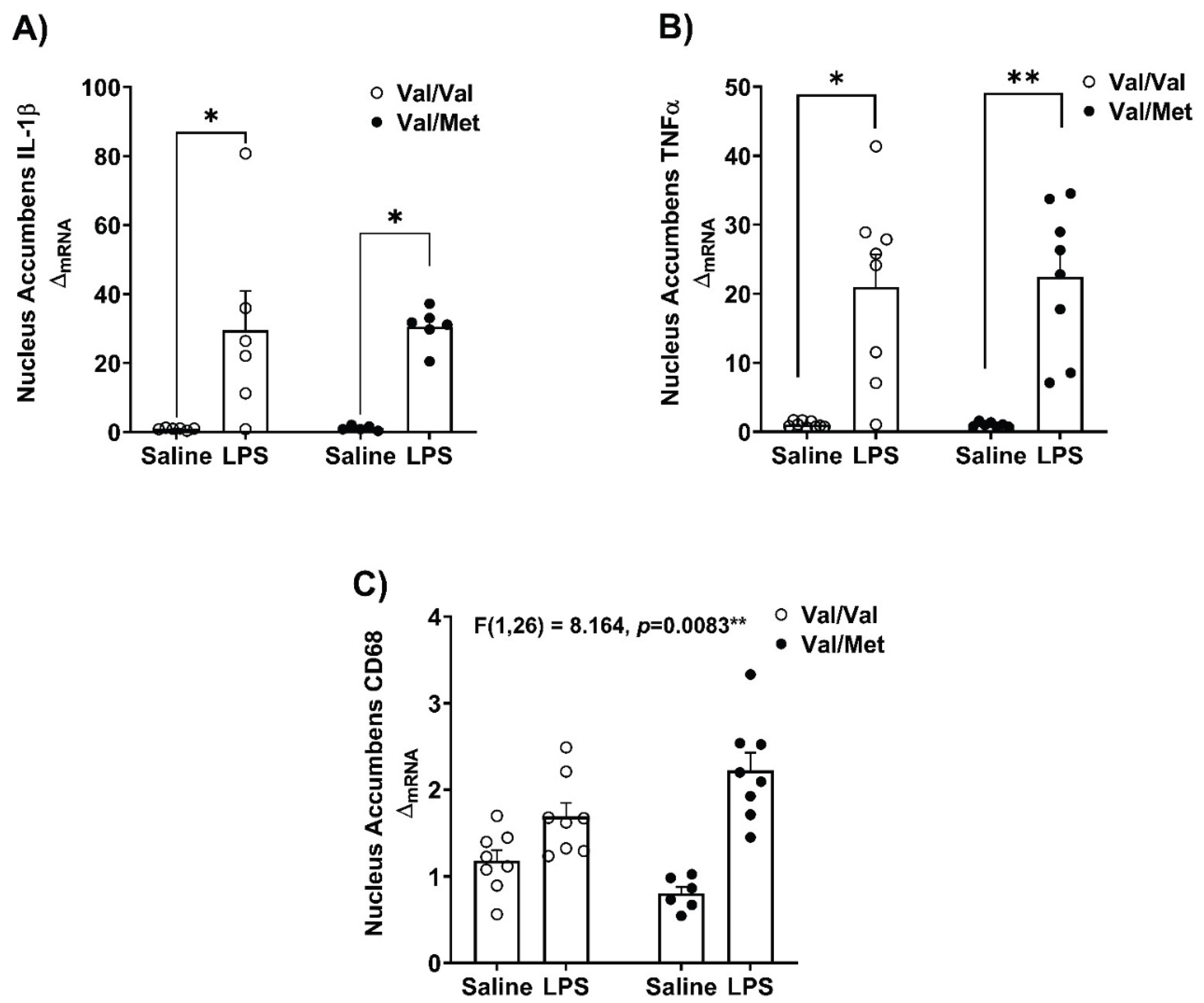

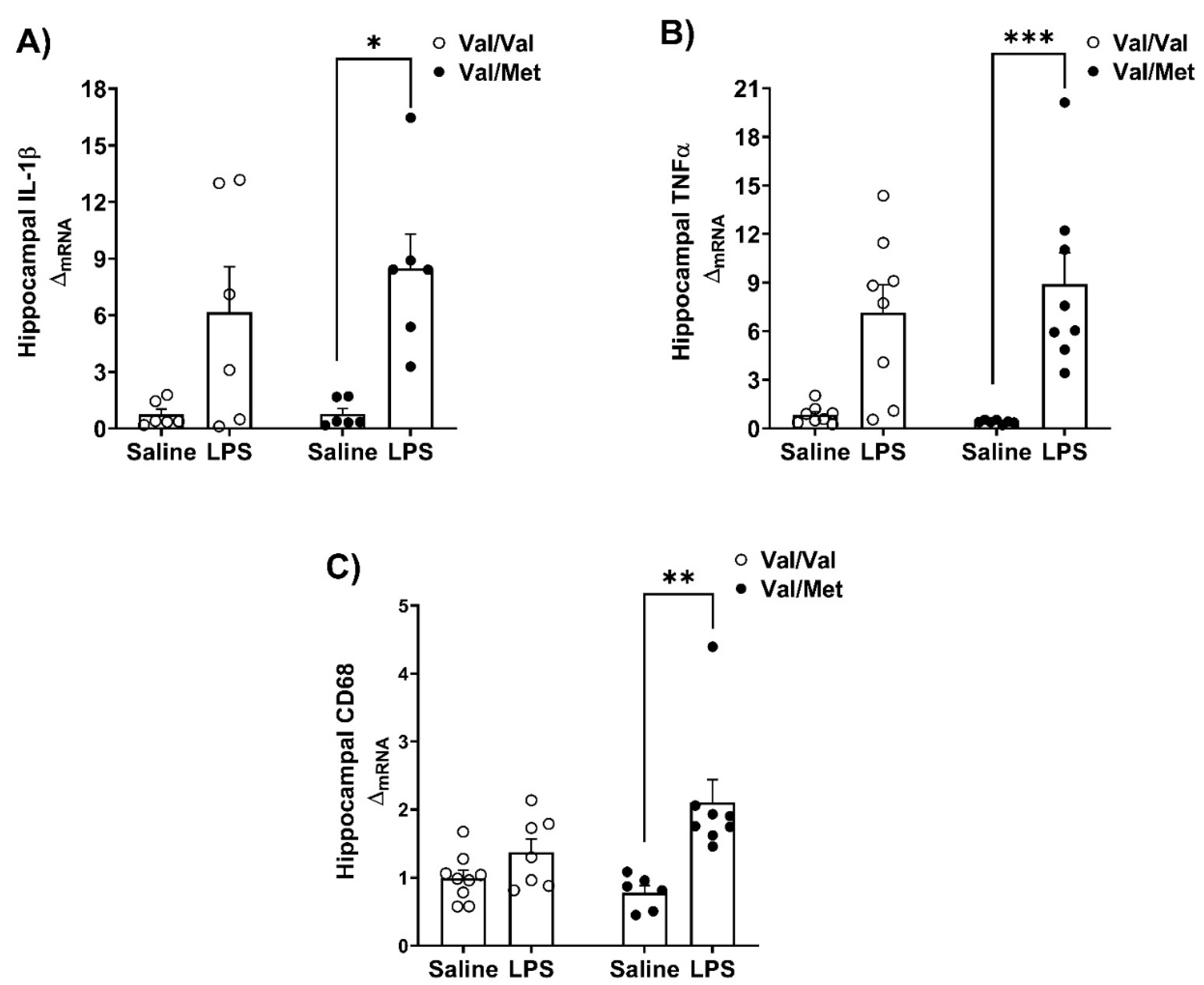

3.3. BDNF Val66Met Mutation Differentially Affects Brain Regions in Response to LPS

4. Discussion

Funding Statement and Acknowledgements:

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Friedrich, M.J. Depression Is the Leading Cause of Disability Around the World. JAMA. 1517. [Google Scholar]

- Dodd, S.; Bauer, M.; Carvalho, A.F.; Eyre, H.; Fava, M.; Kasper, S.; Kennedy, S.H.; Khoo, J.P.; Lopez Jaramillo, C.; Malhi, G.S.; et al. A clinical approach to treatment resistance in depressed patients: What to do when the usual treatments don't work well enough? World J Biol Psychiatry. 2021, 22, 483–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felger, J.C.; Haroon, E.; Miller, A.H. Risk and Resilience: Animal Models Shed Light on the Pivotal Role of Inflammation in Individual Differences in Stress-Induced Depression. Biological Psychiatry. 2015, 78, 7–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimeno, D.; Kivimäki, M.; Brunner, E.J.; Elovainio, M.; De Vogli, R.; Steptoe, A.; Kumari, M.; Lowe, G.D.O.; Rumley, A.; Marmot, M.G.; et al. Associations of C-reactive protein and interleukin-6 with cognitive symptoms of depression: 12-year follow-up of the Whitehall II study. Psychological Medicine. 2009, 39, 413–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed, S.A.; Beurel, E.; Loewenstein, D.A.; Lowell, J.A.; Craighead, W.E.; Dunlop, B.W.; Mayberg, H.S.; Dhabhar, F.; Dietrich, W.D.; Keane, R.W.; et al. Defective Inflammatory Pathways in Never-Treated Depressed Patients Are Associated with Poor Treatment Response. Neuron. 2018, 99, 914–924.e913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raison, C.L.; Rutherford, R.E.; Woolwine, B.J.; Shuo, C.; Schettler, P.; Drake, D.F.; Haroon, E.; Miller, A.H. A Randomized Controlled Trial of the Tumor Necrosis Factor Antagonist Infliximab for Treatment-Resistant Depression. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013, 70, 31–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frank, P.; Jokela, M.; Batty, G.D.; Cadar, D.; Steptoe, A.; Kivimaki, M. Association Between Systemic Inflammation and Individual Symptoms of Depression: A Pooled Analysis of 15 Population-Based Cohort Studies. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2021, 178, 1107–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, B.-H.; Kim, Y.-K. The Roles of BDNF in the Pathophysiology of Major Depression and in Antidepressant Treatment. Psychiatry Investigation. 2010, 7, 231–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molendijk, M.L.; Bus, B.A.A.; Spinhoven, P.; Penninx, B.W.J.H.; Kenis, G.; Prickaerts, J.; Voshaar, R.C.O.; Elzinga, B.M. Serum levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in major depressive disorder: State–trait issues, clinical features and pharmacological treatment. Molecular Psychiatry. 2011, 16, 1088–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, G.N.; Ren, X.; Rizavi, H.S.; Conley, R.R.; Roberts, R.C.; Dwivedi, Y. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor and tyrosine kinase B receptor signalling in post-mortem brain of teenage suicide victims. The International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008, 11, 1047–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, B.; Shelton, R.C.; Dwivedi, Y. DNA methylation and expression of stress related genes in PBMC of MDD patients with and without serious suicidal ideation. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2017, 89, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bus, B.A.; Molendijk, M.L.; Tendolkar, I.; Penninx, B.W.; Prickaerts, J.; Elzinga, B.M.; Voshaar, R.C. Chronic depression is associated with a pronounced decrease in serum brain-derived neurotrophic factor over time. Mol. Psychiatry. 2015, 20, 602–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duman, R.S.; Monteggia, L.M. A neurotrophic model for stress-related mood disorders. Biol. Psychiatry. 2006, 59, 1116–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castren, E.; Monteggia, L.M. Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor Signaling in Depression and Antidepressant Action. Biol. Psychiatry. 2021, 90, 128–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, Y.Y.; Ruan, C.S.; Yang, C.R.; Li, J.Y.; Kang, Z.L.; Zhou, L.; Liu, D.; Zeng, Y.Q.; Wang, T.H.; Tian, C.F.; et al. ProBDNF Signaling Regulates Depression-Like Behaviors in Rodents under Chronic Stress. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2016, 41, 2882–2892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alboni, S.; van Dijk, R.M.; Poggini, S.; Milior, G.; Perrotta, M.; Drenth, T.; Brunello, N.; Wolfer, D.P.; Limatola, C.; Amrein, I.; et al. Fluoxetine effects on molecular, cellular and behavioral endophenotypes of depression are driven by the living environment. Mol. Psychiatry. 2017, 22, 552–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duman, C.H.; Schlesinger, L.; Kodama, M.; Russell, D.S.; Duman, R.S. A Role for MAP Kinase Signaling in Behavioral Models of Depression and Antidepressant Treatment. Biological Psychiatry. 2007, 61, 661–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dugan, A.M.; Parrott, J.M.; Redus, L.; Hensler, J.G.; O’Connor, J.C. Low-Level Stress Induces Production of Neuroprotective Factors in Wild-Type but Not BDNF <sup>+/-</sup> Mice: Interleukin-10 and Kynurenic Acid. International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2016, 19, pyv089–pyv089. [Google Scholar]

- Parrott, J.M.; Porter, G.A.; Redus, L.; O'Connor, J.C. Brain derived neurotrophic factor deficiency exacerbates inflammation-induced anhedonia in mice. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2021, 134, 105404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, G.A.; O'Connor, J.C. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor and inflammation in depression: Pathogenic partners in crime? World J Psychiatry. 2022, 12, 77–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.Y. The Correlation between Plasma Brain-derived Neurotrophic Factor and Cognitive Function in Bipolar Disorder is Modulated by the BDNF Val66Met Polymorphism. European Psychiatry. 2017, 41, S76–S76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soliman, F.; Glatt, C.E.; Bath, K.G.; Levita, L.; Jones, R.M.; Pattwell, S.S.; Jing, D.; Tottenham, N.; Amso, D.; Somerville, L.H.; et al. A Genetic Variant BDNF Polymorphism Alters Extinction Learning in Both Mouse and Human. Science. 2010, 327, 863–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egan, M.F.; Kojima, M.; Callicott, J.H.; Goldberg, T.E.; Kolachana, B.S.; Bertolino, A.; Zaitsev, E.; Gold, B.; Goldman, D.; Dean, M.; et al. The BDNF val66met Polymorphism Affects Activity-Dependent Secretion of BDNF and Human Memory and Hippocampal Function. Cell. 2003, 112, 257–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adachi, N. New insight in expression, transport, and secretion of brain-derived neurotrophic factor: Implications in brain-related diseases. World Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2014, 5, 409–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.-Y.; Jing, D.; Bath, K.G.; Ieraci, A.; Khan, T.; Siao, C.-J.; Herrera, D.G.; Toth, M.; Yang, C.; McEwen, B.S.; et al. Genetic Variant BDNF (Val66Met) Polymorphism Alters Anxiety-Related Behavior. Science. 2006, 314, 140–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, S.; Hallmayer, J.; Wang, P.W.; Hill, S.J.; Johnson, S.L.; Ketter, T.A. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor val66met genotype and early life stress effects upon bipolar course. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2013, 47, 252–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daskalakis, N.P.; De Kloet, E.R.; Yehuda, R.; Malaspina, D.; Kranz, T.M. Early Life Stress Effects on Glucocorticoid-BDNF Interplay in the Hippocampus. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2015, 8, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, M.; Chen, L.; Yang, J.; Han, D.; Fang, D.; Qiu, X.; Yang, X.; Qiao, Z.; Ma, J.; Wang, L.; et al. BDNF Val66Met polymorphism, life stress and depression: A meta-analysis of gene-environment interaction. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2018, 227, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caldieraro, M.A.; McKee, M.; Leistner-Segal, S.; Vares, E.A.; Kubaski, F.; Spanemberg, L.; Brusius-Facchin, A.C.; Fleck, M.P.; Mischoulon, D. Val66Met polymorphism association with serum BDNF and inflammatory biomarkers in major depression. The World Journal of Biological Psychiatry. 2018, 19, 402–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lotrich, F.E.; Albusaysi, S.; Ferrell, R.E. Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor Serum Levels and Genotype: Association with Depression during Interferon-α Treatment. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013, 38, 985–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dooley, L.N.; Ganz, P.A.; Cole, S.W.; Crespi, C.M.; Bower, J.E. Val66Met BDNF polymorphism as a vulnerability factor for inflammation-associated depressive symptoms in women with breast cancer. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2016, 197, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindholm, J.S.; Castren, E. Mice with altered BDNF signaling as models for mood disorders and antidepressant effects. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parrott, J.M.; Redus, L.; Santana-Coelho, D.; Morales, J.; Gao, X.; O'Connor, J.C. Neurotoxic kynurenine metabolism is increased in the dorsal hippocampus and drives distinct depressive behaviors during inflammation. Translational Psychiatry. 2016, 6, e918–e918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laumet, G.; Zhou, W.; Dantzer, R.; Edralin, J.D.; Huo, X.; Budac, D.P.; O'Connor, J.C.; Lee, A.W.; Heijnen, C.J.; Kavelaars, A. Upregulation of neuronal kynurenine 3-monooxygenase mediates depression-like behavior in a mouse model of neuropathic pain. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 2017, 66, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.R.; O'Connor, J.C.; Hartman, M.E.; Tapping, R.I.; Freund, G.G. Acute Hypoxia Activates the Neuroimmune System, Which Diabetes Exacerbates. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2007, 27, 1161–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarnyai, Z.; Sibille, E.L.; Pavlides, C.; Fenster, R.J.; McEwen, B.S.; Tóth, M. Impaired hippocampal-dependent learning and functional abnormalities in the hippocampus in mice lacking serotonin <sub>1A</sub> receptors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2000, 97, 14731–14736. [Google Scholar]

- Bussey, T.J.; Padain, T.L.; Skillings, E.A.; Winters, B.D.; Morton, A.J.; Saksida, L.M. The touchscreen cognitive testing method for rodents: How to get the best out of your rat. Learning & Memory. 2008, 15, 516–523. [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos, G.; Franklin, K.B.J. Paxinos and Franklin's the Mouse Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. 2012.

- Schmittgen, T.D.; Livak, K.J. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative CT method. Nature Protocols. 2008, 3, 1101–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heisler, J.M.; O’Connor, J.C. Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase-dependent neurotoxic kynurenine metabolism mediates inflammation-induced deficit in recognition memory. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 2015, 50, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapolsky, R.M. Depression, antidepressants, and the shrinking hippocampus. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2001, 98, 12320–12322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heshmati, M.; Russo, S.J. Anhedonia and the Brain Reward Circuitry in Depression. Current Behavioral Neuroscience Reports. 2015, 2, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirayama, Y.; Chaki, S. Neurochemistry of the Nucleus Accumbens and its Relevance to Depression and Antidepressant Action in Rodents. Current Neuropharmacology. 2006, 4, 277–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gourley, S.L.; Kiraly, D.D.; Howell, J.L.; Olausson, P.; Taylor, J.R. Acute Hippocampal Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor Restores Motivational and Forced Swim Performance After Corticosterone. Biological Psychiatry. 2008, 64, 884–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gyekis, J.P.; Yu, W.; Dong, S.; Wang, H.; Qian, J.; Kota, P.; Yang, J. No association of genetic variants in BDNF with major depression: A meta- and gene-based analysis. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2013, 162B, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Chang, H.; Xiao, X. BDNF Val66Met polymorphism and bipolar disorder in European populations: A risk association in case-control, family-based and GWAS studies. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2016, 68, 218–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, H.; Wang, D.D.; Wang, Y.; Liu, T.; Lee, F.S.; Chen, Z.Y. Variant brain-derived neurotrophic factor Val66Met polymorphism alters vulnerability to stress and response to antidepressants. J. Neurosci. 2012, 32, 4092–4101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Li, X.; McGue, M. Interacting effect of BDNF Val66Met polymorphism and stressful life events on adolescent depression. Genes. Brain Behav. 2012, 11, 958–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notaras, M.; Du, X.; Gogos, J.; van den Buuse, M.; Hill, R.A. The BDNF Val66Met polymorphism regulates glucocorticoid-induced corticohippocampal remodeling and behavioral despair. Transl. Psychiatry. 2017, 7, e1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Connor, J.C.; Lawson, M.A.; Andre, C.; Moreau, M.; Lestage, J.; Castanon, N.; Kelley, K.W.; Dantzer, R. Lipopolysaccharide-induced depressive-like behavior is mediated by indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase activation in mice. Mol. Psychiatry. 2009, 14, 511–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capuron, L.; Miller, A.H. Immune system to brain signaling: Neuropsychopharmacological implications. Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2011, 130, 226–238. [Google Scholar]

- Felger, J.C.; Miller, A.H. Cytokine effects on the basal ganglia and dopamine function: The subcortical source of inflammatory malaise. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 2012, 33, 315–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felger, J.C.; Lotrich, F.E. Inflammatory cytokines in depression: Neurobiological mechanisms and therapeutic implications. Neuroscience. 2013, 246, 199–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekhbat, M.; Treadway, M.T.; Felger, J.C. Inflammation as a Pathophysiologic Pathway to Anhedonia: Mechanisms and Therapeutic Implications. Curr. Top. Behav. Neurosci. 2022, 58, 397–419. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dantzer, R.; O'Connor, J.C.; Freund, G.G.; Johnson, R.W.; Kelley, K.W. From inflammation to sickness and depression: When the immune system subjugates the brain. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2008, 9, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Yao, T.; Cai, J.; Fu, X.; Li, H.; Wu, J. Systemic inflammatory regulators and 7 major psychiatric disorders: A two-sample Mendelian randomization study. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 2022, 116, 110534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banks, W.A.; Kastin, A.J.; Gutierrez, E.G. Penetration of interleukin-6 across the murine blood-brain barrier. Neuroscience Letters. 1994, 179, 53–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goehler, L.E.; Relton, J.K.; Dripps, D.; Kiechle, R.; Tartaglia, N.; Maier, S.F.; Watkins, L.R. Vagal Paraganglia Bind Biotinylated Interleukin-1 Receptor Antagonist: A Possible Mechanism for Immune-to-Brain Communication. Brain Research Bulletin. 1997, 43, 357–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wohleb, E.S.; McKim, D.B.; Sheridan, J.F.; Godbout, J.P. Monocyte trafficking to the brain with stress and inflammation: A novel axis of immune-to-brain communication that influences mood and behavior. Front. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reader, B.F.; Jarrett, B.L.; McKim, D.B.; Wohleb, E.S.; Godbout, J.P.; Sheridan, J.F. Peripheral and central effects of repeated social defeat stress: Monocyte trafficking, microglial activation, and anxiety. Neuroscience. 2015, 289, 429–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKim, D.B.; Yin, W.; Wang, Y.; Cole, S.W.; Godbout, J.P.; Sheridan, J.F. Social Stress Mobilizes Hematopoietic Stem Cells to Establish Persistent Splenic Myelopoiesis. Cell Rep. 2018, 25, 2552–2562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKim, D.B.; Weber, M.D.; Niraula, A.; Sawicki, C.M.; Liu, X.; Jarrett, B.L.; Ramirez-Chan, K.; Wang, Y.; Roeth, R.M.; Sucaldito, A.D.; et al. Microglial recruitment of IL-1β-producing monocytes to brain endothelium causes stress-induced anxiety. Molecular Psychiatry. 2018, 23, 1421–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menard, C.; Pfau, M.L.; Hodes, G.E.; Kana, V.; Wang, V.X.; Bouchard, S.; Takahashi, A.; Flanigan, M.E.; Aleyasin, H.; LeClair, K.B.; et al. Social stress induces neurovascular pathology promoting depression. Nat. Neurosci. 2017, 20, 1752–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaire, S.; An, J.; Yang, H.; Lee, K.A.; Dumre, M.; Lee, E.J.; Park, S.M.; Joe, E.H. Systemic inflammation attenuates the repair of damaged brains through reduced phagocytic activity of monocytes infiltrating the brain. Mol. Brain. 2024, 17, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazareth, J.; Guyon, A.; Heurteaux, C.; Chabry, J.; Petit-Paitel, A. Molecular and cellular neuroinflammatory status of mouse brain after systemic lipopolysaccharide challenge: Importance of CCR2/CCL2 signaling. Journal of Neuroinflammation. 2014, 11, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bodea, L.G.; Wang, Y.; Linnartz-Gerlach, B.; Kopatz, J.; Sinkkonen, L.; Musgrove, R.; Kaoma, T.; Muller, A.; Vallar, L.; Di Monte, D.A.; et al. Neurodegeneration by activation of the microglial complement-phagosome pathway. J. Neurosci. 2014, 34, 8546–8556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeo, H.G.; Hong, J.J.; Lee, Y.; Yi, K.S.; Jeon, C.Y.; Park, J.; Won, J.; Seo, J.; Ahn, Y.J.; Kim, K.; et al. Increased CD68/TGFbeta Co-expressing Microglia/ Macrophages after Transient Middle Cerebral Artery Occlusion in Rhesus Monkeys. Exp. Neurobiol. 2019, 28, 458–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chistiakov, D.A.; Killingsworth, M.C.; Myasoedova, V.A.; Orekhov, A.N.; Bobryshev, Y.V. CD68/macrosialin: Not just a histochemical marker. Lab. Invest. 2017, 97, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, N.; Zhang, Y.; Tan, S.; Sun, J.; Ye, M.; Gao, H.; Pu, K.; Wu, M.; Wang, Q.; Zhai, Q. Therapeutic targeting of STING-TBK1-IRF3 signalling ameliorates chronic stress induced depression-like behaviours by modulating neuroinflammation and microglia phagocytosis. Neurobiol. Dis. 2022, 169, 105739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Fan, Y.; Chung, C.Y. Mefenamic acid can attenuate depressive symptoms by suppressing microglia activation induced upon chronic stress. Brain Res. 2020, 1740, 146846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Haddad, Y.; Yun, H.J.; Geng, X.; Ding, Y. Induced Inflammatory and Oxidative Markers in Cerebral Microvasculature by Mentally Depressive Stress. Mediators Inflamm. 2023, 2023, 4206316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandrini, L.; Castiglioni, L.; Amadio, P.; Werba, J.P.; Eligini, S.; Fiorelli, S.; Zara, M.; Castiglioni, S.; Bellosta, S.; Lee, F.S.; et al. Impact of BDNF Val66Met Polymorphism on Myocardial Infarction: Exploring the Macrophage Phenotype. Cells. 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, J.D.; Rubin, T.G.; Kogan, J.F.; Marrocco, J.; Weidmann, J.; Lindkvist, S.; Lee, F.S.; Schmidt, E.F.; McEwen, B.S. Translational profiling of stress-induced neuroplasticity in the CA3 pyramidal neurons of BDNF Val66Met mice. Mol. Psychiatry. 2018, 23, 904–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, D.; Lee, F.S.; Ninan, I. The BDNF Val66Met polymorphism enhances glutamatergic transmission but diminishes activity-dependent synaptic plasticity in the dorsolateral striatum. Neuropharmacology. 2017, 112, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huwart, S.J.P.; Fayt, C.; Gangarossa, G.; Luquet, S.; Cani, P.D.; Everard, A. TLR4-dependent neuroinflammation mediates LPS-driven food-reward alterations during high-fat exposure. J. Neuroinflammation. 2024, 21, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Lai, S.; Zhou, T.; Xia, Z.; Li, W.; Sha, W.; Liu, J.; Chen, Y. Progranulin from different gliocytes in the nucleus accumbens exerts distinct roles in FTD- and neuroinflammation-induced depression-like behaviors. J. Neuroinflammation. 2022, 19, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Lai, S.; Wang, R.; Zhou, T.; Dong, N.; Zhu, L.; Chen, T.; Zhang, X.; Chen, Y. Dopamine D3 receptor in the nucleus accumbens alleviates neuroinflammation in a mouse model of depressive-like behavior. Brain Behav. Immun. 2022, 101, 165–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, S.F.; Seligman, M.E. Learned helplessness at fifty: Insights from neuroscience. Psychol. Rev. 2016, 123, 349–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dincheva, I.; Yang, J.; Li, A.; Marinic, T.; Freilingsdorf, H.; Huang, C.; Casey, B.J.; Hempstead, B.; Glatt, C.E.; Lee, F.S.; et al. Effect of Early-Life Fluoxetine on Anxiety-Like Behaviors in BDNF Val66Met Mice. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2017, 174, 1203–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bath, K.G.; Jing, D.Q.; Dincheva, I.; Neeb, C.C.; Pattwell, S.S.; Chao, M.V.; Lee, F.S.; Ninan, I. BDNF Val66Met impairs fluoxetine-induced enhancement of adult hippocampus plasticity. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012, 37, 1297–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, R.; Qi, Y.; Hou, D.N.; Ji, Y.Y.; Zheng, C.Y.; Li, C.Y.; Yung, W.H.; Lu, B.; Huang, Y. BDNF val66met Polymorphism Impairs Hippocampal Long-Term Depression by Down-Regulation of 5-HT3 Receptors. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2017, 11, 306. [Google Scholar]

- Mallei, A.; Ieraci, A.; Corna, S.; Tardito, D.; Lee, F.S.; Popoli, M. Global epigenetic analysis of BDNF Val66Met mice hippocampus reveals changes in dendrite and spine remodeling genes. Hippocampus. 2018, 28, 783–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ninan, I.; Bath, K.G.; Dagar, K.; Perez-Castro, R.; Plummer, M.R.; Lee, F.S.; Chao, M.V. The BDNF Val66Met polymorphism impairs NMDA receptor-dependent synaptic plasticity in the hippocampus. J. Neurosci. 2010, 30, 8866–8870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reichenberg, A.; Yirmiya, R.; Schuld, A.; Kraus, T.; Haack, M.; Morag, A.; Pollmächer, T. Cytokine-Associated Emotional and Cognitive Disturbances in Humans. Archives of General. Psychiatry. 2001, 58, 445–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Janicki-Deverts, D.; Doyle, W.J.; Miller, G.E.; Frank, E.; Rabin, B.S.; Turner, R.B. Chronic stress, glucocorticoid receptor resistance, inflammation, and disease risk. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2012, 109, 5995–5999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mac Giollabhui, N.; Ng, T.H.; Ellman, L.M.; Alloy, L.B. The longitudinal associations of inflammatory biomarkers and depression revisited: Systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Mol Psychiatry. 2021, 26, 3302–3314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Eeden, W.A.; van Hemert, A.M.; Carlier, I.V.E.; Penninx, B.; Lamers, F.; Fried, E.I.; Schoevers, R.; Giltay, EJ. Basal and LPS-stimulated inflammatory markers and the course of individual symptoms of depression. Transl. Psychiatry. 2020, 10, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Can, A.; Dao, D.T.; Arad, M.; Terrillion, C.E.; Piantadosi, S.C.; Gould, T.D. The mouse forced swim test. J Vis Exp. 2012, e3638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdanova, O.V.; Kanekar, S.; D'Anci, K.E.; Renshaw, P.F. Factors influencing behavior in the forced swim test. Physiol. Behav. 2013, 118, 227–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anyan, J.; Amir, S. Too Depressed to Swim or Too Afraid to Stop? A Reinterpretation of the Forced Swim Test as a Measure of Anxiety-Like Behavior. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2018, 43, 931–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montag, C.; Basten, U.; Stelzel, C.; Fiebach, C.J.; Reuter, M. The BDNF Val66Met polymorphism and anxiety: Support for animal knock-in studies from a genetic association study in humans. Psychiatry Research. 2010, 179, 86–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negron, M.; Kristensen, J.; Nguyen, V.T.; Gansereit, L.E.; Raucci, F.J.; Chariker, J.L.; Heck, A.; Brula, I.; Kitchen, G.; Awgulewitsch, C.P.; et al. Sex-Based Differences in Cardiac Gene Expression and Function in BDNF Val66Met Mice. Int J Mol Sci. 2021, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Bath, K.G.; Chuang, J.; Spencer-Segal, J.L.; Amso, D.; Altemus, M.; McEwen, B.S.; Lee, F.S. Variant brain-derived neurotrophic factor (Valine66Methionine) polymorphism contributes to developmental and estrous stage-specific expression of anxiety-like behavior in female mice. Biol. Psychiatry. 2012, 72, 499–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, M.; Morici, J.F.; Zanoni, M.B.; Bekinschtein, P. Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor: A Key Molecule for Memory in the Healthy and the Pathological Brain. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2019, 13, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Val/Val | Val/Met | Main Effects | Effect size | ||||||

| Saline | LPS | Saline | LPS | ||||||

| Mean (SEM) | Mean (SEM) | Mean (SEM) | Mean (SEM) | Genotype p-value |

Treatment p-value |

η2p | |||

| 2hrs | |||||||||

| IL-1β | 0.152 (0.152) | 7.596 (6.078) | 0.543 (0.543) | 4.381 (4.381) | 0.2413 | 0.7630 | na | ||

| IL-6 | 1.379 (0.939) | 195.172 (0.0) | 1.500 (0.815) | 152.397 (42.776) | 0.3461 | <0.0001**** | 0.839 | ||

| TNFα | 0.783 (0.783) | 73.288 (19.506) | 11.628 (11.533) | 40.409 (23.830) | 0.5309 | 0.0111* | 0.402 | ||

| 24hrs | |||||||||

| IL-1β | 2.841 (0.998) | 2.315 (1.037) | 3.460 (1.042) | 4.678 (1.903) | 0.8070 | 0.2981 | na | ||

| IL-6 | 0.539 (0.173) | 72.034 (27.041) | 0.956 (0.620) | 75.048 (17.211) | 0.9191 | 0.0001*** | 0.350 | ||

| TNFα | 1.296 (0.746) | 3.292 (1.370) | 0.543 (0.543) | 4.211 (0.644) | 0.9292 | 0.0064** | 0.345 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).