Submitted:

03 July 2025

Posted:

04 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- We propose DDRL, the first RL framework for options hedging that incorporates diffusion models as policy networks. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first attempt to combine diffusion models with RL for financial decision-making tasks.

- By dynamically incorporating step-wise profit-and-loss and trading costs into the reward, DDRL captures market frictions and avoids static risk assumptions, enabling consistent and adaptive hedging decisions over time.

- DDRL employs a dual-critic architecture with entropy regularization to enhance training stability, effectively addressing value overestimation and premature convergence in volatile hedging environments.

- We validate DDRL under realistic SABR-simulated market conditions, showing substantial improvements in hedging effectiveness in terms of cost efficiency, risk reduction, and policy robustness.

2. Related Work

2.1. Traditional Options Hedging Methods

2.2. RL for Dynamic Hedging

2.3. Diffusion Models in Optimization and RL

3. Deep Diffusion Reinforcement Learning for Options Hedging

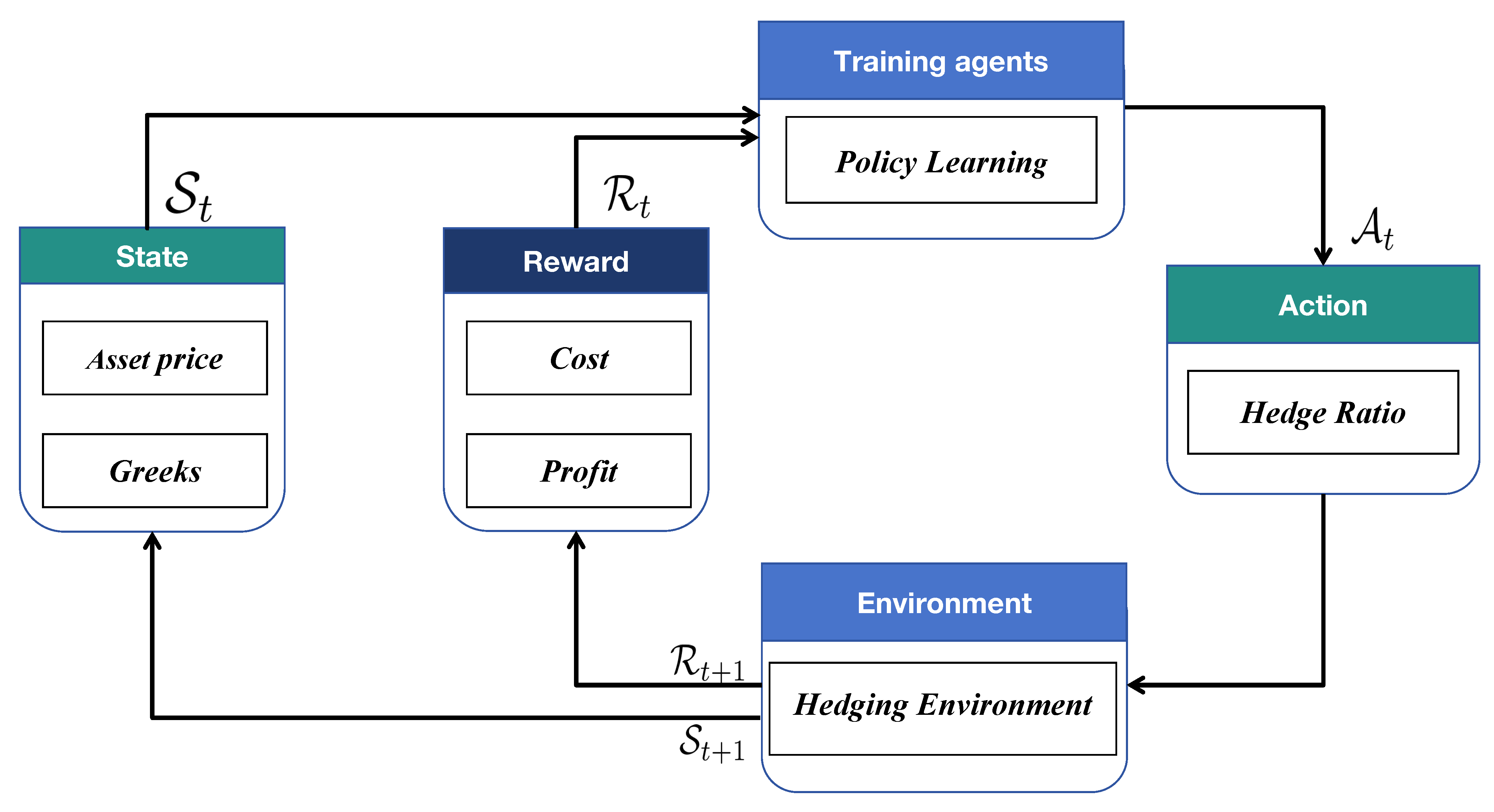

3.1. RL Formulation

- denotes the state space;

- is the action space;

- is the transition kernel that governs state dynamics;

- is the reward function;

- is the discount factor.

3.2. RL Design

3.2.1. State Representation

3.2.2. Action Space and Hedging Constraints

3.2.3. Reward Design

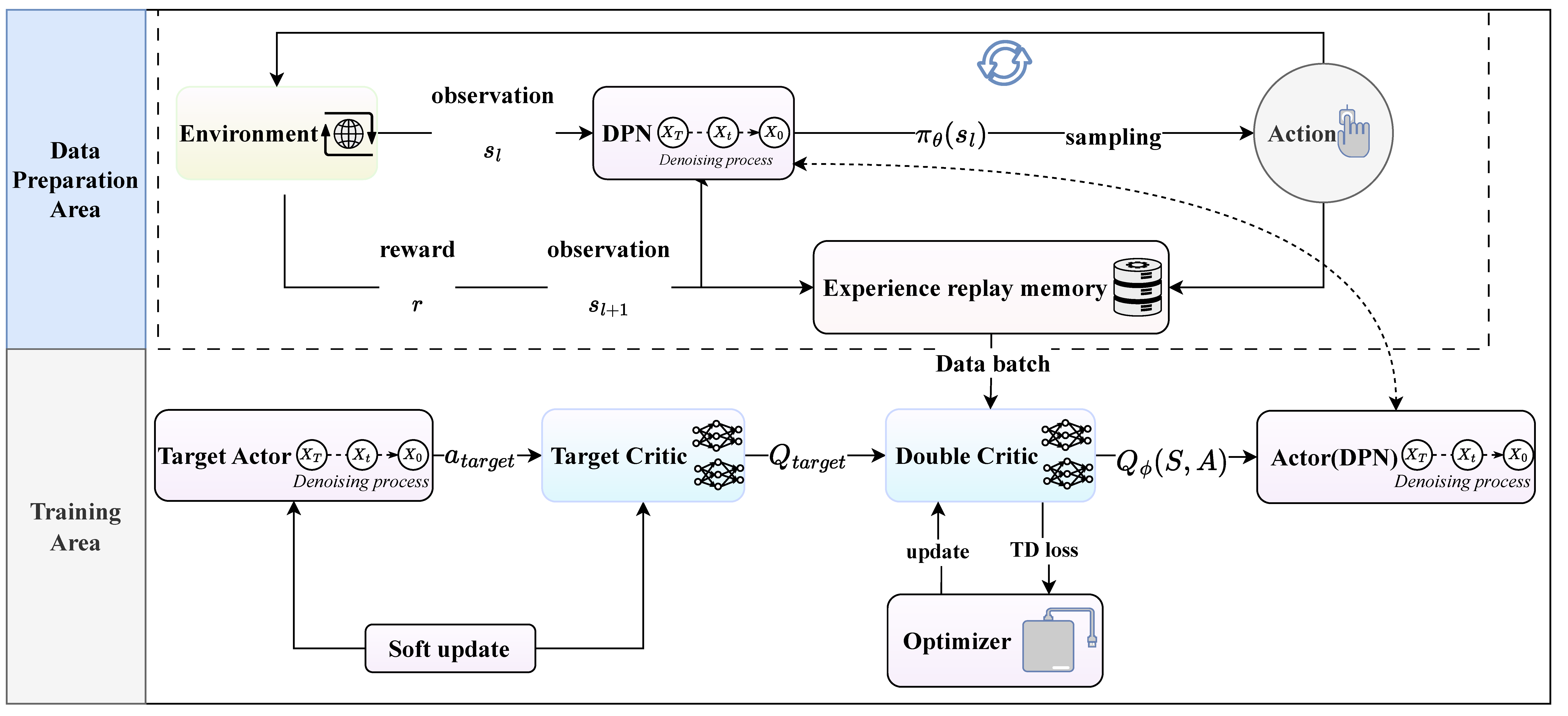

4. Algorithm Architecture

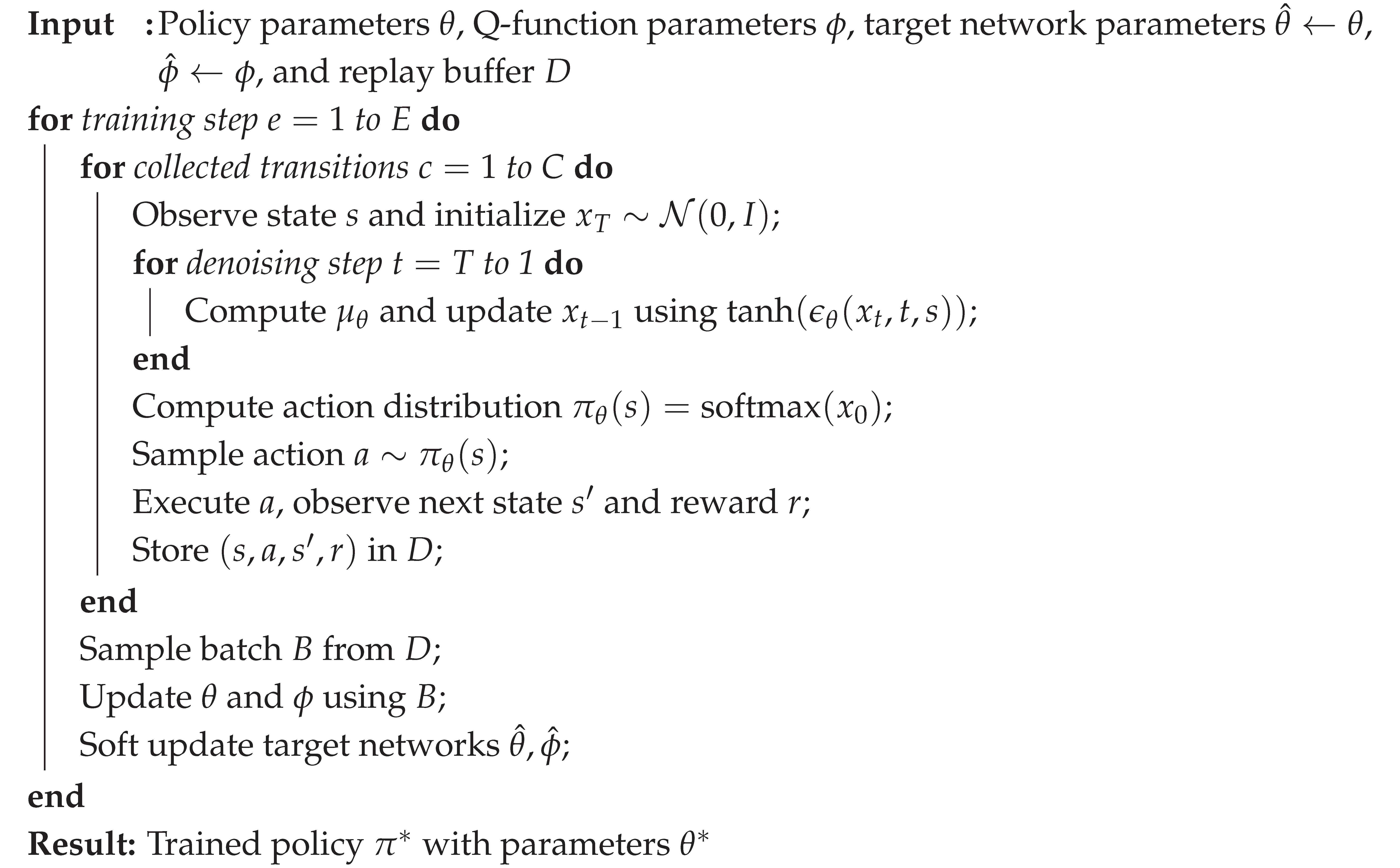

| Algorithm 1:DDRL: Deep Diffusion Reinforcement Learning |

|

4.1. Diffusion-Based Policy Network (DPN)

4.2. Trajectory Collection and Experience Replay

4.3. Policy Optimization with Entropy Regularization

4.4. Critic Learning and Target Value Estimation

5. Experiment

5.1. Datasets Simulation

5.2. Baselines

- Delta Hedging: Calculated by continuously adjusting the portfolio’s position to ensure that the Delta, or the sensitivity to small price changes in the underlying asset, is neutralized. The goal is to offset price movements by buying or selling the underlying asset.

- Delta-Gamma Hedging: This method adjusts both Delta and Gamma, meaning it neutralizes both the portfolio’s sensitivity to price changes (Delta) and the sensitivity of Delta itself (Gamma). This requires using additional options, making the process more complex but effective in reducing non-linear risk.

- RL: This baseline model is an effective RL method based on the [19], incorporating quantile regression to more accurately predict the distribution of losses and returns.

5.3. Evaluation Metrics

5.4. Experimental Settings

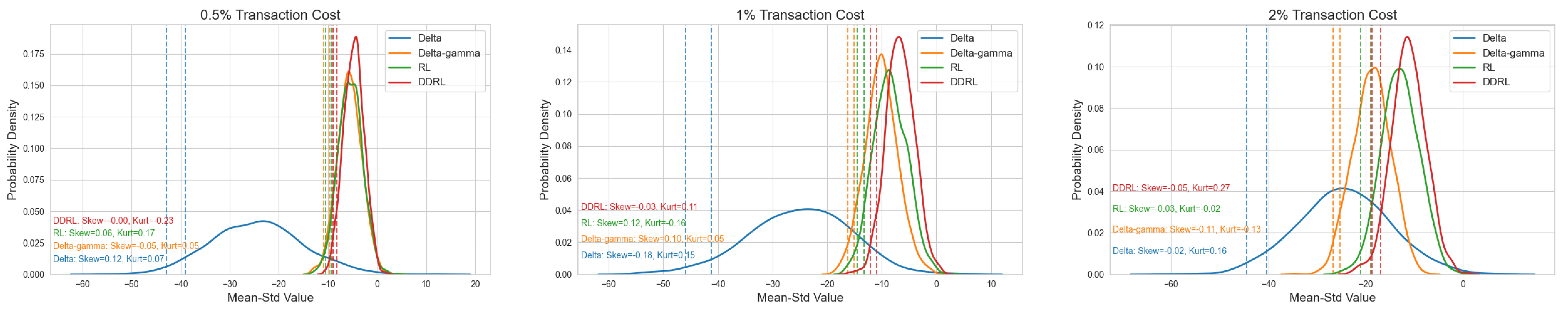

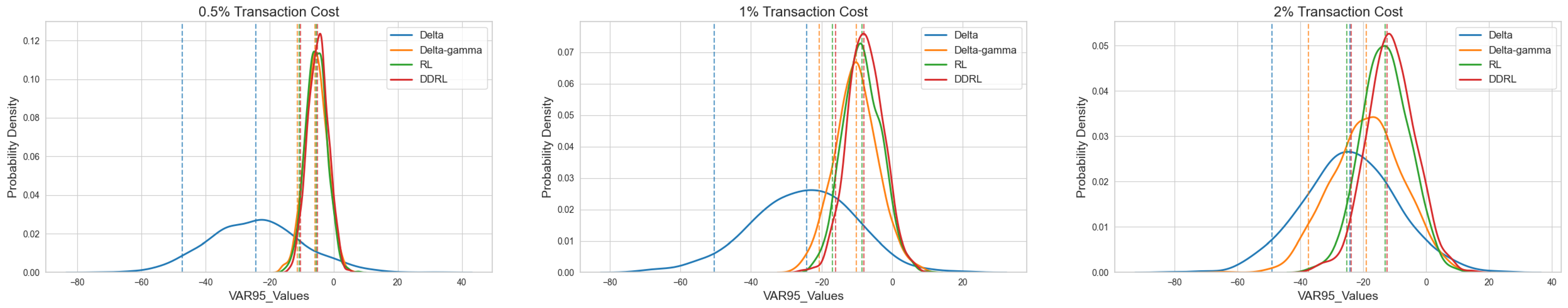

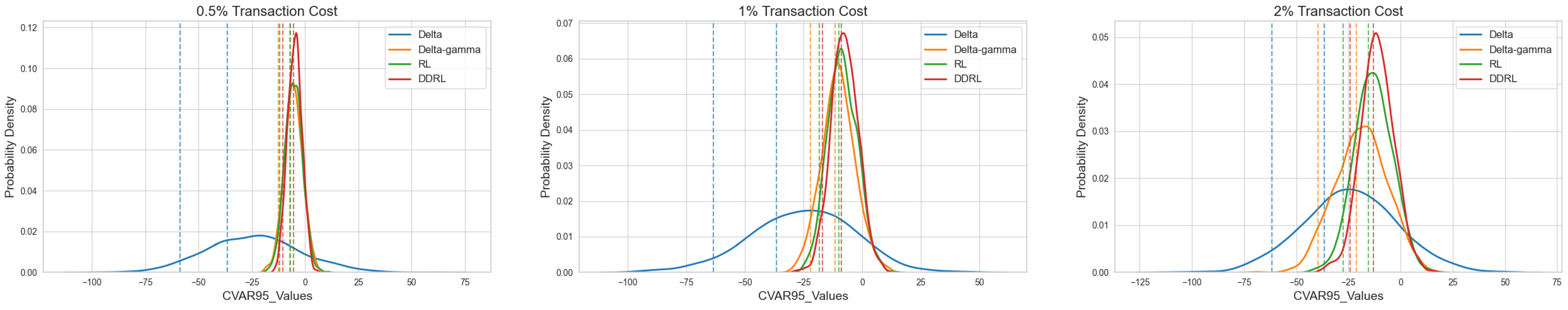

5.5. Hedging Results

- (1)

- Enhanced Risk Reduction via Diffusion-Based Policy Learning.

- 2.

- Precision in Gamma Hedging with Cost-Aware Frequency Adjustment.

- 3.

- Robustness Under High Transaction Costs.

- 4.

- Joint Improvement in Returns and Cost Efficiency.

5.6. Risk Limit Management Evaluation

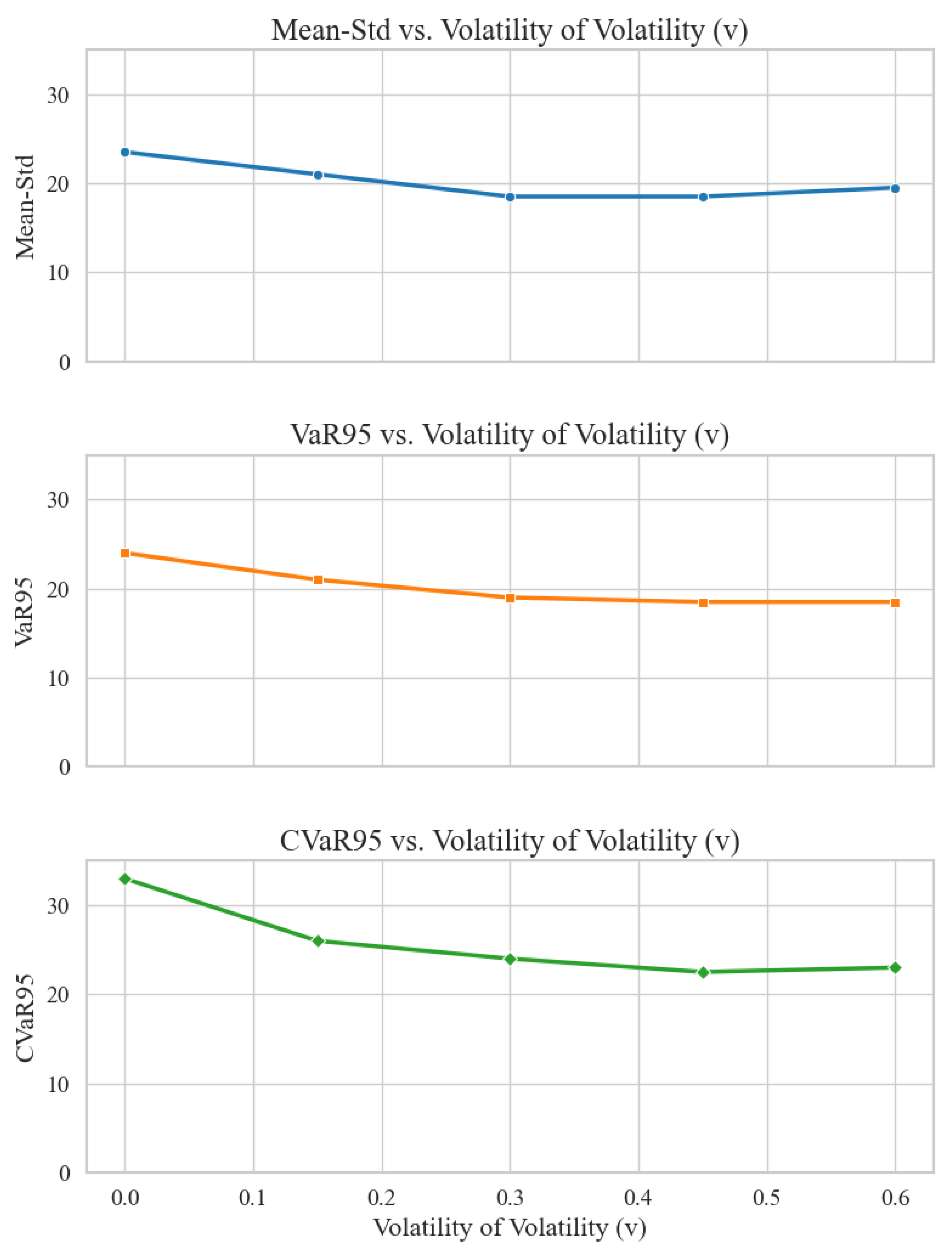

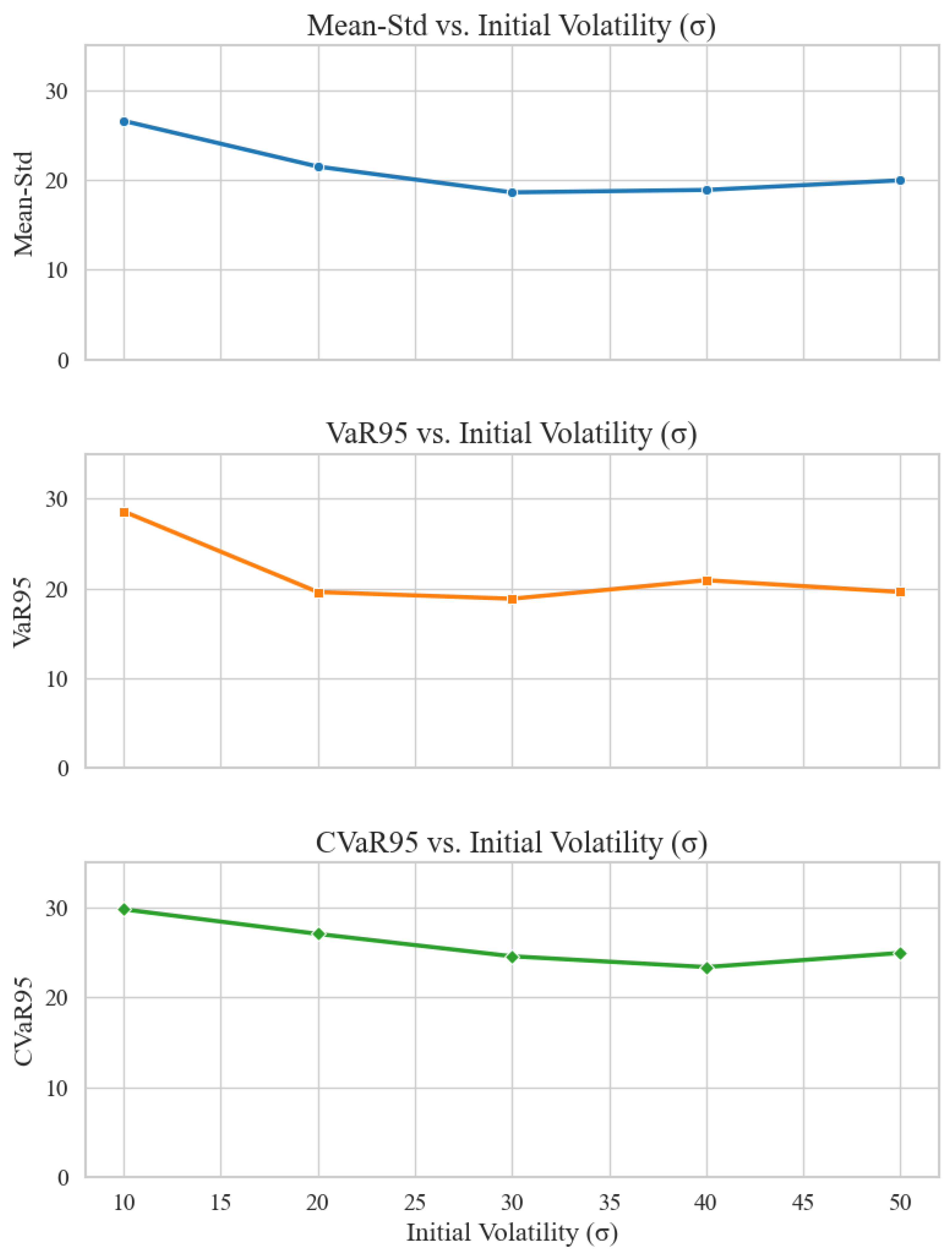

5.7. Robustness Test

5.7.1. Robustness under Model Misspecification

5.7.2. Robustness to Parameter Perturbations

6. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

References

- Jalilvand, M.; Bashiri, M.; Nikzad, E. An effective progressive hedging algorithm for the two-layers time window assignment vehicle routing problem in a stochastic environment. Expert Systems with Applications 2021, 165, 113877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Xi, Y.; Yu, F.; Sui, C. Time–frequency domain based optimization of hedging strategy: Evidence from CSI 500 spot and futures. Expert Systems with Applications 2024, 238, 121785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Feng, Y.; Meng, Q. Information dissemination behavior of self-media in emergency: Considering the impact of information synergistic-hedging effect on public utility. Expert Systems with Applications 2024, 252, 124110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.K.; Yang, D.Y.; Hsieh, M.H.; Wu, M.E. An intelligent option trading system based on heatmap analysis via PON/POD yields. Expert Systems with Applications 2024, 257, 124948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, F.; Scholes, M. The pricing of options and corporate liabilities. Journal of political economy 1973, 81, 637–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crépey, S. Delta-hedging vega risk? Quantitative Finance 2004, 4, 559–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzban, S.; Delage, E.; Li, J.Y.M. Equal risk pricing and hedging of financial derivatives with convex risk measures. Quantitative Finance 2022, 22, 47–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buehler, H.; Gonon, L.; Teichmann, J.; Wood, B. Deep hedging. Quantitative Finance 2019, 19, 1271–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Liu, R.; Lee, R.S. The design and implementation of a deep reinforcement learning and quantum finance theory-inspired portfolio investment management system. Expert Systems with Applications 2024, 238, 122243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbonneau, A.; Godin, F. Deep equal risk pricing of financial derivatives with multiple hedging instruments. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2102.12694 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Fecamp, S.; Mikael, J.; Warin, X. Deep learning for discrete-time hedging in incomplete markets. Journal of computational Finance 2020, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, R.J. Simple statistical gradient-following algorithms for connectionist reinforcement learning. Machine learning 1992, 8, 229–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H. Deep hedging, generative adversarial networks, and beyond. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2103.03913. [Google Scholar]

- Assa, H.; Kenyon, C.; Zhang, H. Assessing reinforcement delta hedging. Available at SSRN 3918375 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikkilä, O.; Kanniainen, J. Empirical deep hedging. Quantitative Finance 2023, 23, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silver, D.; Lever, G.; Heess, N.; Degris, T.; Wierstra, D.; Riedmiller, M. Deterministic policy gradient algorithms. In Proceedings of the International conference on machine learning. Pmlr; 2014; pp. 387–395. [Google Scholar]

- Fujimoto, S.; Hoof, H.; Meger, D. Addressing function approximation error in actor-critic methods. In Proceedings of the International conference on machine learning. PMLR; 2018; pp. 1587–1596. [Google Scholar]

- Marzban, S.; Delage, E.; Li, J.Y.M. Deep reinforcement learning for option pricing and hedging under dynamic expectile risk measures. Quantitative Finance 2023, 23, 1411–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Chen, J.; Farghadani, S.; Hull, J.; Poulos, Z.; Wang, Z.; Yuan, J. Gamma and vega hedging using deep distributional reinforcement learning. Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence 2023, 6, 1129370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.; He, J.; Yang, C. Option Dynamic Hedging Using Reinforcement Learning. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2306.10743. [Google Scholar]

- Ozbayoglu, A.M.; Gudelek, M.U.; Sezer, O.B. Deep learning for financial applications: A survey. Applied soft computing 2020, 93, 106384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lillicrap, T.P.; Hunt, J.J.; Pritzel, A.; Heess, N.; Erez, T.; Tassa, Y.; Silver, D.; Wierstra, D. Continuous control with deep reinforcement learning. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1509.02971. [Google Scholar]

- Haarnoja, T.; Zhou, A.; Abbeel, P.; Levine, S. Soft actor-critic: Off-policy maximum entropy deep reinforcement learning with a stochastic actor. In Proceedings of the International conference on machine learning. Pmlr; 2018; pp. 1861–1870. [Google Scholar]

- Ursone, P. How to calculate options prices and their greeks: exploring the black scholes model from delta to vega; John Wiley & Sons, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, B.; Yao, W.; Zhou, X. Optimal option hedging with policy gradient. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Data Mining Workshops (ICDMW); IEEE, 2021; pp. 1112–1119. [Google Scholar]

- Halperin, I. Qlbs: Q-learner in the black-scholes (-merton) worlds. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1712.04609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolm, P.N.; Ritter, G. Dynamic replication and hedging: A reinforcement learning approach. The Journal of Financial Data Science 2019, 1, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Jin, M.; Kolm, P.N.; Ritter, G.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, B. Deep reinforcement learning for option replication and hedging. The Journal of Financial Data Science 2020, 2, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vittori, E.; Trapletti, M.; Restelli, M. Option hedging with risk averse reinforcement learning. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the first ACM international conference on AI in finance, 2020, pp.

- Cao, J.; Chen, J.; Hull, J.; Poulos, Z. Deep hedging of derivatives using reinforcement learning. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2103.16409 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, U.; Luu, Q.; Tran, H. Multi-agent reinforcement learning approach for hedging portfolio problem. Soft Computing 2021, 25, 7877–7885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giurca, A.; Borovkova, S. Delta hedging of derivatives using deep reinforcement learning. Available at SSRN 3847272 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, P.; Wood, B.; Buehler, H.; Wiese, M.; Pakkanen, M. Deep hedging: Continuous reinforcement learning for hedging of general portfolios across multiple risk aversions. In Proceedings of the Third ACM International Conference on AI in Finance; 2022; pp. 361–368. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, W.; Dai, B. Delta-Gamma–Like Hedging with Transaction Cost under Reinforcement Learning Technique. The Journal of Derivatives 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannelli, L.; Nuti, G.; Sala, M.; Szehr, O. Hedging using reinforcement learning: Contextual k-armed bandit versus Q-learning. The Journal of Finance and Data Science 2023, 9, 100101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathi, A.; Hientzsch, B. A comparison of reinforcement learning and deep trajectory based stochastic control agents for stepwise mean-variance hedging. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2302.07996 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shavandi, A.; Khedmati, M. A multi-agent deep reinforcement learning framework for algorithmic trading in financial markets. Expert Systems with Applications 2022, 208, 118124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulhaq, A.; Akhtar, N. Efficient diffusion models for vision: A survey. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2210.09292 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Du, H.; Zhang, R.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Lin, Y.; Li, Z.; Niyato, D.; Kang, J.; Xiong, Z.; Cui, S.; et al. Beyond deep reinforcement learning: A tutorial on generative diffusion models in network optimization. arXiv preprint arXiv:2308.05384 2023, 3, 1661–1665. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Hunt, J.J.; Zhou, M. Diffusion policies as an expressive policy class for offline reinforcement learning. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2208.06193 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Du, H.; Wang, J.; Niyato, D.; Kang, J.; Xiong, Z.; Kim, D.I. AI-generated incentive mechanism and full-duplex semantic communications for information sharing. IEEE Journal on Selected Areas in Communications 2023, 41, 2981–2997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagan, P.S.; Kumar, D.; Lesniewski, A.S.; Woodward, D.E. Managing smile risk. The Best of Wilmott 2002, 1, 249–296. [Google Scholar]

| Source | Method | State | Action | Reward | Train Data | Test Data |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [26] | Q-Learning | Disc. | GBM | GBM | ||

| [27] | SARSA | Disc. | GBM | GBM | ||

| [28] | DQN, PPO | Disc. | GBM | GBM | ||

| [29] | TRVO | Cont. | GBM | GBM | ||

| [30] | DDPG | Cont. | GBM, SABR | GBM, SABR | ||

| [31] | IMPALA | Disc. | HSX, HNX | HSX, HNX | ||

| [32] | DQN, DDPG | Disc. | GBM, Heston | GBM, Heston, S&P | ||

| [25] | Policy Gradient w/ Baseline | Disc. | GBM, Heston | GBM, Heston, S&P | ||

| [13] | Direct Policy Search | Cont. | CVaR | GBM, GAN | GBM, GAN | |

| [14] | DDPG | Cont. | Payoff | Heston | Heston | |

| [33] | Actor-Critic | Cont. | S&P, DJIA | S&P, DJIA | ||

| [34] | DDPG | Cont. | S&P, DJIA | S&P, DJIA | ||

| [15] | TD3 | Cont. | CVaR | SABR | SABR | |

| [19] | D4PG-QR | Cont. | CVaR + mean-var | SABR | SABR | |

| [20] | DDPG, DDPG-U | Cont. | GBM, S&P | GBM, S&P | ||

| [35] | CMAB | Disc. | GBM | GBM | ||

| [36] | DDPG | Cont. | Min | GBM | GBM |

| Item | Details |

|---|---|

| Underlying Asset | 100 units of the underlying asset, with a 50% chance of being long or short per order. |

| Option Contract Term | 60-day option contract. |

| Hedging Tool | 30-day at-the-money (ATM) option. |

| Order Arrival Process | Poisson process with a daily intensity of 1.0, resulting in one order per day on average. |

| Initial Stock Price | $10.00 |

| Annualized Volatility | 30% |

| Transaction Costs | 0.5%, 1%, and 2% of the option price. |

| Hedging Frequency | Daily hedging, dynamically adjusted based on market conditions. |

| Hedging Period | 30 days, using a 30-day ATM option. |

| Training Iterations | 50,000 iterations. |

| Evaluation Iterations | 10,000 iterations. |

| Number of Test Scenarios | Over 5,000 test scenarios, distinct from training scenarios. |

| Objective | Delta | Delta-gamma | RL | DDRL | R(RL) | R(DDRL) | IR | TCR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.5% transaction cost | ||||||||

| Mean-Std | 24.61 | 5.78 | 5.44 | 5.01 | 0.83 | 0.89 | 1.11% | 13.30% |

| VaR95 | 24.29 | 5.78 | 5.47 | 5.02 | 0.75 | 0.80 | 0.67% | 21.71% |

| CVaR95 | 36.64 | 7.13 | 6.78 | 5.99 | 0.79 | 0.85 | 0.75% | 31.53% |

| 1% transaction cost | ||||||||

| Mean-Std | 24.61 | 9.93 | 8.36 | 7.68 | 0.57 | 0.63 | 10.52% | 8.71% |

| VaR95 | 24.29 | 10.12 | 8.63 | 8.02 | 0.56 | 0.62 | 12.50% | 9.52% |

| CVaR95 | 36.64 | 11.55 | 10.02 | 9.27 | 0.60 | 0.67 | 11.70% | 17.50% |

| 2% transaction cost | ||||||||

| Mean-Std | 24.61 | 18.74 | 12.73 | 12.12 | 0.30 | 0.41 | 36.67% | 17.63% |

| VaR95 | 24.29 | 19.11 | 13.05 | 12.51 | 0.24 | 0.34 | 29.41% | 10.50% |

| CVaR95 | 36.64 | 21.10 | 15.37 | 14.96 | 0.29 | 0.38 | 37.93% | 19.37% |

| Transaction Cost | Objective Function | Delta-Gamma | RL | DDRL |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.5% | Mean-Std | 7.27 | 6.80 | 5.01 |

| VaR95 | 7.40 | 6.43 | 6.02 | |

| CVaR95 | 9.20 | 7.84 | 6.93 | |

| 1.0% | Mean-Std | 9.59 | 9.19 | 9.01 |

| VaR95 | 9.69 | 8.86 | 8.12 | |

| CVaR95 | 11.62 | 10.39 | 9.68 | |

| 2.0% | Mean-Std | 14.85 | 13.34 | 12.51 |

| VaR95 | 15.17 | 13.29 | 11.97 | |

| CVaR95 | 17.44 | 15.33 | 14.65 |

| Hedge Maturity | Objective Function | Delta | Delta-Gamma | Delta-Vega | RL | DDRL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transaction Costs = 0.5% | ||||||

| 30 days | Mean-Std | 35.76 | 19.46 | 44.82 | 17.76 | 15.27 |

| VaR95 | 34.43 | 19.23 | 42.90 | 19.31 | 18.53 | |

| CVaR95 | 52.91 | 27.53 | 62.77 | 26.06 | 24.77 | |

| 90 days | Mean-Std | 35.76 | 25.25 | 15.47 | 14.28 | 13.96 |

| VaR95 | 34.43 | 24.43 | 15.40 | 14.41 | 12.65 | |

| CVaR95 | 52.91 | 31.96 | 20.21 | 18.17 | 17.23 | |

| Transaction Costs = 1% | ||||||

| 30 days | Mean-Std | 35.76 | 23.06 | 51.36 | 20.03 | 17.99 |

| VaR95 | 34.43 | 23.02 | 50.24 | 20.22 | 18.89 | |

| CVaR95 | 52.91 | 31.55 | 69.92 | 26.81 | 21.23 | |

| 90 days | Mean-Std | 35.76 | 35.20 | 22.05 | 18.61 | 17.66 |

| VaR95 | 34.43 | 35.01 | 22.05 | 18.86 | 16.98 | |

| CVaR95 | 52.91 | 42.63 | 27.18 | 24.58 | 19.77 | |

| Transaction Costs = 2% | ||||||

| 30 days | Mean-Std | 35.76 | 30.51 | 64.77 | 24.17 | 21.31 |

| VaR95 | 34.43 | 30.67 | 64.56 | 23.85 | 19.89 | |

| CVaR95 | 52.91 | 39.79 | 84.38 | 31.57 | 28.75 | |

| 90 days | Mean-Std | 35.76 | 56.67 | 36.78 | 25.20 | 20.12 |

| VaR95 | 34.43 | 56.97 | 36.78 | 25.73 | 22.31 | |

| CVaR95 | 52.91 | 65.05 | 42.14 | 32.62 | 30.73 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).