1. Introduction

Numerous studies have discussed a variety of issues related to estimates and certainty levels of information provided in geological reports while presenting classification systems developed by several renowned institutions. A comprehensive review of the current state of standards and codes for reporting mineral resources was presented by Slagmolen and Inneco [

1]. Their attention was concentrated on the two most important systems: UNFC [

2] and JORC/CRIRSCO [

3]. The UNFC, developed by the United Nations and supplemented by the United Nations Resource Management System (UNRMS), was developed to align the UNFC with the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). UNFC has been widely discussed in various national contexts [

4,

5,

6]. A European perspective on sustainable mineral resource management was provided by Christman [

7].

The Australasian Code for Reporting of Exploration Results, Mineral Resources, and Ore Reserves, developed by the Joint Ore Reserves Committee and thus commonly referred to as the JORC or the JORC Code, established a model that has been adopted by several other countries. This code was developed in response to a request from investors in mining companies looking for reliable information on mineral deposits underlying new listings or share offers launched by mining companies. Eventually, several other countries with their own, similar codes, decided to cooperate under the CRISRSCO umbrella. As this framework has gradually received recognition from capital markets and financial institutions, it has become the subject of numerous studies, which typically compare the JORC/CRIRSCO requirements to national standards [

8]. A separate category of research focuses on the Petroleum Resources Management System (PRMS) [

9], which covers hydrocarbons. These studies address issues such as classes of resources defined, factors to be considered, and the competence of professionals entitled to prepare valid reports. It is assumed that defining accuracy levels and specific parameters should remain in the purview of entitled experts.

The valuation of mineral assets has also been researched by scientists specializing in geology, mining, finance, and sustainability, with researchers in other disciplines also providing some valuable contributions, allowing for a better understanding of this complex area. Slagmolen and Inneco present several valuation codes [

1]. A more profound comparison was provided by Njowa et al. [

10]. Uberman analyzed valuation from the perspective of various financial and accounting systems [

11]. Various authors analyzed valuation methods, such as in [

12]. The authors of [

13,

14,

15] provided distinctive coverage of the application of real option models.

This present article addresses a substantial gap in the literature. When reviewing the papers presented above, the author failed to identify any work focusing on the specific problem of conjunction between the uncertainty levels considered in reporting mineral reserves and the ones required for a reliable evaluation of related risk in a valuation process. The work of Waquar Ali Asad and Dimitrakopolous, Azimi et al., Mudd et al., and Thompson and Barr [

16,

17,

18,

19] should be mentioned, as they are closely related to the subject. These studies mostly focus on metal ores and the issuing of cut-off grades, thus demonstrating the importance of this factor. However, none present the impact of error in estimating the metal content and recovery rates on the valuation of mineral assets.

The market value of mineral resources reflects the way they are used for product manufacturing and the resulting economic benefits. However, the total volume extracted is almost never sold. Moreover, in most cases, the mineral asset is not homogenous but composed of various grades or quality, which sometimes differ substantially in their respective application and value as raw materials. Mining enterprises carry out not only extraction but also conversion processes to obtain a marketable product. Numerous studies have analyzed, for example, gold mining companies as if they deliver pure gold to the market. This perspective is true but misleading, as virgin gold is not available, at least not in substantial volumes. What is actually mined is metal ore that is then converted into gold. Its content varies in a deposit and is identified with a range in concentration. For a valuator, it is essential to identify whether the confidence level reported refers to the ore volume, to the grade, or to the combination of both. Even more demanding cases include polymetallic ore or aggregates. In these cases, a valuator must analyze the combination of outputs, often with substantially different market values. In 2025, cobalt is priced double against nickel. Fortunately, these metals typically form alloys, so attaching the same error level to the content of both might be justified. However, in the case of marble, the share of blocks cannot be correlated with other grades.

UNFC defines an error in relation to volume, stating that one of the dimensions is a degree of confidence in the estimate of quantities of products from the project. If products are mentioned rather than the extraction stream, it must be interpreted as a combination of quantitative and quality factors. In the case of coal, for example, the product is a salable material after conversion losses. The problem arises from the definition of the product itself. UNFC stipulates that products of the project may be bought, sold, or used. The latter application creates an issue, as extracted material in its virgin form cannot be typically sold but is used as input for conversion processes.

In the case of JORC, quality issues appear in the initial stage. For mineral resources, it is required that the grade (or other relative quality factors), among other parameters, is known or estimated from specific geological knowledge, including sampling. It states that “

Where the Exploration Target statement includes information relating to ranges of tonnages and grades these must be represented as approximations. The explanatory text must include a description of the process used to determine the grade and tonnage ranges used to describe the Exploration Target.” Confidence categories of estimates include geological and grade continuity, and the consideration of the so-called modifying factors—"

considerations used to convert Mineral Resources to Ore Reserves. These include, but are not restricted to, mining, processing, metallurgical, (…) factors” [

3]. Therefore, reports complying with the JPRC requirements must include an estimation of error in establishing not only the volume of resources but also the quality parameters.

2. Materials and Methods

This study is based on several geological reports and mineral asset valuations. Both sources are restricted by confidentiality clauses. As a professional mineral asset valuator, the author drew on the valuations performed, which comprised both reports and related calculation models. In the case of geological reports, the situation was different, as they were prepared by professional geologists and disclosed to the author for the specific purpose of carrying out valuation procedures.

For the reasons indicated above, the data were changed to assure anonymity. However, they maintain their validity for the research presented. These altered data are provided in this article to allow others to replicate and build on the published results.

The primary method applied uses discounted cash flow (DCF) modeling with scenario analyses. This is a widely used and well-understood valuation technique offering substantial flexibility. For this analysis, three valuations of different mineral deposits were selected: coking coal, sand, and granite. All were in the development phase and varied substantially in key determinants of risk, such as the following:

Level of confidence provided in respective mineral resource reports;

Period to full depletion (mining project lifetime);

Use of the raw materials extracted.

For each of these deposits, a scenario-based valuation using the DCF technique was developed. These scenarios are denoted with “0” and were based on actual situations. Propositions were tested by applying alternate values of the selected parameters equal to the maximum errors assumed in geological reports to adversely impact the final value. Scenarios denoted with “1” are based on the minimum volume of the mineral reserves. Here, the lower bound of the confidence interval was applied so that if the error was assumed to be +/− 10%, the volume of reserves represents 90% of what was assumed in the base scenario. Qualitative scenarios need to be more sophisticated as they are necessary for recognizing losses but also reflect possible changes in the structure of the yield. Therefore, three different scenarios were constructed, although not all were applied to each deposit. Finally, the valuation results, reflected in the respective net present value (NPV), were compared for each scenario. The underlying assumption is that the risk exposure resulting from the reported error range can be measured according to relative changes in NPV.

3. Results

3.1. Impact of Estimation Error in Volume and Quality Parameters on Mineral Asset Value

It has been indicated that the confidence level of reserves disclosed in resource reports is commonly understood to refer to the volume. The quality parameters are also provided, as the error margin indicated typically relates to the confidence of laboratory tests rather than geological aspects. This fact would not substantially bias the valuation processes if the volume of the mineral reserves remains a dominant factor in the values disclosed in the resource report that established the mineral asset value, while errors in estimating other possible parameters would have a substantially lower impact.

Proposition 1. The volume of reserves in the mineral deposit under valuation is a dominant factor determining its value; thus, the error margin in a geological report should be interpreted as referring to this single parameter.

The validity of Proposition 1 was tested using the following procedure.

First, Scenario “0” valuation results for each of the three selected deposits were recalculated for a volume of reserves equal to the respective lower bounds of the confidentiality ranges. The Scenario “1” assumptions are presented below:

The coking coal deposit was an extension of an already exploited formation, which was easy to research, and an error was indicated at the 20% level. As the reserves, which were fully recoverable, were 11.2 M of Mg, the lowest possible volume would be 8.96 M of Mg. This would shorten the production period by 2 years, from 9 to 7.

The sand deposit had been identified in a pristine area with no local mining activity. The maximum error was estimated at 30%. As the fully recoverable reserves were 27 M of Mg, the lowest volume would be 18.9 M of Mg. This would shorten the production period by 15 years, from 45 to 30.

The granite deposit represented a specific case where two parts of what was geologically one deposit was documented in steps solely based on depth. The upper part had already been exploited for many years when the second, deeper part was documented and officially recognized. In this situation the confidence level can be high, and the maximum error was established at 10%. As the fully recoverable reserves were 22 M of Mg, the lowest volume would be 19.8 M of Mg. This would shorten the production period by 8 years, from 88 to 80.

The abovementioned error margins were determined by the authors of the geological reports. Production periods were established by determining the gradual increment to reach the maximum capacity; thus, a reduction in volume does not exactly match a decrease in a duration of production period. There are several technical differences in the determination of the impact of reserve adjustment in financial calculations, but they have no influence on the research results.

When analyzing the results, the case of the granite deposit stands out. If the real resources were equal to the lower bound, its value would decrease by only ca. 14%. This is due to both the relatively high confidence and the long production period. In contrast, sand and coking coal deposits suffer greater losses; in their case, the decline in the calculated NPV surpassed 40%. In the former case, the higher error margin compared to the latter is compensated for by the longer production phase.

Furthermore, several scenarios were constructed in relation to quality parameters. For coking coal, the most important variable is the yield of salable products. This may vary substantially not only between deposits but also internally. The base scenario assumes 92% yield, implying 8% losses. The first question refers to which parameter this error must be applied. In geological reports, no guidance is provided. Certainly, the negative impact on the valuation will be lower if the error is applied to losses. Consequently, two scenarios were constructed:

Scenario “2”, in which maximum error is applied to waste and the level was set at 9.6% (20% maximum error—with the upper bound carrying the most negative impact on valuation), thus providing a yield of 90.4%.

Scenario “3”, in which the error is applied to the yield—consequently set at 73.6% (20% maximum error—with the lower bound carrying the most negative impact on valuation).

For the sand deposit, quality must be interpreted in view of dispersion between fractions. The most valuable deposit is high-class glass sand followed by low-class glass sand, with the construction sand fraction representing little value (in numerous cases, part of this grade is dumped). Losses represent a minor problem, as technically they exist (3% level was assumed), but, in most cases, even the lowest quality stream can be melted, and the resulting mixture can be sold for non-demanding purposes. Thus, Scenario “2” was not constructed for this deposit. Therefore, quality-related scenarios were built for different interpretations regarding the impact of the maximum error:

Scenario “3” assumes that the error refers to the share of each grade and must be interpreted in a relative way. The greatest negative effect on valuation will occur if the shares of glass sands are reduced by 30% while the construction sand shares are increased by 30%. One can argue that technically the author should reduce the share of all three grades, balancing the total with increased losses, but such an option is rejected as artificial. In practice, deviations are noted mostly between salable fractions. Consequently, in this scenario, the yields (in rounded numbers) are as follows: high-class glass sand—22%; low-class glass sand—15%; and construction sand—57%.

Scenario “4” assumes that the error must be interpreted in absolute terms. If 30% of the reserves are missing at worst, this deviation may refer only to glass sands. Therefore, the yields will be 24%, 9%, and 63% (for high-class glass sand, low-class glass sand, and construction sand, respectively). This scenario also includes Scenario “1” as the total volume was also reduced. It is very unlikely that the reduced volume will concentrate only on the most valuable grade. In contrast, the assumption that it will proportionally affect all grades is very risky. Valuators need to identify the true worst-case scenario to evaluate risk.

A similar approach can be applied to the granite deposit. Again, the level of losses will not be considered as an important risk area. A valuator should give attention to the distribution of grades.

Scenario “3” for the granite deposit assumes that the error refers to the share of each grade and must be interpreted in a relative way. The greatest negative effect on valuation will occur if the share of blocks is reduced by 10% while the other shares are increased to compensate for it. Consequently, in this scenario, the yields in rounded numbers are as follows: blocks—27%; building stone—40%; and aggregates—32%.

Scenario “4” assumes that the error must be interpreted in absolute terms. If 10% of the reserves are missing, at worst, this deviation may only refer to blocks. Therefore, the yields in rounded numbers are as follows: blocks—22%; building stone—42%; and aggregates—33%. This scenario also includes Scenario “1” as the total volume was also reduced. Moreover, here, one must recognize a small likelihood of such a situation. Again, the reason for creating it is justified by a need to identify the truly worst-case scenario to evaluate risk.

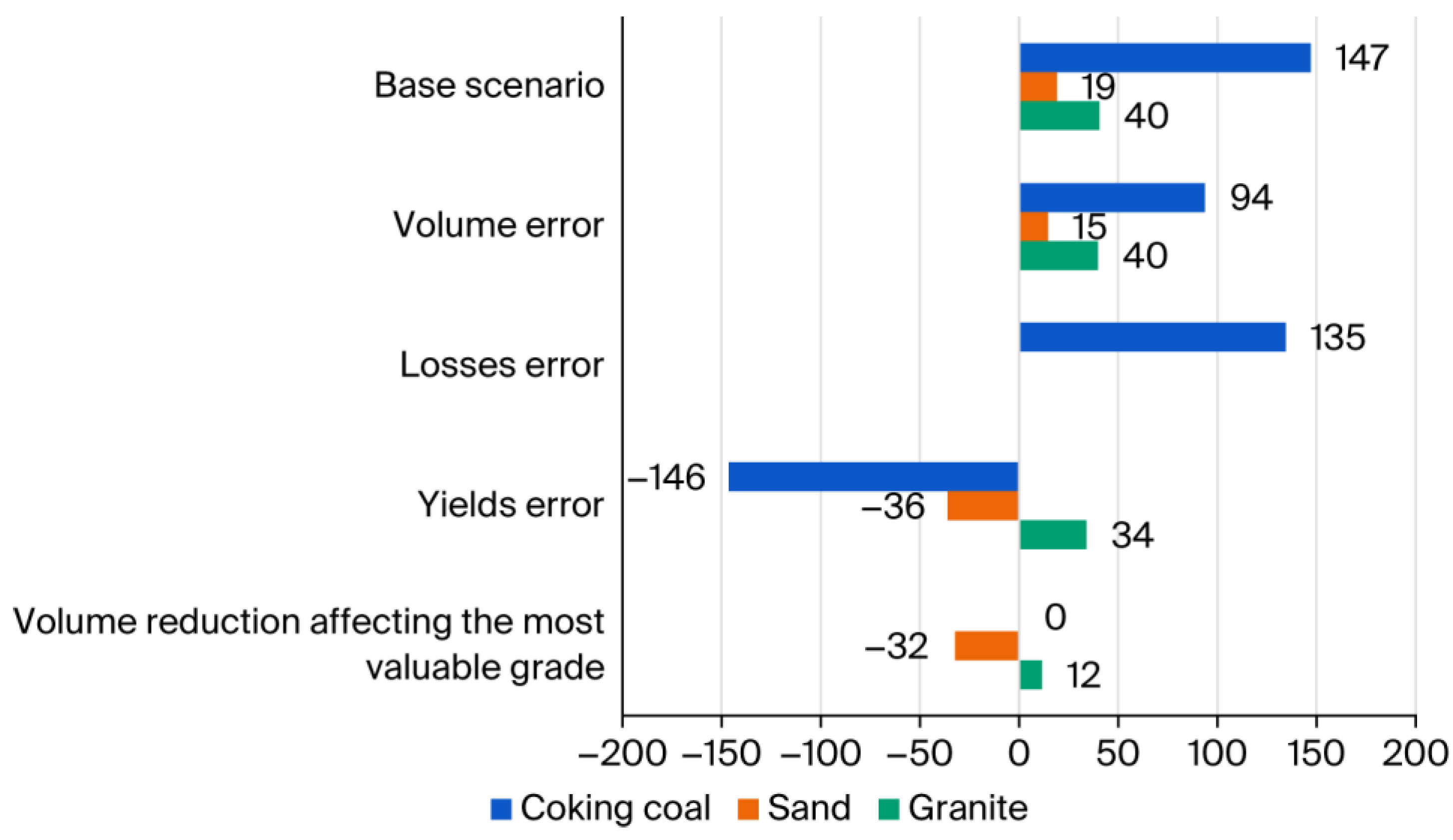

The summarized results of the NPV calculations for all three deposits and scenarios considered are provided below (

Figure 1). In all scenarios except “0”, discount rates were adjusted by eliminating the geological risk factor to reflect the consideration of the least favorable assumptions in this area.

In all three cases of mineral deposits, when the resource estimation error refers only to volume, the impact on valuation is limited. The case of coking coal is specific due to the relatively short project lifetime (9 years) and high investment outlays. In these circumstances, every year lost in the production phase has a substantial impact on the NPV. The granite deposit represents the opposite situation. With a project lifetime exceeding 80 years, the loss of benefits resulting from a very distant exploitation could not noticeably affect the NPV, especially as the confidentiality level in this case was high.

In general, uncertainty regarding quality factors has a much greater effect on the NPV. As for the coking coal deposit, linking the reported error with a specific parameter can change the valuation dramatically. When applied to losses, the effect is relatively small. When the yield of marketable coal changes, however, the NPV turns substantially negative. In view of these results, the weight of the valuators’ dilemma of determining which parameter an estimation error should be attached to becomes evident. A similar conclusion must be drawn from the analysis of the results obtained for the remaining two deposits. For the sand deposit, the key determinant of value is the yield of glass sands, especially high-class sand. In the case of the granite deposit, the determinant is the share of blocks. The remaining streams are economically auxiliary products. The overall volume plays a much smaller role. Therefore, a valuator needs to have a clear basis for estimating the risk resulting from a possible error in estimating the reserves of these key fractions.

The cases analyzed above are sufficiently representative to conclude that Proposition 1 is erroneous. Geological research should not only address quality issues but must also provide information about confidence levels regarding key quality parameters that are clearly separated from those referring to volume. The list of relevant variables should be defined in consideration of the assumed market application(s) of raw materials obtained in the processing phase.

3.2. Identification of Key Factors Determining Relative Importance of Estimation Errors

The analysis presented in

Section 3.1 allows for the identification of key variables to determine the importance of specific parameters for which reporting confidentiality levels is essential in performing a reliable valuation process.

Proposition 2. The relative value of various fractions yielded and the expected time to full depletion determine the impact of the estimation error regarding the mineral quality parameters.

The calculations presented above also allow for the identification of the factors that determine which parameters are pivotal for specific mineral deposits. First, the forecasted time to full depletion influences the importance of the reserve volume error. For deposits with a long time to full depletion, this error becomes negligible. The fundamental logic of the discounted cash flow method is such that the present value of distant flows draws near zero. Therefore, even if 30 years of production are missing but commence after 70 years from project development, they can be omitted for the purpose of valuation. Second, for deposits with substantial differences in prices between grades, errors in estimating quality parameters become a key issue. In most cases, extraction and, to some extent, processing costs are determined by input. Consequently, a lower-than-expected share of highly priced grades has a direct adverse impact not only on revenue but also on profit and net cash flow, beginning from the first year of the production phase. These findings cannot be regarded as conclusive since a limited sample is considered. However, the sample represents three deposits covering a wide span of possible circumstances affecting valuations. Therefore, Proposition 2 can be considered supported but requires further research.

4. Discussion

The valuation of mineral assets is one of the most challenging areas in finance. Its complexity, among other factors, is caused by the interaction between the natural properties of the minerals extracted and conversion processes. These properties cannot be known—they are always identified with a certain level of ambiguity. Valuators have various instruments to address this fact in the valuation process. Typically, they use proxies for each risk factor considered relevant to the final calculated value. Consequently, they need to establish a link to each specific parameter. If a selected proxy refers to more than one variable, a valuator must be convinced that such a set is homogenous. Whatever statistical measure is applied, such as confidence intervals and the resulting maximum deviation (which can be the doubled standard deviation), is much less important since there are tools allowing for the conversion of this information into an appropriate risk rate. What they cannot directly address is a situation in which a unified confidence interval applies to a co-heterogenous set of variables.

The quality factors of mineral deposits represent a complex challenge extending beyond geological issues. Final yields depend not only on the quality of the minerals (raw materials) but also on the conversion processes undertaken [

20,

21]. Many regulations require a geologist to consider the uncertainty of both volume and quality already in resource reports. The JORC Code admits that although it

is always necessary as part of the process of determining reasonable prospects for eventual economic extraction to consider potential metallurgical methods, the

assumptions regarding metallurgical treatment processes and parameters made when reporting Mineral Resources may not always be rigorous. The Code recommends but does not require that

the existence of any bulk sample or pilot scale test work and the degree to which such samples are considered representative of the orebody as a whole is reported. Moreover, it allows for a choice between so-called global (related to the whole deposit) and local (related to a specific part) approaches to estimate accuracy (JORC).

In the case of a few specific sectors, such as hydrocarbons, advanced models have been developed that allow for statistical analyses of key quality parameters and thus estimating individual errors. However, geologists are often unable to rely on such sophisticated tools. They need expertise from industries identified as possible users of the minerals researched. A very good example of an individualized approach to uncertainties is presented by Jiang and Dmitrakopolous [

21], who distinguished supply and equipment uncertainties. For the former, they analyzed the volume of ore and, for the latter, they focused on copper, addressing both key factors. Their study refers to operational issues rather than directly to the valuation process but, if this very mine was under valuation, the information provided would be sufficient. Azimi et al. [

16] performed similar research for a gold mine. Their objective was to develop a model to establish the optimal cut-off grade, selecting the real-option value as the financial measure and performing Monte Carlo simulations to generate scenarios. As gold content was one of the input parameters, the model must enable valuators to calculate its dispersion and confidence interval. Real-option pricing was also applied by Thomson and Barr [

18], who discussed the influence of market-price uncertainty on the cut-off grade. They examined the opposite question to the one addressed in this study. Their study assumed the metal content was set with certainty and analyzed how uncertainty regarding future gold prices affects the minimum required for the economically feasible extraction of gold. These abovementioned articles indicate the fundamental challenge in establishing confidence intervals for quality factors. All of them consider mineral deposits in the production phase, when in a natural way, data from processing activities become easily available. In addition, various laboratory tests (including sampling) were carried out to meet the customers’ requirements. Consequently, data availability and testing costs cease to represent major obstacles.

Further research should follow two directions:

Modeling interrelations between mineral quality parameters and the market value of raw materials to be sold.

Linking testing requirements for the physical and chemical parameters of minerals during geological surveying with the requirements of targeted industries.

5. Conclusions

This article focuses on the interpretation of the confidence of values disclosed in geological reports. As it is was established that current methods, however advanced, are not capable of providing certain information, users of such reports need clear guidelines regarding not only the magnitude of possible deviations but also whether they apply only to the volume of minerals or include key quality parameters sufficient for mineral asset valuation. The cases presented emphasize that deviations regarding the volume of reserves in the mineral deposit under valuation do not need to be a dominant factor affecting the value. In all of the scenarios, uncertainty regarding at least one quality factor impacted valuation results in a much stronger manner. Measuring possible errors in the physical and chemical parameters of minerals represents an extreme challenge for geologists for the following two reasons: Firstly, it depends on other disciplines, such as mining, metallurgy, or chemical processes. Secondly, running a testing program covering important parameters for all targeted industries is, in most cases, much more expensive than simply conducting one required for volume. These barriers should not be neglected, but the need to provide reliable valuations to capital providers must also be recognized. In all resource reports, a clear link needs to be established between testing the physical and chemical parameters of minerals during geological surveying and the requirements of targeted industries. In parallel, there is a demand for modeling interrelations between the physical and chemical parameters of minerals during geological surveying and their market value.

Funding

Research partly supported by the program “Excellence Initiative—Research University” from the AGH University of Krakow.

Data Availability Statement

The original datasets used in the calculations are not publicly available due to confidentiality clauses. The modified data sufficient to verify their consistency are included in the Appendixes.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the author used valuable input from P. Saługa, PhD, for the purposes of presenting the hard coal case. He also benefited from discussions with several mineral asset valuators. The author reviewed and edited the output and takes full responsibility for the content of this publication. The research project was supported/partly supported by the program “Excellence Initiative—Research University” from the AGH University of Krakow.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of the data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| OPEX |

Operating Costs Excluding DDA |

| DDA |

Depreciation, Depletion, and

Amortization |

| NWC |

Net Working Capital |

| CAPEX |

Capital Expenditures Assumed Equal to

Initial Investment |

| ARCP |

Account Receivables Collection Period |

| SCP |

Stock Conversion Period |

| APSP |

Account Payables Settlement Period |

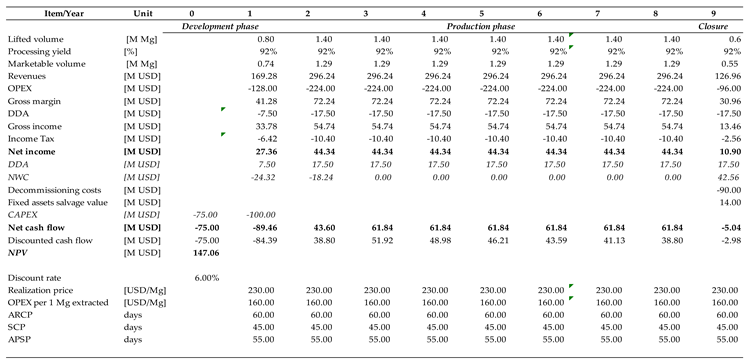

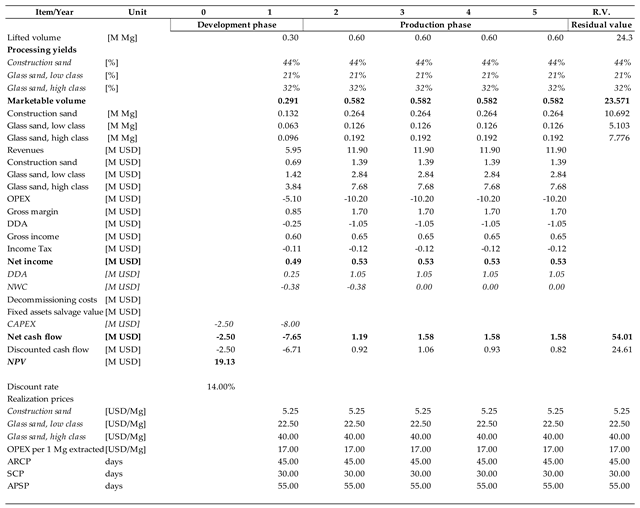

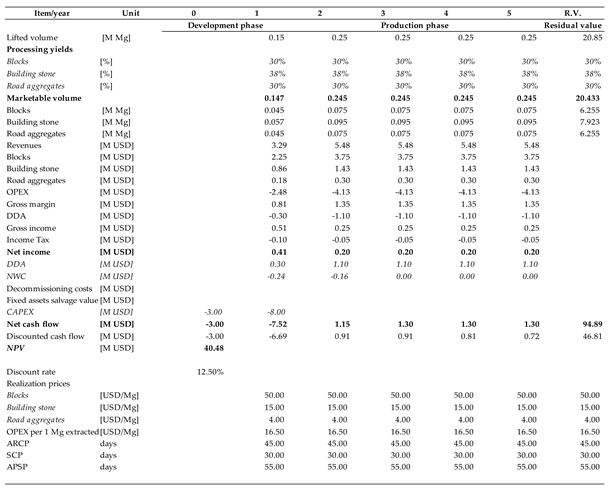

Appendix A. Coking Coal Deposit Calculations

The tables below present NPV calculations for the coking coal deposit.

Table A1.

Coking coal—Scenario 0.

Table A1.

Coking coal—Scenario 0.

Table A2.

Coking coal—Scenario 1: Reserves volume reduced by maximum error—20%.

Table A2.

Coking coal—Scenario 1: Reserves volume reduced by maximum error—20%.

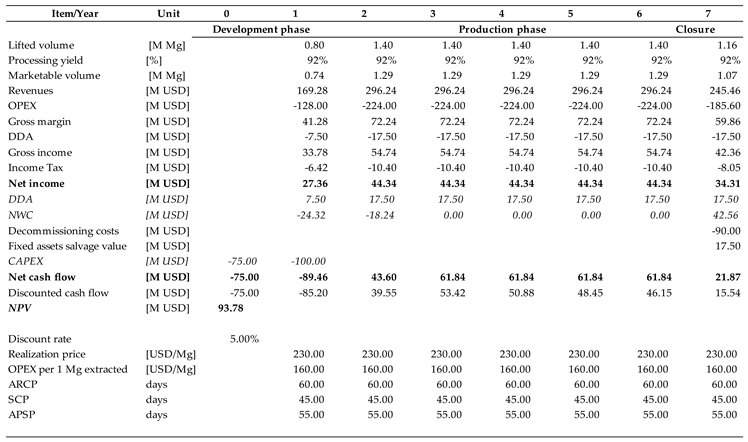

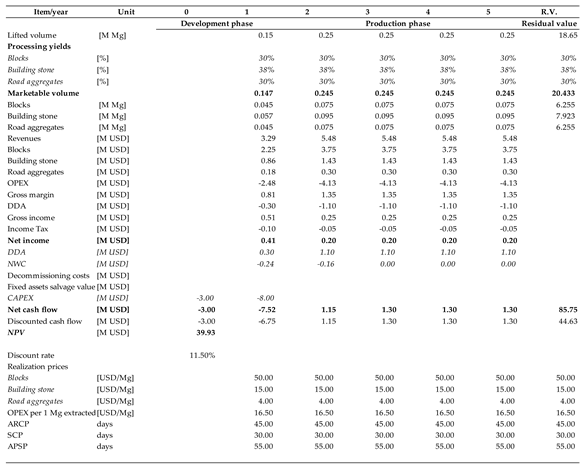

Table A3.

Coking coal—Scenario 2: Waste ratio increased by maximum error—20%.

Table A3.

Coking coal—Scenario 2: Waste ratio increased by maximum error—20%.

Table A4.

Coking coal—Scenario 3: Yield of salable product reduced by maximum error—20%.

Table A4.

Coking coal—Scenario 3: Yield of salable product reduced by maximum error—20%.

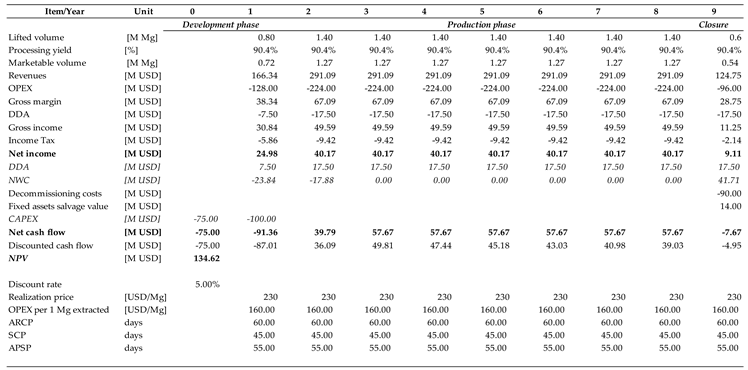

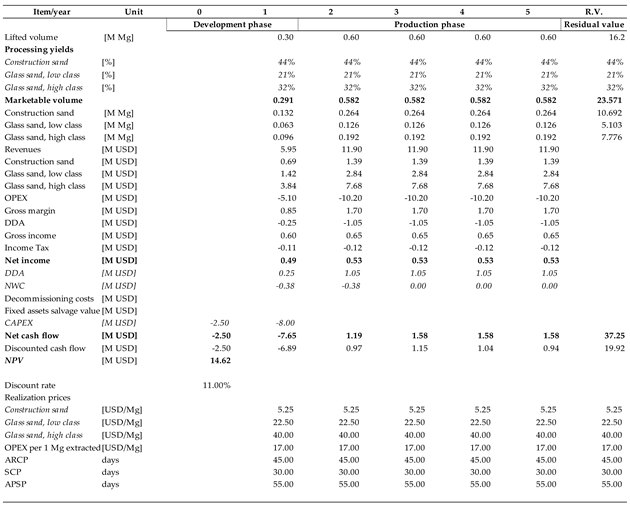

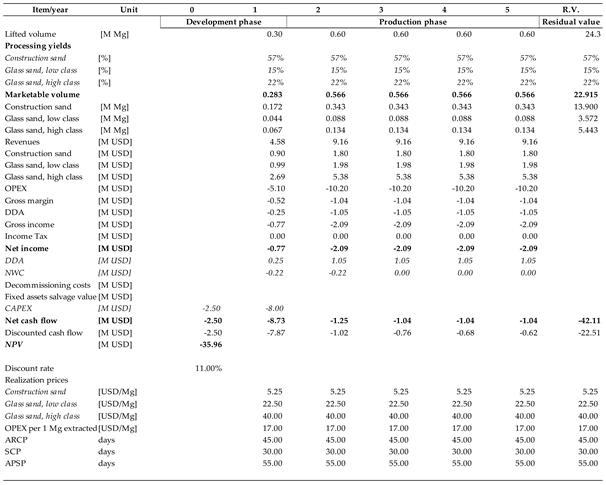

Appendix B. Sand Deposit Calculations

The tables below present NPV calculations for the sand deposit.

Table A5.

Sand deposit—Scenario 0.

Table A5.

Sand deposit—Scenario 0.

Table A6.

Sand deposit—Scenario 1. Reserves volume reduced by maximum error—30%.

Table A6.

Sand deposit—Scenario 1. Reserves volume reduced by maximum error—30%.

Table A7.

Sand deposit—Scenario 1. Share of glass sands in reserves reduced by maximum error—30%.

Table A7.

Sand deposit—Scenario 1. Share of glass sands in reserves reduced by maximum error—30%.

Table A8.

Sand deposit—Scenario 3. Reduction in reserves volume affects only glass sands.

Table A8.

Sand deposit—Scenario 3. Reduction in reserves volume affects only glass sands.

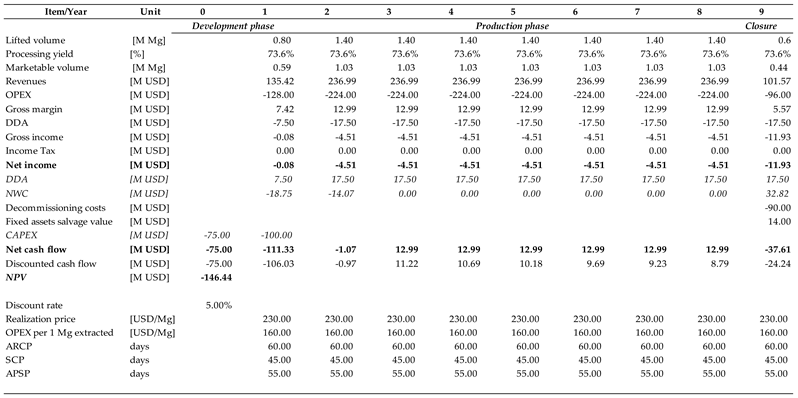

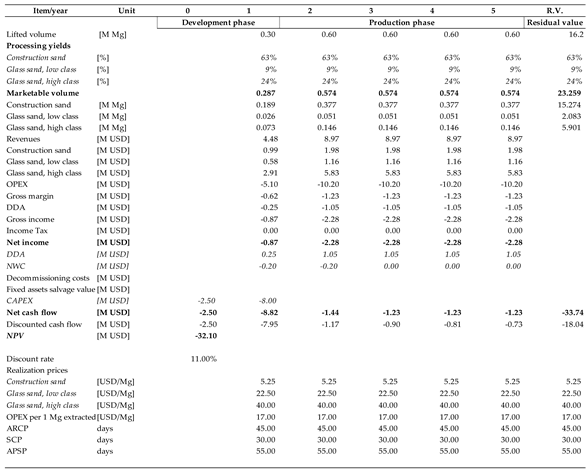

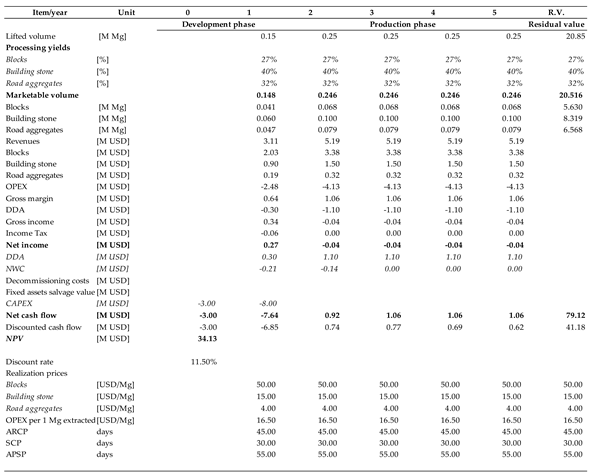

Appendix C. Granite Deposit Calculations

Table A9.

Granite deposit—Scenario 0.

Table A9.

Granite deposit—Scenario 0.

Table A10.

Granite deposit—Scenario 1. Reserves volume reduced by maximum error—10%.

Table A10.

Granite deposit—Scenario 1. Reserves volume reduced by maximum error—10%.

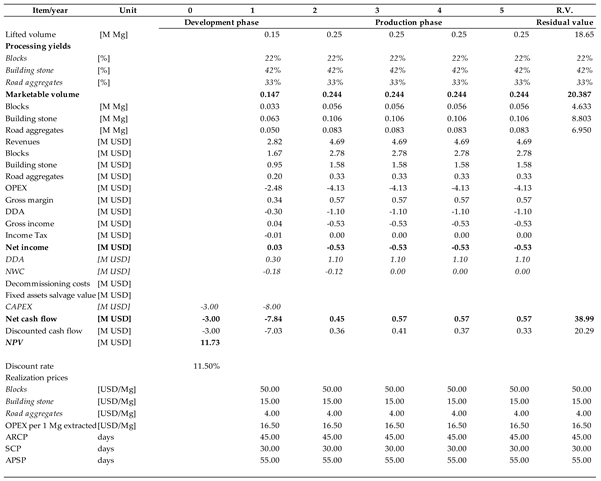

Table A11.

Granite deposit—Scenario 2. Share of blocks in reserves reduced by maximum error—10%.

Table A11.

Granite deposit—Scenario 2. Share of blocks in reserves reduced by maximum error—10%.

Table A12.

Granite deposit—Scenario 3. Reduction in reserves volume affects only blocks.

Table A12.

Granite deposit—Scenario 3. Reduction in reserves volume affects only blocks.

References

- Slagmolen, S.; Inneco, P. State of codes and standards for the reporting of mineral resources and reserves. Min. Eng. 2024, 10, 22–28. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. United Nations Framework Classification for Resources: Update 2019; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- JORC Code: Australasian Code for Reporting of Minera Resources and OreReserves. Joint Ore Reserves. Committee of The Australasian 1MM, Australian Inst. of Geoscientists and Minerals Counci of Australia, 2012. https://www.jorc.org/docs/JORC_code_2012.pdf.

- Buchanan, D.L. Equity fund raising and the role of share performance metrics in the valuation of mineral projects. Min. Econ. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simić, V.; Životić, D.; Miladinović, Z. Towards better valorisation of industrial minerals and rocks in Serbia—Case study of industrial clays. Resources 2021, 10, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieć, M.; Piwocki, M.; Przeniosło, S. International classification of resources/reserves and its relation to deposit feasibility. GSM–Min. Res. Mngt 2002, 18, 19–28. [Google Scholar]

- Christman, P. Mineral Resource Governance in the 21st Century and a sustainable European Union. Min. Econ. 2021, 34/2, 178–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saługa, P.W.; Sobczyk, E.J.; Kicki, J. Reporting of hard coal reserves and resources in Poland on the basis of the JORC code. GSM/Min. Res. Mngt. 2015, 31, 5–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PRMS. The Petroleum Resources Management System. SPE Oil and Gas Reserves Committee. 2018.

- Njowa, G.; Clay, A.N.; Musingwini, C. A perspective on global harmonisation of major national mineral asset valuation codes. Res. Pol. 2014, 39, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uberman, R. Valuation of Mineral Resources in Selected Financial and Accounting Systems. Nat. Res. 2014, 5/9, 496–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lilford, E.V.; Minnitt, R.C.A. A comparative study of valuation methodologies for mineral developments. J. S. Afr. Inst. Min. Metall. 2005, 105, 29–42. [Google Scholar]

- Slade, M.E. Valuing Managerial Flexibility: An Application of Real-Option Theory to Mining Investments. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2001, 41, 193–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Zhu, L. A real options based model and its application to China’s overseas oil investment decisions. Energy Econ. 2010, 32, 627–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saługa, P.W.; Zamasz, K.; Kamiński, J. Valuation of mineral project with flexibility ‘mad’ approach vs. Consecutive stochastic tree. GSM/Min. Res. Mngt. 2015, 31, 31–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asad, M.W.; Dimitrakopoulos, R. Optimal production scale of open pit mining operations with uncertain metal supply and long-term stockpiles. Res. Pol. 2012, 37, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azimi, Y.; Osanloo, M.; Esfahanipour, A. An uncertainty based multi-criteria ranking system for open pit mining cut-off grade strategy selection. Res. Pol. 2013, 38, 212–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudd, G.M.; Weng, Z.; Jowitt, S.M.; Turnbull, I.D.; Graedel, T.E. Quantifying the recoverable resources of by-product metals: The case of cobalt. Ore Geol. Rev. 2013, 55, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, M.; Barr, D. Cut-off grade: A real options analysis. Resour. Policy 2014, 42, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čablík, V.; Kolomaznik, I.; Tora, B.; Fečko, P. Classical and column flotation of black coal samples. Inżynieria Miner. 2009, 23, 37–48. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/289792050 (accessed on 25.05.2025).

- Jiang, Y.; Dimitrakopoulos, R. Simultaneous stochastic optimisation of mining complexes with equipment uncertainty: Application at an open-pit copper mining complex. Min. Technol. Trans. Inst. Min. Metall. 2024, 133, 241–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).